Abstract

This 15-year longitudinal follow-up of a randomized controlled trial of a parenting-focused preventive intervention for divorced families examined cascade models of program effects on offsprings’ competence. It was hypothesized that intervention-induced improvements in parenting would lead to better academic, work, peer, and romantic competence in emerging adulthood through effects on behavior problems and competencies during adolescence. Families (N = 240) participated in the 11-session program or literature control condition when children were ages 9–12. Data were drawn from assessments at pretest, posttest, and follow-ups at 3 and 6 months and 6 and 15 years. Results showed that initial intervention effects of parenting on externalizing problems in adolescence cascaded to work outcomes in adulthood. Parenting effects also directly impacted work success. For work outcomes and peer competence, intervention effects were moderated by initial risk level; the program had greater effects on youths with higher risk at program entry. In addition, intervention effects on parenting led to fewer externalizing problems that in turn cascaded to better academic outcomes, which showed continuity into emerging adulthood. Results highlight the potential for intervention effects of the New Beginnings Program to cascade over time to affect adult competence in multiple domains, particularly for high-risk youths.

Keywords: cascade effects, competence, divorce, emerging adulthood, parenting-after-divorce programs

Although the rate of divorce has decreased since the 1980s (National Center for Health Statistics, 2008), it is estimated that 1.1 million children in the United States experience divorce each year (Kreider & Ellis, 2011). Compelling evidence has shown that this transition in family structure confers risk for multiple problems in childhood and adolescence including impairments in academic (Amato & Anthony, 2014; Strohschein, Roos, & Brownell, 2009) and social competence (Amato, 2001), mental health problems (Amato, 2001; Kim, 2011), problematic substance use (Brown & Rinelli, 2010), early sexual activity (Donahue et al., 2010), and suicide attempts (Weitoft, Hjern, Haglund, & Rosén, 2003).

For a sizeable number of offspring, the effects of parental divorce continue into adulthood, with some research indicating that differences between offspring in two-parent versus divorced families widen from childhood to adulthood (Cherlin, Chase-Lansdale, & McRae, 1998). Compared with adults who are raised in two-parent families, those from divorced families are more likely to experience difficulties in several domains of functioning. Specifically, adults who experienced parental divorce in childhood have lower educational and occupational attainment (Larson & Halfon, 2013), poorer marital quality (Amato, 2006), higher rates of divorce (Gähler, Hong, & Bernhardt, 2009), and lower quality peer relationships (Kunz, 2001). They also have increased rates of problematic substance use (Barrett & Turner, 2006), more mental (Kessler et al., 2010) and physical health problems (Lacey, Kumari, & McMunn, 2013) and earlier mortality (Larson & Halfon, 2013).

Several research groups have developed interventions that are designed to reduce or prevent the problems that are associated with parental divorce. Randomized trials have shown short-term effects of parent- and child-focused interventions on externalizing problems, noncompliance, anxiety, and learning problems (Forgatch & DeGarmo, 1999; Pedro-Carroll & Cowen, 1985; Sandler et al., 2019; Stolberg & Mahler, 1994; Wolchik et al., 1993, 2000). Although less studied, positive short-term effects on peer social competence and academic performance have been reported in two trials (Crosbie-Burnett & Newcomer, 1990; Pedro-Carroll & Cowen, 1985).

The limited research on the longer-term effects of these programs has focused almost exclusively on problem outcomes. Forgatch, Patterson, DeGarmo, and Beldavs (2009) found that a parenting-focused program that was delivered in childhood reduced delinquency and arrests nine years after participation. Wolchik et al. (2002) found significant effects of a parenting-focused intervention 6 years after participation on multiple problem outcomes including externalizing problems, internalizing problems, alcohol use, drug use, and number of sexual partners when offspring were 15 to 19 years old. Program effects also occurred on multiple aspects of competence at the 6-year follow-up, including higher grade point average, more adaptive coping, higher self-esteem, and higher expectations about educational goals and job aspirations (Sigal, Wolchik, Tein, & Sandler, 2012; Wolchik et al., 2002, 2007). Several of these effects were moderated by level of risk, with greater benefits occurring for those who entered the program at higher risk. At the 15-year follow-up, when the offspring were emerging adults (ages 24 through 28), this intervention led to a lower incidence of internalizing disorders (Wolchik et al., 2013) and less involvement with the criminal justice system (Herman et al., 2015). For males, program effects also occurred on drug use and substance use disorders (Wolchik et al., 2013). In addition, the program led to fewer problematic beliefs about divorce (Christopher et al., 2017) and for males, more negative attitudes toward divorce (Wolchik, Christopher, Tein, Rhodes & Sandler, 2019). In the only study to examine the effects of programs for divorced families on outcomes related to the developmental tasks of adulthood, Mahrer, Winslow, Wolchik, Tein and Sandler (2014) reported effects on positive attitudes toward parenting among the emerging adults in this cohort at the 15-year follow-up.

Examining the effects of prevention programs for divorced families on other aspects of competence in emerging adulthood is important given the many changes that occur in social and contextual roles and the multiple life choices that are being made during this period (Arnett & Tanner, 2006; Schulenberg, Sameroff, & Cicchetti, 2004). The consequences that are associated with competence become more significant and enduring as young people settle into the tasks of adulthood (Newman et al., 1996). For example, choices are made that can have a substantial influence on one’s life course, such as investment in work or education and choice of romantic partners (Arnett & Tanner, 2006; Elder, 2002).

Although parental divorce is associated with impairments in the accomplishment of the salient developmental tasks of adulthood, researchers have not addressed whether prevention programs for divorced families affect the salient developmental tasks of emerging adulthood, most notably work, academic, social, and romantic competence. A few comprehensive prevention programs for other populations have shown positive program effects on various domains of adult competence such as educational attainment, occupational prestige, employment, and emotion regulation in adulthood (Campbell, Ramey, Pungello, Sparling, & Miller-Johnson, 2002; Hawkins, Kosterman, Catalano, Hill, & Abbott, 2005, 2008; Hill et al., 2014; Reynolds et al., 2007; Reynolds & Ou, 2011; Schweinhart et al., 2005). However, all of these programs lasted a year or more. It is unknown whether much shorter prevention programs influence competence in adulthood. Evidence of long-term program effects on outcomes that have financial benefits, such as academic performance and work competence (Day & Newburger, 2002; Trevor, Gerhart, & Boudreau, 1997; Wolla & Sullivan, 2017) could demonstrate a high return on investment, thereby leveraging support for implementing such programs. In addition, studying the associations between program-induced changes earlier in development and competence in later stages of development can advance theory about the spreading effects of interventions across development and identify the pathways through which prevention programs influence later outcomes (Coie et al., 1993; Reynolds & Ou, 2016).

Interventions with parents or families that are intended to trigger positive and progressive effects over time offer compelling experimental tests of cascade models that are based on developmental systems theory as well as resilience theory (Masten & Cicchetti, 2010). Parenting can be viewed as a leverage point for changing children’s behaviors and attitudes, with effects that spread across time, domains of function, and systems (Doty, Davis, & Arditti, 2017; Masten & Palmer, 2019).

The current study examines the effects of the New Beginnings Program, a relatively brief (11-session) parenting-focused program for divorced families, on competence in early adulthood. The conceptual model underlying the development of the New Beginnings Program drew from the risk and protective factor and person–environment transactional frameworks (IOM, 1990; Sameroff, 1987). The risk and protective factor model posits that the likelihood of mental health problems is affected by exposure to risk factors and the availability of protective resources (IOM, 1994). In the person–environment transactional model, dynamic person–environment processes are seen as affecting problems and competence, which then influence the social environment and competence and problems (Sameroff, 2000). The program was designed to reduce interparental conflict, one of the most harmful risk factors in divorced families, and to augment the empirically supported protective factors of mother–child relationship quality, contact with fathers, and effective discipline. From the perspective of developmental cascade models, the program’s effects on these risk and protective factors in childhood were expected to lead to positive changes across domains of functioning (Masten et al., 2005; Rutter & Sroufe, 2000; Sameroff, 2000).

This project examined the long-term effects of the New Beginnings Program by testing its effects on competence in emerging adulthood. We expected that program-induced changes in parenting and behavior problems in childhood would have cascading effects on competencies and behavior problems in adolescence, which in turn would have cascading effects on competence in adulthood. This hypothesis is derived from two interconnected models, the organizational theory of development and the person–environment transactional model. The organizational theory posits that qualitative reorganizations among and within domains of functioning occur throughout development and that competence at one period of development influences competence at the next period (Cicchetti & Schneider-Rosen, 1986). Similarly, in the person–environment transactional model, individual as well as environmental processes are seen as affecting both problems and competence, which then influence the social environment as well as competence and problems within and across development periods (Sameroff, 2000). In both frameworks, developmental cascades, or the interactions and transactions that occur within and across developing domains of functioning, play a central role in explaining change and continuity in development.

The current research builds on prior work examining the long-term direct and cascade effects of the New Beginnings Program on problem outcomes. Wolchik, Tein, Sandler, and Kim (2016) found that program-induced improvements in academic competence and adaptive coping in adolescence cascaded to fewer internalizing problems, externalizing problems, and binge drinking in emerging adulthood. The current study extends this work by testing whether the New Beginnings Program had positive direct effects on competence in emerging adulthood and whether the program’s effects in childhood influenced outcomes in adolescence, which then led to increased competence in emerging adulthood. Based on a developmental cascade model, intervention-induced improvements in parenting were expected to lead to fewer internalizing problems and externalizing problems in childhood, which were expected to lead to improvements in mental health problems, substance use, peer competence, grades, and adaptive coping in adolescence. These improvements were then expected to lead to increases in work competence, academic competence, peer competence, and romantic competence in emerging adulthood. Given that sex and baseline risk moderated other program effects at the 15-year follow-up (Christopher et al., 2017; Wolchik et al., 2013, 2019), their moderating effects were tested.

