Abstract

Elicitor-induced defense response against potential plant pathogens has been widely reported in several crop plants; however, transcriptome dynamics underlying such defense response remains elusive. Our previous study identified and characterized a novel elicitor, κ-carrageenan, from Kappaphycus alvarezii, a marine red seaweed. Our preliminary studies have shown that the elicitor-treatment enhances the tolerance of a susceptible tomato cultivar to Septoria lycopersici (causative agent of leaf spot disease). To gain further insights into the genes regulated during elicitor treatment followed by pathogen infection, we have performed RNA-Seq experiments under different treatments, namely, control (untreated and uninfected), elicitor treatment, pathogen infection alone, and elicitor treatment followed by pathogen infection. To validate the results, forty-three genes belonging to five different classes, namely, ROS activating and detoxifying enzyme encoding genes, DEAD-box RNA helicase genes, autophagy-related genes, cysteine proteases, and pathogenesis-related genes, were chosen. Expression profiling of each gene was performed using qRT-PCR, and the data was correlated with the RNA-seq data. Altogether, the study has pinpointed a repertoire of genes that could be potential candidates for further functional characterization to provide insights into novel elicitor-induced fungal defense and develop transgenic lines resistant to foliar diseases.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12298-021-00970-y.

Keywords: κ-carrageenan, Leaf spot disease, RNA-Seq, Tomato, Septoria lycopersici, Transcriptome

Introduction

Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) is the second-largest consumed vegetable known for consumption in different forms, including raw, cooked, processed, and fermented (Chakraborty and Kumar 2020). Though it originated from western South and Central America, the plant is now grown worldwide, which has constituted a significant contributor to the global economy (Hammond 2017 and Schreinemachers et al. 2018). The plant is well suitable for cultivation in fields as well as under controlled hydroponic and glasshouse conditions. Pests and pathogens are the biotic factors that challenge the tomato yield and productivity, and these factors are reported to cause up to 100% loss (Blancard 2012). A recent report shows that tomato is a host for more than two hundred pathogens (Singh et al. 2017). This includes fungal diseases: late blight (Phytopthora infestans), early blight (Alternaria solani), leaf spot (Septoria lycopersici), damping off (Pythium aphanidermatum), powdery mildew (Oidium lycopersici), fusarium wilt (Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici) and verticilium wilt (Verticilium dahliae); Bacterial diseases: bacterial spot (Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria), bacterial speck (Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato), and bacterial Wilt (Pseudomonas solanacearum); and viral diseases caused by Tomato spotted wilt virus, Tomato yellow leaf curl virus, Tomato mosaic virus, Tomato chlorotic spot virus, Tomato ringspot virus, Tobacco mosaic virus, and Tomato mottle virus.

Among the different fungal diseases, leaf spot disease caused by the fungus, Septoria lycopersici cause immense damage to tomato cultivation (Panthee and Chen 2010). The fungus could infect the plants at any stage by entering through stomata or penetrating the epidermis (Osbourn et al. 1995). Typical infection is characterized by the appearance of circular or angular lesions. Pycnidia, the fruiting bodies of the fungus, could be found in the middle of the lesions. Prolonged infection results in the merger of lesions leading to yellowing of the leaves (Kapooria and Ndunguru 1998). The dried leaf then falls-off from the plant, which could serve as a source for the fungal spore to spread to other parts through air, water and any medium (Fones and Gurr 2015). Though the fungus does not infect the fruits, the falling-off of infected leaves affects the plant's growth and development, resulting in the immature development of the plant (Panthee and Chen 2010). In addition to infecting tomato, S. lycopersici had also been reported to cause leaf spot disease in other Solanaceae species, including eggplant, potato, petunia, horsenettle, and black nightshade. Recently, the pathogen has been found to infect Stevia rebaudiana (Hastoy et al. 2019).

Studies on the pathogenesis of S. lycopersici and host resistance mechanism in the purview of developing resistance to leaf spot disease in tomato are limited. An α-tomatine, belonging to saponin family (steroidal glycoalkaloid), has been shown to confer antifungal activity in the resistant tomato cultivars; however, hydrolysis of α-tomatine by an extracellular tomatinase enzyme was reported in S. lycopersici (Arneson and Durbin 1967). Martin-Hernandez et al. (Martin-Hernandez et al. 2000) had mutated the tomatinase gene in S. lycopersici to show that the infection and lesion formation were not compromised in tomato plants infected by the mutant strain. The study suggested that tomatinase might involve in suppressing the plant defense response; however, the precise mechanism underlying this finding remains elusive. Jasmonate-deficient mutant tomato plants (def1) infected with S. lycopersici showed no difference in the infection level compared to wild-type (Thaler et al. 2004). An endophytic Fusarium solani strain has been shown to confer resistance to tomato plants against S. lycopersici through modulating the host ethylene signaling pathway (Kavroulakis et al. 2007).

Developing disease resistance could be broadly achieved through two approaches, namely, molecular breeding and transgene-based strategies. Identification of resistant germplasm (cultivated or wild) is important for breeding, and on the other hand, expression of genes conferring resistance must be identified and characterized for the latter approach. In case of developing leaf spot resistant varieties in tomato, either approach has been proven unsuccessful (Melton et al. 1998; Panthee and Chen 2010), and therefore, alternate strategies gain importance. Elicitors are being used to induce the innate immunity that can protect the plant from imminent infection (Chandra et al. 2015; Goupil et al. 2012). Elicitors are recognized by the receptors that trigger the early response through microbe/pathogen-associated molecular pattern (MAMP/PAMP)-triggered immunity (PTI) and effector-triggered immunity (ETI) (Kim et al. 2005). The onset of PTI and ETI also communicates the signal to distal tissues through systemic acquired resistance (SAR) and induced systemic resistance (ISR) (Muthamilarasan and Prasad 2013). These altogether enhance the defensive capacity of the plant against the upcoming pathogen. Several biopolymers were identified as elicitors due to their organic nature and eco-friendliness (Stadnik and de Freitas 2014). We have recently isolated κ-carrageenan from the red seaweed, Kappaphycus alvarezii that showed potential elicitor activity against anthracnose disease (caused by Colletotrichum gloeosporioides) in chili plants (Mani and Nagarathnam 2018).

In tomato, several elicitor molecules were shown to induce resistance to different pathogens and pests (Basse et al. 1992; Boughton et al. 2006; Mandal et al. 2013; Paudel et al. 2014; Chakraborty et al. 2016); however, no in-depth study been conducted to understand the genes that are regulated by elicitor treatment at a genome-wide level. In the present study, we aimed to study the transcriptome dynamics during κ-carrageenan priming in a susceptible tomato cultivar (cv. PKM 1) infected with S. lycopersici. Transcriptome sequencing facilitates the study of gene expression at genome-wide level, and comparing the transcriptomes of control (untreated and uninfected), pathogen infection, elicitor alone treatment, and elicitor followed by pathogen treatments. So far, the present study is the first of its kind to provide a global picture on transcriptome dynamics during elicitor-induced defense as compared to pathogen alone and elicitor alone treatments.

Materials and methods

Preparation and characterization of κ-carrageenan

Extraction and characterization of κ-carrageenan from Kappaphycus alvarezii was carried out as described earlier (Mani and Nagarathnam 2018). Briefly, the wet material of Kappaphycus alvarezii was brought to the laboratory and thoroughly rinsed with tap water to remove the impurities. Approximately 100 g of biomass was air-dried at 50 °C until complete dryness is achieved (weight remains constant), and 1 g each of both dry and wet material were minced separately and heated with 100 mL of distilled water for 1 h followed by constant stirring at room temperature for 12 h. The resulting residues were referred to as dry aqueous warm and wet aqueous warm, respectively. Similarly, carrageenan was extracted from both dry and wet minced materials by cold water with constant stirring at room temperature for 12 h. The resulting residues were referred to as dry aqueous cold and wet aqueous cold, respectively. Carrageenan was separated from the above residues using a filter cloth and was filtered through Whatman filter paper (no. 2). The filtrate was treated with various solvents, including ethanol, methanol and propanol [1:3 (V/V)], and stored at 4–6 °C for four days to promote the precipitation of polysaccharides. After polysaccharide precipitation, samples were centrifuged at 4000xg for 30 min, the precipitates were collected and dissolved in a minimum quantity of water, and high-molecular-weight crude polysaccharide preparations were obtained by lyophilization and stored at 4 °C. The infrared (IR) spectra of the total extracted carrageenan from K. alvarezii, was determined using FT-IR (Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy). One gram of the lyophilized extract was ground with potassium bromide (KBr) powder, dispersed in a KBr disk, and pressed into 1-mm pellets for FT-IR measurements (wavenumber range of 500 and 4000 cm − 1) using 16 scans. For comparison, an authentic carrageenan standard (Aquagiri, Chennai, India) was used.

