Abstract

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) of esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC) and its precursor, Barrett’s esophagus (BE), have uncovered significant genetic components of risk, but most heritability remains unexplained. Targeted assessment of genetic variation in biologically relevant pathways using novel analytical approaches may identify missed susceptibility signals. Central obesity, a key BE/EAC risk factor, is linked to systemic inflammation, altered hormonal signaling and insulin-like growth factor (IGF) axis dysfunction. Here, we assessed IGF-related genetic variation and risk of BE and EAC. Principal component analysis was employed to evaluate pathway-level and gene-level associations with BE/EAC, using genotypes for 270 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in or near 12 IGF-related genes, ascertained from 3295 BE cases, 2515 EAC cases and 3207 controls in the Barrett’s and Esophageal Adenocarcinoma Consortium (BEACON) GWAS. Gene-level signals were assessed using Multi-marker Analysis of GenoMic Annotation (MAGMA) and SNP summary statistics from BEACON and an expanded GWAS meta-analysis (6167 BE cases, 4112 EAC cases, 17 159 controls). Global variation in the IGF pathway was associated with risk of BE (P = 0.0015). Gene-level associations with BE were observed for GHR (growth hormone receptor; P = 0.00046, false discovery rate q = 0.0056) and IGF1R (IGF1 receptor; P = 0.0090, q = 0.0542). These gene-level signals remained significant at q < 0.1 when assessed using data from the largest available BE/EAC GWAS meta-analysis. No significant associations were observed for EAC. This study represents the most comprehensive evaluation to date of inherited genetic variation in the IGF pathway and BE/EAC risk, providing novel evidence that variation in two genes encoding cell-surface receptors, GHR and IGF1R, may influence risk of BE.

We report that germline variation in the IGF pathway, particularly in GHR and IGF1R genes, may alter risk of BE. This implicates IGF axis dysregulation in the etiology of this obesity-related cancer precursor, uncovering novel candidate mediators of BE susceptibility.

Introduction

Despite diagnostic and therapeutic advances over recent decades, esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC) remains one of the most lethal of all cancers, with a median survival of less than 1 year (1–4). EAC arises from an epithelial precursor lesion, Barrett’s esophagus (BE). Gastroesophageal reflux, central obesity, tobacco smoking, male sex and European ancestry are well-established BE/EAC risk factors (5,6). Inherited genetics represents another important contributor to disease etiology. In the last 8 years, genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified nearly 20 susceptibility loci for BE/EAC and revealed substantial heritable components (h2 ~ 25–35%) of risk (7–12). Nevertheless, the majority of heritability remains unexplained, underscoring the need for further discovery efforts. To maximize the value of existing GWAS data, we and others have adopted pathway-level and gene-level approaches to aggregate distributed genetic signals, reduce dimensionality and boost statistical power to detect further associations. Post-GWAS assessments have identified additional candidate susceptibility genes, such as MGST1 and CDKN2A, in biologically plausible pathways (e.g. inflammation and tumor suppression) related to BE/EAC pathogenesis (13,14).

Strong epidemiologic associations between central obesity and risk of BE/EAC have suggested a potential role for metabolic signaling disturbances, such as in the insulin-like growth factor (IGF) axis, in the pathophysiology of BE/EAC (15–19). Visceral fat is known to affect glucose and lipid metabolism, and alter levels of bioactive molecules and hormones such as insulin, IGFs and pro-inflammatory cytokines (20). Such hormonal and pro-inflammatory alterations may lead to a dysfunctional IGF system, which has been associated with risk of multiple cancers, including breast, colorectal, prostate, lung and ovary (21–25). The core IGF pathway comprises growth hormone (GH), the growth hormone receptor (GHR), ligand proteins, insulin-like growth factors 1 and 2 (IGF1, IGF2), insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor (IGF1R) and six IGF binding proteins (IGFBP1–IGFBP6) (Supplementary Figure S1) (26). The binding of circulating GH to GHR, which is expressed on the cell surface in multiple tissues, triggers the intracellular synthesis of IGF1, the primary downstream effector. IGF1 in circulation is bound to IGFBPs, which are cleaved at target organ sites, allowing free IGF1 to bind IGF1R and promote tissue growth. Pathway hyperactivation supports risk of transformation and tumorigenesis through promotion of cellular proliferation and angiogenesis, and reduction of apoptosis (26).

Additional lines of evidence have implicated the IGF pathway in esophageal carcinogenesis. Immunohistochemical assessment of patient specimens revealed elevated IGF1R protein expression during BE to EAC progression (27). Studies from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) found IGF1R gene amplifications in 10% of EAC tumors analyzed (28). Upregulation of IGFBP3 has been reported in BE and EAC tissues, relative to normal esophageal epithelium, and IGFBP3 and IGFBP4 overexpression was seen in BE tissues of patients with concurrent EAC, compared with those without cancer (29). In vitro studies have demonstrated increased EAC cell-line proliferation in response to IGF1 (30). While serum IGFBP3 and IGF1 levels were not associated with EAC risk in one BE cohort (31), high serum IGF1 levels have been noted in viscerally obese EAC cases (15,30), along with increased IGF1R gene and protein expression (15).

A previous study described associations between polymorphisms in GHR and IGF1 and reduced risk of EAC and BE, respectively (32). However, this study included only a small number of cases (n < 500) from a single country (Ireland) and evaluated only ~100 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in seven IGF-related genes. Thus, comprehensive assessment of germline genetic variation in the IGF pathway is needed to understand the extent to which such variation may influence BE/EAC risk and interact with known risk factors. To address this gap, we used complementary statistical approaches to evaluate associations between IGF-related inherited variation and BE/EAC risk, with data from the Barrett’s and Esophageal Adenocarcinoma Consortium (BEACON) GWAS, and further assessed gene-level results in an expanded GWAS meta-analysis dataset.

