Abstract

Background:

Trace and essential elements both play a crucial role in maintaining normal cellular and organ functions in human, while abnormal exposure to some of them is also potentially related to diseases, e.g. manganism. To study the association between elemental intake and health outcomes, accurate assessment of elemental uptake and storage in the human body is essential.

Objective:

Technology based on neutron activation analysis can be used for in vivo measurement of the trace elements given that the measurement system guarantees a low detection limit with an acceptable dose. This study aims to design and optimize a customized and portable deuterium–deuterium neutron generator-based irradiation assembly for the NAA of trace elements in vivo, using Monte Carlo simulations.

Approach:

The irradiation assembly includes a moderator, a fast neutron filter, a reflector, and shielding. The human hand phantoms doped with manganese (Mn) and potassium (K) are used to determine the respective elements’ system sensitivity and detection limit.

Main results:

The calculated detection limit is 0.16 μg Mn per gram dry bone (ppm) for Mn and 17 ppm for K, with an equivalent dose of 36 mSv to the hand for 10 min irradiation.

Significance:

This more sensitive in vivo neutron activation analysis system will detect trace elements in vivo.

Keywords: in vivo, manganese, potassium, Monte Carlo, neutron generator

1. Introduction

Neutron activation analysis (NAA) is a well-established analytical technique to determine elemental concentrations in a sample; it has been extensively used for several decades in many different fields, including geochemistry, material sciences, meteorology, and archeology (Chettle and Fremlin 1984, Greenberg et al 2011). The NAA technique analyzes many elements simultaneously, as most elements quickly transform into radioactive isotopes upon neutron exposure, each with their unique decay constant and disintegration product (Pynn 1990, Greenberg et al 2011). Because NAA can analyze a whole sample without chemical or physical destruction, in vivo neutron activation analysis (IVNAA) can offer a non-invasive insight in both humans and animal models. Additionally, IVNAA can be very helpful to understand the realistic metabolism and deposition of trace elements (Anderson et al 1964, Pejović-Milić et al 2008, Anderson et al 2016). Frequently collected and processed biomarkers, such as urine and serum, possess inherent variance. In contrast, recent studies show that bone as a biomarker undergoes less variation as an elemental deposition site in humans (Liu et al 2017). The IVNAA can accurately assay elemental composition and long-term deposition in bones for multiple elements simultaneously (Aslam et al 2008, Liu et al 2018, Hasan et al 2020).

NAA is acceptable for use as an in vivo procedure if the radiation dose delivered is no more than that used in diagnostic radiography (x-rays) (Floyd et al 2006). The development of the IVNAA system heavily relies upon the neutron source. The achievable sensitivity level depends on the neutron yield, neutron energy distribution at the irradiation site, nuclear cross-section (σ), and the measurement system’s efficiency and analysis techniques. Not all of the neutron facilities are suitable for in vivo quantification of elements (Neutron Generators for Analytical Purposes 2012, Anderson et al 2016).

Nuclear reactors are by far the most extensively used neutron facility in NAA due to their higher sensitivity and lower detection limit in elemental analysis than any other source. However, while high-flux nuclear reactors provide exceptionally sensitive NAA, they are a poor choice for in vivo studies due to their limited accessibility, high cost, resulting in nuclear waste, and too-high doses (TECDOC 2001). In the past few decades, along with accelerator-based systems, neutron generators have emerged as a powerful alternative neutron facility, more suitable for in vivo studies than conventional nuclear reactors, and neutron yields superior to conventional nuclear reactor radioisotopes (Sharma 2007, Vainionpaa et al 2014). These customizable generators present a neutron facility that is economical, compact, portable, and easy to install and handle without a specialized operating team. However, their only limitation—having a much lower neutron flux than a nuclear reactor—undermines their efficiency at building a highly sensitive NAA system that can detect elemental concentrations at the same level as a nuclear reactor (Vainionpaa et al 2014, Bergaoui et al 2014). The generator must have a customized irradiation assembly to use a neutron generator for high sensitivity in vivo measurements. Table 1 shows some of the available neutron sources.

Table 1.

Comparison of the different neutron sources available for neutron activation analysis.

| Type | Yield(n s−1) | Neutron distribution | Availability | Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radioisotope sources | 10 7(up to) | isotropic | wide | low |

| Nuclear reactors | 1015 (or higher) | beamlines | limited | high |

| Neutron generators | 107–1011 | isotropic | wide | intermediate |

| Spallation sources | >1015a | beamlines | limited | high |

Effective thermal neutron.

A carefully designed irradiation assembly around the neutron generator can conserve and maximize neutron fluence while keeping radiation exposure within an acceptable range. Another critical parameter that can affect the sensitivity of the irradiation system is a nuclear cross-section. It is a physical quality of each nuclide and varies enormously with incoming neutron energy. Hence, besides maximizing the fluence, the irradiation assembly must produce sufficient neutrons in the thermal energy range (E ~ 0.025 eV). Thermal neutrons are the most suitable for in vivo nuclear reactions because (i) they offer lower doses and (ii) most of the nuclei of interest in our study have a moderate to higher capture cross-section for thermal neutrons. Hence, the purpose of the irradiation assembly design is to modify the neutron energy before application without compromising the neutron fluence (Liu et al 2014, 2017).