Plant material, treatments and sampling

Tomato seeds (Solanum lycopersicum, cv. PKM 1) were procured from Horticultural College and Research Institute, Periyakulam, Tamil Nadu, India. The seeds were sown on pots containing commercial manure mixed with vermiculite, and plants were allowed to grow under a 16/8 h day/night light cycle at 25 °C. Twenty-five days old healthy plants were used for further treatments. For elicitor treatment, κ-carrageenan (0.3%) dissolved in 0.1% Tween 20 was sprayed on upper and lower leaves until excess liquid ran-off the leaves. After 24 h of elicitor treatment, one set of the plants were inoculated with Septoria lycopersici (2 × 106 conidia mL−1) by spraying on the leaves (Parker et al. 1997). Control plants were sprayed with 0.1% Tween 20. On the fourth day after infection, the leaf samples (control, elicitor treated, pathogen treated, and pathogen + elicitor) were collected and immediately frozen on liquid nitrogen. The samples are labeled and stored at -80 °C until RNA isolation.

Total RNA isolation and Illumina sequencing

Approximately 100 mg of tissues from each sample were pulverized to a fine powder with mortar and pestle using liquid nitrogen, and 2 ml of TRI reagent (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) was added immediately. The homogenate was incubated for 10–15 min followed by the addition of chloroform (0.2 ml/ml TRI reagent used) and again kept for 15 min. After spinning at 13,000 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C in a tabletop centrifuge (Eppendorf 5415, Germany), the aqueous RNA-containing phase was transferred to a new microcentrifuge tube. RNA was precipitated by adding 0.5 ml isopropanol and incubating for 30 min on ice followed by a 15 min centrifugation at 13,000 rpm. The resultant RNA pellet was washed twice with 80% ethanol (v/v) at 8,000 rpm, air-dried, and dissolved in 20–30 µl sterile DEPC-treated MQ water. The quality of RNA was ascertained by resolving on a denaturing 1.2% (w/v) formaldehyde gel. Nucleic acid quality and quantity were checked by determining absorbance at 230, 260, and 280 nm with NanoDrop 1000 Spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, USA). Samples with A260/A280 ratio of 1.8–2.0 and RIN values above 7.0 were used for sequencing. Sequencing was performed on an Illumina HiSeq 2500 platform. The resultant fastq files were checked for base and sequence quality score distributions, average base content per read, GC distribution in the reads, PCR amplification issues, and over-represented sequences. The sequencing data have been submitted to the NCBI SRA (Bioproject number is PRJNA622013).

Preprocessing, alignment and differential expression analysis

In preprocessing step of the raw reads, the adaptor sequences and low-quality bases were trimmed using AdapterRemoval (version 2.2.0) tool. From the preprocessed reads, ribosomal RNA sequences were removed by aligning the reads with SILVA database using bowtie2 (version 2.2.9), and subsequent workflow using SAMtools (version 1.3.1), Sambamba (version 0.6.7) and BamUtil (version 1.0.13). The preprocessed and rRNA removed reads were then aligned to the tomato genome downloaded from Ensembl Plants (ftp://ftp.ensemblgenomes.org). The alignment was performed using the STAR program (version 2.5.3a). After aligning the reads with transcriptome, differential expression analysis was performed using Cuffdiff program of Cufflinks package (version 2.2.1) at p-value cutoff 0.05 and 0.01 along with log2 fold change cutoff 2.

Validation by quantitative RT-PCR analysis

The total RNA was isolated as mentioned above, first-strand cDNA synthesis was performed using the Protoscript M-MuLVRT kit (NEB, USA) following the manufacturer's instructions. Gene-specific primers for qRT-PCR analysis were designed using the GenScript Real-time PCR Primer Design tool (https://www.genscript.com/ssl-bin/app/primer) with default parameters (Table S1). The qRT-PCR analysis was done by utilizing SYBR Green detection chemistry on a 7900HT Sequence Detection System and software v2.3 (Applied Biosystems). Reactions were performed in a final volume of 20 µl, and the components were 2 µl of 5X diluted cDNA, 250 nM of each primer and 10 µl of Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). The reaction mixture was initially denatured for 2 min at 50 °C, 10 min at 95 °C, and 40 cycles of 15 s at 95 °C, and 1 min at 60 °C. Further, to ensure the amplification specificity and absence of multiple amplicons or primer dimers, melting curve analysis (60 to 95 °C after 40 cycles) and agarose gel electrophoresis were performed. Three technical replicates for three independent biological replicates were maintained, and the transcript abundance normalized to the internal control Tubulin was analyzed using the 2−ΔΔCt method. The PCR efficiency was calculated by the default software itself (Applied Biosystems, USA).

Results and discussion

Processing of raw sequence data and alignment to reference genome

Systemic acquired resistance (SAR) and induced systemic resistance (ISR) are two well-known phenomena of induced resistance that preconditions the plant defense through prior infection or treatment. This results in durable resistance against the subsequent infection by pathogen or disease. The elicitation of salicylic acid-mediated defense cascade promotes systemic expression of broad-spectrum and long-lasting disease resistance in plants, and the use of different elicitors had been reported to be efficient against fungi, bacteria and viruses. A range of elicitor molecules, including oligo- and polysaccharides, peptides, proteins and lipids has been reported to be effective in inducing the defense cascade (Boller 1995); however, the need for novel elicitor molecules is unmet in the scenario of wide range of pathogens causing diseases to plants. Marine macroalgae are rich in polysaccharides that are unique to them and the potential of these polysaccharides as elicitor is not much studied (Hamed et al. 2018). Brown and red algae are known to produce polysaccharides, laminarins, fucans, and carrageenans that were studied to an extent to unravel their resistance-inducing properties in plants. Among these molecules, carrageenan from red algae has recently been shown to provide resistance to anthracnose disease in chilli (Mani and Nagarathnam 2018). We have optimized the procedure for κ-carrageenan extraction and characterization from the seaweed, Kappaphycus alvarezii (Mani and Nagarathnam 2018). The carrageenans of seaweed are fundamentally linear units of D-galactose residues linked with alternating α-(1,3) and ß-(1,4) linkages that are substituted either by one (κ-carrageenan), two (ι-carrageenan), or three (λ-carrageenan) ester-sulfonic groups per digalactose unit. The degree of sulfation of carrageenan molecules determines the specificity and effect of defense signaling in plants (Sangha et al. 2010).

In the present study, transcriptome dynamics of tomato plants challenged with S. lycopersici in the presence and absence of elicitor treatment was examined and compared with plants challenged with pathogen alone and elicitor alone conditions. Total RNA was isolated from control, elicitor treated, pathogen treated, and pathogen + elicitor treated plants were sequenced using Illumina platform, and the reads were processed further. An average of 96.55% of total reads passed ≥ 30 Phred score. The number of paired-end raw reads varied from 52,768,784 (pathogen alone) to 40,017,740 (Elicitor alone). A total of 49,920,817 and 51,077,976 reads were obtained in control and pathogen + elicitor treated samples, respectively. The preprocessed and rRNA removed reads were used for reference-based pair-wise alignment with Tomato Ensembl Plants (Release 41) reference genome. The overall alignment summary is shown in Table 1. The expression of each gene was calculated in terms of FPKM values, and the libraries were then compared to identify the set of up- and down-regulated genes.

Table 1.

