Abstract

Background:

Emerging data from a single center study suggests that a 30% relative reduction in liver fat content as assessed by magnetic resonance imaging-proton density fat fraction (MRI-PDFF) from baseline may be associated with histologic improvement in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). There are limited multicenter data comparing an active drug versus placebo on the association between the quantity of liver fat reduction assessed by MRI-PDFF and histologic response in NASH.

Aim:

To examine the association between 30% relative reduction in MRI-PDFF and histologic response in obeticholic acid versus placebo-treated patients in the FLINT trial.

Methods:

This is a secondary analysis of the FLINT trial including 78 patients with MRI-PDFF measured before and after treatment along with paired liver histology assessment. Histologic response was defined as a two-point improvement in NAFLD Activity Score without worsening of fibrosis.

Results:

Obeticholic acid at 25 mg orally once daily was better than placebo in improving MRI-PDFF by an absolute difference of −3.4% (95% CI, −6.5 to −0.2%, p-value=0.04), and relative difference of −17% (95% CI, −34 to 0%, p-value=0.05). The optimal cut-point for relative decline in MRI-PDFF for histologic response was 30%. (using Youden’s index). The rate of histologic response in those who achieved < 30% decline in MRI-PDFF versus those who achieved a ≥ 30% decline in MRI-PDFF (MRI-PDFF responders) relative to baseline was 19% versus 50%, respectively. Compared to MRI-PDFF non-responders, MRI-PDFF responders demonstrated both a statistically and clinically significant higher odds 4.86 (95% CI, 1.4–12.8, p-value <0.009) of histologic response including significant improvements in both steatosis and ballooning.

Conclusions:

Obeticholic acid was better than placebo in reducing liver fat. This multicenter trial provides novel data regarding the association between 30% decline in MRI-PDFF relative to baseline and histologic response in NASH.

Keywords: MRI-PDFF, NAFLD, fibrosis, steatosis

INTRODUCTION

Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) is a chronic and progressive form of liver disease that can lead to cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma and increased risk of both liver as well as all-cause mortality1, 2. It is commonly associated with obesity, metabolic syndrome and diabetes3–5. Although several therapies have shown promise in early phase trials there are currently no approved therapies for the treatment of NASH6–8.

Liver histologic assessment is used for the assessment of treatment response in NASH9. Liver biopsy is an invasive procedure and may be associated with pain, infection, and risk of bleeding requiring blood transfusion; in extremely rare instances, it may cause death10. There is a major unmet need in the field to develop non-invasive biomarkers to assess histologic response in NASH without requiring a liver biopsy examination11–13. This need is driving intense research efforts to develop non-invasive modalities for this purpose.

The most commonly used metric for assessing treatment response in NASH trials is the NAFLD Activity Score (NAS). A summary score (range 0–8) based on steatosis (range 0–3), lobular inflammation (0–3) and ballooning (0–2), the NAS was developed to assess treatment response in the setting of a NASH trial9. Recent studies have shown that magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) derived biomarker termed proton-density-fat-fraction (PDFF) provides an accurate, non-invasive, reproducible, quantitative, and precise estimation of liver fat content14–16.

Early phase single-center NASH trials have utilized MRI-PDFF as a primary outcome to assess treatment response 16–19. Preliminary data from these trials have suggested an association between a 30% decline in MRI-PDFF from baseline and a two-point NAS improvement 20. However, there are limited data from multicenter trials to validate this association21. To fill this gap in knowledge, we assessed the association between decline in MRI-PDFF and improvement in NAS in the Farnesoid X Receptor Ligand Obeticholic Acid in NASH (FLINT) trial13 where we had obtained contemporaneous MRI-PDFF and liver biopsy before and after treatment in patients randomized to either obeticholic acid or placebo.

METHODS

Participants and study design:

This is a secondary analysis of the FLINT trial: a multicenter, randomized, double-masked, placebo-controlled, phase 2b clinical trial in which non-cirrhotic patients with biopsy-proven NASH were randomized to either obeticholic acid 25 mg orally daily or placebo for 72 weeks13. The FLINT trial included 283 patients who were recruited at eight sites of the Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Clinical Research Network (NASH CRN), a consortium funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK). All participants provided written informed consent and the studies were approved by the institutional review boards of the participating centers.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria:

Detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria for the trial are published elsewhere13. Briefly, patients with biopsy-proven NASH and a NAS of at least 4 or higher were stratified by presence of diabetes and then randomized to either obeticholic acid or placebo. Patients with cirrhosis were excluded from the trial.

MRI assessment:

Liver fat quantification was performed as a FLINT substudy using MRI-PDFF because of its demonstrated feasibility, accuracy, and precision in estimating liver fat longitudinally in the setting of a clinical trial 16, 17, 22. MRI-PDFF was offered before and after treatment but was not a mandatory study procedure.

The MRI protocol for the FLINT trial has been published elsewhere14. Liver MRI was obtained in 7 out of the 8 sites. Briefly, the inclusion criteria for the MRI-PDFF assessment were that the subject was enrolled in the FLINT trial, and that the subject was willing and able to complete two MRI exams (a baseline exam prior to randomization and an end of treatment MRI exam [both within 90 days of liver biopsy exam]). Exclusion criteria for the MRI sub-study were contraindications to MRI, extreme claustrophobia, pregnancy, weight or girth exceeding MRI scanner capability, or inability to complete the required study procedures in the opinion of the study investigators)14.