IVNAA can help us to understand the significant role of trace elements in the human body and biosphere, which in return, influence overall human health on a large scale. Initial IVNAA studies have shown promising results, suggesting that further research could provide unprecedented solutions (Pejović-Milić et al 2009, Liu et al 2018, Hasan et al 2020). Future progress in this field strongly relies on the development of a reliable irradiation system. The primary purpose of this paper is to describe our IVNAA irradiation assembly simulation design and modeling parameters. We aim to develop a sensitive INVAA system, with a low detection limit, to measure trace elements. Our irradiation assembly capitalizes on two features: (1) optimization of the high thermal neutron fluence at the irradiation site, which increases the reaction rate and hence the system’s sensitivity; and (2) a reduced radiation dose for in vivo analysis. The in vivo neutron activation assembly aims to maximize the thermalized neutron beam towards the sample. After neutron capture, the target nuclei decays to a lower energy state and emits a photon. These photons were measured later with a high-purity germanium detector system. In subsequent sections, we describe the design features of the irradiation assembly, material selection, assembly optimization, and customization of the measurement setup in detail. In this study, we have tested the assembly design for K and Mn. In the future, we plan to measure K in vivo (42K) and assess potassium biokinetics and distribution for a nutrition-based study in order to evaluate the role of K in hypertension and associated diseases.

Additionally, our group has been working on bone manganese (Mn) detection, and its associations with neurological effects (Liu et al 2018). Hence, it is essential to develop a system that could achieve a lower detection limit for manganese toxicity. We also report the gamma spectroscopy and expected radiation dose for our assembly design.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Monte Carlo simulation of irradiation assembly design

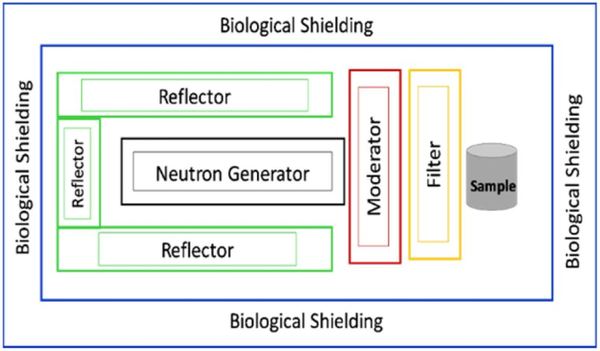

We used Monte Carlo N-Particle (MCNP 6.1) simulation software, developed at Los Alamos National Laboratory, to model our three-dimensional irradiation assembly design and evaluate its stochastic behavior and neutronic performance (http://mcnp.lanl.gov/). In MCNP, pointwise cross-section data libraries allowed us to determine the physics of neutron interactions, associated particle generation, and propagation before leakage or absorption. The ENDF/B-VII nuclear data for the MCNP simulation along with S(a, b) thermal neutron scattering libraries were used to accurately model the behavior of thermal neutrons. Our irradiation assembly design resides around an Adelphi deuterium–deuterium (DD) M109 neutron generator, vertically mounted in our lab with an expected neutron emission rate of 7 × 108 (Vainionpaa et al 2014, Liu et al 2014). For the MCNP simulations, we arranged the neutron beam to follow the XY-plane’s negative z-axis and irradiation site. We used an isotropic neutron source after the DD reaction and the generator’s mechanical specification provided by the manufacturer to simplify the simulation design. We aimed to design an irradiation assembly to deliver high thermal neutron fluence with minimum fast neutron background at the sample site. It is practically challenging to achieve an ideal high fluence thermal neutron beam without gamma rays and fast neutron contamination (Bergaoui et al 2014). Our irradiation assembly design is based on a moderator, fast neutron filter (FNF), and reflector. See figure 1 for the general layout of the irradiation assembly design.

Figure 1.

General layout of the irradiation assembly design (not to scale). Including biological shielding, the sample placed behind the moderator, and filter, whereas the reflector covers the neutron generator from the far side.

2.2. Moderator

The most critical component of the design is the moderator. As the name suggests, the moderator slows down an incoming neutron through several elastic scattering collisions. The interaction probability on the moderator depends upon its thickness and scattering cross-section. The neutron generator produces 2.45 MeV neutrons almost isotropically, so to use these neutrons effectively, their energy must be degraded to the thermal neutron range (approximately 0.025 eV) (Ikeda and Carpenter 1985, Pynn 1990).

Depending upon the neutron source and final application, several materials prove to be good moderators: light water, heavy water, graphite, high-density polyethylene, zirconium hydride, and lithium fluoride. Most of these materials contain high amounts of hydrogen, which offers comparably sized nuclei to the neutron and helps neutrons to dissipate most of their energy in each collision. Although hydrogen has a high scattering cross-section and easily moderates neutron energy to a range from 100 keV to 0.1 eV, depending upon design, it does have a very-high-absorption cross-section as well, which is more pronounced for thick slab designs. When choosing a moderator material, we considered stability against temperature and radiation degradation, customizable geometry, and cost, making a high atomic density polyethylene moderator an appreciable choice (Baker 1970, Beeston 1971, Ikeda and Carpenter 1985).

