Abstract

The 3-year overall survival (OS) rate of patients with previously treated or untreated stage III or IV melanoma has by now reached 63% using ipilimumab and nivolumab therapy. However, immune-related adverse events (irAEs) of grade 3 or 4 occurred in 59% of patients leading to discontinuation of therapy in 24.5% of patients and one death. Therapy with checkpoint inhibitors could be safer and more effective in combination with hyperthermia and fever inducing therapies. We conducted a retrospective analysis to test the safety and efficacy of a new combination immune therapy in 131 unselected stage IV solid cancer patients with 23 different histological types of cancer who exhausted all conventional treatments. Treatment consisted of locoregional- and whole-body hyperthermia, individually dose adapted interleukin 2 (IL-2) combined with low-dose ipilimumab (0.3 mg/kg) plus nivolumab (0.5 mg/kg). The objective response rate (ORR) was 31.3%, progression-free survival (PFS) was 10 months, survival probabilities at 6 months was 86.7% (95% CI, 81.0–92.8%), at 9 months was 73.5% (95% CI, 66.2–81.7%), at 12 months was 66.5% (95% CI, 58.6–75.4%), while at 24 months survival was 36.6% (95% CI:28.2%; 47.3%). irAEs of World Health Organization (WHO) Toxicity Scale grade 1, 2, 3, and 4 were observed in 23.66%, 16.03%, 6.11%, and 2.29% of patients, respectively. Our results suggest that the irAEs profile of the combined treatment is safer than that of the established protocols without compromising efficacy.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s00262-020-02751-0) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Stage IV cancer, Immunotherapy, Hyperthermia, IL-2, Checkpoint inhibitors, irAEs

Introduction

Concurrent ipilimumab and nivolumab treatment has by now achieved a 3-year overall survival (OS) rate of 63% for patients with advanced melanoma [1]. However, the treatment-related irAEs were reported in 96.8% of patients, 58.5% of which were grade 3 and 4 leading to discontinuation in 24.5% of patients and one death. Ultimately immune checkpoint therapy (ICI) will continue to increase exponentially, bringing with it a growing burden of irAEs [2]. The meta-analysis of Xing et al. including 48 trials with 7936 patients who were treated with mono-therapeutic nivolumab or nivolumab plus ipilimumab raised the issue that the deleterious effects of severe irAEs might outweigh the benefit from the addition of ipilimumab [3]. Predictive biomarkers might help selecting patients who will derive the greatest benefit from ICIs [4]. However, selection of patients may not be required if lower ICI dosages are used.

Rationale for low-dose ICI therapy

In the above context it is important to recall that the original rationale for immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) therapy was based on the assumption that the blockade selectively targets T-cells relevant to the antitumor immune response [5]. Unfortunately, this assumption cannot be reconciled with the widespread irAEs observed in the vast majority of patients (see for example in [6]). As a matter of fact, Bakacs et al. proposed already in 2012 that the ipilimumab-induced irAEs were very similar to that of a chronic graft-versus-host-disease (GVHD) reaction following allogeneic bone marrow transplantation (BMT) [7, 8]. They speculated that ipilimumab induced a graft-versus-malignancy (GVM) effect by the patients’ own lymphocytes, which eradicated metastatic melanoma in a minority of patients, but also involved an auto-GVHD reaction that resulted in widespread autoimmunity in the majority. In the face of an ipilimumab-induced pan-lymphocytic activation, based on an alternative interpretation of the seminal NEJM paper by Hodi et al. [9], a therapeutic paradigm shift was proposed. The task is not desperately trying to put the genie back in the bottle by immune suppressive treatments, but instead harnessing the autoimmune forces for therapeutic purposes. This idea paved the way for administering lower doses of ICI drugs.

Slavin et al. were the first to suggest that a finely tuned, low-dose (0.3 mg/kg) ipilimumab treatment course would induce a prolonged auto-GVHD that would improve the antitumor efficacy of the patients’ own lymphocytes for a broad spectrum of malignancies at the stage of minimal residual disease (MRD) [10]. In this way, the same goal could be achieved by an antibody (ipilimumab) as by the adoptive transfer of alloreactive donor lymphocytes, but of course, without severe GVHD.

The low-dose ICI idea was first adopted by Kleef et al. for stage IV cancer patients [11, 12]. Following the quantitative paradigm of T-cell activation [13, 14], which states that the outcome of signals from the TCR, co-stimulatory/co-inhibitory receptors and cytokines are synergistic, Kleef combined an off label low-dose anti-CTLA-4 plus anti-PD-1 antibody blockade with hyperthermia, and individualized dosing of IL-2 treatment. The synergism of the various T-cell stimulatory effects was first demonstrated in a heavily pre-treated triple negative breast cancer (TNBC) patient, with far advanced pulmonary metastases and severe shortness of breath, who had exhausted all conventional treatment [11]. The patient was treated with a safe, low-dose immune checkpoint blockade, including ipilimumab (0.3 mg/kg) combined with nivolumab (0.5 mg/kg). This was complemented with an individually dosed IL-2 treatment under taurolidine protection and loco regional- and whole-body hyperthermia, without classical chemotherapy. The patient went into complete remission of her lung metastases and all cancer-related symptoms vanished with transient WHO I-II diarrhea and skin rash (Fig. 1a, b). A total gene expression analysis of a metastatic axillary lymph node demonstrated that several checkpoint genes were over-expressed even one year after the initiation of therapy. The patient remained alive for 27 months after the start of treatment, with recurrence of metastases as a sternal mass, and up to 3 cm pleural metastases, which finally classified this patient having a mixed overall response. Following the TNBC patient, the proof-of-principle of this low-dose combination immune checkpoint therapy, consisting only of approved drugs and treatments, was demonstrated in many further cancer patients [12, 15].