Method

Participants

The participants were 240 adult offspring and their mothers who had enrolled in a randomized trial of the intervention for divorced families (Wolchik et al., 2000) in late childhood/early adolescence. Court records of divorce decrees that had been granted in the last two years in a southwestern metropolitan county were the primary recruitment method, but 20% were recruited through the media or word of mouth. The eligibility criteria were as follows: the mother had a child between 9 and 12 years old who lived with her at least 50% of the time; the mother had not remarried, did not have a live-in partner, and did not plan to remarry during the program; and neither the mother nor child was in treatment for psychological problems (see Wolchik et al., 2000 for more information about eligibility and recruitment). Because of ethical considerations, families were excluded and referred to treatment if the child endorsed suicidal ideation or had severe internalizing or externalizing problems at the pretest. In families with multiple children in the age range, one was randomly selected to be interviewed. Eligibility was assessed in a phone call and reassessed during the pretest interview.

Of the 622 eligible families, 240 (39% of those eligible) completed an orientation session in which they were randomly assigned to (a) the mother-only program (MP, n = 81 families), (b) the mother-plus-child program (MPCP; separate, concurrent groups for mothers and children, n = 83 families), or (c) the literature control condition (LC, n = 76 families). Preliminary analyses comparing the MPCP and MP on all of the competence outcomes in emerging adulthood indicated that the two intervention conditions did not significantly differ on these variables. Given the lack of differences between the MP and MPCP programs on the competence outcomes and other outcome and mediator variables in our previous studies at posttest, 6-month, 6-year, and 15-year follow-ups (Wolchik et al., 2000, 2002, 2013), these conditions were combined and labeled as the New Beginnings condition.

Comparison of acceptors and refusers (i.e., completed the pretest but withdrew from the experimental trial of the program) showed that mothers who accepted the intervention had significantly higher incomes and education and fewer children than those who declined the intervention (Wolchik et al., 2000). The three experimental conditions did not differ significantly on child mental health problems nor demographics at pretest.

At pretest, 49% of the offspring were girls, and the average age was 10.4 years (SD = 1.1). The mothers’ mean age was 37.3 years (SD = 4.8); 98% had at least a high school education. The break-down for the mothers’ ethnicity was 88% non-Hispanic White, 8% Hispanic, 2% Black, 1% Asian or Pacific Islander, and 1% other. The mothers had been separated and divorced an average of 2.2 years (SD = 1.4) and 1.0 year (SD = 0.5), respectively.

At the 6-year and 15-year follow-ups, the offspring’s average age was 16.9 (SD = 1.1, range = 15–19) and 25.6 (SD = 1.2, range = 24–28), respectively. At both follow-ups, 50% of the offspring who were interviewed were female; ethnicity was 89% non-Hispanic White, 7% Hispanic, 2% African American, and 2% other. At the 15-year follow-up, educational attainment was less than high school (3%), high school (20%), some college (45%), college graduate (29%), and postgraduate (3%). The median income was $30,000, and 23% were married, 1% divorced, 1% separated, 28% living with a partner, and 46% were not previously married, currently married, or living with a partner.

Sample size and power

A sample size of 240 was selected so that small-to-medium effects, the magnitude of the effects that were found in the pilot study of the MP (Wolchik et al., 1993), could be detected with power ≥ .80.

Intervention Conditions

Description of conditions

The parent program consisted of 11 highly structured group sessions (1.75 hours) and two individual (1 hour) sessions that taught skills to improve mother–child relationship quality, increase effective discipline, decrease barriers to father–child contact, and reduce children’s exposure to interparental conflict. The sessions included didactic presentations, modeling of the skills by leaders and videotaped actors, role plays of the skills, and review of the program skills that were practiced between sessions.

The 11-session child program was intended to increase effective coping strategies, enhance mother–child relationship quality, and reduce negative thoughts about divorce stressors. The sessions included didactic presentations, videotapes, leader modeling, role plays, and games. The children were expected to practice the program skills between sessions. For details about the programs see Wolchik et al. (2000).

Each group was led by two master’s-level clinicians (13 leaders for the mother groups; 9 for the child groups). Eight to 10 mothers or children were in each group. The leaders used highly detailed session manuals to deliver the groups. Extensive training (30 hr prior to the start of the program and 1.5 hr per week during delivery) and weekly supervision (1.5 hr per week) were provided by doctoral-level clinicians. Prior to the delivery of each session, the leaders were required to score 90% on a quiz about the content of the session. The average scores were 97% (SD = 3%) and 98% (SD = 1%) for the leaders in the mother and child groups, respectively.

Mothers and children in the LC each received three books on children’s adjustment to divorce, which were mailed at 1-month intervals. The mothers and children reported reading about half of the books.

Leader completion of program segments

Using the detailed session outlines, each mother session was divided into 7–11 segments and each child session was divided into 7–10 segments. Using videotapes of the sessions, independent coders rated the degree to which each segment was completed (1 = not at all completed; 3 = completed). Interrater reliability, assessed for a randomly selected 20% of the sessions, averaged 98%. The mean degree of segment completion was 2.86 (SD = 0.39) and 3.00 (SD = 0.02) for the mother and child sessions, respectively.

Mother compliance with program

The mothers attended an average of 77% (M = 10.02; SD = 3.56) of the 13 sessions (11 group; 2 individual), and the children attended an average of 78% (M = 8.55; SD = -2.97) of 11 group sessions. When attendance at the make-up sessions was included, the mothers and children attended an average of 83% (M = 10.76; SD = 3.62) and 85% (M = 9.30; SD = 3.00) of the sessions, respectively.

The mothers completed weekly homework diaries reporting on the skills that they practiced. Two coders evaluated the diaries for appropriate completion of each assigned activity. One coder rated all of the diaries, and the other independently rated a randomly selected subset (20%). Interrater agreement averaged 98%. The proportion of assigned activities that was appropriately completed was .54 (SD = .15) and .55 (SD = .15) for the mother and mother-plus-child conditions, respectively.

Procedure

The families participated in six assessments: pretest (T1); posttest (T2); and 3-month (T3), 6-month (T4), 6-year (T5), and 15-year follow-ups (T6). Family-level participation was 98% at T2, T3, and T4; 91% at T5; and 90% at T6. Different trained staff conducted separate interviews with parents and youths/emerging adults. After confidentiality was explained, the children signed assent forms and the parents and offspring over 18 signed consent forms. The families received $45 compensation at T1, T2, T3, and T4, and the parents and youths each received $100 at T5. At T6, the emerging adults received $225 and the parents received $50. The university’s Institutional Review Board approved the study procedures.

Measures

The measures are described in terms of the developmental period in which they were administered (e.g., T1–T4 for childhood, T5 for adolescence, and T6 for emerging adulthood). Measures with a timeframe referred to the last month, with exceptions noted. We report the reliability coefficients of the measures for the assessment points that were included in the models.

Childhood

Demographics

At the pretest, the mothers completed questions about demographic variables including their children’s and their own age, ethnicity, income, and length of divorce and marriage.

Positive parenting

Positive parenting was a composite of mother and child reports of mother–child relationship quality and discipline at T1 and T2. The discipline and relationship quality composites were strongly related (r = .52 at T1; r = .51 at T2).

Mother–child relationship quality.

The mothers and children completed 10 items each from the acceptance and rejection subscales of the Child Report of Parental Behavior Inventory (CRPBI; Schaefer, 1965). Cronbach alphas (α) for the acceptance and rejection subscales at T1 and T2, respectively, were .78 and .81 for the mother reports and .84 and .89 for the child reports. Adequate reliability and validity have been demonstrated for child and parent reports of these scales (e.g., Schaefer, 1965; Wolchik, Wilcox, Tein, & Sandler, 2000). The mothers and children also completed the 10-item open family communication subscale of the Parent–Adolescent Communication Scale (Barnes & Olson, 1982). Parent–Adolescent Communication Scale scores have been linked to adolescents’ psychological adjustment (Bhushan & Shirali, 1992). Cronbach alphas were .72 and .75 for mothers at T1 and T2, respectively, and .82 and .87 for children at T1 and T2, respectively. The mothers completed a seven-item adaptation of the Family Routines Inventory (Jensen, Boyce, & Hartnett, 1983) that assessed mother–child dyadic interactions. Cronbach alphas were .67 and .63 for the mothers at T1 and T2, respectively. Previous research showed adequate reliability and validity of this measure (Cohen, Taborga, Dawson & Wolchik, 2000). Consistent with previous studies on the New Beginnings Program, reports on these four scales were standardized and averaged to create a multimeasure, multireporter composite. The weighted alphas (Lord & Novick, 1968) across the variables were .88 and .90 at T1 and T2, respectively. Using confirmatory factor analyses, Zhou, Sandler, Millsap, Wolchik, and Dawson-McClure (2008) showed the constructs of mother–child relationship quality and effective discipline (described in the next section) fit the T1 and T2 data adequately.

Effective discipline.

