Significance Statement

Earlier case reports of patients with IgA nephropathy and inflammatory bowel disease have discussed the pathophysiologic links and described associations between the conditions and response to treatments. In this nationwide cohort study, the authors compared 3963 patients with IgA nephropathy with 19,978 matched controls, finding that patients with IgA nephropathy had increased risk of inflammatory bowel disease both before and after a confirmed IgA nephropathy diagnosis. They also found that among patients with IgA nephropathy, those with inflammatory bowel disease were more likely than those without it to progress to ESKD. Accordingly, the identification of inflammatory bowel disease in patients with IgA nephropathy may improve ESKD risk prediction. Further studies are needed to establish whether inflammatory bowel disease screening and optimized treatment can improve IgA nephropathy prognosis in patients with both conditions.

Keywords: IgA nephropathy, clinical epidemiology, end stage kidney disease, ESKD

Visual Abstract

Abstract

Background

Case reports suggest an association between inflammatory bowel disease, a chronic autoimmune condition linked to increased circulating IgA levels, and IgA nephropathy, the most common form of primary GN and a leading cause of ESKD.

Methods

In a Swedish population-based cohort study, we compared 3963 biopsy-verified IgA nephropathy patients with 19,978 matched controls between 1974 and 2011, following up participants until 2015. Inflammatory bowel disease data and ESKD status were obtained through national medical registers. We applied Cox regression to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) for future inflammatory bowel disease in IgA nephropathy and conditional logistic regression to assess risk of earlier inflammatory bowel disease in IgA nephropathy. We also explored whether inflammatory bowel disease affects development of ESKD in IgA nephropathy.

Results

During a median follow-up of 12.6 years, 196 (4.95%) patients with IgA nephropathy and 330 (1.65%) matched controls developed inflammatory bowel disease (adjusted HR, 3.29; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 2.73 to 3.96). Inflammatory bowel disease also was more common before a confirmed IgA nephropathy diagnosis. Some 103 (2.53%) IgA nephropathy patients had an earlier inflammatory bowel disease diagnosis compared with 220 (1.09%) controls (odds ratio [OR], 2.37; 95% CI, 1.87 to 3.01). Both logistic regression (OR, 2.60; 95% CI, 2.02 to 3.35) and time-varying Cox regression (HR, 1.84; 95% CI, 1.33 to 2.55) demonstrated that inflammatory bowel disease was associated with increased ESKD risk in patients with IgA nephropathy.

Conclusions

Patients with IgA nephropathy have an increased risk of inflammatory bowel disease both before and after their nephropathy diagnosis. In addition, among patients with IgA nephropathy, comorbid inflammatory bowel disease elevates the risk of progression to ESKD.

IgA nephropathy (IgAN), first described by Berger and Hinglais in 1968,1 is the most common type of primary GN worldwide.2 The clinical presentation in IgAN can vary from ARF, macrohematuria, hypertension, and significant proteinuria to asymptomatic disease detectable only through urinary abnormalities upon urinary dipstick screening.3,4 Incidence reports vary around the world. Studies imply numbers of between 15 and 40 per million people per year in Europe,3,5–8 12 per million people per year in the USA,9 and 105 per million people per year in Australia.10 However, the true incidence and prevalence are difficult to determine given that asymptomatic disease is common and biopsy routines vary between countries.11 IgAN progresses to ESKD in 15%–50% of the cases and it may also recur in donor organs post-transplantation.3–5

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is characterized by chronic or flares of inflammatory activity in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. The two most common types of IBD are Crohn disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC). Earlier studies have shown an increased risk of IgAN in patients with celiac disease,12 and case reports have long described the correlation between inflammatory activity in IBD and progression or regression of IgAN.13–17 Recent genetic studies have identified shared risk loci between IgAN and IBD, and new risk loci for IgAN. Most of these new loci were shared with other immune-mediated diseases, mainly loci associated with IBD and maintenance of the intestinal epithelial barrier and response to mucosal pathogens.18,19

To our knowledge, there have been no epidemiologic studies of the association between IgAN and IBD. However, Ambruzs et al.20 evaluated 33,713 renal biopsy specimens from Arkansas, including 83 from patients with IBD (45 CD and 38 UC). The frequency of IgAN in patients with IBD was significantly higher compared with all other native biopsy specimens from non-IBD patients: 20 of 83 (24%) versus 2734 of 33,630 (8%). Moreover, Elaziz and Fayed21 reviewed 896 patients with IBD from Cairo University Hospital and found that 218 (24.3%) developed renal affection and underwent renal biopsy 5.6±7.4 years after IBD diagnosis. Underlying IgAN was seen in 35 patients (16.1%).

We aimed to examine the association between IgAN and IBD in a Swedish population and assess whether IBD status is a risk factor for progression to ESKD.

Methods

Through the unique personal identification number assigned to all Swedish permanent residents,22 we linked data on biopsy-verified IgAN from Swedish pathology departments with three established and validated registers: the Total Population Register, the National Patient Register (NPR), and the Cause of Death Register.

Definition of IgAN and IBD

We defined IgAN as having a computerized biopsy record of IgAN (diagnosed in 1974–2011) at any of the four pathology departments that evaluate all renal biopsy specimens in Sweden (Stockholm, Gothenburg, Linköping, and Malmö/Lund). Patients were ascertained by the local computer departments that searched biopsy records for the IgAN Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine Clinical Term code D67300,23 except for in Malmö/Lund, where renal biopsy reports were reviewed manually.12 A random subset of IgAN Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine Clinical Term codes has since been manually validated by Jarrick et al.24 against patient charts and biopsy reports. They found that of 127 biopsy samples (patients) diagnosed with IgAN, 121 also had a clinically confirmed diagnosis with typical symptoms such as hematuria, hypertension, or impaired kidney function: positive predictive value (PPV) of 95% (95% confidence interval [95% CI], 92% to 99%). IgA deposits were reported in 97% of the biopsy records (n=123), mesangial hypercellularity in 76% (n=96), and C3 deposits in 89% (n=113).

IBD and ESKD diagnoses were assessed through relevant International Classification of Diseases codes in the NPR (listed in the Supplemental Appendix). The NPR, a national register maintained by the National Board of Health and Welfare in Sweden, contains data and diagnoses from all specialist medical care (hospitalizations or non–primary care outpatient visits) without any Swedish resident being lost to follow-up.25 The NPR contains both inpatient and outpatient data and validity of IBD diagnosis in the Swedish NPR is high. The PPV for having ≥2 IBD diagnoses was 93% for years 1987 and onwards, despite changing diagnostic requirements over time.26 The majority of our IBD cases were identified after 1987 and we used ≥2 IBD diagnoses in sensitivity analyses, yielding similar results as our main analyses.

