Abstract

Background:

Recurrent adrenocortical carcinoma (ACC) is an aggressive disease with few options offering durable survival benefit. Despite metastasectomy, recurrence is common. Cytoreduction and intraperitoneal chemotherapy have offered improved survival in other advanced cancers. We sought to evaluate the use of cytoreduction and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) for the treatment of recurrent intraperitoneal ACC.

Methods:

A phase II, single institution clinical trial was approved for patients with radiographic evidence of resectable ACC limited to the peritoneum. Patients underwent treatment if optimal cytoreduction was deemed possible at exploratory laparotomy. Primary outcome was intraperitoneal progression-free survival. Secondary outcomes were treatment-related morbidities and overall survival.

Results:

Sixty-three patients were evaluated, of whom 11 met eligibility criteria. Nine patients underwent cytoreduction and HIPEC, including one patient who recurred and was re-treated (n = 10 treatments). One patient could not be optimally cytoreduced for HIPEC and therefore did not receive intraperitoneal chemotherapy. There was no perioperative mortality; perioperative comorbidities were limited to Clavien-Dindo grade 2 or 3 and included hematologic, infectious, and neurologic complications.

Seven patients experienced disease recurrence and two patients died of disease during follow-up (median 24 mo). Intraperitoneal progression-free survival was 19 mo, and median overall survival has not yet been reached.

Conclusions:

Cytoreduction and HIPEC can be performed safely in selected patients. Patients with recurrent ACC confined to the peritoneal cavity can be considered for regional therapy in experienced hands. However, disease recurrence is common, and other treatment options should be explored.

Keywords: Adrenocortical carcinoma, Cytoreduction, Intraperitoneal chemotherapy

Introduction

Adrenocortical carcinoma (ACC) is a rare tumor with an estimated 5-y survival of 25%–35%.1,2 Despite complete surgical resection, disease recurrence is observed in up to 85% of patients.2,3 Systemic chemotherapy (e.g., etoposide, doxorubicin, cisplatin, and mitotane) offers modest benefit in progression-free survival (PFS) but no benefit in overall survival.1,4 Targeted molecular therapy with tyrosine kinase (i.e., imatinib, sunitinib), angiogenesis (i.e., bevacizumab), and mTOR (i.e., everolimus) inhibitors also provide no demonstrable survival benefit.5 Metastasectomy for recurrent and/or metastatic ACC has been reported previously as safe and associated with improved PFS and overall survival. However, evidence suggests that recurrence is common after metastasectomy.6–11

Cytoreductive surgery (CRS) with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) is a treatment strategy that achieves locoregional disease control and has been associated with improved survival in advanced malignancies like appendiceal, colorectal, and ovarian cancers.12 CRS with HIPEC allows direct contact of chemotherapy with tumor cells at a higher concentration than would be tolerated with systemic administration. The combination of chemotherapy and hyperthermia may have a synergistic, toxic effect on residual microscopic tissue remaining after resection, thus improving local control. Given the ineffectiveness of systemic chemotherapy for recurrent ACC, alternative treatment strategies warrant consideration. The aim of this study was to evaluate the impact of CRS and HIPEC on intraperitoneal PFS (IP-PFS), treatment-related morbidity, and overall survival in patients with recurrent and/or metastatic ACC limited to the peritoneal cavity.

Methods

Patient and study design

This single-institution, phase II clinical trial received approval from the institutional review board. Informed consent was obtained prior to treatment according to protocol (Clinical-Trials.gov identifier: NCT01833832) by a single surgeon (M.S.H.). Enrollment took place from April 2013 to September 2016, and all patients were treated at the Clinical Research Center at the National Institutes of Health. All patients had histologic confirmation of ACC with disease confined to the peritoneal compartment by cross-sectional imaging. Patients with limited pulmonary metastases were eligible if deemed completely resectable by a thoracic surgeon. All intraperitoneal diseases were amenable to resection or ablation according to cross-sectional imaging in the absence of massive ascites or intestinal obstruction. Patients were aged ≥18 y, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status 2 or less, and life expectancy greater than 3 mo. Patients were excluded from participation if they had a history of congestive heart failure, an ejection fraction less than 40%, creatinine greater than 1.5 mg/dL, significant chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cirrhosis, peripheral neuropathy of grade 2 or greater, brain metastases, pregnancy or active breastfeeding status, history or evidence of severe portal hypertension, or evidence of active systemic infection.

