Abstract

Economic insecurity is a risk factor for intimate partner homicide (IPH). The Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) is the largest cash transfer programme to low-income working families in the USA. We hypothesised that EITCs could provide financial means for potential IPH victims to exit abusive relationships and establish self-sufficiency. We conducted a national, quasiexperimental study of state EITCs and IPH rates in 1990–2016 using a difference-in-differences approach. The national rate of IPH decreased from 1.9 per 100 000 adult women in 1990 to 1.3 per 100 000 in 2016. We found no statistically significant association between state EITC generosity and IPH rates (coefficient indicating change in IPH rates per 100 000 adult female years for additional 10% in amount of state EITC, measured as the percentage of federal EITC: 0.02, 95% CI −0.03 to 0.08). Financial control associated with abuse and current EITC eligibility rules may prevent potential IPH victims from accessing the EITC.

INTRODUCTION

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is an underappreciated public health burden, affecting 43 million adults in the USA.1 Intimate partner homicide (IPH), the most extreme form of IPV, is often an escalation of IPV and accounts for over half (55.3%) of female homicides in the USA.2

Poverty plays an outsized role in IPV, as both a cause and a consequence.3 It is estimated that 20%–30% of women receiving welfare currently experience abuse, with 50%–60% having lifetime histories of abuse.4 Economic control is a common feature in abusive relationships, making it difficult for victims of all income levels to maintain employment, escape abusers and establish safety and self-sufficiency.5

The Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) is the largest cash transfer programme to low-income working families in the USA.6 The EITC programme issues a tax credit to low-earning workers based on pretax earnings, marital status and number of dependents. Many states augment the federal EITC with state EITCs, usually set as a fixed percentage of the federal EITC.

The EITC has been demonstrated to reduce poverty, increase employment and improve maternal and child health.7 There are multiple mechanisms through which the EITC may exert its effect on health outcomes including increased family income, labour force participation and downstream effects on health determinants (eg, stress). Many of these determinants, such as stress and dysfunctional coping behaviours, are risk factors for IPV.8 Moreover, as lack of financial resources is the most frequently cited barrier for women to leave abusive relationships, federal and state EITCs could provide financial means to leave abusive partners.3 However, the current EITC eligibility rules—specifically, that married individuals cannot receive EITCs when filing separate returns—and financial control associated with abuse may hinder the programme’s use for this purpose. We hypothesised that increased generosity in state EITCs would be associated with a reduction in IPH rates.

METHODS

Measures

Our outcome was state-year estimates of IPH reported in Supplementary Homicide Reports (SHRs). SHRs are voluntarily submitted by law enforcement agencies to the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and provide the most comprehensive data on homicide victim–offender relationship in the USA. However, not all jurisdictions report their data each year, and many records are missing victim–offender relationship, largely due to an increasing number of unsolved homicides. To mitigate these limitations, we used a multiply-imputed SHR data set that accounts for under-reporting of homicides and missing data on offender characteristics that has been used in other studies.9,10 We applied weights to produce state-level estimates of IPH compatible with the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reporting Program.11 The dependent variable was the annual rate of IPH per 100 000 state adult female population for the years 1990–2016. IPH victims included females aged 18 years or over identified as spouses, ex-spouses, girl-friends or homosexual partners of the offender.

Our main exposure was generosity of refundable state EITCs, measured by percentage of federal EITC.12 Prior research has treated refundable and non-refundable EITCs differently because non-refundable EITCs only reduce tax liability and are far less beneficial to the eligible population, particularly to the lowest earnings individuals, who often have no tax liability.13 For example, more than 85% of federal EITC benefits are provided as a refundable credit rather than a reduction in tax liability.14 In addition, non-refundable EITCs have no association or a much weaker association than do refundable EITCs with health outcomes.7,15 Therefore, in our main analysis of generosity, we compared states with refundable EITCs with those with non-refundable or no EITC.

