Abstract

Objectives

Individuals with disabilities experience significant health care disparities due to a multitude of barriers to effective care, which include a lack of adequate physician training on this topic and negative attitudes of physicians. This results in disparities through inadequate physical examination and diagnostic testing, withholding or inferior treatment, and neglecting preventative care. While much has been published about disability education in undergraduate medical education, little is known about the current state of disability education in emergency medicine (EM) residency programs.

Methods

In 2019, a total of 237 EM residency program directors (PDs) in the United States were surveyed about the actual and desired number of hours of disability health instruction, perceived barriers to disability health education, prevalence of residents and faculty with disabilities, and confidence in providing accommodations to residents with disabilities.

Results

A total of 104 surveys were completed (104/237, 43.9% response rate); 43% of respondents included disability‐specific content in their residency curricula for an average of 1.5 total hours annually, in contrast to average desired hours of 4.16 hours. Reported barriers to disability health education included lack of time and lack of faculty expertise. A minority of residency programs have faculty members (13.5%) or residents (26%) with disabilities. The prevalence of EM residents with disabilities was 4.02%. Programs with residents with disabilities reported more hours devoted to disability curricula (5 hours vs 1.54 hours, p = 0.017) and increased confidence in providing workplace accommodations for certain disabilities including mobility disability (p = 0.002), chronic health conditions (p = 0.022), and psychological disabilities (p = 0.018).

Conclusions

A minority of EM PDs in our study included disability health content in their residency curricula. The presence of faculty and residents with disabilities is associated with positive effects on training programs, including a greater number of hours devoted to disability health education and greater confidence in accommodating learners with disabilities. To reduce health care disparities for patients with disabilities, we recommend that a dedicated disability health curriculum be integrated into all aspects of the EM residency curriculum, including lectures, journal clubs, and simulations and include direct interaction with individuals with disabilities. We further recommend that disability be recognized as an aspect of diversity when hiring faculty and recruiting residents to EM programs, to address this training gap and to promote a diverse and inclusive learning environment.

In 2018, over 61 million Americans (26%) reported having a disability1 in cognition, mobility, vision, hearing, independent living, or self‐care; this prevalence is likely underreported due to exclusions of individuals with disabilities residing in nursing homes or adult living facilities. 1 Individuals with disabilities experience significant health disparities resulting from structural and socioeconomic barriers to health care. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 33% of Americans with a disability do not have a primary care provider, and 25% did not have a routine health examination in the past year. 1 , 2 They are also more likely to experience violence or sexual assault and have increased rates of chronic illness and are more likely to develop chronic illness at an early age. 3 Individuals with disabilities face difficulties with coordination among providers, challenges with insurance coverage, and report higher levels of unmet health care needs. As a result, many individuals with disabilities avoid medical treatment and report difficulty finding providers with whom they are comfortable. 4

The Institute of Medicine, Office of the U.S. Surgeon General, National Council of Disability, and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services have each identified deficiencies in the knowledge and attitudes of health care providers as a significant barrier to the care of patients with disabilities. 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 These organizations emphasize the need for improved physician education on disability health through disability health curricula, yet many U.S. medical schools lack a dedicated curriculum. 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 This lack of undergraduate medical education leaves students ill‐prepared to care for patients with disabilities as they enter residency and is further perpetuated by the lack of established disability curricula within graduate medical education programs. 11 , 13 , 14

Adults with disabilities utilize the Emergency Department (ED) more frequently than the general population, accounting for as many as 40% of annual ED visits, 15 and are twice as likely to require emergency services. 16 Given the frequency with which Emergency Medicine (EM) physicians will encounter patients with disabilities, it is imperative to teach EM residents about disability topics in residency training programs. The Accreditation Council on Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Program Requirements for Emergency Medicine requires that residents demonstrate competence in respect and responsiveness to diverse patient populations, including but not limited to diversity in gender, age, culture, race, religion, disabilities, national origin, socioeconomic status, and sexual orientation as part of their core requirements. However, the Residency Review Committee (RRC) for Emergency Medicine does not require education and training on care for patients with disabilities. 14 , 17 Moreover, when the Council of EM Residency Directors in Emergency Medicine (CORD) previously examined residency curricula specific to the care of underserved minorities, they did not include patients with disabilities in their report. 18 Recent studies emphasize the importance of and need for comprehensive EM resident education regarding the care of patients with disabilities. 14

Therefore, the objectives of this study are to:

Identify the quantity and type of disability health education among EM residency programs in the United States.