Mothers and children completed the eightitem inconsistent discipline subscale of CRPBI (Schaefer, 1965). Both mothers’ and children’s reports of consistency of discipline have been shown to negatively relate to children’s adjustment problems (e.g., Wolchik, Wilcox, Tein & Sandler, 2000). Cronbach alphas were .81 and .80 for mother report at T1 and T2, respectively, and .72 and .73 for child report at T1 and T2, respectively. The mothers completed 14 items on the appropriate/inappropriate discipline subscale (T1 α = 0.70, T2 α = 0.71) and 11 items on the follow-through subscale (T1 α = 0.80, T2 α = 0.76) of the Oregon Discipline Scale (Oregon Social Learning Center, 1991). This measure has adequate reliability and validity. These four scales were standardized and averaged to create a composite. The weighted Cronbach alphas were .84 and .89 at T1 and T2, respectively.

Internalizing and externalizing problems

The mothers completed the 31-item internalizing and 33-item externalizing subscales of the Child Behavior Checklist (Achenbach, 1991a; Achenbach & Edelbrock, 1983). Adequate reliability and validity have been reported (Achenbach, 1991b). At T1 α =.88, at T3 α = .86, and at T4 α = .85 for internalizing problems, Cronbach alphas were .87 at T1, .87 at T3, and.87 at T4 for externalizing problems.

Child report of depression during the previous two weeks was measured with the 27-item Child Depression Inventory (CDI; Kovacs, 1981). The CDI has been shown to have high internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and validity (Saylor, Finch, Spirito, & Bennett, 1984). In this study, Cronbach alphas were .76 at T1, .78 at T3, and .80 at T4. Youth report of anxiety was assessed with the 28-item Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale (RCMAS; Reynolds & Richard, 1978). Convergent and discriminant validity are adequate (Reynolds & Paget, 1981). At T1, T3, and T4, Cronbach alphas were .88, .91, and .91. For child report of internalizing problems, a composite of the CDI and RCMAS was formed as the mean of the standardized scores (r = .58–.67 of the two measures across assessments). For externalizing problems, 30 items from the aggression and delinquency subscales of the Youth Self Report (YSR; Achenbach, 1991b) were used, and at T1 α = .87, at T3 α = .86, and at T4 α = .88. The reliability and validity of these subscales are adequate (Achenbach, 1991b).

Given the 3-month interval, scores for T3 and T4 were averaged (i.e., short-term follow-up). Composite scores of internalizing problems and externalizing problems were constructed by averaging the standardized scores of the mother and child reports.

Adolescence

Symptoms of externalizing and internalizing disorders

Parents and adolescents reported on symptoms of externalizing disorders and internalizing disorders over the past year on the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (Shaffer, Fisher, Lucas, Dulcan, & Schwab-Stone, 2000). Scores were computed separately for internalizing disorders (i.e., agoraphobia, generalized anxiety disorder, obsessive–compulsive disorder, panic disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, social phobia, specific phobia, eating disorders, and major depression) and externalizing disorders (i.e., conduct disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder) using symptom scores endorsed by either the parent or adolescent. The DIS has been validated against the WHO Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry (Wing et al., 1990).

Substance use

Frequency of marijuana use and alcohol use within the past year (7-point scale, 1 = 0 occasions to 7 = 40 or more occasions) was assessed by using the Monitoring the Future Scale (Johnston, Bachman, & O’Malley, 1993). This scale has adequate validity (Johnston et al., 1993). The mean of the frequencies of marijuana and alcohol use was used.

Peer competence

Peer competence was assessed by using adolescent’s report of the six-item peer competence subscale of the Coatsworth Competence Scale (CCS; Coatsworth & Sandler, 1993). This scale has been shown to have adequate psychometric properties (Spaccarelli, Coatsworth, & Bowden, 1995). Cronbach alpha at T5 was .76.

Adaptive coping

Adolescents completed the 24-item active coping dimension of the Children’s Coping Strategies Checklist–Revised (Ayers, Sandler, West, & Roosa, 1996) and the seven-item Coping Efficacy Scale (Sandler, Tein, Mehta, Wolchik, & Ayers, 2000). Active coping reflected positive strategies for dealing with problems (e.g., behavioral actions to fix the problem or cognitive strategies to reduce the threat of the stressor). Coping efficacy assessed satisfaction with handling past problems and anticipated effectiveness in handling future problems. Both active coping and coping efficacy have been shown to relate to internalizing and externalizing problems (Sandler et al., 2000). For active coping and coping efficacy, Cronbach alphas were .88 and .71, respectively, for T1, and .92 and .82, respectively, at T5. The correlation between active coping and coping efficacy was .53 at T1 and .55 at T5. The two measures were standardized and averaged.

Academic performance

Cumulative high school grade point average (GPA) was obtained with questionnaires that were mailed to school principals that requested the unweighted (based on a 4.0 scale) cumulative GPA. Data were collected for all of the participants, regardless of current school enrollment.

Emerging adulthood

Competence

Competence was defined in terms of effective performance in age-salient developmental tasks (Masten et al., 1995). Academic competence was assessed as highest year of education completed. Peer social competence, romantic competence, and work competence were assessed by using a paper-pencil version of the Status Questionnaire (Roisman, Masten, Coatsworth, & Tellegen, 2004). After achieving reliability (agreement within one rating scale point for 80% or more of the ratings), coders who were trained by one of the developers of the Status Questionnaire reviewed the responses on the questionnaire and made global ratings of peer, romantic, and work competence. The intraclass coefficients ranged from .70 to .90, with a mean of .83. The work competence score was based on an assessment of holding a job successfully and doing well in work. The peer competence score was based on the degree of involvement in friendships and presence of a close friendship. The romantic competence score was based on involvement in and quality of a romantic relationship. The construct validity of these aspects of competence has been established (Masten et al., 1995).

Baseline covariates and risk

For the postintervention variables, we used the baseline measure of the same measure if administered or a similar measure as a covariate (e.g., T1 peer competence for T5 peer, work, and romantic competence; T1 internalizing problems for T5 internalizing symptoms). We also included baseline internalizing problems and self-esteem as covariates given that they significantly predicted attrition at the 15-year follow-up (Wolchik et al., 2013).

Previous studies have shown that the program had stronger effects for youths who had higher risk at baseline (Christopher et al., 2017; Wolchik et al., 2007), and risk has been found to predict child mental health problems at the 6-year follow-up in the control group of this trial (Dawson-McClure, Sandler, Wolchik & Millsap, 2004). Therefore, risk was included as a covariate and we examined whether risk moderated the effects of the program. As in the study by Dawson-McClure et al. (2004), risk was a composite score (i.e., the equally weighted sum of the standardized scores) of the following variables: (a) mother and child reports of child externalizing problems at baseline (the 33-item externalizing subscale of the CBCL for the mother report and 30 items from the aggression and delinquency subscales of the YSR for the child report) and (b) environmental stressors (i.e., the composite of interparental conflict, negative life events that occurred to the child, and per capita annual income).

Statistical Analysis

We first conducted correlational and descriptive statistics. Attrition analyses conducted by Wolchik et al. (2013) showed that the rates of attrition did not differ significantly across the intervention and LC and there were no significant main effects for attrition or Group × Attrition interaction effects on the demographic and baseline variables except that baseline internalizing problems and self-esteem significantly predicted attrition at the 15-year follow-up. Participants in the 15-year follow-up had significantly more internalizing problems, −0.06 vs. −0.30, t = −2.05, p = .03, and lower self-esteem, 20.45 vs. 21.53; t = 2.33, p = .03, at baseline than those who did not participate. As noted above, we included baseline internalizing problems and self-esteem as covariates.

Separate multiple regression analyses were conducted to examine program effects on the competence measures. The models also included an Intervention × Baseline risk interaction. To reduce the number of parameter estimates and make the figures visually less complicated, we present the cascade mediation models separately for each competence outcome. However, we also ran analyses with all of the competence outcomes in one model for comparison purposes. The results for the path coefficients from the predictors and mediators to the outcomes were consistent between the model that included all of the competence outcomes in one model (results not shown) and those that included only one outcome at a time. All of the differences of the corresponding regression coefficients were less than (unstandardized) b = .02.

The cascade mediation models shown in Figures 1–3—intervention condition → posttest (T2) → short-term follow-up (3-month follow-up + 6-month follow-up; T3 + T4) → 6-year follow-up (T5) → 15-year follow-up (T6)—were tested by using structural equation modeling (i.e., path modeling with observed variables) that was completed by using Mplus 8 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2017). The full information maximum likelihood method was applied to handle missing data. The skewness and kurtosis of the variables in the models were all within the acceptable range (skewness cutoff ≤ 2 and kurtosis cutoff ≤ 7; West, Finch, & Curren, 1995), so we used the maximum likelihood method for parameter estimation.

