Abstract

Introduction

It is essential to determine the interactions between viruses and mosquitoes to diminish dengue viral transmission. These interactions constitute a very complex system of highly regulated pathways known as the innate immune system of the mosquito, which produces antimicrobial peptides that act as effector molecules against bacterial and fungal infections. There is less information about such effects on virus infections.

Objective

To determine the expression of two antimicrobial peptide genes, defensin A and cecropin A, in Aedes aegypti mosquitoes infected with DENV-1.

Materials and methods

We used the F1 generation of mosquitoes orally infected with DENV-1 and real-time PCR analysis to determine whether the defensin A and cecropin A genes played a role in controlling DENV-1 replication in Ae. aegypti. As a reference, we conducted similar experiments with the bacteria Escherichia coli.

Results

Basal levels of defensin A and cecropin A mRNA were expressed in uninfected mosquitoes at different times post-blood feeding. The infected mosquitoes experienced reduced expression of these mRNA by at least eightfold when compared to uninfected control mosquitoes at all times post-infection. In contrast with the behavior of DENV-1, results showed that bacterial infection produced up-regulation of defensin and cecropin genes; however, the induction of transcripts occurred at later times (15 days). Conclusion: DENV-1 virus inhibited the expression of defensin A and cecropin A genes in a wild Ae. aegypti population from Venezuela.

Key words: Aedes aegypti, dengue virus, alpha-defensins, cecropins, Escherichia coli

Abstract

Introducción

Es esencial determinar las interacciones entre los virus y los mosquitos para disminuir la transmisión viral. Estas interacciones constituyen un sistema muy complejo y muy regulado conocido como sistema inmunitario innato del mosquito, el cual produce péptidos antimicrobianos, moléculas efectoras que funcionan contra las infecciones bacterianas y fúngicas; se tiene poca información de su acción sobre los virus.

Objetivo

Determinar la expresión de dos genes AMP (defensina A y cecropina A) en mosquitos Aedes aegypti infectados con el virus DENV-1.

Materiales y métodos

Se infectaron oralmente mosquitos de generación F1 con DENV-1 y mediante el análisis con PCR en tiempo real se determinó el potencial papel de los genes defensina A y cecropina A en el control de la replicación del DENV-1 en Ae. aegypti. Como referencia, se infectaron mosquitos con Escherichia coli.

Resultados

Los mosquitos no infectados expresaron niveles basales de los ARNm de los genes defensina A y cecropina A en diversos momentos después de la alimentación. Los mosquitos infectados experimentaron una reducción, por lo menos, de ocho veces en la expresión de estos ARNm con respecto a los mosquitos de control en todo el periodo posterior a la alimentación. En contraste con el comportamiento del virus DENV-1, los resultados mostraron que la infección bacteriana produjo una regulación positiva de los genes defensina y cecropina; sin embargo, la inducción de los transcritos ocurrió tardíamente (15 días).

Conclusión

El virus DENV-1 inhibió la expresión de los genes defensina A y cecropina A en una población silvestre de Ae. aegypti en Venezuela.

Palabras clave: Aedes aegypti, virus del dengue, alfa-defensinas, cecropinas, Escherichia coli

In Venezuela, dengue is the most important arboviral disease affecting humans, and its incidence and prevalence rise annually (1). Until now, there is not a vaccine to avoid DENV infections and, therefore, vector control is the only way to restrain these disease risks (2).

Arboviruses such as DENV have to go through a series of critical steps that demand their interplay with different tissues, which lasts for days or weeks until transmission can occur (2-4). These tissues represent barriers that restrict virus growth through, among others, immune molecules with antipathogenic activity that belong to a very complex system of highly regulated pathways called the innate immune system of mosquitos. Toll, IMD, JAK/STAT, and RNAi are the primary immune signaling pathways (2-5).

Different strategies to diminish viral transmission have been considered, among them, the use of genetically engineered vectors and natural symbionts like Wolbachia (6,7). Any strategy to control dengue transmission should consider the interactions between viruses and mosquitoes, especially, their innate immune system.

Toll and IMD pathways produce effector molecules such as the antimicrobial peptides, low molecular-weight proteins well known for their action against bacterial and fungal infections, although there is less information regarding their effect on viral infections. Reports suggest that dengue virus infection is controlled by the toll pathway in mosquitoes (8) and that together with the IMD pathways they upregulate the Sindbis (9) and the DENV-2 viruses in mosquitoes (10,11). However, other studies have evidenced the inhibition of toll's innate immune response in salivary glands infected by DENV-2 with 3’UTR substitutions associated with high epidemiological fitness and enhanced production of infectious saliva (12).

