Abstract

Objectives

Dental anxiety remains widespread among children, may continue into adulthood and affect their oral health-related quality of life and clinical management. The aim of the study was to explore the trend of children’s dental anxiety over time and potential risk factors.

Design

Longitudinal study.

Methods

Children aged between 5 and 12 years were investigated with the Chinese version of face version of Children’s Fear Survey Schedule-Dental Subscale (CFSS-DS) and Frankl Behavior Rating scale from 2008 to 2017, and influential factors were explored.

Results

Clinical data were available from 1061 children, including 533 (50.2%) male participants and 528 (49.8%) female participants. The total CFSS-DS scores ranged from 16 to 66, with a mean of 24.8±10.3. The prevalence of dental anxiety is 11.59%. No significant differences in total CFSS-DS scores between girls and boys were found. According to the Frankl scale, 238 children were allocated to the uncooperative group and the remaining 823 children were allocated to the cooperative group. Scores of CFSS-DS were negatively correlated with the clinical behaviour level of Frankl. Children aged 11–12 years old had significantly decreased scores compared with other age groups, and there was a decline in the scores of the group aged 8–10 years old over time. The factor analysis divided 15 items of CFSS-DS into four factors, and the total scores of ‘less invasive oral procedures’ items belonging to factor III decreased significantly over time in the group aged 8–10 years old.

Conclusions

Age is a significant determinant for children’s dental anxiety, and dental anxiety outcomes have improved for Chinese children aged 8–10 years. This study is one of the few reports on changes of children’s dental anxiety in a new era of information, but the results may be extrapolated to other populations with caution.

Keywords: child protection, anxiety disorders, public health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study is a systematic longitudinal survey with representative data obtained for comparison of time trends of children’s dental anxiety in multiple age groups.

The duration of this observational study spanned a decade.

The Chinese version Children’s Fear Survey Schedule-Dental Subscale with facial image scale showed good applicability in clinical practice.

Tri-blindness paradigm was employed to avoid bias as much as possible.

The sample size of this survey, the region and age range of the research objects are limited.

Introduction

Dental fear and anxiety refers to a feeling of dread and anticipation that something will happen, combined with a sense of losing control in relation to dentistry. Dental phobia is defined as a more severe form that leads to an out-of-proportion reaction and interferes in daily life.1 A significant problem in patient management as such patients are more likely to avoid or delay dental treatment is related to dental anxiety, further leading to a vicious cycle where the levels of dental anxiety are reinforced as a result of greater disease severity and greater dental treatment needs.2 3

Childhood dental anxiety has been shown to be widespread, and research has suggested that adults often acquire such fears in childhood,4 and the early-life social and biological factors have long-lasting effects on health later in life.5 A child’s dental anxiety predicts more dental disease and poorer oral health in measures, such as decay experience, the presence of untreated dental infection and treatment that carries more risk, that results in a detrimental effect on the quality of the life of the individual and family, and engagement in oral health-related behaviours.6 7 For many years, dental anxiety in children has been recognised as a source of problems in patient management.8 Identifying anxiety in children at the earliest possible age is essential and helpful to select methods of behaviour management. In the literature of recent years, there is considerable variation in the designs of study and target populations, particularly in the scales used for measurement and the age of the children, so that the reported prevalence of dental fear and anxiety in children varies widely, ranging from 7.4%9 to 93.8%.10 It can be said that there is currently no fully ideal dental anxiety scale for children in use. Efforts should therefore continue to be directed towards the development and validation of suitable instruments for the detection of dental anxiety in children.

The Dental Subscale of Children’s Fear Survey Schedule (CFSS-DS) is a frequently used measure of children’s dental anxiety.11 Then the facial version CFSS-DS was first proposed by Arapostathis et al in 2007.12 In several countries, the scale has demonstrated good reliability and acceptable validity and has been used to estimate the prevalence of dental anxiety and evaluate the behaviour-management procedures used for child patients. The Chinese version CFSS-DS established the cross-cultural adaptation and showed good psychometric properties.13 The prevalence of dental anxiety according to CFSS-DS varies considerably in the international literature ranging from 2.4% to 28.3% in different populations and cultural backgrounds.9 14–16

The aetiology of dental anxiety is complex and multifactorial. Numerous factors were discussed as influences of children’s dental anxiety, with socioeconomic factors, general health, dental history and caregiver status being frequently included aspects.17 Poor oral health and hygiene behaviour, unstable general health and parents’ high dental anxiety were found to be associated with elevated levels of children’s dental anxiety. Children with toothache or caries have higher chance of dental anxiety.18 Patterns of dental visits and previous experiences have also important impact on dental fear occurrence.19 Studies demonstrated that subjects with higher social and financial resources show lower prevalence of dental anxiety.20 The potential risk factors of dental anxiety are likely to be different from each person. Thus, further investigation into intrinsic and environmental factors associated with dental anxiety is needed. To date, relatively few published studies evaluated the dental anxiety of children and behavioural influence factors in dental settings in China. Moreover, the trends of children’s dental anxiety over time are poorly characterised. The objective of this research is to provide normative data on dental anxiety of Chinese children, and describe and compare the influence of relevant factors on dental anxiety in a decade.

