Abstract

Since 2009, a multidisciplinary team at Weill Cornell Medical College (WCMC) has collaborated to create a comprehensive, elective global health curriculum (GHC) for medical students. Increasing student interest sparked the development of this program, which has grown from ad hoc lectures and dispersed international electives into a comprehensive four-year elective pathway with over 100 hours of training, including three courses, two international experiences, a preceptorship with a clinician working with underserved populations in New York City, and regular lectures and seminars by visiting global health leaders. Student and administrative enthusiasm has been strong: In academic years 2009, 2010, and 2011, over half of the first-year students (173 of 311) participated in some aspect of the GHC, and 18% (55 of 311) completed all first-year program requirements.

The authors cite the student-driven nature of GHC as a major factor in its success and rapid growth. Also important was the foundation previously established by WCMC global health faculty, the serendipitous timing of the GHC’s development in the midst of curricular reform and review, as well as the presence of a full-time, nonclinical Global Health Fellow who served as a program coordinator. Given the enormous expansion of medical student interest in global health training throughout the United States and Canada over the past decade, the authors hope that medical schools developing similar programs will find the experience at Weill Cornell informative and helpful.

Interest in global health among medical students has soared. Between 1998 and 2008, medical schools in the United States and Canada experienced a 270% increase in the number of students participating in an international experience.1 In 2010, 47 (37.5%) of 128 U.S. and Canadian medical schools had a global health component in their curricula.2 Beyond their popularity, international electives offer numerous benefits: Students have the opportunity to learn cross-cultural sensitivity and communication skills, which allow them to better serve patients of varied cultural and socioeconomic backgrounds, develop improved physical examination skills, and are exposed to different health systems.3–8 Furthermore, participation in international electives has been associated with a future career working in primary care and/or with underserved populations.5,9

Despite efforts to incorporate global health training into medical education, 38.1% of U.S. medical graduates in 2011 felt that the time dedicated to global health issues at their medical schools was inadequate.10 A few years ago, this was the sentiment among students at Weill Cornell Medical College (WCMC), who had long benefited from international electives but voiced a desire for an increased breadth and depth of global health education to provide context to their international experiences.8 In response, a multidisciplinary team at Weill Cornell recently designed and launched a comprehensive, longitudinal, elective global health curriculum (GHC). The GHC course work, seminars, and both international and domestic experiential learning are designed to meet students’ expressed needs and help them to develop valuable skills for their future practices. As we hope to demonstrate in the rest of this article, the GHC is both innovative and unique.

Program Development: History, Goals, and Competencies

Opportunities for field learning and research abroad have been available to Weill Cornell medical students for more than 40 years. Over the decades, the scope and focus of the programs have expanded from the initial research and training sites in Haiti and Brazil to partnerships with medical schools and hospitals across six continents.11–14 These institutional partnerships have provided students the opportunity to travel throughout the world to engage in collaborative research, training and fieldwork. Today, between 30% and 40% of Weill Cornell students take electives abroad at some point during their time in medical school, usually with financial support from WCMC.

Prior to formation of the GHC, several student-led global health educational programs existed, including a noncredit malaria elective, a Careers in Global Health seminar series, and a Forum on Neglected Tropical Diseases. In 2008, the students behind these programs joined key faculty members from several departments, a medical resident, and a nonclinical Global Health Fellow to begin planning for a formalized, longitudinal, and sustainable global health education initiative. Key faculty came from the Office of Global Health Education (OGHE),15 the Center for Global Health (CGH),16 and the Global Emergency Medicine Program (GlobalEM).17

This initial working group met numerous times during the 2008–2009 academic year. These meetings were led by students and the Global Health Fellow (a recent college graduate hired to facilitate the initiation of global health infrastructure); participants included all of this article’s authors, except A.K. and A.S.M., as well as Cora Walsh, MD. We (the members of the working group) established goals, defined competencies, outlined and planned courses, defined future leadership structures, established outcome metrics, and discussed funding options. A draft version of the GHC was presented to various internal academic committees and stakeholders for informal review and feedback. Out of these working meetings, the GHC, as outlined below, was launched in the fall of 2009.

