Abstract

Background:

Rituximab has increasingly been used for the treatment of hematological malignancies and autoimmune diseases, and its efficacy and safety are well established. Although clinical trials have shown conflicting results regarding the association of rituximab with infections, an increased incidence of infections has recently been reported in patients with lymphomas being treated with rituximab. However, clinical experience regarding the association of rituximab with different types of infection is lacking and this association has not been established in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

Methods:

All previous studies included in our literature review were found using a PubMed, EMBASE, and Cochrane database search of the English-language medical literature applying the terms ‘rituximab’, ‘monoclonal antibodies’, ‘infections’, ‘infectious complications’, and combinations of these terms. In addition, the references cited in these articles were examined to identify additional reports.

Results:

We performed separate analyses of data regarding the association of rituximab with infection in (1) patients with hematological malignancies, (2) patients with autoimmune disorders, and (3) transplant patients. Recent data show that rituximab maintenance therapy significantly increases the risk of both infection and neutropenia in patients with lymphoma or other hematological malignancies. On the other hand, data available to date do not indicate an increased risk of infections when using rituximab compared with concurrent control treatments in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. However, there is a lack of sufficient long-term data to allow such a statement to be definitively made, and caution regarding infections should continue to be exercised, especially in patients who have received repeated courses of rituximab, are receiving other immunosuppressants concurrently, and in those whose immunoglobulin levels have fallen below the normal range. Few data are available concerning the risk of organ transplant recipients developing infections following rituximab therapy. Data from case reports, case series, and retrospective studies correlate rituximab use with the development of a variety of infections in transplant patients.

Conclusions:

Further studies are needed to clarify the association of rituximab with infection. Physicians and patients should be educated about the association of rituximab with infectious complications. Monitoring of absolute neutrophil count and immunoglobulin levels and the identification of high-risk groups for the development of infectious complications, with timely vaccination of these groups, are clearly needed.

Keywords: Rituximab, Infection, Immunocompromised

1. Introduction

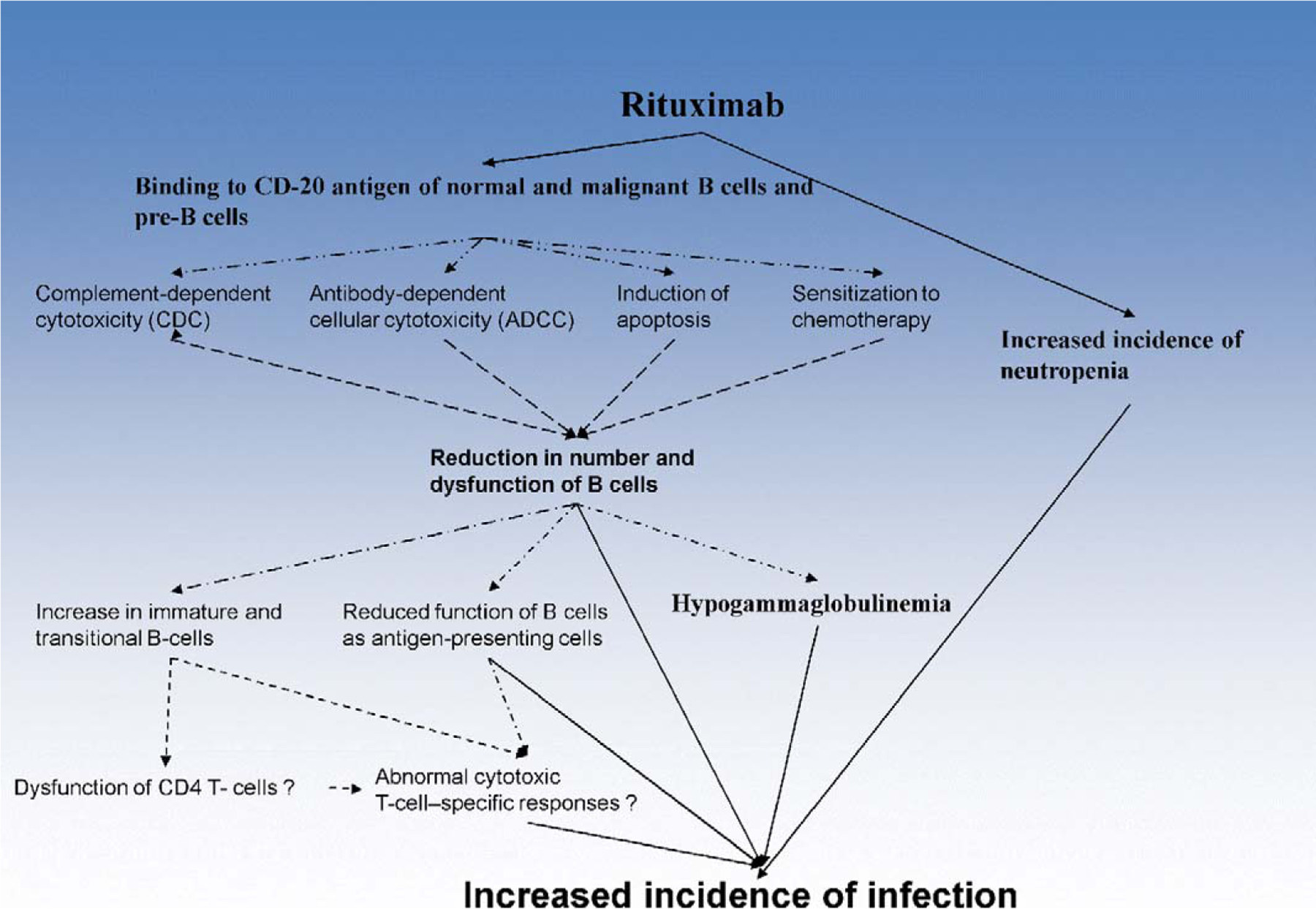

Rituximab (Rituxan®) is a chimeric human–mouse monoclonal antibody that has been used extensively in the treatment of hematological malignancies and autoimmune diseases and is US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved for CD20-positive B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) and for moderate-to-severe rheumatoid arthritis (RA) not responding to other treatments.1–3 More specifically, rituximab is a human–mouse chimeric monoclonal antibody (IgG1) that reacts specifically with the CD20 antigen expressed on more than 95% of normal and malignant B-cells, inducing complement-mediated and antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (Fig. 1).4

Fig. 1.

Mechanism of action of rituximab. Rituximab reacts specifically with the CD20 antigen expressed on more than 95% of normal and malignant B-cells, inducing complement-mediated and antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity. There is growing evidence supporting the notion that rituximab, in addition to its effect on B cells, also influences T-cell immunity and this may predispose to opportunistic infections. Rituximab may in addition cause immunosuppression through several other mechanisms such as delayed-onset cytopenia, particularly neutropenia and hypogammaglobulinemia.

Treatment with rituximab causes a rapid depletion of pre-B- and mature B-cells, which remain at low or undetectable levels for 2–6 months before returning to pretreatment levels, generally within 12 months. There is growing evidence, including an increased incidence of certain viral infections with the use of rituximab,5 supporting the notion that rituximab, in addition to its effect on B cells, also influences T-cell immunity and predisposes to opportunistic infections.6–9 Rituximab may cause immunosuppression through several other mechanisms such as delayed-onset cytopenia, particularly neutropenia10 and hypogammaglobulinemia, especially when administered for long periods, e.g., in maintenance therapy.11–13

Clinical trials have shown conflicting results regarding the association of rituximab with infections.5,14–22 An increased incidence of infections in patients with lymphomas and RA being treated with rituximab has recently been reported.23–26 Pooled data from 356 patients who received rituximab monotherapy showed that the incidence rate of infectious events was 30%; 19% of patients had bacterial infections, 10% viral infections, 1% fungal infections, and 6% infections of unknown etiology. Severe infections, including sepsis, occurred in only 1% of patients during the treatment period, and in 2% during the follow-up period.15 In a recent review27 involving 389 patients from 25 studies, the incidence of serious infections varied from 2.8% to 45% (mean 12.5%).

Infection in patients treated with rituximab is a multifactorial process and its incidence becomes difficult to analyze. The age of the patient, the presence of other medical problems, and concomitant drug therapies can influence susceptibility to infection. Thus, and for purposes of clarity, in this report we present separate data regarding the association of rituximab with infection in (1) patients with hematological malignancies, (2) patients with autoimmune disorders, and (3) transplant patients.

2. Methods

All previous studies included in our literature review were found using a search of PubMed, EMBASE, and the Cochrane database (through August 2009) of the English-language medical literature applying the terms ‘rituximab’, ‘monoclonal antibodies’, ‘infections’, ‘infectious complications’, and combinations of these terms. In addition, the references cited in these articles were examined to identify additional reports. Regarding the association of rituximab with infection, we reviewed evidence from meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, and retrospective studies. We performed separate analyses of the data regarding the association of rituximab with infection in (1) patients with hematological malignancies, (2) patients with autoimmune disorders, and (3) transplant patients. However, due to the paucity of data regarding the different types of infections associated with the use of rituximab (bacterial, viral, fungal, parasitic), we also reviewed the evidence from case–control studies, case series, and case reports.

