Abstract

BACKGROUND

Subcutaneous implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (S-ICDs) are attractive for preventing sudden cardiac death in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) as they mitigate risks of transvenous leads in young patients. However, S-ICDs may be associated with increased inappropriate shock (IAS) in HCM patients.

OBJECTIVE

The purpose of this study was to assess the incidence and predictors of appropriate shock and IAS in a contemporary HCM S-ICD cohort.

METHODS

We collected electrocardiographic and clinical data from HCM patients who underwent S-ICD implantation at 4 centers. Etiologies of all S-ICD shocks were adjudicated. We used Firth penalized logistic regression to derive adjusted odds ratios (aORs) for predictors of IAS.

RESULTS

Eighty-eight HCM patients received S-ICDs (81 for primary and 7 for secondary prevention) with a mean follow-up of 2.7 years. Five patients (5.7%) had 9 IAS episodes (3.8 IAS per 100 patient-years) most often because of sinus tachycardia and/or T-wave oversensing. Independent predictors of IAS were higher 12-lead electrocardiographic R-wave amplitude (aOR 2.55 per 1 mV;95% confidence interval 1.15–6.38) and abnormal T-wave inversions (aOR 0.16; 95% confidence interval 0.02–0.97). There were 2 appropriate shocks in 7 secondary prevention patients and none in 81 primary prevention patients, despite 96% meeting Enhanced American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association criteria and the mean European HCM Risk-SCD score predicting 5.7% 5-year risk. No patients had sudden death or untreated sustained ventricular arrhythmias.

CONCLUSION

In this multicenter HCM S-ICD study, IAS were rare and appropriate shocks confined to secondary prevention patients. The R-wave amplitude increased IAS risk, whereas T-wave inversions were protective. HCM primary prevention implantable cardioverter-defibrillator guidelines overestimated the risk of appropriate shocks in our cohort.

Keywords: Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, Inappropriate shocks, Risk stratification, Subcutaneous implantable cardioverter-defibrillator, Sudden cardiac death

Introduction

Compared to other cardiovascular conditions, patients are diagnosed with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) at a relatively young age (median 45.8 years; interquartile range 30.9–58.1 years) and may have an elevated risk of ventricular arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death (SCD).1 The subcutaneous implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (EMBLEM S-ICD, EMBLEM MRI S-ICD, S-ICD, Boston Scientific, Natick, MA) is frequently considered for younger patients in whom an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) but not pacing is indicated as a strategy to avoid risks of chronic indwelling transvenous leads.2

Despite these advantages, the S-ICD sensing algorithm, which makes use of 3 electrogram vectors analogous to the standard 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG), may be prone to errors in arrhythmia detection leading to inappropriate shock (IAS)—most commonly via T-wave oversensing (TWOS). Indeed, in a contemporary review of S-ICD complications, an estimated 32% of all IAS were due to TWOS.3 HCM patients frequently have pronounced QRS and T-wave abnormalities on their baseline ECGs, leading to a higher risk of TWOS and IAS. Preimplantation screening simulates the device’s 3 sensing vectors and attempts to identify patients at risk of TWOS. This has resulted in 14%–38% of HCM patients being deemed inappropriate for S-ICD implantation.4–7 Nevertheless, IAS has remained a significant issue for patients with HCM. The pooled EFFORTLESS (Evaluation oF FactORs ImpacTing CLinical Outcome and Cost EffectiveneSS of the S-ICD) and IDE (Investigational Device Exemption) cohort data for HCM patients demonstrated IAS incidence of 12.5% per year over a 22-month follow-up,8 although more recent advances in sensing algorithms and device programming have led to reductions in the rates of IAS of up to 68%.9

In an evolving landscape of S-ICD utilization, the objectives of the present study were to determine the incidence of both appropriate and inappropriate device therapies in a multicenter cohort of HCM patients with an S-ICD and to determine predictors of IAS.

Methods

Study design and data collection

Consecutive patients with HCM implanted with an S-ICD between 2014 and 2019 at 4 centers (9–36 patients per center) were included in our cohort. Data on baseline patient characteristics, pre- and postimplant screening, and patient follow-up were retrospectively collected from electronic medical records. Pre-implant ECGs were analyzed systematically. QRS and QT intervals were electronically derived. R- and T-wave amplitudes were manually measured from isoelectric baseline to peak (or nadir if the T wave was predominantly negative). The maximum amplitude in all leads was recorded. T-wave inversions (TWIs; in leads other than V1 and AVR in which they are normal variants) were recorded. All data were anonymized and stored centrally. The study was conducted with approval of the institutional review boards at all sites.

Implant data and ICD programming

The decision to implant an S-ICD was based on clinical indication as determined by the treating clinician. Patients were screened with the 3-lead surface ECG using the Boston Scientific screening tool and were required to pass at least 1 screening vector in at least the supine and standing positions. Additional screening in the prone position or with exercise testing was performed in 11 and 5 patients, respectively. The total number of combinations of body positions (including exercise) and sensing vectors screened was recorded as “number of vectors screened” for later analysis. The device was implanted using a standard 2- or 3-incision technique.10,11 Defibrillation threshold testing was performed at the discretion of the implanting clinician. All devices were programmed with 2 therapy zones: a conditional shock zone variably set at 180–240 beats/min and a shock zone at 200–250 beats/min.