In our study, we found that the expression of defensin A and cecropin A genes, two antimicrobial peptide genes mediated by the toll pathway, was significantly reduced in Ae. aegypti mosquitoes infected with DENV-1 suggesting that the infection progresses by suppressing the toll pathway.

Materials and methods

Mosquito collection

We collected Ae. aegypti mosquitoes as larvae from Maracay, Venezuela, and then obtained their F1 generation.

Dengue virus, bacteria, and infection processes

We used a DENV-1 isolate (LAR23644) recovered from a patient in Maracay in 2007 for the infection assays. Viruses were serially passaged in Ae. albopictus C6/36 cells, the infected supernatants were then harvested, titered via plaque-forming assay, and frozen at -80 °C. The viral titer was 4,8 x 105 PFU/ml. For oral infection experiments, we mixed viral stocks 1:1 with human red blood cells washed with PBS and fed to mosquitoes (sugar starved for 24 h) via membrane feeders. Some groups of mosquitoes were fed only on human red blood cells. Immediately post-feeding, fully engorged specimens were transferred to new cages held under standard rearing conditions and provided with sucrose.

At different times after feeding, ≈30 mosquitoes were collected each time. At early times (5 and 24 hours) we checked if the virus was inactivated by some antiviral defense mechanism present in the mosquitoes’ guts while at later times (10 and 15 days), we aimed at detecting viral replication in their bodies.

To determine the percentage of virus infection, dissemination, and potential transmission in the vector, 50 individual mosquitoes’ abdomen (fed with the virus similarly as before and collected 15 days later) were dissected to check for infection, their legs and wings for dissemination, and their salivary glands for potential transmission. It is known that the only way to measure transmission is by analyzing the saliva of the mosquitoes, for which the viruses in these last tissues are potentially transmittable (13). Prior to their lysis, all the tissues were washed three times with 200 μl of PBS to discard any contamination. Mosquitoes were stored at -80 °C.

Similar infections were carried out with E. coli cultured in OD600 0.8, pelleted, washed, and resuspended in PBS. The bacteria culture was mixed with human red blood cells in equal proportions, and then we applied the methodological procedure used for viral infection.

Detection and typing of dengue viruses in Aedes aegypti

RNA extraction, detection, and typing of dengue viruses in pools of whole bodies or in dissected samples of Ae. aegypti were performed according to Urdaneta, et al. (14).

Quantitative RT-PCR (qPCR) for measuring gene expression

Gene expression was determined by relative quantification relating the qPCR signal of the defensin A or cecropin A gene transcript in a mosquito group fed on virus or bacteria mixed with human red blood cells and that of a control group (calibrator) fed only on human red blood cells. qPCR was conducted in a reaction volume of 25 µl in a 96-well plate containing 0.5 µg of template based on the initial RNA concentration and 200 nM forward and reverse primers using real-time Go Taq qPCR™ (Promega Corporation, USA) on a 7500 Real-Time PCR System™ (Applied Biosystems, Massachusetts, USA) using the following program: 2 minutes of preincubation at 95 ºC followed by 40 30-s cycles at 95 ºC and one minute at 60 ºC. The designed specific primers used were: Defensin A gene (sense: 5’-AACTGCCGGAGGAAACCTAT-3’; antisense: 5’-TCTTGGAGTTGCAGTAACCT-3’) and cecropin A gene (sense: 5'-CGAAGTTATTTCTCCTGATCG-3'; antisense: 5'-AGCTACAACAGGAAGAGCC-3'). To normalize the data, we used the α-tubulin gene (sense: 5’-GCGTGAATGTATCTCCGTGC-3’; antisense: 5'-AGCTACAACAGGAAGAGCC-3') s an endogenous reference.