Quantitative analysis of raw RNA-seq data

| Statistical content | Control | Elicitor alone | Pathogen alone | Pathogen + elicitor | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Percent | Number | Percent | Number | Percent | Number | Percent | |

| Total reads | 99,841,634 | 100 | 80,035,480 | 100 | 105,537,568 | 100 | 102,155,952 | 100 |

| Filtered reads | 33,702,544 | 33.8 | 25,821,528 | 32.3 | 47,681,972 | 45.2 | 32,724,958 | 32.0 |

| Mapped reads | 30,224,093 | 89.7 | 22,568,527 | 87.4 | 45,280,716 | 95.0 | 28,829,716 | 88.1 |

| Unmapped reads | 3,478,451 | 10.3 | 3,253,001 | 12.6 | 2,401,256 | 5.0 | 3,895,242 | 11.9 |

Differentially expressed genes between treated and control samples

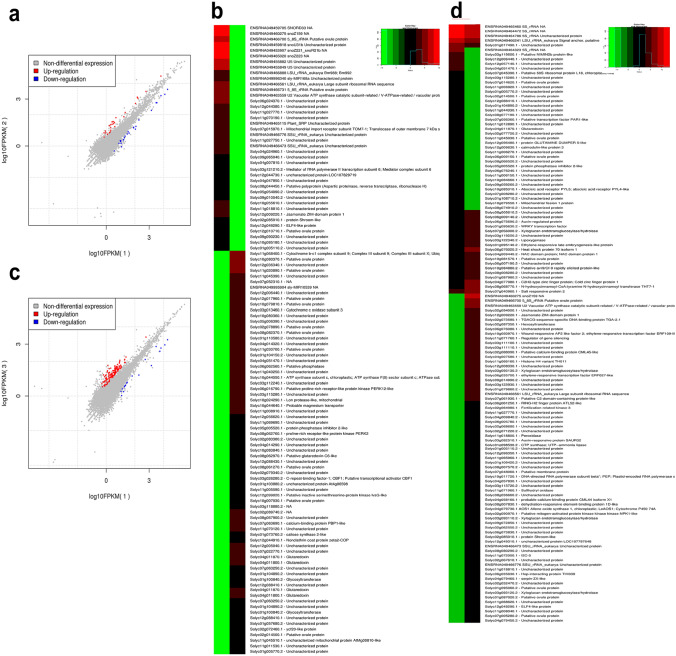

Comparing the differentially expressed genes between control and elicitor alone treated plants showed 23 upregulated and 53 downregulated genes (p-value cutoff of ≤ 0.01) (Fig. 1a; Table S2). Among the upregulated genes, eight were encoding for rRNA, and three were unknown proteins. Two cytochrome P450 monooxygenase genes were upregulated, and the other genes encode for jasmonate ZIM-domain protein, lipoxygenase, mediator of RNA polymerase II transcription subunit, PHD and ring H2 finger proteins and SKP1-like protein. In Arabidopsis, Cytochrome P450 monooxygenase mutants (cyp83a1-3) conferred resistance against powdery mildew fungus Golovinomyces cichoracearum by camalexins accumulation (Liu et al. 2016). Ectopic expression of VqJAZ4, a jasmonate ZIM-domain protein in Chinese wild grape (Vitis quinquangularis) increases the powdery mildew resistance (Uncinula necator) in transgenic Arabidopsis (Zhang et al. 2019). Pepper 9-Lipooxygenase (9-LOX) was shown to provide resistance against Xanthomonas campestris pv vesicatoria (Xcv) and Colletotrichum coccodes infection supported by silencing and transient overexpression data (Hwang and Hwang 2010). In Arabidopsis, mediator subunits MED18 and MED25 have shown to be modulating resistance against dsDNA and ssRNA viruses (Hussein et al. 2020). In case of downregulated genes, four were rRNA encoding genes and 17 were of unknown function. Among the downregulated genes, pathogenesis-related protein PR-1, pentatricopeptide repeat-containing protein, cysteine-rich peptide, F-box protein SKIP5, etc. were notable candidates that showed significant downregulation in control as compared to elicitor treatment (Fig. 1b). These down-regulated genes could also be potential targets for overexpression studies, as in Arabidopsis, overexpression of mulberry PR-1 (MuPR-1) enhanced the resistance of transgenic plants against Botrytis cinerea (Fang et al. 2019). Similarly, proteomic analysis of resistant potato cultivar, CT-206–10 showed an abundance of pentatricopeptide repeat containing proteins against Ralstonia solanacearum (Park et al. 2016). An F-box protein, Avr9/Cf-9–INDUCED F-BOX1 (ACIF1) was reported to regulate the plant defense responses by manipulating methyl jasmonate and abscisic acid pathways in tomato and tobacco (Van Den Burg et al. 2008).

Fig. 1.

FPKM plots and clustering heatmap of top 50% genes differentially expressed in control vs. κ-carrageenan a and b and control vs. S. lycopersici + κ-carrageenan c and d treated samples. The upregulated genes are indicated in red while downregulated are shown in blue

Comparison of control and pathogen + elicitor libraries showed that a total of 106 and 20 genes were up- and downregulated, respectively (Fig. 1c; Table S3). Four of the upregulated genes were encoding for rRNA, and among the others, three were unannotated. The unannotated genes could possess novel roles in the disease resistance; however, further studies are required in this direction to delineate their precise functions. Further, the dataset also showed that transcription factors were predominantly upregulated, and it includes bZIP, ethylene-responsive, WRKY, GRAS family and MAPK. These genes and transcription factors were thoroughly reviewed for their roles in disease response (Pandey et al. 2018). Two bZIP transcription factors cloned from cassava, namely MebZIP3 and MebZIP5, were overexpressed in tobacco, and the transgenic plants showed tolerance to cassava bacterial blight (Li et al. 2017). Ethylene Response Factors (ERFs) belong to the APETALA2/ERF transcription factor family, and they are well-reported for their roles in disease resistance (Müller and Munné-Bosch 2015). Recently, an ERF173 of tobacco was overexpressed to confer resistance to Phytophthora parasitica in transgenic tobacco plants (Yu et al. 2020). In soybean, silencing of MAP kinase kinase (GmMEEK1) confers resistance against downy mildew (Peronospora manshurica) and Soybean mosaic virus (Xu et al. 2018a, b). In cotton, a TIR-NBS-LRR gene GhDSC1 mediates the plant defense response against Verticillium wilt (Li et al. 2019). Several such overexpression studies are reported to confer resistance to diseases, and thus, the present study provides a set of known as well as unknown genes that could serve as candidates for performing similar studies.

Significant upregulation of several genes associated with pathogenesis was observed in the pathogen + elicitor treated samples compared to control (Fig. 1d). TIR-NBS, RLK, Pto-like, CC-NBS-LRR, etc., were a few examples. Such upregulation is notable in pathogen infection and elicitor treatment, as these genes might play a role in elicitor-induced pathogen defense. Toll/interleukin receptor (TIR) domain-containing proteins were shown to be involved in basal defense response of plants (Nandety et al. 2013). Several overexpression studies have proven that TIR-NBS have important roles in conferring resistance to infectious diseases. For example, Xu et al. (2018a, b) had overexpressed a maize NBS-LRR gene, ZmNBS25, in rice and Arabidopsis, and showed that the resistance levels were enhanced to sheath blight disease and P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000, respectively. Similarly, Xun et al. (2019) had overexpressed GmKR3 gene soybean and showed that the transgenic lines were resistant to Soybean mosaic virus. Pto is a well-characterized R gene that belongs to serine-threonine kinases and provide resistance to strains of Pseudomonas syringae expressing AvrPto proteins (Lin and Martin 2007). Receptor-like kinases are the transmembrane proteins primarily involved in pathogen detection and defense (Eckardt 2017). Upregulation of CC-NBS-LRR has also been identified in this study, which has been previously reported to form Pik-H4 interaction with homeodomain transcription factor OsBIDH1 to regulate the plant defense against blast disease (Liu et al. 2017).In case of downregulated genes, six genes were rRNA encoding, and three were of unknown function. Predominantly, housekeeping genes were found to be downregulated, and no interesting candidate genes (already reported in other studies) had been identified in this comparative analysis. However, the present study could provide a lead to understand the susceptibility determinants in tomato for leaf spot disease resistance. Further studies are required in this direction to explore such susceptibility determinants.

