Abstract

MiR-17-92 cluster enriched exosomes derived from multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) increase functional recovery after stroke. Here, we investigate the mechanisms underlying this recovery. At 24 h (h) post transient middle cerebral artery occlusion, rats received control liposomes or exosomes derived from MSCs infected with pre-miR-17-92 expression lentivirus (Exo-miR-17-92+) or control lentivirus (Exo-Con) intravenously. Compared to the liposomes, exosomes significantly reduced the intracortical microstimulation threshold current of the contralateral cortex for evoking impaired forelimb movements (day 21), increased the neurite and myelin density in the ischemic boundary area, and contralesional axonal sprouting into the caudal forelimb area of ipsilateral side and in the denervated spinal cord (day 28), respectively. The Exo-miR-17-92+ further enhanced axon-myelin remodeling and electrophysiological recovery compared with the EXO-Con. Ex vivo cultured rat brain slice data showed that myelin and neuronal fiber density were significantly increased by Exo-miR-17-92+, while significantly inhibited by application of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway inhibitors. Our studies suggest that the miR-17-92 cluster enriched MSC exosomes enhanced neuro-functional recovery of stroke may be attributed to an increase of axonal extension and myelination, and this enhanced axon-myelin remodeling may be mediated in part via the activation of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway induced by the downregulation of PTEN.

Keywords: miR-17-92 cluster, exosome, stroke, axon-myelin unit, motor electrophysiological recovery

Introduction

Therapeutic benefits of multipotent mesenchymal stromal cell (MSC)-derived exosomes on treating preclinical models of neurological disease and injury have been demonstrated.1–5 Since the miRNA cargo of MSC exosomes contributes to the MSC-derived exosome therapeutic benefit, use of exosomes engineered to be enriched with specific miRNAs and thereby to deliver specific miRNAs for the treatment of stroke is under active investigation.6–8 Engineered exosomes that deliver key regulatory miRNAs to brain recipient cells may increase the efficacy of exosome therapy for stroke and other brain diseases.9–11 We have demonstrated that compared to control MSC exosomes, engineered exosomes derived from MSCs overexpressing the miR-17-92 cluster augment the neurological outcome improvement post stroke by increasing neurogenesis, oligodendrogenesis and neurite plasticity.11 However, the direct physiological and molecular bases for the enhanced recovery from stroke induced by the miR-17-92 enriched exosomes are unknown.

Loss or interruption of motor signals from the motor cortex to the spinal motor neurons results in hemiparalysis after stroke,12 and reestablishment of corticospinal innervation provides a physical substrate for motor functional recovery. The axons extending to the spinal cord from the cortical pyramidal neuron, i.e. the corticospinal tract (CST), form the neuroanatomical basis of brain-controlled voluntary peripheral muscle movements.13 The integrity of the CST in stroke patients determines the extent of functional disability and the potential for functional recovery.14,15 We have demonstrated that axonal remodeling of the CST in the spinal cord contributes to neurological recovery after stroke.16,17 Therefore, in the present studies, we focus on the axonal remodeling of cortical pyramidal neurons, including axonal extension and the accompanying myelination in the brain and spinal cord as mediating the miR-17-92 cluster enriched MSC exosome treatment of stroke rats. The mechanisms by which miR-17-92 cluster enriched MSC exosomes enhance axonal remodeling and myelination, and thereby electrophysiological response, and thus promote functional recovery after stroke, as well as the molecular basis of these neurorestorative processes are investigated.

Materials and methods

All experimental procedures were carried out in accordance with the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Henry Ford Health System and the experiments have been REPORTED following/in compliance with the ARRIVE (Animal Research: Reporting in Vivo Experiments) guidelines. All personnel who performed the experiments, collected data, and assessed outcome were blinded to the treatment allocation throughout the course of the experiments.

Generation of miR-17-92 cluster enriched MSC exosomes

MSCs derived from the bone marrow of male Wistar rats (Charles River, Wilmington, MA) were cultured in α-MEM with 20% FBS.18,19 Passage 3–4 MSCs at 80% confluence were infected with lentivirus made from the lentivector of pre-miRNA-17-92 cluster constructed (MMIR-17-92a-PA-CL, System Biosciences, Inc., Palo Alto, CA 94303) or corresponding empty lentivector (CD513B-1, System Biosciences, Inc.) respectively, as previously described.20 Positively infected MSCs were selected by puromycin for constant gene expression. Correspondingly, the generated MSCs are referred to as miR-17-92+MSCs and miR-CON+MSCs, and the exosomes harvested from the culture media of these MSCs are referred to as Exo-miR-17-92+ (miR-17-92 cluster elevated MSC exosome) and Exo-Con (control MSC exosome), respectively. To harvest the exosomes from MSC cultured media, we replaced conventional culture medium with a medium containing exosome depleted fetal bovine serum (FBS, EXO-FBS-250A-1, System Biosciences, Inc.) when the cell culture reached 80% confluence, and cultured the cells for an additional 24 to 48 h (h). The cultured media were then collected and centrifuged at 3000×g for 30 min (min) to remove the dead cells and large cell apoptotic bodies; then the upper media were stored in −80°C freezer for future exosome isolation. Exosome isolation from the cell cultured media was performed at 4°C via multi-step centrifugation, briefly, 10,000×g for 30 min and then 100,000×g for 2 h, as previously described.4 Freshly isolated MSC exosomes were administered to animals. The quantity of exosome was determined with the IZON qNano device (Izon, Christchurch, New Zealand).21

Middle cerebral artery occlusion model, exosome treatment and behavioral tests

Adult male Wistar rats (two to three months, weighing 270–300 g) were subjected to 2 h intraluminal filament-induced MCAO, as modified in our laboratory.22 At 24 h after the induction of stroke, Exo-miR-17-92+ or Exo-Con dissolved into 0.5 ml phosphate-buffered solution (PBS) was intravenously (iv) administered to the rats (3 × 1011 particles/rat, n = 10/group, respectively). The same volume of PBS diluted synthetic liposomes (3 × 1011 particles) which consisted of the three primary fatty acids of MSC exosomes (1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine, 19 µmol; 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine, 5 µmol; 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine, 5 µmol23) were employed as vehicle control and were used as a control group to treat rats subjected to MCAO.

For the functional outcome evaluation, an adhesive removal test was performed using three trials per day to record the time to remove each stimulus from both forelimbs, with individual trials separated by at least 5 min. In addition, a composite of motor, sensory, balance and reflex tests to obtain the modified neurological severity score (mNSS) was performed. All the functional evaluations were performed by a blinded investigator prior to MCAO and at one, three, seven days and weekly thereafter post MCAO, as previously described.24

Electrophysiological measurement

To validate the establishment of functional neuronal connections from the intact cortex to impaired forelimbs, intracortical microstimulation (ICMS) and electromyograms (EMG) were performed at 21 days post MCAO.25 Briefly, the anesthetized animal was restricted in a Kopf stereotaxic apparatus, and a unilateral craniotomy was performed over the left frontal motor cortex with a high-speed drill (Foredom Electric, Bethel, Conn). A pargyline-coated tungsten stimulating microelectrode (2.0 Megaohms, type TM33A20; WPI, Inc., Sarasota, FL) was inserted into the forelimb motor cortex to a depth of 1.5 to 1.7 mm from the cortical surface to evoke movement at four individual points (stereotaxic coordinates: 1 and 2 mm rostral to the bregma, 2.5 and 3.5 mm lateral to the midline). The electrical stimulus consisted of 20 monophasic cathodal train pulses (60 ms duration at 333 Hz, 0.5 ms pulse duration) of a maximum of 100 µA. For every stimulating point, the lowest threshold value of ICMS that evoked right forelimb movement was measured. If no movements were evoked with 100 µA, the current threshold of this point was recorded as 100 µA without additional stimulation at a higher level to avoid cerebral tissue damage. If cortical vessels were encountered at the intended incision site, the site was moved immediately rostral or caudal to avoid the cortical vessel. The average threshold values evoking right forelimb movement were calculated from the data of four stimulation points in each individual animal.