Examine the proportion and prevalence of faculty and residents with disabilities in EM programs and the association between their presence and disability health education.

Assess programs’ confidence in providing accommodations to EM residents with disabilities.

METHODS

Study Design and Population

A cross‐sectional study design was used to survey EM residency program directors (PDs) in the United States from September to October 2019. Participants met inclusion criteria if they were a PD in one of the 237 ACGME‐accredited EM programs at the time of data collection. 19 Other program leadership such as associate/assistant directors were excluded to limit responses to one per residency program. The study was approved by the institutional review board (IRB) of Stanford University (IRB‐51240).

Survey Content and Administration

The instrument was designed based on a survey used to explore the prevalence of LGBT health content taught in EM residency programs. 20 A group of EM residency faculty identified items most relevant to training residents about patients with disabilities. Our survey was piloted by eight assistant/associate current or former EM residency directors at three university‐based programs. We used cognitive interviewing techniques during the piloting process, and feedback was used to modify questions, maximize participation, improve clarity, and reduce response latency and bias. 21 The final survey was reviewed by a study author (SSS) with measurement expertise and can be found in Data Supplement S1 (available as supporting information in the online version of this paper, which is available at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/aet2.10511/full).

The survey was created in Qualtrics (Provo, UT) and distributed by e‐mail to eligible participants using an anonymous link on September 11, 2019. E‐mails were obtained through review of online residency directories and program websites and direct calls to program coordinators. The e‐mail distribution list was maintained in a database that was checked for accuracy throughout the study period. Seven reminder e‐mails were sent over the course of 4 weeks and a single general request for participation was posted to both the CORD community website 22 and the SAEM ADIEM community. 23 . The survey was closed on November 3, 2019.

Outcomes Measures

The primary outcome was to determine the prevalence of disability education among EM residency programs by examining the percentage of programs that include disability content and the number of hours of disability education presented in the past academic year. This included methods of instruction, topics covered, perceived barriers to disability education, and the number of hours of disability content desired by respondents for future curriculum cycles. A secondary outcome was to determine the current prevalence of EM faculty members and residents with disabilities as well as residency programs’ perceived confidence in providing workplace accommodations to individuals with disabilities.

Data Analysis

Anonymous survey responses were aggregated in Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA) and analyzed using SPSS Statistics Version 25 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). Frequency distributions for each item were performed. For continuous data, we used two‐sided t‐test and two‐sided Welch’s t‐test to compare the means. For three or more groups, we used one‐way ANOVA and Kruskal‐Wallis to compare the means. For discrete data, we used a two‐sided Mann Whitney U‐test to compare ordinal data from two groups. For the result to be significant, alpha was set to 0.05. For analyzing the confidence of programs for providing accommodations, we analyzed the data overall to look at differences between different disabilities and then performed a subgroup analysis with the presence of faculty or residents with disabilities in EM programs.

RESULTS

A total of 104 surveys were completed (104/237, 43.9% response rate). The majority of respondents were from university‐based programs, in metropolitan centers greater than 1 million people, and all regions of the United States were adequately represented. Program demographics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Residency Program Demographics

| Program Characteristics | Frequency (N = 104), No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Local metropolitan population | |

| <100,000 | 9 (8.65) |

| 100,000–‐250,000 | 23 (22.11) |

| 250,000–1 million | 30 (28.84) |

| > 1 million | 42 (40.38) |

| Faculty employer type* | |

| University hospital | 61 (58.65) |

| Public hospital | 23 (22.11) |

| Community hospital | 40 (38.46) |

| Military hospital | 2 (1.92) |

| Program location | |

| Midwest | 28 (26.92) |

| Northeast | 31 (29.81) |

| South | 25 (24.04) |

| West | 20 (19.23) |

*Duplicated responses; does not add up to 100%.