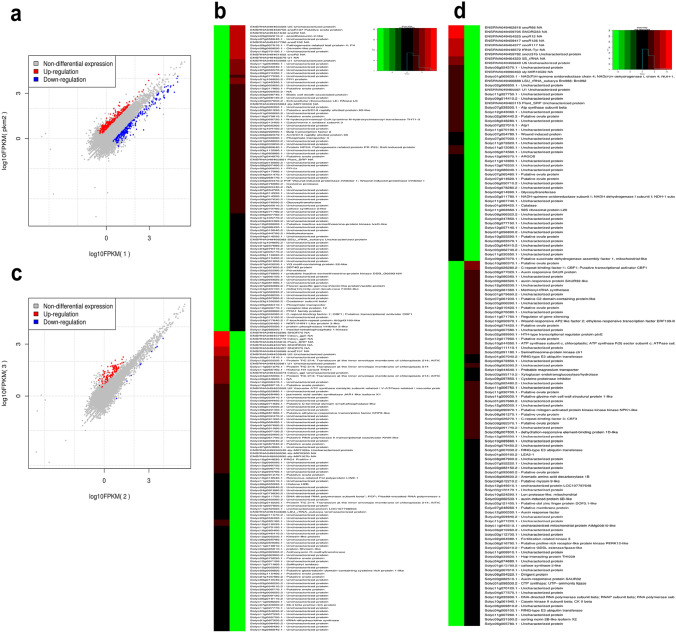

While comparing the DEGs between control and pathogen alone treatment, 163 and 247 genes were found to be up- and downregulated, respectively (Fig. 2a; Table S4). Twenty-four genes were ribosomal protein-encoding in the upregulated list, and genes responsible for replication and repair were found to be highly expressed in these libraries (Fig. 2b). Genes encoding for histone proteins, DNA repair, DNA replication licensing, and polymerase activity were upregulated. Epigenetic regulation by histone proteins such as histone acetylase and deacetylases are well reported in plant-pathogen interaction (Song and Walley 2016). DNA repair protein-encoding gene from maize (ZmRAD51) when overexpressed in Arabidopsis, tobacco and rice, conferred resistance against P. syringae pv. Tomato (Liu et al. 2019). Twenty genes were annotated as unknown function and other genes including 2-oxoglutarate-dependent dioxygenase, Auxin efflux carrier family protein, Cellulose synthase, chaperonin, Ethylene-responsive transcription factor Histone-lysine N-methyltransferase, O-acyltransferase and protein kinases had shown upregulation. The 2-oxoglutarate-dependent dioxygenase has been implicated in governing the metabolite related to defense in Solanum genus, and thus, have a role in plant stress response (Cárdenas et al. 2019; Choudhary et al. 2021). In case of auxin efflux carrier protein, pathogen elicited auxin was reported to modulate the growth responses by altering these carrier proteins in plants (Kazan and Manners 2009). Histone-lysine N-methyltransferase is involved in the epigenetic modulation of effector-triggered immunity components (Lee et al. 2016). In addition, three RLK genes and two kinase interacting domain-containing proteins were also identified in this dataset. Among the downregulated genes, the predominant proportion (46 genes) was rRNA encoding, and twenty-eight were unknown. Several genes belonging to the same family, such as aquaporins, cathepsin, cytochrome P450, hairpin-induced protein-like, osmotin-like, protein inhibitors, etc. were consecutively downregulated. Two pathogenesis-related proteins (Solyc09g007010 and Solyc01g106620) showed downregulation, which could be putative susceptibility determinants. Aquaporins are membrane associated protein implicated in ROS generation to provide defense at the site of pathogen entry (Hirt 2016). In Nicotiana, Cathepsin B was reported to activate programmed cell death to provide defense against Cladosporium fulvum and Erwinia amylovora (Gilroy et al. 2007).

Fig. 2.

FPKM plots and clustering heatmap of top 50% genes differentially expressed in control vs. S. lycopersici alone a and b and κ-carrageenan vs. S. lycopersici + κ-carrageenan c and d treated samples. The upregulated genes are indicated in red while downregulated are shown in blue

Differentially expressed genes between the treated samples

While comparing the datasets of elicitor alone and pathogen + elicitor treated samples, a contrasting difference of 108 upregulated and only 4 downregulated genes were identified (Fig. 2c; Table S5). Among the upregulated genes, twelve were unknown and predominant genes were encoding for Ethylene responsive transcription factor (9 genes) and U-box proteins (7 genes) (Fig. 2d). A tomato U-box E3 ligase, PUB13, was shown to interact with ubiquitinate pattern recognition receptor, FLS2, to promote its degradation by 26S ubiquitin proteasomal pathway, and thus, blocking the FLS2 mediated immunity (Zhou and Zeng 2018). Similarly, genes belonging to the same family were identified to be upregulated in this dataset. This includes WRKY, RING finger, Zinc-finger, and calmodulin-binding proteins. Defense-related protein-encoding genes, namely TIR-NBS, TMV responsive, Pto-like, MAP kinase, RLKs, CC-NBS-LRR, and heat shock proteins. Zinc finger proteins are well reported for their involvement in defense response. Recently, a Zn finger protein, SRG1 from Arabidopsis has been shown to induce immune response after S-nitrosylation against Pst DC3000 (Cui et al. 2018). AtIQM1, a Ca2+ independent calmodulin-binding protein, was reported to interact with catalase 2 to provide immunity against B. cinerea (Tianxiao et al. 2019).In case of downregulated genes, two were rRNA encoding, one was Ribosome-recycling factor and the other was ORF91. In B. cinerea, a ribosomal maturation factor, NOP53 has been shown to induce virulence and pathogenesis by producing ROS in green bean leaves, apple, and strawberry fruit (Cao et al. 2018). No significant downregulated genes common to both datasets had been found.

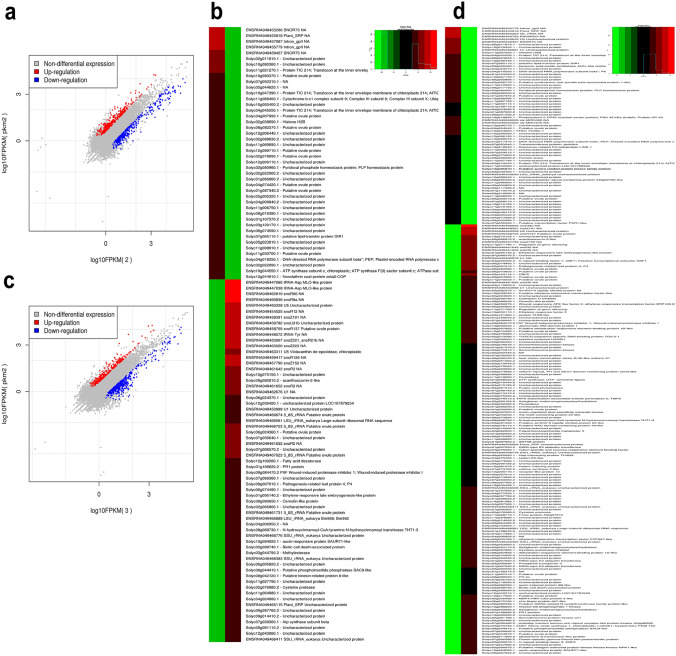

Comparison of elicitor vs. pathogen alone datasets showed 240 upregulated and 283 downregulated genes (Fig. 3a; Table S6). Among the upregulated genes, only four were encoding for rRNA, and five were of unknown function. However, thirty-one genes were found to be ribosomal protein-encoding, and ten were chlorophyll-binding genes. AtCLH1, which encodes for chlorophyllase gene, induces defense against Erwinia carotovora and strikes a balance between plant defense pathways (Kariola et al. 2005). DNA synthesis and repair-related genes were also found to be highly expressed, and this includes DNA topoisomerase, mismatch repair, DNA-directed RNA polymerase, replication licensing factor, etc. (Fig. 3b). It is well reported that the genes related to DNA synthesis and repair help plants cope with the DNA damage caused by pathogens, thus providing stress tolerance (Hu et al. 2016).

Fig. 3.