Methods

Participants and procedures

The study was conducted at the department of Pediatric Stomatology, affiliated Stomatology Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University, during 10 years (August 2008–October 2017). The children patients aged 5–12 years old were selected randomly to participate in the study. Inclusion criteria were children with no mental retardation or developmental disorders; no cognitive impairment or psychiatric history; no serious congenital and acquired oral and maxillofacial deformities. Before entering the study, each parent and child were well informed about the purpose of the study and affirmed that participation was voluntary. Parents were distributed informative leaflets about the procedure and were asked to provide written consent.

Chinese version CFSS-DS with Facial Image Scale

The Chinese version CFSS-DS was adopted, which consists of 15 items and a 5-point pictorial scale, that is, the Facial Image Scale (FIS). The FIS consists of five drawings of a face, displaying affective features ranging from extremely negative (score 5) through neutral to extremely positive (score 1). The total score ranges from 15 to 75. Children are presented with the five images and are asked to select which one best corresponds to how they are feeling. The FIS is a reliable and valid method for children’s self-report of dental anxiety in subjects as young as 3 years old.21 22 In this study, the pilot test of Chinese version CFSS-DS with FIS was carried out on 32 children and their parents, in order to clarify whether young children could answer the CFSS-DS items with reference to the facial images (results not shown).

Measures

Children’s dental anxiety over the 10-year period was investigated, which was a randomised triple-blinded longitudinal study. Data collection included children’s completion of the Chinese version CFSS-DS with FIS and evaluation of behaviour during dental visit. Upon entering the waiting room, the children were invited to fill in the Chinese version CFSS-DS with FIS. Any child experiencing difficulty in reading the questions was assisted by the receptionist. At the same time, the parents (in almost all cases, the mother) were provided a dental health questionnaire related to demographic information and previous dental experiences. The gender, age and source of referral of the participants were recorded. After the completion of the CFSS-DS, the children were invited into the operatory for regular dental examination. The dentist and dental nurse were unaware of the children’s responses to the questionnaire. During examinations, the behaviour and facial expressions of the children were recorded by video cameras, which were later rated according to the Frankl scale.23 To ensure sample ‘blindness’, the rater did not have access to the CFSS-DS scores of the children and assigned the children with behaviours classified as ‘definitely positive’ (the dentist and child share good rapport, the child is laughing) and ‘positive’ (willingness to comply, cautiousness) to the cooperative group, whereas those with behaviours classified as ‘definitely negative’ (fearful behaviour, forceful crying) and ‘negative’ (reluctance and/or uncooperativeness, but not as severe as in the previous category) were assigned to the uncooperative group.

Data processing and statistical analysis

The data from all the children who had completed the Chinese version CFSS-DS and finished the dental examination on one occasion were used to provide normative data. If there is one item in one scale that is not answered, it will be treated as a missing item, and the data of missing entries are replaced by the mean of the remaining samples with complete data; if there are two or more items that are not answered, they will be eliminated from the invalid scale.

Data management and analysis were conducted using SPSS V.16.0. The associations between CFSS-DS scores and demographic variables were analysed using the t-tests and one-way analysis of variances. When significant effects were found, Tukey post-hoc test was used to determine significant intergroup mean differences. Factor analysis (principal components, varimax rotation) was employed to assess the factor structure,24 25 and factor scores above 0.5 indicate strong loading on a particular subset of items. Kruskal-Wallis rank-sum test was used to evaluate the differences of gender groups and age groups among three time periods. P<0.05 is statistically significant.

Patient and public involvement

Participation in this survey is voluntary for each child and his/her parents. The receptionists or assistants helped the children understand the items and complete the scale. The children and their parents were not involved in the design, recruitment or conduct of the study.

Results

Characterisation of the sample

For the analysis of dental anxiety in children, the representative sample selected randomly who were treated in the Department of Pediatric Stomatology, and 1061 copies of the effective scale were received from August 2008 to October 2017. Of those eligible, there were 533 (50.2%) male participants and 528 (49.8%) female participants. There was no significant difference in the ratio of patient’s gender, or their evaluation of economic level by treatment status. Four hundred eleven children aged 5–7 years accounted for 38.7%, 399 children aged 8–10 years accounted for 37.6% and 251 aged 11–12 years accounted for 23.7% (table 1). The mean age of the children was 7.8 years (SD 1.7). Gender and age distributions remained stable over time, with increasing proportions of respondents in higher family income categories.

Table 1.