Characteristics and Current State of Disability Content in ED Residency Curriculum

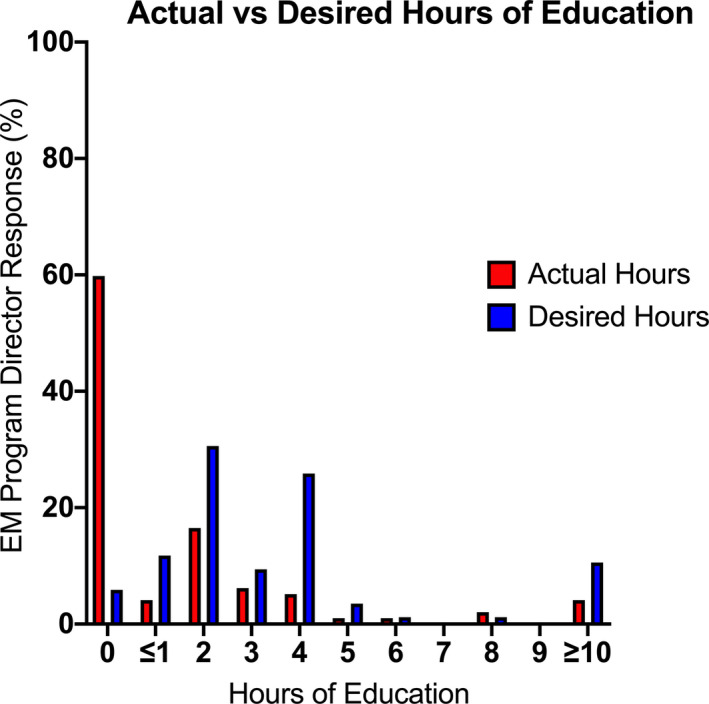

Disability‐specific content was taught at a minority of EM programs (43%), with 46% of those programs incorporating disability topics into general teaching. Participants reported a mean (±SD) of 1.5 (±3.05) hours of disability education in the previous year’s curriculum (median = 0 hours, interquartile range [IQR] = 0‐2 hours, range = 0–20 hours; Figure 1). Most respondents desire more hours of disability education in their curricula than what is currently being taught. The desired time dedicated to disability education averaged 4.16 hours (SD = ±5.45 hours, median = 3 hours, IQR = 2–4 hours, range 0–40 hours; Figure 1). A small minority of respondents (5%) felt that no curriculum time should be devoted to spent on disability health. There were no reported differences in curriculum design characteristics, mean content hours taught last year, desired hours in future years, or barriers to teaching when examining the following residency program demographics: metropolitan size, type of program and location.

Figure 1.

Comparison of the distribution of actual versus desired hours of disability health topics by reported frequency. Actual hours (red), mean ± SD = 1.5 ± 3.05 hours, median = 0 hours, IQR = 0–2 hours, range 0–20 hours, n = 97. Desired hours (blue), mean ± 5.45 hours, median = 2 hours, IQR = 2–4 hours, range = 0–40 hours, n = 85).

