Abstract

Workload-indexed blood pressure response (wiBPR) to exercise has been shown to be superior to peak systolic blood pressure (SBP) in predicting mortality in healthy men. Thus far, however, markers of wiBPR have not been evaluated for athletes and the association with vascular function is unclear. We examined 95 male professional athletes (26±5 y) and 30 male controls (26±4 y). We assessed vascular functional parameters at rest and wiBPR with a graded bicycle ergometer test and compared values for athletes with those of controls. Athletes had a lower pulse wave velocity (6.4±0.9 vs. 7.2±1.5 m/s, p=0.001) compared to controls. SBP/Watt slope (0.34±0.13 vs. 0.44±0.12 mmHg/W), SBP/MET slope (6.2±1.8 vs. 7.85±1.8 mmHg/MET) and peak SBP/Watt ratio (0.61±0.12 vs. 0.95±0.17 mmHg/W) were lower in athletes than in controls (p<0.001). The SBP/Watt and SBP/MET slope in athletes were comparable to the reference values, whereas the peak SBP/Watt-ratio was lower. All vascular functional parameters measured were not significantly correlated to the wiBPR in either athletes or controls. In conclusion, our findings indicate the potential use of the SBP/Watt and SBP/MET slope in pre-participation screening of athletes. Further, vascular functional parameters, measured at rest, were unrelated to the wiBPR in athletes and controls.

Key words: Exercise test, athletes, SBP/MET slope, workload-indexed blood pressure response, pulse wave analysis, arterial hypertension

Introduction

Blood pressure response (BPR) to exercise testing has been recognized for its potential to uncover otherwise undetectable cardiovascular (CV) pathology and future CV risk in two different settings: routine clinical investigations of the general population 1 2 , and in pre-participation screenings of athletes 3 4 5 . Hence, knowledge of what constitutes a normal or abnormal blood pressure response (BPR) to exercise is a crucial component of the cardiovascular evaluation.

Though, studies investigating the BPR to exercise delivered inconsistent results with some studies indicating a lower cardiovascular risk with a lower maximum systolic blood pressure (SBP) 2 and other studies suggesting exactly the opposite 6 7 . In conclusion, the clinical impact of blood pressure response (BPR) during exercise still remains a controversial issue 8 9 10 , and the European Society of Cardiology states in its latest guideline that there is currently no consensus on normal BPR during exercise 11 .

Therefore a call to re-evaluate guidelines for BPR to exercise has recently been made, intended to stimulate research into establishing more reliable markers of BPR 12 . At the same time, novel markers of vascular function have emerged whose feasibility for acquisition at rest via noninvasive oscillometric devices could simplify clinical assessment in uncovering functional impairment 13 14 . Functional vascular impairment might lead to an exaggerated BPR to exercise even in the absence of hypertension at rest 15 16 . Further, arterial stiffness predicted an exaggerated BPR in young individuals 17 , indicating that vascular functional assessment might provide additional information for cardiovascular risk classification.

Acknowledging these discoveries, Hedman et al. investigated a workload-indexed BPR (wiBPR), expressed as the slope of systolic blood pressure in response to workload (SBP/MET slope) 6 , and demonstrated that currently proposed thresholds for BPR to exercise did not align well with observations in their middle-aged population. The 10 mmHg/MET benchmark that has been discussed to constitute a normal increase 18 was far in excess of the 5 mmHg/MET and 10 mmHg/MET observed by Hedman et al. 6 to represent the 50th and 95th percentile in their study’s low-risk sub-population. Moreover, a SBP/MET slope >6.2 mmHg/MET was associated with a 27% higher risk of mortality over 20 years in males compared with those with a SBP/MET slope <4.3 mmHg/MET 6 .

These findings underscore that current threshold recommendations for BPR to exercise lack clinical utility. Further, these observations highlight the need for the development of normative values of wiBPR for athletes’ pre-participation evaluation. We have shown that male athletes present with a mean SBP/MET slope of 5.4 mmHg/MET and that those with the lowest SBP/MET slope also displayed the lowest maximum SBP and the highest performance level 19 . Consistent with these results, we recently demonstrated that the resistance index, as a direct physical marker of global vascular resistance, was able to predict maximum power output in elite athletes 20 .

Therefore, we now investigated vascular function and the newly introduced markers of wiBPR, specifically SBP/W slope and peak SBP/W ratio 21 in a cohort of professional male athletes and male controls. The peak SBP/W ratio represents the ratio of peak SBP to maximum achieved watts (W) in response to bicycle ergometer, whereas the SBP/W slope reflects the increase of SBP per W increment and thus the steepness of SBP in relation to workload, with higher values representing a steeper increase 21 .

We hypothesized that athletes would display an enhanced vascular function compared to controls with measureable differences at rest. Further, we anticipated finding a lower wiBPR in athletes compared to controls and to recently published normative values 21 as a result of this enhanced vascular function. In addition, we expected to find significant correlations of vascular functional parameters with the wiBPR in athletes and controls.

