Abstract

What role do students have in global health activities? On one hand, students have much to offer, including innovative ideas, fresh knowledge and perspective, and inspiring energy. At the same time, students lack technical credentials and may drain resources from host communities. Here, we examine the dynamic, contemporary roles of students in global health activities, including health delivery. We focus on 3 themes that guide engagement: (1) fostering an enabling policy environment (eg, toward greater health equity); (2) understanding and working within the local context and governments’ needs; and (3) leading bidirectional partnerships. We next study the implications of short-term exposure and long-term engagement programs. We conclude with 4 recommendations on how to better equip students to engage in the next frontier of global health education and future action.

Risk more than others think is safe,

Care more than others think is wise,

Dream more than others think is practical,

Expect more than others think is possible.

–Claude Bissell

These words were posted on Facebook by the late Sujal Parikh, a fourth-year University of Michigan medical student in the midst of a 1-year Fogarty fellowship with the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in Kampala, Uganda. He was studying human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune deficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) at the prestigious Joint Clinical Research Institute under the supervision of Dr. Peter Mugyenyi. Parikh was active with the Uganda Village Project, focused on the provision of community health and education in rural Uganda. He worked to secure latex gloves for Makerere University medical students and formed novel North-South exchange programs involving students, young doctors, and researchers in East Africa. He was on the advisory board for the Center for Global Health at the University of Michigan. On October 12, 2010, Parikh died as a result of injuries sustained in a road traffic accident in Uganda.1,2 Parikh's vision and his passionate immersion in all matters related to global health, exemplified by the Bissell quote he posted, typify students’ emotive connection to global health.

CONCEPTUALIZING STUDENT ENGAGEMENT IN GLOBAL HEALTH

Written by a constellation of students and junior faculty at US universities, this article examines the role of students in global health activities. Students are increasingly faced with opportunities in global health, and we argue that students have much to offer, despite not having the technical credentials required for practice. Fundamentally, we strongly believe that the scope of global health activities extends beyond health professionals (or health professionals-in-training) alone, and that collaboration across disciplines and national boundaries should be the modus operandi in global health going forward. Drawing from several illustrative case studies of student-led initiatives in global health, we describe 3 key thematic areas where student engagement has been highly impactful in global health: (1) fostering an enabling policy environments (eg, toward greater health equity); (2) understanding and working within the local context and governments’ needs; and (3) leading bidirectional partnerships. We address each in turn below (Figure 1).

Fig 1.

Student engagement and education in global health delivery and implementation.

Fostering an Enabling Policy Environment Toward Health Equity

One concrete domain where students who are not licensed or able to practice in the field have managed to change paradigms has been in the policy arena. Driven by a combination of passionately held values, unwavering determination, and astute dedication, students have been able to influence policy interventions that have made extensive impacts, as illustrated in the following case examples.

Access to HIV Antiretrovirals

In 2001, the cost of d4t (Stavudine), an antiretroviral medicine, was >$1500 per patient per year. Realizing that this prohibitive cost precluded access to the drug for many patients around the world, Yale Law School student Amy Kapczynski studied the technology transfer agreements detailing Bristol-Myers Squibb's exclusive license with the university as the sole manufacturer of this medicine. Equipped with an understanding of intellectual property licensing agreements between universities and pharmaceutical firms, Kapczynski led a student movement to lobby for generic manufacturing of the antiretroviral d4T by a South African generic pharmaceutical firm. Her efforts resulted in a 97% price drop and the first instance of a pharmaceutical firm voluntarily authorizing production of a licensed medicine by a generic manufacturer.3,4

The impact of the movement, in South Africa in particular, is described by Eric Goemaere of Médecins Sans Frontières:

Today, 12,000 patients are on ARVs (antiretrovirals) in Khayelitsha and an estimated 800,000 nationwide, [constituting the] biggest ART (antiretroviral therapy) program in the world: this is in great deal thanks to a few courageous and idealistic Yale students who managed to dig a first small hole in the IP (intellectual property) fortress. No one in that time could have imagined it would make the fortress collapse, change public opinion, and have such consequences on the survival of millions of people.

