Abstract

Purpose of Review

The immunosuppressive agent cyclosporine was first reported to lower daily insulin dose and improve glycemic control in patients with new-onset type 1 diabetes (T1D) in 1984. While renal toxicity limited cyclosporine’s extended use, this observation ignited collaborative efforts to identify immunotherapeutic agents capable of safely preserving β cells in patients with or at risk for T1D.

Recent Findings

Advances in T1D prediction and early diagnosis, together with expanded knowledge of the disease mechanisms, have facilitated trials targeting specific immune cell subsets, autoantigens, and pathways. In addition, clinical responder and non-responder subsets have been defined through the use of metabolic and immunological readouts.

Summary

Herein, we review emerging T1D biomarkers within the context of recent and ongoing T1D immunotherapy trials. We also discuss responder/non-responder analyses in an effort to identify therapeutic mechanisms, define actionable pathways, and guide subject selection, drug dosing, and tailored combination drug therapy for future T1D trials.

Keywords: Immune therapy, Clinical trial, Type 1 diabetes, Prevention, Treatment, Autoimmunity

Introduction

Immunotherapy for type 1 diabetes (T1D) has been the subject of more than three decades of investigation directed toward the prevention and treatment of this disease. While it is not yet feasible to persistently halt autoimmunity, considerable progress has been made in our ability to predict T1D, understand underlying immune mechanisms, and slow the rate of β cell decline. Longitudinal clinical trials [1–8] (Table 1) together with cross-sectional investigation of human pancreas (e.g., the Network for Pancreatic Organ donors with Diabetes (nPOD) [22, 23]) are reshaping our understanding of the natural history of T1D and human pancreas pathology. Indeed, these studies have laid the groundwork for a new phase of clinical trials that will, for the first time, enable a previously unprecedented capacity for precision medicine harnessing genetic and peripheral biomarkers to target patient-specific immune and β cell pathways. Herein, we review known and emerging biomarkers of T1D pathogenesis, their role in guiding immunotherapy, lessons garnered regarding the functional mechanisms of past and current intervention trials, and ways to focus and optimize future cutting-edge treatment modalities.

Table 1.

Longitudinal follow-up in infants and early prevention trials in individuals with high genetic risk for T1D

| Trial | Subjects | Intervention | Endpoint(s) | Clinical and mechanistic outcomes | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Longitudinal studies | |||||

| BABYDIAB | Offspring of parent with T1D | N/A | AAb seroconversion, T1D onset | 4% developed AAb by age 2 years; IAA first AAb, followed by GADA; IgG1 dominant | [1] |

| T1D Prediction and Prevention (DIPP) | Neonates and siblings with high-risk HLA from general population | N/A | AAb seroconversion, T1D onset | 6% developed AAb by age 2 year; 46% of AAb+ children reverted to AAb-; IA-2A epitope specificity can convey increased risk or protection | [2, 9, 10] |

| Diabetes Autoimmunity Study in the Young (DAISY) | Neonates with high-risk HLA from general population and FDR | N/A | AAb seroconversion, T1D onset | 10-year risk of progression to T1D: 15% with 1 AAb, 70% with 2 AAb, and 74% with 3 AAb; age of AAb seroconversion major determinant of age of T1D progression | [3] |

| The Environmental Determinants of Diabetes in the Young (TEDDY) | Neonates with high-risk HLA from general population and FDR | N/A | AAb seroconversion, T1D onset | 5-year risk of progression to T1D: 11% with 1 AAb, 36% with 2 AAb, and 47% with 3 AAb; IAA+ and GADA+ progress equally to T1D but IAA occurs first at a younger age | [4, 5] |

| T1D TrialNet Pathway to Prevention (TN01, formerly Natural History Study) | Children and adults with AAb (FDR, general population) | N/A | T1D onset | AAb by RIA and ECL (ECL-IAA, ECL-GADA), along with younger age, number of AAb+, HbA1c, OGTT associated with increased risk of T1D; ECL positivity add specificity for high aifinity epitopes | [6, 11] |

| Primary prevention | |||||

| BABYDIET | Neonates with high-risk HLA, FDR | Gluten-free diet in the first year of life | AAb seroconversion, T1D onset | No difference in rate of AAb seroconversion or T1D development | [1] |

| Trial to Reduce IDDM in the Genetically at Risk (TRIGR) | Neonate with high-risk HLA, FDR | Weaning to hydrolyzed casein-based formula (no foods with bovine protein) | AAb seroconversion, T1D onset | No difference in rate of AAb seroconversion or T1D development; no effect of breastfeeding seen; exposure to intact cow’s milk protein not critical in the development of T1D | [7] |

| Finnish Dietary Intervention Trial for the Prevention of T1D (FINDIA) | Neonate with high-risk HLA | Insulin-free bovine formula | AAb seroconversion | Pilot demonstrated reduced AAb development in the first 3 years of life; higher antibody titer to bovine insulin in cow’s milk group compared with bovine free | [8] |

| Nutritional Intervention to Prevent T1D (TrialNet NIP) | Neonate with high-risk HLA, FDR | Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) supplementation | Cytokine reduction | Reduced IL-1β, IL-12p40, TNF-α at one but not all time points following in vitro high-dose LPS stimulation; no difference in IL-6 and IL-10 between groups | [12] |

| Primary Oral/Intranasal INsulin Trial (Pre-POINT) | FDR, high-risk HLA | Oral insulin | Mechanistic immune response; safety | Higher insulin-specific serum IgG, saliva IgA (mucosal response), and CD4+ T cell proliferation with FOXP3+CD127− Treg in response to insulin dose escalation Clinical efficacy not assessed |

[13] |

| Secondary prevention (stages 1–2 T1D) | |||||

| European Nicotinamide Diabetes Intervention Trial (ENDIT) | Children and adults with ICA+, FDR | Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) | T1D onset | No effect on T1D progression; presumed action via inhibition of cell death pathways but no mechanistic analyses | [14] |

| T1D Prediction and Prevention (DIPP) | Children with high-risk HLA, ≥2 AAb | Intranasal insulin | T1D onset | No delay or prevention of T1D; no change in IAA titers, high IAA affinity remained unchanged, insulin-specific IgG3 and IgA (only few subjects) increased in the treated group Progressors had insulin-specific IgGl and IgG3 levels | [2, 15, 16] |

| Diabetes Prevention Trial Type 1 (DPT-1) | Relative with T1D, ICA+, IAA+ | SQ or IV insulin Oral insulin | T1D onset | Overall, no effect on rate of T1D progression or incidence (delayed T1D progression in subjects with high IAA titers (≥ 80 nU/mL) during therapy only) Non-progressors had lower IAA and ICA titers, fewer had IA-2A, predominantly ethnic/racial minorities, older age, higher FPIR, higher serum C-peptide |

[17–19] |

| T1D TrialNet Oral Insulin | Relative with T1D, mIAA+ plus 1 other AAb | Oral insulin | T1D onset | Overall, no effect on rate of T1D progression or incidence (delayed T1D onset in subjects with low FPIR) | [20] |

| Diabetes Prevention-Immune Tolerance (DIAPREV-IT) with GAD-Alum | Children GADA+ plus ≥ 1 other islet AAb | SQ injections of GAD-Alum (Diamyd®) | T1D onset | Failed to delay or prevent T1D Elevated GADA levels |

