Abstract

Introduction

A novel coronavirus, designated SARS-CoV-2, caused an international outbreak of a respiratory illness, termed COVID-19 in December 2019. There is a lack of specific therapeutic agents based on evidence for this novel coronavirus infection; however, several medications have been evaluated as a potential therapy. Therapy is required to treat symptomatic patients and decrease the virus carriage duration to limit the communitytransmission.

Methods and analysis

We hypothesise that patients with mild COVID-19 treated with favipiravir will have a shorter duration of time to virus clearance than the control group. The primary outcome is to evaluate the effect of favipiravir on the timing of the PCR test conversion from positive to negative within 15 days after starting the medicine.

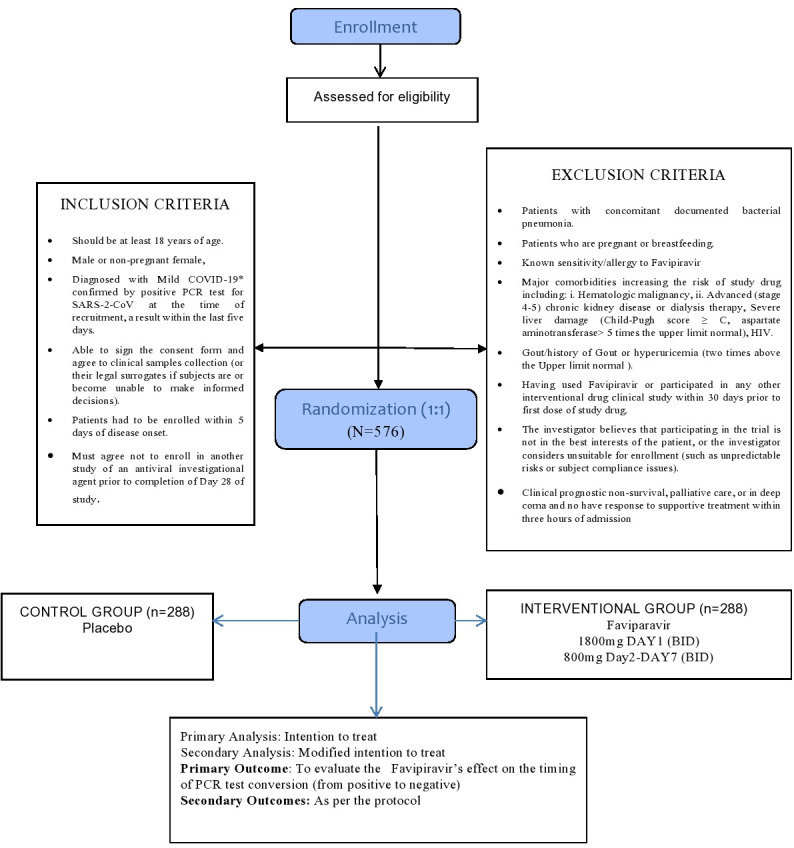

Adults (>18 years, men or nonpregnant women, diagnosed with mild COVID-19 within 5 days of disease onset) are being recruited by physicians participating from the Ministry of National Guard Health Affairs and the Ministry of Health ethics committee approved primary healthcare centres. This double-blind, randomised trial comprises three significant parts: screening, treatment and a follow-up period. The treating physician and patients are blinded. Eligible participants are randomised in a 1:1 ratio to either the therapy group (favipiravir) or a control group (placebo) with 1800 mg by mouth two times per day for the first day, followed by 800 mg two times per day for 4–7 days. Serial nasopharyngeal/oropharyngeal swab samples are obtained on day 1 (5 days before therapy). On day5±1 day, 10±1 day, 15±2 days, extra nasopharyngeal/oropharyngeal PCR COVID-19 samples are requested.

The primary analysis population for evaluating both the efficacy and safety outcomes will be a modified intention to treat population. Anticipating a 10% dropout rate, we expect to recruit 288 subjects per arm. The results assume that the hazard ratio is constant throughout the study and that the Cox proportional hazard regression is used to analyse the data.

Ethics and dissemination

The study was approved by the King Abdullah International Medical Research Centre Institutional Review Board (28 April 2020) and the Ministry of Health Institutional Review Board (1 July 2020). Protocol details and any amendments will be reported to https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04464408. The results will be published in peer-reviewed journals.

Trial registration number

National Clinical Trial Registry (NCT04464408).

Keywords: virology, therapeutics, COVID-19, clinical trials, infectious diseases

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Double-blind randomised placebo-controlled trial.

Large sample size of 576 participants.

Recruiting is challenging as subjects need to be enrolled within 5 days of disease onset.

Challenging remote site initiation visit, protocol training and monitoring activities.

Staff shortage for research due to allocation to other clinical services to address the burden of the pandemic.

Introduction

In December 2019, a novel coronavirus, designated SARS-CoV-2, has caused an international outbreak of respiratory illness termed COVID-19. The WHO declared the epidemic of COVID-19 as a pandemic on 12 March 2020.1 According to a recent Chinese study, ‘about 80% of patients present with mild disease, and the overall case-fatality rate is about 2.3% but reaches 8.0% in patients aged 70–79 years’.2 Mild cases have been found to have viral loads 60-fold less than severe cases. The viral loads of asymptomatic individuals are lower, with possible implications for infectiousness and diagnosis.2 In Saudi Arabia, as of 25 February 2020, 376 000 confirmed cases of the disease have been reported.3 There are no specific therapeutic agents based on substantial evidence for these novel coronavirus infections; however, several medications have been evaluated as a potential therapy. Therapy is required to treat symptomatic patients and decrease the virus carriage duration to limit the community transmission.