Gender and age distribution of the survey sample

| Sample characteristics | N | % |

| Age (years) | ||

| 5–7 | 411 | 38.7 |

| 8–10 | 399 | 37.6 |

| 11–12 | 251 | 23.7 |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 528 | 49.8 |

| Male | 533 | 50.2 |

N=total number of children.

Dental anxiety of children and behaviour classification

Table 2 shows the 1061 participants’ scores in the CFSS-DS to dental practice events. Items that over 25% children felt ‘very afraid’ or ‘quite afraid’ were ‘Dentist drilling’ (46.84%), ‘Injection’ (29.50%) and ‘Choking’ (26.20%). Range of total CFSS-DS scores was 16~66. The mean total CFSS-DS scores for all children was 24.8±10.3. We assigned those children with CFSS-DS total scores equal to and below 32 to ‘non-fearful range’, scores between 32 and 38 to ‘borderline range’, and scores of 38 and higher as ‘fearful range’.14 26–32 From the children assessed, 605 children (57.02%) were rated as the non-fearful range, 333 (31.39%) were rated as the borderline range and 123 (11.59%) were rated as fearful range. Therefore, the prevalence of dental anxiety in this sample is 11.59%, and 88.41% of the children did not suffer from it. According to the Frankl scale, 238 children assessed were allocated to the uncooperative group and the remaining 823 children were allocated to the cooperative group. The distribution patterns of CFSS-DS scores were very different between the two groups. Children of the uncooperative group tended to report dental anxiety, as compared with cooperative children (30.67% vs 6.08%) (table 3). The results showed that the CFSS-DS scores were correlated negatively with the Frankl behaviour level. That is, there is a certain consistency between the CFSS-DS score and the clinical performance.

Table 2.

Children’s dental anxiety in the Chinese version CFSS-DS

| Items | Total (N=1061) | |||||

| Not afraid | A little afraid | Fairly afraid | Quite afraid | Very afraid | ||

| 1 | Dentists | 461 (43.44%) | 324 (30.54%) | 131 (12.35%) | 65 (6.13%) | 80 (7.54%) |

| 2 | Doctors | 528 (49.76%) | 290 (27.33%) | 94 (8.86%) | 65 (6.13%) | 84 (7.92%) |

| 3 | Injections | 268 (25.26%) | 281 (26.48%) | 199 (18.76%) | 144 (13.57%) | 169 (15.93%) |

| 4 | Having someone examine your mouth | 519 (48.92%) | 334 (31.48%) | 163 (15.36%) | 27 (2.54%) | 18 (1.70%) |

| 5 | Having to open your mouth | 741 (69.84%) | 192 (18.10%) | 97 (9.14%) | 15 (1.41%) | 16 (1.51%) |

| 6 | Having a stranger touch you | 262 (24.69%) | 299 (28.18%) | 243 (22.90%) | 136 (12.82%) | 121 (11.40%) |

| 7 | Having somebody look at you | 504 (47.50%) | 293 (27.62%) | 187 (17.62%) | 62 (5.84%) | 15 (1.41%) |

| 8 | Dentist drilling | 109 (10.27%) | 203 (19.13%) | 252 (23.75%) | 241 (22.71%) | 256 (24.13%) |

| 9 | Sight of the dentist drilling | 431 (40.62%) | 237 (22.33%) | 183 (17.25%) | 134 (12.63%) | 76 (7.16%) |

| 10 | Noise of the dentist drilling | 369 (34.78%) | 303 (28.56%) | 154 (14.51%) | 90 (8.48%) | 145 (13.67%) |

| 11 | Having somebody put instruments in your mouth | 416 (39.21%) | 237 (22.34%) | 175 (16.49%) | 113 (10.65%) | 120 (11.31%) |

| 12 | Choking | 351 (33.08%) | 313 (29.50%) | 119 (11.22%) | 156 (14.70%) | 122 (11.50%) |

| 13 | Having to go to the hospital | 454 (42.79%) | 308 (29.03%) | 204 (19.23%) | 29 (2.73%) | 66 (6.22%) |

| 14 | People in white uniforms | 649 (61.17%) | 157 (14.80%) | 147 (13.85%) | 76 (7.16%) | 32 (3.02%) |

| 15 | Having the nurse clean your teeth | 582 (54.86%) | 149 (14.04%) | 175 (16.49%) | 69 (6.50%) | 86 (8.11%) |

N=total number of children.

CFSS-DS, Children’s Fear Survey Schedule-Dental Subscale.

Table 3.

CFSS-DS scores and the children behaviour in the Frankl scale

| CFSS-DS scores |

Behaviour classification N (%) |

Total | |

| Cooperative group (Frankl scale: 3 or 4) |

Uncooperative group (Frankl scale: 1 or 2) |

||

| ≤32 | 577 (70.11) | 28 (11.76) | 605 (57.02) |

| 32−38 | 196 (23.82) | 137 (57.56) | 333 (31.39) |

| ≥38 | 50 (6.08) | 73 (30.67) | 123 (11.59) |

| Total | 823 | 238 | 1061 |

N=total number of children.