[21] |

AAb, autoantibodies, FDR, first-degree relative, ECL, electorchemiluminescenc

Autoimmune Pathogenesis of T1D

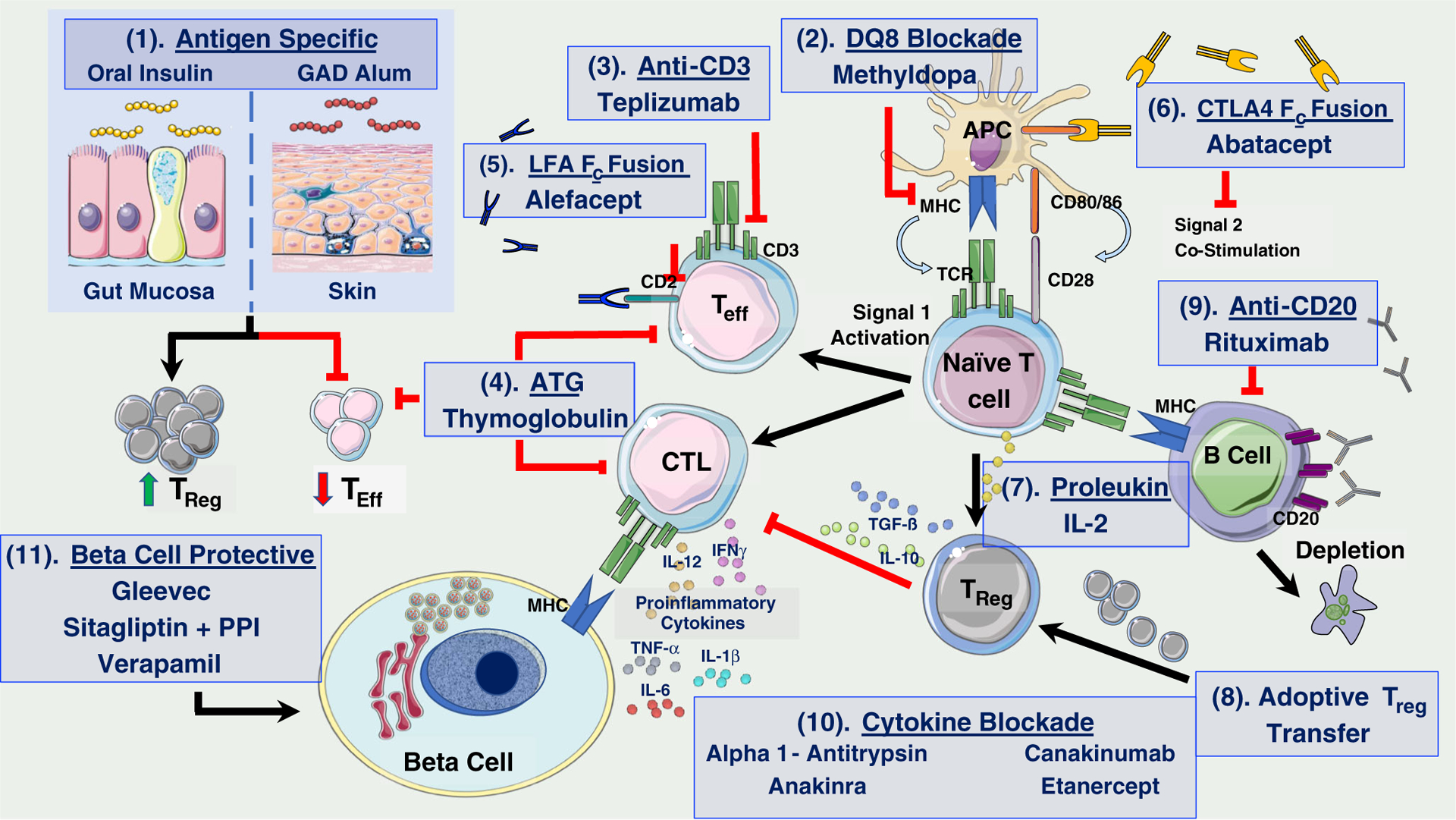

There is a general consensus that T1D is a complex and heterogeneous disease, yet debate remains as to the driving etiology behind disease progression. That said, the presence of insulin- and GAD-specific autoreactive lymphocytes in peripheral blood and the confirmation of T and B cell infiltrates in human islets before and persisting after disease onset clearly support an autoimmune pathogenesis [24–26, 27••, 28, 29]. Diabetogenic lymphocytes are thought to initiate a cascade that bypasses normal regulatory checkpoints resulting in epitope and antigenic spreading, the emergence of multiple autoantibodies (AAb), and progressive β cell destruction (Fig. 1), with various steps throughout this process likely permitted or aggravated by T1D risk loci.

Fig. 1.

Pathways involved in T1D pathogenesis and targeted therapies tested to date. Although prior trials with immunotherapies have not resulted in remission of T1D, numerous trials have been successful in transiently altering the landscape of islet autoimmunity yielding valuable mechanistic lessons that can help guide future therapeutic intervention. Harnessing the tolerogenic power of the gut or formulations for peripheral immunization provides the basis for antigen-specific therapies, such as oral insulin and GAD-alum, which aim to induce antigen-specific CD4+CD25highFOXP3+ Tregs and, secretion of tolerogenic cytokines resulting in reduced islet-specific Teff and CTL responses (1). Several immunotherapeutics are directed at depleting autoreactive T cells and/or thwarting their activation, which may lead to a chronic exhaustion of Teffs and induction of tolerance. These include methyldopa (2), teplizumab (anti-CD3) (3), ATG (4), Alefacept (LFA-3/Fc fusion protein targeting CD2) (5), and Abatacept (CTLA-4/Fc fusion protein blocking CD80/86–CD28 interaction) (6). Stimulation of Tregs has been the subject of several trials. Low-dose IL-2 preferentially sustains Treg expansion (7), while replenishing the Treg compartment through adoptive cell transfer may serve to restore immunoregulation in T1D (8). B cell depletion via rituximab (anti-CD20) seeks to impede B cell-mediated antigen presentation and activation of diabetogenic T cells (9). Proinflammatory cytokine blockade may act to prevent deleterious effects on β cell survival and function in the islet microenvironment (10), while β cell-specific therapies that promote survival may avert loss of β cell mass and function (11). (This figure is original but was created, in part, with adapted art images from Servier Medical Art, from Creative Commons user license Attribution 3.0 Unported [CC BY 3.0]; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/)

Genetics as the Basis for Understanding Disease Mechanisms

T1D incidence is 15–20 times higher in first-degree relatives (FDR) of people with T1D compared with unaffected relatives [30, 31]. Additionally, T1D concordance in monozygotic twins is about 65% by age 60 versus ~ 6–7% between dizygotic twins and non-twin siblings [31–33]. Of the 57 currently identified loci associated with T1D risk (curated at http://www.immunobase.org) [34, 35], the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) locus predominates risk (~ 50%) with all other loci contributing minimally (odds ratios (OR), ~ 1.10–2.38) [36–38]. The HLA is the most polymorphic locus in the human genome, and haplotypes ranging from highly susceptible to highly protective have been reviewed extensively [30, 39]. Notably, the HLA DR4-DQ8 and DR3-DQ2 allele types confer the most risk with OR of 11 and 3.6, respectively, and an additive OR of ~ 40 in individuals carrying both haplotypes [31, 39]. Generally, the pathogenic mechanisms by which HLA mediates T1D are thought to revolve around antigen presentation, but whether it is due to central tolerance/thymic selection or T cell activation in the periphery is not fully elucidated. Although intensely studied, the pathogenic mechanisms by which HLA and non-HLA genes collectively mediate T1D are not conclusively known. Several individual loci do have proposed mechanisms (reviewed in [30, 31]) with the preponderance of candidate genes having functional immunological roles, including genotype:phenotype associations impacting T cell receptor (TCR), co-receptor, and cytokine signaling pathways. Hence, genetics not only influence who will develop T1D but also which etiologies or T1D “endotypes” (i.e., subtypes of the condition defined by distinct pathophysiological mechanisms encompassing a person’s clinical features and response to treatment [27••, 40]) are manifested by individuals following development of islet autoimmunity, altogether resulting in disease heterogeneity.

Initiation of islet autoimmunity is associated with HLA, where children up to 6 years of age carrying DR4-DQ8 tend to seroconvert to insulin AAb (IAA), while those carrying DR3-DQ2 tend to seroconvert to GAD65 AAb (GADA) [41]. Therefore, interventions designed to prevent islet autoimmunity rely heavily on genetic risk for cohort stratification. To date, this has largely been done by identifying individuals with FDRs affected by T1D who also carry one or more of the high-risk HLA loci [42]. However, since the vast majority of individuals with T1D have no family history of T1D, such strategies miss large swaths of subjects that eventually progress to T1D. Conversely, relying on HLA alone to stratify the general population (as opposed to family-based) cohorts identifies too many false positives having insufficient specificity for T1D progressors [30, 43, 44]. Influences for non-HLA genes on progression from multiple AAb to clinical disease have also been shown [45–47]. Additionally, a recent genome wide association study (GWAS) described novel associations between age at T1D diagnosis and the 6q22.33 chromosomal region encoding protein tyrosine phosphatase receptor kappa (PTPRK) and thymocyte-expressed molecule involved in selection (THEMIS), both of which serve critical roles in thymic T cell development [48]. To assist in cohort stratification, cumulative genetic risk score (GRS) models measuring both HLA and non-HLA risk have been constructed via logistic regression algorithms. These GRS models demonstrate that the inclusion of non-HLA loci into a cumulative risk score increase model accuracy for classification of subjects as patients or controls [31, 49]. Further, they are able to predict progressors [49, 50], discern T1D from other forms of diabetes [51, 52], and describe the prevalence of T1D onset in individuals over 30 years of age [53]. Recently, it was shown in the prospective TEDDY study cohort that a GRS model can improve the identification of infants with >10% risk of developing multiple AAb by age 6 years versus the population risk of 0.4% [4]. With further refinement, validation, and longer follow-up, GRS models have the potential to serve as standard clinical tools to greatly enhance the feasibility of primary prevention trials, particularly as genotyping costs continue to decline making population-based screenings feasible. Importantly, widespread adoption will depend on the discovery of interventions specifically targeting disease-associated pathways.

Serological and Cellular Biomarkers Support an Autoimmune Pathogenesis

Serological Biomarkers

Seroconversion to multiple AAb positivity is currently the most reliable predictor of T1D progression [54] (Table 2). Radioimmunoassays (RIA) are the gold standard for detection of the major autoantibodies: IAA, GADA, insulinoma-associated protein 2 AAb (IA-2A), and zinc transporter 8 AAb (ZnT8A) [55–58], and augmentation of current T1D GRS models with RIA-based AAb assays or multiplexed electrochemiluminescence (ECL) assays shows promise and should prove useful in identifying subjects who are most likely to benefit from early immunotherapeutic intervention [50, 89].

Table 2.