Methods

Study populations and SNP genotyping

Detailed descriptions of study participants and GWAS datasets have been published previously (9,10). The first phase of our analysis included 2515 EAC, 3295 BE cases and 3207 controls from the BEACON GWAS (10). All participants were of European ancestry. DNA was isolated from buffy coat or whole-blood and genotyped using the Illumina Omni1M Quad platform. The second phase of our study used data from a larger GWAS meta-analysis (Supplementary Table S1), which included the BEACON GWAS participants and additional cases and controls from GWAS conducted in Germany and the United Kingdom (9). All participants were of European ancestry. DNA samples were obtained from blood or saliva and genotyped on high-density Illumina arrays (9). Informed consent was obtained from all participants in individual studies and every participating institution received ethics approval from their respective Institutional Review Boards (IRBs).

Selection of genes and SNPs

Twelve core IGF-related genes, GH1, GHR, IGF1, IGF2, IGF1R, IGFBP1, IGFBP2, IGFBP3, IGFBP4, IGFBP5, IGFBP6 and IGFALS were selected a priori for analysis. Omni1M SNPs that passed Illumina quality metrics, satisfied additional quality control criteria and had minor allele frequencies ≥1% were eligible for inclusion (10). Variants selected for analysis are located within hg19 consensus gene boundaries, or within 2.0 kb flanking sequences proximal to the transcriptional start site and distal to the 3′ untranslated region (Supplementary Table S2) (10). SHAPEIT was used to impute missing values of genotyped SNPs in the BEACON dataset (33).

Statistical analysis

A principal component analysis (PCA) framework, developed and described previously (13), was applied to examine the association between global genetic variation in the IGF pathway and the risks of BE and EAC, separately, using the BEACON GWAS genotype data. Briefly, a genotype matrix was constructed using all eligible SNPs assigned to the 12 genes under study. Each SNP genotype was coded 0, 1 or 2, based on the number of designated minor alleles, and standardized across participants to obtain a mean of 0 and SD of 1. The first N principal components (PCs) that captured ≥50% of the genetic variance were selected. A likelihood ratio test statistic was used to assess the association between genetic variation and disease risk. A full model, containing the N pathway-level PCs, age, sex and the first four PCs derived from ancestry-informative markers (PC1AIM–PC4AIM), was compared with a reduced model, containing age, sex and PC1AIM–PC4AIM only. A two-sided pathway-level P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Gene-level analysis was conducted for all genes (n = 10) with three or more eligible genotyped SNPs, based on a similar PCA approach (13). We also employed Multi-marker Analysis of GenoMic Annotation (MAGMA v1.08) as a complementary method for gene-level evaluation, using SNP summary statistics. MAGMA is a fast, flexible and robust tool for analyzing the joint associations of multiple genetic markers simultaneously while accounting for linkage disequilibrium (34,35). At the gene level, correction for multiple comparisons was conducted via the Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR) method (36). MAGMA was similarly applied to SNP summary statistics derived from the larger GWAS meta-analysis dataset (Supplementary Tables S1 and S2) (9). The Phase 3 1000 Genomes (EUR) reference dataset (hg19) was used to calculate linkage disequilibrium (37). Meta-analysis SNP-level summary data for the top two genes identified in BEACON were visualized graphically using LocusZoom plots (38) and characterized for functional potential using HaploReg and the Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project (39,40).

In exploratory studies, genetic variants in the BEACON dataset were evaluated for gene–environment interactions with BE risk factors, including sex, tobacco smoking, body mass index (BMI) and gastroesophageal reflux symptoms. We also examined interactions by waist circumference (WC: controls = 593, BE cases = 1113) and waist–hip ratio (WHR: controls = 376, BE cases = 874), in a limited subset of participants with relevant data. Based on guidelines from the World Health Organization and Centers for Disease Control, normal WHR was defined as ≤0.85 for women and ≤0.90 for men; and normal WC was defined as ≤35 inches (women) and ≤40 inches (men) (41,42). All analyses were conducted using STATA/SE V.15 (College Station, TX).

Results

Characteristics of study participants

Our primary analysis included data from 3295 BE cases, 2515 EAC cases and 3207 controls from the BEACON GWAS (10) Demographic and lifestyle characteristics of participants are presented in Table 1. BE and EAC cases were somewhat older and more often male compared with controls; obesity (BMI 30+), smoking, and reflux symptoms were more prevalent among cases versus controls.

Table 1.

Characteristics of BEACON GWAS study participants

| Controls (n = 3207) | BE cases (n = 3295) | EAC cases (n = 2515) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| <50 | 726 | 22.6 | 449 | 13.7 | 189 | 7.6 |

| 50–59 | 885 | 27.6 | 780 | 23.7 | 547 | 21.9 |

| 60–69 | 963 | 30.0 | 1011 | 30.7 | 884 | 35.4 |

| 70+ | 633 | 19.8 | 1048 | 31.9 | 875 | 35.1 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 880 | 27.4 | 806 | 24.5 | 320 | 12.7 |