To identify the components that would best fit into our program, we reviewed syllabi and articles related to global health programs at other medical institutions,6,18–23 literature on global health education,4,24–28 and a global health education curricula development guide.29 In addition, the experience and perspectives of stakeholders—residents, fellows, students, and faculty—also contributed to the development of the GHC structure, focus, and mission.

We outlined two main goals for the GHC:

to provide a comprehensive overview of major thematic topics in global health through course-based and experiential learning, and

to provide a mentored pathway for engaging with resource-poor communities, both internationally and domestically.

We defined global health as service, training, and research that address health problems disproportionately affecting resource-poor communities.

Notably, the GHC includes underserved domestic populations within its definition of global health, encouraging a focus on health inequities that exist throughout the world. Indeed, the skills and knowledge gained in the GHC are meant to apply to students’ future work with a range of patient populations both in the United States and abroad. With regard to global health skills applicable domestically, the GHC enhances students’ preparation to care for local underserved and immigrant populations and to address the wider spectrum of disease facing the U.S. population brought about by globalization.

Finally, we identified five core competencies for the GHC, each with detailed teaching objectives. Topics already taught in the Weill Cornell curriculum (i.e., tropical medicine, epidemiology and biostatistics, and cultural diversity) were not emphasized in our list. The GHC core competencies are

Global Burden of Disease

Inequalities, Health, and Human Rights

Research and Evidence-Based Outcomes

Key Stakeholders in Global Health

Health Systems and Health Care Delivery

Overview of the GHC: The Academic Components

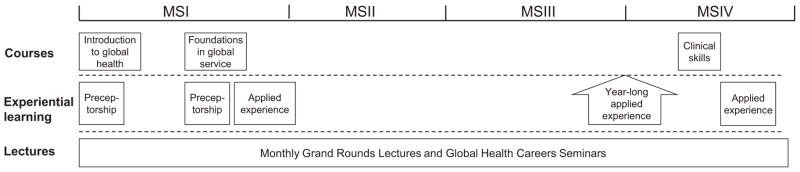

Presently, the GHC consists of over 100 hours of course work and seminars, including three formal courses, a clinical preceptorship with a resource-poor population in New York City, monthly Global Health Grand Round lectures and career seminars, and two field experiences known as “Applied Experiences” (see Figure 1 and Table 1). At this time, the GHC is an elective program designed to complement the traditional medical education curriculum. The majority of formal course work in the GHC is presented in the first and fourth years of medical school, with a focus on theory in the first year and on clinical skills in the fourth.

Figure 1.

Overview of the Global Health Curriculum (GHC) time line. The GHC is a comprehensive four-year elective pathway with over 100 hours of training, including three courses, two international experiences, a preceptorship with a clinician working with underserved populations in New York City, and regular lectures and seminars by visiting global health leaders. The optional, year-long Applied Experience (i.e., field experience) occurs between the student’s third and fourth years of medical school. (Note: students complete their global health preceptorship during one of the two outlined time blocks.)

Table 1.

Components of the Weill Cornell Global Health Curriculum (GHC) at Weill Cornell Medical College (WCMC)

| Component | Duration | Audience | Requirements and assessments for GHC enrollment | Concomitance of GHC and WCMC requirements for the MD degree | Student completion: years: numbers* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Courses | |||||

| Introduction to Global Health: A Case-Based Approach | 14 weeks, 28 hours | WCMC first-year students |

|

No credit toward MD degree |

|

| Foundations in Global Service | 5–7 weeks, 7.5 hours | WCMC first-year students |

|

No credit toward MD degree |

|

| Global Health: Clinical Skills for Resource-Poor Settings | 2 weeks, 80 hours | Any fourth-year students |

|

Elective credit toward MD degree |

|

| Experiential learning | |||||

| Global Health Preceptorship | 7 weeks, 28 hours | WCMC first-year students |

|

Credit for one first-year clinical preceptorship requirement for the MD degree |

|

| Applied Experiences (i.e., hands-on experiences in the field, office, and/or lab) | Full-time study/experience at least four weeks in length | WCMC first-, third-, and/or fourth-year students |

|

Elective credit toward MD degree awarded for fourth-year Applied Experiences only | |

| Lecture series and seminars | |||||

| Global Health Grand Rounds | 9 sessions, 1 hour per session |

|

|

No credit toward MD degree |

|

| Global Health Career Seminar | Variable per year, 1 hour per session | Students and medical residents |

|

No credit toward MD degree | NA |

The student completion column lists the number of students who have met the requirements for the specified GHC component by academic year of completion.