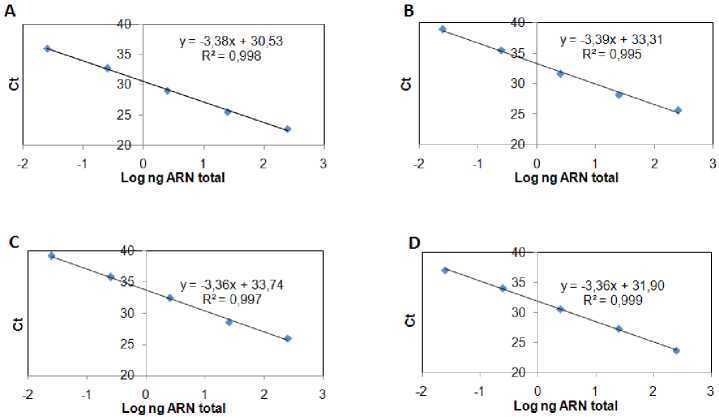

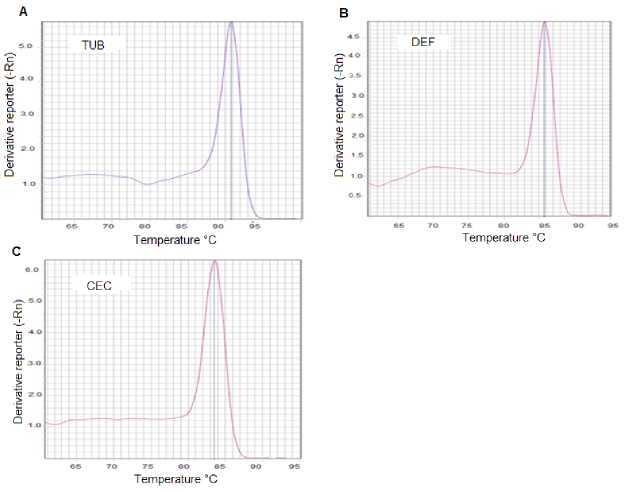

We assessed α-tubulin, defensin A, and cecropin A primer pairs and we found the following for each: The observed efficiency was near to 100% (figure 1S), the amplification specificity was displayed through the production of a unique peak in the melt-curve analysis (figure 2S), which was corroborated by sequencing the PCR products from each gene in both directions using the PCR primers (data not shown). The sequencing reactions were performed with the ABI PRISM BigDye Terminator™, version 3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit on an Applied Biosystems genetic analyzer, Model ABI 3130XL. Therefore, the 2-ΔΔCt method of relative quantification was used to appraise relative gene expression.

Figure 1S.

Efficiency of gene amplification. qPCR amplification efficiencies of α-tubulin, defensin A, and cecropin A genes. Each gene DNA was diluted in serial 10-fold ranges and the cycle threshold (Ct) value at each dilution was measured. The Ct represents the average of two independent experiments done by triplicate. Then, a curve was obtained for: a) α-tubulin, b) defensin A or c) cecropin A gene from which qPCR efficiencies (E) were assessed. The slopes of the curves were used to calculate E according to the equation: E = 10(-1/slope) - 1 × 100, where E = 100 corresponds to a 100% efficiency.

The amplification efficiencies obtained for the genes after applying the equation were:

A) α-tubulin gene, 97.3%

B) defensin A gene, 97.2%

C) cecropin A gene, 98.5%

Figure 2S.

DNA qPCR melting curve analysis for the detection of gene specificity. Three fragments, the first from the α-tubulin gene, the second from the defensin A, and the last from the cecropin A gene were synthesized by qPCR using specific primers for each gene. The resulting products were subjected to post-PCR melt analysis. Only one peak was detected with primers for A) α-tubulin gene; B) defensin A gene or C) cecropin A gene.

We used the control and virus-infected pool samples (≈30 mosquitoes/pool) at different times after feeding (5 h, 24 h, 10 days, and 15 days) in the qPCR reaction (a total of 8 pools: ≈240 mosquitoes). The control values were very close at all times, so we took their average as the calibrator. Each qPCR experiment was repeated three times with three replicates of each one. Similar experiments were carried out with E. coli. The average and standard deviation (SD) of the CTs from the three replicates were determined and the average was only approved if the SD was <0.38 (15). Repeatability and reproducibility were calculated by a percent coefficient of variance (% CV) within and between assays respectively (table 3S).