Fig. 1.

Detailed history and chest X-rays of a patient with triple-negative breast cancer from diagnosis and treatment before (a) and after attending (b) the outpatient clinic with the respective regimen. Long-term follow-up is also displayed supported by chest X-rays.

Reproduced from Kleef et al., Integrative Cancer Therapies 2018, Vol. 17(4) 1297–1303 with permission from SAGE Publishing 2600 Virginia Ave NW, Suite 600 Washington, DC 20,037 USA

A recent model-based meta-analysis that evaluated safety data from 80 published clinical trials (representing 21,305 patients from 153 dosing cohorts) supports the view that combination treatment with CTLA-4 and PD-1 inhibitors increases irAE rates beyond additivity [16]. With the benefit of hindsight, this finding also justifies the rationale of our combined low-dose anti-CTLA-4 plus anti-PD-1 antibody blockade.

Methods and treatment

All patients signed informed consent to the experimental (off-label) treatment including consent to evaluate patients retrospectively for scientific publication. Unselected patients with 23 cancer types (see patient’s demographics in Table supply 1) were treated in a named patient program with individualized dosing of checkpoint inhibitor therapy, hyperthermia and IL-2. The majority of patients were treated with a combination of anti-program cell death-1 receptor (anti-PD-1) checkpoint inhibitor nivolumab and anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein-4 (anti-CTLA-4) checkpoint inhibitor ipilimumab with 0.5 mg/kg and 0.3 mg/kg, respectively. The data collection and documentation were retrieved retrospectively from all patients following the completion of therapy. All patient’s data were entered retrospectively into a professional clinical data monitoring system Dendrite® for statistical analysis. Staging was performed with iRECIST in stage IV patients [17]. Checkpoint inhibitor therapy was combined with three modalities: local–regional-, whole-body- and endogenous hyperthermia with IL-2, with the dose titrated individually in each patient to achieve a febrile response of 39–40 °C (temperature was measured by a rectal probe) (Table supply 2).

Molecular biology diagnosis

It is widely accepted that expression of PD-L1, tumor mutational burden (TMB) and microsatellite instability (MSI) are strongly correlated with positive response towards immunotherapy with checkpoint inhibitors. The overwhelming majority of cancer patients described in the literature have low MSI and TMB with only a small percentage of patient having positive expression of PD-L1. In our patient group, we could not systematically evaluate TMB and MSI, but the majority of our patients have undergone next generation sequencing (NGS) analysis on tumor biopsies, circulating tumor cells (CTC) assays and tumor chemosensitivity assays (TCA). The immunohistochemical determination of PD-L1 was performed by PD-L1 IHC 22C3 pharmDx (Dako North America, Inc) (data not shown).

Patients demographics

The baseline patient and disease characteristics are presented in Table supply 1.

Treatment

All patients received the combination treatment described below, if not stated otherwise.

Nivolumab was administered IV over 60 min on days 1, 15, and 29 and ipilimumab IV over 90 min on day 1 and day 15. Courses were repeated every 3-month in the absence of disease progression or unacceptable toxicity (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Treatment courses were repeated every 3 months until reaching 3–4 cycles in total in the absence of disease progression or unacceptable toxicity

-

2)

Loco-regional hyperthermia (radiofrequency device 13.56 MHz, Syncrotherm/ Oncotherm) 3×/weekly 60′ over 4 weeks over the tumor area, 12 txts [18, 19].

-

3)

Long duration whole body hyperthermia (w-IRA Heckel HT3000) under light sedation one time in the week prior to IL-2 therapy with moderate dosed cyclophosphamide 300 mg/m2 to down-modulate expected upregulation of Treg cells [20, 21]. Treg cell numbers (available in 37 patients) was indeed down-modulated to 28.1% during therapy and then upregulated to 107.1% after therapy; paired t tests for all three comparisons (before vs. during, during vs. after, before vs. after) were significant with p values < 0.001 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Outcome measures

| Variable | Value (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| ORR | |

| Overall | 31.3% [24.0%; 39.7%] |

| With antibiotics treatment | 26.5% [14.6%; 43.1%] |

| Primary tumor location: Breast | 31.0% [19.1%; 46.0%] |

| Primary tumor location: Colon | 27,3% [9,7; 56,6%] |

| Primary tumor location: Ovary | 36,4% [15,2; 64,6%] |

| Primary tumor location: Prostate | 45,5% [21,3; 72%] |

| Checkpoint Inhibitor*: Ipilimumab, Nivolumab | 32,2% [24,3; 41,2%] |

| Checkpoint Inhibitor*: Nivolumab | 23,1% [8,2; 50,3%] |

| *only “ipi + nivo” und “nivo” are included as n for other combinations are too low | |