Favipiravir was discovered through the screening of a chemical library for antiviral activity against the influenza virus by Toyama Chemical.4 It was approved for medical use in Japan, in 2014, for the treatment of the new or re-emerging pandemic influenza virus infections.4 In February 2020, favipiravir was also approved for the treatment of novel influenza in China and is being studied in the Chinese population as an experimental treatment of the emergent COVID-19.5

Favipiravir is a new type of RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRps) inhibitor, it has activity against the influenza virus. In addition to its anti-influenza virus activity, favipiravir can block the replication of flavi-RNA, alpha-RNA, filo-RNA, bunya-RNA, arena-RNA, noro-RNA and other RNA viruses.6 Favipiravir is converted into an active phosphoribosylated form (favipiravir-ribofuranosyl-5'-triphosphateRTP) in cells and is recognised as a substrate by viral RNA polymerase, thus inhibiting RNA polymerase activity,7 which theoretically can be active against SARS-CoV-2.

There is an urgent need to explore therapeutic options for SARS-CoV-2 to control the pandemic. The selected drug was based on limited evidence clinically and in vitro on the favipiravir’s efficacy in SARS-CoV-2. The medication was listed in many guidelines as a treatment option, and ongoing trials assess its efficacy and safety.4 Japan, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Thailand, Kenya and India have recommended the usage of favipiravir oral therapy in mild to moderate COVID-19 in the treatment guidelines.8–13 Thus, we want to prove the effectiveness of this therapy in treating mild COVID-19 cases.

Research hypothesis

We hypothesise that patients with mild COVID-19 treated with favipiravir will have a shorter duration of time to virus clearance than the control group.

Methods and analysis

Study design

AviMild is a phase III randomised double-blinded placebo-controlled parallel-group multicenter clinical trial to evaluate favipiravir’s safety and efficacy in adults diagnosed with mild COVID-19. The trial involves patients from community settings from different cities in Saudi Arabia with King Abdullah International Medical Research Center (KAIMRC) as the sponsor. The protocol described in this article is V.2.2 approved on 20 November 2020. This randomised controlled trial (RCT) has been developed according to the Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Intervention Trials 2013 statement.14

AviMild RCT will compare favipiravir (experimental arm) to a control arm (placebo). Patients will be randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to both arms. Figure 1 provides an overview of the study design. Any investigational antiviral medication for COVID-19 and other types of antiviral drugs are prohibited. Patients are allowed to continue the medications they were taking before the study, for example, antihypertensive or antidiabetics. The patients are not allowed to participate in other trials as per the study protocol. This is a double-blind study with the treating physician and patients blinded. The study’s recruitment start date was 23 July 2020, and it will continue till reaching the sample size or to December 2021.

Figure 1.

Overview of study.

Study population

A convenience sample of adult patients with mild COVID-19 infection identified as positive by PCR-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 from the community. Patients eligible at the Ministry of National Guard Health Affairs (MNGHA) at Riyadh and Madinah, Saudi Arabia, will be assessed for inclusion in the trial. Additionally, positive patients visiting the Ministry of Health (MOH) Institutional Review Board and Saudi Food Drug Authority approved primary healthcare centres in the regions of Riyadh, Makkah and Madinah will also be assessed for eligibility. Presently there are seven centres, including the sponsor site. MNGHA Riyadh, primary healthcare (PHC)—Mansoura and PHC-Al Urijah Riyadh, MNGHA Madinah and PHC Safiyah—Madinah, King Fahad Hospital-Madinah, King Abdullah Medical City-Makkah.

The sponsor has subscribed an insurance policy covering the sponsor’s own third-party liability as well as the third-party liability of all the investigators involved for the study’s duration.

Inclusion criteria

Patients must be eligible according to the following criteria for enrolment

Should be at least 18 years of age.

Men or nonpregnant women (pregnancy testing is not mandatory. If the patient requests or is not sure, the study team will provide it).

Diagnosed with mild COVID-19* confirmed by positive PCR test for SARS-CoV-2 at the time of recruitment, a result within the last 5 days.

Patients have to be enrolled within 5 days of disease onset.

Exclusion criteria

Patients meeting any of the following criteria will be excluded from trial enrolment:

Patients with concomitant documented bacterial pneumonia established through positive sputum cultures.

Patients who are pregnant or breastfeeding.

Known sensitivity/allergy to favipiravir (if faviparavir was used for COVID-19 in the patient previously for influenza).

-

Major comorbidities increasing the risk of study drug including

Haematologic malignancy.

Advanced (stages 4–5) chronic kidney disease or dialysis therapy.

Severe liver damage (Child-Pugh score C, aspartate aminotransferase-AST >5 times the upper limit).

HIV.

Gout/history of gout or hyperuricaemia (two times above the upper limit normal-ULN).