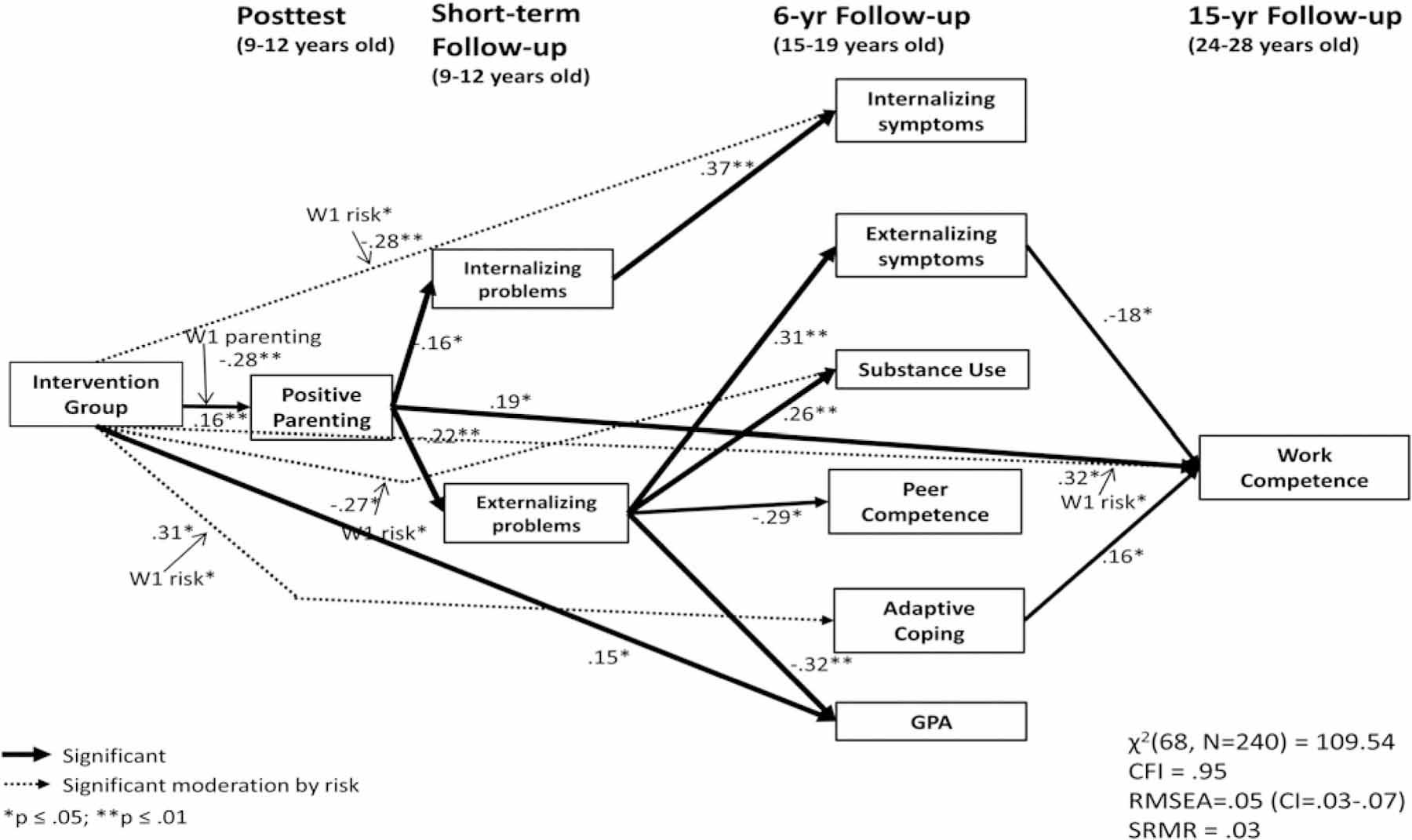

Figure 1.

Cascade effects of adolescent mental health problems, substance use, and competence on work competence in emerging adulthood.

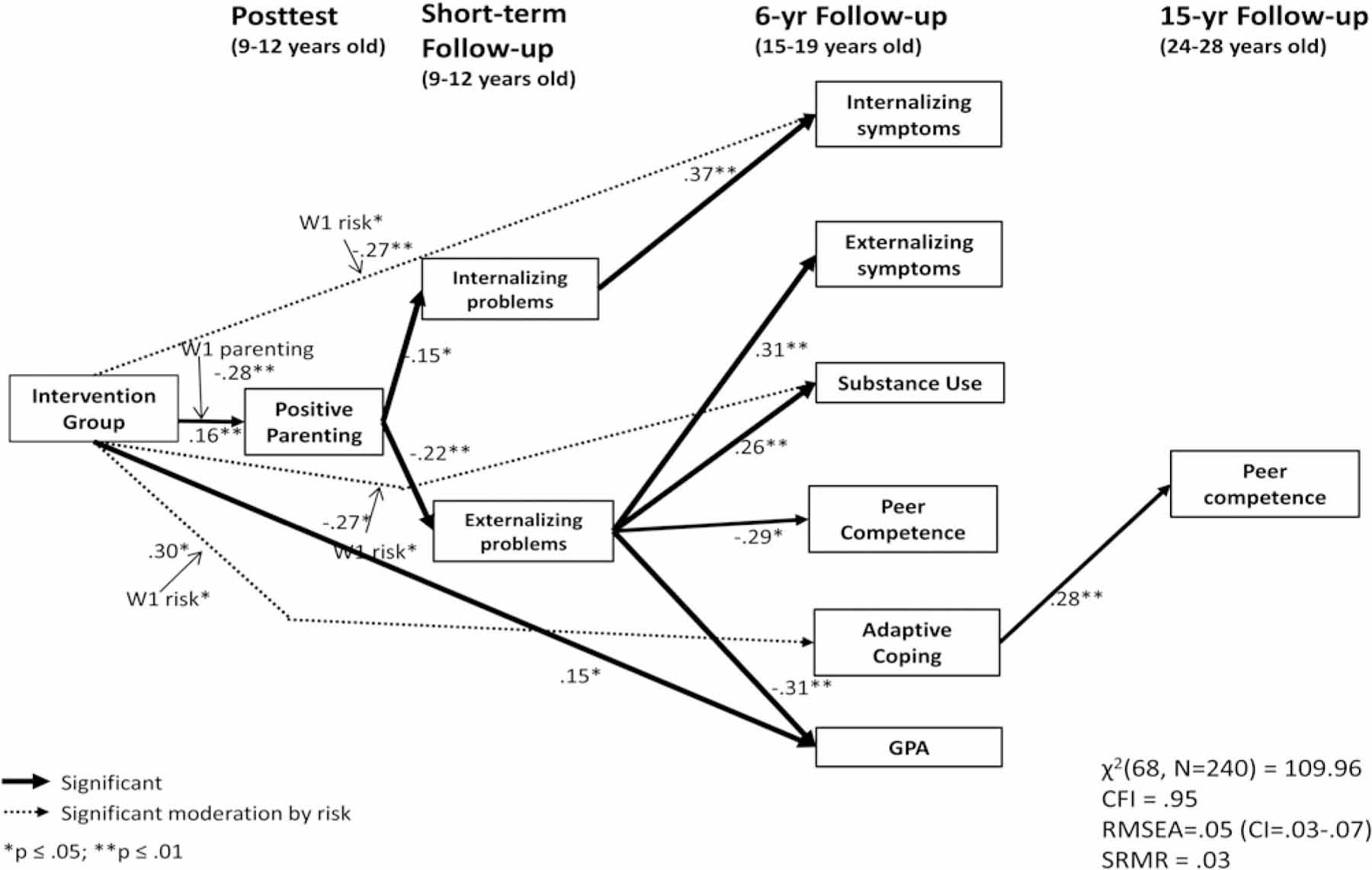

Figure 3.

Cascade effects of adolescent mental health problems, substance use, and competence on peer competence in emerging adulthood.

For each postintervention childhood, adolescence, and emerging adulthood mediator and outcome measure, we also included direct paths from T1 covariates, the intervention condition (to test direct intervention effects), baseline risk, and the Intervention Condition × Risk interaction (to examine possible moderated intervention effects by risk). If an interaction was not significant, we deleted it and reran the model. We also added the baseline positive Parenting × Intervention interaction in predicting posttest positive parenting given that Wolchik et al. (2000) showed that the program effect on parenting was stronger for families with lower baseline parenting scores. To make Figures 1–3 visually less complicated, we omitted the paths from the baseline covariates to the mediators and outcomes and the correlations among the study variables that were measured at the same time. Supplemental Tables 1–4 present the path coefficients from the baseline covariates to the mediators and from the mediators in the earlier assessments to the later assessments as well as the correlations among the contemporaneous variables.

We examined the potential mediation effects by using the bias-corrected bootstrapping method (Mackinnon et al., 2002), a method that has been shown to have good statistical power and excellent control of Type I error rates. If zero were not included in the 90% or 95% confidence interval (CI), it was assumed that the mediated effect was statistically significant.

We conducted multigroup structural equation modeling to test for sex differences by examining which regression parameters were significantly different between males and females.

Results

Correlations

Tables 1, 2, and 3 present the correlations among the baseline measures, among the postintervention measures, and between the baseline and postintervention measures. Means, standard deviations, and skewness and kurtosis indices of these variables are also included. The correlations between the competence outcome variables ranged from .12 to .27.

Table 1.

Correlations of the baseline measures

| Intervention | Positive parenting | Baseline risk | Internalizing problems | Self-esteem | Peer competence | Academic competence | Active coping | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | 1 | |||||||

| Positive parenting | −.073 | 1 | ||||||

| Baseline risk | .103 | −.453** | 1 | |||||

| Internalizing problems | .065 | −.440** | .582** | 1 | ||||

| Self-esteem | −.038 | .284** | −.192** | −.344** | 1 | |||

| Peer competence | −.070 | .177** | −.300** | −.445** | .450** | 1 | ||

| Academic competence | −.063 | .272** | −.374** | −.282** | .349** | .441** | 1 | |

| Active coping | .015 | .187** | −.142* | −.214** | .270** | .192** | .197** | 1 |

| Mean | .683 | 0 | 0 | 0 | −.056 | −.001 | −.001 | .001 |

| Standard deviation | .216 | .346 | .996 | .996 | .238 | .994 | .998 | .762 |

| Skewness | −.788 | −.529 | .437 | .696 | .038 | −1.364 | −.673 | .042 |

| Kurtosis | −1.379 | −.124 | .027 | .142 | −1.364 | 2.578 | .061 | −.007 |

Note:

p ≤ .01.

p ≤ .05.