Anterograde corticospinal tract tracing

When the EMG recording was completed, biotinylated dextran amine (BDA, 10,000 MW, Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) in phosphate-buffered saline (10% solution) was injected through a finely drawn glass capillary into four points in the left frontal motor cortex (0.1 µL per injection; stereotaxic coordinates as same as ICMS) to anterogradely label the CST originating from this area. The micropipette remained in place for 4 min after completion of the injection. Rats were sacrificed at four weeks post MCAO. The brain was processed as previously described.25 The first 10 100 µm thick sections from each 2 mm thick coronal forebrain samples were sectioned using a vibratome for the detection of BDA-positive labeling, and the remaining brain blocks were embedded with conventional paraffin for immunohistochemical staining. The cervical cords (C4–7) were longitudinally sectioned using the vibratome method.

To detect the BDA-positive CST axons and fibers, the brain coronal sections and spinal cord longitudinal sections were incubated with avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) at 4°C for 48 h, and the BDA labeling was visualized with 3,3ʹ-diaminobenzidine (DAB)-nickel (Vector). The BDA-positive fibers in the pyramidal tract at the medulla level ipsilateral to the injection site were analyzed and averaged on three consecutive coronal sections for each animal, and the number and length of BDA-positive CST axons in the stroke-impaired side of the ventral gray matter were measured on three consecutive sections of the cervical cord for each animal using a plug-in NeuroJ in the NIH image software (ImageJ).

Organotypic brain slice culture

Coronal brain slices at 250 micrometer (µm) thickness were sectioned from the post-natal day 0 (P0) rat brain by means of a vibratome. Briefly, rat pups were anesthetized and decapitated on P0. The brain was removed, and the cerebellum dissected with a razor to ensure a flat side to mount for slicing. The brain was mounted into a Compresstome VF-300 vibrating microtome (Precisionary Instruments, Inc., Greenville, NC), and sliced in ice cold HBSS at a thickness of 250 µm. Slices were discarded until the corpus callosum was thick enough to hold the hemispheres together. Each usable slice was transferred to 0.4 µm, 30 mm diameter, hydrophilic PTFE Millicell Cell Culture Inserts (Product code: PICM03050, Merck Millipore Ltd., Cork, Ireland) in a 6-well plate. Slices were incubated in medium containing 50% DMEM, 25% FBS, and 25% HBSS, supplemented with antibiotics for two days. They were then switched into Neurobasal medium with B-27 supplement, Glutamax, and antibiotics (all from Life Technologies), and the treatments were introduced at this time point. Groups of non-treatment or exosome treatment (at a concentration of 1 × 1010 particles/ml) are: no exosomes; control MSC exosomes; miR-17-92 cluster enriched MSC exosomes; the inhibitors of phosphatase and tensin homolog on chromosome 10 (PTEN)-controlled signal pathway: 2-(4-Morpholinyl)-8-phenyl-4H-1-benzopyran-4-one (PI3K inhibitor, LY294002, 20 µM, CAS #: 154447-36-6-Calbiochem, Sigma-Aldrich, Inc., St. Louis, MO) or 23,27-Epoxy-3H-pyrido[2,1-c][1,4]oxaazacyclohentriacontine (mTOR inhibitor, rapamycin, 200 nM, CAS #: 53123-88-9, Sigma-Aldrich, Inc., St. Louis, MO) along with the miR-17-92 cluster enriched MSC exosomes, respectively. The media were changed every other day thereafter. Double immunofluorescent staining was performed to identify myelin and axonal processes in the corpus callosum after an additional 14 days in culture, respectively.

Histochemistry and immunohistochemistry

To investigate the myelin density and neurite outgrowth in the ischemic boundary zone (IBZ) area, histochemistry staining and immunostaining were performed on the rat brain sections according to the manufacturer's protocol. Luxol fast blue (LFB) staining (Newcomer Supply Inc., Part # 12218B, Middleton, WI) was employed to indicate the myelin in the central nervous system,26 and an antibody against the growth-associated protein 43 (GAP-43, Cat # ab16053, 1:1000, Abcam, Cambridge, MA) was employed to identify the motile ‘growth cones” that form the tips of elongating axons.

Immunostaining for the organotypic brain slices was performed using the following protocol27: The slices were fixed with 4% formaldehyde for 1 h after two weeks of culture, then the cultures with membrane attached were excised from the insert and processed to the permeabilization step by incubating in 1% Triton X-100-contained PBS at 4°C overnight. After this, the slices were immersed in 20% bovine serum albumin with 0.1% Triton X-100-contained PBS for 1 h at room temperature and then antibody incubation was performed. The primary antibodies used were anti-neurofilament marker (pan axonal, clone SMI 312, Cat # 837902, 1:1500, Biolegend, San Diego, CA) and anti-myelin basic protein (MBP, cat # ab980, 1:1000, EMD Millipore, Temecula, CA), which were made up in 1% normal goat serum with 0.1% TritonX-100 in PBS and incubated four days at 4°C followed by incubation in species-appropriate secondary antibody (1:500, respectively) for another two days at 4°C.

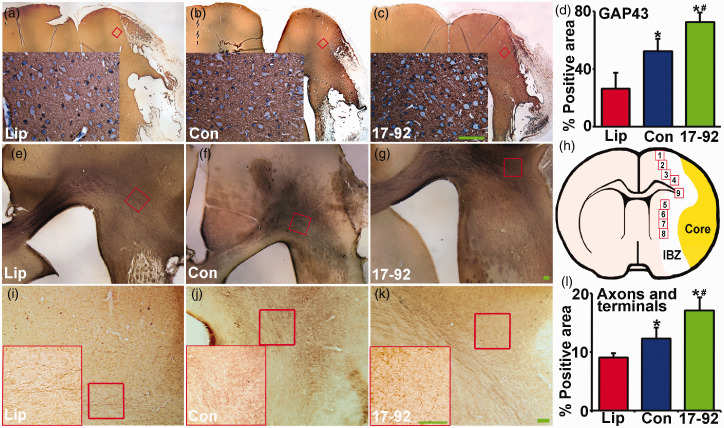

For analysis of the LFB histochemistry staining and GAP-43 immunostaining, positive staining within nine areas (four from the cortex, four from the striatum and one from the corpus callosum, see Figure 3(h)) were randomly selected along the IBZ in these groups, and were digitized under a 40× objective (BX40; Olympus Optical) using a 3-CCD color video camera (DXC-970MD, Sony) interfaced with the MCID™ software (Imaging Research Inc., St. Catharines, Ontario, Canada),28 and the area percentage of positive staining signals within the IBZ was analyzed based on an average of three histology slides (8 µm thick, every 10 slide interval) from the standard block of each animal. For the analysis of axon-myelin remodeling in the organotypic cultured brain slices, the area percentage of identified myelin and axonal-positive stained processes within the corpus callosum were analyzed, based on an average of three cultured slides per group and five random areas for each slice.

Figure 3.