Matched Reference Individuals (Controls)

The government agency Statistics Sweden identified up to five controls for each individual with IgAN. Controls, matched for age, sex, calendar year, and county of residence at the time of renal biopsy, were selected from the Total Population Register,27 a register containing data on the birth, death, family, marital status, and migration of all citizens. Through every permanent resident’s unique personal identification number, these data can be linked to medical records and other registers. There were no exclusion criteria pertaining to the control sampling except that the reference individuals were not previously diagnosed with biopsy-verified IgAN at the time of matching/renal biopsy of the index patient. Hence, our risk-set–sampled controls represent a random selection of the Swedish population including individuals with and without other chronic diseases. The same risk-set–sampled controls were used for cohort analyses comparing IgAN-exposed versus -unexposed (controls) and for conditional logistics regression.

Follow-Up

We defined the date of IgAN diagnosis as the day of the first renal biopsy confirming IgAN. Follow-up began at IgAN diagnosis and the corresponding date in the controls and ended with death, emigration, or December 31, 2015, whichever occurred first. For analyses of ESKD risk, follow-up began at the date of biopsy and ended with ESKD, death, emigration, or the administrative end of the follow-up (December 31, 2015), whichever occurred first.

In a conditional logistics regression, we examined the presence of IBD to 2011 when the last IgAN biopsy was performed, comparing patients with IgAN with controls.

Exclusion Criteria

Individuals with an IBD diagnosis before the IgAN diagnosis/corresponding date in controls were excluded in Cox regressions where the outcome was IBD, and similarly individuals with ESKD before baseline were excluded in Cox regressions for the outcome ESKD. No other exclusion criteria were used in our analyses.

Statistical Analyses

We performed Cox regressions for risk of IBD, CD, UC, and IBD-unclassified (IBD-U) in patients with IgAN internally stratified, i.e., only comparing the matching sets of one case with its five matched controls (same sex, age, and county of residence) and then calculating a summary hazard ratio (HR). Analyses were additionally adjusted for educational attainment (modeled as three levels: compulsory, upper secondary, university, plus unknown, see Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Participant Characteristics | IgAN, n (%) | General Population (Controls), n (%) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 3963 (100) | 19,978 (100) | |

| Matched variables | |||

| Sex | 0.99 | ||

| Female | 1156 (29.17) | 5830 (29.18) | |

| Male | 2807 (70.83) | 14,148 (70.82) | |

| Age | 0.99 | ||

| <18 yr | 370 (9.34) | 1866 (9.34) | |

| 18–39 yr | 1655 (41.76) | 8350 (41.80) | |

| 40–59 yr | 1367 (34.49) | 6847 (34.27) | |

| ≥60 yr | 571 (14.41) | 2915 (14.59) | |

| Calendar yr | 0.95 | ||

| Entry yr | |||

| 1974–1994 | 1056 (26.65) | 5291 (26.48) | |

| 1995–2005 | 1657 (41.81) | 8338 (41.74) | |

| 2006–2015 | 1250 (31.54) | 6349 (31.78) | |

| Unmatched variables | |||

| Follow-up | <0.001 | ||

| Mean (SD) | 13.1 yr (8.4) | 13.9 yr (8,4) | |

| Median | 11.7 yr | 12.6 yr | |

| <1 yr | 84 (2.12) | 207 (1.04) | |

| 1–4 yr | 596 (15.04) | 2619 (13.11) | |

| ≥5 yr | 3283 (82.84) | 17,152 (85.85) | |

| Educational level | 0.82 | ||

| Compulsory school, ≤9 yr | 879 (22.18) | 4301 (21.53) | |

| Upper secondary school, 1–3 yr | 1752 (44.21) | 8942 (44.76) | |

| University level | 1241 (31.31) | 6263 (31.35) | |

| Unknown | 91 (2.30) | 472 (2.36) | |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Diabetes | 301 (7.6) | 1127 (5.6) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 1413 (36.7 | 2514 (12.6) | <0.001 |

| Heart failure | 190 (4.8) | 589 (2.9) | <0.001 |

We also ran a sensitivity analysis, restricting patients with IBD to those with ≥2 IBD diagnoses in the NPR, which has been validated for IBD with a PPV of 93% (95% CI, 87 to 97).26 In addition, we ran a sensitivity analysis for IBD, restricting the controls to individuals with at least one diagnosis of any disease, i.e., having at least one entry registered in the NPR.

We restricted the follow-up of IBD to 1, 5, and 10 years in separate analyses. We also performed an analysis excluding the first year of follow-up to mitigate ascertainment bias. Incidence rates were calculated as the number of events per 1000 person-years of follow-up.

For the conditional logistics regression, we calculated odds ratios (ORs) for future IgAN diagnosis according to IBD status additionally adjusted for age (continuous birth year), sex, calendar year of inclusion, and education.

We also ran three Cox regression models on ESKD risk to compare patients with and without IBD. In the first analysis, IBD status was determined at baseline. In the second analysis, IBD was modeled as ever during follow-up (i.e., not modeled as a time-variant but positive from baseline no matter when the diagnosis was made during the follow-up. The reason for doing so was that diagnostic delay is common in both IBD and IgAN and hence an exact date of diagnosis may not represent actual exposure.). In the third analysis we performed a Cox regression treating IBD status as a time-varying exposure. These analyses were additionally adjusted for birth year, sex, calendar year, hypertension, heart failure, diabetes (definitions in Supplemental Appendix), and education. Finally, we modeled a logistic regression with the same adjustments to explore whether IBD affects the development of ESKD in IgAN.

Ethics

The study was approved by the Stockholm Ethics Review Board (January 22, 2014, approval number: 2013/2095–31/2). Because this was a strictly register-based study, the requirement of informed consent was waived by the Board.28

Results

During a median follow-up of 12.6 years, 196 (4.95%) patients with IgAN were diagnosed with IBD compared with 330 (1.65%) of the matched controls, corresponding to an adjusted HR (aHR) of 3.29 (95% CI, 2.73 to 3.96). Restricting the control group to individuals that had at least one entry in the NPR (14,081 of 20,005), the corresponding aHR was 2.96 (95% CI, 2.44 to 3.60). When restricted to patients having ≥2 records of IBD, the aHR was 2.64 (95% CI, 2.03 to 3.42). The risk was significantly increased in all subgroup analyses (male versus female, different age-groups, and calendar years) as summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

