Summary:

Published series on COVID-19 support the notion that patients with cancer are a particularly vulnerable population. There is a confluence of risk factors between cancer and COVID-19, and cancer care and treatments increase exposure to the virus and may dampen natural immune responses. The available evidence supports the conclusion that patients with cancer, in particular with hematologic malignancies, should be considered among the very high-risk groups for priority COVID-19 vaccination.

At this time of limited supply of the highly effective COVID-19 vaccines, it is important to gather the evidence on the risk of complications and death resultant from a diagnosis of COVID-19 infection in patients with cancer. After reviewing 28 publications, many of which included relevant information on fatality rates of patients with cancer who developed COVID-19 (1–28), we conclude that patients with an active cancer should be considered for priority access to COVID-19 vaccination, along with other particularly vulnerable populations with risk factors for adverse outcomes with COVID-19. This recommendation is consistent with the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) within the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The ACIP considered multiple groups to recommend for early access to a limited COVID-19 vaccine supply and concluded that patients with cancer are at a higher risk for severe COVID-19 and should be one of the groups considered for early COVID-19 vaccination (29). Given that there are nearly 17 million people living with a history of cancer in the United States alone, it is critical to understand whether these individuals are at a higher risk to contract SARS-CoV-2 and to experience severe outcomes from COVID-19.