FPKM plots and clustering heatmap of top 50% genes differentially expressed in κ-carrageenan vs. S. lycopersici alone a and b and S. lycopersici + κ-carrageenan vs. S. lycopersici alone c and d treated samples. The upregulated genes are indicated in red while downregulated are shown in blue

Compared to other datasets, a maximum of eight RLKs were highly expressed, and other pathogenesis-related genes identified in this dataset are ERF, defensin, autophagy, and genes involved in hypersensitive response. An autophagy gene, MaATG8 from banana, has been shown to induce defense against fusarium wilt by activating HR-induced cell death (Wei et al. 2017). In contrast to the above, 75 rRNA encoding genes were identified in the downregulated gene data, and no ribosomal protein-encoding genes were downregulated. Housekeeping genes and a few transcription factors were found to be downregulated in this data, and notably, proteins involved in the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway and spliceosomal complex were downregulated. In soybean, oomycete plant pathogen Phytophthora sojae avirulence effector, PsAvr3c reprograms serine/lysine/arginine-rich proteins (GmSKRPs), which are an integral part of spliceosomal machinery to promote its infection (Huang et al. 2017).

A total of 151 and 356 genes were found to be up- and downregulated, respectively, in pathogen + elicitor vs. pathogen alone comparison (Fig. 3c; Table S7). Among the upregulated genes, 156 were rRNA and ribosomal protein-related, and twenty were unknown proteins. Five receptor-like kinase genes were found to be upregulated; however, no other notable resistance genes or defense responsive genes were present in this dataset (Fig. 3d). Several genes were related to chlorophyll and photosynthesis, RNA helicase, ROS synthesis and detoxification, DNA repair, and histone encoding. In tomato, SlDEAD35, a DEAD-box RNA helicase, has been shown to provide tolerance against Tomato leaf curl New Delhi virus infection (Pandey et al. 2019). On the other hand, ROS has been established as a major signaling pathway in response to pathogen and governs plant immunity (Qi et al. 2017). In case of downregulated genes, a considerable share of the genes was rRNA encoding (40 genes), and among the others, ERF family genes are predominant (16 genes) followed by WRKY (8 genes). Interestingly, ten genes encoded for RLKs and more than two genes encoding for Pto-like, PR, NBS-LRR, MYB TF, RLP, and thaumatin CRT-binding, defensin, etc. were downregulated. Several transcription factors, including AP2 and NAC, were found in this dataset. An Ocimum basilicum PR5 family member (ObTLP1) expressed in Arabidopsis confers resistance against S. sclerotiorum and B. cinerea infections (Misra et al. 2016). Similarly, calreticulin protein (CRT) members from Arabidopsis, namely, AtCRT1/2 and AtCRT3 are involved in modulating plant defense against biotrophic pathogens (Qiu et al. 2012).

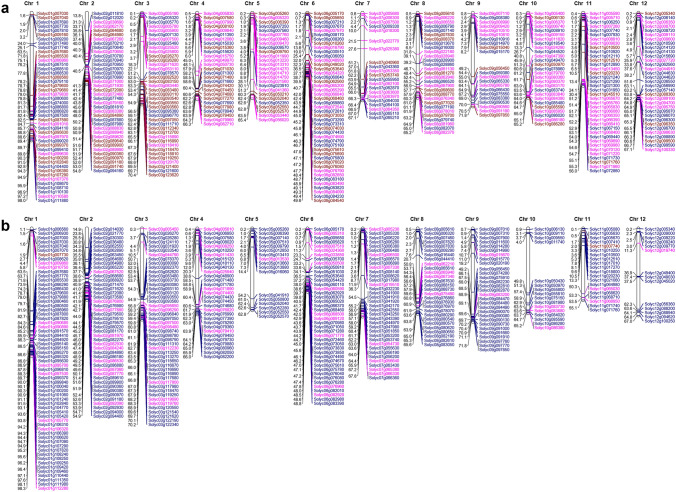

All the up- and down-regulated genes identified by comparing the treated samples (viz., elicitor alone vs. pathogen + elicitor treated; elicitor vs. pathogen alone; and pathogen + elicitor vs. pathogen alone) were mapped onto the twelve chromosomes of tomato to develop a physical map (Fig. 4). A total of 390 upregulated genes and 387 downregulated genes were mapped with an average gene distribution of ~ 32 genes per chromosome. Among the upregulated genes, a maximum number of genes were present on chromosomes 1 and 6 (~ 11.5% each), whereas chromosome 7 has the least number of genes (21; ~ 5.4%) (Fig. 2a). In case of down-regulated genes, a maximum of 62 genes was found on chromosome 1 (~ 16%), whereas chromosome 12 had the least (14; 3.6%) (Fig. 4b). The pattern of distribution of the genes was peculiar on some chromosomes; for example, many genes were congregated in the upper and lower arms of most of the chromosomes compared to other regions. These maps would help identify the candidate genes for map-based cloning and other genomic interventions for further functional characterization.

Fig. 4.

Physical map showing the differentially expressed genes identified by comparing the different treated samples. The total upregulated a and downregulated b genes identified in the datasets of κ-carrageenan vs. S. lycopersici + κ-carrageenan, κ-carrageenan vs. S. lycopersici alone, and S. lycopersici + κ-carrageenan vs. S. lycopersici alone were mapped onto the twelve chromosomes of tomato. The vertical bars represent the chromosomes and the genes are mapped on the right of each bar. The physical position of each gene (in Mb) is marked on the left

Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of candidate gene families

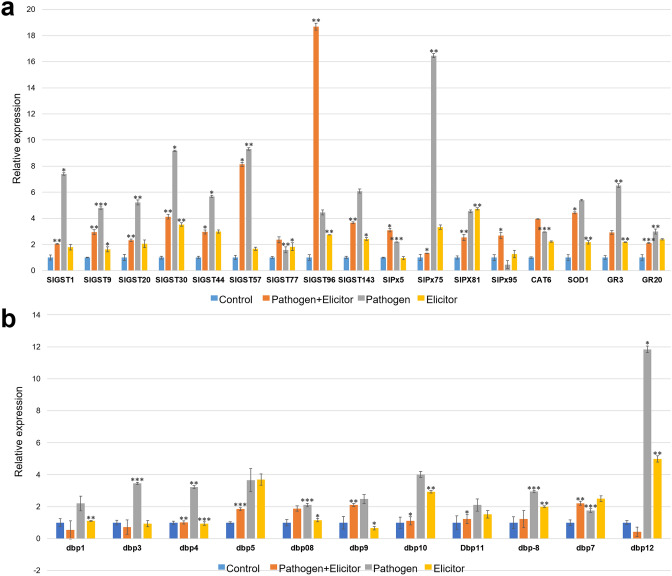

In order to validate the RNA-seq mediated expression profile data, we chose forty-three genes belonging to five different classes, namely, ROS activating and detoxifying enzyme encoding genes, DEAD-box RNA helicase genes, autophagy-related genes, cysteine proteases, and pathogenesis-related genes. The expression pattern of each gene was compared to the RNA-seq data that showed a strong positive correlation (R2 = 0.96), suggesting the reliability of transcriptome data presented in this study. Hypersensitive response in plants is a major outcome of any pathogen challenge, and ROS activating as well as detoxifying enzymes play significant roles in inducing HR response. Expression of seventeen genes involved in enzymatic antioxidant system of tomato including glutathione S transferase (GST), peroxidase (Px), catalase (CAT), superoxide dismutase (SOD) and glutathione reductase (GR) was analyzed in control, elicitor treated, pathogen treated, and pathogen + elicitor conditions (Fig. 5a). All the GST genes showed upregulation during pathogen infection except SlGST96, which showed up to six-fold upregulation in pathogen + elicitor treatment compared to pathogen-alone and elicitor-alone treatments. In the case of Px, elicitor treatment in pathogen-infected plants did not alter the expression of any of the genes; however, the pathogen-alone infection had induced the expression of SlPx75 up to five-folds. The expression of SlPx84 is almost similar in both pathogen-alone and elicitor-alone treatments. SlCAT6 showed an incremental upregulation in pathogen + elicitor treatment compared to the other two treatments. On the contrary, SlSOD1, SlGR3, and SlGR20 were upregulated during pathogen infection, and their transcript abundances reduced during pathogen + elicitor treatments.

Fig. 5.

