Abstract

We use county level data from the United States to document the role of social capital the evolution of COVID-19 between January 2020 and January 2021. We find that social capital differentials in COVID-19 deaths and hospitalizations depend on the dimension of social capital and the timeframe considered. Communities with higher levels of relational and cognitive social capital were especially successful in lowering COVID-19 deaths and hospitalizations than communities with lower social capital between late March and early April. A difference of one standard deviation in relational social capital corresponded to a reduction of 30% in the number of COVID-19 deaths recorded. After April 2020, differentials in COVID-19 deaths related to relational social capital persisted although they became progressively less pronounced. By contrast, the period of March–April 2020, our estimates suggest that there was no statistically significant difference in the number of deaths recorded in areas with different levels of cognitive social capital. In fact, from late June-early July onwards the number of new deaths recorded as being due to COVID-19 was higher in communities with higher levels of cognitive social capital. The overall number of deaths recorded between January 2020 and January 2021 was lower in communities with higher levels of relational social capital. Our findings suggest that the association between social capital and public health outcomes can vary greatly over time and across indicators of social capital.

Keywords: COVID-19, Social capital, Deaths, Social determinants of health, United States

1. Introduction

Social interactions foster the spread of infectious diseases (Mossong et al., 2008; Béraud et al., 2015; Leung et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2019; Fumanelli et al., 2013). The early and rapid spread of the COVID-19 pandemic and the high mortality observed in East Asia and Southern Europe at the beginning of 2020 has been considered to be the result, at least in part, of the fact that countries in these regions have high levels of social mixing across age groups within extended family units (Dowd et al., 2020). However, there is increasing evidence that while patterns of family interactions remain important to determine disease spread and fatality, the broader social bonds that exist within a community explain differences in the evolution of the COVID-19 pandemic (Bartscher et al., 2020). Social bonds determine not only transmission opportunities for the virus, but also the extent to which individuals are able to access and act upon health information, the norms of reciprocity and trust that exist between community members, how easy it is for communities to organize support for their members so that they can adopt protective behaviors, as well as the resources communities can deploy to halt disease spread and care for those who are infected.

Social capital reflects the resources and benefits that individuals and groups acquire through connections with others and involves both shared norms and values that promote cooperation as well as actual social relationships (Kawachi et al., 2008; Fukuyama, 2000; Putnam, 1993). Social capital is similar to civic capital, which is conceived as ‘the set of values and beliefs that help a group overcome the free-rider problem in the pursuit of socially valuable activities’ (Guiso et al., 2011). However, the concept of social capital emphasizes social relations established and cultivated through participation in groups and associations created with the aim of promoting common goals, which are conceived as important in their own right, as well as being one of the mechanisms through which values and beliefs are developed. Social capital comprises a cognitive component, reflecting attitudes and dispositions that promote interpersonal cooperation, as well as a relational component, reflecting the strength of social connections within a community; relations that are cemented through participation, for example, in associations, local community groups and volunteering. We argue that this is an important distinction in the current literature on the role of social/civic capital during the pandemic (see Ding et al., 2020 for an important exception), and that the two components played different roles in shaping variations across communities in moments of the evolution of the COVID-19 pandemic. This is because the two components of social capital influence health through different channels, and the relative importance of different channels differed over time as the pandemic spread through the world and communities in the United States. For this reason, evaluating associations only at a certain point, or cumulative outcomes over the long-term, can prevent researchers and analysts from identifying important patterns that can help to better understand the role of social capital in promoting health during various stages of a pandemic.

We use data on deaths recorded as being due to COVID-19 (i.e. deaths for which COVID-19 is reported as a cause of death on the death certificate) in United States counties to consider if community level cognitive and relational social capital can explain the geographic variation in the evolution of the COVID-19 pandemic between January 2020 and January 2021. We complement analyses conducted at the county level on the number of deaths with analyses conducted at the state level on the relationship between social capital and the number of hospitalizations due to COVID-19.

The United States witnessed a very rapid spread of COVID-19 and, as of January 2021, was the country with the largest number of identified cases and deaths. It was also a country with large variations in how soon and for how long communities were required to implement behavioral changes to reduce disease spread, were advised to do so or were left to make decisions on their own, and how compliant populations were with advice and regulations. Finally, it is a country with large geographical disparities in socio-economic and demographic characteristics and social capital (Putnam, 2000). Although a large literature in public health documents a strong association between social capital and health, much less is known about the influence of social capital on the spread of infectious diseases such as COVID-19 (Rodgers et al., 2019), and on the adoption of behavioral changes that are necessary to halt disease spread in an uncertain and rapidly evolving sanitary and economic environments.

The relational dimension of social capital, by promoting physical contacts, might have induced faster disease spread at the start of the pandemic when little information was available on the disease, transmission mechanisms and its presence in the United States. However, beyond this very initial period, we hypothesize that, as soon as more information on the virus became available, relational social capital contributed to lower infections. Furthermore, we hypothesize that reduction in infections and greater awareness of which groups were at an especially high risk of suffering severe consequences if infected in turn contributed to reduce the overall number of deaths due to COVID-19. Such a reduction could have been due to the following channels: by promoting better overall health before the pandemic unfolded, by facilitating information exchange, by facilitating the adoption of health protective behaviors, by increasing the value of adopting such behaviors given the wider set of social bonds tying community members together, by providing strong social support networks individuals could rely on, and by mobilizing resources. At the same time, we hypothesize that the cognitive dimension of social capital, by promoting norms of reciprocity, reduced the overall number of individuals who were infected and fatality among those infected by promoting greater information exchange and adherence to behaviors directed at protecting other members of the community.

2. The contribution of social capital to COVID-19 deaths

Communities with high levels of relational social capital tend to have a dense web of interpersonal relations, and therefore may have been especially vulnerable to disease spread at the start of the pandemic (Bai et al., 2020). Many individuals suffering from COVID-19 are asymptomatic or have only light symptoms (Bai et al., 2020). Until late February and early March 2020 it was thought that only contact with individuals returning from China or other high prevalence destinations and displaying symptoms could pose a risk. It is now accepted that the SARS-CoV-2 virus can be transmitted by asymptomatic or pre-symptomatic individuals (Aguilar et al., 2020; Arons et al., 2020). Therefore, in such early phases, individuals in communities with high levels of relational social communities may have been more exposed to the SARS-CoV-2 virus without being aware of the necessity of protecting themselves and, especially, of protecting individuals with a high risk of dying if infected.

Beyond the initial phase, as knowledge about the virus increased, both the relational and the cognitive dimensions of social capital could have become an important resource for communities, and be implicated in lowering transmission and fatality among those infected with the disease. In this stage, we expect transmission to be lower in high social capital communities, because we expect that in these communities, information about the virus circulated faster than in other communities and that individuals were better prepared to change their behavior, whether voluntarily or in response to government mandated regulations. We expect behavioral differences to arise because of better information about the virus, stronger sense of mutual responsibility, greater trust in public health authorities and greater social monitoring in high social capital communities.

The public health literature indicates that social capital facilitates the diffusion of information: in communities with a high level and a wide set of social connections and where norms of reciprocity and cooperation are high, transaction costs are typically lower and access to material resources and to health-related information is higher (Stephens et al., 2004; Viswanath et al., 2006). Differences in access to health information may have been especially important in the context of COVID-19, a new disease caused by a virus not known until December 2019. Social capital may have facilitated the acquisition of information on behaviors that protected individuals from contracting and transmitting COVID-19 once knowledge about SARS-CoV-2 increased (Lin et al., 2014; Savoia et al., 2013). Social capital, both relational and cognitive, may have also importantly shaped a community's overall sense of mutual responsibility and support (Coleman, 1998; Putnam, 1993), determining the community's willingness to follow advice and regulations designed to reduce transmission and to enforce social monitoring (Szreter and Woolcock, 2004).

