Abstract

Picrorhiza kurroa is a medicinally important, high altitude perennial herb, endemic to the Himalayas. It possesses strong hepato-protective bioactivity that is contributed by two iridoid picroside compounds viz Picroside-I (P-I) and Picroside-II (P-II). Commercially, many P. kurroa based hepato-stimulatory Ayurvedic drug brands that use different proportions of P-I and P-II are available in the market. To identify genetically heterozygous and high yielding genotypes for multiplication, sustained use and conservation, it is essential to assess genetic and phytochemical diversity and understand the population structure of P. kurroa. In the present study, isolation and HPLC based quantification of picrosides P-I and P-II and molecular DNA fingerprinting using RAPD, AFLP and ISSR markers have been undertaken in 124 and 91 genotypes, respectively. The analyzed samples were collected from 10 natural P. kurroa Himalayan populations spread across four states (Jammu & Kashmir, Sikkim, Uttarakhand and Himachal Pradesh) of India. Genotypes used in this study covered around 1000 km geographical area of the total Indian Himalayan habitat range of P. kurroa. Significant quantitative variation ranging from 0.01 per cent to 4.15% for P-I, and from 0.01% to 3.18% in P-II picroside was observed in the analyzed samples. Three molecular DNA markers, RAPD (22 primers), ISSR (15 primers) and AFLP (07 primer combinations) also revealed a high level of genetic variation. The percentage polymorphism and effective number of alleles for RAPD, ISSR and AFLP analysis varied from 83.5%, 80.6% and 72.1%; 1.5722, 1.5787 and 1.5665, respectively. Further, the rate of gene flow (Nm) between populations was moderate for RAPD (0.8434), and AFLP (0.9882) and comparatively higher for ISSR (1.6093). Fst values were observed to be 0.56, 0.33, and 0.51 for RAPD, ISSR and AFLP markers, respectively. These values suggest that most of the observed genetic variation resided within populations. Neighbour joining (NJ), principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) and Bayesian based STRUCTURE grouped all the analyzed accessions into largely region-wise clusters and showed some inter-mixing between the populations, indicating the existence of distinct gene pools with limited gene flow/exchange. The present study has revealed a high level of genetic diversity in the analyzed populations. The analysis has resulted in identification of genetically diverse and high picrosides containing P. kurroa genotypes from Sainj, Dayara, Tungnath, Furkia, Parsuthach, Arampatri, Manvarsar, Kedarnath, Thangu and Temza in the Indian Himalayan region. The inferences generated in this study can be used to devise future resource management and conservation strategies in P. kurroa.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12298-021-00972-w.

Keywords: Picrorhiza kurroa, Genetic diversity, Molecular DNA markers, Phytochemical diversity, Picrosides, HPLC

Introduction

Plant based compounds offer safer therapeutic options as opposed to many harmful side effects associated with synthetic drugs. Due to this, there has been a tremendous increase in the demand of phyto-pharmaceutical compounds globally. The current needs are largely met by an indiscriminate collection of medicinal plant species from their natural habitats. Harvesting of medicinal plants’ germplasm from the wild runs to hundreds of tons of the collected material annually (Kumar et al. 2014; Kumar et al. 2016; Shitiz et al. 2015; Singh and Sharma 2020). This over-exploitation poses a grave threat to many important medicinal plant species, necessitating an urgent development of strategies, for their effective use and conservation.

Picrorhiza kurroa Royle ex Benth (Family Plantaginaceae; Akbar 2020), locally known as ‘Kutki’ or ‘Karu’ (Kumar 2019) is a medicinally important, high altitude perennial herb. It is endemic to the Himalayan region and is distributed in India, China, Pakistan, Nepal and Bhutan (Masood et al. 2015). It is widely used in ayurvedic system of medicine to treat the disorders of liver and upper respiratory tract, jaundice, fever, chronic diarrhea and scorpion sting (Krishnamurthy 1969; Vaidya et al. 1996). The species shows hepato-protective, stomachic, anti-inflammatory, anti-tumor, immuno-modulatory, hypolipidemic, hypoglycemic and antispasmodic bioactivities (Tiwari et al. 2012; Bhattacharjee et al. 2013; Sultan et al. 2016; Mahajan et al. 2016). The pharmacological properties of P. kurroa are attributed to the presence of various monoterpene-derived Iridoide glycosides known as picrosides that include picroside-I, and picroside-II, metabolites picrosides III, IV and V and other compounds. P. kurroa contains as many as 7 such iridoid glycosides namely kutkin, kutkoside, picroside V, pikuroside, mussaenosidic acid, bartsioside and boschnaloside (Bhat et al. 2013; Katoch et al. 2013; Kumar et al. 2016, 2017; Soni and Grover 2019;). Both picrosides P-I and P-II have been found in root and rhizome of the plant, while P-I has also been isolated from the shoots (Kumar et al. 2017; Debnath et al. 2020). Many ayurvedic hepato-protective drug preparations made of Picrorhiza extracts, namely Katuki, Picroliv, Livocare, Livomap, Livplus, Livomin etc. that are commercially available in the market contain picroside active principles P-I and P-II in 1:1.5 proportions (Bhat et al. 2013; Kumar 2019; Singh and Sharma 2020). Picrorhiza entails an approximate global annual demand of 500 tons against a supply of 375 tons, out of which India contributes 75 tons/year. P. kurroa is listed among top 15 most traded medicinal plant species in India based on revenue generation in trade (Thani et al. 2018; Debnath et al. 2020). Due to overexploitation, the existence of P. kurroa is threatened and the species is listed as ‘endangered’ in Appendix II (Aug, 2020 onwards) of CITES (https://cites.org/eng/app/appendices.php) and also in Barik et al. (2018), in India as per IUCN criteria (ver. 3.1).

Although the plant is self-regenerating, but due to reckless collections from its entire wild range of Himalayas, inappropriate methods of extraction of the material, inadequate cultivation practices and low seed viability, the presence of P. kurroa in wild, is continuously declining. This has become an important socioeconomic concern among farmers, industry and policy makers (Kumar 2019; Nayar et al. 1990). P. kurroa is now listed in the negative lists of exports of Govt. of India (Mehra et al. 2017; Barik et al. 2018; Kumar 2019; Singh and Sharma 2020) with legal restrictions being levied on its collection from the wild (Kumar et al. 2017).This has resulted in illegal collections and adulteration of picrosides P-I and P-II.

To streamline the current demands and supply of Kutki, it is important to devise effective germplasm management and sustainable strategies. One of the important pre-requisites for devising meaningful plant resource management strategies includes partitioning of the available genetic diversity based on characterization of existing gene pools. Such demarcation helps in (i) identifying elite/superior genotypes for multiplication and sustained use, (ii) devising conservation strategies and (iii) planning future breeding programs for genetic improvement of these species. Superior validated germplasm can be directed towards cultivation to make quality raw material available.

Many Molecular DNA markers like RAPD, ISSR and AFLP have been widely used for documentation of genetic diversity and understanding the population structure in many plant species. These multi-locus markers with high multiplex ratio offer the advantages of being free from the developmental and environmental influences, are relatively abundant, and produce sufficient polymorphism to demarcate genotypes in a population (Sarwat et al. 2008; Naik et al. 2010; Singh et al. 2015; Thiyagarajan and Venkatachalam 2015; Costa et al. 2016; Lone et al. 2018; Nazarzadeh et al. 2020). To the best of our knowledge, these markers have not, so far, been used in P. kurroa diversity assessment. A few studies have rather used SSR DNA markers (Katoch et al. 2013; Shitiz et al. 2017; Singh and Sharma 2020) for genetic analysis in P. kurroa. Likewise, HPLC-based quantitation of useful phytochemical compounds from roots and rhizomes of P. kurroa has been done to identify high yielding elite genotypes (Katoch et al. 2011, 2013; Thapliyal et al. 2012; Shitiz et al. 2015; Sultan et al. 2016; Mehra et al. 2017; Soni and Grover 2019; Singh and Sharma 2020). These studies, though, have reported substantial genetic diversity among populations, but mostly, except Sultan et al (2016) are limited with the use of only a few populations, limited markers and a small sample size. To make meaningful inferences about the overall spectrum of available genetic diversity in this medicinally important species, there is an urgent need to comprehensively characterize its existing wild gene pools using multiple markers on the same set of genotypes.

The present analysis, in this context, represents the first exhaustive attempt to assess both the genetic diversity in 91 genotypes and phytochemical profiling in 124 genotype of P. kurroa representing 10 different populations growing all along its native range (spanning ~ 1000 km) in north east to north west Indian Himalayas. The use of multiple molecular DNA markers like RAPD, AFLP and ISSR fingerprinting will help in scanning different portions of the genome to provide a comprehensive account of genetic diversity. Further analysis of the same set of genotypes for phytochemical quantification of picrosides P-I and P-II will provide a correlation, if any, between genetic heterozygosity and the synthesis of active principles. This study is, by far, the largest genotyping and chemotyping study performed on the same set of genotypes from the wild germplasm of P. kurroa.

Material and methods

Plant materials

A list of 91 genotypes, belonging to 10 populations, investigated for their genetic diversity is given in Table 1. Out of 10 populations, 9 populations, represented by 55 genotypes, were collected from major distribution areas of the species from North East to North West Indian Himalayas (Fig. 1). The remaining 36 genotypes, collected initially from 15 regions of Himachal Pradesh, were grown in the experimental farm of Dr. Y. S. Parmar University, Solan. These 36 genotypes have been, therefore, designated as Rahala population. Not more than four to six young leaves were harvested from each plant and were immediately immersed in liquid N2 to be later stored at – 80 °C.

Table 1.