Relative expression profile of a antioxidant enzymes-encoding genes and (b) DEAD box RNA helicase genes of tomato in control, κ-carrageenan treated, S. lycopersici infected and S. lycopersici + κ-carrageenan conditions. The relative expression ratio of each gene was calculated relative to its expression in control sample. α-Tubulin was used as an internal control to normalize the data. Error bars representing standard deviation were calculated based on three technical replicates for three independent biological replicates. Symbols; *, **, and *** indicate significant differences between control and treated samples (i.e., p < 0.05; p < 0.01 and p < 0.001, respectively) calculated using t test in GraphPad

Pandey et al. (2019) had recently identified the DNA helicase domain-containing protein-encoding genes of tomato and characterized the DEAD-box proteins to derive their role in conferring biotic as well as abiotic stress tolerance. The expression of eleven candidate DEAD-box genes was analyzed in the present study, which showed pathogen-specific upregulation among all the genes (Fig. 5b). However, elicitor treatment in pathogen-infected plants downregulated these genes, and in case of SlDbp1, SlDbp3, and SlDbp12, the downregulation was beyond the levels of expression reported in control plants. On the other hand, elicitor-treatment alone has been shown to induce the transcripts in a few genes, namely, SlDbp10, SlDbp11, SlDbp8, and SlDbp12. In SlDbp7, the expression was higher during elicitor-alone treatment as compared to pathogen-alone and pathogen + elicitor treatments.

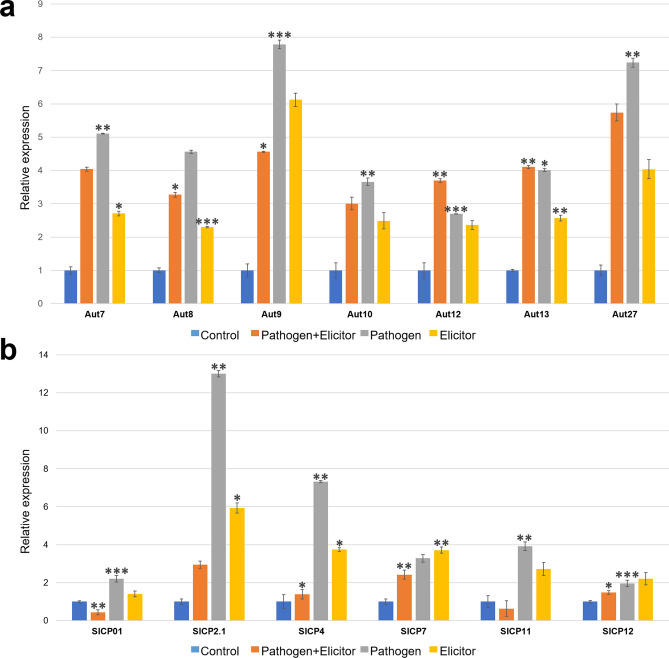

Twenty genes encoding autophagy proteins were in tomato. Based on this data, seven candidate genes were chosen for analyzing their expression (Fig. 6a). Compared to control, all the treatments induced the expression of autophagy genes. Among these, the pathogen-alone treatment showed higher expression of all the genes followed by pathogen + elicitor treatment. On the contrary, the expression of SlAut12 and SlAut13 was higher in pathogen + elicitor treatment than pathogen infection alone, which hints at the involvement of these genes in elicitor-induced defense response.

Fig. 6.

Relative expression profile of a autophagy and b cysteine protease genes of tomato in control, κ-carrageenan treated, S. lycopersici infetecd, and S. lycopersici + κ-carrageenan conditions. The relative expression ratio of each gene was calculated relative to its expression in control sample. α-Tubulin was used as an internal control to normalize the data. Error bars representing standard deviation were calculated based on three technical replicates for three independent biological replicates. Symbols; *, **, and *** indicate significant differences between control and treated samples (i.e., p < 0.05; p < 0.01 and p < 0.001, respectively) calculated using t test in GraphPad

The complete repertoire of cysteine protease encoding genes in tomato, based on which six candidate genes were chosen for expression profiling. Elicitor treatment on pathogen-infected plants showed a negative effect on the expression of CP genes, as deduced from Fig. 6b. The pathogen-alone treatment has induced the expression of these genes up to two (SlCP4) to four-folds (SlCP2.1), and elicitor-only treatment has also shown to upregulate expression of all the genes. However, pathogen-infected plants, when treated with elicitor, the expression was significantly downregulated, and in the case of SlCP01 and SlCP11, the expression levels dropped beyond the levels shown in control.

Expression of three marker genes that were reported to be involved in disease response and resistance mechanisms, namely, SlNP24, SlPR5, and SlPR6, were checked in control, elicitor treated, pathogen treated, and pathogen + elicitor treated conditions (Fig. 7). Interestingly, treating with elicitor in infected pathogen plants significantly upregulated the expression of all three proteins up to at least eight folds. In case of SlNP24, pathogen infection downregulates the expression; however, the transcript abundance in control and elicitor were comparable. Six-fold upregulation of SlNP24 was evidenced in pathogen + elicitor treatment. In case of SlPR5, the levels were relative in control and pathogen-alone treatments, while the gene was considerably downregulated in elicitor treatment. Of note, pathogen + elicitor induced the expression up to five-folds. In SlPR6, pathogen alone treatment induced the expression up to two-fold compared to control; however, elicitor-alone treatment resulted in downregulation of SlPR5. Noteworthy, eight-fold upregulation of SlPR6 was observed in pathogen + elicitor treatment.

Fig. 7.

Relative expression profile of known resistance genes namely SlNP24, SlPR5 and SlPR6 in control, κ-carrageenan treated, S. lycopersici infected, and S. lycopersici + κ-carrageenan conditions. The relative expression ratio of each gene was calculated relative to its expression in control sample. α-Tubulin was used as an internal control to normalize the data. Error bars representing standard deviation were calculated based on three technical replicates for three independent biological replicates. Symbols; *, **, and *** indicate significant differences between control and treated samples (i.e., p < 0.05; p < 0.01 and p < 0.001, respectively) calculated using t test in GraphPad

Conclusions

In the present study, we have tested the efficacy of κ-carrageenan from K. alvarezii in controlling the spread of S. lycopersici that causes leaf spot disease in tomato. Evidently, the elicitor-treated plants showed less symptom upon pathogen infection, and therefore, we were interested in understanding the dynamics exerted on the transcriptome of elicitor treated and untreated plants in the presence and absence of pathogen infection. A systematic study has been conducted to capture the transcriptomes of control (untreated and uninfected), elicitor treatment, pathogen infection alone, and elicitor treatment followed by pathogen infection in tomato plants, and the results of sequencing and analysis of those transcriptomes were discussed here. Comparison of different datasets had pinpointed the upregulated and downregulated genes that belong to classes, including signaling, hormone response, pathogen resistance, etc., and the data has been presented. Further, these genes were mapped onto the tomato genome to construct physical maps useful for downstream analyses. A total of forty-three genes were chosen for qRT-PCR validation, and a strong positive correlation was observed between the expression profiles of qRT-PCR and RNA-Seq data and underlines the reliability of the data presented. Altogether, the study has identified a set of candidate genes that could be manipulated either using marker-assisted or transgene-based approaches for developing leaf spot disease resistance in tomato. Genome editing tools such as CRISPR-Cas9 can be deployed to knock-out the susceptibility determinants for enhancing the resistance to leaf spot disease. Functional characterization of several such genes is underway to delineate their precise roles in disease resistance.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank The Director, CAS in Botany, University of Madras, for providing the laboratory facility. The corresponding author thank Department of Science and Technology, Science and Engineering Research Board (DST-SERB) for financial support.

Author contribution

RN conceived and designed the experiments. SDM, SP, MG performed the experiments. MM, RN analyzed the data. MM, RN wrote the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of this manuscript.

Funding

The funding was provided by Department of Science and Technology, Science and Engineering Research Board, Govt. of India (File No.: ECR/2016/000165).

Data availability

The sequencing data associated with this work have been submitted to the NCBI SRA (Bioproject number is PRJNA622013).