We designed a rectangular-shaped moderator and placed it against the cylindrical wall of the neutron generator housing wall, mainly because it is much easier to manufacture a slab design than an optimized cylindrical cutout. Because neutrons are emitted isotropically and not as parallel beams, we installed the moderator on only one side of the neutron generator housing. In our design, the moderator side facing the neutron generator receives 2.45 MeV fast neutrons between 0° and 180°. On the other side of the slab design, the efficiency was measured as the neutron intensity in an energy range between E and E + dE per unit area, centered parallel (0° to flight path). Moderator efficiency depends upon incident fast neutron beam, moderator material, and design.

2.3. Fast neutron filter

We chose a thin slab moderator design to convey a high neutron fluence and reduce absorption. However, the beam measured on the other side of the moderator contains undesirable fast neutron fluence that increases the dose burden. A thick neutron moderator would decrease thermal and total neutron fluence due to the high neutron absorption cross-section. Although increasing moderator thickness effectively decreases high energy neutron fluence to an acceptable level, it also decreases its sensitivity (Ikeda and Carpenter 1985, Bergaoui et al 2014).

Fast neutron fluence needs to be reduced without significantly reducing the thermal neutrons to increase its sensitivity. Therefore, our irradiation assembly design uses an FNF made of sapphire (Al2O3) that reduces fast neutrons and the resultant dose with minimal effect on the thermal neutron fluence. We designed the FNF as a slab for consistency with the moderator (Stamatelatos and Messoloras 2000). The MCNP simulation allowed us to optimize the thickness of the FNF using the thermal/fast neutron transmission ratio and the initial fast neutron fluence. The optical property of filters offers low linear attenuation for high wavelengths corresponding to thermal and cold neutrons, while increasing attenuation sharply for fast neutrons, making their transmission very difficult. This property of our FNF not only ameliorates fast neutron attenuation but also reflects them almost 180° toward the moderator, thus enhancing the likelihood of second moderation. Different neutron wavelength groups (table 2) may appear as FNF input due to the moderator design; their relative ratio (the fast neutron group to thermal neutron group) governed the prospective filter thickness (Tennant 1988, Mildner and Lamaze 1998, Stamatelatos and Messoloras 2000). We adopted a parallel optimization technique in the design in order to ascertain the ideal filter and moderator combination to achieve the highest neutron activation with the lowest radiation dose. The selected moderator–filter combination impacts the system’s sensitivity with a short beam ON time, decreases heavily weighted fast neutrons, allows for a thinner moderator without increasing the dose, and delivers the highest thermal neutron fluence.

Table 2.

The energy groups (used in this study) with corresponding energy (MeV), wavelength (Å), and velocity (m/s).

| Neutrons Groups | Energy range (MeV) | Wavelength (Å) | Velocity (m s−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thermal | 1 × 10−8–5 × 10−7 | 2.86–0.40 | 1.3 × 103–9.7 × 103 |

| Intermediate Fast | 1 × 10−6–1 × 10−2 | 0.29–2.9 × 10−3 | 1.38 × 104–1.38 × 106 |

| Intermediate Fast | 2–2.5 | 2 × 10−4–1.8 × 10−4 | 1.9 × 107–2.2 × 107 |

2.4. Reflector

The third component we used, along with the moderator–filter in the irradiation assembly design, was a five-sided reflector. As the neutron yield remains fixed under the given neutron generator operating parameters, it was essential to redirect neutrons originally emitted in arbitrary directions toward the irradiation site (Baker 1970). Here, a five-sided reflector chamber shrouds the neutron generator, a design inspired by flux trapper nuclear plants, and implemented here with a few simplifications. The five-walled reflector reflects neutrons toward the moderator, and after scattering through the reflector, the neutron energy decreases to less than 2.45 MeV. We favored reflector materials with a low mass number, as they have a low-absorption cross-section and allow high reflections without much energy loss. A good reflector should possess the following material qualities: shielding capabilities, high neutron scattering cross-section, low toxicity, engineering simplicity, and low cost (Baker 1970, Beeston 1971). We designed the top and bottom of the reflector chamber to be thinner compared to the chamber wall 180° from the moderator, but all five walls contribute to the reflector’s performance. We gauged the three reflector materials’ performance by measuring the thermal neutron fluence group and the fast neutron group.

2.5. Sensitivity-activated nuclei

We measured the neutronic performance and contribution to the neutron fluence to optimize the moderator’s geometry and dimensions, the FNF, and the reflector for the irradiation design. After finalizing the geometry design, we simulated human hand phantoms to calculate the activated nuclei for IVNAA (Valentin 2002, Liu et al 2017). Table 3 provides details about the target nuclei, cross-section, half-life, branching ratio, etc. The MCNP tally, F4 with the correct reaction type, was utilized to calculate the activated Mn and K nuclei in the simulation. We calculated the expected gamma counts from the phantoms for 10 min irradiation, a 2 min decay, and a measurement time of 30 min for Mn or 60 min for K (using equation (1)). We also obtained counts of calibration lines for Mn and K normalized with calcium (Ca) to determine the detection limit.

| (1) |

where Nc is net counts; No is the number of target nuclei; ω is the isotopic abundance of the target isotope; φt is the neutron fluence; Iγ is emission probability per decay; λ is the decay constant; ta is the sample irradiation time; tb is the decay time; tc is the measurement time; εγ is the absolute photon-peak efficiency of the detector. In IVNAA the detection limit for a particular element depends upon the elemental concentration, typically measured as ppm, the neutron fluence, the irradiation time, and the nuclear properties of the material (e.g. the decay constant, detector efficiency, and background). The detection limit is calculated using equation (2), where background counts were determined from the experimentally measured background with ±2 σ in the desired energy bin with a 95% confidence interval (Liu et al 2017).