Picrorhiza kurroa germplasm resources collected across the Himalayas and used for genetic and phytochemical diversity assessment in the present study

| States/regions | Locations | Population | Number of genotypes | Genotype ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Pop) number | ||||

| Jammu and Kashmir | Arampatri | Pop 1 | 10** | PK01-PK10 |

| Sonamarg | Pop 2 | 07*** | PK11-PK17 | |

| Manvarsar | Pop 3 | 04*** | PK18-PK21 | |

| Sikkim | Temza | Pop 4 | 4 | PK22-PK25 |

| Thangu | Pop 5 | 05*** | PK26-PK30 | |

| Uttarakhand | Kedarnath | Pop 6 | 10 | PK31-PK40 |

| Dayara | Pop 7 | 6 | PK41-PK46 | |

| Tungnath | Pop 8 | 4 | PK47-PK50 | |

| Jhuni | Pop 9 | 5 | PK51-PK55 | |

| Himachal Pradesh | Rahala, Solangnala, Kafnu, Sainj, Pulga, Rohtang, Manimahesh, Holi, Grahan, Saptadhar, Piyyankar, Furkia, Parsuthach | Pop 10* | 36 | PK56-PK91 |

| Uttarakhand | Tungnath | Pop 8 | 03**** | PK92-PK94 |

| Himachal Pradesh | Kafnu | Pop 10 | 02**** | PK95-PK96 |

| Sainj | 05**** | PK97-PK101 | ||

| Pulga | 02**** | PK102-PK103 | ||

| Rohtang | 04**** | PK104-PK107 | ||

| Manimahesh | 04**** | PK108-PK111 | ||

| Holi | 03**** | PK112-PK114 | ||

| Grahan | 03**** | PK115-PK117 | ||

| Saptadhar | 03**** | PK118-PK120 | ||

| Piyyankar | 03**** | PK121-PK123 | ||

| Gulaba | 08**** | PK124-PK131 | ||

| Sai Ropa | 06**** | PK132-PK137 | ||

| Rampur | 08**** | PK138-PK145 |

*Leaf materials collected from the cultivated genotypes maintained at the experimental farm of Dr. Y. S. Parmar University of Horticulture and Forestry, Solan, designated as Rahala population

**Out of 10 genotypes, only 5 genotypes (PK1-PK5) were used in chemical profiling

***These genotypes were not used in the chemical profiling

****These genotypes were not part of the molecular analysis

Fig. 1.

Germplasm collection sites of Picrorhiza kurroa from India

For the extraction and quantitation of active phytochemical constituents such as picrosides P-I and P-II, 124 genotypes, belonging to 10 populations were collected from North East to North West Himalayas (Table 1). A part of the rhizome was excavated for phytochemical analysis. For preparation of standard and stock solutions ~ 500 g of dried rhizomes procured from the local market in Himachal Pradesh and authenticated at Y.S. Parmar University, Solan, H.P. was used.

Genetic diversity assessment

DNA extraction

The total genomic DNA extracted from young leaves was extracted by a modified DNA extraction protocol as given by Kumar et al. (2014).

RAPD fingerprinting

One hundred arbitrary primers (Operon Technologies, Inc., Alameda, California, USA) were initially tested with three genotypes, out of which 22 primers produced clear amplification products that were easily scorable. These 22 primers were used for comprehensive fingerprinting. The reaction mixture of 25 μl volume contained 2.5 μl 10X assay buffer (Biotools, Spain), 0.24 mM dNTPs (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, USA), 15 ng primer (Operon Technologies Inc., Alameda, USA), 0.5 U Taq DNA polymerase (Biotools), 50 ng template DNA and 1.5 mM MgCl2 (Biotools). DNA amplification was performed in a Perkin Elmer Cetus 480 DNA thermal cycler programmed to 1 cycle of 4 min 30 s at 94 °C (denaturation), 1 min at 40 °C (annealing), and 2 min at 72 °C (extension); followed by 44 cycles of 1 min at 94 °C, 1 min at 40 °C and 2 min at 72 °C ending with 1 cycle of 15 min at 72 °C (final extension).

ISSR fingerprinting

One hundred SSR primers (Biotechnology Laboratory, University of British Columbia, Canada) were tested for amplification in two genotypes. Of these, 15 were found to produce robust amplification products. These 15 SSR primers were finally used for PCR amplification. The 25 μl reaction volume contained 2.5 μl 10X assay buffer (Biotools), 0.24 mM dNTPs (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech), 5 μM primer, 0.75 U Taq DNA polymerase (Biotools), 50 ng template DNA, 1.5 mM MgCl2 (Biotools) and 2% formamide. Initial denaturation in Perkin Elmer Cetus 480 DNA thermal cycler was done at 94 °C for 7 min, followed by 44 cycles of 30 s at 94 °C, 45 s at the particular annealing temperature calculated by Wallace rule (Thein and Wallace 1986) and 2 min at 72 °C ending with 1 cycle of 7 min at 72 °C.

The amplification products in both the cases were size separated by standard horizontal electrophoresis in 1.4% agarose (Sigma, USA) gels and stained with ethidium bromide. The reproducibility of DNA profiles was tested by repeating the PCR amplification thrice with each of the analyzed primer. Only the robust bands that were found to be repeatable were scored for data analysis.

AFLP fingerprinting

About 500 ng of genomic DNA was digested with EcoRI and MseI at 37 °C for 2 h followed by heat treatment at 70 °C for 10 min to inactivate the enzymes. The digested DNA was ligated to EcoRI and MseI adaptors for 2 h at 20 °C. The ligation mixture was then diluted five fold, and selectively pre-amplified (EcoRI primer + A, MseI primer + C) during 20 PCR cycles programmed each at 94 °C for 30 s, 56 °C for 30 s and 72 °C for 60 s. Twenty-five fold diluted aliquots of pre-amplified fragments were then selectively amplified in the presence of 32P-labelled EcoRI + 3 and MseI + 3 (primers with 3 selective nucleotides) primers. The PCR condition for this amplification was one cycle at 94 °C for 30 s, 65 °C for 30 s and 72 °C for 60 s followed by 12 cycles in which the annealing temperature was progressively lowered by 1 °C, and finally 20 cycles at 94 °C for 30 s, 56 °C for 30 s and 72 °C for 60 s. The amplified fragments were electrophoresed in 6% denaturing polyacrylamide sequencing gel on a Sequi-Gen (BioRad, USA) sequencing cell. Electrophoresis was carried out at 50 W for 3 h in 1 × TBE at 55 °C. Gel was wrapped in Saran wrap and dried for 1 h at 80 °C. Autoradiogram was developed by exposing Konica X-ray film (AX) on the dried gel overnight at − 80 °C with intensifying screens.

Data analyses

All the amplified bands were scored for the presence (1) or absence (0) and scores were assembled in a rectangular data matrix. The binary matrices were subjected to statistical analysis using the Numerical Taxonomy and Multivariate Analysis System, NTSYS-pc version 2.02 k (Rohlf 1998). Jaccard’s similarity co-efficient was employed to compute pairwise genetic similarities. The similarity matrices were constructed for each marker type. Sequential, agglomerative, hierarchical, nested (SAHN) cluster analysis was performed on the data matrix using the unweighted pair group method with the arithmetic averaging (UPGMA) algorithm and 25 iterations. The neighbour joining (NJ) option was also used to construct neighbour joining tree. The validity of the clustering was determined by comparing the similarity and cophenetic value matrices using the matrix comparison module of NTSYS-pc. Principal Component Analysis (PCoA) was done using the PCA function of NTSYS-pc ver 2.02. Bayesian model based clustering method of STRUCTURE ver 2.3.4 (Falush et al. 2007; Pritchard et al. 2000) was employed to estimate the genetic structure. Three independent runs with K values ranging from 3 to 8 and three iterations for each value of K was set. Length of burn-in period and number of Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) repeats after burn-in were set at 5000 and 50,000, respectively. Results of STRUCTURE were visualized using STRUCTURE HARVESTER (Evanno et al. 2005; Earl 2012) to get the best value of K for the data. Polymorphic information content (PIC) and Marker Index (MI) of each marker was calculated according to Chesnokov and Artem’eva (2015).

Genetic structure of population

Matrices based on population genetic data were analyzed using the software Popgene version 1.31 (Yeh et al. 1999) and Arlequin 3.1 (Excoffier et al. 2005). The Shannon index (I), Nei’s genetic diversity (h), observed numbers of allele (na), effective numbers of alleles (ne), Nei’s genetic identity and distance, number of migrants (Nm) between populations based on Nei’s genetic variation (Gst) [Nm = 0.5(1 − Gst)/Gst] and the number of polymorphic loci were estimated for each population using POPGENE version 1.31. Analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA) was used to estimate the variation among populations using Arlequin 3.1, providing Fst values which represent the degree of genetic differentiation or population subdivision. The genotypes, populations and the regions were subdivided into small groups on a predetermined criterion so as to test and quantify between and within group variation. In order to confirm the Fst values, AMOVA data were submitted to 1023 independent permutations and P values lower than 0.05 were considered significant.

Chemical prospecting

Isolation and preparation of standard and stock solutions of picrosides

Isolation and extraction procedure

The dried rhizomes (500 g) of P. kurroa were extracted with 1L methanol. The methanolic extract was concentrated under reduced pressure and the residue (380 g) was column chromatographed over silica gel (60–120 mesh). The column was eluted with solvents of increasing polarities, starting with petroleum ether, CHCl3, and variable concentrations of CHCl3 and MeOH. Different fractions of 200 ml each were collected and verified by TLC. The fractions obtained by the elution of column using CHCl3:MeOH (96:4) and CHCl3:MeOH (90:10) yielded compound A and compound B. The structure of two isolated compounds was confirmed by the physical and spectroscopic data and they were identified as picroside-I (P-I) and picroside–II (P-II), respectively (Fig. 2). IR, 1H NMR and MS were used to deduce the following spectroscopic details of the two isolated compounds.

Fig. 2.