MiR-17-92 enriched exosomes increase neural plasticity in the IBZ. The immunochemistry of growth-associated protein 43 (GAP-43, a–d, associated with neural plasticity) and BDA-labeled neuronal fibers (e–g, i–l) in the IBZ show the neural plasticity was significantly increased after MSC exosome treatment, and miR-17-92 enriched exosome treatment further enhanced the increase. (h) is a schematic diagram which indicates the nine areas selected for GAP-43 staining analysis. The locations of the representative images are outlined in the lower power images. Scale bar: 100 µm. Lip: liposome treatment, Con: control MSC exosome treatment, and 17-92: miR-17-92 cluster enriched MSC exosome treatment. *P < 0.05 vs. liposome treatment; #P < 0.05 vs. control MSC exosome treatment, respectively. Mean ± SD, data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA and Tukey's test for post hoc analysis, n = 10/group.

Statistical analysis

Data were summarized and presented using mean ± standard deviation (SD). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for single factor and two-way ANOVA for multiple factors were employed, and Tukey's test for post hoc analysis was used for subgroup analysis on electrophysiological response, neural plasticity and myelination, as well as for contralesional axonal sprouting. The Global test using the generalized estimating equation (GEE) was employed to evaluate the exosome treatment effects influenced by miR-17-92 cluster enrichment on functional recovery29 at day 28 after stroke. The pairwise treatment group compassion or miR-17-92 effect on individual functional test was performed if the overall global test was significant at 0.05 level. Otherwise, analysis will be considered as exploratory. With 10 rats per group and 2 groups for testing the exosome effect, considering two-sided test and two-sample t-test, we have 80% power to detect the effect size 1.325 using nQuery. Pearson's correlation coefficient was calculated to report the correlations. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS software (version 9.2; SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

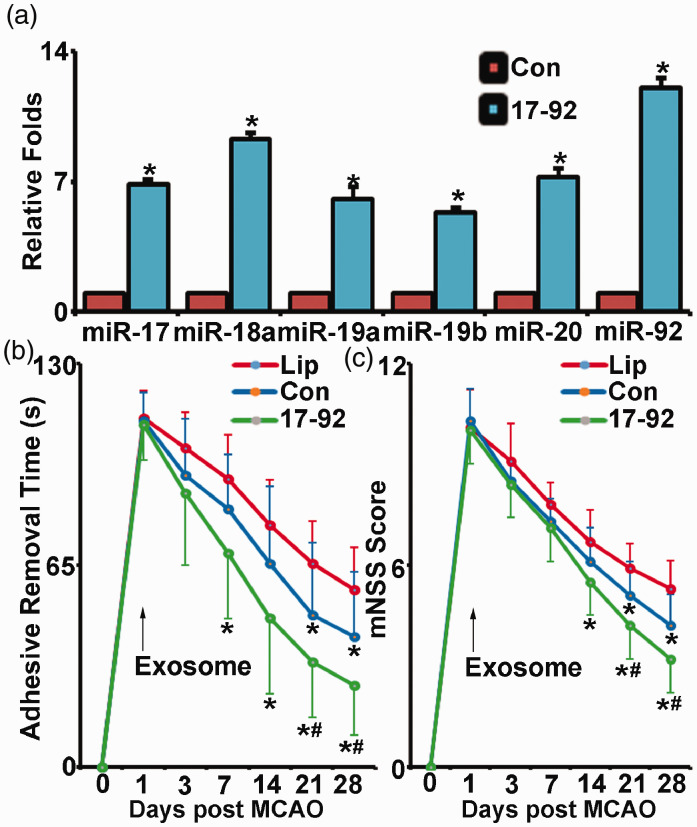

MiR-17-92 cluster enriched MSC exosomes improve functional recovery of rats subjected to MCAO

To overexpress the miR-17-92 cluster levels, MSCs were infected with lentiviruses made from a lentivector with a pre-miRNA-17-92 cluster construct. Real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis with TaqMan miRNA assay kit revealed that levels of individual members of the miR-17-92 cluster in exosomes harvested from miR-17-92 overexpressed MSCs were significantly increased compared to those in the exosomes harvested from control lentivirus infected MSCs, respectively (Figure 1(a)).

Figure 1.

MiR-17-92 cluster enriched MSC exosomes improve functional recovery of rats subjected to MCAO. Compared with exosomes from control lentivirus-infected MSCs, the miR-17-92 cluster levels are enriched in the exosomes from MSCs infected with the lentivirus constructed with miR-17-92 cluster (a). The adhesive-removal test (b) and modified neurological severity score (c) show that compared with liposome treatment (Lip), control MSC exosome (Con) and miR-17-92 cluster enriched MSC exosome (17-92) treatment significantly improved functional recovery after MCAO, and the miR-17-92 cluster enriched exosome treatment significantly further improved functional recovery compared with control MSC exosome treatment. *P < 0.05 vs. Con in A or vs. liposome treatment in B, C; #P < 0.05 vs. control lentivirus MSC exosome treatment, respectively. Mean ± SD, data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA and Tukey's test for post hoc analysis, n = 3/group in A and n = 10/group in B, C.

We then employed these miR-17-92 cluster enriched MSC exosomes to treat rats subjected to MCAO. Since unilateral brain damage induced by MCAO results in deficits of symmetry,30 we performed tests of asymmetry, e.g. adhesive removal test and mNSS test, to determine the recovery of motor function post stroke.31 Animal mortality in all groups of stroke rats was similar and relatively low (<5%). If an animal dies, or is deteriorating and not capable of taking the functional tests, the worst scores will be assigned. The Global test showed significant functional recovery at day 21 on both exosome treatment groups, compared to controls and those treatment effects sustained to day 28 after MACO. In addition, both exosome treatment groups exhibited significant reduction of the time-to-remove the adhesive tabs in the adhesive removal test (Figure 1(b)) and achieved a reduced score (the lower the score, the better the outcome) of mNSS test (Figure 1(c)), respectively. For the adhesive removal test, significant improvement was evident from 7 days and 21 days after MCAO in the Ex-miR-17-92+ and the Ex-Con treatment groups, respectively. Significant improvements of score reduction of mNSS test were detected starting at 14 days and 21 days after MCAO in the Ex-miR-17-92+ and Ex-Con treatment groups, respectively. Compared with the Ex-Con, the Ex-miR-17-92+ treatment significantly increased functional improvement, indicated by adhesive removal test and mNSS test results (P < 0.05 after day 21, Figure 1(b) and (c)). The data indicate that in addition to the functional recovery improvement brought by control MSC exosome treatment after MCAO, the miR-17-92 cluster enriched exosome treatment significantly further improved motor functional recovery post stroke, which is consistent with our prior report.11

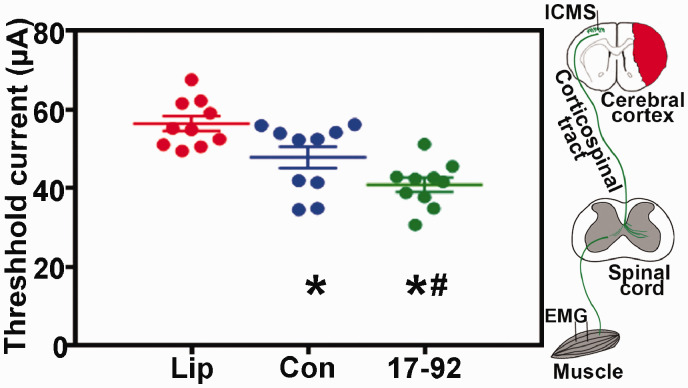

MiR-17-92 enriched exosomes improve electrophysiological response

To demonstrate the functional establishment of neuronal innervation from the cortex to the stroke-impaired forelimb, we performed ICMS on the contralateral motor cortices, and EMG recordings were obtained for active responses in the wrist flexor muscles of the stroke impaired forelimb in control and the exosome-treated groups at 21 days post-stroke. Our data (Figure 2) show that compared with control liposome treatment, MSC exosome treatment significantly decreased the lowest threshold value of ICMS that evoked impaired forelimb movement, and miR-17-92 enriched exosomes further decreased this value, respectively, which suggest that enriching the miR-17-92 cluster in MSC-derived exosomes augments the therapeutic effects of MSC exosomes on neuronal innervation.

