Abstract

Background:

Multiple professional organizations and institutes recommend the Bachelor of Science in Nursing (BSN) degree as a minimum standard for registered nurse practice. Achieving this standard may be particularly challenging in rural areas, which tend to be more economically disadvantaged and have fewer opportunities for higher educational attainment compared to urban areas.

Purpose:

Our primary objective was to provide updated information on rural-urban differences in educational attainment. We also examined rural-urban differences in employment type, salary, and demographics among registered nurses in different practice settings.

Methods:

Data were obtained from the 2011–2015 American Community Survey (ACS) Public Use Microdata Sample (PUMS). The sample included registered nurses (RN) between the ages of 18–64 years (n = 34,104) from all 50 states. Chi-square tests, t-tests, and multivariable logistic regression were used to examine the relationship between rurality and BSN preparedness and salary across practice settings.

Results:

Urban nurses were more likely to have a BSN degree than rural nurses (57.9% versus 46.1%, respectively; p < 0.0001), and BSN preparedness varied by state. In adjusted analysis, factors in addition to residence associated with BSN preparation included age, race, and region of the country. Differences in wages were experienced by nurses across practice settings with urban nurses generally earning significantly higher salaries across practice settings (p < 0.0001).

Conclusions:

Strategies to advance nursing workforce education are needed in rural areas and may contribute to improved care quality and health outcomes.

Keywords: Rural health, Nursing workforce, Education, Survey research

Introduction

Currently, registered nurses (RN) can practice in all fifty states with a diploma in nursing, an Associate Degree in Nursing (ADN) or with a Bachelor of Science in Nursing (BSN) (American Association of Colleges of Nursing, 2000). However, the BSN degree has been recommended to be the minimum standard for entry to RN practice (Aiken et al., 2011, 2017, 2014). Some evidence suggests that a more BSN-prepared nursing workforce is associated with higher quality patient care and positive patient outcomes, such as lower mortality rates (Aiken et al., 2014). Similarly, outcomes for cardiac arrest patients improved with an increasing proportion of BSN-educated nurses within the treating hospital (Harrison et al., 2019).

In 2000, the American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN) released recommendations supporting the BSN as the minimum educational requirement for nursing practice based on increasing care complexity and acuity among an increasingly aging population (American Association of Colleges of Nursing, 2000). In 2011, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) released a report calling for expanded practice proficiency in the nursing workforce by advancing the education of ADN-prepared nurses to the baccalaureate level through RN to BSN programs, with a goal of increasing the proportion of nurses with a BSN degree from 50% to 80% by 2020 (Institute of Medicine, 2011). The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) has supported the IOM goal by providing initial funding for selected states to implement the Academic Progression in Nursing Initiative (Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, 2012).

There is geographic variation in the proportion of the nursing workforce who have a BSN, with decreasing proportions of BSN prepared nurses as counties become more rural: urban (46.6%), large rural (35.3%), small rural (30.7%), and isolated rural (30.6%) (Skillman, Palazzo, Keepnews, & Hart, 2006). Regulations requiring that all nurses have BSN degrees may be particularly challenging for nurses with limited financial means, employees of rural hospitals, and those with the farthest travel distance to RN-BSN programs (Gillespie & Langston, 2014; McCafferty, Ball, & Cuddigan, 2017). In addition to geographic barriers, nurses in rural areas have less employer support for personal advancement, as rural health care facilities have fewer resources to support and develop their workforce (Baernholdt & Mark, 2009; Jukkala, Henly, & Lindeke, 2008). Although the availability of online education programs is increasing, residents of many rural areas lack the high-speed internet necessary to access such programs (Federal Communications Commission, 2019). These practice and infrastructure barriers increase the difficulty for rural nurses to obtain higher education levels (Beatty, 2001; Winters & Mayer, 2002).

A well-prepared nursing workforce is needed in rural areas, as rural nurses are likely to care for more patients per shift than their urban counterparts (Baernholdt & Mark, 2009; Baernholdt et al., 2018; Newhouse, Morlock, Pronovost, & Sproat, 2011; Skillman et al., 2006). However, patient to RN ratios increase with increasing rurality, with potential implications for patient outcomes (O’Connor & Wellenius, 2012; Smith, Plover, McChesney, & Lake, 2019). Nurses in rural areas also serve a population that contains a higher proportion of residents who are aged 65 and older and/or have diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and mental health disorders (Smith et al., 2019). Rural areas are often resource-challenged and are located where care coordination and community health competencies would be particularly important for the nursing workforce (Cramer, Duncan, Megel, & Pitkin, 2009).

