Abstract

Purpose/Objectives

Metastasis-directed therapy with stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) in the setting of oligometastatic disease is a rapidly evolving paradigm given ongoing improvements in systemic therapies and diagnostic modalities. However, SBRT to targets in the abdomen and pelvis is historically associated with concerns about toxicity. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the safety and efficacy of SBRT to the abdomen and pelvis for women with oligometastases from primary gynecological tumors.

Materials/Methods

From our IRB-approved registry, all patients who were treated with SBRT between 2014 and 2020 were identified. Oligometastatic disease was defined as 1 to 5 discrete foci of clinical metastasis radiographically diagnosed by positron emission tomography (PET) and/or computerized tomography (CT) imaging. The primary endpoint was local control at 12 months. Local and distant control rates were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Time intervals for development of local progression and distant progression were calculated based on follow up visits with re-staging imaging. Acute and late toxicity outcomes were determined based on Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 5.0.

Results

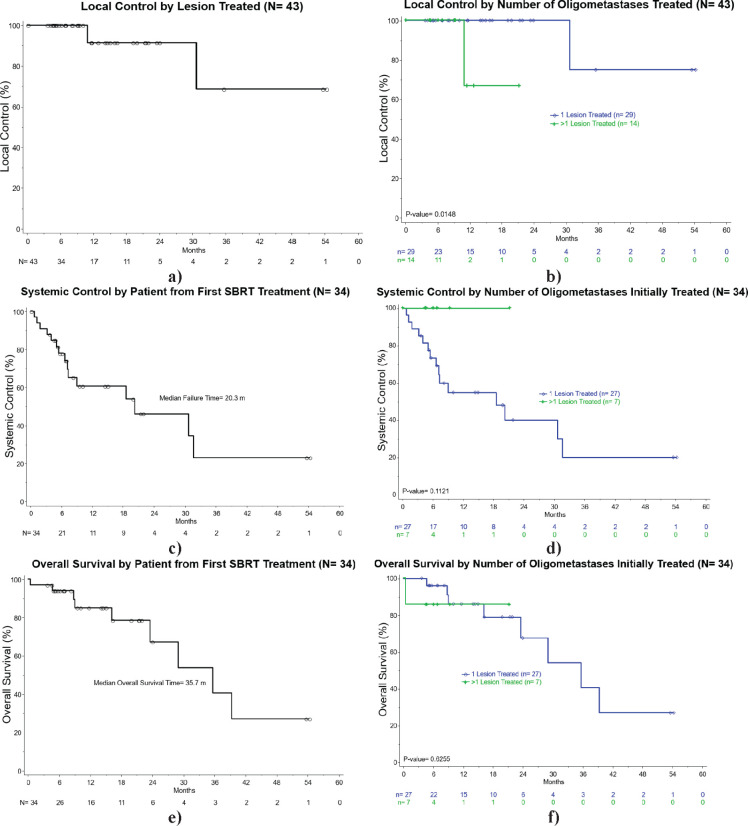

We identified 34 women with 43 treated lesions. Median age was 68 years (range 32-82), and median follow up time was 12 months (range 0.2-54.0). Most common primary tumor sites were ovarian (n=12), uterine (n=11), and cervical (n=7). Median number of previous lines of systemic therapy agents at time of SBRT was 2 (range 0-10). Overall, SBRT was delivered to 1 focus of oligometastasis in 29 cases, 2 foci in 2 cases, 3 foci in 2 cases, and 4 foci in 1 case. All patients were treated comprehensively with SBRT to all sites of oligometastasis. Median prescription dose was 24 Gy (range 18-54 Gy) in 3 fractions (range 3-6) to a median prescription isodose line of 83.5% (range 52-95). Local control by lesion at 12 and 24 months was 92.5% for both time points. Local failure was observed in three treated sites among two patients, two of which were at 11 months in one patient, and the other at 30 months. Systemic control rate was 60.2% at 12 months. Overall survival at 12 and 24 months was 85% and 70.2%, respectively. Acute grade 2 toxicities included nausea (n=3), and there were no grade > 3 acute toxicities. Late grade 1 toxicities included diarrhea (n=1) and fatigue (n=1), and there were no grade > 2 toxicities.

