Abstract

Background and Objectives:

Large-scale prospective case series of tapentadol abuse or dependence in India is not available. Hence, we aimed to study the prevalence and profile of tapentadol users in a treatment-seeking population.

Materials and Methods:

The study had prospective and retrospective arms. We collected 8-month prospective data by face-to-face interviews (n = 70) and 8-year retrospective data from case notes (n = 26) with either tapentadol misuse/abuse or dependence in patients attending a de-addiction center.

Results:

The prevalence of tapentadol abuse or dependence was 25% among the pharmaceutical opioid users. Concurrent use of other opioids was seen in >80% of participants of both the arms. Major sources of tapentadol were chemists (without a prescription) (53%) and doctors (prescriptions) (40%). Patients in the tapentadol dependence group had a significantly higher dose, duration, and pharmaceutical opioid use.

Conclusion:

India needs awareness promotion, training, availability restriction, and provision of treatment for tapentadol abuse or dependence.

Keywords: Abuse, dependence, misuse, pharmaceutical opioid, prevalence, tapentadol

INTRODUCTION

The 2019 Magnitude of Substance Use in India survey showed pharmaceutical opioids to be the second most commonly abused opioids (0.96%), after heroin (1.14%).[1] After scheduling of codeine, dextropropoxyphene, and tramadol due to their abuse potential in 2011, 2017, and 2018, respectively, there is a chance of emergence of abuse of another new pharmaceutical opioid.

Tapentadol is a synthetic opioid with both μ-opioid receptor agonist and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor actions. The μ-receptor agonism of tapentadol lies in between that of morphine and tramadol.[2] Although tapentadol has not yet been scheduled under the Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act, there is emerging clinical experience and initial evidence showing its abuse liability in India. Basu et al. reported two patients who substituted dextropropoxyphene and buprenorphine with tapentadol.[3] A recent retrospective study published from southern India described the sociodemographic and clinical profile for patients seeking treatment for tapentadol dependence. This study also used Google search Trend as a proxy marker for interest in tapentadol, which showed that the union territory of Chandigarh (CG) was in the forefront regarding the online interest of tapentadol.[4] However, the retrospective study design has flaws such as recall bias and reduced availability of information. Moreover, substance use patterns in India differ across regions.[1] Addressing these limitations and tapping the regional difference required another study. We aimed to study the prevalence and profile of tapentadol users in a treatment-seeking population in North India using a mixed design.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We aimed to examine the prevalence and sociodemographic as well as the clinical profile of tapentadol users attending an addiction treatment facility of a tertiary-care teaching general hospital's psychiatric unit in CG. We used a uniform semi-structured evaluation format to assess patients. An in-house laboratory provided urine drug screening. Ethical clearance was obtained from the institute's ethics committee for this study.

This study had a prospective arm (PA; May to December 2019) and another retrospective arm (RA; July 2011 to April 2019). We included all the patients with reported or recorded history of tapentadol use.

Operational definitions

Dependence was diagnosed as per the International Classification of Diseases-10 (ICD-10) criteria.[5]

Misuse was defined as any use outside of prescription parameters, including misunderstanding of instructions; self-medication of sleep, mood, or anxiety symptoms; and compulsive use driven by an opioid use disorder.[6]

Abuse was defined as use without a prescription, in a way other than prescribed, or for the experience or feelings elicited.[6]

Procedure

For the RA (July 2011–April 2019), we extracted the case records with the ICD-10 diagnosis of opioid dependence, and after a manual check of the case notes, we recorded the specified sociodemographic and clinical parameters of those with tapentadol use/dependence. For the PA (May 2019–December 2019), we recruited all first-visit patients from the walk-in clinic who acknowledged tapentadol use after obtaining informed consent. The dose, duration of consumption, route, brand, and formulation of tapentadol used were recorded in both the arms. We recorded further details such as the reason of use, psychoactive effect, and source of the substance while directly interviewing the patients in the PA.

Statistical analysis

We applied descriptive statistics (mean with standard deviation wherever applicable) for both the arms. Subsequently, we compared the means of sociodemographic, clinical, and tapentadol-related variables between the two subgroups of the PA (misuse–abuse [MA group] and dependent group) to determine if there were significant intergroup differences.