Evidence on the role of social and civic capital on information acquisition and mobility changes during the COVID-19 pandemic, both voluntary and in response to regulations, is emerging (Bargain & Aminjonov, 2020; Durante et al., 2021; Borgonovi and Andrieu, 2020; Bartscher et al., 2020; Barrios et al., 2020). Social capital has also been identified as an important asset for individuals and communities during previous pandemics such as the H1N1 pandemic, leading to greater awareness and adoption of health protective behaviors, such as wearing face masks and vaccinating (Chuang et al., 2015; Rönnerstrand, 2014, 2016).

Existing work on the behavioral changes that communities implemented in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, and how these vary across communities with different levels of social capital, is limited to what happened in the early period of the pandemic, until early summer of 2020. However, the pandemic continued to influence the health, social and economic life of communities well beyond the first months of 2020. In fact, an important feature of the pandemic is the long term uncertainty and disruption it caused to communities worldwide. We expect that at the start of the pandemic, information acquisition and the ability to act on such information were especially important channels through which social capital influenced the outcomes of the pandemic. Beyond the start of the pandemic, information became more widespread and therefore we expect the relevance of information differentials across communities with different levels of social capital to fade. However, over time, we expect that communities' ability to adapt to new patterns of behaviors in a sustained way begun to play an increasingly important role in shaping the outcomes of the pandemic. In this phase, we expect that communities with established patterns of citizens’ involvement in organized activities directed at promoting the well-being of the community (such as membership in associations, volunteering and participation in local initiatives) will be better prepared to organize community operations to support the adoption of habits that protect community members from COVID-19 in a sustained way. Examples of such actions include, for example, the organization of continuous and effective distribution campaigns of face masks, and/or the reallocation of public outdoor spaces and well-ventilated indoor spaces to cater to the needs of community members while reducing transmission. As a result, we expect that relational social capital played an especially important role in reducing the death toll of the pandemic over the long run. Crucially, this channel reflects relational but not cognitive social capital.

We expect social capital to shape fatality among those who became infected with the virus through prevention and behavioral changes. A large literature documents that relational and cognitive social capital can lead to a lower incidence of chronic conditions and a better management of such conditions among sufferers (Rodgers et al., 2019). Because COVID-19 fatality is particularly high among individuals with prior health conditions (Li et al., 2020; Zhou et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2020; Jordan et al., 2020), fatality among those infected could be lower in communities with high levels of relational and cognitive social capital. Another important feature of COVID-19 is that many of those infected require hospitalization and intensive care. Social capital could have influenced fatality through an indirect effect on health care capacity. Communities with high levels of relational and cognitive social capital could be more willing and better able to lobby decision makers and key providers and obtain adequate resources to support those in need of medical care. These factors predate the pandemic and do not depend on behavioral changes occurring in response to the pandemic, but the capacity to acquire and effectively use resources could have played an especially important role once resource constraints loosened as the pandemic progressed, and as the total number of individuals infected with COVID-19 became very large.

Better information and norms of reciprocity in high social capital communities may have also promoted the adoption of behaviors that reduced the likelihood of dying among those infected by the disease. By reducing transmission beyond the initial phase when the cumulative number of cases grew very large, social capital could have lowered fatality among those infected by preventing hospitals becoming overwhelmed with patients requiring care. Moreover, COVID-19 is a disease with a marked age-related fatality profile (Dowd et al., 2020; Li et al., 2020; Zhou et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2020; Jordan et al., 2020) and, as indicated before, is particularly fatal among individuals with pre-existing conditions. Therefore, fatality can vary markedly depending on which population groups are infected. Communities with high levels of relational social capital may have been better able at organizing successful initiatives aimed at reducing infections among vulnerable groups. For example, volunteering groups could have been active in organizing the delivery of groceries, medications and other essentials to at-risk groups to limit their exposure. They could have provided health care facilities and nursing homes with equipment and spaces designed to allow residents to be able to communicate with loved ones safely, they could have organized outdoor activities for young people to limit house-to-house in-door contacts, or they could have helped businesses such as bars and restaurants to operate using outdoor spaces such as pavements and car parks.

3. Data and methods

We estimate the role of social capital in shaping deaths related to COVID-19 between January 2020 and January 2021. We describe variables used in the empirical analyses and report detailed information on data sources and descriptive statistics in Table 1 . We complement analyses on the number of deaths at the county level with analyses at the state level, in which we estimate to what extent between-state differences in hospitalizations related to COVID-19 differed across communities with different levels of social capital. In order to isolate associations accounting for differences in regulations or recommendations promoting sheltering-in-place, we replicated both analyses at the state level, adding a control for government interventions. Since regulations and recommendations varied over time but did not differ or differed only marginally across counties in the same state, county level estimates account for differences in regulations through the inclusion of state fixed effects.

Table 1.

List of variables and descriptives.

| Variables | Mean | SD | Notes | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome variables: | ||||

|

179 | 608 | On January 31, 2021 | https://usafacts.org/visualizations/coronavirus-covid-19-spread-map/ |

|

10 | 2 | On January 31, 2021 | https://covidtracking.com/about-data/sources |

| Control variables: | ||||

|

0 | 1 | Standardised | https://www.jec.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/republicans/2018/4/the-geography-of-social-capital-in-america#toc-007-backlink |

|

0 | 1 | Standardised | https://www.jec.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/republicans/2018/4/the-geography-of-social-capital-in-america#toc-007-backlink |

|

145019 | 397479 | Used for weights and compute density | https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/popest/technical-documentation/file-layouts/2010-2018/cc-est2018-alldata.pdf |

|

0.25 | 0.05 | Mean centered in analysis | https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/popest/technical-documentation/file-layouts/2010-2018/cc-est2018-alldata.pdf |

|

41 | 121 | Per 100, 000 individual and mean centered in analysis | Definitive Healthcare: https://opendata.arcgis.com/datasets/1044bb19da8d4dbfb6a96eb1b4ebf629_0.csv |

|

0.62 | 0.15 | Mean centered in analysis | https://github.com/tonmcg/US_County_Level_Election_Results_08-16/blob/master/2016_US_County_Level_Presidential_Results.csv |

|

0.10 | 0.13 | Mean centered in analysis | https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/popest/technical-documentation/file-layouts/2010-2018/cc-est2018-alldata.pdf |

|

0.15 | 0.06 | Mean centered in analysis | U.S. Census Bureau, Small Area Income and Poverty Estimates (SAIPE) Program |

|

0.68 | 1.23 | In thousands, mean centered in analysis | https://data.cms.gov/stories/s/COVID-19-Nursing-Home-Data/bkwz-xpvg/. Click or tap if you trust this link.">https://data.cms.gov/stories/s/COVID-19-Nursing-Home-Data/bkwz-xpvg/ |