Conclusion

SBRT to oligometastatic gynecologic malignancies in the abdomen and pelvis is feasible with encouraging preliminary safety and local control outcomes. This approach is associated with excellent local control and low rates of toxicity during our follow-up interval. Further investigations into technique, dose-escalation and utilization are warranted.

Keywords: Oligometastasis, gynecological malignancies, radiotherapy, stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT)

INTRODUCTION

There is a growing body of evidence describing metastatic disease as a continuum ranging from a single oligometastatic focus to widely-metastatic disease1,2. Oligometastasis describes a clinical state in which a patient has a limited number of distant metastases, typically between 1 to 5 lesions, which are amenable to local therapies3,4. With recent advances in efficacy of systemic therapies and sensitivity of diagnostic modalities, metastasis-directed therapy for oligometastatic cancer has become a rapidly evolving landscape. While systemic agents are the mainstay of therapy for metastatic cancer, several recent prospective studies have reported improved progression-free survival (PFS), overall survival (OS), and androgen deprivation treatment-free survival associated with metastasis-directed therapy using stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) for patients with oligometastatic cancer5-11. Metastasis-directed therapy for oligometastases has demonstrated utility for patients on effective systemic therapy demonstrating phenomena of oligoprogression—control of most metastases with progression in a limited number—or oligopersistence—response to systemic therapy in most lesions with stable or only partial response in a limited number. Metastasis-directed therapy for these patients can prolong their time on efficacious systemic therapy by theoretically ablating resistant clones before distant seeding can occur. While outcomes have been reported for patients with prostate, breast, non-small cell lung, and colorectal cancers with oligometastases to bone, lung, and liver, there is a relative paucity of prospective data specific to safety and efficacy of SBRT for abdominopelvic oligometastases from gynecological primary tumors12-16.

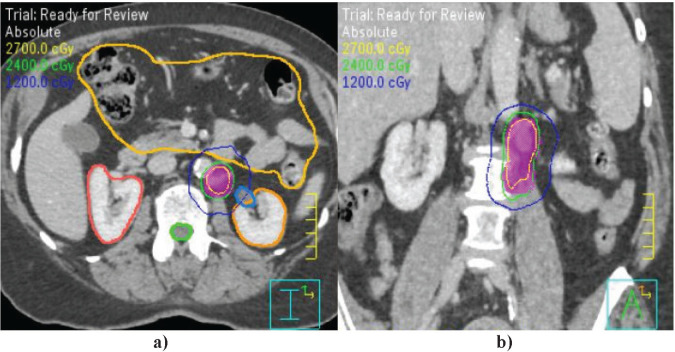

SBRT to targets within the abdomen and pelvis presents challenges due to a combination of factors including inter- and intra-fraction motion management, relative sensitivity of hollow viscous abdominal organs to high fractional radiotherapy doses, a patient population which is often heavily pre-treated with chemotherapy and/or anti-angiogenic agents, and limitations in accessibility of lesions for tissue biopsy17-19. Moreover, serial organs at risk (e.g. small intestine and ureter) and retroperitoneal lymph node targets are medial to the psoas muscles. Hence, the psoas serves as a cautionary landmark for SBRT planning. As such, with the exceptions of liver and adrenal metastases, data describing SBRT outcomes for metastasis-directed therapy to oligometastases in the abdomen are relatively limited. The purpose of this study was to describe the safety and efficacy of SBRT for women with oligometastatic gynecological malignancies in the abdomen and pelvis. The primary endpoint of this study was local control rate at 12 months.

Materials/Methods

Cohort

We queried an institutional review board-approved institutional database of patients with oligometastatic gynecological malignancy treated with SBRT in the abdomen and/or pelvis between 2014 and 2020. For the purposes of this study, oligometastatic disease was defined as 1 to 5 discrete foci of new or progressive radiological metastasis seen on PET and/or CT imaging. Prior or concurrent systemic therapy was not an exclusion criteria. Patients with isolated liver metastases were excluded given the relatively large body of evidence demonstrating safety and efficacy of liver SBRT. Patients undergoing SBRT boost to definitive surgical or radiotherapy regimens were excluded.