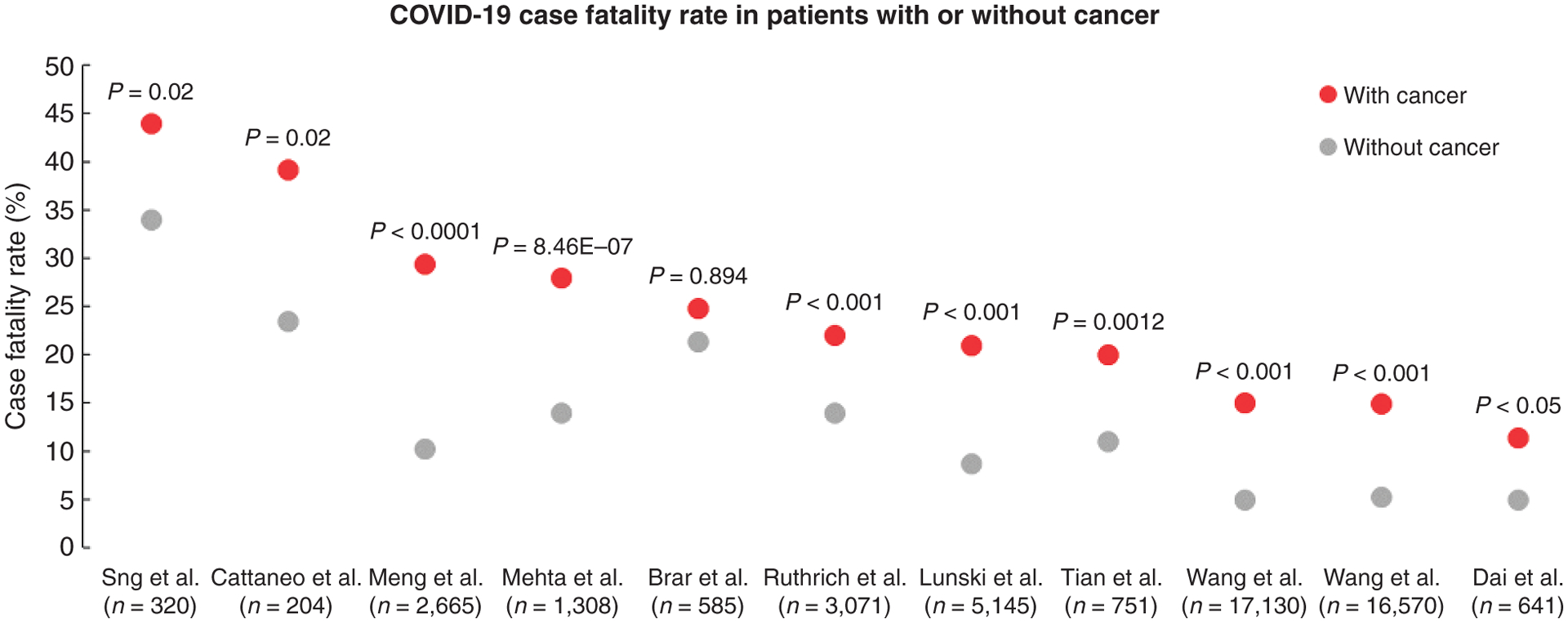

Our review of the available literature to provide the scientific support for early access during the time of limited supplies of COVID-19 vaccines was based on a literature search for peer-reviewed publications using PubMed. We selected articles that reported either case fatality rates (CFR) or the mortality risks among SARS-CoV-2–infected patients with cancer. We excluded articles with cohort sizes of fewer than 90 patients. Of 28 articles selected, 16 included one or more control cohorts, with 13 studies reporting on direct comparisons of outcomes from SARS-CoV-2–infected patients with cancer with those without cancer (Supplementary Table S1; refs. 1–13). Of these 13 studies, 11 reported CFRs among patients with cancer with a SARS-CoV-2 infection. Ten out of the 11 studies reported a higher CFR in patients with a SARS-CoV2 infection and cancer compared with patients with infection but no cancer (Fig. 1). Examples from studies from different parts of the world include a series from Wuhan, China, with CFRs of 22% with cancer and 11% without cancer (10); New York, with CFRs of 28% with cancer and 14% without cancer (11); Louisiana, with CFRs of 21% with cancer and 9% without cancer (5); and Europe, with CFRs of 22% with cancer and 14% without cancer (ref. 4; Supplementary Table S1). Three series compared outcomes among SARS-CoV-2–infected patients with cancer with uninfected patients with cancer, with two reporting higher mortality in patients with cancer and COVID-19 (Supplementary Table S2; refs. 14–16).

Figure 1.

Scatter plot of COVID-19–related CFRs from series comparing rates from patients with cancer (red dots) with patients without cancer (gray dots). [Series includes publications from Sng et al. (2); Cattaneo et al. (7); Meng et al. (9); Mehta et al. (11); Brar et al. (6); Ruthrich et al. (4); Lunski et al. (5); Tian et al. (10); Wang et al. (3); and Dai et al. (12)].