All patients underwent a thorough preoperative evaluation, including medical history, physical examination, routine laboratory studies, baseline echocardiogram (in the instance of prior doxorubicin treatment), and computed tomography imaging of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis. Magnetic resonance imaging brain, positron emission tomography-computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging liver were obtained only as clinically indicated. Histologic diagnosis of ACC was independently confirmed by two pathologists. The modified Weiss criteria were utilized for diagnosis of ACC.13 At operation, exploratory laparotomy was performed, and patients were assessed for extent of disease. Residual disease was classified by completeness of cytoreduction k (CCR): CCR 0, no gross residual disease; CCR 1, fewer than 100 total lesions, all smaller than 5 mm; CCR 2, more than 100 total lesions all less than 5 mm or any one lesion greater than 5 mm; and CCR 3, residual tumor larger than 1 cm.9 HIPEC was performed for patients successfully reduced to CCR 0 or 1. HIPEC was performed using the closed-abdomen technique. Cisplatin (250 mg/m2-L of perfusate) was circulated at approximately 1.0 L/min, with target intra-abdominal temperature of 40◦C for 90 min. During perfusion, constant manual agitation of the abdomen was performed to enable even distribution of the perfusate. Patients also received intravenous sodium thiosulfate upon perfusion (loading dose 7.5 g/m2, then subsequent maintenance infusion of 2.13 g/m2) and for a total of 12 h after initiation for renal protection and limitation of cisplatin toxicity.14,15

Endpoints and assessments

The primary endpoint was IP-PFS as measured from date of cytoreduction and HIPEC. Progressive disease was defined as radiographic evidence of new lesions or ascites. Secondary endpoints included treatment-related morbidity and overall survival.

Assessment methods included postoperative evaluation at 4–8 wk after operation and as clinically indicated until recovery to baseline. Formal evaluations with physical exam, laboratory assessment, and cross-sectional imaging were performed every 3 mo for the first year, every 4 mo for the second year, and every 6 mo for every year thereafter until disease progression or death. Ateach clinic visit, patients were assessed for treatment toxicity, adverse events, quality of life (QoL), and disease progression by imaging and tumor markers where applicable. Complications were assessed by the Clavien-Dindo classification.

QoL characteristics were collected using the FACT-G questionnaire (version 4, http://www.facit.org/facitorg/questionnaires), a validated survey that interrogates physical, emotional, functional, and social well-being in cancer-related issues on a 5-point scale. Potential scores range from 0 to 108 points, with higher scores corresponding to better QoL. QoL was assessed prior to surgery, 6 wk postsurgery, and in regular intervals at 3, 6, 9, and 12 mo after the operation.

Statistics

Historical data indicate that patients with advanced ACC experience a median PFS of 5 mo. It was estimated that the combination of CRS and HIPEC may be associated with a median PFS of 10 mo. Using a one-tailed, α = 0.10, it was estimated that 24 patients would be required to have 80% power to determine a 5-mo improvement in PFS.16