Students represented ten medical schools.

Twelve of the 32 were not enrolled in the GHC.

One of the 26 was not enrolled in the GHC.

Three of 21 were physician assistant students.

Eight of the 20 were not enrolled in the GHC.

To maintain enrollment in the GHC, students must meet the requirements for each program component, as outlined in Table 1. To encourage global health education among all Weill Cornell students, we also allow nonenrolled students to participate in any GHC component, space permitting. We hope to establish a means for formal recognition of program completion by the time the first GHC class graduates in 2013 (e.g., certificate of completion from the medical college, mention in the dean’s letter to residency programs).

Course work and didactics

Below is an overview of the topics covered in each course (see Table 1 for more details).

Introduction to Global Health (Fall, first year)

Weekly sessions incorporate lectures, readings, and case-based discussions to provide a theoretical background and exposure to major issues in global health. Topics include Global Burden of Disease, Social Determinants of Health, Health Systems, and Global Health Policy.

Foundations in Global Service (Spring, first year)

To prepare students for their first Applied Experience, weekly case-based discussions focus on logistical, situational, and ethical concerns associated with working in underserved communities. Sessions are student-led with a faculty facilitator.

Global Health: Clinical Skills for Resource-Poor Settings (Spring, fourth year)

Clinically focused, case-based lectures are followed by hands-on labs and workshops designed to reinforce concepts and develop skills pertaining to the delivery of care with limited resources across a range of clinical disciplines.30 This course is open to fourth-year students from across the United States.

Experiential learning

Experiential learning provides hands-on application of the presented course theory within domestic and international resource-poor environments.

The Global Health Clinical Preceptorship

This preceptorship allows first-year students to observe the complex challenges faced by low-income, HIV-positive, and/or immigrant populations in New York City, and build their communication and cross-cultural skills in the first year of medical school, before ever going abroad. As part of the required WCMC curriculum, all first-year students are assigned to a practicing physician with whom they shadow and learn history-taking skills. Students in the GHC are matched with physicians working with resource-poor populations.

Applied Experiences

Applied Experiences (AEs) are the cornerstone of the GHC. The two required AEs may be completed within domestic or international resource-poor settings and can take on a range of scopes (e.g., community health, clinical, policy, research). AEs are typically completed during the summer following the first year and during the fourth. Some students elect to complete a year-long AE between the third and fourth years of medical school.

Lectures and seminars

Global Health Grand Rounds

This is a monthly lecture series, open to the public, which brings global health leaders to WCMC to speak about their work. Students select and invite the speakers.

Global Health Career Seminars

These seminars, held after the Global Health Grand Rounds lectures, are informal discussions with the lecturers and are overseen by students. Both the Global Health Grand Rounds and the Global Health Career Seminars are open to WCMC students for all four years; however, attendance to the grand rounds in the first year of medical school is required toward completion of the GHC.

Student assessment

Students are required to provide a written summary of their AE projects and to complete clinical case assessments at the end of the Clinical Skills course. These assessments encourage self-reflection and put into practice knowledge acquired during the course. At present, there are no formal assessments for other courses, but students must meet an attendance requirement in order to receive credit for program completion (see Table 1). Students are also required to complete feedback surveys (see “Student Feedback” below). Beginning in the 2011–2012 academic year, a final project was required for each curricular component; this may include developing or working through a case study, writing a reflection paper, or identifying additional resources to be used during course sessions.

Governance and Funding of the GHC

A unique aspect of the GHC is the strong role played by students in overseeing the program. As mentioned earlier, a core group of four students and a Global Health Fellow initiated the design of the GHC, with the support, feedback, and guidance of faculty and a medical resident. At present, the GHC is overseen by a steering committee of nine students (with representatives from each medical school class), six faculty members, two Global Health Fellows, and two medical residents. The medical residents provide a young professional’s perspective on the changing field of global health, particularly pertaining to residency and career opportunities for students. Student-chaired, faculty-mentored subcommittees plan, direct, and evaluate each programmatic component of the GHC and report back to the steering committee. This process ensures that the program remains dynamic, relevant, and constantly evolving based on student feedback. Currently, over 30 students are actively involved in the development and administration of the GHC.