| ECOG 2 or 3 | 23.3% [11.8%; 40.9%] |

| Overall survival | |

| 6 months | 87.6% [82%; 93.5%] |

| 9 months | 72.9% [65.5%; 81.1%] |

| 12 monts | 65.9% [58%; 74.9%] |

| Median (months) | 19.3 [15.2; 22.9] |

| Progression-free survival | |

| 6 months | 60.3% [52.5%; 69.3%] |

| 9 months | 42.7% [35.1%; 52.1%] |

| 12 monts | 36.4% [29%; 45.7%] |

| Median (months) | 7.1 [6.2; 10.5] |

| 20 patients (15.3%) had CR; their median time until progression was 20.7 months | |

| Median time until progression for subgroups (all diagnosis with n > 10) | |

| Breast | 8.0 months |

| Colon | 6.4 months |

| Ovary | 4.5 months |

| Prostate | 12.8 months |

| Others | 7.5 months |

| Treg cell numbers* | |

| Before therapy | 60,4% [49,6; 71,1%] |

| During therapy | 28,1% [21,9; 34,3%] |

| After therapy | 107,1% [84,3; 129,9%] |

*At least one measurement was available for 37 patients; paired t tests for all three comparisons (before vs. during, during vs. after, before vs. after) were significant with P values < 0.001

-

4)

IL-2 (Proleukin®) – induced fever therapy: 1 × /month daily 4 × over 1-week outpatient treatment with individually dose adapted IL-2 and Taurolidine. The addition of Taurolidine is mitigating the well-known cytokine storm induced by IL-2, and thus increasing the safety of our protocol [22]. Specifically, Taurolidine was used both during ICI infusions and IL-2 treatment; during ICI treatment patients received 3 × 250 ml of 2% Taurolidine; the dosage during IL-2 treatment was 2 × 250 ml Taurolidine 2% over 8 h. IL-2 was titrated to daily fever responses of 39.0–40 °C depending on the clinical condition. IL-2 was applied via motor-syringe pump with a total dosage of 5–14 Mio/m2 and infusion speed of 5–7.5 ml/h/day depending on the clinical condition and fever induction response; depending on the fever response the infusion was stopped; IL-2 was perfused to a maximum fever of 38.5 °C; still, the fever curve always was expected to rise up to a temperature level of 39–40 °C body core temperature measured with rectal probe. Monitoring was performed with continuous measuring of body core temperature, blood pressure, heart rate and oxygen saturation SpO2 (Mindray® bio-monitor) as well as daily routine laboratory assessments.

Courses were repeated every 3 months until reaching three cycles in total in the absence of disease progression or unacceptable toxicity. Additional chemotherapy, targeted therapy and hormonal therapy was allowed and documented meticulously (Table supply 2).

Parallel to local regional hyperthermia patients received 3 times weekly high dose vitamin C intravenously (0.5 g/kg) and alpha lipoic acid 600 mg. High-dose vitamin C has been suggested as an adjuvant cancer treatment as it is toxic to tumor cells, since it targets many of the mechanisms that cancer cells utilize for their survival and growth. High-dose vitamin C delays cancer growth by enhancing infiltration of the tumor microenvironment by immune cells and cooperates with immune checkpoint therapy (ICT) in several cancer types [23–26]. Lipoic acid synergistically enhanced ascorbate cytotoxicity [27] and inhibited the enzyme pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase that is particularly upregulated in cancer cells and is the major determinant of the “Warburg effect”, thus contributing to a higher vulnerability/decreased resilience of the neoplasm [28].

Statistical analysis

OS and PFS were defined as the time from admission until the patients’ death and the first evidence of disease progression, respectively. All continuous variables are presented by median and first and third quartile. Absolute and relative frequencies were derived for categorical data. Median follow-up for OS was estimated by reverse Kaplan–Meier method. Kaplan–Meier curves including 95% confidence intervals were derived for OS and PFS. Cox proportional hazard models for OS and PFS were estimated with diagnosis “breast cancer” as explanatory dummy variable. Differences in Treg cell numbers before, during, and after therapy were analyzed using paired t tests. 95% confidence intervals were estimated for outcomes, including dichotomous measures and median survival times. All statistical analyses were performed with the statistical software R version 3.6.1 (R Core Team 2019).1

