Abstract

Objective

We report a case of pituitary apoplexy (PA) with negative radiographic findings for PA and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis consistent with neutrophilic meningitis. PA is a rare endocrinopathy requiring prompt diagnosis and treatment. Presentation with acute neutrophilic meningitis is uncommon.

Methods

The diagnostic modalities included pituitary function tests (adrenocorticotropic hormone, thyroid-stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone, prolactin), brain computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and CSF analysis.

Results

A 67-year-old man presented with worsening headache, nausea, and retching. He was somnolent with an overall normal neurologic examination other than a peripheral vision defect in the left eye. MRI showed a pituitary mass bulging into the suprasellar cistern with optic chiasm elevation, consistent with pituitary macroadenoma. Laboratory evaluation revealed decreased levels of adrenocorticotropic hormone, random cortisol, thyroid-stimulating hormone, thyroxine, luteinizing hormone, and testosterone. He had worsening encephalopathy with left eye ptosis and decreased vision, prompting a repeat computed tomography and MRI, showing no interval change in the pituitary adenoma or evidence of bleeding. CSF analysis revealed a leukocyte count of 1106/mm3 (89% neutrophils), a total protein level of 138 mg/dL, red blood cell count of 2040/mm3 without xanthochromia, and glucose level of 130 mg/dL. The CSF culture result was negative. Transsphenoidal resection revealed a necrotic pituitary adenoma with apoplexy.

Conclusions

Including PA in the differential diagnosis of acute headache is important, particularly in patients with visual disturbances. PA can present with sterile meningitis, mimicking acute bacterial meningitis. While neuroimaging can help detect PA, the diagnosis of PA remains largely clinical.

Key words: pituitary apoplexy, pituitary adenoma, sterile meningitis, pituitary tumor, macroadenoma

Abbreviations: CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; CT, computed tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; PA, pituitary apoplexy

Introduction

Pituitary apoplexy (PA) is a rare clinical syndrome that classically presents with findings of acute severe headache, ophthalmoplegia, vision loss, and pituitary insufficiency. While it is uncommon, PA can present with findings clinically indistinguishable from acute bacterial meningitis.1 The mechanism of this finding is the expulsion of hemorrhagic or necrotic materials through the sellar diaphragmatic aperture that can lead to meningeal irritation, thereby causing chemical meningitis.2 A false diagnosis of acute bacterial meningitis can be made because cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis may show neutrophilic predominance.

Case Report

A 67-year-old man with a history of hypertension, diabetes mellitus type 2, and chronic kidney disease presented to our hospital with a 2-week history of bilateral frontal headache, nausea, and retching. On admission, the patient was somnolent, with a Glasgow coma scale assessment score of 13 (eye, 2; verbal, 5; and motor, 6). The neurologic examination was benign overall, with normal ocular motion and intact cranial nerves, except for a peripheral vision defect in the left eye. There was no nuchal rigidity. Hemianopsia was not present, although a minor visual field defect could not be fully assessed due to the patient’s decreased level of consciousness.

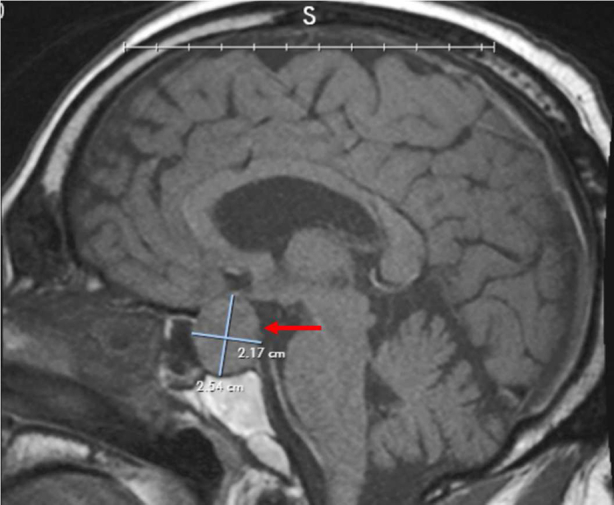

Laboratory evaluation revealed a normal white blood cell count (6490/μL, 55.5% neutrophils) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (16 mm/hour) and an elevated C-reactive protein level (17.6 mg/dL [normal, <0.49 mg/dL]). Plain head computed tomography (CT) showed no intracranial hemorrhage but revealed sellar enlargement caused by a well-circumscribed ovoid mass, consistent with a pituitary macroadenoma. Sellar magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed an ovoid, well-circumscribed pituitary mass, roughly 2.0 × 1.9 × 2.4 cm, bulging into the suprasellar cistern and minimally elevating the optic chiasm (Fig. 1) without evidence of cavernous sinus invasion.