Treatment

All patients underwent CT simulation imaging in supine position with arms across chest or above head depending on patient comfort and target location. IV contrast was utilized for all patients without contraindications, and oral contrast was given at the discretion of the treating physician. All patients underwent motion management with utilization of a vacuum mattress. Additional motion management devices for select patients included activated breathing control, abdominal compression belt, and rectal balloon. Dynamic 4-dimensional CT imaging was utilized at the time of simulation for all patients with abdominal tumors. The target volume was delineated on the simulation CT images, with fusion of PET/CT and/or MRI images into treatment planning software when available, to define the gross tumor volume. For patients undergoing 4-dimensional CT imaging, the maximum excursive motion of the tumor during the respiratory cycle was delineated in three dimensions to create an internal target volume. For patients able to perform breath-hold techniques, activated breathing control technique was utilized which involves training the patient to use a modified spirometer with a valve that closes when the patient achieves the adequate degree of inspiration specified at time of simulation, at which point the delivery of radiation to the target commences while a timer counts down until the linear accelerator pauses radiation delivery, the spirometer valve opens, and the patient can exhale. An expansion of 2-5 mm was applied to the internal target volume to create a planning target volume. Organs at risk were delineated on the free-breathing simulation CT images. In the case of targets medial to the psoas major muscles that were adjacent to the ureter, delayed intravenous contrast images were acquired to allow for enhanced visualization of the ureters.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of: a) local control by lesion treated; and b) local control by number of oligometastatic sites treated; c) systemic control by patient from completion of SBRT; and d) systemic control by number of oligometastatic sites treated; e) overall survival by patient from completion of SBRT; and f) overall survival by number of oligometastatic sites treated.

Figure 2.

Example SBRT plan for treatment of oligometastatic endometrial cancer to the left para-aortic region. a) Axial post-contrast CT images demonstrating PTV (fuchsia shaded), 100% isodose line (thin green), bowel bag organ at risk (marigold), right kidney (dark orange), left kidney (light orange), and spinal cord (thick green). b) Coronal CT images demonstrating target location medial to psoas muscles.

SBRT was delivered every other day using the flattening-filter free mode on the Varian Edge linear accelerator system with daily cone-beam CT utilized for image guidance. The technique for SBRT delivery was volumetric modulated arc therapy for all but one patient who received step-and-shoot Intensity-modulated radiotherapy.

Endpoints

The primary endpoint was local control in the treated lesion(s) at 12 months. Additionally, acute and late toxicity outcomes were determined using the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 5.0. Toxicity outcomes were also evaluated based on tumor location with respect to the psoas muscles given the higher concentration of sensitive organs at risk medial to the psoas. Additional endpoints included systemic control and overall survival for all patients and for patients with multiple versus single lesions treated. Time intervals for development of local- and distant-progression after completion of SBRT were calculated based on follow up office visits with follow up imaging including, but not limited to, PET/CT, CT with or without intravenous contrast, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Follow up imaging was obtained every 3-6 months. Systemic control was defined by the gynecologic oncologist as absence of progression based on imaging, laboratory results, and clinical exam.

Statistics

The endpoints of local control, systemic control, and overall survival were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method with death as a competing event. Patients who died without local failure were censored at the date of their last assessment before death. Toxicity outcomes in organs at risk by anatomical relationship to the psoas muscles were calculated using Fisher’s exact test. Differences in radiotherapy dose with respect to anatomical relationship were compared using Mann-Whitney tests.