RESULTS

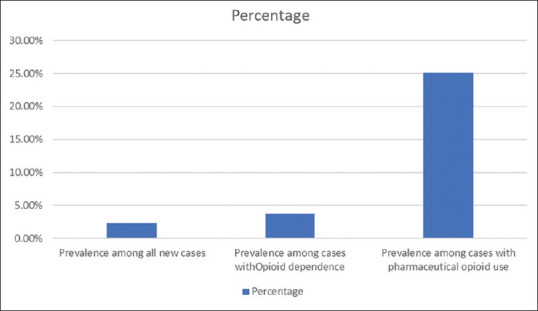

From May to December 2019, there were a total of 3084 new cases, including 1860 cases with opioid dependence. There were 279 cases with pharmaceutical and/or mixed opioid use and 70 cases of tapentadol use. The prevalence of tapentadol use was 2.3% among all new cases, 3.8% among opioid users, and 25.1% among pharmaceutical/mixed opioid users [Figure 1]. We could identify only 26 cases of tapentadol use in the RA. The first case was recorded in November 2014. We could find two cases each from the years 2015 to 2017, 14 cases in 2018, and 5 cases from January to April 2019.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of tapentadol use among the patient population

Sociodemographic and clinical variables of patients

Both the arms predominantly consisted of young, unmarried, unemployed males, who were educated up to intermediate and were hailing from nuclear families, urban background, and adjacent areas [Table S1]. On an average, patients started using opioids in their early twenties and were using the same for around 6 years. Tapentadol use started in their mid-twenties and continued for around 1–2 years with a daily average dose of around 550 mg. Nearly half of the PA patients used heroin (around one-fourth had morphine-positive urine) and around one-third of the RA patients used tramadol (around one-fourth had tramadol-positive urine) concurrently. Although most of them had a history of intravenous opioid use, only four patients in PA arm used intravenous tapentadol. “Tapal” was the most familiar brand, and “immediate release” was the most common preparation used by our patients. Around half of the patients were nicotine dependent. Around one-third of the patients had no prior treatment history. Five patients were hepatitis C positive; 11 had a psychiatric illness (most commonly mood disorder) and 21 patients had medical comorbidities [Table 1].

Table S1.

Sociodemographic data of patients in prospective and retrospective arms

| Variables | PA (n=70), n (%)/mean (SD) | RA (n=26), n (%)/mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Mean age (years) | 27.36 (6.44) | 29.46 (6.75) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 69 (98.6) | 25 (96.1) |

| Female | 1 (1.4) | 1 (3.9) |

| Marital status | ||

| Never married | 41 (58.6) | 15 (57.7) |

| Married | 26 (37.1) | 10 (38.5) |

| Separated and divorced | 3 (4.3) | 1 (3.8) |

| Education | ||

| Illiterate | 1 (1.4) | 2 (7.6) |

| Up to matriculation | 18 (25.7) | 9 (34.6) |

| 10, +2/diploma | 34 (48.6) | 8 (30.8) |

| Graduate and above | 17 (24.3) | 7 (27.0) |

| Occupation | ||

| Professional and semi-professional | 8 (11.4) | 1 (3.8) |

| Clerical/shop owner/farmer | 12 (17.1) | 5 (19.2) |

| Skilled worker | 11 (15.7) | 4 (15.4) |

| Semi-skilled worker | 10 (14.3) | 3 (11.5) |

| Unskilled | 2 (2.8) | 1 (3.8) |

| Unemployed | 27 (38.6) | 12 (46.2) |

| Family type | ||

| Nuclear | 40 (57.1) | 19 (73.1) |

| Joint/extended | 30 (42.9) | 7 (26.9) |

| Locality | ||

| Urban | 52 (74.3) | 16 (61.5) |

| Rural | 18 (25.7) | 10 (38.5) |

| Distance | ||

| Local | 29 (41.4) | 11 (42.3) |

| Up to 40 km | 21 (30.0) | 8 (30.8) |

| 40-80 km | 7 (10.0) | 3 (11.5) |

| >80 km | 13 (18.5) | 4 (15.4) |

PA – Prospective arm; RA – Retrospective arm

Table 1.