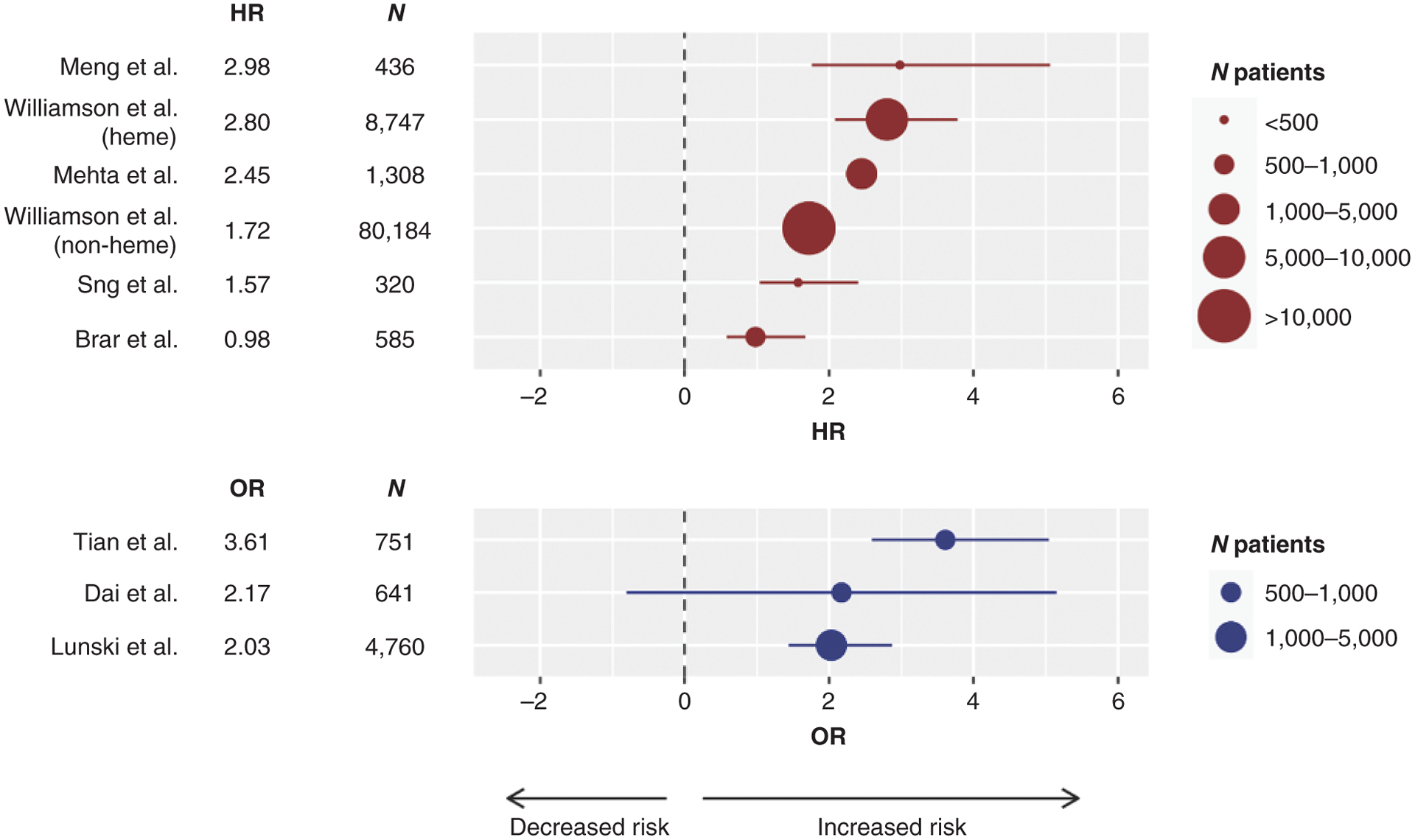

Analysis of adjusted ratios (hazard ratio or odds ratio) confirms a greater risk for severe disease and mortality from COVID-19 in patients with cancer, with variability among series but an overall clear trend (Fig. 2). To determine whether the increased mortality from COVID-19 in patients with cancer was attributable to their underlying malignancies or any of the other factors that are associated with worse outcomes (such as advanced age or adverse comorbidities), several studies adjusted for age, sex, and comorbidities in their analyses and presented the ratios of mortality risks among patients with cancer and a SARS-CoV-2 infection compared with those without cancer. Patients diagnosed with hematologic malignancies were at an especially higher risk. An example is a series from a single hospital in New York, with CFR of 37% in patients with hematologic malignancies compared with 25% in patients with solid cancers. Additional factors such as differences in older age, advanced COVID-19 disease and hospitalizations, and overall quality of care received can all affect outcomes of COVID-19 in patients with cancer.

Figure 2.

Forest plot of series reporting hazard ratios (HR; top in red) or odds ratios (OR; bottom in blue) for death, or severity of COVID-19 in the case of the Tian series, in patients with COVID-19 and cancer compared with no cancer. The size of the symbol is proportional to the number of individuals in each series. The line represents the lower and upper limits of the 95% confidence intervals. Negative HR or OR values favor decreased risk for death, whereas positive values represent increased risk for death or severity of COVID-19. [Series includes publications from Meng et al. (9); Williamson et al. (8); Mehta et al. (11); Williamson et al. (8); Sng et al. (2); Brar et al. (6); Tian et al. (10); Dai et al. (12); and Lunski et al. (5)].

Nine studies did not include a control or reference group in their analysis (Supplementary Table S3; refs. 17–25). These studies reported a high CFR among SARS-CoV-2–infected patients with cancer, which seems to be higher when indirectly compared with existing national or global statistics. However, it is difficult to interpret these data in the absence of an appropriate concurrent control cohort from the same hospital or health care system. The remaining three studies were meta-analyses, two of which confirmed that patients with cancer were at increased risk of fatality and severe illness due to COVID-19 when aggregating all of the available series into an overall estimate (Supplementary Table S4; refs. 26–28).