The NASH CRN Radiology Reading Center (RRC) in close collaboration with the NASH CRN Data Coordinating Center (DCC) managed the MRI portion of the FLINT trial14. All sites underwent a MRI sub-study qualification process and were certified by the RRC prior to initiating MRI exams on patients enrolled in the FLINT trial14. This rigor was felt to be important as this was one of the first multicenter clinical trials using MRI-PDFF in a NASH trial.

MRI-PDFF analysis was performed at the RRC based at UCSD by experienced central readers under the supervision of experienced radiology investigators. The readers placed regions of interest in each of the nine Couinaud segments co-localized before and after treatment. The average PDFF across the nine segments was recorded at each time point. The readers and radiology investigators were masked to liver biopsy and clinical data as well as treatment group assignment.

Histologic assessment:

The NASH CRN Histologic scoring system was used to assess liver histology before and after treatment by an experienced central pathology committee assessment9. The pathologists were masked to the sequence of liver biopsies as well as to clinical and imaging data and treatment group assignment.

Definition of Histologic response:

Primary outcome of the FLINT trial was a 2-point improvement in NAS (a summary score [range 0–8] including steatosis [ranging 0–3], lobular inflammation [0–3], and ballooning [0–2]) without worsening of fibrosis9, 13. This secondary analysis used the protocol defined definition to assess histologic response.

Statistical data analysis plan:

This analysis of the FLINT trial including 78 patients who underwent MRI-PDFF before and after treatment along with paired liver histology assessment. Association between quantitative change in MRI-PDFF and histologic response was assessed using robust linear and logistic regression models and their 95% confidence limits. Primary outcome was the primary endpoint of the FLINT Trial Histologic response, which was defined as a two-point improvement in NAFLD Activity Score without any worsening of fibrosis.

MRI-PDFF was not available at all sites. Therefore, a subset of patients underwent paired assessment. However, there was complete allocation concealment to the treatment group assignment, and the radiologists were masked to all clinical and histologic data.

RESULTS:

Baseline characteristics:

Seventy-eight patients (40 patients randomized to receive obeticholic acid and 38 patients randomized to placebo) with paired pre-treatment and post-treatment liver histology and MRI-PDFF data were included in this analysis. The baseline characteristics of the sub-study population are shown in Table 1. The two treatment groups were well matched for most clinical, biochemical and histologic features. The mean ±SD of the MRI-PDFF at was 18% ±9% in the obeticholic acid group and 20% ±10% in the placebo group

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics by treatment group

| Obeticholic Acid (n=40) | Placebo (n=38) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age – yr | 53 (9) | 52 (13) | 0.71 |

| Male sex – no. (%) | 15 (38%) | 14 (37%) | 0.95 |

| White race – no. (%) | 35 (88%) | 32 (84%) | 0.68 |

| Hispanic ethnicity – no. (%) | 7 (18%) | 6 (16%) | 0.84 |

| Liver enzymes | |||

| Alanine aminotransferase – U/L | 80 (41) | 68 (33) | 0.14 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase – U/L | 57 (32) | 50 (25) | 0.30 |

| Alkaline phosphatase – U/L | 76 (25) | 76 (24) | 0.96 |

| γ-Glutamyltransferase – U/L | 80 (103) | 61 (46) | 0.28 |

| Total bilirubin – mg/dL | 0.7 (0.3) | 0.6 (0.3) | 0.35 |

| Lipids | |||

| Cholesterol | |||

| Total – mg/dL | 192 (42) | 194 (48) | 0.87 |

| High-density lipoprotein – mg/dL | 44 (13) | 44 (15) | 0.83 |

| Low-density lipoprotein – mg/dL | 110 (36) | 115 (40) | 0.57 |

| Trigylcerides – mg/dL | 193 (89) | 180 (17) | 0.57 |

| Metabolic factors | |||

| Fasting serum glucose – mg/dL | 117 (35) | 107 (28) | 0.16 |

| Insulin – umol/mL | 39 (56) | 21 (15) | 0.06 |

| HOMA–IR∥ – mg/dL × umol/mL / 405 | 12.4 (18.6) | 3.8 (6.0) | 0.04 |

| Hemoglobin A1c – % | 6.4 (1.1) | 6.3 (0.9) | 0.56 |

| Weight – kg | 97 (18) | 94 (15) | 0.41 |

| Body–mass index – kg/m2 | 34 (5) | 33 (5) | 0.19 |

| Waist circumference – cm | 113 (12) | 108 (11) | 0.07 |

| Waist to hip ratio | 0.97 (0.07) | 0.94 (0.07) | 0.04 |

| Systolic blood pressure – mmHg | 132 (15) | 133 (16) | 0.80 |

| Diastolic blood pressure – mmHg | 78 (10) | 79 (11) | 0.33 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Hyperlipidemia¶ – no. (%) | 21 (52%) | 20 (53%) | 0.99 |

| Hypertension – no. (%) | 20 (50%) | 21 (55%) | 0.64 |

| Cardiovascular disease – no. (%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (3%) | 0.30 |

| Diabetes – no. (%) | 20 (50%) | 20 (53%) | 0.82 |

| Concomitant medications in the past 6 months | |||

| Antilipidemic – no. (%) | 19 (48%) | 15 (39%) | 0.48 |

| Cardiovascular/hypertensive – no. (%) | 24 (60%) | 27 (71%) | 0.30 |

| Antidiabetic – no. (%) | 22 (55%) | 21 (55%) | 0.98 |

| Metformin – no. (%) | 20 (50%) | 19 (50%) | 1.00 |

| Pioglitazone – no. (%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (3%) | 0.30 |