IBD in patients with IgAN

| Characteristic | IgAN with IBD (%) | Controls with IBD (%) | IR IgAN with IBD | IR Controls with IBD | aHRa | Total Number of Follow-Up Yr IgAN | Total Number of Follow-Up Yr Controls | IgAN with IBD ≥2 Diagnoses (%) | Controls with IBD ≥2 Diagnoses (%) | aHRa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 196 (4.9) | 330 (1.7) | 3.8 (3.2 to 4.3) | 1.2 (1.1 to 1.3) | 3.29 (2.73 to 3.96) | 51.883 | 277.103 | 91 (2.3) | 184 (0.9) | 2.64 (2.03 to 3.42) |

| Sex | ||||||||||

| Female | 59 (5.1) | 112 (1.9) | 3.8 (2.8 to 4.8) | 1.4 (1.1 to 1.6) | 2.84 (2.04 to 3.95) | 15.588 | 81.210 | 26 (2.2) | 63 (1.1) | 2.14 (1.34 to 3.43) |

| Male | 137 (4.9) | 218 (1.5) | 3.8 (3.1 to 4.4) | 1.1 (1.0 to 1.6) | 3.57 (2.85 to 4.49) | 36.294 | 195.893 | 65 (2.3) | 121 (0.9) | 2.90 (2.12 to 3.99) |

| Age | ||||||||||

| <18 yr | 10 (2.7) | 23 (1.2) | 1.9 (0.7 to 3.1) | 0.9 (0.5 to 1.2) | 2.41 (1.09 to 5.29) | 5.186 | 26.820 | 5 (1.3) | 13 (0.7) | 1.97 (0.65 to 5.97) |

| 18–39 yr | 80 (4.8) | 126 (1.5) | 3.2 (2.5 to 3.9) | 1.0 (0.8 to 1.1) | 3.30 (2.47 to 4.42) | 25.210 | 129.015 | 46 (2.8) | 83 (1.0) | 2.81 (1.93 to 4.10) |

| 40–59 yr | 71 (5.2) | 126 (1.8) | 4.1 (3.2 to 5.1) | 1.4 (1.1 to 1.6) | 3.03 (2.22 to 4.15) | 17.175 | 92.356 | 25 (1.8) | 70 (1.0) | 1.84 (1.11 to 3.04) |

| ≥60 yr | 35 (6.1) | 55 (1.9) | 8.1 (5.4 to 10.8) | 1.9 (1.4 to 2.4) | 4.56 (2.79 to 7.45) | 4.309 | 28.912 | 15 (2.6) | 18 (0.6) | 6.57 (2.95 to 14.67) |

| Calendar yr | ||||||||||

| 1974–1994 | 72 (6.8) | 137 (2.6) | 3.1 (2.4 to 3.8) | 1.1 (0.9 to 1.3) | 2.99 (2.20 to 4.06) | 23.236 | 125.109 | 39 (3.7) | 73 (1.4) | 3.08 (2.03 to 4.68) |

| 1995–2005 | 104 (6.3) | 152 (1.8) | 4.8 (3.9 to 5.7) | 1.3 (1.1 to 1.5) | 3.78 (2.91 to 4.92) | 21.600 | 115.622 | 43 (2.6) | 86 (1.0) | 2.52 (1.73 to 3.67) |

| 2006–2015 | 20 (1.6) | 41 (0.6) | 2.8 (1.6 to 4.1) | 1.1 (0.8 to 1.5) | 2.41 (1.39 to 4.20) | 7.045 | 36.371 | 9 (0.7) | 25 (0.4) | 1.86 (0.84 to 4.10) |

| Education | ||||||||||

| Compulsory school, ≤9 yr | 59 (6.7) | 70 (1.6) | 5.4 (4.0 to 6.8) | 1.1 (0.9 to 1.4) | 4.47 (2.66 to 7.53) | 10.916 | 61.043 | 26 (2.9) | 38 (0.9) | 3.48 (1.69 to 7.19) |

| Upper secondary school, 1–3 yr | 90 (5.1) | 162 (1.8) | 3.8 (3.0 to 4.6) | 1.3 (1.1 to 1.5) | 2.82 (2.01 to 3.97) | 23.714 | 126.862 | 51 (2.9) | 89 (1.0) | 2.74 (1.76 to 4.25) |

| University level | 44 (3.5) | 92 (1.5) | 2.6 (1.9 to 3.4) | 1.1 (0.8 to 1.3) | 3.01 (1.72 to 5.26) | 16.715 | 86.218 | 14 (1.1) | 56 (0.9) | 1.18 (0.51 to 2.72) |

| Unknown | 3 (3.3) | 6 (1.3) | 5.6 (0.0 to 11.9) | 2.0 (0.4 to 3.6) | 3.25 (0.41 to 25.49) | 536 | 2.979 | (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | N/A |

IR, incidence rate; N/A, not able to calculate. Data are displayed with estimate and 95% CI.

Analyses run in strata of patients and five (sex, age, calendar-yr, and county) matched controls additionally adjusted for educational attainment.

Analyses for different periods when the IBD diagnosis was made showed that the association lasts over time, with an aHR of 4.18 (95% CI, 2.22 to 7.85) of having an IBD diagnosis within the first year after the IgAN diagnosis, an aHR of 3.54 (95% CI, 2.58 to 4.87) within 5 years, and an aHR of 3.56 (95% CI, 2.81 to 4.52) within 10 years. In the analysis excluding the first year of follow-up after IgAN diagnosis, the aHR was 3.21 (95% CI, 2.64 to 3.90).

Analyses by Type of IBD (UC, CD, and IBD-U)

Subgroup analyses showed a stronger association between IgAN and UC than CD: an aHR of 2.60 (95% CI, 1.70 to 3.97) versus 1.55 (95% CI, 0.84 to 2.85), as presented in Tables 3–5. The association and aHRs were consistent even when restricting the analyzes to patients with an IBD diagnosis ≥2 times in the NPR: UC aHR 2.65 (95% CI, 1.71 to 4.11) versus CD aHR 1.10 (95% CI, 0.51 to 2.38). The aHR for having ≥2 records of IBD-U was 3.54 (95% CI, 2.48 to 5.04).

Table 3.