Biomarkers of type 1 diabetes risk and progression

| Pathway | Biomarker | Assay | Analyte(s) measured | Considerations | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Humoral autoimmunity | AAb | RIA | IAA, GADA, IA-2A, ZnT8A |

|

[55–58] |

| ELISA | GADA, IA-2A, ZnT8A |

|

[59] | ||

| ECL | IAA, GADA |

|

[11, 60–62] | ||

| Cellular autoimmunity | Autoreactive T cells | Multimer staining | Autoreactive T cells specific for the interrogated antigen |

|

[63, 64] |

| ELISpot | Spots corresponding to single cells secreting cytokines in response to autoantigen stimulation |

|

|||

| AIRR analysis | TCR CDR3 sequences |

|

[24, 63] | ||

| Autoreactive B cells | Flow cytometry | Peripheral blood |

|

[65, 66] | |

| β Cell dysfunction or death | Elevated fasting PI:C ratio | Dual-label time-resolved fluorescence immunoassay | Proinsulin and C-peptide |

|

[67–74] |

| Elevated cfDNA unmethylated INS | SYBR green qRT-PCR; TaqMan qRT-PCR; NGS of 6 contiguous methylation sites within the INS promoter | cfDNA unmethylated INS |

|

[75–85] | |

| miRNA | miRNA qRT-PCR miRNA microarray | miRNA contained in exosomes and microvesicles as well as free miRNA |

|

[86–88] |

AAb, autoantibodies; RIA, radioimmunoassay; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbant assay; ECL, electrochemiluminescence; IAA, insulin autoantibody; GADA, GAD65 autoantibody; IA-2A, insulinoma-associated protein-2 autoantibody; ZnT8A, zinc transporter 8 autoantibody; IASP, Islet Autoantibody Standardization Program; PI:C ratio, serum proinsulin to C-peptide ratio; cfDNA, cell-free DNA; NGS, next-generation sequencing; miRNA, microRNA; TCR, T cell receptor; AIRR, adaptive immune receptor repertoire; CDR3, complementarity determining region 3

Given the mounting evidence for intrinsic β cell stress in T1D pathophysiology [90], biomarkers measuring β cell dysfunction or death, such as elevated fasting serum proinsulin: C-peptide ratio [67–74] and elevated unmethylated INS cell-free DNA (cfDNA) [75–80] (Table 2), may also improve screening and inform therapeutic interventions aimed at interdicting autoimmunity (reviewed below), promoting β cell survival/expansion/replacement (e.g., verapamil [91], stem cell therapy [92]), reducing β cell stress (e.g., etanercept [93]), and restoring β cell function (e.g., Gleevec [94], sitagliptin [95]). The short half-life of cfDNA in circulation is a notable limitation, but studies investigating methylation patterns in other β cell genes are underway, offering the potential to combine these assays into methylation signature panels [96, 97]. Furthermore, circulating unmethylated INS cfDNA and/or PI:C ratio could serve as outcome measures. As but one example from a clinical trial, a significant decline in unmethylated INS cfDNA was observed at 1 year in teplizumab-treated subjects versus placebo [76]. Given that unmethylated INS cfDNA and/or PI:C ratio biomarkers assess β cell death and dysfunction in real-time, combining these assays with immunophenotyping and large-scale-omics may guide future therapeutic selections.

Detection of β cell stress in those with high GRS and/or AAb positivity may facilitate identification of subjects who will likely benefit from drugs aimed at preventing effector T cell (Teff) activation or co-stimulation [98•, 99–101, 102•, 103–105, 106•, 107] alone or in conjunction with therapies promoting β cell survival/replication (e.g., small molecules studied in vitro and in vivo [108]). Finally, various microRNAs (miRNAs) are dysregulated in the circulation of T1D patients [86, 109] and have been shown to regulate β cell function (reviewed in [110]; Table 2). While still developmental in terms of application to clinical trials, exosomes as well as free miRNAs represent a new class of biomarkers to potentially improve the prediction of T1D and differentiate disease etiologies.

Cellular Biomarkers

Novel methods for isolation, expansion and characterization of islet-infiltrating lymphocytes are offering new insights on T cell clones with specificity for neoepitopes, such as defective ribosomal products (DRiPs) and hybrid insulin peptides (HIPs) as well as those previously identified [111–117]. A multitude of data on the diversity of the T cell repertoire as well as information regarding evolution of clonal expansion within the islet microenvironment [24, 63, 117] provide promising avenues for epitope discovery, functional analysis of islet-reactive T cells, and development of novel biomarkers of autoreactivity (Table 2). As next-generation sequencing (NGS) continues to become more affordable, adaptive immune receptor repertoire (AIRR) analyses may emerge as a robust tool to identify predictive biomarkers of T1D; moreover, AIRR may guide development of tailored antigen-specific therapies, TCR-redirected regulatory T cells (Treg) [118, 119], and drugs targeting T cell autoreactivity.

Clinical Interventions and Mechanisms of Action

Prevention

Prevention of T1D is predicated on early identification of high-risk subjects and application of an effective intervention prior to disease progression. In support of this notion, T1D was recently reclassified, with consensus support from the JDRF, Endocrine Society and American Diabetes Association, to include three distinct stages, two of which are “preclinical.” Specifically, stage 1 T1D is defined by the presence of two or more AAb and normal glucose metabolism, while stage 2 is defined by AAb positivity with impaired glucose metabolism. Stage 3 T1D is defined by the onset of clinical or symptomatic disease (Table 3) [120]. Over the past 25 years, most prevention efforts have targeted antigen-based or generally regarded as safe (GRAS) interventions. However, given the lack of efficacy noted with these approaches, more potent immune-altering agents are now being considered.

Table 3.

Classification of type 1 diabetes stages related to autoimmunity and dysglycemia [120]

| Features | Symptom presence | |

|---|---|---|

| Stage 1 | ≥ 2 AAb, normoglycemia | Asymptomatic |

| Stage 2 | ≥ 2 AAb, dysglycemia | Asymptomatic |

| Stage 3 | Meets biochemical criteria for diabetes | Typically symptomatic |

Primary Prevention

GRAS supplements administered to genetically at-risk infants prior to the development of autoimmunity were the targets of the T1D TrialNet NIP and ENDIT trials [12, 14] while TRIGR, BABYDIET, and FINDIA attempted to modulate or eliminate early exposures to potentially antigenic components (i.e., gluten or bovine insulin in infant formula [8, 121, 122]) (Table 1). Sadly, none of these trials showed efficacy in delaying or preventing T1D [8]. That said, neither antigen-specific nor immunomodulatory therapies have been tested in the primary prevention setting (before the presence of islet AAb). Notably, the Pre-POINT study, which only had a mechanistic outcome [13], recently utilized high-dose oral insulin therapy in high-risk HLA, AAb-negative FDRs and elicited a mucosal anti-insulin IgA response, an IgG response, and promoted CD4+FOXP3+CD127− Treg cells. These data support the notion that exposure of the intestinal epithelium to T1D-specific autoantigens prior to seroconversion and initiation of islet autoimmunity may induce tolerance via TGF-β and IL-10 producing DCs that subsequently drive Treg responses to the same tolerized antigens [13, 123]. Recent and ongoing analyses of longitudinal data generated from the DIPP and TEDDY cohorts are unveiling pre-seroconversion biomarkers (e.g., gut microbiome, metabolomics, lipidomic, and proteomic profiles) of eventual T1D progression that might improve our ability to determine candidates for early antigen specific or immunomodulatory therapy [124–128].

Secondary Prevention

Formulations of islet autoantigens have been tested as “vaccinations” in secondary prevention in an effort to induce tolerance through promotion of Treg and downregulation of autoreactive Teff. Specifically, oral or intranasal preparations of insulin and insulin peptides are thought to encounter the gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) or mucosa and with repeated exposure, induce insulin-specific Treg [17] capable of suppressing insulin-reactive Teff and CTLs via secretion of regulatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-10, IL-4, TGF-β, etc.), IL-2 competition, and through cell contact-dependent mechanisms (Fig. 1) [118, 129–133].

Insulin

The prevention of spontaneous and adoptive cell transfer of autoimmune diabetes in rodent models [123, 134–137] through exposure to oral insulin led the way for several large clinical trials using insulin as a primary target-antigen through oral and intranasal routes of administration (efficacy and mechanistic outcomes are detailed in Table 1 and reviewed in [138]). Unfortunately, no individual study has been able to meet primary endpoints to delay or prevent T1D in those at risk [13, 17, 18, 20, 139]. That said, these trials do suggest that oral or intranasal insulin may elicit tolerogenic immune responses capable of delaying T1D in specific subsets of individuals [17, 18, 20]. Specifically, of subjects with high IAA titers, those with loss of first phase insulin response demonstrated delayed progression and potential benefit from oral insulin [20]. In DIPP, those likely to progress had higher levels of insulin-specific IgG1 and IgG3 [15], potentially necessitating addition of a synergistic therapy when that mechanistic outcome is seen. As such, the ongoing development of biomarkers that prospectively identify these subgroups may allow primary prevention trials of oral insulin alone or in conjunction with pre-conditioning agents (e.g., anti-thymocyte globulin (ATG), anti-CD3, or Abatacept).

GAD

Similar to insulin, the use of GAD bound to an aluminum hydroxide adjuvant (GAD-alum) has been unsuccessful in preventing progression to T1D in at-risk children with multiple AAb [21]. New-onset intervention trials, which also failed to preserve β cell function, demonstrated GAD-specific immune responses including elevated GAD AAb levels [140, 141], increased GAD-induced secretion of IL-5, IL-10, IL-13, IL-17, IFNγ, and TNF-α, but not IL-6 or IL-12 by PBMC [140, 142], increased CD4+CD25highFOXP3+ Treg cell frequency [143], reduced CD4+CD25+ T cell frequency [143], as well as increased FOXP3 and TGF-β mRNA expression in whole PBMC [140, 142] (Table 1). Interestingly, in the new-onset trial, a subgroup of clinical responders (defined as < 10% loss of AUC C-peptide from baseline) exhibited higher GAD-induced secretion of Th2-associated cytokines (IL-5 and IL-13) 1 month after treatment (Fig. 1) [142, 143]. These findings again suggest that biomarkers capable of selecting responders could support future GAD-directed trials especially when considered in combination with agents having complementary/synergistic mechanisms of action (MOA).