Table 3S. Repeatability of qPCR assay for defensin A gene in Escherichia coli-infected Aedes aegypti mosquitoes.

| Sample | Replicated runs (Ct) | Mean | SD | Repeatability (CV) |

% CV |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |||||

| Calibrator | 27 | 27.2 | 26.8 | 27.0 | 0.2 | 0.01 | 0.7 |

| 5 h | 25.4 | 25.7 | 25.4 | 25.5 | 0.2 | 0.01 | 0.7 |

| 24 h | 27.9 | 27.1 | 27.5 | 27.5 | 0.4 | 0.01 | 1.5 |

| 10 d | 25.9 | 26.9 | 26.6 | 26.5 | 0.5 | 0.02 | 1.9 |

| 15 d | 22.8 | 23.1 | 22.8 | 22.9 | 0.2 | 0.01 | 0.8 |

SD: standard deviation; CV: coefficient of variance

We calculated N-fold copy numbers of the Ae. aegypti defensin A and cecropin A gene transcripts relative to the control in each assay using geometric means for the three experiments.

Results

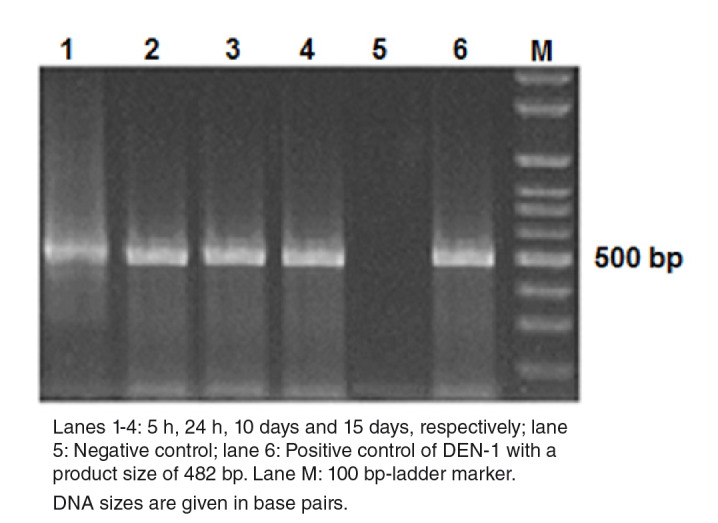

Stability and replication of DENV-1

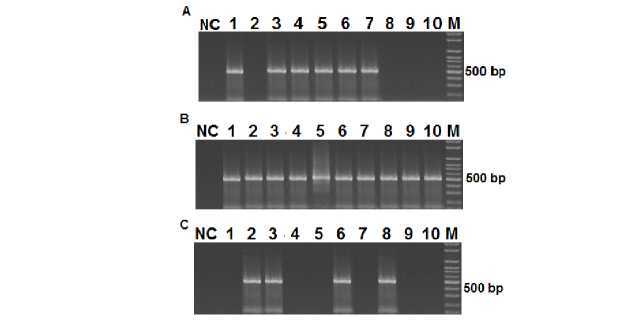

We determined whether the DENV-1 was stable at early post-infection (dpi) times (5 and 24 hours) and replicated at later ones (10 and 15 days) in the mosquitoes using RT-PCR amplification followed by agarose gel electrophoresis analysis of the products. Figure 1 shows the presence of DENV-1 with the cDNA band at the 482 bp position at all time points under study. The replication was further corroborated in the dissected samples of 50 individual mosquitoes with 70% and 100% viral infection and a dissemination efficiency 15 days post-infection. Regarding the virus present in the salivary glands, it also replicated (45%) and evidenced potential transmission efficiency (table 9S).

Figure 1.

Detection of DEN-1 in Aedes aegypti by gel electrophoresis on a 2% agarose gel. DNA amplicons generated by RT-PCR of the RNA extracted from dengue viruses in Aedes aegypti at different times post infection.

Lanes 1-4: 5 h, 24 h, 10 days and 15 days, respectively; lane 5: Negative control; lane 6: Positive control of DEN-1 with a product size of 482 bp. Lane M: 100 bp-ladder marker.

DNA sizes are given in base pairs.

