Abstract

A recent surge in the use and abuse of diverse prescribed psychotic and illicit drugs necessitates the surveillance of drug residues in source water and the associated ecological impacts of chronic exposure to the aquatic organism. Thirty-six psychotic and illicit drug residues were determined in discharged wastewater from two centralized municipal wastewater treatment facilities and two wastewater receiving creeks for seven consecutive days in Kentucky. Zebrafish (Danio rerio) larvae were exposed to the environmental relevant mixtures of all drug residues, all illicit drugs, and all prescribed psychotic drugs. The extracted RNA from fish homogenates was sequenced, and differentially expressed sequences were analyzed for known or predicted nervous system expression, and screened annotated protein-coding genes to the true environmental cocktail mixture. Illicit stimulant (cocaine and one metabolite), opioids (methadone, methadone metabolite, and oxycodone), hallucinogen (MDA), benzodiazepine (oxazepam and temazepam), carbamazepine, and all target selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors including sertraline, fluoxetine, venlafaxine, and citalopram were quantified in 100% of collected samples from both creeks. The high dose cocktail mixture exposure group revealed the largest group of differentially expressed genes: 100 upregulated and 77 downregulated (p ≤ 0.05; q ≤ 0.05). The top 20 differentially expressed sequences in each exposure group comprise 82 unique transcripts corresponding to 74% annotated genes, 7% non-coding sequences, and 19% uncharacterized sequences. Among 61 differentially expressed sequences that corresponded to annotated protein-coding genes, 23 (38%) genes or their homologs are known to be expressed in the nervous system of fish or other organisms. Several of the differentially expressed sequences are associated primarily with the immune system, including several major histocompatibility complex class I and interferon-induced proteins. Interleukin-1 beta (downregulated in this study) abnormalities are considered a risk factor for psychosis. This is the first study to assess the contributions of multiple classes of psychotic and illicit drugs in combination with developmental gene expression.

Keywords: Illicit Drugs, Psychotic Drugs, Zebrafish, Nervous System, Next Generation Gene Sequencing, RNA-Seq

Graphical Abstract

CAPSULE:

Thirty-six psychotic and illicit drug residues determined in surface water and zebrafish exposure to mixtures of those drugs expressed genes that correspond to the CNS and immune system.

1. Introduction

Psychotropic medications are among the most commonly prescribed drugs in the U.S., and 62% of the top 50 prescribed medications target the central nervous system (Fuentes et al., 2018). Typically, the psychotic, bipolar, schizophrenic, and depressive disorders are treated using a polypharmacy combination of psychotic drugs (Bareis et al., 2018). In addition to a high volume per capita consumption, psychotics and opioids are the most commonly abused classes of the prescribed medications (SAMHSA, 2019). The significant portion of administered benzodiazepines (74.5% of temazepam), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI: 26% of citalopram), opioids (63.8% of codeine), and illicit drugs (36.3% of methamphetamine) is excreted through urine and feces (Baker et al., 2014; Croft et al., 2020).

The consumed (or directly disposed) drugs are discharged down the drain in the form of parent unchanged or metabolites and reach to the wastewater treatment plant (WWTP) or septic systems (Daughton, 1999). The existing wastewater treatment processes and engineering were not designed to remove drug residues; therefore, a significant portion of a mass influx of psychotic and illicit drug residues to the WWTPs end up continuously discharged into the receiving water bodies (Subedi and Kannan, 2014; Subedi and Kannan, 2015). The mass discharge of diverse psychotropic and illicit drugs including methamphetamine (111 mg/d/1000 people), venlafaxine (111 mg/d/1000 people), and EDDP (a metabolite of methadone: 67.5 mg/d/1000 people) were reported from the WWTPs in New York and Kentucky (Subedi and Kannan, 2014; Skees et al., 2018). Continual discharge of drug residues into the source water causes them to behave as pseudo-persistent in the aquatic ecosystem. The amphetamine and methamphetamine were reported as much as 630 ng/L (Lee et al., 2016) and 1994 ng/L (Watanabe et al., 2020) in wastewater impacted Gwynns Falls in Baltimore (MD) and the Foster Creek in Santee (CA), respectively.

Zebrafish (Danio rerio) is an important model organism to study complex human neurological disorders due to the physiological and genetic homology to humans, ease of genetic manipulation, robust behavior, and cost-effectiveness (Neelkantan et al., 2013; Bosse and Paterson, 2017). The behavioral alterations on aquatic organisms due to exposure of individual illicit and psychotic drugs, such as cocaine, MDMA, amphetamine, diazepam, are reported. Acute exposure of MDMA at 10–120 mg/L showed significantly altered behaviors of zebrafish adults including bottom swimming, immobility, and impaired intra-session habituation as well as elevated brain c-fos expression (Stewart et al., 2011). Exposure of cocaine to the freshwater invertebrate Daphnia magna at 50 and 500 ng/L affected the swimming behavior and induced the overproduction of reactive oxygen species (Felice et al., 2019). Similarly, amphetamine-treated artificial streams exhibit several ecological impacts including decreased biofilm chlorophyll a (45%) and biofilm gross production (85%) as well as elevated seston (24%) and cumulative dipteran emergence (up to 89%) (Lee et al., 2016). Even though the risk assessment of a mixture of drugs instead of an individual drug in the aquatic environment was suggested (Cerveny et al., 2020), there are very few reports on the ecological effects of exposure to a real-world mixture of diverse classes of psychoactive drugs.

The exposure of a mixture of cocaine and its two metabolites (benzoylecgonine and ecgonine methyl) at environmentally relevant levels (~1.0 ug/L) reduced cell viability, increased DNA fragmentation, and altered protein profiles (Parolini et al., 2017; Parolini et al., 2018) in zebrafish embryos and significantly increased lipid peroxidation and DNA damage in the freshwater mussel Dreissena polymorpha (Parolini et al., 2013). The exposure of a mixture of acetaminophen, CBZ, gemfibrozil, and venlafaxine to zebrafish for 6 weeks significantly increased the incidence of developmental abnormalities of embryos including spinal cord deformations, pericardial edema, yolk sac edema, and stunted growth (Galus et al., 2013). Zygotic zebrafish exposure to venlafaxine resulted in a higher spatial expression of nrd4, a marker of neurogenesis, and disrupted early brain development as evidence by increased neurogenesis in the hypothalamus, dorsal tuberculum, and preoptic region (Thompson et al., 2017).

The pharmaceutical residues in surface water eventually reach to the drinking water that can cross maternal biological barriers and alter the embryonic nervous system (Kaushik and Thomas, 2019). Mixtures of fluoxetine, venlafaxine, and carbamazepine altered the expression of human neurological genes associated with idiopathic autism, Alzheimer’s disease, and schizophrenia in vitro (Kaushik and Thomas, 2019; Kaushik et al., 2016).

In this study, the level of 9 illicit drugs, 20 prescribed psychotic drugs, and 7 select metabolite residues was determined in discharged wastewater effluents and immediately receiving creeks in eastern Kentucky. Zebrafish larvae were exposed to a mixture of all drug residues, all illicit drugs, and all prescribed psychotic drugs at the determined level in creeks. Larvae were also exposed to a mixture of all drugs at the reported highest level elsewhere. The RNA was extracted from fish homogenates for next-generation sequencing, differentially expressed transcripts were analyzed for known or predicted nervous system expression or function, and annotated protein-coding genes screened to the true environmental cocktail mixture. This is the first study to report the developmental gene expression resulting from the exposure to environmental cocktail mixtures of illicit stimulants, hallucinogens, opioids/narcotics as well as prescribed anxiolytics and antidepressants.

2. Materials and method

2.1. Reagents and chemicals

The most frequently reported illicit and prescribed antipsychotic drugs in treated wastewater and the receiving water bodies were targeted. The vendor and purity of all reagents and chemicals including target drugs, metabolites, and corresponding isotope-labeled internal standards are provided elsewhere (Skees et al., 2018).

2.2. Sample collection and preparation

Twenty-four-hour composite samples of treated wastewater (one aliquot every fifteen min) from two WWTPs in eastern Kentucky were collected using a time-proportional autosampler and maintained at 4°C during the collection period. Sampling was performed for seven consecutive days during a typical week in the late summer of 2018. WWTP-A treats an average of 27.2 million gallons per day (MGD) of sewage from industrial and metropolitan areas serving ~190,000 people whereas the WWTP-B treats an average of 21 MGD of sewage from more suburban areas serving ~160,000 people. A creek that receives the treated wastewater effluent discharged from WWTP-A was sampled ~ ½ km downstream while a creek that receives the discharged effluent from WWTP-B was sampled ~1 km downstream. All collected samples were transported on ice to the laboratory and extracted within six hours of collection.

The detailed sample preparation procedures are described elsewhere (Skees et al., 2018; Croft et al., 2020). Briefly, the collected 100 mL of wastewater or 200 mL of surface water samples were allowed to equilibrate to room temperature, thoroughly mixed, centrifuged at 4500 rpm for 5 min, and vacuum filtrated using 1.0 μm glass fiber filter paper to separate suspended particulate matter (SPM). Filtered samples were spiked with internal standards mixture, extracted using Oasis® hydrophilic-lipophilic balance (HLB) solid-phase extraction (SPE) cartridges, and eluted with 4 mL of methanol followed by the 3 mL of 5% ammonia in methanol. The extracts were transferred quantitatively to the amber silanized HPLC vials and the final volume adjusted to 1 mL with methanol. SPM was freeze-dried for 6 h, allowed to reach room temperature, spiked with the internal standard mixture, vortexed with 6 mL of methanol, and ultra-sonicated for 30 min. SPM samples were then centrifuged, the supernatant liquid was collected, re-extracted and the extracts were combined. All extracts were concentrated to 250 μL under a gentle stream of nitrogen, quantitatively transferred to amber silanized HPLC vials, adjusted the final volume to 1 mL with methanol, and analyzed for target residues using ultra-performance liquid chromatograph (UPLC) tandem mass spectrometer (MS/MS) as detailed elsewhere (Skees et al., 2018; Croft et al., 2020). The isotopic dilution mass spectrometry method was applied where a known quantity of deuterated isotopes of each target analyte (internal standard) is spiked directly into the sample before sample preparation and analytes are quantified based on the relative response factors of isotopic-labeled internal standard and the corresponding analyte. The five-to-ten-point calibration curves of each target analyte were prepared by plotting the concentration-dependent response factor against the response-dependent concentration factor. The linear or quadratic regression coefficients determined using Agilent MassHunter Workstation for the Quantitative Analysis were r2 ≥0.99 for all analytes. The details of quality assurance and quality control are provided in supporting information.