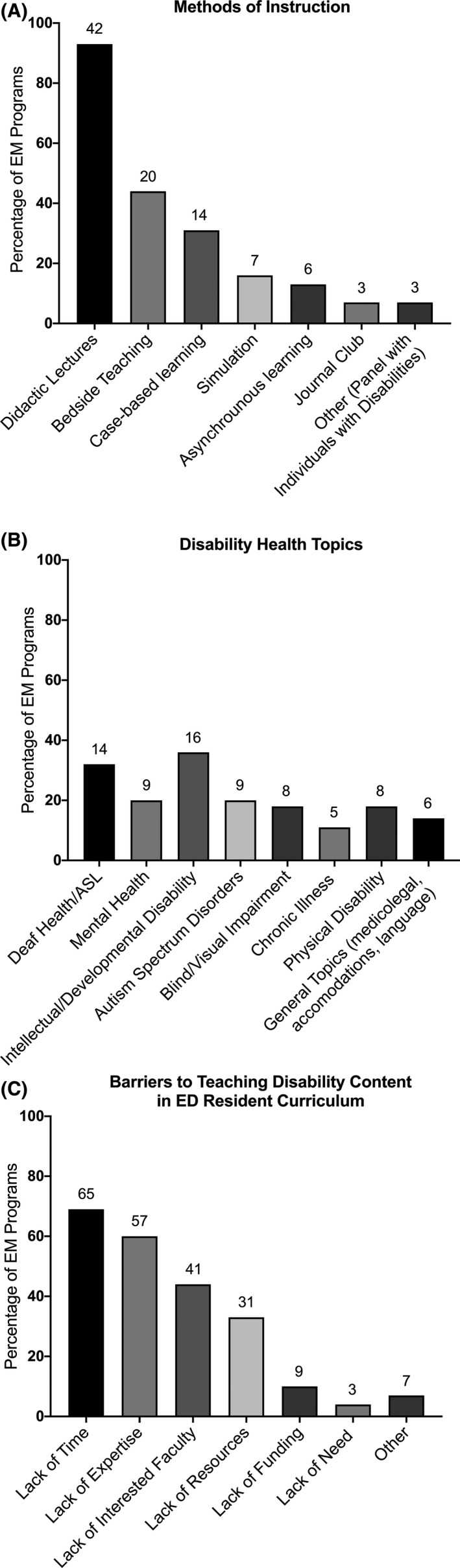

Of those programs that teach disability health, the most common topics included “care of patients who are deaf or hard of hearing” (32%) and “care of individuals with developmental delay and intellectual disability” (36%; Figure 2A). The most common instructional method was didactic lecture (93%; Figure 2B). In open‐text responses, a few programs reported utilizing panels of individuals with disabilities and family members. Commonly cited barriers to teaching disability content in EM residency programs included “lack of time” (69%) and “lack of expertise” (60%; Figure 2C). Regarding a perceived lack of time, one open‐text response added context, “some [content] needs to be taught in med[ical] school, some needs to be independent, and for the time we have during residency training we have to be mindful of the limitations.” Only 4% of respondents cited lack of need as a barrier to teaching.

Figure 2.

EM residency disability curriculum characteristics. (A) Methods of instruction (n=45). (B) Disability health topics (n = 44). (C) Barriers to teaching (n = 94).

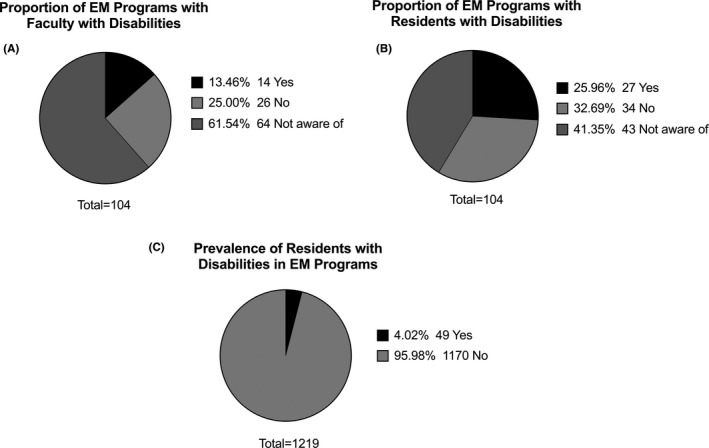

Proportion and Prevalence of Faculty and Residents With Disabilities in EM Programs and Its Effects on Disability Education

In this study, 13.5% of PDs reported having a faculty member with a disability (see Figure 3A), and 26% reported having a resident with a disability (Figure 3B) in their program. The majority of programs reported a lack of faculty and residents with known disabilities, with a large number of programs selecting “Not aware of” (Figures 3A and 3B). To determine the prevalence of EM residents with disabilities, we asked PDs about the number of residents with disabilities in their program and divided it by the total number of residents in those programs. Our estimate of the percentage of EM residents with disabilities based on the data reported by PDs in this study was 4.02% (49/1,219 residents; Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

Disability demographics of faculty members and residents with disabilities in EM programs. (A) Proportion of EM programs with faculty with disabilities. (B) Proportion of EM programs with residents with disabilities. (C) Prevalence of EM residents with disabilities.

The presence of faculty members with disabilities was not significantly associated with the prevalence of disability education; however, the presence of residents with disabilities was associated with an increased number of hours of disability education (5 hours vs 1.54 hours, p = 0.017, Welch’s t‐test). Programs with faculty and/or residents with disabilities did not have a significant difference in desired hours of education.