Stored electrograms of all shocks were reviewed independently by 2 investigators and adjudicated as appropriate or inappropriate. Etiology of IAS was determined by the investigators. Interobserver agreement was observed in each case. Episodes where multiple IAS were delivered sequentially as part of the same clinical encounter were counted as 1 IAS, provided that they occurred via the same mechanism.

Statistical analysis

Variables were selected a priori as potential risk factors for IAS on the basis of clinical experience and prior studies on IAS in S-ICD. Descriptive statistics were calculated for continuous variables using mean ± SD or median with interquartile range and categorical variables using frequency with percentage. To identify potential risk factors for IAS, we performed Firth penalized logistic regression. This modeling approach was used to reduce bias that may result from traditional logistic regression because of our small sample size and rare outcome.12 Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% profile likelihood confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated from univariable and multivariable models. Complete case analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Patient population and implant characteristics

The study cohort included 88 HCM patients (Table 1) who were followed for a mean of 2.7±1.3 years after S-ICD implantation. The median age was 43.0 years (interquartile range 32.2–55.4 years; range 17.1–73.4 years), and 63 (71.5%) were male. Of these patients, 7 (7.9%) received S-ICD for secondary prevention and the remaining 81 (92%) for primary prevention. Ten patients received the first generation S-ICD (SQ-RX Model 1010 Boston Scientific; Natick, MA), 29 received EMBLEM S-ICD Model A209 (Boston Scientific; Natick, MA), and 49 received Model A219 (Boston Scientific; Natick, MA). Eighty-six leads were implanted in the left parasternal position and 2 in the right parasternal position. Upon implantation, all patients received dual-zone programming, with the conditional zone set at 207 ± 12 beats/min and the shock zone at 241 ± 11 beats/min. Defibrillation threshold testing was performed in all but 6 patients. SMARTPass was programmed on initially in 57 of 88 patients. Postimplant exercise QRS optimization occurred in 7 patients.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Inappropriate shock |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Yes (n=5) | No (n=83) | P |

| Age (y) | 36.1 (32.3–43.2) | 43.9 (32.2–55.6) | .6873 |

| Female sex | 0 (0.0) | 25 (30.1) | .3158 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 31.1 (23.2–32.4) | 27.1 (23.9–30.1) | .5961 |

| BSA (m2) | 2.2 (2.1–2.4) | 2.0 (1.8–2.2) | .0954 |

| Implant indication | |||

| Primary | 5 (100.0) | 76 (91.6) | |

| Secondary | 0 (0.0) | 7 (8.4) | |

| HCM Risk-SCD score | 6.6 (6.1–8.7) | 4.5 (3.8–6.6) | .0293 |

| Medications at baseline | |||

| β-Blockers | 3 (60.0) | 59 (71.1) | .6298 |

| Calcium channel blockers | 2 (40.0) | 14 (16.9) | .2227 |

| β-Blocker or calcium channel blocker | 5 (100.0) | 65 (78.3) | .5787 |

| Baseline QRS width (ms) | 136.0 (94.0–144.0) | 92.0 (86.0–102.0) | .0227 |

| Baseline QTc interval (ms) | 468.0 (447.0–507.0) | 444.0 (424.0–463.0) | .0536 |

| Baseline R-wave amplitude (all leads) (mV) | 2.9 (2.2–3.1) | 1.8 (1.3–2.4) | .0365 |

| Baseline T-wave amplitude (all leads) (mV) | 0.5 (0.4–0.6) | 0.5 (0.3–0.6) | .4924 |

| R/T-wave ratio (all leads) | 18.6 (18.2–23.5) | 25.0 (17.9–40.7) | .1896 |

| Ejection fraction (%) | 65.0 (57.0–65.0) | 65.0 (60.0–70.0) | .3137 |

| Presence of T-wave inversions | 2 (40.0) | 65 (78.3) | .0858 |

| Maximal left ventricular wall thickness (mm) | 22.6 (22.0–23.0) | 18.0 (15.0–23.0) | .3722 |

| Left ventricular mass (g) | 282.0 (149.0–318.8) | 187.0 (132.4–249.5) | .2505 |

| LVOT pressure gradient (resting) (mm Hg) | 6.0 (5.8–10.0) | 7.0 (5.0–22.0) | .8215 |

| LVOT pressure gradient (dynamic) (mm Hg) | 57.5 (24.0–106.5) | 14.0 (5.0–41.8) | .0915 |

| Presence of LGE on CMR imaging | 3 (60.0) | 72 (86.7) | .1382 |

| Presence of apical aneurysm | 0 (0.0) | 4 (4.8) | >.9999 |

| Vectors screened, number | 9.0 (6.0–9.0) | 6.0 (6.0–6.0) | .0903 |

| Vectors passed screening, proportion | 0.7 (0.4–1.0) | 0.8 (0.7–1.0) | .3621 |

| Conditional shock zone programming | 210.0 (210.0–210.0) | 210.0 (210.0–220.0) | .4066 |

| Shock zone programming | 220.0 (220.0–240.0) | 240.0 (240.0–250.0) | .0987 |

| SMARTPass programming used | 3 (60.0) | 57 (68.7) | .6003 |

Values are presented as median (interquartile range) or n (%).