Results

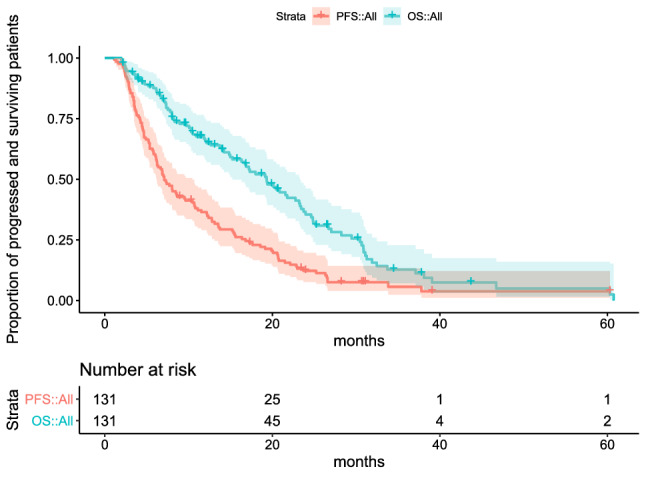

Stage IV cancer patients (staging with iRECIST; n = 131) demonstrated objective response rate (ORR) 31.3%, overall response rate (OR) 49.62%: complete response (CR) 20 patients, partial response (PR) 21 patients, no change (NC) 24 patients, stable disease (SD) 65 patients, and mixed response (MR) 1 patient, progression-free survival (PFS) was 10 months. Survival probabilities at 6, 9, 12, 24 months, irAEs of WHO grading and outcome measures are presented in Tables 1 and 2. Kaplan–Meier curves of PFS and OS in all the 131 cancer patients are presented in Fig. 3. Comparisons of Kaplan–Meier curves of PFS and OS in all the 131 cancer patients and in 42 breast cancer patients are presented in Fig. 4a, b, respectively. Hazard ratios (HR) for the difference between all cancers and breast cancers were not significant (OS: HR: 0.901, 95% CI: [0.715, 1.722] P: 0.643; PFS HR: 0.918, 95% CI: [0.742, 1.600] P: 0.661).

Table 1.

Survival probabilities and irAEs

| Survival-probabilities at | |

| 6 months | 87.6% [95% CI: 82%; 93.5%] |

| 9 months | 72.9% [95% CI: 65.5%; 81.1%] |

| 12 months | 65.9% [95% CI: 58%; 74.9%] |

| 24 months | 36.6% [95% CI: 28.2%; 47.3%] |

| irAEs of WHO | |

| Grade 1 | 23.66% |

| Grade 2 | 16.03% |

| Grade 3 | 6.11% |

| Grade 4 | 2.29% |

Fig. 3.

Kaplan–Meier curves of progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) in all the 131 cancer patients. 95% confidence intervals are indicated by filled areas around curves, censored observations by “ + ”

Fig. 4.

Comparisons of Kaplan–Meier curves of PFS (a) and OS (b) in all the 131 cancer patients and in 42 breast cancer patients. The hazard ratio (HR) for the difference between all the 131 cancers and 42 breast cancers was estimated using a Cox proportional hazard model and no significant differences were found (PFS: HR: 0.918, 95% CI: [0.742, 1.600] P: 0.661; OS: HR: 0.901, 95% CI: [0.715, 1.722] P: 0.643)

Discussion

Here, we conducted a retrospective analysis of 131 unselected stage IV cancer patients with 23 different cancer types who were treated with T-cell-stimulating modalities, hyperthermia, IL-2, and ipilimumab plus nivolumab (0.5 mg/kg and 0.3 mg/kg, respectively). Twenty-four percent of our patients had to receive antibiotics. Antibiotic treatments administered within 30 days from commencement of ICI therapy has been known to be associated with significantly worse overall survival in patients with nonsmall cell lung cancer (2.5 vs. 26 months), melanoma (3.9 vs. 14 months), and other tumor types (1.1 vs. 11) who received antibiotic treatment vs. those who did not. In addition, patients had a higher risk of disease refractory to treatment [29].

During a follow-up period of up to 5 years, the ORR and OR were 31.3% and 49.62%, respectively, while the OS at 12 months was 65.9% (Table 2). irAEs of WHO grade 1, 2, 3, and 4 were observed in 23.66%, 16.03%, 6.11%, and 2.29% of patients, respectively (Table 3). In other words, less than half (48.09%) of the patients experienced irAEs of any grade, while only 8.4% had grade 3 or 4 irAEs, but no treatment-related death occurred. Therefore, our protocol does not require selection of stage IV cancer patients who are more likely to gain benefit from ICIs. Our safety results compare favorably to that of the study by Callahan et al. but also to the meta-analysis of Xu et al., in both of which registered doses of concurrent nivolumab and ipilimumab treatment were administered. Any-grade irAEs occurred in 96.8% of patients in Callahan’s study, while 58.5% of patients had grade 3 and 4 irAEs leading to discontinuation in 24.5% of patients, and one treatment-related death was also reported [1]. Similarly, grade 3–4 irAEs occurred in 39.9% of patients in the meta-analysis of Xu et al., while 2.0% treatment-related death was recorded [30].

Table 3.