Table 9S. Rates of infection, dissemination and potential transmission of the DENV-1 in Ae. aegypti mosquitoes.

| Infection (%)a Dissemination (%)b P. transmission (%)c |

|---|

| 70 (35/50) 100 (35/35) 45.7 (16/35) (p<0,01)* |

| a Rate of infection: Number with DENV virus-positive abdomens/number tested |

| b Rate of dissemination: Number with DENV virus-positive legs and wings/number with DEN |

| virus-positive abdomens |

| c Rate of potential transmission: Number with DENV virus-positive heads/number with DEN |

| virus-positive abdomens |

| * Open Epi Versión 3.03 (Dean AG, Sullivan KM, Soe MM. OpenEpi: Open Source |

| Epidemiologic Statistics for Public Health, Version. www.OpenEpi.com, updated 2013/04/06, |

| accessed 2020/04/03) was used for statistical analysis |

Inhibition of defensin and cecropin mRNA by DENV-1

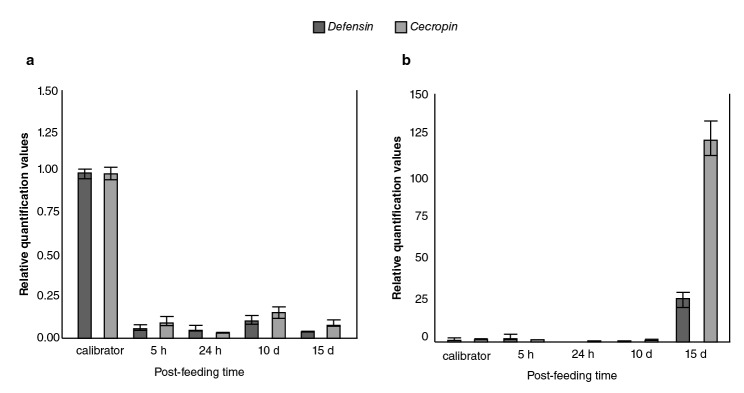

The relative expression levels of defensin A and cecropin A genes in DENV-1-infected Ae. aegypti mosquitoes as compared to the calibrator are shown in figure 2A with both mRNA detectable in control mosquitoes; however, a significant decrease in abundance occurred at all time points measured with at least five to eight-fold fewer amounts of defensin and cecropin mRNA, respectively, in mosquitoes infected with DENV-1.

Figure 2.

Comparison of immune responses to DENV-1 and Escherichia coli bacteria in field-collected Aedes aegypti. Averaged data from three independent real-time qPCR experiments were used to assess the expression of each of the selected immune genes in the Aedes aegypti mosquitoes infected with the DEN-1 virus (a) or Escherichia coli bacteria (b) with the host α-tubulin as an internal reference control to normalize the data. For each pathogen, the control values for both genes at all the time points were very similar. In every case, the average of all these values was used as the calibrator. The 2-ΔΔCT method was used to calculate fold change for each gene.

Induction of defensin and cecropin mRNA by bacteria

The response of the field population of Ae. aegypti mosquitoes to bacteria was contrary to the previously described viral response given that, as expected, the bacterial infection did not produce down-regulation in any of the genes (figure 2B); however, the induction of transcripts occurred at later times (15 days).

Discussion

There is a discrepancy regarding the reaction of mosquitoes’ immune system in the presence of DENV-1. The response may be stimulation (2,8,10,11) or suppression in vivo (9,16-18) and in vitro (19,20). Such discrepancy probably depends on the viral strain used, the genetic history of the vector, and the mode of transmission (3,21). We found a reduced expression of defensin A and cecropin A genes using the F1 generation of wild mosquitoes infected with DENV-1. Similar results were reported with DENV-2-infected field Ae. aegypti populations (6).

The specific molecular mechanism by which DENV acts remains uncharacterized. The virus may be able to knock down the expression of some factor needed to induce the expression of defensin and cecropin mRNA, similar to the role reported for the AeFaDD protein in Ae. aegypti (22). Alternatively, the DENV may directly target and inhibit the transcription of both genes.

The suppression of the innate immune responses of mosquitoes found in this study was time-independent contrary to other reports using similar times: 1, 2, 7, and 14 days (17), which implies that DENV may exert continuous immunomodulatory activity in mosquitoes, or for some period of time. This is critical for defining the vector competence of local mosquitoes, as well as dengue transmission intensity in a particular area.

As expected, the bacterial infection did not produce down-regulation of the defensin and cecropin genes (23,24); however, the induction of the transcripts occurred at later times (figure 2B). These data could indicate that the capacity of these wild Ae. aegypti mosquitoes to mount a highly effective production of defensin and cecropin to control invading bacteria would take the time probably required to inactivate bacterial growth factors.

In conclusion, DENV-1 inhibits the expression of defensin A and cecropin A genes in a wild Ae. aegypti population from Maracay city in Venezuela. The way the virus participates in this inhibitory mechanism and the viral effector molecules acting in it are still to be determined.