T Cell-Directed Therapy

Tcells play an essential role in disease progression in the NOD mouse and agents have been used to both target Teff populations and prevent the acquisition of autoreactive memory T cells in human T1D. TrialNet’s teplizumab (anti-CD3) (NCT01030861) and abatacept (CTLA-4 Ig) (NCT01773707) secondary prevention trials in at-risk relatives (stage 1 or 2 T1D) are currently ongoing. The mechanisms at play in each of these trials are detailed further below and in Fig. 1, but T cell-directed therapies are a logical step in the prevention arena to interdict before critical loss of β cells.

Intervention in New-Onset or Established T1D with Evidence Toward Efficacy

Because functional β cell mass declines precipitously during the first year or longer following T1D onset (stage 3) [144, 145], numerous therapeutics have been trialed in recently diagnosed patients [98•, 99–101, 102•, 103, 105, 106•, 107, 146–162]. While an in-depth discussion of each interventional approach is beyond the scope of this review, we have summarized recent interventional approaches in Table 4 and their proposed mechanisms in Fig. 1). Below, we review selected interventional approaches that are most likely to be guided by the application of novel biomarkers.

Table 4.

Mechanisms targeted and clinical response in trials for treatment of stage 3 (new onset) T1D

| Clinical trial intervention | Cell subsets and cytokines affected by therapy | Presumed targeted pathways | Clinical trial outcome and respondersa | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cyclosporin + methotrexate (placebo-controlled, not blinded) | No change in WBC, PMN, lymphocyte count | No mechanistic analyses available, drugs showed efficacy in other autoimmune diseases | 12-month HbA1c lower and daily insulin dose lower (4/7 off insulin temporarily) | [146] |

| Rituximab (anti-CD20) (placebo-controlled, partial blinding) (TN05) | CD19+ depletion, reduced IgM levels | Altered antigen presentation by B cells, reduced cytokines in pancreas or pLN | 12-month AUC C-peptide higher, daily insulin dose lower, HbA1c lower; younger age tended toward greater response | [147, 148] |

| Teplizumab (anti-CD3) (placebo-controlled, multiple dosing regimens, blinded) (Protégé Trial) | Transient decrease in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, transient increase in FOXP3+CD8+ T cells | Transient margination and apoptosis of T cell subsets; preferential depletion of Teff | 24-month AUC C-peptide higher (secondary endpoint), 5% off insulin at 12 months; initial primary endpoint (< 0.5 u/kg/day insulin and HbA1c < 6.5% at 1 year) not met; younger age with more effect, in addition to lower insulin use and HbA1c and higher C-peptide at baseline | [102•, 103] |

| Otelixizumab (chimeric anti-CD3) (placebo-controlled, partial blinding) | Placebo-treated subjects with a decrease in CD4+ and increase in CD8+ between baseline and 6 months compared with steady values in treated subjects | Downregulation of pathogenic T cells and upregulation of Treg | High-dose (48–64 mg total ChAglyCD3); lower daily insulin dose over 48 months (especially younger subjects); changed primary endpoint from C-peptide AUC (glucagon clamp) due to low compliance, though 80% higher than placebo; no difference in HbA1c | [149] |

| Otelixizumab (chimeric anti-CD3) (placebo-controlled, blinded) (DEFEND Trial) | Transient lymphocyte reduction (36.3% relative to baseline); transient reduction in CD4+CD25+FOXP3+ T cells during dosing but no difference following; decreased CD3/TCR saturation on CD4+ T cells | Downregulation of pathogenic T cells and upregulation of Treg | Low-dose (3.1 mg otelixizumab); no difference from placebo in 12-month AUC C-peptide, HbA1c, or insulin dose | [150, 151] |

| Thymoglobulin (ATG) (placebo-controlled, partially blinded) (START Trial) | CD4+ and CD8+ T cells depleted and remain below baseline at 24 months with partial reconstitution (Tn, Tcm, Treg); Tem not significantly depleted; IL-10, CRP, SAA elevated early | Precipitous fall in most T cell subsets leading to unfavorable Treg/Tem ratio that persisted for 24 months leading to an inability to preserve C-peptide | High-dose ATG (6.5 mg kg−1); no difference in AUC C-peptide at 12 and 24 months (less decline in older subjects, post hoc analysis significant at 24 months); no difference in daily insulin dose or HbA1c; one treated subject insulin free at 24 months | [100, 101] |

| ATG + G-CSF | Decreased CD3/CD8, CD19/CD8, CD4/CD8 ratios (up to 24 months); elevated FOXP3+Helios+ Tregs; no difference in Tn/Tcm, CD45RO, or CD45RA Tregs | Less severe T cell depletion with faster recovery than high-dose ATG with preservation of Tregs (presumed synergism with G-CSF but only 1 treatment group) | Low-dose ATG (2.5 mg kg−1) + G-CSF in established disease (4–24 months); pilot study; 12-month (and 24) AUC C-peptide not significant (p = 0.05); no difference in HbA1c or daily insulin dose; responders were older, on less baseline insulin | [98•, 99] |

| ATG + G-CSF (placebo-controlled, blinded) (TN19) | Decreased CD4+ T cells and CD4/CD8 ratio; preserved CD8+ T cells in both ATG and ATG + G-CSF groups | Low-dose ATG (and ATG + G-CSF) led to preservation of Tregs; but without significance in the group with added G-CSF (synergism not apparent) | 3 arms (low-dose ATG alone, ATG + G-CSF, placebo) in new onset disease; 12-month AUC C-peptide higher in ATG alone compared with placebo; HbA1c reduced in both ATG and ATG + G-CSF groups; no difference in daily insulin dose | [107] |

| Abatacept (CTLA-4/Fc fusion protein) (placebo-controlled, blinded) (TN09) | Decreased CD4+ Tcm (CD45RO+CD62L+); increased CD4+ Tn (CD45RO-CD62L+); decreased Treg (CD4+CD25high) | Reduction in central memory CD4 T cells and increase in naïve cells was seen in C-peptide preservation | 24-month AUC C-peptide higher; HbA1c lower; no difference in daily insulin use; new onset disease; drug given over 24 months | [105, 106•] |

| Ex vivo-expanded autologous CD4+CD127lo/−CD25+polyTregs (open-label, dose-escalation) | Increased expression of CD25, CTLA-4, and LAP in expanded Treg; decrease in CD56hiCD16lo NK; increased percentage of CCR7+ Treg | Increased function of expanded Tregs (in vitro suppression assays); increased IL-2-driven pSTAT5 response; decrease in NK cells | Primary endpoints of safety and feasibility were met; transient increases in Tregs in recipients, retention of Treg FOXP3+CD4+CD25hiCD127lo phenotype; study not powered for conclusions on secondary metabolic endpoints (C-peptide); small study with 4 dosing cohorts | [163] |

| Autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant (AHSCT) (single-arm, open-label) | Lower CD4+Tem, higher CD8+ Tcm, and increased CD8+CD28−CD57+ T cells in those with longer insulin remission; no change in autoreactive CTL frequency | Temporary reestablishment of self-tolerance; expansion of immunoregulatory T cells, inhibition of effector memory T cells, and lower baseline autoreactive CTLs led to higher metabolic responsiveness to AHSCT | Short-term (< 3.5 years) insulin remission in 10 subjects, long-term (≥ 3.5 years) insulin remission in 11 subjects; AUC C-peptide increased from baseline to 48 months (longer in long-term responders); lower autoreactive CD8+ T cell at baseline led to higher C-peptide post-AHSCT | [164] |

| Alefacept (LFA-3/Fc fusion protein) (placebo-controlled, blinded) (T1DAL Trial) | Decreased CD4+, CD8+ T cells; CD4+: increased % Tn, decreased Tcm, Tem; CD8+: decreased Tn, Tcm, no difference Tem; no change in Tregs | Targeting of memory T cells with sparing of Tregs and Tn; impairing CD2-mediated costimulation | 12-month 2-h AUC C-peptide showed no difference (primary endpoint); 4-h AUC C-peptide higher; lower insulin use; no difference in HbA1c | [152] |

| Alpha-1-antitrypsin (acute phase reactant) (open label, dose escalation) (RETAIN) | Decreased IL-6 and IL-1β | Inhibition of pro-inflammatory cytokines and the NF-κB pathway | Primary endpoints of safety and tolerability were met; secondary endpoints: 2-h AUC C-peptide, HbA1c, insulin usage were studied but no placebo group for comparison | [155, 165] |

| Canakinumab (anti-IL-1 mAb) and Anakinra (IL-1R antagonist) (placebo-controlled, blinded) | Decreased PMN; decreased expression of IL-1 regulated genes | Anti-IL-1 affects gene expression/transcription; ontological analyses suggest reduced inflammation and increased Treg activity | 12- and 9-month results, from the two trials, respectively, showed no difference in AUC C-peptide; no difference in HbA1c or insulin dose | [156, 157] |

| Proleukin (IL2) (placebo-controlled, blinded, phase 1/2) | Dose-dependent increase and persistence in CD4+FOXP3+, CD8+FOXP3+ Treg numbers, and proportions | Expansion and activation of Treg | Low-dose IL-2 at three concentrations and placebo group; primary outcome change in Treg from days 1 to 60; significant increase above placebo at all 3 doses in proportion of Treg | [153, 154] |

| Etanercept (anti-TNF-α) (placebo-controlled, blinded, pilot) | N/A | Blocking TNF-α is suspected to decrease local inflammation, lymphocytic invasion and cytokine-mediated β cell death | 6-month AUC C-peptide was higher, HbA1c and insulin dose were lower | [93] |

| Sitagliptin + lansoprazole (DPP-4 inhibitor + PPI) (placebo-controlled, blinded) (REPAIR-T1D) | N/A | Suspected promotion of β cell growth and protection from insulitis | Within 6 months of diagnosis; 12-month primary outcome 2-h AUC C-peptide after covariate analysis showed no difference; no difference in HbA1c or insulin use | [95] |

| Verapamil (calcium-channel blocker) (placebo-controlled, blinded) | N/A | Inhibition of β cell apoptosis through decreased thioredoxin-interacting protein (TXNIP) expression and preservation of glucose homeostasis | Primary endpoint AUC C-peptide significantly increased at 3 and 12 months compared to baseline; lower increase in insulin requirements; fewer hypoglycemic events (secondary endpoints) | [91] |