Providing Accommodations for EM Residents With Disabilities

Almost all respondents (98%) stated that their programs offered accommodations to residents who identify as having a disability, and most respondents (87%) knew the individuals responsible for arranging workplace accommodations if requested. However, only 23% of PDs routinely asked residents who match at their program whether they need accommodations. Most programs (86.4%) stated that their institution would be supportive of accommodating a resident with a disability, with only two (1.94%) programs stating their institutions would not be supportive.

We evaluated whether programs were confident at providing accommodations by examining the median of the Likert scores (1 = “not confident at all” to 5 = “very confident”) for each category of disability. Overall, programs were moderately confident in providing accommodations for chronic health conditions, ADHD, and learning disabilities (median = 4). Programs were somewhat confident with providing accommodations for psychological disabilities, deaf and hard of hearing and mobility disabilities (median = 3), and the slightly confident with visual disabilities (median = 2).

Median values for the presence of a faculty member with a disability was only associated with significantly higher confidence in accommodating a resident who is blind (3 vs 2, p = 0.009; Table 2). Medians for the presence of a resident with a disability led to significantly higher confidence in providing accommodations for the following disabilities: mobility disability (3 vs 2, p = 0.002), chronic health conditions (p = 0.022), and psychological disabilities (4 vs 3, p = 0.018; Table 2). The implications of these findings suggest that having a resident with a disability, rather than a faculty member with a disability, leads to greater confidence in providing accommodations for residents.

Table 2.

Reported Median Values for the Association Between the Presence of Faculty and Residents with Disabilities and EM Program Confidence in Providing Accommodations

| Row Scores (%) | ADHD | Learning Disability | Psychological Disability | Deaf and Hard of Hearing | Visual Impairment | Mobility Disability | Chronic Health Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Faculty with disabilities | |||||||

| Yes (n = 14, 13.5%) | 4 | 3.5 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3.5 | 4 |

| No (n = 90, 86.5%) | 3.5 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Mann‐Whitney U‐test p‐value | 0.652 | 0.854 | 0.181 | 0.161 | 0.009 | 0.077 | 0.077 |

| Range | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Residents with disabilities | |||||||

| Yes (n = 27, 26%) | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 4 |

| No (n = 77, 76%) | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Mann‐Whitney U‐test p‐value | 0.085 | 0.125 | 0.018 | 0.089 | 0.280 | 0.002 | 0.022 |

| Range | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

5‐point Likert scale from 1 (not confident at all) to 5 (very confident).

DISCUSSION

Our study found that structured disability health curricula are substantially lacking in EM residency education, despite a call to action by various national organizations. 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 The majority of programs had no disability content, and when taught, there was on average only 90 minutes of instruction per year. This is problematic as individuals with disabilities are frequent users of the ED 15 , 16 and experience significant health care disparities. 3 Many EM PDs desired a greater number of hours dedicated to disability health but noted significant barriers to developing and implementing disability curricula, including time constraints and a lack of expertise and faculty champions.

Lack of time was noted to be the biggest barrier to implementing disability education in the curriculum. Education on caring for those with disabilities fits naturally into EM education as part of a larger diversity and inclusion curriculum, with the amount of time dedicated to the topic varying based on program preferences and needs. Specifically, we suggest that a disability health curriculum be integrated into all aspects of the EM residency curriculum, including lectures, journal clubs, and simulations 24 , 25 , 26 and should also include direct interaction with individuals with disabilities. 27 , 28 In this study the presence of residents with disabilities was statistically associated with more hours of content dedicated to teaching about disability in the curriculum, possibly due to faculty/resident advocacy or a more inclusive program environment. This result suggests that diverse hiring practices and recruitment of learners with disabilities could have a positive effect on disability health education in EM residencies and could help with barriers such as lack of expertise and lack of interested faculty. There is currently no standardization of topics that should be covered related to disability health in an EM residency curriculum. When designing disability health curricula, we recommend incorporating the biopsychosocial model of the International Classification Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) 29 and the social model of disability. 30 The core competencies on disability for health care provide a framework that may aid in creating a curriculum, 31 along with core EPAs adapted for disability for medical schools. 11 Resources such as these could be useful to modify ACGME milestones, as recently described in a call to action paper. 14