|

10868 | 5247 |

Until January 2021 Tenths of mm, mean centered in analysis |

Menne, M.J., I. Durre, B. Korzeniewski, S. McNeal, K. Thomas, X. Yin, S. Anthony, R. Ray, R.S. Vose, B.E.Gleason, and T.G. Houston, 2012: Global Historical Climatology Network -Daily (GHCN-Daily), Version 3]. NOAA National Climatic Data Center. http://doi.org/10.7289/V5D21VHZ [01-09-2020]. |

|

53 K | 14 K | In thousands and mean centered in analysis | U.S. Census Bureau, Small Area Income and Poverty Estimates (SAIPE) Program |

|

0.92 | 0.13 | Low” below median and “high” above median. Min (0.44) and max (1.37). | www.policymap.com |

|

NA | NA | https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/county-typology-codes/ | |

|

12.9 | 5.8 | Mean centered in analysis | 2014-18 American Community Survey 5-yr average county-level estimates |

|

317 | 1984 | Mean centered in analysis | U.S. Census Bureau, Census of Population and Housing (https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2011/compendia/usa-counties-2011.html#LND) |

| State level variables | ||||

| Covid-19 hospitalization (time-varying analysis outcome) | 1447 | 1602 | Weekly number of patients hospitalized with Covid-19 or who are suspected to have Covid-19. Definitions vary by state (for example paediatric patients are included in this metric in some but not all states). | https://covidtracking.com/data |

|

NA | NA | Thomas Hale, Tilbe Atav, Laura Hallas, Beatriz Kira, Toby Phillips, Anna Petherick, and Annalena Pott (2020). Variation in US states' responses to COVID-19. Blavatnik School of Government. | |

Notes: Statistics computed on 2281 counties (except for the average daily cases in the early phase), representing 94.5% of the US population.

“COVID-19 risk index normalized by adult population in 2020. PolicyMap created this index for the New York Times. It represents the relative risk for a high proportion of residents in a given area to develop serious health complications from COVID-19 because of underlying health conditions identified by the CDC as contributing to a person's risk of developing severe symptoms from the virus. These conditions include COPD, heart disease, high blood pressure, diabetes, and obesity. Estimates of COPD, heart disease, and high blood pressure prevalence are from PolicyMap's Health Outcome Estimates. Estimates of diabetes and obesity prevalence are from the CDC's U.S. Diabetes Surveillance System”.