Acknowledgments

To Nancy Moreno for her critical reading of the manuscript; to Karem Flores and to the Dirección de Malariología y Saneamiento Ambiental staff in Maracay, Estado Aragua, Venezuela, for the collection and rearing of mosquitoes; to Daria Camacho for providing the virus strain, and to. Irene Bosch for assistance with the English language editing of this manuscript.

Supplementary files

(Figure 1S), (Figure 2S), (Figure 3S), (Table 1S), (Table 2S), (Table 3S), (Table 4S), (Table 5S), (Table 6S), (Table 7S), (Table 8S), (Table 9S)

Figure 3S.

Infection, Dissemination and Potential Transmission of DENV-1 in Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. Mosquitoes (50) were infected with DENV-1 (1.6 x 105 PFU/ml) and after 15 days, RNA was extracted from different tissues of individual mosquitoes and visualized using nested PCR followed by electrophoresis on a 2% agarose gel and SYBR Green staining. The 482 bp band corresponds to the DENV-1 amplification product from abdomens (A), wings and legs (B), and heads (C).

Table 1S. Repeatability of qPCR assay for defensin A gene in DEN 1-infected Aedes aegypti mosquitoes.

| Sample | Replicated runs (Ct) | Mean | SD | Repeatability |

% CV |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |||||

| Calibrator | 25.6 | 26.8 | 27.1 | 26.5 | 0.8 | 0.03 | 3.0 |

| 5 h | 31.5 | 32.4 | 31.6 | 31.8 | 0.5 | 0.02 | 1.5 |

| 24 h | 30.5 | 31.2 | 30.6 | 30.8 | 0.4 | 0.01 | 1.2 |

| 10 d | 31.8 | 31.5 | 31.8 | 31.7 | 0.2 | 0.01 | 0.5 |

| 15 d | 32.6 | 31.3 | 32.6 | 32.2 | 0.8 | 0.02 | 2.3 |

SD: standard deviation; CV: coefficient of variance

Table 2S. Repeatability of qPCR assay for cecropin A gene in DEN 1-infected Aedes aegypti mosquitoes.

| Sample | Replicated runs (Ct) | Mean | SD | Repeatability (CV) |

% CV |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |||||

| Calibrator | 23 | 24 | 22 | 23.0 | 1.0 | 0.04 | 4.3 |

| 5 h | 26.9 | 27.5 | 27.4 | 27.3 | 0.3 | 0.01 | 1.2 |

| 24 h | 29.2 | 29.5 | 29.2 | 29.3 | 0.2 | 0.01 | 0.6 |

| 10 d | 26.9 | 26.7 | 26.4 | 26.7 | 0.3 | 0.01 | 0.9 |

| 15 d | 28.7 | 28.8 | 28.8 | 28.8 | 0.1 | 0.00 | 0.2 |

Table 4S. Repeatability of qPCR assay for cecropin A gene in Escherichia coli-infected Aedes aegypti mosquitoes.

| Sample | Replicated runs (Ct) | Mean | SD | Repeatability (CV) |

% CV |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |||||

| Calibrator | 26 | 26 | 25 | 25.7 | 0.6 | 0.02 | 2.2 |

| 5 h | 24 | 25 | 24 | 24.3 | 0.6 | 0.02 | 2.4 |

| 24 h | 25.1 | 25.9 | 25.8 | 25.6 | 0.4 | 0.02 | 1.7 |

| 10 d | 24.8 | 25.3 | 25.3 | 25.1 | 0.3 | 0.01 | 1.1 |

| 15 d | 23.9 | 24 | 24.4 | 24.2 | 0.4 | 0.01 | 1.5 |

SD: standard deviation; CV: coefficient of variance

For all tables, the repeatability was calculated as the percent coefficient of variance (%CV) of Ct triplicate values of a sample within a single experiment.

Table 5S. Reproducibility of qPCR assay for defensin A gene in DEN 1-infected Aedes aegypti mosquitoes.

| Sample | Run (% CV) | Mean | SD | * Reproducibility run 1 ~ run 2 ~ run 3 (% CV) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||

| Calibrator | 3.0 | 2.8 | 2.9 | 2.9 | 0.10 | 0.034 |

| 5 h | 1.5 | 1.4 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 0.08 | 0.051 |

| 24 h | 1.2 | 1.4 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 0.11 | 0.084 |

| 10 d | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.08 | 0.155 |

| 15 d | 2.3 | 2.2 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 0.07 | 0.030 |

CV: coefficient of variance; SD: Standard deviation

For all tables, the reproducibility was calculated as the percent coefficient of variance (%CV) of Ct triplicate values of a sample between assays.