| Vitamin E – no. (%) | 7 (18%) | 12 (32%) | 0.15 |

| Aspirin – no. (%) | 10 (25%) | 12 (32%) | 0.52 |

| Liver histology findings | |||

| Definite steatohepatitis – no. (%) | 31 (78%) | 30 (79%) | 0.88 |

| Fibrosis – stage† | 1.9 (1.1) | 1.7 (1.1) | 0.59 |

| Total NAFLD activity score‡ | 5.1 (1.3) | 5.4 (1.4) | 0.29 |

| Hepatocellular ballooning – score | 1.4 (0.8) | 1.4 (0.7) | 0.91 |

| Steatosis – score | 1.9 (0.8) | 2.1 (0.8) | 0.32 |

| Lobular inflammation – score | 1.8 (0.7) | 1.9 (0.8) | 0.47 |

| Portal inflammation – score§ | 1.2 (0.6) | 1.2 (0.6) | 0.76 |

| MRI-PDFF - % | |||

| Mean (SD) | 18 (9) | 20 (10) | 0.41 |

| Median [IQR] | 19 [10, 23] | 17 [12, 25] |

Plus–minus values are means±SD.

High cholesterol or high triglyerides

Fibrosis was assessed on a scale of 0 to 4, with higher scores indicating more severe fibrosis.

Total nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) activity was assessed on a scale of 0 to 8, with higher scores indicating more severe disease; the components of this measure are steatosis (assessed on a scale of 0 to 3), lobular inflammation (assessed on a scale of 0 to 3), and hepatocellular ballooning (assessed on a scale of 0 to 2).

Portal inflammation was assessed on a scale of 0 to 2 with higher scores indicating more severe inflammation.

Homeostasis Model Assessment-estimated Insulin Resistance

Decline in MRI-PDFF in obeticholic acid versus placebo:

Obeticholic acid, 25 mg orally once daily, was better than placebo in improving hepatic liver fat as assessed by MRI-PDFF with an absolute difference of −3.4% (95% CI, −6.5 to −0.2%, p-value=0.04), and relative difference of −17% (95% CI, −34 to 0%, p-value=0.05).

Association between MRI-PDFF decline and liver histology change:

An absolute decrease in MRI-PDFF of 4.8% (p-value<0.001) or a relative decrease in MRI-PDFF of 26% (p-value<0.001) from baseline was associated with a 1-point improvement in steatosis grade (Table 2). Data were consistent for both OCA and placebo groups.

Table 2.

Association of 72-week change in MRI-PDFF with treatment and changes in steatosis score and weight

| Independent variable | Change in MRI-PDFF | Difference / slope* | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OCA vs placebo | Absolute | −3.4% | −6.5, −0.2 | 0.04 |

| Relative | −17% | −34, 0 | 0.05 | |

| Change in steatosis | Absolute | 4.9% / score | 3.2, 6.6 | <0.001 |

| Relative | 26% / score | 18, 35 | <0.001 | |

| Change in weight | Absolute | 0.7% / kg | 0.4, 1.0 | <0.001 |

| Relative | 2.8% / kg | 1.3, 4.3 | <0.001 | |

| Weight loss ≥5% vs <5%† | Absolute | −7.9% | −11.7, −4.1 | <0.001 |

| Relative | −29% | −51, −8 | 0.007 |

Estimated using robust regression adjusting for baseline MRI-PDFF

18% (14/78) patients lost ≥5% body weight

Association between MRI-PDFF and weight change:

We also examined the association between changes in MRI-PDFF and weight change (Table 2). There was a clinically as well as statistically significant association between MRI-PDFF and weight change. We compared those who had ≥ 5% weight loss versus less than 5% weight loss and found that a ≥ 5% weight loss was associated with a 29% (95% CI, −51% to −8%, p-value <0.007) relative reduction in MRI-PDFF (Table 2).

Association between a 30% reduction in MRI-PDFF and histologic response:

Primary outcome:

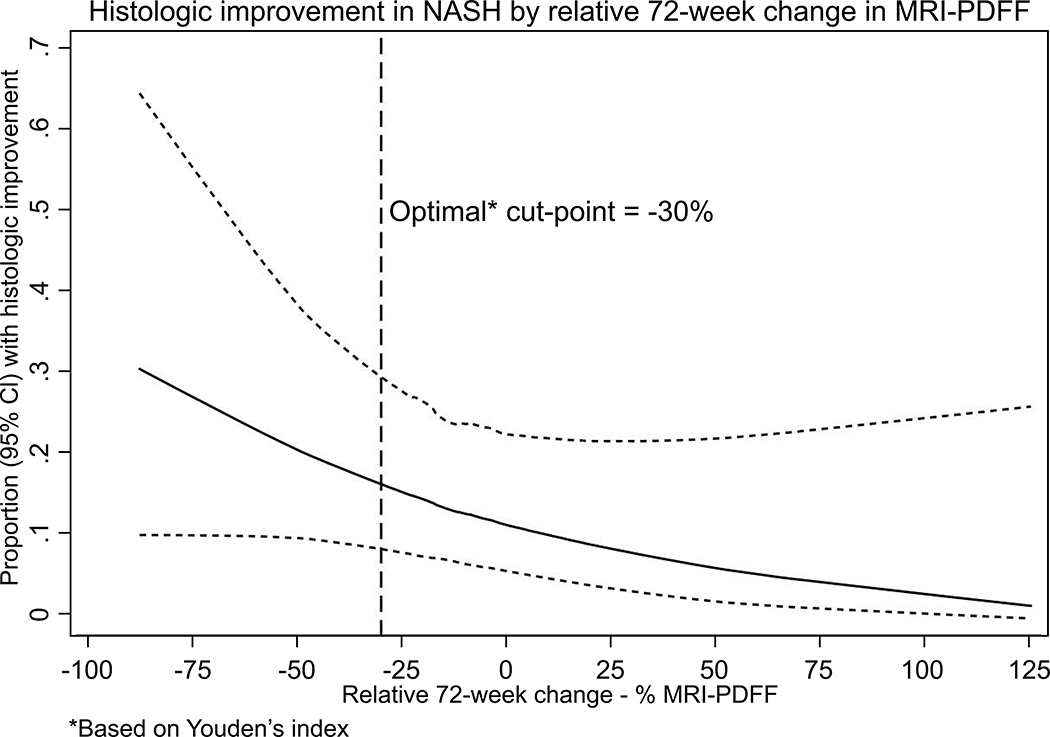

Greater reduction in MRI-PDFF was associated with greater odds of improvement in NAFLD activity score. We examined the optimal cut-point for relative decline in MRI-PDFF using Youden’s index and it was found to be 29.8 % (defined as MRI-PDFF responder). Then we divided the entire trial cohort (including OCA and placebo-treated patients) into those who had a 30% decline in MRI-PDFF (MRI-PDFF responders) versus < 30% decline in MRI-PDFF (MRI-PDFF non-responders). When comparing those with ≥ 30% reduction in MRI-PDFF versus those with < 30% reduction in MRI-PDFF, the proportion with a 2-point improvement in NAS without worsening of fibrosis was 50% versus 19% respectively, with statistically significant odds of histologic response (OR 4.86, 95% CI, 1.4–12.8, p-value <0.009, please see table 3.

Table 3.

Performance diagnostics of 72-week relative change in PDFF in assessing histologic improvement and resolution of NASH

| Event | Prevalence of event | Cross-validated AUROC (95% CI) | Cutoff criteria | Cutoff (Relative change in PDFF) | Sens | Spec | PPV | NPV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Histologic improvement | 27% | 0.60 (0.45, 0.75) | Sens = 90% | 23.1% | Fixed | 23% | 30% | 87% |

| Spec = 90% | −57.3% | 10% | Fixed | 29% | 73% | |||

| Youden’s index | −29.8% | 48% | 81% | 48% | 81% |

Secondary outcomes (Table 3):

When comparing MRI-PDFF responders versus MRI-PDFF non-responders, the rate of resolution of NASH was 20% versus 10%, and the proportion with a 1-stage improvement in fibrosis stage was 20% versus 19%, respectively and these trends were not statistically significant. The odds of resolution of NASH was 2.2 (95% CI, 0.5–8.6, p-value <0.27) and the odds of improvement in one-stage of fibrosis was OR 1.1 (95% CI, 0.3–3.8, p-value 0.92), respectively.

When comparing MRI-PDFF responders versus MRI-PDFF non-responders,, the proportion with a ≥ 1-point improvement in steatosis grade was 85% versus 25% as expected with an odds ratio of 14.9 (95% CI, 3.8–57.7, p-value <0.001), respectively; and the rate of≥ 1-point improvement in ballooning was 50% versus 26% with an odds ratio of 2.9 (95% CL, 1.0–8.2, p-value <0.05). There was no significant association between change in MRI-PDFF and lobular inflammation and portal inflammation.

In sensitivity analysis, we examined the optimal cut-point of MRI-PDFF that was associated with histologic response. The optimal cut-point of MRI-PDFF associated with histologic response in this trial was 29.8% relative MRI-PDFF reduction, which was statistically significant (P-value < 0.05) as shown in Table 4. In addition, as shown in figure 2, greater reduction in MRI-PDFF was associated even higher odds of histologic response.

Table 4.

Association of at least 30% relative decrease at 72 weeks in MRI-PDFF with histologic outcomes

| Relative Decrease in MRI-PDFF | ≥30% vs <30% Relative Decrease in MRI-PDFF | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Histologic Outcome (1+ score/stage decrease) | ≥30% (n=20) | <30% (n=58) | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | P-value |

| Steatosis | 85% | 28% | 14.9 | 3.8, 57.7 | <0.001 |

| Lobular Inflammation | 45% | 45% | 1.0 | 0.4, 2.8 | 0.99 |

| Portal inflammation | 15% | 12% | 1.3 | 0.3, 5.5 | 0.74 |

| Ballooning | 50% | 26% | 2.9 | 1.0, 8.2 | 0.05 |

| Fibrosis | 20% | 19% | 1.1 | 0.3, 3.8 | 0.92 |

| Histologic improvement* | 50% | 19% | 4.3 | 1.4, 12.8 | 0.009 |

| Resolution of NASH | 20% | 10% | 2.2 | 0.5, 8.6 | 0.27 |

Decrease in NAFLD Activity Score (NAS) of at least 2 points and no worsening of fibrosis

Sub-group analysis by weight loss and ALT response (supplementary Table 1a and 1b):

We also analyzed the data stratified by weight loss of ≥ 5% versus < 5%, and ALT decline by 17 IU/L versus < 17 IU/L for histologic response. These data are shown in supplementary Table 1a and 1b. The rate of histologic response among those who achieved ≥ 5% weight loss versus < 5% was 43% and 23, p-value 0.14. The rate of histologic response among those who had a relative decline in ALT by ≥ 17 IU/L versus < 17 IU/L was 37% and 19%, respectively, p-value 0.07. Among the three response variables including MRI-PDFF ≥ 30% decline versus weight loss ≥ 5% versus ALT decline ≥ 17 IU/L, only MRI-PDFF responders showed a significant association with histologic response.