Table 3.

The product nuclei, abundance, cross-section, half-lives, branching ratios (BRs), and gamma energy used to calculate activated Mn, K, and Ca.

| Reaction | Abundance | Cross-section | Half-life | B.R | Gamma-ray energy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| [%] | [b] | [h] | [%] | [keV] | |

| 41K (n, γ) 42K | 6.73 | 1.46 ± 0.03 | 12.3 | 18 | 1525 |

| 55Mn (n, γ) 56Mn | 100 | 13.3 ± 0.1 | 2.6 | 99 | 847 |

| 48Ca (n, γ) 49Ca | 0.187 | 0.98 ± 0.04 | 0.15 | 92 | 3084.4 |

| (2) |

2.6. Equivalent dose

We modeled the human hand phantom—composed of hydrogen, carbon, nitrogen, calcium, sodium, etc. Based on the ICRP 89 male reference values and with MCNP at the irradiation site, we calculated the IVNAA dose. We used the MCNP built-in simulation feature to calculate the equivalent dose, using the radiation weighting factor as per ANSI/ANS-6.1.1 (1977) (Beninson et al n.d., Valentin 2002). Additionally, the F4 tally (with each energy region further subdivided into small energy bins) was used along with DE and DF, and conversion factors from ICRP 74. The dose was calculated in the simulation for 10 min irradiation time. Both photons (by using the F4 tally) and neutron dose were measured to estimate the total dose. We designed thick biological shielding around the irradiation facility to reduce radiation exposure to other parts of the body.

3. Results

Our irradiation assembly design was based on two key features: (1) the quality of neutron beam, i.e. ability to produce a homogenous beam with high thermal neutron fluence and minimum fast neutron fluence to the irradiation cave (2) minimal radiation dose to the hand. These two design parameters were optimized in the MCNP, and all results presented here had statistical uncertainty of <5%. The simulation results include design optimization of the irradiation assembly components, the axial thermal neutron fluence, the activated Mn and K nuclei, and the dose.

3.1. Moderator optimization

We designed the high-density polyethylene slab-shaped moderator with dimensions 40 cm × 20 cm × C cm (C represents the thickness). It orthogonally faces the cylindrical neutron generator housing with virtually no distance between the generator and moderator. We initially started with a very thin moderator and gradually increased the thickness in 0.5 cm increments. Although the neutron generator target produces a uniform neutron beam of 2.45 MeV, it becomes a variable energy beam with neutrons of different energies after transmission through the moderator. After the moderator, at the site of measurement where the sample is placed—referred to hereafter as the irradiation cave—we recorded this simulated neutron fluence in different energy groups as given in table 2. We only used the thermal neutron fluence to quantify the moderator’s efficiency, but high epithermal neutron fluence enhances the irradiation system’s sensitivity by increasing activated nuclei; conversely, fast neutron fluence only contributes to the dose. We found that as moderator thickness was increased, so did the measurement of thermal neutron fluence because of the high neutron scattering cross-section (shown in figure 2). However, moderator thickness negatively affected the total neutron fluence due to the high-absorption cross-section. The setup was simulated with both the moderator and biological shielding in place to find the optimum dimensions. Then, the thermal neutron fluence peaked around 3 cm, but the fast neutron fluence and the resultant dose were much higher. Thermal neutron fluence gradually decreased with increased thickness up to 6.5 cm with an accompanying decrease in fast and total neutron fluence, as shown in figure 3. The biological shielding consists of high-density polyethylene that covers the whole irradiation assembly. The biological shielding (with total dimensions of approximately 65 cm × 80 cm × 70 cm) covered all irradiation assembly components, i.e. neutron generator, moderator, filter, and reflector. We initially selected 2 cm, 3 cm, and 4 cm thick moderators for our irradiation assembly design, as they deliver high thermal neutron fluence without compromising the total neutron fluence.

Figure 2.

The neutron fluence (neutron/cm2/primary source) measured at the irradiation cave with different thicknesses of the moderator. The primary y-axis (left, black) shows fast and total neutron fluence density, and the secondary y-axis (right, red) shows thermal neutron fluence.

Figure 3.

Optimization of the moderator thickness by measuring neutron fluence (neutron/cm2/primary source) at the irradiation side with different moderators and fixed biological shielding.

However, the neutron beam obtained with the moderator design contained fast neutrons, which in return increases the dose or detection limit. To combat this issue, we deployed an FNF after the moderator, which filters the fast neutrons with minimal impact on thermal neutrons and supports the high density polyethylene (HDPE) moderator’s mediating properties by reflecting these fast neutrons.