Having used favipiravir or participated in any other interventional drug clinical study within 30 days before the first dose of study drug (ie, the patient received it for influenza previously).7 The investigator believes that participating in the trial is not in the best interests of the patient or the investigator considers unsuitable for enrolment (such as unpredictable risks or subject compliance issues)

Clinical prognostic nonsurvival, palliative care, or in a deep coma and have no response to supportive treatment within 3 hours of admission.

Hospitalised patients for moderate or severe COVID-19.

Definitions:

-

Mild COVID-19 cases are defined as a patient presenting with a mild illness (absent or mild pneumonia), oxygen saturation >94% at room air and not requiring intensive care unit (ICU) admission.

Mild illness may include uncomplicated upper respiratory tract viral infection symptoms such as fever, fatigue, cough (with or without sputum production), anorexia, malaise, muscle pain, sore throat, dyspnoea, nasal congestion, or headache. Rarely, patients may also present with diarrhoea, nausea and vomiting.

Viral clearance is defined as PCR-negative results.

Randomisation

Eligible participants are randomised in a 1:1 ratio to either the therapy group (favipiravir) or a control group (placebo). The randomisation list is based on computer generated and stratified by clinical site. The patients are randomised, using an electronic case report (e-CRF) form (Research Electronic Data Capture-REDcap) to ensure allocation concealment. The sequence of treatment assignments was determined before the start of the study.

Blinding

The trial is double-blind, meaning that the participants, investigators and other study staff are unaware of the treatment assignment. The sponsor’s investigational drug unit, not part of the study team, holds the information for treatment allocation.

Rationale for study treatment

Favipiravir is a selective and potent inhibitor of influenza viral RNA polymerase. It acts as a purine analogue, which selectively inhibits viral RdRps.

Favipiravir has the characteristic of acting on RNA viruses, including Ebola and coronaviruses, especially novel coronavirus. For the Ebola virus, favipiravir effectively prevented Ebola in mice by 100%, although EC50 (drug concentration was found to reduce viral replication by 50%)~67 µM. A recent in vitro study on clinical isolates of COVID-19 showed that favipiravir has EC50=61.88 µM.15 The dose was chosen based on the drug insert (fabiflu prescribing information) provided for the medication, the studies done in Japan and according to the published studies.13 16

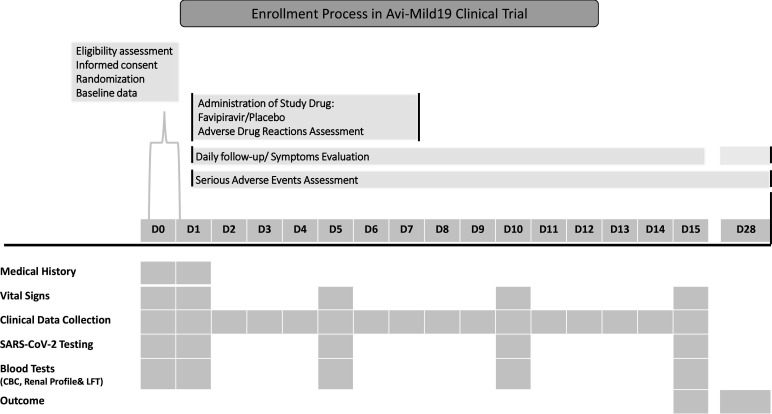

Participant timeline

The study comprises three major parts: screening, treatment and a follow-up period. Each part consists of specified procedures and assessments. The investigator and supporting study team are responsible for documenting all the procedures and assessments in the appropriate source document and the patient e-CRFs (REDcap). All the procedures and assessments will support the safety and validity of the conclusions drawn from the study protocol. Procedures and assessments such as vital signs, laboratory tests follow in-house policies and guidelines. When multiple assessments are taken for variables such as vital signs or laboratory measurements (eg, blood pressure), the value that is out of range or abnormal, that is, higher or lower than the normal range, is documented. Table 1 and figure 2 describe the time schedule for enrolment, intervention, assessments and visits for participants.

Table 1.

Time points for enrolment, intervention and assessment of outcome measure

| Time point study days | Study period and Follow-up | Closeout | |||||||||

| D1 (−1 Day) | D2 | D3 | D4 | D5 | D6 | D7 | D10 | D15 | D21 | D28 | |

| Enrolment and assignment-screening | |||||||||||

| Eligibility assessment | X | ||||||||||

| Informed consent | X | ||||||||||

| Randomisation | X | ||||||||||

| Baseline data* | X | ||||||||||

| Study drug administration-treatment period | |||||||||||

| Favipiravir or placebo | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Adverse effect reaction | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Serious adverse event assessment | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Clinical data collection | |||||||||||

| Symptoms evaluation | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| Laboratory data collection | |||||||||||

| COVID-19 PCR from respiratory sample | x | x | x | x | |||||||

| CBC, renal profile and LFT | x | x | x | x | |||||||

| ECG | x | ||||||||||

CBC-Complete blood count, Liver Function Test-LFT, ECG-electrocardiogram

*Baseline data include the subject’s demographics, comorbid conditions, vital signs, symptoms and epidemiological data collected on the day of enrolment.

Figure 2.

Schedule of enrolment.