3. Rituximab and infection in hematological malignancies

Table 1 outlines the most important studies evaluating infection in rituximab-treated patients with hematological malignancies.19,23,28–45

Table 1.

Studies regarding infectious complications in patients with lymphoma treated with rituximab

| Type of study | Author, year [Ref.] | Patient characteristics | Chemotherapy | Comments | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meta-analysis | Aksoy, 2009 [23] | Lymphoma | Rituximab maintenance therapy | Significantly increased rates of infections and neutropenia. Infection rates were 8.1% in patients who had received rituximab maintenance therapy vs. 3.9% in those who had not. Neutropenia rates were 13.4% vs. 6.3%, respectively (p<0.001) | Meta-analysis of the RCTs demonstrated that rituximab maintenance therapy significantly increased the RR of both infection and neutropenia in patients with lymphoma |

| Meta-analysis of RCTs | Vidal, 2009 [28] | Follicular lymphoma | Rituximab | Patients undergoing rituximab maintenance therapy had more infection-related adverse events than patients in the observation arm (RR 1.99, 95% CI 1.21–3.27). When only grade 3 or 4 infection-related adverse events were included in the analysis, this effect was even more pronounced (RR 2.90, 95% CI 1.24–6.76) | |

| RCT phase II | Eve, 2009 [29] | Previously untreated mantle cell lymphoma | Fludarabine and cyclophosphamide with or without rituximab | Non-hematological toxicity was similar between the two treatment arms | |

| RCT | Kaplan, 2005 [30] | NHL (HIV patients) | R-CHOP vs. CHOP | 99 patients treated with R-CHOP vs. 51 patients treated with CHOP (infection rate NR). Presence of opportunistic infections in the R-CHOP group and absence of these infections in the CHOP group | Infection-related death was 14% with R-CHOP vs. 2% with CHOP (p = 0.035) |

| RCT | Lenz, 2005 [31] | NHL Mantle cell | R-CHOP vs. CHOP | 33% (grade I–II) and 5% (grade III/IV) of 62 patients treated with R-CHOP developed infections vs. 29% (grade I–II) and 6% (grade III/IV) of 60 patients treated with CHOP | NR |

| RCT | Hiddemann, 2005 [32] | NHL follicular | R-CHOP vs. CHOP | 5% of 223 patients treated with R-CHOP developed infections vs. 7% of 205 patients treated with CHOP | Infection-related death 1.9% with R-CHOP vs. 0.5% with CHOP |

| RCT | Feugier, 2005 [33], Coiffier, 2002 [34] | DLBCL | R-CHOP vs. CHOP | 65% (any grade) and 12% (grade III/IV) of 202 patients treated with R-CHOP developed infections vs. 65% (any grade) and 20% (grade III/IV) of 197 patients treated with CHOP | Infection-related death 1.7% with R-CHOP vs. 1.9% with CHOP |

| RCT | Habermann, 2006 [35] | DLBCL | R-CHOP vs. CHOP | 17% of 318 patients treated with R-CHOP developed infections vs. 16% of 314 patients treated with CHOP | |

| RCT | Pfreundschuh, 2006 [36] | NHL B-cell | R-CHOP vs. CHOP | 7% of 411 patients treated with R-CHOP developed infections vs. 8% of 413 patients treated with CHOP | |

| RCT | Forstpointner, 2004 [37] | NHL follicular and mantle cell | Rituximab + FCM vs. FCM | 1.5% (grade III/IV) of 62 patients treated with R-FCM developed infections vs. 1.5% (grade III/IV) of 66 patients treated with FCM | |

| RCT | Marcus, 2005 [38] | NHL follicular | Rituximab + CVP vs. CVP | No difference between the two groups (162 patients in R-CVP vs. 159 in CVP) | |

| RCT | Herold, 2003 [39] | Indolent NHL | Rituximab + MCP vs. MCP | No difference in infection rates between the two groups (55 patients in R-MCP vs. 51 in MCP) | |

| Controlled clinical trial | Dungarwalla, 2008 [40] | 14 heavily pre-treated CLL patients | HDMP ± rituximab | 2 cases of systemic candidiasis, 2 cases of aspergillosis, 1 case of VZV, 1 case of adenovirus, bacteremia. Although HDMP-R causes little or no myelosuppression, the addition of rituximab might have predisposed to opportunistic infections. However, heavily pre-treated CLL patients have an increased susceptibility to infection intrinsic to the disease. Small series of patients/caution about conclusions | All patients died (except for the case with VZV) |

| RCT phase II | Del Poeta, 2008 [41] | B-CLL | Fludarabine and rituximab | 3 dermatomal herpes zoster infections and 4 localized herpes simplex infections | |

| Retrospective study | Ennishi, 2008 [42] | 64 yo M with follicular lymphoma stage IVa (partial response to treatment); 61 yo M with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma stage 1a (complete response to treatment) | R-CHOP | 13 of 90 (14%) patients developed interstitial pneumonitis during R-CHOP therapy, compared with none of 105 patients treated with CHOP alone; 2 of these cases were PCP | All patients responded well to treatment, and recovered within 2–3 weeks |

| Retrospective study | Lee, 2008 [19] | 46 patients with relapsed indolent or high-risk aggressive B cell NHL who received rituximab (17 patients) or not (29 patients) before autologous HSCT | Rituximab | Post-transplant infectious complications up to 6 months after transplantation. Seventeen of 46 patients received rituximab before HSCT. Three of them suffered from CMV infection and two of them developed CMV disease. All of the patients with CMV disease recovered after ganciclovir and CMV-specific immunoglobulin therapy. Twenty-nine of 46 patients without rituximab treatment before HSCT did not develop CMV after HSCT. Risk of CMV infection after autologous HSCT higher in rituximab-treated patients (17.6% vs. 0%, p = 0.045). Risk of CMV disease had higher trend with rituximab therapy than without rituximab therapy (11.7% vs. 0%, p = 0.131) | All 3 cases responded to ganciclovir combined with CMV-specific immunoglobulin |

| RCT phase III | Van Oers, 2006 [43] | Relapsed/resistant follicular lymphoma | R-CHOP | Upper respiratory tract infections mostly | |

| RCT phase III | Ghielmini, 2005 [44] | Mantle cell lymphoma | R-CHOP | One patient experienced three episodes of pneumonia, 1 case of hepatitis, 1 case of septic shock | |

| RCT phase II | Hainsworth, 2003 [45] | CLL/SL | Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia, 1 patient; localized herpes zoster, 1 patient; and gastroenteritis, probably viral, 1 patient |

CHOP, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; CVP, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone; CMV, cytomegalovirus; DLBCL, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; FCM, fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and mitoxantrone; HDMP, high-dose methylprednisolone; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; HSCT, hematological stem cell transplantation; M, male; MCP, mitoxantrone, chlorambucil, and prednisolone; NHL, non-Hodgkin lymphoma; NR, not reported; PCP, Pneumocystis jiroveci (carinii) pneumonia; R, rituximab; RCT, randomized controlled trial; RR, relative risk; SL, small lymphocytic lymphoma; VZV, varicella zoster virus; yo, year-old.

In a recent systematic review in patients with lymphoma, Aksoy et al. found significantly increased rates of infections and neutropenia in patients who had received rituximab maintenance therapy compared with those who had not (8.1% vs. 3.9% and 13.4% vs. 6.3%, respectively).23 In a similar meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCT), patients with follicular lymphoma who underwent rituximab maintenance therapy had more infection-related adverse events than patients in the observation arm (relative risk (RR) 1.99, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.21–3.27).28 This effect was more pronounced when only grade 3 or 4 infection-related adverse events were included in the analysis (RR 2.90, 95% CI 1.24–6.76).28

Regarding other hematological neoplasias, seven clinical trials tested rituximab added to the combination of cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (CHOP) versus CHOP chemotherapy alone.26 In six studies comparing rituximab with CHOP (R-CHOP) versus CHOP alone (excluding HIV-1-positive patients), the rate of infection was higher in one study,35 comparable in three studies,31,32,36 and smaller in one study;34 a 1% increase in infection-associated mortality was found in one study.33

In HIV patients with lymphoma treated with R-CHOP versus CHOP, a significant 12% increase in the occurrence of opportunistic infections and infection-related deaths was observed.30 Therefore, it appears that HIV seropositivity influences the incidence of infectious complications in such patients.

Concerning the combination of rituximab with non-CHOP-containing regimens, no significant difference in infection rates compared to the standard regimen was found in three RCTs.37–39 Nevertheless, such effects depend on the co-administered agent. For example a combined regimen with fludarabine (associated with profound T-cell depletion) may substantially increase the risk of opportunistic infections both in the induction and the maintenance phase.37,41,46,47

The duration of rituximab therapy may also be important. In one retrospective study of hematology patients receiving rituximab, duration of rituximab therapy, reduction in IgM after administration of rituximab, and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) administration were risk factors associated with infection.48

Thus, rituximab significantly increases the risk of both infection and neutropenia in patients with lymphoma or other hematological malignancies, and this risk appears also to depend on the co-administered agent.