3.2. Reflector optimization

After choosing the optimal moderator and biological shielding combination to enhance the neutron fluence at the irradiation site, we introduced a reflector in the irradiation assembly. As the DD neutron generator emits neutrons almost isotropically, to redirect maximum neutrons towards the irradiation site, we simulated a five-sided neutron reflector in MCNP. The graphite, beryllium oxide, and bismuth were used in simulation as reflectors. Both graphite and beryllium have a low mass number, high-scattering cross-section, and low-absorption cross-section. However, these two materials also slow down the neutron energy; conversely, bismuth offers high neutron availability and lower secondary gamma rays.

For comparing these three materials, the thickness (~18 cm) of the reflector was kept constant (shown in figure 4). Among the three reflector materials we simulated, both beryllium and graphite showed comparable reflective capability. However, we did not select beryllium for the reflector material because of its high engineering cost, maintenance, and associated toxicity. Instead, graphite, with no such issues and comparable neutronic outcome, became our final choice.

Figure 4.

Reflector performance was measured for three materials, bismuth, graphite, and beryllium oxide, and neutron fluence per primary is shown here for three energy regions (divided into bins for fluence measurement but only total fluence is shown here).

We designed the graphite reflector conceptually as a room housing the neutron generator, with three walls, a roof, and a floor. The reflector shroud’s central wall, opposite the moderator, is the thickest; we optimized the thickness between 1 cm and 25 cm (shown in figure 5). The finalized graphite reflector shroud has one approximately 14 cm thick wall covering the neutron generator from the side opposite the irradiation site. The other four sides of the shroud are approximately 5 cm thick. Figure 6 shows the combination of moderator–biological shielding vs. moderator–biological shielding–reflector and their effect on the neutron fluence optimization across different energy levels. The five-sided graphite reflector helps trap and redirect most neutrons toward the irradiation site, increasing the neutron fluence. The reflector improved the neutron fluence and neutron activation rate.

Figure 5.

Thermal neutron fluence measured to optimize the graphite reflector, where the fluence increased up to 12 to 15 cm thickness and become relatively saturated after 15 cm.

Figure 6.

The impact of the graphite reflector on the performance of the irradiation assembly measured as neutron fluence in three energy regions, along with the other two components, i.e. the moderator and biological shielding.

3.3. Filter optimization

We arrayed a parallelopiped single crystal sapphire (Al2O3) FNF next to the moderator to simplify the geometrical design. A single crystal sapphire (Al2O3) without any sharp Bragg cutoff is an excellent FNF. The relative transmission of fast neutron through different filter thicknesses is shown in figure 7. We performed parallel optimization for the moderator and filter thickness using MCNP simulation features (the F4 tally track length estimator for fluency and the PTRAC for particle position and termination). To determine the optimum combination of moderator and filter, we used seven different filter thicknesses individually with each moderator. The FNFs of different thicknesses (between 1 cm and 7 cm) were simulated concurrently with the initially selected moderator thicknesses of 2 cm, 3 cm, and 4 cm. For each moderator–filter combination, we measured the neutron fluence at the irradiation site after the filter. We calculated the axial neutron distribution in each of the three energy groups, as shown in figure 8.

Figure 7.

Relative transmission of the fast neutrons with different thicknesses were measured to find the optimized thickness for the lowest transmission of fast neutrons through the sapphire filter.

Figure 8.

Parallel optimization was performed to find the best combination and dimensions of the irradiation assembly’s component, neutron fluence measured with different combinations of moderator and fast neutron filter.

Fast neutron fluence transmission through the filter depends upon the incident neutron beam, reflector, filter thickness, and moderator thickness. Hence, the fast neutron transmission decreased at different rates with different moderators. Moreover, for IVNAA, we calculated the neutron dose in each case. Three cases were selected as potentially optimum choices, the 3 cm thick HDPE moderator with a 5 cm thick sapphire filter and a 4 cm thick HDPE moderator with a 4 cm and 5 cm thick sapphire filter, shown in figure 9. In the 4 cm moderator with the 4 cm filter combination, thermal neutron transmission was 71%, and fast neutron transmission was 48%. Whereas for the 3 cm moderator with the 5 cm filter, thermal neutron transmission was lower and the fast neutron fluence was higher, affecting the dose of the neutron irradiation assembly. Thus, we selected the 4 cm moderator and 4 cm filter combination. Sapphire crystal also has good gamma attenuation capability, which minimizes the gamma dose and removes the necessity to use a lead attenuation layer in the irradiation assembly.

Figure 9.

A few optimized combinations of the moderator and filter with higher thermal neutron fluence and lower fast neutron fluence (neutron/cm2/primary source) for the assembly.

In the next sections, we discuss the collective impact of improved neutron fluence on the dose and neutron activation.