Table 2.

Correlations of the postintervention measures

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. T2 Positive parenting | 1 | ||||||||||||

| 2. T3/T4 Short-term internalizing problems | −.413** | 1 | |||||||||||

| 3. T3/T4 Externalizing problems | −.448** | .603** | 1 | ||||||||||

| 4. T5 Internalizing symptoms | −.229** | .465** | .348** | 1 | |||||||||

| 5. T5 Externalizing symptoms | −.261** | .326** | .458** | .512** | 1 | ||||||||

| 6. T5 Substance use | −.118 | .231** | .301** | .308** | .427** | 1 | |||||||

| 7. T5 Peer competence | .030 | −.243** | −.309** | −.273** | −.334** | −.154* | 1 | ||||||

| 8. T5 Adaptive coping | .126 | −.197** | −.175* | −.248** | −.301** | −.182** | .373** | 1 | |||||

| 9. T5 GPA | .292** | −.194** | −.385** | −.244** | −.418** | −.278** | .217** | .217** | 1 | ||||

| 10. T6 Work competence | .223** | −.214** | −.218** | −.186* | −.274** | −.123 | .009 | .228** | .211** | 1 | |||

| 11. T6 Peer social competence | .138 | −.041 | −.045 | −.015 | −.120 | .051 | .115 | .308** | .172* | .174* | 1 | ||

| 12. T6 Romantic relationship competence | .076 | .021 | −.130 | .018 | −.114 | −.029 | .121 | .179* | .144 | .091 | .202** | 1 | |

| 13. T6 Academic competence | .183* | −.163* | −.308** | −.197** | −.251** | −.058 | .041 | .109 | .481** | .222** | .273** | .123 | 1 |

Note:

p ≤ .01.

p ≤ .05.

Table 3.

Correlation between baseline measures and postintervention measures

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | .084 | −.016 | −.007 | −.005 | .027 | −.044 | −.086 | −.035 | .122 | .098 | .079 | −.109 | .044 |

| Positive parenting | .688** | −.368** | −.393** | −.217** | −.295** | −.148* | .093 | .146* | .251** | .155* | .188* | .069 | .135 |

| Baseline risk | −.428** | .502** | .613** | .317** | .419** | .175* | −.221** | −.232** | −.320** | −.162* | −.185* | −.105 | −.359** |

| Internalizing problems | −.392** | .655** | .413** | .431** | .314** | .168* | −.222** | −.226** | −.113 | −.055 | −.064 | .007 | −.028 |

| Self-esteem | .351** | −.293** | −.217** | −.055 | −.041 | −.084 | .134 | .117 | .043 | −.041 | .022 | .029 | −.099 |

| Peer competence | .179** | −.354** | −.252** | −.189** | −.146* | .115 | .337** | .131 | .044 | −.083 | .085 | .069 | −.070 |

| Academic competence | .306** | −.250** | −.287** | −.149* | −.157* | −.105 | .146* | .104 | .238** | −.020 | .074 | .121 | .183* |

| Active coping | .156* | −.076 | .002 | −.125 | −.106 | −.211** | .145* | .205** | .010 | .045 | .078 | .154* | −.112 |

| Mean | .301 | −.615 | −.373 | 1.036 | 3.773 | 2.514 | −0.371 | .644 | 2.849 | 4.814 | 3.693 | 3.905 | 5.959 |

| Standard deviation | .316 | .348 | .444 | .590 | 5.927 | 2.810 | 1.440 | .954 | .456 | 1.843 | .629 | .835 | 3.710 |

| Skewness | −.463 | 1.148 | .117 | 1.144 | 1.041 | 1.140 | −0.886 | .086 | −.510 | −.753 | −.416 | −.538 | −.387 |

| Kurtosis | −.387 | 1.622 | −.788 | 1.747 | 1.135 | .347 | .477 | −.742 | −.060 | .478 | −.190 | −.768 | −1.009 |

Note: 1. T2 Positive parenting; 2. T3/T4 Internalizing problems; 3. T3/T4 Externalizing problems; 4. T5 Internalizing symptoms; 5. T5 Externalizing symptoms; 6. T5 Substance use; 7. T5 Peer competence; 8. T5 Positive coping; 9. T5 GPA; 10. T6 Work competence; 11. T6 Peer social competence; 12. T6 Romantic relationship competence; 13. T6 Academic competence.

p ≤ .01.

p ≤ .05.

Direct Effects on Competence

Multiple regression analyses showed that the effect of the intervention condition (intervention vs. LC) on work competence, unstandardized b = .43, SE = .22, z = 1.95, p = .052, was marginally significant and the interaction of Intervention × Baseline Risk on work competence, b = .59, SE = .28, z = 2.06, p = .04, was significant. On average, the participants in the intervention condition had higher work competence, MLC = 4.47, MI = 4.90; Cohen d = .27, than did those in the LC condition. The difference on work competence was greater for those who had higher levels of baseline risk (e.g., at one standard deviation above the mean of baseline risk, b = 1.02, SE = .41, z = 2.48, p = .01, d = .35. The direct effects of the intervention and the Intervention × Baseline Risk interaction on academic competence, peer competence, and romantic competence were not significant.

Cascade Effects

Childhood to adolescence

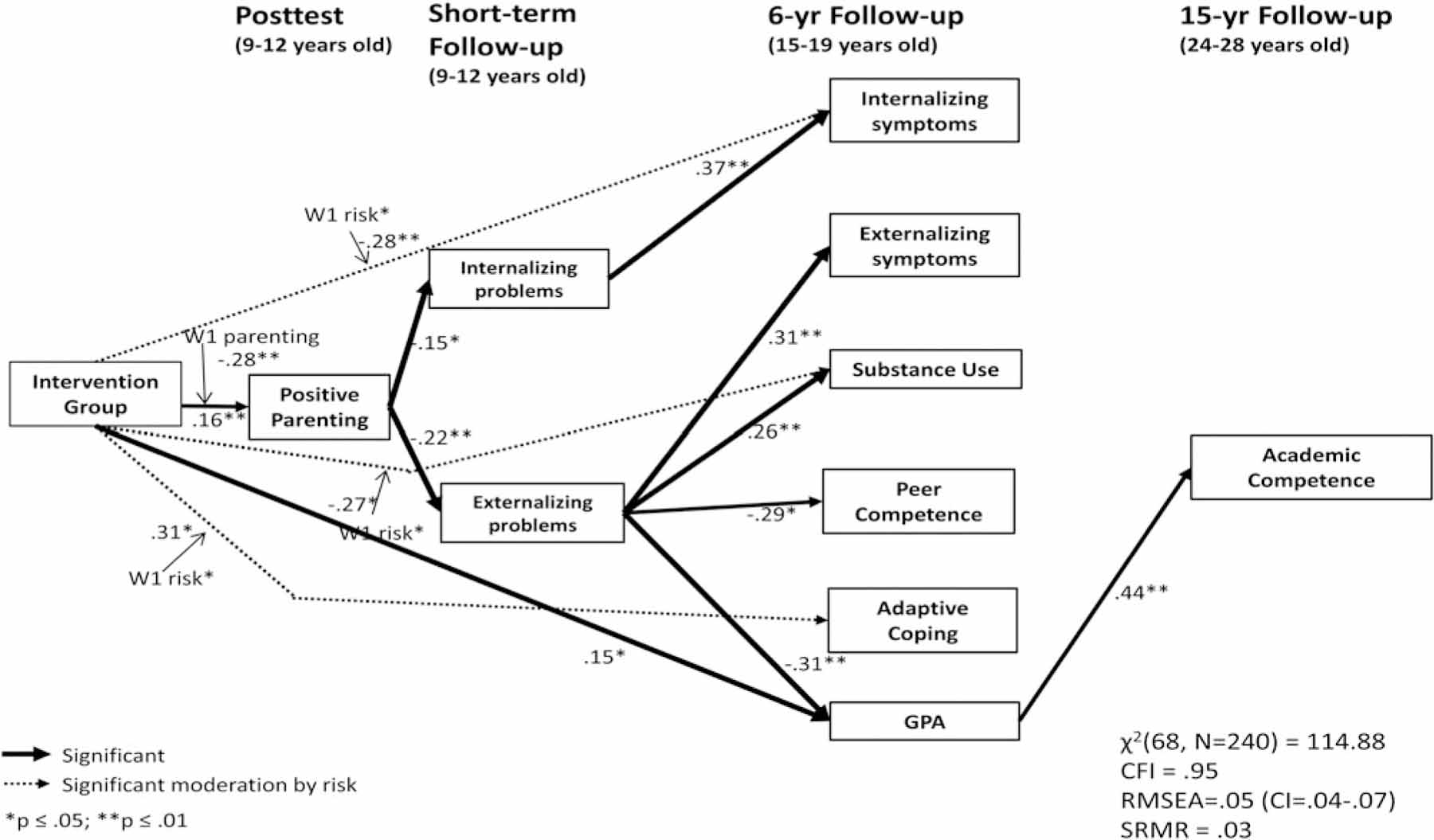

Figures 1–3 show the cascade models for (a) work competence, (b) academic competence, and c) peer competence. The figures include the model fit indices and standardized regression coefficients for the paths that were significant, excluding the significant paths from the covariates to the mediators and outcomes.