A wave of similar covenants followed. By 2010, >35 institutions had signed on to a statement supporting the use of such a license, including government health institutions (eg, the NIH and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC]).5,6 The movement by Kapczynski led to the formation of the organization Universities Allied for Essential Medicines, with >50 North American chapters and chapters across the world. Alumni of this movement now work at Médecins Sans Frontières, the William J. Clinton Foundation, and the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy on areas related to improving access to essential medicines. This movement, though initially driven by law students, has now included medical, business, science, and undergraduate students, which further underscores the importance of cross-disciplinary approaches.

Real-World Translational Trials

There is value in translational, real-world trials that evaluate population-wide policy, public health, and social and economic interventions–and not just medicines alone. The most commonly recognized examples of knowledge translation involve taking pharmaceuticals from “bench to bedside” or getting “drugs to market.” And despite the fact that the greatest advances in prolonging life expectancy were related to system- and societal-level interventions, these are infrequently held with the same regard–and even less frequently funded.

Community Interventions for Health is an example of a real-world “trial,” which was essentially brought to fruition by Yale University graduate students and faculty who hosted a conference to discuss the feasibility of implementing and simultaneously evaluating parallel community-based health interventions in >20 countries across the world. Despite the challenges of acquiring funds to support the high costs of a 15-country study, a graduate student named Kathleen O'Connor Duffany persisted and amassed $5 million in funding. As a result, Community Interventions for Health is now being implemented globally in a combination of developed and developing countries. The action-oriented intervention program includes a comprehensive evaluation component, including environmental scans to identify opportunities for and barriers to health in communities, schools, workplaces, and health centers involved in the project.

Understanding Local Context and Governments’ Needs

It is important to galvanize and empower communities to provide a durable path of development, keeping in mind the needs of the community and the country at large. In other words, the approach should be highly specialized to the culture and environment of the community at hand. Adopting policies that have been vertically handed down, or have been proven to work elsewhere, is less likely to work.

Local Context

Following Liberia's civil conflict, a University of North Carolina medical student, Rajesh Panjabi, began working in Zwedru, where he met Weafus Quitoe, a Liberian war refugee of the same age who was volunteering as a nurse aide. The hospital where Quitoe worked saw 9% of all pregnant women infected with HIV. By 2007, Panjabi and Quitoe worked with the Ministry of Health to establish an community health worker (or “accompanier”) program to fill massive workforce shortages and deliver essential medicines into rural Liberia. In 2007, they helped established the HIV Equity Initiative, Liberia's first rural public HIV prevention and treatment programs worldwide (providing care for >300 HIV/AIDS patients). This model led to the formation of Tiyatien Health, a civil society organization that is partnering with the Liberian government to reconstruct rural healthcare. Tiyatien Health has developed and implemented a community-based model of HIV care delivery that has dramatically improved survival and is now being adopted nationally and to tackle noncommunicable diseases, including depression and epilepsy. Tiyatien Health also partnered with Harvard University and others to conduct the first national prevalence study of mental health disorders among Liberia's former armed forces and war victims, finding 40% are affected by post-traumatic stress disorder and depression, which has led to the drafting of Liberia's first mental health policy.7

Locally Relevant Innovations

While a doctoral student in genetics at Harvard, Nina Dudnik noticed that the laboratory hallways were full of old but usable lab equipment, left there by researchers. Realizing that this equipment could benefit less-fortunate researchers in other parts of the world, Dudnik began to collect unwanted equipment from a few labs and sent the first shipment to labs in Paraguay and Guatemala. Soon, students all across the university were helping to reclaim surplus lab equipment to enable scientific research in low- and middle-income countries, which led to the formation of Seeding Labs (http://www.seedinglabs.org). Further, to address the sense of isolation that many scientists feel, Dudnik established a network to connect these scientists to one another through Seeding Labs. As a result of Seeding Labs’ facilitation, laboratories in 16 countries throughout Latin America, the Caribbean, Africa, and Asia have been linked with those in the United States to share skills, resources, and training, as well as to cultivate the talent pool and strengthen the young, emerging scientific community. Dudnik has since been recognized as a TED Global 2010 fellow.