RESULTS

We identified 34 women with a total of 43 oligometastatic lesions in the abdomen and/or pelvis treated with SBRT between 2014 and 2020. Please refer to Table 1 for demographic patient and tumor characteristics.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| Characteristics | Patients, n (%) | Lesions, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 34 | |

| Total lesions treated | 43 | |

| Median age at treatment (range), yr | 68 (32-82) | |

| Target location | ||

| Abdominal lymph node, medial to psoas | 14 (33) | |

| Abdominal soft tissue, medial to psoas | 3 (7) | |

| Abdominal lymph node, lateral to psoas | 4 (9) | |

| Abdominal soft tissue, lateral to psoas | 2 (5) | |

| Pelvic lymph node | 8 (18) | |

| Pelvic soft tissue | 12 (28) | |

| Number of oligometastases treated | ||

| 1 | 27 (79) | 29 (67) |

| 2 | 3 (9) | 8 (19) |

| 3 | 2 (6) | 4 (9) |

| 4 | 2 (6) | 2 (5) |

| Median prior courses of systemic therapy (range) | 2 (0-10) | |

| Prior RT to same site | ||

| No | 21 (62) | 23 (54) |

| Yes | 13 (38) | 20 (46) |

| Prior biologic agents | ||

| Bevacizumab | 15 (44) | 22 (51) |

| None | 17 (50) | 17 (40) |

| Bevacizumab and pembrolizumab | 1 (3) | 3 (7) |

| Pembrolizumab | 1 (3) | 3 (7) |

| Primary tumor site | ||

| Ovarian | 12 (35) | 18 (42) |

| Uterine | 11 (32) | 13 (30) |

| Cervix | 7 (21) | 7 (16) |

| Fallopian tube | 2 (6) | 3 (7) |

| Primary peritoneal | 2 (6) | 2 (5) |

| History of prior RT to same site | ||

| No | 21 (62) | |

| Yes | 13 (38) | |

| Number of synchronous lesions treated | n (%) | |

| 1 | 27 (79) | |

| 2 | 3 (9) | |

| 3 | 2 (6) | |

| 4 | 2 (6) | |

| SBRT treatment type | n (%) | |

| SBRT coplanar VMAT | 41 (96) | |

| SBRT coplanar IMRT | 1 (2) | |

| SBRT step-and-shoot | 1 (2) |

SBRT: stereotactic body radiotherapy, VMAT: volumetric modulated arc therapy, IMRT: intensity modulated radiotherapy

All patients underwent SBRT to all known sites of oligometastasis. Median number of oligometastatic sites was 1 (range 1-4), and median number of previous chemotherapy courses was 2 (range 0-10). Median follow up time from completion of first SBRT treatment to most recent clinical follow up visit for the entire cohort was 12 months (range 0.2-54.0 months). Median follow up time by lesion site for patients with metachronous distant oligometastasis also treated with SBRT was 11 months. Median SBRT prescription dose was 24 Gy (range 18-54) delivered in a median of 3 fractions (range 3-6), while mean gross tumor volume dose was 28.7 Gy (range of 23.9-55.2). Local control was observed in 94% of patients with two experiencing local failure. Out of 43 treated lesions, local control was observed in 92.5%. Two of three local failures were synchronously observed in the same patient at 11 months, and the third local failure was in another patient who failed locally and distantly at 30 months after SBRT. Systemic failure was observed in 44% of all patients at the time of last follow up, and median time to first relapse was 7.2 months (range 1-32). Systemic control for the entire cohort 12 months after completing first SBRT treatment was 60.2% (95% CI: 41.4-79.0%). Of the patients with one oligometastatic focus treated with SBRT, rates of systemic control were 53.8% (95% CI: 33.5-74.2%) at 1 year post- SBRT and 38.4% (95% CI: 15.3-61.6%) at 2 years. Overall survival for the entire cohort at 1 year was 85.0% (95% CI: 71.3-98.8%) and at 2 years was 70.2% (95% CI: 47.9-92.4%).

Median prescription dose for targets medial to the psoas muscles was 25 Gy (range 18-54 Gy) in a median of 3 fractions (range 3-6). Median prescription dose for targets lateral to the psoas muscles was 24 Gy (range 24-45) in a median of 3 fractions (range 3-5). Maximum point doses to the ureter, small bowel and large bowel were considered in determining the prescribed dose to maintain the safety of treatment. Mean maximum doses were 27.3 Gy to the ureter, 24.9 Gy to the small bowel, and 25.9 Gy to the large bowel. Additional treatment and dosimetry characteristics are available for reference in Table 2.

