Abstract

To perform a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) for investigating the effect of dietary treatment and fluid intake on the prevention of recurrent calcium stones and changes in urine composition. PubMed, Web of Science, Embase, EBSCO, and Cochrane Library databases (updated November 2020) were searched for studies with the following keywords: diet, fluid, recurrent, prevention, randomized controlled trials, and nephrolithiasis. The search strategy and study selection process was conducted by following the PRISMA statement. Six RCTs were identified for satisfying the inclusion criteria and enrolled in this meta-analysis. Our result showed that low protein with or without high fiber diet intervention does not decrease the recurrence of stone upon comparing with control groups (RR = 2.32, 95% CI = 0.42–12.85; P = 0.34) with significant heterogeneity among the studies (I2 = 81%, P = 0.02). But normal-calcium, low protein, low-salt diet had recurrences did reduced the recurrence compared to normal-calcium diet. And the fluid intake has a positive effect on prevention of recurrent stone formation (RR = 0.39, 95% CI = 0.19–0.80; P = 0.01) with insignificant heterogeneity among the studies (I2 = 9%, P = 0.30). The different components of urine at baseline were reported in four studies. Upon reviewing the low protein with or without high fiber dietary therapy groups, it was found that there were no obvious changes in the 24-hour urine sodium, calcium, citrate, urea, and sulfate. In conclusion, our study shows that the only low protein with or without fiber does not affect recurrence, but low Na, normal Ca diet has a marked effect on reducing recurrence of calcium stone. And fluid intake shows a significant reduction in the recurrence of calcium stone.

Introduction

Nephrolithiasis or urolithiasis is the third most common disease of the urinary tract that becomes more prevalent over the past decades [1, 2]. The worldwide kidney stone prevalence rate is 1.7% to 8.8% costs about $2.1 billion in 2020 [3, 4]. Patients with nephrolithiasis often suffer from short-term complications such as acute renal colic, nausea, vomiting, and hematuria, and long-term complications such as chronic renal failure and hydronephrosis [5]. Furthermore, it is often associated with an incidence of recurrence after an initial event of 30% to 50% without prevention [6]. Therefore, to minimize the morbidity of nephrolithiasis, the reduction in calculi recurrence after the surgical clearance of stones is crucial.

The stones are mainly composed of 4 types of components—calcium oxalate, uric acid, calcium phosphate, and struvite, with calcium stones being the most common type [7]. The present study shows that the mechanism of stone formation is mainly based on metabolic defects which are combined from both genetic and nutritional factors [8]. Present efforts to prevent the recurrence of stones are mainly focus on changing the eurine compositions and decreasing concentrations of the lithogenic factors [9]. Currently, medication has a therapeutic effect on the prevention of recurrent stone formation by increasing renal calcium reabsorption, decreasing gut calcium absorption, chelating calcium in the urine or poisoning calcium crystal surfaces. Nevertheless, there are some associated side effects including gastrointestinal reaction, changes in blood pressure, and fluid/electrolyte imbalance [10]. Thus, some life-related prevention has been applied due to its high compliance and low side effects benefits [11]. To reduce calcium stone recurrence, preventive strategies targeting modifiable diet structure may be effective.

Previous studies have shown that formation of a renal stone is closely related to dietary regimes [12, 13]. Nevertheless, the higher evidence-based study like systematic review of clinical value in dietary therapy in urinary stone recurrence is still lacked. Furthermore, new studies with more detailed data at high evidence level are reported. Thus, we performed this systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) for investigating the effects of dietary treatment and fluid intake on the prevention of recurrent calcium stones and changes in urine composition.

Materials and methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis followed the guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) statement and the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [14]. Ethical approval and patient consent were not required as all the analyses were based on previously published studies.

Literature search and selection criteria

We systematically searched several databases including PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, EBSCO, and the Cochrane Library from the inception until November 2020 with the following keywords: diet, fluid, recurrent, prevention, randomized controlled trials, and nephrolithiasis. The reference list of retrieved studies and relevant reviews were hand-searched, and the process mentioned above was repeatedly performed for ensuring that all eligible studies were included. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) RCTs study design, (2) The patient had a stone history and was diagnosed by surgical removal, stone passage, or by imaging systems, (3) the intervention was diet or water intake, (4) adequate reporting of data provided for analysis, and (5) availability of the full text. All languages were included.