Materials and Methods

Study design

The study was conducted as a cross-sectional, single-center pilot study as part of the routine pre-season medical monitoring program of the first German handball division. Data were collected in the second half of July in the years 2017–2019 after a six-week competition-free interval. Competitive team handball is classified as high-intensity mixed sports with a high load for the cardiovascular system. It is characterized by requiring the repetition of high-intensity activities with brief recovery periods. Players need the ability to perform repeated maximal or near-maximal intensities such as sprinting, jumping, and changing of directions throughout the match.

Age-matched male controls were recruited as volunteers and included in the study when they participated in sports activities <1 hour per week.

All participants received a clear explanation of the study and provided their written informed consent. Further, they filled out a questionnaire regarding health status, medication, nutrition supplementation, amount of training, and history of training (pre-participation questionnaire of the European Federation of Sports Medicine Associations). Only healthy individuals free of underlying cardiovascular diseases, risk factors, and medication were included. The local ethics committee approved the study protocol. The study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards in sport and exercise science research 22 .

Study population

The participants were 95 healthy male professional handball players of the first German division and 30 healthy male controls. All participants included were Caucasians, non-smokers, and none took medication or multivitamin supplements. Age, height, weight, and body mass index were determined. Body surface area was calculated using the formula of DuBois and DuBois 23 .

Exercise testing and assessment of blood pressure, heart rate and performance

All individuals were subjected to a physical examination and 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG). Further, all participants underwent a standardized progressive maximal cycling ergometer test with concurrent automatic brachial BP measurement (Schiller AG, Baar, Switzerland) and 12-lead ECG recording. The cuff used for measurement was adjusted to the individual’s arm circumference. The first BP measurement was performed on the right arm in a sitting position on the ergometer after a resting period of 5 min (resting BP). The participants were instructed to let their right arm hang loosely during BP measurements, when possible. The exercise test protocol of the athletes started with a load level of 100 W after a 2-min warm-up period that was conducted with 50 W. Controls started with 50 W after a warm-up period conducted with 25 W. Loads were increased by 50 W in athletes and 25 W in controls every 2 min until exhaustion, which was defined as the participant’s inability to maintain the load for 2 min. If participants could not complete the last 2-min stage, the individual maximum workload was calculated depending on the percentage duration of the last stage. Further, the rating of perceived exertion (RPE, Borg) was evaluated every 2 minutes, but not used as a termination criterion. Next, the load was decreased to 25 W for 2 min of active recovery that was followed by a 3-min cool-down period at rest. The test concluded with a final ECG recording and brachial BP measurement. BP was measured at every stage during test and recovery periods, including at the maximum workload. Each BP measurement was recorded automatically with the corresponding time, heart rate, and workload. The calculated maximum heart rate was determined with the formula validated for cycling ergometries ((208–(age*0.7)). However, the predicted maximum heart rate was not used as a termination criterion.

Increases in systolic and diastolic BP were calculated from peak and baseline (resting) values. Pulse pressure was calculated as SBP–DBP at rest and during exercise. In addition, mean BP was determined as: DBP+(SBP–DBP)/3. MET values were estimated using the following formula validated for cycling ergometers: MET= (((Watt*1.8*6.12)/kg))+7)/3.5 18 . The ΔSBP was calculated as (maximum SBP–resting SBP) and was indexed by the increase in MET from rest (ΔMET calculated as peak MET–1) to obtain the SBP/MET slope 6 . The peak SBP/W ratio was determined as peak SBP/peak workload in W 21 . The SBP/W slope was calculated as the ratio of the difference in SBP from the first to the last BP measurement during exercise over the difference in workload in W between these two measures (last SBP–first SBP)/(last W–first W) 21 .

Non-invasive assessment of peripheral and central blood pressure and pulse pressure waveforms

We used the non-invasive vascassist2 device (isymed GmbH, Butzbach, Germany) to acquire pulse pressure waveforms by means of oscillometry. The device uses a validated model 14 24 of the arterial tree, which replicates an individual’s acquired pulse pressure waves. The vascular evaluation was carried out before exercise testing in a room with a comfortable and stable temperature of 22 °C and a lack of external stress influences. After a 15-min rest period, measurements were performed in a supine position using four conventional cuffs adapted to the upper arm and forearm circumferences of the participants. Both radial and brachial pulse pressure waves were acquired simultaneously on both arms with step-by-step deflation of the cuffs and analyzed. Brachial and radial BP, central blood pressure (CBP), aortic pulse wave velocity (PWV), augmentation index at a heart rate of 75 bpm (Aix@75), resistance index (R), total vascular resistance, stroke volume, cardiac output, and ejection duration were calculated.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analyses were carried out on all study variables for the total sample and separated by athletes and controls. All data are presented as mean±standard deviation (SD). The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to determine normal distribution. Between-group comparisons were made using independent sample t tests. Bivariate relations were analyzed using the Spearman correlation coefficient. Pearson’s product-moment correlation coefficient was used to determine linear correlations between vascular functional parameters and exercise test results. Statistical significance was set at p <0.05 (two-tailed) for all measurements. Relationships between wiBPR and vascular functional parameters were explored using bivariate correlation and multiple linear regression analysis. All statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS statistical software (IBM SPSS Statistics for Macintosh, Version 25.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Cohort characteristics