Immune-related adverse events

| Group | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Grade | |

| 1 | 31 (23.7%) |

| 2 | 21 (16%) |

| 3 | 8 (6.1%) |

| 4 | 3 (2.3%) |

| No irAE | 68 (51.9%) |

| irAE (Grade I) | |

| Diarrhea | 12 (9.2%) |

| Skin rash | 11 (8.4%) |

| Mildly elevated GOT/GPT | 3 (2.3%) |

| Pruritus | 3 (2.3%) |

| Dyspnea | 2 (1.5%) |

| Mouth ulcers | 2 (1.5%) |

| Nausea | 2 (1.5%) |

| Thyroid dysfuction | 2 (1.5%) |

| Abdominal dyscomfort | 1 (0.8%) |

| Dry cough | 1 (0.8%) |

| Elevated blood Glc | 1 (0.8%) |

| Flu-like symptoms | 1 (0.8%) |

| Melena | 1 (0.8%) |

| irAE (Grade II) | |

| Moderately elevated GOT/GPT | 10 (7.6%) |

| Mild pneumonitis | 7 (5.3%) |

| Massive diarrhea | 1 (0.8%) |

| Massive edema | 1 (0.8%) |

| Quincke-edema | 1 (0.8%) |

| Strong skin rash | 1 (0.8%) |

| irAE (Grade III) | |

| Autoimmune hepatitis (3) | 3 (2.3%) |

| Autoimmune thyroiditis (3) | 3 (2.3%) |

| Autoimmune colitis (3) | 2 (1.5%) |

| irAE (Grade IV) | |

| Autoimmune DM (4) | 2 (1.5%) |

| Acute kidney injury (4) | 1 (0.8%) |

| Autoimmune thyroiditis (4) | 1 (0.8%) |

The combination of ipilimumab and nivolumab has first been established in melanoma [31] and renal cell cancer [32] but also described for nonsmall cell lung cancer [33, 34]. In these patients, it is well known that high mutational burden favors better response rates [35]. Although immunotherapy has become one of the greatest advances in oncology over the last century, the application for the treatment of breast cancer remains an area of investigation [36]. Consistent with this, we found 1365 papers with the key words < cancer, ipilimumab, nivolumab > but only 18 with the key words < breast cancer, ipilimumab, nivolumab > (PubMed search as of June 2020). Based on our data presented in this paper, such neglect of breast cancer seems to be unjustified. We estimated the hazard ratio (HR) for the difference between all the 131 cancers and 42 breast cancers using a Cox proportional hazard model and found no significant differences (Fig. 4a, b). 95% confidence intervals for HRs provide ranges of plausible values for the true HRs of our data.

Importantly, the overwhelming majority (> 98%) of the evaluated patients in this study had low PD-L1 expression as confirmed by immunohistochemistry (determined as ≤ 1%). Low tumor mutational burden (TMBlow) and low microsatellite instability (MSIlow) was determined only in a small subgroup of patients. However, TMBlow and MSIlow can be expected in the majority based on published evidence [37]. In contrast, published meta-analyses included patients with high PD-L1 expression, TMBhigh, and MSIhigh [30, 38]. Therefore, in contrast to the published meta-analysis, our patient group had the following negative pre-selection factors:

Antibiotic use in 24%;

Low PD-1/PD-L1 expression;

Only stage IV patients, with 35.1% liver metastasis, a specifically bad prognosis;

Only 35% ECOG 0;

Heavily pretreated patients.

Control of minimal residual cancer by exploiting autoimmunity induced by low-dose ipilimumab was proposed earlier [10]. For safety reasons, we administered the lowest doses of nivolumab (0.5 mg/kg) and ipilimumab (0.3 mg/kg), which induced grade 3 or 4 irAEs in only 8.4% of patients (Table 1.). The low dose ICI protocol was justified by Sen et al., who demonstrated that despite a dose-dependent increase in irAEs, no improvement in PFS, OS, or disease control rate (DCR) were identified with escalating doses of ICIs [39]. The authors concluded that lower doses may reduce toxicity and cost without compromising disease control or survival. In fact, due to the rapidity of development, competition, and race for FDA approval, the optimal dosing and schedule of ICIs are still not fully defined and continue to be under study [40].

Weber predicted 10 years ago that abrogation of the CTLA-4 function results in immune stimulation, tolerance breakdown and eventually tumor eradication [41]. This prediction has recently been formally confirmed by Eggermont et al. in a study including 1019 adults with stage III melanoma, in which patients were randomly assigned on a 1:1 ratio to receive treatment with pembrolizumab therapy or placebo [42]. The occurrence of an irAE was indeed associated with a significantly longer recurrence-free survival (RFS) in the pembrolizumab arm.

ICIs are more likely to halt tumor growth in patients with a higher TMB than in those with a lower one [43, 44]. According to the consensus of experts, mutational load in cancer cells (e.g., lung cancer patients with former nicotine abuse) may generate novel antigens that are not subject to immune tolerance and allow for an adaptive immune response by the host. We proposed an alternative interpretation for the induction of immune response. Tumor cells with newly expressed neoantigens are no longer recognized as “self” because they are transformed into “non-self” such that they become targets for the patient’s own immune system. Owing to the newly expressed neoantigens the unresponsiveness/tolerance that existed between the patient’s immune system and cancer cells was abolished. This in turn, resulted in the development of an auto-GVHD with secondary therapeutic benefits, in analogy with the GVM effects following allogeneic stem cell transplantation [15]. Although a limited transformation is too weak in itself to instigate a tumor eradicating T-cell attack, with immune checkpoint blockade T cells are more effective against “altered self” resulting in better OS [45]. Not unexpectedly, a significant positive correlation was found between the reporting odds ratio (ROR) of reporting an irAE during anti-CTLA-4, anti-PD-1, and anti-CTLA-4/anti-PD-1 immune combination therapies and the corresponding TMB in 7677 patients across 19 cancer types [46]. Consistent with this, Berner et al. demonstrated in NSCLC that T cells recognize and target shared tumor and skin antigens during ICI therapy resulting in autoimmune-mediated skin toxicity and tumor regression [47].