Figure 2.

MiR-17-92 enriched exosomes improve electrophysiological response. MSC exosome treatment significantly decreased the lowest threshold value of ICMS that evoked impaired forelimb movement, and miR-17-92 enriched exosomes further decreased this value. Lip: liposome treatment, Con: control MSC exosome treatment, and 17-92: miR-17-92 cluster enriched MSC exosome treatment. *P < 0.05 vs. liposome treatment; #P < 0.05 vs. control MSC exosome treatment, respectively. Mean ± SD, data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA and Tukey's test for post hoc analysis, n = 10/group.

MiR-17-92 enriched exosomes increase neural plasticity in the IBZ

GAP-43 is a growth cone protein which is expressed at high levels in neuronal growth cones during development32 and axonal outgrowth.33 In patients, axonal sprouting has been identified in peri-lesional tissue after stroke using GAP-43 expression.34 We thereby performed immunohistostaining of GAP-43 in the rat brain sections at day 28 post MCAO (Figure 3(a) to (c)), and the data (Figure 3(d)) show that neuronal plasticity indicated by the level of GAP-43 immunoreactivity was significantly increased after MSC exosome treatment, and miR-17-92 enriched exosome treatment further enhanced GAP-43 immunoreactivity (P < 0.05, respectively).

Transcallosal axons of the pyramidal neurons in rats subjected to MCAO were also anterogradely labeled with BDA in order to evaluate the inter-hemispheric axonal plasticity. Quantitative data of the BDA labeled axonal density in the caudal forelimb area of the ipsilateral lesion are shown as percentage of proportional areas (Figure 3(e) to (g) and (i) to (l)). Intracortical axonal density was significantly increased after MSC exosome treatment compared with control liposome treatment at day 28 after MCAO (Figure 3(l)). MiR-17-92 enriched exosome treatment significantly increased the cortical axonal density at day 28 after MCAO compared with control MSC exosome treatment (Figure 3(l), P < 0.05, respectively). The above data suggest that exosomal enriched miR-17-92 cluster promotes axonal plasticity after stroke.

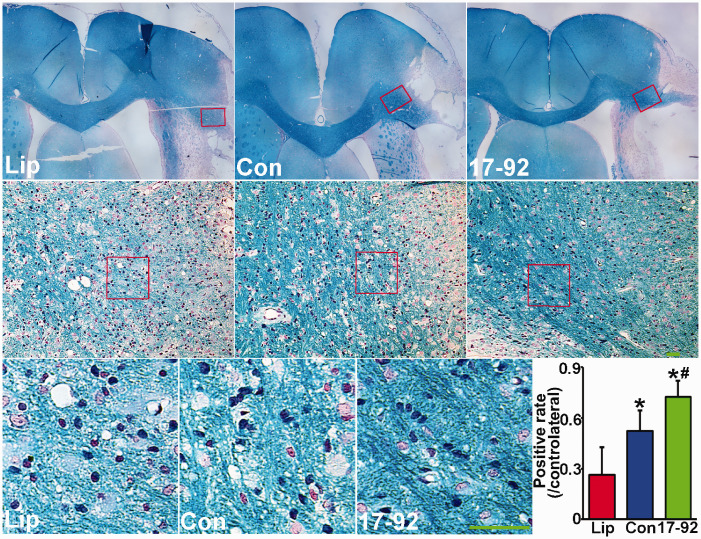

MiR-17-92 enriched exosomes increase myelination in the IBZ

Myelin loss is present post stroke,35 and LFB is commonly used to stain myelin and is often employed to observe demyelination in the central nervous system (CNS) under light microscopy.36 Our LFB stain data show that compared to control liposome treatment, the positive stained myelin density in the IBZ area was significantly increased after MSC exosome treatment, and miR-17-92 enriched exosome treatment further enhanced the myelin density at 28 days post stroke (Figure 4). These data suggest that enriched exosomal miR-17-92 cluster members foster the MSC exosome increased myelination after stroke which may contribute to the enhanced neuronal circuit function.

Figure 4.

MiR-17-92 enriched exosomes increase myelination in the IBZ. Luxol fast blue stain shows the myelin density was significantly increased after MSC exosome treatment, and miR-17-92 enriched exosome treatment further enhanced the myelin density. The anatomical locations of the representative images are outlined in the lower power images. Scale bar: 100 µm. Lip: liposome treatment, Con: control MSC exosome treatment, and 17-92: miR-17-92 cluster enriched MSC exosome treatment. *P < 0.05 vs. liposome treatment; #P < 0.05 vs. control MSC exosome treatment, respectively. Mean ± SD, data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA and Tukey's test for post hoc analysis, n = 10/group.

MiR-17-92 enriched exosomes increase BDA-labeled contralesional axonal sprouting into the denervated spinal cord

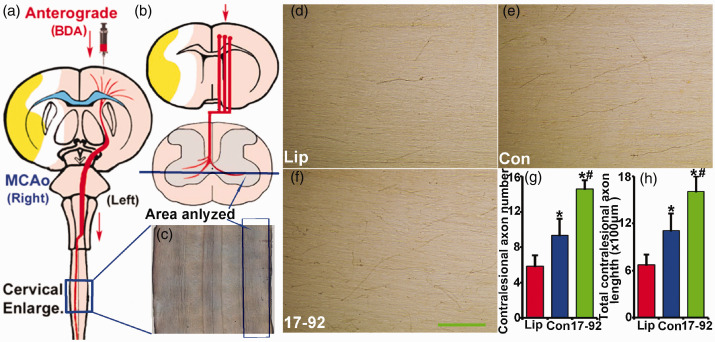

The CST axons provide the primary anatomical component for normal motor control, and behavioral recovery after stroke. To verify the enhanced CST axonal remodeling in the denervated spinal cord, we longitudinally sectioned the cervical cords (C4–7, Figure 5(a) to (c)) and measured BDA-positive CST axons in the stroke-impaired side of the ventral gray matter (Figure 5(d) to (f)). The data show that the number and total length of contralesional axon sprouting into the denervated spinal cord were significantly increased after MSC exosome treatment, and miR-17-92 enriched MSC exosome treatment further enhanced this increase, respectively (Figure 5(g) and (h), P < 0.05, respectively). These data indicate that in addition to augmenting the neuronal remodeling in the CNS, treatment with miR-17-92 cluster enriched MSC exosomes also enhances the CST axonal remodeling in the denervated spinal cord.

Figure 5.