Clinical data of patients in the prospective and retrospective arms

| Variables | PA (n=70), n (%)/mean (SD) | RA (n=26), n (%)/mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Age of first use of opioids (years) | 22.7 (5.03) | 23.77 (5.01) |

| Duration of dependence (months) | 52.81 (52.73) | 59.54 (62.14) |

| Age at first use of tapentadol (years) | 26.41 (6.63) | 24.42 (5.61) |

| Duration of use (months) | 10.33 (9.61) | 20.58 (16.25) |

| Average daily dose (mg) | 526.29 (475.77) | 565.22 (462.80) |

| Concurrent opioid use | ||

| None | 11 (15.7) | 5 (19.2) |

| Natural | 7 (10.0) | 2 (7.7) |

| Heroin | 32 (45.8) | 4 (15.4) |

| Tramadol | 16 (22.9) | 10 (38.5) |

| Others | 4 (5.6) | 5 (19.2) |

| Urine testing | ||

| Not available | 0 (0) | 11 (42.3) |

| Opioid negative | 15 (21.4) | 2 (7.7) |

| Tramadol positive | 12 (17.1) | 6 (23.1) |

| Morphine positive | 17 (24.3) | 6 (23.1) |

| BPN positive | 3 (4.3) | 1 (3.8) |

| Intravenous opioid use | ||

| No | 39 (55.7) | 22 (84.6) |

| Yes | 31 (44.3) | 4 (15.4) |

| Route of tapentadol use | ||

| Oral | 67 (95.7) | 26 (100) |

| Parenteral | 3 (4.3) | 0 (0) |

| Formulation | ||

| Unknown | 7 (10.0) | 12 (46.2) |

| Instant release | 61 (87.1) | 9 (34.6) |

| Sustained release | 1 (1.4) | 3 (11.5) |

| Both | 1 (1.4) | 2 (7.7) |

| Brand name | ||

| Unknown | 15 (21.4) | 18 (69.2) |

| Tapal | 37 (52.9) | 6 (23.1) |

| Others | 18 (25.7) | 2 (7.7) |

| Past opioid use | ||

| None | 8 (11.4) | 4 (15.4) |

| Natural | 19 (27.1) | 2 (7.7) |

| Heroin | 22 (31.4) | 5 (19.2) |

| Tramadol | 10 (14.3) | 5 (19.2) |

| Others | 13 (18.6) | 10 (38.4) |

| History of other drug dependence | ||

| None | 14 (20.0) | 4 (15.4) |

| Alcohol | 4 (5.7) | 2 (7.7) |

| Cannabis | 18 (25.7) | 2 (7.7) |

| Benzodiazepine | 5 (7.1) | 3 (11.5) |

| Nicotine | 29 (41.4) | 15 (57.7) |

| Past history of treatment seeking | ||

| Nil | 24 (34.3) | 12 (46.2) |

| Government centers | 12 (17.2) | 3 (11.5) |

| Private centers | 34 (48.5) | 11 (42.3) |

| HCV status | ||

| No | 66 (94.3) | 25 (96.1) |

| Yes | 4 (5.7) | 1 (3.9) |

| Psychiatric illness | ||

| None | 63 (90) | 21 (84.6) |

| Present | 7 (10) | 4 (15.4) |

| Medical comorbidity | ||

| No | 58 (82.9) | 17 (65.4) |

| Yes | 12 (17.1) | 9 (34.6) |

SD – Standard deviation; BPN – Buprenorphine; PA – Prospective arm; RA – Retrospective arm; HCV – Hepatitis C virus

Characteristics and pattern of tapentadol use in prospective arm

Most of the PA patients started tapentadol to substitute their usual opioid (71.4%), whereas nearly half of them (48.6%) were substituting heroin with tapentadol. Most (72.9%) of them considered the psychoactive effect of tapentadol to be inferior to their usual opioid. While 27 (38.6%) patients were prescribed tapentadol by a doctor at some point in time, 37 (52.9%) patients were buying tapentadol from a chemist without prescription. Half (51.4%) of the patients met the definition of MA group, and the rest met the criteria for dependence (D group) [Table 2].

Table 2.

Characteristics and pattern of use of tapentadol among patients in the prospective arm

| Variables | PA (n=70), n (%) |

|---|---|

| Probable reason for initiation of tapentadol | |

| Substitute for the usual opioid | 50 (71.4) |

| Pain management | 2 (2.9) |

| Augmenting the psychoactive effect of the usual opioid | 5 (7.1) |

| Started with tapentadol itself | 6 (8.6) |

| Prescribed/took for withdrawal management | 7 (10.0) |

| Substitution for opioid | |

| None | 8 (11.4) |

| Natural | 8 (11.4) |

| Heroin (chasing and intravenous) | 34 (48.6) |

| Tramadol | 13 (18.6) |

| Others | 7 (10) |

| Psychoactive effect of tapentadol | |

| Better than usual opioid | 4 (5.7) |

| Same to the usual opioid | 6 (8.6) |

| Inferior to the usual opioid | 51 (72.9) |

| Started with tapentadol only | 8 (11.4) |

| Different | 1 (1.4) |

| Was tapentadol prescribed by physician? | |

| No | 43 (61.4) |

| Yes | 27 (38.6) |

| Possible current source of tapentadol | |

| Friend | 20 (28.6) |

| Chemist | 37 (52.9) |

| Peddler | 11 (15.7) |

| Other | 2 (2.9) |

| Pattern of tapentadol use | |

| Misuse/abuse | 36 (51.4) |

| Dependence | 34 (48.6) |

PA – Prospective arm

Sociodemographic, clinical, and tapentadol-related variables in the subgroups of prospective arm

