Abstract

Background

Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP) is a condition specific to pregnancy, leading to increased fetal morbidity and mortality. Nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) may be a factor regulating the vasodilation of blood vessels, which are relevant to ischemic-hypoxic conditions. We aimed to explore the potential relationship between iNOS and ICP.

Material/Methods

A prospective, case-control study was conducted including 77 pregnant women with ICP and 80 healthy pregnant women as controls. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays were used to investigate maternal plasma iNOS levels. The placenta mRNA levels and cell-specific localization of iNOS were determined by quantitative polymerase chain reaction, western blotting, and immunohistochemical analysis. A multivariate linear regression model was used to identify the independent factors of serum total biliary acids (TAB) in ICP.

Results

Compared with controls, the expression of iNOS was significantly lower in maternal serum and placentas with ICP (P<0.001). Maternal plasm iNOS levels were negatively correlated with TAB (r=−0.450, P<0.001), cholyglycine (r=−0.367, P<0.001), alanine aminotransferase (r=−.359, P<0.001), and aspartate aminotransferase (r=−0.329, P<0.001). iNOS level was an indicator for ICP by multivariate linear regression analysis (β=−0.505, P<0.001). The ROC curve indicated the optimal cut-off level for iNOS was 2865.43 pg/mL (sensitivity, 85.71%; specificity, 63.75%). The ROC curve area for iNOS was 0.793 (95% CI 0.722–0.864).

Conclusions

iNOS plays an important role in poor fetoplacental vascular perfusion and adverse pregnancy outcomes. iNOS can provide complementary information in predicting the extent and severity of ICP.

Keywords: Area Under Curve, Nitric Oxide Synthase, Pregnancy Complications

Background

Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP) is a medical condition that mostly occurs in the third trimester, with a prevalence ranging from 0.1% to 15.6% worldwide [1,2]. It presents most often in the form of pruritus in the third trimester of pregnancy, with elevated serum liver aminotransferase activity and total bile acid (TBA) levels (>10 μmol/L) [3]. ICP can lead to several adverse pregnancy outcomes, including intrauterine growth retardation (IUGR), premature birth (20–60%), intrauterine asphyxia (up to 44%), and even sudden intrauterine death (0.13–3.44%) [4]. Biochemical surveillance methods and regular assessments of fetal uterine growth are often used to identify a worsening condition, despite a lack of good evidence [5,6].

It is currently believed that the pathogenesis of ICP may be associated with genetic variation, ethnicity, immune imbalance, raised steroid hormone levels, and environmental factors [7]. However, the etiology of ICP and the causes of maternal and infant adverse outcomes remain unclear. Recently, many studies have found that vasorelaxation factors can play an important role in the pathogenesis of ICP [8,9]. Recent studies have revealed that inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) might be related to ICP-related fetal complications [10]. There is a significant decrease in the expression of iNOS in patients with ICP. Nitric oxide (NO) plays an important role in increasing uterine blood flow and is produced biologically by iNOS and secreted by the placenta [11]. NO is one of the most important vasodilator factors that can improve uterine placental blood flow [12]. The iNOS/NO system may participate in the cascade reaction of ischemia and hypoxia [13].

Our team has been involved for many years in studying the vascular vasodilatation of ICP and the contribution of iNOS to this condition. The purpose of our study was to detect the expression of iNOS in maternal serum and placentas of patients with ICP and to investigate whether any other clinical indexes have diagnostic values for the prediction of adverse pregnancy outcomes.

Material and Methods

Patient Selection

The study was conducted over a period of 2 years from January 2015 to October 2017. We designed a case-control study and collected clinical data and samples from 77 cases of pregnant women with ICP and 80 cases of healthy pregnant women in their third trimester of pregnancy. The protocol of this study was approved by the Ethics Committee of our university and hospital. Each participant signed an informed consent.