MiR-17-92 enriched exosomes increase BDA-labeled contralesional axonal sprouting into the denervated spinal cord. (a–b) show where the BDA was injected and how the longitudinally sectioned cervical cords (C4–7) were prepared, and (c) is a representative lower power image to show the anatomical site from where the images were taken for analysis. BDA-labeled axon staining shows the contralesional axon number (g) and total contralesional axon length (h) sprouting into the denervated spinal cord were significantly increased after MSC exosome treatment, and miR-17-92 enriched exosome treatment further enhanced this increase, respectively (d–g). Scale bar: 100 µm. Lip: liposome treatment, Con: control MSC exosome treatment, and 17-92: miR-17-92 cluster enriched MSC exosome treatment. *P < 0.05 vs. liposome treatment; #P < 0.05 vs. control MSC exosome treatment, respectively. Mean ± SD, data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA and Tukey's test for post hoc analysis, n = 10/group.

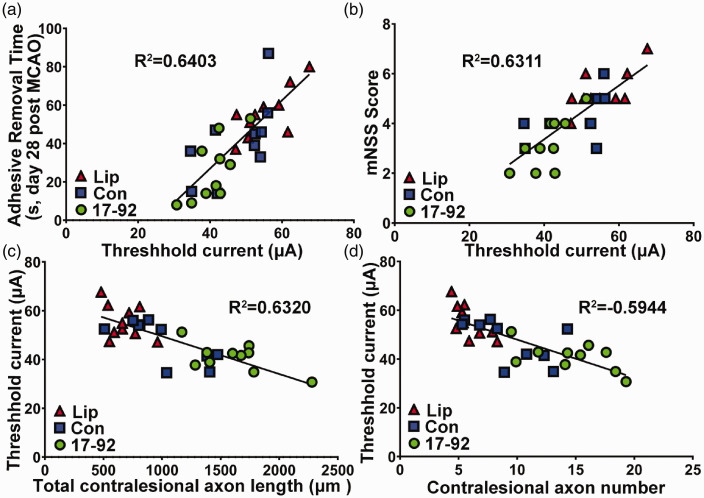

CST axonal remodeling highly correlates with electrophysiological response and behavioral outcome after stroke

To test whether contralesional CST axonal remodeling sprouting into the denervated spinal cord functionally contributes to electrophysiological response, and the latter subsequently contributes to neurological outcome after stroke, we examined the correlation of behavioral outcome with the ICMS-EMG electrophysiological response, and the correlation of ICMS-EMG data to the relative total number and total length of midline-crossing CST axons in the denervated side of the cervical cord 28 days after MCAO. The data indicate that the motor performance of the stroke-impaired forelimb assessed with the adhesive removal test and the mNSS test were highly correlated with ICMS-EMG electrophysiological response (Figure 6(a) and (b), R2 = 0.6403 and R2 = 0.6311, P < 0.01 respectively), while the ICMS-EMG electrophysiological response was highly correlated with CST axons originating from the contralesional cortex (Figure 6(c) and (d), R2 = 0.6320 and R2 = 0.5944, P < 0.01 respectively).

Figure 6.

CST axonal remodeling highly correlates with electrophysiological response and behavioral outcome after stroke. The motor performance of the stroke-impaired forelimb assessed with the adhesive removal test (a, P < 0.01) and the mNSS test (b, P < 0.01) were highly correlated with ICMS-EMG electrophysiological response, while the ICMS-EMG electrophysiological responses were highly correlated with CST axons originating from the contralesional cortex on the total length (c, P < 0.01) and total number (d, P < 0.01). Lip: liposome treatment, Con: control MSC exosome treatment, and 17-92: miR-17-92 cluster enriched MSC exosome treatment.

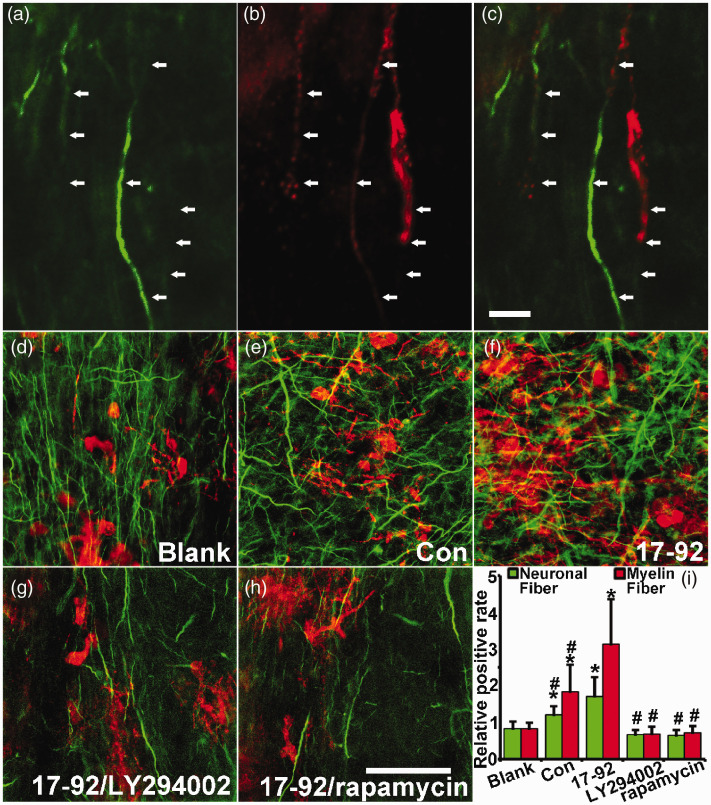

MSC exosomes with elevated miR-17-92 cluster increase neurite outgrowth and myelination which are mediated by the PTEN/PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway

To further investigate the enhanced effect of miR-17-92 cluster enriched MSC exosomes on axon-myelin remodeling, as well as to investigate whether the miR-17-92 cluster targeted PTEN/PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway mediates these effects, we employed an ex vivo rat organotypic brain slice culture model.37 Our data show that most of the MBP+ fibers wrap around the axons (Figure 7(a) to (c)) and compared to control MSC exosome treatment, miR-17-92 cluster enriched MSC exosome treatment significantly increases the MBP+ myelin and NFH+ processes within the area of the corpus callosum in the cultured brain slices. Treatment with the PI3K inhibitor (LY294002) or the mTOR inhibitor (rapamycin) significantly reduced the increase in MBP+ myelin and NFH+ processes induced by the miR-17-92 cluster enriched MSC exosomes (Figure 7(d) to (i)). These data suggest that exosomes with elevated miR-17-92 cluster enhance axonal outgrowth and myelination via the PTEN/PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway which is targeted by the miR-17-92 cluster.

Figure 7.

MSC exosomes with elevated miR-17-92 cluster enhance neurite outgrowth and myelination which are mediated by the PTEN/PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway. Double immunofluorescent staining was performed to identify MBP+ myelin and NFH+ axonal and dendritic processes in the corpus callosum at 14 days of ex vivo cultured rat organotypic brain slices. (a–c) show the typical MBP positive axons by the double staining. Respectively, the positive staining of MBP+ myelin fiber (red) and NFH+ processes (green) within the unit area (normalized to blank group) of the corpus callosum was significantly increased after MSC exosome treatment, and compared to control MSC exosomes, miR-17-92 cluster enriched MSC exosomes significantly increased the relative amounts of neuronal fibers and myelin fibers (d–f, i). Treatment with the PI3K inhibitor (LY294002) or mTOR inhibitor (rapamycin) significantly reduced MBP+ myelin and NFH+ fiber induced by the miR-17-92 cluster enriched MSC exosomes (g–i), respectively. Scale bar: 20 µm in a–c, 100 µm in d–h. *P < 0.05 vs. non-treated blank control; #P < 0.05 vs. miR-17-92 enriched exosome treatment, respectively. Mean ± SD, data were analyzed using two-way ANOVA and Tukey's test for post hoc analysis, n = 3/group.