CFSS-DS, Children’s Fear Survey Schedule-Dental Subscale.

Dental anxiety of children and gender, age and time factors

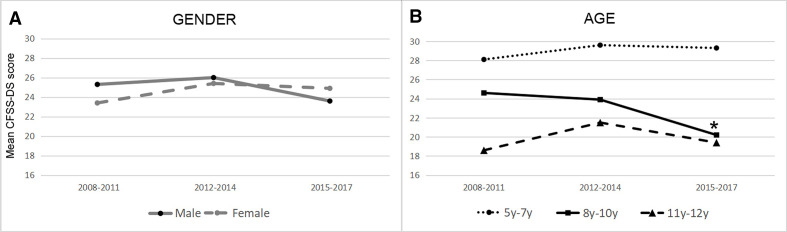

The results in table 4 show the CFSS-DS scores of gender groups and age groups between 2008 and 2017. There was no statistical difference in CFSS-DS scores between boys and girls, and within the two groups among the three time periods during 10 years, indicating that there was no significant correlation between gender and dental anxiety (figure 1A). On the other hand, age was statistically significantly related to CFSS-DS score. The overall data indicated that children aged 11–12 years old had significantly decreased scores compared with other age groups. Over time, there was a decline of the CFSS-DS scores in the group aged 8–10 years old. The children of this group in 2015–2017 were found with significantly lower CFSS-DS score compared with peers in 2008–2011 (figure 1B, p=0.019). The other two age groups did not show significant trends over time.

Table 4.

Mean CFSS-DS scores by gender and age

| Variables | 2008–2011 | 2012–2014 | 2015–2017 | |||

| N=299 | N=367 | N=395 | ||||

| N (%) | CFSS-DS score Mean (SD) |

N (%) | CFSS-DS score Mean (SD) |

N (%) | CFSS-DS score Mean (SD) |

|

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 152 (50.8) | 25.3 (10.2) | 172 (46.9) | 26.0 (10.1) | 209 (52.9) | 23.6 (10.3) |

| Female | 147 (49.2) | 23.4 (9.9) | 195 (53.1) | 25.4 (9.9) | 186 (47.1) | 24.9 (10.5) |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| 5–7 | 113 (37.8) | 28.1 (9.7) | 148 (40.3) | 29.6 (10.2) | 180 (45.6) | 29.3 (10.3) |

| 8–10 | 110 (36.8) | 24.6 (10.4) | 143 (39.0) | 23.9 (9.8) | 146 (37.0) | 20.2 (10.6)* |

| 11–12 | 76 (25.4) | 18.6 (10.4) | 76 (20.7) | 21.5 (10.1) | 69 (17.4) | 19.4 (10.3) |

| Mean | 24.4 (10.0) | 25.7 (10.2) | 24.2 (10.4) | |||

N=total number of children.

*Statistically significant (p<0.05).

CFSS-DS, Children’s Fear Survey Schedule-Dental Subscale.

Figure 1.

CFSS-DS scores by gender (A) and age (B). *Statistically significant (p<0.05). CFSS-DS, Children’s Fear Survey Schedule-Dental Subscale.

Factor analysis

This study conducted factor analysis of the Chinese version CFSS-DS (maximum variation method). The 15 items were divided into four factors, which accounted for 58.7% of the total scale variance. Factor I, accounting for 22.6% of the variance, consists of items pertaining to highly invasive dental procedures, such as ‘Dentists’ and ‘Drilling’. Factor II consists of items related to general medical aspects of treatment, such as ‘Doctors’. Factor III consists of items pertaining to less invasive procedures and potential ‘victimisation’, such as ‘Having someone examine your mouth’. Factor IV consists of items related to the distrust of strangers or unfamiliar objects, which were unrelated to general medical aspects of treatment, such as ‘Having a stranger touch you’. Corrected item–domain correlation ranged from 0.58 to 0.90. A certain logical relationship among the items in the same factors was observed. When stratified analysis was carried out in the group aged 8–10 years old, the children in 2015–2017 reported significantly lower summed scores on items belonging to factor III compared with peers in 2008–2011, while no significant differences were seen in items for the other three factors, indicating a decreasing trend in anxiety levels over time for the ‘less invasive procedures’ items (factor III) (table 5, p=0.041).

Table 5.