BMI = body mass index; BSA = body surface area; CMR = cardiovascular magnetic resonance; HCM = hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; LGE = late gadolinium enhancement; LVOT = left ventricular outflow tract; QTc = corrected QT; SCD = sudden cardiac death.

IASs: Incidence, etiology, and clinical responses

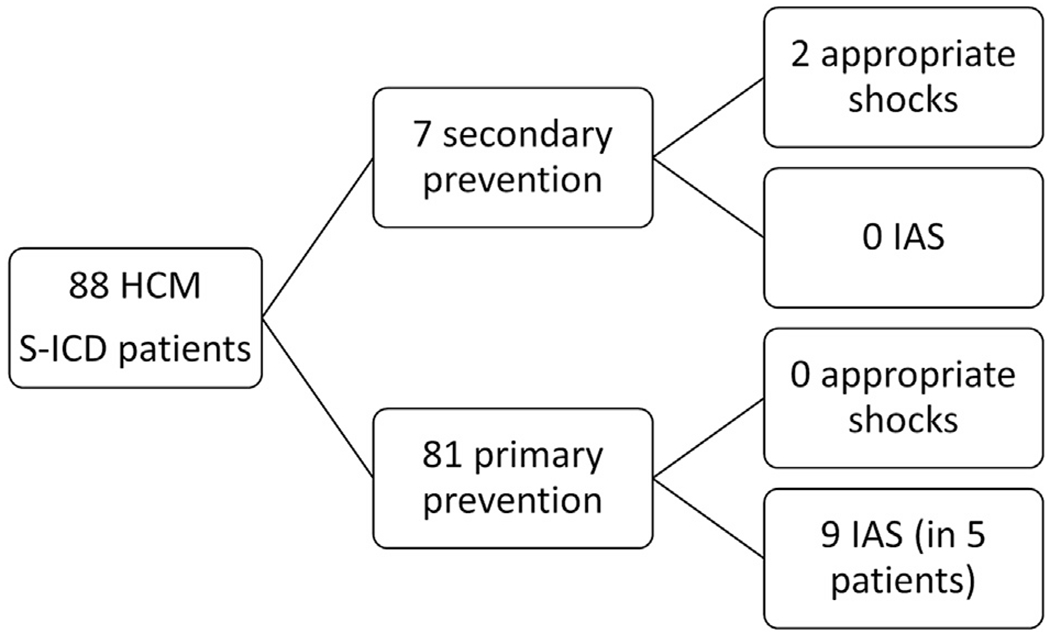

Five patients (5.7%) experienced a total of 9 IAS over a mean follow-up of 2.7 ± 1.3 years (incidence 3.8 per 100 patient-years) (Figure 1 and Table 2). Seven of 9 IAS (78%) occurred within a year of implantation (median time from implantation to first IAS 9.2 months). Five of 9 IAS were due to TWOS, 2 of which occurred in the setting of rapidly conducted atrial fibrillation (AF) (Figure 2A) and 3 in the setting of sinus tachycardia (Figure 2B). Three IAS were due to sinus tachycardia during exercise without TWOS: 1 of these was in the conditional zone (inappropriately discriminated) and 2 of these were in the shock zone (where morphology discrimination is not applied). One IAS was due to rapidly conducted AF with rates in the shock zone. Three IAS (all sinus tachycardia related) occurred in the setting of medication (β-blocker or calcium channel blocker) nonadherence, and all 6 sinus tachycardia–related IAS occurred during exercise (snowboarding and wakeboarding) or sexual intercourse. None of the patients who had received IAS had undergone preimplant exercise screening, but 3 had undergone screening in the prone position.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and subcutaneous implantable cardioverter-defibrillator. Inappropriate shocks (IASs) occurred in 5 patients (5.7%) with an incidence of 3.8% per year.

Table 2.

Etiologies of inappropriate shocks and clinical response

| Etiology | Number of patients (%) | Clinicians’ response |

|---|---|---|

| TWOS | 5 (55%) | |

| During sinus tachycardia | 3 | Exercise QRS template (2), change sensing vector (2) |

| During AF | 2 | Turn on SMARTPass, AF rate control (2), change sensing vector |

| Sinus tachycardia without TWOS | 3 (33%) | |

| In the shock zone | 2 | Increase shock zone rate |

| In the conditional zone (inappropriate discrimination) | 1 | Exercise QRS template, increase conditional zone rate |

| AF in the shock zone | 1 (11%) | AF rate control |

AF = atrial fibrillation; TWOS = T-wave oversensing.

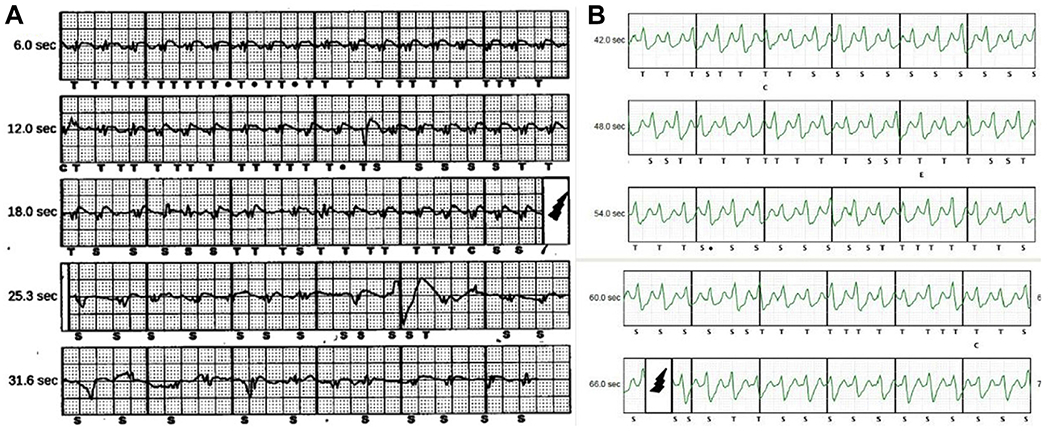

Figure 2.