| Male | 2327 | 72.6 | 2489 | 75.5 | 2195 | 87.3 |

| BMI | ||||||

| <25 | 786 | 36.3 | 608 | 22.2 | 245 | 24.6 |

| 25–29.99 | 944 | 43.6 | 1191 | 43.6 | 455 | 45.7 |

| 30–34.99 | 307 | 14.2 | 657 | 24.0 | 201 | 20.2 |

| 35+ | 130 | 6.0 | 278 | 10.2 | 95 | 9.5 |

| Smoking status | ||||||

| No | 889 | 40.9 | 1081 | 35.2 | 568 | 25.2 |

| Yes | 1284 | 59.1 | 1994 | 64.8 | 1686 | 74.8 |

| Smoking pack-years | ||||||

| None | 889 | 41.3 | 1081 | 43.6 | 568 | 30.1 |

| <15 | 358 | 16.6 | 465 | 18.8 | 319 | 16.9 |

| 15–29 | 326 | 15.1 | 348 | 14.0 | 357 | 18.9 |

| 30–44 | 273 | 12.7 | 279 | 11.3 | 308 | 16.3 |

| 45+ | 309 | 14.3 | 306 | 12.3 | 335 | 17.8 |

| Regular NSAID use | ||||||

| Never | 814 | 44.0 | 1050 | 57.7 | 559 | 33.0 |

| Ever | 1038 | 56.0 | 770 | 42.3 | 1133 | 67.0 |

| Weekly reflux/heartburn | ||||||

| No | 1448 | 80.6 | 1058 | 47.2 | 965 | 53.0 |

| Yes | 349 | 19.4 | 1186 | 52.8 | 854 | 47.0 |

Numbers may not add to total due to missing data. NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

Pathway-level associations: BEACON GWAS data

Components of the IGF pathway function biologically together as a unit, exhibiting signal amplification and feedback loops (43). To assess overall genetic variation in the IGF axis in relation to disease risk, we used a PCA-based method, and identified a significant association with risk of BE (P = 0.0015), but not EAC (P = 0.36) (Table 2). This association remained significant after application of the stringent Bonferroni correction accounting for five pathways examined in our previous publication (13) and the IGF pathway in this report (0.05/6 = 0.0083).

Table 2.

Pathway-level associations with risk of BE and EAC

| BE | EAC | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pathway | Genes | SNPsa | PCsb | P c | PCsb | P c |

| IGF | 12 | 270 | 17 | 0.0015* | 17 | 0.37 |

aNumber of SNPs selected for analysis.

bNumber of pathway-level PCs included in logistic model.

cLikelihood ratio P value.

*Indicates a significant pathway level association.

Gene-level associations: BEACON GWAS data

To further localize the pathway-level signal, we applied the PCA method at the gene level for individual IGF axis genes with three or more SNPs. Among 10 eligible genes with ≥3 SNPs, we found a significant association between variation in GHR and risk of BE (P = 0.0022, FDR q = 0.022) (Table 3A). As a complementary approach, utilizing SNP summary statistics from the BEACON GWAS, we repeated gene-level analyses using MAGMA (34,35). As in the PCA-based assessment, GHR was significantly associated with risk of BE (P = 0.00046, q = 0.0056). At FDR <0.1, a second significant signal was observed for IGF1R (P = 0.0090, q = 0.054) (Table 3B), which also ranked second in our PCA analysis (P = 0.078). Exploratory examination of gene-level associations with risk of EAC revealed nominally significant signals for IGF1 (P = 0.030) and IGFBP6 (0.048) using PCA, but these were lost after correcting for multiple comparisons (FDR = 0.24) (Supplementary Table S3A). Significant (P < 0.05) associations with risk of EAC were not observed using MAGMA (Supplementary Table S3B).

Table 3.

Assessments of IGF gene-level associations with risk of BE using BEACON GWAS data via application of (A) PCA and (B) MAGMA(A) PCA

| Gene | Gene name | Chr | SNPsa | PCsb | P c | FDR qd | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | GHR | Growth hormone receptor | 5 | 39 | 3 | 0.0022 | 0.022 |

| 2 | IGF1R | IGF1 receptor | 15 | 131 | 8 | 0.078 | 0.39 |

| 3 | IGF2 | IGF2 | 11 | 25 | 3 | 0.16 | 0.46 |

| 4 | IGFBP6 | IGF binding protein 6 | 12 | 6 | 3 | 0.18 | 0.46 |

| 5 | IGFBP3 | IGF binding protein 3 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 0.24 | 0.48 |

| 6 | IGFBP5 | IGF binding protein 5 | 2 | 16 | 3 | 0.32 | 0.50 |

| 7 | IGFBP1 | IGF binding protein 1 | 7 | 6 | 3 | 0.35 | 0.50 |

| 8 | IGFBP2 | IGF binding protein 2 | 2 | 8 | 3 | 0.47 | 0.59 |

| 9 | IGF1 | IGF1 | 12 | 25 | 3 | 0.62 | 0.62 |

| 10 | IGFALS | IGFBP acid labile subunit | 16 | 4 | 3 | 0.62 | 0.62 |

| (B) MAGMA | |||||||

| Gene | Chr | SNPsa | Pe | FDR qd | |||

| 1 | GHR | 5 | 39 | 0.00046 | 0.0056 | ||

| 2 | IGF1R | 15 | 130f | 0.0090 | 0.054 | ||

| 3 | IGFBP5 | 2 | 16 | 0.12 | 0.44 | ||

| 4 | IGF2 | 11 | 25 | 0.21 | 0.44 | ||

| 5 | IGFBP3 | 7 | 5 | 0.21 | 0.44 | ||

| 6 | IGFBP4 | 17 | 3 | 0.23 | 0.44 | ||

| 7 | IGFBP6 | 12 | 6 | 0.26 | 0.44 | ||

| 8 | GH1 | 17 | 2 | 0.40 | 0.59 | ||

| 9 | IGFALS | 16 | 4 | 0.51 | 0.65 | ||

| 10 | IGFBP1 | 7 | 6 | 0.54 | 0.65 | ||

| 11 | IGFBP2 | 2 | 8 | 0.69 | 0.75 | ||

| 12 | IGF1 | 12 | 25 | 0.77 | 0.77 |

aNumber of SNPs per gene.

bNumber of gene-level PCs included in the logistic regression model.

cLikelihood ratio P value.

dFalse discovery rate q value.

eGene-level P value.

fga012685 not included in 1000G Phase 3 EUR reference data.