Fig. 1.

Magnetic resonance imaging showing a pituitary macroadenoma (2.17 × 2.54 cm) minimally elevating the optic chiasm and bulging into the right cavernous sinus (arrow).

Analysis of pituitary function revealed a low adrenocorticotropic hormone concentration of 2.8 pg/mL (normal, 7.2-63.3 pg/mL), a random cortisol level of 1.7 μg/dL (normal, 2.9-19.4 μg/dL), a thyroid-stimulating hormone of <0.1 μIU/mL (normal, 0.35-4.9 μIU/mL), a thyroxine level of 0.72 ng/dL (normal, 0.77-1.48 ng/dL), a luteinizing hormone of 0.8 IU/L (normal, 1.7-8.6 IU/L), and a total testosterone level of <3 ng/dL (normal, 300-720 ng/dL), with normal prolactin, insulin-like growth factor 1, and growth hormone levels.

On hospital day 2, the patient started experiencing left eye ptosis, associated with decreased vision in the ipsilateral eye and progressive confusion. Repeat neuroimaging, including a noncontrast CT scan and MRI, showed no interval change in the pituitary adenoma and no evidence of bleeding. A lumbar puncture revealed an increased leukocyte count of 1106/mm³ with 89% neutrophilic granulocytes and increased total protein of 138 mg/dL (normal, 15-40 mg/dL), red blood cell count of 2040/mm3 without xanthochromia, and glucose of 130 mg/dL (normal 40-70 mg/dL). Empirical vancomycin, ceftriaxone, ampicillin, acyclovir, and dexamethasone were started for suspected bacterial meningitis. A Gram stain of the CSF showed numerous neutrophils, but the culture was negative.

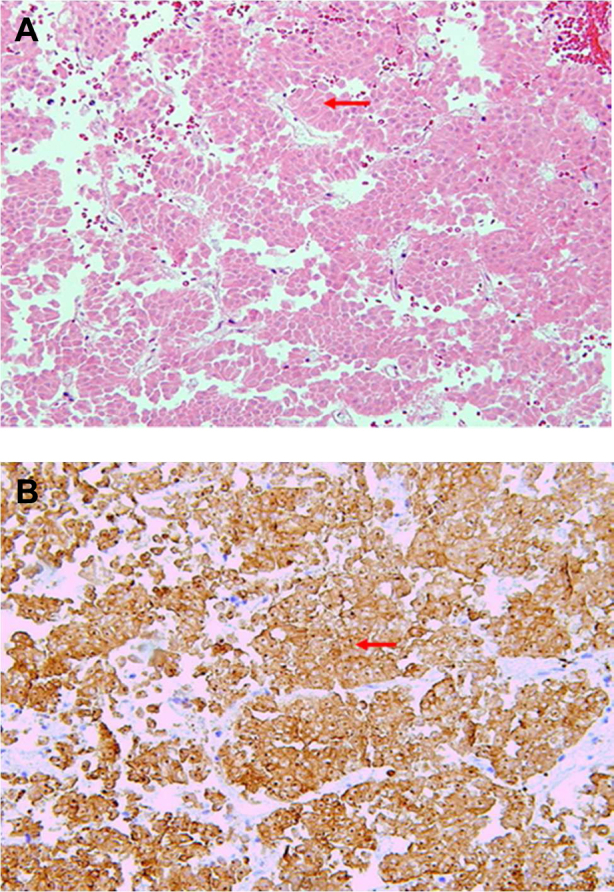

Given the sudden visual impairment and neurologic deterioration, the patient underwent transsphenoidal resection of the tumor with free nasal mucosal graft reconstruction. A histopathological evaluation showed necrotic cells (Fig. 2 A) and nuclei that reacted with antibodies to synaptophysin on immunoperoxidase staining (Fig. 2 B), which confirmed the diagnosis of necrotic pituitary adenoma.

Fig. 2.

A, Hematoxylin and eosin stain showing a necrotic pituitary adenoma lacking the characteristic hematoxylin staining pattern of the nuclei (arrow). B, Necrotic pituitary tumor demonstrating characteristic immunoperoxidase staining of synaptophysin (arrow).

Postoperatively, his neurologic examination greatly improved with resolution of ptosis and improvement to his vision. He was discharged 1 week after his neurosurgical procedure and is currently doing well 5 months after his diagnosis. He remains on hormone supplementation.