Table 2.

Treatment and Prescription Characteristics

| Treatment and Dosimetry | Median (range) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Median SBRT prescription dose (range), Gy | 24 (18-54) Gy/3 (3-6) fx | 0.63 |

| Lateral to psoas | 24 (24-45) | |

| Medial to psoas | 25 (18-54) | |

| Mean GTV dose, Gy | 28.7 (23.9-55.2) | 0.059 |

| Lateral to psoas | 28.6 (23.9-51.5) | |

| Medial to psoas | 29.2 (23.9-55.2) | |

| Mean prescription IDL, % | 84.5 (51.7-95) | 0.68 |

| Lateral to psoas | 84.5 (51.7-95) | |

| Medial to psoas | 83.4 (51.7-94) | |

| Small bowel max. point dose, Gy | 26.3 (6.1-40.8) | 0.38 |

| Lateral to psoas, Gy | 25.3 | |

| Medial to psoas, Gy | 25.4 | |

| Large bowel max. point dose | 25.9 (0.6-40.8) | 0.44 |

| Lateral to psoas, Gy | 26.5 | |

| Medial to psoas, Gy | 25.8 | |

| Ureter max. point dose | 26.8 (2.3-46.6) | 0.73 |

| Lateral to psoas, Gy | 26.8 | |

| Medial to psoas, Gy | 27.1 |

IDL: isodose line, SBRT: stereotactic body radiotherapy, GTV: gross tumor volume, Gy: gray, Fx: fraction

Few acute toxicity events were reported with 9% of patients experiencing grade 2 nausea, and no toxicities grade 3 or higher. One patient presented with a malignant rectovaginal fistula from a vaginal cuff recurrence prior to SBRT which was persistent after therapy to the involved lesion. Late toxicity was rare with no grade 2 or higher late toxicities. There were 24 patients in the cohort with lesions located medial to the psoas muscles. There were no significant differences in SBRT dose and fractionation prescription between patients with SBRT targets medial or lateral to psoas muscles. Table 3 demonstrates no significant difference in rates of acute and late toxicity between patients who had medial or lateral tumors.

Table 3.

Toxicity results

| Toxicity | n (%) | P-value |

| Acute toxicity | >0.99 | |

| Acute toxicity, lateral tumors | ||

| Grade 1 fatigue, grade 1 diarrhea | 1 (6.3) | |

| Grade 1 nausea | 2 (12.5) | |

| Acute toxicity, medial tumors | ||

| Grade 1 dysuria | 1 (3.7) | |

| Grade 2 nausea | 1 (3.7) | |

| Grade 2 nausea, grade 1 abdominal pain | 1 (3.7) | |

| Grade 2 nausea, grade 1 diarrhea and fatigue | 1 (3.7) | |

| Grade 1 abdominal pain | 1 (3.7) | |

| Persistence of pre-SBRT fistula | 1 (3.7) | |

| Late toxicity (> 6 months post-SBRT) | 0.14 | |

| Late toxicity, lateral tumors | ||

| Grade 1 diarrhea | 3 (19) | |

| Late toxicity, medial tumors | ||

| Grade 1 fatigue | 1 (3.7) |

p-values calculated using Fisher’s exact test for toxicity between medial and lateral locations

DISCUSSION

Our study found that women undergoing abdominal or pelvic SBRT for oligometastatic gynecological cancer experienced excellent local control with favorably low toxicity rates. Further, over half of patients continued to experience freedom from systemic progression a year after completing SBRT.

There is a growing body of evidence supporting SBRT for oligometastatic or oligoprogressive gynecologic malignancies12-16. However, until recently, women with gynecologic cancer metastases in the abdomen have been limited in local therapy options to invasive surgery or palliative conventionally-fractionated radiotherapy. Our study suggests that SBRT in the abdomen is safe and well-tolerated and should be considered as a means of local control for women with good response to prior systemic therapy.