ATG, anti-thymocyte globulin; G-CSF, granulocyte-colony stimulating factor; TN, Type 1 Diabetes TrialNet; Treg, regulatory T cell; Tn, naïve T cell; Tcm, central memory T cell; Tem, effector memory T cell; CRP, C-reactive protein; SAA, serum amyloid A

Responder definition varies with trial

Mechanisms of Action of T Cell Targeting Agents

Emerging data suggest that immunotherapeutics aimed at depleting Teff and CTL (i.e., anti-CD3, ATG, Alefacept) harbor more intricate immunomodulatory mechanisms than originally postulated. For instance, responders to Teplizumab (anti-CD3) exhibited a partial T cell exhaustion phenotype that was not terminally differentiated but characterized by expression of KLRG1, TIGIT, and EOMES [166••]. Following Alefacept treatment, Rigby et al. observed a temporary downregulation of Tem with their recovery after 24 months corresponding to a decline in C-peptide parallel to that of placebo [167•]. Similarly, mechanistic data derived from the ATG/G-CSF pilot trial revealed increased frequencies of FOXP3+Helios+ Tregs with concomitant augmentation of PD-1 expression for up to 18 months following treatment, which correlated with C-peptide AUC in responders [98•]. Further, this combinatorial therapy increased CD16+CD56high NK cells, a phenotype associated with immunoregulatory and tolerogenic properties [98•, 168, 169].

Treg Promoting Agents and Cellular Therapies

IL-2 signaling plays a non-redundant role in Treg development, serving as a prime therapeutic target to augment Treg responses in T1D (Fig. 1). While initial attempts at targeting this pathway using high dose IL-2 and rapamycin transiently induced Treg expansion, this trial was plagued by deleterious effects on β cell function as a result of toxicity induced by rapamycin and concomitant expansion of NK cells and eosinophils [170]. More recently, safety and dose-finding investigations of low-dose IL-2 regimens have shown more promise, preferentially sustaining Tregs with no detrimental effects on glucose metabolism [153, 154].

As a logical progression in the immunotherapy space, adoptive cell therapies (ACT), such as those used in settings of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) [171–175], are under study in T1D [118, 163, 176] (Fig. 1). Approaches under preclinical or clinical investigation include mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) [177–180], embryonic stem cells (ESCs) [181], induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) [182, 183], and Treg cellular therapy (reviewed in [118]) derived from peripheral blood, bone marrow, adipose tissue, or umbilical cord blood (UCB) [176]. An ongoing multicenter trial using autologous peripheral blood-derived Tregs (NCT02691247) has completed enrollment, and trials of ex vivo expanded autologous UCB-derived Tregs in new-onset T1D patients are being planned [176]. From these trials, we may be able to derive responders and non-responders to autologous Treg ACT, whether due to low numbers or poor function of Tregs Mechanistic studies and biomarker discovery efforts may drive our ability to generate tailored Treg therapies. For example, in individuals with low Treg numbers, ex vivo Treg expansion and reinfusion may be sufficient, whereas for those with impaired Treg function, lentiviral transfection or CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing may be used to restore Treg signaling or stabilize FOXP3 expression and suppressive capacity. Moreover, suppression via chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) technology or TCR redirected Treg “avatars” [119] may be most effective at targeting Tregs to the organ of interest and avoiding off-target immune suppression.

Trimolecular Targets

The presentation of islet auto-antigenic peptides via MHC molecules to the TCR is an essential driver for activation of autoreactive T cells [117]. Thus, blockade of this interaction has been the subject of intense investigation. Use of molecular docking screens led to the identification of methyldopa as a therapeutic for preventing recognition of proinsulin peptides presented in the context of the high-risk HLA-DQ8 molecule [184]. Methyldopa is now under investigation in at-risk individuals (NCT03396484), and studies are ongoing to identify blocking agents for other autoantigen-HLA combinations.

Advancing β Cell Survival and Function

Protecting β cells from inflammatory onslaught represents an additional avenue for T1D intervention. The cytokine milieu within the local islet microenvironment not only serves to direct the crosstalk between innate and adaptive cells, but these soluble factors may have direct deleterious effects on pancreatic β cell function and survival. As such, functional blockade of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6, IL-1β, IL-12, and TNF-α, may serve to curtail local islet inflammation and cytokine-induced β cell death [93, 155–157, 185]. Additionally, a trial has been initiated testing the utility of Gleevec (imatinib mesylate), which is well known for the treatment of chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML), as a β cell restorative therapy (NCT01781975). This tyrosine kinase inhibitor has been shown to improve β cell function in NOD β cells (by inhibiting negative regulation of insulin secretion) and insulin sensitivity in CML patients with type 2 diabetes [94, 186]. Moreover, through inhibition of Bcr-Abl, Gleevec is able to mitigate downstream activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling, endoplasmic reticulum stress, and cytokine-induced β cell death [187, 188]. Finally, stem cell differentiation into insulin-producing cells might eventually facilitate β cell replacement without the need for islet isolation from HLA compatible organ donors [92, 189, 190]. Best implemented in combination with immunomodulatory treatment, stem cell derived β-like cells would be particularly useful in patients with low stimulated C-peptide production (indicative of functional β cell mass), but challenges associated with terminal differentiation, phenotyping and function have slowed progress toward their clinical application (recently reviewed [191]).

Drug Response and Responder/Non-responder Analyses

Subgroups of T1D patients identified based on lymphocytic profiles in peripheral blood and within the pancreatic islets suggested that B cell or Tcell-targeting immunotherapies may have utility in specific cohorts [27••]. Indeed, in the past decade, clinical trials have demonstrated transient efficacy in new-onset T1D and enabled the designation of subjects as clinical (i.e., preservation of baseline AUC C-peptide) or immunological responders (i.e., alteration of the immunophenotype) and non-responders. The rituximab (anti-CD20) and teplizumab/otelixizumab (anti-CD3) trials tended toward greater clinical response in younger subjects [102•, 103, 147–149]; whereas, the opposite was seen for the ATG (responders were 22–35 years old) and pilot ATG/G-CSF studies (responders’ mean age was 27.5 years) (Table 4) [98•, 99–101]. In the Abatacept trial, there was a lack of effect seen in HLA-DR3-negative subjects (unrelated to age) [104], supporting the use of genetic determinants to guide treatment selection. Outliers also provide unique opportunities to understand mechanism. For example, from the ATG/GCSF study in established T1D, four subjects maintained C-peptide above baseline beyond 24 months and mechanistically, were found to have a transient increase in FOXP3+Helios+ Treg at 6 months [98•]. Conversely, rare placebo-treated subjects demonstrate higher C-peptide at study endpoint than baseline [99, 100] suggesting a need for sufficiently powered studies to determine the clinical, genetic, and immunologic features of these cases. Because definitions of “responder” and the type/complexity of data collected vary between trials, data can rarely be compared across studies. Moreover, not all individuals will respond to the same MOA suggesting that varied disease endotypes may be at play. Interestingly, some consistencies were found across trials: (1) subjects with higher baseline C-peptide perform better and (2) the eventual outcome after cessation of therapy (i.e., gradual decline in β cell function parallel to the placebo group) seems inevitable with current modalities. Altogether, these findings support initiatives to intervene early in the disease, to re-treat at intervals based on immune and metabolic biomarkers, and to implement combination therapies targeting multiple MOA in T1D. On the other hand, the observation that many patients maintain detectable levels of stimulated C-peptide for at least a few years after diagnosis suggests that meaningful benefit may also be possible even at later time points [144], and indeed, a recent study enrolled patients who had disease for up to 2 years [98•, 99].

To better understand how to provide personalized and efficacious care, the field may benefit from further defining distinct endotypes to predict how subjects with T1D will respond to different immune therapies. The currently available mechanistic data can be used to pick the next therapeutic agent(s), beginning with small trials and mechanistic endpoints. The establishment of a database and structured analytical pipeline for higher order analyses and future cross-trial comparisons is needed. With this, there is a need to standardize a “minimum mechanistic analysis” (e.g., human immunophenotyping by flow cytometry, GRS, functional and epigenetic analyses of polyclonal and antigen-specific T and B cells) in addition to assays for β cell function/survival to facilitate post hoc analyses, potential discovery of unexpected MOAs, and to eventually enable individualized biomarker-informed treatment decisions.