Inappropriate shocks due to T-wave oversensing (TWOS). A: A 74-year-old patient with TWOS during atrial fibrillation (AF) with device-detected rates in the shock zone (does not apply morphology discrimination). Clinician response was to change from the alternate to the secondary sensing vector and improve rate control for AF. B: A 32-year-old man with TWOS during sinus tachycardia while snowboarding, with device-detected rates in the conditional zone (not a morphology match by discrimination). Clinician response was to increase the conditional zone rate from 200 to 210 beats/min and perform exercise-based QRS template optimization of the device.

Clinical responses to IAS (Table 2) were increasing conditional zone rate (n=3 IAS episodes), increasing shock zone rate (n=2), changing sensing vector (n=2), optimizing QRS morphology template during exercise (n=3), medication changes (n=5), and turning on SMARTPass filtering (in the 1 patient in whom it was not on previously). A detailed description of IAS events and responses can be found in Online Supplemental Table 1.

Predictors of IAS

In univariable analyses, potential risk factors associated with IAS were wider QRS complex (OR 1.08 per 1 ms; 95% CI 1.03–1.15), longer corrected QT interval (OR 1.03 per 1 ms; 95% CI 1.00–1.07), higher 12-lead ECG R-wave amplitude (maximal of all leads; OR 2.76 per 1 mV; 95% CI 1.14–7.11), and lower shock zone detection rate (OR 0.94 per beats/min; 95% CI 0.88–1.00) compared to those without IAS (Table 3). Multivariable analysis, however, identified only R-wave amplitude (adjusted OR 2.55 per 1 mV; 95% CI 1.15–6.38) and the presence of TWI (adjusted OR 0.16; 95% CI 0.02–0.97) as independent risk factors for IAS. The mean maximal R-wave amplitude in patients receiving IAS was 2.9±1.0 mV (range 1.7–4.4 mV) compared with 1.9±0.8 mV (range 0.6–4.5 mV) in those who did not receive IAS (P=.016).

Table 3.

Predictors of inappropriate shocks

| Univariable model |

Multivariable model |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) |

| Age (per 1 y) | 1.00 (0.94–1.06) | |||

| Female sex | 0.21 (<0.01–1.95) | |||

| BMI (per 1 kg/m2) | 1.02 (0.89–1.11) | |||

| BSA (per 1 m2) | 5.37 (0.53–46.34) | |||

| Presence of apical aneurysm | 1.53 (0.01–17.64) | |||

| β-Blocker at baseline | 0.58 (0.11–3.65) | |||

| Calcium channel blocker at baseline | 3.42 (0.53–19.32) | |||

| β-Blocker or calcium channel blocker at baseline | 3.11 (0.33–414.88) | |||

| HCM Risk-SCD score (per 1 unit) | 1.17 (0.96–1.40) | |||

| Baseline QRS width (per 1 ms) | 1.08 (1.03–1.15) | |||

| Baseline QTc interval (per 1 ms) | 1.03 (1.00–1.07) | |||

| Presence of T-wave inversions | 0.20 (0.03–1.12) | 0.16 (0.02–0.97) | ||

| Maximal R-wave amplitude (all leads, per 1 mV) | 2.76 (1.14–7.11) | 2.55 (1.15–6.38) | ||

| Maximal T-wave amplitude (all leads, per 1 mV) | 3.31 (0.07–65.39) | |||

| R/T-wave ratio (all leads, per 1 unit) | 0.96 (0.87–1.02) | |||

| Ejection fraction (per 1%) | 0.94 (0.86–1.03) | |||

| Maximal left ventricular wall thickness (per 1 mm) | 1.05 (0.90–1.22) | |||

| Left ventricular mass (per 1 g) | 1.01 (0.99–1.03) | |||

| LVOT pressure gradient (resting, per 1 mm Hg) | 1.00 (0.90–1.02) | |||

| LVOT pressure gradient (dynamic, per 1 mm Hg) | 1.01 (0.99–1.02) | |||

| Presence of LGE on CMR imaging | 0.20 (0.03–1.34) | |||

| Vectors screened (per 1 vector) | 1.07 (0.83–1.28) | |||

| Vectors passed screening (per 1 percent point) | 0.06 (<0.01–3.82) | |||

| Shock zone programming (per 1 beats/min) | 0.94 (0.88–1.00) | |||

| Conditional shock zone programming (per 1 beats/min) | 0.97 (0.90–1.06) | |||

| SMARTPass programming used | 0.47 (0.09–3.03) | |||

AOR = adjusted odds ratio; BMI = body mass index; BSA = body surface area; CI = confidence interval; CMR = cardiovascular magnetic resonance; HCM = hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; LGE = late gadolinium enhancement; LVOT = left ventricular outflow tract; OR = odds ratio; QTc = corrected QT; SCD = sudden cardiac death.