Chemical structure of picroside I and picroside II

Compound A (P-I): Mp: 127-128 °C (lit. mp. 128-129 °C (Mandal and Mukhopadhyay 2004); IR (KBr, umax cm−1): 3200-3420 (broad, OH), 1705 (conjugated ester), 1660 (enol ether); 1H NMR (CD3CN, 300 MHz, d in ppm): H-9 (2.24, dd, J = 4.2, 1.6 Hz, 1H), H-5 (2.48, dd, J = 9.6, 7.9 Hz, 1H), H-2′, H-3′, H-4', H-5' (3.27-3.62, m, 4H), H-7 (3.84, d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), H-10a (4.14, d, J = 12.9 Hz, 1H), H-6 (4.38, dd, J = 12.4, 6.0 Hz, 1H) H-10b (4.42, d, J = 12.9 Hz, 1H), H-6a' (4.74, d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), H-6b′ (4.86, d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), H-4 (5.06, m, 1H), H-1 (5.14, m, 1H), H-1' (5.22, d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H), H-3 (6.24, m, 1H), Ha (6.48, d, J = 16.0 Hz, 1H), Ar-H (7.32-7.50, m, 5H), Hb (7.66, d, J = 16.0 Hz, 1H); ESI-MS (m/z): 493.1670 (M+1).

Compound B (P-II): Mp: 211–212 °C (lit. mp. 212-213° C (Mandal and Mukhopadhyay 2004); IR (KBr, umax cm−1): 3600-3225 (broad, OH), 1700, 1636 (conjugated ester); 1H NMR (CD3CN, 300 MHz, d in ppm): H-9 (2.60, t, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), H-5 (2.68, m, 1H), H-2', H-3', H-4', H-5', H-6a' & H-6b' (3.20-3.56, m, 6H), H-7 (3.78, d, J = 9.2 Hz, 1H), H-10b (3.82, d, J =13.1 Hz, 1H), -OCH3 (3.93, s, 3H), H-10a' (4.12, d, J =13.1 Hz, 1H), H-4 (4.80, d, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H), H-1' (5.02, d, J = 9.7 Hz, 1H), H-6 (5.08, dd, J = 9.0, 6.7 Hz, 1H), H-1 (5.12, d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), H-3 (6.45, d, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H), H-5'' (6.93, d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), H-2'' (7.56, d, J =1.7 Hz, 1H), H-6'' (7.6, dd, J = 8.3, 1.8 Hz, 1H), OH (7.81, s, 1H); ESI-MS (m/z): 513.1457 (M+1).

Preparation of standard and stock solutions

Picrosides P-I and P-II were further utilized as standard active compounds for their comparative quantification in 124 collected P. kurroa genotypes. Stock solutions of P-I and P-II were prepared by dissolving 1.0 mg of each compound in 1 ml methanol taken in 5 ml volumetric flask. The stock solutions were then filtered through Whatman filter paper No. 41 and different amounts (10, 20, 40 and 60 μl) of the stock solutions were injected into HPLC columns for preparing four point calibration curves.

Preparation of sample solutions

The sample solutions of different genotypes were prepared by dissolving the corresponding dried methanol extract (1.0 mg) in 1 ml methanol using the same procedure (as was done for the standards for preparation of calibration curves) in triplicate.

HPLC analysis

HPLC analysis was carried out using Schimadzu HPLC system with µ-bond pack C-18 column at a wavelength of 274 nm with flow rate of 1 ml/min. The column temperature was maintained at 25 °C. Different compositions of the mobile phase using Water:Methanol (65:35) were tested and desired resolution of P-I and P-II, with symmetrical and reproducible peaks, was achieved. Peaks corresponding to P-I and P-II were observed at retention times of 9.4 and 8.3 min, respectively.

Results

RAPD fingerprinting

Twenty two RAPD primers generated a total of 140 amplification products in 91 genotypes with an average of 6.3 bands per primer and showed a high polymorphism of 83.5%. The number of scored markers ranged from 4 with OPA19 to 9 with primer OPJ16. Different primers generated different number of polymorphic bands (Table 2). The order of polymorphism in analyzed populations was found to be Rahala population > Manvarsar > Thangu > Dayara > Arampatri > Jhuni > Tungnath > Kedarnath > Sonamarg > Temza (Table 3).

Table 2.

Total number of bands (n), number of monomorphic bands (mb), number of polymorphic bands (pb), percentage of polymorphism (pp), polymorphic information content (PIC) and marker index (MI) calculated for RAPD, ISSR primers and AFLP primer combinations in P. kurroa

| Primer (Sequence) | n | mb | pb | pp | PIC | MI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RAPD | ||||||

| OPA17 (GACCGCTTGT) | 5 | 1 | 4 | 80 | 0.24 | 0.77 |

| OPK03 (CCAGCTTAGG) | 7 | 1 | 6 | 85.7 | 0.36 | 1.85 |

| OPA16 (AGCCAGCGAA) | 6 | 1 | 5 | 83.3 | 0.26 | 1.08 |

| OPA19 (CAAACGTCGG) | 4 | 2 | 2 | 50 | 0.22 | 0.22 |

| OPC10 (TGTCTGGGTG) | 6 | 2` | 4 | 66.6 | 0.24 | 0.64 |

| OPH09 (TGTAGCTGGG) | 6 | 1 | 5 | 83.3 | 0.29 | 1.21 |

| OPH19 (CTGACCAGCC) | 5 | 1 | 4 | 80 | 0.22 | 0.7 |

| OPJ16 (CTGCTTAGGG) | 9 | 1 | 8 | 88.8 | 0.33 | 2.35 |

| OPJ08 (CATACCGTGG) | 8 | 1 | 7 | 87.5 | 0.34 | 2.1 |

| OPT01 (GGGCCACTCA) | 7 | 1 | 6 | 85.7 | 0.33 | 1.7 |

| OPR17 (CCGTACGTAG) | 8 | 1 | 7 | 87.5 | 0.32 | 1.96 |

| OPJ09 (TGAGCCTCAC) | 7 | 1 | 6 | 85.7 | 0.33 | 1.7 |

| OPR06 (GTCTACGGCA) | 7 | 1 | 6 | 85.7 | 0.36 | 1.85 |

| OPR05 (GACCTAGTGG) | 5 | 1 | 4 | 80 | 0.23 | 0.74 |

| OPJ18 (TGGTCGCAGA) | 7 | 1 | 6 | 85.7 | 0.28 | 1.5 |

| OPT02 (GGAGAGACTC) | 6 | 1 | 5 | 83.3 | 0.26 | 1.08 |

| OPR12 (ACAGGTGCGT) | 7 | 0 | 7 | 100 | 0.41 | 2.87 |

| OPT18 (GATGCCAGAC) | 6 | 1 | 5 | 83.3 | 0.28 | 1.17 |

| OPC13 (AAGCCTCGTC) | 7 | 1 | 6 | 85.7 | 0.32 | 1.65 |

| OPK15 (CTCCTGCCAA) | 6 | 1 | 5 | 83.3 | 0.31 | 1.29 |

| OPC03 (GGGGGTCTTT) | 5 | 0 | 5 | 100 | 0.43 | 2.15 |

| OPC16 (CACACTCCAG) | 6 | 2 | 4 | 66.6 | 0.29 | 0.77 |

| Total | 140 | 23 | 117 | 83.5 | 0.3 | 1.42 |

| ISSR | ||||||

| UBC808 (AGA GAG AGA GAG AGA GC) | 6 | 1 | 5 | 83.3 | 0.29 | 1.21 |

| UBC811 (GAG AGA GAG AGA GAG AC) | 7 | 2 | 5 | 71.4 | 0.26 | 0.93 |

| UBC815 (CTC TCT CTC TCT CTC TG) | 5 | 1 | 4 | 80 | 0.3 | 0.96 |

| UBC824 (TCT CTC TCT CTC TCT CG) | 6 | 1 | 5 | 83.3 | 0.32 | 1.33 |

| UBC826 (ACA CAC ACA CAC ACA CC) | 5 | 1 | 4 | 80 | 0.29 | 0.93 |

| UBC834 AGA GAG AGA GAG AGA GYT) | 6 | 1 | 5 | 83.3 | 0.31 | 1.29 |

| UBC836 (AGA GAG AGA GAG AGA GYA) | 5 | 0 | 5 | 100 | 0.37 | 1.35 |

| UBC840 (GAG AGA GAG AGA GAG AYT) | 6 | 1 | 5 | 83.3 | 0.28 | 0.88 |

| UBC841 (GAG AGA GAG AGA GAG AYC) | 7 | 2 | 5 | 71.4 | 0.23 | 0.82 |

| UBC842 (GAG AGA GAG AGA GAG AYG) | 8 | 2 | 6 | 75 | 0.23 | 0.59 |

| UBC844 (CTC TCT CTC TCT CTC TRA) | 6 | 0 | 6 | 100 | 0.4 | 1.15 |

| UBC849 (GTG TGT GTG TGT GTG TYA) | 6 | 2 | 4 | 66.6 | 0.24 | 0.64 |

| UBC850 (GTG TGT GTG TGT GTG TYC) | 5 | 1 | 4 | 80 | 0.36 | 1.15 |

| UBC854 (TCT CTC TCT CTC TCT CRG) | 5 | 1 | 4 | 80 | 0.33 | 1.06 |

| UBC858 (TGT GTG TGT GTG TGT GRT) | 5 | 1 | 4 | 80 | 0.31 | 0.99 |

| Total | 88 | 17 | 71 | 80.6 | 0.3 | 1.01 |

| AFLP | ||||||

| E-ACG/ M-CAT | 31 | 11 | 20 | 64.5 | 0.24 | 3.1 |

| E-AGG/ M-CTT | 54 | 19 | 35 | 64.8 | 0.22 | 4.5 |

| E-AAG/ M-CTG | 52 | 14 | 38 | 73 | 0.28 | 7.78 |

| E-AGG/M-CAA | 38 | 10 | 28 | 73.6 | 0.29 | 5.98 |

| E-AAC/ M-CAT | 52 | 8 | 44 | 84.6 | 0.31 | 11.54 |

| E-AAC/ M-CTT | 54 | 13 | 41 | 75.9 | 0.33 | 10.27 |

| E-ACG/ M-CTA | 46 | 16 | 30 | 65.2 | 0.31 | 6.06 |

| Total | 327 | 91 | 236 | 72.1 | 0.28 | 7.03 |

Table 3.