4. Variables

4.1. Outcome variables

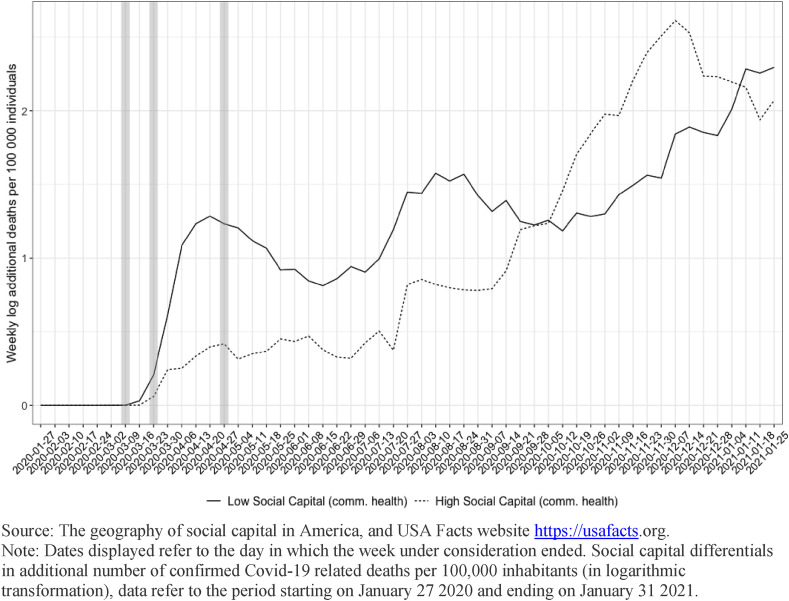

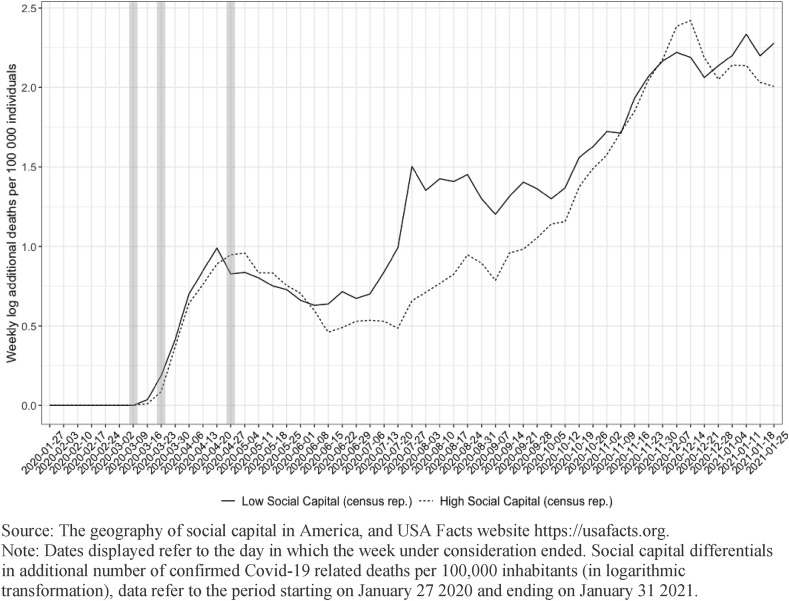

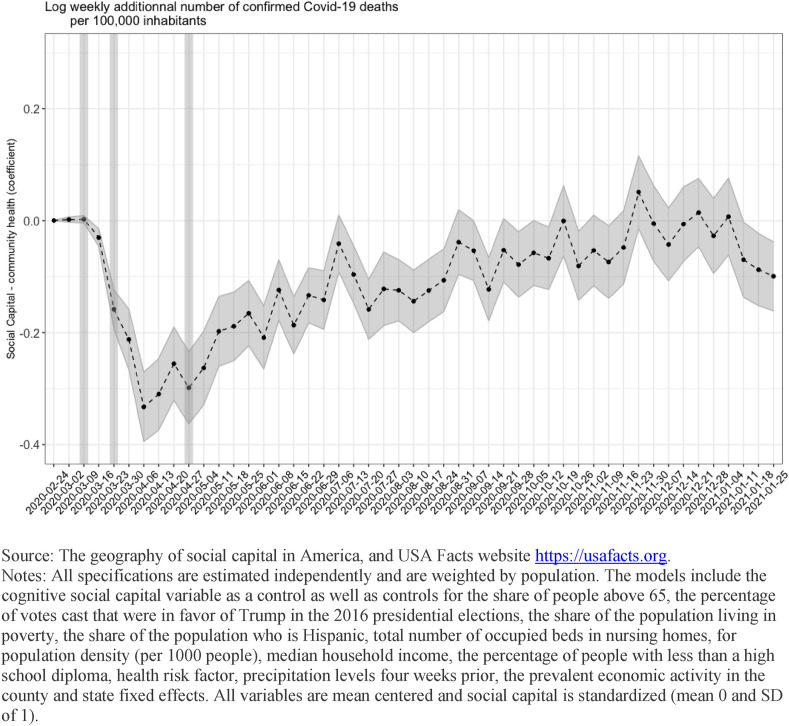

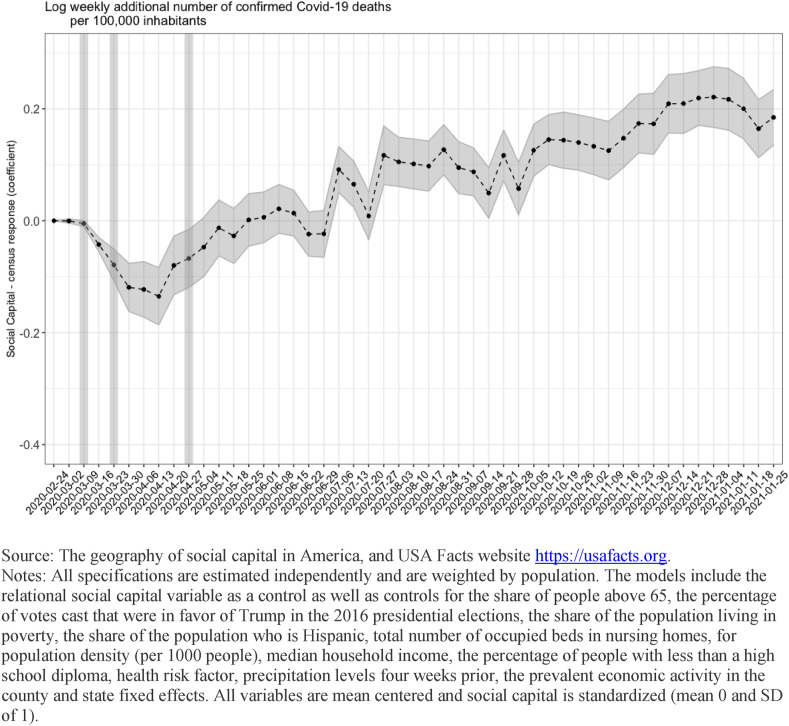

First, we analyze COVID-19 deaths. In descriptive analyses reported in Fig. 1, Fig. 2 , and time varying analyses reported in Fig. 3, Fig. 4 , the outcome variable is the log of the additional number of confirmed COVID-19 deaths per 100,000 inhabitants within a county in a given week for the period January 27, 2020 and January 31, 2021. In Table 2 , the outcome variable is the log of the cumulative number of confirmed COVID-19 deaths per 100,000 inhabitants within a county over the period January 22, 2020 and January 31, 2021.

Fig. 1.

Differentials in Covid-19 deaths across areas with different levels of relational social capital.

Fig. 2.

Differentials in Covid-19 deaths across areas with different levels of cognitive social capital.

Fig. 3.

Relational social capital and the evolution of deaths related to Covid-19 in the United States.

Fig. 4.

Cognitive social capital and the evolution of deaths related to Covid-19 in the United States.

Table 2.

The association between social capital and Covid-19 deaths, up to January 31, 2021.

| Dependent variable: |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cumulative deaths (January 31, 2021, in log) | |||||||||

| Relational |

Cognitive |

Both components |

Relational |

Cognitive |

Both components |

Relational |

Cognitive |

Both components |

|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | |

| Constant | 5.096*** (0.210) | 5.869*** (0.212) | 5.089*** (0.209) | 4.734*** (0.143) | 5.180*** (0.144) | 4.713*** (0.144) | 4.863*** (0.133) | 5.343*** (0.136) | 4.817*** (0.133) |

| Social Capital | −0.942*** (0.066) | −0.967*** (0.066) | −0.618*** (0.047) | −0.611*** (0.047) | −0.723*** (0.044) | −0.711*** (0.044) | |||

| (community health) | |||||||||

| Social Capital | −0.180*** (0.050) | −0.237*** (0.048) | 0.109*** (0.038) | 0.075** (0.037) | 0.209*** (0.036) | 0.180*** (0.035) | |||

| (census response) | |||||||||

| County-level controls | NO | NO | NO | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Political control | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | YES | YES | YES |

| Economic Dependency | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Sate FE |

YES |

YES |

YES |

YES |

YES |

YES |

YES |

YES |

YES |

| Observations | 2284 | 2284 | 2284 | 2284 | 2284 | 2284 | 2284 | 2284 | 2284 |

| R2 | 0.508 | 0.466 | 0.513 | 0.806 | 0.792 | 0.806 | 0.833 | 0.815 | 0.835 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.496 | 0.453 | 0.501 | 0.800 | 0.786 | 0.801 | 0.828 | 0.810 | 0.830 |

| Residual Std. Error | 433.388 (df = 2229) | 451.444 (df = 2229) | 431.153 (df = 2228) | 272.849 (df = 2220) | 282.651 (df = 2220) | 272.660 (df = 2219) | 253.357 (df = 2219) | 266.228 (df = 2219) | 251.882 (df = 2218) |

| F Statistic | 42.610*** (df = 54; 2229) | 36.034*** (df = 54; 2229) | 42.709*** (df = 55; 2228) | 146.171*** (df = 63; 2220) | 133.808*** (df = 63; 2220) | 144.151*** (df = 64; 2219) | 172.437*** (df = 64; 2219) | 152.895*** (df = 64; 2219) | 172.195*** (df = 65; 2218) |

Notes: *p**p***p<0.01. Standard errors in parentheses. All specifications are weighted for population. All variables are mean centered and social capital is standardized (mean 0 and SD 1). County-level controls include: ICU beds (number of beds per 100,000 people), share of people above 65, share of people in poverty, share of Hispanics, total number of occupied beds in nursing homes, cumulative precipitation levels, the household median income, total number of occupied beds in nursing homes, the percentage of people with less than a high school diploma and health risk factor. Political control: Share of Republican votes in 2016 presidential elections.