Factor analysis and scores of items with respect to the factors in the group aged 8–10 years

| Rotated CFSS–DS factor matrix | Factors (% total scale variance) | Mean CFSS-DS score of children aged 8–10 years old | |||||||

| Items in CFSS-DS | I (22.6) |

II (17.3) |

III (12.1) |

IV (7.9) |

2008–2011 | 2012–2014 | 2015–2017 | ||

| I | Highly invasive dental procedures | 12.63 | 12.06 | 11.08 | |||||

| 1 | Dentists | 0.492 | 0.451 | 0.285 | 0.031 | ||||

| 8 | Dentist drilling | 0.816 | 0.187 | 0.123 | 0.074 | ||||

| 9 | Sight of the dentist drilling | 0.792 | 0.113 | 0.084 | 0.165 | ||||

| 10 | Noise of the dentist drilling | 0.608 | 0.242 | 0.136 | 0.045 | ||||

| 11 | Having somebody put instruments in your mouth | 0.714 | 0.138 | 0.202 | 0.087 | ||||

| 12 | Choking | 0.513 | 0.311 | −0.146 | 0.378 | ||||

| 15 | Having the nurse clean your teeth | 0.442 | 0.191 | 0.285 | 0.011 | ||||

| II | General medical aspects of treatment | 5.31 | 6.21 | 5.23 | |||||

| 2 | Doctors | 0.341 | 0.568 | 0.099 | 0.151 | ||||

| 3 | Injections | 0.124 | 0.633 | 0.021 | 0.012 | ||||

| 13 | Having to go to the hospital | 0.169 | 0.696 | 0.118 | 0.156 | ||||

| 14 | People in white uniforms | 0.086 | 0.618 | 0.304 | 0.077 | ||||

| III | Less invasive procedures and potential ‘victimisation’ | 4.15 | 3.01 | 2.03* | |||||

| 4 | Having someone examine your mouth | 0.256 | 0.303 | 0.764 | 0.099 | ||||

| 5 | Having to open your mouth | 0.233 | 0.034 | 0.657 | 0.113 | ||||

| IV | Distrust of strangers or unfamiliar objects | 2.59 | 2.72 | 2.56 | |||||

| 6 | Having a stranger touch you | 0.201 | 0.189 | −0.037 | 0.821 | ||||

| 7 | Having somebody look at you | 0.021 | 0.016 | 0.270 | 0.807 | ||||

*Statistically significant (p<0.05).

CFSS-DS, Children’s Fear Survey Schedule-Dental Subscale.

Discussion

Children commonly experience anxiety when receiving professional dental treatment. Effectively recognising an anxious patient, while being based on the validity of clinical observations, is a recognised problem for both dentists and researchers. CFSS-DS is an international survey tool for children’s dental anxiety that covers basically all aspects of dental events and can be used for epidemiological investigations, controlled trials and longitudinal prospective studies. This study adopted the Chinese version CFSS-DS that has undergone cross-cultural adaptation, and the results showed that the high rate of the scale recovery and the low rate of missing items indicating good feasibility. Children may be well able to assess their fear using the face version CFSS-DS, however, their incomprehension of the content of individual items is the main reason for the lack of data, which focused on item 12 ‘Choking’. In addition, it was found that in the preliminary test, children aged 4 years and below cannot accurately grasp the meaning of most items. This study believes that as a self-assessment scale, CFSS-DS must be understood by the surveyed population. In view of this, this study selected children aged 5–12 years old as the survey objects.

In this study, there is a negative correlation between the anxiety level of children obtained by the CFSS-DS and the clinical behaviour classification, indicating that children with high anxiety levels have poor clinical cooperation. Our finding suggested that the distribution patterns of the total CFSS-DS scores were clearly different between the clinical behaviour groups according to Frankl scale. In the cooperative group, although the younger child patients exhibited high scores of dental anxiety, they had the potential to overcome their resistance behaviours of dental treatment, indicating that cooperative patients can have hidden dental anxiety. Therefore, even in the face of cooperative children during dental treatment, it should be taken into account that clinicians may be required to implement appropriate behavioural induction measures to reduce dental anxiety. It has been suggested that dental anxiety decreases with repeated exposure to dental procedures.33 However, in the uncooperative group, older children seemed not to be able to overcome their dental anxiety, which caused behaviour management problems. At this time more risk factors should be considered, such as previous medical experience and family structure.

The CFSS-DS scores in the international literature in recent years vary with different populations and dental situations. The mean score in the present study was 24.8±10.3, which was comparatively lower than scores from studies in Brazil (29.3±10.5),34 Hong Kong (29.1±11.0),16 Greece (27.1±10.8),14 Egypt (26.09±10.70)26 and Jeddah, Saudi Arabia (25.99±9.3).17 CFSS-DS scores in the current study did not differ greatly from data from these previous studies, that may be due to the similar age range of the subjects and different cultural parameters.

It is necessary to determine the cut-off point for distinguishing between children who are more prone to dental anxiety that is helpful for clinicians to choose appropriate behaviour management measures. Generally, dental anxiety is measured according to clear cut-off points on continuous measure that acts as a categorical boundary. In view of the balance of the sensitivity and specificity in the measurement of scale, different prevalence estimates depend on the different cut-off values used to define ‘dental anxiety’. Children’s dental anxiety cut-off points on CFSS-DS are already defined in several researches, but the conclusions are not all the same. In the present study, the children participants with CFSS-DS scores of 38 and higher26–32 were considered as dentally anxious. There is still a need for further research to find more desirable instrument for understanding the dental anxiety of children and adolescents.