4. Rituximab and infection in autoimmune disorders

Table 2 outlines the most important studies evaluating infection in rituximab-treated patients with autoimmune disorders.24,25,49–55

Table 2.

Clinical trials and open label studies that report incidence of infections with use of rituximab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis

| Type of study | Author, year [Ref.] | Patient characteristics | Immunosuppression | F/u of study duration | Comments | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical trial | Lafyatis, 2009 [49] | Diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis | Rituximab | 6 months | No significant infections were noted in this pilot study | Treatment with rituximab appeared to be safe and well tolerated among patients with dcSSc |

| Clinical trial | Genovese, 2009 [50] | Patients with advanced RA many of whom had previously been treated with multiple RA therapies, including biologicals prior to receiving rituximab, and then withdrew from clinical trials and subsequently received further biological therapy | Biological DMARD after rituximab treatment | In 185 patients who received rituximab plus another biological DMARD 13 SIEs (6.99 events/100 patient-years) occurred following rituximab, but prior to another biological DMARD. 10 SIEs (5.49 events/100 patient-years) occurred following another biological DMARD. SIEs were of typical type and severity for RA patients. No fatal or opportunistic infections | The size of the sample and limited follow-up restricts definitive conclusions about safety in B-cell depleted patients receiving additional biological DMARDs | |

| DANCER RCT (phase IIB) | Emery, 2006 [51] | Patients with RA | MTX +/− rituximab | 24 weeks | 42/149 (28%) of patients who were treated with MTX developed infections and 2/149 (1%) developed serious infections. 50/142 (35%) of patients who were treated with MTX + rituximab (500 mg) developed infections and 0/142 (0%) developed serious infections. 67/192 (35%) of patients who were treated with MTX + rituximab (1000 mg) developed infections and 4/192 (2%) developed serious infections. Type and severity of infections were similar across all three treatment arms. The most common infections were respiratory tract infections, urinary tract infections, and nasopharyngitis. The overall rate of serious infections (events/100 patient-years) was 3.19 for MTX alone and 4.74 for rituximab 1000 mg | Of the 6 serious infections, 2 occurred in the MTX monotherapy group (1 each of pneumonia and respiratory tract infection) and 4 occurred in the rituximab 1000 mg group (2 cases of pyelonephritis and 1 case each of bronchitis and epiglottitis); all serious infections were reported to have resolved without sequelae |

| Phase IIA | Edwards, 2004 [52] | Patients with RA | MTX +/− rituximab, cyclophosphamide + rituximab | 24 weeks | 1/40 (3%) of patients who were treated with MTX developed serious infections. 2/40 (5%) of patients who were treated with rituximab (1000 mg) developed serious infections. 2/41 (5%) of patients who were treated with cyclophosphamide + rituximab (1000 mg) developed serious infections. 0/40 (0%) of patients who were treated with MTX + rituximab (1000 mg) developed serious infections. In total 4 patients who had received rituximab developed serious infections (2 had septic arthritis, 1 of whom also had Staphylococcus aureus-related septicemia; 1 had 2 episodes of Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia; and 1 had bronchopneumonia) | One patient in the rituximab group with serious infection (bronchopneumonia) subsequently died, although death may have been related to concomitant ischemic/vascular heart disease |

| Phase IIA extension | Edwards, 2004 [52] | Patients with RA | MTX +/− rituximab, cyclophosphamide + rituximab | 24 weeks | 0/37 (0%) of patients who were treated with MTX developed serious infections. 1/38 (3%) of patients who were treated with rituximab (1000 mg) developed serious infections (1 case of gastroenteritis). 0/37 (0%) of patients who were treated with cyclophosphamide + rituximab (1000 mg) developed serious infections. 1/39 (3%) of patients who were treated with MTX + rituximab (1000 mg) developed serious infections (1 case of pyelonephritis) | NR |

| REFLEX RCT (phase III) | Cohen, 2006 [53] | Patients with RA | MTX +/− rituximab | 24 weeks | 79/209 (38%) of patients who were treated with MTX developed infections and 1/209 (3%) developed serious infections. 126/308 (41%) of patients who were treated with MTX + rituximab (1000mg) developed infections and 7/308 (2%) developed serious infections. The overall infection rate (events/100 patient-years) was slightly higher in placebo-treated patients (154.6) than in rituximab-treated patients (138.2). The most common infections observed in both groups were upper respiratory tract infections, nasopharyngitis, urinary tract infections, bronchitis, and sinusitis. Rates of serious infections were 3.7/100 patient-years for placebo and 5.2/100 patient-years for rituximab; no statistical comparison of this difference was reported | Of 7 serious infections that occurred in the rituximab-treated patients, 6 (1 case each of gastroenteritis, pyelonephritis, cat-bite infection, influenza, fever of unknown etiology, and de novo hepatitis B (HBV)) resolved without sequelae, while the other infection (gangrenous cellulitis) resulted in amputation of a toe |

| Open label trial | Keystone, 2007 [54] | Ongoing follow-up study of all patients enrolled in the three original clinical trials (2 phase II and 1 phase III) who had an incomplete response to or were intolerant of TNF inhibitors | Rituximab vs. control group | No evidence to date for any increase in the incidence of infections and serious infections, with all patients having received at least 2 courses of rituximab.25 Rates of infection (events/100 patient-years)were 83, 83, 80, and 88 for patients who had received 1, 2, 3, or 4 courses of rituximab, respectively; the corresponding rates for serious infections were 4.1, 4.6, 5.6, and 8.0 events/100 patient-years. Rates of infections and serious infections appear relatively stable with increasing courses of rituximab, however the extent of observation for patients receiving multiple courses of treatment is inevitably less than that for single-course treatment. Longer follow-up data is necessary. Irrespective of the number of courses of rituximab, serious infections occurred most often during the first 3months after administration and declined thereafter. Overall, 68 of 1039 patients (7%) in the all-exposure population experienced a total of 78 serious infections following treatment with rituximab. The most common infections reported were upper respiratory tract infection, nasopharyngitis, urinary tract infection, bronchitis, and sinusitis. No incidences of opportunistic infections or tuberculosis were observed. The serious infection rate after course 1 (5.1 per 100 patient-years) remained stable through additional courses. The proportion of patients with circulating IgM and IgG levels below the LLN increased with subsequent courses; however, serious infection rates in these patients (5.6 per 100 patient-years in patients with low IgM levels and 4.8 per 100 patient-years in patients with low IgG levels)were comparable with those in patients with immunoglobulin levels above the LLN (4.7 per 100 patient-years) | Three serious infections were fatal. Two occurred between course 1 and course 2; 1 patient had bronchopneumonia and a second patient had neutropenic sepsis following concomitant treatment with trimethoprim. The third infection-related fatality occurred after course 2, from septic shock in a 54-year-old female diabetic patient with a history of sepsis and recurrent urinary tract infections | |

| Open label trial | Furst, 2007 [24] | Follow-up open label study on patients with RA | Rituximab vs. control group | From a total of 1053 patients who had been exposed to at least 1 course of rituximab (total drug exposure of 2438 patient-years), 702 patients reported at least 1 infection, the most common being upper respiratory infections (32%) and urinary tract infections (11%). Rates of serious infections for patients who had received 1, 2, 3, or 4 courses of rituximab were 5.4, 4.6, 6.3, and 5.4 events/100 patient-years, respectively | ||

| Open label trial | Furst, 2008 [25] | A 2-year follow-up of patients who participated in the phase IIA trial | Rituximab, MTX, MTX + rituximab, cyclophosphamide + rituximab | 2 year follow-up | No significant differences in the rate of infections between the 4 treatment arms (MTX, rituximab, rituximab + cyclophosphamide, and rituximab + MTX) | |

| Open label trial | Furst, 2010 [55] | Patients from both phase II studies | Rituximab vs. control group | Based on a total of 1669 patient-years of follow-up (145 patients had received at least 2 courses of rituximab), there was no evidence of an increase in the rate of infections compared with the data from the original phase II trials |

DANCER, Dose-ranging Assessment International Clinical Evaluation of Rituximab in RA trial; dcSSc; diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis; DMARD, disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; F/u, follow-up; HBV, hepatitis B virus; LLN, lower limit of normal; MTX, methotrexate; NR, not reported; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; RCT, randomized controlled trial; REFLEX, Randomized Evaluation of Long-Term Efficacy of Rituximab trial; SIE, serious infection event; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

Rituximab is effective in patients with RA with an inadequate response to methotrexate, for whom conventional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDS) have failed or who have received one or more tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors.