Discussion

PA is a rare but potentially fatal condition that requires prompt diagnosis and treatment. It typically manifests as a sudden onset of headache, visual disturbance, encephalopathy, and endocrine dysfunction due to acute hemorrhage or ischemic infarction of the pituitary gland. While macroadenomas and prolactinomas are more likely to undergo changes consistent with apoplexy, PA can happen in a normal pituitary gland or microadenomas.3,4 While PA may occur without inciting factors, some studies show associations with several possible trigger factors, including hypertension, surgical procedures, head trauma, hypothalamic/pituitary stimulation tests, anticoagulation use, and radiotherapy. These factors can be identified in 10% to 40% of cases of PA.4, 5, 6 Although there are multiple cases of PA described among patients of different age categories, PA seems to be more prevalent in patients in their fifth to sixth decades of life.7 PA has a wide range of manifestations. A study investigated 64 patients with PA, concluding that headache was the most common symptom and was present in 93% of cases.3 Other common symptoms were vomiting (51%) and signs and symptoms of endocrinopathy, including fatigue, reduced libido, oligomenorrhea, and amenorrhea (35%). Visual abnormalities were common (62%) and included pupil abnormalities (20%), oculomotor nerve palsy (34%), abducens nerve palsies (22%), visual acuity changes (40%), and visual field cuts (35%).3,4,8

Most patients presenting with headache and findings suspicious of subarachnoid bleed or PA undergo a noncontrast CT scan on an emergent basis. The sensitivity of noncontrast CT ranges between 21% and 46%.7 MRI has a higher sensitivity (∼90%) in detecting PA. MRI performed in the acute stage of PA can frequently show areas of hyperintensity along the periphery of the tumor, best visualized on T1-weighted imaging. Another important imaging finding that is considered highly specific for PA is the thickening of the sphenoid sinus mucosa.9 Because PA frequently presents with symptoms that may overlap with presentations of subarachnoid hemorrhage and meningitis, the diagnosis of PA can often be challenging. Moreover, this leads to delayed diagnosis and treatment of PA, causing an increased rate of adverse outcomes.3 CSF analysis may not be helpful in differentiating between suspected meningoencephalitis and PA. In some cases of PA, chemical meningoencephalitis may be present due to leakage of blood and necrotic debris into the subarachnoid space.1,10 In our patient’s case, while CSF studies were markedly abnormal, with findings suggestive of bacterial meningitis, the Gram stain was negative for microorganisms and the CSF culture did not show evidence of bacterial growth. Therefore, we concluded that the abnormal findings of the CSF examination were attributed to chemical meningitis.

There are a handful of published cases describing the presence of inflammatory changes in the CSF of patients with PA. The Table provides a summary of 10 previously published cases. Most of them describe middle-aged male patients. In the majority of the cases, the imaging findings resulted in a PA diagnosis. Lastly, the white blood cell count in most patients was in the hundreds or thousands, with either lymphocytic or neutrophilic predominance.11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17

Table.

Summary of 10 Previously Published Cases of Aseptic Meningitis in a Setting of Pituitary Apoplexy

| Case number | Demographics | Symptoms | CSF WBC count (/mm3) | CSF findings | Diagnostic imaging | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 42-year-old M | Headache and vomiting | 260 | Neutrophilic pleocytosis | MRI | 11 |

| 2 | 59-year-old M | Headache, neck stiffness, and nausea | 4375 | Neutrophilic pleocytosis | Imaging was nondiagnostic | 12 |

| 3 | 53-year-old M | Acute headache, fever, neck stiffness, and paresis of the left oculomotor and abducens nerves | Data unavailable | Neutrophilic pleocytosis | MRI | 13 |

| 4 | 50-year-old M | Headache, vomiting, diplopia, and right eyelid droop | 52 | Lymphocytic pleocytosis | CT was nondiagnostic, MRI was not performed | 14 |

| 5 | 45-year-old M | Headache, vomiting, confusion, visual impairment, and bilateral nerve VI palsies | 900 | Neutrophilic pleocytosis | CT was nondiagnostic, MRI was not performed | 14 |

| 6 | 45-year-old M | Headache and sudden onset of confusion | 174 | Neutrophilic pleocytosis | MRI | 15 |

| 7 | 61-year-old M | Headache, nausea, vomiting, and flu-like symptoms. Three days after admission: left-sided ptosis and left nerve VI palsy | 156 | Lymphocytic pleocytosis | MRI | 16 |

| 8 | 32-year-old F | Headache, fever, photophobia, dysarthria, and diplopia | 500 | Neutrophilic pleocytosis | CT | 17 |

| 9 | 51-year-old F | Headache, fever, nausea, and vomiting | 70 | Neutrophilic pleocytosis | MRI | 17 |

| 10 | 46-year-old F | Left-sided headache, nausea, vomiting, and dysarthria | 110 | Neutrophilic pleocytosis | CT | 17 |

Abbreviations: CSF = cerebrospinal fluid; CT = computed tomography; F = female; M = male; MRI = magnetic resonance imaging; WBC = white blood cell.