Critical to the success of the GHC are the two full-time Global Health Fellows who serve as the course coordinators, program overseers, and student-faculty liaisons. In addition, summer interns are recruited on an as-needed basis to work on program development projects.

Until 2011, the GHC was implemented on a modest budget, covered by informal cost sharing between the three offices that are stakeholders in the program (CGH, OGHE, and GlobalEM) as well as internal offices and student groups. At the start of the GHC’s third academic year in 2011, these three stakeholders created a formalized annual operating budget to propel program development, with each group contributing their share to cover program costs totaling $10,000 per year. The Global Health Fellow salaries, currently the largest expense, are funded through a temporary grant from the Office of the Dean and the OGHE. Additionally, several internal offices, student groups, and a one-time external grant have supported various aspects of the curriculum including room reservations, personnel workspace, and technology support.

The GHC’s Successes to Date

Since its inception, the GHC has had a number of successes, brought about through strong student interest in the program and verified by positive reviews by students, faculty and members of the administration.

Enrollment

In the first year of the GHC (2009–2010), 19% (20 of 105) of the first-year students met all enrollment requirements, with 53% (56 of 105) participating in some aspect of the program. In the program’s second year (2010–2011), 16% (17 of 103) met all requirements, with 59% (61 of 103) taking part in some aspect. In the program’s third year, 17% (18 of 103) met all requirements, with 54% (56 of 103) taking part in some aspect. This level of participation far exceeded our expectations and demonstrates strong student interest and enthusiasm.

Student feedback surveys

Student feedback has offered valuable perspectives on how the program is received and suggestions for improvement. Feedback surveys are administered after each course session and Grand Rounds lecture, with comprehensive perspective surveys given at critical junctures during the program. Survey results are used to improve the curriculum in many ways, including modification of course schedules, assigned readings, lecture materials, speakers, and student assessment methods, as well as changes to the overall program structure. Overall, feedback has been very positive in response to the program, although some students desired an increased level of rigor to the courses and for structured mentorship throughout the AEs (see “Future Directions of the GHC” below).

Weill Cornell administrative feedback

The GHC has been received positively by various WCMC academic and administrative committees, including the Board of Overseers and Council of Affiliated Deans. Most recently, the WCMC Education Unit, formed by the dean with the objective of revising the medical school curriculum, cited the GHC as a model for emphasizing “student individualization” in the reformed curriculum. In addition, the GHC was listed, by WCMC administrators, as one of WCMC’s “highlights” in a recent curriculum audit,31 and as an institutional strength by the Liaison Committee on Medical Education in their 2010 site report. Further, the dean’s office continues to financially support the GHC.

Future Directions for the GHC

Long-term GHC program assessment

Starting in 2013, the success of the GHC will be measured by analysis of its impact on students’ career and professional choices. Program assessment will look at residency and specialty choices, alumni involvement in global health, and self-reported influence of the program on choices and charitable support. Tracking mechanisms, which will include an exit survey of each graduating class beginning with the Class of 2013, will also strengthen the GHC alumni network and enhance opportunities and resources available for future GHC students (e.g., increased opportunities for mentors, project variety).

Connecting the global Cornell community

Plans are under way to enhance connections and share global health educational resources between students at Cornell-affiliated campuses, including WCMC, Cornell University in Ithaca, Weill Bugando University College of Health Sciences in Tanzania, Weill Cornell Medical College in Qatar, and GHESKIO, the Weill Cornell affiliate clinic in Haiti.

Further developing the educational program

The GHC continues to expand options for AEs both domestically and abroad. There are also hopes to develop additional pathways to accommodate students who come to WCMC with no global health background as well as those with extensive experience. More advanced pathways might include a supported year-off intensive research experience at one of the GHC partner sites. As the GHC continues to formalize, those of us who are responsible for it are also looking for ways to better integrate the program into the existing medical curriculum. Steps towards these efforts include finding a faculty program director, determining long-term funding sources for the GHC, and offering elective credit for all components completed.