Screening/baseline: day -1 to day 1

The site’s delegated personnel checks all positive reported COVID-19 by PCR- confirmed SARS-CoV-2 viral infection at the participating sites. An assessment of the eligibility is performed by the delegated personnel according to the inclusion/exclusion criteria. A possible study participant can be assessed in the first 72 hours of diagnosis regarding eligibility. Once eligible, informed consent is obtained, ata regarding the demographic and epidemiological factors including age, gender, and ethnic group; comorbidities; vital signs and symptoms at presentation; laboratory findings (complete blood count-CBC, liver function, kidney function, potassium, sodium, glucose, and chest X-ray), any hospitalisation during the enrolment period and concomitant medications are collected.

Treatment period: day 1

The treatment intervention is for a maximum of 7 days from randomisation, as follows: favipiravir for 7 days: administer 1800 mg (nine tablets) by mouth two times per day for 1 day, followed by 800 mg (four tablets) two times per day for 4–6 days or equivalent placebo. The medication and placebo were bought from FujiFilm Toyama Chemical and Zhejiang Hisun Pharmaceutical, and it is distributed to all other sites by the sponsor according to enrolment of subjects.

Treatment compliance

Compliance with the study drug is assessed by the study coordinator at each study visit/ follow-up with a phone call. The patient response is recorded in the e-CRF (online supplemental material 1) for any missed dose, the reason for missing doses, any adverse effect and any associated issues beginning from visit 1.

bmjopen-2020-047495supp001.pdf (121KB, pdf)

Follow-up period—days 1–15 and day 28

The follow-up period starts from the second day after randomisation for 14 days, and the research coordinator or the physician follow-up the patient’s health through a phone call. Follow-up of symptoms evaluation should be for 15 days or until the patient reaches the secondary endpoint (resolving symptoms). The patient’s assessment is recorded in the e-CRF. Another follow-up is doneon day 28 days from randomisation. On day 5±1 day, 10±1 day, 15±2 days, extra nasopharyngeal/ oropharyngeal PCR COVID-19 samples are requested by delegated specialist trained clinical personnel, part of the research team, and results are documented in e-CRF. The patients’ follow-up and required laboratory investigations are done while the patient is in the hospital. If the patient is discharged or in outpatient settings, the follow-up evaluation and obtaining specimens are done by delegated personnel in the outpatient clinic or mobile team trained as per study protocol.

Outcome measurements

Endpoints selection is based on objectivity and to present the most reliable assessment for a mild infection. Therefore, viral clearance, which captures the viral shedding duration and possible contagiousness period, reflects the best assessment.

Primary outcome

To evaluate the effect of favipiravir on the timing of the PCR test conversion from positive to negative within 15 days after starting the medicine.

Secondary outcome

To evaluate favipiravir’s effect on clinical recovery. This is assessed by evaluating the duration from the start of treatment (favipiravir or placebo) to the normalisation of fever, respiratory symptoms and relief of cough (or other relevant symptoms at enrolment) that is maintained for at least 72 hours.

Evaluate symptoms severity and the disease course progression in both arms till 28 days after starting the medicine.

To evaluate favipiravir’s effect on the requirement of the use of antipyretics, analgesics or antibiotics within 15 days after starting the medicine.

To evaluate favipiravir’s effect on disease complications within 28 days after starting medicine (hospitalisation, ICU admission or mechanical ventilation).

Evaluate the safety of investigational drug compared with the control arm within 15 days after starting the medicine. This is assessed by allergic reactions, medication intolerance, liver toxicity and hyperuricaemia in subjects.

Participant discontinuation

Premature discontinuation of the trial would be based on the decision of the Data Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) or investigator-initiated based on the following:

Adverse event (AE): clinical or laboratory event, that in the medical judgement of the investigator, for the best interest of the patient are ground for discontinuation.

A major deviation from the protocol: the patient’s findings or conduct failed to adhere to the protocol requirements.

Other reasons: for example, an administrative problem such as termination of study by the sponsor.

Data collection, management and analysis

A research coordinator with expertise in data entry will enter data in a password-protected database (REDcap). All observations and other data pertinent to the clinical investigation will be recorded into the e-CRF. Data are entered and double checked for accuracy. After resolving any discrepancies and a combination of manual and automated data-review procedures, the final data set will be subjected to a quality assurance audit.

A clinical data management review will be performed on all subject data to ensure clinical data quality across all participants and sites. During this review, subject data will be checked for consistency, omissions and any apparent discrepancies. Also, the data will be reviewed for adherence to the protocol. During data analysis, nonidentifiable data will be provided in a password-protected excel sheet. All data are deidentified and coded with a unique number generated by the online data management system REDcap.

Safety and AEs monitoring

All AEs and serious adverse event (SAE) encountered during the clinical study will be reported on the e-CRF. The information to be entered in the e-CRF include:

The time of onset of any AE or the worsening of a previously observed AE.

The specific type of reaction in standard medical terminology.

The duration of the AE (start and stop dates).

-

The severity of the AE. The severity should be rated as:

Mild: discomfort noted, but no disruption of normal daily activity.

Moderate: discomfort noted of sufficient severity to reduce or adversely affect normal activity.

Severe: incapacitating, with the inability to work or perform normal daily activity.