Information is limited on the effects of COVID-19 vaccination in patients with cancer. Among the 43,540 subjects enrolled in the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine trial, 3.7% were reported to have cancer, with a total of five patients developing COVID-19 at the time of reporting (one in the vaccine arm and four in the placebo arm; ref. 30). Other large COVID-19 vaccine trials with further follow-up will provide useful information on the effectiveness of the vaccines in patients receiving different cancer treatments, as there are currently not enough data to evaluate the interactions between active oncologic therapy with the ability to induce protective immunity to COVID-19 with vaccination (30). Given the evidence that the COVID-19 vaccines may provide greater levels of neutralizing antibodies than SARS-CoV2 infection in a substantial number of patients (31, 32), it would be of high importance to offer priority vaccinations to patients receiving cytotoxic chemotherapy, in particular for hematologic malignancies. Current data suggest that patients with hematologic malignancies have limited immune responses to COVID-19 (33). Patients who do not mount a strong immune response against SARS-CoV2 are likely to shed the virus for a longer time and be a source of continued unintended exposure infecting other persons. Therefore, the case for vaccinating patients with certain cancers who have limited ability to mount a natural neutralizing antibody response to COVID-19 infection is further strengthened to prevent spread to others, in particular given their need for frequent visits to clinics to continue with their cancer care. It is possible that patients with certain cancers receiving anti-CD20 or cytotoxic therapies may not demonstrate an antibody response to the COVID-19 vaccination, but because the current vaccines demonstrate a strong T-cell response, it is possible that they would still result in protective T-cell immunity. Therefore, the benefit of COVID-19 vaccination may not be adequately assessed with serologic testing in these patients.

Finally, after more than a decade of clinical testing, there is currently no evidence that cancer immunotherapy with immune-checkpoint blockade increases the complications from any prior viral vaccine administration. Despite that three of the series we reviewed (5, 19, 21) reported that patients receiving cancer immunotherapies had increased risk of complications and death from COVID-19, it is now recognized that this may reflect the confluence of comorbidities and risk factors in these patients; for example, patients with lung cancer induced by cigarette smoke, who are more likely to have preexisting lung inflammatory disease, which is an adverse risk factor for COVID-19, are more likely to be treated with immune-checkpoint blockade therapies (34). This patient population reflecting several comorbidities may be particularly vulnerable and would benefit from priority vaccination. Therefore, it is reasonable to recommend that patients receiving cancer immunotherapies should be considered for priority COVID-19 vaccination regardless of receiving this therapy.

We conclude that the data in these studies support the recommendation to provide priority COVID-19 vaccination to patients with cancer due to their increased risk of mortality with COVID-19 infection. This recommendation should result in early vaccination to patients who are currently receiving treatment for cancer, or have an advanced cancer that may result in increased risk of complications from COVID-19, in particular for patients with hematologic malignancies and lung cancer. It is unclear whether this recommendation should be applicable to patients with a past diagnosis of cancer, as cancer survivors can be considered to have the same risk as other persons with matched age and other risk factors. The fact that patients undergoing cancer treatments are in very frequent contact with health care workers increases the risk of exposure and puts the patients at the front line of our health care system.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Note: Supplementary data for this article are available at Cancer Discovery Online (http://cancerdiscovery.aacrjournals.org/).