Proportion of genetic diversity detected by RAPD, ISSR and AFLP markers for various populations of P. kurroa

| Population | Sample size | Na | Ne | H | I | Number of PL | Percentage of PL | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RAPD | ISSR | AFLP | RAPD | ISSR | AFLP | RAPD | ISSR | AFLP | RAPD | ISSR | AFLP | RAPD | ISSR | AFLP | RAPD | ISSR | AFLP | ||

| Pop 1 (Arampatri) | 10 | 1.2558 | 1.3488 | 1.1682 | 1.1873 | 1.2667 | 1.11 | 0.1037 | 0.1495 | 0.0624 | 0.1503 | 0.2158 | 0.0921 | 33 | 31 | 55 | 25.58 | 35.22 | 16.82 |

| Pop 2 (Sonamarg) | 7 | 1.1628 | 1.2791 | 1.156 | 1.1044 | 1.1884 | 1.1026 | 0.0601 | 0.1052 | 0.0575 | 0.0893 | 0.1543 | 0.0848 | 21 | 25 | 51 | 16.28 | 28.4 | 15.6 |

| Pop 3 (Manvarsar) | 4 | 1.5116 | 1.6279 | 1.471 | 1.3077 | 1.4189 | 1.3593 | 0.1848 | 0.2424 | 0.2515 | 0.2773 | 0.3577 | 0.2779 | 66 | 55 | 219 | 51.16 | 62.5 | 66.97 |

| Pop 4 (Temza) | 4 | 1.124 | 1.3023 | 1.1743 | 1.0919 | 1.2222 | 1.1176 | 0.0511 | 0.1247 | 0.0669 | 0.0742 | 0.1812 | 0.0986 | 16 | 27 | 57 | 12.4 | 30.68 | 17.43 |

| Pop 5 (Thangu) | 5 | 1.3876 | 1.1163 | 1.2905 | 1.2498 | 1.0836 | 1.2056 | 0.1446 | 0.0463 | 0.1156 | 0.2145 | 0.0675 | 0.1689 | 50 | 15 | 95 | 38.76 | 17.04 | 29.05 |

| Pop 6 (Kedarnath) | 10 | 1.2093 | 1.3721 | 1.1835 | 1.1455 | 1.2602 | 1.1007 | 0.0809 | 0.1476 | 0.0593 | 0.1189 | 0.2157 | 0.0897 | 27 | 33 | 60 | 20.93 | 37.5 | 18.35 |

| Pop 7 (Dayara) | 6 | 1.2791 | 1.2558 | 1.2661 | 1.1718 | 1.2291 | 1.1897 | 0.0985 | 0.1198 | 0.1062 | 0.147 | 0.1688 | 0.1549 | 36 | 23 | 87 | 27.91 | 26.13 | 26.61 |

| Pop 8 (Tungnath) | 4 | 1.2326 | 1.2558 | 1.263 | 1.1765 | 1.1773 | 1.1886 | 0.0964 | 0.099 | 0.1066 | 0.1395 | 0.1454 | 0.1556 | 30 | 23 | 86 | 23.26 | 26.13 | 28.3 |

| Pop 9 (Jhuni) | 5 | 1.2481 | 1.3256 | 1.2202 | 1.1579 | 1.2583 | 1.1497 | 0.0893 | 0.1393 | 0.0851 | 0.1327 | 0.1998 | 0.1253 | 32 | 29 | 72 | 24.81 | 32.95 | 22.02 |

| Pop 10 (Rahala) | 36 | 1.6822 | 1.7674 | 1.6636 | 1.3596 | 1.5195 | 1.4069 | 0.2148 | 0.2945 | 0.2336 | 0.3255 | 0.4314 | 0.3466 | 88 | 68 | 217 | 68.22 | 77.27 | 66.36 |

| Overall | 91 | 1.8992 | 1.8837 | 1.8899 | 1.5722 | 1.5787 | 1.5665 | 0.3366 | 0.324 | 0.3246 | 0.4961 | 0.4765 | 0.4815 | 117 | 71 | 236 | 83.5 | 80.6 | 72.17 |

na, observed number of alleles; ne, effective numbers of alleles; h, Nei’s gene diversity; I, Shannon’s diversity index; PL, Polymorphic loci

ISSR fingerprinting

A total of 88 amplification products were generated by 15 ISSR primers with an average frequency of 5.8 bands per primer. The total number of bands produced by an individual primer ranged from 5 in UBC815, UBC826, UBC836, UBC850, UBC854 and UBC858 to 8 in UBC842. Seventy one bands (80.6%) were observed to be polymorphic among analyzed 91 genotypes. (Table 2). The order of percentage polymorphism between populations was found to be Rahala > Manvarsar > Kedarnath > Arampatri > Jhuni > Temza > Sonamarg > Dayara, Tungnath > Thangu.

AFLP fingerprinting

Seven primer combinations resulted in a total of 327 unambiguously scorable bands. The number of bands per primer combination ranged from 31 in E-ACG/ M-CAT to 54 in E-AAC/ M-CTT and E-AGG/ M-CTT, resulting in an average of 46.7 bands per primer combinations. Two hundred thirty-six (72.1%) bands were observed to be polymorphic among the analysed populations (Table 2). However, the number of polymorphic bands within a population ranged from 51 (15.6%) in Sonamarg to 219 (66.9%) in Manvarsar population (Table 3). The order of percentage polymorphism between populations was found to be Manvarsar > Rahala > Thangu > Dayara > Tungnath > Jhuni > Kedarnath > Temza > Arampatri > Sonamarg. The number of polymorphic fragments for each primer pair in the analyzed samples varied from 20 in E-ACG/M-CAT to 44 in E-AAC/M-CAT with an average of 33.8 per primer pair. Based on the number of polymorphic fragments, different levels of polymorphism, ranging from 64.5% in E-ACG/ M-CAT to 84.6% in E-AAC/ M-CAT were observed (Table 2).

To find out the discriminatory power of various primers, indices such as average PIC and MI were calculated (Table 2). The PIC and MI values varied from (0.22 to 0.41 and 0.77 to 2.35) for RAPD, (0.22 to 0.33 and 3.12 to 11.54) for AFLP, and (0.23 to 0.40 and 0.59 to 1.35) for ISSR, respectively.

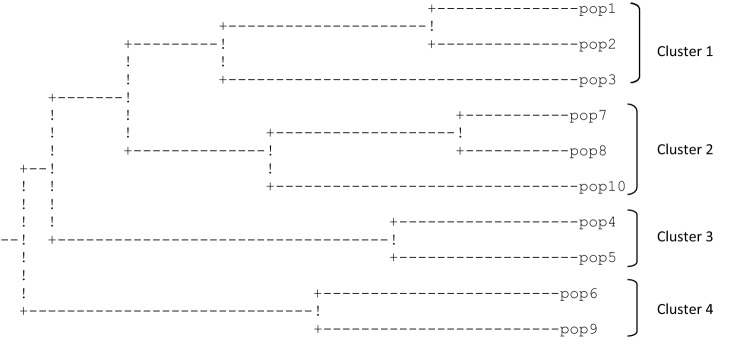

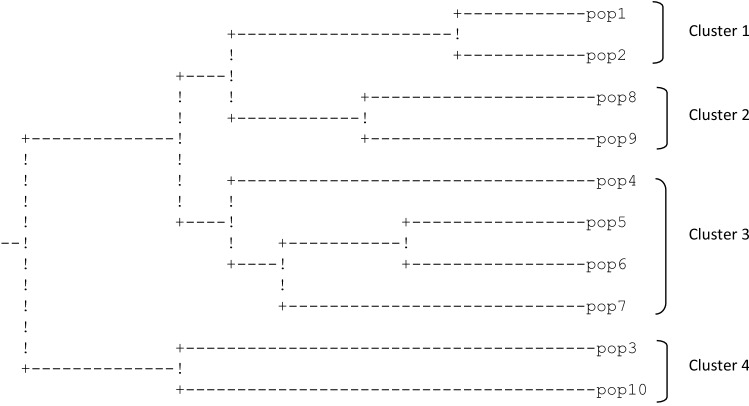

Cluster analysis

The clustering pattern obtained with RAPD and AFLP marker data showed good congruence with each other. The RAPD and AFLP based dendrograms (Figs. 3 and 4) grouped 91 genotypes into 4 main clusters arranged largely as per their corresponding states/regions. Cluster 5 included individuals from Uttarakhand and Himachal Pradesh while Cluster 6 represented 2 distinctly different samples from Manvarsar (J&K). Individuals of a single population were mostly arranged in population-specific node in their region specific cluster. No difference in the general topology of the main clusters was found between two dendrograms. In contrast to RAPD and AFLP based dendrograms there was no discrete region-wise clustering in ISSR data based dendrogram except for the genotypes collected from Arampatri and Sonamarg. In all, there were 5 clusters (Fig. 5). Two genotypes from Manvarsar were again observed to be most divergent in ISSR based dendrogram as well, clustering at a similarity value of 0.48 with the other groups.

Fig. 3.

UPGMA dendrogram of the 91 P. kurroa genotypes based on RAPD marker data

Fig. 4.

UPGMA dendrogram of the 91 P. kurroa genotypes based on AFLP marker data

Fig. 5.

UPGMA dendrogram of the 91 P. kurroa genotypes based on ISSR marker data

The Mantel’s test (Mantel 1967) resulted in a very good fit of co-phenetic values (0.907 ≤ r ≤ 0.934) for all the three marker systems, indicating that the dendrograms obtained with the three marker systems are a proper representation of their respective similarity matrices.