All three models fit the data adequately (comparative fit index ≥ .94, root mean square error of approximation ≤ .06; standardized root mean square residual ≤ .04; See Hu & Bentler, 1999). The mediation pathways from intervention condition to adolescence (6-year follow-up) were mostly consistent across outcomes, but the parameter estimates varied slightly across models due to the use of the maximum likelihood method with models that had different dependent variables.

As expected, the cascading mediation effects of the intervention to parenting and internalizing and externalizing problems in childhood and to mental health problems, substance use, and competence in adolescence were largely consistent with the findings that were presented in Wolchik et al. (2016). Specifically, the intervention increased positive parenting at posttest and this effect was stronger for families with lower positive parenting scores at baseline. Posttest positive parenting was related to fewer internalizing and externalizing problems at the short-term follow-up (3-month and 6-month follow-ups). Internalizing problems in childhood were related to higher internalizing symptoms in adolescence. Externalizing problems in childhood were related to higher externalizing symptoms and substance use in adolescence as well as lower peer competence and GPA. In addition, the intervention had a direct positive effect on adolescent GPA. Baseline risk moderated the intervention effects on internalizing symptoms, substance use, and adaptive coping in adolescence such that the intervention was related to lower internalizing symptoms, lower substance use, and higher adaptive coping for those with higher baseline risk. Further, multigroup comparisons of the models across sex revealed that externalizing problems in childhood were positively related to internalizing symptoms in adolescence for females, standardized β = .33; unstandardized b = .43, SE = .12, z = 3.69, p ≤ .001, but not for males, β = .08; b = .09, SE = .15, z = .59, p = .56.

Adolescence to emerging adulthood

As shown in Figure 1, higher externalizing symptoms in adolescence were associated with lower work competence in emerging adulthood, β = −.18; b = −.10, SE = .05, z = −1.98, p = .048, and higher levels of adaptive coping were associated with higher work competence, standardized β = .16; b = .22, SE = .10, z = 2.23, p = .03. In addition to these paths, the intervention-induced improvements in positive parenting in childhood were positively related to work competence in emerging adulthood, β = .19; b = .46, SE = .19, z = 2.39, p = .02. After controlling for all of the intermediate variables in childhood and adolescence, the direct effect from the intervention on work competence was still significantly moderated by baseline risk, β = .32; b = .51, SE = .26, z = 1.98, p = .048, such that the intervention was related to higher work competence for youths with higher levels of baseline risk (e.g., at one standard deviation above the mean of baseline risk, β = .28; b = .84, SE = .39, z = 2.15, p = .03). Testing the mediation effects with the bias-corrected bootstrapping method showed that the mediation pathway of the intervention to positive parenting at posttest to externalizing problems in childhood to externalizing symptoms in adolescence to work competence was significant, mediation effect = .006, 95% CI [.001, .021]. In addition, the mediation pathway of the intervention to adaptive coping in adolescence to work competence was significant within a 90% confidence interval, mediation effect = .075, 90% CI [002, .228], for youths who had higher levels of baseline risk.

As shown in Figure 2, GPA in adolescence was positively related to academic competence in emerging adulthood, β = .44; b = 1.23, SE = .21, z = 5.90, p ≤ .001. The mediation pathway of the intervention to posttest positive parenting to externalizing problems in childhood to GPA in adolescence to academic competence was significant, mediation effect = .020, 95% CI [.005, .055].

Figure 2.

Cascade effects of adolescent mental health problems, substance use, and competence on academic competence in emerging adulthood.

As is shown in Figure 3, adaptive coping in adolescence was positively related to peer competence in emerging adulthood, β = .28; unstandardized b = .23, SE = .06, z = 3.63, p ≤ .001. Further, the mediation pathway of the intervention to adaptive coping in adolescence to peer competence was significant within a 90% confidence interval, mediation effect = .077, 90% CI [.007, .199], for youths with higher levels of baseline risk.

None of the paths from the variables in adolescence to romantic competence was significant. Analyses of sex differences showed that there were no significant differences in any of the paths from adolescent outcomes to the competence outcomes in emerging adulthood for any of the competence outcomes.

Discussion

This was the first study to test the effects of a relatively brief parenting-focused prevention program that was delivered during childhood on competence in emerging adulthood. Using a cascading effects model, the analyses examined competence in four salient developmental task domains of emerging adulthood: academic competence, work competence, romantic competence, and peer competence. The cascading effects tests were housed within a larger model in which positive cascade effects of the program occurred on mental health problems in childhood, which led to lower levels of mental health and other behavior problems as well as higher levels of competence in adolescence. Both direct and cascading significant effects of the program were found. For work competence, there was a significant direct effect of the intervention on work competence, which was stronger for those who entered the program at higher risk. Consistent with the organizational theory of development and person–environment transactional model, cross- and within-domain cascading effects were found. Cross-domain effects of externalizing problems and adaptive coping in adolescence were found for work competence. Also, adaptive coping in adolescence was related to peer competence. There was continuity in academic competence from adolescence to emerging adulthood, indicating that the earlier occurring cascade effects from parenting to externalizing problems to academic competence were sustained into adulthood. Because the analyses controlled for the longitudinal stability of functioning in these domains and for the within-assessment-period covariance among functioning in the domains that were assessed in adolescence, they provided conservative tests of these effects. Mediational analyses indicated that the intervention’s effects on outcomes in emerging adulthood were partially accounted for by program-induced improvements that occurred in positive parenting in childhood, which led to improvements in externalizing problems, academic performance, and adaptive coping in adolescence. Below, we discuss the contributions of the study, how its findings relate to other work in the field, its limitations, and directions for future work.

Direct and Cascading Effects of the Intervention on Competence in Emerging Adulthood

Work competence

The domain of work is considered to be a developing area of competence in emerging adulthood (Masten, Desjardins, McCormick, Kuo, & Long, 2010; McCormick, Kuo, & Masten, 2010; Roismann et al., 2004). The program effects on work competence have important implications given the well-documented relation between success in the workplace and a wide array of outcomes in emerging adulthood and later developmental stages including occupational, financial, mental health outcomes as well as life satisfaction (Erdogan, Bauer, Truxillo, & Mansfield, 2012; Masten, Burt, & Coatsworth, 2006; Masten et al., 2010; Sampson & Laub, 1990; Scollon & Diener, 2006; Upadyaya & Salmela-Aro, 2017). The intervention increased work competence in emerging adulthood for those with high risk at program entry. Although the effect size (d = .35) was small to medium, the potential contribution to improved public health could be sizeable if this intervention were widely disseminated. Previous analyses of the short-term and long-term effects of the intervention have found Baseline Risk × Intervention interaction effects on other outcomes (Christopher et al., 2017; Wolchik et al., 2007). Similar interactive effects have been found for behavior problem outcomes in studies of other parenting-focused prevention programs (e.g., for a review see Sandler, Ingram, Wolchik, Tein & Winslow, 2015). Moreover, this result is congruent with findings from numerous passive studies implicating better parenting and family functioning as protective influences on the development of competence in at-risk children (Masten & Palmer, 2019).

In addition to this interactive effect, externalizing problems in adolescence were negatively associated with lower work competence. This finding is consistent with those of passive longitudinal studies (Capaldi & Stoolmiller, 1999; Masten et al., 2010; Moffitt et al., 2001). Externalizing problems in adolescence may reduce environmental and interpersonal opportunities that promote competence in the work setting in emerging adulthood. Alternatively, it is possible that problems that are associated with externalizing problems, such as substance use or unreliability, may lead to later employment problems or that the continuity of externalizing problems may create interpersonal or behavior problems in the work setting that mitigate work competence in emerging adulthood. Adaptive coping in adolescence was significantly positively related to work competence. Adaptive coping includes problem solving and a sense of efficacy at handling problems, both of which may promote effective work functioning and management of stressors that occur in the workplace. Also, adolescents with higher levels of adaptive coping may also cultivate more positive employment and academic and interpersonal opportunities that lead to greater work competence. This finding is consistent with findings from studies of naturally occurring competence and resilience in the transition to adulthood (Masten et al., 2004).

In addition to these interactive and cascading effects, there was a significant positive path from intervention-induced improvements in parenting to work competence, suggesting that processes associated with positive parenting directly led to greater work competence in emerging adulthood. Perhaps by being more responsive, communicating more effectively, and having realistic expectations for their children’s behavior, mothers in the intervention shaped behaviors that facilitated later success in the workplace. It may also be that higher quality parent–child relationships were associated with higher expectations and aspirations for success in work settings or mothers’ use of effective discipline increased their offspring’s sense of being responsible for one’s actions, which is likely associated with higher work competence.