Authors’ Disclosures

A. Ribas reports personal fees from Amgen (honoraria), Chugai (honoraria), Genentech (honoraria), Merck (honoraria), Novartis (honoraria), Roche (honoraria), Sanofi (honoraria), Vedanta (honoraria), Advaxis (scientific advisory board member, honoraria, stock), Apricity (scientific advisory board member, honoraria, stock), Arcus (scientific advisory board member, honoraria, stock), Compugen (scientific advisory board member, honoraria, stock), CytomX (scientific advisory board member, honoraria, stock), Five Prime (scientific advisory board member, honoraria, stock), Highlight (scientific advisory board member, honoraria, stock), ImaginAb (scientific advisory board member, honoraria, stock), Isoplexis (scientific advisory board member, honoraria, stock), Kite/Gilead (scientific advisory board member, honoraria, stock), Lutris (scientific advisory board member, honoraria, stock), Merus (scientific advisory board member, honoraria, stock), PACT (scientific advisory board member, honoraria, stock), RAPT (scientific advisory board member, honoraria, stock), Rgenix (scientific advisory board member, honoraria, stock), and Tango Therapeutics (scientific advisory board member, honoraria, stock) and grants from NCI, Agilent, Bristol-Myers Squibb through Stand Up To Cancer (SU2C), the Melanoma Research Alliance, and the Parker Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy outside the submitted work. R. Sengupta, T. Locke, and S.K. Zaidi are employed by the American Association for Cancer Research. E.M. Jaffee reports grants from Bristol-Myers Squibb; personal fees from Genocea (consultation), Achilles (consultation), DragonFly (consultation), and CSTONE (consultation); other from AbMeta (founder) and PICI (consultant); and reports grants from and is the Chief Medical Advisor for Lustgarten Foundation outside the submitted work. No disclosures were reported by the other authors.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wang Q, Berger NA, Xu R. Analyses of risk, racial disparity, and outcomes among US patients with cancer and COVID-19 infection. JAMA Oncol 2020. December 10 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sng CCT, Wong YNS, Wu A, Ottaviani D, Chopra N, Galazi M, et al. Cancer history and systemic anti-cancer therapy independently predict COVID-19 mortality: a UK tertiary hospital experience. Front Oncol 2020;10:595804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang Q, Berger NA, Xu R. When hematologic malignancies meet COVID-19 in the United States: infections, death and disparities. Blood Rev 2020:100775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rüthrich MM, Giessen-Jung C, Borgmann S, Classen AY, Dolff S, Grüner B, et al. COVID-19 in cancer patients: clinical characteristics and outcome-an analysis of the LEOSS registry. Ann Hematol 2020. November 7 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lunski MJ, Burton J, Tawagi K, Maslov D, Simenson V, Barr D, et al. Multivariate mortality analyses in COVID-19: comparing patients with cancer and patients without cancer in Louisiana. Cancer 2020. October 28 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brar G, Pinheiro LC, Shusterman M, Swed B, Reshetnyak E, Soroka O, et al. COVID-19 severity and outcomes in patients with cancer: a matched cohort study. J Clin Oncol 2020;38:3914–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cattaneo C, Daffini R, Pagani C, Salvetti M, Mancini V, Borlenghi E, et al. Clinical characteristics and risk factors for mortality in hematologic patients affected by COVID-19. Cancer 2020;126:5069–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Williamson EJ, Walker AJ, Bhaskaran K, Bacon S, Bates C, Morton CE, et al. Factors associated with COVID-19-related death using OpenSAFELY. Nature 2020;584:430–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meng Y, Lu W, Guo E, Liu J, Yang B, Wu P, et al. Cancer history is an independent risk factor for mortality in hospitalized COVID-19 patients: a propensity score-matched analysis. J Hematol Oncol 2020; 13:75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tian J, Yuan X, Xiao J, Zhong Q, Yang C, Liu B, et al. Clinical characteristics and risk factors associated with COVID-19 disease severity in patients with cancer in Wuhan, China: a multicentre, retrospective, cohort study. Lancet Oncol 2020;21:893–903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mehta V, Goel S, Kabarriti R, Cole D, Goldfinger M, Acuna-Villaorduna A, et al. Case fatality rate of cancer patients with COVID-19 in a New York hospital system. Cancer Discov 2020;10:935–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dai M, Liu D, Liu M, Zhou F, Li G, Chen Z, et al. Patients with cancer appear more vulnerable to SARS-CoV-2: a multicenter study during the COVID-19 outbreak. Cancer Discov 2020;10:783–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miyashita H, Mikami T, Chopra N, Yamada T, Chernyavsky S, Rizk D, et al. Do patients with cancer have a poorer prognosis of COVID-19? An experience in New York City. Ann Oncol 2020;31: 1088–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fillmore NR, La J, Szalat RE, Tuck DP, Nguyen