Demographically, this study found no difference in dental anxiety between girls and boys, that is supported by previous studies.14 20 34–39 This is however contrary to other studies which have reported more girls than boys in the anxious group.12 17 26 Contradictory research findings may be explained by different study designs and methods of data collection, moreover, gender influences should be regarded in combination with other factors such as local culture and socioeconomic status of the family.

Bad dental experience is considered as one of life-long stress situations for children.40 As cultural and social behavioural norms can affect the development and expression of children’s dental anxiety, and as dental care systems can vary considerably across cultures, normative data in each culture are needed. The main strength of this study was the continuous assessment over a 10-year period, which provides information on the development and progression of dental anxiety during the important life course, when children’s transition from the primary to the permanent dentition and mental state grows enormously. To our knowledge, this is the first study to use representative data from China for comparison of time trends of children’s dental anxiety in multiple age groups. The study showed that dental anxiety seems to decrease with increasing age and this is in agreement with previous studies.17 The results showed that children aged 8–10 years old in recent years exhibited less fear and anxiety in dental procedures compared with children of the same age in the initial period of this study, indicating that the change in social environment experienced in these years influences the incidence and progression of dental anxiety and its outcomes have improved for children in Guangdong Province. The researchers conclude that the possible reasons for these findings would be the oral health education in the mass media, especially the internet, which has enhanced the cognition and acceptance of oral treatment for the older children. But the effect was not obvious to preschool children because of their limited cognitive ability. However, children’s dental anxiety was influenced by a multiplicity of interacting environmental factors including words and deeds of people around; any single influence is dubious to clarify much divergence. So the positive trend of parents towards dental procedures may be passed on to children indirectly, which may also be due to the growing public awareness.

Factor analyses, which are conventionally used to evaluate the construct validity of scales, have been previously reported in CFSS-DS studies of different populations. In the Netherlands and Finland, investigators divided the scale items into three factors, and the connotations of them were as follows: (1) fear of highly invasive procedures, (2) fear of potential ‘victimisation’ and (3) fear of less invasive procedures.24 In the present research, factor analysis resulted in four factors based on deep sources of children’s dental anxiety. There were (1) fear of highly invasive dental procedures, (2) fear of general medical aspects of treatment, (3) fear of less invasive procedures and potential ‘victimisation’, and (4) fear of strangers or unfamiliar objects. Despite minor differences in populations and methods, similar results were found in the aforementioned studies in other cultures,4 41 indicating that the setting of psychological and behavioural scale conforms to the theoretical conception of the design in this study. The results of factor analysis also provided some support for the conclusion above: in the group aged 8–10 years old, the less invasive oral operation items (factor III) showed the trend of decreasing dental anxiety scores, while the changes of other factors were not significant, thus indicating that the downward trend in the total CFSS-DS scores may have originated from the items of factor III. It can be explained that the image output in oral health publicity is indeed considered to make patients have a certain degree of familiarity with the treatment situation before coming to the hospital, so as to reduce the anxiety tendency to a certain extent. This also suggests that future public oral health publicity should be introduced to the scene of positive emotional feedback from the characters about the sight and noise of the ‘drilling’ (factor I), in order to further reduce the public’s fear of specific dental operations.

The limitation to our study design should be pointed out. The sample was taken from a single medical institution, which the group of children represented by is more inclined to show the behaviour of visiting a dentist, probably because of lower levels of dental anxiety.42 The generalisability of our results cannot be directly extrapolated to broader urban populations. Hence, a school sample is generally considered more representative. However, the school sample may have introduced recall bias, and children without dental experience are likely to have difficulty answering items such as ‘drilling’ that they had never experienced previously.12 43 44 There may be a need for a comparative study between the clinic and school samples. Another limitation of the present study is that the presence of parents when children respond to the scale reduced privacy, which may lead to the children’s answering in line with parents' expectations and social expectations. Perhaps this problem could be mitigated by having the items interpreted by the investigators rather than the parents. Additionally, considering that dental anxiety is multicausal, such as the kind of treatment, previous dental experience of children and other events involved, future studies are required to further relate CFSS-DS scores to broader risk factors and/or physiological observations of children during dental treatment, then the tool will help clinicians recognise children in need of extra attention and subsequently select the most appropriate treatment approach and evaluate the outcome of interventions.

Conclusions

The assessment in this study provides an overall picture of dental anxiety in Chinese-speaking populations, age is significant determinant for children’s dental anxiety. Furthermore, in recent years, part of children’s dental anxiety tends to decrease with time.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the volunteers and patient advisers for their valuable participation, and Cuthbert and Melamed for the original CFSS-DS design, and the individuals who piloted the surveys and provided further feedback during the investigation.