Gene-level associations: GWAS meta-analysis data

To extend our analysis to a larger dataset, we acquired SNP summary statistics from a GWAS meta-analysis (described earlier) (9). Using MAGMA, we conducted gene-level analyses with summary statistics for all available variants assigned to each of the 12 IGF genes. Consistent with our previous results, at FDR <0.1 we found significant gene-level associations for GHR (P = 0.0097, q = 0.071) and IGF1R (P = 0.0176, q = 0.071) in relation to risk of BE; a third signal was identified for IGFBP3 (P = 0.0135, q = 0.071) (Table 4). Significant (P < 0.05) gene-level associations were not observed for EAC (Supplementary Table S4).

Table 4.

Assessment of gene-level associations with risk of BE using GWAS meta-analysis data via application of MAGMA

| Gene | Chr | SNPsa | P valueb | FDR qc | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | GHR | 5 | 882 | 0.0097 | 0.071 |

| 2 | IGFBP3 | 7 | 37 | 0.0135 | 0.071 |

| 3 | IGF1R | 15 | 1226 | 0.0176 | 0.071 |

| 4 | GH1 | 17 | 27 | 0.09 | 0.26 |

| 5 | IGFBP1 | 7 | 29 | 0.11 | 0.27 |

| 6 | IGFBP4 | 17 | 51 | 0.22 | 0.44 |

| 7 | IGF2 | 11 | 84 | 0.48 | 0.72 |

| 8 | IGFBP5 | 2 | 87 | 0.48 | 0.72 |

| 9 | IGF1 | 12 | 223 | 0.70 | 0.88 |

| 10 | IGFBP6 | 12 | 18 | 0.83 | 0.88 |

| 11 | IGFALS | 16 | 58 | 0.87 | 0.88 |

| 12 | IGFBP2 | 2 | 99 | 0.88 | 0.88 |

aNumber of SNPs per gene.

bGene-level P value.

cFalse discovery rate q value.

SNP-level associations and in silico functional characterization

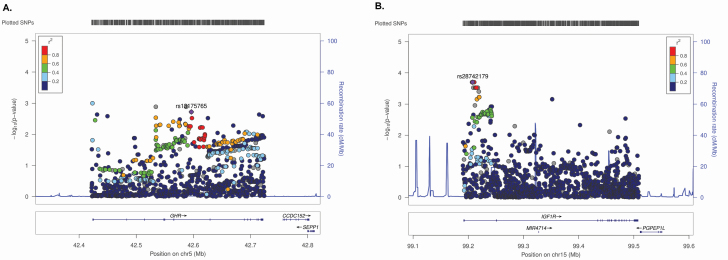

We examined odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals for the top 10 SNPs in GHR and IGF1R, ranked by GWAS meta-analysis P value (Supplementary Table S5). The strongest associations had ORs ranging between 0.42–2.69 for GHR and 0.87–1.15 for IGF1R, using a per-allele additive model. LocusZoom plots were assembled to visualize associations of all analyzed meta-analysis SNPs in these genes (Figure 1). At the GHR locus, 257 SNPs were nominally associated with risk of BE (P < 0.05). These variants were geographically scattered across the region, with no visible peaks in signal strength, suggesting that cumulative associations of multiple weak signals may account for the observed gene-level association (Figure 1A). The top GHR variants (P < 0.01) modify predicted sequence motifs for several transcription factors, including FOXP1, SOX, STAT and MEF2 (Supplementary Table S6A). We also found evidence of enhancer histone marks in the immediate vicinity of risk-associated SNPs, in the liver, which is crucial to IGF axis function, particularly IGF1 synthesis. None of the GHR SNPs remained significant at FDR q < 0.05. Of interest, 155 of the 257 SNPs satisfying P < 0.05 are expression quantitative trait loci (eQTLs) for GHR in tissues such as adipose, skeletal muscle, heart, lung, pancreas and thyroid, based on data from the Genotype-Tissue Expression Project (GTEx) (44). Of the 155, 47 are GHR eQTLs in esophageal muscularis; at each of these eQTLs, the allele associated with reduced GHR expression is also associated with reduced risk of BE, in our GWAS data (data not shown). At the IGF1R locus, 144 SNPs in the meta-analysis were nominally associated with risk of BE (P < 0.05), with 11 satisfying FDR q < 0.05. The most significant signals were clustered at the 5′ end of the locus (Figure 1B). Several of these intronic variants modify predicted sequence motifs for several transcription factors, including FOX, CTCF, Nf-kappaB, STAT and EWSR1-FL1 (Supplementary Table S6B). One SNP (rs4305005) exhibits particularly strong regulatory potential, and is located in a conserved region marked by DNAseI-hypersensitivity and enhancer histone modifications in multiple tissues including stomach, with FOXA2/p300 protein occupancy reported in a liver cancer cell line (HepG2). Five variants are GTEx eQTLs for IGF1R in non-esophageal tissues.

Figure 1.

LocusZoom plots for (A) GHR and (B) IGF1R SNPs in relation to BE risk (meta-analysis).