Results

Patients

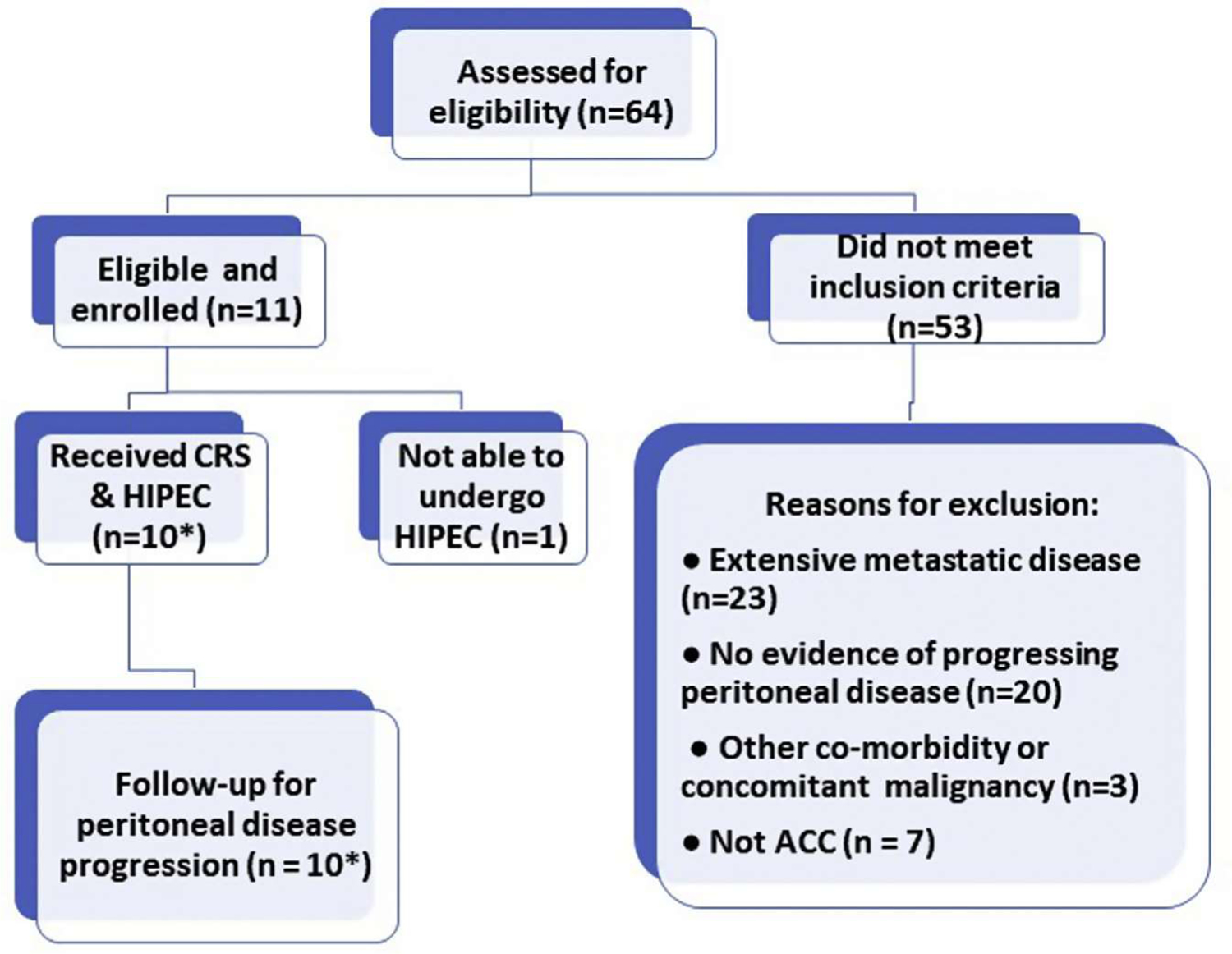

Sixty-three patients with advanced ACC were evaluated for eligibility, of whom 53 did not meet inclusion criteria. Eleven patients were eligible for study enrollment and were scheduled for operation (Fig. 1), including one patient who was re-enrolled and re-treated with a second CRS and HIPEC procedure after a local recurrence following the initial operation. At operation, one patient was deemed ineligible because optimal cytoreduction could not be achieved, resulting in a total of 11 operations and 10 treatments with HIPEC. At exploration, median peritoneal cancer index was 8 (range 3–16). Demographics of the patients included in the analysis are detailed in Table 1.

Fig. 1 –

Clinical trial design and enrollment. *1 patient experienced recurrent disease and was re-enrolled for a second CRS and HIPEC procedure.

Table 1 –

Patient cohort demographics.

| Factor median (range) % | Median (range) | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 41 (24–58) | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 3 | 30 |