2.3. Estimation of drug discharge rate

The level of drugs in wastewater and surface water was expressed as the mean (n=7) concentration (ng/L) among seven consecutive days to minimize the potential weekend effect (Table 1). The level of drugs that were detected <LOQ was replaced by LOQ when drugs were quantified in ≥70% of samples. The rate of drug discharge to the receiving creek was determined using equation 1 similar as described elsewhere (Skees et al., 2018).

| (1) |

where rate of drug discharge is the daily amount (mg/d/1000 people) of individual drug discharged through wastewater effluent to the creek, C is the total nanograms of analytes in 1 L of wastewater effluent and SPM combined (ng/L), F is the daily flow rate of wastewater (L/d) over a 24 h period, stability is a measure of stability change (%) of analyte in wastewater up to 12 h (Croft et al., 2020), and the population is the number of people served by WWTPs based on the daily ammoniacal nitrogen load (Croft et al., 2020).

Table 1.

Average rate of drug discharge through the wastewater effluent and average level of drug residues in the receiving creek. The values in parenthesis represent the detection frequency of drugs through seven consecutive days.

| Analytes* | **Discharge Rate (mg/d/1000 people) ± 95% Confidence Interval | Concentration (ng/L) ± Standard Error | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WWTP-A | WWTP-B | Creek-A | Creek-B | Literature | |

| Stimulants | |||||

| Cocaine | 9.01 ± 6.27 | 10.6 ± 17.7 | 11.5 ± 2.37 (100%) | 14.9 ± 5.45 (100%) | 5.26a; 8–53e; 2.50–3.40f; |

| Benzoylecgonine | 23.0 ± 12.6 | 23.8 ± 13.5 | 23.4 ± 3.67 (43%) | 18.6 ± 0.76 (29%) | 9.48a; 8–60e; 2.40–14.2f; |

| Norcocaine | 7.19 ± 2.37 | 2.97 ± 2.55 | 11.3 ± 0.80 (100%) | 10.6 ± 0.89 (100%) | 3.70–4.40f; |

| Cocaethylene | nd | nd | 2.05 (14%) | 2.55 ± 0.44 (43%) | |

| Methamphetamine | 18.1 ± 7.49 | 11.8 ± 10.5 | 18.4 ± 5.35 (57%) | 15.2 ± 2.36 (29%) | 1.3–62.6b; 7c; 24–1994e; 2.70–86.4f; |

| Amphetamine | 3.44 ± 1.44 | 3.91 ± 1.84 | 3.06 ± 1.31 (29%) | 2.32 ± 0.20 (29%) | 3–630c; 9–101e; 2.50–5.10f; |

| Methylphenidate | 3.59 ± 1.15 | 3.10 ± 1.23 | 2.92 (14%) | 3.41 (14%) | 2.70–3.90f; |

| Opioids/Narcotics | |||||

| Heroin | 1263 ± 1180 | 692 ± 1050 | 262 ± 84.3 (100%) | 434 ± 143 (86%) | |

| 6-acetyl Morphine | 2.18 | 1.86 | nd | nd | |

| Morphine | 5.05 ± 3.22 | 10.3 ± 74.0 | 10.7 ± 3.79 (43%) | 14.1 ± 4. 95 (43%) | 16–83c; 6.2f; |

| Methadone | 17.2 ± 3.74 | 9.67 ± 5.07 | 19.2 ± 1.83 (100%) | 8.31 ± 2.03 (100%) | 2.4–17.8f; |

| EDDP | 59.4 ± 13.8 | 44.6 ± 20.6 | 71.7 ± 5.27 (100%) | 42.3 ± 3.80 (100%) | |

| Codeine | 12.7 ± 2.97 | 10.5 ± 5.64 | 13.1 ± 2.27 (100%) | 15.1 ± 2.99 (57%) | 4.20–34.4f; |

| Fentanyl | 3.60 ± 1.63 | 2.47 | 4.93 ± 0.87 (71%) | 3.90 ± 0.92 (29%) | 1.40–1.50f; |

| Oxycodone | 43.3 ± 9.01 | 22.8 ± 11.8 | 51.1 ± 4.41 (100%) | 24.9 ± 6.31 (100%) | 2.90–27.0f; |

| Hydrocodone | 21.4 ± 3.65 | 9.59 ± 5.06 | 21.9 ± 3.73 (100%) | 11.2 ± 0.97 (43%) | 5.00–126f; |

| Hydromorphone | 1.77 ± 1.20 | 3.22 | 4.67 ± 1.00 (57%) | 3.34 ± 0.15 (43%) | 9.10f; |

| Buprenorphine | nd | 3.40 | 5.88 (14%) | nd | |

| Hallucinogens | |||||

| MDMA | nd | nd | nd | nd | 6.1f; |

| MDEA | nd | nd | nd | nd | |

| MDA | 11.5 ± 4.12 | 8.95 ± 4.80 | 8.22 ± 0.76 (100%) | 8.86 ± 0.77 (100%) | |

| THC | nd | nd | nd | nd | |

| THC-OH | nd | nd | nd | nd | 51.6–339f; |

| THC-COOH | nd | nd | nd | nd | |

| Antischizophrenics | |||||

| Quetiapine | nd | nd | 4.18 (14%) | nd | 4.4f; |

| Aripiprazole | 3.52 | nd | 0.91 ± 0.30 (86%) | 0.79 ± 0.14 (100%) | 5.1–8.3f; |

| Anxiolytics | |||||

| Lorazepam | 6.25 ± 0.87 | 6.71 ± 2.79 | 4.99 ± 0.88 (100%) | 6.06 ± 0.87 (57%) | 15.8f; |

| Alprazolam | 2.44 ± 1.45 | 575 ± 117 | 3.29 (14%) | nd | 0.37a; 2.40–6.10f; |

| Diazepam | 3.51 ± 4.54 | 1.15 ± 8.42 | 3.25 ± 0.01 (29%) | 3.16 ± 0.22 (57%) | 2.60–6.10f; |

| Oxazepam | 5.34 ± 1.28 | 4.36 ± 3.72 | 8.97 ± 1.35 (100%) | 5.66 ± 1.38 (100%) | 22.5–34.5f; |

| Temazepam | 19.6 ± 5.90 | 30.1 ± 13.0 | 46.7 ± 6.51 (100%) | 41.9 ± 5.83 (100%) | 3.40–60.9f; |

| Carbamazepine | 92.6 ± 20.0 | 89.7 ± 43.7 | 168 ± 13.9 (100%) | 129 ± 14.3 (100%) | 36.7a; 3.1–296b;6–38c; 3.80–63.1f; |

| Antidepressants | |||||

| Sertraline | 34.8 ± 11.6 | 25.7 ± 13.9 | 53.9 ± 6.20 (100%) | 29.9 ± 4.50 (100%) | 0.7–37.5d; 3.80.-24.2f; |

| Fluoxetine | 19.5 ± 5.98 | 25.9 ± 11.8 | 26.8 ± 1.75 (100%) | 25.8 ± 1.87 (100%) | 4.52a; 0.5–43.2d; 3.50–9.60f; |

| Venlafaxine | 222 ± 44.3 | 155 ± 89.7 | 364± 36.8 (100%) | 212± 62.05 (100%) | 73.3–690d; 2.60–243f; |

| Citalopram | 116 ± 22.2 | 55.4 ± 43.9 | 170± 20.3 (100%) | 78.7 ± 29.34 (100%) | 4.53–219d; 2.70–3.90f; |

metabolites are italicized; nd: not detected

estimated population of community A and B were 189,335 and 157,796, respectively, based on quantified ammoniacal nitrogen load to the WWTPs (Croft et al., 2020)

Fifty Minnesota Lakes in Minnesota (Ferrey et al., 2015)

Wastewater impacted surface water in Omaha, NE (Bartelt-Hunt et al., 2009)

Gwynns Falls and Oregon Ridge watershed in Baltimore, MD (Lee et al., 2016)

Boulder Creek, CO and Fourmile Creek, IA (Schultz et al., 2010)

Forester Creek, Santee, CA (Watanabe et al., 2020)

Bee Creek and Clarks River, Murray, KY (Skees et al., 2018)

2.4. Animal husbandry

Zebrafish husbandry and experimental procedures were approved by the Murray State Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Adult zebrafish (Danio rerio) were housed in a recirculating rack system (Aquaneering, San Diego, CA) with a 14:10 light:dark cycle. Water quality was continuously monitored using Neptune APEX (Morgan Hill, CA). The pH ranged between 7.5 and 8 and water temperatures were kept at 27.5 °C ± 1. The zebrafish were fed twice daily with adult zebrafish diet (Ziegler, East Berlin, PA). Eggs were generated by natural spawning. Larvae were raised in 30% Danieau until 72 h post-fertilization (hpf). Hatched zebrafish larvae were maintained at 28.5°C in static tanks of 0.5 L 30% Danieau (17.4 mM NaCl, 0.21 mM KCl, 0.12 mM MgSO4, 0.18 mM Ca(NO3)2, 1.5 mM HEPES buffer; pH 7.6) with 100% water changes every two days for 14 days. Larvae were fed twice daily with the Golden Pearl powdered larval diet.

2.5. Drug exposure to Zebrafish

Groups of 45 larvae per tank from mixed clutches were exposed to one of three separate sets of drug mixtures [prescribed psychotic drugs (PPD), illicit drugs (ILD), and the cocktail of all prescribed and illicit drugs (PID) at the average concentrations measured in creek A and B. The drug mixtures at the average concentrations measured in creek A and B (Table 1) are represented hereafter as low dose (LD) cocktail mixtures. As a representation of worst-case environmental exposure of neuropsychiatric and illicit drugs, another set of larvae was exposed to a cocktail mixture of all target drugs at the highest concentrations reported in wastewater, represented hereafter as high dose (HD) cocktail mixture (Table S1). An additional set of larvae was considered a vehicle control. The drug mixtures contained acetonitrile and methanol as a vehicle. The amount of each to be added to the exposure tanks was calculated based on the drug mixtures, such that all tanks received the same concentrations of methanol and acetonitrile, regardless of drug mixture. The control groups were dosed with 10 μL acetonitrile and 140 μL methanol in 500 mL 30% Danieau for a final concentration of 20 pL/mL acetonitrile and 280 pL/mL methanol. The experiment was repeated four times with staggered start dates. Larvae were counted during water changes and deceased larvae were removed. Survival analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism 7.