A total of 125 male participants, 95 athletes and 30 healthy, age-matched controls, were included in the study. Athletes were taller and heavier and displayed a greater body surface area than controls ( Table 1 ); however, age (p=0.292) and body mass index were not different between groups (p=0.206). The mean resting heart rate was lower in athletes than in controls (57±10 vs. 70±14 bpm, p<0.001). Further clinical characteristics, anthropometric data, and specific training data are displayed in Table 1 . As expected, we found a significant correlation of age with history of professional training (r= 0.956, p< 0.001) in athletes.

Table 1 Clinical characteristics of athletes (n=95) and controls (n=30)

| Athletes n=95 | Controls n=30 | p value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Age (years) | 25.6 | 5 | 26.2 | 4.4 | 0.292 |

| Height (cm) | 188.5 | 7.2 | 183.8 | 6.2 | 0.002 |

| Weight (kg) | 91.5 | 10.7 | 85.1 | 8.3 | 0.003 |

| Body mass index (kg/m 2 ) | 25.7 | 2 | 25.17 | 1.9 | 0.206 |

| Body surface area (m 2 ) | 2.18 | 0.16 | 2.08 | 0.12 | 0.001 |

| Training history (years) | 9.85 | 4.95 | 0.03 | 0.18 | <0.001 |

| Training per week (hours) | 17.45 | 3.1 | 0.5 | 0.2 | <0.001 |

Blood pressure and vascular function at rest

The mean resting brachial SBP and the mean brachial BP was lower in athletes than in controls. None of the participants displayed a BP >140/90 mmHg. Athletes had a significantly lower diastolic CBP, mean CBP and PWV compared with controls, whereas systolic CBP, Aix@75, resistance index (R), and total vascular resistance were not different between the groups. In contrast, the central pulse pressure was higher in athletes than in controls. Detailed data are presented in Table 2 .

Table 2 Results of vascular evaluation in athletes (n=95) and controls (n=30)

| Athletes n=95 | Controls n=30 | p value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Brachial systolic BP (mmHg) | 123 | 10.2 | 129 | 11.5 | 0.013 |

| Brachial diastolic BP (mmHg) | 76 | 7 | 78 | 8.5 | 0.196 |

| Mean brachial BP (mmHg) | 91.8 | 6.8 | 95.1 | 8 | 0.053 |

| Pulse pressure at rest (mmHg) | 46.8 | 10 | 50.4 | 11.3 | 0.098 |

| Heart rate at rest (bpm) | 57.2 | 10.3 | 70.1 | 13.6 | <0.001 |

| Mean aortic blood pressure (mmHg) | 76 | 10 | 82 | 9.8 | 0.005 |

| Central systolic BP (mmHg) | 99 | 8 | 102 | 9.3 | 0.052 |

| Central diastolic BP (mmHg) | 63 | 9.7 | 69 | 9.3 | 0.003 |

| Central pulse pressure (mmHg) | 38 | 6.6 | 34 | 6.4 | 0.019 |

| Aortic pulse wave velocity (m/s) | 6.4 | 0.92 | 7.2 | 1.5 | 0.001 |

| Augmentation index @75 bpm (%) | −18.6 | 10 | − 16 | 10 | 0.38 |

| Resistance index | 16.4 | 6.3 | 17.7 | 7.4 | 0.346 |

| Total vascular resistance (dyn*sec/cm 5 ) | 1336 | 298 | 1267 | 333 | 0.294 |

Heart rate and blood pressure response to exercise

The test duration between athletes and controls was not different (1060±100 vs. 1005±150 sec, p=0.102). All participants achieved a maximum heart rate above the threshold of 85% of the individual calculated maximum heart rate with significant differences between the two groups (athletes 94.4±5.1% vs. controls 98.6±4.7%, p<0.001). In consequence, maximum heart rate during the exhaustive exercise test was significantly lower in athletes than in controls (179.4±9.8 vs. 187.1±9.9 bpm, p<0.001). However, the rating of perceived exertion was not different between the groups (18.5±1.1 vs. 19.2±0.9 Borg scale, p=0.065).