Fever therapy and checkpoint inhibitors

Combining thermal therapy with immune therapy should greatly increase the response rate of immune therapy as all types of hyperthermia appear to increase the numbers of effector lymphocytes [48, 49]. Inducing one week of daily cyclic high fever response during individually dose adapted IL-2 we are in the footsteps of William B. Coley, the father of cancer immunotherapy who administered an FDA-approved fever inducing bacterial inoculate for the treatment of soft tissue sarcomas [50]. It is worth to recall that in 1891 Coley was convinced that stimulating the immune system by a severe infection (such as erysipelas), which was associated with high fever, would have the side effect of shrinking the malignant tumor [51]. By the end of his career, Coley had written over 150 papers and treated almost 1000 cases and noticed that in 500 of these there was near-complete regression [52].

Hyperthermia is almost always used in combination with other forms of cancer therapy [49, 53]. While many studies have shown a significant reduction in tumor size, just a few could demonstrate a moderately increased survival in patients receiving the combined treatments (e.g., [19]). Our response rates in stage IV patients with unfavorable MSIlow, PD-L1 < 1%, TMBlow, 26% of which received antibiotics are promising. Since the proposed protocol consists only of approved drugs and treatments, our hypothesis that low‐dose ICI‐induced autoimmune T cells are powerful therapeutic tools can be confirmed or refuted in controlled prospective clinical trials.

Limitations

A retrospective analysis of case series cannot replace a controlled prospective clinical trial, the gold standard for the evaluation of new treatments. Furthermore, this study was underpowered to detect differences between survival rates in cancer subgroups. Notwithstanding, case reports and series represent relevant study designs, which can be highly influential in furthering medical knowledge despite of their limitations when a question of importance cannot be addressed by other methods because of ethical or logistical constraints [54, 55].

Conclusions

Here we demonstrated in 131 unselected stage IV cancer patients that hyperthermia, combined with individually dose adapted IL-2 treatment and low doses of nivolumab plus ipilimumab, can be converted from a palliative therapy into a treatment with curative intent because the autoimmune forces unleashed by ICI drugs can be harnessed by a multicomponent T-cell stimulation therapy. It is tempting to speculate whether adding an oncolytic virus (e.g., the oncolytic Newcastle Disease Virus2) or novel bacterial vaccines [56] to the protocol would break therapy resistance of patients who respond poorly to this new immune therapy [57, 58].

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

For the very helpful comments, we would like to thank, Wayne B. Jonas, MD, President and Chief Executive Officer of Samueli Institute, Washington D.C., USA and Prof. Dr. med. Rolf Issels, MD PhD, Klinikum Grosshadern der LMU Medizinische Klinik III – Innere Medizin, Germany.

Abbreviations

- auto-GVHD

Autologous-graft-versus-host-like-disease

- CTLA-4

Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein-4

- GVM

Graft-versus-malignancy effect

- ICI

Immune checkpoint inhibitors

- irAEs

Immune related adverse effects

- IL-2

Interleukin-2

- MSIlow

Low microsatellite instability

- NK cell

Natural killer cell

- ORR

Objective response rate

- OR

Overall response rate

- OS

Overall survival

- PD-1

Programmed cell death-1 protein

- PFS

Progression free survival

- RECIST

Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors

- TMBlow

Low tumor mutation burden

- WBH

Whole-body hyperthermia

Author contributions

TB and RK mainly contributed to the manuscript, RN performed clinical evaluation, VB was responsible for retrospective data evaluation, AB performed statistics, HB performed molecular biology analysis, DM, RM, NT, and MS added helpful comments.

Funding

Open access funding provided by ELKH Alfréd Rényi Institute of Mathematics.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflicts of interest