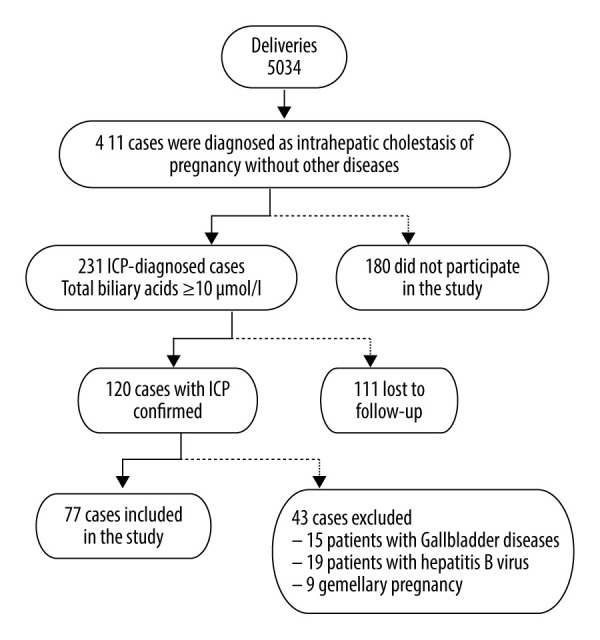

The diagnosis of ICP was made according to the following criteria: (1) unexplained pruritus during the second trimester, which resolved after delivery; (2) TBA >10 μmol/L in maternal serum; (3) the presence of abnormalities in liver function tests suggestive of ICP: serum levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) >40 U/L or aspartate aminotransferase (AST) >40 U/L; (4) total bilirubin (TBIL) was normal or increased (>20 μmol/L), and no other causes could be found for the hepatic dysfunction. The participants in the control group had no chronic diseases or gestational complications. None of the participants had a history of smoking. As illustrated in Figure 1, 77 women with ICP were enrolled in our study.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP) cases included in the study. Flow chart showing the ICP cases at the Affiliated Suzhou Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, Suzhou Municipal Hospital from January 2015 to October 2017, and reasons for the exclusion of some cases from the study.

Preparation of Samples

During the antenatal care in the third trimester, samples of 10 mL of venous blood were obtained from all of the pregnant women. Processing involved centrifugation at 35 000 g for 10 min at 4°C and storage at −80°C until analysis. Placental tissues for the experiment were collected immediately after delivery of the placenta. A section of the placental tissue was frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C and the other section was fixed in 10% formalin for immunohistochemistry.

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay

Serum markers, including TBA, cholyglycine (CG), AST, ALT, and TBIL, were measured in a batch without dilution by using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (Beckman Coulter, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. iNOS was quantitated using an ELISA kit (Signalway Antibody, USA). The optical density was measured at 450 nm (BioRad, USA).

Hematoxylin and Eosin Staining and Immunohistochemistry Analysis

Paraffin blocks made from placental tissues were collected and the sections were used for hematoxylin and eosin staining (H&E) and for immunohistochemical examinations. Tissue sections 4 μm in thickness were cut from the paraffin-embedded tissues and mounted on slides. Then, they were deparaffinized in xylene, dehydrated in alcohol, and stained with H&E staining.

Immunostaining was performed using a streptavidin-peroxidase method. Hydrogen peroxide was used to block endogenous peroxidase activity after antigen retrieval. Sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with the diluted primary antibody against human iNOS (Cell Signaling Technology, USA). The next day, the sections were washed 3 times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and then incubated with goat anti-rabbit antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, USA) overnight at 4°C. A brown color was developed with diaminobenzidine (DAB kit, Abcam, UK), then the slides were counterstained with Mayer’s hematoxylin solution and dehydrated with alcohol. Finally, the placental sections were sealed with neutral resin and examined microscopically.

For the quantification analyses, we used Image Pro Plus 6.0 software (Media Cybernetics, Rockville, MD). Each specimen of placental tissue was photographed in 5 non-repeating areas under a 40-fold objective lens (Olympus IX70 microscope, Japan). The brown-yellow areas of tissue cells were considered positive expressions of iNOS. The expression intensity was measured by the average density (integral optical density/area of the target region [IOD/area]).

Western Blotting

The placental tissues were extracted to obtain protein by using a protein extraction kit. The bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay (Pierce, Rockford, USA) was utilized to determine the protein concentration. Fifty micrograms of protein were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes for 70 min. The membranes were blocked in PBS-Tween for 2 h, incubated overnight at 4°C, washed with PBS 3 times (10 min per time), and incubated with secondary antibody at room temperature. To control the sampling error, the band intensities of β-actin were used as a control. Images were captured using a luminescence/fluorescence imaging system (GE Healthcare).

Quantitative Real-Time Reverse Transcription-Polymerase Chain Reaction

Quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) was done on the ABI Prism 7500 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems). Total RNA was extracted by Trizol reagent from placental tissues. The PCR mixture consisted of 2.5 μL 10×buffer, 1.0 μL of each primer (10 μM/μL), 0.35 μL 10 mM dNTP mix, 2.0 μL cDNA, 0.5 μL 10 μM probe, and 5 μL distilled water. The primer sequences of iNOS were forward CAGGGTGTTGCCCAAACTG and reverse GGCTGCGTTCTTCTTTGCT. The PCR samples were denatured at 94°C for 2 min, annealed at 45°C for 2 min, and prolonged at 72°C for 5 min. The mRNA levels of iNOS were measured by the Ct value (threshold cycle), and the relative expression levels were calculated with the 2−ΔΔCt method.

Data Analysis and Statistics

SPSS 21.0 software was used for statistical analyses. Quantitative data were presented as the mean±standard deviation. The Mann-Whitney U test and 2-sided t test were used to compare the variables between the 2 groups, according to the normality distribution. The chi-square test was used for qualitative data analysis. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was used to evaluate the diagnostic performance of iNOS. The P value <0.05 at a 95% confidence interval (CI) was considered statistically significant.