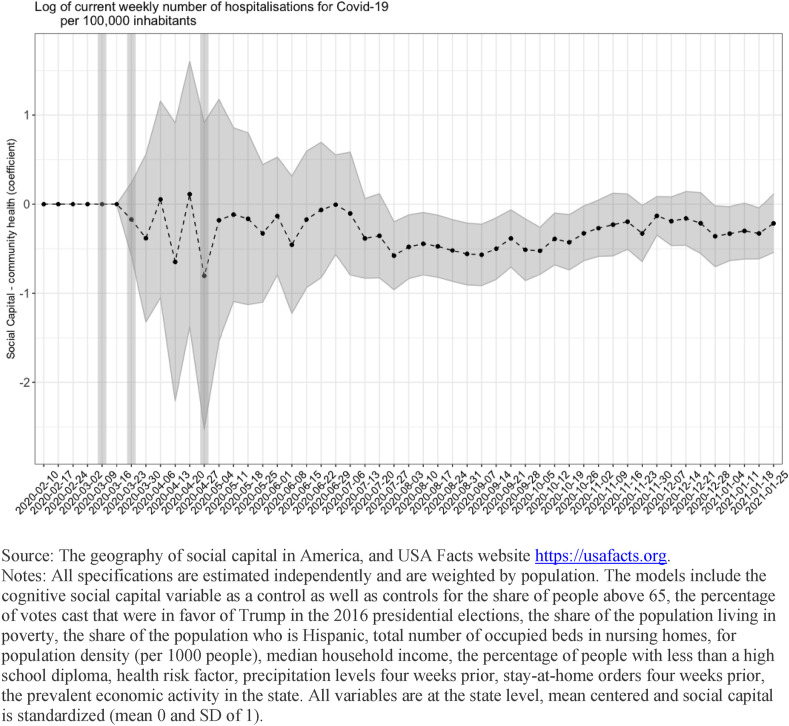

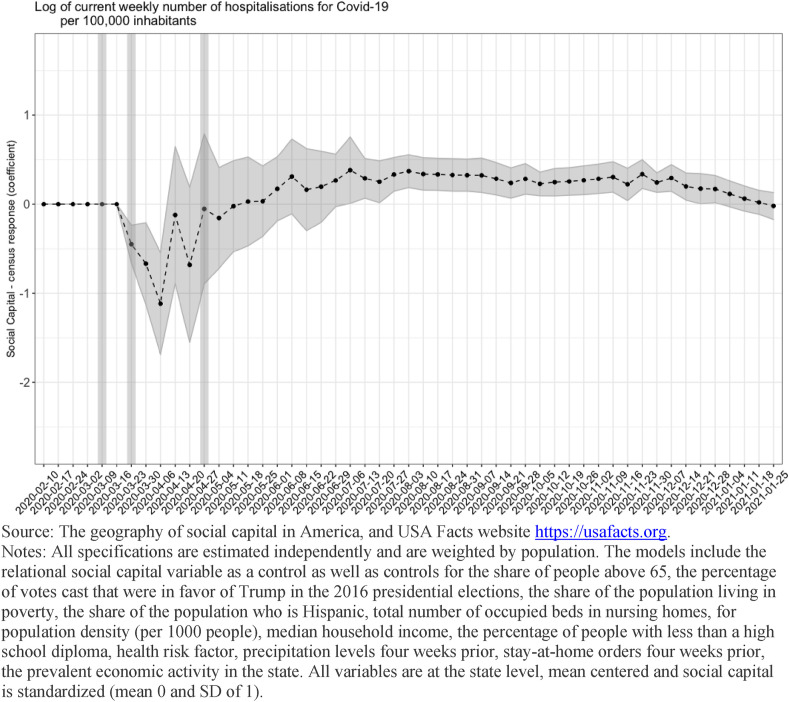

We then analyze the number of hospitalizations due to COVID-19. In time varying analyses reported in Fig. 5, Fig. 6 , the outcome variable is the log of the number of people currently being hospitalized due to COVID-19 per 100,000 inhabitants recorded in a state in a particular week over the period February 10, 2020 and January 31, 2021.

Fig. 5.

Relational social capital and the evolution of hospitalisations related to Covid-19 in the United States, state level (controlling for SIPOs).

Fig. 6.

Cognitive social capital and the evolution of hospitalisations related to Covid-19 in the United States, state level (controlling for SIPOs).

4.2. Key independent variable

Our key independent variables are indicators of relational social capital and of cognitive social capital.

Relational social capital is a county level indicator measured through “The geography of social capital” project. Data are available for 2992 counties and cover 99.7 percent of the American population (μ = 0; σ = 1). The indicator is an aggregate index constructed using the following sub-indices: the number of registered non-religious non-profits per 1000 people; the number of religious congregations per 1000 people; the share of adults who reported having volunteered for a group in the past year; the share of adults who reported having attended a public meeting regarding community affairs in the past year; the share of adults who reported having worked with neighbors to fix/improve something in past year; the share of adults who served on a committee or as an officer of a group; the share of adults who attended a meeting where political issues were discussed in past year and the share of adults who took part in a march/rally/protest/demonstration in past year.

Cognitive social capital is measured through the county-specific response rate to the 2010 decennial census. Unfortunately, more indicators of cognitive social capital, such as interpersonal trust, are not available at the county level. However, response rates to the decennial census are correlated with other indicators of cognitive social capital at the state level. This measure has also been used in prior work as an indicator of cognitive social capital and is part of broad social capital indices such as the Penn State Index (Rupasingha et al., 2006). A summary of data sources used to construct the social capital indicator is available in Annex Table A1. Details on the index construction and validation can be found at https://www.jec.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/republicans/2018/4/the-geography-of-social-capital-in-america#toc-007-backlink.

4.3. Control variables

Economic orientation (dependency) of the local economy refers to the 2015 classification into one of the following six mutually exclusive categories of the prevalent economic activity of a county: category 0 refers to non-specialized counties; category 1 indicates counties with economies that are highly dependent on farming; category 2 indicates counties with economies that are highly dependent on mining; category 3 indicates counties with economies that are highly dependent on manufacturing; category 4 indicates counties with economies that are highly dependent on federal/state government, and category 5 indicates counties with economies that are highly dependent on recreation.1

Population density represents the total population within a county divided by the land area of that county measured in square miles (US Census methodology). We express the variable in 1000 individuals per square mile.

The share of population above 65 refers to the total number of people above the age of 65 divided by the total population.

The percentage of votes cast in the 2016 presidential election that were in favor of Trump is used as an indicator of the political landscape in the country.

The share of the population living in poverty in the county and median household income within the county are used as indicators of living conditions.

The share of the population with less than a high school diploma in the county is used to identify educational attainment.

The share of the population in the county who is Hispanic is used as an indicator of the demographic make-up of the county.

Number of intensive care (ICU) beds refers to healthcare capacity. Data are provided at the hospital level; therefore, we aggregated hospital figures to obtain county level estimates. The data come from Definitive Healthcare, which contains information on the typical bed capacity of hospitals. The number of ICU beds refers to the number of qualified ICU based on definitions by Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (section 2202.7, 22-8.2) and include ICU beds, psychiatric ICU beds, and Detox ICU beds. We express the variable as number of beds per 100,000 individuals.

In models estimating the number of hospitalizations at the state level, we control for whether government regulations or recommendations promoting sheltering-in-place behaviors were in place four weeks prior to the week in which hospitalizations were recorded (Hale et al., 2020). This is to account for the delay between transmission, diagnosis and the development of symptoms requiring hospitalizations (Linton et al., 2020).

Total number of occupied beds in nursing homes within each county is introduced because of evidence that individuals in nursing homes were especially hard-hit by the virus.

Weather conditions, which could potentially shape the likelihood individuals will engage in activities potentially leading to infection is accounted for through rain precipitation. Data for each county are computed as the total precipitation over the period considered four weeks prior to the week under analysis.

Finally, we add a control for the health situation of the county using the index created by PolicyMap.2 The index measures the share of a county's population suffering from underlying health conditions that have been identified as contributing to a person's risk of suffering severe symptoms if infected with the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

4.4. Analytical strategy

We provide descriptive evidence for the period January 27, 2020–January 31, 2021 on the evolution of COVID-19 deaths between areas with high (top 25% in social capital) and counties with low levels of social capital (bottom 25% in social capital), when social capital is measured through indicators that reflect relational and cognitive social capital. Vertical marks indicate when governmental advice on social distancing was first made, the period when sheltering-in-place-orders (SIPOs) came into effect in most counties and the period when SIPOs were lifted in the majority of counties.