PCoA analysis based on pairwise distant matrix grouped the samples into four region/state specific clusters. All genotypes from Manvarsar, and few genotypes from Uttarakhand and Himachal Pradesh showed divergence from their region specific cluster (Fig. 6). Bayesian model based STRUCTURE analysis revealed a pattern similar to UPGMA based dendrogram for all the analyzed populations, except for a few admixtures. A peak was produced by STRUCTURE analysis at delta K = 4 (Fig. 7a). The 10 analyzed populations from four states/regions could be classified into four clusters indicating the existence of four distinct gene pools (Fig. 7b).

Fig. 6.

Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) of P. kurroa genotypes

Fig. 7.

STRUCTURE analysis based clustering of 91 individuals of P. kurroa. a Plot showing corresponding value of delta K, b Histogram showing distinct genetic pools in population-wise clustering

Partitioning of genetic variation

A hierarchical AMOVA showed that most of the RAPD (43.4%), ISSR (66.2%) and AFLP (48.7%) markers’ diversity were due to variation between individuals within populations. The variation due to differences among regions was 35.3%, 23.9% and 32.0%, respectively. A low proportion of genetic variations (21.2%, 9.7% and 19.2%) detected by RAPD, ISSR and AFLP markers respectively, was due to differences among populations within regions/states (Table 4). Average F-statistics indices Fst, Fct and Fsc were 0.56, 0.35 and 0.32 for RAPD markers, 0.33, 0.23 and 0.12 for ISSR markers and 0.51, 0.32 and 0.28 for AFLP markers, respectively. All values were found to be highly significant (p < 0.001).

Table 4.

Apportionment of genetic diversity between and within populations of P. kurroa genotypes by AMOVA

| Source of variation | d.f | Sum of squares | Variance component | Percentage of variation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RAPD | ||||

| Among regions | 3 | 723.723 | 8.59 | 35.39 |

| Among populations within regions | 6 | 334.430 | 5.14 | 21.20 |

| Within populations | 81 | 853.605 | 10.53 | 43.41 |

| Total | 90 | 1911.758 | 24.27 | |

| ISSR | ||||

| Among regions | 3 | 126.131 | 1.50 | 23.93 |

| Among populations within regions | 6 | 57.528 | 0.61 | 9.78 |

| Within populations | 81 | 338.362 | 4.17 | 66.29 |

| Total | 90 | 522.022 | 6.30 | |

| AFLP | ||||

| Among regions | 3 | 1445.334 | 16.96 | 32.01 |

| Among populations within regions | 6 | 693.332 | 10.21 | 19.28 |

| Within populations | 81 | 2091.422 | 25.82 | 48.72 |

| Total | 90 | 4230.088 | 53.00 | |

Significance tests (1023 permutations)

Bold values indicate that the signify the maximum percentage of variation detected with AMOVA analysis

The overall rate of gene flow (Nm) between populations was moderate for RAPD (0·8434) and AFLP (0.9882) to high for ISSR (1.6093), which means the numbers of migrants per generation are less than one for RAPD and AFLP based data and more than one for ISSR marker based estimates.

The observed numbers of alleles at each locus in a population varied from 1.1240 in Temza to 1.6822 in Rahala, 1.1163 in Thangu to 1.7674 in composite population of Rahala, and, 1.1560 in Sonamarg to 1.6636 in Rahala, with RAPD, ISSR and AFLP markers, respectively. The effective number of alleles in the population ranged from 1.0919 in Temza to 1.3596 in Rahala, 1.0836 in Thangu to 1.5195 in Rahala, and 0.3593 in Manvarsar to 1.4069 in Rahala, with RAPD, ISSR and AFLP markers, respectively. Nei’s gene diversity within the species was 0.3366 for RAPD, 0.3240 for ISSR and 0.3246 for AFLP based estimates. Shannon’s diversity index varied for each population from 0.0742 for Temza to 0.3255 for Rahala, 0.0675 for Thangu to 0.4314 for Rahala, and 0.0848 for Sonamarg to 0.3466 for Rahala, with RAPD, ISSR and AFLP markers, respectively (Table 3).

Pairwise genetic distance were computed for all the populations. The average genetic distance among populations was 0.320, 0.1820 and 0.287, with RAPD, ISSR and AFLP, respectively. The genetic distance among all populations varied from 0.0703 between Dayara and Tungnath to 0.4949 between Arampatri and Temza with RAPD, from 0.0505 between Arampatri and Sandukmore to 0.3740 between Manvarsar and Thangu with ISSR, and from 0.0353 between Arampatri and Sandukmore to 0.4220 between Manvarsar and Temza with AFLP marker data sets. UPGMA dendrograms based on RAPD, ISSR, and AFLP data were constructed to reveal the genetic relationships between populations (Figs. 8, 9 and 10). The RAPD and AFLP based dendrograms were congruent with each other, demarcating 10 populations into region specific four main groups. With a few exceptions, ISSR based dendrogram also segregated 10 populations into their regional groups.

Fig. 8.

Nei’s genetic distance dendrogram of P. kurroa populations based on RAPD marker data

Fig. 9.

Nei’s genetic distance dendrogram of P. kurroa populations based on ISSR marker data

Fig. 10.

Nei’s genetic distance dendrogram of P. kurroa populations based on AFLP marker data

Characterization of isolated compounds

Picrorhiza kurroa dried rhizomes (500 g) were extracted in methanol (1 L). The residue obtained after solvent evaporation was column chromatographed over silica gel (60–120 mesh). Elution of column with CHCl3:MeOH (96:4) gave 1 g of compound A, which gave pink colour with vanillin-sulphuric acid (5%), indicating the presence of iridoid moiety. In 1H NMR spectrum double doublets at δ 2.24 (J = 5.0 & 2.1 Hz) 2.48 (dd, J = 9.6 & 7.9 Hz) and 4.38 (J = 12.4 & 6.0 Hz) ppm were assigned to H-9, H-5 and H-6 protons. Doublets at δ 3.84 (J = 8.07 Hz), 4.14 (J = 12.9 Hz), 4.42 (J = 12.9 Hz), 4.74 (J = 8.0 Hz), 4.86 (J = 9.0 Hz), 5.22 (J = 8.9 Hz) ppm for one proton each were assigned to H-7, H-10a, H-10b, H-6a', H-6b and H-1′ protons respectively. The multiplets between δ 3.27–3.62, 5.06 and 5.14 ppm were assigned to the sugar protons, H-4 and H-1 protons respectively. Also, doublets at δ 7.66 (J = 16.0 Hz) and 6.48 (J = 16.0 Hz) ppm for one proton each were assigned to Hα and Hβ protons of t-cinnamoyl ester moiety and a five proton multiplet between δ 7.32–7.50 ppm was assigned to the aromatic protons. Compound A with molecular formula C24H28O11 (492.48) showed M + 1 peak at 493.170 in the ESI–MS spectrum. The above spectral data indicated the compound A as picroside-I (P-I).

Further elution of column with CHCl3:MeOH (90:10),1.2 g of another white coloured compound B was obtained, which responded positively for iridoids with vanillin-sulphuric acid (5%). The IR spectrum of the compound B showed the presence of a peak at 3400–3200 cm−1, while in 1H NMR spectrum a triplet at δ 2.60 (J = 8.2 Hz) and a double doublet at 5.08 (J = 9.0, 6.7 Hz) ppm for one proton each were aggined to H-9 and H-6 protons respectively. A doublet at δ 3.78 (J = 9.2 Hz), 3.82 (J = 13.1 Hz), 4.12 (d, J = 13.1 Hz), 4.80 (d, J = 6.0 Hz), 5.02 (d, J = 9.0 Hz), 5.12 (J = 9.7 Hz) and 6.45 (d, J = 6.0 Hz) ppm were assigned to H-7, H-10a, H-10′b, H-4, H-1′, H-1 and H-3 protons. The multiplets between δ 3.20–3.56 and 2.68 ppm were assigned to the sugar protons and H-5 protons respectively. A singlet at δ 3.93 ppm for three protons was assigned to the methoxy group and a singlet at δ 7.81 ppm was assigned to the hydroxyl proton. Two doublets for one proton each at δ 6.90 (J = 8.7 Hz) and 7.56 ppm were assigned to the ortho and meta coupled protons H-5′′ and H-2′′ protons, while the double doublet at δ 7.60 ppm was assigned to H-6′′ proton, which indicated the presence of vanilloyl group. Compound B with molecular formula C23H28O13 (512.46) showed M + 1 peak at 513.157 in the ESI–MS spectrum. The above data indicated that the compound B was picroside-II (P-II).

Quantification of picrosides P-I and P-II

Well defined peaks were observed for picrosides P-I and P-II in the analyzed samples (Fig. 11a–c). Peak purity tests were done by comparing UV–Visible spectra of P-I and P-II in standard and sample track. The peaks corresponding to P-I and P-II were symmetrical and well separated from other peaks. The quantified range of P-I and P-II content in the analyzed samples collected from different locations is detailed in Table 5.

Fig. 11.

Chromatogram of standards picroside-1 (a), picroside-II (b) and Tungnath genotype showing major peaks for two isolates (c)

Table 5.