Safety of abdominal SBRT for various histologies and locations has been demonstrated previously, although there are limitations to these studies. In a retrospective series from the University of Colorado, no grade 4 or 5 toxicities were observed among 36 patients receiving SBRT for metastatic renal cell carcinoma, of whom 6 had lesions treated in the abdomen20. The most common SBRT fractionation utilized in that study was 50 Gy in 5 fractions. However, the small number of patients on this study with abdominal targets as well as the radiobiologic differences between renal cell carcinoma and gynecologic malignancies limit extrapolation of these results to the oligometastatic gynecologic patient population. Robotic SBRT using the CyberKnife system has also been shown to have favorable toxicity outcomes for women with recurrent metastatic gynecologic cancers. The authors included 50 women in the analysis, 42% of whom had tumors in the para-aortic lymph nodes or upper abdomen 12. The authors reported low rates of grade 3 and 4 toxicity with favorable clinical benefit rates based on SBRT target responses measured by the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors criteria. Of note, the authors report gold fiducial placement was utilized for target localization in 88% of patients while bony anatomy was used for the remainder. By contrast, one benefit of our experience in applying abdominal SBRT to clinical practice is the use of standard linear accelerators rather than robotic CyberKnife systems. Standard linear accelerators are generally more accessible and provide faster treatment delivery than robotic systems, thereby reducing risk of intrafraction motion. Further, daily image guidance with kilovoltage cone-beam CT produced reproducible results in our study without the need for invasive gold fiducial placement.

The psoas major muscles theoretically represent an anatomical landmark in the lower abdomen and upper pelvis to be carefully considered by radiation oncologists, specifically with the space medial to the muscle bellies containing significant portions of the ureters and small bowel. Hollow viscous organs and luminal structures like the small bowel and ureter, respectively, are considered to be serial organs at risk of late toxicity with high dose per fraction21. Despite a theoretical concern for an increased risk of acute and late toxicity for medial SBRT targets, our study did not demonstrate any observed difference in toxicity based on anatomical location as seen in Table 3. In particular, small bowel and ureteral toxicity was not observed for women whose tumors were medial to the psoas muscles. Median values for dosimetric maximum point doses among patients are listed in Table 2, but the authors generally chose dose and fractionation based on limiting volumetric and maximum point dose constraints to these organs at risk. Specifically, maximum point dose constraint goals were generally less than 40 Gy for ureter, 28.5 Gy for small bowel, and 45 Gy for colon. Therefore, provided that SBRT plans achieve constraints to organs at risk, SBRT should be considered a safe option for a patient presenting with a medially located target lesion.

While safety and efficacy results are encouraging, this study has several limitations beyond those common to retrospective analyses. First, patients on this study represented a heterogeneous cohort with regard to primary tumor histology. Future study with larger numbers of patients is needed to achieve adequate power. Second, there was variability in SBRT prescription doses and fractionation schedules, likely because of the variability of target locations and OAR constraints needed from patient to patient. Further, the low number of local recurrence events limit the ability to examine the relationship between biologically effective dose (BED) and tumor control. For example, the two most common prescriptions have vastly different BED values: 24 Gy/3 fx and 40 Gy/5 fx have BED values of 43.2 Gy and 72 Gy, respectively (assuming α/β = 10). Further study is necessary to evaluate histology-specific BED thresholds for local control.

CONCLUSION

Stereotactic body radiotherapy for oligometastatic gynecologic cancers in the abdomen and pelvis is a safe and feasible treatment option. Abdominal SBRT is associated with excellent local control and minimal toxicity. Women with oligometastatic gynecologic cancer in the abdomen and pelvis should be considered for SBRT rather than simply changing systemic therapy agents. SBRT can allow for continuation of effective systemic therapy in oligoprogressive patients, and may delay distant failure in some patients. Further prospective studies are warranted to understand patient selection and therapeutic optimization.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Ethical statement

The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Authors’ disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Author contributions

Conception and design: Timothy D. Smile, Sheen S. Cherian

Administrative support: Timothy D. Smile, Sheen S. Cherian

Provision of study materials or patients: Sudha R. Amarnath, Kevin L. Stephans, Neil M. Woody, Ehsan H. Balagamwala, Mariam M. AlHilli, Chad M. Michener, Haider Mahdi, Robert L. DeBernardo, Peter G. Rose, Sheen S. Cherian