RK holds international patent protection. TB is a partner and CSO of PRET Therapeutics Ltd, developing the patented low‐dose ICI combination therapy.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Treatment was performed on an individual basis (named patient use) with extensive written informed consent to undergo the treatment and retrospectively evaluate the data including patient’s consent to publish the data. Therefore, no formal ethical committee had to be involved.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Callahan MK, Kluger H, Postow MA, et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab in patients with advanced melanoma: updated survival, response, and safety data in a phase i dose-escalation study. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:391–398. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.72.2850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bermudez MV, Papa S. Setting the scene - a future 'epidemic' of immune-related adverse events in association with checkpoint inhibitor therapy. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2019;58:1–6. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kez402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xing P, Zhang F, Wang G, et al. Incidence rates of immune-related adverse events and their correlation with response in advanced solid tumours treated with NIVO or NIVO+IPI: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Immuno Thera Cancer. 2019;7:341. doi: 10.1186/s40425-019-0779-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pirker R. Biomarkers for immune checkpoint inhibitors in advanced nonsmall cell lung cancer. Curr Opin Oncol. 2019;31:24–28. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0000000000000496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Curran MA, Callahan MK, Subudhi SK, Allison JP. Response to “Ipilimumab (Yervoy) and the TGN1412 catastrophe”. Immunobiology. 2012;217:590–592. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brahmer JR, Lacchetti C, Schneider BJ, et al. Management of immune-related adverse events in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy: American Society of clinical oncology clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:1714–1768. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.77.6385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bakacs T, Mehrishi JN, Szabo M, Moss RW. Interesting possibilities to improve the safety and efficacy of ipilimumab (Yervoy) Pharmacol Res. 2012;66:192–197. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2012.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bakacs T, Mehrishi JN, Moss RW. Ipilimumab (Yervoy) and the TGN1412 catastrophe. Immunobiology. 2012;217:583–589. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2011.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hodi FS, O'Day SJ, McDermott DF, et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:711–723. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Slavin S, Moss RW, Bakacs T. Control of minimal residual cancer by low dose ipilimumab activating autologous anti-tumor immunity. Pharmacol Res. 2014;79:9–12. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2013.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kleef R, Moss RW, Szasz AM, Bohdjalian A, Bojar H, Bakacs T. From partial to nearly complete remissions in stage IV cancer administering off-label low-dose immune checkpoint blockade in combination with high dose interleukin-2 and fever range whole body hyperthermia. ASCO J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:e23111. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.34.15_suppl.e23111. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kleef R, Moss R, Szasz AM, Bohdjalian A, Bojar H, Bakacs T. Complete clinical remission of stage iv triple-negative breast cancer lung metastasis administering low-dose immune checkpoint blockade in combination with hyperthermia and interleukin-2. Integr Cancer Ther. 2018;17:1297–1303. doi: 10.1177/1534735418794867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gett AV, Hodgkin PD. A cellular calculus for signal integration by T cells. Nat Immunol. 2000;1:239–244. doi: 10.1038/79782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marchingo JM, Kan A, Sutherland RM, et al. T cell signaling. Antigen affinity, costimulation, and cytokine inputs sum linearly to amplify T cell expansion. Science. 2014;346:1123–1127. doi: 10.1126/science.1260044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bakacs T, Moss RW, Kleef R, Szasz MA, Anderson CC. Exploiting autoimmunity unleashed by low-dose immune checkpoint blockade to treat advanced cancer. Scand J Immunol. 2019;1:e12821. doi: 10.1111/sji.12821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shulgin B, Kosinsky Y, Omelchenko A, et al. Dose dependence of treatment-related adverse events for immune checkpoint inhibitor therapies: a model-based meta-analysis. OncoImmunology. 2020;9:1748982. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2020.1748982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seymour L, Bogaerts J, Perrone A, et al. iRECIST: guidelines for response criteria for use in trials testing immunotherapeutics. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:e143–e152. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30074-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Szasz AM, Minnaar CA, Szentmártoni G, Szigeti GP, Dank M. Review of the clinical evidences of modulated electro-hyperthermia (mEHT) method: an update for the practicing oncologist. Front Oncol. 2019 doi: 10.3389/fonc.2019.01012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Issels RD, Lindner LH, Verweij J, et al. Effect of Neoadjuvant chemotherapy plus regional hyperthermia on long-term outcomes among patients with localized high-risk soft tissue sarcoma: the EORTC 62961-ESHO 95 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4:483–492. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.4996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Repasky EA, Evans SS, Dewhirst MW. Temperature matters! And why it should matter to tumor immunologists. Cancer Immunol Res. 2013;1:210–216. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-13-0118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhong H, Lai Y, Zhang R, Daoud A, Feng Q, Zhou J, Shang J. Low dose cyclophosphamide modulates tumor microenvironment by tgf-beta signaling pathway. Int J Mol Sci. 2020 doi: 10.3390/ijms21030957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O'Brien GC, Cahill RA, Bouchier-Hayes DJ, Redmond HP. Co-immunotherapy with interleukin-2 and taurolidine for progressive metastatic melanoma. Ir J Med Sci. 2006;175:10–14. doi: 10.1007/bf03168992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ngo B, Van Riper JM, Cantley LC, Yun J. Targeting cancer vulnerabilities with high-dose vitamin C. Nat Rev Cancer. 2019;19:271–282. doi: 10.1038/s41568-019-0135-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yun J, Mullarky E, Lu C, et al. Vitamin C selectively kills KRAS and BRAF mutant colorectal cancer cells by targeting GAPDH. Science. 2015;350:1391–1396. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa5004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Luchtel RA, Bhagat T, Pradhan K, Jacobs WR, Jr, Levine M, Verma A, Shenoy N. High-dose ascorbic acid synergizes with anti-PD1 in a lymphoma mouse model. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117:1666–1677. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1908158117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Magri A, Germano G, Lorenzato A, et al. High-dose vitamin C enhances cancer immunotherapy. Sci Transl Med. 2020 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aay8707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Casciari JJ, Riordan NH, Schmidt TL, Meng XL, Jackson JA, Riordan HD. Cytotoxicity of ascorbate, lipoic acid, and other antioxidants in hollow fibre in vitro tumours. Br J Cancer. 2001;84:1544–1550. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2001.1814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guais A, Baronzio G, Sanders E, et al. Adding a combination of hydroxycitrate and lipoic acid (METABLOC) to chemotherapy improves effectiveness against tumor development: experimental results and case report. Invest New Drugs. 