Results

Clinical Findings

The clinical characteristics of the 157 study participants are presented in Table 1. There were no statistically significant differences in obstetric characteristics such as age, body mass index, gravidity, and parity between the control and ICP groups (P>0.05). TBA, ALT, AST and CG levels of the ICP group were higher than those of the control group (P<0.001). The iNOS levels were found to be normally distributed in maternal serum, which was statistically significantly lower in the ICP group than in the control group (2337.70±483.46 pg/mL vs 3073.77±457.16 pg/mL, P<0.001). Gestational age at delivery was lower in the ICP group than in the control group (P<0.001). In the ICP group, the rates of cesarean section, fetal intrauterine distress (FIUD), preterm delivery, IUGR, and neonatal unit admission were higher (P<0.001).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of women with intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP) and normal pregnancies.

| Parameter (mean±SD) | Normal (n=80) | ICP (n=77) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at delivery (years) | 28.97±4.43 | 28.62±4.48 | NS |

| BMI before pregnancy (kg/m2) | 26.35±2.27 | 24.81±3.29 | NS |

| Gravidity | 1.96±1.07 | 2.05±1.06 | NS |

| Parity | 1.30±0.46 | 1.24±0.43 | NS |

| GA at delivery (week) | 38.70±1.31 | 37.21±1.47 | p<0.001 |

| TBA (μmol/L) | 6.89±1.82 | 29.71±19.04 | p<0.001 |

| CG (μmol/L) | 9.40±3.95 | 27.50±18.20 | p<0.001 |

| ALT (U/L) | 28.19±10.24 | 72.90±67.09 | p<0.001 |

| AST (U/L) | 24.35±12.57 | 84.22±70.07 | p<0.001 |

| TB (μmol/L) | 9.09±3.43 | 14.88±7.44 | p<0.001 |

| CB (μmol/L) | 2.51±1.90 | 4.45±3.62 | p<0.001 |

| UCB (μmol/L) | 6.65±2.32 | 10.40±4.76 | p<0.001 |

| TC | 4.30±1.30 | 5.97±1.68 | p<0.001 |

| TG | 2.21±1.03 | 3.12±1.32 | p<0.001 |

| iNOS (pg/ml) | 3073.77±457.16 | 2337.70±483.46 | p<0.001 |

| Rate of caesarean section | 18.75% | 48.05% | p<0.001 |

| Birth weight (g) | 3386.97±412.03 | 3120.10±413.52 | p<0.001 |

| Placnetal weight (g) | 518.99±61.42 | 478.44±77.23 | p<0.001 |

| APGAR Score | |||

| 1st min | 10 (10, 10) | 9 (9, 10) | p<0.001 |

| 5th min | 10 (10, 10) | 9 (9, 10) | p<0.001 |

| FIUD | 3.75% | 12.99% | 0.034 |

| Preterm delivery | 5.00% | 16.88% | 0.021 |

| IUGR | 3.75% | 14.29% | 0.025 |

| Neonatal unit admission | 8.75% | 16.56% | 0.009 |

BMI – body mass index; GA – Gestational age; TBA – total bile acid; CG – Cholyglycine, ALT – alanine transaminase; AST – aspartate transaminase; TB – total bilirubin; CB – conjugated bilirubin; UCB – unconjugated bilirubin; TC – total cholesterol; TG – triglyceridel FIUD – fetal distress in uterus; IUGR – intrauterine growth retardation. Results are expressed as mean±standard error of the mean. APGAR Scores were expressed as median (interquartile range). p<0.05 indicates significance.