UC in patients with IgAN

| Characteristic | IgAN with UC (%) | Controls with UC (%) | IR IgAN with UC | IR Controls with UC | aHRa | Total Number of Follow-Up Yr IgAN | Total Number of Follow-Up Yr Controls | IgAN with UC ≥2 Diagnoses (%) | Controls with UC ≥2 Diagnoses (%) | aHRa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 34 (0.8) | 74 (0.4) | 0.6 (0.4 to 0.8) | 0.3 (0.2 to 0.3) | 2.60 (1.70 to 3.97) | 53,751 | 280,268 | 32 (0.8) | 70 (0.3) | 2.65 (1.71 to 4.11) |

| Sex | ||||||||||

| Female | 4 (0.3) | 10 (0.2) | 0.2 (0.0 to 0.5) | 0.1 (0.0 to 0.2) | 2.04 (0.59 to 7.07) | 16,214 | 82,402 | 8 (0.7) | 12 (0.2) | 3.48 (1.34 to 9.04) |

| Male | 30 (1.0) | 64 (0.4) | 0.8 (0.5 to 1.1) | 0.3 (0.2 to 0.4) | 2.60 (1.66 to 4.09) | 37,536 | 197,865 | 24 (0.8) | 58 (0.4) | 2.41 (1.47 to 3.96) |

| Age | ||||||||||

| <18 yr | 3 (0.8) | 4 (0.2) | 0.6 (0.0 to 1.2) | 0.1 (0.0 to 0.3) | 4.21 (0.82 to 21.48) | 5310 | 27,079 | 3 (0.8) | 2 (0.1) | N/A |

| 18–39 yr | 18 (1.1) | 32 (0.4) | 0.7 (0.4 to 1.0) | 0.2 (0.2 to 0.3) | 3.02 (1.64 to 5.54) | 26,087 | 130,336 | 16 (0.9) | 35 (0.4) | 1.79 (0.78 to 4.09) |

| 40–59 yr | 10 (0.7) | 30 (0.4) | 0.6 (0.2 to 0.9) | 0.3 (0.2 to 0.4) | 1.79 (0.86 to 3.75) | 17,802 | 93,490 | 8 (0.6) | 27 (0.4) | 10.72 (2.14 to 53.74) |

| ≥60 yr | 3 (0.5) | 8 (0.3) | 0.7 (0.0 to 1.4) | 0.3 (0.1 to 0.5) | 3.41 (0.67 to 17.33) | 5550 | 29,361 | 5 (0.9) | 6 (0.2) | 2.24 (1.08 to 4.65) |

| Calendar yr | ||||||||||

| 1974–1994 | 12 (1.1) | 36 (0.7) | 0.5 (0.2 to 0.8) | 0.3 (0.2 to 0.4) | 2.01 (1.01 to 4.01) | 23,855 | 126,253 | 11 (1.0) | 34 (0.6) | 3.00 (1.61 to 5.59) |

| 1995–2005 | 19 (1.1) | 34 (0.4) | 0.8 (0.5 to 1.2) | 0.3 (0.2 to 0.4) | 2.82 (1.58 to 5.04) | 22,603 | 117,103 | 17 (1.0) | 29 (0.3) | 2.84 (0.77 to 10.55) |

| 2006–2015 | 3 (0.2) | 4 (0.1) | 0.4 (0.0 to 0.9) | 0.1 (0.0 to 0.2) | 3.04 (0.58 to 15.81) | 7292 | 36,911 | 4 (0.3) | 7 (0.1) | 4.20 (1.37 to 12.86) |

| Education | ||||||||||

| Compulsory school, ≤9 yr | 9 (1.0) | 10 (0.2) | 0.8 (0.3 to 1.3) | 0.2 (0.1 to 0.3) | 3.23 (1.02 to 10.22) | 11,380 | 61,881 | 10 (1.1) | 14 (0.3) | 4.20 (1.37 to 12.86) |

| Upper secondary school, 1–3 yr | 18 (1.0) | 35 (0.4) | 0.7 (0.4 to 1.1)) | 0.3 (0.2 to 0.4) | 2.57 (1.23 to 5.37) | 24,627 | 128,294 | 17 (1.0) | 31 (0.3) | 2.96 (1.36 to 6.42) |

| University level | 7 (0.6) | 28 (0.4) | 0.4 (0.1 to 0.7) | 0.3 (0.2 to 0.4) | 1.06 (0.34 to 3.30) | 17,178 | 87,062 | 5 (0.4) | 25 (0.4) | 1.05 (0.22 to 4.99) |

| Unknown | (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | 0.0 (0.0 to 0.0) | 0.3 (0.0 to 0.1) | N/A | 564 | 3029 | (0.0) | (0.0) | N/A |

IR, Incidence rate; N/A, Not able to calculate. Data are displayed with estimate and 95% CI.

Analyses run in strata of patients and five (sex, age, calendar-yr, and county) matched controls additionally adjusted for educational attainment.

Table 5.

IBD-U in patients with IgAN

| Characteristic | IgAN with IBD-U (%) | Controls with IBD-U (%) | IR IgAN with IBD-U | IR Controls with IBD-U | aHRa | Total Number of Follow-Up Yr IgAN | Total Number of Follow-Up Yr Controls | IgAN with IBD-U ≥2 Diagnoses (%) | Controls with IBD-U ≥2 Diagnoses (%) | aHRa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 148 (3.7) | 213 (1.1) | 2.8 (2.4 to 3.3) | 0.8 (0.7 to 0.9) | 3.90 (3.11 to 4.87) | 52,803 | 279,159 | 58 (1.4) | 82 (0.4) | 3.54 (2.48 to 5.04) |

| Sex | ||||||||||

| Female | 52 (4.4) | 85 (1.4) | 3.3 (2.4 to 4.2) | 1.0 (0.8 to 1.3) | 3.33 (2.31 to 4.79) | 15,817 | 81,787 | 19 (1.6) | 37 (0.6) | 2.58 (1.46 to 4.56) |

| Male | 96 (3.4) | 128 (0.9) | 2.6 (2.1 to 3.1) | 0.6 (0.5 to 0.8) | 4.51 (3.38 to 6.03) | 36,985 | 197,371 | 39 (1.4) | 45 (0.3) | 4.34 (2.74 to 6.88) |

| Age | ||||||||||

| <18 yr | 5 (1.3) | 16 (0.9) | 0.9 (0.1 to 1.8) | 0.6 (0.3 to 0.9) | 1.38 (0.47 to 4.07) | 5289 | 26,894 | 1 (0.3) | 7 (0.4) | 0.71 (0.08 to 6.30) |

| 18–39 yr | 58 (3.5) | 70 (0.8) | 2.3 (1.7 to 2.8) | 0.5 (0.4 to 0.7) | 4.30 (2.99 to 6.17) | 25,625 | 129,894 | 29 (1.7) | 30 (0.4) | 4.18 (2.45 to 7.14) |

| 40–59 yr | 57 (4.1) | 85 (1.2) | 3.3 (2.4 to 4.1) | 0.9 (0.7 to 1.1) | 3.67 (2.54 to 5.30) | 17,511 | 93,301 | 16 (1.1) | 36 (0.5) | 2.22 (1.13 to 4.37) |

| ≥60 yr | 28 (4.9) | 42 (1.4) | 6.4 (4.0 to 8.8) | 1.4 (1.0 to 1.9) | 4.78 (2.73 to 8.37) | 4377 | 29,068 | 12 (2.0) | 9 (0.3) | 13.87 (4.24 to 45.39) |