Academic competence

By emerging adulthood, some individuals have completed their academic careers, whereas others are in the midst of completing college or advanced degrees. Given that educational attainment influences future employment (Johnson & Mortimer, 2011) and mid-life career and life satisfaction (Chow, Galambos, & Krahn, 2017), a significant cascade effect from the program-induced effect on GPA in adolescence to educational attainment has implications for functioning beyond emerging adulthood. This within-domain continuity is consistent with the findings of passive, longitudinal research (French, Homer, Popovici, & Robins, 2015; Masten et al., 2005). This continuity may reflect the cumulative effect of early success on academic tasks to facilitate later academic competence through the use of skills and attitudes that are required for academic success as well as the stability of cognitive abilities and achievement motivation over development. This effect may also be partially due to the intervention’s effects on educational expectations in adolescence (Sigal et al., 2012). Given the well-documented positive relation between educational level and earnings and the compounding of earning differences across the lifespan (Day & Newburger, 2002), this program effect has important implications for reducing the public health burden of parental divorce.

Peer competence

Peer competence was significantly predicted by higher levels of adaptive coping in adolescence. It is possible that higher levels of adaptive coping are associated with skills that prevent, reduce, and resolve interpersonal problems. This finding and the finding that adaptive coping was associated with greater work competence extend the very limited literature on the relation between coping in adolescence and outcomes in adulthood (Hussong & Chassin, 2004; Wolchik et al., 2016) by focusing on competence rather than behavior problems.

Romantic competence

Romantic competence in emerging adulthood was not affected by participation in the intervention either directly or indirectly through the aspects of adolescent functioning that were tested. Although there was a significant correlation between adaptive coping in adolescence and romantic competence, in the context of the other variables this relation became nonsignificant. The current findings are in contrast to other work that found that academic competence and peer competence around age 20 predicted romantic relationships at about age 30 (Roisman, Masten, Coatsworth, & Tellegen, 2004).

Mediational Pathways From Program Participation to Competence in Emerging Adulthood

The mediational analyses identified cascading effects pathways that partially explained the intervention’s effects on three domains of competence in emerging adulthood. For peer competence, the indirect effects of the program were mediated by adaptive coping in adolescence for those who entered the program at high risk. For both work and academic competence, the long-term program effects were initiated by improvements in positive parenting at posttest, which led to cascading effects on externalizing problems in childhood and adolescence. In addition, for work competence, for those who entered the program at high risk, adaptive coping in adolescence mediated the long-term effect of the program. It is important to note that the power of detecting mediation effects with several mediators intervening in a series (i.e., cascade models) is smaller than the power of detecting mediation effects with only one mediator intervening between the independent and dependent variables (Taylor, MacKinnon, & Tein, 2008). Therefore, the results of the mediational analyses support the robustness of the observed cascading effects.

The findings of the current study highlight the critical role of quality of parenting in promoting positive adaptation across development. These findings are consistent with a large body of cross-sectional and longitudinal research that has identified positive parenting as a key resilience resource (Baumrind, 1971; Masten, 2001; Masten et al., 2004; Masten & Palmer, 2019; Werner, 2013). They are also consistent with a growing body of studies that have demonstrated that program-induced improvements in parenting mediated program effects on long-term behavior problems through multilinkage effects (Forgatch et al., 2009; Wolchik et al., 2016).

Unique Contributions

This study contributes to the literature on the long-term effects of prevention programs as well as the long-term effects of parental divorce in several ways. First, it extends previous research on the long-term effects of relatively short, evidence-based parenting-focused programs that have examined problem behaviors such as mental health problems, substance use, and risky sexual behavior (Sandler et al., 2019; Spoth, Clair, & Trudeau, 2014; Spoth, Trudeau, Redmond, & Shin, 2014; Trudeau et al., 2016; Wolchik et al., 2013, 2016) by its focus on competence. It also extends the findings of the studies of comprehensive, lengthy prevention programs that have shown long-term effects on competence (Hawkins et al., 2005; Reynolds et al., 2001; Schweinhart et al., 2005). Given the current emphasis on containing costs and ensuring that prevention programs achieve a reasonable return on investment (Forman et al., 2009; Fosco et al., 2014), the current findings have important implications for the potential effect on public health of the New Beginnings Program and other relatively short, evidence-based parenting interventions.

The second contribution relates to furthering our knowledge about the developmental processes that explain these long-term effects. In the early 1990s, Coie et al. (1993) argued that the field of prevention science needs long-term follow-up of intervention samples to identify the processes that account for changes in outcomes across developmental stages. However, only a handful of researchers have done this (Forgatch, Patterson, Degarmo, & Beldavs, 2009; Reynolds & Ou, 2011, 2016; Spoth et al., 2013, 2014; Trudeau et al., 2016; Wolchik et al., 2016), and nearly all of this research has focused on problem outcomes. The current study tracked developmental processes across three stages of development and identified links between program participation, parenting, changes in developmental processes in childhood and adolescence, and competence in emerging adulthood. This type of research not only strengthens causal inferences (Reynolds, Ou, & Topitzes, 2004), it also furthers theories about the spreading effects of both problems and competence across development.

The third contribution is that this study experimentally tested the power of high-quality parenting to affect meaningful outcomes in emerging adulthood. The program-induced improvements generated cascading effects on developmental processes that led to increased competence in emerging adulthood. Although there is a large literature on the role of high-quality parenting in promoting positive development, few studies have experimentally manipulated the quality of parenting and examined the effect of these improvements across multiple periods of development, and even fewer have examined multiple domains of competence.

This study also contributes to research on the effects of parental divorce. Parental divorce is associated with impairments in competence in childhood, adolescence, and adulthood. Although other studies have found program effects on competence in earlier developmental periods (Crosbie-Burnett & Newcomer, 1990; Pedro-Carroll & Cowen, 1985; Wolchik et al., 2007), this is the first study to show that a program for divorced families affected competence in emerging adulthood. That the program had effects on three of the four domains of competence that were examined and on outcomes that can be monetized, such as higher educational level and greater work competence, provides convincing evidence for the importance of disseminating this program.

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

There are limitations of this study that need to be noted. First, there are several limitations related to the sample. The sample was almost exclusively non-Hispanic White and middle class. It is unclear whether these findings generalize to other sociocultural groups. Also, because the families were enrolled in a trial of a preventive intervention for divorced families that included multiple eligibility criteria, additional concerns are raised about the generalizability of the findings. Further, the participating mothers had higher incomes and education as well as fewer children than refusers. Finally, although the analytical strategy that was used to deal with missing data likely diminished the effects of attrition (Graham, 2009), those who participated in the 15-year follow-up assessment had significantly higher internalizing problems and lower self-esteem than those who did not participate. These sample characteristics limit the generalizability of the findings. Second, the sample was relatively modest, which reduced the power to detect direct and indirect effects of the program as well as interactive effects. Third, the intervals between assessments varied widely because data collection was determined by the length of the intervention and our interest in conducting short-term and long-term follow-ups.

There are several areas that could advance our understanding of the interplay between positive parenting, competence, problem behaviors, and substance use over development. Given the nature of the sample, replicating the current findings with larger, community-based samples that are more diverse would be important. Replication with other groups of at-risk youths is also important. In addition, research with larger samples would provide a more rigorous examination of sex differences in these cascading effects. Further, future research should examine whether other relatively short parenting programs have effects on competence in emerging adulthood. The increased attention to public return on investment (National Research Council and Institute of Medicine, 2009; Institute of Medicine, 2014) reinforces the importance of examining the long-term effects of these prevention programs on both problem behaviors and competence.

Summary

The current study demonstrated that a relatively brief parenting prevention program for divorced families improved offspring’s competence in emerging adulthood. These program effects were accounted for by direct or indirect effects of program-induced improvements in quality of parenting. In the context of the previous studies on the New Beginnings Program, which have shown direct and indirect effects on a wide array of problem behaviors (Wolchik 2000, 2002, 2007, 2013, 2016) and cost savings of about $1,600/family as assessed in the year prior to the 15-year follow-up (Herman et al., 2015), the positive cascade effects of this program across developmental stages have important public health implications. Given the large number of children who experience parental divorce in the United States each year, the widespread implementation of the New Beginnings Program could significantly reduce the public health burden of parental divorce.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supplementary Material. The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S095457941900169X.

References

- Achenbach TM (1991a). Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist/4–18 and 1991 profile Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Department of Psychology. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM (1991b). Manual for the Youth Self-Report and 1991 profile Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, & Edelbrock C (1983). Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist and Revised Child Behavior Profile Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry. [Google Scholar]

- Amato PR (2001). Children of divorce in the 1990s: An update of the Amato and Keith (1991) meta-analysis. Journal of Family Psychology, 15, 355–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amato PR (2006). Marital discord, divorce, and children’s well-being: Results from a 20-year longitudinal study of two generations. In Clarke-Stewart A & Dunn J (Eds.), The Jacobs Foundation series on adolescence. Families count: Effects on child and adolescent development (pp. 179–202). New York, NY, USA: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Amato PR, & Anthony CJ (2014). Estimating the effects of parental divorce and death with fixed effects models. Journal of Marriage and Family, 76, 370–386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ, & Tanner JL (Eds.). (2006). Emerging adults in America: Coming of age in the 21st century Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Ayers TS, Sandler IN, West SG, & Roosa MW (1996). A dispositional and situational assessment of children’s coping: Testing alternative models of coping. Journal of Personality, 64, 923–958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes H, & Olson DH (1982). Parent–adolescent communication. In Olson D, McCubbin H, Barnes H, Larsen A, Muxen M, & Wilson M (Eds.), Family inventories ( pp. 33–49). St. Paul, MN: Family Social Sciences. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett AE, & Turner RJ (2006). Family structure and substance use problems in adolescence and emerging adulthood: Examining explanations for the relationship. Addiction, 101, 109–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumrind D (1971). Current patterns of parental authority. Developmental Psychology Monographs, 4, 1–103 [Google Scholar]