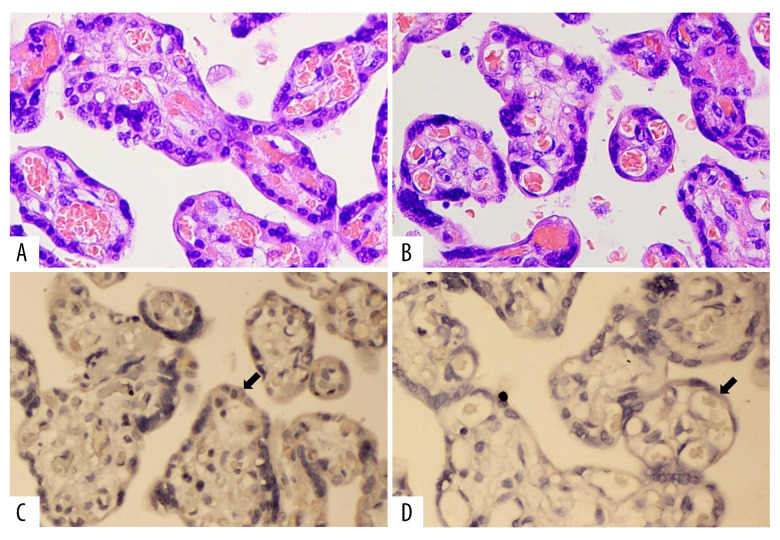

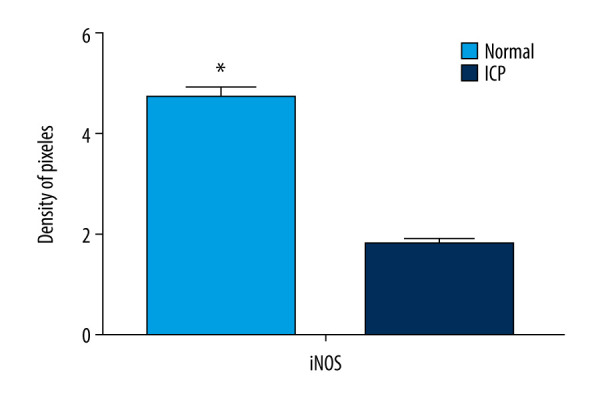

iNOS Localization and Protein Expression in Human Placenta Tissues

The localization of iNOS in placental tissues in the 2 groups was investigated by immunohistochemistry. Our results showed that iNOS was expressed in the cytotrophoblastin, syncytiotrophoblast, and vascular endothelium cells in the placentas (Figure 2). The expression of iNOS was significantly lower in ICP placental tissues than in the normal placental tissues (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

(A) Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of the control group (HE×400). (B) H&E staining of cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP) group (HE×400). (C) Immunohistochemical staining of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) in the control group (IHC×400). (D) Immunohistochemical staining of iNOS in ICP group (IHC×400).

Figure 3.

Quantitative data concerning inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) in placental tissues. iNOS immunostaining as indicated by integral optical density/area of the target region (IOD/area). The mean value was significantly different from that of cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP) group (* P<0.05).

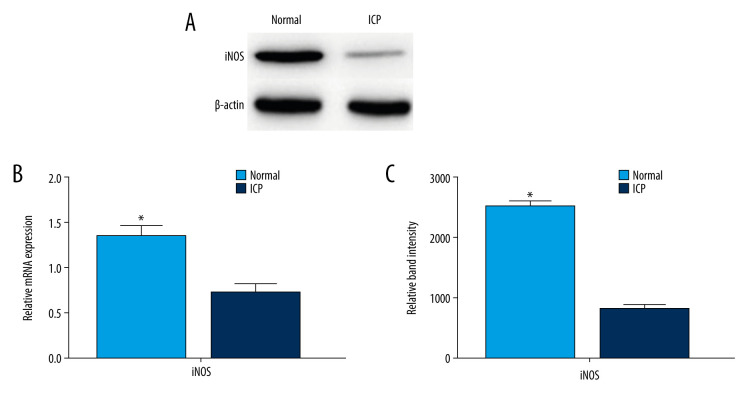

Expression of iNOS mRNA in Human Placenta Tissues

Quantitative RT-PCR was used to examine the expression of iNOS mRNA in the placentas of the pregnant women in both groups. The levels of iNOS mRNA were significantly lower in the ICP placental tissue than in the normal placental tissue (Figure 4B). The expressions of iNOS proteins were significantly lower in ICP placental tissues than in the normal placental tissues by western blotting (Figure 4A, 4C).

Figure 4.

Protein and mRNA levels of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) in placentas from the control and cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP) groups. (A) Protein expression (western blotting) of iNOS in placental tissues. (B) Quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) showed different mRNA levels of iNOS in placental tissue from the 2 groups (* P<0.05). (C) Quantitation of western blotting (mean±SD). Western blotting showed iNOS protein levels in placental tissue from the 2 groups (* P<0.05).

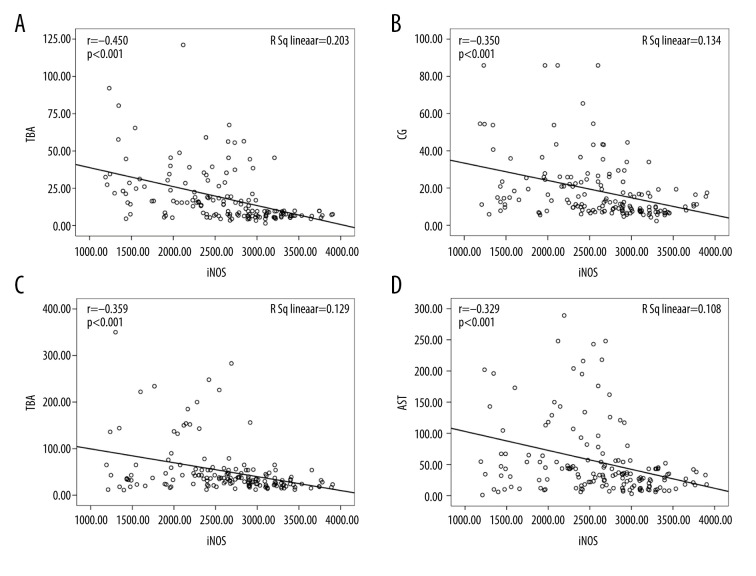

Correlations Between Serum iNOS Concentrations and Clinical Parameters

The correlations between iNOS and other indicators were not significant in either of the 2 groups. In general, iNOS was negatively correlated with liver function-related indexes, including ALT, AST, TBIL, and conjugated bilirubin (Table 2). Serum iNOS was negatively correlated with TBA (r=−0.450, P<0.001), CG (r=−0.367, P<0.001), ALT (r=−0.359, P<0.001), and AST levels (r=−0.329, P<0.001) in the women with ICP (Figure 5).