Creating a global health faculty and projects database

We are currently developing a comprehensive database of past and current global health projects completed by students and residents, or offered by faculty at WCMC, Cornell University in Ithaca, and Cornell-affiliated sites. This database will be a starting point for students wishing to identify potential field experiences while also bridging the global health work and interests of Cornell community members.

Challenges Faced

Development of the GHC has been an innovative experiment in collaborative curriculum development between students, residents and multiple faculty stakeholders. The current success of the program has been achieved through trial and error, careful design, and overcoming obstacles, some of which are elaborated herein.

Funding

Securing funding has been a consistent challenge. As the GHC became more established, we were able to secure increased funding from the WCMC administration and our major stakeholder offices (CGH, OGHE, and GlobalEM). However, we hope to determine more permanent sources to support GHC administrative and curricular costs.

Breadth versus depth

In designing the didactic course work for the GHC, we struggled with tension between providing a broad overview of key global health subjects and teaching less material in a more substantive way. GHC course work is not intended to be a replacement for experience abroad or for comprehensive programs of study such as a masters in public health. Our hope is that the didactic curriculum will expose students to a broad array of issues that they may not otherwise formally encounter, and help them to identify areas of interest to pursue in greater depth in AEs and beyond.

Continuity

Given the heavy student involvement in the GHC and the transitory nature of educational programs, it is important to continuously involve new students and residents in the governance of the GHC. Each year, motivated students from the first year and physician assistant classes are recruited to serve on subcommittees within the GHC, ensuring that students retain a significant voice within the GHC as the program becomes more institutionalized. We feel this is essential for the program to continue to remain relevant and useful for students. In addition, two Global Health Fellows are now members of the GHC staff, each with two-year positions that overlap by one year, to ensure administrative continuity. However, in the future, this short tenure may become a limitation and a more long-term position may be considered.

Integration into the medical school curriculum

The GHC broke new ground as the first extracurricular elective program of its nature at Weill Cornell. Elective opportunities during the first and second years had not traditionally been offered, out of concern for demands on students’ limited time. With this in mind, we have worked to find a balance to providing a rigorous educational experience without overburdening students.

The Ongoing Importance of the GHC

The GHC is an example of a grassroots student initiative that, with faculty mentorship and administrative support, has yielded a formal, robust global health program. Students learn topics and skills relevant to work in resource-poor settings, which usually are not emphasized in general clinical training. Additionally, the GHC course work and seminars build a global health community among students and faculty, providing students an avenue for discussion of relevant topics, as well as opportunities to learn from and network with clinicians and researchers engaged in a range of global health projects.

The origins of our program and its student-led structure are unique aspects of the GHC. The program is sustained and constantly refined by motivated and enthusiastic students, faculty, and staff. As the GHC further develops and formalizes, students will continue to have a prominent role in the program’s vision and execution in order to maintain its unique and dynamic nature. We hope that this student-driven model will serve to guide and encourage students and faculty at other medical schools who wish to establish and enhance global health education in their institutions.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank all members of the Global Health Curriculum Working Group and Committees. The GHC would not have been possible without the dedicated voluntary work of the faculty, residents and students involved in the program’s establishment. Particularly, the authors would like to thank Cora Walsh, who was integral in drafting and establishing the GHC. The authors would also like to thank the following who have worked on developing specific components of the GHC after it was piloted in 2009: Rachelle Tomei, Naomi Shike, Elan Guterman, Rula Gladden, Taryn Clark, Erin Byrt, Eva Amenta, Ryan Gallagher, Daniel Shapiro, Ellie Emery, Daniel Hegg, and Carrie Bronsther. The authors also wish to especially acknowledge the gracious support and financial commitment of all the supporters mentioned in the “other disclosures” section below.

Funding/Support: None.