The three pre-approval phase II and phase III RCTs conducted with rituximab in patients with RA reported low rates of infection, serious or not.53 The rate of infection was higher with rituximab use in one RCT,52 and slightly higher in placebo-treated patients in another study.50 The incidence of serious infections was reported in one phase IIA RCT only: during a 48-week follow-up, six serious infections were reported in patients treated with rituximab regimens versus only one serious infection in a patient being treated with methotrexate alone; this difference was not statistically significant.56

Further information on the risk of infections associated with rituximab therapy has emerged from open-label extensions to the RCTs. No significant difference in the rates of infection with the use of rituximab and no cases of tuberculosis (TB), opportunistic infections, or viral reactivations have been reported in the open-label RA extension studies to date (Table 2).

A recent study suggested that there were no fatal or opportunistic infections prior to or after another biological DMARD (in patients with RA refractory to treatment) following rituximab treatment.50 In a separate meta-analysis of the three rituximab clinical trials, the pooled odds ratios (OR) for serious infections at all doses of rituximab versus placebo did not reveal any statistically significant increased risk (OR 1.45, 95% CI 0.56–3.73).54

Based on the results presented, treatment with rituximab for up to 3 years appears to be associated with a numerically increased incidence of infections (including serious infections). However no statistical difference regarding an increased risk for infection is evident and the risk appears lower than that associated with the TNF inhibitors. Long-term controlled data are necessary to allow a more precise definition of this risk. Thus, further studies are needed to elucidate the association of rituximab with infection in patients with RA, since current data do not indicate an increased risk of infections when using rituximab compared with concurrent control treatments.

5. Rituximab and infection in transplant patients

Rituximab off-label use includes organ transplantation. The use or rituximab has been increasing in the transplant population and an increasing number of infections have been reported. Few data are available concerning the risk of organ transplant recipients developing infections following rituximab therapy. Scemla et al. reported bacterial, viral, and fungal infection rates at 55.3%, 47.4%, and 13.2%, respectively, in kidney transplant patients who received rituximab therapy.57 In kidney transplant patients who received rituximab therapy at two different doses (375 mg/m2/week four times or 1000 mg/m2/week two times), Tsapepas et al. reported a bacterial infection rate at 48% and 61.1%, respectively, a viral infection rate at 8.2% and 25.3%, respectively, and a fungal infection rate at 20% and 8.2%, respectively.58 A recent retrospective study by Grim et al. observed no increased risk of infectious complications following rituximab therapy in renal transplant recipients.59

Low-dose rituximab induction therapy in renal transplant recipients appears to have no influence on the incidence of cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection and CMV seroconversion.60 However, because of the high incidence of CMV infection, especially for CMV-seronegative recipients who received rituximab, anti-CMV prophylaxis therapy needs to be considered.60

In one study of 77 kidney transplant patients who received rituximab therapy, the incidence of bacterial infection was similar between these patients and another kidney transplant control group who did not receive rituximab, whereas the viral infection rate was significantly lower, and the rate of fungal infection was significantly higher in the rituximab group.61 Nine out of 77 patients (11.68%) died after rituximab therapy, of which seven deaths (9.09%) were related to an infectious disease, compared to 1.55% in the controls (p = 0.0007).61

An increased incidence of JC infection has also been described in transplant patients who receive rituximab.61 Thus, after kidney transplantation, the use of rituximab is associated with a high risk of infectious disease and death related to infectious disease, and the independent predictive factors for infection-induced death were recipient age, bacterial and fungal infections, the combined use of rituximab, and anti-thymocyte globulin given for induction or anti-rejection therapy.61

In conclusion, although few data are available regarding the association of rituximab with infection in organ transplant recipients, data from renal transplant patients suggest an increased risk of infection with the use of rituximab in this population.

6. Types of infection

Table 3 outlines the most important types of infection associated with rituximab use.5,16,19,21,30,36,41,42,44,45,49,50,53,54,59, 62–122

Table 3.

Cases in which addition of rituximab was likely associated with the development of infection

| Infection | No. of patients | Pathogens (n) | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterial infections | |||

| Sinopulmonary infection | ND | Pneumonia (7), Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia (1), Streptococcus pneumoniae pneumonia (1), bronchitis (1), upper respiratory tract infections, nasopharyngitis, bronchitis, and sinusitis | 30, 36, 50, 53, 54, 59, 62–64 |

| Bacteremia | ND | Septic shock (3), bacteremia (5) | 30, 36, 44, 54, 59, 64 |

| Bacterial diarrhea | ND | Shigella (1) | 50 |

| Urinary tract infections | ND | No pathogens reported, pyelonephritis | 53, 54, 59 |

| Skin infections | ND | Erysipelas, gangrenous cellulitis | 50, 53, 59 |

| Bone and joint infections | 2 | Infection of right hip (1), septic polyarthritis with Ureaplasma urealyticum (1) | 50, 65 |

| Dental abscess | 1 | 49 | |

| Listeriosis | 1 | 81 | |

| Cat scratch disease | 1 | 53 | |

| Mycobacterial infections | |||

| Other non-tuberculous mycobacteria | 4 | Bacteremia caused by Mycobacterium wolinskyi (1), M. avium pleuritis (1), M. avium bacteremia (1), disseminated M. kansasii infection (1) | 66, 67 |

| Viral infections | |||

| CMV disease | 26 | CMV esophagitis (1), pneumonia (6), and enterocolitis (4), disseminated CMV infection (1) | 5, 19, 21, 59, 63, 68–71, 101 |

| VZV | 13 | 5, 41, 44, 45, 72–74, 101, 112 | |

| HSV | 6 | Disseminated HSV2 (1) | 41, 63, 75 |

| Hepatitis | ND | Not specified (3), de novo hepatitis B (2), HBV reactivation (21 cases in HBsAg-neg patients), HCV (2), HEV infection (1) | 5, 44, 45, 53, 76–94, 107, 119, 120, 122 |

| Gastroenteritis | 4 | 50, 53, 95 | |

| Parvovirus | 2 | 96, 97 | |

| Enterovirus | 3 | Enteroviral meningoencephalitis | 98–100 |

| Echovirus | 1 | 112 | |

| JC virus | 76 | 52 patients had lymphoproliferative disorders, two had SLE, one had rheumatoid arthritis (and oropharyngeal cancer that had been treated previously with chemotherapy and radiotherapy), one had idiopathic autoimmune pancytopenia, and one patient with NHL had a concomitant autoimmune hemolytic anemia | 101–104 |

| BK virus | 1 | BK virus CNS infection | 105, 106 |

| RSV | 2 | 107, 108 | |

| West Nile virus | 3 | 109–111 | |

| Influenza A virus | 2 | 53, 112 | |

| Fungal infections | |||

| Fungal infections (not specified) | Fungal pneumonia | 30 | |

| Candida infections | 4 | esophagitis (1), candidemia (3) | 30 |

| Pneumocystis jiroveci (carinii) | 13 | Pneumonia | 30, 42, 63, 113–116 |

| Aspergillus spp | 4 | Aspergillosis | 16, 117–119 |

| arasitic infections | |||

| Babesia microti | 8 | Babesiosis | 121 |

CMV, cytomegalovirus; CNS, central nervous system; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HEV, hepatitis E virus; HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen; HSV, herpes simplex virus; ND, not determined; NHL, non-Hodgkin lymphoma; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus; SLE, systematic lupus erythematosus; VZV, varicella zoster virus.

In a systematic review of the literature, Cornely et al.123 analyzed 992 patients treated with either alemtuzumab, rituximab, or both; 409 patients (41.2%) were treated with alemtuzumab, 535 (53.9%) with rituximab, and 48 (4.9%) with both. The overall number of opportunistic infections (OI) diagnosed was 299 (30.1%). Etiologies were distributed as follows: 109 (36.5%) infections of unknown or unspecified origin, 100 (33.4%) viral reactivations, 44 (14.7%) bacterial infections, 26 (8.7%) fungal infections, 11 (3.7%) protozoal infections, and nine (3.0%) viral infections. Viral reactivations were most frequently due to CMV (n = 58, 19.4%), herpes simplex virus (HSV; n = 30, 10.0%), varicella zoster virus (VZV; n = 11, 3.7%), and Epstein–Barr virus (EBV; n = 1, 0.3%). Pneumonias accounted for 15.1% (n = 45) of observed bacterial infections, and included 11 Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia (PCP) cases (3.7%) and 37 (12.4%) blood stream infection cases. Death attributable to OI occurred in 20 patients (2%). Optional prophylaxis of viral infections was reported in eight articles (n = 404, 40.7%), and optional prophylaxis for PCP in nine articles (n = 435, 43.9%).123

From our review of the literature a broad spectrum of infections has been associated with rituximab use in clinical trials, including respiratory tract infections (e.g., bronchopneumonia, nasopharyngitis, bronchitis, and sinusitis),53 bacteremia,53 sepsis,52,53 urinary tract infections (including pyelonephritis),52,53 gastroenteritis,52 cellulitis,53 septic arthritis,53 cat-bite infection,53 influenza,40,41 de novo hepatitis B (hepatitis B virus (HBV)),41 herpes zoster,40 HSV infection,40 adenovirus infection,40 systemic candidiasis,56 and aspergillosis.25 At the time of writing, we could find no published reports of TB in rituximab-treated patients in clinical trials.

