Abstract

Lipomatous pseudohypertrophy of the pancreas is a rare disease with unknown etiology, and the pancreas parenchyma is replaced by pancreatic parenchyma by fat tissue. In this article, we aimed to report the case of a 26-year-old male patient admitted to hospital with loss of appetite for 6 months. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans showed diffuse enlargement and fatty replacement over the whole pancreas, with scattered remnants of pancreatic parenchyma. Histologic results defined lipomatous pseudohypertrophy of the pancreas. To summarize, this case report is to put forward this extremely rare presentation and to sensitize clinicians that this entity can be a cause of exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, which requires patient follow-up for the appropriate treatment.

Keywords: Lipomatous pseudohypertrophy, Pancreas, Pancreas lipomatosis

Introduction

Lipomatous pseudohypertrophy of the pancreas (LPH) is an extremely rare disease, characterized by pancreatic enlargement due to the replacement of pancreatic acinar cells with adipose tissue, although the pancreatic ductal system and islets of Langerhans are preserved [1,2]. LPH has been reported by several studies [3–6], in which the LPH patients did not present obesity, diabetes mellitus, or chronic pancreatitis. Some rare childhood syndromes have been associated with LPH, such as Shwachman-Diamond [7,8], Bannayan [9], and Johanson-Blizzard [10] syndromes. Here we intended to report an extremely rare case of LPH in a young man.

Case report

A 26-year-old Vietnamese male patient presented with discomfort in the epigastric region and loss of appetite for 6 months. No history of fever, weight loss, acute abdominal pain, alcoholism or diabetes mellitus was reported, and his familial history was normal. At the time of admission, his height was recorded as 156 cm, weight as 44 kg, and body mass index as 18 kg/m2. Physical examination revealed a large, palpable mass in the right abdomen. Serum pancreatic amylase and lipase levels on admission were normal, at 69 and 116 U/L, respectively. Hematology and serum chemistry analyses revealed normal levels of white blood cells, platelets, red blood cells, total protein, albumin, hepatobiliary enzymes, and glycemia. Serum total cholesterol, low–density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), and triglyceride levels were slightly increased, at 250 mg/dL, 140 mg/dL, and 167 mg/dL, respectively compared with the normal ranges of less than 200 mg/dL, 130 mg/dL, and 150 mg/dL. The high–density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) level was within the normal range of 40-60 mg/dL [11]. An abdominal ultrasound revealed a large hyperechoic mass (measuring 20 × 13cm2) in the normal anatomic site of the pancreas, compressing the duodenum (Fig. 1). On computed tomography (CT) scan, the axial unenhanced images showed a diffusely enlarged pancreas compressing the duodenum and displacing the small bowel anteriorly. Pancreatic density was heterogeneous, with most of the head, body, and tail of the pancreas replaced with low-attenuation, hypodense, fatty-like tissue (Fig. 2). On contrast-enhanced images, the remaining pancreatic parenchyma was present and enhanced. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was also performed, revealing that the pancreas was well-circumscribed and diffusely enlarged. T2-weighted MRI results showed high signal intensity in the pancreatic parenchyma (Fig. 3). The pancreatic parenchyma was hyperintense on T1-weighted phase images, but some regions showed the loss of signal intensity on opposed–phase T1W images compared with in–phase images (Fig. 4). The preserved pancreatic parenchyma of the pancreas was enhanced (Fig. 5) and hypointense on diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI), with similar apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) value of 0.94 × 10−3 mm2/s as the spleen (Fig. 6). Therefore, the imaging analysis suggested that the preserved pancreatic parenchyma was normal.

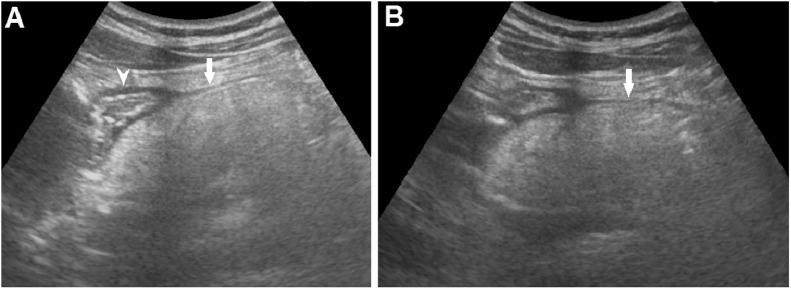

Fig. 1.