Bolded text indicates that the variable met statistical significance.

Appropriate shocks

Over an average of 2.7±1.3 years of follow-up (237.6 patient-years), only 2 of 88 patients received appropriate shocks and both had undergone S-ICD implant for secondary prevention. None of the 81 primary prevention patients received an appropriate shock. The incidence of appropriate shocks was 0, 9.8, and 0.8 per 100 patient-years in the primary prevention cohort, secondary prevention cohort, and entire cohort, respectively.

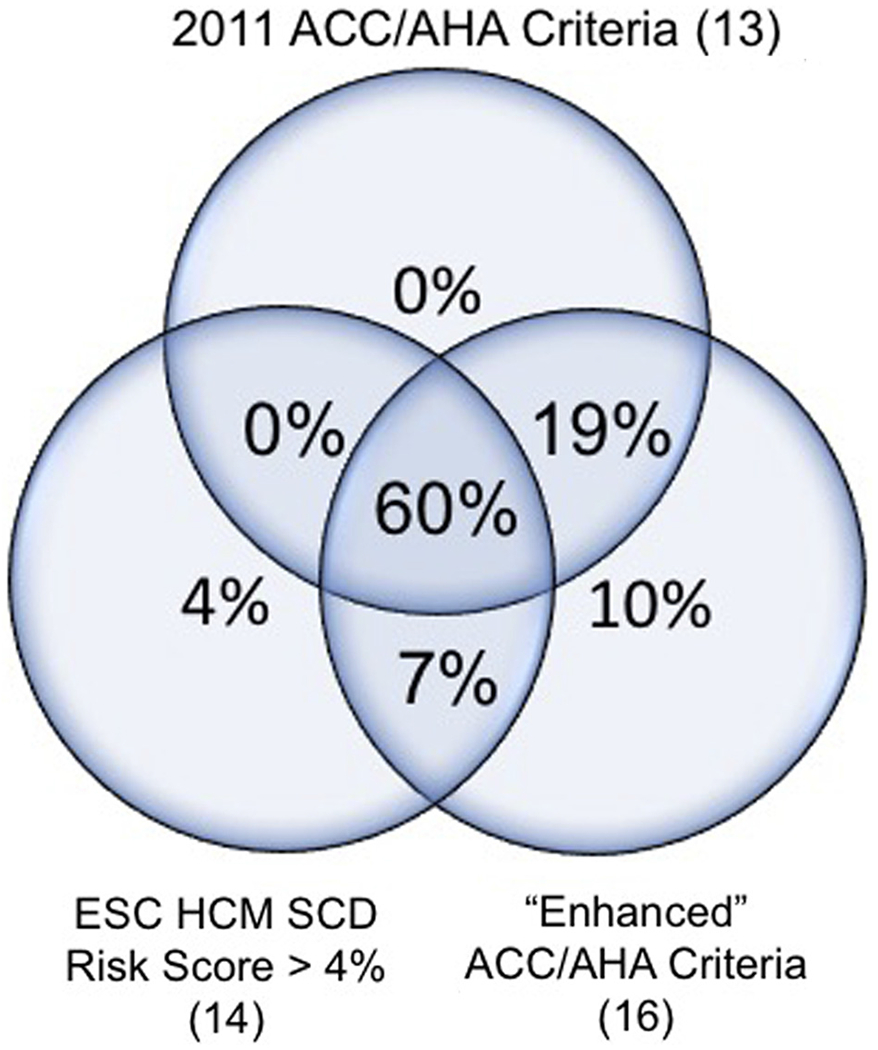

Given the absence of appropriate shocks in primary prevention patients, we retrospectively applied HCM SCD risk stratification criteria to determine the preimplantation SCD risk and further investigate a potentially low threshold for primary prevention implantation (Figure 3). Of the 77 patients in whom the 2011 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association HCM guidelines13 could be applied, 62 patients (81%) met class IIa indication and 15 (19%) met class IIb or class III indication. The externally validated European HCM Risk-SCD score14,15 predicted a 5.7% ± 3.4% 5-year risk of ventricular arrhythmias. Using an “appropriateness” threshold of 4% risk, 55 patients (71%) were considered appropriate whereas 22 (29%) were not. Finally, applying the “Enhanced” American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Strategy for prevention of SCD in high-risk patients with HCM proposed by Maron et al,16 73 (96%) satisfied an indication for ICD on the basis of these criteria whereas 3 (4%) did not. Sixty percent of patients satisfied all 3 criteria, 85% satisfied at least 2 criteria, 97% satisfied at least 1, and only 2 patients (3%) did not satisfy any criterion.

Figure 3.

Preimplantation implantable cardioverter-defibrillator implantation risk stratification. Numbers reflect the proportion of the primary prevention cohort that satisfied each or multiple of the 3 risk stratification criteria. Two patients (3%) did not satisfy any of the criteria. ACC = American College of Cardiology; AHA = American Heart Association; ESC = European Society of Cardiology; HCM = hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; SCD = sudden cardiac death.