Footnotes

Contributors: SG contributed to the data analysis and manuscript preparation. JL and PL contributed to the material preparation and data collection. WZ and DY supervised the data collection, data analysis and critical revisions. All authors contributed to the study conception and design and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This study was supported by the Research Fund of the Department of Health of Guangdong Province (WSTJJ20061120), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81974146, 81873711), the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (2014A030313126), and the Science and Technology Planning Project of Guangdong Province (2016A020215094) to WZ.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

All procedures performed involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Ethics Committee of the Institute of Stomatological Research, Sun Yat-sen University, China. Informed written consent was taken from parents of each participating child.

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xiang B, Wong HM, Perfecto AP, et al. The association of socio-economic status, dental anxiety, and behavioral and clinical variables with adolescents' oral health-related quality of life. Qual Life Res 2020;29:2455–64. 10.1007/s11136-020-02504-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Wijk AJ, Hoogstraten J. Experience with dental pain and fear of dental pain. J Dent Res 2005;84:947–50. 10.1177/154405910508401014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wogelius P, Poulsen S, Sørensen HT. Prevalence of dental anxiety and behavior management problems among six to eight years old Danish children. Acta Odontol Scand 2003;61:178–83. 10.1080/00016350310003468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Celeste RK, Eyjólfsdóttir HS, Lennartsson C, et al. Socioeconomic life course models and oral health: a longitudinal analysis. J Dent Res 2020;99:257–63. 10.1177/0022034520901709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coxon JD, Hosey MT, Newton JT. The impact of dental anxiety on the oral health of children aged 5 and 8 years: a regression analysis of the child dental health survey 2013. Br Dent J 2019;227:818–22. 10.1038/s41415-019-0853-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coxon JD, Hosey M-T, Newton JT. The oral health of dentally anxious five- and eight-year-olds: a secondary analysis of the 2013 child dental health survey. Br Dent J 2019;226:503–7. 10.1038/s41415-019-0148-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Venham L, Bengston D, Cipes M. Children's response to sequential dental visits. J Dent Res 1977;56:454–9. 10.1177/00220345770560050101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rajwar AS, Goswami M. Prevalence of dental fear and its causes using three measurement scales among children in New Delhi. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent 2017;35:128–33. 10.4103/JISPPD.JISPPD_135_16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sarapultseva M, Yarushina M, Kritsky I, et al. Prevalence of dental fear and anxiety among Russian children of different ages: the cross-sectional study. Eur J Dent 2020;14:621–5. 10.1055/s-0040-1714035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cuthbert MI, Melamed BG. A screening device: children at risk for dental fears and management problems. ASDC J Dent Child 1982;49:432–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arapostathis KN, Coolidge T, Emmanouil D, et al. Reliability and validity of the Greek version of the Children’s Fear Survey Schedule-Dental Subscale. Int J Paediatric Dent 2008;18:374–9. 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2007.00894.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lu J-xuan, Yu D-sheng, Luo W, et al. [Development of Chinese version of children's fear survey schedule-dental subscale]. Zhonghua Kou Qiang Yi Xue Za Zhi 2011;46:218–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boka V, Arapostathis K, Karagiannis V, et al. Dental fear and caries in 6-12 year old children in Greece. Determination of dental fear cut-off points. Eur J Paediatr Dent 2017;18:45. 10.23804/ejpd.2017.18.01.10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cianetti S, Lombardo G, Lupatelli E, et al. Dental fear/anxiety among children and adolescents. A systematic review. Eur J Paediatr Dent 2017;18:121–30. 10.23804/ejpd.2017.18.02.07 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu L, Gao X. Children's dental fear and anxiety: exploring family related factors. BMC Oral Health 2018;18:100. 10.1186/s12903-018-0553-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alshoraim MA, El-Housseiny AA, Farsi NM, et al. Effects of child characteristics and dental history on dental fear: cross-sectional study. BMC Oral Health 2018;18:33. 10.1186/s12903-018-0496-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Soares FC, Lima RA, Salvador DM, et al. Reciprocal longitudinal relationship between dental fear and oral health in schoolchildren. Int J Paediatr Dent 2020;30:286–92. 10.1111/ipd.12598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barreto KA, Dos Prazeres LDKT, Lima DSM, et al. Factors associated with dental anxiety in Brazilian children during the first transitional period of the mixed dentition. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent 2017;18:39–43. 10.1007/s40368-016-0264-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Soares FC, Lima RA, Santos CdaFBF, et al. Predictors of dental anxiety in Brazilian 5-7years old children. Compr Psychiatry 2016;67:46–53. 10.1016/j.comppsych.2016.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Milgrom P, Mancl L, King B, et al. Origins of childhood dental fear. Behav Res Ther 1995;33:313–9. 10.1016/0005-7967(94)00042-I [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yamada MKM, Tanabe Y, Sano T, et al. Cooperation during dental treatment: the children's fear survey schedule in Japanese children. Int J Paediatr Dent 2002;12:404–9. 10.1046/j.1365-263X.2002.00399.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frankl SN, Shiere F, Fogels HR. Should the parent remain with the child in the dental operatory? J Dent Child 1962;29:150–63. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baier K, Milgrom P, Russell S, et al. Children's fear and behavior in private pediatric dentistry practices. Pediatr Dent 2004;26:316–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Locker D, Thomson WM, Poulton R. Psychological disorder, conditioning experiences, and the onset of dental anxiety in early adulthood. J Dent Res 2001;80:1588–92. 10.1177/00220345010800062201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alsadat FA, El-Housseiny AA, Alamoudi NM, et al. Dental fear in primary school children and its relation to dental caries. Niger J Clin Pract 2018;21:1454–60. 10.4103/njcp.njcp_160_18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kakkar M, Wahi A, Thakkar R, et al. Prevalence of dental anxiety in 10-14 years old children and its implications. J Dent Anesth Pain Med 2016;16:199–202. 10.17245/jdapm.2016.16.3.199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ghaderi F, Fijan S, Hamedani S. How do children behave regarding their birth order in dental setting? J Dent 2015;16:329–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Majstorovic M, Morse DE, Do D, et al. Indicators of dental anxiety in children just prior to treatment. J Clin Pediatr Dent 2014;39:12–17. 10.17796/jcpd.39.1.u15306x3x465n201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bajrić E, Kobašlija S, Jurić H. Reliability and validity of dental Subscale of the children's fear survey schedule (CFSS-DS) in children in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Bosn J Basic Med Sci 2011;11:214–8. 10.17305/bjbms.2011.2549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Akbay Oba A, Dülgergil CT, Sönmez IS. Prevalence of dental anxiety in 7- to 11-year-old children and its relationship to dental caries. Med Princ Pract 2009;18:453–7. 10.1159/000235894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Venham LL, Gaulin-Kremer E, Munster E, et al. Interval rating scales for children's dental anxiety and uncooperative behavior. Pediatr Dent 1980;2:195–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Buchanan H, Niven N. Further evidence for the validity of the facial image scale. Int J Paediatr Dent 2003;13:368–9. 10.1046/j.1365-263X.2003.00488.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cademartori MG, Cara G, Pinto GDS, et al. Validity of the Brazilian version of the dental Subscale of children's fear survey schedule. Int J Paediatr Dent 2019;29:736–47. 10.1111/ipd.12543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.ten Berge M, Veerkamp JSJ, Hoogstraten J, et al. Childhood dental fear in the Netherlands: prevalence and normative data. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2002;30:101–7. 10.1034/j.1600-0528.2002.300203.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.El-Housseiny AA, Merdad LA, Alamoudi NM. Effect of child and parent characteristics on child dental fear ratings: analysis of short and full versions of the children’s fear survey schedule-dental subscale. Oral Health Dent Manage 2015;14:245–6. [Google Scholar]