Discussion

MiR-17-92 cluster members orchestrate neural developmental processes.38 Our previous studies have determined that the miR-17-92 cluster within the MSC exosomes enhances axonal growth of in vitro cultured embryonic cortical neurons,39 and subsequent in vivo studies demonstrated that miR-17-92 cluster elevated MSC exosomes increase neural remodeling, including neurogenesis, oligodendrogenesis, and neurite plasticity, and thereby augment the improvement of neurological outcome from stroke compared to the therapeutic benefits mediated by control MSC exosomes. In the present studies, we demonstrate that by overexpressing miR-17-92 cluster in the MSCs using a lentiviral-mediated system, the miR-17-92 cluster individual member levels in the MSC-derived exosomes are increased, and the miR-17-92 cluster elevated exosomes harvested from the miR-17-92 cluster overexpressing MSCs significantly improve the rat neurobiological functional recovery post stroke compared to the rats treated with control MSC exosomes. By employing a combination of ICMS, EMG recording, anterograde BDA tracing approaches to functionally and morphologically assess the neuronal remodeling after stroke in rats, we found that miR-17-92 cluster tailored MSC exosomes promote axonal outgrowth, increase the myelin density as well as subsequent cortical plasticity-EMG interface should read, and then enhance functional recovery post stroke. Although volumes of cerebral infarction are not altered by the MSC and MSC exosome treatment4,40,41 initiated 24 h after stroke, and cell-based as well as exosome treatment promote neuroplasticity and functional recovery, we cannot exclude the possibility that treatment with miR-17-92 enriched MSC exosomes at 24 h post stroke also evokes some neuroprotective benefits. Thus, later time point treatment studies are warranted to demonstrate that miR-17-92 exosome enhanced chronic axon-myelin remodeling solely rather than an aspect of neuroprotection at 24 h post stroke fully accounts for the neurological recovery.

As the long axons of the cortical pyramidal neurons extending to the spinal cord and connecting with the spinal motor neurons directly or indirectly, the CST is the major descending pathway connecting brain and spinal cord in mammals and forms the neuroanatomical basis for brain-controlled voluntary movements of the peripheral muscles.13 The CST damage induced by stroke commonly results in motor disability, and the severity of damage determines the extent of functional disability.42 The potential for functional recovery is highly dependent on the CST integrity within the ischemic damaged cerebral hemisphere.14 Via terminal sprouting, the intact cortices-derived CST axons extend their innervating arbors into the denervated spinal area, to rewire the spinal motor neurons after CNS injury.43 We and others have demonstrated that CST fibers originating from the contralesional hemisphere sprout into the de-afferent spinal cord in adult rodents following stroke and treatments, and the axonal remodeling highly correlates with behavioral outcome.44–46 In the present studies, we investigate the CST neuronal remodeling after stroke in rats and demonstrate that the improvement in electrophysiological response associated with functional recovery is enhanced by miR-17-92 cluster enriched MSC exosome treatment. Meanwhile, the connection of contralesional hemisphere originating CST axon fibers to the ipsilateral spinal cord as well as the rewiring of spinal motor neurons which control the forelimb muscle contraction are significantly increased by miR-17-92 cluster enriched MSC exosomes. Here, we found that the neural plasticity primarily takes place within stroke-affected neural pathways, such as the CST, and that they are remodeled by miR-17-92 enriched exosomes. However, the intact neural pathways in the spinal cord may also undergo remodeling, which may contribute to functional recovery. As complementary approaches, the involvement of other descending pathways, such as the corticorubral tract, corticobulbar, reticulospinal, vestibulospinal, and tectospinal tracts warrant investigation.25,47

Corticospinal excitability augmented by neuronal plasticity can be evaluated using ICMS evoked EMG,48 and EMG responses are widely employed in stroke patients to assess movement capabilities.49,50 During recovery from stroke, both the CST axons originating from ischemic and intact cortices may rewire the spinal motor neurons.16 Functional magnetic resonance imaging studies have demonstrated that stroke survivors with good recovery show increased cortical neuronal activation in the peri-infarct rim51; however, the larger infarct brings the induction of a cortical activation shift into the contralesional hemisphere.52 In the present studies, since the MCAO model we employed induces a large lesion (approaching 40% of hemisphere) in the cerebral cortex, corpus callosum, striatum, basal ganglia, and thalamus,53,54 we applied a stimulating current on the contralesional motor cortical neurons. Our previous study demonstrated that in sham animals, threshold values evoking ipsilateral movements were much higher (Mean range, 68.5 µA to 87.0 µA) than those required to evoke contralateral movements (Mean range 11.5 µA to 17.5 µA). Even employing currents up to 100 µA at some stimulation points failed to evoke an ipsilateral response. The ipsilateral forelimb evoked thresholds were found to be significantly reduced after experimental stroke (Mean range, 38.5 µA to 64.9 µA, P < 0.001) which was consistent with our current data.25 Our ICMS-EMG data map impaired limb movement to the contralesional neurons, and reveal that the CST plasticity remodeling in the contralesional motor cortex of rats after MCAO is further increased by the miR-17-92 cluster enriched MSC exosome treatment. However, we do not exclude the possibility that the miR-17-92 cluster enriched MSC exosome treatment also enhances the CST remodeling originating in the ipsilateral cortex, which also may contribute to the functional recovery from stroke in the rats.

Although the injured CNS presents a highly inhibitory environment for axonal regeneration, the adult central nervous system can induce cellular responses needed for neurite growth and synaptic formation.55 Our previous studies have shown that MSC and MSC exosome treatment after stroke stimulates the brain parenchymal cells which facilitate axonal sprouting and neuronal remodeling.6,56 The present studies then found that miR-17-92 cluster enriched MSC exosomes further enhance this axonal sprouting and neuronal remodeling. However, this miR-17-92 cluster enriched MSC exosome-mediated augmentation of neuronal plasticity is likely not solely responsible for the promotion of functional recovery after stroke. Nerve fibers in the central nervous system are encased in layers of myelin, and the development of myelin sheaths is associated with the coordination of voluntary movements.57 Exosomes with elevated miR-17-92 cluster increase the proliferation of oligodendrocyte precursor cells (OPCs),11 and in the present studies, we further found that the miR-17-92 cluster-elevated MSC exosomes also enhance the differentiation of OPCs into oligodendrocytes which provide myelin to insulate the newly generated and extended axons. This enhancement of axon-myelin remodeling may contribute to motor electrophysiological and functional recovery after stroke mediated by the miR-17-92 cluster enriched MSC exosome treatment.