2.6. RNA extraction and gene expression analysis

After 14 days of drug exposure, larvae were pooled from each tank for total RNA extraction using TRIzol™ reagent according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Larvae were anesthetized on ice and homogenized in TRIzol™ using sterile pestles and by drawing up and down through a 28 G × ½” syringe needle. Homogenized samples were purified using chloroform, precipitated for 10 min at room temperature with glycogen (0.04 μg/μL) and isopropanol, rinsed with chilled 75% ethanol, resuspended in nuclease-free water, and stored at −80°C. Sample concentrations and purity were measured on a NanoDrop Lite Spectrophotometer (ThermoFisher).

Libraries were prepared using the TruSeq Stranded mRNA Library Prep kit (Illumina), TruSeq RNA Single Indexes Set A (Illumina), and Set B (Illumina). Poly-A enrichment and RNA fragmentation were performed by treating 100 ng of samples with RNA purification beads, denatured for 5 min at 65°C, washed, and captured polyadenylated RNA at 80°C for 2 min. The mRNA is further purified in a second bead clean-up, fragmented and primed during elution, and incubating for 8 min at 94°C. After fragmentation, 17 μL of supernatant was removed from the beads and proceeded immediately to synthesize the first-strand cDNA. First Strand cDNA was synthesized mixing 8 μL of First-Strand Synthesis Mix Act D and SuperScript II mix to each sample and heated on a thermocycler. The second strand cDNA was synthesized using Second Strand Marking Mix, incubated at 16°C for 1 h, purified using Agencourt AMPure XP Beads, and eluted using resuspension buffer. A-Tailing Mix was added to the purified samples for Adenylate 3’ Ends. Samples were ligated using Ligation Mix, incubated for 30°C for 10 min, purified two times using Agencourt AMPure XP Beads, and 20 μL of the elute was collected for DNA enrichment. DNA fragments were enriched using PCR Primer Cocktail Mix and PCR Master Mix, purified using Agencourt AMPure XP Beads, and 20 μL of eluted libraries were collected and stored at −20°C. The libraries were quantitated using Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit (Invitrogen Q32851), diluted, and normalized to the optimal range for Agilent Bioanalyzer analysis using the DNA High Sensitivity Kit (Agilent Technologies). The same molar amounts of libraries were pooled based on the molar concentration from Bioanalyzer. The qualitative and quantitative analyses of pooled libraries were performed on MiSeq using MiSeq Reagent Nano Kit V2 300 cycles (Illumina). Library and PhIX control (Illumina) were denatured and diluted using the manufacturer’s standard normalization procedure to the final concentration of 6 pM. An aliquot of the library (300 μL) and PhIX (300 μL) were combined and sequenced on Illumina MiSeq. Based on MiSeq results, an equal amount of libraries was re-pooled prior to the replicate (n=2) NextSeq analysis using Illumina NextSeq 500 (NextSeq 500/550 75 cycle High Output Kit v2) at the University of Louisville Genomics Facility.

The quality of each raw sequence data using FastQC (version 0.10.1) demonstrated the quality of data and no sequence trimming was required. Therefore, the concentrated sequences were directly aligned to the Danio rerio (Zebrafish) reference genome assembly (GRCz11.fa) using STAR (version 2.6) (Dobin et al., 2013), the alignment rate ranged from 96.5 to 98.0%. The differential expression was performed using DESeq2 (Love et al., 2014) and Cuffdiff2 (Trapnell et al., 2012).

Differentially expressed genes at p ≤ 0.05; q ≤ 0.01 and ∣log2FC∣ ≥ 0 were used for further analysis of enriched Gene Ontology Biological Processes (GO:BP) and KEGG Pathways using category Compare. The Entrez gene ID for each differentially expressed gene was obtained from the zebrafish Entrez IDs database from NCBI.

The top twenty differentially expressed sequences in each exposure condition were analyzed for known or predicted nervous system expression or function. First, zebrafish sequences that did not have descriptive gene name (ex. si:ch211–157j23.2) were compared to related sequences by translated nucleotide to protein BLAST (blastx) on both NCBI (Johnson et al., 2008) and Ensembl Genome Browser GRCz11 databases (Yates et al., 2020). Sequences were sorted into annotated protein-coding genes, non-coding sequences, and uncharacterized transcripts.

Next, annotated protein-coding genes identified were screened for nervous system expression and/or function. Gene identities were searched on GeneCards.org, with expression analysis containing expression information compiled from RNAseq, microarray, SAGE, and protein expression of human genes (Stelzer et al., 2016). Expression at or above the 10 thresholds in two or more of the datasets (RNAseq, microarray, or SAGE) or ≥ 1 ppm protein was considered “verified” nervous system expression. Literature searches for nervous system expression or function supplemented the expression datasets. ZFIN.org gene expression databases (RNAseq, microarray, in situ hybridization) were also searched for zebrafish nervous system expression. Several sequences were identified with low resolution – ex. expression in the embryonic head region. Such sequences were classified as nervous system expression “predicted.”

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Rate of drug discharge from WWTPs

The majority of the target drugs were discharged to the creek at a weekly average level of 4.67 ng/L (hydromorphone) to 858 ng/L (Heroin) from WWTP-A and 2.79 ng/L (diazepam) to 402 ng/L (Heroin) from WWTP-B through the treated wastewater (Table S1). Two stimulants (methamphetamine and methylphenidate), two opioids (methadone/EDDP and oxycodone), one hallucinogen (MDA), four sedatives (alprazolam, oxazepam, temazepam, and carbamazepine), and all four major antidepressants (venlafaxine, sertraline, fluoxetine, and citalopram) were found in all wastewater samples (detection frequency, df=100%) in both WWTPs.

Our previous study reported 387 g daily mass load of cocaine (sum of cocaine and its two major metabolites in wastewater influent) to WWTP-A and 1030 g to WWTP-B (Croft et al., 2020). In this study, the total daily discharge mass of cocaine from WWTP-A and WWTP-B was 7.15 g and 6.64 g, respectively (Table 1). Based on the level of drug residues quantified in simultaneously collected wastewater influents (Croft et al., 2020) and effluents (this study), the removal efficiencies of cocaine were 98 and 99%, respectively, in WWTP-A and WWTP-B.

The estimated levels of community prevalence of methamphetamine and amphetamine in western Kentucky were highest among the global communities (SCORE, 2019), however, the methamphetamine prevalence in two urban communities in Eastern Kentucky was significantly lower than in rural western Kentucky (Croft et al., 2020). Nonetheless, the average daily mass discharge of methamphetamine and amphetamine from the target WWTPs was ~2500 g and ~675 g, respectively (Table 1). Heroin was predominantly discharged from both WWTPs among opioids followed by methadone, oxycodone, and hydrocodone. Alprazolam is the third most prescribed controlled substance only after hydrocodone and oxycodone in Kentucky (KIPRC, 2019; KASPER, 2020). However, alprazolam was significantly removed (~77%) during the wastewater treatment and lowers the mass discharge of alprazolam from WWTPs compared to temazepam by ~10 folds even though their mass loads to the WWTPs were similar (Croft et al., 2020). Carbamazepine was very stringent on removal through wastewater treatment (Subedi and Kannan, 2015) and discharged at ~16.5 g/d in this study. Venlafaxine, sertraline, fluoxetine, and citalopram are among the top 50 most prescribed drugs in the U.S., and the latter three are the top three prescribed selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) in the U.S. (Fuentes et al., 2018). Antidepressants were found to discharge from WWTPs at ~4.0 g/d (fluoxetine) to ~42.0 g/d (venlafaxine) (Table 1).