Other complications

Two patients ultimately underwent S-ICD extraction with implantation of a transvenous device: one due to sudden battery failure followed by failed defibrillation threshold testing after generator exchange and the second patient due to symptomatic 2:1 atrioventricular block that required pacing. There were no episodes of SCD or ventricular arrhythmias that were unsuccessfully treated by the S-ICD.

Discussion

IASs

In this multicenter study, 5.7% of 88 patients with HCM received IAS from the S-ICD over a mean follow-up of 2.7 years (~234 patient-years), with an IAS incidence of 3.8% per year. This is lower than described in earlier HCM S-ICD cohorts, which reported rates ranging from 6.2% to 12.5% over 17–22 months of follow-up.6–8 A potential explanation is the use of SMARTPass filtering, which was used in 68% of our cohort, but was not yet available in prior studies.6–8 The use of SMARTPass in our cohort was associated with an OR of 0.49 (95% CI 0.09–3.03) for IAS, but this did not achieve statistical significance. Another potential etiology for lower IAS rates in our study is dual-zone programming, which has been associated with reduced IAS in the general S-ICD population as well as patients with HCM with an S-ICD.8,17 Dual-zone programming was used in all our patients, but not uniformly (72%–84%) in prior studies.7,8 Finally, contemporary ICD programming that trends toward higher tachycardia detection rates may have contributed to our lower IAS rates. In our study, our conditional and shock zones were set at 207 ± 12 and 241 ± 11 beats/min, respectively, compared with 200 ± 21 and 226 ± 18 beats/min in the EFFORTLESS S-ICD registry.8 Indeed, a higher shock zone detection rate was associated with a reduction in IAS in our study’s univariable models.

Our data correspond to trends in studies of the broader S-ICD population, which show a reduction of IAS from 11.7%–20.5% over 3–5 years of follow-up in earlier studies18,19 down to 3.4% over a 2-year period3 in more contemporary studies. Transvenous ICD studies show similar trends, as the era of high rate and long delay programming has decreased the IAS prevalence from the annualized rates of 6.4%–7.6% in older studies20,21 down to 3.4% in studies with more contemporary programming.22

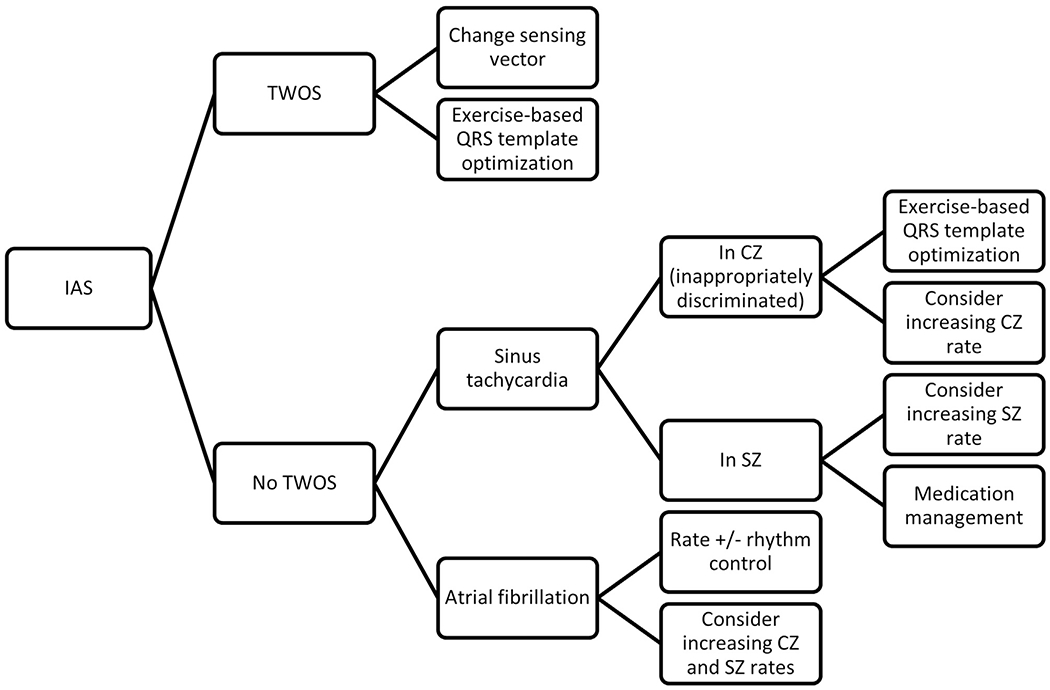

Patients with HCM present unique S-ICD IAS challenges in that they are younger, more likely to be physically active (thus more susceptible to sinus tachycardia), and have marked QRS and T-wave abnormalities. Indeed, in our study, 6 of 9 IAS episodes were due to sinus tachycardia during exercise either resulting in TWOS or simply falling into S-ICD tachytherapy zones. Three of these were associated with medication nonadherence, which further predisposed patients to sinus tachycardia. This stresses the importance of dual-zone programming with higher rate cutoffs as well as regularly counseling on medication adherence as a means of avoiding IAS. In Figure 4 (and Online Supplemental Figure 1), we present an algorithmic approach to the management of IAS in patients with HCM.

Figure 4.