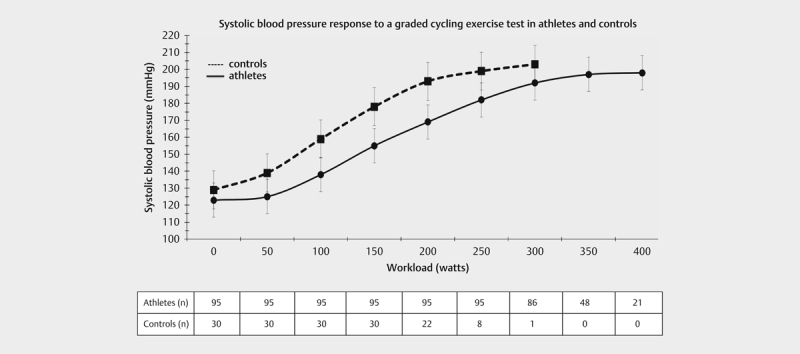

The heart rate, SBP, DBP, mean brachial BP, and pulse pressure were significantly lower in athletes compared to controls (<0.001) at 100, 150 and 200 W workload. All controls completed the 150 W stage, 22 (66%) accomplished the 200 W stage, 8 (26%) the 250 W stage, and 1 (3%) achieved the 300 W stage. All athletes (95) completed the 250 W stage, 86 (82%) the 300 W stage, 48 (46%) the 350 W stage, 21 (20%) the 400 W stage, and 5 athletes (5%) accomplished more than the 450 W stage, respectively.

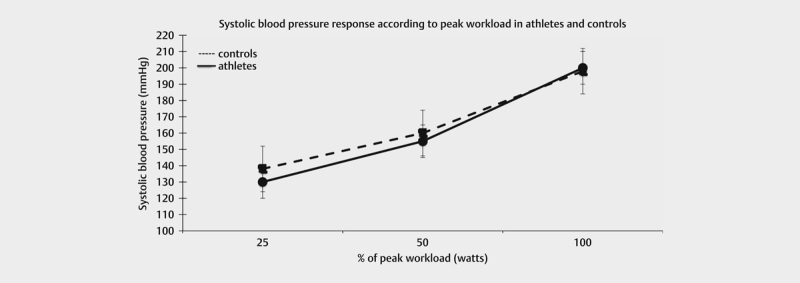

Despite the differences throughout the stages of the graded exercise test, the maximum SBP (200±20 vs. 197±19 mmHg, p=0.358), maximum DBP (84.7±7.1 vs. 86.4±10.1 mmHg, p=0.391), mean brachial BP (123.5±9 vs. 123.3±11.6 mmHg, p= 0.893) and maximum pulse pressure (115.4±19.8 vs. 110.6±13.6 mmHg, p=0.211) were not different between athletes and controls at the individual peak exercise. ΔSBP and Δpulse pressure were higher in athletes, but ΔDBP and Δmean brachial BP were not different between groups. The complete data set is presented in Table 3 . In addition, the blood pressure responses at each stage are depicted in Figure 1 . Further, Figure 2 shows the SBP according to the achieved maximum workload.

Table 3 Results of vascular evaluation and exercise testing in athletes (n=95) and controls (n=30).

| Athletes n=95 | Controls n=30 | p value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Rest | |||||

| Brachial systolic BP (mmHg) | 123 | 10.2 | 129 | 11.5 | 0.013 |

| Brachial diastolic BP (mmHg) | 76 | 7 | 78 | 8.5 | 0.196 |

| Mean brachial BP (mmHg) | 91.8 | 6.8 | 95.1 | 8 | 0.053 |

| Pulse pressure at rest (mmHg) | 46.8 | 9.9 | 50.4 | 11.3 | 0.098 |

| Heart rate at rest (bpm) | 57.2 | 10.3 | 70.1 | 13.6 | <0.001 |

| 100 Watts | |||||

| Brachial systolic BP (mmHg) | 138 | 14.1 | 159 | 17.6 | <0.001 |

| Brachial diastolic BP (mmHg) | 76 | 7.3 | 80.8 | 7.7 | 0.005 |

| Mean brachial BP (mmHg) | 97.2 | 7.4 | 107.2 | 9.5 | <0.001 |

| Pulse pressure (mmHg) | 62.6 | 14.6 | 79.1 | 14.7 | <0.001 |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 105.2 | 11.8 | 129.4 | 16.5 | <0.001 |

| 150 Watts | |||||

| Brachial systolic BP (mmHg) | 155.4 | 15.6 | 178.4 | 17.5 | <0.001 |

| Brachial diastolic BP (mmHg) | 77.5 | 8.7 | 83.4 | 7 | <0.001 |

| Mean brachial BP (mmHg) | 103.5 | 9.3 | 115.1 | 9.1 | <0.001 |

| Pulse pressure (mmHg) | 77.9 | 14.1 | 95 | 14.7 | <0.001 |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 123.8 | 13.2 | 156.2 | 18.6 | <0.001 |