Assessment of gene–environment interactions and mediation relationships

We assessed associations of GHR SNPs and IGF1R SNPs with BE risk in subgroups stratified by individual BE/EAC risk factors, using BEACON GWAS data. No statistically significant interactions were noted for sex, smoking history (ever/never or categories of pack-years), BMI categories (normal, overweight, obese) or history of reflux, after FDR correction across all comparisons (data not shown). An interaction between one of the top IGF1R risk SNPs (rs1319869) and BMI, however, did satisfy FDR q < 0.1 when accounting for 131 IGF1R SNPs tested (P = 0.00067, FDR q = 0.088). We also evaluated effect modification by two measures of central obesity, WC and WHR, in subsets of participants with the relevant data. While nominally significant (P < 0.05) interactions were observed for certain GHR and IGF1R variants with WC/WHR, none remained significant after correction for multiple comparisons (Supplementary Tables S7 and S8).

To investigate obesity as a potential mediator in the association between IGF-related inherited variation and BE risk, we first examined IGF variants (n = 270) in relation to obesity status (BMI ≥30) among healthy controls in our study sample. Using logistic regression, we identified associations (P < 0.05) for 16 variants (1 GHR, 13 IGF1R, 1 IGFBP3 and 1 IGFBP6) (Supplementary Table S9A). Next, among the subset of participants with available BMI measurements, we assessed these 16 SNPs in relation to BE risk, with or without adjustment for BMI. Six of the 16 variants were associated with BE (P < 0.05) in the unadjusted analysis, and resulting ORs were highly similar after inclusion of BMI in logistic regression models (Supplementary Table S9B). At the pathway level, we further evaluated the extent to which obesity-associated variants might contribute to the observed risk association with BE, via a sensitivity analysis. After excluding the 16 obesity-associated SNPs from the pool of 270, we re-ran the pathway-level PCA test and found that the resulting likelihood ratio test P value (P = 0.0020) was only modestly attenuated compared with that reported in Table 2 (P = 0.0015). Together, these findings do not exclude a possible mediating role for obesity, but indicate that potential genetic influences on obesity alone are unlikely to account for the relationship between inherited variation in the core IGF axis and BE.

Discussion

Metabolic disturbances such as IGF axis dysfunction are hypothesized to be involved in obesity-related cancers (15,16,18). This study represents the first large consortium-based assessment of germline genetic variation in the IGF pathway and in its component genes with risks of BE and EAC. Through application of complementary statistical approaches, we identified both pathway-level and individual gene-level associations with risk of BE. First, using BEACON GWAS data, we observed a significant association between global variation in the IGF pathway and BE risk. This association remained significant after correcting for the previously examined five inflammatory pathways in our earlier analysis (13). Subsequent gene-level examination further resolved this pathway-level signal into gene-level associations for GHR and IGF1R. These gene-based associations with BE risk remained significant in an expanded GWAS meta-analysis dataset, with an additional signal for IGFBP3. At each locus, we further identified several non-coding risk-associated variants with regulatory potential.

The GHR gene, located on the short arm of chromosome 5, encodes the growth hormone receptor, a cell-surface receptor found abundantly in liver, muscle and adipose tissues, among others, in early embryonic life and after birth. The IGF1R gene, located on the long arm of chromosome 15, encodes the insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor, a cell-surface receptor highly expressed across many tissues (including the esophagus) (45). GHR is located upstream in the IGF pathway, while IGF1R is a downstream effector. GH, synthesized in the pituitary and released into circulation, binds to the extracellular region of GHR and triggers IGF1 production. Secreted IGF1 binds to binding proteins such as IGFBP3, which are cleaved off at target organ sites, eventually allowing free IGF1 to attach to IGF1R to stimulate cell proliferation via RAS-RAF-MAP kinase, and survival and cell cycle progression via PI3K/AKT and mTOR (46). Visceral adipose tissue releases pro-inflammatory and procoagulant adipocytokines, which can lead to IGF pathway dysfunction and insulin resistance, particularly where the volume of adipose tissue is increased, as in obesity (30). These changes may increase insulin secretion and reduce IGFBP levels, ultimately elevating free IGF1, which has been suggested to foster cell proliferation and contribute to carcinogenesis (18,30).

Since BE is an established precursor for EAC, factors that alter BE risk may change EAC predisposition. In this report, we found evidence that pathway-level and gene-level IGF-related genetic variation was significantly associated with risk of BE, but not with risk of EAC. There are multiple possible reasons for these findings. First, the sample size available for BE was ~30% larger than that for EAC, resulting in increased statistical power in the analysis of BE versus EAC. Of interest, we did find that EAC ORs obtained for multiple SNPs mapping to GHR and IGF1R were directionally concordant with (but smaller in magnitude than) ORs obtained in the BE analysis (Supplementary Table S5B). With a larger sample of EAC cases, more of these weak associations may have reached statistical significance. Second, BE is a heterogeneous condition with respect to its propensity to progress to EAC, likely reflecting a complex interplay between inherited genetics, somatic alterations and environmental exposures. If a BE susceptibility variant were associated with altered risk of indolent (but not aggressive) forms of BE, the overall risk estimate for EAC could be attenuated in magnitude relative to the risk estimate for BE. Third, past studies have also estimated that common variant heritability for BE () is larger than for EAC () (8), suggesting a more substantial overall role for inherited variation in the etiology of the precursor (BE) versus the cancer (EAC).

Visceral adiposity is a well-established risk factor for BE and EAC. It is noteworthy that IGF axis abnormalities are commonly observed in obese individuals, and those with metabolic syndrome (43,47,48), a condition recently linked to an elevated risk of BE (but not EAC) (49). If IGF-related genetic variation associated with BE risk results in subtle downstream functional alterations to this signaling axis, e.g. through changes in gene expression of cell-surface receptors, such risk could be modified by exposures which themselves interface biologically with the IGF system. While our present analysis did not reveal convincing evidence of gene–environment (G × E) interactions between adiposity measures and IGF-related variants, more complete ascertainment of WC/WHR is required in larger sample sizes to reach firmer conclusions. While our study does not exclude possible genetic influences on obesity by variants in the IGF pathway, such effects appear unlikely alone to account for the observed relationship between inherited variation in the IGF axis and BE risk. Identification and characterization of G × E interactions, coupled with assessment of the relationships between BE risk SNPs and environmental factors, can provide further insight into potential causal pathways which integrate genetic and non-genetic inputs. It may also be of interest to investigate interactions between IGF-related genetic variation and additional relevant exposures such as nutritional intake and physical activity, as well as studies of the degree to which gastroesophageal reflux conveys the increased obesity risk for BE.