| Calendar yr | ||||||||||

| 1974–1994 | 52 (4.9) | 85 (1.6) | 2.2 (1.6 to 2.8) | 0.7 (0.5 to 0.8) | 3.63 (2.49 to 5.30) | 23,540 | 125,854 | 26 (2.4) | 22 (0.4) | 6.77 (3.52 to 13.01) |

| 1995–2005 | 80 (4.8) | 96 (1.1) | 3.6 (2.8 to 4.4) | 0.8 (0.7 to 1.0) | 4.75 (3.46 to 6.52) | 22,101 | 116,572 | 28 (1.7) | 45 (0.5) | 3.12 (1.92 to 5.06) |

| 2006–2015 | 16 (1.3) | 32 (0.5) | 2.2 (1.1 to 3.3) | 0.9 (0.6 to 1.2) | 2.39 (1.29 to 4.41) | 7161 | 36,732 | 4 (0.3) | 15 (0.2) | 1.09 (0.34 to 3.48) |

| Education | ||||||||||

| Compulsory school, ≤9 yr | 47 (5.3) | 50 (1.2) | 4.2 (3.0 to 5.4) | 0.8 (0.6 to 1.0) | 6.00 (3.14 to 11.46) | 11,166 | 61,582 | 17 (1.9) | 17 (0.4) | 6.75 (2.13 to 21.39) |

| Upper secondary school, 1–3 yr | 63 (3.6) | 108 (1.2) | 2.6 (2.0 to 3.2) | 0.8 (0.7 to 1.0) | 2.84 (1.89 to 4.28) | 24,193 | 127,652 | 30 (1.7) | 45 (0.5) | 2.72 (1.51 to 4.90) |

| University level | 35 (2.8) | 50 (0.8) | 2.1 (1.4 to 2.8) | 0.6 (0.4 to 0.7) | 6.46 (2.88 to 14.51) | 16,905 | 86,938 | 11 (0.9) | 19 (0.3) | 3.21 (0.94 to 11.00) |

| Unknown | 3 (3.3) | 5 (1.1) | 5.6 (0.0 to 11.9) | 1.7 (0.2 to 3.1) | 6.53 (0.53 to 80.93) | 537 | 2985 | (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | N/A |

IR, Incidence rate; N/A, Not able to calculate. Data are displayed with estimate and 95% CI.

Analyses run in strata of patients and five (sex, age, calendar-yr, and county) matched controls additionally adjusted for educational attainment.

Table 4.

Mb Crohn in patients with IgAN

| Characteristic | IgAN with CD (%) | Controls with CD (%) | IR IgAN with CD | IR Controls with CD | aHRa | Total Number of Follow-Up Yr IgAN | Total Number of Follow-Up Yr Controls | IgAN with CD ≥2 Diagnoses (%) | Controls with CD ≥2 Diagnoses (%) | aHRa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 14 (0.3) | 43 (0.2) | 0.3 (0.1 to 0.4) | 0.2 (0.1 to 0.2) | 1.55 (0.84 to 2.85) | 54,050 | 280,708 | 8 (0.2) | 38 (0.2) | 1.10 (0.51 to 2.38) |

| Sex | ||||||||||

| Female | 3 (0.3) | 17 (0.3) | 0.2 (0.0 to 0.4) | 0.2 (0.1 to 0.3) | 0.72 (0.20 to 2.54) | 16,239 | 8, 347 | 1 (0.1) | 15 (0.3) | 0.31 (0.04 to 2.40) |

| Male | 11 (0.4) | 26 (0.2) | 0.3 (0.1 to 0.5) | 0.1 (0.1 to 0.2) | 2.11 (1.03 to 4.33) | 37,810 | 198,360 | 7 (0.2) | 23 (0.2) | 1.65 (0.69 to 3.97) |

| Age | ||||||||||

| <18 yr | 2 (0.5) | 3 (0.2) | 0.4 (0.0 to 0.9) | 0.1 (0.0 to 0.2) | 2.29 (0.32 to 16.42) | 5287 | 27,109 | 1 (0.3) | 4 (0.2) | 0.81 (0.07 to 9.36) |

| 18–39 yr | 4 (0.2) | 24 (0.3) | 0.2 (0.0 to 0.3) | 0.2 (0.1 to 0.3) | 0.82 (0.28 to 2.39) | 26,223 | 130,470 | 4 (0.2) | 21 (0.2) | 1.11 (0.37 to 3.34) |

| 40–59 yr | 4 (0.3) | 11 (0.2) | 0.2 (0.0 to 0.4) | 0.1 (0.0 to 0.2) | 2.64 (0.74 to 9.38) | 17,968 | 93,703 | 2 (0.1) | 10 (0.1) | 1.27 (0.25 to 6.41) |

| ≥60 yr | 4 (0.7) | 5 (0.2) | 0.9 (0.0 to 1.7) | 0.2 (0.0 to 0.3) | 4.89 (0.88 to 27.16) | 4569 | 29,425 | 1 (0.2) | 3 (0.1) | 2.12 (0.10 to 43.54) |

| Calendar yr | ||||||||||

| 1974–1994 | 8 (0.8) | 16 (0.3) | 0.3 (0.1 to 0.6) | 0.1 (0.1 to 0.2) | 2.14 (0.86 to 5.30) | 23,933 | 126,303 | 4 (0.4) | 14 (0.3) | 1.63 (0.49 to 5.37) |

| 1995–2005 | 5 (0.3) | 22 (0.3) | 0.2 (0.0 to 0.4) | 0.2 (0.1 to 0.3) | 1.12 (0.41 to 3.09) | 22,790 | 117,329 | 3 (0.2) | 20 (0.2) | 0.77 (0.23 to 2.64) |

| 2006–2015 | 1 (0.1) | 5 (0.1) | 0.1 (0.0 to 0.4) | 0.1 (0.0 to 0.3) | 0.83 (0.08 to 8.73) | 7326 | 37,075 | 1 (0.1) | 4 (0.1) | 1.48 (0.13 to 16.30) |

| Education | ||||||||||

| Compulsory School, ≤9 yr | 3 (0.3) | 10 (0.2) | 0.3 (0.0 to 0.6) | 0.2 (0.1 to 0.3) | 1.16 (0.20 to 6.64) | 11,514 | 61,882 | 2 (0.2) | 10 (0.2) | 1.13 (0.18 to 7.12) |

| Upper secondary school, 1–3 yr | 9 (0.5) | 19 (0.2) | 0.4 (0.1 to 0.6) | 0.1 (0.1 to 0.2) | 2.21 (0.85 to 5.76) | 24,708 | 128,577 | 5 (0.3) | 11 (0.1) | 2.04 (0.62 to 6.64) |

| University level | 2 (0.2) | 14 (0.2) | 0.1 (0.0 to 0.3) | 0.2 (0.1 to 0.2) | 0.84 (0.16 to 4.44) | 17,263 | 87,212 | 1 (0.1) | 17 (0.3) | 0.34 (0.04 to 2.90) |

| Unknown | (0.0) | (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0 to 0.0) | 0.0 (0.0 to 0.0) | N/A | 563 | 3036 | (0.0) | (0.0) | N/A |

IR, Incidence rate; N/A, Not able to calculate. Data are displayed with estimate and 95% CI.