Abdominal ultrasound showing that the normal pancreas was replaced with a hyperechoic and well-defined border mass (A and B) (arrow), which compressed the duodenum (A) (arrowhead).

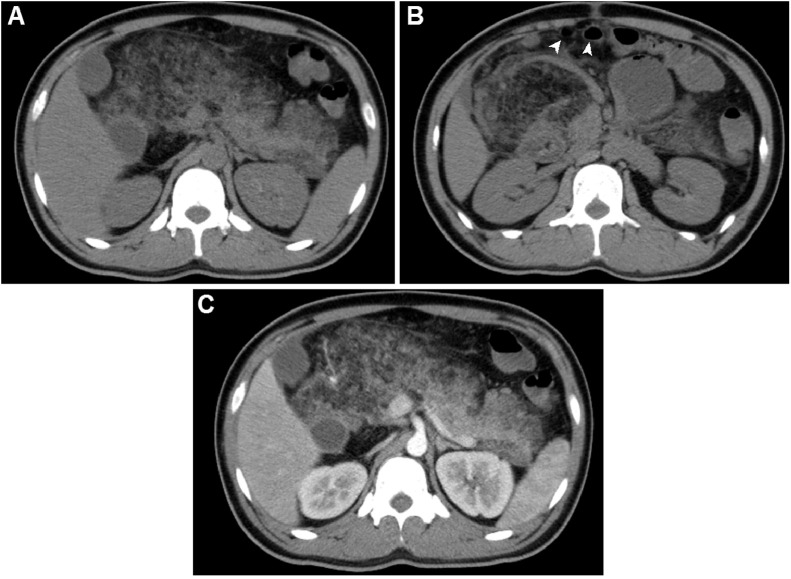

Fig. 2.

Abdominal CT scans. (A and B) CT scans, pre-contrast, revealed that the pancreas was enlarged, well-circumscribed, and replaced with low-density fat tissue. (C) CT scans, post-contrast, showed that the normal parenchyma enhanced. The largest diameter was observed in the head, at 135 mm, and the length of the pancreas was 220 mm. The small bowel had been displaced anteriorly (arrowhead).

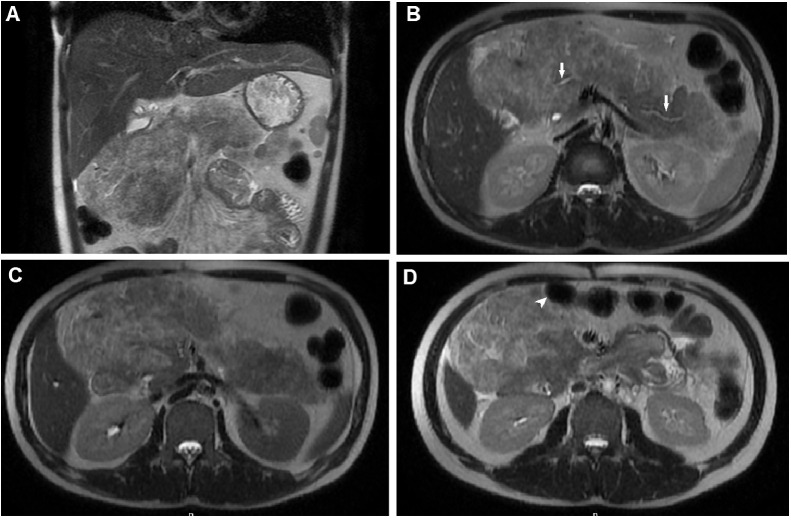

Fig. 3.

T2-weighted MRI. T2-weighted coronal (A) and T2-weighted axial (B, C and D) images showed that the pancreas was enlarged and well-circumscribed and the parenchymal signal was heterogeneous, with several hyperintense areas. The main pancreatic duct was normal (B) (arrow). The pancreas displaced the small bowel anteriorly (D) (arrowhead).