Range of P-I and P-II detected from P. kurroa collected from different Himalayan Locations

| S. no. | Region | Location | Altitude (mt.) | Picroside I (%) | Picroside II (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Jammu & Kashmir | Arampatri | 3000 | 0.02–0.68 | 0.10–0.56 |

| 2 | Sikkim | Temza | 3000 | 0.32–1.66 | 0.01–1.41 |

| 3 | Uttarakhand | Jhuni | 2008 | 0.19–0.55 | 0.0–0.87 |

| 4 | Kedarnath | 3553 | 0.0–2.0 | 0.0–0.63 | |

| 5 | Dayara | 3580 | 0.12–4.04 | 0.06–1.3 | |

| 6 | Tungnath | 3680 | 0.13–4.15 | 0.0–0.54 | |

| 7 | Himachal Pradesh | Sairopa | 1800 | 0.10–0.29 | 0.03–0.81 |

| 8 | Rampur | 2020 | 0.02–0.46 | 0.0–0.83 | |

| 9 | Holi | 2200 | 0.22–1.03 | 0.04–0.92 | |

| 10 | Saptadhar | 2200 | 0.21–0.87 | 0.05–0.69 | |

| 11 | Grahan | 2298 | 0.01–0.75 | 0.03–0.49 | |

| 12 | Kafnu | 2496 | 0.63–0.86 | 0.01–0.69 | |

| 13 | Sainj | 2733 | 0.16–4.07 | 0.04–3.18 | |

| 14 | Parsuthach | 2750 | 1.24–3.54 | 0.12–0.16 | |

| 15 | Rahala | 2800 | 0.20–0.59 | 0.43–1.0 | |

| 16 | Pulga | 2895 | 0.13–2.56 | 0.04–0.24 | |

| 17 | Solang nallah | 3060 | 0.02–0.29 | 0.002–0.76 | |

| 18 | Furkia | 3250 | 0.1–0.13 | 1.0–1.1 | |

| 19 | Piyyankar | 3613 | 0.24–0.65 | 0.002–0.32 | |

| 20 | Rohtang | 3980 | 0.18–1.26 | 0.10–0.79 | |

| 21 | Gulaba | 4000 | 0.22–1.03 | 0.02–0.43 | |

| 22 | Mani Mahesh | 4080 | 0.37–2.75 | 0.04–0.57 |

Bold values indicate that the signify the maximum concentration (at different altitudes) of either P-I and P-II detected in the analyzed genotypes

The levels of P-I and P-II for individual genotypes varied substantially and for a representative sample have been shown in Fig. 12. The P-I concentration in individual samples varied from 0.01 percent in genotype ‘PK116’ from Grahan to 4.15% in a genotype ‘PK92’ from Tungnath. The P-II concentration in individual samples varied from 0.01% in individual genotypes from Temza and Kafnu to 3.18% in genotype ‘PK68’ from Sainj.

Fig. 12.

Representative comparative histogram of P-I and P-II extracted from rhizome of P. kurroa genotypes. X-axis represents number of genotypes from the respective location while Y-axis represents concentration (%) of picrosides

The P-II concentration (> 1.0%) was detected in the genotypes of Sainj, Temza, Dayara, Furkia and Rahala. Similarly, more than 1.0% P-I concentration was detected in the genotypes of Tungnath, Sainj, Dayara, Parsuthach, Mani Mahesh, Pulga, Kedarnath, Temza, Rohtang, Holi and Gulaba. On a closer observation, it was found that low P-I concentration in a genotype was associated with largely a high P-II concentration as evident in Fig. 12 and Table 5. Accordingly, most of the genotypes were either P-I or P-II rich, and a few only showed almost similar amount of both P-I and P-II (Fig. 12).

Discussion

This study provides comprehensive insights into the genetic and phytochemical diversity across 91 and 124 P. kurroa genotypes belonging to 10 geographically distinct Indian Himalayan populations, respectively. Molecular DNA marker analysis revealed a sufficient level of polymorphism by ISSR (80.6%), RAPD (83.5%) and AFLP (72.1%) analysis. The data generated was found to be useful in estimating the level of genetic diversity and understanding the population structure in P. kurroa. The average PIC and MI values for RAPD (0.30, 1.42), ISSR (0.30, 1.01) and AFLP markers (0.28, 7.03), even with the limited no. of genotypes available in some analyzed population(s) indicated that these markers are capable of providing useful information on genetic diversity.

Revelation of a higher level of polymorphism by RAPD as compared to AFLP markers as seen in the present study have also been reported in Antirrhinum microphyllum (Torres et al. 2003), Digitalis minor (Sales et al. 2001), Hordeum vulgare (Russell et al. 1997), Olive (Belaj et al. 2003) and Valeriana jatamansi (Kumar et al. 2014). Further, the incongruence of ISSR data based dendrogram with both RAPD and AFLP based dendrograms, indicates that each of the analyzed markers spans different regions of the genome and genetic relationships and distances are dependent on genome coverage and/or the type of sequence variation recognized by each marker system (Powell et al. 1996; Pejic et al. 1998; Degani et al. 2001). Further, the inherent biasedness in the information generated by dominant RAPD, ISSR and AFLP markers was compensated in the present analysis by analyzing a large number of loci with all the three markers system, across many genotypes. The unbiased analysis is further supported by high levels of significance, which suggests that results are robust (Lynch and Milligan 1994).

AMOVA values estimates within and among populations for RAPD (43.4%, 35.3%), ISSR (66.2%, 23.9%) and AFLP (48.7%, 32.0%), respectively indicated that populations are not genetically divergent, although the genotypes within the populations show a high level of genetic diversity. F-statistics was used to estimate the proportion of genetic variability among populations (FST), among populations within groups (FSC) and among groups (FCT). Average F indices FST, FCT and FSC values were 0.56, 0.35 and 0.32 for RAPD markers, 0.33, 0.23 and 0.12 for ISSR markers and 0.51, 0.32 and 0.28 for AFLP markers, respectively, indicating thereby that most of the observed variability is due to variation among genotypes within population followed by among populations.

The calculated estimates of Nei’s gene diversity for RAPD (0.33), ISSR (0.32) and AFLP (0.32) data sets for P. kurroa fell in between a high value of, for example 0.49 reported in wild populations of outcrossing Brassica oleracea (Lannér-Herrera et al. 1996) and 0.274 and 0.278 reported for narrow endemic species of Allium aaseae and A. simillium (Smith and Pham 1996), respectively. Analysis of gene flow (Nm) values for RAPDs (0.8434) and AFLPs (0.9882) to comparatively higher levels for ISSRs (1.6093) indicated moderate levels of gene flow. The analyzed samples were collected from a distance spanning 1000 km separated by geographical barriers that might have allowed little pollination and seed dispersal. The estimated levels of gene flow and Nei’s gene diversity values indicate that P. kurroa, which is largely an outcrossing species, has had a continuous habitat across the Indian Himalayas running from western to eastern fronts that has now been fragmented due to over-exploitation and/or habitat loss. The fragmentation reduces populations to smaller isolates which are subjected to increasing genetic drift, inbreeding and reduced gene flow (Carvalho et al. 2019).

Co-phenetic correlation values of Mantel’s test are 0.907 to more than 0.934 for the three marker systems. This validates the trees developed on the basis binary matrices are a true representation of their similarities. Region specific clusters with NJ, PCoA and Bayesian model based STRUCTURE analysis were observed with all the three analyzed markers with small intermixing in some groups indicating limited gene flow between them. The admixtures might reflect past genetic exchange events as STRUCTURE only estimates global ancestory by implementing different models of population structure to the data.

Although, a fairly high overall genetic variation was reflected within the analyzed populations, the level of polymorphism detected among populations of P. kurroa is low and might prove detrimental in the evolutionary and ecological context of the species (Barrett and Kohn 1991).

A high level of genetic diversity revealed in the present investigations in P. kurroa populations fall in line with the earlier reports by Katoch et al. (2013) and Singh and Sharma (2020) in the species. Outcrossing perennials have generally been reported to exhibit higher levels of genetic diversity and lower levels of population differentiation (Hamrick and Godt 1990, 1996). As observed in many outcrossing species, populations isolated by distance can set forth independent genetic differentiation in them to accumulate divergent alleles (Prentice et al. 2003) and bring in evolutionary differences. This can in turn affect the population structure.

HPLC analysis has been used as a preferred method for isolation, chemical characterization, and quantification of phytochemicals in many medicinal plant species (Han et al. 2008; Sultan et al. 2008; Thapliyal et al. 2012; Song et al. 2015; Mehra et al. 2017; Thakur et al. 2020).The concentration of picrosides in dry rhizomes of different populations of P. kurroa, has been found to vary with altitude in different ecogeographical regions in Himalayas. In Himachal Pradesh, the highest concentration of P-I and P-II was observed between an altitude of 2733 m (Sainj) to 2750 m (Parsuthach), in Uttarakhand it was observed between 3580 m (Dayara) to 3680 m (Tungnath), while in Kashmir and Sikkim regions, it was observed at 3000 m altitude in Arampatri and Temza, respectively. In general, more picrosides content was observed in genotypes growing at higher altitudes. With an increase in altitude, cold weather period increases resulting in slow growth and consequently increasing the content of picrosides per gram of the tissue. Similar observations have previously been made by Sultan et al (2016) who showed higher P-I (2.78–5.18%) and P-II (2.53–5.39%) variation in P. kurroa collections from 2799 to 3750 m altitudes. In the present study, we quantified slightly lower ranges of P-II (0.01–4.15%) and P-II (0.01–3.18%) in genotypes collected from altitudes 1800–4080 m which might be due to effect of changes in growth conditions, season of collection and local geographical and climatic condition on accumulation of picrosides.

Further, it was interesting to observe that low P-I content in a given genotype was generally observed to be associated with high P-II content suggesting an interconversion of PI and PII. The present analysis allowed identification of P-I rich, P-II rich or both P-I and P-II rich genotypes. Similar observations were made by Kumar et al. (2017), who identified genotypes PKST-3 and PKST-5 as maximum P-II and minimum P-I genotypes, while PKST-16 and PKST-18 were identified as minimum P-II and maximum P-I genotypes. They proposed that metabolic network of picrosides I and II biosynthesis is very complex. An increase in P-II upon reduction in P-I indicated that P-I and P-II skewed from a common metabolic node and P-I and P-II biosynthesis is regulated by metabolic modulations (Kumar et al. 2017). Based on present analysis, the genotypes of Sainj, Dayara, Parsuthach, Tungnath, Furkia and Temza may be considered as superior genotypes with higher quantity of P-I and P-II.

Upon correlation of data generated by genetic and phytochemical markers, it was observed that some genotypes with higher concentration of either P-I or P-II, like from Temza and Tungnath populations did not exhibit much genetic polymorphism. Similar negative correlation between genotypic and phytochemical diversity has been observed in Ocimum basilicum (De Masi et al. 2006), Thymus caespititius (Trindade et al. 2008), Cymbopogon sp. (Kumar et al. 2009) and Zataria multiflora (Hadian et al. 2011). On the other hand, both a high level of genetic polymorphism as well as picrosides P-I or P-II in Rahala population, especially in genotypes from Grahan, Rohtang, Holi, Mani Mahesh and particularly Sainj clearly displayed a positive correlation between the two marker systems as seen previously in Podophyllum hexandrum (Sultan et al. 2008).