-

The assessment of the relationship of AE to the study medication, that is, according to the definitions below:

Related: with a reasonable causal relationship to the investigational product.

Not related: without a reasonable causal relationship to the investigational product.

Other: in such a case, the investigator’s causality assessment should be specified.

The description of the action taken in treating the AE and/or change in study medication administration or dose.

As far as possible, all investigators will follow-up participants with AEs until the event is resolved or until, in the investigator’s opinion, the event is stabilised or determined to be chronic. Details of AE resolution will be documented in the e-CRF. Any significant changes in AEs will be reported even though the subject has completed the study, including the protocol-required post-treatment follow-up.

Statistical methods

General considerations

This is a randomised, double-blinded study comparing favipiravir tablets to a placebo group to treat subjects with mild SARS-CoV-2 infection. The intention to treat (ITT) analysis will include all subjects randomised ignoring noncompliance, protocol deviations, withdrawal and anything that may take place after randomisation.17 18 The primary analysis population for evaluating both efficacy and safety outcomes will be a modified ITT (MIIT) population and will include all subjects who have been randomised, but will exclude some randomised subjects such as patients who were judged ineligible after randomisation or patients who withdrew consent or who never started the treatment,17 18 study drug (favipiravir tablets or placebo) was started, and the patient did not withdraw consent. These results assume that the hazard ratio (HR) is constant throughout the study and that the Cox proportional hazard regression is used to analyse the data.

Sample size and power considerations

Assumptions and study hypothesis

The current study’s primary hypothesis is H0: HR=1 versus H1: HR ≠1; and HR is the HR of treatment compared with control arm.

-

Time to viral clearance.

In patients with mild COVID-19, 90% of the patients clear the virus by day 10 of onset.1 If we assume an exponential hazard, we estimate the median time of viral clearance in the placebo group to be 8 days.

The exact treatment effect from favipiravir is not known but can be approximated using prior clinical studies. A study comparing favipiravir’s effect to lopinavir/ritonavir on virus clearance has shown a 64% reduction in time to viral clearance in the favipiravir arm.19 To stay on the conservative side, we assume that favipiravir will reduce the median time to virus clearance to 6 days, which is equivalent to HR of 1.33.

-

We further assume that 90% of the control group patients will have viral clearance within 15 days, and 90% will have viral clearance in the treatment arm.

It is anticipated that very few of these subjects will be randomised and not start study treatment (and so be excluded from the primary analysis) or be lost to follow-up (and so have missing data for the primary endpoint). Given certain uncertainties, however, we have included a nominal 10% drop out rate.

Sample size estimation for classical two-arm parallel design

Under the classical two-arm parallel design, a one-sided test of whether the HR is 1 with an overall sample size of 576 subjects (288 are in the control group and 288 in the treatment group) achieve 90% power at a 0.025 significance level when the HR is 1.330.

The sample size re-estimation will be based on the ratio of the planned effect size (1.33) to the observed effect size from the interim analysis according to the following formula:

where ‘a’ is a constant that will be set to 2 and is a number chosen to be slightly larger than the classical sample size per group, which is the planned effect size of 1.33, and E is the observed effect size from the interim analysis.

A detailed statistical analysis plan will be developed before undertaking any comparative analyses of outcomes. The following provides a summary of the approach to analyse the primary endpoint.

Analysis of the primary endpoint

The primary endpoint of the current study is the rate of viral clearance. The number and per cent of subjects who met the endpoint by day 15 of follow-up will be calculated and tabulated. Due to the nature of the data collection (ie, subjects clearance will be observed during specific follow-up time), survival analysis methods for interval-censored data will be used to analyse the data. All results will be reported in HR and the corresponding lower confidence limit and one-sided p value.

Analysis for secondary endpoints

Quantitative variables such as ‘change from baseline in clinical scores’ are expected to have reasonably skewed distributions. They may be subjected to censoring, for example, for subjects in hospital on day 28, compared between randomised arms using nonparametric tests (Wilcoxon’s test).

The analysis of the other secondary endpoints will use a proportional odds model with an indicator variable for randomised treatment. The Wald test will generate a p value comparing treatments and the estimated proportional OR comparing treatments with associated 95% CI.

The analysis of AE data will primarily be descriptive based on MedDRA coding of events. The proportion of subjects experiencing an SAE and the proportion experiencing a Grade.

Three or higher AEs will be compared between the randomised arms using Fisher’s exact test.

For enrolled subjects who were not randomised (ie, screen failures) or randomised but did not receive the treatment, the final analysis will detail safety (deaths and SAEs) and reasons they were not randomised or did not receive treatment, respectively.

Data monitoring

This committee will be independent of the sponsor with relevant therapeutic and biostatistical experience to allow for the ongoing review of data from this trial. A DSMB will be convened to monitor the trial’s unblinded data focusing mainly on assuring that the study follows the protocol correctly and monitoring the safety issues related to the trial. The DSMB will meet when AEs trigger study pausing/stopping criteria are triggered. The DSMB has no competing interests.

The current study will have a single interim analysis, which will occur after the recruitment and follow-up of 40% of the total number of subjects (ie, 230 subjects). The interim analysis is designed to test for early stopping for futility or efficacy and sample size re-estimation.20 The interim analysis and final analysis will be based on the sum of the stage-wise p value. Table 2 describes the interim analysis testing boundaries.