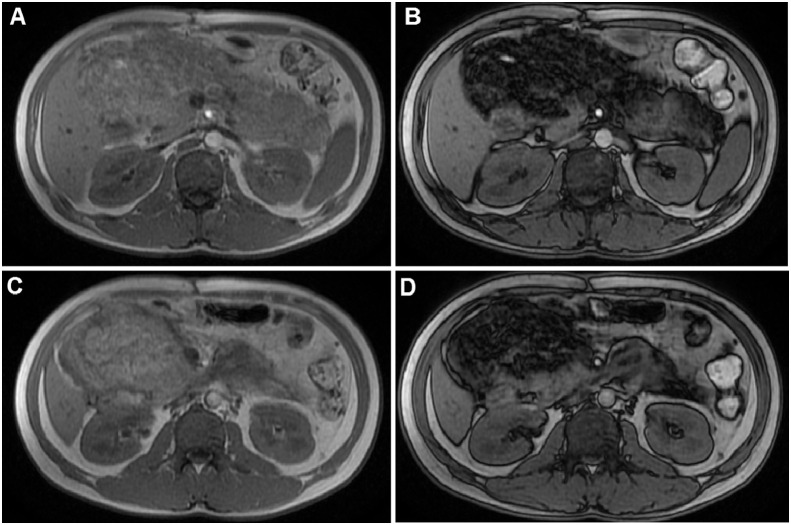

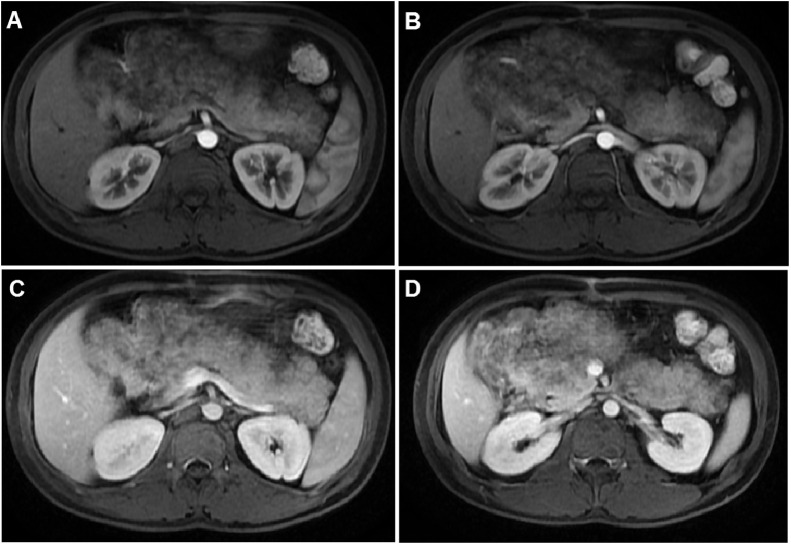

Fig. 4.

T1-weighted MRI. (A and C) In-phase T1-weighted images showed that the pancreas was enlarged with heterogeneous, with high signal intensity. (B and D) Opposed-phase T1-weighted images showed that parts of the parenchyma lost signal intensity due to adipose tissue replacement.

Fig. 5.

T1-weighted MRI with contrast on arterial (A and B) and venous phases (C and D) displayed the enhancement of preserved normal parenchyma; fat tissue was unenhanced.

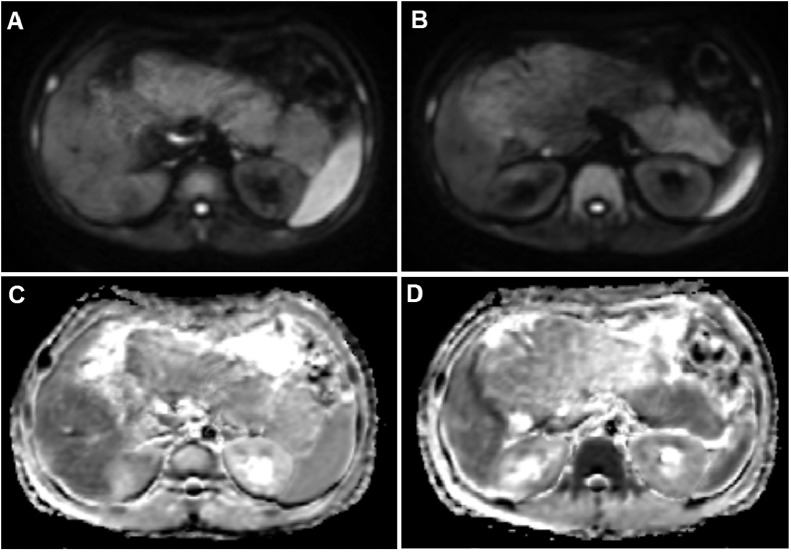

Fig. 6.