Leading Bidirectional Partnerships

Bidirectional partnerships, facilitated by modern Web tools, constitute important steps toward aligning local needs with available resources and capital. Moreover, partnerships extend beyond direct delivery of treatments to include capacity-building for systems, processes, and student empowerment, globally.

A Shared Approach to Health Delivery

A successful model of partnership based on thorough understanding of local context with appropriate government involvement is exemplified by the work of Evance Mmbando, a fourth-year medical student at the Weill Bugando Medical School in Mwanza, Tanzania. In 2009, he jump-started a movement with a total of 12 medical students and a local faculty advisor focused on community education, raising awareness, and direct drug distribution of praziquantel and albendazole for the treatment of schistosomiasis and hookworm infection. Following a presentation at Yale University, he secured certification from the Ministry of Justice for the first student-led nongovernmental organization (NGO) on neglected tropical diseases in Tanzania. Working with US colleagues, he has shed light on the common tensions underlying the growing problem of health workers’ migration out of Tanzania. He presented his findings in a national symposium.8

From the spectrum of policy, training, advocacy, and social welfare interventions plus networks created in the cases presented, it is evident that a range of nonmedical enterprises driven by students can have major influence in the global health realm. One key point is that embedding these initiatives within communities (ie, local efforts and research on local issues) and generating the most appropriate, context-specific data to inform local decision-making results in the most enduring actions.

BROADENING STUDENTS’ EXPOSURE TO REAL-WORLD GLOBAL HEALTH

The previous student examples highlight the tremendous impact that a handful of enterprising, adventurous students can have on global health activities. However, not all of the contributions must be through spearheading ambitious new projects. Common avenues for student involvement are participating in well-established research projects of home institutions at foreign sites, or spending time working with civil society groups and NGOs that university institutions are often affiliated with, both of which are traditionally short-term. These experiences are aimed at providing the student with enough “exposure” to ensure a real-world understanding of how it is to work in an international setting. Core skills developed through these short-term (4–8-week) exposure experiences include the development of cultural competency, resourcefulness in unfamiliar surroundings, and the cultivation of compassion and understanding of heterogeneous global settings pays dividends in the long run.

Kollar and Ailinger studied the impact of an international experience on nursing students using the international experience model as a conceptual framework.9 Development of global perspectives through improvements in areas of substantive knowledge, perceptual understanding, personal growth, and interpersonal connections leads to an increased understanding of the world and current problem areas, empathy and open-mindedness, autonomy and self-confidence, and improved communication skills and cultural sensitivity.

The long-term impacts in terms of career course and trajectory can also be substantial. Students who have been exposed to international health settings are more likely to work in resource-poor areas or developing countries in the future, as compared with their counterparts who were not exposed to such settings.10,11 Participation in community health activities and humanitarian efforts are increased with a deeper understanding of social determinants of health and public-health issues.12 The perspectives gained from these experiences are also recounted with pride and enthusiasm by many of today's most well-known global health leaders (eg, prominent personalities at NIH, CDC, and other major health agencies).

However, taking a more macro view, are these short-term experiences, in their entirety, helpful? And to whom are they helpful? The benefits for elective destination institutions and their catchment areas are difficult to quantify and mostly relate to the anticipated benefits experienced by patients or communities in the future. To date, the literature has focused on positive career impacts through participation/interest in global health work, primary care, and care to underserved populations (both abroad and in the United States).10,13 International work has been thought to be an excellent way to reinforce the tenet that physicians should practice the qualities of altruism and compassion and have a social responsibility to the poor.14,15 These programs are hugely influential in student development and maturation.