Table 2.

Bivariate correlation between inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) levels and other variables.

| iNOS | Normal | ICP | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | p-Value | r | p-Value | |

| Age at delivery (years) | 0.029 | p<0.001 | 0.085 | p<0.001 |

| BMI before pregnancy (kg/m2) | −0.040 | p<0.001 | 0.066 | p<0.001 |

| Gravidity | 0.145 | p<0.001 | 0.083 | p<0.001 |

| Parity | 0.028 | p<0.001 | 0.172 | p<0.001 |

| GA at delivery (week) | −0.157 | p<0.001 | 0.046 | p<0.001 |

| TBA (μmol/L) | −0.227 | p<0.001 | −0.514 | p<0.001 |

| CG (μmol/L) | −0.204 | p<0.001 | −0.437 | p<0.001 |

| ALT (U/L) | −0.273 | p<0.001 | −0.327 | p<0.001 |

| AST (U/L) | −0.324 | p<0.001 | −0.432 | p<0.001 |

| TB (μmol/L) | −0.122 | p<0.001 | −0.101 | p<0.001 |

| CB (μmol/L) | −0.223 | p<0.001 | −0.029 | p<0.001 |

| UCB (μmol/L) | −0.005 | 0.021 | −0.137 | p<0.001 |

| TC (mmol/L) | 0.032 | p<0.001 | −0.049 | p<0.001 |

| TG (mmol/L) | −0.150 | p<0.001 | −0.008 | p<0.001 |

| Birth weight (g) | 0.286 | p<0.001 | 0.176 | p<0.001 |

| Placnetal weight (g) | 0.214 | p<0.001 | 0.246 | p<0.001 |

| APGAR Score | ||||

| 1st min | 0.121 | p<0.001 | 0.204 | p<0.001 |

| 5th min | 0.313 | p<0.001 | 0.196 | p<0.001 |

BMI – body mass index; GA – gestational age; TBA – total bile acid, CG – cholyglycine; ALT – alanine transaminase; AST – aspartate transaminase; TB – total bilirubin; TG – triglyceride; TC – total cholesterol; CB – conjugated bilirubin; UCB – unconjugated bilirubin. p<0.05 indicates significance.

Figure 5.

Scatter plots showing the correlation between inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) levels and total bile acid (TBA), cholyglycine (CG), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) in patients with intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP). (A) Correlation between TBA levels and iNOS (r=−0.450, P<0.001); (B) correlation between CG levels and iNOS (r=−0.367, P<0.001); (C) correlation between ALT levels and iNOS (r=−0.359, P<0.001); and (D) correlation between AST levels and iNOS (r=−0.329, P<0.001).

Correlations Between TBA Concentrations and Clinical Parameters

Multivariate linear regression analysis showed that TBA level was negatively associated with iNOS (β=−0.505, P<0.001), 1-min Apgar score (β=−0.879, P<0.001), and 5-min Apgar score (β=−0.389, P<0.001). TBA was positively associated with CG (β=0.435, P<0.001), ALT (β=0.092, P<0.001), AST (β=0.064, P<0.001), TBIL (β=0.048, p<0.001), and total cholesterol (TC) (β=1.361, P<0.001) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariate linear regression analysis between total bile acid (TBA) and clinical characteristics.

| Variable | β (95% confidence interval) | SE | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at delivery(years) | −0.034 (−0.041 to−0.026) | 0.004 | 0.203 |

| BMI before pregnancy(kg/m2) | 0.589 (0.577 to 0.601) | 0.006 | 0.063 |

| Gravidity | 1.557 (1.521 to 1.592) | 0.018 | 0.201 |

| Parity | −1.790 (−1.876 to −1.704) | 0.044 | 0.161 |

| GA at delivery (week) | −1.608 (−1.632 to −1.584) | 0.012 | 0.072 |

| CG (μmol/L) | 0.435 (0.432 to 0.437) | 0.001 | p<0.001 |

| ALT (U/L) | 0.092 (0.091 to 0.093) | 0.001 | p<0.001 |

| AST (U/L) | 0.064 (0.063 to 0.065) | 0.001 | p<0.001 |

| TB (μmol/L) | 1.326 (1.231 to 1.420) | 0.048 | p<0.001 |

| CB (μmol/L) | −0.071 (−0.167 to 0.025) | 0.049 | 0.149 |

| UCB (μmol/L) | −1.092 (−1.186 to −0.998) | 0.048 | 0.061 |

| TC (mmol/L) | 1.361 (1.338 to 1.383) | 0.011 | p<0.001 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 0.263 (0.260 to 0.266) | 0.015 | 0.306 |