Diffusion-weighted imaging (A and B) and ADC map imaging (C and D) showed that the pancreatic parenchyma was hypointense on diffusion-weighted images and had similar ADC values as the spleen.

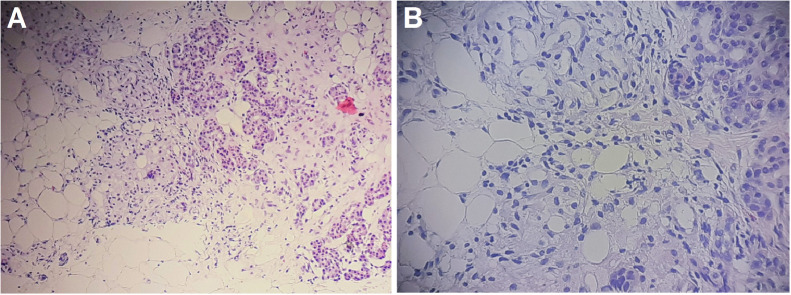

To obtain a definitive diagnosis, a percutaneous core biopsy was performed on this patient under ultrasound guidance. The histologic features showed the diffuse replacement of normal pancreatic parenchymal tissue with mature adipose tissue, and the pancreatic acini showed a scattered distribution. The pancreatic ductal system remained intact, and no regions of atypia, fibrosis, or fat necrosis were observed on histology (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Microscopic images of the pancreas, visualized with hematoxylin and eosin (HE) stain. (A) HE staining, ×100. (B) HE staining, ×200. The pathological examination revealed the diffuse replacement of the normal pancreatic parenchyma with mature adipose tissue. Scattered, residual pockets of normal pancreatic acinar cells were observed. The pancreatic ductal system remained intact.

Based on these clinical and imaging features, combined with the pathologic findings, the final diagnosis for this patient was LPH of the pancreas. Because pockets of the pancreatic parenchyma were preserved, pancreatic exocrine and endocrine functions were maintained. The patient was not treated with digestive enzymes but was discharged from the hospital, and asked to follow up regularly.

Discussion

Lipomatous pseudohypertrophy is a rare disease that was first reported by Hantelmann in 1931 [1]. A literature search of the PubMed database, performed by Deniz Altinel (2010), revealed only 37 other cases, worldwide, including cases that were diagnosed by imaging alone [3–6,[12], [13], [14], [15].

The exact etiology of LPH remains unknown, although various hypotheses have been suggested, including parenchymal atrophy due to ductal obstruction, viral infection, toxin exposure, and congenital anomalies [3–6,[12], [13], [14], [15]. Siegler described this disease as being characterized by (1) an increase in pancreatic size and weight, (2) the near-complete absence of pancreatic exocrine tissue, with the concomitant replacement of pancreatic tissue with normal adipose tissue, and (3) the preservation of pancreatic ducts and islets of Langerhans [2]. LPH can occur in all age groups, with reported patients ranging from 6 days-80 years in age [16,17]. LPH is characterized by pancreatic enlargement, with diameters as high as 24 cm [3]. Although the rate of growth and the timeline of fat replacement remain unknown, the condition is believed to take several years to develop [5]. LPH is typically considered to be a benign disease; however, some cases have been associated with cholangiocarcinoma of common bile duct [13], squamous cell carcinoma [18], leiomyosarcoma [19], and carcinoma [20,21].