Algorithm for the management of subcutaneous implantable cardioveter-defibrillator inappropriate shocks (IASs) in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) patients. This algorithm does not address non–T-wave oversensing (TWOS) forms of oversensing such as myopotentials, electromagnetic interference, or lead fracture, none of which occurred in our study. A more detailed algorithm is presented in Online Supplemental Figure 1. CZ = conditional shock zone; SZ = shock zone.

Our study is the first to investigate predictors of IAS in patients with HCM and S-ICD. We identified the lower shock zone detection rate and prolonged QRS and QT intervals as univariable risk factors for IAS and higher R-wave amplitude as an independent multivariable risk factors for IAS (with TWIs being independently “protective” of IAS). Prior studies in the broader S-ICD population have corroborated that IAS is associated with prolonged QRS (particularly right bundle branch block) and corrected QT duration.23 R-wave amplitude has not been previously shown to be an IAS risk factor. Our finding may seem paradoxical, as IAS are often due to TWOS in the setting of tall T waves relative to R-wave amplitude. However, there are 2 possible mechanisms. S-ICDs are designed, likely because of auto-decay sensing for the detection of VF, to sense a maximal QRS amplitude of 4.0 mV. Since the S-ICD rectifies the QRS signal (converting negative signal to positive), patients with particularly tall R waves may be sensitive to oversensing of Q or S complexes, which may simulate TWOS.24 A second mechanism is that HCM patients with taller R waves likely have more aggressive forms/stages of the disease with greater hypertrophy and outflow tract obstruction and thus are more likely to have sinus tachycardia and AF, both of which were etiologies of IAS in our study. These 2 mechanisms may, in fact, be synergistic, as both higher R/T-wave ratios and advanced HCM have been associated with the failure of S-ICD preimplantation screening.5 Our finding that TWIs were independently associated with fewer IAS is plausible, as it reduces the likelihood of double-counting T waves, but warrants further evaluation, as 2 of our 5 patients with IAS also had TWIs, and a prior study has associated TWIs with the failure of S-ICD preimplantation screening.4

While exercise testing has been associated with screen failure in up to 9% of patients with HCM,5,25 no study has demonstrated a link between preimplant exercise screening and reduction in IAS. In our study, no patient who underwent prescreening with exercise testing had IAS, although the sample size is too limited to determine a direct relationship.

The role of routine postimplant exercise QRS template optimization is unclear; some studies have shown that routine exercise optimization does not reduce TWOS and IAS, although these studies did not primarily include HCM patients,26 while others have shown prevention of recurrent TWOS by exercise QRS optimization in 87.5% of patients.23 Five patients in our study underwent routine postimplant QRS template optimization and none of these patients experienced IAS because of TWOS or inappropriate discrimination (1 had an IAS for rapidly conducted AF in the shock zone). In addition, exercise QRS optimization was used in 2 patients after IAS. The role of postimplant exercise optimization merits further investigation.

Appropriate device therapy

The incidence of an appropriate S-ICD intervention was surprisingly low in our study, with the only 2 appropriate shocks in the whole cohort occurring in the 7 patients implanted for secondary prevention. On the basis of the calculated European HCM Risk-SCD score (mean 5.7% 5-year risk), we anticipated seeing ~3 appropriate shocks in our cohort of 81 patients implanted for primary prevention, although none occurred. To further investigate this low appropriate shock rate, we determined that the majority of S-ICDs in our study were “indicated,” as 79 of 81 patients met at least 1 of the 3 established HCM primary prevention criteria.

Many prior studies that defined existing SCD risk factors in HCM ICD guidelines used appropriate ICD therapies as a surrogate end point for SCD.14 Thus, SCD risks may be overestimated in older studies in which ICDs were traditionally programmed with shorter delays and lower rate thresholds. The typically higher heart rate cutoffs (mean shock zone 241 beats/min in our study) and longer charge times of S-ICDs may prevent seemingly “appropriate” therapies that would have previously been delivered for VT episodes that would have otherwise self-terminated. Our lower-than-expected appropriate shock rate, particularly in our patients implanted for primary prevention, warrants further investigation, as does the lack of agreement between the 3 established ICD criteria.

Study limitations

While we report on a relatively large cohort of patients with HCM with an S-ICD, the incidence of IAS in our study was low and limited our statistical power to detect independent IAS predictors. The duration of follow-up in our study, while longer than most other studies of IAS,6–8 was shorter than most studies that assess SCD in HCM.14,16 Retrospective data collection may limit completeness of data. The lack of a separate cohort of HCM patients with transvenous ICDs limits comparison between device types for both IAS and appropriate therapies. Lastly, we collected data from 4 high-volume geographically diverse HCM centers, and this may not be representative of community S-ICD utilization and experience.

Conclusion

In a multicenter international HCM S-ICD cohort, 5.7% of patients received IAS (3.8 IAS episodes per 100 patient-years), which is lower than previously reported. The ECG R-wave amplitude was independently associated with an increased risk of IAS, whereas TWIs were protective. IAS were often due to sinus tachycardia with and without TWOS in the setting of exercise. Particularly for patients with tall R waves, we recommend preimplantation S-ICD screening with exercise and considering postimplantation exercise-based QRS template optimization. The incidence of appropriate shocks was lower than expected, as there were none in 81 patients implanted for primary prevention, 97% of whom met the established HCM ICD criteria, which may warrant reassessment.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Dr Olivotto was supported by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme (grant no. 777204), the Italian Ministry of Health (RF-2013-02356787), and the Ente Cassa di Risparmio di Firenze (2016).