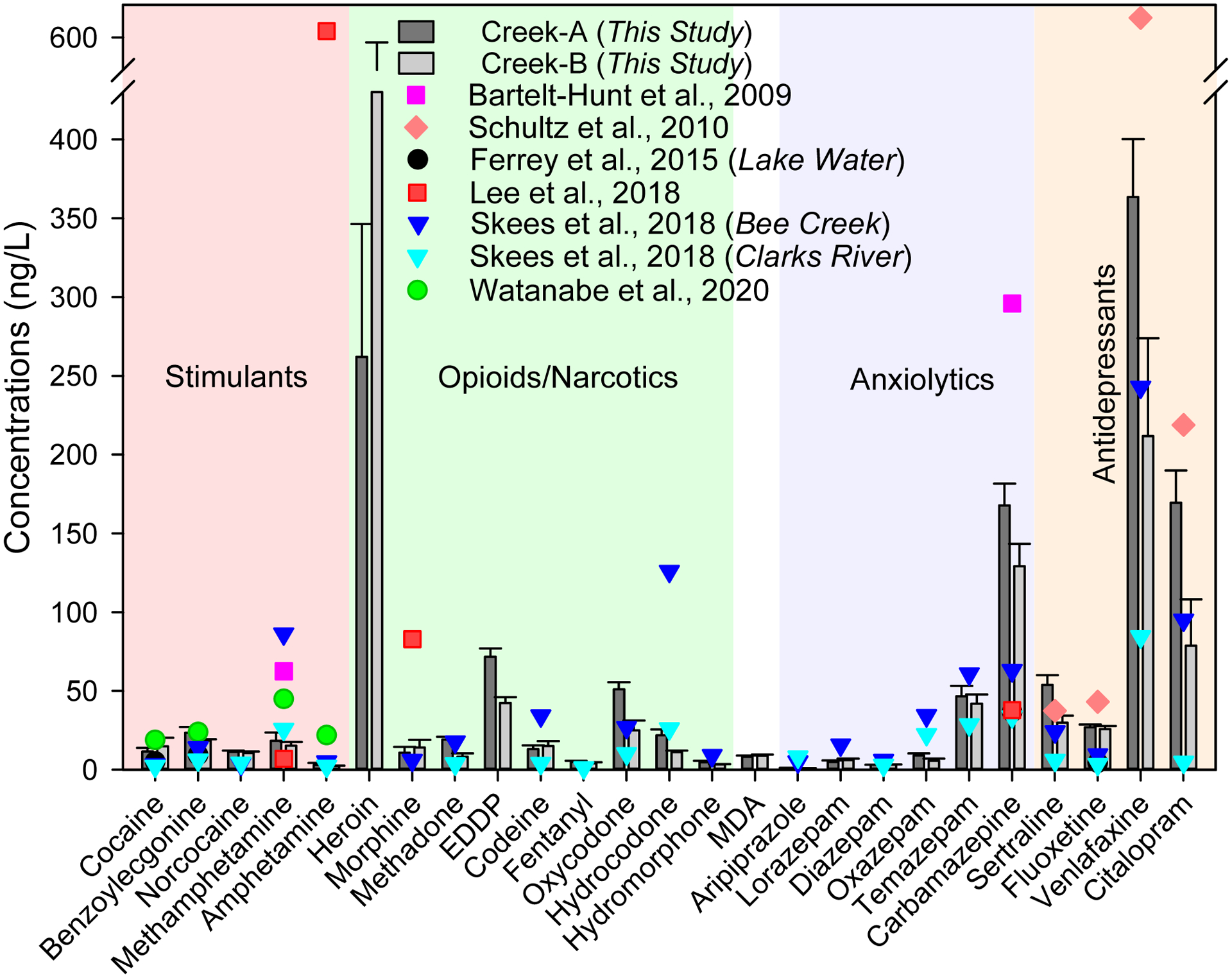

3.2. Drugs in treated wastewater receiving creeks

The level of drugs in immediate creeks that receive treated wastewater from WWTPs ranged from 2.02 ng/L (cocaethylene, a metabolite of cocaine) to 434 ng/L (Heroin) (Figure 1, Table 1). Overall, a creek that runs through the urban area and receives treated wastewater from a WWTP that treats wastewater from urban areas (WWTP-A) had higher levels of residual drugs. Cocaine (and its one metabolite), methadone (and its metabolite), oxycodone, MDA, oxazepam, temazepam, carbamazepine, and all antidepressants (sertraline, fluoxetine, venlafaxine, and citalopram) were quantified in all samples from both creeks.

Figure 1.

Concentration of illicit and prescribed antipsychotic drug residues in two treated wastewater receiving creeks in Eastern Kentucky (this study) and surface water elsewhere in the U.S.

The ratio of cocaine and its primary metabolite, benzoylecgonine, is typically within a range of 0.27–0.75 based on their human excretion rates and the molar masses (Bijlsma et al., 2012). In this study, the ratio of cocaine and benzoylecgonine (cocaine metabolite) concentrations in creek B (1.55 and 2.18) was higher than in creek A (0.50–0.90), wastewater influents (0.32–0.55), and wastewater effluents (0.28–0.61), suggesting the direct disposal of cocaine in creek B. The use of methamphetamine was significantly higher in rural communities in western Kentucky than urban communities in eastern Kentucky (Croft et al., 2020), and the level of methamphetamine in creek-A (this study) was ~5 folds lower than that reported in Bee Creek in western Kentucky (Skees et al., 2018).

There are growing concerns over the upsurge opioid discharges into the source water resulted from the recent elevated opioid consumption in the U.S. Morphine (83 ng/L Lee et al., 2016 in Gwynns Run in Baltimore, Maryland, hydrocodone (126 ng/L Skees et al., 2018) in Bee Creek in western Kentucky, and 71.7 ng/L of EDDP (a metabolite of methadone, this study) suggest the prevalence of opioids in treated wastewater receiving water bodies in the U.S.

Very few reports are available on the occurrence of illicit and prescribed antipsychotic drugs of potential abuse and addiction in surface water in the U.S. The majority of drug residues are reported <50 ng/L; however, carbamazepine and select antidepressants such as venlafaxine and citalopram are typically reported ~100 ng/L owing partially to higher production and consumption as well as stringency on removal through conventional wastewater treatment. Despite low ng/L to low μg/L level of drug residues in an aquatic ecosystem, chronic exposure of the aquatic organism to the cocktail environmental mixture of illicit and antipsychotic drug residues can lead to additive or non-additive effects or neutralize each other’s effects (Brodin et al., 2014).

3.3. Differentially expressed genes

Larval survival between exposure groups and between exposure replicates was similar. Average 14 dpf survival was 58% (Figure S1) and survival between groups was similar (F (4, 15) = 1.546; p > 0.05). A Principal Component Analysis performed on the gene sequences obtained from the zebrafish exposure conditions did not find a clear separation between the five experimental groups (Figure S2). Adverse effects on gene expression would likely be even more pronounced and with more variation, if fish were exposed as newly fertilized eggs, as the chorions limit the movement of some compounds (Pelka et al., 2017). However, dechorionation prior to natural hatching does not accurately represent developmental exposure, hence our use of hatched larvae.

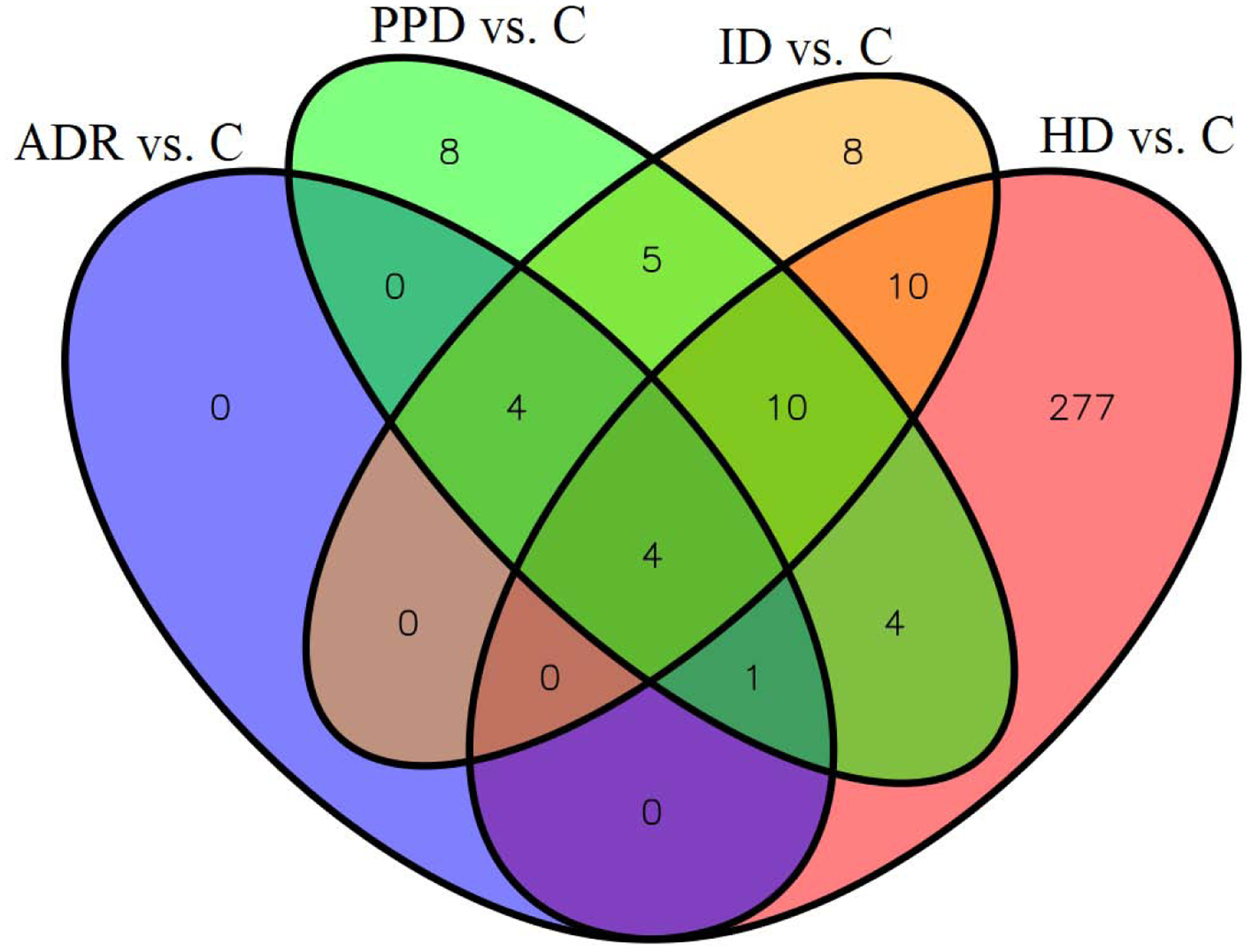

We detected differentially expressed sequences in developing zebrafish following two weeks of exposure following hatching. When compared to the control condition, the high dose cocktail exposure group revealed the largest group of differentially expressed genes: 100 upregulated, 77 downregulated (p ≤ 0.05; q ≤ 0.05). The top enriched GO:BP terms were associated with immune responses, cell cycle, and circadian rhythms.