To sum up, although the present comprehensive molecular and phytochemical analysis in P. kurroa revealed a high genetic diversity and various statistical analysis indicated that populations did not show much genetic divergence, and the observed genetic diversity resides largely among the genotypes within the populations. Nevertheless, on the basis of molecular and phytochemical markers, the genotypes from Sainj, Parsuthach, and Furkia (Himachal Pradesh), Arampatri and Manvarsar (Jammu and Kashmir), Dayara, Kedarnath and Tungnath (Uttarakhand) and Temza and Thangu (Sikkim) with high genetic heterozygosity and picrosides content can contribute towards a probable core collection of most variable genotypes in P. kurroa which can be further characterized and used for multiplication, conservation and genetic improvement purposes.

Conclusions and conservation implications

In the present study, both molecular DNA and phytochemical markers efficiently partitioned the genetic variation in different populations of P. kurroa. Diversity and clustering analysis grouped the populations distinctly providing a clear spatial population structure depicting limited gene flow between them. Most of the genetic variability was reflected at the intra-population level with low inter-population variation. The present study has helped in the demarcation of most divergent P. kurroa genotypes with high percentage of genetic polymorphism and picrosides content. These elite genotypes may potentially be used for further characterization, multiplication, industrial utilization and conservation of P. kurroa germplasm. An imperative conservation strategy in P. kurroa may include integrating in situ and ex situ management processes, setting up of protected areas and cultivation practices of divergent P. kurroa genotypes. Intensive botanical surveys followed by characterization of genetic diversity by various approaches can be really helpful in identification of elite P. kurroa genotypes. Additionally, involvement of all the stakeholders, i.e. local communities, academicians and industries at all levels of planning, execution, monitoring and assessment of conservation processes can result in better resource management. Further, biotechnological interventions including molecular markers and phytochemical quantification analysis as done in the present analysis followed by micropropagation of identified elites can help support the conservation program in the species. The present information on genetic and phytochemical diversity, gene flow and population structure of P. kurroa might be useful to understand the evolutionary pathways, prioritize suitable sampling strategies for resource management, sustained use and conservation of this important medicinal species.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grant for scientific research from the Department of Biotechnology, Government of India. Avinash Kumar acknowledges SRF from CSIR during his Ph.D. The authors are thankful to Prof. (Retd.) Ravinder Raina, Department of Forest Products, Dr. Y. S. Parmar University of Horticulture and Forestry, Solan, Himachal Pradesh, India, for easing collection of germplasm from Himachal. The authors extend their sincere gratitude to anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments that helped in the improvement of the manuscript.

Author’s contribution

Contributors Role Taxonomy (CRediT): Avinash Kumar: Sample Collection, Methodology, Investigation (molecular profiling), Validation, Formal analysis, Writing—Original Draft preparation. Ambika: Methodology, Investigation (Chemical profiling), Formal analysis, Validation, (chemoprofiling). Amita Kumari: Analysis. Rachhaya.Mallikarjun Devarumath: Sample Collection. Rakesh Thakur: Analysis. Manju Chaudhary: Analysis. Pradeep Pratap Singh: Analysis (Chemical profiling). Shiv Murat Singh Chauhan: Conceptualization, Supervision (Chemical profiling work). SN Raina: Conceptualization, Resources, Overall Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition. Vijay Rani Rajpal: Supervision, Visualization, Validation, Writing and editing.

Funding

This work was supported by grant for scientific research from the Department of Biotechnology, Government of India.

Availability of data materials

Available on request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Consent for publication

All authors have given their consent for publication in the journal “Physiology and Molecular Biology of Plants”.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Avinash Kumar, Email: avinashkumar@vbu.ac.in.

Vijay Rani Rajpal, Email: vijayrani2@gmail.com.

References

- Akbar S (2020) Picrorhiza kurroa Royle ex Benth. (Plantaginaceae). In: Handbook of 200 medicinal plants: a comprehensive review of their traditional medical uses and scientific justifications. Springer, Cham. 10.1007/978-3-030-16807-0_145

- Barik SK, Rao BR, Haridasan K, Adhikari D, Singh PP, Tiwary R. Classifying threatened species of India using IUCN criteria. Curr Sci. 2018;114:588–595. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett SCH, Kohn JK. Genetic and evolutionary consequences of small population size in plants: implications for conservation. In: Falk DA, Holsinger KH, editors. Genetics and conservation of rare plants. Center for plant conservation. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1991. pp. 3–30. [Google Scholar]

- Belaj A, Satovic Z, Cipriani G, Baldoni L, Testolin R, Rallo L, Trujillo I. Comparative study of the discriminating capacity of RAPD, AFLP and SSR markers and of their effectiveness in establishing genetic relationships in olive. Theor Appl Genet. 2003;107:736–744. doi: 10.1007/s00122-003-1301-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat WW, Dhar N, Razdan S, Rana S, Mehra R, Nargotra A, et al. Molecular characterization of UGT94F2 and UGT86C4, two Glycosyltransferases from Picrorhiza kurrooa: comparative structural insight and evaluation of substrate recognition. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(9):e73804. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharjee S, Bhattacharya S, Jana S, Baghel DS. A review on medicinally important species of Picrorhiza. IJPRBS. 2013;2(4):1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho YGS, Vitorino LC, de Souza UJB, Bessa LA. Recent trends in research on the genetic diversity of plants: implications for conservation. Diversity. 2019 doi: 10.3390/d11040062. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chesnokov Y, Artem’eva A. Evaluation of the measure of polymorphism. Agric Biol. 2015;50(5):571–578. [Google Scholar]

- Costa R, Pereira G, Garrido I, Tavares-de-Sousa MM, Espinosa F. Comparison of RAPD, ISSR, and AFLP molecular markers to reveal and classify Orchardgrass (Dactylis glomerata L.) germplasm variations. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(4):e0152972. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0152972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Masi L, Siviero P, Esposito C, Castaldo D, Siano F, Laratta B. Assessment of agronomic, chemical and genetic variability in common basil (Ocimum basilicum L.) Eur Food Res Technol. 2006;223(2):273. doi: 10.1007/s00217-005-0201-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Debnath P, Rathore S, Walia S, Kumar M, Devi R, Kumar R. Picrorhiza kurroa: a promising traditional therapeutic herb from higher altitude of western Himalayas. J Herb Med. 2020;23:100358. doi: 10.1016/j.hermed.2020.100358. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Degani C, Rowland LJ, Saunders AJA, Hokanson SC, Ogden EL, Golan-Goldhirsh A, Galletta GJ. A comparison of genetic relationship measures in strawberry (Fragaria x ananassa Duch.) based on AFLPs, RAPDs, and pedigree data. Euphytica. 2001;117:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Earl DA. STRUCTURE HARVESTER: a website and program for visualizing STRUCTURE output and implementing the Evanno method. Conserv Genet Resour. 2012;4:359–361. doi: 10.1007/s12686-011-9548-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Evanno G, Regnaut S, Goudet J. Detecting the number of clusters of individuals using the software STRUCTURE: a simulation study. Mol Ecol. 2005;14:2611–2620. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02553.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Excoffier L, Laval G, Schneider S. Arlequin ver. 3.1: An integrated software package for population genetics data analysis. Evol Bioinform Online. 2005;1:47–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falush D, Stephens M, Pritchard JK. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data: dominant markers and null alleles. Mol Ecol Notes. 2007;7:574–578. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-8286.2007.01758.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadian J, Ebrahimi SN, Mirjalili MH, Azizi A, Ranjbar H, Friedt W. Chemical and genetic diversity of Zataria multiflora Boiss. accessions growing wild in Iran. Chem Biodiver. 2011;8:176–188. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.201000070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamrick JL, Godt MJW. Allozyme diversity in plant species. In: Brown AHD, Clegg MT, Kahler AL, Weir BS, editors. Plant population genetics, breeding and genetic resources. Sunderland: Sinauer; 1990. pp. 43–63. [Google Scholar]

- Hamrick JL, Godt MJW. Effects of life history traits on genetic diversity in plant species. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1996;351:1291–1298. [Google Scholar]

- Han T, Hu Y, Zhou SY, et al. Correlation between the genetic diversity and variation of total phenolic acids contents in Fructus xanthii from different populations in China. Biomed Chromatogr. 2008;22:478–486. doi: 10.1002/bmc.956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoch M, Hussain MA, Ahuja A. Comparison of SSR and cytochrome P-450 markers for estimating genetic diversity in Picrorhiza kurrooa L. Plant Syst Evol. 2013;299:1637–1643. [Google Scholar]

- Katoch M, Fazli IS, Suri KA, et al. Effect of altitude on picroside content in core collections of Picrorhiza kurrooa from the north western Himalayas. J Nat Med. 2011;65:578–582. doi: 10.1007/s11418-010-0491-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnamurthy A. The Wealth of India. New Delhi: Publication and Information Directorate, CSIR; 1969. p. 49. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A, Rajpal VR, Raina R, Choudhary M, Raina SN. Nuclear DNA assay of the wild endangered medicinal and aromatic Indian Himalayan Valeriana jatamansi germplasm with multiple DNA markers: implications for genetic enhancement, domestication and ex situ conservation. Plant Syst Evol. 2014;300(9):2061–2071. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar J, Verma V, Goyal A, Shahi AK, Saproo R, Sangwan RS, Qazi GN. Genetic diversity analysis in Cymbopogon species using DNA markers. Plant Omics. 2009;2(1):20. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar N, Sharma SK. A new aromatic ester from Picrorhiza kurroa Royle ex Benth. J Pharmacogn Phytochem. 2014;3(1):96–98. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar V (2019) OMICS‐Based approaches for elucidation of picrosides biosynthesis in Picrorhiza Kurroa. 10.1002/9781119509967.ch8