Several methods can be used to evaluate the pancreas in patients with this disease. Ultrasonography can be used to identify this entity, which appears as an enlarged hyperechoic, hyper–reflective pancreas; however, the application of ultrasonography for diagnosis is very limited. In contrast, CT and MRI both play important roles in the evaluation of the pancreas. CT scans revealed pancreatic enlargement and intra–parenchymal fat attenuation. Post–contrast images could be used to differentiate between the surrounding normal, enhanced parenchyma and adipose tissue. MRI showed adipose tissues with high signal intensity on T1- and T2-weighted images, which can be suppressed by the application of fat-suppression techniques. Fatty replacement occurs over the entire pancreas, and a netlike structure can be observed due to the residual vessels in the pancreas [6,12]. Though the replacement of normal pancreatic parenchymal tissue with mature adipose tissue, the preserved pancreatic parenchyma was normal and the ADC value was within the normal limitation. On magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) images, the normal duct system of the pancreas is visible [15]. Some differential diagnoses for the suspicious imaging findings were pancreatic fatty infiltration, cystic fibrosis, pancreatic lipoma, Shwachman-Diamond, Bannayan, and Johanson-Blizzard syndromes.

The macroscopic appearance showed that the pancreas was enlarged and well-circumscribed. On histology, the pancreatic parenchyma was replaced with adipose tissue, without fibrosis or fat necrosis. The islets of Langerhans remained relatively well-preserved. Well-differentiated liposarcoma is the primary differential diagnosis for LPH [22,23]. To obtain a definitive LPH diagnosis, LPH must be distinguished from pancreatic fat infiltration, due to other etiologies such as pancreatic carcinoma or liposarcoma. Because LPH is considered to be a benign disorder, the patient should be managed with regular follow-up. When symptoms of pancreatic exocrine functional insufficiency are present, digestive enzymes, including pancreatic enzymes, are administered. However, some patients have undergone surgical resection due to malignant preoperative diagnoses, pancreatitis, or mass effect [3,5].

In our case, CT and MRI scans showed pancreatic enlargement and fat infiltration. Because LPH is a rare disease, the data reported in the literature primarily discuss the findings from CT scans and MRI, particularly T1-weighted and T2–weighted imaging; however, we report the results of DWI analysis. The largest diameter was observed in the pancreatic head, at 135 mm, and the length of the pancreas was 220 mm. A biopsy was performed, which not only confirmed the diagnosis but also excluded malignancy, although this disease is typically diagnosed by imaging alone [4]. The patient retained residual pockets of normal pancreatic parenchyma, allowing for the maintenance of pancreatic exocrine function. However, because of the enlarged pancreas, especially in the region head, the bowel was compressed, leading to the patient's discomfort. We gave him advice regarding lifestyle modifications, particularly adherence to a balanced diet and the avoidance of fatty foods.

Conclusion

Lipomatous pseudohypertrophy (LPH) is a very rare disease, and the clinical presentation of LPH can vary, accompanied by different signs and symptoms. By the time that symptoms associated with malabsorption emerge, LPH is likely to be in a very late stage. CT and MRI assessments, including MRCP, are easy, reliable, safe, and effective methods for establishing the diagnosis. Digestive enzyme supplementation is the current gold standard of treatment.

Ethical statement

Appropriate written informed consent was obtained for publication of this case report and accompanying images.

Author contributions

Vu DL and Nguyen MD contributed to this article as co-first authors. All authors have read the manuscript and agree to the contents.

Patient consent

Informed consent for patient information to be published in this article was obtained.

Footnotes

Acknowledgments: Self-financed.