Data extraction and outcome measures

Baseline information extracted from the original studies includes the first author, published year, number of patients, patient age and gender distributions, type of calcium stone, and detailed methods for the two groups, and the evaluation of evidence level. Data were independently extracted by two investigators and the discrepancies were resolved by consensus. The primary outcomes were stone recurrence and withdrawal rate. The secondary outcomes were the variables of urine composition.

Quality assessment of individual studies

All assessments were performed independently by two researchers with the differences resolved by the third researcher. the domain-based evaluation recommended by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Intervention were used to address the following domains: bias arising from the randomisation process, bias due to deviations from intended interventions, bias due to missing outcome data, bias in measurement of the outcome and bias in selection of the reported result [15]. Figure of ‘Risk of Bias’ assessment were made by using Review Manager Software Version 5.3 (The Cochrane Collaboration, Software Update, Oxford, UK).

Statistical analysis

Risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) was calculated for dichotomous outcomes and heterogeneity was evaluated using the I2 statistic, with I2 > 50% indicating significant heterogeneity [16]. Sensitivity analysis was performed for evaluating the influence of a single study on the overall estimate by omitting one study or by performing subgroup analysis. The random-effects model was used for meta-analysis. Owing to the limited number of included studies (<10), publication bias was not assessed. Statistical significance was accepted at P < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using Review Manager Software Version 5.3 (The Cochrane Collaboration, Software Update, Oxford, UK).

Results

Literature search, study characteristics, and quality assessment

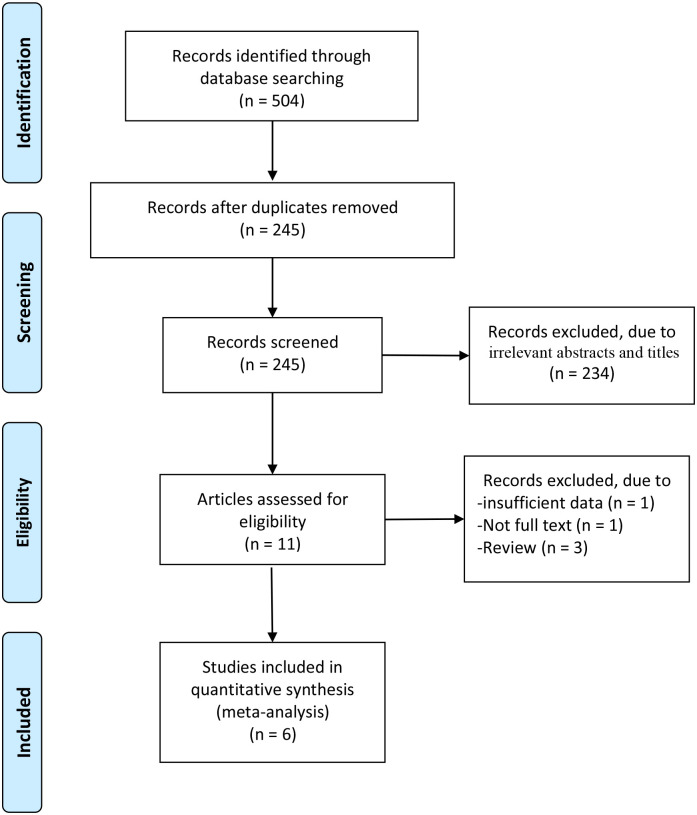

A total of 71 articles were initially identified from the database search. After the removal of duplicates, 45 articles were retained. Of these, 34 were excluded from analysis following the screening of the abstracts and titles, three were excluded as they were review articles, one was excluded because of insufficient data, and one was excluded because of the unavailability of the full text. Finally, six RCTs were identified as those satisfying the inclusion criteria and were finally enrolled in this meta-analysis [17–22]. The article selection process was performed by following the PRISMA guidelines (Fig 1). Baseline characteristics of the six included RCTs are shown in Table 1. These studies were published between 1996 and 2008, and the total sample size was 824.

Fig 1. Flow diagram of study searching and selection process.