| Female | 7 | 70 |

| Tumor stage (AJCC) at diagnosis | ||

| I | 2 | 20 |

| II | 5 | 50 |

| III | 1 | 10 |

| IV | 0 | 0 |

| unknown | 2 | 20 |

| Functional tumor status | ||

| Non-functional | 4 | 40 |

| Functional | 6 | 60 |

| Type of resection | ||

| Open | 4 | 40 |

| Laparoscopic | 4 | 40 |

| Unknown | 2 | 20 |

| Prior resection margin | ||

| R0 | 7 | 78 |

| R1 | 2 | 22 |

| Unknown | 1 | 10 |

| DFI from initial resection (mo) | ||

| <12 | 0 | 0 |

| 12–24 | 5 | 50 |

| 25+ | 4 | 40 |

| Unknown* | 10 | 10 |

| Prior treatment: mitotane | ||

| No | 3 | 30 |

| Yes | 7 | 70 |

| Prior treatment: EDP | ||

| No | 8 | 80 |

| Yes | 2 | 22 |

| Prior treatment: radiation or RFA | ||

| No | 6 | 67 |

| Yes | 4 | 40 |

| Time between evidence of disease and HIPEC (y) | 1.25 | |

| Comorbidities | ||

| CAD | 0 | 0 |

| COPD/asthma | 1 | 10 |

| CKD | 0 | 0 |

| ECOG | ||

| 0 | 10 | 111 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 |

CAD = coronary artery disease; CKD = chronic kidney disease; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DFI = disease free interval; ECOG = Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; EDP = etoposide, doxorubicin, cisplatin; HPI = history of present illness; RFA = radiofrequency ablation.

Unclear from initial HPI, how long initial disease-free interval was.

Safety

Median operative time was 667 min (range 577–894 min) and was associated with median estimated blood loss 500 mL (range 150–2000 mL); no patients required reoperation (Table 2). Monitored care in intensive care unit was brief (median 2 d, range 2–4) and length of stay was less than 2 wk (median 10 d, range 8–13). There were no perioperative mortalities. Complications were all Clavien-Dindo grade 2 or 3. These included infectious complications (urinary tract infection, subcutaneous abscess), hematologic complications (anemia, thrombocytopenia), and neurologic complications (abdominal pain).

Table 2 –

Perioperative characteristics.

| Perioperative characteristics* | Median | Range/% |

|---|---|---|

| Sites of metastatic disease | ||

| Adrenal ed | 2 | 18.2 |

| Liver | 3 | 27.3 |

| Lung | 2 | 18.2 |

| Spleen | 1 | 9.1 |

| Retroperitoneal space | 6 | 54.5 |

| Diaphragm | 2 | 18.2 |

| Pelvis | 1 | 9.1 |

| Abdominal wall | 1 | 9.1 |

| Operative time (min) | 645 | (577–894) |

| Peritoneal cancer index status | ||

| Before CRS | 8 | (3–16) |

| After CRS | 0 | (0–6) |

| CCR score | 0 | (0–2) |

| Estimated blood loss (mL) | 500 | (150–2000) |

| Transfusion | ||

| Packed red blood cells | 2 | (0–8) |

| Fresh frozen plasma | 0 | (0–5) |

| platelets | 0 | (0–6) |

| Length of ICU stay (d) | 2 | (2–4) |

| Length of hospital stay (d) | 10 | (8–13) |

| Perioperative mortality | 0 | 0 |

| Perioperative morbidity | ||

| Cardiac events | 0 | 0 |

| Respiratory events | 0 | 0 |

| Acute kidney injury | 0 | 0 |

| Infection | 3 | 30 |

| Wound dehiscence | 1 | 10 |

ICU = intensive care unit.

Based on n = 11 patient treatments, including one patient who underwent cytoreduction alone.

QoL and survival

Data on QoL were available for all patients through 3 mo after surgery. Mean FACT-G score prior to intervention was 82.6. At 6 wk, mean FACT-G score had trended to 76.4 but recovered to 80.2 by 3 mo after surgery. Social well-being remained stable throughout follow-up. Functional well-being decreased (mean score 19 from 21, preoperatively), whereas emotional well-being increased (mean score 17 from 13, preoperatively) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2 –

FACT-G questionnaire QoL scores for cohort (median score shown).

At time of data analysis, median follow-up was 23 mo. Median IP-PFS was 19 mo (range 3–66 mo, Fig. 3). Seventy percent of treated patients experienced recurrent disease. Median overall survival has not yet been reached. At time of analysis, three patients had died due to disease. Univariate and multivariate analyses were not performed given the small sample size.

Fig. 3 –

(A) Overall survival of cohort (median survival not yet reached). (B) IP-PFS (median survival 19 mo).

Discussion

The current clinical trial examined the feasibility, safety, and efficacy of CRS with HIPEC in attaining local-regional tumor control for patients with local-regional recurrence of ACC. Cytoreduction and HIPEC was proposed to offer the benefit of tumor debulking with additional disease control via regional administration of chemotherapy, potentially enhancing the durability of recurrence-free survival afforded by cytoreduction alone. Although our study failed to meet target accrual, we believe the results of our trial add a potential tool to the multidisciplinary armamentarium for clinicians who often have no viable treatment to offer. It is possible that this strategy, in conjunction with serial metastasectomy, could result in prolonged survival for patients until more efficacious systemic therapy can be demonstrated.