Few studies have examined genetic variation in the IGF axis in relation to BE/EAC susceptibility. A case–control study of 102 SNPs in and around seven IGF-related genes—IGF1, IGF2, IGF1R, IGFBP3, GH1, GH2 and GHR—using a sample of ~500 BE/EAC cases and ~250 controls (32), found one GHR variant (rs6898743) associated with reduced risk of EAC, and one IGF1 variant (rs6214) associated with reduced risk of BE (32). Gene-level and pathway-level analyses were not performed. In our larger GWAS meta-analysis dataset, neither rs6898743 nor rs6214 was associated with BE or EAC risk (P > 0.2). In another case–control study of 431 participants, obese individuals with the polymorphic A-variant at G1013A in IGF1R were found to have increased risk of BE and EAC (50). In our GWAS meta-analysis data, this variant (rs2229765) was not associated (P > 0.2) with either BE or EAC.

IGF axis gene variants have been associated with risks of several other cancers including lung, breast, colorectal, prostate and ovary (21–24). Most notably, a lung cancer GWAS reported 11 risk-associated SNPs in genes encoding components of the GH–IGF pathway, including GHR (rs6183, minor allele frequency = 0.001, OR = 12.98, P = 0.0019) (51). Candidate gene studies in the past have also described associations between polymorphisms in IGF component genes such as IGF1R, IGF1 and IGFBP-3 and risks of breast, prostate and colorectal cancers (52–54). Of interest, mutations in GHR observed in Laron syndrome, leading to GH insensitivity and IGF1 deficiency, have been linked to reduced risks of various cancers (55).

The present study has several strengths. First, our analysis made use of the largest BE/EAC GWAS dataset currently available, providing a sample size ~20-fold higher than that used in previous studies, and thus greater power to detect genetic associations. Second, we employed two complementary statistical methods, PCA and MAGMA, to aggregate signals from multiple variants at the gene and pathway levels and determine joint relationships with BE/EAC risk. In reducing data dimensionality and the number of required statistical comparisons, these methods boost power and help focus association evaluation on blocks of the genome with suspected biological relevance to the disease of interest. Both approaches yielded GHR as the top gene-level signal. MAGMA, which can be applied to SNP summary statistics, enabled us to leverage summary data from a recent GWAS meta-analysis and extend our gene-level evaluation to a considerably larger study sample, yielding similar findings.

This study also has certain limitations. First, given the overlap in study participants between the GWAS meta-analysis and the BEACON GWAS, gene-level associations reported here will require formal validation using additional independent datasets. Second, the assessment of gene–environment interactions was limited by a substantial amount of missing or unavailable data for pertinent risk factors such as history of reflux, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use and obesity, which reduced statistical power and interpretability. Since visceral obesity, in particular, appears linked to risk of BE and EAC, WC/WHR represent the optimal measures for evaluating interactions, rather than BMI, but were only available for small subsets of BEACON participants. Third, in focusing on common genetic polymorphisms in and around 12 core genes in the IGF pathway, our analysis did not account for rare variants or variation within distal regulatory elements relevant to IGF axis function. Fourth, while there is some correlative evidence that GHR and IGF1R variants may influence mRNA expression levels, experimental studies will be needed in the future to establish projected causal linkages between such variants and altered gene expression.

In conclusion, using complementary approaches and large well-annotated GWAS datasets, we report novel associations between genetic variation in GHR and IGF1R and risk of BE, while no associations with EAC were revealed. Additional studies are required to validate these findings in even larger, more diverse cohorts; comprehensively investigate gene–environment interactions; and determine whether, and to what extent, genetic modulation of IGF pathway component gene expression may contribute to the etiology of BE.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Drs Rebecca Fitzgerald, Paul D. Pharoah and Carlos Caldas from the Oesophageal Cancer Clinical and Molecular Stratification (OCCAMS) Consortium for provision of data toward this project. We also thank Terri Watson, Tricia Christopherson and Paul Hansen for their contributions in project management and organization of biospecimens/data. Genotyping data generated in the BEACON GWAS has been deposited into dbGaP under accession number phs000869.v1.p1. The MD Anderson controls were drawn from dbGaP (study accession: phs000187.v1.p1). Genotyping of these controls was performed through the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center (UTMDACC) and the Johns Hopkins University Center for Inherited Disease Research (CIDR). We acknowledge the principal investigators of this study: Christopher Amos, Qingyi Wei and Jeffrey E. Lee. Controls from the Genome-Wide Association Study of Parkinson Disease were obtained from dbGaP (study accession: phs000196.v2.p1). This work, in part, used data from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) dbGaP database from the CIDR:NeuroGenetics Research Consortium Parkinson’s disease study. We acknowledge the principal investigators and coinvestigators of this study: Haydeh Payami, John Nutt, Cyrus Zabetian, Stewart Factor, Eric Molho and Donald Higgins. Controls from the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) were drawn from dbGaP (study accession: phs000524.v1.p1). The CRIC study was performed by the CRIC investigators and supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK). Data and samples from CRIC reported here were supplied by NIDDK Central Repositories. This report was not prepared in collaboration with investigators of the CRIC study and does not necessarily reflect the opinions or views of the CRIC study, the NIDDK Central Repositories or the NIDDK. We acknowledge the principal investigators and the project officer of this study: Harold I. Feldman, Raymond R. Townsend, Lawrence J. Appel, Mahboob Rahman, Akinlolu Ojo, James P. Lash, Jiang He, Alan S. Go and John W. Kusek.