The treatment of PA remains controversial. A surgical approach is preferred in patients with changes to the level of consciousness, rapid deterioration, severe visual loss, or optic chiasm compression.18 If timely diagnosed and appropriately treated, the outcome for most patients with PA is excellent.8

Conclusion

This case reinforces the importance of including PA in the differential diagnosis of acute headache, particularly in patients presenting with visual disturbances. Patients with PA can present with sterile meningitis due to increased debris and blood in the subarachnoid space, which closely mimics acute bacterial meningitis. Acute sterile meningitis is an uncommon manifestation of PA and has rarely been described in the literature. While MRI is a sensitive imaging modality for the detection of PA, diagnosis of PA remains clinical. Timely diagnosis with high clinical suspicion and treatment is essential.

Disclosure

The authors have no multiplicity of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Huang W.Y., Chien Y.Y., Wu C.L., Weng W.C., Peng T.I., Chen H.C. Pituitary adenoma apoplexy with initial presentation mimicking bacterial meningoencephalitis: a case report. Am J Emerg Med. 2009;27(4) doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2008.08.004. 517.e1-517.E4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sadek A.R., Gregory S., Jaiganesh T. Pituitary apoplexy can mimic acute meningoencephalitis or subarachnoid haemorrhage. Int J Emerg Med. 2011;4(1):63. doi: 10.1186/1865-1380-4-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abbara A., Clarke S., Eng P.C. Clinical and biochemical characteristics of patients presenting with pituitary apoplexy. Endocr Connect. 2018;7(10):1058–1066. doi: 10.1530/EC-18-0255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Randeva H.S., Schoebel J., Byrne J., Esiri M., Adams C.B., Wass J.A. Classical pituitary apoplexy: clinical features, management and outcome. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1999;51(2):181–188. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.1999.00754.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Biousse V., Newman N.J., Oyesiku N.M. Precipitating factors in pituitary apoplexy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2001;71(4):542–545. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.71.4.542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Semple P.L., Jane J.A., Jr., Laws E.R., Jr. Clinical relevance of precipitating factors in pituitary apoplexy. Neurosurgery. 2007;61(5):956–961. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000303191.57178.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Briet C., Salenave S., Bonneville J.-F., Laws E.R., Chanson P. Pituitary apoplexy. Endocr Rev. 2015;36(6):622–645. doi: 10.1210/er.2015-1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singh T.D., Valizadeh N., Meyer F.B., Atkinson J.L.D., Erickson D., Rabinstein A.A. Management and outcomes of pituitary apoplexy. J Neurosurg. 2015;122(6):1450–1457. doi: 10.3171/2014.10.JNS141204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boellis A., di Napoli A., Romano A., Bozzao A. Pituitary apoplexy: an update on clinical and imaging features. Insights Imaging. 2014;5(6):753–762. doi: 10.1007/s13244-014-0362-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nawar R.N., AbdelMannan D., Selman W.R., Arafah B.M. Pituitary tumor apoplexy: a review. J Intensive Care Med. 2008;23(2):75–90. doi: 10.1177/0885066607312992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oh K., Kim J.H., Choi J.W., Kang J.K., Kim S.H. Pituitary apoplexy mimicking meningitis. Brain Tumor Res Treat. 2013;1(2):111–115. doi: 10.14791/btrt.2013.1.2.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Myla M., Lewis J., Beach A., Sylejmani G., Burge M.R. A perplexing case of pituitary apoplexy masquerading as recurrent meningitis. J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep. 2018;6:1–5. doi: 10.1177/2324709618811370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Valente M., Marroni M., Stagni G., Floridi P., Perriello G., Santeusanio F. Acute sterile meningitis as a primary manifestation of pituitary apoplexy. J Endocrinol Invest. 2003;26(8):754–757. doi: 10.1007/BF03347359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Winer J.B., Plant G. Stuttering pituitary apoplexy resembling meningitis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1990;53(5):440. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.53.5.440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sadek A.R., Gregory S., Jaiganesh T. Pituitary apoplexy can mimic acute meningoencephalitis or subarachnoid hemorrhage. Int J Emerg Med. 2011;4(1):63. doi: 10.1186/1865-1380-4-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ma R.C.W., Tsang M.W., Ozaki R., Tong P.C., Cockram C.S. Fever, headache, and a stiff neck. Lancet. 2004;363(9424):1868. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16355-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jassal D.S., McGinn G., Embil J.M. Pituitary apoplexy masquerading as meningoencephalitis. Headache. 2004;44(1):75–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2004.04013.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Albani A., Ferraù F., Angileri F.F. Multidisciplinary management of pituitary apoplexy. Int J Endocrinol. 2016;2016:7951536. doi: 10.1155/2016/7951536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]