Collection and assembly of data: Timothy D. Smile

Data analysis and interpretation: Timothy D. Smile, Chandana A. Reddy, Ian W. Winter

Manuscript writing: Timothy D. Smile, George Qiao-Guan, Sheen S. Cherian

Final approval of manuscript: Timothy D. Smile, Chandana A. Reddy, George Qiao-Guan, Ian W. Winter, Kevin L. Stephans, Neil M. Woody, Ehsan H. Balagamwala, Anthony Magnelli, Mariam M. AlHilli, Chad M. Michener, Haider Mahdi, Robert L. DeBernardo, Peter G. Rose, Sheen S. Cherian

REFERENCES

- 1.Hellman S, Weichselbaum RR. Oligometastases. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 1995;13(1):8-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Milano MT, Biswas T, Simone CB. (2nd), Lo SS. Oligometastases: history of a hypothesis. Annals of palliative medicine. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guckenberger M, Lievens Y, Bouma AB, Collette L, Dekker A, deSouza NM, Dingemans AC, Fournier B, Hurkmans C, Lecouvet FE, Meattini I, Méndez Romero A, Ricardi U, Russell NS, Schanne DH, Scorsetti M, Tombal B, Verellen D, Verfaillie C, Ost P. Characterisation and classification of oligometastatic disease: a European Society for Radiotherapy and Oncology and European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer consensus recommendation. The Lancet Oncology. 2020;21(1):e18-e28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lievens Y, Guckenberger M, Gomez D, Hoyer M, Iyengar P, Kindts I, Méndez Romero A, Nevens D, Palma D, Park C, Ricardi U, Scorsetti M, Yu J, Woodward WA. Defining oligometastatic disease from a radiation oncology perspective: An ESTRO-ASTRO consensus document. Radiotherapy and oncology : journal of the European Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology. 2020;148:157-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Palma DA, Olson R, Harrow S, Correa RJM, Schneiders F, Haasbeek CJA, Rodrigues GB, Lock M, Yaremko BP, Bauman GS, Ahmad B, Schellenberg D, Liu M, Gaede S, Laba J, Mulroy L, Senthi S, Louie AV, Swaminath A, Chalmers A, Warner A, Slotman BJ, de Gruijl TD, Allan A, Senan S. Stereotactic ablative radiotherapy for the comprehensive treatment of 4-10 oligometastatic tumors (SABR-COMET-10): study protocol for a randomized phase III trial. BMC cancer. 2019;19(1):816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iyengar P, Wardak Z, Gerber DE, Tumati V, Ahn C, Hughes RS, Dowell JE, Cheedella N, Nedzi L, Westover KD, Pulipparacharuvil S, Choy H, Timmerman RD. Consolidative Radiotherapy for Limited Metastatic Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: A Phase 2 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA oncology. 2018;4(1):e173501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ost P, Reynders D, Decaestecker K, Fonteyne V, Lumen N, De Bruycker A, Lambert B, Delrue L, Bultijnck R, Claeys T, Goetghebeur E, Villeirs G, De Man K, Ameye F, Billiet I, Joniau S, Vanhaverbeke F, De Meerleer G. Surveillance or Metastasis-Directed Therapy for Oligometastatic Prostate Cancer Recurrence: A Prospective, Randomized, Multicenter Phase II Trial. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2018;36(5):446-453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Phillips R, Shi WY, Deek M, Radwan N, Lim SJ, Antonarakis ES, Rowe SP, Ross AE, Gorin MA, Deville C, Greco SC, Wang H, Denmeade SR, Paller CJ, Dipasquale S, DeWeese TL, Song DY, Wang H, Carducci MA, Pienta KJ, Pomper MG, Dicker AP, Eisenberger MA, Alizadeh AA, Diehn M, Tran PT. Outcomes of Observation vs Stereotactic Ablative Radiation for Oligometastatic Prostate Cancer: The ORIOLE Phase 2 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA oncology. 2020;6(5):650-659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Trippa F CM, Draghini L, Anselmo P, Arcidiacono F, Maanzano E. Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy for Lymph Node Relapse in Ovarian Cancer. Clin Oncol. 2016;1:1038. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kowalchuk RO, Waters MR, Richardson KM, Spencer K, Larner JM, Irvin WP, Kersh CR. Stereotactic body radiation therapy in the treatment of ovarian cancer. Radiation oncology (London, England) 2020;15(1):108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iftode C, DʼAgostino GR, Tozzi A, Comito T, Franzese C, De Rose F, Franceschini D, Di Brina L, Tomatis S, Scorsetti M. Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy in Oligometastatic Ovarian Cancer: A Promising Therapeutic Approach. International journal of gynecological cancer : official journal of the International Gynecological Cancer Society. 2018;28(8):1507-1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kunos CA, Brindle J, Waggoner S, Zanotti K, Resnick K, Fusco N, Adams R, Debernardo R. Phase II Clinical Trial of Robotic Stereotactic Body Radiosurgery for Metastatic Gynecologic Malignancies. Frontiers in oncology. 2012;2:181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Macchia G, Deodato F, Cilla S, Torre G, Corrado G, Legge F, Gambacorta MA, Tagliaferri L, Mignogna S, Scambia G, Valentini V, Morganti AG, Ferrandina G. Volumetric intensity modulated arc therapy for stereotactic body radiosurgery in oligometastatic breast and gynecological cancers: feasibility and clinical results. Oncology reports. 2014;32(5):2237-2243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lazzari R, Ronchi S, Gandini S, Surgo A, Volpe S, Piperno G, Comi S, Pansini F, Fodor C, Orecchia R, Tomao F, Parma G, Colombo N, Jereczek-Fossa BA. Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy for Oligometastatic Ovarian Cancer: A Step Toward a Drug Holiday. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 2018;101(3):650-660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laliscia C, Fabrini MG, Delishaj D, Morganti R, Greco C, Cantarella M, Tana R, Paiar F, Gadducci A. Clinical Outcomes of Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy in Oligometastatic Gynecological Cancer. International journal of gynecological cancer : official journal of the International Gynecological Cancer Society. 2017;27(2):396-402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Macchia G, Lazzari R, Colombo N, Laliscia C, Capelli G, D’Agostino GR, Deodato F, Maranzano E, Ippolito E, Ronchi S, Paiar F, Scorsetti M, Cilla S, Ingargiola R, Huscher A, Cerrotta AM, Fodor A, Vicenzi L, Russo D, Borghesi S, Perrucci E, Pignata S, Aristei C, Morganti AG, Scambia G, Valentini V, Jereczek-Fossa BA, Ferrandina G. A Large, Multicenter, Retrospective Study on Efficacy and Safety of Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy (SBRT) in Oligometastatic Ovarian Cancer (MITO RT1 Study): A Collaboration of MITO, AIRO GYN, and MaNGO Groups. The oncologist. 2020;25(2):e311-e320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pollom EL, Deng L, Pai RK, Brown JM, Giaccia A, Loo BW, Shultz DB, Le QT, Koong AC, Chang DT. Gastrointestinal Toxicities With Combined Antiangiogenic and Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 2015;92(3):568-576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barney BM, Markovic SN, Laack NN, Miller RC, Sarkaria JN, Macdonald OK, Bauer HJ, Olivier KR. Increased bowel toxicity in patients treated with a vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitor (VEGFI) after stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT). International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 2013;87(1):73-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Almaghrabi MY, Supiot S, Paris F, Mahé MA, Rio E. Stereotactic body radiation therapy for abdominal oligometastases: a biological and clinical review. Radiation oncology (London, England). 2012;7:126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Altoos B, Amini A, Yacoub M, Bourlon MT, Kessler EE, Flaig TW, Fisher CM, Kavanagh BD, Lam ET, Karam SD. Local Control Rates of Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma (RCC) to Thoracic, Abdominal, and Soft Tissue Lesions Using Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy (SBRT). Radiation oncology (London, England). 2015;10:218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hall EG AJ. Radiobiology for the Radiologist. 8th ed.Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2018. [Google Scholar]