In a systematic review examining this topic, 11 key articles on the significance of international health electives by Jeffrey et al.16 showed that these experiences contribute positively to student learning and career choices. Negatively, students are frequently unable or unprepared to assist the hosting facilities with the clinical workload. The unethical expectations sometimes placed on students to participate in clinical activities that they are not qualified to perform continues to be an unchecked problem.17 The authors further note problems of personal safety that accompany informal or unstructured electives. Although these instances are more relevant to programs run purely by NGOs that actively recruit students, they are pertinent given the volume of students involved and the connotations that resonate from these activities.

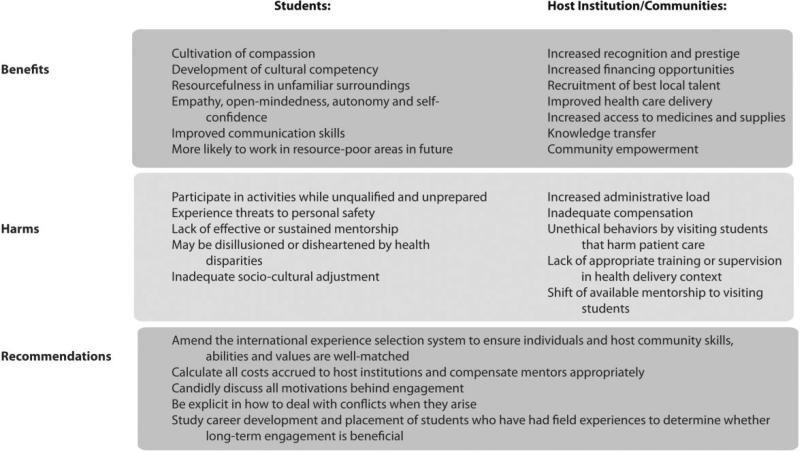

There is also a fundamental tension between the benefits of exposing students to global health field experiences for career development versus the burdens the students themselves place on their hosts. Although we cannot quantify the pros and cons, we argue that the balance of this issue determines whether a person should be eligible to go abroad for an exposure experience. From our observations, it appears that current eligibility standards are more tightly linked to availability of funding. We propose amending the international experience selection system to ensure that individuals and host-community skills, abilities, and values are well-matched (Figure 2).

Fig 2.

Collaboration between students and host communities in global health care.

Long-Term Engagement

Whereas short-term experiences might not afford the interested student the time or cultural context to contribute meaningfully, it is often assumed that longer-term experiences (eg, 1-year) do. An informal survey of the authors, however, revealed a set of inherent tensions for short- and long-term engagement in global health activities in 3 domains: attitudinal, sociocultural, and ethical. See Figure 2 for a complete set of benefits and harms for students and local host institutions/communities.

Attitudinal Changes

Students tend to be risk-taking, eager, idealistic, keen, and willing to question existing paradigms and frameworks. They often have not yet fallen prey to feeling hindered by issues of feasibility or third-party influences, and tend to provide fresh enthusiasm, challenging assumptions of the generation preceding theirs. However, involving students heavily in global health activities also carries several concerns that are voiced by mentors, particularly in host countries. This risk-taking spirit can manifest itself in detrimental ways, whether through a cavalier attitude or unethical behaviors. For instance, the ethical implications of providing care without appropriate training, preparation, and/or supervision is an important consideration. Anecdotal accounts of students returning from poor countries “bragging” about performing procedures for which they are not qualified in the United States are common.

Additionally, it is important to be cognizant of the dominant position that developed nations’ institutions continue to hold in structuring the priorities, terms, and funds of “global health” programs. As McFarlane et al. discuss, although the intentions of serving vulnerable populations and improving health equity in developing countries are altruistic, it is naive to ignore the trend of the internationalization of higher education and its potential influence.18 Global health work can raise the prestige of an institution and attract high-quality students and researchers, ultimately serving a university's self-interests.19 Therefore, it is necessary to consider within this context how developing-country institutions might also be strengthened and benefit from global health activities in a more equitable way. Even giving students a heightened awareness of this dimension of their experience, we believe, could critically shape how they conceptualize their role and future career.