DISCUSSION:

Main findings:

This secondary analysis of the FLINT trial provides novel paired MRI-PDFF and liver histology data over 72 weeks in the setting of a multicenter clinical trial. Obeticholic acid was better than placebo in reducing liver fat as assessed by MRI-PDFF. This multicenter trial provides validation data regarding the association between histologic response and a 30% decline in MRI-PDFF relative to baseline. This study provides novel data on the clinically relevant decline in liver fat that may be associated with histologic response in NASH in a NASH trial. This helps validate that a 30% decline in MRI-PDFF may be used as a potential treatment response criteria for early phase clinical trials in NASH when a reduction in liver fat is targeted.

In context with published literature:

Patel and colleagues have previously shown that a 30% decline in MRI-PDFF is associated with 2-point improvement in NAFLD activity score20. These data were recently confirmed in a Phase 2b trial of selonsertib treatment with or without simtuzumab over a 24-week period showing that a 30% decline in liver fat was associated with higher odds of histologic response 23. In the ASK-1 trial of selonsertib, a 30% decline in liver fat was statistically significantly associated with higher odds in reduction in steatosis grade as well as a 2-point improvement in NAS23. In the current study, we provide a validation of the concept that at a threshold of 30% reduction in liver fat is associated with histologic improvements by 2 points in NAFLD Activity Score without worsening of fibrosis. Whether this finding applies to improvements seen with other therapies will need to be established. Furthermore, we also found trends in higher odds of improvement in ballooning and resolution of NASH. There was no significant improvement seen in fibrosis. In addition, a 5% weight loss is associated with a significant decline in liver fat by MRI-PDFF as previously shown24.Allen and colleagues have recently suggested the role of 3D MRE in assessing changes after bariatric surgery and these may be helpful in assessing treatment response in future studies in addition to MRI-PDFF25. Furthermore, Harrison and colleagues have recently demonstrated that Resmetirom, a thyroid β receptor agonist, is associated with significant reduction in MRI-PDFF and it may be associated with improvement in liver histology in patients with biopsy-proven NASH.26

Strengths and limitations:

Strengths of this study include the use of multicenter trial including 78 patients who underwent paired MRI-PDFF and liver biopsy assessment over a 72 week period. This is longest trial with paired MRI-PDFF and liver biopsy assessment to date. The MRI-PDFF was centrally read and both radiologists and pathologists were masked to clinical as well as pathology and radiology data, respectively. The baseline MRI-PDFF between the OCA and the placebo group was similar. We acknowledge following limitations. MRI-PDFF was only available in a subset of FLINT trial participants. This trial did not include magnetic resonance elastography (MRE) or vibration controlled transient elastography assessment so we were not able to assess changes in elastography in this trial and its association with changes in liver histology or MRI-PDFF27–29. Therefore, future studies are needed to incorporate a more detailed elastography based assessment in the setting of NASH trials. Furthermore, this study was of a modest size and thus lacked the power to detect differences in changes in liver fat and fibrosis progression or regression30. Therefore, future studies with larger sample sizes are needed to better understand the temporal association between changes in MRI-PDFF and fibrosis change in the setting of NASH trials30, 31.

Implications for future research and clinical trial design:

MRI-PDFF is an accurate measure of liver fat content and has the advantage compared to histology in providing a continuous variable is assessing quantitative changes in liver fat in the setting of treatment trials12, 15, 30, 32, 33. However, it is neither designed nor capable of providing an estimate in the changes in other key variables associated with changes in disease activity and severity in NASH and NASH-related fibrosis, respectively34. In this study, we demonstrated that when there is a significant reduction in MRI-PDFF beyond a threshold of 30% then improvements in other features related to disease activity such as ballooning, lobular inflammation, or steatosis are also more likely to be seen. These data suggest that a relative reduction of MRI-PDFF of at least 30% is a useful clinical biomarker for early phase clinical trials given its association with a 2-point improvement in NAS along with improvements in steatosis and ballooning. Quantitative biomarkers of liver inflammation, ballooning, Mallory-Denk bodies and fibrosis are still needed in combination with MRI-PDFF in future trials for assessment of treatment response35, 36.

Supplementary Material

Figure 1: Histologic response in NASH increases as relative decline in MRI-PDFF increases.

The y axis represents the proportion of patients who achieved histologic response and the X-axis denotes relative change (decrease towards the left and increase towards the right) in MRI-PDFF. These data include both the OCA and the placebo group. The dotted vertical line represents the optimal cut-point for MRI-PDFF decline at 30% (p-value < 0.05%)

Acknowledgments

Funding Support: The Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Clinical Research Network (NASH CRN) is supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) (grants U01DK061718, U01DK061728, U01DK061731, U01DK061732, U01DK061734, U01DK061737, U01DK061738, U01DK061730, U01DK061713). Additional support is received from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) (grants UL1TR000439, UL1TR000077, UL1TR000436, UL1TR000150, UL1TR000424, UL1TR000006, UL1TR000448, UL1TR000040, UL1TR000100, UL1TR000004, UL1TR000423, UL1TR000058, UL1TR000454). This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute. The FLINT trial was conducted by the NASH CRN and supported in part by a Collaborative Research and Development Agreement (CRADA) between NIDDK and Intercept Pharmaceuticals. FLINT: NCT01265498

Role of study sponsor: The study sponsor(s) had no role in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of the data, and/or drafting of the manuscript. All authors report that no conflicts of interest exist.