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Arneson PA, Durbin DR. Hydrolysis of tomatine by Septoria lycopersici: a detoxification mechanism. Phytopathology. 1967;57:1358–1360. [Google Scholar]

- Basse CW, Bock K, Boller T. Elicitors and suppressors of the defense response in tomato cells. Purification and characterization of glycopeptide elicitors and glycan suppressors generated by enzymatic cleavage of yeast invertase. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:10258–10265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blancard D. Tomato Diseases. 2. United States: CRC Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Boller T. Chemoperception of microbial signals in plant cells. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1995;46:189–214. [Google Scholar]

- Boughton AJ, Hoover K, Felton GW. Impact of chemical elicitor applications on greenhouse tomato plants and population growth of the green peach aphid, Myzus persicae. Entomol Exp Appl. 2006;120:175–188. [Google Scholar]

- Cao SN, Yuan Y, Qin YH, Zhang MZ, Figueiredo P, Li GH, Qin QM. The pre-rRNA processing factor Nop53 regulates fungal development and pathogenesis via mediating production of reactive oxygen species. Environ Microbiol. 2018;20:1531–1549. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.14082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cárdenas PD, Sonawane PD, Heinig U, Jozwiak A, Panda S, Abebie B, Kazachkova Y, Pliner M, Unger T, Wolf D, Ofner I, Vilaprinyo E, Meir S, Davydov O, Gal-on A, Burdman S, Giri A, Zamir D, Scherf T, Szymanski J, Rogachev I, Aharoni A. Pathways to defense metabolites and evading fruit bitterness in genus Solanum evolved through 2-oxoglutarate-dependent dioxygenases. Nat Commun. 2019;10:1–13. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13211-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty N, Ghosh S, Chandra S, Sengupta S, Acharya K. Abiotic elicitors mediated elicitation of innate immunity in tomato: an ex vivo comparison. Physiol Mol Biol Plants. 2016;22:307–320. doi: 10.1007/s12298-016-0373-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty S, Kumar M. Tomato leaf curl New Delhi virus (Geminiviridae) Ref Module Life Sci. 2020 doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-809633-8.21561-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chandra S, Chakraborty N, Dasgupta A, Sarkar J, Panda K, Acharya K. Chitosan nanoparticles: a positive modulator of innate immune responses in plants. Sci Rep. 2015;5:1–14. doi: 10.1038/srep15195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhary P, Aggarwal PR, Rana S, Nagarathnam R, Muthamilarasan M. Molecular and metabolomic interventions for identifying potential bioactive molecules to mitigate diseases and their impacts on crop plants. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol. 2021;114:101624. [Google Scholar]

- Cui B, Pan Q, Clarke D, Villarreal MO, Umbreen S, Yuan B, Shan W, Jiang J, Loake GJ. S-nitrosylation of the zinc finger protein SRG1 regulates plant immunity. Nat Commun. 2018;9:1–12. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06578-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckardt NA. The plant cell reviews plant immunity: receptor-like kinases, ROS-RLK crosstalk, quantitative resistance, and the growth/defense trade-off. Plant Cell. 2017;29:601–602. doi: 10.1105/tpc.17.00289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang LJ, Qin RL, Liu Z, Liu CR, Gai YP, Ji XL. Expression and functional analysis of a PR-1 Gene, MuPR1, involved in disease resistance response in mulberry (Morus multicaulis) J Plant Interact. 2019;14:376–385. [Google Scholar]

- Fones H, Gurr S. The impact of Septoria tritici blotch disease on wheat: an EU perspective. Fungal Genet Biol. 2015;79:3–7. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2015.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilroy EM, Hein I, Van Der Hoorn R, Boevink PC, Venter E, McLellan H, Kaffarnik F, Hrubikova K, Shaw J, Holeva M, López EC, Borras-Hidalgo O, Pritchard L, Loake GJ, Lacomme C, Birch PRJ. Involvement of cathepsin B in the plant disease resistance hypersensitive response. Plant J. 2007;52:1–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03226.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goupil P, Benouaret R, Charrier O, ter Halle A, Richard C, Eyheraguibel B, Thiery D, Ledoigt G. Grape marc extract acts as elicitor of plant defence responses. Ecotoxicology. 2012;21:1541–1549. doi: 10.1007/s10646-012-0908-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamed SM, Abd El-Rhman AA, Abdel-Raouf N, Ibraheem IBM. Role of marine macroalgae in plant protection and improvement for sustainable agriculture technology. Beni-Suef Univ J Basic Appl Sci. 2018;7:104–110. [Google Scholar]

- Hammond RW. Economic Significance of Viroids in Vegetable and Field Crops. In: Hadidi A, Flores R, Palukaitis P, Randles J, editors. Viroids and Satellites. San Diego: Academic Press; 2017. pp. 5–13. [Google Scholar]

- Hastoy C, Le Bihan Z, Gaudin J, Cosson P, Rolin DS-LV. First report of Septoria sp. infecting Stevia rebaudiana in France and screening of Stevia rebaudiana genotypes for host resistance. Plant Dis. 2019;103:1544–1550. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-10-18-1747-RE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirt H. Aquaporins link ROS signaling to plant immunity. Plant Physiol. 2016;171:1540. doi: 10.1104/pp.16.00433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Z, Cools T, De Veylder L. Mechanisms used by plants to cope with DNA damage. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2016;67:439–462. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-043015-111902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Gu L, Zhang Y, Yan T, Kong G, Kong L, Guo B, Qiu M, Wang Y, Jing M, Xing W, Ye W, Wu Z, Zhang Z, Zheng X, Gijzen M, Wang Y, Dong S. An oomycete plant pathogen reprograms host pre-mRNA splicing to subvert immunity. Nat Commun. 2017;8:2051. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02233-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussein NK, Sabr LJ, Lobo E, Booth J, Ariens E, Detchanamurthy S, Schenk PM. Suppression of Arabidopsis mediator subunit-encoding MED18 confers broad resistance against DNA and RNA viruses while MED25 is required for virus defense. Front Plant Sci. 2020;11:1–12. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.00162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang IS, Hwang BK. The pepper 9-lipoxygenase gene CaLOX1 functions in defense and cell death responses to microbial pathogens. Plant Physiol. 2010;152:948–967. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.147827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapooria RG, Ndunguru J. Rare symptoms and conidial variation in Septoria lycopersici in Zambia. Mycopathologia. 1998;142:101–105. doi: 10.1023/a:1006935829528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kariola T, Brader G, Li J, Palva ET. Chlorophyllase 1, a damage control enzyme, affects the balance between defense pathways in plants. Plant Cell. 2005;17:282–294. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.025817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavroulakis N, Ntougias S, Zervakis GI, Ehaliotis C, Haralampidis K, Papadopoulou KK. Role of ethylene in the protection of tomato plants against soil-borne fungal pathogens conferred by an endophytic Fusarium solani strain. J Exp Bot. 2007;58:3853–3864. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erm230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazan K, Manners JM. Linking development to defense: auxin in plant-pathogen interactions. Trends Plant Sci. 2009;14:373–382. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim MG, Da Cunha L, McFall AJ, Belkhadir Y, DebRoy S, Dangl JL, Mackey D. Two pseudomonas syringae type III effectors inhibit RIN4-regulated basal defense in arabidopsis. Cell. 2005;121:749–759. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Fu F, Xu S, Lee SY, Yun DJ, Mengiste T. Global regulation of plant immunity by histone lysine methyl transferases. Plant Cell. 2016;28:1640–1661. doi: 10.1105/tpc.16.00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li TG, Wang BL, Yin CM, Zhang DD, Wang D, Song J, Zhou L, Kong ZQ, Klosterman SJ, Li JJ, Adamu S, Liu TL, Subbarao KV, Chen JY, Dai XF. The Gossypium hirsutum TIR-NBS-LRR gene GhDSC1 mediates resistance against verticillium wilt. Mol Plant Pathol. 2019;20:857–876. doi: 10.1111/mpp.12797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Fan S, Hu W, Liu G, Wei Y, He C, Shi H. Two Cassava basic leucine zipper (bZIP) transcription factors (MebZIP3 and MebZIP5) confer disease resistance against cassava bacterial Blight. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:2110. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.02110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin NC, Martin GB. Pto- and Prf-mediated recognition of AvrPto and AvrPtoB restricts the ability of diverse Pseudomonas syringae pathovars to infect tomato. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 2007;20:806–815. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-20-7-0806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F, Xu Y, Zhou L, Ali A, Jiang H, Zhu S, Li X. DNA repair gene ZmRAd51A improves rice and arabidopsis resistance to disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:807. doi: 10.3390/ijms20040807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Dong S, Gu F, Liu W, Yang G, Huang M, Xiao W, Liu Y, Guo T, Wang H, Chen Z, Wang J. NBS-LRR protein Pik-H4 interacts with OsBIHD1 to balance rice blast resistance and growth by coordinating ethylene-brassinosteroid pathway. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:1–13. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, Bartnikas LM, Volko SM, Ausubel FM, Tang D. Mutation of the glucosinolate biosynthesis enzyme cytochrome P450 83A1 monooxygenase increases camalexin accumulation and powdery mildew resistance. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:1–13. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lv T, Li X, Fan T, Luo H, Xie C, Zhou Y, Tian CE. The calmodulin-binding protein IQM1 interacts with CATALASE2 to affect pathogen defense. Plant Physiol. 2019;181:1314–1327. doi: 10.1104/pp.19.01060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandal S, Kar I, Mukherjee AK, Acharya P. Elicitor-induced defense responses in Solanum lycopersicum against Ralstonia solanacearum. Sci World J. 2013;2013:561056. doi: 10.1155/2013/561056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mani SD, Nagarathnam R. Sulfated polysaccharide from Kappaphycus alvarezii (Doty) Doty ex P.C. Silva primes defense responses against anthracnose disease of Capsicum annuum Linn. Algal Res. 2018;32:121–130. [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Hernandez AM, Dufresne M, Hugouvieux V, Melton R, Osbourn A. Effects of targeted replacement of the tomatinase gene on the interaction of Septoria lycopersici with tomato plants. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 2000;13:1301–1311. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2000.13.12.1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melton RE, Flegg LM, Brown JK, Oliver RP, Daniels MJ, Osbourn AE. Heterologous expression of Septoria lycopersici tomatinase in Cladosporium fulvum: Effects on compatible and incompatible interactions with tomato seedlings. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1998;11:228–236. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.1998.11.3.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misra RC, Sandeep KM, Kumar S, Ghosh S. A thaumatin-like protein of Ocimum basilicum confers tolerance to fungal pathogen and abiotic stress in transgenic Arabidopsis. Sci Rep. 2016;6:1–14. doi: 10.1038/srep25340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller M, Munné-Bosch S. Ethylene response factors: a key regulatory hub in hormone and stress signaling. Plant Physiol. 2015;169:32–41. doi: 10.1104/pp.15.00677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthamilarasan M, Prasad M. Plant innate immunity: An updated insight into defense mechanism. J Biosci. 2013;38:433–449. doi: 10.1007/s12038-013-9302-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nandety RS, Caplan JL, Cavanaugh K, Perroud B, Wroblewski T, Michelmore RW, Meyers BC. The role of TIR-NBS and TIR-X Proteins in plant basal defense responses. Plant Physiol. 2013;162:1459–1472. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.219162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osbourn A, Bowyer P, Lunness P, Clarke B, Daniels M. Fungal pathogens of oat roots and tomato leaves employ closely related enzymes to detoxify different host plant saponins. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1995;8:971–978. doi: 10.1094/mpmi-8-0971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey S, Muthamilarasan M, Sharma N, Chaudhry V, Dulani P, Shweta S, Jha S, Mathur S, Prasad M. Characterization of DEAD-box family of RNA helicases in tomato provides insights into their roles in biotic and abiotic stresses. Environ Exp Bot. 2019;158:107–116. [Google Scholar]