| iNOS (pg/ml) | −0.505 (−0.597 to −0.414) | 0.047 | p<0.001 |

| Birth weight (g) | −0.006 (−0.007 to −0.006) | 0.001 | 0.130 |

| Placnetal weight (g) | 0.003 (0.003 to 0.004) | 0.001 | 0.392 |

| APGAR Score | |||

| 1st min | −0.879 (−0.925 to−0.832) | 0.024 | p<0.001 |

| 5th min | −0.315 (−0.389 to −0.241) | 0.038 | p<0.001 |

BMI – body mass index; GA – gestational age; TBA – total bile acid; CG – cholyglycine; ALT – alanine transaminase; AST – aspartate transaminase; TB – total bilirubin; TG – triglyceride; TC – total cholesterol; CB – conjugated bilirubin; UCB – unconjugated bilirubin.

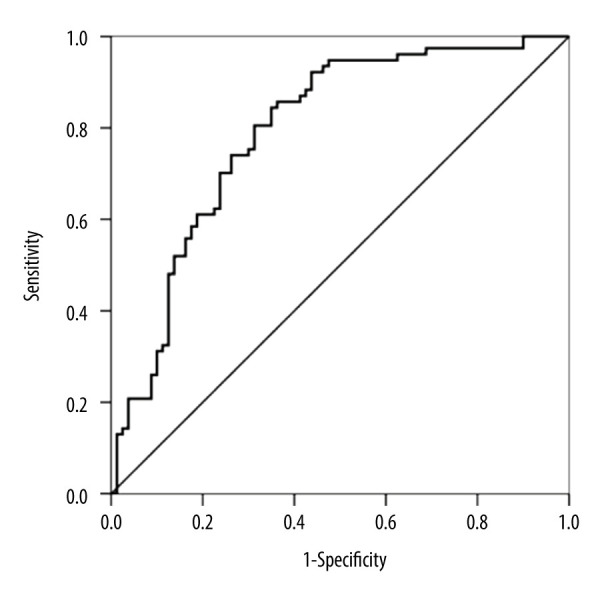

ROC Curves

In our study, the ability of iNOS to detect ICP was assessed using ROC curves. According to the ROC curve, the optimal cut-off level for iNOS was 2865.43 pg/mL (sensitivity, 85.71%; specificity, 63.75%). The ROC curve area for iNOS was 0.793 (95% CI 0.722–0.864) (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) value for cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP) diagnosis. (AUC=0.793 [95% CI 0.722–0.864], P<0.001).

Discussion

ICP is a liver disease of pregnancy that increases fetal morbidity and mortality; therefore, making an early diagnosis and assessment of the severity of the disease is important. Patients with ICP have an increased risk of adverse perinatal outcomes, such as decreased Apgar score, FIUD, preterm delivery, IUGR, and neonatal unit admission. The blood supply of the uterus and placenta in patients with ICP can be insufficient, which can affect the growth and development of the fetus and cause hypoxia. The etiology and pathogenesis of ICP are unknown; however, potential causes of ICP are considered to be related to female hormones, genetic predisposition, and environmental factors. All factors involved can explain the disease to some extent; however, at present, there are few indicators for the prediction of ICP. It has been reported that the AST/platelet count ratio in the first trimester can predict the incidence of ICP, but this needs to be verified by large-sample experiments [14]. Recent studies demonstrated increased circulating levels of systemic and vascular active factors in pregnancies with ICP [15]. In this study, we aimed to investigate the associations between iNOS and ICP.

In our study, a variety of experimental methods were used to detect the expression of iNOS in the human maternal plasma and placenta. iNOS has been found to be highly expressed in cholangiocarcinomas and in primary sclerosing cholangitis [16]. Khalid et al [17] showed that the upregulation of endothelial (e)NOS occurs in the thoracic aortas of rats with biliary cirrhosis. Despite the conflicting findings, eNOS activity in the cirrhotic liver is consistently reported to be decreased [18,19]. The investigation by Zimmermann et al showed that eNOS is decreased in the hepatocytes of secondary biliary fibrosis [20]. We found that iNOS protein and mRNA were significantly downregulated in ICP maternal plasma and placentas. iNOS protein was predominantly stained in cytotrophoblastin, syncytiotrophoblast, and vascular endothelium cells by immunohistochemistry analysis. In the second and third trimester of pregnancy, the fetal-placental resistance gradually decreases to ensure the normal growth of the fetus. It is well known that NO plays an important role in dilating blood vessels and ensuring enough blood flow to the fetus and is secreted by the placenta and synthesized by iNOS as a rate-limiting enzyme [21,22]. NO is an unstable gas, and its half-life period is only 20 s to 30 s, in general. This crucial role of NO relies on its effect on the vascular smooth muscle. Some studies have shown that NO at the maternal-fetal interface may affect fetal development [23]. Downregulated iNOS expression in ICP maternal serum and placenta might lead to the dysfunction of vascular vasodilatation and result in poor utero-placental-fetal perfusion and fetal hypoxia, or even sudden intrauterine deaths. This suggests that normal blood flow due to iNOS released from the placenta plays a significant role in the pathogenesis of ICP.