- Bhushan R, & Shirali KA (1992). Family types and communication with parents: A comparison of youth at different identity levels. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 21, 687–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SL, & Rinelli LN (2010). Family structure, family processes, and adolescent smoking and drinking. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 20, 259–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell FA, Ramey CT, Pungello E, Sparling J, & Miller-Johnson S (2002). Early childhood education: Young adult outcomes from the Abecedarian Project. Applied Developmental Science, 6, 42–57. [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi D, & Stoolmiller M (1999). Co-occurrence of conduct problems and depressive symptoms in early adolescent boys: III. Prediction to young-adult adjustment. Development and Psychopathology, 11, 59–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherlin AJ, Chase-Lansdale PL, & McRae C (1998). Effects of parental divorce on mental health throughout the life course. American Sociological Review, 63, 239–249. [Google Scholar]

- Chow A, Galambos NL, & Krahn HJ (2017). Work values during the transitition to adulthood and mid-life satisfaction: Cascading effects across 25 years. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 41, 105–114. [Google Scholar]

- Christopher C, Wolchik SA, Tein J-Y, Carr C, Mahrer NE, & Sandler I (2017). Long-term effects of a parenting preventive intervention on young adults’ painful feelings about divorce. Journal of Family Psychology, 31, 799–809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, & Schneider-Rosen K (1986). An organizational approach to childhood depression. In Rutter M, Izard CE, & Read PB (Eds.), Depression in young people, clinical and developmental perspectives (pp. 71–134). New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Coatsworth D, & Sandler IN (1993). Multi-rater measurement of competence in children of divorce. In Biennial Conference of the Society for Community Research and Action, Williamsburg, VA. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Taborga M, Dawson S, & Wolchik SA (2000). Do family routines buffer the effects of divorce stressors on children’s symptomatology? Presented at the Society for Prevention Research. Montreal, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Coie JD, Watt NF, West SG, Hawkins JD, Asarnow JR, Markman HJ, … Long B (1993). The science of prevention: A conceptual framework and some directions for a national research program. American Psychologist, 48, 1013–1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosbie-Burnett M, & Newcomer LL (1990). Group counseling children of divorce: The effects of a multimodal intervention. Journal of Divorce, 13, 69–78. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson-McClure SR, Sandler IN, Wolchik SA, & Millsao RE (2004). Risk as a moderator of the effects of prevention programs for children from divorced families: A six-year longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 32, 175–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day JC, & Newburger EC (2002) The big payoff: Educational attainment and synthetic estimates of work-life earnings Current Population Reports. U.S. Census Bureau, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Donahue KL, D’Onofrio BM, Bates JE, Lansford JE, Dodge KA, & Pettit GS (2010). Early exposure to parents’ relationship instability: Implications for sexual behavior and depression in adolescence. Journal of Adolescent Health, 47, 547–554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doty JL, Davis L, & Arditti JA (2017). Cascading resilience: Leverage points in promoting parent and child well-being. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 9, 111–126. [Google Scholar]

- Elder GH (2002) Historical times and lives: A journey through time and space. In Phelps E, Furstenberg FF, & Colby A (Eds.), Looking at lives: American logitudinal studies of the twentieth century (pp. 194–218). New York: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Erdogan B, Bauer TN, Truxillo DM, & Mansfield LR (2012). Whistle while you work:A review of the life satisfaction literature. Journal of Management, 38, 1038–1083. [Google Scholar]

- Forgatch MS, & DeGarmo DS (1999). Parenting through change: An effective prevention program for single mothers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 67, 711–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forgatch MS, Patterson GR, Degarmo DS, & Beldavs ZG (2009). Testing the Oregon delinquency model with 9-year follow-up of the Oregon Divorce Study. Development and Psychopathology, 21, 637–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forman S, Olin SS, Hoagwood K, Crowe M, & Saka N (2009). Evidence-based interventions in schools: Developers’ views of implementation barriers and facilitators. School Mental Health, 1, 26–36. [Google Scholar]

- Fosco G, Seeley J, Dishion T, Smolkowski K, Stormshak E, Downey-McCarthy R, … Strycker L (2014). Lessons learned from scaling up the ecological approach to family interventions and treatment program in middle schools. In Weist MD, Lever NA, Bradshaw CP, & Owens JS (Eds.), Handbook of school mental health (pp. 237–251). New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- French MT, Homer JF, Popovici I, & Robins PK (2015). What you do in high school matters: High school GPA, educational attainment, and labor market earnings as a young adult. Eastern Economic Journal, 41, 370–386. [Google Scholar]

- Gähler M, Hong Y, & Bernhardt E (2009). Parental divorce and union disruption among young adults in Sweden. Journal of Family Issues, 30, 688–713. [Google Scholar]

- Graham J (2009). Missing data analysis: Making it work in the real world. Annual Review of Psychology, 60, 549–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins J, Kosterman R, Catalano RF, Hill KG, & Abbott RD (2005). Promoting positive adult functioning through social development intervention in childhood: Long-term effects from the Seattle social development project. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 159, 25–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins J, Kosterman R, Catalano RF, Hill KG, & Abbott RD (2008). Effects of social development intervention in childhood 15 years later. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 162, 1133–1141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman P, Mahrer NE, Wolchik SA, Porter MM, Jones S, & Sandler IN (2015). Cost-benefit of a preventive intervention for divorced families: Reduction in mental health and justice system service use costs 15 years later. Prevention Science, 16, 586–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill K, Bailey J, Hawkins JD, Catalano R, Kosterman R, Oesterle S, & Abbott R (2014). The onset of STI diagnosis through age 30: Results from the Seattle Social Development Project Intervention. Prevention Science, 15, 19–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu LT, and Bentler PM (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Hussong AM, & Chassin L (2004). Stress and coping among children of alcoholic parents through the young adult transition. Development and Psychopathology, 16, 985–1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. (1994). Reducing risks for mental disorders: Frontiers for preventative intervention research Washington, DC: National Academy Press. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. (2014). Considerations in applying benefit-cost analysis to preventive interventions for children, youth and families. Workshop Summary Washington, DC: The National Academies of Science. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine & National Institute of Mental Health. (1990). Research on children & adolescents with mental, behavioral, & developmental disorders: Mobilizing a national initiative: Report of a study Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration, National Institute of Mental Health. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen ES, Boyce WT, & Hartnett SA (1983). The Family Routines Inventory: Development and validation. Social Science Medicine, 17, 201–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MK, & Mortimer JT (2011). Origins and outcomes of judgments about work. Social Forces, 89, 1239–1260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, Bachman JG, & O’Malley PM (1993). Monitoring the future: Questionnaire responses from the nation’s high school seniors Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan, Survey Research Center. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, McLaughlin KA, Green JG, Gruber MJ, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, … & Benjet C (2010). Childhood adversities and adult psychopathology in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 197, 378–385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HS (2011). Consequences of parental divorce for child development. American Sociological Review, 76, 487–511. [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M (1981). Rating scales to assess depression in school aged children. Acta Paedopsychiatry, 46, 305–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreider R, & Ellis R (2011) Living arrangements of children: 2009 (Report number 70–126) Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau. [Google Scholar]

- Kunz J (2001). Parental divorce and children’s interpersonal relationships: A meta-analysis. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage, 34, 19–47. [Google Scholar]

- Lacey RE, Kumari M, & McMunn A (2013). Parental separation in childhood and adult inflammation: The importance of material and psychosocial pathways. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 38, 2476–2484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson K, & Halfon N (2013). Parental divorce and adult longevity. International Journal of Public Health, 58, 89–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord FM, & Novick MR (1968.) Statistical theories of mental test scores Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JF, West SG, & Sheets V (2002). A comparison of methods to test the significance of the mediated effect. Psychological Methods, 7, 83–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahrer ME, Winslow E, Wolchik SA, Tein JY, & Sandler IN (2014). Effects of a preventive parenting intervention for divorced families on the intergenerational transmission of parenting attitudes in young adult offspring. Child Development, 85, 2091–2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS (2001). Ordinary magic: Resilience processes in development. American Psychologist, 56, 227–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Burt KB, & Coatsworth JD (2006). Competence and psychopathology in development. In Cicchetti D & Cohen DJ (Eds.), Developmental psychopathology: Vol. 3. Risk, disorder, and adaptation (2nd ed., pp. 696–738). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Burt KB, Roisman GI, Obradović J, Long JD, & Tellegen A (2004). Resources and resilience in the transition to adulthood: Continuity and change. Development and Psychopathology, 16, 1071–1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, & Cicchetti D (2010). Developmental cascades. Development and Psychopathology, 22, 491–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Coatsworth JD, Neemann J, Gest SD, Tellegen A, & Garmezy N (1995). The structure and coherence of competence from childhood through adolescence. Child Development, 66, 1635–1659. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Desjardins CD, McCormick CM, Kuo SIC, & Long JD (2010). The significance of childhood competence and problems for adult success in work: A developmental cascade analysis. Development and Psychopathology, 22, 679–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, & Palmer AR (2019). Parenting to promote resilience in children. In Bornstein MH (Ed.), Handbook of parenting (3rd ed., Vol. 5. The practice of parenting, pp. 156–188). New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Roisman GI, Long JD, Burt KB, Obradović J, Riley JR, … Tellegen A (2005). Developmental cascades: Linking academic achievement and externalizing and internalizing symptoms over 20 years. Developmental Psychology, 41, 733–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]