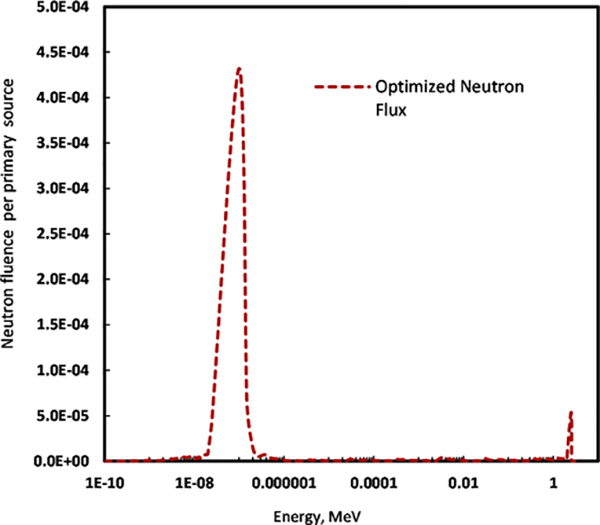

3.4. Irradiation assembly fluence optimization

Using the finalized components, we simulated the fluence for different neutron groups, doses, and neutron activation. Figure 10 shows the neutron fluence measured in different energy groups; these results are normalized per primary neutron source. There was an apparent effect of the FNF, reflector, and biological shielding on the neutron fluence, as neutrons emitted isotropically are reflected from the periphery and contribute usefully to the neutron beam at the irradiation site, where neutron activation takes place. Figure 11 shows the 2D MCNP neutron fluence plots laid over the geometrical design using the MCPLOT feature, which showed that the selected irradiation assembly successfully directed the isotropic point neutron source to the irradiation site. We incorporated the irradiation assembly components’ different material compositions in the energy deposition calculation we performed with the mesh tally. The full irradiation assembly’s spatial energy distribution followed approximately the same inhomogeneous distribution as the spatial fluence. Multiple moderators and geometrical filter combinations in the irradiation assembly array contributed differently to the neutron energy fluence’s relevant energy groups’ tally by nearly 18% to 52%, owing to different scattering and absorption cross-sections and probabilistic radiation interactions.

Figure 10.

Optimized neutron fluence per primary source (neutron/cm2/primary source) with a selected combination of polyethylene moderator, sapphire FNF, graphite reflector and polyethylene biological shielding for in vivo irradiation assembly.

Figure 11.

Neutron fluence measured with simulation design of the modeled irradiation assembly around the neutron generator with an optimized combination of the components, MCNP-YZ view with standard rectangular TMESH tally shown here (measured as number/cm2/primary, where number here refers to neutrons).

The next section provides a sensitivity analysis of the irradiation assembly and the neutron fluence optimization effects.

3.5. Irradiation design sensitivity measurement and calibration

We measured the designed irradiation assembly’s sensitivity as the number of activated nuclei for a particular element in a bone phantom. We simulated Mn- and K-activated nuclei (the reaction rate) with a modified track length estimator tally, in a rectangular (1 × 10 × 20 cm) human hand phantom. These rectangular bone phantoms were doped with 0, 5, 10, 20, and 50 ppm of Mn and K. To determine the expected signal, we used 7 × 108 n s−1 as the neutron emission rate in equation (1). Although we used the same irradiation assembly design, the IVNAA’s sensitivity varies for different elements due to their different nuclear properties. Hence, the higher neutron capture cross-section of Mn resulted in a more significant number of activated Mn nuclei and rendered higher irradiation sensitivity in return.

We utilized activated nuclei obtained with MCNP simulation to estimate the expected signal strength and the correlated detection limit. The HPGe detector’s absolute efficiency was 0.048 and 0.039 for Mn and K, respectively. The activated nuclei and expected gamma counts given in table 4 for both Mn and K (K-42) were calculated using 10 min irradiation, a 2 min decay, and a measurement time of 30 min for Mn or 60 min for K.

Table 4.

Simulated Mn and K counts for different concentrations in the human hand phantom.

| Concentration | Mn counts | K counts | Mn/Ca | K/Ca |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 ppm | 77.5 | 0.72 | 0.09 | 8.0E-4 |

| 5 ppm | 385.3 | 3.61 | 0.43 | 4.0E-3 |

| 10 ppm | 773.4 | 7.21 | 0.86 | 8.0E-3 |

| 20 ppm | 1546.5 | 14.42 | 1.72 | 1.6E-2 |

| 50 ppm | 3866.8 | 36.04 | 4.31 | 4.0E-2 |

Figures 12 and 13 show the expected specific gamma signal calibration line from the simulated Mn- and K-activated nuclei with the HPGe detector for 10 min irradiation.

Figure 12.

Calibration line for human hand phantoms doped with 1 ppm, 5 ppm, 10 ppm, 20 ppm, and 50 ppm of manganese normalized with calcium (Mn/Ca) based on activated nuclei obtained with the MCNP simulation.

Figure 13.

Calibration line for human hand phantoms doped with 1 ppm, 5 ppm, 10 ppm, 20 ppm, and 50 ppm of potassium normalized with calcium (K/Ca) based on activated nuclei obtained with the MCNP simulation.

3.6. Detection limit

Based on our simulation results, the expected detection limit in bone is 0.16 μgg−1 (ppm) for Mn and approximately 17 μgg−1 for K.

3.7. Dose

The dose calculation was an essential parameter for optimizing the irradiation assembly design. We considered both gamma and neutron doses. The neutron equivalent dose calculation included the total neutron fluence from all three neutron groups, whereas the gamma dose mainly comes from the hydrogenous shielding material. MCNP simulation showed the neutron dose to be 35.2 mSv and the gamma dose to be 1.04 mSv for the 10 min irradiation. The neutron equivalent doses calculated with two different flux to dose conversion references, i.e. ICRP74 and ANSI/ANS-6.1.1, agreed well (<10% difference). The total dose from the neutrons and photons governs the IVNAA measurement protocol, as the dose defines the irradiation time, impacting in vivo sensitivity.