Data from case reports, case series, and retrospective studies also correlate rituximab use with the development of a variety of bacterial, viral, fungal, and parasitic infections (Table 3).

7. Bacterial infections

Representative bacterial infections attributed to rituximab use are shown in Table 3. A small increase in serious bacterial infections in RA patients receiving rituximab l000 mg has been reported.24 In addition, an increase in the rate of serious infections was seen in a cohort of 78 patients with RA who received a TNF-α blocking agent after rituximab treatment.50 Thus, sinopulmonary infections are the most common bacterial infections that have been described in association with the use of rituximab, but further data from randomized controlled studies are needed to establish this association.

8. Mycobacterial infections

Several recent studies suggest that peripheral B cells are important in the host defense against mycobacteria.30,66,67 Past history suggestive of TB was an exclusion criterion in the clinical trials of rituximab in RA, and in the vast majority of cases, study patients had previously received TNF inhibitors; nevertheless no reactivation of TB occurred. In NHL clinical trials where history of TB was not an exclusion criterion, no evidence of an increased incidence of TB was noted.5 Infection with other mycobacteria has rarely been associated with rituximab. More specifically, bacteremia caused by Mycobacterium wolinskyi or Mycobacterium avium, M. avium pleuritis, and disseminated Mycobacterium kansasii infections have all been described.66,67 Since it is not clear whether rituximab or other immunosuppressants that were simultaneously administered promoted disease progression or caused mycobacterial disease, clinicians should remain vigilant for mycobacterial infections in patients selected for these therapies. Thus, there is an open issue regarding TB screening prior to rituximab initiation. The authors believe that such screening should be performed.

9. Viral infections

Data on the true incidence of viral infections after rituximab therapy are poor. Co-administration with other cytotoxic chemotherapeutic agents and the intensity and duration of T-cell-mediated immune suppression are significant cofactors increasing the infectious risk.41 Humoral dysfunction related to rituximab therapy may cause loss of neutralization of free viral particles by specific antibodies and an increase in serious viral infections; this hypothesis needs further investigation.

Reactivation of chronic HBV infection is one of the most frequently reported serious viral infections.80,82,85–89,107,120 In one RCT, opportunistic viral infections reported included three dermatomal herpes zoster infections and four localized herpes simplex infections.5 Many isolated cases of other viral infections e.g. CMV, VZV, West Nile virus, influenza A, JC virus, BK virus, parvovirus, and enterovirus have been associated with rituximab use (Table 3).5

Upper respiratory tract viral infections were most frequently reported, however in most studies infection sites were not specified. In a review of 64 cases of severe viral infection after rituximab treatment, the most frequently experienced viral infections were HBV (39.1%, n = 25), CMV (23.4%, n = 15), VZV (9.4%, n = 6), and others (28.1%, n = 18).5

In conclusion, it is still unclear whether rituximab adds to the risk of viral infection above that conferred by chemotherapy alone; this association has been studied mainly with particular viral infections including HBV, hepatitis C virus (HCV), herpes virus, and JC virus infection.

10. HBV reactivation

A recent review of the literature revealed that the most frequent viral infection complicating rituximab therapy for lymphoma was hepatitis B infection. HBV reactivation accounted for 39% of the reported cases, resulting in a high mortality of 52% due to hepatic failure.5,77,124 There are increasing reports of HBV reactivation following rituximab therapy, either when used alone or in combination with chemotherapy.125 While the addition of rituximab to CHOP chemotherapy may increase the risk of HBV reactivation, the precise magnitude of the increase is not clear with the available data.80,82,85–89,107,120 The use of rituximab in hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg)-positive patients can be continued provided they receive a prophylactic antiviral for a prolonged duration (up to 6 months) after cessation of chemotherapy.80

With the recent increase in rituximab use, HBV reactivation has been increasingly reported, even in patients who were thought to have cleared HBV (Table 3).80,92 In a recent study of lymphoma patients with prior resolved hepatitis B, among HBsAg-negative/anti-hepatitis B core (HBc)-positive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) patients treated with R-CHOP, 25% developed HBV reactivation.122

In addition to the use of rituximab, other potential factors associated with HBV reactivation include the absence of anti-HBs and male sex.5,77,124 In one report it was shown that R-CHOP therapy for lymphoma can increase the levels of serum HBV DNA and the risk of intrafamilial HBV infection when given to HBV carriers.126 Therefore, HBV reactivation may occur in the setting of rituximab use, and close monitoring of HBV DNA and liver function testing during rituximab therapy for at least 6 months after the completion of administration is required, with an alternative approach of prophylactic antiviral therapy to prevent this potentially fatal condition.

11. HCV reactivation

Rituximab-related liver dysfunction has not been described in HCV-positive patients receiving rituximab combination chemotherapy.127 Rituximab was reported to increase HCV viral load and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels in patients with HCV-related cryoglobulinemia (ALT was increased 10-fold and HCV viral load was increased 10-fold in one case)128 and lymphoma (ALT was increased 25-fold in one case and HCV viral load was increased 5–10-fold in five cases).129 Therefore, combined use of rituximab with chemotherapy poses an additional risk for exacerbation of HCV infection.

The influence of rituximab on HCV replication is not well understood. In one case, rituximab therapy for gastric cancer in a renal transplant recipient with chronic hepatitis C was complicated by cholestatic injury, an active hepatitis C replication with very high HCV RNA levels (increase of 1000-fold in HCV viral load after rituximab), and liver insufficiency.129 In two patients who underwent ABO-incompatible renal transplantation and who received rituximab and had positive HCV RNA, cholestatic hepatitis C did not occur, but double-filtration plasmapheresis (DFPP) and cyclosporine failed to reduce hepatitis C viremia.130 Another patient with refractory thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura and membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis successfully treated with rituximab developed hepatitis C virus reactivation.93 In another study of five HCV-infected patients with B-cell NHL undergoing treatment with rituximab-combination, all patients showed a significant increase in serum HCV RNA levels (at least 3-fold) with no occurrence of liver dysfunction.131 Two of these patients received regimens without prednisone, suggesting that increased HCV viremia was associated not only with corticosteroid use, but also with anticancer agents or rituximab.132 On the other hand, in one study, all seven patients who were HCV RNA-positive at the time of rituximab therapy for the treatment of transplant glomerulopathy, did not have significantly increased HCV RNA viremia or elevated levels of liver enzymes in the follow-up.63

In another report, 35 HCV-positive patients with DLBCL received rituximab-containing combination regimens without any hepatotoxicity; considering the short follow-up period of their study such toxicity might have been missed.132 In another study of 44 HCV-positive patients with DLBCL treated with CHOP/CHOP-like regimens +− rituximab, high viral load and evidence of active hepatitis or cirrhosis at liver biopsy was associated with more frequent hepatic failure under treatment and reduced survival.132 Concomitant administration of R-CHOP plus anti-HCV treatment with pegylated interferon and ribavirin in four patients with HCV infection and DLBCL in the same study, resulted in excessive hematological toxicity.132 On the other hand, sequential treatment with pegylated interferon plus ribavirin 3 months after chemotherapy in three patients was found effective, better tolerated, and resulted in a high rate of complete virus clearance.133,134

The lack of correlation between levels of HCV RNA and the extent of liver damage and variability of HCV RNA levels over time, limit strong conclusions regarding the association of rituximab with HCV infection and liver damage.128,129,132 Kamar et al. found that rituximab therapy was not associated with a flare-up of chronic HCV infection in kidney transplant patients.61 Finally, although HCV viral load can increase after rituximab treatment,5 rituximab has been successfully used in HCV-associated cryoglobulinemia.5,128 This indicates that rituximab may be an effective treatment for immunologic manifestations of HCV infection.

In summary, the association of rituximab with HCV infection remains very complex since rituximab may exacerbate HCV infection, but in other cases it has been used for the treatment of HCV-related autoimmune phenomena. Physicians should monitor HCV viral load during rituximab therapy.

12. Herpes infection

Infections with herpes viruses such as CMV, VZV, and HSV have been described in association with rituximab use.5,19,21,41,44,45,59,63, 68–74,101,112 The most common herpes virus associated with rituximab is CMV and 26 cases have been described in the literature.5,19,21,59,63,68–71,101 In cases where CMV infection was specified, CMV enterocolitis, pneumonitis, and esophagitis were described (Table 3).

EBV infection has not been associated with rituximab to date. In one case with disseminated EBV infection, rituximab was ineffective in treating central nervous system infection with EBV.5 Other data suggest that EBV persists in cell populations not depleted by rituximab, such as EBV-infected oropharyngeal epithelial cells.135 Finally, 13 cases of infection with VZV5,41,44,45,72–74,101,112 and five cases of HSV41,63,75 have been described in association with rituximab therapy (Table 3). However, data from randomized controlled studies are needed to establish the association of rituximab use with the development of infections with herpes viruses.

13. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML)––JC virus

As of July 29, 2008, there were 76 reports in the manufacturer’s global safety database of confirmed or suspected PML in patients receiving rituximab for any indication (69 in oncology indications, one autoimmune hemolytic anemia, five in other autoimmune disorders, and one in an unknown indication).136 In one study rituximab was associated with a delay in the development of PML in HIV-negative patients with lymphoproliferative disorders treated with rituximab compared to patients treated with similar chemotherapeutic regimens without rituximab.137 According to a report by the FDA, a total of 23 cases of PML have been documented in patients on rituximab for hematological malignancies mostly in combination with chemotherapy or stem cell transplantation.1

Carson et al. reported 57 rituximab-associated PML cases in HIV-negative patients. Median time from last rituximab dose to PML diagnosis was 5.5 months (range 0.3–66.0) and the overall incidence of fatality was 90%.104 Kamar et al. showed that the incidence of JC viremia in rituximab-treated solid-organ transplant patients was 5.5%.61 The exact role of rituximab in the development of PML is unclear, as humoral immunity is thought to be of little importance in the latency of JC virus, although the loss of the B-cell antigen presenting cell function may be critical. The effect of rituximab on T-lymphocyte function as a potential mechanism of JC virus reactivation remains an area of active inquiry.138 Thus, the causal relationship between PML and rituximab remains unclear.

14. Fungal infections

Humoral immune deficiencies increase the risk for opportunistic fungal infection, and a reduction in antigen-specific cellular immunity impairs host protection against fungi. A recent study demonstrated that the addition of rituximab to CHOP increased the risk of fungal infection in a very elderly population.30 Pneumocystis jiroveci (previously known as Pneumocystis carinii) pneumonia (PCP) may occur in a variety of hematological diseases.115

Although PCP has not been reported in the rituximab treatment arm of large RCTs, based on data from small trials, retrospective studies, and case reports, 13 cases of PCP have been described in the literature in association with rituximab use in patients with hematological malignancies.30,42,63,113–116 Although these patients were also receiving other immunosuppressive medications, the strong temporal relationship between the rituximab infusions and the onset of the disease suggests that rituximab played a decisive role in the development of the opportunistic infection. Another study showed that the addition of rituximab to CHOP-like regimens, such as CHOP and CHOP-14, with or without etoposide, increased the incidence of PCP (13% in the rituximab arm vs. 4% in the other arm).30 No cases of PCP have been reported in patients with autoimmune disorders receiving rituximab as treatment.

Four case reports have been published that describe the occurrence of aspergillosis; one in a patient with autoimmune thrombocytopenic purpura and two in patients with post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders that were treated with rituximab.139 Four cases of Candida infection have also been described in association with use of rituximab.16,117–119 As all these patients received extensive additional immunosuppressive treatment, the exact role of rituximab is difficult to define. However, experiments in B-cell deficient mice are in line with a mild impairment in antifungal immunity.139

The possibly increased susceptibility to P. jiroveci and fungal infection with the use of rituximab may suggest the need to administer prophylactic treatment with antifungals and/or trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole during R-CHOP therapy. Due to the high incidence of Aspergillus and Candida infection, it may be more appropriate to use itraconazole or posaconazole rather than fluconazole as primary prophylaxis in these patients.140

15. Parasitic infections

Parasitic infections have rarely been described in association with rituximab use, although eight cases of babesiosis were described in one study. The authors concluded that rituximab effects on naive B cells that are responsible for antibody production in response to a new babesial infection could be involved.121 More data are needed to elucidate the possible association of infliximab use with parasitic infections.

16. Immunization effects

The response to vaccination after rituximab could be reduced since rituximab causes B-cell depletion;141 it is recommended that any vaccinations should be given before initiating treatment. A single study found that humoral responses to influenza vaccination were lower among patients treated with rituximab compared to RA patients who had received non-biological DMARDs and healthy controls.142 Data from a recent RCT suggest that patients with RA treated with rituximab can be effectively and safely vaccinated, but to maximize response, polysaccharide and primary immunizations should be administered prior to rituximab infusions.143 A recent clinical trial showed that rituximab reduces humoral responses following influenza vaccination in RA patients, with a modestly restored response 6–10 months after rituximab administration.143 Recent studies suggest that anti-tetanus immune responses are decreased shortly after rituximab treatment, while immune responses to neoantigens and polysaccharides, which are B-cell-dependent, are decreased following rituximab treatment.142

Despite the suboptimal response, appropriate vaccination (such as against influenza or pneumococcus) should be administered when indicated.142,143 Due to the paucity of data on the use of live attenuated vaccines while on rituximab, such vaccines should preferably be administered prior to rituximab use.

17. Limitations

We identified certain limitations in the studies that have examined the association of rituximab with infection. Firstly, the true infection rates may be higher than those reported in clinical trials since minor infections (grade 1 and grade 2) are possibly overlooked both by the patients and the doctors, and are under-reported. In certain reports (mostly case reports) authors did not provide adequate data regarding the strength of association of rituximab with infection and thus we could not independently analyze the strength of evidence regarding this association in these cases. Furthermore, variances in reporting rates of neutropenia, immunoglobulin levels, infections as adverse events by the doctors, and the heterogeneity of the trials, the different patient selection criteria, and the different extent of bone marrow involvement by different subtypes of lymphomas may account for the differences in infection rates in clinical trials.

18. Conclusions

In conclusion, recent data show that rituximab maintenance therapy significantly increases the risk of both infection and neutropenia in patients with lymphoma or other hematological malignancies. Novel prophylaxis and/or pre-emptive treatment strategies should be tailored for these patients when treated with rituximab. On the other hand, data available to date do not indicate an increased risk of infection when using rituximab compared with concurrent control treatments in RA. However, there is a lack of sufficient long-term data to allow such a statement to be definitively made and caution regarding infections should continue to be exercised, especially in patients who have received repeated courses of rituximab, are receiving other immunosuppressants concurrently, and in those whose immunoglobulin levels have fallen below the normal range. Further studies are needed to clarify the association of rituximab with infection. Education of physicians and patients about the association of rituximab with infectious complications, monitoring of absolute neutrophil count and immunoglobulin levels, identification of high-risk groups for the development of infectious complications, and timely vaccination of these groups are clearly needed.

KEY POINTS.

Clinical trials have shown conflicting results regarding the association of rituximab with infections. However, clinical experience regarding the association of rituximab with different types of infection is lacking.

An increased incidence of infections in patients with lymphomas and rheumatoid arthritis being treated with rituximab has been recently reported.

Education of physicians and patients about the association of rituximab with infectious complications, monitoring of absolute neutrophil count and immunoglobulin levels, identification of high risk groups for development of infectious complications and timely vaccination of these groups are needed

Abbreviations:

- CHOP

cyclophosphamide doxorubicin vincristine and prednisone

- CLL

chronic lymphocytic leukemia

- CVP

cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone

- CI

confidence intervals

- CMV

cytomegalovirus

- CNS

central nervous system

- DLBCL

diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

- dcSSc

diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis

- DMARD

Disease Modifying Antirheumatic Drug

- EBV

Epstein Barr Virus

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration

- FCM

fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and mitoxantrone

- G-CSF

Granulocyte Colony Stimulating Factor

- HIV

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

- HBV

Hepatitis B virus

- HCV

Hepatitis C virus

- HEV

Hepatitis E virus

- HbsAg

Hepatitis B surface antigen

- HDMP

High dose methylprednisolone

- HIV

human immunodeficiency virus

- HSV

Herpes Simplex Virus

- HSCT

hematological stem cell transplantation

- MTX

methotrexate

- MCP

mitoxantrone, chlorambucil, and prednisolone

- ND

Not determined

- NHL

non-Hodgkin lymphoma

- NR

not reported

- OI

Opportunistic infections

- PCP

Pneumocystis Carinii Pneumonia

- PML

progressive multifocal leucoencephalopathy (PML)

- R

rituximab

- RA

rheumatoid arthritis

- RCT

randomized controlled trial

- RR

relative risk

- RSV

respiratory syncytial virus

- SL

small lymphocytic lymphoma

- SIE

serious infection events

- SLE

systematic lupus erythematosus

- TNF

tumor necrosis factor

- VZV

Varicella Zoster Virus

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

- [1].US Food and Drug Administration. FDA alert: rituximab (marketed as Rituxan). Available at: http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/Postmarket-DrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/ucm109106.htm (accessed August 1, 2009).