Limited information exists about the prevalence of physicians with disabilities throughout all stages of their career. Available data suggest that the prevalence of medical students with disabilities has been increasing from less than 2% prior to 2016 32 , 33 to 2.7% in 2016 34 to 4.6% in 2019. 35 Looking at all physicians, a report from 2005 noted that 2% to 10% of physicians had disabilities, 36 , 37 but data since that time is lacking, representing a critical gap in our understanding of the physician workforce and emphasizing the need for future study. 38 The prevalence of disability among residents is poorly documented. In EM there is one prior study, a 2002 survey of EM PDs that found that 1.3% of EM residents had a documented disability. 39 In comparison, our study demonstrates an increase over the past two decades, with 4.02% (49/1,219) of residents in EM programs reported as having a disability. Given the stigma surrounding disabilities as well as the barriers to disclosing a disability, it is plausible that these numbers still underrepresent the true number of residents with disabilities in EM programs. Factors that may have contributed to the increase since 2002 include a more inclusive definition of disability, an increased awareness of the importance of diversifying our workforce, and recognition of inclusion in medicine as a factor in providing more equitable care. 40 , 41 , 42

To promote a more inclusive environment, identified best practices include proactively asking residents about disabilities and increasing transparency in policies, including having a specialized disability expert help create accommodation processes. 43 Interestingly, in this study the majority of PDs reported both offering accommodations and knowing who provides those accommodations, yet most (77%) are not proactive in asking residents about whether they need accommodations. Implementing this best practice in EM residency programs would be an effective first step to creating a more inclusive training environment for all learners.

Programs reported having more confidence providing accommodations for ADHD, learning disabilities, and chronic health conditions, which may be due to having more experience with these disabilities, because they are more common in the medical student population. 35 Psychological disabilities are also highly prevalent, but programs reported having less confidence, potentially due to stigma surrounding mental health. Given the rarity of disabilities involving mobility, hearing, and vision, 35 it is understandable that most programs would lack confidence in being able to provide accommodations. Unfortunately, there is little in the literature to guide programs in successfully providing accommodations for residents with disabilities in all specialties, including EM. This represents an opportunity for future research to identify best practices and to share with the community effective accommodations within EM training programs. In this study the presence of faculty members and residents with disabilities was associated with significantly increased self‐reported comfort with less prevalent disabilities, possibly due to specific experience with those disabilities. This emphasizes the value of including residents and faculty members with disabilities in EM residency programs as well as the need to develop general best practice guidelines that can be tailored to individuals. Published case studies on providing successful accommodations for students in the ED 44 may serve as a starting point for enacting accommodations for residents. Additionally, providing accommodations for faculty members or residents with disabilities may improve patient care to individuals with similar disabilities due to creating more accessible and inclusive environments. 45

LIMITATIONS

The collected data were self‐reported and thus subject to response bias. For example, the survey was sent only to PDs, and they may defer curriculum responsibilities to other residency leadership, thus limiting the total number of responses. Because it was an anonymous survey, we had no mechanism to eliminate duplicate responses. Our survey asked PDs for knowledge of faculty and residents with disabilities, but it is difficult to ascertain the actual number. The number could be underreported due to differing institutional definitions of disability, attitudes regarding diversity and inclusion, and the reluctance of residents or faculty to disclose due to the stigma surrounding disability. Although our response rate was above the reported mean survey response rate for research studies in the United States, we received responses from less than half of all EM residencies which may have led to underreporting. 46 Given that less than half of all EM programs responded, our responses may not be representative of all EM residency programs, which may limit the generalizability of our results.

CONCLUSIONS

This is the first study to examine the details of disability health education in emergency medicine residency programs. The majority of emergency medicine residency programs in this study lack formal training, yet program directors desire more time dedicated to disability education than what is currently provided. The presence of faculty and residents with disabilities is associated with positive effects on training programs, including a greater number of hours devoted to disability health education and greater confidence in accommodating learners with disabilities. We strongly recommend that a disability health curriculum be integrated into all aspects of the emergency medicine residency curriculum, including lectures, journal clubs, and simulations to improve confidence and skill in caring for this population. Direct interaction with individuals with disabilities and their participation in curriculum reform is essential. Further research and curriculum development is required to empower emergency medicine residency programs to address this training gap, identify best practices, test curricular interventions, and ensure an equitable and inclusive learning environment.