| 200 Watts | |||||

| Participants | 95 (100%) | 22 (66%) | |||

| Brachial systolic BP (mmHg) | 168.7 | 17.9 | 193 | 19.3 | <0.001 |

| Brachial diastolic BP (mmHg) | 80.6 | 11.6 | 88.3 | 9.3 | <0.001 |

| Mean brachial BP (mmHg) | 110 | 10.8 | 122.3 | 10.8 | <0.001 |

| Pulse pressure (mmHg) | 89.3 | 16.2 | 102.7 | 13.9 | <0.001 |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 143.7 | 13.8 | 177.1 | 17.7 | <0.001 |

| 250 Watts | |||||

| Participants | 95 (100%) | 8 (26%) | |||

| Brachial systolic BP (mmHg) | 181.6 | 18.8 | 195.1 | 12.4 | 0.012 |

| Brachial diastolic BP (mmHg) | 83.8 | 11.4 | 85.7 | 7.3 | 0.716 |

| Mean brachial BP (mmHg) | 116.4 | 12.8 | 123.5 | 14.1 | 0.024 |

| Pulse pressure (mmHg) | 97.1 | 14.3 | 112.8 | 12.1 | 0.001 |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 162.1 | 15.3 | 183.6 | 10.9 | <0.001 |

| Peak exercise | |||||

| Time (sec) | 1060 | 100 | 1005 | 150 | 0.102 |

| Rating of perceived exertion (Borg scale) | 18.5 | 1.1 | 19.2 | 0.9 | 0.065 |

| Maximum heart rate (bpm) | 179.4 | 9.8 | 187.1 | 9.9 | <0.001 |

| Max. heart rate (% of calculated max. heart rate) | 94.4 | 5.1 | 98.6 | 4.7 | <0.001 |

| Absolute workload (watts) | 339.2 | 64 | 211 | 35.2 | <0.001 |

| Relative workload (watts/kg) | 3.73 | 0.8 | 2.5 | 0.44 | <0.001 |

| Peak energy expenditure (MET) | 13.9 | 2.5 | 9.9 | 1.4 | <0.001 |

| Maximum systolic brachial BP (mmHg) | 200.4 | 20.1 | 197 | 18.1 | 0.358 |

| Maximum diastolic brachial BP (mmHg) | 84.7 | 7.1 | 86.4 | 10.1 | 0.391 |

| Mean brachial BP (mmHg) | 123.5 | 9 | 123.3 | 11.6 | 0.893 |

| Maximum pulse pressure (mmHg) | 115.4 | 19.8 | 110.6 | 13.6 | 0.211 |

| Changes from baseline | |||||

| Δ systolic brachial BP (mmHg) | 77 | 20 | 68 | 14 | 0.004 |

| Δ diastolic brachial BP (mmHg) | 8.8 | 9.3 | 7.5 | 6.5 | 0.395 |

| Δ mean brachial BP (mmHg) | 31.7 | 10.2 | 28.2 | 7.8 | 0.09 |

| Δ pulse pressure (mmHg) | 68.6 | 18.4 | 60.1 | 12.5 | 0.021 |

| Workload- indexed blood pressure response | |||||

| SBP/MET slope (mmHg/MET) | 6.20 | 1.8 | 7.85 | 1.8 | <0.001 |

| SBP/Watt slope (mmHg/Watt) | 0.34 | 0.13 | 0.44 | 0.12 | <0.001 |

| Peak SBP/Watt- ratio (mmHg/Watt) | 0.61 | 0.12 | 0.95 | 0.17 | <0.001 |

Fig. 1.

Systolic blood pressure response to a graded cycling exercise test in athletes and controls.

Fig. 2.

Systolic blood pressure response according to peak workload in athletes and controls.

Maximum SBP was positively correlated with resting SBP (r=0.241, p=0.019) and maximum DBP (r=0.234, p=–0.022). In addition, resting SBP was negatively associated with R (r=–0.289, p=0.005).

Workload-indexed blood pressure responses

Athletes achieved a significantly higher absolute workload than controls with a correspondingly higher relative workload and MET. All markers of a workload-adjusted BPR were significantly lower in athletes than in controls: SBP/MET slope (6.2±1.8 vs. 7.85±1.8 mmHg/MET, p<0.001); SBP/W slope (0.35±0.13 vs. 0.44±0.12 mmHg/W, p<0.001) and the peak SBP/W ratio (0.61±0.12 vs. 0.95±0.17 mmHg/W, p<0.001) ( Table 3 ). The respective percentiles for the BP increase and the wiBPR for athletes are displayed in Table 4 .