V, Yildirim C, et al. Prevalence and outcome of COVID-19 infection in cancer patients: a national Veterans Affairs study. J Natl Cancer Inst 2020. October 8 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee LYW, Cazier JB, Starkey T, Briggs SEW, Arnold R, Bisht V, et al. COVID-19 prevalence and mortality in patients with cancer and the effect of primary tumour subtype and patient demographics: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Oncol 2020;21:1309–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jee J, Foote MB, Lumish M, Stonestrom AJ, Wills B, Narendra V, et al. Chemotherapy and COVID-19 outcomes in patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol 2020;38:3538–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pinato DJ, Zambelli A, Aguilar-Company J, Bower M, Sng C, Salazar R, et al. Clinical portrait of the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic in European cancer patients. Cancer Discov 2020;10:1465–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hultcrantz M, Richter J, Rosenbaum C, Patel D, Smith E, Korde N, et al. COVID-19 infections and clinical outcomes in patients with multiple myeloma in New York City: a cohort study from five academic centers. Blood Cancer Discov 2020;1:234–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lara OD, O’Cearbhaill RE, Smith MJ, Sutter ME, Knisely A, McEachron J, et al. COVID-19 outcomes of patients with gynecologic cancer in New York City. Cancer 2020;126:4294–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rivera DR, Peters S, Panagiotou OA, Shah DP, Kuderer NM, Hsu CY, et al. Utilization of COVID-19 treatments and clinical outcomes among patients with cancer: a COVID-19 and Cancer Consortium (CCC19) cohort study. Cancer Discov 2020;10:1514–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Russell B, Moss C, Papa S, Irshad S, Ross P, Spicer J, et al. Factors affecting COVID-19 outcomes in cancer patients: a first report from Guy’s Cancer Center in London. Front Oncol 2020;10:1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garassino MC, Whisenant JG, Huang LC, Trama A, Torri V, Agustoni F, et al. COVID-19 in patients with thoracic malignancies (TERAVOLT): first results of an international, registry-based, cohort study. Lancet Oncol 2020;21:914–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Robilotti EV, Babady NE, Mead PA, Rolling T, Perez-Johnston R, Bernardes M, et al. Determinants of COVID-19 disease severity in patients with cancer. Nat Med 2020;26:1218–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuderer NM, Choueiri TK, Shah DP, Shyr Y, Rubinstein SM, Rivera DR, et al. Clinical impact of COVID-19 on patients with cancer (CCC19): a cohort study. Lancet 2020;395:1907–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee LY, Cazier JB, Angelis V, Arnold R, Bisht V, Campton NA, et al. COVID-19 mortality in patients with cancer on chemotherapy or other anticancer treatments: a prospective cohort study. Lancet 2020; 395:1919–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang H, Han H, He T, Labbe KE, Hernandez AV, Chen H, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of COVID-19-infected cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst 2020. November 2 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saini KS, Tagliamento M, Lambertini M, McNally R, Romano M, Leone M, et al. Mortality in patients with cancer and coronavirus disease 2019: a systematic review and pooled analysis of 52 studies. Eur J Cancer 2020;139:43–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Desai A, Sachdeva S, Parekh T, Desai R. COVID-19 and cancer: lessons from a pooled meta-analysis. JCO Glob Oncol 2020;6:557–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dooling K, McClung N, Chamberland M, Marin M, Wallace M, Bell BP, et al. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices’ interim recommendation for allocating initial supplies of COVID-19 vaccine—United States, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:1857–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Polack FP, Thomas SJ, Kitchin N, Absalon J, Gurtman A, Lockhart S, et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med 2020. December 10 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Widge AT, Rouphael NG, Jackson LA, Anderson EJ, Roberts PC, Makhene M, et al. Durability of responses after SARS-CoV-2 mRNA-1273 vaccination. N Engl J Med 2020. December 3 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gudbjartsson DF, Norddahl GL, Melsted P, Gunnarsdottir K, Holm H, Eythorsson E, et al. Humoral immune response to SARS-CoV-2 in Iceland. N Engl J Med 2020;383:1724–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mathew D, Giles JR, Baxter AE, Oldridge DA, Greenplate AR, Wu JE, et al. Deep immune profiling of COVID-19 patients reveals distinct immunotypes with therapeutic implications. Science 2020;369:eabc8511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Luo J, Rizvi H, Egger JV, Preeshagul IR, Wolchok JD, Hellmann MD. Impact of PD-1 blockade on severity of COVID-19 in patients with lung cancers. Cancer Discov 2020;10:1121–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.