Supporting information

Data Supplement S1. Study survey instrument.

AEM Education and Training 2021;5:1–9

The authors have no relevant financial information or potential conflicts to disclose.

Author contributions: RWS—study concept and design, acquisition of the data, analysis and interpretation of the data, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; SSS—study concept and design, acquisition of the data, analysis and interpretation of the data, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, statistical expertise. MAG—study concept and design, acquisition of the data, analysis and interpretation of the data, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; JMR—study concept and design, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; AB—study concept and design, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; CMP—study concept and design, acquisition of the data, analysis and interpretation of the data, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Supervising Editor: Daniel P. Runde, MD, MME.

References

- 1. Okoro CA, Hollis ND, Cyrus AC, Griffin‐Blake S. Prevalence of disabilities and health care access by disability status and type among adults ‐ United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018;67:882–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Disability and Health Data System (DHDS) | CDC. 2020. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/disabilityandhealth/dhds/index.html. Accessed Apr 6, 2020.

- 3. Krahn GL, Walker DK, Correa‐De‐Araujo R. Persons with disabilities as an unrecognized health disparity population. Am J Public Health 2015;105:S198–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. de Vries McClintock HF, Barg FK, Katz SP, et al. Health care experiences and perceptions among people with and without disabilities. Disabil Health J 2016;9:74–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Institute of Medicine Committee on Disability in America . The Future of Disability in America. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Office of the Surgeon General, Office on Disability . The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Improve the Health and Wellness of Persons with Disabilities. Rockville, MD: Office of the Surgeon General, 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Healthy People ‐ Healthy People 2020. 2019. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/healthy_people/hp2020.htm. Accessed Mar 3, 2020.

- 8. Santoro JD, Yedla M, Lazzareschi DV, Whitgob EE. Disability in U. S. medical education: disparities, programmes and future directions. Health Educ J 2017;76:753–9. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Holder M, Waldman HB, Hood H. Preparing health professionals to provide care to individuals with disabilities. Int J Oral Sci 2009;1:66–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Seidel E, Crowe S. The state of disability awareness in American medical schools. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2017;96:673–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ankam NS, Bosques G, Sauter C, et al. Competency‐based curriculum development to meet the needs of people with disabilities: a call to action. Acad Med 2019;94:781–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Curriculum Inventory|AAMC . AAMC. Available at: https://www.aamc.org/what‐we‐do/mission‐areas/medical‐education/curriculum‐inventory. Accessed Apr 7, 2020.

- 13. Iezzoni LI, Long‐Bellil LM. Training physicians about caring for persons with disabilities: “Nothing about us without us!” Disabil Health J 2012;5:136–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rotoli J, Backster A, Sapp RW, et al Emergency medicine resident education on caring for patients with disabilities: a call to action. AEM Educ Train 2020;59:1456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rasch EK, Gulley SP, Chan L. Use of emergency departments among working age adults with disabilities: a problem of access and service needs. Health Serv Res 2013;48:1334–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kim AM, Lee JY, Kim J. Emergency department utilization among people with disabilities in Korea. Disabil Health J 2018;11:598–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. ACGME Common Program Requirements.Chicago, IL: Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, 2017:9–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bowman SH, Moreno‐Walton L, Ezenkwele UA, Heron SL. Diversity in emergency medicine education: expanding the horizon: diversity in EM education. Acad Emerg Med 2011;18:S104–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Stobart‐Gallagher M, Smith L, Giordano J, et al. Recommendations from the Council of Emergency Medicine Residency Directors: osteopathic applicants. West J Emerg Med 2019;20:111–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Moll J, Krieger P, Moreno‐Walton L, et al. The prevalence of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender health education and training in emergency medicine residency programs: what do we know? Acad Emerg Med 2014;21:608–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Willis GB, Artino AR Jr. What do our respondents think we’re asking? Using cognitive interviewing to improve medical education surveys. J Grad Med Educ 2013;5:353–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Home – Council of Residency Directors in Emergency Medicine. 2018. Available at: https://community.cordem.org/home. Accessed Apr 23, 2020.