Conflict of interests:

Dr. Loomba serves on the steering committee of the REGENERATE Trial funded by Intercept Pharmaceuticals. In addition, he has received research grants from Siemens diagnostics and GE. He has research collaborations with AMRA and Antaros. He serves as a consultant or advisory board member for Arrowhead Pharmaceuticals, AstraZeneca, Bird Rock Bio, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myer Squibb, Celgene, Cirius, CohBar, Conatus, Eli Lilly, Galmed, Gemphire, Gilead, Glympse bio, GNI, GRI Bio, Intercept, Ionis, Janssen Inc., Merck, Metacrine, Inc., NGM Biopharmaceuticals, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Prometheus, Sanofi, Siemens, and Viking Therapeutics. In addition, his institution has received grant support from Allergan, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cirius, Eli Lilly and Company, Galectin Therapeutics, Galmed Pharmaceuticals, GE, Genfit, Gilead, Intercept, Janssen, Madrigal Pharmaceuticals, Merck, NGM Biopharmaceuticals, NuSirt, Pfizer, Prometheus, and Siemens. He is also co-founder of Liponexus, Inc.

Dr. Tetri has consulted for Allergan, Arrowhead, Boehringer Ingleheim, BMS, Coherus, Consynance, Cymabay, Enanta, Gelesis, Gilead, Intercept, Karos, Lexicon, Madrigal, Merck, Metacrine, NGM, Prometheus. His institution has received grant support from Allergan, Bristol Myers Squibb, Cirius, Enanta, Genfit, Gilead, Intercept, Madrigal and Prometheus.

Dr. Sanyal received grants from Bristol Myers, Conatus, Galectin, Gilead, Mallinckrodt, Novartis, Salix, Sequana, is the President of Sanyal Bio, has stock options in Akarna, Durect, Genfit, Indalo, Tiziana, is a consultant to Ardelyx, Birdrock, Boehringer Ingelhiem, ENYO, Exhalenz, GenFit, Hemoshear, Jannsen, Lilly, Merck, Nimbus, Nitto Denko, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Takeda, Terns, Surrozen, Siemens, Poxel, 89 Bio and BASF is an unpaid consultant to Affimmune, Albireo, Chemomab, Ecosens-Sandhill, Fractyl, Immuron, Intercept, Zydus, and receives royalties from Elseiver, and Uptodate outside the submitted work. He has ongoing unpaid active research collaborations with AMRA, Perspectum, Antaros, Second Genome and OWL.

Dr. Chalasani has ongoing paid consulting activities (or had in preceding 12 months) with NuSirt, Abbvie, Afimmune (DS Biopharma), Allergan (Tobira), Madrigal, Coherus, Siemens, La Jolla, Foresite labs, and Genentech. These consulting activities are generally in the areas of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and drug hepatotoxicity. Dr. Chalasani receives research grant support from Exact Sciences, Intercept, and Galectin Therapeutics where his institution receives the funding.

Dr. Diehl has consulted for Allergan, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Celgene, Lumena, Novartis, Pfizer, Pliant, Quest Diagnostics, and twoXAR. She has research collaborations with Allergan, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Conatus, Exalenze, Galactin, Galmed, Genfit, Gilead, Immuron, Intercept, Madrigal Metabolomics, NGM Pharmaceuticals, Prometheus, and Shire.

Dr. Terrault has received institutional grant and research support from Gilead and Allergan.

Dr. Kowdley has consulted for Corcept, Gilead, Enanta, Intercept, and Verlyx. His institution has received grant and research support from Allergan, Enanta, Galectin, Gilead, Immuron, Intercept, Prometheus, and Zydus. Dr. Kowdley is on the Advisory Board for Conatus and Gilead, and on the Speaker Bureau for Gillead and Intercept.

Dr. Behling is a consultant for ICON and Covance.

Dr. Lavine is an ad hoc consultant for Allergan, Gilead, Merck, Pfizer, Novartis.

Dr. Middleton serves as consultant to Arrowhead, Kowa, Median, and Novo Nordisk. He owns or has recently owned stock in General Electric and Pfizer, and is or was a co-investigator on grants from Gilead, Guerbet and Organovo. In addition, his institution has received support through laboratory services agreements with Alexion, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Enanta, Galmed, Genzyme, Gilead, Intercept, Isis, Janssen, NuSirt, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi, Shire, Synageva, and Takeda.

Dr. Sirlin received research grants from Bayer, Celgene, GE, Gilead, Philips, Siemens, personal consulting for Blade, Boehringer, Epigenomics, is a representative for institutional consultation for BMS, Exact Sciences, IBM-Watson, has active lab service agreements with Enanta, Gilead, ICON, Intercept, Organovo, Nusirt, Shire, Synageva, Takeda, and completed lab service agreements with: Alexion, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Galmed, Genzyme, Isis, Janssen, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi, Virtualscopics.