Sociocultural Differences

Related to this, another key issue involves sociocultural differences, particularly working cultures. These differences can sometimes be heightened instead of attenuated. The trained, sensitive student will do a great job of integrating himself or herself into the host institution's mode of working. However, some students are either socially unaware or exude a sense of entitlement based on the freedoms they are used to in the United States and narrowly set about achieving their own agendas. This results in tensions with their hosts and may even negatively influence collaborative partnerships that their professors or home institutions have worked hard to cultivate. Candid discussions with program managers (and students) reveal that this is more common than one might imagine.

Ethical Behavior

Finally, there is a low awareness of the lack of genuine co-benefits to host communities that sponsor students. Most developing-country centers have few top-tier scientists and physician-scientists. These mentors are often responsible for mentoring large groups, and therefore end up splitting their time very thinly between their students, fellows, and residents. The addition of foreign students means more to handle. Students might pose a resource strain on local institutions or in some cases attract more attention than local students. There have been reports of foreign students, particularly in the field of surgery, receiving preferential treatment by being shown the more “interesting” cases, potentially hindering the educational experience of the local medical students.20

To help navigate these tensions, Crump et al. detail an excellent framework (Working Group on Ethics Guidelines for Global Health Training) to ensure success and ethical behavior in global health activities by trainees.21 We support the ethos underlying this framework, and suggest that by designing programs that adhere to this framework, and by providing guidance to students, universities can proactively play a significant role in preventing and/or addressing the concerns raised previously. Briefly, the considerations include: (1) calculating all costs accrued to host institutions and compensating mentors appropriately; (2) candidly discussing all motivations behind engagement; and (3) being explicit in how to deal with conflicts when they arise. In addition, we recommend the deeper study of career development and placement of students who have had field experiences to determine whether long-term engagement is, in the end, beneficial and influences responsible engagement with communities over a career. We should strive to invest in, train, and support individuals deemed to have potentially high impacts.22

NEXT FRONTIER OF GLOBAL HEALTH EDUCATION

As this article focuses on the role of students, it is important also to discuss the role of education in shaping the development of careers in global health. The case examples cited can be described as the work of extraordinary, visionary students who seized fortuitous opportunities. There remain many more talented, capable students from a variety of disciplines who have potential interests in global health that must be engaged.

The role of education should be, in part, to focus and productively harness this change-making energy of students. This will in turn act as a valuable experiential learning opportunity, but entails removing barriers to long-term flexibility, including student debt concerns. Additionally, awarding nontraditional credit for activities related to global health activities can help promote serious longitudinal activities in this field.23 Students must be given freedom and opportunities to engage their interests. We believe this “rebellious” spirit of bright minds, however, needs to be honed further with appropriate and sensible supervision and mentorship.

Based on the case studies and the review of the positive and negative implications of students’ roles in global health activities, we presently offer the following 4 recommendations:

Recommendation 1. Institutions must conceptualize global health as an interdisciplinary field that draws upon the efforts of a variety of disciplines. In the same way that medical schools are beginning to support medical students interested in global health, so should entire universities, both at the graduate and undergraduate level, seek to encourage students interested in global health. Generally, we envision the role of undergraduates being primarily focused on learning and building future interests in global health, while we envision graduate student involvement incorporating this, but also including mobilization and coordination of diverse skills. As our case studies illustrate, many fields can impact global health, and we see the university as a nidus to connect students seeking to impact global health.

Recommendation 2. Strengthen mentorship and guidance of students longitudinally. Technology and social media provide excellent opportunities to improve upon this. For example, Global Health Delivery Online (http://www.ghdonline.org) provides students from around the world a forum for sharing ideas and developing collaborative projects.

Recommendation 3. Augment and diversify formalized programs focused on global health. Ideally these programs would be competitive, prestigious, well-funded, well-conceived, and well-organized. Current examples are the Fogarty International Clinical Research Scholars program and the CDC-Hubert Global Health Fellowship program. Other examples might include fellowships in global health–related policy, fellowships for veterinary students interested in zoonoses, or fellowships geared toward health-related economic development. The competitive nature of the programs would help ensure the opportunity to engage and select from the best of pool of students. Such programs would also provide opportunities for long-term follow-up of career paths and trajectories, tracking the direct future returns on investing early in students’ formative career-development years.