The MA and D groups were similar in their sociodemographic and clinical profile [Table S2]. Although both the groups had initiated tapentadol use at a similar age, the D group had significantly higher mean duration (13.7 ± 10.1 months) and daily dose (mean 820.3 ± 531.0 mg) of tapentadol. A significantly higher number of patients in the MA group were using heroin concurrently (69.4%), were using tapentadol to substitute heroin (63.9%), were prescribed tapentadol by a physician at some point of time (55.6%), and were buying it from a pharmacy (66.7%). A significantly higher number of patients in the D group considered the psychoactive effect of tapentadol to be noninferior (29.4%) than their usual opioid and had a comorbid psychiatric illness [Table 3].

Table S2.

Comparison between sociodemographic and clinical variables between patients with misuse/abuse and those with dependence to tapentadol

| Variable | Misuse/abuse (n=36), n (%)/mean (SD)/rank | Dependence (n=34), n (%)/mean (SD)/rank | Chi-square/Fisher’s exact/t/Mann-Whitney U-value | df | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (in years) | 27.1 (6.5) | 27.6 (6.5) | −0.327 | 68 | 0.75 |

| Marital status | |||||

| Married | 12 (33.33) | 14 (41.18) | 0.461 | 1 | 0.48 |

| Not married | 24 (66.67) | 20 (58.82) | |||

| Education | |||||

| Up to matric | 8 (22.22) | 11 (32.35) | 1.064 | 2 | 0.59 |

| 10, +2/diploma | 18 (50) | 16 (47.06) | |||

| Higher | 10 (27.78) | 7 (20.59) | |||

| Occupation | |||||

| Unemployed | 16 (44.44) | 11 (32.35) | 2.236 | 2 | 0.33 |

| Unskilled and semi-skilled | 4 (11.11) | 8 (23.53) | |||

| Skilled | 16 (44.44) | 15 (44.12) | |||

| Family type | |||||

| Nuclear | 21 (58.33) | 19 (55.88) | 0.043 | 1 | 0.84 |

| Extended | 15 (41.67) | 15 (44.12) | |||

| Locality | |||||

| Urban | 29 (80.56) | 23 (67.65) | 1.525 | 1 | 0.22 |

| Rural | 7 (19.44) | 11 (32.35) | |||

| Distance | |||||

| Within CG UT | 13 (36.11) | 16 (47.06) | 0.864 | 1 | 0.49 |

| Outside CG UT | 23 (63.89) | 18 (52.94) | |||

| Age of first use of any opioids | 23.5 (5.2) | 21.9 (4.8) | 1.353 | 68 | 0.18 |

| Duration of dependence | 48.9 (51.8) | 57.0 (54.2) | 657.0 | 0.60 | |

| Types of past opioid use | |||||

| Natural | 8 (22.22) | 11 (32.35) | 0.62 | 4 | 0.57 |

| Heroine | 17 (47.22) | 5 (14.71) | |||

| Others (pharmaceuticals) | 8 (22.22) | 13 (38.24) | |||

| Intravenous opioid use | |||||

| No | 18 (50) | 21 (61.76) | 0.981 | 1 | 0.32 |

| Yes | 18 (50) | 13 (38.24) | |||

| Past history of treatment seeking | |||||

| Yes | 23 (63.89) | 23 (67.65) | 0.741 | 1 | 0.80 |

| No | 13 (36.11) | 11 (32.35) | |||

| History of other drug dependence | |||||

| None | 9 (25) | 5 (14.71) | 2.620 | 3 | 0.454 |

| Nicotine | 16 (44.44) | 13 (38.24) | |||

| Cannabis | 8 (22.22) | 10 (29.41) | |||

| lcohol/BZD | 3 (8.33) | 6 (17.65) | |||

| Medical comorbidity | |||||

| No | 30 (83.33) | 28 (82.35) | 0.012 | 1 | 0.913 |

| Yes | 6 (16.67) | 6 (17.65) |

CG – Chandigarh; UT – Union territory; BZD – Benzodiazepine

Table 3.