- Pandey S, Sahu PP, Kulshreshtha R, Prasad M. Role of host transcription factors in modulating defense response during plant-virus interaction. In: Patil BL, editor. Genes, Genetics and Transgenics for Virus Resistance in Plants. U.K.: Caister Academic Press; 2018. pp. 25–54. [Google Scholar]

- Panthee D, Chen F. Genomics of fungal disease resistance in tomato. Curr Genomics. 2010;11:30–39. doi: 10.2174/138920210790217927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S, Gupta R, Krishna R, Kim ST, Lee DY, Hwang DJ, Bae SC, Ahn IP. Proteome analysis of disease resistance against Ralstonia solanacearum in potato cultivar CT206-10. Plant Pathol J. 2016;32:25–32. doi: 10.5423/PPJ.OA.05.2015.0076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker SK, Nutter FW, Gleason ML. Directional spread of Septoria leaf spot in tomato rows. Plant Dis. 1997;81:272–276. doi: 10.1094/PDIS.1997.81.3.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paudel S, Rajotte EG, Felton GW. Benefits and costs of tomato seed treatment with plant defense elicitors for insect resistance. Arthropod Plant Interact. 2014;8:539–545. [Google Scholar]

- Qi J, Wang J, Gong Z, Zhou JM. Apoplastic ROS signaling in plant immunity. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2017;38:92–100. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2017.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu Y, Xi J, Du L, Poovaiah BW. The function of calreticulin in plant immunity: new discoveries for an old protein. Plant Signal Behav. 2012;7:907–910. doi: 10.4161/psb.20721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sangha JS, Ravichandran S, Prithiviraj K, Critchley AT, Prithiviraj B. Sulfated macroalgal polysaccharides λ-carrageenan and ι-carrageenan differentially alter Arabidopsis thaliana resistance to Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol. 2010;75:38–45. [Google Scholar]

- Schreinemachers P, Simmons EB, Wopereis MCS. Tapping the economic and nutritional power of vegetables. Global Food Security. 2018;16:36–45. [Google Scholar]

- Singh VK, Singh AK, Kumar A. Disease management of tomato through PGPB: current trends and future perspective. 3 Biotech. 2017;7:255. doi: 10.1007/s13205-017-0896-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song G, Walley JW. Dynamic protein acetylation in plant-pathogen interactions. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:1–6. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stadnik MJ, de Freitas MB. Algal polysaccharides as source of plant resistance inducers. Trop Plant Pathol. 2014;39:111–118. [Google Scholar]

- Thaler JS, Owen B, Higgins VJ. The role of the jasmonate response in plant susceptibility to diverse pathogens with a range of lifestyles. Plant Physiol. 2004;135:530–538. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.041566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Burg HA, Tsitsigiannis DI, Rowland O, Lo J, Rallapalli G, Maclean D, Takken FL, Jones JD. The F-box protein ACRE189/ACIF1 regulates cell death and defense responses activated during pathogen recognition in tobacco and tomato. Plant Cell. 2008;20:697–719. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.056978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Y, Liu W, Hu W, Liu G, Wu C, Liu W, Zeng H, He C, Shi H. Genome-wide analysis of autophagy-related genes in banana highlights MaATG8s in cell death and autophagy in immune response to Fusarium wilt. Plant Cell Rep. 2017;36:1237–1250. doi: 10.1007/s00299-017-2149-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu HY, Zhang C, Li ZC, Wang ZR, Jiang XX, Shi YF, Tian SN, Braun E, Mei Y, Qiu WL, Li S, Wang B, Xu J, Navarre D, Ren D, Cheng N, Nakata PA, Graham MA, Whitham SA, Liu JZ. The MAPK kinase kinase GMMEKK1 regulates cell death and defense responses. Plant Physiol. 2018;178:907–922. doi: 10.1104/pp.18.00903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Liu F, Zhu S, Li X. The Maize NBS-LRR Gene ZmNBS25 enhances disease resistance in rice and Arabidopsis. Front Plant Sci. 2018;9:1033. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.01033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xun H, Yang X, He H, Wang M, Guo P, Wang Y, Pang J, Dong Y, Feng X, Wang S, Liu B. Over-expression of GmKR3, a TIR–NBS–LRR type R gene, confers resistance to multiple viruses in soybean. Plant Mol Biol. 2019;99:95–111. doi: 10.1007/s11103-018-0804-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J, Chai C, Ai G, Jia Y, Liu W, Zhang X, Bai T, Dou D. A Nicotiana benthamiana AP2/ERF transcription factor confers resistance to Phytophthora parasitica. Phytopathol Res. 2020;2:4. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G, Yan X, Zhang S, Zhu Y, Zhang X, Qiao H, van Nocker S, Li Z, Wang X. The jasmonate-ZIM domain gene VqJAZ4 from the Chinese wild grape Vitis quinquangularis improves resistance to powdery mildew in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2019;143:329–339. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2019.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou B, Zeng L. The tomato U-box type E3 ligase PUB13 acts with group III ubiquitin E2 enzymes to modulate FLS2-mediated immune signaling. Front Plant Sci. 2018;9:1–14. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.00615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The sequencing data associated with this work have been submitted to the NCBI SRA (Bioproject number is PRJNA622013).