Table 2.

Interim analysis and sample size re-estimation

| Alpha1=0.01 | Stop the trial for early efficacy if the interim analysis p value <0.01 |

| Beta1=0.25 | Stop the trial for futility if the interim analysis p value ≥0.25 |

| Alpha 2=0.1832 | Declare the trial significant if the sum of the interim analysis and final stage p values <0.1832 |

Frequency and procedures for auditing trial conduct:

The investigator will allow representatives of the regulatory authorities (Saudi Food & Drugs Authority) to conduct an audit anytime they request it. The regulatory authorities are independent of the sponsor.

Discussion

During the Ebola virus disease outbreak, the JIKI trial illustrated an improved survival rate in patients with a moderate to high viral load with favipiravir.21 Similarly, Bai et al’s study proved a significant decline in viral load with favipiravir in patients with a moderate viral load at baseline.22 These findings support the role of favipiravir in the viral load reduction. Since the homology of gene sequences of SARS-CoV-2 and SARS was over 90%, it is expected that the intervention of antiviral drugs in patients with COVID-19 will likely improve or shorten the time to viral clearance.23 The reduction in time to viral clearance is chosen as the endpoint based on the above evidence. Therefore, viral clearance, which captures the viral shedding duration and possible contagiousness period, reflects the best assessment. Several published trials have studied similar endpoints as our study due to their clinical significance. A study of 80 patients with COVID-19 compared favipiravir to lopinavir/ritonavir. The study reported a shorter viral clearance time for the favipiravir arm versus the lopinavir/ritonavir arm median 4 days (IQR: 2.5–9) versus 11days (IQR: 8–13), p<0.001). The multivariable Cox regression showed that favipiravir was significantly (p=0.026) associated with faster viral clearance. Additionally, the timing of the antiviral therapy reached near significance (p=0.055).19 Furthermore, it was superior to Arbidol in having a higher 7-day clinical recovery rate in patients with COVID-19 and a more significant reduction in fever and cough.15 A Japanese observational study assessed the safety and efficacy of favipiravir. The median duration of therapy was 11 days, with reported clinical improvement rates at 7 and 14 days which were 73.8% and 87.8%, 66.6% and 84.5% and 40.1% and 60.3% for mild, moderate and severe disease, respectively.24 A prospective, randomised, open-label trial of early versus late favipiravir in hospitalised patients with COVID-19, chose the primary endpoint of viral clearance by day 6. The secondary endpoint was a change in viral load by day 6. Additionally, exploratory endpoints included time to defervescence and resolution of symptoms.25 A trial from Russia enrolled 60 patients (40 on favipiravir and 20 on supportive care) with the primary endpoint as viral elimination. The secondary endpoints were defervescence and reverse transcription (RT)-PCR negativity.13 Finally, a phase 3, open-label, randomised, multicenter study (Glenmark Pharmaceuticals) was initiated in India. The primary endpoint was time until the cessation of oral shedding of the SARS-CoV-2 virus.26

According to a study by Jones et al, there were 630 registered trials for COVID-19 on the clinicaltrials.gov website by 1 May 2020. Most of these trials were from Europe, the USA, China and other Asian countries. Additionally, all the trials on the drugs or biologics (218) are studying drugs such as hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine (88), azithromycin (53) and 25 trials assessed convalescent plasma, lopinavir/ritonavir, stem cell treatments and tocilizumab.27

Another study reported 201 trials registered with the US registry and the WHO clinical trials registry platform. Of these, 93.5% studied a drug intervention. From the total trials, 49.8% were from China, 37.8% USA, accounting for 87.6% of both the countries studies. From the 201 trials, only 11 trials are being done on favipiravir.28 As of 23 July 2020, there are 32 studies registered on clinicaltrials.gov to assess this drug’s utility in the management of COVID-19 (3 completed, 12 recruiting).29

Many clinical trials conducted in China, Japan, Russia and India had an open-label design, which leads to reporting biased results.13 19 25 26 Recently a study was done in India with favipiravir in mild to moderate COVID-19 cases. This was a randomised, open-label study and a sample size of only 150 patients.30 There are certain limitations reported in this study, which were due to the small sample size. The HR reported was small, and due to the study’s open-label nature, it may have been subjected to potential bias. This study’s primary endpoint was confounded due to interpretation issues with RT-PCR positivity and its lack of correlation with the clinical cure.30

A systemic review and meta-analysis of favipiravir-reported evidence showing potential benefits of this drug in clinical and imaging improvement after treating patients with COVID-19. Therefore, there is a need for additional randomised, double-blind clinical trials to form a definite opinion about the rationale to use this drug. There were several drawbacks to the studies that have already been published, such as nonrandomised design, small sample sizes and different durations of treatment, different dosage regimes and lack of blinding.31