Table 4 Systolic blood pressure response to exercise in athletes (n=95).

| Rest | 100 W | 150 W | 200 W | 250 W | SBP/MET slope | SBP/W slope | Peak SBP/W-ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (mmHg) | (mmHg) | (mmHg) | (mmHg) | (mmHg) | (mmHg/MET) | (mmHg/W) | ||

| 10th percentile | 110 | 122 | 136 | 143 | 158 | 3.88 | 0.19 | 0.46 |

| 20th percentile | 113 | 127 | 143 | 152 | 165 | 4.56 | 0.24 | 0.52 |

| 30th percentile | 117 | 132 | 149 | 161 | 170 | 5.11 | 0.275 | 0.55 |

| 40th percentile | 120 | 135 | 152 | 165 | 174 | 5.57 | 0.29 | 0.57 |

| 50th percentile | 124 | 140 | 156 | 168 | 180 | 5.95 | 0.32 | 0.59 |

| 60th percentile | 125 | 143 | 160 | 174 | 187 | 6.47 | 0.35 | 0.61 |

| 70th percentile | 128 | 147 | 165 | 180 | 191 | 7.12 | 0.385 | 0.65 |

| 80th percentile | 132 | 152 | 169 | 184 | 198 | 8.0 | 0.44 | 0.72 |

| 90th percentile | 136 | 159 | 175 | 190 | 206 | 8.8 | 0.49 | 0.77 |

All vascular functional parameters, measured at rest, were not significantly correlated to SBP/MET slope, the peak SBP/W ratio, or the SBP/W slope in either athletes or controls.

Regression analyses of the influence of the hemodynamic data of athletes and controls on different markers of workload-indexed blood pressure response

We performed multivariate regression analyses to explore possible linear associations across the vascular functional parameters measured at rest with the workload- indexed markers of BPR. We used brachial systolic BP, brachial diastolic BP, central systolic and diastolic BP, mean central BP, central pulse pressure, PWV, Aix@75 bpm, R and total vascular resistance as predictors of the regression model and, separately, the SBP/MET slope, the peak SBP/W ratio, and SBP/W slope as continuous dependent variables in both athletes and controls. All evaluated regression models were unable to predict the markers of workload- indexed BPR in both groups and neither of the evaluated vascular functional parameters at rest were found to be independent determinants of the workload-indexed BPR.

Discussion

The present study represents the first analysis of vascular function and the newly introduced workload-adjusted markers of BPR, such as SBP/MET slope, SBP/W slope, and peak SBP/W ratio, to a maximum exercise test in professional athletes and sedentary controls.

Our main findings are that 1) athletes displayed a significantly lower wiBPR than did sedentary controls despite a higher achieved absolute and relative workload; 2) all markers of wiBPR were markedly lower in athletes, although the absolute values of maximum SBP were not different between athletes and controls; 3) further, despite a lower PWV and lower mean CBP at rest, all other vascular markers measured at rest, including total vascular resistance and resistance index, were not different between athletes and sedentary controls; 4) none of the measured markers of vascular function were able to predict the wiBPR in either athletes or controls; 5) in athletes, the SBP/Watt and the SBP/MET slope, but not the peak SBP/W ratio, were comparable to the recently published reference values for bicycle ergometers.

Our study provides the first comparison of the newly introduced markers of workload-indexed BPR to exercise in male professional athletes and age-matched controls.Recently, Hedman et al. 21 reported age- and sex-specific reference equations for workload-indexed systolic BPR during bicycle ergometry for the general population. The SBP/W slope, reflecting the increase of SBP per W increment and thus the steepness of SBP in relation to workload, was introduced and suggested to deliver additional data for risk classification.

The BPR to exercise in men is characterized by an increase in cardiac output and by an increase in total peripheral resistance 25 and therefore less influenced by fitness levels. Hence, the values of the SBP/W slope in our male athletes were comparable (0.34±0.12 vs. 0.33±0.11 mmHg/W) to the proposed reference values of the general population, whereas the SBP/W slope of our healthy control group (0.44±0.12 mmHg/W) was markedly higher 21 .

In contrast to the aforementioned, the absolute values of the peak SBP/W ratio in our cohort of professional athletes were lower compared to the published reference values 21 (0.61±0.12 vs. 0.73±0.11 mmHg/W), whereas the control group exceeded the normative 95th percentile (0.95±0.17 mmHg/W) 21 . Given that our athletes had significantly greater cardiorespiratory fitness (CRF) than the participants of the Hedman study, it is tempting to speculate that CRF affects the peak SBP/W ratio. Hence, the peak SBP/W ratio of athletes might be lower compared to that of controls, as athletes usually achieve higher workloads. In consequence, these results raise the question whether athletes might need different thresholds for the peak SBP/Watt ratio.

The ACSM recommendations 18 propose a normative SBP/MET slope of 10 mmHg/MET. However, in our cohort, the mean SBP/MET slope was 6.2 mmHg/MET for athletes and 7.85 mmHg/MET for controls. In other observations a median of 6.4 mmHg/MET in a normal population 6 and 5.4 mmHg/MET in an athletic population 19 were reported. Of note and in line with the aforementioned, the 95 th percentile of the SBP/MET slope in our examined athletes was 9.42 mmHg/MET and 10.3 mmHg/MET in our control group, respectively 18 . In conclusion, our findings clearly indicate that the ACSM threshold of 10 mmHg/MET 18 represents an upper limit and not an average normal increase.