Recommendation 4. Specify core global health competencies and communicate them in pre-departure preparation for students.24 A deeper understanding of student roles in both the short-term contexts and long-term trajectories of projects or experiences before leaving the country can make a significant impact on their contribution as well as minimize undue burdens on the host institution. This type of training for students is highly variable in quantity and quality with regard to host organizations or originating institutions. Although orientation sessions need not be standardized, and one could argue that they certainly should not be, given the vastly heterogeneous countries, projects, and objectives, they ought to adhere to a competency-based curriculum of pertinent preparatory topics, including the country's history and sociology, local community perspectives and ideas, and the sustainability of projects. Additionally, this will guide the evaluative process to be more definitive and fruitful. Attention should be also paid to the bidirectionality of opportunities; global health activities would benefit from greater facilitation of students from developing countries to also participate in exchanges in other countries.

CONCLUSION

In this article, we have laid out a framework of engagement that captures student impacts in three nonmedical thematic areas: (1) fostering an enabling policy environment toward greater health equity; (2) understanding and working within the local context and governments’ needs; and (3) leading bidirectional partnerships. We provided case studies to illustrate each key theme and demonstrate how students around the world, from clinical and nonmedical backgrounds, are already actively engaging in these issues. Reflections from a nonexhaustive set of case examples demonstrates the passionate, urgent, uninhibited, and unrelenting efforts of young people in raising awareness and serving humanitarian needs.

However, it is also clear that there is a spectrum of engagement where the potentially powerful and positive impacts are counterbalanced by suboptimal tact and sociocultural disconnects. We propose a set of recommendations that may help optimize the blurred gray area between these extremes–finding the appropriate balance between tradeoffs of energetic, innovative, “full throttle” engagement versus respectful conformity. For further guidance, the interested student is strongly recommended to an excellent resource prepared by Sujal Parikh and colleagues at the University of Michigan (for students and by students), a Student Handbook for Global Engagement.25

The current millennial generation of students is different from those who came before us. These students (including the authors) view the world differently, armed with a different set of tools at their disposal and a different attitude on how to address challenges. This may partially explain the “freedoms” and entitlement students feel, and part of it may suggest why they have bonded with global health. This energy should be harnessed, as the new wave of students has a real chance at bridging large gaps through use of information technology and the recruitment of other unconventional specialties (eg, urban design) to bear on global health, much unlike generations before them. Even though they may not fully appreciate the new-wave approaches of this century, even hosts and mentors must consider their own adaptation to the new generation. After all, this is a generation that is to date the most well-connected and has the greatest amount of information at its disposal, and hopes are held high that fruitful societal change will emerge from the young professionals who exit universities in the 21st century.

The scope of global health activities extends beyond health professionals (or health professionals-in-training) alone. Going forward, the modus operandi in global health should be collaboration across disciplines and national boundaries.

The most enduring actions result from embedding these initiatives within communities (local efforts and research on local issues) and generating the most appropriate, context-specific data to inform local decision-making.

The international experience selection system should be amended to ensure that individuals and host-community skills, abilities, and values are well-matched.

We recommend the deeper study of career development and placement of students who have had field experiences to determine whether long-term engagement is, in the end, beneficial and influences responsible engagement with communities over a career.

The role of education should be, in part, to focus and productively harness this change-making energy of students.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

Potential conflict of interest: Nothing to report.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kraemer JD, Siedner MJ, Canepa C, et al. Effect of community health worker supplementation to ART delivery on HIV patient survival and retention in resource-poor, post-conflict Liberia.. Poster presented at: XVIII International AIDS Conference; Vienna, Austria. August 2010.p. PE0883. [Google Scholar]

- 2.University of Michigan Center for Global Health [January 31, 2011];In loving memory of Sujal Parikh. http://www.globalhealth.umich.edu/sujalparikh.html.