- Kumar V, Bansal A, Chauhan RS. Modular design of picroside-II biosynthesis deciphered through NGS transcriptomes and metabolic intermediates analysis in naturally variant chemotypes of a medicinal herb, Picrorhiza kurroa. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:564. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar V, Sharma N, Sood H, et al. Exogenous feeding of immediate precursors reveals synergistic effect on picroside-I biosynthesis in shoot cultures of Picrorhiza kurroa Royle ex Benth. Sci Rep. 2016;6:29750. doi: 10.1038/srep29750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lannér-Herrera C, Gustafsson M, Fält AS, Bryngelsson T. Diversity in natural populations of wild Brassica oleracea as estimated by Isozyme and RAPD analysis. Genet Resour Crop Evol. 1996;43:13–23. [Google Scholar]

- Lone SA, Qazi PH, Gupta S. Genetic diversity of Epimedium elatum (Morren & Decne) revealed by RAPD characterization. Curr Bot. 2018;9:41–46. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch M, Milligan BG. Analysis of population genetic structure with RAPD markers. Mol Ecol. 1994;3:91–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294x.1994.tb00109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahajan R, Kapoor N, Singh I. Somatic embryogenesis and callus proliferation in Picrorhiza kurroa Royle ex. Benth J Exp Biol Agric Sci. 2016;4(2):201–209. [Google Scholar]

- Mandal S, Mukhopadhyay S. New iridoid glucoside from Picrorhiza kurroa Royle ex Benth. Indian J Chem Sect B Org Chem Incl Med Chem. 2004;43(5):1023–1025. [Google Scholar]

- Mantel N. The detection of disease clustering and a generalized regression approach. Can Res. 1967;27:209–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masood M, Arshad M, Qureshi R, Sabir S, Amjad MS, Qureshi H, Tahir Z. Picrorhiza kurroa: An ethnopharmacologically important plant species of Himalayan region. Pure Appl Biol. 2015;4(3):407–417. [Google Scholar]

- Mehra TS, Raina R, Rana RC, Chandra P, Pandey PK. Elite chemo-types of a critically endangered medicinal plant Picrorhiza kurroa Royle ex Benth from Indian Western Himalaya. J Pharmacogn Phytochem. 2017;6(5):1679–1682. [Google Scholar]

- Naik PK, Alam MA, Singh H, Goyal V, Parida S, Kalia S, Mohapatra T. Assessment of genetic diversity through RAPD, ISSR and AFLP markers in Podophyllum hexandrum: a medicinal herb from the Northwestern Himalayan region. Physiol Mol Biol Plants. 2010;16(2):135–148. doi: 10.1007/s12298-010-0015-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nayar MP, Sastry ARK. Red data plants of India. New Delhi: CSIR Publication; 1990. p. 271. [Google Scholar]

- Nazarzadeh Z, Onsori H, Akrami S. Genetic diversity of bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) genotypes using RAPD and ISSR molecular markers. J Genet Resour. 2020;6(1):69–76. [Google Scholar]

- Pejic I, Ajmone-Marsan P, Morgante M, Kozumplik V, Castiglioni P, Taramino G, Motto M. Comparative analysis of genetic similarity among maize inbred lines detected by RFLPs, RAPDs, SSRs and AFLPs. Theor Appl Genet. 1998;97:1248–1255. [Google Scholar]

- Powell W, Morgante M, Andre C, Hanafey M, Vogel J, Tingey S, Rafalski A. The comparison of RFLP, RAPD, AFLP and SSR (microsatellite) markers for germplasm analysis. Mol Breed. 1996;2:225–238. [Google Scholar]

- Prentice HC, Malm JU, Mateu-Andres I, Segarra-Moragues JG. Allozyme and chloroplast DNA variation in island and mainland populations of the rare Spanish endemic, Silene hifacensis (Caryophyllaceae) Conserv Genet. 2003;4:543–555. [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard JK, Stephens M, Donnelly P. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics. 2000;155:945–959. doi: 10.1093/genetics/155.2.945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohlf FJ (1998) NTSYS-pc: numerical taxonomy and multivariate analysis system version 2.02K. Applied Biostatistics, New York

- Russell JR, Fuller JB, MaCaulay M, Hatz BG, Jhoor A, Powel W, Waugh R. Direct comparison of levels of genetic variation among barley accessions detected by RFLPs, AFLPs, SSRs and RAPDs. Theor Appl Genet. 1997;95:1161–1168. [Google Scholar]

- Sales E, Sergio GN, Mus M, Segura J. Population genetic study in the Balearic endemic plant species Digitalis minor (Scrophulariaceae) using RAPD markers. Am J Bot. 2001;88(10):1750–1759. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarwat M, Das S, Srivastava PS. Analysis of genetic diversity through AFLP, SAMPL, ISSR and RAPD markers in Tribulus terrestris, a medicinal herb. Plant Cell Rep. 2008;27:519–528. doi: 10.1007/s00299-007-0478-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shitiz K, Pandit S, Chanumolu S, Sood H, Singh H, Singh J, Chauhan R. Mining simple sequence repeats in Picrorhiza kurroa transcriptomes for assessing genetic diversity among accessions varying for picrosides contents. Plant Genet Resour. 2017;15(1):79–88. [Google Scholar]

- Shitiz K, Sharma N, Pal T, Sood H, Chauhan RS. NGS Transcriptomes and enzyme inhibitors unravel complexity of picrosides biosynthesis in Picrorhiza kurroa Royle ex. Benth PLoSONE. 2015;10(12):e0144546. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0144546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh P, Nag A, Parmar R, Ghosh S, Bhau BS, Sharma RK. Genetic diversity and population structure of endangered Aquilaria malaccensis revealed potential for future conservation. J Genet. 2015;94:697–704. doi: 10.1007/s12041-015-0580-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh P, Sharma RK. Development of informative genic SSR markers for genetic diversity analysis of Picrorhiza kurroa. J Plant Biochem Biotechnol. 2020;29:144–148. [Google Scholar]

- Smith JF, Pham TV. Genetic diversity of the narrow endemic Allium aaseae (Alliaceae) Am J Bot. 1996;83:717–726. [Google Scholar]

- Song BH, Varshney VK, Mittal N, Ginwal HS. High levels of diversity in the phytochemistry, ploidy and genetics of the medicinal plant Acorus calamus L. Med Aromat Plants S. 2015;1:002. doi: 10.4172/2167-0412.S1-002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Soni D, Grover A. "Picrosides" from Picrorhiza kurroa as potential anti-carcinogenic agents. Biomed Pharmacother. 2019;109:1680–1687. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.11.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sultan P, Jan A, Pervaiz Q. Phytochemical studies for quantitative estimation of iridoid glycosides in Picrorhiza kurroa Royle. Bot Stud. 2016;57:7. doi: 10.1186/s40529-016-0121-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sultan P, Shawl AS, Ramtekeb PW, Koura A, Qazia PH. Assessment of diversity in Podophyllum hexandrum by genetic and phytochemical markers. Sci Hortic. 2008;115:398–408. [Google Scholar]

- Thakur RK, Rajpal VR, Raina SN, Kumar P, Sonkar A, Joshi L. UPLC-DAD assisted phytochemical quantitation reveals a sex, ploidy and ecogeography specificity in the expression levels of selected secondary metabolites in medicinal Tinospora cordifolia: implications for elites’ identification program. Curr Top Med Chem. 2020;20:698. doi: 10.2174/1568026620666200124105027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thani PR, Sharma YP, Kandel P. Phytochemical studies on Indian market samples of drug “Kutki” (Picrorhiza kurroa Royle ex Benth) Re J Agr Forest Sci. 2018;6(2):1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Thapliyal S, Mahadevan N, Nanjan MJ. Analysis of Picroside I and Kutkoside in Picrorhiza kurroa and its Formulation by HPTLC. Int J Res Pharm Biomed Sci. 2012;3(1):25–30. [Google Scholar]

- Thein SI, Wallace RR. The use of synthetic oligonucleotides as specific hybridization probes in the diagnosis of genetic disorders. In: Davis KE, editor. Human genetic disease: a practical approach. Oxford: IRL; 1986. pp. 33–50. [Google Scholar]

- Thiyagarajan M, Venkatachalam P. Assessment of genetic and biochemical diversity of Stevia rebaudiana Bertoni by DNA fingerprinting and HPLC analysis. Ann Phytomed. 2015;4(1):79–85. [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari SS, Pandey MM, Srivastava S, Rawat A. KTLC densitometric quantification of picrosides (picroside-I and picroside-II) in Picrorhiza kurroa and its substitute Picrorhiza scrophulariiflora and their antioxidant studies. Biomed Chromatogr. 2012;26:61–68. doi: 10.1002/bmc.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres E, Iriondo JM, Pérez C. Genetic structure of an endangered plant, Antirrhinum microphyllum (Scrophulariaceae): Allozyme and RAPD analysis. Am J Bot. 2003;90:85–92. doi: 10.3732/ajb.90.1.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trindade H, Costa MM, Sofia BLA, Pedro LG, Figueiredo AC, Barroso JG. Genetic diversity and chemical polymorphism of Thymus caespititius from Pico, Sao Jorge and Terceira islands (Azores) Biochem Syst Ecol. 2008;36(10):790–797. [Google Scholar]

- Vaidya AB, Antarkar DS, Doshi JC, Bhatt AD, Ramesh V, Vora PV, Perissond D, Baxi AJ, Kale PMJ. Picrorhiza kurroa (Kutki) Royle ex Benth as a hepatoprotective agent experimental and clinical studies. J Postgrad Med. 1996;42:105–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh FC, Boyle T, Yeh Z, Xiyan JM (1999) POPGENE Version 1.31: Microsoft Window based freeware for population genetic analysis. University of Alberta and center for International Forestry Research, Edmonton.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Available on request.