The healthy, but sedentary control group of our study exceeded the normative values of all measured markers of wiBPR, which suggests an increased cardiovascular risk. Therefore, preventive interventions to avoid the development of arterial hypertension and cardiovascular disease should be established in this group.

Taken together, our data emphasize the need to use wiBPR instead of absolute values, as the maximum SBP was not different between athletes and controls. Reliable and validated reference values for athletes should be established to define an exaggerated BPR in these cohorts in order to identify athletes at risk of developing arterial hypertension.

So far, our studies delivered reference values for the SBP/MET slope in an athletic population of >200 professional male athletes in total 19 . These results are in line with the proposed normative values that were derived from 285 healthy males in this age cohort 21 . To this end, the aforementioned data concerning the SBP/MET slope are promising 6 .

Hedman et al. 21 and others 26 hypothesized that total peripheral vascular resistance contributes to BPR and physical performance. Hence, our previous study 20 revealed the impact of the resistance index (R) on physical performance in athletes. However, in the current study, neither R nor global vascular resistance at rest was different between athletes and controls, and consequently they were not able to predict the wiBPR in athletes. Moreover, measuring of PWV was proposed to provide additional information for cardiovascular risk classification as it predicted an exaggerated BPR in normotensive individuals 17 . The PWV of 6.4 m/s measured in our athletes is in line with other studies 20 27 and meta-analyses 28 . Athletes performing predominantly aerobic exercise are likely to display a lower PWV than sedentary individuals 28 29 , represented by our control group. Further, aerobic exercise training was shown to reverse age-related aortic stiffness 30 . Thus, in our study, all vascular functional parameters were not able to predict the wiBPR in both groups. The difference of our findings to the aforementioned study 17 might be explained with our investigated study cohort of professional athletes, who displayed a low PWV. Further, Haarala et al. 17 did not present their data separately for males and females, which limits comparison to our own results.

Hence, it may be speculated that resistance index and global vascular resistance differ during exercise conditions and lead to the detected difference in the wiBPR with athletes displaying a higher arterial vasodilator reserve. Unfortunately, vascular resistance could not be measured during exercise to substantiate this hypothesis. Taken together, these results highlight the problems inherent with the use of non-invasive devices that evaluate vascular function via oscillometry 13 . These validated methods deliver reliable results at rest, but owing to the measurement technique, not during an exhaustive exercise test 13 .

As total vascular resistance at rest and maximum SBP were not different between athletes and controls, our data indicate the importance of vascular function and total vascular resistance during exercise for the BPR to exercise.

Limitations and strengths

Our study has a few limitations. The number of participants limited its power to uncover potential correlations between the wiBPR parameters measured and markers of cardiac and vascular function other than CBP, PWV, total vascular resistance, and brachial BP. In addition, the number of included athletes precludes the determination of reference values. The focus on professional male handball players limits extrapolation of the results to other sport disciplines and to female athletes. Further, the different ramp grading of the exercise testing between athletes and controls may have affected our results.