No COI: Srinivasan Dasarathy, David Kleiner, Mark Van Natta, James Tonascia

Abbreviations:

- NAFLD

nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

- NASH

nonalcoholic steatohepatitis

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- PDFF

proton-density-fat-fraction

- NAS

NAFLD Activity Score

- ROI

region of interest

- BMI

body mass index

- ROC

receiver operating characteristic

- AUROC

area under receiver operating characteristic

Appendix:

Members of the Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Clinical Research Network

Adult Clinical Centers

Cleveland Clinic Foundation, Cleveland, OH: Daniela Allende, MD; Srinivasan Dasarathy, MD; Arthur J. McCullough, MD; Revathi Penumatsa, MPH; Jaividhya Dasarathy, MD

Columbia University, New York, NY: Joel E. Lavine, MD, PhD

Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC: Manal F. Abdelmalek, MD, MPH; Mustafa Bashir, MD; Stephanie Buie; Anna Mae Diehl, MD; Cynthia Guy, MD; Christopher Kigongo, MB, CHB; Mariko Kopping, MS, RD; David Malik; Dawn Piercy, MS, FNP

Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN: Naga Chalasani, MD; Oscar W. Cummings, MD; Samer Gawrieh, MD; Linda Ragozzino, RN; Kumar Sandrasegaran, MD; Raj Vuppalanchi, MD

Saint Louis University, St Louis, MO: Elizabeth M. Brunt, MD (2002–2008); Theresa Cattoor, RN; Danielle Carpenter, MD; Janet Freebersyser, RN; Debra King, RN (2004–2015); Jinping Lai, MD (2015–2016); Brent A. Neuschwander-Tetri, MD; Joan Siegner, RN (2004–2015); Susan Stewart, RN (2004–2015); Susan Torretta; Kristina Wriston, RN (2015)

Swedish Medical Center, Seattle, WA: Maria Cardona Gonzalez; Jodie Davila; Manan Jhaveri, MD; Kris V. Kowdley, MD; Nizar Mukhtar, MD; Erik Ness, MD; Michelle Poitevin; Brook Quist; Sherilynn Soo

University of California San Diego, San Diego, CA: Brandon Ang; Cynthia Behling, MD, PhD; Archana Bhatt; Rohit Loomba, MD, MHSc; Michael S. Middleton, MD, PhD; Claude Sirlin, MD

University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, CA: Maheen F. Akhter, BS; Nathan M. Bass, MD, PhD (2002–2011); Danielle Brandman, MD, MAS; Ryan Gill, MD, PhD; Bilal Hameed, MD; Jacqueline Maher, MD; Norah Terrault, MD, MPH; Ashley Ungermann, MS

University of Washington Medical Center, Seattle, WA: Matthew Yeh, MD, PhD

Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA: Sherry Boyett, RN, BSN; Melissa J. Contos, MD; Sherri Kirwin; Velimir AC Luketic, MD; Puneet Puri, MD (2009–2017); Arun J. Sanyal, MD; Jolene Schlosser, RN, BSN; Mohammad S. Siddiqui, MD; Leslie Yost-Schomer, RN

Washington University, St. Louis, MO: Elizabeth M. Brunt, MD (2008–2015); Kathryn Fowler, MD (2012–2015)

Resource Centers

National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD: David E. Kleiner, MD, PhD

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Bethesda, MD: Edward C. Doo, MD; Sherry Hall, MS; Jay H. Hoofnagle, MD; Patricia R. Robuck, PhD, MPH (2002–2011); Averell H. Sherker, MD; Rebecca Torrance, RN, MS

Data Coordinating Center, Johns Hopkins University, Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD: Patricia Belt, BS; Jeanne M. Clark, MD, MPH; John Dodge; Michele Donithan, MHS; Milana Isaacson, BS; Mariana Lazo, MD, PhD, ScM; Jill Meinert; Laura Miriel, BS; Emily P. Sharkey, MPH, MBA; Jacqueline Smith, AA; Michael Smith, BS; Alice Sternberg, ScM; James Tonascia, PhD; Mark L. Van Natta, MHS; Annette Wagoner; Laura A. Wilson, ScM; Goro Yamada, PhD, MHS, MHS, MMS; Katherine Yates, ScM

Radiology Reading Center, University of California San Diego, San Diego, CA: Yesenia Covarrubias; Anthony Gamst, PhD; Gavin Hamilton, PhD; Walter Henderson, BA; Jonathan Hooker, BS; Joel E. Lavine, MD, PhD (Columbia University); Rohit Loomba, MD, MHSc; Michael S. Middleton, MD, PhD; Alexandria Schlein, BS; Jeffrey B. Schwimmer, MD; Wei Shen, PhD (Columbia University); Claude Sirlin, MD; Tanya Wolfson, MA

Contributor Information

Rohit Loomba, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, CA, USA.

Brent A Neuschwander-Tetri, Saint Louis University, St. Louis, MO, USA.

Arun Sanyal, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA, USA.

Naga Chalasani, Indiana University, Indianapolis, IN, USA.

Anna Mae Diehl, Duke University, Durham, NC, USA.

Norah Terrault, University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, CA USA.

Kris Kowdley, Swedish Medical Center, Seattle, WA, USA.

Srinivasan Dasarathy, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH, USA.

David Kleiner, The National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD, USA.

Cynthia Behling, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, CA, USA.

Joel Lavine, Columbia University, New York, NY, USA.

Mark Van Natta, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, USA.

Michael Middleton, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, CA, USA.

James Tonascia, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, USA.

Claude Sirlin, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, CA, USA.