- 3. [January 31, 2011];Mzungu Bye, Sujal Parikh's blog. http://sujalparikh.blogspot.com.

- 4.Kapczynski A, Crone ET, Merson M. Global health and university patents. Science. 2003;301:1629. doi: 10.1126/science.301.5640.1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chokshi DA, Rajkumar R. Leveraging university research to advance global health. JAMA. 2007;298:1934–1936. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.16.1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Association of University Technology Managers [January 31, 2011];Statement of Principles and Strategies for the Equitable Dissemination of Medical Technologies. http://www.autm.net/source/Endorsement/endorsement.cfm?section=endorsement.

- 7.Maciag K, Kishore SP. Generic drugs for developing nations. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2010;8:530. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2345-c1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson K, Asher J, Rosborough S, et al. Association of combatant status and sexual violence with health and mental health outcomes in postconflict Liberia. JAMA. 2008;300:676–690. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.6.676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mmbando E. Uniting Tanzanian medical students to reverse the brain drain. [January 31, 2011];Speaking of Medicine Blog, PLoS Medicine. http://blogs.plos.org/speakingofmedicine/2009/09/28/uniting-tanzanian-medical-students-to-reverse-the-brain-drain. Published September 28, 2009.

- 10.Kollar SJ, Ailinger RL. International clinical experiences: long-term impact on students. Nurse Educ. 2002;27:28–31. doi: 10.1097/00006223-200201000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramsey AH, Haq C, Gjerde CL, et al. Career influence of an international health experience during medical school. Fam Med. 2004;36:412–416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chiller TM, De Mieri P, Cohen I. International health training: the Tulane experience. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 1995;9:439–443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith JK, Weaver DB. Capturing medical students’ idealism. Ann Fam Med. 2006;4(suppl 1):S32–S37. doi: 10.1370/afm.543. discussion S58–S60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Flatau PM. International health electives: what is the impact on primary care recruitment? Fam Med. 2010;42:238–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heck JE, Wedemeyer D. A survey of American medical schools to assess their preparation of students for overseas practice. Acad Med. 1991;66:78–81. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199102000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Faulkner LR, McCurdy RL. Teaching medical students social responsibility: the right thing to do. Acad Med. 2000;75:346–350. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200004000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jeffrey J, Dumont RA, Kim GY, et al. Effects of international health electives on medical student learning and career choice: results of a systematic literature review. Fam Med. 2011;43:21–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shah S, Wu T. The medical student global health experience: professionalism and ethical implications. J Med Ethics. 2008;34:375–378. doi: 10.1136/jme.2006.019265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Macfarlane SB, Jacobs M, Kaaya EE. In the name of global health: trends in academic institutions. J Public Health Policy. 2008;29:383–401. doi: 10.1057/jphp.2008.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yach D, Bettcher D. The globalization of public health, II: the convergence of self-interest and altruism. Am J Public Health. 1998;88:738–744. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.5.738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Riviello R, Ozgediz D, Hsia RY, et al. Role of collaborative academic partnerships in surgical training, education, and provision. World J Surg. 2010;34:459–465. doi: 10.1007/s00268-009-0360-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crump JA, Sugarman J. Ethics and best practice guidelines for training experiences in global health. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;83:1178–1182. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.10-0527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bloomfield GS, Huffman MD. Global chronic disease research training for fellows: perspectives, challenges, and opportunities. Circulation. 2010;121:1365–1370. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.923144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kishore S, Crager S. [January 31, 2011];Supporting the next generation of product developers: the trainee perspective. http://healthresearchpolicy.org/blog/2010/oct/12/supporting-next-generation-product-developers-trainee-perspective. Published October 12, 2010.

- 25.Battat R, Seidman G, Chadi N, et al. Global health competencies and approaches in medical education: a literature review. BMC Med Educ. 2010;10:94. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-10-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.University of Michigan Center for Global Health [January 31, 2011];Student Handbook for Global Engagement. http://www.globalhealth.umich.edu/pdf/CGH%20standards%20handbook.pdf.