In our study, we adopted the design double-blind, placebo-controlled randomised study, which provides the best evidence of causation.32 Randomised double-blind placebo control studies (RDPCS) are regarded as the ‘gold standard’ of epidemiologic studies. They are employed to illustrate superiority, equivalence and noninferiority. Well-designed RDPCS gives the most robust possible evidence of causation. The benefits of randomisation are (1) it avoids selection bias that may happen if either the physician or the patient decides the treatment, (2) it removes most confounding by all known and unknown factors as it prevents an association between the treatment and any other known or unknown factors. Blinding with randomisation evades reporting bias as no one is aware of the treatment; hence all treatment groups will be treated the same. The use of placebo as control leads to the placebo effect where the person on placebo will think that they are taking the actual treatment, which leads them to feel better or respond to it due to wishful thinking. The presence of placebo control will assist in comparing the drug’s effectiveness against the placebo’s effectiveness.33–35

There are currently only two countries (KSA and Kuwait) from the Middle East with ongoing Favipiravir trials with a placebo comparator.29 Our study is the first trial registered from the Middle East region to date funded by the government of KSA. Our study’s sample size is 576 subjects, second to Kuwait’s trial (780) from the presently ongoing favipiravir trials.29

Limitations

Numerous challenges are expected during this trial. The trial is ongoing now during restricted travel time, and hospitals restricted nonessential personnel entry. Protocol training, site initiation visits and monitoring visits will be performed remotely in many sites. The research team will be assigned to other clinical services, and many members require extra effort. Also, study team member’s sicknesses or unprotected exposure to patients with COVID-19 strained research resources. Many sites may encounter inadequate supplies of personal protective equipment and trial-related supplies. The study is prone to certain biases due to the design, such as noncompliance, withdrawals after randomisation and attrition/losses to follow-up.

Ethics and dissemination

This study is conducted in compliance with the protocol and by the laws and regulations of King Abdullah International Medical Research Centre Ethics Committee (KAIMRC IRB) and the Ministry of Health Ethics Committee (MOH IRB). The date of approval for the first version wwas 28 April 2020, and for the protocol version, V.2.2 is 25 November 2020. The KAIMRC IRB approved this study with protocol number RC20/220. The study applies the principles established in the Declaration of Helsinki. The participants sign a written informed consent form (online supplemental material 2) before the first assessment and data is collected by delegated personnel. Contact details of the principal investigator are provided to the patients for queries and concerns. Patients are free to withdraw from the study at any time without any consequences regarding their standard clinical care. Any change or addition to this protocol requires a written amendment approved by the sponsor and the investigators. Before implementation, the investigators will transmit all major amendments to the Ethics Committees, examining the initial protocol. The investigators will transmit a copy of the Ethics Committee’s opinion to the sponsor. The investigators will notify all minor amendments to the Ethics Committee that examined the initial protocol. All amendments will be reported to the clinical trials registration site.

bmjopen-2020-047495supp002.pdf (1.4MB, pdf)

Trial status

This trial began on 23 July 2020. On 3 March 2021, 191 patients have been enrolled.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge principal investigators for all sites (alphabetical order): Ali Tolba, Hanan Turkistany, Mohannad Bahlaq, Saad Alshahrani, Sanaa Al Rehily, Zied Ghaifer Ali. We thank all staff involved in data monitoring. We thank Dr. Susanna Wright from KAIMRC for editing our manuscript.

Footnotes

Twitter: @Favipiravir in adult

Contributors: MB, HA, MAb, KS, AM, HA, MAl, EM, AAlo, AAls, AMA, SA, MA-J and AAlh participated in study design and protocol development. MB, AM, KA, KS, AAls are involved in subject recruitment and follow-up plan. MH, OA, AAlh and MB participated in the development of statistical analysis plan. KS, MB, AAls and HA contributed to manuscript preparation. KS and MB contributed to review and manuscript submission.

Funding: This trial was funded by King Abdullah International Research Centre, KSA (grant number RC20/220/R).

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

References

- 1.Liu Y, Yan L-M, Wan L, et al. Viral dynamics in mild and severe cases of COVID-19. Lancet Infect Dis 2020;20:656–7. 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30232-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese center for disease control and prevention. JAMA 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Totoal coronavirus cases in Saudi Arabia [online]. Dover, Delaware, USA: Worldometer. Available: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/country/saudi-arabia/ [Accessed 25 Feb 2021].

- 4.Shiraki K, Daikoku T, Favipiravir DT. Favipiravir, an anti-influenza drug against life-threatening RNA virus infections. Pharmacol Ther 2020;209:107512. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2020.107512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li G, De Clercq E. Therapeutic options for the 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV). Nat Rev Drug Discov 2020;19:149–50. 10.1038/d41573-020-00016-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Delang L, Abdelnabi R, Neyts J. Favipiravir as a potential countermeasure against neglected and emerging RNA viruses. Antiviral Res 2018;153:85–94. 10.1016/j.antiviral.2018.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Furuta Y, Komeno T, Nakamura T. Favipiravir (T-705), a broad spectrum inhibitor of viral RNA polymerase. Proceedings of the Japan Academy series B, physical and biological sciences 2017;93:449–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centre For Disease Control and Prevention . Interim clinical guidance for management of patients with confirmed coronavirus disease (COVID-19) [online], 2020. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/clinical-guidance-management-patients.html [Accessed 18 Jan 2021].

- 9.Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: Ministry of Health . COVID-19. Coronavirus disease guidelines [online], 2020. Available: https://www.moh.gov.sa/en/Ministry/MediaCenter/Publications/Pages/covid19.aspx [Accessed 18 Jan 2021].