Table 1. Characteristics of included studies.

| No. | Author | year | Experimental group | Control group | Follow up time(year) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number (n) | Age (Mean±SD) | Male (n) | Type of stone | Method | Number (n) | Age (Mean±SD) | Male (n) | Stone type | Method | ||||

| 1 | Dussol | 2008 | 115 | 44±12 | 60 | Calcium oxalate | 55 patients receive low doses protein (<15% of total energy) and 65 patients receive high doses fiber(>25g) per day | 63 | 45±11 | 38 | Calcium oxalate | Normal diet | 4 |

| 2 | Sarica | 2006 | 12 | - | - | Calcium oxalate | Enforced fluid intake (achieve to more than 2.5 liters of urine per day) | 9 | - | - | Calcium oxalate | Nomal diet | 3 |

| 3 | Borghi | 2002 | 60 | 44.8±9.2 | 60 | Calcium oxalate/ Calcium phosphate | Normal Ca with reduced protein 52g/d and salt 50 mmol/d | 60 | 45.4±10.9 | 60 | Calcium oxalate | Traditional low Ca diet | 5 |

| 4 | Kocvara | 1999 | 113 | 18–72 | 59 | Calcium stone | Special dietary regimens with low proteins, purine, oxalate and high fiber. | 94 | 18–72 | 37 | Calcium stone | Normal diet | 3 |

| 5 | Hiatt | 1996 | 50 | 43.1±1.5 | 36 | Calcium oxalate | 56–64 g/d protein, 75 mg/d purine, fiber supplement and 6–8 glasses of water | 49 | 42.9 ± 1.4 | 42 | Calcium oxalate | Fluid intake | 4.5 |

| 6 | Borghi | 1996 | 99 | 42.2±11.6 | 70 | Calcium oxalate | Enforced fluid intake (achieve to more than 2 liters of urine per day) | 100 | 40.4± 13.2 | 60 | Calcium stone | Normal diet | 5 |

Interventions of four studies take the dietary method [17, 19–21]. The study by Dussol et al. has two subgroups: low animal protein and high fiber. Patients in the study by Borghi et al. received a low protein and low salt diet [19]. Kocvara et al. take a special regime based on a metabolic evaluation which involves low protein, purine, oxalate, and high fiber [20]. Hiatt et al. compared the low protein and purine with fluid intake only [21]. The other two studies take water intake to make the urine volume higher than 2 L and 2.5 L, respectively [18, 22].

Quality assessment of included studies

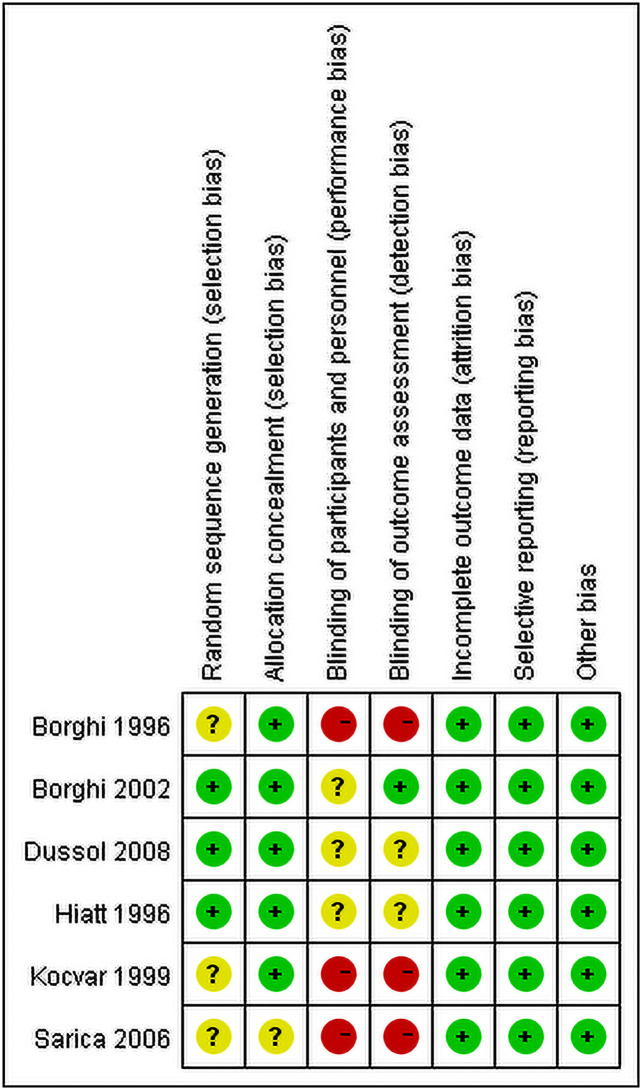

All studies had low risk bias in incomplete outcome data, selective reporting and other issues. Three studies [18, 20, 22] had high risk in blindness and random sequence generation while the other three studies [17, 19, 21] were not which is shown Fig 2.