Of the 1350 state-years for the 50 states in years 1990–2016, 20 state-years (1%) were missing IPH data and dropped. Between 1990 and 2016, 15 states introduced refundable EITC and 19 states increased the amount of their state EITC at least once. Adjusted for inflation, the maximum federal EITC credit for a family with three dependents was $1750 in 1990 and $6269 in 2016.16

Statistical analysis

Using a difference-in-differences approach, we estimated the association between state EITC generosity and rates of IPH per 100 000 adult female population. In addition to state and year fixed effects, and guided by prior literature,17,18 the models adjusted for factors potentially associated with EITC policy and IPH rates that varied differentially by state over time. These include non-familial homicide rates (using multiply-imputed SHR), estimates of firearm ownership (RAND Corporation) and per capita alcohol consumption (National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism). We also controlled for measures of state economic and policy context: gross state domestic product in $100 000 s, maximum Temporary Assistance for Needy Families benefit in $1000 s and state minimum wage (dollars per hour).16 We controlled for state demographic characteristics with the proportion of females to males aged 25 years or over with college or higher educational attainment, the population percentage of uninsured, per cent black, per cent divorced and per cent married (all from US Census). All demographic covariates were linearly interpolated between decennial US Censuses from 1990 to 2010 and from the US Census’ American Community Survey for years 2011–2016. All monetary variables were adjusted for inflation to 2016 dollars.

We used linear regression models with state-fixed and year-fixed effects to assess the effects of state-level changes in EITC generosity on IPH rates. We performed three sensitivity analyses with the same regression approach: in sensitivity analysis 1, we evaluated changes in state EITC generosity (% of federal EITC) with no distinction between refundable and non-refundable EITCs. In sensitivity analysis 2, we included a binary variable for refundability and an interaction between that variable and the continuous variable for EITC generosity. In sensitivity analysis 3, we assessed lagged effects of EITCs by 1 year using the main model. We assessed for parallel trends in IPH rates between states that ever and never implemented refundable EITCs using its interaction with time during pre-EITC years.

All analyses were conducted in Stata v.15.1.