Comparison between patients with misuse/abuse and those with dependence to tapentadol with regard to characteristics and patterns of use of tapentadol

| Variable | Misuse/abuse (n=36), n (%)/mean (SD)/rank | Dependence (n=34), n (%)/mean (SD)/rank | Chi-square/Fisher’s exact/t/Mann-Whitney U value | df | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age of onset of tapentadol (years) | 26.5 (6.4) | 26.4 (6.9) | 0.075 | 68 | 0.941 |

| Duration of use (months) | 7.2 (8.1) | 13.7 (10.1) | 877 | 0.002 | |

| Daily dose (mg) | 248.6 (130.8) | 820.3 (531.0) | −6.264 | 68 | <0.001 |

| Route of use | |||||

| Oral | 36 (100) | 31 (91.18) | 3.319 | 1 | 0.109 |

| Intravenous | 0 | 3 (8.82) | |||

| Brand | |||||

| Tapal | 18 (50) | 19 (55.88) | 0.24 | 1 | 0.62 |

| Others | 18 (50) | 15 (44.12) | |||

| Reason | |||||

| Substitution | 27 (75) | 23 (67.65) | 0.463 | 1 | 0.50 |

| Other | 9 (25) | 11 (32.35) | |||

| Concurrent opioid use | |||||

| Natural | 4 (11.11) | 3 (8.82) | 10.828 | 2 | 0.004 |

| Heroin | 25 (69.44) | 7 (20.59) | |||

| Others | 6 (16.67) | 13 (38.24) | |||

| Substitution of opioids | |||||

| None | 3 (8.11) | 5 (14.71) | 8.364 | 2 | 0.015 |

| Heroin | 23 (63.89) | 10 (29.41) | |||

| Pharmaceutical and natural | 10 (27.78) | 19 (55.88) | |||

| Prescribed by physician | |||||

| No | 16 (44.44) | 27 (79.41) | 9.023 | 1 | 0.003 |

| Yes | 20 (55.56) | 7 (20.59) | |||

| Source | |||||

| Chemists | 24 (66.67) | 13 (38.24) | 5.67 | 1 | 0.017 |

| Friends and peddlers | 12 (33.33) | 21 (61.76) | |||

| Psychoactive effect of tapentadol | |||||

| Inferior | 35 (97.22) | 24 (70.59) | 9.365 | 1 | 0.002 |

| Not inferior | 1 (2.78) | 10 (29.41) | |||

| Psychiatric illness | |||||

| Absent | 35 (97.22) | 27 (79.41) | 5.48 | 1 | 0.019 |

| Present | 1 (2.78) | 7 (20.58) |

SD – Standard deviation

DISCUSSION

We believe that this is the first prospective study from India on tapentadol abuse or dependence with a reasonably large sample. The PA of the study shows the prevalence of tapentadol abuse and dependence in the clinic, whereas the RA reflects an apparently increasing trend of use in the treatment seekers. Nearly 3/4th of the total 96 patients with tapentadol use were identified during the prospective study. It highlights the importance of proactive case finding and gathering additional relevant information (reason of initiation, subjective psychoactive effect, etc.) for better case profiling in patients with an emerging substance of abuse.

Majority of the PA patients were using tapentadol as a substitute for the usual opioids. This result, in contradiction to that of a recent study from southern India,[4] might reflect either different opioid use profile or treatment-seeking pattern in the community. Previous studies from our region reported heroin and natural opioids as the most common opioids of abuse.[7,8,9] Thus, tapentadol could be responsible for sustaining opioid use during the period of nonavailability of illicit opioids. This assumption is supported as most of the patients were using immediate-release preparation and were procuring the same from pharmacies that illegally dispense tapentadol without a prescription. Mukherjee et al. reported similar results.[4]

The other clinically important finding from this study is that nearly half of the tapentadol users fulfilled the dependence criteria of ICD-10, which is in line with the findings of Mukherjee et al.[4]

Univariate analysis revealed a higher dose, longer duration, and report of a “noninferior high” of tapentadol use in the dependent group. This finding has indirect literature support. Concomitant opioid dependence was found to be the most significant risk factor for developing a dependence on prescription opioids.[10] A summary of 67 studies revealed that on an average, 22 months of prescription opioid exposure was necessary to develop opioid dependence among patients with chronic pain.[11] The differences in population might explain relatively shorter mean duration (~14 months) of tapentadol use in the D group. The significantly higher psychiatric comorbidity in the D group is in line with the findings of a systematic review, showing that prescriptions of psychotropic medications had increased and absence of major depressive episode had decreased the risk of opioid addiction among prescription opioid users.[10]