- [2].Coiffier B Treatment of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: a look over the past decade. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma 2006;7(Suppl 1):S7–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Czuczman MS, Weaver R, Alkuzweny B, Berlfein J, Grillo-Lopez AJ. Prolonged clinical and molecular remission in patients with low-grade or follicular non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma treated with rituximab plus CHOP chemotherapy: 9-year follow-up. J Clin Oncol 2004;22:4711–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Dass S, Vital EM, Emery P. Rituximab: novel B-cell depletion therapy for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2006;7:2559–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Aksoy S, Harputluoglu H, Kilickap S, Dede DS, Dizdar O, Altundag K, Barista I. Rituximab-related viral infections in lymphoma patients. Leuk Lymphoma 2007;48:1307–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Lund FE, Hollifield M, Schuer K, Lines JL, Randall TD, Garvy BA. B cells are required for generation of protective effector and memory CD4 cells in response to Pneumocystis lung infection. J Immunol 2006;176:6147–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Sfikakis PP, Boletis JN, Lionaki S, Vigklis V, Fragiadaki KG, Iniotaki A, et al. Remission of proliferative lupus nephritis following B cell depletion therapy is preceded by down-regulation of the T cell costimulatory molecule CD40 ligand: an open-label trial. Arthritis Rheum 2005;52:501–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Sfikakis PP, Souliotis VL, Fragiadaki KG, Moutsopoulos HM, Boletis JN, Theofilopoulos AN. Increased expression of the FoxP3 functional marker of regulatory T cells following B cell depletion with rituximab in patients with lupus nephritis. Clin Immunol 2007;123:66–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Lazdina U, Alheim M, Nystrom J, Hultgren C, Borisova G, Sominskaya I, et al. Priming of cytotoxic T cell responses to exogenous hepatitis B virus core antigen is B cell dependent. J Gen Virol 2003;84:139–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Cattaneo C, Spedini P, Casari S, Re A, Tucci A, Borlenghi E, et al. Delayed-onset peripheral blood cytopenia after rituximab: frequency and risk factor assessment in a consecutive series of 77 treatments. Leuk Lymphoma 2006;47:1013–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Castagnola E, Dallorso S, Faraci M, Morreale G, Di Martino D, Cristina E, et al. Long-lasting hypogammaglobulinemia following rituximab administration for Epstein–Barr virus-related post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease preemptive therapy. J Hematother Stem Cell Res 2003;12:9–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Lim SH, Esler WV, Zhang Y, Zhang J, Periman PO, Burris C, et al. B-cell depletion for 2 years after autologous stem cell transplant for NHL induces prolonged hypogammaglobulinemia beyond the rituximab maintenance period. Leuk Lymphoma 2008;49:152–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Lim SH, Zhang Y, Wang Z, Esler WV, Beggs D, Pruitt B, et al. Maintenance rituximab after autologous stem cell transplant for high-risk B-cell lymphoma induces prolonged and severe hypogammaglobulinemia. Bone Marrow Transplant 2005;35:207–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Tirelli U, Spina M, Jaeger U, Nigra E, Blanc PL, Liberati AM, et al. Infusional CDE with rituximab for the treatment of human immunodeficiency virus-associated non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: preliminary results of a phase I/II study. Recent Results Cancer Res 2002;159:149–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Kimby E. Tolerability and safety of rituximab (MabThera). Cancer Treat Rev 2005;31:456–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Verschuuren EA, Stevens SJ, van Imhoff GW, Middeldorp JM, de Boer C, Koeter G, et al. Treatment of posttransplant lymphoproliferative disease with rituximab: the remission, the relapse, and the complication. Transplantation 2002;73:100–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Saikia TK, Menon H, Advani SH. Prolonged neutropenia following anti CD20 therapy in a patient with relapsed follicular non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and corrected with IVIG. Ann Oncol 2001;12:1493–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Yokohama A, Tsukamoto N, Uchiumi H, Handa H, Matsushima T, Karasawa M, et al. Durable remission induced by rituximab-containing chemotherapy in a patient with primary refractory Burkitt’s lymphoma. Ann Hematol 2004;83: 120–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Lee MY, Chiou TJ, Hsiao LT, Yang MH, Lin PC, Poh SB, et al. Rituximab therapy increased post-transplant cytomegalovirus complications in Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma patients receiving autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Ann Hematol 2008;87:285–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Lin PC, Hsiao LT, Poh SB, Wang WS, Yen CC, Chao TC, et al. Higher fungal infection rate in elderly patients (more than 80 years old) suffering from diffuse large B cell lymphoma and treated with rituximab plus CHOP. Ann Hematol 2007;86:95–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Unluturk U, Aksoy S, Yonem O, Bayraktar Y, Tekuzman G. Cytomegalovirus gastritis after rituximab treatment in a non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma patient. World J Gastroenterol 2006;12:1978–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Cabanillas F, Liboy I, Pavia O, Rivera E. High incidence of non-neutropenic infections induced by rituximab plus fludarabine and associated with hypogammaglobulinemia: a frequently unrecognized and easily treatable complication. Ann Oncol 2006;17:1424–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Aksoy S, Dizdar O, Hayran M, Harputluoglu H. Infectious complications of rituximab in patients with lymphoma during maintenance therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Leuk Lymphoma 2009;50:357–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Furst DE, Breedveld FC, Kalden JR, Smolen JS, Burmester GR, Sieper J, et al. Updated consensus statement on biological agents for the treatment of rheumatic diseases, 2007. Ann Rheum Dis 2007;66(Suppl 3):iii2–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Furst DE, Keystone EC, Kirkham B, Kavanaugh A, Fleischmann R, Mease P, et al. Updated consensus statement on biological agents for the treatment of rheumatic diseases, 2008. Ann Rheum Dis 2008;67(Suppl 3). iii2–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Rafailidis PI, Kakisi OK, Vardakas K, Falagas ME. Infectious complications of monoclonal antibodies used in cancer therapy: a systematic review of the evidence from randomized controlled trials. Cancer 2007;109:2182–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Gurcan HM, Keskin DB, Stern JN, Nitzberg MA, Shekhani H, Ahmed AR. A review of the current use of rituximab in autoimmune diseases. Int Immunopharmacol 2009;9:10–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Vidal L, Gafter-Gvili A, Leibovici L, Shpilberg O. Rituximab as maintenance therapy for patients with follicular lymphoma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009. (2) CD006552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Eve HE, Linch D, Qian W, Ross M, Seymour JF, Smith P, et al. Toxicity of fludarabine and cyclophosphamide with or without rituximab as initial therapy for patients with previously untreated mantle cell lymphoma: results of a randomised phase II study. Leuk Lymphoma 2009;50:211–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Kaplan LD, Lee JY, Ambinder RF, Sparano JA, Cesarman E, Chadburn A, et al. Rituximab does not improve clinical outcome in a randomized phase 3 trial of CHOP with or without rituximab in patients with HIV-associated non-Hodgkin lymphoma: AIDS-Malignancies Consortium Trial 010. Blood 2005;106: 1538–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Lenz G, Dreyling M, Hoster E, Wormann B, Duhrsen U, Metzner B, et al. Immunochemotherapy with rituximab and cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone significantly improves response and time to treatment failure, but not long-term outcome in patients with previously untreated mantle cell lymphoma: results of a prospective randomized trial of the German Low Grade Lymphoma Study Group (GLSG). J Clin Oncol 2005;23:1984–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Hiddemann W, Kneba M, Dreyling M, Schmitz N, Lengfelder E, Schmits R, et al. Frontline therapy with rituximab added to the combination of cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (CHOP) significantly improves the outcome for patients with advanced-stage follicular lymphoma compared with therapy with CHOP alone: results of a prospective randomized study of the German Low-Grade Lymphoma Study Group. Blood 2005;106:3725–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Feugier P, Van Hoof A, Sebban C, Solal-Celigny P, Bouabdallah R, Ferme C, et al. Long-term results of the R-CHOP study in the treatment of elderly patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a study by the Groupe d’Etude des Lymphomes de l’Adulte. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:4117–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Coiffier B, Lepage E, Briere J, Herbrecht R, Tilly H, Bouabdallah R, et al. CHOP chemotherapy plus rituximab compared with CHOP alone in elderly patients with diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med 2002;346:235–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Habermann TM, Weller EA, Morrison VA, Gascoyne RD, Cassileth PA, Cohn JB, et al. Rituximab-CHOP versus CHOP alone or with maintenance rituximab in older patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:3121–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Pfreundschuh M, Trumper L, Osterborg A, Pettengell R, Trneny M, Imrie K, et al. CHOP-like chemotherapy plus rituximab versus CHOP-like chemotherapy alone in young patients with good-prognosis diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma: a randomised controlled trial by the MabThera International Trial (MInT) Group. Lancet Oncol 2006;7:379–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Forstpointner R, Dreyling M, Repp R, Hermann S, Hanel A, Metzner B, et al. The addition of rituximab to a combination of fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, mitoxantrone (FCM) significantly increases the response rate and prolongs survival as compared with FCM alone in patients with relapsed and refractory follicular and mantle cell lymphomas: results of a prospective randomized study of the German Low-Grade Lymphoma Study Group. Blood 2004;104: 3064–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Marcus R, Imrie K, Belch A, Cunningham D, Flores E, Catalano J, et al. CVP chemotherapy plus rituximab compared with CVP as first-line treatment for advanced follicular lymphoma. Blood 2005;105:1417–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Herold M, Dolken G, Fiedler F, Franke A, Freund M, Helbig W, et al. Randomized phase III study for the treatment of advanced indolent non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas (NHL) and mantle cell lymphoma: chemotherapy versus chemotherapy plus rituximab. Ann Hematol 2003;82:77–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Dungarwalla M, Evans SO, Riley U, Catovsky D, Dearden CE, Matutes E. High dose methylprednisolone and rituximab is an effective therapy in advanced refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia resistant to fludarabine therapy. Haematologica 2008;93:475–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Del Poeta G, Del Principe MI, Buccisano F, Maurillo L, Capelli G, Luciano F, et al. Consolidation and maintenance immunotherapy with rituximab improve clinical outcome in patients with B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer 2008;112:119–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Ennishi D, Terui Y, Yokoyama M, Mishima Y, Takahashi S, Takeuchi K, et al. Increased incidence of interstitial pneumonia by CHOP combined with rituximab. Int J Hematol 2008;87:393–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].van Oers MH, Klasa R, Marcus RE, Wolf M, Kimby E, Gascoyne RD, et al. Rituximab maintenance improves clinical outcome of relapsed/resistant follicular non-Hodgkin lymphoma in patients both with and without rituximab during induction: results of a prospective randomized phase 3 inter-group trial. Blood 2006;108:3295–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Ghielmini M, Schmitz SF, Cogliatti S, Bertoni F, Waltzer U, Fey MF, et al. Effect of single-agent rituximab given at the standard schedule or as prolonged treatment in patients with mantle cell lymphoma: a study of the Swiss Group for Clinical Cancer Research (SAKK). J Clin Oncol 2005;23:705–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Hainsworth JD, Litchy S, Barton JH, Houston GA, Hermann RC, Bradof JE, et al. Single-agent rituximab as first-line and maintenance treatment for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia or small lymphocytic lymphoma: a phase II trial of the Minnie Pearl Cancer Research Network. J Clin Oncol 2003; 21:1746–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Morrison VA, Rai KR, Peterson BL, Kolitz JE, Elias L, Appelbaum FR, et al. Impact of therapy with chlorambucil, fludarabine, or fludarabine plus chlorambucil on infections in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia: Intergroup Study Cancer and Leukemia Group B 9011. J Clin Oncol 2001;19:3611–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Byrd JC, McGrail LH, Hospenthal DR, Howard RS, Dow NA, Diehl LF. Herpes virus infections occur frequently following treatment with fludarabine: results of a prospective natural history study. Br J Haematol 1999;105:445–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Kanbayashi Y, Nomura K, Fujimoto Y, Yamashita M, Ohshiro M, Okamoto K, et al. Risk factors for infection in haematology patients treated with rituximab. Eur J Haematol 2009;82:26–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Lafyatis R, Kissin E, York M, Farina G, Viger K, Fritzler MJ, et al. B cell depletion with rituximab in patients with diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheum 2009;60:578–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Genovese MC, Breedveld FC, Emery P, Cohen S, Keystone E, Matteson EL, et al. Safety of biologic therapies following rituximab treatment in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:1894–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Emery P, Fleischmann R, Filipowicz-Sosnowska A, Schechtman J, Szczepanski L, Kavanaugh A, et al. The efficacy and safety of rituximab in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis despite methotrexate treatment: results of a phase IIB randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging trial. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:1390–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Edwards JC, Szczepanski L, Szechinski J, Filipowicz-Sosnowska A, Emery P, Close DR, et al. Efficacy of B-cell-targeted therapy with rituximab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med 2004;350:2572–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Cohen SB, Emery P, Greenwald MW, Dougados M, Furie RA, Genovese MC, et al. Rituximab for rheumatoid arthritis refractory to anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy: results of a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III trial evaluating primary efficacy and safety at twenty-four weeks. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:2793–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Keystone E, Fleischmann R, Emery P, Furst DE, van Vollenhoven R, Bathon J, et al. Safety and efficacy of additional courses of rituximab in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: an open-label extension analysis. Arthritis Rheum 2007;56:3896–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Furst DE. The risk of infections with biologic therapies for rheumatoid arthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2010;39:327–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Salliot C, Dougados M, Gossec L. Risk of serious infections during rituximab, abatacept and anakinra treatments for rheumatoid arthritis: meta-analyses of randomised placebo-controlled trials. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:25–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Scemla A, Thervet E, Martinez F. Safety of rituximab therapy for prevention or treatment of acute humoral rejection after renal transplantation. Am J Transplant 2008;9(Suppl 2):558. [Google Scholar]