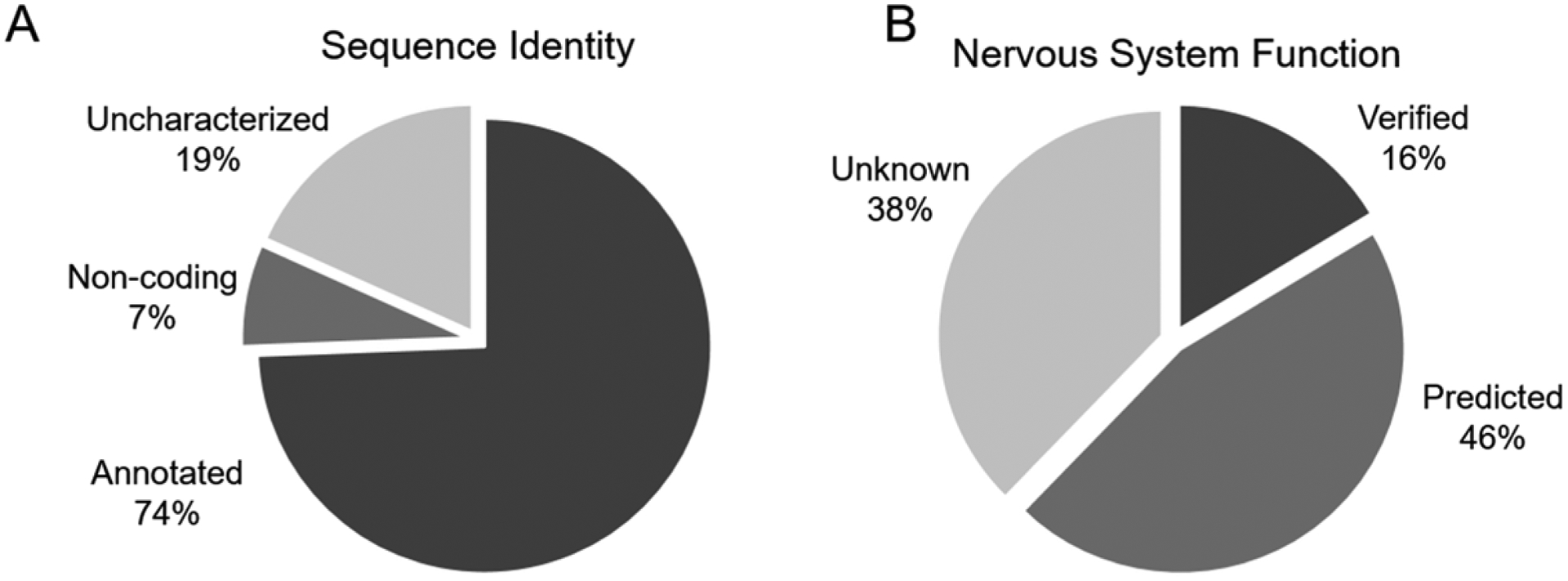

Differentially expressed genes fell into one of three categories: named protein-coding genes, non-coding RNAs and pseudogenes, and uncharacterized transcripts. BLAST analyses were used to identify homologous sequences from other species to identify unannotated zebrafish protein-coding genes. The top 20 differentially expressed sequences in each exposure group compared to control represented 82 unique transcripts. These corresponded to 74% annotated genes (Table S2), 7% non-coding sequences (Table S3), and 19% uncharacterized sequences (Table S4). Among 61 differentially expressed sequences that corresponded to annotated protein-coding genes, 10 (16 %) genes or their homologs are known to be functional in the nervous system of fish or other organisms (Table S2) and 28 (46%) are predicted to function in the nervous system based on reported gene expression. The remaining 23 genes (38%) have insufficient functional or expression data to verify or predict their functions in the nervous sytem.

Of those genes that were previously identified in the nervous system, only a handful have identified nervous system functions – sacsin, plekstrin, mcm7, retreg1, nr1d1, and p2rx7. Sacsin is a molecular chaperone protein (Anderson et al., 2011) that has been linked to cerebellar ataxia in mice (Lariviere et al., 2019; Lariviere et al., 2015; Takiyama, 2007) and was upregulated following high dose drug exposure. Upregulation following drug exposure may indicate increased need for chaperone proteins due to cellular stress. Pleckstrin is a major protein kinase C substrate found in platelets that was upregulated following prescribed drug exposure. Pleckstrin has only recently been described in the nervous system, where it is associated with the cytoskeleton of growing neurites in cultured cells (Guo et al., 2019) and the spiral ganglion neurons in the adult mouse cochlea (Lezirovitz et al., 2020). In situ hybridization reveals widespread, unspecified expression in the zebrafish head (Thisse and Thisse, 2004), suggesting pleckstrin may also be involved in zebrafish neurite growth, though the effect pleckstrin upregulation following drug exposure is unclear. Mcm7 is a minichromosome maintenance complex protein that is involved in the G1 to S phase transition of the cell cycle, and is expressed in CNS neurons and glia following injury (Chen et al. 2013). Mcm7 is also expressed in Down syndrome models of neuroblast proliferation (Hewitt et al., 2010). While the expression and function of mcm7 in zebrafish are unknown, we expect mcm7 is associated with areas of proliferation and its upregulation following drug exposure may be in response to neuronal insult. Retreg1 encodes an ER-Golgi processing protein involved in negative regulation of apoptosis and reticulophagy (Khaminets et al., 2015). Retreg1 is necessary for the survival of nociceptive and autonomic ganglion neurons (Kurth et al., 2009), though its function in zebrafish is untested. The drug exposure-induced downregulation of retreg1 suggests more cells are at risk of apoptosis. Nr1d1 is expressed in the superchiasmatic nucleus of the hypothalamus, retina, pineal gland, and superior colliculus, where it is involved in circadian rhythms (Ueda et al., 2005), though the effects of nr1d1 downregulation following drug exposure are unclear. P2rx7 is a purinergic receptor involved in calcium transport in several neuronal cell types in other species (Metzger et al., 2017) including hippocampal neurons (Sperlágh et al., 2002), and in several regions of the zebrafish CNS (Appelbaum et al., 2007). P2rx7 is also responsible for the ATP-dependent lysis of macrophages (Lammas et al., 1997). P2rx7 downregulation could be associated with increased immune activity or changes in calcium transport in stressed cells.

Several annotated genes (mov10b.2, mmp9, slc47a2.2, cmpk2, igfbp1b, hamp, hspb9, dusp27, aste1a, vgll1, and mfap4) are expressed in the nervous system of zebrafish or other species but the functions therein are currently speculative (Table S2). MOV10, the human homolog of mov10b.2, is an RNA helicase involved in microRNA-mediated gene silencing (Meister et al., 2005). MOV10 is expressed in a wide variety of tissues, including the nervous system (Skariah et al., 2017). The zebrafish mov10b.2 gene may be involved in microRNA related regulation of gene expression in the developing nervous system and its upregulation could have wide-ranging effects on transcription. Mmp9 encodes a matrix metallopeptidase that is best characterized for its roles in normal physiological breakdown of extracellular matrix and immune responses, though it is also expressed in the regenerating zebrafish retina (Kaur et al., 2018; Sharma et al., 2019), where it may be involved in remodeling the extracellular matrix to allow axonal regeneration. Downregulation of mmp9 may be associated with the slowing of normal cellular processes during stress, which could affect axon outgrowth and pathfinding. Slc47a2.2 is uncharacterized in zebrafish, though the widely expressed mammalian homolog is linked to excretion of toxins (Otsuka et al., 2005) which is unsurprising, given that the conditions of the present study resulted in slc47a2.2 upregulation. Cmpk2 is a nucleoside monophosate kinase in mitochondria that is present in all zebrafish tissues, including the nervous system, that is upregulated in response to immune activation (Liu et al., 2019). Igfbp1b encodes an insulin-like growth factor binding protein that is enriched in the liver of zebrafish (Kamei et al., 2008), as is its mammalian homolog, and the drug exposure-induced differential gene expression is most likely due to changes in liver expression. However, igfbp1 is expressed in the fetal brains of rhesus monkeys (Lee et al., 2001), where it functions in growth factor signaling. Similarly, the differential expression in the current study of hamp, hepcidin antimicrobial peptide and iron regulatory hormone, is likely due to changes in liver expression, where hamp is produced during conditions of inflammation (Nemeth et al., 2004a) or high iron (Nemeth et al., 2004b). Why drug exposure led to hamp downregulation is unclear. Hamp is expressed in neural tissues (Zechel et al. 2006), including the hippocampus where plays a role in social recognition (Ji et al., 2019), though exact mechanisms are not yet clear. Hspb9 (heat shock protein family B (small) 9) is also abundant in the d liver (Stelzer et al., 2016), which could represent the differential expression caused by drug exposure. However, hspb9 is also expressed in the hindbrain (Marvin et al., 2008), though the function therein and the effects of hspb9 downregulation are unclear. Dusp27 (alias STYXL2 – serine/threonine/tyrosine interacting like 2) is a phosphatase that is expressed in the zebrafish optic tectum and somites, where it is required for assembly of the muscle contraction apparatus (Fero et al., 2014). Requirements for dusp27 in the nervous system are not yet understood and the drug-associated downregulation may be associated with changes in muscle expression. Aste1a is a homolog of the drosophila asteroid whose function in zebrafish is as yet unknown. ASTE1, the human homolog of aste1a, is expressed neural tissues (Uhlén et al., 2015), though the functions in neural tissues are uncharacterized. VGLL1 is a poorly characterized transcription factor that is expressed in the neural ectoderm (Fasano et al., 2010), though its function therein is unknown. Mfap4 exists in multiple copies in zebrafish and is expressed in primarily macrophages, including brain macrophages (a population distinct from microglia) that are present in the perivascular spaces (Wu et al., 2018) where it is involved in cellular adhesion. Mammals also express MFAP4 in the hypothalamus (Ferran et al., 2015). Therefore, Mfap4 downregulation is most likely associated with immune responses rather than nervous system development.

Furthermore, an additional 34 (56%) of the annotated differentially expressed sequences (sepina7, dhx58, fbxo32, rsad2, ftr86, col14a1b, and calcoco1) (Table S2) or their homologs are predicted to be expressed in the nervous system, based on previously published low-resolution expression in the head via large scale in situ hybridization, RNA sequencing, or proteomics, which leaves potential nervous system functions even more speculative. Some of these genes are confirmed or predicted to be expressed in the nervous system, though differential expression observed in the current study is likely to do other tissues, particularly as some of these genes are ubiquitously expressed, or nearly so. Serpina7 is a thyroxine-binding globulin expressed in the blood and liver (Kiba et al., 2009) that was downregulated in each condition that featured prescribed drugs. The differential expression of serpina7 in the present study may indeed be due to changes in liver expression. However, serpina7 may also be expressed in the nervous system, as in situ hybridization reveals widespread, unspecified expression in the developing zebrafish head (Thisse and Thisse, 2004) and proteomics estimate mild enrichment of serpina7 in the cerebral cortex (Stelzer et al., 2016), though its potential function in neural tissue is unclear. Dhx58 is a predicted component of innate immune signaling in mammals, where it is also expressed in the nervous system (Uhlén et al., 2015). Whether the zebrafish dhx58 is expressed or functions in the CNS is unknown and the differential gene expression following drug exposure may be due to changes in immune tissues. The gene product of fbxo32 contains an F-box, which is associated with phosphorylation-dependent ubiquitination (Bodine et al., 2001). The human FBXO32 is necessary for autophagosome formation and overexpression in neurons can trigger apoptosis (Murdoch et al., 2016). The zebrafish fbxo32 is expressed in several tissues, though is enriched in muscle tissue (Bühler et al., 2016). Fbxo32 downregulation following drug exposure may protect vulnerable cells from apoptosis. Rsad2 is an interferon-induced antiviral protein that is expressed in several tissues, including the brain (Uhlén et al., 2015). The upregulation of rsad2 following drug exposure is most likely due to changes in other body tissues with higher rsad2 expression. Ftr86 is homologous to human TRIM29, a minimally characterized DNA-binding protein is linked to immune system regulation, with unresolved nervous system expression in humans (Uhlén et al., 2015; Stelzer et al., 2016). It is not known to be expressed in the nervous system and the differential expression of ftr86 is likely due to immune system activation. Col14a1b was upregulated following high dose drug exposure. Collagens are not expressed in the central nervous system (except in the meninges), though they are associated with the peripheral nervous system. This differentially expressed collagen is associated with cartilage (Bader et al., 2013) and may represent changes in neural crest gene expression. The transcription factor calcoco1b is poorly characterized in zebrafish, though its human orthologue CALCOCO1 is a nuclear receptor coactivator expressed in many tissues and enriched in the nervous system (Uhlén et al., 2015). Functional data for many of these genes is lacking, making it difficult to predict their potential roles in nervous system development or function. In these cases, the low resolution gene expression data is thus far the best indication that these genes are indeed somehow influencing nervous system development.