The varying source of tapentadol in the subgroups is an interesting finding. Research suggests that difference in sources may be related to motivation for use. A study among street-based drug users of New York reported drug dealers as the predominant source of oxycontin in users taking it to get “high,” whereas those taking oxycontin for pain would primarily get it from the pharmacies.[12]

Around 40% of cases were prescribed tapentadol by a doctor, possibly to treat withdrawal symptoms. This practice raises concern for diversion and use of nonevidence-based treatment for opioid dependence. Volkow and McLellan asserted that in the USA, the major source of diverted pharmaceutical opioids was physicians' prescription.[13] A reason for nonevidence-based prescriptions could be the overt legal restriction on the availability of opioid agonist treatment in India.[14] Therefore, we should ensure physicians' education and awareness, prescription monitoring, and improved access and availability of evidence-based treatment to address the problem.

There were some limitations to the present study: (1) the findings may not be generalizable to the community; (2) longitudinal data would help to predict the use pattern; and (3) the disproportionately less number of patients in the RA suggests that a large number of cases might have been missed.

CONCLUSION

With its unrestricted availability, tapentadol is causing concern among medical professionals in India as it is emerging as a substitute for illicit pharmaceutical opioids. Both from the policy and the clinical perspectives, India needs awareness promotion, training, availability restriction, and provision of treatment for tapentadol abuse or dependence.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ambekar A, Agrawal A, Rao R, Mishra AK, Khandelwal SK, Chadda RK. On behalf of the group of Investigators for the National Survey on Extent and Pattern of Substance Use in India. Magnitude of Substance Use in India. New Delhi: Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment, Government of India; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chang EJ, Choi EJ, Kim KH. Tapentadol: Can it kill two birds with one stone without breaking windows? Korean J Pain. 2016;29:153–7. doi: 10.3344/kjp.2016.29.3.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Basu A, Mahadevan J, Ithal D, Selvaraj S, Chand PK, Murthy P. Is tapentadol a potential Trojan horse in the postdextropropoxyphene era in India.? Indian J Pharmacol. 2018;50:44–6. doi: 10.4103/ijp.IJP_21_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mukherjee D, Shukla L, Saha P, Mahadevan J, Kandasamy A, Chand P, et al. Tapentadol abuse and dependence in India. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;49:101978. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.101978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Diagnostic Criteria for Research. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brady KT, McCauley JL, Back SE. Prescription opioid misuse, abuse, and treatment in the United States: An update. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173:18–26. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15020262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Avasthi A, Basu D, Subodh BN, Gupta PK, Malhotra N, Rani P, et al. Pattern and prevalence of substance use and dependence in the Union Territory of Chandigarh: Results of a rapid assessment survey. Indian J Psychiatry. 2017;59:284–92. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_327_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Avasthi A, Basu D, Subodh BN, Gupta PK, Sidhu BS, Gargi PD, et al. Epidemiology of substance use and dependence in the state of Punjab, India: Results of a household survey on a statewide representative sample. Asian J Psychiatr. 2018;33:18–29. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2018.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ambekar A, Kumar R, Rao R, Agrawal A, Kumar M, Mishra AK. Punjab Opioid Dependence Survey. 2015. [Last accessed on 2018 Sep 19]. Available from: http://www.pbhealth.gov.in/scan0003%20(2).pdf .

- 10.Klimas J, Gorfinkel L, Fairbairn N, Amato L, Ahamad K, Nolan S, et al. Strategies to identify patient risks of prescription opioid addiction when initiating opioids for pain: A systematic review. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:e193365. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.3365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fishbain DA, Cole B, Lewis J, Rosomoff HL, Rosomoff RS. What percentage of chronic nonmalignant pain patients exposed to chronic opioid analgesic therapy develop abuse/addiction and/or aberrant drug-related behaviors? A structured evidence-based review. Pain Med. 2008;9:444–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2007.00370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davis WR, Johnson BD. Prescription opioid use, misuse, and diversion among street drug users in New York City. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;92:267–76. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Volkow ND, McLellan AT. Opioid abuse in chronic pain--Misconceptions and mitigation strategies. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1253–63. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1507771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rao R. The journey of opioid substitution therapy in India: Achievements and challenges. Indian J Psychiatry. 2017;59:39–45. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_37_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]