Footnotes

Appendix Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2020.02.008.

References

- 1.Ho CY, Day SM, Ashley EA, et al. Genotype and lifetime burden of disease in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy insights from the sarcomeric human cardiomyopathy registry (SHaRe). Circulation 2018;138:1387–1398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Al-Khatib SM, Stevenson WG, Ackerman MJ, et al. 2017 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death: executive summary. Heart Rhythm 2018; 15:e190–e252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zeitler EP, Friedman DJ, Loring Z, et al. Complications involving the subcutaneous implantable cardioverter-defibrillator: lessons learned from MAUDE. Heart Rhythm 2020;17:447–454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maurizi N, Olivotto I, Olde Nordkamp LRA, et al. Prevalence of subcutaneous implantable cardioverter-defibrillator candidacy based on template ECG screening in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Heart Rhythm 2016; 13:457–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Srinivasan NT, Patel KH, Qamar K, et al. Disease severity and exercise testing reduce subcutaneous implantable cardioverter-defibrillator left sternal ECG screening success in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2017;10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weinstock J, Bader YH, Maron MS, Rowin EJ, Link MS. Subcutaneous implantable cardioverter defibrillator in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: an initial experience. J Am Heart Assoc 2016;5:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olde Nordkamp LRA, Brouwer TF, Barr C, et al. Inappropriate shocks in the subcutaneous ICD: incidence, predictors and management. Int J Cardiol 2015; 195:126–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lambiase PD, Gold MR, Hood M, et al. Evaluation of subcutaneous ICD early performance in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy from the pooled EFFORTLESS and IDE cohorts. Heart Rhythm 2016;13:1066–1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Theuns DAMJ, Brouwer TF, Jones PW, et al. Prospective blinded evaluation of a novel sensing methodology designed to reduce inappropriate shocks by the subcutaneous implantable cardioverter-defibrillator. Heart Rhythm 2018; 15:1515–1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Knops RE, Olde Nordkamp LRA, De Groot JR, Wilde AAM. Two-incision technique for implantation of the subcutaneous implantable cardioverter-defibrillator. Heart Rhythm 2013;10:1240–1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kleijn S, Van Der Veldt A. An entirely subcutaneous implantable cardioverter-defibrillator. N Engl J Med 2010;363:1577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Firth D. Amendments and corrections: bias reduction of maximum likelihood estimates. Biometrika 1995;82:667. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gersh BJ, Maron BJ, Bonow RO, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: executive summary. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2011;142:1303–1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O’Mahony C, Jichi F, Pavlou M, et al. A novel clinical risk prediction model for sudden cardiac death in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM Risk-SCD). Eur Heart J 2014;35:2010–2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O’Mahony C, Jichi F, Ommen SR, et al. International external validation study of the 2014 European Society of Cardiology Guidelines on Sudden Cardiac Death Prevention in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy (EVIDENCE-HCM). Circulation 2018;137:1015–1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maron MS, Rowin EJ, Wessler BS, et al. Enhanced American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association strategy for prevention of sudden cardiac death in high-risk patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. JAMA Cardiol 2019;02111:1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weiss R, Knight BP, Gold MR, et al. Safety and efficacy of a totally subcutaneous implantable-cardioverter defibrillator. Circulation 2013;128:944–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brouwer TF, Yilmaz D, Lindeboom R, et al. Long-term clinical outcomes of sub-cutaneous versus transvenous implantable defibrillator therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;68:2047–2055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boersma L, Barr C, Knops R, et al. Implant and midterm outcomes of the subcutaneous implantable cardioverter-defibrillator registry: the EFFORTLESS study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;70:830–841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Auricchio A, Schloss EJ, Kurita T, et al. Low inappropriate shock rates in patients with single- and dual/triple-chamber implantable cardioverter-defibrillators using a novel suite of detection algorithms: PainFree SST trial primary results. Heart Rhythm 2015;12:926–936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moss AJ, Zareba W, Hall WJ, et al. Prophylactic implantation of a defibrillator in patients with myocardial infarction and reduced ejection fraction. N Engl J Med 2002;346:6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moss AJ, Schuger C, Beck CA, et al. Reduction in inappropriate therapy and mortality through ICD programming. N Engl J Med 2012;367:2275–2283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kooiman KM, Knops RE, Olde Nordkamp L, Wilde AAM, De Groot JR. Inappropriate subcutaneous implantable cardioverter-defibrillator shocks due to T-wave oversensing can be prevented: implications for management. Heart Rhythm 2014;11:426–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Batul SA, Yang F, Wats K, Shrestha S, Greenberg YJ. Inappropriate subcutaneous implantable cardioverter-defibrillator therapy due to R-wave amplitude variation: another challenge in device management. HeartRhythm Case Rep 2017; 3:78–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Francia P, Adduci C, Palano F, et al. Eligibility for the subcutaneous implantable cardioverter-defibrillator in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2015;26:893–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Afzal MR, Evenson C, Badin A, et al. Role of exercise electrocardiogram to screen for T-wave oversensing after implantation of subcutaneous implantable cardioverter-defibrillator. Heart Rhythm 2017;14:1436–1439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.