Competing interests: The authors do not report any conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Hantelmann W. Fettsucht und Atrophie der Bauchspecicheldruse bei Jungendlichen. Virchows Arch. 1931;282:630–642. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegler D.I. Lipomatous pseudohypertrophy of the pancreas associated with chronic pulmonary suppuration in an adult. Postgrad Med J. 1974;50(579):53–55. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.50.579.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Altinel D., Basturk O., Sarmiento J.M., Martin D., Jacobs M.J., Kooby D.A. Lipomatous pseudohypertrophy of the pancreas: a clinicopathologically distinct entity. Pancreas. 2010;39:392–397. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181bd2923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yasuda M., Niina Y., Uchida M., Fujimori N., Nakamura T., Oono T. A case of lipomatous pseudohypertrophy of the pancreas diagnosed by typical imaging. Jop. 2010;11(4):385–388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shimada M., Shibahara K., Kitamura H., Demura Y., Hada M., Takehara A. Lipomatous pseudohypertrophy of the pancreas taking the form of huge massive lesion of the pancreatic head. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2010;4(3):457–464. doi: 10.1159/000321989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Masuda A., Tanaka H., Ikegawa T., Matsuda T., Shiomi H., Takenaka M. A case of lipomatous pseudohypertrophy of the pancreas diagnosed by EUS-FNA. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2012;5(4):282–286. doi: 10.1007/s12328-012-0318-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.MacMaster S.A., Cummings T.M. Computed tomography and ultrasonography findings for an adult with Shwachman syndrome and pancreatic lipomatosis. Can Assoc Radiol J. 1993;44(4):301–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bom E.P., van der Sande F.M., Tjon R.T., Tham, A., Hillen H.F. Shwachman syndrome: CT and MR diagnosis. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1993;17(3):474–476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Okumura K., Sasaki Y., Ohyama M., Nishi T. Bannayan syndrome–generalized lipomatosis associated with megalencephaly and macrodactyly. Acta Pathol Jpn. 1986;36(2):269–277. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.1986.tb01479.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maunoury V., Nieuwarts S., Ferri J., Ernst O. Pancreatic lipomatosis revealing Johanson-Blizzard syndrome. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1999;23(10):1099–1101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults. Executive summary of the third report of the national cholesterol education program (ncep) expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) JAMA. 2001;285(19):2486–2497. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.19.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Izumi S., Nakamura S., Tokumo, M., Mano S. A minute pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma with lipomatous pseudohypertrophy of the pancreas. JOP. 2011;12(5):464–468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jayatunge S.P., Mahendra G., Siyabalapitiya S., Siriwardana R.C., Liyanage C. Total pancreatectomy for cholangiocarcinoma of the distal common bile duct associated with lipomatous pseudohypertrophy of pancreas. J Hepatobilliary Pancreatic Dis. 2015;5(1):30–34. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nema D., Arora S., Mishra A. Lipomatous pseudohypertrophy of pancreas with coexisting chronic calcific pancreatitis leading to malabsorption due to exocrine pancreatic insufficiency. Med J. 2016;72(Suppl 1):S213–S216. doi: 10.1016/j.mjafi.2016.08.001. Armed Forces India. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baleato-González S., Vieira Leite C., García-Figueiras R. The morphological and functional diagnosis of a rare entity: lipomatous pseudohypertrophy of the pancreas. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2018;110(3):207. doi: 10.17235/reed.2018.5367/2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lumb G., Beautyman W. Hypoplasia of the exocrine tissue of the pancreas. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1952;64(4):679–686. doi: 10.1002/path.1700640402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuroda N., Okada M., Toi M., Hiroi M., Enzan H. Lipomatous pseudohypertrophy of the pancreas: further evidence of advanced hepatic lesion as the pathogenesis. Pathol Int. 2003;53(2):98–101. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1827.2003.01437.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bralet M.P., Terris B., Brégeaud L., Ruszniewski P., Bernades P., Belghiti, J. Squamous cell carcinoma and lipomatous pseudohypertrophy of the pancreas. Virchows Arch. 1999;434(6):569–572. doi: 10.1007/s004280050385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shimizu M., Hirokawa M., Matsumoto T., Iwamoto S., Manabe T. Fatty replacement of the pancreatic body and tail associated with leiomyosarcoma of the pancreatic head. Pathol Int. 1997;47(9):633–636. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.1997.tb04554.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Salm. R. Scirrhous adenocarcinoma arising in a lipomatous pseudohypertrophic pancreas. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1960;79:47–52. doi: 10.1002/path.1700790106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salm R. Carcinoma arising in a lipomatous pseudohypertrophic pancreas. Br Med J. 1968;3(5613)):293. doi: 10.1136/bmj.3.5613.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Milano C., Colombato L.A., Fleischer I., Boffi A. Liposarcoma of the pancreas. Report of a clinical case and review of the literature. Acta Gastroenterol Latinoam. 1988;18(2):133–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elliott T.E., Albertazzi V.J., Danto L.A. Pancreatic liposarcoma: case report with review of retroperitoneal liposarcomas. Cancer. 1980;45(7):1720–1723. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19800401)45:7<1720::aid-cncr2820450733>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]