We examine how the association between social capital and deaths changed over time. As identified in the review of the literature, social capital could influence the number of deaths by shaping both the overall number of people who become infected with the virus and the likelihood of dying if infected. The time varying analyses reported in Fig. 3, Fig. 4 were estimated using equation (1).

| (1) |

We fit equation (1) by regressing the log of the number of confirmed COVID-19 deaths recorded in a specific week on the two social capital indicators controlling for: population density, share of people above 65, share of people in poverty, share of Hispanics, share of Republican votes in 2016 presidential elections, precipitation levels (precipitation levels are introduced using data that refer to the week that precedes by four weeks the week under analysis to account for the delay between behavior, infection, diagnosis and death), household median income, total number of occupied beds in nursing homes, the percentage of people with less than a high school diploma, and health risk factor and state fixed effects. In Fig. 3, Fig. 4 we plot the point estimate and associated confidence intervals at the 95% level for each of the social capital indicators. Since equation (1) includes state fixed effects, estimates represent the within-state, between-county variation in COVID-19 deaths associated with each of the two social capital indicators.

| (2) |

We repeat a similar exercise for COVID-19 hospitalizations estimating equation (2). We regress the log of the current number of hospitalizations related to COVID-19 recorded in a specific week on the two social capital indicators. Because data on hospitalizations is limited to state level aggregates, in equation (2) all controls are aggregated at the state level. Although we are not able to control for state fixed effects, we were able to add a dichotomous indicator of whether SIPOs were in place four weeks prior to the week under analysis. Finally, we estimated equation (1) considering the entire period under analyses: the dependent variable consisted in the cumulative number of COVID-19 deaths in each county over the entire period. Due to data quality and coverage we do not report the cumulative number of hospitalizations. Data on hospitalizations refer to the number of individuals being hospitalized in a specific week, but because individuals can be hospitalized for different periods, calculating the cumulative number of hospitalizations is not possible.

All specifications are weighted by population, which allows us to derive estimates that are representative at the population level and are not overly sensitive to disease spread and fatality observed in scarcely populated counties. To evaluate the robustness of findings to omitted variable bias, we run Oster's test (2019). The test allows us to identify when changes in the coefficients of key independent variables and changes in the R-squared of regressions run before and after the inclusion of additional controls are large, a possible indication of omitted variable bias. Estimations were performed in Stata using the psacacl program (Oster, 2013).

5. Results

5.1. Descriptive results

Fig. 1, Fig. 2 illustrate differences between counties with high and low levels of social capital in deaths. Fig. 1 illustrates the relationship between the relational component of social capital and the number of deaths while Fig. 2 illustrates the relationship between the cognitive component of social capital and the number of deaths. Vertical lines mark the time when the importance of sheltering-in-place were first made on March 17, when many counties introduced SIPOs in late March (data on the timeline of SIPOs come from Mervosh et al., 2020), and when in many states such orders were first lifted.

Descriptive evidence presented in Fig. 1, Fig. 2 suggest that at the start of the pandemic there were no differences between communities with higher levels of relational and cognitive social capital in the number of deaths due to COVID-19. However, Fig. 1 suggests that right after announcements on the importance of social distancing were first made and before mandatory regulations to promote social distancing were put in place, the number of deaths attributed to COVID-19 grew less fast in communities with high levels of relational social capital than in communities with low levels of relational social capital. The difference in the number of deaths recorded per week became very large during mandatory social distancing when the growth in infections was pronounced because of the lag between behavior that leads to infection, diagnosis and death. Differentials between counties with different levels of relational social capital remained wide after the relaxation of mandatory social distancing in many communities. However, from mid-August, the difference became less pronounced and reversed at the end of September: from that moment onwards, the number of deaths was larger in communities with higher levels of relational social capital. From early January 2021 onwards, communities with higher levels of relational social capital started to record, once more, a lower number of deaths than communities with lower levels of relational social capital.

Fig. 2 illustrates trends when cognitive social capital is considered. Differences in the number of deaths between communities with higher and lower levels of cognitive social capital were less pronounced in the period of mandatory social distancing. Between mid-April 2020 and the beginning of June 2020, areas with higher levels of cognitive social capital recorded a larger number of new deaths. From early June 2020, communities with higher levels of cognitive social capital experienced once more lower deaths than areas with lower levels of cognitive social capital. In late November and December, communities with higher cognitive social capital experienced more deaths and trends reversed, with communities with lower levels of cognitive social capital recording a larger number of new deaths from January 2021. In the following sections we present more rigorous analyses to identify the role of social capital in the evolution of the pandemic in the United States, since descriptive findings reported in Fig. 1, Fig. 2 could reflect differences across counties in factors other than social capital but that are important to determine the evolution of the pandemic.

5.2. How social capital differentials in the number of deaths evolved over time

In Fig. 3, Fig. 4, we illustrate the variation over time in the association between social capital and the propagation of the pandemic by identifying how the log of the number of new COVID-19 deaths recorded in a county was associated with a difference of one standard deviation in relational (Fig. 3) and cognitive social capital (Fig. 4).

Findings reported in Fig. 3 highlight a marked downward trend in the number of COVID-19 deaths in areas with greater relational social capital from March 2020, when the severity of the pandemic became clear, in line with the expectation that relational social capital shaped how communities reacted in response to the pandemic. The difference associated with social capital was large: a difference of one standard deviation in relational social capital corresponded to a reduction of 30% in the number of COVID-19 deaths recorded. After April 2020, differentials in COVID-19 deaths related to relational social capital persisted although they became progressively less pronounced. Between mid-November 2020 and early January 2021, the difference in the number of deaths associated with relational social capital was small in magnitude and not statistically significant at conventional levels. After early January 2021 the difference between communities with different levels of social capital begun to widen once more.

Fig. 4 shows a markedly different pattern with respect to trends in the association between cognitive social capital and COVID-19 deaths. Counties with higher levels of cognitive social capital experienced a marked downward trend in the number of COVID-19 deaths at the beginning of the crisis. The association between cognitive social capital and the number of COVID-19 deaths was largest during the period of mandatory social distancing. Since deaths due to COVID-19 tend to occur around a month after infection, these results suggest that behavioral differences across areas with different levels of cognitive social capital were especially pronounced in the period preceding the introduction of mandatory social distancing measured. After this initial period, our estimates suggest that there was no statistically significant difference in the number of deaths recorded in areas with different levels of cognitive social capital. In fact, from late June-early July onwards the number of new deaths recorded as being due to COVID-19 was higher in communities with higher levels of cognitive social capital.

When we repeat the analysis at the state level using the number of hospitalizations as a measure of the evolution of the crisis, and accounting for differences across states in government regulations and recommendations promoting social distancing through sheltering-in-place orders or guidelines, results are imprecisely estimated (especially at the start of the pandemic when the absolute number of hospitalizations was low) but are in line with estimates for deaths. Both relational and cognitive social capital appear to be associated with a marked lower number of hospitalizations in the spring of 2020 and diverging trends in later periods, with relational social capital being associated with a small but prolonged lower number of new hospitalizations and cognitive social capital being associated with a somewhat higher number of hospitalizations.

Since estimated associations between the two indicators of social capital and COVID-19 deaths and hospitalizations varied over time, in Table 2 we present estimates of the cumulative differentials in the number of deaths observed over the period of January 2020 to January 2021. Results reported in Model 1 of Table 2 indicate that a difference of one standard deviation in relational social capital was associated with a difference of 600 per 1000 cumulative deaths observed in the county.3 Controlling for socio-economic, demographic, behavioral and environmental characteristics in Models 4 and 7 leads to a smaller estimated difference of 500 per 1000. In contrast, the estimated association between cognitive social capital and cumulative deaths is positive when all controls are included.

We check for the omitted variable bias using the Oster test that we perform using Model 7 in Table 2 as a benchmark. The estimated baseline (uncontrolled) effect of social capital on cumulative deaths (January 31, 2021) is −1.061 with an R-squared value of 0.21. The corresponding estimate in the controlled model the coefficient is −0.774, with an R-squared of 0.828. These findings point to a relatively small movement in coefficients along with a large movement in the R-squared values. Importantly, the bias-adjusted coefficient is of the same sign than the controlled effect. According to Oster (2019), this estimate can be considered robust to omitted variable bias. The hypothetical δ suggests a treatment effect of β = 0 only if omitted variables are as important for the outcome than the included control variables.