Analyses run in strata of patients and five (sex, age, calendar-yr, and county) matched controls additionally adjusted for educational attainment.

Risk of having an IBD Diagnosis before IgAN

In total, 103 of 4066 patients with IgAN (2.53%) versus 220 of 20,198 controls (1.09%) had a confirmed diagnosis of IBD. The conditional logistics regression showed an OR of 2.37 (95% CI, 1.87 to 3.01) for having earlier IBD in IgAN. The ORs for the different subtypes of IBD were as follows: IBD-U OR 2.41 (95% CI, 1.74 to 3.33), CD OR 2.43 (95% CI, 1.38 to 4.27), and UC OR 2.20 (95% CI, 1.43 to 3.40).

Risk of ESKD

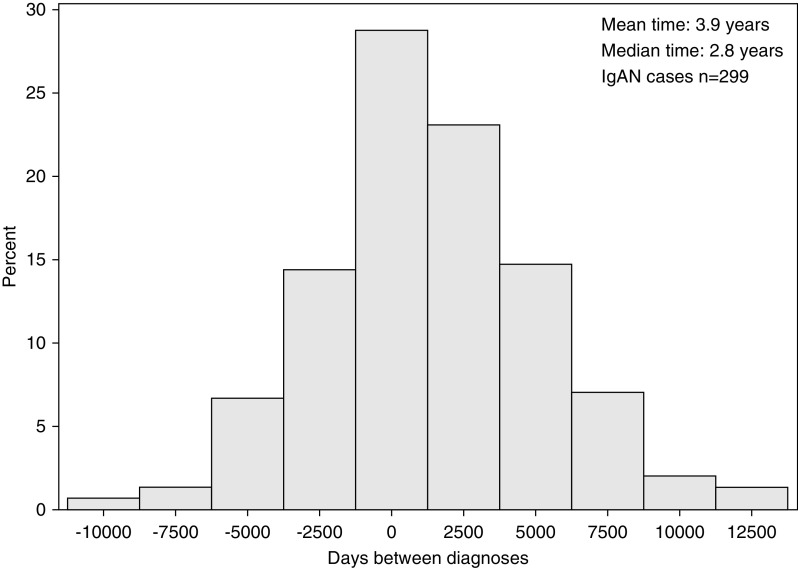

We identified 103 patients with an IBD diagnosis before they were diagnosed with IgAN and 196 patients with the diagnosis of IBD after their IgAN diagnosis. For these 299 patients, the mean time between the two diagnoses was 3.9 years and the median time was 2.8 years (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Time between IgAN and IBD diagnoses. Day 0 is date of IgAN biopsy.

In all, 148 of 299 (50%) patients with IgAN ever diagnosed with IBD developed ESKD. In comparison, seven of the 550 (1.3%) control individuals with IBD without biopsy-proven IgAN developed ESKD during follow-up. Corresponding numbers for patients with IgAN without IBD were 927 of 3767 (25%). A logistic regression modeling the risk of ever experiencing ESKD comparing these patients with IgAN that ever versus never were given an IBD diagnosis during follow-up obtained an OR of 2.60 (95% CI, 2.02 to 3.35).

At diagnosis, 3689 of the patients with IgAN did not have ESKD (86 with IBD at baseline and 3603 without, of whom 153 were diagnosed during follow-up). Cox regressions comparing individuals with versus without IBD at baseline showed an HR of 1.59 (95% CI, 1.04 to 2.44).

In addition, Cox regressions comparing individuals with and without IBD ever during follow-up indicated an HR of 1.89 (95% CI, 1.50 to 2.37). When IBD was treated as a time-variant, the HR was 1.84 (95% CI, 1.33 to 2.55).

Discussion

Principal Findings

Our study showed a significant association between IBD and IgAN both before and after the diagnosis of IgAN. We also demonstrated an increased risk of ESKD in patients with IgAN with IBD compared with patients with IgAN without IBD.

Comparison with Other Studies

Our results are in line with those of Ambruzs et al.,20 whose review of renal biopsy specimens showed a three-times-higher prevalence of IgAN in patients with IBD (24%) compared with non-IBD patients who underwent a kidney biopsy (8%). In total, we identified 299 patients with IBD before or after diagnosis in 4066 patients with IgAN (7.4%), which is similar or slightly higher than in a recent Finnish study that reported 4.6% IBD in patients with IgAN.29 This study showed no effect on ESKD when comparing individuals with or without IBD, but only identified seven patients with both IgAN and IBD and thus lacked power to detect such differences.

The few other available studies on IgAN and IBD comorbidity have shown an elevated risk of impaired kidney function and even ESKD due to different pathophysiologic relationships in patients with IBD. Renal manifestations have been reported in 4%–23% of patients with IBD. The most frequent underlying causes are nephrolithiasis, GN, tubulointerstitial nephritis, secondary amyloidosis, repeated dehydration, and adverse drug effects.30,31 Park et al.30 showed a significantly higher risk of developing ESKD in patients with CD compared with the general population (even if still rare). Grupper et al.32 studied the outcome of kidney transplantation in patients with IBD and the course of IBD status after transplantation. The authors concluded that all patients were in remission before transplantation and remained in remission. The risk of hospitalization, mainly because of infections and death, was higher in the IBD patient group.

A recent study by Vajravelu et al.33 showed that 5.1% of patients with IBD developed ESKD on the basis of diagnostic criteria or eGFR. In our study we demonstrated a cumulative ESKD incidence of 50% in patients with IgAN with IBD but only 1.5% in patients with IBD without IgAN.

Because IgA antibodies are mainly produced by the mucosal tissue, the role of the gut microbiota in IgAN has been considered since IgAN was first identified by Berger and Hinglais. The full pathophysiologic connection between IgAN and IBD remains to be unraveled, although some common mechanisms are thought to contribute to their inflammatory conditions. First, it has been suggested that abnormal helper T cells stimulate plasma cells in the bone marrow to secrete polymeric IgA1.16,34,35 This contention is supported by Kett et al.,36 who showed a significant increase of IgA1-producing cells in the colonic tissue of patients with IBD. Findings have been reported of raised levels of the cytokine IL-17 that promote inflammation in both the intestinal mucosa in patients with CD and the tubular epithelial cells in patients with IgAN.17,37 Finally, common genetic factors, especially HLA-DR1, are a potential link between the diseases.15,16 Genetic studies18,19 found risk loci for IgAN either directly associated with the risk of IBD or associated with the maintenance of the intestinal epithelial barrier and response to mucosal pathogens.