- [58].Tsapepas DS, Aull MJ, Dadhnia D, Kapur S. Risk of infection in kidney-transplant recipients treated with rituximab. Am J Transplant 2008;9(Suppl 2):564. [Google Scholar]

- [59].Grim SA, Pham T, Thielke J, Sankary H, Oberholzer J, Benedetti E, et al. Infectious complications associated with the use of rituximab for ABO-incompatible and positive cross-match renal transplant recipients. Clin Transplant 2007;21:628–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Nishida H, Ishida H, Tanaka T, Amano H, Omoto K, Shirakawa H, et al. Cytomegalovirus infection following renal transplantation in patients administered low-dose rituximab induction therapy. Transpl Int 2009;22: 961–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Kamar N, Milioto O, Puissant-Lubrano B, Esposito L, Pierre MC, Mohamed AO, et al. Incidence and predictive factors for infectious disease after rituximab therapy in kidney-transplant patients. Am J Transplant 2010;10:89–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Lovric S, Erdbruegger U, Kumpers P, Woywodt A, Koenecke C, Wedemeyer H, et al. Rituximab as rescue therapy in anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis: a single-centre experience with 15 patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2009;24:179–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Rostaing L, Guilbeau-Frugier C, Fort M, Mekhlati L, Kamar N. Treatment of symptomatic transplant glomerulopathy with rituximab. Transpl Int 2009; 22:906–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Zaja F, Bacigalupo A, Patriarca F, Stanzani M, Van Lint MT, Fili C, et al. Treatment of refractory chronic GVHD with rituximab: a GITMO study. Bone Marrow Transplant 2007;40:273–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Arber C, Buser A, Heim D, Weisser M, Tyndall A, Tichelli A, et al. Septic polyarthritis with Ureaplasma urealyticum in a patient with prolonged agammaglobulinemia and B-cell aplasia after allogeneic HSCT and rituximab pretreatment. Bone Marrow Transplant 2007;40:597–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Chen YC, Jou R, Huang WL, Huang ST, Liu KC, Lay CJ, et al. Bacteremia caused by Mycobacterium wolinskyi. Emerg Infect Dis 2008;14:1818–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Lutt JR, Pisculli ML, Weinblatt ME, Deodhar A, Winthrop KL. Severe non-tuberculous mycobacterial infection in 2 patients receiving rituximab for refractory myositis. J Rheumatol 2008;35:1683–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Suzan F, Ammor M, Ribrag V. Fatal reactivation of cytomegalovirus infection after use of rituximab for a post-transplantation lymphoproliferative disorder. N Engl J Med 2001;345:1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Hirokawa M, Kawabata Y, Fujishima N, Yoshioka T, Sawada K. Prolonged reactivation of cytomegalovirus infection following successful rituximab therapy for Epstein–Barr virus-associated posttransplantation lymphoproliferative disorder. Int J Hematol 2007;86:291–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Lee KC, Chang CY, Chuang YC, Young MS, Huang CM, Yin WH, et al. Heart transplant coronary artery disease in Chinese recipients. Transplant Proc 2004;36:2380–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Stathis A, La Rosa S, Proserpio I, Micello D, Chini C, Pinotti G. Cytomegalovirus infection of endocrine system in a patient with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Report of a case Tumori 2009;95:119–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Aviles A, Castaneda C, Cleto S, Neri N, Huerta-Guzman J, Gonzalez M, et al. Rituximab and chemotherapy in primary gastric lymphoma. Cancer Biother Radiopharm 2009;24:25–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Bermudez A, Marco F, Conde E, Mazo E, Recio M, Zubizarreta A. Fatal visceral varicella-zoster infection following rituximab and chemotherapy treatment in a patient with follicular lymphoma. Haematologica 2000;85:894–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].McIlwaine LM, Fitzsimons EJ, Soutar RL. Inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion, abdominal pain and disseminated varicella-zoster virus infection: an unusual and fatal triad in a patient 13 months post rituximab and autologous stem cell transplantation. Clin Lab Haematol 2001;23:253–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Scheinpflug K, Schalk E, Reschke K, Franke A, Mohren M. Diabetes insipidus due to herpes encephalitis in a patient with diffuse large cell lymphoma. A case report Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes 2006;114:31–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Coiffier B, Hepatitis. B virus reactivation in patients receiving chemotherapy for cancer treatment: role of lamivudine prophylaxis. Cancer Invest 2006;24:548–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Yang SH, Kuo SH. Reactivation of hepatitis B virus during rituximab treatment of a patient with follicular lymphoma. Ann Hematol 2008;87:325–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Hui CK, Cheung WW, Zhang HY, Au WY, Yueng YH, Leung AY, et al. Kinetics and risk of de novo hepatitis B infection in HBsAg-negative patients undergoing cytotoxic chemotherapy. Gastroenterology 2006;131:59–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]