References

- 1.Chalasani N, Younossi Z, Lavine JE, et al. The diagnosis and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Practice guidance from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology 2018;67:328–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dulai PS, Singh S, Patel J, et al. Increased risk of mortality by fibrosis stage in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Hepatology 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Loomba R, Abraham M, Unalp A, et al. Association between diabetes, family history of diabetes, and risk of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and fibrosis. Hepatology 2012;56:943–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Williams CD, Stengel J, Asike MI, et al. Prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis among a largely middle-aged population utilizing ultrasound and liver biopsy: a prospective study. Gastroenterology 2011;140:124–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Targher G, Day CP, Bonora E. Risk of cardiovascular disease in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. N Engl J Med 2010;363:1341–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Noureddin M, Zhang A, Loomba R. Promising therapies for treatment of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs 2016;21:343–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Konerman MA, Jones JC, Harrison SA. Pharmacotherapy for NASH: Current and emerging. J Hepatol 2018;68:362–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Younossi ZM, Loomba R, Rinella ME, et al. Current and future therapeutic regimens for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology 2018;68:361–371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kleiner DE, Brunt EM, Van Natta M, et al. Design and validation of a histological scoring system for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 2005;41:1313–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rockey DC, Caldwell SH, Goodman ZD, et al. Liver biopsy. Hepatology 2009;49:1017–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Loomba R Role of imaging-based biomarkers in NAFLD: Recent advances in clinical application and future research directions. J Hepatol 2018;68:296–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Younossi ZM, Loomba R, Anstee QM, et al. Diagnostic modalities for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, and associated fibrosis. Hepatology 2018;68:349–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Loomba R, Sanyal AJ, et al. Farnesoid X nuclear receptor ligand obeticholic acid for non-cirrhotic, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (FLINT): a multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2015;385:956–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Middleton MS, Heba ER, Hooker CA, et al. Agreement Between Magnetic Resonance Imaging Proton Density Fat Fraction Measurements and Pathologist-Assigned Steatosis Grades of Liver Biopsies From Adults With Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology 2017;153:753–761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Caussy C, Reeder SB, Sirlin CB, et al. Non-invasive, quantitative assessment of liver fat by MRI-PDFF as an endpoint in NASH trials. Hepatology 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Loomba R, Sirlin CB, Ang B, et al. Ezetimibe for the treatment of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: assessment by novel magnetic resonance imaging and magnetic resonance elastography in a randomized trial (MOZART trial). Hepatology 2015;61:1239–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Le TA, Chen J, Changchien C, et al. Effect of colesevelam on liver fat quantified by magnetic resonance in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: a randomized controlled trial. Hepatology 2012;56:922–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cui J, Philo L, Nguyen P, et al. Sitagliptin vs. placebo for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A randomized controlled trial. J Hepatol 2016;65:369–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yokoo T, Serai SD, Pirasteh A, et al. Linearity, Bias, and Precision of Hepatic Proton Density Fat Fraction Measurements by Using MR Imaging: A Meta-Analysis. Radiology 2018;286:486–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patel J, Bettencourt R, Cui J, et al. Association of noninvasive quantitative decline in liver fat content on MRI with histologic response in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Therap Adv Gastroenterol 2016;9:692–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jayakumar S, Middleton MS, Lawitz EJ, et al. Longitudinal correlations between MRE, MRI-PDFF, and liver histology in patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: Analysis of data from a phase II trial of selonsertib. J Hepatol 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Noureddin M, Lam J, Peterson MR, et al. Utility of magnetic resonance imaging versus histology for quantifying changes in liver fat in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease trials. Hepatology 2013;58:1930–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jayakumar S, Middleton MS, Lawitz EJ, et al. Longitudinal correlations between MRE, MRI-PDFF, and liver histology in patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: Analysis of data from a phase II trial of selonsertib. J Hepatol 2019;70:133–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patel NS, Doycheva I, Peterson MR, et al. Effect of weight loss on magnetic resonance imaging estimation of liver fat and volume in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;13:561–568 e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Allen AM, Shah VH, Therneau TM, et al. The Role of Three-Dimensional Magnetic Resonance Elastography in the Diagnosis of Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis in Obese Patients Undergoing Bariatric Surgery. Hepatology 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harrison SA, Bashir MR, Guy CD, et al. Resmetirom (MGL-3196) for the treatment of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sanyal A, Charles ED, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, et al. Pegbelfermin (BMS-986036), a PEGylated fibroblast growth factor 21 analogue, in patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2a trial. Lancet 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ajmera VH, Liu A, Singh S, et al. Clinical utility of an increase in magnetic resonance elastography in predicting fibrosis progression in NAFLD. Hepatology 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Loomba R, Lawitz E, Mantry PS, et al. The ASK1 inhibitor selonsertib in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: A randomized, phase 2 trial. Hepatology 2018;67:549–559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ajmera V, Park CC, Caussy C, et al. Magnetic Resonance Imaging Proton Density Fat Fraction Associates With Progression of Fibrosis in Patients With Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Gastroenterology 2018;155:307–310 e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Loomba R, Sanyal AJ, Kowdley KV, et al. Factors Associated With Histologic Response in Adult Patients With Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology 2019;156:88–95 e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Caussy C, Alquiraish MH, Nguyen P, et al. Optimal threshold of controlled attenuation parameter with MRI-PDFF as the gold standard for the detection of hepatic steatosis. Hepatology 2018;67:1348–1359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harrison SA, Rinella ME, Abdelmalek MF, et al. NGM282 for treatment of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet 2018;391:1174–1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dulai PS, Sirlin CB, Loomba R. MRI and MRE for non-invasive quantitative assessment of hepatic steatosis and fibrosis in NAFLD and NASH: Clinical trials to clinical practice. J Hepatol 2016;65:1006–1016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tapper EB, Loomba R. Noninvasive imaging biomarker assessment of liver fibrosis by elastography in NAFLD. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Castera L, Friedrich-Rust M, Loomba R. Noninvasive Assessment of Liver Disease in Patients With Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Gastroenterology 2019;156:1264–1281 e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.