Another study that supports the involvement of the mucosal immune system in IgAN treated patients with IgAN with locally acting glucocorticoids targeting the ileocecal region of the intestine.38 The treatment resulted in a significant decrease in urine albumin excretion. This finding, together with our findings showing that UC is more strongly associated with IgAN than CD, indicates that inflammation in the colon is more likely linked to the development of GN. The slightly higher HR for IBD-U probably reflects that IBD-U is often the first code used in the clinical work-up for patients with IBD.

It is possible that the chronic inflammatory state in the GI mucosa may drive antibody production, including the aberrantly glycosylated antibodies seen in IgAN tissue samples, and that this could potentially explain why the risk of ESKD was higher in patients with IgAN with IBD compared with those without IBD. Other potential mechanisms for the increased risk of ESKD include different nutritional state and potentially nephrotoxic medications used in patients with IBD. Further studies on IgAN screening in patients with IBD and vice versa are warranted.

Strengths and Limitations

The main strengths of our study are the large cohort of well-characterized individuals and long follow-up (median 12.6 years). Another strength is the unambiguous results of the sensitivity and stratified analyses, showing an increased risk in both men and women and across age-groups. The results for different age-groups all have overlapping but significant CIs. The study also has several weaknesses, including the risk of ascertainment bias. However, our analysis restricted to 14,081 controls with at least one entry in the NPR, and hence seen by a medical specialist during follow-up, only slightly attenuated our association from 3.29 to 2.96. Moreover, excluding the first year of follow-up (where this type of bias is usually most pronounced) did not change our estimate more than marginally (3.21 versus 3.29). Hence, we believe that our findings were not driven by ascertainment bias. Nevertheless, given the observational design, we cannot rule out that unmeasured confounding may have affected the results. Further, the exposure/intervention “IBD” is not well defined, as you cannot randomize individuals to the condition, and hence the results of this study should not be causally interpreted.

Another limitation is that our study is limited to patients with biopsy-verified IgAN. Consequently, our results might not apply to patients with a clinically mild or asymptomatic IgAN disease. We did not include data on medication for either condition or examine the association between severities of the two diseases. Patients with IBD on nephrotoxic tacrolimus medication may have been examined with a kidney biopsy revealing a previously asymptomatic IgAN. Moreover, data on contemporary patients with IgAN diagnosed after 2011 are lacking.

Implication of the Findings

Our findings suggest an association between IBD and IgAN. Identification of IBD in patients with IgAN may be useful for the risk prediction of ESKD. Additional studies are necessary to elucidate whether screening and optimized treatment for IBD improve prognosis in patients with IgAN.

The awareness of an increased risk of renal impairment and the need for an early finding have been addressed previously.30,31 Although the American Gastroenterology Association guidelines for IBD39 recommend assessing for comorbidities, they only provide examples with other GI conditions. In the nephrologists’ Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes guidelines,40 they recommend the assessment of every biopsy-proven IgAN case for causes of “secondary IgAN.” Secondary IgAN is described as a rare form of IgAN associated with other diseases (e.g., liver cirrhosis, HIV, and IBD). There is no established definition or different histologic findings in secondary IgAN cases, so the basis for the term is questionable.41

Whether there is a different pathophysiologic mechanism in primary IgAN compared with an IgAN driven by IBD is not within the scope of our study. However, systematic screening for IgAN (in terms of laboratory tests for kidney disorder in gastroenterologic departments and increased awareness of signs and symptoms of IBD in renal departments) appears to be warranted.

We found an association between IgAN and IBD and further that a diagnosis of IBD was associated with future ESKD. Further studies on both pathophysiologic mechanisms and comorbidity effect are justified.

Disclosures

L. Emilsson reports Scientific Advisor or Membership as Academic Editor for PLOS ONE. J.F. Ludvigsson coordinates a study on behalf of the Swedish IBD quality register (SWIBREG) and that study has received funding from Janssen corporation. All remaining authors have nothing to dislose.

Funding

J. Rehnberg has funding from the County Council of Värmland (Region Värmland), Sweden. The sponsor had no role in the study design; data collection; data analysis; interpretation of data; writing of the report; and the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Dr. Johanna Rehnberg, Dr. Jonas F. Ludvigsson, and Dr. Louis Emilsson designed the study. Dr. Johanna Rehnberg and Dr. Louise Emilsson analyzed the data. Dr. Johanna Rehnberg made the tables and figure and drafted the paper, with inputs from Dr. Louise Emilsson, Dr. Jonas F. Ludvigsson, and Dr. Adina Symreng. Dr. Louise Emilsson supervised the study. All of the authors approved the final version of the manuscript. The corresponding author (Dr. Louise Emilsson) had full access to all of the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2020060848/-/DCSupplemental.

Supplemental Appendix. Definitions and ICD codes for ESKD, IBD, hypertension, heart failure, and diabetes.