6. Limitations

Our work considers associations between two indicators of social capital and COVID-19 deaths and COVID-19 hospitalizations. In the review of the literature, we detail how different forms of social capital could contribute to shape deaths and hospitalizations through three distinct mechanisms: by shaping the overall number of people who became infected, by shaping which individuals became infected, and by shaping the treatment received by those who became infected. Because social capital could determine the availability of tests that confirm the disease, the organization of testing facilities and the administration of tests given scarce resources, we decided not to examine differentials in the number of COVID-19 cases across areas with different levels of social capital. The number of infections are in fact especially likely to reflect differences in detection capacity rather than disease spread. Although differential detection could arguably also apply to the number of deaths recorded as being due to COVID-19, measurement issues are likely to play a less important role. We corroborate findings on COVID-19 deaths with hospitalizations, but unfortunately the measure is available only at the state level, rather than at the county level. Other research has used data on excess deaths to account for differential reporting. However, we decided not to rely on a measure of excess deaths because COVID-19 led to profound behavioral changes which could have had an effect on the number of deaths due to other causes (for example, individuals may have delayed seeking treatment fearing that they would be exposed to the virus in hospital settings or decreased mobility reduced motor vehicle fatalities). Such behavioral changes could have been associated with social capital, thus influencing estimates associations. A second limitation of our study is that, in the absence of data at the county level on interpersonal trust, our measure of cognitive social capital remains a crude proxy for the norms of trust and reciprocity that characterize different communities and findings should therefore be interpreted in this light. It is possible that broader measures of cognitive social capital that better capture the contribution of cognitive aspects of social capital to long-term behavioral changes that reduce COVID-19 transmission and fatality could yield different results. Finally, our analyses are descriptive and cannot be used to prove causality but, rather, identify if the differences in the outcomes experienced by different counties with similar socio-demographic and economic profiles were systematically related to the levels of cognitive and relational social capital existing in such counties.

7. Discussion and implications

In the early months of the pandemic, a number of empirical studies examined social capital differentials in COVID-19 transmission, fatality and behaviors that could halt disease spread, such as mobility. Results from the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic broadly corresponding to the period between January 2020 and June 2020, generally indicated that communities with higher levels of social capital fared better than communities with lower levels of social capital: they experienced fewer deaths (Bartscher et al., 2020) and individuals in these communities modified their behaviors in ways that were more in line with public health recommendations (Borgonovi and Andrieu, 2020; Ding et al., 2020; Durante et al., 2021). However, the COVID-19 pandemic did not last just a few months in 2020 and required the adoption of long-term responses and sustained behavioral changes over a long time, in different seasons, changing sanitary conditions, economic and social circumstances.

Our work maps the evolution of the association between relational and cognitive social capital and COVID-19 deaths and hospitalizations between January 2020 and January 2021 in the United States. It suggests that relations changed markedly over time and that such evolution differed across the two indicators of social capital used in our analyses. In particular, while both relational and cognitive social capital were associated with lower deaths in the period in which the seriousness of the health risks associated with the pandemic was first established, spring 2020, cognitive social capital was not associated with a sustained lower death toll beyond this first period. By contrast, for the majority of 2020, communities with higher levels of relational social capital experienced lower deaths due to COVID-19 than communities with lower levels of relational social capital, although differences became progressively less pronounced over time.

Relational and cognitive social capital appear to have enabled communities to respond promptly to the threat posed by the pandemic in late February and early March 2020, especially in the early phase when sheltering in place regulations were not yet enacted. In this initial phase, both cognitive and relational social capital potentially led to a faster spread of information on the virus, leading to more accurate risk perceptions (Niepl, Kranz, Borgonovi, Valentin & Greiff, 2020) and, in turn, to the rapid adoption of behavioral changes that could have led to lower infections and fatality, such as the necessity of shielding at-risk groups or maintaining social distance. However, over time, other things being equal, both components of social capital were less strongly associated with an advantage in access to information, as information (and misinformation) about the virus became widely shared.

Over time, what distinguished communities in terms of the progression of deaths and hospitalizations and, as a result, the cumulative toll of the pandemic in the first year, was the capacity of citizens to sustain behaviors that reduced COVID-19 transmission and fatality over many months. In this context, what became important to reduce the toll of the pandemic was the capacity of individuals to engage in sustained efforts rather than their willingness to engage in one-off acts leading to immediate positive outcomes. In this prolonged status of emergency, our analyses reveal a long-lasting benefit for communities in which individuals before the pandemic engaged in sustained and effortful actions directed at promoting the public good, as indicated by their involvement in community initiatives and associations. By contrast, our indicator of cognitive social capital – which measures individuals’ willingness to participate in a one-off act, voting in the presidential election – was not equally associated with a sustained reduction in COVID-19 deaths (and hospitalizations). In fact, other things being equal, the indicator of cognitive social capital was associated with an increase in COVID-19 deaths (and hospitalizations) in the last months of 2020 and in early 2021.

Although in our work we classify the two indicators of social capital according to the extent to which they emphasize the existence of social networks or norms of reciprocity, it is possible that the distinctive associations that we observe in our analyses are due primarily to the extent to which the two indicators serve as proxies for ability to engage in active, sustained effort aimed at promoting the well-being of the community. The fact that we observe a reversal rather than simply attenuation of the association between the indicator of cognitive social capital that we use and COVID-19 deaths at the end of 2020 and in early 2021 deserves further scrutiny. The indicator of cognitive social capital that we use, voting in the presidential election, captures, in part, trust in the political process and institutions. It is possible that lack of institutional trust, other things being equal, might have led individuals to take additional protective measures compared to the measures recommended or mandated by local or national authorities in a period of rapid viral spread. Further research could attempt to investigate further this finding.

As the pandemic enters its second year, its impact on the health of communities in the United States, and beyond, will importantly depend on their ability to adopt behaviors that reduce infections and protect the most vulnerable in a sustained way (Van Bavel et al., 2020). Long-term behavioral changes will need to be accompanied by extensive testing, strict monitoring and periods of tighter restrictions to avoid exponential increases in cases when clusters of new infections are detected (Dave, Friedson, Matsuzawa & Sabia, 2020) and the rapid vaccination of vulnerable populations.

The progression of the pandemic with the emergence of new variants and vaccination campaigns means that communities will continue to be mobilized on an even greater number of fronts than in the first phase, despite high levels of stress and fatigue. They will have to continue reducing disease spread, caring for those infected, but will also be involved in the administration of large-scale vaccination campaigns. Many of the reasons that made relational social capital important in 2020 are likely to make it important also in 2021, but our work suggests that it is critical to re-evaluate the influence of specific social determinants of health when conditions change. Strong social ties and norms of reciprocity could continue to facilitate the spread of information on the need for individuals to vaccinate, the development of adequate distribution and administration plans to ensure the speedy and effective immunization of populations, and buy-in from local populations on prioritization protocols determining who should be offered vaccines as they become available. Our work suggests that if and when scientific knowledge will evolve, prompt behavioral changes can greatly influence the health of communities but also, and crucially, that social capital can play an especially important role in promoting information exchange and knowledge mobilization.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank anonymous reviewers for very useful suggestions on a previous version of this manuscript. Francesca Borgonovi acknowledges support from the British Academy through its Global Professorship scheme. The views expressed reflect those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the British Academy. The authors would like to thank Mattia Sassi for help with the data. 4JS.