Neuronal signals control the transformation of OPCs into myelin-forming oligodendrocytes.58 Neurotrophic factors released by neurons, e.g. neuregulin-1, are secreted in the brain and spinal cord and influence all stages of oligodendrocyte lineage cells, from proliferation through myelination.59 We have previously shown that treatment of stroke with miR-17-92 enriched MSC exosomes significantly reduces PTEN (a key repressor of the PI3K/mTOR pathway) in the peri-infarct region post stroke,11 which subsequently activates neuronal Akt and mTOR, leading to inactivation of GSK-3β60,61 and then facilitates axonal outgrowth.62,63 In addition, activation of the Akt signal pathway regulates myelination of axons by oligodendrocytes.64 PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling regulates production of the large amounts of myelin membrane necessary for axon ensheathment, since the expression of genes necessary for cholesterol synthesis and cholesterol formation is promoted by mTOR.65 In the present studies, as a proof of concept study, we ex vivo cultured the post-natal brain slice under non-ischemic condition to investigate the effect of miR-17-92 enriched exosomes on axon-myelin remodeling, and to identify whether the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway is involved. We demonstrated that the enriched miR-17-92 cluster in the MSC exosomes increases axonal outgrowth and myelination may in part be attributed to the activation of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signal pathway. However, the potential targets of the individual members of the miR-17-92 cluster are vast, and the signal pathways controlled by the miR-17-92-targeted proteins are many, and these targets may even be more complex under ischemic conditions. Therefore, although we identified the potential involvement of PTEN/PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway, we do not exclude the likelihood that other proteins targeted by miR-17-92 cluster participate in the enhancement of axon-myelin remodeling and motor electrophysiological recovery after stroke brought on by miR-17-92 cluster enriched MSC exosomes. Among the many targeted proteins of the miR-17-92 family are the small Rho GTPases, via the ROCK-PTEN signal pathway, which contribute to the remodeling of growth-cone-like structures and axonal outgrowth,62 as well as FRZB, a novel target of the miR-17-92 cluster, which inhibits the Wnt/β-catenin pathway66 that has recently emerged as a key regulator of myelin gene expression and myelination.67,68 To further confirm that the miR-17-92 cluster enriched exosomes promote axon-myelin remodeling through the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway, experiments employing specific knock-in PTEN (overexpressing PTEN in neurons and/or oligodendrocytes with specific promotor controlled) as well as specific knock-down/knock-out of the downstream signal effectors, e.g. PI3K, Akt or mTOR, in the neurons and oligodendrocytes with specific promotor guided CRISPR/Cas9 technology are warranted to be performed in vivo or ex vivo.

Conclusion

Our studies suggest that the miR-17-92 cluster enriched MSC exosome treatment of stroke in the rat increases CST neuronal plasticity and axonal extension as well as axonal myelination, which, in concert, contribute to the enhancement of electrophysiological response and neurological functional recovery after stroke. Activation of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway mediated by the miR-17-92 enriched exosome downregulating PTEN likely plays a role in this post stroke recovery process.

Acknowledgements

We thank Xia Sang for animal care, and Julie Landschoot-Ward, Qing’e Lu and Sue Santra for technical assistance on histology.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Research reported in this publication was supported by National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) of the National Institutes of Health under award number RO1 NS088656 (MC). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Authors’ contributions

Experimental design: HX, ZL, ZZ and MC.

Experimental performance: HX, ZL, BB, YL, WG, XG, FW and MA.

Data Acquisition: HX, ZL, XG and FW.

Data analysis: ML.

Manuscript writing: HX and MC.