2012;30:200–211. doi: 10.1007/s10637-010-9552-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pinato DJ, Howlett S, Ottaviani D, et al. Association of prior antibiotic treatment with survival and response to immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy in patients with cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5:1774–1778. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.2785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xu H, Tan P, Ai J, Zhang S, Zheng X, Liao X, Yang L, Wei Q. Antitumor activity and treatment-related toxicity associated with nivolumab plus ipilimumab in advanced malignancies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Pharmacol. 2019;10:1300. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2019.01300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wolchok JD, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R, et al. Overall Survival with combined nivolumab and ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1345–1356. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1709684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gao X, McDermott DF. Ipilimumab in combination with nivolumab for the treatment of renal cell carcinoma. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2018;18:947–957. doi: 10.1080/14712598.2018.1513485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hellmann MD, Rizvi NA, Goldman JW, et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab as first-line treatment for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (CheckMate 012): results of an open-label, phase 1, multicohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:31–41. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30624-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hellmann MD, Paz-Ares L, Bernabe Caro R, et al. Nivolumab plus Ipilimumab in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:2020–2031. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1910231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hellmann MD, Ciuleanu TE, Pluzanski A, et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab in lung cancer with a high tumor mutational burden. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2093–2104. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1801946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Force J, Leal JHS, McArthur HL. Checkpoint blockade strategies in the treatment of breast cancer: where we are and where we are heading. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2019;20:35. doi: 10.1007/s11864-019-0634-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wood MA, Weeder BR, David JK, Nellore A, Thompson RF. Burden of tumor mutations, neoepitopes, and other variants are dubious predictors of cancer immunotherapy response and overall survival. biorXiv. 2020;1:665026. doi: 10.1101/665026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu K, Yi M, Qin S, Chu Q, Zheng X, Wu K. The efficacy and safety of combination of PD-1 and CTLA-4 inhibitors: a meta-analysis. Exp Hematol Oncol. 2019;8:26. doi: 10.1186/s40164-019-0150-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sen S, Hess KR, Hong DS, Naing A, Huang L, Meric-Bernstam F, Subbiah V. Impact of immune checkpoint inhibitor dose on toxicity, response rate, and survival: a pooled analysis of dose escalation phase 1 trials. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:3077. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2018.36.15_suppl.3077. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Baik CS, Rubin EH, Forde PM, Mehnert JM, Collyar D, Butler MO, Dixon EL, Chow LQM. Immuno-oncology clinical trial design: limitations, challenges, and opportunities. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:4992–5002. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-3066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weber J. Ipilimumab: controversies in its development, utility and autoimmune adverse events. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2009;58:823–830. doi: 10.1007/s00262-008-0653-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Eggermont AMM, Kicinski M, Blank CU, et al. Association between immune-related adverse events and recurrence-free survival among patients with stage iii melanoma randomized to receive pembrolizumab or placebo: a secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.5570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Samstein RM, Lee CH, Shoushtari AN, et al. Tumor mutational load predicts survival after immunotherapy across multiple cancer types. Nat Genet. 2019;51:202–206. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0312-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chalmers ZR, Connelly CF, Fabrizio D, et al. Analysis of 100,000 human cancer genomes reveals the landscape of tumor mutational burden. Genome Med. 2017;9:34. doi: 10.1186/s13073-017-0424-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thangavelu G, Murphy KM, Yagita H, Boon L, Anderson CC. The role of co-inhibitory signals in spontaneous tolerance of weakly mismatched transplants. Immunobiology. 2011;216:918–924. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2011.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kerepesi C, Bakacs T, Moss RW, Slavin S, Anderson CC. Significant association between tumor mutational burden and immune-related adverse events during immune checkpoint inhibition therapies. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2020;69:683–687. doi: 10.1007/s00262-020-02543-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Berner F, Bomze D, Diem S, et al. Association of checkpoint inhibitor-induced toxic effects with shared cancer and tissue antigens in non-small cell lung cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2019 doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.0402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bull JMC. A review of immune therapy in cancer and a question: can thermal therapy increase tumor response? Int J Hyperther. 2018;34:840–852. doi: 10.1080/02656736.2017.1387938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.van Rhoon GC, Franckena M, Ten Hagen TLM. A moderate thermal dose is sufficient for effective free and TSL based thermochemotherapy. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2020.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kleef R, Jonas WB, Knogler W, Stenzinger W. Fever, cancer incidence and spontaneous remissions. NeuroImmunoModulation. 2001;9:55–64. doi: 10.1159/000049008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McCarthy EF. The toxins of William B. Coley and the treatment of bone and soft-tissue sarcomas. Iowa Orthop J. 2006;26:154–158. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nauts HC, McLaren JR. Coley toxins–the first century. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1990;267:483–500. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4684-5766-7_52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Skitzki JJ, Repasky EA, Evans SS. Hyperthermia as an immunotherapy strategy for cancer. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2009;10:550–558. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kempen JH. Appropriate use and reporting of uncontrolled case series in the medical literature. Am J Ophthalmol. 2011;151:7–10.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2010.08.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Carey JC. The importance of case reports in advancing scientific knowledge of rare diseases. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2010;686:77–86. doi: 10.1007/978-90-481-9485-8_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bazett M, Costa AM, Bosiljcic M, et al. Harnessing innate lung anti-cancer effector functions with a novel bacterial-derived immunotherapy. Oncoimmunology. 2018;7:e1398875. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2017.1398875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Harrington K, Freeman DJ, Kelly B, Harper J, Soria JC. Optimizing oncolytic virotherapy in cancer treatment. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2019;18:689–706. doi: 10.1038/s41573-019-0029-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schirrmacher V, van Gool S, Stuecker W. Breaking therapy resistance: an update on oncolytic newcastle disease virus for improvements of cancer therapy. Biomedicines. 2019 doi: 10.3390/biomedicines7030066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.