RESULTS

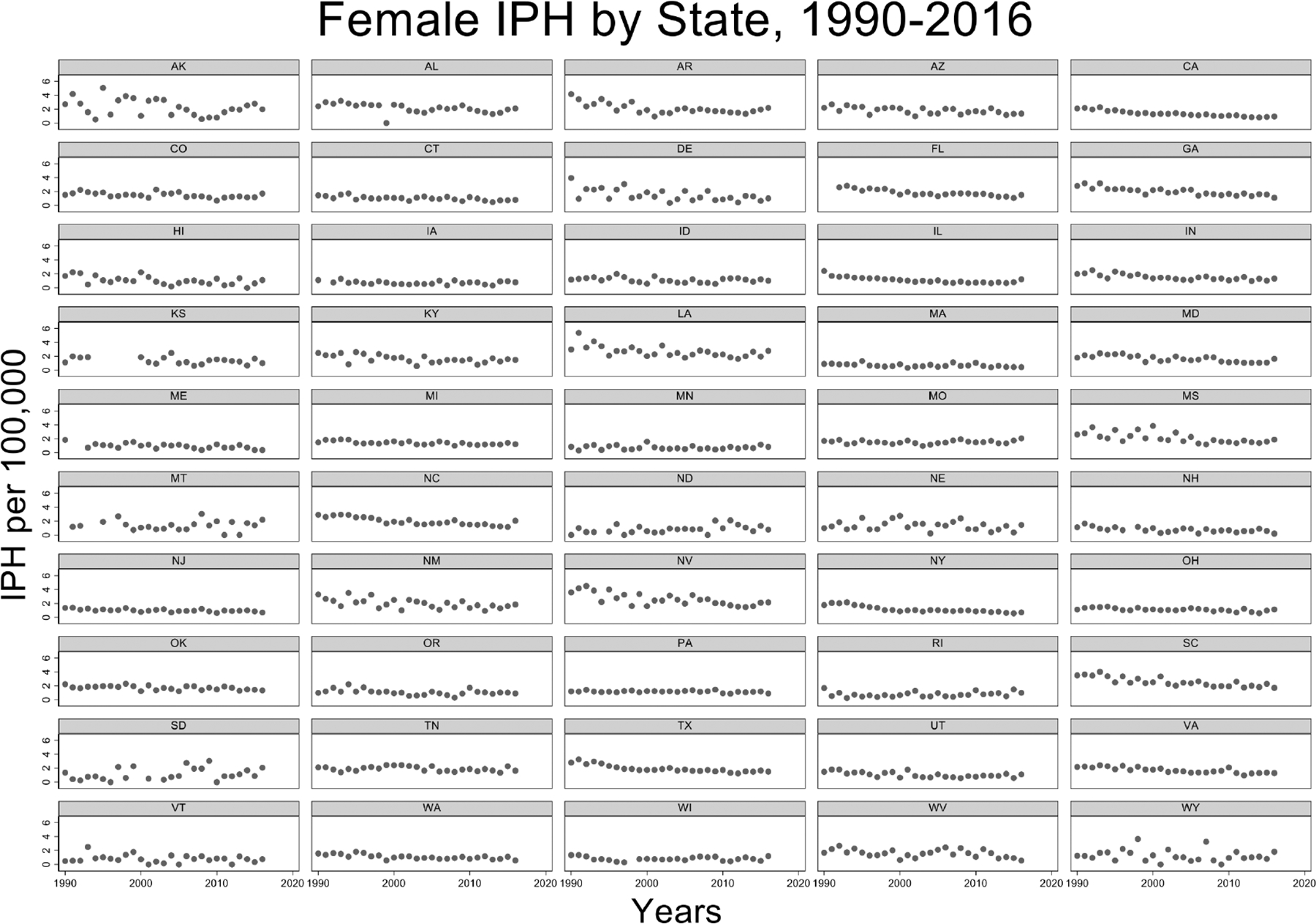

The national average rate of IPH decreased slightly from 1.9 per 100 000 adult females in 1990 to 1.3 per 100 000 in 2016, with a range of 0 in some state-years (n=14) to 5.4 per 100 000 in Louisiana (1991). The state-years with the highest rates of IPH were in Alaska, Arkansas, Louisiana, Nevada and South Carolina (figure 1). Comparing states without EITC to those which later enacted EITC, we found support for the parallel trends assumption (p for interaction=0.128).

Figure 1.

Intimate partner homicides (IPH) of adult females per 100 000 by state, 1990–2016.

In the main analysis, there was no statistically significant association between state refundable EITC generosity and IPH rates (coefficient indicating change in IPH rates per 100 000 adult female-years for additional 10% state EITC, as measured by percentage of federal EITC: 0.02, 95% CI −0.03 to 0.08) (table 1). Results of sensitivity analyses supported the findings of the main analysis: In sensitivity analysis 1, we found no significant association between EITC generosity (refundable or non-refundable) and IPH rates. In sensitivity analysis 2, we found no significant interaction between generosity and refundability status in their association with IPH rates, with generosity in neither refundable nor non-refundable EITCs significantly associated with IPH rates. In sensitivity analysis 3, we found no significant association between lagged EITC and IPH rates (table 1).

Table 1.

Association between state Earned Income Tax Credit generosity and intimate partner homicide in all US states, 1990–2016

| Coef*† (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|

| Main model | 0.02 (−0.03 to 0.08) | 0.416 |

| Sensitivity analysis 1 | −0.02 (−0.07 to 0.03) | 0.429 |

| Sensitivity analysis 2 | −0.02 (−0.07 to 0.04) | 0.560 |

| Sensitivity analysis 3 | 0.04 (−0.03 to 0.11) | 0.234 |

Sensitivity analysis 1: EITC generosity, including both refundable and non-refundable without any distinction between them; sensitivity analysis 2: binary refundability status, continuous EITC generosity and their interaction (the coefficient presented pertains to refundable EITC as the main focus of this study); sensitivity analysis 3: 1-year lagged EITC treated the same as in the main model.

Adjusted for: non-familial homicide rate, state gross domestic product, maximum TANF benefit, minimum wage, ratio of females to males aged 25 years or older with a college degree or higher, per cent uninsured, firearm ownership, per cent female-headed households, per cent black, per cent married, per cent divorced and per capita alcohol consumption.

Coefficient indicates change in IPH rates per 100 000 female adult-years for additional 10% in state EITC (measured as percentage of federal EITC).

EITC, Earned Income Tax Credit; TANF, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families.

DISCUSSION

In this national study conducted using data over a 27-year period, increases in state EITC were not significantly associated with IPH rates. To our knowledge, this is the first national study assessing the impact of EITC policies on IPH rates. EITC is a popular programme among advocates for IPV survivors as a promising means for victims to leave abusive relationships. However, EITC benefits may not effectively reach these victims. Potential reasons for lack of association may include: (1) economic abuse or control of finances by the abusive partner3–5; (2) prohibitive eligibility requirements for receiving the EITC19; and (3) insufficient data quality of IPH reporting and limited power to detect changes in IPH rates due to its relative rarity.

IPV usually involves financial control that may prevent access to EITC funds and stymie the ability to maintain employment.3,5 Moreover, IPV victims who leave or are abandoned by their spouses are generally required to file taxes as married filing separately, which makes them ineligible for the EITC.19 Some states are recognising the need to increase accessibility to EITC. For example, in 2017 Massachusetts enacted a provision to expand access to the EITC by victims of IPV, regardless of their filing status.20

Our study examined the effect of state EITC policies at the population level, but we were not able to identify effects of EITC among individuals who actually received the credit. Additionally, the internal validity of our results could be threatened by unobserved covariates that varied differentially by state over time. Further research should explore the causal pathways between income supplements and IPV, such as family income, labour force participation and downstream effects on stress and coping behaviours. Future research should also evaluate changes in policies (eg, in Massachusetts) that aim to increase accessibility of EITC for IPV victims because cash transfers may be a promising mechanism of primary prevention if benefits reach the targeted population subgroups.