ORCID iDs

Hongqi Xin https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3172-416X

Zhongwu Liu https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8571-8112

References

- 1.Long Q, Upadhya D, Hattiangady B, et al. Intranasal MSC-derived A1-exosomes ease inflammation, and prevent abnormal neurogenesis and memory dysfunction after status epilepticus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017; 114: E3536–E3545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Drommelschmidt K, Serdar M, Bendix I, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles ameliorate inflammation-induced preterm brain injury. Brain Behav Immun 2017; 60: 220–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang ZG, Buller B, Chopp M.Exosomes – beyond stem cells for restorative therapy in stroke and neurological injury. Nat Rev Neurol 2019; 15: 193–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xin H, Li Y, Cui Y, et al. Systemic administration of exosomes released from mesenchymal stromal cells promote functional recovery and neurovascular plasticity after stroke in rats. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2013; 33: 1711–1715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Doeppner TR, Herz J, Gorgens A, et al. Extracellular vesicles improve post-stroke neuroregeneration and prevent postischemic immunosuppression. Stem Cells Transl Med 2015; 4: 1131–1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xin H, Li Y, Chopp M.Exosomes/miRNAs as mediating cell-based therapy of stroke. Front Cell Neurosci 2014; 8: 377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang J, Zhang X, Chen X, et al. Exosome mediated delivery of miR-124 promotes neurogenesis after ischemia. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids 2017; 7: 278–287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chopp M, Zhang ZG.Emerging potential of exosomes and noncoding microRNAs for the treatment of neurological injury/diseases. Exp Opin Emerg Drugs 2015; 20: 523–526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shen H, Yao X, Li H, et al. Role of exosomes derived from miR-133b modified MSCs in an experimental rat model of intracerebral hemorrhage. J Mol Neurosci 2018; 64: 421–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xin H, Wang F, Li Y, et al. Secondary release of exosomes from astrocytes contributes to the increase in neural plasticity and improvement of functional recovery after stroke in rats treated with exosomes harvested from MicroRNA 133b-overexpressing multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. Cell Transplant 2017; 26: 243–257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xin H, Katakowski M, Wang F, et al. MicroRNA cluster miR-17-92 cluster in exosomes enhance neuroplasticity and functional recovery after stroke in rats. Stroke 2017; 48: 747–753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Langhorne P, Coupar F, Pollock A.Motor recovery after stroke: a systematic review. Lancet Neurol 2009; 8: 741–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heffner RS, Masterton RB.The role of the corticospinal tract in the evolution of human digital dexterity. Brain Behav Evolut 1983; 23: 165–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stinear CM, Barber PA, Smale PR, et al. Functional potential in chronic stroke patients depends on corticospinal tract integrity. Brain 2007; 130: 170–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schulz R, Park CH, Boudrias MH, et al. Assessing the integrity of corticospinal pathways from primary and secondary cortical motor areas after stroke. Stroke 2012; 43: 2248–2251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu Z, Zhang RL, Li Y, et al. Remodeling of the corticospinal innervation and spontaneous behavioral recovery after ischemic stroke in adult mice. Stroke 2009; 40: 2546–2551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu Z, Chopp M, Ding X, et al. Axonal remodeling of the corticospinal tract in the spinal cord contributes to voluntary motor recovery after stroke in adult mice. Stroke 2013; 44: 1951–1956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baddoo M, Hill K, Wilkinson R, et al. Characterization of mesenchymal stem cells isolated from murine bone marrow by negative selection. J Cell Biochem 2003; 89: 1235–1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meirelles Lda S, Nardi NB.Murine marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cell: isolation, in vitro expansion, and characterization. Br J Haematol 2003; 123: 702–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xin H, Li Y, Liu Z, et al. MiR-133b promotes neural plasticity and functional recovery after treatment of stroke with multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells in rats via transfer of exosome-enriched extracellular particles. Stem Cells 2013; 31: 2737–2746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garza-Licudine E, Deo D, Yu S, et al. Portable nanoparticle quantization using a resizable nanopore instrument – the IZON qNano. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc 2010; 2010: 5736–5739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li Y, Powers C, Jiang N, et al. Intact, injured, necrotic and apoptotic cells after focal cerebral ischemia in the rat. J Neurol Sci 1998; 156: 119–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang Y, Chopp M, Zhang ZG, et al. Systemic administration of cell-free exosomes generated by human bone marrow derived mesenchymal stem cells cultured under 2D and 3D conditions improves functional recovery in rats after traumatic brain injury. Neurochem Int 2017; 111: 69–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen J, Zhang C, Jiang H, et al. Atorvastatin induction of VEGF and BDNF promotes brain plasticity after stroke in mice. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2005; 25: 281–290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu Z, Li Y, Zhang X, et al. Contralesional axonal remodeling of the corticospinal system in adult rats after stroke and bone marrow stromal cell treatment. Stroke 2008; 39: 2571–2577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clasen RA, Simon GR, Ayer JP, et al. A chemical basis for the staining of myelin sheaths by luxol dye techniques; further observations. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 1967; 26: 153–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gogolla N, Galimberti I, DePaola V, et al. Staining protocol for organotypic hippocampal slice cultures. Nat Protoc 2006; 1: 2452–2456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li Y, Sharov VG, Jiang N, et al. Ultrastructural and light microscopic evidence of apoptosis after middle cerebral artery occlusion in the rat. Am J Pathol 1995; 146: 1045–1051. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lu M, Chen J, Lu D, et al. Global test statistics for treatment effect of stroke and traumatic brain injury in rats with administration of bone marrow stromal cells. J Neurosci Methods 2003; 128: 183–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li Y, Chen J, Wang L, et al. Treatment of stroke in rat with intracarotid administration of marrow stromal cells. Neurology 2001; 56: 1666–1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schaar KL, Brenneman MM, Savitz SI.Functional assessments in the rodent stroke model. Exp Transl Stroke Med 2010; 2: 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosskothen-Kuhl N, Illing RB.Gap43 transcription modulation in the adult brain depends on sensory activity and synaptic cooperation. PLoS One 2014; 9: e92624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hoffman PN.Expression of GAP-43, a rapidly transported growth-associated protein, and class II beta tubulin, a slowly transported cytoskeletal protein, are coordinated in regenerating neurons. J Neurosci 1989; 9: 893–897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ng SC, de la Monte SM, Conboy GL, et al. Cloning of human GAP-43: growth association and ischemic resurgence. Neuron 1988; 1: 133–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhou J, Zhuang J, Li J, et al. Long-term post-stroke changes include myelin loss, specific deficits in sensory and motor behaviors and complex cognitive impairment detected using active place avoidance. PLoS One 2013; 8: e57503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kluver H, Barrera E.A method for the combined staining of cells and fibers in the nervous system. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 1953; 12: 400–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Croft CL, Noble W.Preparation of organotypic brain slice cultures for the study of Alzheimer's disease. F1000Res 2018; 7: 592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bian S, Hong J, Li Q, et al. MicroRNA cluster miR-17-92 regulates neural stem cell expansion and transition to intermediate progenitors in the developing mouse neocortex. Cell Rep 2013; 3: 1398–1406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang Y, Chopp M, Liu XS, et al. Exosomes derived from mesenchymal stromal cells promote axonal growth of cortical neurons. Mol Neurobiol 2017; 54: 2659–2673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Steiner B, Roch M, Holtkamp N, et al. Systemically administered human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem home into peripheral organs but do not induce neuroprotective effects in the MCAo-mouse model for cerebral ischemia. Neurosci Lett 2012; 513: 25–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen J, Li Y, Wang L, et al. Therapeutic benefit of intravenous administration of bone marrow stromal cells after cerebral ischemia in rats. Stroke 2001; 32: 1005–1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alawieh A, Zhao J, Feng W.Factors affecting post-stroke motor recovery: implications on neurotherapy after brain injury. Behav Brain Res 2018; 340: 94–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tuszynski MH, Steward O.Concepts and methods for the study of axonal regeneration in the CNS. Neuron 2012; 74: 777–791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu Z, Li Y, Qu R, et al. Axonal sprouting into the denervated spinal cord and synaptic and postsynaptic protein expression in the spinal cord after transplantation of bone marrow stromal cell in stroke rats. Brain Res 2007; 1149: 172–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen P, Goldberg DE, Kolb B, et al. Inosine induces axonal rewiring and improves behavioral outcome after stroke. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2002; 99: 9031–9036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wiessner C, Bareyre FM, Allegrini PR, et al. Anti-nogo-A antibody infusion 24 hours after experimental stroke improved behavioral outcome and corticospinal plasticity in normotensive and spontaneously hypertensive rats. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2003; 23: 154–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu Z, Li Y, Zhang L, et al. Subacute intranasal administration of tissue plasminogen activator increases functional recovery and axonal remodeling after stroke in rats. Neurobiol Dis 2012; 45: 804–809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ngomo S, Leonard G, Moffet H, et al. Comparison of transcranial magnetic stimulation measures obtained at rest and under active conditions and their reliability. J Neurosci Methods 2012; 205: 65–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mima T, Toma K, Koshy B, et al. Coherence between cortical and muscular activities after subcortical stroke. Stroke 2001; 32: 2597–2601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Woldag H, Hummelsheim H.Evidence-based physiotherapeutic concepts for improving arm and hand function in stroke patients: a review. J Neurol 2002; 249: 518–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cramer SC, Shah R, Juranek J, et al. Activity in the peri-infarct rim in relation to recovery from stroke. Stroke 2006; 37: 111–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nair DG, Hutchinson S, Fregni F, et al. Imaging correlates of motor recovery from cerebral infarction and their physiological significance in well-recovered patients. Neuroimage 2007; 34: 253–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Garcia JH, Yoshida Y, Chen H, et al. Progression from ischemic injury to infarct following middle cerebral artery occlusion in the rat. Am J Pathol 1993; 142: 623–635. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liu Z, Li Y, Zhang J, et al. Evaluation of corticospinal axon loss by fluorescent dye tracing in mice with experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Neurosci Methods 2008; 167: 191–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Carmichael ST.Cellular and molecular mechanisms of neural repair after stroke: making waves. Ann Neurol 2006; 59: 735–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chopp M, Li Y.Treatment of neural injury with marrow stromal cells. Lancet Neurol 2002; 1: 92–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stadelmann C, Timmler S, Barrantes-Freer A, et al. Myelin in the central nervous system: structure, function, and pathology. Physiol Rev 2019; 99: 1381–13431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Simons M, Nave KA.Oligodendrocytes: myelination and axonal support. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect Biol 2015; 8: a020479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fernandez PA, Tang DG, Cheng L, et al. Evidence that axon-derived neuregulin promotes oligodendrocyte survival in the developing rat optic nerve. Neuron 2000; 28: 81–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fevrier B, Raposo G.Exosomes: endosomal-derived vesicles shipping extracellular messages. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2004; 16: 415–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mathivanan S, Ji H, Simpson RJ.Exosomes: extracellular organelles important in intercellular communication. J Proteomics 2010; 73: 1907–1920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhang Y, Ueno Y, Liu XS, et al. The MicroRNA-17-92 cluster enhances axonal outgrowth in embryonic cortical neurons. J Neurosci 2013; 33: 6885–6894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Liu K, Lu Y, Lee JK, et al. PTEN deletion enhances the regenerative ability of adult corticospinal neurons. Nat Neurosci 2010; 13: 1075–1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Norrmen C, Suter U.Akt/mTOR signalling in myelination. Biochem Soc Trans 2013; 41: 944–950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mathews ES, Appel B.Cholesterol biosynthesis supports myelin gene expression and axon ensheathment through modulation of P13K/Akt/mTor signaling. J Neurosci 2016; 36: 7628–7639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Spagnuolo M, Regazzo G, De Dominici M, et al. Transcriptional activation of the miR-17-92 cluster is involved in the growth-promoting effects of MYB in human Ph-positive leukemia cells. Haematologica 2019; 104: 82–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tawk M, Makoukji J, Belle M, et al. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling is an essential and direct driver of myelin gene expression and myelinogenesis. J Neurosci 2011; 31: 3729–3742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fancy SP, Baranzini SE, Zhao C, et al. Dysregulation of the Wnt pathway inhibits timely myelination and remyelination in the mammalian CNS. Genes Develop 2009; 23: 1571–1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]