- 37.MJY Y, Chen KJ, Gao SS. Dental fear and anxiety of kindergarten children in Hong Kong: a cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17:2827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Porritt J, Morgan A, Rodd H, et al. Development and evaluation of the children's experiences of dental anxiety measure. Int J Paediatr Dent 2018;28:140–51. 10.1111/ipd.12315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Paglia L, Gallus S, de Giorgio S, et al. Reliability and validity of the Italian versions of the Children's Fear Survey Schedule - Dental Subscale and the Modified Child Dental Anxiety Scale. Eur J Paediatr Dent 2017;18:305–12. 10.23804/ejpd.2017.18.04.08 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aminabadi NA, Sohrabi A, Erfanparast LK, et al. Can birth order affect temperament, anxiety and behavior in 5 to 7-year-old children in the dental setting? J Contemp Dent Pract 2011;12:225–31. 10.5005/jp-journals-10024-1039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Alvesalo I, Murtomaa H, Milgrom P, et al. The dental fear survey schedule: a study with Finnish children. Int J Paediatr Dent 1993;3:15–20. 10.1111/j.1365-263x.1993.tb00083.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nakai Y, Hirakawa T, Milgrom P, et al. The children's fear survey schedule–dental subscale in Japan. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2005;33:196–204. 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2005.00211.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Katsouda M, Tollili C, Coolidge T, et al. Gagging prevalence and its association with dental fear in 4-12-year-old children in a dental setting. Int J Paediatr Dent 2019;29:169–76. 10.1111/ipd.12445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Klingberg G, Berggren U, Norén JG. Dental fear in an urban Swedish child population: prevalence and concomitant factors. Community Dent Health 1994;11:208–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.