Several of the differentially expressed sequences are poorly characterized in zebrafish and similar genes were identified through BLAST alignments. As such, it is tenuous to make predictions about the functions of these genes. The largest group of annotated genes are very poorly characterized and have limited expression data. These genes (Cystatin-like protein, NLRC3-like, FAM111a-like, probable E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase HERC4-like, tetraspanin-like, nxpe family member 3-like, retinol dehydrogenase 12-like, pleckstrin homology domain-containing family member S 1-like, ER-Golgi intermediate compartment protein 2-like, pgbd4-like, GTPase IMAP family member 7-like, NACHT LRR and PDYD domains-containing protein 12 and 3-like, tubb4bl, interferon-induced very large GTPase 1-like, CLEC4M, jac9, and klhl38b), are neither described as expressed in the nervous system or absent from the nervous system, leaving it an open question. Klhl38b represents a gene duplication in zebrafish of a poorly characterized transcriptional enhancer. The mammalian KLHL38 homolog is primarily expressed in muscle (Ehrlich et al., 2020), though nervous system expression remains possible. As such, the differential expression in the present study of klhl38b most likely represents differential muscle expression. Two remaining genes are sufficiently well-characterized with no described expression in the nervous system that the differential gene expression is likely due to non-neural tissues: mpx is a myeloid-specific peroxidase and hbbe1.1 is an embryonic hemoglobin.

From the differential gene expression of annotated versus novel sequences, plus verified versus predicted nervous system functions, we predict a majority of the differentially regulated genes in this analysis affect nervous system development and/or function. How those changes in gene expression manifest in the organism is beyond the scope of this project. We expect the differential expression of each of these genes to have a minor effect on the organism, and that the summative changes in gene expression may have complex and varied effects on zebrafish. We conclude that exposure to neuroactive compounds induces changes in nervous system gene expression.

3.4. Connections to human disease

Several of the differentially expressed sequences are associated primarily with the immune system, including several major histocompatibility complex class I (MHCI; mhc1lja, mhc1zfa, mhc1uba, and mhc1lfa) and interferon-induced proteins (ifit44 X1, ifit8, ifit14, and ifit15). Many of the genetic associations linked to schizophrenia in humans converge on immune responses and genes associated with the immune system. In particular, MHCI expression in the brain is altered in schizophrenia (McAllister 2004). Furthermore, cytokine production from immune activation is associated with schizophrenia. Specifically, interleukin-1 beta (downregulated in the present study) abnormalities are considered a risk factor for psychosis (Mostaid et al., 2019) possibly due to its role in guiding the migration of cortical neurons during development (Ma et al., 2014).

Parkinson’s disease has complex etiology with both genetic and environmental risk factors and involves abnormal expression of many genes, some of which were detected in this study. Elovl7b is a fatty acid elongase found in most tissues, notably in the oligodendrocytes in the CNS (Keo et al., 2020; Shin et al., 2009) where it functions to extend fatty acids, presumably associated with myelin production. Downregulation of ELOVL7 in oligodendrocytes is associated with Parkinson’s susceptibility (Li et al., 2018; Keo et al., 2020). The proteasome activator psme4a promotes ubiquitin-independent protein degradation. Psme4a may be involved in necessary protein recycling in the developing zebrafish. Downregulation of PSME4 has been linked to Parkinson’s disease via bioinformatics analysis and confirmed in patients with the disease (Yuan et al., 2020), though causation has not been established.

Other genes that were differentially expressed genes are known to be expressed in brain vasculature, where abnormal gene expression can have neurological consequences. Epgn is an epithelial mitogen homolog that is enriched primarily in epithelial tissues and vasculature, (Stelzer et al. 2016), where its function therein is unexplored. Crp2 and cpr3 encode pentaxin-related proteins that are orthologues to the human CRP gene. Zebrafish crp2 and cpr3 expression patterns are unexplored, though mammalian CRP is expressed in a variety of tissues and is enriched primarily in epithelial tissues and vasculature, including those within the nervous system, where CRP influences blood-brain-barrier permeability (Hsuchou et al., 2012). Rnf213b is a ring finger protein that possesses both ubiquitin ligase and ATPase activities and is required for normal vascular development in zebrafish (Liu et al., 2011). Whether or not rnf213b is also required in neurons has not been explored, though abnormal vessel sprouting in the developing head could have neurological consequences. Expression of abnormal RNF213 in humans is associated with moyamoya, a rare narrowing of the internal carotid arteries that limits blood to the brain. Due to incomplete penetrance of the disease, RNF213 is postulated to act with environmental factors to result in moyamoya (Koizumi et al., 2015). Our results support the role of the environment in developmental expression of rnf213b.

4. Conclusion

Thirty-six psychotic and illicit drug residues were determined in discharged wastewater from two centralized municipal wastewater treatment facilities and two wastewater receiving creeks in Kentucky. The majority of the target drugs including illicit stimulants as well as potential drug of abuse including opioids, sedatives, and antidepressants were found discharged from the WWTPs to the creek at a weekly average level of 2.79 ng/L (diazepam) to 858 ng/L (Heroin). The weekly level of drugs in immediate receiving creeks ranged from 2.02 ng/L (cocaethylene, a metabolite of cocaine) to 434 ng/L (Heroin). Zebrafish larvae were exposed to the environmental relevant mixtures of all drug residues, all illicit drugs, and all prescribed psychotic drugs. The high dose cocktail mixture exposure revealed the largest group of differentially expressed genes: 100 upregulated and 77 downregulated (p ≤ 0.05; q ≤ 0.05). Among 61 differentially expressed sequences that corresponded to annotated protein-coding genes, 23 (38%) genes or their homologs are known to be expressed in the nervous system of fish or other organisms. Several of the differentially expressed sequences are associated primarily with the immune system, including several major histocompatibility complex class I and interferon-induced proteins. Interleukin-1 beta (downregulated in this study) abnormalities are considered a risk factor for psychosis. To our knowledge, this is the first study to assess the contributions of multiple classes of drugs in combination with developmental gene expression. The fact that these drugs are found in the water bodies that are a potential source of drinking water, humans are also exposed to low-level drugs in combination. This route of exposure is most concerning for pregnant women, as many of these drugs or their metabolites would reach the embryonic brain.

Supplementary Material

Figure 2.

The number of common and unique differentially expressed genes across comparisons. The differentially expressed genes were mostly unique to the high dose mixture groups, though some genes were also differentially expressed in the other groups with varying degrees of overlap. ADR: mixture of all drug residues quantified in creeks A and B; PPD: mixture of all prescribed psychotic drug residues quantified in creeks A and B; ID: mixture of all illicit drug residues quantified in creeks A and B; HD: high dose mixture of all target drug residues reported in surface water elsewhere at the highest concentrations; C: control.

Figure 3.

Of the top differentially expressed sequences, approximately 25% represent novel or non-protein-coding genes (A). Of the annotated differentially expressed sequences, most have verified or predicted nervous system function (B).

Highlights.

Thirty-six psychotic and illicit drug residues determined in surface water

Zebrafish larvae were exposed to the psychotic and illicit drug residues

Cocktail mixture exposure differentially expressed genes

Differentially expressed genes correspond to the immune system

Acknowledgments

Authors are thankful to The Jones/Ross Research Center at the Department of Chemistry, Murray State University for providing access to the UPLC-MS/MS and Sabnine Waigel, University of Louisville Genomics Facility, for support in the Next Generation Sequencing experiments. Wastewater treatment plants are acknowledged for providing access to the 24 h composite wastewater samples.

Funding source disclosure

This study was funded by grants from the Kentucky Biomedical Research Infrastructure Network (NIGMS P20GM103436). Sequencing and bioinformatics support for this work provided by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants P20GM103436 (Nigel Cooper, PI) and P20GM106396 (Donald Miller, PI). The contents of this work are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not represent the official views of the NIH or the National Institute for General Medical Sciences (NIGMS).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Competing interest statement