What is already known on the subject

The Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) is the largest cash transfer programme to low-income working families in the USA.

The EITC improves maternal and child health outcomes that share some determinants with violence outcomes such as intimate partner homicide (IPH).

What this study adds

We found no statistically significant association between state EITC generosity and IPH rates.

Economic control in abusive relationships and EITC eligibility rules may prohibit victims of abuse from accessing EITC benefits.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge James Alan Fox, PhD, for assistance in procuring data, and support provided by a cooperative agreement with the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention.

Funding

This study was funded by a cooperative agreement with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (1U01CE002945).

Footnotes

Competing interests AR-R is on the editorial board of Injury Prevention.

Patient and public involvement Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Patient consent for publication Not required.

Ethics approval This study was approved by the University of Washington’s Institutional Review Board.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

REFERENCES

- 1.Peterson C, Kearns MC, McIntosh WL, et al. Lifetime economic burden of intimate partner violence among U.S. adults. Am J Prev Med 2018;55:433–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Petrosky E, Blair JM, Betz CJ, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in homicides of adult women and the role of intimate partner violence — United States, 2003–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017;66:741–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goodman LA, Smyth KF, Borges AM, et al. When crises collide. Trauma Violence Abuse 2009;10:306–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tolman RM, Raphael J. A review of research on welfare and domestic violence. J Soc Issues 2000;56:655–82. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hahn SA, Postmus JL. Economic empowerment of impoverished IPV survivors: a review of best practice literature and implications for policy. Trauma Violence Abuse 2014;15:79–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. Policy basics: the earned income tax credit, 2019. Available: https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/policy-basics-the-earned-income-tax-credit [Accessed 6 Jan 2020].

- 7.Markowitz S, Komro KA, Livingston MD, et al. Effects of state-level earned income tax credit laws in the U.S. on maternal health behaviors and infant health outcomes. Soc Sci Med 2017;194:67–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pinchevsky GM, Wright EM. The impact of neighborhoods on intimate partner violence and victimization. Trauma Violence Abuse 2012;13:112–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fridel EE, Fox JA. Gender differences in patterns and trends in U.S. homicide, 1976–2017. Violence Gend 2019;6:27–36. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zeoli AM, McCourt A, Buggs S, et al. Analysis of the strength of legal firearms restrictions for perpetrators of domestic violence and their associations with intimate partner homicide. Am J Epidemiol 2018;187:2365–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fox JA. Missing data problems in the SHR. Homicide Stud 2004;8:214–54. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shapiro I State EITC provisions 1977–2018. Available: https://users.nber.org/~taxsim/state-eitc.html [Accessed 5 Dec 2019].

- 13.Hoffman SD. A good policy gone bad: the strange case of the non Refundable state EITC, 2007. Available: http://lerner.udel.edu/economics/workingpaper.htm [Accessed 6 Jan 2020].

- 14.Congressional Research Service. The earned income tax credit (EITC): an overview, 2018. Available: https://crsreports.congress.gov [Accessed 15 Jun 2020].

- 15.Lenhart O The effects of state-level earned income tax credits on suicides. Health Econ 2019;28:1476–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.University of Kentucky Center for Poverty Research. National welfare data, 1980–2018, 2019. Available: http://ukcpr.org/resources/national-welfare-data [Accessed 6 Jun 2020].

- 17.Zeoli AM, Webster DW. Effects of domestic violence policies, alcohol taxes and police staffing levels on intimate partner homicide in large US cities. Inj Prev 2010;16:90–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gollub EL, Gardner M. Firearm legislation and firearm use in female intimate partner homicide using national violent death reporting system data. Prev Med 2019;118:216–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brown FB. Permitting abused spouses to claim the earned income tax credit in separate returns, 2016. Available: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmjowl/vol22/iss3/2 [Accessed 5 Dec 2019].

- 20.Pescatore L Massachusetts takes action to connect domestic violence survivors to EITC, 2017. Available: http://www.taxcreditsforworkersandfamilies.org/news/massachusetts-takes-action-connect-domestic-violence-survivors-eitc/ [Accessed 6 Jan 2020].