Optimizing Timing and Combinatorial Therapies

Lessons from Immunotherapy/Combo Therapy in Other Autoimmune Diseases and Cancer

To move immune therapy for T1D forward, there is a need to adopt lessons learned from the treatment of other autoimmune diseases. For example, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA), and rheumatoid arthritis (RA) not only have standardized clinical and mechanistic outcomes, but also apply combination therapies, re-treatment for continued immune modulation, as well as therapies based on endotype determination (e.g., poly-articular JIA versus mono-articular JIA responds to different therapeutic interventions) [192–194]. Cancer immunotherapy protocols similarly employ a mechanism-driven approach based on genetic and other biomarkers (e.g., Gleevec and its specific targeting of the Bcr-Abl chimeric oncogene named the Philadelphia chromosome responsible for over 90% of CML cases) [195]. Finally, transplant medicine, where immunosuppressive therapies were first developed, now involves immunomodulatory ACT to prevent and treat GVHD [196] supporting current trials of Treg ACT in T1D. Low-dose IL-2 has also been used in GVHD with promising results [197, 198].

Through advances in composite genetic risk models that incorporate HLA and minor risk alleles [51, 52, 199], it may be possible to not only predict T1D but also identify specific pathway targets with sufficient confidence to enact more precise and personalized interventions prior to the development of autoimmunity or β cell dysfunction/destruction. For example, given the known associations between specific HLA haplotypes and first AAb reactivities [200, 201], we may be able to select autoantigen-specific or epitope-blocking therapies (e.g., methyldopa) to prevent initial seroconversion or T cell activation in certain high-risk individuals. We expect that a pre-treatment risk assessment with genetic and circulating biomarkers will estimate a person’s likelihood of response with a given therapeutic MOA (e.g., Teff, Treg, B cell, β cell, antigen-specific, or combinations thereof) to inform tailored T1D therapies in the future.

Treatment Timing and Potential Need to Re-dose

Optimizing the timing of intervention(s) may be just as important as drug selection for optimizing clinical efficacy. For example, while rituximab demonstrated only transient benefit in a subset of new-onset T1D patients [148], early B cell depletion in pre-stage 1 disease may effectively prevent B cell-T cell interactions required for autoimmune activation and islet infiltration [202–204]. Along those lines, antigen-specific therapies, such as insulin and GAD, provided in pre-stage 1 to those with high-risk DR4 and DR3 haplotypes, respectively, may prevent the expansion/activation of early autoreactive clonotypes. Moving forward, we must identify the best biomarkers to direct therapies for each stage of disease (pre-stage 1 T1D though established T1D).

While no permanent alteration to the immune environment has occurred following immunotherapy in T1D, a delay in C-peptide loss by 9 or more months has been reported with B cell and T cell targeting agents [98•, 99, 105, 106•, 107, 147, 148]. We expect durable preservation of C-peptide may require retreatments with immunomodulatory agents, potentially with additional agents aimed at inducing durable tolerance to autoantigens. Hence, the safety and efficacy of repeated dosing and/or sequential agent administration needs to be determined, and immune and metabolic biomarkers are needed to establish the appropriate timing for re-treatment, though waning of the tolerogenic T cell profile may serve as a starting point.

Conclusions

Although the prior trials have not resulted in complete remission of T1D, numerous trials have been successful in transiently altering the landscape of islet autoimmunity yielding valuable mechanistic lessons that can help guide future therapeutic intervention. The amalgamation of genetic predisposition and environmental factors alter the equilibrium between immunogenic and tolerogenic responses. Whether T1D occurs through defects in central tolerance, a breakdown in peripheral tolerance, viral infection, altered microbiome, dietary exposures, molecular mimicry, or the combination [205, 206] remains to be determined, but there is a clear autoimmune signature marked by autoreactive T and B cell clones that precedes the decline in β cell mass resulting in hyperglycemia [24, 27••, 207]. Ultimately, the common goal for each immunotherapy is to restore adaptive immune balance by promoting not only Treg but potentially driving T cell exhaustion and reducing autoreactive Teff and Tem activities. We expect that this will be best achieved by early detection and intervention, along with the use of combination or sequential treatment with antigen-specific, β cell-directed, immunomodulatory, and/or cellular therapies. There is no one size fits all in the treatment of autoimmune disease, and that is especially true of T1D. New and emerging biomarkers will allow for targeted approaches in those with T1D who share common pathogenic mechanisms.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Mark A. Atkinson for his comments and critical review of the manuscript.

Funding

This effort was supported by grants from the NIH (P01 AI42288 and R01 DK106191 to TMB; F30 DK105788 to BNN), the JDRF (post-doctoral fellowships to LMJ (3-PDF-2018–579-A-N) and DJP (2-PDF-2016–207-A-N)), the Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust, and the McJunkin Family Charitable Foundation.

Abbreviations

- T1D

Type 1 diabetes

- nPOD

Network for Pancreatic Organ donors with Diabetes

- AAb

Autoantibodies

- FDR

First-degree relatives

- HLA

Human leukocyte antigen

- OR

Odds ratios

- TCR

T cell receptor

- IAA

Insulin autoantibody

- GADA

GAD65 autoantibody

- GWAS

Genome wide association study

- GRS

Genetic risk score

- RIA

Radioimmunoassays

- IA-2A

Insulinoma-associated protein 2 autoantibody

- ZnT8A

Zinc transporter 8 autoantibody

- ECL

Electrochemiluminescence

- cfDNA

Cell-free DNA

- Teff

Effector T cell

- miRNAs

MicroRNAs

- DRiPs

Defective ribosomal products

- HIPs

Hybrid insulin peptides

- NGS

Next-generation sequencing

- AIRR

Adaptive immune receptor repertoire

- Treg

Regulatory T cells

- GRAS

Generally regarded as safe

- GALT

Gut-associated lymphoid tissue

- ATG

Anti-thymocyte globulin

- GAD

Alum GAD bound to an aluminum hydroxide adjuvant

- MOA

Mechanisms of action

- ACT

Adoptive cell therapies

- GVHD

Graft-versus-host disease

- MSC

Mesenchymal stem cells

- ESCs

Embryonic stem cells

- iPSCs

Induced pluripotent stem cells

- UCB

Umbilical cord blood

- CAR

Chimeric antigen receptor

- CML

Chronic myelogenous leukemia

- IBD

Inflammatory bowel disease

- JIA

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis

- RA

Rheumatoid arthritis

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Laura M. Jacobsen, Brittney N. Newby, Daniel J. Perry, Amanda L. Posgai, Michael J. Haller, and Todd M. Brusko declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as:

• Of importance

•• Of major Importance

- 1.Hummel S, Ziegler AG. Early determinants of type 1 diabetes: experience from the BABYDIAB and BABYDIET studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;94:1821S–3S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haller MJ, Schatz DA. The DIPP project: 20 years of discovery in type 1 diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes. 2016;17(Suppl 22):5–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steck AK, Johnson K, Barriga KJ, Miao D, Yu L, Hutton JC, et al. Age of islet autoantibody appearance and mean levels of insulin, but not GAD or IA-2 autoantibodies, predict age of diagnosis of type 1 diabetes: diabetes autoimmunity study in the young. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:1397–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonifacio E, Beyerlein A, Hippich M, Winkler C, Vehik K, Weedon MN, et al. Genetic scores to stratify risk of developing multiple islet autoantibodies and type 1 diabetes: a prospective study in children. PLoS Med. 2018;15:e1002548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steck AK, Vehik K, Bonifacio E, Lernmark A, Ziegler AG, Hagopian WA, et al. Predictors of progression from the appearance of islet autoantibodies to early childhood diabetes: the environmental determinants of diabetes in the young (TEDDY). Diabetes Care. 2015;38:808–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Battaglia M, Anderson MS, Buckner JH, Geyer SM, Gottlieb PA, Kay TWH, et al. Understanding and preventing type 1 diabetes through the unique working model of TrialNet. Diabetologia. 2017;60:2139–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.TRIGR Study Group, Akerblom HK, Krischer J, et al. The trial to reduce IDDM in the genetically at risk (TRIGR) study: recruitment, intervention and follow-up. Diabetologia. 2011;54:627–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vaarala O, Ilonen J, Ruohtula T, Pesola J, Virtanen SM, Härkönen T, et al. Removal of bovine insulin from cow’s milk formula and early initiation of beta-cell autoimmunity in the FINDIA pilot study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166:608–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kimpimäki T, Kulmala P, Savola K, Kupila A, Korhonen S, Simell T, et al. Natural history of beta-cell autoimmunity in young children with increased genetic susceptibility to type 1 diabetes recruited from the general population. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:4572–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoppu S, Härkönen T, Ronkainen MS, et al. IA-2 antibody isotypes and epitope specificity during the prediabetic process in children with HLA-conferred susceptibility to type I diabetes. Clin Exp Immunol. 2006;144:59–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fouts A, Pyle L, Yu L, Miao D, Michels A, Krischer J, et al. Do Electrochemiluminescence assays improve prediction of time to type 1 diabetes in autoantibody-positive TrialNet subjects? Diabetes Care. 2016;39:1738–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chase HP, Boulware D, Rodriguez H, Donaldson D, Chritton S, Rafkin-Mervis L, et al. Effect of docosahexaenoic acid supplementation on inflammatory cytokine levels in infants at high genetic risk for type 1 diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes. 2015;16:271–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bonifacio E, Ziegler AG, Klingensmith G, Schober E, Bingley PJ, Rottenkolber M, et al. Effects of high-dose oral insulin on immune responses in children at high risk for type 1 diabetes: the pre-POINT randomized clinical trial. Jama. 2015;313:1541–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gale EA, Bingley PJ, Emmett CL, Collier T. European nicotinamide diabetes intervention trial (ENDIT): a randomised controlled trial of intervention before the onset of type 1 diabetes. Lancet. 2004;363:925–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ryhanen SJ, Harkonen T, Siljander H, Nanto-Salonen K, Simell T, Hyoty H, et al. Impact of intranasal insulin on insulin antibody affinity and isotypes in young children with HLA-conferred susceptibility to type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:1383–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Näntö-Salonen K, Kupila A, Simell S, Siljander H, Salonsaari T, Hekkala A, et al. Nasal insulin to prevent type 1 diabetes in children with HLA genotypes and autoantibodies conferring increased risk of disease: a double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;372:1746–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Skyler JS, Krischer JP, Wolfsdorf J, Cowie C, Palmer JP, Greenbaum C, et al. Effects of oral insulin in relatives of patients with type 1 diabetes: the diabetes prevention trial–type 1. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:1068–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vehik K, Cuthbertson D, Ruhlig H, Schatz DA, Peakman M, Krischer JP. Long-term outcome of individuals treated with oral insulin: diabetes prevention trial-type 1 (DPT-1) oral insulin trial. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:1585–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hao W, Greenbaum CJ, Krischer JP, Cuthbertson D, Marks JB, Palmer JP. The effect of DPT-1 intravenous insulin infusion and daily subcutaneous insulin on endogenous insulin secretion and postprandial glucose tolerance. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:891–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krischer JP, Schatz DA, Bundy B, Skyler JS, Greenbaum CJ. Effect of oral insulin on prevention of diabetes in relatives of patients with type 1 diabetes: a randomized clinical trial. Jama. 2017;318:1891–902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elding Larsson H, Lundgren M, Jonsdottir B, Cuthbertson D, Krischer J, Group D-IS. Safety and efficacy of autoantigen-specific therapy with 2 doses of alum-formulated glutamate decarboxylase in children with multiple islet autoantibodies and risk for type 1 diabetes: a randomized clinical trial. Pediatr Diabetes. 2018;19:410–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Campbell-Thompson M Organ donor specimens: what can they tell us about type 1 diabetes? Pediatr Diabetes. 2015;16:320–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pugliese A, Vendrame F, Reijonen H, Atkinson MA, Campbell-Thompson M, Burke GW. New insight on human type 1 diabetes biology: nPOD and nPOD-transplantation. Curr Diab Rep. 2014;14:530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seay HR, Yusko E, Rothweiler SJ, et al. Tissue distribution and clonal diversity of the T and B cell repertoire in type 1 diabetes. JCI Insight. 2016;1:e88242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cerosaletti K, Barahmand-Pour-Whitman F, Yang J, et al. Single-cell RNA sequencing reveals expanded clones of islet antigen-reactive CD4+ T cells in peripheral blood of subjects with type 1 diabetes. J Immunol. 2017;199:323–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Campbell-Thompson M, Fu A, Kaddis JS, et al. Insulitis and beta-cell mass in the natural history of type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2016;65:719–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.••.Arif S, Leete P, Nguyen V, Marks K, Nor NM, Estorninho M, et al. Blood and islet phenotypes indicate immunological heterogeneity in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2014;63:3835–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This paper provides critical evidence of varied immunophenotypes at the time of diagnosis and earlier, specifically an INF-γ or IL-10-dominated response correlated with autoantibody presence or absence.