Table 6S. Reproducibility of qPCR assay for cecropin A gene in DEN 1-infected Ae. aegypti mosquitoes.

| Sample | Run (% CV) | Mean | SD | * Reproducibility run 1 ~ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | run 2 ~ run 3 (% CV) | |||

| Calibrator | 0.7 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.11 | 0.135 |

| 5 h | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.06 | 0.089 |

| 24 h | 1.5 | 1.4 | 1.6 | 1.5 | 0.10 | 0.070 |

| 10 d | 1.9 | 1.9 | 1.8 | 1.9 | 0.07 | 0.038 |

| 15 d | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.07 | 0.090 |

SD: standard deviation; CV: coefficient of variance; CV: coefficient of variance

Table 7S. Reproducibility of qPCR assay for defensin A gene in Escherichia coli-infected Ae. aegypti mosquitoes.

| Sample | Run (% CV) | Mean | SD | * Reproducibility run 1 ~ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | run 2 ~ run 3 (% CV) | |||

| Calibrator | 2.2 | 2.1 | 2.2 | 2.2 | 0.08 | 0.035 |

| 5 h | 2.4 | 2.6 | 2.4 | 2.5 | 0.12 | 0.051 |

| 24 h | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.6 | 1.7 | 0.06 | 0.035 |

| 10 d | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 0.03 | 0.025 |

| 15 d | 1.5 | 1.3 | 1.5 | 1.4 | 0.11 | 0.075 |

CV: coefficient of variance; SD: Standard deviation

Table 8S. Reproducibility of qPCR assay for cecropin A gene in Escherichia coli-infected Aedes aegypti mosquitoes.

| Sample | Run (% CV) | Mean | SD | * Reproducibility run 1 ~ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | run 2 ~ run 3 (% CV) | |||

| Calibrator | 4.3 | 4.3 | 4.2 | 4.3 | 0.08 | 0.018 |

| 5 h | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 0.07 | 0.055 |

| 24 h | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.06 | 0.098 |

| 10 d | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.08 | 0.098 |

| 15 d | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.06 | 0.347 |

CV: coefficient of variance; SD: Standard deviation

Repeatability

Reproducibility

Footnotes

Financial support:

This work was financed by the Fondo Nacional de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación, Venezuela (grant number 2008000911-1).

Conflicts of interest:

None declared.