4. Discussion

To utilize NAA’s capability for in vivo measurement, we designed a customized irradiation assembly around a DD neutron generator using the simulation software package MCNP. To enhance the system’s sensitivity—i.e. to attain a lower detection limit while keeping the dose within an acceptable range—the designed assembly consists of a moderator, an FNF, and a reflector. The HDPE moderator, highly enriched with hydrogen nuclei, not only moderates neutron energy but it also absorbs the neutron. Hence, we had two challenges in designing the fluence optimization assembly: to increase the system sensitivity while decreasing neutron absorption.

Our first task was to determine how to increase thermal neutron fluence with minimum neutron absorption. Compared to moderator performance alone, neutron activation was higher than expected for the irradiation assembly as we measured the efficiency improvement of the moderator with the thermal neutron group only. However, the epithermal neutron fluence at the irradiation site also positively contributed to the activated nuclei. The FNF successfully reduced the high-energy neutrons and dose burden, which enhanced the system sensitivity (Stamatelatos and Messoloras 2000). Simulation results showed that at room temperature, as in our case, sapphire can perform well in mixed neutron and gamma radiation fields (Tennant 1988). While adhering to the ALARA principle, we tried to keep the dose as minimal as possible. Hence, we have selected the upper limit to be 50 mSv to perform in vivo activation analysis. For 10 min of irradiation, we calculated the neutron equivalent dose in a human hand phantom to be 36 mSv, with 7 × 108 neutrons s−1. We used the most recent neutron cross-section libraries to determine a more accurate thermal neutron scattering treatment, especially for the FNF. Our five-sided reflector minimized the possibility of neutron escape from the irradiation assembly.

For 10 min irradiation, 2 min decay, and 30 min measurement time, the expected Mn detection limit was 0.16 ppm in the human hand phantom. The Mn level in the body is approximately 1 μg g−1 of bone (ICRP 1975), whereas the detection limits for in vivo Mn measurement were reported as 0.32 μgMng−1 in bone using an accelerator-based system (Pejović-Milić et al 2008, 2009) and 0.64 μgg−1 by using the DD neutron generator-based system (Liu et al 2017). Compared with the DD neutron generator-based system—6 cm HDPE moderator, 8 cm graphite, and 8 cm HDPE reflector—this new, prudent design showed significant improvement (0.64 ppm vs. 0.16 ppm). This improvement can be attributed to the combined effect of a thin moderator, an FNF, and a chamber design reflector. We employed a thin moderator (4 cm) to reduce the neutron absorption and scattering, and hence we were able to increase the neutron fluence. We utilized an FNF, which reflects the fast neutrons towards the moderator, hence giving them a second chance to moderate. Without the FNF, the dose was 85 mSv; however, with the FNF, the dose decreased to 36 mSv. Differently than in the previous design, here we have used only one reflector in this assembly. Additionally, the reflector was designed as a five-sided covering instead of a slab design. The detection limit for manganese was lower than the detection limit obtained with the previous model (0.16 ppm vs. 0.64 ppm). However, the simulated detection limit requires experimental verification. The actual signal may include noise from the high-energy Compton continuum, partial overlaps from competing reactions, and contributions from the shielding materials.

In contrast, K had a low-activation cross-section and branching ratio, which indicates that further improvement to the system might be required to detect very low K (K-42) concentrations. The calculated detection limit for K-42 is 17 ppm for 10 min irradiation, 2 min decay, and 60 min measurement time. However, no previous literature is available to compare the detection limit of in vivo potassium measurement. Potassium concentration is considered in bone phantoms here. However, in reality, potassium is much higher in soft tissue as compared with bone. This difference must be taken into account. K is found at approximately 2000 ppm in the human body (ICRP 1975). Also, simultaneous measurement of k-42 and k-40 can be useful in studying in vivo potassium metabolism. Potassium-40 measurement also requires a reduction in background radiation from the environment, improving the detection limit further. Background reduction will be addressed in our future work.

Overall, our irradiation assembly design looks promising. However, a few small modifications, e.g. a customized build of reflector shroud and FNF aperture, may be necessary to convert the simulated design to an engineering model. These changes are not likely to affect the system’s sensitivity significantly. However, as we intend to build this system in our lab, and we will perform experimental validation in our next study.

5. Conclusion

We designed an irradiation assembly for in vivo measurement of trace elements in this work, utilizing three main components. The moderator helps achieve a higher thermal fluence, the FNF possibly decreases the unwanted fast neutron’s dose, and the reflector houses the neutron generator and redirects neutrons toward the irradiation site. The sensitivity of the system and detection limit heavily relies upon the achievable thermal neutron fluence. A higher thermal neutron fluence gives a lower detection limit for trace elements within the given time. Hence, we designed our compact DD neutron generator-based irradiation assembly specifically to achieve a high thermal neutron fluence while keeping the expected dose burden low. We optimized both the emitted neutron beam’s energy and fluence from the generator in the irradiation assembly before reaching the target, resulting in an in vivo measurement system sensitive enough for measuring low concentrations of trace elements.