- 28.Campbell-Thompson ML, Atkinson MA, Butler AE, et al. Readdressing the 2013 consensus guidelines for the diagnosis of insulitis in human type 1 diabetes: is change necessary? Germany: Diabetologia; 2017. p. 753–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Campbell-Thompson ML, Atkinson MA, Butler AE, Chapman NM, Frisk G, Gianani R, et al. The diagnosis of insulitis in human type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2013;56:2541–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Redondo MJ, Steck AK, Pugliese A. Genetics of type 1 diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes. 2018;19:346–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pociot F, Lernmark Å. Genetic risk factors for type 1 diabetes. Lancet. 2016;387:2331–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Redondo MJ, Jeffrey J, Fain PR, Eisenbarth GS, Orban T. Concordance for islet autoimmunity among monozygotic twins. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2849–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Redondo MJ, Rewers M, Yu L, Garg S, Pilcher CC, Elliott RB, et al. Genetic determination of islet cell autoimmunity in monozygotic twin, dizygotic twin, and non-twin siblings of patients with type 1 diabetes: prospective twin study. BMJ. 1999;318:698–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barrett JC, Clayton DG, Concannon P, et al. Genome-wide association study and meta-analysis find that over 40 loci affect risk of type 1 diabetes. Nat Genet. 2009;41:703–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Onengut-Gumuscu S, Chen WM, Burren O, et al. Fine mapping of type 1 diabetes susceptibility loci and evidence for colocalization of causal variants with lymphoid gene enhancers. Nat Genet. 2015;47:381–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Noble JA, Valdes AM, Cook M, Klitz W, Thomson G, Erlich HA. The role of HLA class II genes in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus: molecular analysis of 180 Caucasian, multiplex families. Am J Hum Genet. 1996;59:1134–48. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Risch N Assessing the role of HLA-linked and unlinked determinants of disease. Am J Hum Genet. 1987;40:1–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lambert AP, Gillespie KM, Thomson G, Cordell HJ, Todd JA, Gale EAM, et al. Absolute risk of childhood-onset type 1 diabetes defined by human leukocyte antigen class II genotype: a population-based study in the United Kingdom. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:4037–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Noble JA. Immunogenetics of type 1 diabetes: a comprehensive review. J Autoimmun. 2015;64:101–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lötvall J, Akdis CA, Bacharier LB, Bjermer L, Casale TB, Custovic A, et al. Asthma endotypes: a new approach to classification of disease entities within the asthma syndrome. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:355–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Krischer JP, Lynch KF, Lernmark Å, Hagopian WA, Rewers MJ, She JX, et al. Genetic and environmental interactions modify the risk of diabetes-related autoimmunity by 6 years of age: the TEDDY study. Diabetes Care. 2017;40:1194–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bonifacio E Predicting type 1 diabetes using biomarkers. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:989–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Erlich H, Valdes AM, Noble J, Carlson JA, Varney M, Concannon P, et al. HLA DR-DQ haplotypes and genotypes and type 1 diabetes risk: analysis of the type 1 diabetes genetics consortium families. Diabetes. 2008;57:1084–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Klitz W, Maiers M, Spellman S, Baxter-Lowe LA, Schmeckpeper B, Williams TM, et al. New HLA haplotype frequency reference standards: high-resolution and large sample typing of HLA DR-DQ haplotypes in a sample of European Americans. Tissue Antigens. 2003;62:296–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Krischer JP, Liu X, Lernmark Å, Hagopian WA, Rewers MJ, She JX, et al. The influence of type 1 diabetes genetic susceptibility regions, age, sex, and family history on the progression from multiple autoantibodies to type 1 diabetes: a TEDDY study report. Diabetes. 2017;66:3122–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lempainen J, Hermann R, Veijola R, Simell O, Knip M, Ilonen J. Effect of the PTPN22 and INS risk genotypes on the progression to clinical type 1 diabetes after the initiation of β-cell autoimmunity. Diabetes. 2012;61:963–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bonifacio E, Krumsiek J, Winkler C, Theis FJ, Ziegler AG. A strategy to find gene combinations that identify children who progress rapidly to type 1 diabetes after islet autoantibody seroconversion. Acta Diabetol. 2014;51:403–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Inshaw JRJ, Walker NM, Wallace C, Bottolo L, Todd JA. The chromosome 6q22.33 region is associated with age at diagnosis of type 1 diabetes and disease risk in those diagnosed under 5 years of age. Diabetologia. 2018;61:147–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Winkler C, Krumsiek J, Buettner F, Angermüller C, Giannopoulou EZ, Theis FJ, et al. Feature ranking of type 1 diabetes susceptibility genes improves prediction of type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2014;57:2521–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Redondo MJ, Geyer S, Steck AK, Sharp S, Wentworth JM, Weedon MN, et al. A type 1 diabetes genetic risk score predicts progression of islet autoimmunity and development of type 1 diabetes in individuals at risk. Diabetes Care. 2018:dc180087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Oram RA, Patel K, Hill A, Shields B, McDonald TJ, Jones A, et al. A type 1 diabetes genetic risk score can aid discrimination between type 1 and type 2 diabetes in young adults. Diabetes Care. 2016;39:337–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Patel KA, Oram RA, Flanagan SE, et al. Type 1 diabetes genetic risk score: a novel tool to discriminate monogenic and type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2016;65:2094–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Thomas NJ, Jones SE, Weedon MN, Shields BM, Oram RA, Hattersley AT. Frequency and phenotype of type 1 diabetes in the first six decades of life: a cross-sectional, genetically stratified survival analysis from UK biobank. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018;6:122–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ziegler AG, Rewers M, Simell O, Simell T, Lempainen J, Steck A, et al. Seroconversion to multiple islet autoantibodies and risk of progression to diabetes in children. Jama. 2013;309:2473–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schlosser M, Mueller PW, Törn C, Bonifacio E, Bingley PJ, Laboratories P. Diabetes antibody standardization program: evaluation of assays for insulin autoantibodies. Diabetologia. 2010;53: 2611–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lampasona V, Schlosser M, Mueller PW, Williams AJK, Wenzlau JM, Hutton JC, et al. Diabetes antibody standardization program: first proficiency evaluation of assays for autoantibodies to zinc transporter 8. Clin Chem. 2011;57:1693–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schlosser M, Mueller PW, Achenbach P, Lampasona V, Bingley PJ, Laboratories P. Diabetes antibody standardization program: first evaluation of assays for autoantibodies to IA-2β. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:2410–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Törn C, Mueller PW, Schlosser M, Bonifacio E, Bingley PJ, Participating Laboratories. Diabetes antibody standardization program: evaluation of assays for autoantibodies to glutamic acid decarboxylase and islet antigen-2. Diabetologia. 2008;51:846–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wasserfall C, Montgomery E, Yu L, Michels A, Gianani R, Pugliese A, et al. Validation of a rapid type 1 diabetes autoantibody screening assay for community-based screening of organ donors to identify subjects at increased risk for the disease. Clin Exp Immunol. 2016;185:33–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Miao D, Steck AK, Zhang L, Guyer KM, Jiang L, Armstrong T, et al. Electrochemiluminescence assays for insulin and glutamic acid decarboxylase autoantibodies improve prediction of type 1 diabetes risk. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2015;17:119–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Steck AK, Fouts A, Miao D, Zhao Z, Dong F, Sosenko J, et al. ECL-IAA and ECL-GADA can identify high-risk single autoantibody-positive relatives in the TrialNet pathway to prevention study. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2016;18:410–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sosenko JM, Yu L, Skyler JS, Krischer JP, Gottlieb PA, Boulware D, et al. The use of Electrochemiluminescence assays to predict autoantibody and glycemic progression toward type 1 diabetes in individuals with single autoantibodies. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2017;19:183–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jacobsen LM, Posgai A, Seay HR, Haller MJ, Brusko TM. T cell receptor profiling in type 1 diabetes. Curr Diab Rep. 2017;17:118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kent SC, Mannering SI, Michels AW, Babon JAB. Deciphering the pathogenesis of human type 1 diabetes (T1D) by interrogating T cells from the “scene of the crime”. Curr Diab Rep. 2017;17:95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Smith MJ, Packard TA, O’Neill SK, et al. Loss of anergic B cells in prediabetic and new-onset type 1 diabetic patients. Diabetes. 2015;64:1703–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Smith MJ, Rihanek M, Wasserfall C, Mathews CE, Atkinson MA, Gottlieb PA, et al. Loss of B-cell Anergy in type 1 diabetes is associated with high-risk HLA and non-HLA disease susceptibility alleles. Diabetes. 2018;67:697–703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ludvigsson J, Heding L. Abnormal proinsulin/C-peptide ratio in juvenile diabetes. Acta Diabetol Lat. 1982;19:351–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Snorgaard O, Hartling SG, Binder C. Proinsulin and C-peptide at onset and during 12 months cyclosporin treatment of type 1 (insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia. 1990;33:36–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Watkins RA, Evans-Molina C, Terrell JK, et al. Proinsulin and heat shock protein 90 as biomarkers of beta-cell stress in the early period after onset of type 1 diabetes. Transl Res. 2016;168:96–106.e101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Schölin A, Nyström L, Arnqvist H, Bolinder J, Björk E, Berne C, et al. Proinsulin/C-peptide ratio, glucagon and remission in new-onset type 1 diabetes mellitus in young adults. Diabet Med. 2011;28:156–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Røder ME, Knip M, Hartling SG, Karjalainen J, Akerblom HK, Binder C. Disproportionately elevated proinsulin levels precede the onset of insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus in siblings with low first phase insulin responses. The Childhood Diabetes in Finland Study Group. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1994;79:1570–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Truyen I, De Pauw P, Jørgensen PN, et al. Proinsulin levels and the proinsulin:c-peptide ratio complement autoantibody measurement for predicting type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2005;48:2322–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sims EK, Chaudhry Z, Watkins R, Syed F, Blum J, Ouyang F, et al. Elevations in the fasting serum proinsulin-to-C-peptide ratio precede the onset of type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2016;39: 1519–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Van Dalem A, Demeester S, Balti EV, et al. Prediction of impending type 1 diabetes through automated dual-label measurement of proinsulin:C-peptide ratio. PLoS One. 2016;11: e0166702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Akirav EM, Lebastchi J, Galvan EM, Henegariu O, Akirav M, Ablamunits V, et al. Detection of β cell death in diabetes using differentially methylated circulating DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:19018–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lebastchi J, Deng S, Lebastchi AH, Beshar I, Gitelman S, Willi S, et al. Immune therapy and β-cell death in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2013;62:1676–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Usmani-Brown S, Lebastchi J, Steck AK, Beam C, Herold KC, Ledizet M. Analysis of β-cell death in type 1 diabetes by droplet digital PCR. Endocrinology. 2014;155:3694–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Husseiny MI, Kaye A, Zebadua E, Kandeel F, Ferreri K. Tissue-specific methylation of human insulin gene and PCR assay for monitoring beta cell death. PLoS One. 2014;9:e94591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Herold KC, Usmani-Brown S, Ghazi T, Lebastchi J, Beam CA, Bellin MD, et al. β Cell death and dysfunction during type 1 diabetes development in at-risk individuals. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:1163–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Fisher MM, Watkins RA, Blum J, et al. Elevations in circulating methylated and unmethylated preproinsulin DNA in new-onset type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2015;64:3867–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kuroda A, Rauch TA, Todorov I, Ku HT, al-Abdullah IH, Kandeel F, et al. Insulin gene expression is regulated by DNA methylation. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Usmani-Brown S, Lebastchi J, Steck AK, Beam C, Herold KC, Ledizet M Analysis of beta cell death in type 1 diabetes by droplet digital PCR. Endocrinology. 2014;en20141150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Akirav EM, Lebastchi J, Galvan EM, Henegariu O, Akirav M, Ablamunits V, et al. Detection of beta cell death in diabetes using differentially methylated circulating DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:19018–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Herold KC, Usmani-Brown S, Ghazi T, Lebastchi J, Beam CA, Bellin MD, et al. Beta cell death and dysfunction during type 1 diabetes development in at-risk individuals. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:1163–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lehmann-Werman R, Neiman D, Zemmour H, Moss J, Magenheim J, Vaknin-Dembinsky A, et al. Identification of tissue-specific cell death using methylation patterns of circulating DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:E1826–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Snowhite IV, Allende G, Sosenko J, Pastori RL, Messinger Cayetano S, Pugliese A. Association of serum microRNAs with islet autoimmunity, disease progression and metabolic impairment in relatives at risk of type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2017;60:1409–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Garcia-Contreras M, Shah SH, Tamayo A, Robbins PD, Golberg RB, Mendez AJ, et al. Plasma-derived exosome characterization reveals a distinct microRNA signature in long duration type 1 diabetes. Sci Rep. 2017;7:5998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lakhter AJ, Pratt RE, Moore RE, Doucette KK, Maier BF, DiMeglio L, et al. Beta cell extracellular vesicle miR-21–5p cargo is increased in response to inflammatory cytokines and serves as a biomarker of type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2018;61:1124–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Zhao Z, Miao D, Michels A, Steck A, Dong F, Rewers M, et al. A multiplex assay combining insulin, GAD, IA-2 and transglutaminase autoantibodies to facilitate screening for pre-type 1 diabetes and celiac disease. J Immunol Methods. 2016;430:28–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Eizirik DL, Miani M, Cardozo AK. Signalling danger: endoplasmic reticulum stress and the unfolded protein response in pancreatic islet inflammation. Diabetologia. 2013;56:234–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ovalle F, Grimes T, Xu G, Patel AJ, Grayson TB, Thielen LA, et al. Verapamil and beta cell function in adults with recent-onset type 1 diabetes. Nat Med. 2018;24:1108–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Quiskamp N, Bruin JE, Kieffer TJ. Differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells into beta-cells: potential and challenges. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;29:833–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Mastrandrea L, Yu J, Behrens T, Buchlis J, Albini C, Fourtner S, et al. Etanercept treatment in children with new-onset type 1 diabetes: pilot randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:1244–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Xia CQ, Zhang P, Li S, Yuan L, Xia T, Xie C, et al. C-Abl inhibitor imatinib enhances insulin production by β cells: c-Abl negatively regulates insulin production via interfering with the expression of NKx2.2 and GLUT-2. PLoS One. 2014;9:e97694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Griffin KJ, Thompson PA, Gottschalk M, Kyllo JH, Rabinovitch A. Combination therapy with sitagliptin and lansoprazole in patients with recent-onset type 1 diabetes (REPAIR-T1D): 12-month results of a multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014;2:710–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Olsen JA, Kenna LA, Spelios MG, Hessner MJ, Akirav EM. Circulating differentially methylated amylin DNA as a biomarker of β-cell loss in type 1 diabetes. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0152662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Sklenarova J, Petruzelkova L, Kolouskova S, Lebl J, Sumnik Z, Cinek O. Glucokinase gene may be a more suitable target than the insulin gene for detection of β cell death. Endocrinology. 2017;158:2058–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]