References

- 1. Ramos-Castañeda J, Barreto Dos Santos F, Martínez-Vega R, Galvão de Araujo JM, Joint G, Sarti E. Dengue in Latin America: systematic review of molecular epidemiological trends. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017 Jan;11(1):e0005224. PubMed 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Liu T, Xu Y, Wang X, Gu J, Yan G, Chen XG. Antiviral systems in vector mosquitoes. Dev Comp Immunol. 2018 Jun;83:34–43. PubMed 10.1016/j.dci.2017.12.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sim S, Jupatanakul N, Dimopoulos G. Mosquito immunity against arboviruses. viruses. 2014;6:4479-504. 10.3390/v6114479 10.3390/v6114479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4. Wang YH, Chang MM, Wang XL, Zheng AH, Zou Z. The immune strategies of mosquito Aedes aegypti against microbial infection. Dev Comp Immunol. 2018 Jun;83:12–21. PubMed 10.1016/j.dci.2017.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Blair CD. Mosquito RNAi is the major innate immune pathway controlling arbovirus infection and transmission. Future Microbiol. 2011 Mar;6(3):265–77. PubMed 10.2217/fmb.11.11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Carvalho-Leandro D, Ayres CF, Guedes DR, Suesdek L, Melo-Santos MA, Oliveira CF, et al. Immune transcript variations among Aedes aegypti populations with distinct susceptibility to dengue virus serotype 2. Acta Trop. 2012 Nov;124(2):113–9. PubMed 10.1016/j.actatropica.2012.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mains JW, Brelsfoard CL, Rose RI, Dobson SL. Female adult Aedes albopictus suppression by Wolbachia-infected male mosquitoes. Sci Rep. 2016 Sep;6:33846. PubMed 10.1038/srep33846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Xi Z, Ramírez JL, Dimopoulos G. The Aedes aegypti toll pathway controls dengue virus infection. PLoS Pathog. 2008 Jul;4(7):e1000098. PubMed 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sanders HR, Foy BD, Evans AM, Ross LS, Beaty BJ, Olson KE, et al. Sindbis virus induces transport processes and alters expression of innate immunity pathway genes in the midgut of the disease vector, Aedes aegypti. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2005 Nov;35(11):1293–307. PubMed 10.1016/j.ibmb.2005.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Luplertlop N, Surasombatpattana P, Patramool S, Dumas E, Wasinpiyamongkol L, Saune L, et al. Induction of a peptide with activity against a broad spectrum of pathogens in the Aedes aegypti salivary gland, following Infection with Dengue Virus. PLoS Pathog. 2011 Jan;7(1):e1001252. PubMed 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wasinpiyamongkol L, Missé D, Luplertlop N. Induction of defensin response to dengue infection in Aedes aegypti. Entomol Sci. 2015;18:199–206. 10.1111/ens.12108 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pompon J, Manuel M, Ng GK, Wong B, Shan C, Manokaran G, et al. Dengue subgenomic flaviviral RNA disrupts immunity in mosquito salivary glands to increase virus transmission. PLoS Pathog. 2017 Jul;13(7):e1006535. PubMed 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mellor PS. Replication of arboviruses in insect vectors. J Comp Pathol. 2000 Nov;123(4):231–47. PubMed 10.1053/jcpa.2000.0434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Urdaneta L, Herrera F, Pernalete M, Zoghbi N, Rubio-Palis Y, Barrios R, et al. Detection of dengue viruses in field-caught Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) in Maracay, Aragua state, Venezuela by type-specific polymerase chain reaction. Infect Genet Evol. 2005 Mar;5(2):177–84. PubMed 10.1016/j.meegid.2004.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pfaffl MW. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001 May;29(9):e45. PubMed 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fragkoudis R, Chi Y, Siu RW, Barry G, Attarzadeh-Yazdi G, Merits A, et al. Semliki Forest virus strongly reduces mosquito host defence signaling. Insect Mol Biol. 2008 Dec;17(6):647–56. PubMed 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2008.00834.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Colpitts TM, Cox J, Vanlandingham DL, Feitosa FM, Cheng G, Kurscheid S, et al. Alterations in the Aedes aegypti transcriptome during infection with West Nile, dengue and yellow fever viruses. PLoS Pathog. 2011 Sep;7(9):e1002189. PubMed 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kim CH, Muturi EJ. Effect of larval density and Sindbis virus infection on immune responses in Aedes aegypti. J Insect Physiol. 2013 Jun;59(6):604–10. PubMed 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2013.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lin CC, Chou CM, Hsu YL, Lien JC, Wang YM, Chen ST, et al. Characterization of two mosquito STATs, AaSTAT and CtSTAT. Differential regulation of tyrosine phosphorylation and DNA binding activity by lipopolysaccharide treatment and by Japanese encephalitis virus infection. J Biol Chem. 2004 Jan;279(5):3308–17. PubMed 10.1074/jbc.M309749200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sim S, Dimopoulos G. Dengue virus inhibits immune responses in Aedes aegypti cells. PLoS One. 2010 May;5(5):e10678. PubMed 10.1371/journal.pone.0010678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lambrechts L, Scott TW. Mode of transmission and the evolution of arbovirus virulence in mosquito vectors. Proc Biol Sci. 2009 Apr;276(1660):1369–78. PubMed 10.1098/rspb.2008.1709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cooper DM, Chamberlain CM, Lowenberger C. Aedes FADD: a novel death domain-containing protein required for antibacterial immunity in the yellow fever mosquito, Aedes aegypti. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2009 Jan;39(1):47–54. PubMed 10.1016/j.ibmb.2008.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bartholomay LC, Michel K. Mosquito Immunobiology: the intersection of vector health and vector competence. Annu Rev Entomol. 2018 Jan;63:145–67. PubMed 10.1146/annurev-ento-010715-023530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lowenberger C. Innate immune response of Aedes aegypti. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2001 Mar;31(3):219–29. PubMed 10.1016/S0965-1748(00)00141-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]