Cytoreduction and HIPEC have been described in treatment of peritoneal metastasis due to colorectal, ovarian, mesothelial, gastric, and appendiceal malignancies. It is well-established that cytoreduction and HIPEC procedures have associated perioperative morbidities. Reported rates of postoperative morbidity and mortality vary widely depending upon study, with postoperative morbidity ranging from 12% to 62% and postoperative mortality ranging from 0.9% to 7.7%.17–21 Common complications include wound infection, sepsis, respiratory failure, anastomotic leak, pneumonia, and enterocutaneous fistulae.18,21 In our cohort, there was no perioperative mortality, and comorbidities were limited to moderate grade infectious, hematologic, and other perioperative sequelae (i.e., hoarsensess after intubation, abdominal pain). Therefore, cytoreduction and HIPEC appeared reasonably safe and tolerable for selected patients with recurrent ACC.

Treatment by cytoreduction and HIPEC achieved median IP-PFS of 19 mo in this study. It is challenging to compare this result with the heterogeneous outcome measures from the paucity of studies reporting surgical management of locally advanced or recurrent ACC. A study by Datrice et al.9 examined 57 patients with metastatic or recurrent ACC who underwent 116 procedures including 23 liver resections, 48 lung or thoracic resections, and 15 exploratory laparotomies for resection. Although detailed patient and treatment information were not available, the authors reported a median PFS of 6 mo in their cohort. In contrast, studies assessing disease-free interval after hepatectomy for liver metastases have reported median disease-free survival of 7 to 9.1 mo.8,22 Even though direct comparisons cannot be made, our findings suggest that cytoreduction and HIPEC may potentially impart longer IP-PFS when compared to metastasectomy alone.

Overall survival is the most meaningful outcome metric for evaluating patients with recurrent or metastatic ACC. The FIRM-ACT trial demonstrated no difference in overall survival between patients who were treated with streptozocinmitotane compared to combination chemotherapy (etoposide, doxorubicin, cisplatin, mitotane; 12 versus 13.8 mo). Prior surgical studies evaluating pulmonary metastasectomy for limited oligometastatic disease have reported overall survival rates ranging from 27 to 50.2 mo.9–12,23 Median overall survival had not yet been reached at the time of this analysis (median length of follow-up: 23 mo). While definitive conclusions regarding overall survival benefit from cytoreduction and HIPEC cannot be made, it appears that this intervention may be combined with systemic chemotherapy to offer improved survival. As such, cytoreduction and HIPEC could be considered for highly selected patients as an alternative to current systemic therapy.

The study limitations are worth noting. Accrual to this study was suboptimal. Despite evaluation of 63 patients for study eligibility, 53 were not eligible due to strict inclusion criteria (84%). Although our institution has served as a major referral center for patients with ACC, both the eligibility criteria and single-institution nature of the study likely contributed to poor patient accrual. Limited treatment numbers also hindered our ability to examine any patient or treatment factors associated with outcomes after cytoreduction and HIPEC. However, these issues are common to any study of a rare disease, particularly one in which surgical therapy is difficult to standardize.

This study demonstrates that patients can be treated safely with CRS and HIPEC and that prolonged IP-PFS can be achieved in selected patients. The frequency of recurrent disease and advanced stage at diagnosis make ACC particularly challenging to manage suggesting that tumor biology supersedes aggressive local therapy and that improved treatment options are desperately needed. Systemic therapy and metastasectomy may yield limited survival benefit, but there remain few viable treatment alternatives for patients with recurrent or advanced ACC. As such, novel treatment strategies for managing this disease merit exploration.

Acknowledgment

The authors gratefully acknowledge the clinical assistance of Tito Fojo, MD, PhD, Prakash Pandalai, MD, Udo Rudloff, MD, and Dan Zlott, PharmD, and the guidance of Seth Steinberg PhD in the statistical aspects of the protocol.