Footnotes

Other disclosures: Funding and support for the Weill Cornell Medical College (WCMC) Global Health Curriculum was provided by The WCMC Office of Global Health Education, the Global Emergency Medicine Program at Weill Cornell Medical College/NewYork–Presbyterian Hospital, the WCMC Center for Global Health, the WCMC Office of the Dean, the WCMC Office of the Secretary, the WCMC Office of Academic Affairs, the WCMC Events Management Office, the WCMC Information Technology Office, and the WCMC Medical Student Executive Committee. Ms. Francis and Ms. Kulkarni are supported by the WCMC Office of Global Health Education and Office of the Dean. Ms. Goodsmith, Ms. McKenney, and Dr. Kishore are supported by Medical Science Training Program grant GM07739 to the Weill Cornell/RU/MSKCC Tri- Institutional MD-PhD Program.

Ethical approval: Not applicable.

Previous presentations: Ms. Kulkarni, Ms. Francis, Dr. Fein, and Dr. Finkel presented a short communication submission about the GHC at the NEGEA 2011 Annual Retreat, December 31, 2010, Washington, DC.

Contributor Information

Ms. Elizabeth R. Francis, Senior global health fellow, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, New York, when this article was written. She is now a student, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, Maryland, and Pennsylvania State University School of Medicine, Hershey, Pennsylvania.

Ms. Nichole Goodsmith, Student, Weill Cornell/Rockefeller/Sloan-Kettering Tri-Institutional MD-PhD Program, New York, New York

Dr. Marilyn Michelow, Student, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, New York, when the article was written. She is now a resident in internal medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts.

Ms. Amita Kulkarni, Junior global health fellow, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, New York, when the article was written. She is now presidential fellow in global health, Dartmouth Center for Health Care Delivery Science, Hanover, New Hampshire

Ms. Anna Sophia McKenney, Student, Weill Cornell/Rockefeller/Sloan-Kettering Tri-Institutional MD-PhD Program, New York, New York.

Dr. Sandeep P. Kishore, Student, Weill Cornell/Rockefeller/Sloan-Kettering Tri-Institutional MD-PhD Program, New York, New York.

Dr. Nathan Bertelsen, Resident in internal medicine, Weill Cornell Medical College and NewYork–Presbyterian Hospital, when this article was written. He is now assistant professor of medicine, Bellevue Hospital Center/New York University School of Medicine, and associate medical director, Bellevue/NYU Program for Survivors of Torture, New York, New York.

Dr. Oliver Fein, Associate dean (affiliations) and professor of clinical medicine and public health, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, New York.

Dr. Satchit Balsari, Director, Global Emergency Medicine Program, and assistant professor, emergency medicine, Weill Cornell Medical College, and attending physician, NewYork–Presbyterian Hospital, New York, New York.

Dr. Jay Lemery, Director of wilderness and environmental medicine and assistant professor of emergency medicine, Weill Cornell Medical College, and attending physician, NewYork–Presbyterian Hospital, New York, New York.

Dr. Daniel Fitzgerald, Codirector, Center for Global Health, and associate professor of medicine, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, New York.

Dr. Warren Johnson, B.H. Kean Professor of Tropical Medicine and director, Center for Global Health, Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, New York.

Dr. Madelon L. Finkel, Director, Office of Global Health Education, and professor, Department of Public Health, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, New York.