Footnotes

Definitions of the county typology codes are available at: https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/county-typology-codes/documentation/.

Due to the log transformation of our dependent variable, figures in Table 2 should be interpreted the following way: exp(-0.94) = 0.39, meaning that a one standard deviation difference in relational social capital is associated with multiplying the cumulative deaths (31 January 2021) by a factor of 0.39, or in other words, a decrease of 60%. We perform similar calculations for the other coefficients.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.113948.

Credit author statement

FB designed the study and drafted the manuscript, EA performed the analyses, SS provided input on the design of the study and contributed to drafting the manuscript.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Aguilar J.B., Faust J.S., Westafer L.M., Gutierrez J.B. medRxiv; 2020. Investigating the Impact of Asymptomatic Carriers on COVID-19 Transmission. 2020.03.18.20037994. [Google Scholar]

- Arons M.M., Hatfield K.M., Reddy S.C., Kimball A., James A., Jacobs J.R., et al. Presymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections and transmission in a skilled nursing facility. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382(22):2081–2090. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2008457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai Y., Yao L., Wei T., et al. Presumed asymptomatic carrier transmission of COVID-19. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2020;323:1406–1407. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bargain O., Aminjonov U. IZA Institute of Labor Economics; Bonn: 2020. Trust and Compliance to Public Health Policies in Times of COVID-19. IZA DP No. 13205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrios J.M., Benmelech E., Hochberg Y.V., Sapienza P., Zingales L. University of Chicago, Becker Friedman Institute for Economics Working; 2020. Civic Capital and Social Distancing during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Paper No. 2020-74. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bartscher A.K., Seitz S., Siegloch S., Slotwinski M., Wehrhöfer N. IZA Institute of Labor Economics; Bonn: 2020. Social Capital and the Spread of COVID-19: Insights from European Countries. IZA DP No. 13310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Béraud G., Kazmercziak S., Beutels P., et al. The French connection: the first large population-based contact survey in France relevant for the spread of infectious diseases. PloS One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0133203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgonovi F., Andrieu E. Bowling together by bowling alone: social capital and COVID-19. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020;265:113501. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen T., Wu D., Chen H., et al. Clinical characteristics of 113 deceased patients with coronavirus disease 2019: retrospective study. BMJ. 2020;368:m1091. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang Y.C., Huang Y.L., Tseng K.C., et al. Social capital and health-protective behavior intentions in an influenza pandemic. PloS One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0122970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman J. Harvard University Press; Cambridge: 1998. Foundations of Social Theory. [Google Scholar]

- Ding W., Levine R., Lin C., Xie W. 2020. Social Distancing and Social Capital: Why U.S. Counties Respond Differently to COVID-19. NBER WP #27393. [Google Scholar]

- Dowd J.B., Andriano L., Brazel D.M., et al. Demographic science aids in understanding the spread and fatality rates of COVID-19. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. Unit. States Am. 2020;117(18):9696–9698. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2004911117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durante R., Guiso L., Gulino G. Asocial capital: civic culture and social distancing during COVID-19. J. Publ. Econ. 2021;194:104342. doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuyama F. 2000. Social Capital and Civil Society. IMF Working Paper No. 00/74.https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2016/12/30/Social-Capital-and-Civil-Society-3547 Available online at: June 1st 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Guiso L., Sapienza P., Zingales L. In: Benhabib J., Bisin A., Jackson M., editors. vol. 1. Elsevier; 2011. Civic capital as the missing link; pp. 417–480. (Handbook of Social Economics). [Google Scholar]

- Hale T., et al. Blavatnik School of Government; 2020. Variation in US States' Responses to COVID-19. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan R.E., Adab P., Cheng K.K. COVID-19: risk factors for severe disease and death. BMJ. 2020;368:m1198. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawachi I., Subramanian S.V., Kim D. Social Capital and Health. Springer; New York: 2008. Social capital and health: a decade of progress and beyond; pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Leung K., Jit M., Lau E., et al. Social contact patterns relevant to the spread of respiratory infectious diseases in Hong Kong. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:7974. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-08241-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q., Guan X., Wu P., et al. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:1199–1207. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin L., Savoia E., Agboola F., et al. What have we learned about communication inequalities during the H1N1 pandemic: a systematic review of the literature. BMC Publ. Health. 2014;14:1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linton N.M., et al. Incubation period and other epidemiological characteristics of 2019 novel coronavirus infections with right truncation: a statistical analysis of publicly available case data. J. Clin. Med. 2020;9(2):538. doi: 10.3390/jcm9020538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mossong J., Hens N., Jit M., et al. Social contacts and mixing patterns relevant to the spread of infectious diseases. PLoS Med. 2008;5:381–391. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niepel C., Kranz D., Borgonovi F., et al. Coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) the coronavirus (COVID‐19) fatality risk perception of US adult residents in March and April 2020. B. J. H. Psych. 10 June. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Oster E. Boston College Department of Economics; 2013. PSACALC: Stata Module to Calculate Treatment Effects and Relative Degree of Selection under Proportional Selection of Observables and Unobservables. Statistical Software Components S457677. Revised 18 Dec 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Oster E. Unobservable selection and coefficient stability: theory and evidence. J. Bus. Econ. Stat. 2019;37(2):187–204. doi: 10.1080/07350015.2016.1227711. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Putnam R.D. Princeton Princeton University Press; 1993. Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam R.D. New York Simon and Schuster; 2000. Bowling Alone the Collapse and Revival of American Community. [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers J., Valuev A.V., Hswen Y., et al. Social capital and physical health: an updated review of the literature for 2007–2018. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019;236:112360. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rönnerstrand B. Social capital and immunization against the 2009 A(H1N1) pandemic in the American States. Publ. Health. 2014;128:709–715. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2014.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rönnerstrand B. Contextual generalized trust and immunization against the 2009 A(H1N1) pandemic in the American states: a multilevel approach. SSM – Popul. Heal. 2016;2:632–639. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2016.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rupasingha A., Goetz S.J., Freshwater D. The production of social capital in US counties. J. Soc. Econ. 2006;35 83–10. [Google Scholar]

- Savoia E., Lin L., Viswanath K. Communications in public health emergency preparedness: a systematic review of the literature. Biosecur. Bioterrorism Biodefense Strategy, Pract. Sci. 2013;11:170–184. doi: 10.1089/bsp.2013.0038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens K.K., Rimal R.N., Flora J.A. Expanding the reach of health campaigns: community organizations as meta-channels for the dissemination of health information. J. Health Commun. 2004;9:97–111. doi: 10.1080/10810730490271557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szreter S., Woolcock M. Health by association? Social capital, social theory, and the political economy of public health. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2004;33(4):650–667. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Bavel J.J., Baicker K., Boggio P.S., et al. COVID-19 pandemic response. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2020:1–12. doi: 10.1038/s41562-020-0884-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viswanath K., Steele W.R., Finnegan J.R. Social capital and health: civic engagement, community size, and recall of health messages. Am. J. Publ. Health. 2006;96:1456–1461. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.029793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Klepac P., Read J., et al. Patterns of human social contact and contact with animals in Shanghai, China. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:15141. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-51609-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou F., Yu T., Du R., et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.