Funding

This work was principally supported by the National Institutes of Health (R21DK099804 to M.M.M.; R01CA136725 to T.L.V. and D.C.W.; P30CA016056 to the Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center). Support for studies related to the Bonn dataset was granted by the Else Kröner Fresenius Stiftung (EKFS) (grant number 2013_A118 awarded to I.G. and J.S.). M.M.N. received support from the Alfried Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach-Stiftung and is a member of the DFG funded Excellence Cluster ImmunoSensation. The Heinz Nixdorf Recall cohort was established with the generous support of the Heinz Nixdorf Foundation, Germany. Additional funding sources for individual studies included in the BEACON GWAS, and for BEACON investigators, have been acknowledged previously. Study sponsors played no role in the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, or in the writing of the report.

Conflict of Interest Statement: None declared.

Author contributions

Conception and design: M.F.B., L.J.H. and S.G.D. Participant recruitment: T.L.V., L.J.H., D.C.W., J.S., J.J., I.T., W.Y., M.G., P.I., L.A., G.L., A.W., W-H.C., H.R., J.L., N.S., L.B., D.C., H.P., J.C., D.M., P.M., H.B., S.A., P.W., K.O., M.V., H.L., R.M., L.V., C.G., J.W., I.G., Y.V., M.M.N., J.R.I., H.M., H.N., T.R., A.H.H., M.A., O.P., B.S., C.S., T.S., D.L., M.V., A.M. and C.E. Data processing and extraction: P.G., S.M., L.O., D.M.L., C.P., S.L., L.C., R.H., S.M., M.K., A.C.B., T.N., T.H., N.K. and J.B. Analysis and interpretation of data: S.G.D., M.F.B., L.J.H., J.C., L.Y., Q.H., T.L.V. and M.M.M. Drafting of the manuscript: S.G.D. and M.F.B. Study supervision: M.F.B. All authors approved of the final draft submitted.