References

- 1.Brewer TF, Saba N, Clair V. From boutique to basic: A call for standardised medical education in global health. Med Educ. 2009;43:930–933. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03458.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson BM, Kanter SL. Medical education in the United States and Canada, 2010. Acad Med. 2010;85(9 suppl):S2–S18. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181f16f52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ackerly DC, Udayakumar K, Taber R, Merson MH, Dzau VJ. Perspective: Global medicine: Opportunities and challenges for academic health science systems. Acad Med. 2011;86:1093–1099. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318226b455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mutchnick IS, Moyer CA, Stern DT. Expanding the boundaries of medical education: Evidence for cross-cultural exchanges. Acad Med. 2003;78(10 suppl):S1–S5. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200310001-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thompson MJ, Huntington MK, Hunt DD, Pinsky LE, Brodie JJ. Educational effects of international health electives on U.S. and Canadian medical students and residents: A literature review. Acad Med. 2003;78:342–347. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200303000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith JK, Weaver DB. Capturing medical students’ idealism. Ann Fam Med. 2006;4(suppl 1):S32–S37. doi: 10.1370/afm.543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haq C, Rothenberg D, Gjerde C, et al. New world views: Preparing physicians in training for global health work. Fam Med. 2000;32:566–572. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drain PK, Primack A, Hunt DD, Fawzi WW, Holmes KK, Gardner P. Global health in medical education: A call for more training and opportunities. Acad Med. 2007;82:226–230. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3180305cf9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ramsey AH, Cynthia H, Craig G, Debra R. Career influence of an international experience during medical school. Fam Med. 2004 Jun;:412–416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Association of American Medical Colleges. GQ Program Evaluation Survey. All Schools Summary Report Final. Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson WD., Jr The Cornell–Bahia program, 1964–1975: An experience in international training. J Med Educ. 1980;55:675–682. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198008000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pape JW, Liautaud B, Thomas F, et al. Characteristics of the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) in Haiti. N Engl J Med. 1983;309:945–950. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198310203091603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peck R, Fitzgerald DW, Liautaud B, et al. The feasibility, demand, and effect of integrating primary care services with HIV voluntary counseling and testing: Evaluation of a 15-year experience in Haiti, 1985–2000. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;33:470–475. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200308010-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hau D, DiPace JI, Peck RN, Johnson WD., Jr Global health training during residency: The Weill Cornell Tanzania experience. J Grad Med Educ. 2011;3:421–424. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-10-00204.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Office of Global Health Education Weill Cornell Medical College. [Accessed May 31, 2012]; http://med.cornell.edu/international.

- 16.Center for Global Health. Weill Cornell Medical College. [Accessed May 31, 2012]; http://med.cornell.edu/globalhealth.

- 17.Global Emergency Medicine Program. Weill Cornell Medical College/NewYork–Presbyterian Hospital; [Accessed May 31, 2012]. http://www.globalemergencymedicine.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 18.Quinn TC. The Johns Hopkins Center for Global Health: Transcending borders for world health. Acad Med. 2008;83:134–142. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318160b101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. [Accessed June 1, 2012];American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene Web site. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.17-medals. http://www.astmh.org/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Stapleton FB, Wahl PW, Norris TE, Ramsey PG. Addressing global health through the marriage of public health and medicine: Developing the University of Washington department of global health. Acad Med. 2006;81:897–901. doi: 10.1097/01.ACM.0000238115.41885.c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Macfarlane SB, Agabian N, Novotny TE, Rutherford GW, Stewart CC, Debas HT. Think globally, act locally, and collaborate internationally: Global health sciences at the University of California, San Francisco. Acad Med. 2008;83:173–179. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31816096e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haq C, Baumann L, Olsen CW, et al. Creating a center for global health at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. Acad Med. 2008;83:148–153. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318160af6b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pust RE, Moher SP. A core curriculum for international health: Evaluating ten years’ experience at the University of Arizona. Acad Med. 1992;67:90–94. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199202000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jacobsen KH. Introduction to Global Health. Sudbury, Mass: Jones and Bartlett Publishers; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koop EK, Pearson CE, Schwarz RM. Critical Issues in Global Health. San Francisco, Calif: Jossey-Bass; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koehn PH, Swick HM. Medical education for a changing world: Moving beyond cultural competence into transnational competence. Acad Med. 2006;81:548–556. doi: 10.1097/01.ACM.0000225217.15207.d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Houpt ER, Pearson RD, Hall TL. Three domains of competency in global health education: Recommendations for all medical students. Acad Med. 2007;82:222–225. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3180305c10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heck JE, Wedemeyer D. A survey of American medical schools to assess their preparation of students for overseas practice. Acad Med. 1991;66:78–81. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199102000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Evert J, Mautner D, Hoffman I. Developing Global Health Curricula: A Guidebook for US Medical Schools. San Francisco, Calif: Global Health Education Consortium; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lemery J, Sacco D, Kulkarni A, Francis L. Wilderness medicine with global health: A strategy for less risk and more reward. Wilderness Environ Med. 2012;23:84–88. doi: 10.1016/j.wem.2011.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Storey-Johnson C, Marzuk PM. Weill Cornell Medical College of Cornell University. Acad Med. 2010;85(9 suppl):S412–S417. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181ea29b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]