Fig 2. Risk of bias assessment in included studies.

Primary outcome: Recurrence rate and withdrawal rate

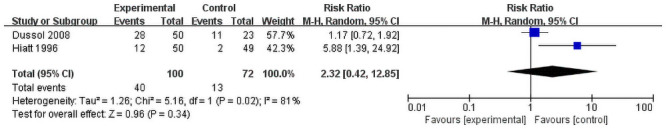

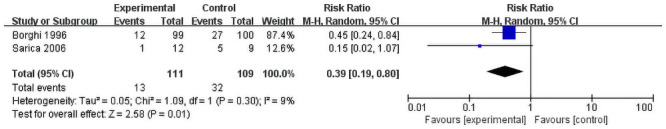

Totally Four studies reported the recurrence of the stones by the dietary method [17, 19–21] and two by the fluid method [18, 22]. Due to interventions for control group of Kocvara et al. [20] are tailored. Therefore, their result of recurrence rate cannot compare with Hiatt et al. and Dussol et al. And Borghi et al reported normal-calcium, low protein, low-salt diet had recurrences did reduced the recurrence compared to normal-calcium diet (12/60 vs 20/60; RR = 0.49, 95%CI = 0.24–0.98) [19]. And, only two studies [17, 21] were included to evaluate the effect of only trials of low protein with or without high fiber diet method. A random-effects model was used for analyzing the primary outcomes. Our result showed that dietary intervention does not decrease the recurrence of stone upon comparing with control groups (RR = 2.32, 95% CI = 0.42–12.85; P = 0.34) with significant heterogeneity among the studies (I2 = 81%, P = 0.02) (Fig 3). However, the fluid intake was found to have a positive effect on the prevention of stone recurrence (RR = 0.39, 95% CI = 0.19–0.80; P = 0.01) with insignificant heterogeneity among the studies (I2 = 9%, P = 0.30, Fig 4).

Fig 3. Forest plot for the meta-analysis of recurrence of only low protein with or without high fiberdiet.

Fig 4. Forest plot for the meta-analysis of recurrence rate of liquid intake.

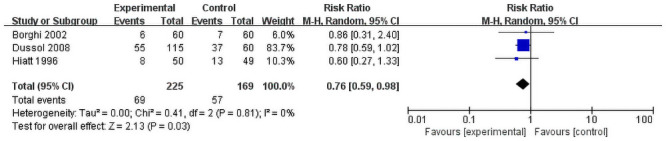

Three dietary groups reported the rate of withdrawal of patients. Though the result is statistically insignificant (RR = 0.76, 95% CI = 0.59–0.98; P = 0.03) insignificant heterogeneity was observed among the studies (I2 = 0%, P = 0.81, Fig 5). All the studies showed that intervention groups have a higher withdrawal rate. All patients in fluid intervention froup finish the follow up.

Fig 5. Forest plot for the meta-analysis of withdraw rate.

Secondary outcome: Variables of urine composition

The Urinary variables at baseline were reported in four studies [17–20]. The urine volume was reported in all four studies and one fluid intake group were changed significantly. The 24-hour urine sodium, calcium, citrate, urea, and sulfate were reviewed in other dietary therapy groups. Borghi et al. reported urine sodium and oxalate changed in their study as their was a unique one which provided both low protein and low salt [19]. And Kocvara et al. showed that calcium and oxalate changed in their study [20]. Two studies reported the relative oxalate saturation and both their changes are significant [18, 19].

Sensitivity analysis

Among all outcomes, the dietary intervention showed a significant heterogeneity (I2 = 81%, P = 0.02). The heterogeneity may come from the study design as the specific dose of protein are different.