The authors are not aware of any substantive or perceived competing interest concerning this work.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Anderson JF, Siller E, Barral JM, 2011. The neurodegenerative-disease-related protein sacsin is a molecular chaperone. J. Mol. Biol 411, 870–880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appelbaum L, Skariah G, Mourrain P, Mignot E, 2007. Comparative expression of p2x receptors and ecto-nucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase 3 in hypocretin and sensory neurons in zebrafish. Brain Res. 1174, 66–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bader HL, Lambert E, Guiraud A, Malbouyres M, Driever W, Koch M, Ruggiero F, 2013. Zebrafish collagen XIV is transiently expressed in epithelia and is required for proper function of certain basement membranes. J. Biol. Chem 288, 6777–6787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker DR; Barron L; Kasprzyk-Hordern B, 2014. Illicit and pharmaceutical drug consumption estimated via wastewater analysis. Part A: chemical analysis and drug use estimates. Sci. Total Environ 487, 629–641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bareis N; Sando TA; Mezuk B; Cohen SA, 2018. Association between psychotropic medication polypharmacy and an objective measure of balance impairment among middle-aged adults: Results from the US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. CNS Drugs 32, 863–871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartelt-Hunt SL; Snow DD; Damon T; Shockley J; Hoagland K, 2009. The occurrence of illicit and therapeutic pharmaceuticals in wastewater effluent and surface waters in Nebraska. Environ. Pollut 157, 786–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bijlsma L; Emke E; Hernandez F; de Voogt P, 2012. Investigation of drugs of abuse and relevant metabolites in Dutch sewage water by liquid chromatography coupled to high-resolution mass spectrometry. Chemosphere 89, 1399–1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodine SC, Latres E, Baumhueter S, Lai VK, Nunez L, Clarke BA, Poueymirou WT, Panaro FJ, Na E, Dharmarajan K, Pan ZQ, Valenzuela DM, DeChiara TM, Stitt TN, Yancopoulos GD, Glass DJ, 2001. Identification of ubiquitin ligases required for skeletal muscle atrophy. Science. 294, 1704–1708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosse GD; Peterson RT, 2017. Development of an opioid self-administration assay to study drug seeking in Zebrafish. Behav. Brain Res 335, 158–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodin T; Piovano S; Fick J; Klaminder J; Heynen M; Jonsson M, 2014. Ecological effects of pharmaceuticals in aquatic systems—impacts through behavioral alterations. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. London, Ser. B 369, 20130580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bühler A, Kustermann M, Bummer T, Rottbauer W, Sandri M, Just S, 2016. Atrogin-1 deficiency leads to myopathy and heart failure in Zebrafish. Int. J. Mol. Sci 17, 187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerveny D; Brodin T; Cisar P; McCallum ES; Fick J, 2020. Bioconcentration and behavioral effects of four benzodiazepines and their environmentally relevant mixture in wild fish. Sci. Total Environ, 702, 134780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Cui Z, Li W, Shen A, Xu G, Bao G, Sun Y, Wang L, Fan J, Zhang J, Yang L, Cui Z, 2013. MCM7 expression is altered in rat after spinal cord injury. J. Mol. Neurosci 51, 82–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croft TL, Huffines RA, Pathak M, Subedi B, 2020. Prevalence of illicit and prescribed neuropsychiatric drugs in three communities in Kentucky using wastewater-based epidemiology and Monte Carlo simulation for the estimation of associated uncertainties. J. Hazard. Mater 384, 121360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daughton CG; Ternes TA, 1999. Pharmaceuticals and personal care products in the environment: agents of subtle change? Environ. Health Perspect 107, 907–938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobin A; Davis CA; Schlesinger F; Drenkow J; Zaleski C; Jha S; Batut P; Chaisson M; Gineras TR, 2013. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29, 15–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich KC, Baribault C, Ehrlich M, 2020. Epigenetics of muscle- and brain-specific expression of KLHL family genes. Int. J. Mol. Sci 21, 8394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fasano CA, Chambers SM, Lee G, Tomishima MJ, Studer L, 2010. Efficient derivation of functional floor plate tissue from human embryonic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 6, 336–347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Felice BD; Salguiero-Gonzalez N; Castiglioni S; Saino N; Parolini M, 2019. Biochemical and behavioral effects induced by cocaine exposure to Daphnia magna. Sci. Total Environ 689, 141–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fero K, Bergeron SA, Horstick EJ, Codore H, Li GH, Ono F, Dowling JJ, Burgess HA, 2014. Impaired embryonic motility in dusp27 mutants reveals a developmental defect in myofibril structure. Dis. Model Mech 7, 289–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferran JL, Puelles L, Rubenstein JL, 2015. Molecular codes defining rostrocaudal domains in the embryonic mouse hypothalamus. Front Neuroanat. 17, 9–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuentes AV; Pineda MD; Venkata KCN, 2018. Comprehension of top 200 prescribed drugs in the US as a resource for pharmacy teaching, training, and practice. Pharmacy 6, 43–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galus M; Jeyaranjann J; Smith E; Li H; Metcalfe C; Wilson JY, 2013. Chronic effects of exposure to a pharmaceutical mixture and municipal wastewater in zebrafish. Aquat. Toxicol 132–133, 212–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo J, Cai Y, Ye X, Ma N, Wang Y, Yu B, Wan J, 2019. MiR-409–5p as a regulator of neurite growth ss down regulated in APP/PS1 murine model of alzheimer’s disease. Front. Neurosci, 13, 1264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt CA, Ling KH, Merson TD, Simpson KM, Ritchie ME, King SL, Pritchard MA, Smyth GK, Thomas T, Scott HS, Voss AK, 2011. Gene network disruptions and neurogenesis defects in the adult Ts1Cje mouse model of Down syndrome. PLoS One 5, e11561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsuchou H, Kastin AJ, Mishra PK, Pan W, 2012. C-reactive protein increases BBB permeability: implications for obesity and neuroinflammation. Cell Physiol Biochem. 30, 1109–1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji P, Lönnerdal B, Kim K, Jinno CN, 2019. Iron over supplementation causes hippocampal iron overloading and impairs social novelty recognition in nursing piglets. J. Nutr 149, 398–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson M; Zaretskaya I; Raytselis Y; Merezhuk Y; McGinnis S; Madden TL, 2008. NCBI BLAST: a better web interface. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, W5–W9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamei H, Lu L, Jiao S, Li Y, Gyrup C, Laursen LS, Oxvig C, Zhou J, Duan C, 2008. Duplication and diversification of the hypoxia-inducible IGFBP-1 gene in zebrafish. PLoS One 3, e3091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaushik G; Thomas MA, 2019. The potential association of psychoactive pharmaceuticals in the environment with human neurological disorders. Sustainable Chem. Pharm 13, 100148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaushik G, Xia Y, Yang L, Thomas MA, 2016. Psychoactive pharmaceuticals at environmental concentrations induce in vitro gene expression associated with neurological disorders. BMC Genomics, 17, 435–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KASPER (Kentucky All Schedule Prescription Electronic Reporting), 2020. Quarterly Trend Report 1st Quarter 2020. https://chfs.ky.gov/agencies/os/oig/dai/deppb/Documents/KASPER_Quarterly_Trend_Report_Q1_2020.pdf (accessed 2020/11/10).

- Kaur S, Gupta S, Chaudhary M, Khursheed MA, Mitra S, Kurup AJ, Ramachandran R, 2018. let-7 MicroRNA-mediated regulation of Shh signaling and the gene regulatory network is essential for retina regeneration. Cell Rep. 23, 1409–1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keo A, Mahfouz A, Ingrassia AMT, Meneboo JP, Villenet C, Mutez E, Comptdaer T, Lelieveldt BPF, Figeac M, Chartier-Harlin MC, van de Berg WDJ, van Hilten JJ, Reinders MJT, 2020. Transcriptomic signatures of brain regional vulnerability to Parkinson’s disease. Commun Biol. 3, 101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khaminets A, Heinrich T, Mari M, Grumati P, Huebner AK, Akutsu M, Liebmann L, Stolz A, Nietzsche S, Koch N, Mauthe M, Katona I, Qualmann B, Weis J, Reggiori F, Kurth I, Hübner CA, Dikic I, 2015. Regulation of endoplasmic reticulum turnover by selective autophagy. Nature. 522, 354–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiba T, Kintaka Y, Suzuki Y, Nakata E, Ishigaki Y, Inoue S, 2009. Gene expression profiling in rat liver after VMH lesioning. Exp. Biol. Med 234, 758–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KIPRC (Kentucky Injury Prevention and Research Center), 2019. Dose and Overdose report. http://www.mc.uky.edu/kiprc/pubs/overdose/index.html (accessed 2020/11/10)