TBA and other liver function tests (TBIL, direct bilirubin, ALT, AST, and CG), combined with the typical symptoms of pruritus and jaundice are important criteria for the diagnosis of ICP. TBA is an important indicator to identify the severity and prognosis of ICP. Many studies had found that with a higher TBA level, there is a higher rate of adverse perinatal outcomes [24,25]. Because elevated TBA is not obvious or is later abnormal in some patients with liver dysfunction or pruritus, it is particularly important to evaluate a patient’s condition by testing iNOS levels. In the present study, the lower concentration of iNOS was a marker of increased ICP risk. Geenes et al reported higher rates of preterm delivery with higher levels of serum transaminases, especially ALT [26]. Our present study had similar results as previous studies. In the present study, ALT, AST, TBIL, TC, and unconjugated bilirubin levels were significantly higher in patients with ICP than in the control group. The activity of transaminases and conjugated bilirubin concentration were considerably higher in patients with ICP. Patients with ICP and elevated transaminases have a higher number of adverse pregnancy outcomes and should be followed up regularly [27].

We found that low Apgar scores and FIUD were positively correlated with TBA levels in patients with ICP. This finding is consistent with the results of other studies suggesting a relationship between TBA and neonatal respiratory distress syndrome, as they can affect the synthesis of alveolar surface active substances [28]. Fetal asphyxia in the newborns of women with ICP has been reported frequently in the literature [29]. Zecca et al [30] reported that the incidence of respiratory distress syndrome in infants from mothers with ICP was almost double that of the control group. Furthermore, our results confirmed the lower levels of iNOS in patients with ICP and its negative relationship with TBA, CG, ALT, and AST. We found that elevated TC and triglyceride (TG) levels could be useful biomarkers for the early identification of ICP. These results have the potential to provide insights into strategies to diagnose and treat ICP. The symptoms of ICP disappear shortly after birth, which is probably associated with an imbalance of some sulfated progesterone metabolites such as estrogen/progesterone and a vasoactive substance.

There were no stillbirths in our study even though we did not perform elective delivery before full term. This may have been due to our strict antenatal examination, drug therapy, and close fetal monitoring. Our study revealed that iNOS played an important role in the development and progression of ICP, and underexpressed iNOS was positively associated with the severity of ICP and low Apgar scores. Therefore, we believe that iNOS may be a potential target for ICP therapy.

Conclusions

The underexpression of iNOS, especially with elevated TBA, ALT, and TG levels, seemed to be associated with adverse perinatal outcomes in patients with ICP, particularly those with IUGR and preterm delivery. Our data suggest that iNOS might serve as a beneficial factor associated with the development of ICP. This study provides evidence that the expression of iNOS in ICP may enable obstetricians to diagnose ICP. This will provide a new perspective for the study of ICP.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients who kindly donated their placentas for this study.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

None.

Source of support: This study was supported by the Clinical Medical Expert Team Project of Suzhou (grant No. SZYJTD201709) and Suzhou Science and Technology Plan Research Project (grant No. SYSD2017101)