Discussion

Prevention of kidney stone recurrence is very complex and controversial. A cohort study showed that about half of the nephrolithiasis were ascribed to lifestyle factors [11]. Particularly, diet interventions were assumed as an efficient technique to prevent urinary stone formation and its recurrence. However, due to the lack of high-quality original research, no conclusive consensus or guideline was drawn for the effect of secondary prevention for stone formation [23]. Here, we conducted this study to review the RCTs reporting the effects of different dietary interventions for the prevention of recurrent stone formation and the changes in urine compositions in patients with urinary stone disease.

The results of this study indicate that water intake can reduce stone recurrence. Meanwhile low protein with or without fiber does not affect recurrence, but low Na, normal Ca diet has a marked reduction effect on recurrence. All included studies use reduced protein intake for patients as an intervention process. Higher animal protein intake may result in decreased citrate and urine PH and increased urinary excretion of calcium and uric acid which may potentially favor the formation of stones [24]. But the present study unexpectedly contradicted this hypothesis. In one subgroup of the study by Dussol et al., the only intervention is the restriction of the consumption of animal protein, but the recurrence rate was 48% (11 of 23) in the intervention group which is almost the same as that for the control group (48%;11 of 23) [17]. Also, Hiatt et al. reported that dietary intervention combining low protein, high fiber, and fluid intake has no advantage compared to fluid intake only [21]. An alternative explanation is that different types of protein may affect the recurrence of kidney stones differently. One large cohort study showed that red and processed meats increase the risk of stone formation than other animal or vegetable protein [25]. This is difficult to control in long-term RCTs. Furthermore, protein intake causes an increase in excretion of lithogenic materials such as calcium oxalate, sulfate, and uric acid, and causes a reduction in the excretion of citrate [26, 27]. But our study shows that these changes are not obvious (Table 2). Not all stone formation compositions of the urine increase correspondingly and urine citrate decreased statistically insignificant. This may suggest that low-protein intake is not low enough to provide the desired effect. Dussol et al. assumed that their intervention with low animal protein (17% total energy) is not low enough compared to the people who often follow a Mediterranean diet that is relatively poor in animal protein [17]. However, Borghi et al. added low Na with normal Ca in diet reduced the probability of stone recurrence which indicated the positive effect of low Na for prevention the stone [19].

Table 2. Urinary compositions variables in baseline and the long term follow up.

| Study | Follow up | Method | Urine volume (L/day) | Sodium (mmol/day) | Calcium (mmol/day) | Oxalate (mmol/day) | Citrate (mmol/day) | Urea (mmol/day) | Sulfate (mmol/day) | Relative oxalate saturation | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Result | Baseline | Result | Baseline | Result | Baseline | Result | Baseline | Result | Baseline | Result | Baseline | Result | Baseline | Result | |||

| Dussol | 3 year | Low protein | 1.8±0.6 | 1.9±0.8 | 149±44 | 171±71 | 6.8±3.1 | 7.0±3.5 | 0.30±0.1 | 0.29±0.1 | 2.9±1.9 | 2.9±1.5 | 381±95 | 359±135 | 4.3±1.9 | 3.1±2.4 | ||

| High fiber | 2.0±0.7 | 1.8±0.6 | 163±58 | 154±55 | 6.9±3.7 | 7.0±3.5 | 0.31±0.2 | 0.32±0.1 | 3.3±3.2 | 2.1±1.2 | 354±93 | 361±117 | 4.6±2.8 | 4.8±3.6 | ||||

| Borghi | 3 year | Low protein Low salt | 1.9±6.7 | 2.1±5.2 | 205±64 | 127±66b | 7.0±3.4 | 6.6±2.4 | 0.42±0.1 | 0.33±0.1b | 505±142 | 447±113 | 2.8±0.8 | 2.5±0.6 | 6.7±4.5 | 4.5±2.9a | ||

| Kocvara | 3 year | Special diet | 2.4±6.5 | 2.4±6.5 | 5.1±2.4 | 6.4±2.8b | 0.35±0.2 | 0.42±0.2a | 3.0±1.5 | 3.2±1.9 | ||||||||

| Borghi | 5 year | Fluid intake | 1.1±0.2 | 2.6±0.7b | 1.8±1.7 | 1.2±1.0b | ||||||||||||