However, we did include a homogeneous cohort of experienced elite athletes and controls of the same age without cardiovascular disease and free of medication. Further, the rigid design of measuring vascular function and accomplishing an exhaustive and standardized exercise test in both groups must be mentioned, which strengthens our analysis.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our findings may aid clinicians and exercise physiologists in interpreting the BPR to exercise and provide a basis for future research on the prognostic impact of exercise BPR. Especially the SBP/MET slope might already be used in male athletes to determine wiBPR to exercise 6 19 . Vascular functional parameters were not correlated to the wiBPR in either athletes or controls despite their potential to detect occult cardiovascular impairment.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Keller K, Stelzer K, Ostad M A et al. Impact of exaggerated blood pressure response in normotensive individuals on future hypertension and prognosis: Systematic review according to PRISMA guideline. Adv Med Sci. 2017;62:317–329. doi: 10.1016/j.advms.2016.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Percuku L, Bajraktari G, Jashari H et al. The exaggerated systolic hypertensive response to exercise associates cardiovascular events: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pol Arch Intern Med. 2019;129:855–863. doi: 10.20452/pamw.15007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caselli S, Serdoz A, Mango F et al. High blood pressure response to exercise predicts future development of hypertension in young athletes. Eur Heart J. 2019;40:62–68. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Niebauer J, Borjesson M, Carre F et al. Brief recommendations for participation in competitive sports of athletes with arterial hypertension: Summary of a Position Statement from the Sports Cardiology Section of the European Association of Preventive Cardiology (EAPC) Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2019;26:1549–1555. doi: 10.1177/2047487319852807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mont L, Pelliccia A, Sharma S et al. Pre-participation cardiovascular evaluation for athletic participants to prevent sudden death: Position paper from the EHRA and the EACPR, branches of the ESC. Endorsed by APHRS, HRS, and SOLAECE. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2017;24:41–69. doi: 10.1177/2047487316676042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hedman K, Cauwenberghs N, Christle J W et al. Workload-indexed blood pressure response is superior to peak systolic blood pressure in predicting all-cause mortality. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2019;27:978–987. doi: 10.1177/2047487319877268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hedberg P, Ohrvik J, Lonnberg I et al. Augmented blood pressure response to exercise is associated with improved long-term survival in older people. Heart. 2009;95:1072–1078. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2008.162172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim D, Ha J W.Hypertensive response to exercise: mechanisms and clinical implication. Clin Hypertens 20162217doi:10.1186/s40885-016-0052-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schultz M G, Otahal P, Picone D S et al. Clinical relevance of exaggerated exercise blood pressure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66:1843–1845. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sabbahi A, Arena R, Kaminsky L A et al. Peak blood pressure responses during maximum cardiopulmonary exercise testing: reference standards from FRIEND (Fitness Registry and the Importance of Exercise: A National Database) Hypertension. 2018;71:229–236. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.117.10116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W et al. 2018 ESC/ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:3021–3104. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Currie K D, Floras J S, La Gerche A et al. Exercise blood pressure guidelines: time to re-evaluate what is normal and exaggerated? Sports Med. 2018;48:1763–1771. doi: 10.1007/s40279-018-0900-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miyata M.Noninvasive assessment of arterial stiffness using oscillometric methods: baPWV, CAVI, API, and AVI. J Atheroscler Thromb 2018. doi:10.5551/jat.ED098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Trinkmann F, Benck U, Halder J Automated non-invasive central blood pressure measurements by oscillometric radial pulse wave analysis – results of the MEASURE-cBP validation studies. Am J Hypertens. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Miyai N, Shiozaki M, Terada K Exaggerated blood pressure response to exercise is associated with subclinical vascular impairment in healthy normotensive individuals. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Thanassoulis G, Lyass A, Benjamin E J et al. Relations of exercise blood pressure response to cardiovascular risk factors and vascular function in the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2012;125:2836–2843. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.063933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haarala A, Kahonen E, Koivistoinen T Pulse wave velocity is related to exercise blood pressure response in young adults. The Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns Study. Blood Press. 2020. pp. 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Thompson P D, Arena R, Riebe D et al. ACSM's new preparticipation health screening recommendations from ACSM's guidelines for exercise testing and prescription, ninth edition. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2013;12:215–217. doi: 10.1249/JSR.0b013e31829a68cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bauer P, Kraushaar L, Dorr O Workload-indexed blood pressure response to a maximum exercise test among professional indoor athletes. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2020. p. 2.047487320922043E15. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Bauer P, Kraushaar L, Most A et al. Impact of vascular function on maximum power output in elite handball athletes. Res Q Exerc Sport. 2019;90:600–608. doi: 10.1080/02701367.2019.1639602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hedman K, Lindow T, Elmberg V Age- and gender-specific upper limits and reference equations for workload-indexed systolic blood pressure response during bicycle ergometry. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2020. p. 2.047487320909667E15. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Harriss D J, MacSween A, Atkinson G.Ethical standards in sport and exercise science research: 2020 update Int J Sports Med 201940813–817.doi:10.1055/a-1015-3123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Du Bois D, Du Bois E F.A formula to estimate the approximate surface area if height and weight be known. 1916 Nutrition 19895303–311.discussion 312–303 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schumacher G, Kaden J J, Trinkmann F.Multiple coupled resonances in the human vascular tree: Refining the Westerhof model of the arterial system J Appl Physiol (1985) 2018124131–139.doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00405.2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Samora M, Incognito A V, Vianna L C.Sex differences in blood pressure regulation during ischemic isometric exercise: The role of the beta-adrenergic receptors J Appl Physiol (1985) 2019127408–414.doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00270.2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Green D J, Hopman M T, Padilla J et al. Vascular adaptation to exercise in humans: role of hemodynamic stimuli. Physiol Rev. 2017;97:495–528. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00014.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vlachopoulos C, Kardara D, Anastasakis A et al. Arterial stiffness and wave reflections in marathon runners. Am J Hypertens. 2010;23:974–979. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2010.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ashor A W, Lara J, Siervo M et al. Effects of exercise modalities on arterial stiffness and wave reflection: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One. 2014;9:e110034. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0110034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sardeli A V, Gaspari A F, Chacon-Mikahil M P. Acute, short-, and long-term effects of different types of exercise in central arterial stiffness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2018;58:923–932. doi: 10.23736/S0022-4707.17.07486-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bhuva A N, D'Silva A, Torlasco C et al. Training for a first-time marathon reverses age-related aortic stiffening. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:60–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.10.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material