- 10.India: Medical Education and Drugs Department Government of Maharashtra . Compendium of guidelines, instruction and standard operative procedures for covid-19 [online], 2020. Available: https://www.maharashtramedicalcouncil.in/Files/MEDD%20Compendium%204th%20Edition%20Volume%204.pdf [Accessed 18 Jan 2021].

- 11.Ratanarat R, Sivakorn C, Viarasilpa T, et al. Critical care management of patients with COVID-19: early experience in Thailand. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2020;103:48–54. 10.4269/ajtmh.20-0442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Russia: MOH of the Russian Federation . Interim guidelines. Prevention, diagnostics and treatment of a new coronavirus infection (COVID-19) [online], 2020. Available: https://static-1.rosminzdrav.ru/system/attachments/attaches/000/050/116/original/28042020_%D0%9CR_COVID-19_v6.pdf [Accessed 18 Jan 2021].

- 13.Joshi S, Parkar J, Ansari A, et al. Role of favipiravir in the treatment of COVID-19. Int J Infect Dis 2021;102:501–8. 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.10.069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chan A-W, Tetzlaff JM, Altman DG, et al. Spirit 2013 statement: defining standard protocol items for clinical trials. Ann Intern Med 2013;158:200–7. 10.7326/0003-4819-158-3-201302050-00583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen C, Huang J, Cheng Z. Favipiravir versus arbidol for COVID-19: a randomized clinical trial. medRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Favipiravir . Report on the deliberation results; Japan: Toyama chemical, evaluation and licensing division PaFSBMoH, labour and welfare; 2014 March 4 report 2014.

- 17.Heritier SR, Gebski VJ, Keech AC. Inclusion of patients in clinical trial analysis: the intention-to-treat principle. Med J Aust 2003;179:438–40. 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2003.tb05627.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gupta SK. Intention-to-treat concept: a review. Perspect Clin Res 2011;2:109–12. 10.4103/2229-3485.83221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cai Q, Yang M, Liu D. Experimental treatment with Favipiravir for COVID-19: an open-label control study. engineering (Beijing, China) 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Kumar A, Chakraborty BS. Interim analysis: a rational approach of decision making in clinical trial. J Adv Pharm Technol Res 2016;7:118–22. 10.4103/2231-4040.191414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sissoko D, Laouenan C, Folkesson E, et al. Experimental treatment with Favipiravir for Ebola virus disease (the JIKI trial): a historically controlled, single-arm proof-of-concept trial in guinea. PLoS Med 2016;13:e1001967. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bai C-Q, Mu J-S, Kargbo D, et al. Clinical and Virological Characteristics of Ebola Virus Disease Patients Treated With Favipiravir (T-705)-Sierra Leone, 2014. Clin Infect Dis 2016;63:1288–94. 10.1093/cid/ciw571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. New Eng J Med 2020;382:727–33. 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.James MI. Preliminary report of favipiravir observational study in Japan released. online, 2020. Available: News-Medical.net

- 25.Doi Y, Hibino M, Hase R, et al. A prospective, randomized, open-label trial of early versus late Favipiravir therapy in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2020;64:e01897–20. 10.1128/AAC.01897-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Singh P. A clinical study on Favipiravir compared to standard supportive care in patients with mild to moderate COVID-19 [online]. Cochrane COVID-19 study register2020. Available: http://www.ctri.nic.in/Clinicaltrials/pmaindet2.php?trialid=43504

- 27.Jones CW, Woodford AL, Platts-Mills TF. Characteristics of COVID-19 clinical trials registered with ClinicalTrials.gov: cross-sectional analysis. BMJ Open 2020;10:e041276. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-041276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mehta HB, Ehrhardt S, Moore TJ, et al. Characteristics of registered clinical trials assessing treatments for COVID-19: a cross-sectional analysis. BMJ Open 2020;10:e039978. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-039978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.US National Institue of Health . Listed COVID 19 studies [online], 2020. Available: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov [Accessed 26 Nov 2020].

- 30.Udwadia ZF, Singh P, Barkate H, et al. Efficacy and safety of favipiravir, an oral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase inhibitor, in mild-to-moderate COVID-19: a randomized, comparative, open-label, multicenter, phase 3 clinical trial. Int J Infect Dis 2021;103:62–71. 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.11.142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shrestha DB, Budhathoki P, Khadka S, et al. Favipiravir versus other antiviral or standard of care for COVID-19 treatment: a rapid systematic review and meta-analysis. Virol J 2020;17:141. 10.1186/s12985-020-01412-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barton S. Which clinical studies provide the best evidence? The best RCT still trumps the best observational study. BMJ 2000;321:255–6. 10.1136/bmj.321.7256.255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oleckno WA. Essential epidemiology: principles and applications. Long Groove, IL: Waveland Press, Inc, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hulley S, Cummings S, Browner W. Designing clinical research. 503 walnut street. Philadelphia, PA: Williams and Wilkins. A Walters Kluwer business Lippincot, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Manja V, Lakshminrusimha S. Epidemiology and clinical research design, part 1: study types. Neoreviews 2014;15:e558–69. 10.1542/neo.15-12-e558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2020-047495supp001.pdf (121KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-047495supp002.pdf (1.4MB, pdf)