a: P<0.05 compared to the baseline;

b:P<0.01 compared to the baseline

The definition of “low” for “low protein” is still unclear. Another reason is that each patient’s daily diet structure is complex as a low protein diet may change the urine composition in a very short follow-up period but may not in an interventional long-term trial. Furthermore, specific dietary instructions should be corrected according to repeated metabolic measurements and low protein intake could produce other metabolic disorders [12]. Kocvara et al. found a positive result in their study as each patient underwent a personalized metabolic assessment and specific diet regime. And patients with hypercalciuria and hyperuricemia took a low protein diet can significantly reduce the recurrence of stones [20]. Rotily et al. also found in a 24-hour urine composition analysis that patients with hypercalciuria benefit more from a low protein diet as the urea and calcium outputs were observed only among hypercalciuria patients [28]. Therefore, we can conclude that a low-protein diet does not prevent the recurrence of stones in all patients, but it may benefit patients with hypercalciuria. Thus, metabolic evaluation is strongly recommended for patients before choosing low protein diet therapy. The withdrawal rate in low protein is higher than in the control group. Also, Dussol et al. and Borghi et al. reported that the rate of unwillingness for withdrawal patients to continue the therapy is also higher which indicates poor patient compliance though it is statistically insignificant [17, 19].

Our results show that an increase in dietary fiber intake failed to reduce the recurrence rate of calcium oxalate stones. In the study by Dussol et al., the subgroup taking a high diet only did not succeed in the prevention of recurrence as well as the changes in urine composition [17]. This result is similar to the study by Rotily et al. in which the patients with dietary fiber intake do not reduce the predictive factors of calcium oxalate such as calcium or oxalate outputs [28]. Haitt et al. found that a combination of high fiber and low protein diet did not reduce stone recurrence [21]. Phytate in fibers can reduce hypercalciuria by forming complex molecules with calcium in the gut [29]. Therefore, fiber-rich foods can decrease calcium oxalate supersaturation and increase citrate excretion [30]. Nevertheless, intestinal complexation of calcium might lead to hyperoxaluria [31]. So, the overall effect of high fiber in preventing the recurrence of calcium oxalate stones is unclear. An observational study by Hirvonen et al. showed that a fiber-rich diet may increase the recurrence of kidney stones [32]. Other results of recent cohort studies reported fiber-rich diet might reduced recurrence or no relation for stone formation [33, 34]. The results that fluid intake reduced stone recurrence were not surprising. Increased fluid intake may help prevent the formation of stones by diluting urine components and decreasing urine acidity which is well learned and suggested as the first prevention step for urolithiasis [35]. This concept is consistent with the results of Borghi et al. which showed a significant reduction in the relative supersaturation of calcium oxalate, brushite, and uric acid [18]. It is worth noting that there is no withdrawal patient in two fluid intake groups indicating that water intake is highly associated with patient compliance.

There are a few limitations associated with this study. Firstly, the heterogeneity of dietary prevention is high due to the variation in the intervention standards in the study design. Secondly, the impact of dietary factors on stone recurrence varies from age, gender, race, and region remained unknown due to the lack of related studies. Lastly, the accuracy of our summary may be skewed as there are publication biases due to some unpublished data.

In conclusion, our study shows that the only low protein with or without fiber does not affect recurrence, but low Na, normal Ca diet has a marked effect on reducing recurrence of calcium stone. And fluid intake shows a significant reduction in the recurrence of calcium stone.

Supporting information

(DOC)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting information files.

Funding Statement

The authors received no specific funds for this work.