References

- Anderson IS, Andreani C, Carpenter JM, Festa G, Gorini G, Loong CK and Senesi R 2016. Research opportunities with compact accelerator-driven neutron sources Phys. Rep 654 1–58 [Google Scholar]

- Anderson J, Osborn SB, Tomlinson RWS, Newton D, Salmon L, Rundo J and Smith JW 1964. Neutron-activation analysis in man in vivo. A new technique in medical investigation Lancet 23 1201–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aslam A, Pejović-Milić DR, Chettle DR, Mcneill FE and Pysklywec MW 2008. A preliminary study for non-invasive quantification of manganese in human hand bones Phys. Med. Biol 53 N371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker DE 1971. Graphite as a neutron moderator and reflector material Nucl. Eng. Des 14 413–44 [Google Scholar]

- Beeston JM 1971. Beryllium metal as a neutron moderator and reflector material Nucl. Eng. Des 14 445–74 [Google Scholar]

- Beninson D et al. n.d. Annals of the ICRP Published on behalf of the lnternational commission on Radiological Protection I. A-Ilyin, Moscow [Google Scholar]

- Bergaoui K, Reguigui N, Gary CK, Brown C, Cremer JT, Vainionpaa JH and Piestrup MA 2014. Development of a new deuterium-deuterium (D-D) neutron generator for prompt gamma-ray neutron activation analysis Appl. Radiat. Isot 94 319–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chettle DR and Fremlin JH 1984. Techniques of in vivo neutron activation analysis Phys. Med. Biol 29 1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floyd CE, Bender JE, Sharma AC, Kapadia A, Xia J, Harrawood B, Tourassi GD, Lo JY, Crowell A and Howell C 2006. Introduction to neutron stimulated emission computed tomography Phys. Med. Biol 51 3375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg RR, Bode P and De Nadai Fernandes EA 2011. Neutron activation analysis: a primary method of measurement Spectrochim. Acta B 66 193–241 [Google Scholar]

- Hasan Z. et al. Characterization of bone aluminum, a potential biomarker of cumulative exposure, within an occupational population from Zunyi, China. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2020;59:126469. doi: 10.1016/j.jtemb.2020.126469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IAEA 2012. Neutron generators for analytical purposes IAEA Radiation Technology Reports No. 1, IAEA [Google Scholar]

- ICRP 1975. Report of the Task Group on Reference Man. ICRP Publication 23 Pergamon [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda S and Carpenter JM 1985. Wide-energy-range, high-resolution measurements of neutron pulse shapes of polyethylene moderators Nucl. Inst. Methods Phys. Res. A 239 536–44 [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Byrne P, Wang H, Koltick D, Zheng W and Nie LH 2014. A compact DD neutron generator-based NAA system to quantify manganese (Mn) in bone in vivo Physiol. Meas 35 1899–911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Mostafaei F, Sowers D, Hsieh M, Zheng W and Nie LH 2017. Customized compact neutron activation analysis system to quantify manganese (Mn) in bone in vivo Physiol. Meas 38 452–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Rolle-Mcfarland D, Mostafaei F, Zhou Y, Li Y, Zheng W, Wells E and Nie LH 2018. In vivo neutron activation analysis of bone manganese in workers Physiol. Meas. 39 035003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mildner DFR and Lamaze GP 1998. Neutron transmission of single-crystal sapphire J. Appl. Crystallogr 31 835–40 [Google Scholar]

- Pejović-Milić A, Chettle DR and Mcneill FE 2008. Quantification of manganese in human hand bones: A feasibility study Phys. Med. Biol 53 4081–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pejović-Milić A, Chettle DR and Pejović-Milić AJ 2009. Opportunities to improve the in vivo measurement of manganese in human hands Phys. Med. Biol 54 17–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pynn R 1990. Neutron scattering: a primer (Los Alamos National Laboratory lecture; ) (https://www.ncnr.nist.gov/summerschool/ss16/pdf/NeutronScatteringPrimer.pdf) [Google Scholar]

- Sharma AC, Harrawood BP, Bender JE, Tourassi GD and Kapadia AJ 2007. Neutron stimulated emission computed tomography: a Monte Carlo simulation approach Phys. Med. Biol 52 6117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamatelatos IE and Messoloras S 2000. Sapphire filter thickness optimization in neutron scattering instruments Rev. Sci. Instrum. 71 70–73 [Google Scholar]

- TECDOC 2001. Use of Research Reactors for Neutron Activation Analysis (Vienna: IAEA; ) [Google Scholar]

- Tennant DC 1988. Performance of a cooled sapphire and beryllium assembly for filtering of thermal neutrons Rev. Sci. Instrum 59 380–1 [Google Scholar]

- Vainionpaa JH, Gary CK, Harris JL, Piestrup MA, Pantell RH and Jones G 2014. Technology and applications of neutron generators developed by Adelphi Technology, Inc. Proc. Physics Procedia vol 60 (Amsterdam: Elsevier; ) pp 203–11 [Google Scholar]

- Valentin J 2002. Basic anatomical and physiological data for use in radiological protection reference values. ICRP publication 89 Ann. ICRP; 32 1–277 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]