- 23. ADIEM . 2020. Available at: https://www.saem.org/adiem. Accessed Apr 23, 2020.

- 24. Long‐Bellil LM, Robey KL, Graham CL et al. Teaching medical students about disability: the use of standardized patients. Acad Med 2011;86:1163–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Burgstahler S, Doe T.Disability‐related Simulations: If, When, and How to Use Them in Professional Development. 2004. Available at: https://www.rdsjournal.org/index.php/journal/article/view/385. Accessed Apr 6, 2020.

- 26. Barney KW. Disability simulations: using the social model of disability to update an experiential educational practice. SCHOLE: a journal of leisure studies and recreation. Education 2012;27:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Minihan PM, Bradshaw YS, Long LM, et al. Teaching about disability: involving patients with disabilities as medical educators. Disabil Stud Q 2004. Available at: https://dsq‐sds.org/article/view/883/1058. Accessed Apr 6, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Symons AB, Morley CP, McGuigan D, Akl EA. A curriculum on care for people with disabilities: effects on medical student self‐reported attitudes and comfort level. Disabil Health J 2014;7:88–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. ICF: International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: Geneva: World Health Organization, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Goering S. Rethinking disability: the social model of disability and chronic disease. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med 2015;8:134–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Core Competencies on Disability for Health Care Education. 2007. Available at: https://nisonger.osu.edu/wp‐content/uploads/2019/08/post‐consensus‐Core‐Competencies‐on‐Disability_8.5.19.pdf. Accessed Feb 15, 2020.

- 32. Eickmeyer SM, Do KD, Kirschner KL, Curry RH. North American medical schools’ experience with and approaches to the needs of students with physical and sensory disabilities. Acad Med 2012;87:567–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Searcy CA, Dowd KW, Hughes MG, Baldwin S, Pigg T. Association of MCAT scores obtained with standard vs extra administration time with medical school admission, medical student performance, and time to graduation. JAMA 2015;313:2253–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Meeks LM, Herzer KR. Prevalence of self‐disclosed disability among medical students in US allopathic medical schools. JAMA 2016;316:2271–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Meeks LM, Case B, Herzer K, Plegue M, Swenor BK. Change in prevalence of disabilities and accommodation practices among US medical schools, 2016 vs 2019. JAMA 2019;322:2022–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. DeLisa JA, Thomas P. Physicians with disabilities and the physician workforce: a need to reassess our policies. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2005;84:5–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Corbet B, Madorsky JG. Physicians with disabilities. West J Med 1991;154:514–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. DeLisa JA, Lindenthal JJ. Learning from physicians with disabilities and their patients. AMA J Ethics 2016;18:1003–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Takakuwa KM, Ernst AA, Weiss SJ. Residents with disabilities: a national survey of directors of emergency medicine residency programs. South Med J 2002;95:436–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Martin ML, Heron SL, Moreno‐Walton L, Jones AW, eds. Diversity and Inclusion in Quality Patient Care. Cham: Springer, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Cohen JJ, Gabriel BA, Terrell C. The case for diversity in the health care workforce. Health Aff 2002;21:90–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Schwarz CM, Zetkulic M. You belong in the room: addressing the underrepresentation of physicians with physical disabilities. Acad Med 2019;94:17–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Meeks LM, Jain NR, Moreland C, Taylor N, Brookman JC, Fitzsimons M. Realizing a diverse and inclusive workforce: equal access for residents with disabilities. J Grad Med Educ 2019;11:498–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Meeks LM, Engelman A, Booth A, Argenyi M. Deaf and hard‐of‐hearing learners in emergency medicine. West J Emerg Med 2018;19:1014–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Iezzoni LI. Why increasing numbers of physicians with disability could improve care for patients with disability. AMA J Ethics 2016;18:1041–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sheehan KB. E‐mail survey response rates: a review. J Comput Mediat Commun 2001;6(2). Available at: https://academic‐oup‐com.laneproxy.stanford.edu/jcmc/article/6/2/JCMC621/4584224. Accessed Apr 3, 2020. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Supplement S1. Study survey instrument.