References

- 1. Coleman, H.G., et al. (2018) The epidemiology of esophageal adenocarcinoma. Gastroenterology, 154, 390–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Njei, B., et al. (2016) Trends in esophageal cancer survival in United States adults from 1973 to 2009: a SEER database analysis. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol., 31, 1141–1146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Smyth, E.C., et al. (2017) Oesophageal cancer. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers, 3, 17048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Vaughan, T.L., et al. (2015) Precision prevention of oesophageal adenocarcinoma. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol., 12, 243–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Peters, Y., et al. (2019) Barrett oesophagus. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers, 5, 35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Reid, B.J., et al. (2010) Barrett’s oesophagus and oesophageal adenocarcinoma: time for a new synthesis. Nat. Rev. Cancer, 10, 87–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Contino, G., et al. (2017) The evolving genomic landscape of Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma. Gastroenterology, 153, 657–673.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ek, W.E., et al. ; Mayo Clinic Esophageal Adenocarcinoma and Barrett’s Esophagus Registry Consortium; BEACON study investigators (2013) Germline genetic contributions to risk for esophageal adenocarcinoma, Barrett’s esophagus, and gastroesophageal reflux. J. Natl. Cancer Inst., 105, 1711–1718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gharahkhani, P., et al. ; Barrett’s and Esophageal Adenocarcinoma Consortium (BEACON); Esophageal Adenocarcinoma GenEtics Consortium (EAGLE); Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium 2 (WTCCC2) (2016) Genome-wide association studies in oesophageal adenocarcinoma and Barrett’s oesophagus: a large-scale meta-analysis. Lancet. Oncol., 17, 1363–1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Levine, D.M., et al. (2013) A genome-wide association study identifies new susceptibility loci for esophageal adenocarcinoma and Barrett’s esophagus. Nat. Genet., 45, 1487–1493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Palles, C., et al. (2015) Polymorphisms near TBX5 and GDF7 are associated with increased risk for Barrett’s esophagus. Gastroenterology, 148, 367–378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Su, Z., et al. ; Esophageal Adenocarcinoma Genetics Consortium; Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium 2 (2012) Common variants at the MHC locus and at chromosome 16q24.1 predispose to Barrett’s esophagus. Nat. Genet., 44, 1131–1136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Buas, M.F., et al. (2017) Germline variation in inflammation-related pathways and risk of Barrett’s oesophagus and oesophageal adenocarcinoma. Gut, 66, 1739–1747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Buas, M.F., et al. (2014) Integrative post-genome-wide association analysis of CDKN2A and TP53 SNPs and risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma. Carcinogenesis, 35, 2740–2747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Donohoe, C.L., et al. (2012) Role of the insulin-like growth factor 1 axis and visceral adiposity in oesophageal adenocarcinoma. Br. J. Surg., 99, 387–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Edelstein, Z.R., et al. (2007) Central adiposity and risk of Barrett’s esophagus. Gastroenterology, 133, 403–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kubo, A., et al. (2013) Sex-specific associations between body mass index, waist circumference and the risk of Barrett’s oesophagus: a pooled analysis from the international BEACON consortium. Gut, 62, 1684–1691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Long, E., et al. (2014) The role of obesity in oesophageal cancer development. Therap. Adv. Gastroenterol., 7, 247–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Steffen, A., et al. (2015) General and abdominal obesity and risk of esophageal and gastric adenocarcinoma in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition. Int. J. Cancer, 137, 646–657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fox, C.S., et al. (2007) Abdominal visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissue compartments: association with metabolic risk factors in the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation, 116, 39–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hankinson, S.E., et al. (1998) Circulating concentrations of insulin-like growth factor-I and risk of breast cancer. Lancet, 351, 1393–1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lukanova, A., et al. (2002) Circulating levels of insulin-like growth factor-I and risk of ovarian cancer. Int. J. Cancer, 101, 549–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Renehan, A.G., et al. (2004) Insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-I, IGF binding protein-3, and cancer risk: systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Lancet, 363, 1346–1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Roddam, A.W., et al. (2008) Insulin-like growth factors, their binding proteins, and prostate cancer risk: analysis of individual patient data from 12 prospective studies. Ann. Intern. Med., 149, 461–471, W83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Key, T.J., et al. (2010) Insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1), IGF binding protein 3 (IGFBP3), and breast cancer risk: pooled individual data analysis of 17 prospective studies. Lancet Oncol., 11, 530–542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Samani, A.A., et al. (2007) The role of the IGF system in cancer growth and metastasis: overview and recent insights. Endocr. Rev., 28, 20–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Iravani, S., et al. (2003) Modification of insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor, c-Src, and Bcl-XL protein expression during the progression of Barrett’s neoplasia. Hum. Pathol., 34, 975–982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network et al. (2017) Integrated genomic characterization of oesophageal carcinoma. Nature, 541, 169–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Di Martino, E., et al. (2006) IGFBP-3 and IGFBP-10 (CYR61) up-regulation during the development of Barrett’s oesophagus and associated oesophageal adenocarcinoma: potential biomarkers of disease risk. Biomarkers, 11, 547–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Doyle, S.L., et al. (2012) IGF-1 and its receptor in esophageal cancer: association with adenocarcinoma and visceral obesity. Am. J. Gastroenterol., 107, 196–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Siahpush, S.H., et al. (2007) Longitudinal study of insulin-like growth factor, insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3, and their polymorphisms: risk of neoplastic progression in Barrett’s esophagus. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev., 16, 2387–2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. McElholm, A.R., et al. ; Finbar Group (2010) A population-based study of IGF axis polymorphisms and the esophageal inflammation, metaplasia, adenocarcinoma sequence. Gastroenterology, 139, 204–212.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Delaneau, O., et al. (2011) A linear complexity phasing method for thousands of genomes. Nat. Methods, 9, 179–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. de Leeuw, C.A., et al. (2015) MAGMA: generalized gene-set analysis of GWAS data. PLoS Comput. Biol., 11, e1004219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. de Leeuw, C.A., et al. (2016) The statistical properties of gene-set analysis. Nat. Rev. Genet., 17, 353–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Benjamini, Y., et al. (2001) The control of the false discovery rate in multiple testing under dependency. Ann. Stat., 29, 1165–1188. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Auton, A., et al. (2015) A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature, 526, 68–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pruim, R.J., et al. (2010) LocusZoom: regional visualization of genome-wide association scan results. Bioinformatics, 26, 2336–2337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lonsdale, J., et al. (2013) The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project. Nat. Genet., 45, 580–585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ward, L.D., et al. (2012) HaploReg: a resource for exploring chromatin states, conservation, and regulatory motif alterations within sets of genetically linked variants. Nucleic Acids Res., 40, D930–D934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. World Health Organization (2008) Waist Circumference and Waist-Hip Ratio. Report of a WHO Expert Consultation. Geneva. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Pischon, T., et al. (2006) Body size and risk of colon and rectal cancer in the European Prospective Investigation Into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC). J. Natl. Cancer Inst., 98, 920–931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bowers, L.W., et al. (2015) The role of the insulin/IGF system in cancer: lessons learned from clinical trials and the energy balance-cancer link. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne), 6, 77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. GTEx Consortium (2015) The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) pilot analysis: multitissue gene regulation in humans. Science (New York, NY), 348, 648–660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Uhlén, M., et al. (2015) Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science, 347, 1260419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kashyap, M.K. (2015) Role of insulin-like growth factor-binding proteins in the pathophysiology and tumorigenesis of gastroesophageal cancers. Tumour Biol., 36, 8247–8257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Arcidiacono, B., et al. (2012) Insulin resistance and cancer risk: an overview of the pathogenetic mechanisms. Exp. Diabetes Res., 2012, 789174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lewitt, M.S., et al. (2014) The insulin-like growth factor system in obesity, insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes mellitus. J. Clin. Med., 3, 1561–1574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Drahos, J., et al. (2016) Metabolic syndrome in relation to Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma: results from a large population-based case-control study in the Clinical Practice Research Datalink. Cancer Epidemiol., 42, 9–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. MacDonald, K., et al. (2009) A polymorphic variant of the insulin-like growth factor type I receptor gene modifies risk of obesity for esophageal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol., 33, 37–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Rudd, M.F., et al. ; GELCAPS Consortium (2006) Variants in the GH-IGF axis confer susceptibility to lung cancer. Genome Res., 16, 693–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Cheng, I., et al. (2006) Common genetic variation in IGF1 and prostate cancer risk in the Multiethnic Cohort. J. Natl. Cancer Inst., 98, 123–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Zecevic, M., et al. (2006) IGF1 gene polymorphism and risk for hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst., 98, 139–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Canzian, F., et al. (2006) Polymorphisms of genes coding for insulin-like growth factor 1 and its major binding proteins, circulating levels of IGF-I and IGFBP-3 and breast cancer risk: results from the EPIC study. Br. J. Cancer, 94, 299–307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Laron, Z. (1999) The essential role of IGF-I: lessons from the long-term study and treatment of children and adults with Laron syndrome. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab., 84, 4397–4404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.