Funding:

This study was funded through the Intramural Research Program of the National Cancer Institute.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors reported no proprietary or commercial interest in any product mentioned or concept discussed in this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fassnacht M, Terzolo M, Allolio B, et al. Combination chemotherapy in advanced adrenocortical carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2012;366:2189–2197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Glover AR, Ip JC, Zhao JT, Soon PS, Robinson BG, Sidhu SB. Current management options for recurrent adrenocortical carcinoma. Onco Targets Ther 2013;6:635–643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bilimoria KY, Shen WT, Elaraj D, et al. Adrenocortical carcinoma in the United States: treatment utilization and prognostic factors. Cancer 2008;113:3130–3136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fassnacht M, Kroiss M, Allolio B. Update in adrenocortical carcinoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2013;98:4551–4564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fay AP, Elfiky A, Telo GH, et al. Adrenocortical carcinoma: the management of metastatic disease. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2014;92:123–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dy BM, Wise KB, Richards ML, et al. Operative intervention for recurrent adrenocortical cancer. Surgery 2013;154:1292–1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Erdogan I, Deutschbein T, Jurowich C, et al. The role of surgery in the management of recurrent adrenocortical carcinoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2013;98:181–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gaujoux S, Al-Ahmadie H, Allen PJ, et al. Resection of adrenocortical carcinoma liver metastasis: is it justified? Ann Surg Oncol 2012;19:2643–2651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Datrice NM, Langan RC, Ripley RT, et al. Operative management for recurrent and metastatic adrenocortical carcinoma. J Surg Oncol 2014;105:709–713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kemp CD, Ripley RT, Mathur A, et al. Pulmonary resection for metastatic adrenocortical carcinoma: the National Cancer Institute experience. Ann Thorac Surg 2011;92:1195–1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ripley RT, Kemp CD, Davis JL, et al. Liver resection and ablation for metastatic adrenocortical carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol 2011;18:1972–1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Op den Winkel J, Pfannschmidt J, Muley T, et al. Metastatic adrenocortical carcinoma: results of 56 pulmonary metastasectomies in 24 patients. Ann Thorac Surg 2011;92:1965–1970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Papotti M, Libe R, Duregon E, Volante M, Bertherat J, Tissier F. The Weiss Score and beyond – histopathology for adrenocortical carcinoma. Horm Cancer 2011;2:333–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schulick RD, Brennan MF. Long-term survival after complete resection and repeat resection in patients with adrenocortical carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol 1999;6:719–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Payabyab EC, Balasubramaniam S, Edgerly M, et al. Adrenocortical cancer: a molecularly complex disease where surgery matters. Clin Cancer Res 2016;22:4989–5000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levine EA, Stewart JH 4th, Shen P, Russell GB, Loggie BL, Votanopoulos KI. Cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy for peritoneal surface malignancy: experience with 1,000 patients. J Am Coll Surg 2014;218:573–585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alexander HR, Bartlett DL Jr, Pingpank JF, et al. Treatment factors associated with long-term survival following cytoreductive surgery and regional chemotherapy for patients with malignant peritoneal mesothelioma. Surgery 2013;153:779–786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levine EA, Stewart JH 4th, Shen P, Russell GB, Loggie BL, Votanopoulos KI. Intraperitoneal chemotherapy for peritoneal surface malignancy: experience with 1,000 patients. J Am Coll Surg 2014;218:573–585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ihemelandu CU, McQuellon R, Shen P, Stewart JH, Votanopoulos K, Levine EA. Predicting postoperative morbidity following cytoreductive surgery with HIPEC with preoperative FACT-C and patient-rated performance status. Ann Surg Oncol 2013;20:3519–3526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kusamara S, Younan R, Baratti D, et al. Cytoreductive surgery followed by intraperitoneal hyperthermic perfusion: analysis of morbidity and mortality in 209 peritoneal surface malignancies treated with closed abdomen technique. Cancer 2006;106:1144–1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alexander HR Jr, Bartlett DL, Pingpank JF, et al. Treatment factors associated with long-term survival after cytoreductive surgery and regional chemotherapy for patients with malignant peritoneal meothelioma. Surgery 2013;153:779–786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baur J, Buntemeyer TO, Megerle F, Deutschbein T. Outcome after resection of adrenocortical carcinoma liver metastases: a retrospective study. Cancer 2017;17:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bellatone R, Ferrante A, Boscherini M, et al. Role of reoperation in recurrence of adrenal cortical carcinoma: results of 188 cases collected in the Italian National Registry for Adrenal Cortical Carcinoma. Surgery 1997;122:1212–1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]