References

- 1.Berger J, Hinglais N: [Intercapillary deposits of IgA-IgG]. J Urol Nephrol (Paris) 74: 694–695, 1968 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.D’Amico G: The commonest glomerulonephritis in the world: IgA nephropathy. Q J Med 64: 709–727, 1987 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Donadio JV, Grande JP: IgA nephropathy. N Engl J Med 347: 738–748, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.D’Amico G: Natural history of idiopathic IgA nephropathy and factors predictive of disease outcome. Semin Nephrol 24: 179–196, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wyatt RJ, Julian BA: IgA nephropathy. N Engl J Med 368: 2402–2414, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simon P, Ramée MP, Autuly V, Laruelle E, Charasse C, Cam G, et al.: Epidemiology of primary glomerular diseases in a French region. Variations according to period and age. Kidney Int 46: 1192–1198, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tiebosch ATMG, Wolters J, Frederik PFM, van der Wiel TW, Zeppenfeldt E, van Breda Vriesman PJ: Epidemiology of idiopathic glomerular disease: A prospective study. Kidney Int 32: 112–116, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stratta P, Segoloni GP, Canavese C, Sandri L, Mazzucco G, Roccatello D, et al.: Incidence of biopsy-proven primary glomerulonephritis in an Italian province. Am J Kidney Dis 27: 631–639, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wyatt RJ, Julian BA, Baehler RW, Stafford CC, McMorrow RG, Ferguson T, et al.: Epidemiology of IgA nephropathy in central and eastern Kentucky for the period 1975 through 1994. Central Kentucky Region of the Southeastern United States IgA Nephropathy DATABANK Project. J Am Soc Nephrol 9: 853–858, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Briganti EM, Dowling J, Finlay M, Hill PA, Jones CL, Kincaid-Smith PS, et al.: The incidence of biopsy-proven glomerulonephritis in Australia. Nephrol Dial Transplant 16: 1364–1367, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McGrogan A, Franssen CFM, de Vries CS: The incidence of primary glomerulonephritis worldwide: A systematic review of the literature. Nephrol Dial Transplant 26: 414–430, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Welander A, Sundelin B, Fored M, Ludvigsson JF: Increased risk of IgA nephropathy among individuals with celiac disease. J Clin Gastroenterol 47: 678–683, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hirsch DJ, Jindal KK, Trillo A, Cohen AD: Acute renal failure in Crohn’s disease due to IgA nephropathy. Am J Kidney Dis 20: 189–190, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Filiopoulos V, Trompouki S, Hadjiyannakos D, Paraskevakou H, Kamperoglou D, Vlassopoulos D: IgA nephropathy in association with Crohn’s disease: A case report and brief review of the literature. Ren Fail 32: 523–527, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oikonomou K, Kapsoritakis A, Eleftheriadis T, Stefanidis I, Potamianos S: Renal manifestations and complications of inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 17: 1034–1045, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Terasaka T, Uchida HA, Umebayashi R, Tsukamoto K, Tanaka K, Kitagawa M, et al.: The possible involvement of intestine-derived IgA1: A case of IgA nephropathy associated with Crohn’s disease. BMC Nephrol 17: 122, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choi JY, Yu CH, Jung HY, Jung MK, Kim YJ, Cho JH, et al.: A case of rapidly progressive IgA nephropathy in a patient with exacerbation of Crohn’s disease. BMC Nephrol 13: 84, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kiryluk K, Li Y, Scolari F, Sanna-Cherchi S, Choi M, Verbitsky M, et al.: Discovery of new risk loci for IgA nephropathy implicates genes involved in immunity against intestinal pathogens. Nat Genet 46: 1187–1196, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shi D, Zhong Z, Wang M, Cai L, Fu D, Peng Y, et al.: Identification of susceptibility locus shared by IgA nephropathy and inflammatory bowel disease in a Chinese Han population. J Hum Genet 65: 241–249, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ambruzs JM, Walker PD, Larsen CP: The histopathologic spectrum of kidney biopsies in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 9: 265–270, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elaziz MMA, Fayed A: Patterns of renal involvement in a cohort of patients with inflammatory bowel disease in Egypt. Acta Gastroenterol Belg 81: 381–385, 2018 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ludvigsson JF, Otterblad-Olausson P, Pettersson BU, Ekbom A: The Swedish personal identity number: Possibilities and pitfalls in healthcare and medical research. Eur J Epidemiol 24: 659–667, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.SNOMED International : SNOMED CT, Swedish Edition v1.37.3, 2018. Available at: https://www.nlm.nih.gov/healthit/snomedct/international.html. Accessed October 27, 2020

- 24.Jarrick S, Lundberg S, Welander A, Fored CM, Ludvigsson JF: Clinical validation of immunoglobulin A nephropathy diagnosis in Swedish biopsy registers. Clin Epidemiol 9: 67–73, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ludvigsson JF, Andersson E, Ekbom A, Feychting M, Kim JL, Reuterwall C, et al.: External review and validation of the Swedish national inpatient register. BMC Public Health 11: 450, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jakobsson GL, Sternegård E, Olén O, Myrelid P, Ljung R, Strid H, et al.: Validating inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in the Swedish National Patient Register and the Swedish Quality Register for IBD (SWIBREG). Scand J Gastroenterol 52: 216–221, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ludvigsson JF, Almqvist C, Bonamy AKE, Ljung R, Michaëlsson K, Neovius M, et al.: Registers of the Swedish total population and their use in medical research. Eur J Epidemiol 31: 125–136, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ludvigsson JF, Håberg SE, Knudsen GP, Lafolie P, Zoega H, Sarkkola C, et al.: Ethical aspects of registry-based research in the Nordic countries. Clin Epidemiol 7: 491–508, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pohjonen J, Nurmi R, Metso M, Oksanen P, Huhtala H, Pörsti I, et al.: Inflammatory bowel disease in patients undergoing renal biopsies. Clin Kidney J 12: 645–651, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park S, Chun J, Han KD, Soh H, Choi K, Kim JH, et al.: Increased end-stage renal disease risk in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: A nationwide population-based study. World J Gastroenterol 24: 4798–4808, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pardi DS, Tremaine WJ, Sandborn WJ, McCarthy JT: Renal and urologic complications of inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol 93: 504–514, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grupper A, Schwartz D, Baruch R, Schwartz IF, Nakache R, Goykhman Y, et al.: Kidney transplantation in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD): Analysis of transplantation outcome and IBD activity. Transpl Int 32: 730–738, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vajravelu RK, Copelovitch L, Osterman MT, Scott FI, Mamtani R, Lewis JD, et al.: Inflammatory bowel diseases are associated with an increased risk for chronic kidney disease, which decreases with age. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 18: 2262–2268, 2019; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Coppo R: The gut-renal connection in IgA nephropathy. Semin Nephrol 38: 504–512, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Trimarchi HM, Iotti A, Iotti R, Freixas EA, Peters R: Immunoglobulin A nephropathy and ulcerative colitis. A focus on their pathogenesis. Am J Nephrol 21: 400–405, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kett K, Brandtzaeg P: Local IgA subclass alterations in ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease of the colon. Gut 28: 1013–1021, 1987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lin FJ, Jiang GR, Shan JP, Zhu C, Zou J, Wu XR: Imbalance of regulatory T cells to Th17 cells in IgA nephropathy. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 72: 221–229, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smerud HK, Bárány P, Lindström K, Fernström A, Sandell A, Påhlsson P, et al.: New treatment for IgA nephropathy: Enteric budesonide targeted to the ileocecal region ameliorates proteinuria. Nephrol Dial Transplant 26: 3237–3242, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.American Gastroenterological Association . Available at: https://www.gastro.org/guidelines/ibd-and-bowel-disorders. Accessed October 27, 2020

- 40.Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Glomerulonephritis Work Group : KDIGO Clinical practice guideline for glomerulonephritis. Available at: https://www.kdigo.org/guidelines/gn/. Accessed October 27, 2020

- 41.Saha MK, Julian BA, Novak J, Rizk DV: Secondary IgA nephropathy. Kidney Int 94: 674–681, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.