References

- 1.Arrese M, Reyes H. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: A past and present riddle. Ann Hepatol. 2006;5(3):202–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Joshi D, James A, Quaglia A, et al. Liver disease in pregnancy. Lancet. 2010;375(9714):594–605. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61495-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kenyon AP, Piercy CN, Girling J, et al. Pruritus may precede abnormal liver function tests in pregnant women with obstetric cholestasis: A longitudinal analysis. BJOG. 2001;108(11):1190–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2003.00281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ovadia C, Seed PT, Sklavounos A, et al. Association of adverse perinatal outcomes of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy with biochemical markers: Results of aggregate and individual patient data meta-analyses. Lancet. 2019;393:899–909. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31877-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Geenes V, Chappell LC, Seed PT, et al. Association of severe intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy with adverse pregnancy outcomes: A prospective population-based case-control study. Hepatology. 2014;59(4):1482–91. doi: 10.1002/hep.26617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wikström SE, Marschall HU, Ludvigsson JF, et al. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy and associated adverse pregnancy and fetal outcomes: A 12-year population-based cohort study. BJOG. 2013;120(6):717–23. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hu Y, Wang D, Liu S, et al. immunologic abnormality of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2010;63(4):267–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2009.00798.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yayla Abide C, Vural F, Kilicci C, et al. Can we predict severity of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy using inflammatory markers? Turk J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;14(3):160–65. doi: 10.4274/tjod.67674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yong S, Jing C, Jiao Z, et al. Effect of histone deacetylase HDAC3 on cytokines IL-18, IL-12 and TNF-α in patients with intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2017;42(4):1294–302. doi: 10.1159/000478958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang X, Ding YL. [ Relationship of the occurrence of fetal distress and change of umbilical cord and expression of vasoactive substance in umbilical vein in intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy]. Zhonghua Fu Chan Ke Za Zhi. 2008;43(2):85–89. [in Chinese] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abdel-Razik M, El-Berry S, Mostafa A. The effects of nitric oxide donors on uterine artery and sub-endometrial blood flow in patients with unexplained recurrent abortion. J Reprod Infertil. 2014;15(3):142–46. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Valdes G, Kaufmann P, Corthorn J, et al. Vasodilator factors in the systemic and local adaptations to pregnancy. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2009;7:79. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-7-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gilbert JS, Ryan MJ, LaMarca BB, et al. Pathophysiology of hypertension during preeclampsia: Linking placental ischemia with endothelial dysfunction. Am J Physiol Heart Cir Physiol. 2008;294(2):H541–50. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01113.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tolunay HE, Kahraman NÇ, Varlı EN, et al. First-trimester aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index in predicting intrahepatic cholestasis in pregnancy and its relationship with bile acids: A pilot study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2020;11(256):114–17. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2020.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Biberoglu E, Kirbas A, Daglar K, et al. Role of inflammation in intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. J Obstet Gynecol Res. 2016;42(3):252–57. doi: 10.1111/jog.12902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jaiswal M, Larusso NF, Shapiro RA, et al. Nitric oxide-mediated inhibition of DNA repair potentiates oxidative DNA damage in cholangiocytes. Gastroenterology. 2001;120(1):190–99. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.20875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tazi KA, Barrière E, Moreau R, et al. Role of shear stress in aortic eNOS up-regulation in rats with biliary cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2002;122(7):1869–77. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.33586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sarela AI, Mihaimeed FM, Batten JJ, et al. Hepatic and splanchnic nitric oxide activity in patients with cirrhosis. Gut. 1999;44(5):749–53. doi: 10.1136/gut.44.5.749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shah V, Toruner M, Haddad F, et al. Impaired endothelial nitric oxide synthase activity associated with enhanced caveolin binding in experimental cirrhosis in the rat. Gastroenterology. 1999;117(5):1222–28. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70408-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zimmermann H, Kurzen P, Klossner W, et al. Decreased constitutive hepatic nitric oxide synthase expression in secondary biliary fibrosis and its changes after Roux-en-Y choledocho-jejunostomy in the rat. J Hepatol. 1996;25(4):567–73. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(96)80218-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Storment JM, Meyer M, Osol G. Estrogen augments the vasodilatory effects of vascular endothelial growth factor in the uterine circulation of the rat. Am J Obstet Gyneco. 2000;183(183):449–53. doi: 10.1067/mob.2000.105910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blanco S, Hernández R, Franchelli G, et al. Melatonin influences NO/NOS pathway and reduces oxidative and nitrosative stress in a model of hypoxic-ischemic brain damage. Nitric Oxide. 2017;30(62):32–43. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2016.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abdelrazik M, Elberry S, Mostafa A. The effects of nitric oxide donors on uterine artery and sub-endometrial blood flow in patients with unexplained recurrent abortion. J Reprod Infertil. 2014;15(3):142–46. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Estiú MC, Frailuna MA, Otero C, et al. Relationship between early onset severe intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy and higher risk of meconium-stained fluid. PLoS One. 2017;12(4):e0176504. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0176504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang H, Hu M, Chen J. Maternal and fetal outcomes of women with intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Chin J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;51(7):535–37. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Geenes V, Chappell LC, Seed PT, et al. Association of severe intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy with adverse pregnancy outcomes: A prospective population based case-control study. Hepatology. 2014;59(4):1482–91. doi: 10.1002/hep.26617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ekiz A, Kaya B, Avci ME, et al. Alanine aminotransferase as a predictor of adverse perinatal outcomes in women with intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Pak J Med Sci. 2016;32(2):418–22. doi: 10.12669/pjms.322.9057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zecca E, DeLuca D, Barbato G, et al. Predicting respiratory distress syndrome in neonates from mothers with intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Early Hum Dev. 2008;84(5):337–41. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2007.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kebapcilar AG, Taner CE, Kebapcilar L, et al. High mean platelet volume, low-grade systemic coagulation, and fibrinolytic activation are associated with pre-term delivery and low Apgar score in intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2010;23(10):1205–10. doi: 10.3109/14767051003653278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zecca E, De LD, Marras M, et al. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy and neonatal respiratory distress syndrome. Pediatrics. 2006;117(5):1669–72. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]