- Koizumi A, Kobayashi H, Hitomi T, Harada KH, Habu T, Youssefian S, 2016. A new horizon of moyamoya disease and associated health risks explored through RNF213. Environ Health Prev Med. 21, 55–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurth I, Pamminger T, Hennings JC, Soehendra D, Huebner AK, Rotthier A, Baets J, Senderek J, Topaloglu H, Farrell SA, Nürnberg G, Nürnberg P, De Jonghe P, Gal A, Kaether C, Timmerman V, Hübner CA, 2009. Mutations in FAM134B, encoding a newly identified Golgi protein, cause severe sensory and autonomic neuropathy. Nat. Genet 41, 1179–1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lammas DA, Stober C, Harvey CJ, Kendrick N, Panchalingam S, Kumararatne DS, 1997. ATP-induced killing of mycobacteria by human macrophages is mediated by purinergic P2Z(P2X7) receptors. Immunity 7, 433–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larivière R, Gaudet R, Gentil BJ, Girard M, Conte TC, Minotti S, Leclerc-Desaulniers K, Gehring K, McKinney RA, Shoubridge EA, McPherson PS, Durham HD, Brais B 2015. Sacs knockout mice present pathophysiological defects underlying autosomal recessive spastic ataxia of Charlevoix-Saguenay. H. Mol. Genet 24, 727–739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larivière R, Sgarioto N, Márquez BT, Gaudet R, Choquet K, McKinney RA, Watt AJ, Brais B, 2019. Sacs R272C missense homozygous mice develop an ataxia phenotype. Mol. Brain 12, 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CI, Goldstein O, Han VK, Tarantal AF, 2001. IGF-II and IGF binding protein (IGFBP-1, IGFBP-3) gene expression in fetal rhesus monkey tissues during the second and third trimesters. Pediatr. Res 49, 379–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SS; Paspalof AM; Snow DD; Richmond EK; Rosi-Marshall EJ; Kelly JJ, 2016. Occurrence and potential biological effects of amphetamine on stream communities. Environ. Sci. Technol 50, 9727–9735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lezirovitz K, Vieira-Silva GA, Batissoco AC, Levy D, Kitajima JP, Trouillet A, Ouyang E, Zebarjadi N, Sampaio-Silva J, Pedroso-Campos V, Nascimento LR, Sonoda CY, Borges VM, Vasconcelos LG, Beck R, Grasel SS, Jagger DJ, Grillet N, Bento RF, Mingroni-Netto RC, Oiticica J, 2020. A rare genomic duplication in 2p14 underlies autosomal dominant hearing loss DFNA58. Hum. Mol. Genet 29, 1520–1536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G, Cui S, Du J, Liu J, Zhang P, Fu Y, He Y, Zhou H, Ma J, Chen S, 2018. Association of GALC, ZNF184, IL1R2 and ELOVL7 With Parkinson’s disease in Southern Chinese. Front Aging Neurosci. 13, 402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W, Morito D, Takashima S, Mineharu Y, Kobayashi H, Hitomi T, Hashikata H, Matsuura N, Yamazaki S, Toyoda A, Kikuta K, Takagi Y, Harada KH, Fujiyama A, Herzig R, Krischek B, Zou L, Kim JE, Kitakaze M, Miyamoto S, Nagata K, Hashimoto N, Koizumi A, 2011. Identification of RNF213 as a susceptibility gene for moyamoya disease and its possible role in vascular development. PLoS One 6, e22542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W, Chen B, Chen Li., Yao J, Liu J, Kuang M, Wang F, Wang Y, Elkady G, Lu Y, Zhang Y, Liu X, 2019. Identification of fish CMPK2 as an interferon stimulated gene against SVCV infection. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 92, 125–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love M, Anders S, Huber W, 2014. Differential analysis of count data-the DESeq2 package. Genome Biol. 15, 550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L, Li XW, Zhang SJ, Yang F, Zhu GM, Yuan XB, Jiang W, 2014. Interleukin-1 beta guides the migration of cortical neurons. J. Neuroinflamm 11, 114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marvin M, O’Rourke D, Kurihara T, Juliano CE, Harrison KL, Hutson LD, 2008. Developmental expression patterns of the zebrafish small heat shock proteins. Dev. Dyn 237, 454–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAllister AK, 2014. Major histocompatibility complex I in brain development and schizophrenia. Biol. Psychiat 75, 262–268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meister G, Landthaler M, Peters L, Chen PY, Urlaub H, Lührmann R, Tuschl T, 2005. Identification of novel argonaute-associated proteins. Curr Biol. 15, 2149–2155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzger MW, Walser SM, Aprile-Garcia F, Dedic N, Chen A, Holsboer F, Arzt E, Wurst W, Deussing JM, 2017. Genetically dissecting P2rx7 expression within the central nervous system using conditional humanized mice. Purinergic Signal. 13, 153–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mostaid MS, Dimitrakopoulos S, Wannan C, Cropley V, Weickert CS, Everall IP, Pantelis C, Bousman CA, 2019. An Interleukin-1 beta (IL1B) haplotype linked with psychosis transition is associated with IL1B gene expression and brain structure. Schizophr. Res 204, 201–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murdoch JD, Rostosky CM, Gowrisankaran S, Arora AS, Soukup SF, Vidal R, Capece V, Freytag S, Fischer A, Verstreken P, Bonn S, Raimundo N, Milosevic I, 2016. Endophilin-A deficiency induces the Foxo3a-Fbxo32 network in the brain and causes dysregulation of autophagy and the ubiquitin-proteasome system. Cell Rep. 17, 1071–1086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neelkantan N; Mikhaylova A; Stewart AM; Arnold R; Gjeloshi V; Kondaveeti D; Poudel MK; Kalueff AV, 2013. Perspectives on Zebrafish models of hallucinogenic drugs and related psychotropic compounds. ACS Chem. Neurosci 4, 1137–1150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemeth E, Rivera S, Gabayan V, Keller C, Taudorf S, Pedersen BK, Ganz T, 2004a. IL-6 mediates hypoferremia of inflammation by inducing the synthesis of the iron regulatory hormone hepcidin. J. Clin. Invest 113, 1271–1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemeth E, Tuttle MS, Powelson J, Vaughn MB, Donovan A, Ward DM, Ganz T, Kaplan J, 2004b. Hepcidin regulates cellular iron efflux by binding to ferroportin and inducing its internalization. Science 306, 2090–2093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otsuka M, Matsumoto T, Morimoto R, Arioka S, Omote H, Moriyama Y, 2005. A human transporter protein that mediates the final excretion step for toxic organic cations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 102, 17923–17928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parolini M; Bini L; Magni S; Rizzo A; Ghilardi A; Landi C; Armini A; Giacco LD; Binelli A, 2018. Exposure to cocaine and its main metabolites altered the protein profile of zebrafish embryos. Environ. Pollut 232, 603–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parolini M; Ghilardi A; Torre CD; Magni S; Prosperi L; Calagno M; Giacco LD; Binelli A, 2017. Environmental concentrations of cocaine and its main metabolites modulated antioxidant response and caused cyto-genotoxic effects in zebrafish embryo cells. Environ. Pollut 226, 504–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parolini M; Pedriali A; Riva C; Binelli A, 2013. Sub-lethal effects caused by the cocaine metabolite benzoylecgonine to the freshwater mussel Dreissena polymorpha. Sci. Total Environ 444, 43–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelka KE, Henn K, Keck A, Sapel B, Braunbeck T, 2017. Size does matter - Determination of the critical molecular size for the uptake of chemicals across the chorion of zebrafish (Danio rerio) embryos. Aquat. Toxicol 185, 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAMHSA, 2019. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. PEP19–5068, NSDUH Series H-54). Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/ (accessed 2020/11/10). [Google Scholar]

- Schultz MM; Furlong ET; Kolpin DW; Werner SL; Schoernfuss HL; Barber LB; Blazer VS; Norris DO; Vajda AM, 2010. Antidepressant pharmaceuticals in two U.S. effluent-impacted streams: occurrence and fate in water and sediment, and selective uptake in fish neural tissue. Environ, Sci. Technol 44, 1918–1925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCORE (Sewage Analysis CORe Group Europe), 2019: SCORE monitoring 2019. Avaialble at https://score-cost.eu/wp-content/uploads/sites/118/2020/03/SCORE_2019_publish_12m.pdf. (accessed 2020/11/10).

- Sharma P, Gupta S, Chaudhary M, Mitra S, Chawla B, Khursheed MA, Ramachandran R, 2019. Oct4 mediates Müller glia reprogramming and cell cycle exit during retina regeneration in zebrafish. Life Sci. Alliance 2, e201900548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin D, Shin JY, McManus MT, Ptácek LJ, Fu YH, 2009. Dicer ablation in oligodendrocytes provokes neuronal impairment in mice. Ann Neurol. 66, 843–857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skariah G, Seimetz J, Norsworthy M, Lannom MC, Kenny PJ, Elrakhawy M, Forsthoefel C, Drnevich J, Kalsotra A, Ceman S, 2017. Mov10 suppresses retroelements and regulates neuronal development and function in the developing brain. BMC Biol. 15, 54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skees AJ, Foppe KS, Loganathan B, Subedi B, 2018. Contamination profiles, mass loadings, and sewage epidemiology of neuropsychiatric and illicit drugs in wastewater and river waters from a community in the Midwestern United States. Sci. Total. Environ 631–632, 1457–1464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperlágh B, Köfalvi A, Deuchars J, Atkinson L, Milligan CJ, Buckley NJ, Vizi ES, 2002. Involvement of P2X7 receptors in the regulation of neurotransmitter release in the rat hippocampus. J. Neurochem 81, 1196–1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stelzer G, Rosen N, Plaschkes I, Zimmerman S, Twik M, Fishilevich S, Stein TI, Nudel R, Lieder I, Mazor Y, Kaplan S, Dahary D, Warshawsky D, Guan-Golan Y, Kohn A, Rappaport N, Safran M, Lancet D, 2016. The GeneCards Suite: From Gene Data Mining to Disease Genome Sequence Analyses. Curr. Protoc. Bioinformatics 54, 1.30.1–1.30.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart A; Reihl R; Wong K; Green J; Cosgrove J; Vollmer K; Kuzer E; Hart P; Allain A; Cachat K; Gaikwad S; Hook M; Rhymes K; Newman A; Utterback E; Chang K; Kalueff AV, 2011. Behavioral effects of MDMA (“Ecstasy”) on adult zebrafish. Behav. Pharmacol 22, 275–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subedi B; Kannan K, 2014. Mass loading and removal of select illicit drugs in two wastewater treatment plants in New York State and estimation of illicit drug usage in communities through wastewater analysis. Environ. Sci. Technol 48, 6661–6670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subedi B; Kannan K, 2015. Occurrence and fate of select psychoactive pharmaceuticals and antihypertensives in two wastewater treatment plants in New York State, USA. Sci. Total. Environ 514, 273–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takiyama Y, 2007. Sacsinopathies: sacsin-related ataxia. Cerebellum 6, 353–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thisse B, Thisse C, 2004. Fast Release Clones: A High Throughput Expression Analysis. ZFIN Direct Data Submission. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson WA; Arnold VI; Vijayan MM, 2017. Venlafaxine in embryos stimulates neurogenesis and disrupts larval behavior in Zebrafish. Environ. Sci. Technol 51, 12889–12897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapnell C; Roberts A; Goff L; Pertea G; Kim D; Kelley DR; Pimentel H; Salzberg SL; Rinn JL; Pachter L, 2012. Differential gene and transcript expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with TopHat and Cufflinks. Nat. Protoc 7, 562–578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueda HR, Hayashi S, Chen W, Sano M, Machida M, Shigeyoshi Y, Iino M, Hashimoto S, 2005. System-level identification of transcriptional circuits underlying mammalian circadian clocks. Nat. Genet 37, 187–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhlén M, Fagerberg L, Hallström BM, Lindskog C, Oksvold P, Mardinoglu A, Sivertsson Å, Kampf C, Sjöstedt E, Asplund A, Olsson I, Edlund K, Lundberg E, Navani S, Szigyarto CA, Odeberg J, Djureinovic D, Takanen JO, Hober S, Alm T, Edqvist PH, Berling H, Tegel H, Mulder J, Rockberg J, Nilsson P, Schwenk JM, Hamsten M, von Feilitzen K, Forsberg M, Persson L, Johansson F, Zwahlen M, von Heijne G, Nielsen J, Pontén F, 2015. Proteomics. Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science 347, 1260419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe K; Batikian CM; Pelley D; Carlson B; Pitt J; Gersberg RM, 2020. Occurrence of stimulant drugs of abuse in a San Diego, CA, stream and their consumption rates in the neighboring community. Water Air Soil Pollut. 231, 202–213. [Google Scholar]

- Wu S, Xue R, Hassan S, Nguyen TML, Wang T, Pan H, Xu J, Liu Q, Zhang W, Wen Z, 2018. Il34-Csf1r pathway regulates the migration and colonization of microglial precursors. Dev. Cell 46, 552–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yates AD; Achuthan P; Akanni W; Allen J; Allen J; Alvarez-Jarreta J, 2020. Ensembl 2020. Nucleic Acids Res. 8, D682–D688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Q, Zhang S, Li J, Xiao J, Li X, Yang J, Lu D, Wang Y, 2020. Comprehensive analysis of core genes and key pathways in Parkinson’s disease. Am. J. Transl. Res 12, 5630–5639. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zechel S, Huber-Wittmer K, von Bohlen und Halbach O, 2006. Distribution of the iron-regulating protein hepcidin in the murine central nervous system. J. Neurosci. Res 84, 790–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.