References

- 1.Türk C, Petřík A, Sarica K, Seitz C, Skolarikos A, Straub M, et al. EAU Guidelines on Diagnosis and Conservative Management of Urolithiasis. Eur Urol. 2016;69(3):468–74. Epub 2015/09/01. 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.07.040 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bouatia M, Benramdane L, Idrissi MOB, Draoui M. An epidemiological study on the composition of urinary stones in Morocco in relation to age and sex. African Journal of Urology. 2015;21(3):194–7. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Antonelli JA, Maalouf NM, Pearle MS, Lotan Y. Use of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey to calculate the impact of obesity and diabetes on cost and prevalence of urolithiasis in 2030. Eur Urol. 2014;66(4):724–9. Epub 2014/07/13. 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.06.036 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scales CD Jr., Smith AC, Hanley JM, Saigal CS. Prevalence of kidney stones in the United States. Eur Urol. 2012;62(1):160–5. Epub 2012/04/14. 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.03.052 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Torricelli FCM, Monga M. Staghorn renal stones: what the urologist needs to know. International braz j urol: official journal of the Brazilian Society of Urology. 2020;46(6):927–33. Epub 2020/03/28. 10.1590/s1677-5538.ibju.2020.99.07 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Romero V, Akpinar H, Assimos DG. Kidney stones: a global picture of prevalence, incidence, and associated risk factors. Rev Urol. 2010;12(2–3):e86–96. Epub 2010/09/03. . [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu Y, Chen Y, Liao B, Luo D, Zeng G. Epidemiology of urolithiasis in Asia. Asian Journal of Urology. 2018:S2214388218300729-. 10.1016/j.ajur.2018.08.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ljunghall S, Danielson BG. A prospective study of renal stone recurrences. Br J Urol. 1984;56(2):122–4. Epub 1984/04/01. 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1984.tb05346.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Qaseem A, Dallas P, Forciea MA, Starkey M, Denberg TD. Dietary and pharmacologic management to prevent recurrent nephrolithiasis in adults: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(9):659–67. Epub 2014/11/05. 10.7326/M13-2908 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Escribano J, Balaguer A, Pagone F, Feliu A, Roqué IFM. Pharmacological interventions for preventing complications in idiopathic hypercalciuria. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;2009(1):Cd004754. Epub 2009/01/23. 10.1002/14651858.CD004754.pub2 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferraro PM, Taylor EN, Gambaro G, Curhan GC. Dietary and Lifestyle Risk Factors Associated with Incident Kidney Stones in Men and Women. J Urol. 2017;198(4):858–63. Epub 2017/04/04. 10.1016/j.juro.2017.03.124 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parivar F, Low RK, Stoller ML. The influence of diet on urinary stone disease. J Urol. 1996;155(2):432–40. Epub 1996/02/01. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stoller ML, Chi T, Eisner BH, Shami G, Gentle DL. Changes in urinary stone risk factors in hypocitraturic calcium oxalate stone formers treated with dietary sodium supplementation. J Urol. 2009;181(3):1140–4. Epub 2009/01/21. 10.1016/j.juro.2008.11.020 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS medicine. 2009;6(7):e1000100. Epub 2009/07/22. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100 Oxford Radcliffe Hospitals Trust on behalf of the Department of Health and the National Institute for Health Research in England. This is a fixed term contract, the renewal of which is dependent upon the value placed upon his work, that of the UK Cochrane Centre, and of The Cochrane Collaboration more widely by the Department of Health. His work involves the conduct of systematic reviews and the support of the conduct and use of systematic reviews. Therefore, work–such as this manuscript–relating to systematic reviews might have an impact on his employment. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Chandler J, Welch VA, Higgins JP, et al. Updated guidance for trusted systematic reviews: a new edition of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;10:Ed000142. Epub 2019/10/24. 10.1002/14651858.ED000142 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21(11):1539–58. Epub 2002/07/12. 10.1002/sim.1186 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dussol B, Iovanna C, Rotily M, Morange S, Leonetti F, Dupuy P, et al. A randomized trial of low-animal-protein or high-fiber diets for secondary prevention of calcium nephrolithiasis. Nephron Clinical practice. 2008;110(3):c185–94. Epub 2008/10/30. 10.1159/000167271 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Borghi L, Meschi T, Amato F, Briganti A, Novarini A, Giannini A. Urinary volume, water and recurrences in idiopathic calcium nephrolithiasis: a 5-year randomized prospective study. J Urol. 1996;155(3):839–43. Epub 1996/03/01. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Borghi L, Schianchi T, Meschi T, Guerra A, Allegri F, Maggiore U, et al. Comparison of two diets for the prevention of recurrent stones in idiopathic hypercalciuria. The New England journal of medicine. 2002;346(2):77–84. Epub 2002/01/11. 10.1056/NEJMoa010369 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kocvara R, Plasgura P, Petrík A, Louzenský G, Bartonícková K, Dvorácek J. A prospective study of nonmedical prophylaxis after a first kidney stone. BJU Int. 1999;84(4):393–8. Epub 1999/09/01. 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1999.00216.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hiatt RA, Ettinger B, Caan B, Quesenberry CP Jr., Duncan D, Citron JT. Randomized controlled trial of a low animal protein, high fiber diet in the prevention of recurrent calcium oxalate kidney stones. American journal of epidemiology. 1996;144(1):25–33. Epub 1996/07/01. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a008851 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sarica K, Inal Y, Erturhan S, Yağci F. The effect of calcium channel blockers on stone regrowth and recurrence after shock wave lithotripsy. Urol Res. 2006;34(3):184–9. Epub 2006/02/08. 10.1007/s00240-006-0040-x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prezioso D, Strazzullo P, Lotti T, Bianchi G, Borghi L, Caione P, et al. Dietary treatment of urinary risk factors for renal stone formation. A review of CLU Working Group. Archivio italiano di urologia, andrologia: organo ufficiale [di] Societa italiana di ecografia urologica e nefrologica. 2015;87(2):105–20. Epub 2015/07/08. 10.4081/aiua.2015.2.105 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Breslau NA, Brinkley L, Hill KD, Pak CY. Relationship of animal protein-rich diet to kidney stone formation and calcium metabolism. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 1988;66(1):140–6. Epub 1988/01/01. 10.1210/jcem-66-1-140 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taylor EN, Fung TT, Curhan GC. DASH-style diet associates with reduced risk for kidney stones. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology: JASN. 2009;20(10):2253–9. Epub 2009/08/15. 10.1681/ASN.2009030276 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wasserstein AG, Stolley PD, Soper KA, Goldfarb S, Maislin G, Agus Z. Case-control study of risk factors for idiopathic calcium nephrolithiasis. Mineral and electrolyte metabolism. 1987;13(2):85–95. Epub 1987/01/01. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nguyen QV, Kälin A, Drouve U, Casez JP, Jaeger P. Sensitivity to meat protein intake and hyperoxaluria in idiopathic calcium stone formers. Kidney Int. 2001;59(6):2273–81. Epub 2001/05/31. 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00744.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rotily M, Léonetti F, Iovanna C, Berthezene P, Dupuy P, Vazi A, et al. Effects of low animal protein or high-fiber diets on urine composition in calcium nephrolithiasis. Kidney Int. 2000;57(3):1115–23. Epub 2000/03/18. 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00939.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ebisuno S, Morimoto S, Yasukawa S, Ohkawa T. Results of long-term rice bran treatment on stone recurrence in hypercalciuric patients. Br J Urol. 1991;67(3):237–40. Epub 1991/03/01. 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1991.tb15125.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shah PJ, Williams G, Green NA. Idiopathic hypercalciuria: its control with unprocessed bran. Br J Urol. 1980;52(6):426–9. Epub 1980/12/01. 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1980.tb03082.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jahnen A, Heynck H, Gertz B, Classen A, Hesse A. Dietary fibre: the effectiveness of a high bran intake in reducing renal calcium excretion. Urol Res. 1992;20(1):3–6. Epub 1992/01/01. 10.1007/BF00294326 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hirvonen T, Pietinen P, Virtanen M, Albanes D, Virtamo J. Nutrient intake and use of beverages and the risk of kidney stones among male smokers. American journal of epidemiology. 1999;150(2):187–94. Epub 1999/07/21. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009979 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Curhan GC, Willett WC, Knight EL, Stampfer MJ. Dietary factors and the risk of incident kidney stones in younger women: Nurses’ Health Study II. Archives of internal medicine. 2004;164(8):885–91. Epub 2004/04/28. 10.1001/archinte.164.8.885 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Taylor EN, Stampfer MJ, Curhan GC. Dietary factors and the risk of incident kidney stones in men: new insights after 14 years of follow-up. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology: JASN. 2004;15(12):3225–32. Epub 2004/12/08. 10.1097/01.ASN.0000146012.44570.20 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Curhan GC, Willett WC, Speizer FE, Stampfer MJ. Beverage use and risk for kidney stones in women. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128(7):534–40. Epub 1998/06/10. 10.7326/0003-4819-128-7-199804010-00003 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]