Prior research examining rural-urban differences in nursing education was either national in scope but dated, or more recent, but used non-generalizable survey methods (Bratt, Baernholdt, & Pruszynski, 2014; Skillman et al., 2006). To assess the need for policies and initiatives to increase education levels in rural areas, updated research on rural-urban differences in nursing education is needed. Updated information on rural-urban disparities in nursing education is particularly important in light of the increase in online nursing programs, which may have improved access to educational opportunities among rural nurses (Kverno & Kozeniewski, 2016). The primary objective of our study was to provide an updated examination of rural-urban differences in educational attainment among registered nurses using a nationally representative data from the US Census 2011–2015 American Community Survey (ACS) Public Use Microdata Sample (PUMS) (Health Resources and Services Administration, 2013). The secondary objective was to examine rural-urban differences in employment types, salaries, and demographics among nurses, as these factors might affect one’s ability to pursue a higher degree.

Methods

Data source and research methods

We conducted a quantitative analysis of cross-sectional data from the 2011–2015 American Community Survey (ACS) Public Use Microdata Sample (PUMS) (United States Census Bureau, n.d.). The ACS is an annual nationally representative survey of 3.5 million people conducted by the United States Census Bureau to examine sociodemographic and housing data, including employment and educational information. ACS is sent to residents of all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico every year, providing updated data relevant for research and policy decisions. The ACS collects self-reported survey data continuously and then aggregates this information over the time period of five years for five-year interval data.

PUMS data include individual-level information on population groups that are not readily accessible through online query systems such as American Fact Finder (United States Census Bureau, 2018). PUMS is a subset of the ACS, and one year of PUMS data is based on information from approximately 1% of the U.S. population. Five-year interval data were used to have sufficient sample sizes for rural areas.

ACS, like all surveys, contains sampling error. PUMS data is a subset of the full ACS sample, so standard errors and margins of error may be wider for PUMS than the full ACS sample (PUMS) (United States Census Bureau, n.d.). We provide standard errors to illustrate the level of uncertainty associated with each point estimate.

Sample

Our sample was defined as ACS respondents reporting their primary occupation as a registered nurse (RN), between the ages of 18–64 years. Of note, this did not include nurse anesthetists or nurse practitioners/nurse midwives, as those were a separate primary occupation category. After excluding those who were missing on metro/nonmetro designation for their location of workplace (n = 82,459), the unweighted total sample consisted of 34,104 nurses from all 50 states (see Appendix 1). The ACS provides the most representative publicly available data on nurses and their education and salary level. Our primary variable of interest, rurality, was defined based on the respondent’s place of work. Place of work for each respondent was designated as either urban or rural in the PUMS dataset by the Public Use Microdata Areas (PUMA), using the metro/nonmetro designation from the US Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service (United States Department of Agriculture, n.d.). PUMAs are formed from aggregated counties to ensure sample sizes large enough to protect respondent confidentiality (around 100,000 residents per PUMA). PUMAs were designated as urban when over 50% of the 2010 Census population lived in metropolitan areas, and rural when over 50% of the 2010 Census population lived in nonmetropolitan areas.

The following variables were examined: educational attainment, salary in the past 12 months, practice setting (hospital, skilled nursing facility (SNF), outpatient care center, home health care, physician’s office, other), usual hours worked per week, and travel time to work in minutes. Respondent education was categorized into associate degree (ADN) or BSN or higher. Demographic characteristics examined included age, sex, race (Caucasian, African American, Asian, Other), marital status (married vs not married), and census region (Midwest, Northeast, South, West).

Analyses

Population-weighted estimates were calculated using survey weights provided by the ACS. Chi-square tests were used to test for rural-urban differences in categorical variables. Independent t-tests were used to compare the means of continuous variables. Differences were tested at an alpha level of 0.05 or more. Logistic regression was used to examine the relationship between rurality and attainment of a BSN or higher degree, adjusting for race, region, and age. All analyses were performed using SAS Version 9.4 and took into account the complex survey design of the ACS. The institutional review board at [name concealed for review] approved this study as exempt.

Results

The sample was predominately female, married, and worked an average of 38 h per week, regardless of urban or rural workplace (Table 1). Nurses in rural settings were slightly older (43.5 years vs42.9, p < 0.001), and more likely to be Caucasian than their urban counterparts (91.9% rural versus 86.0% urban, p < 0.001). Rural nurses reported a shorter average commute time to work (22.9 vs.24.4 min, p < 0.001), while urban nurses reported around $4500 per year more in earnings than rural nurses ($55,807 versus $51,361; p < 0.001). Compared to their urban counterparts, rural nurses were more likely to be married (70.4% versus 66.5%, p < 0.0001) and more likely to reside in the Midwest region of the United States (41.3% versus 27.8%, p < 0.0001).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristic of the nursing workforce, 2011–2015 American Community Survey Public Use Microdata Sample (n = 34,014).

| Rural nurses Unweighted n = 13,369 |

Urban nurses Unweighted n = 20,735 |

Chi-square and t-test p-values |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | SEa | % | SEa | ||

| Education | <0.0001 | ||||

| Associate’s degree | 53.9 | 0.6 | 42.1 | 0.4 | |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 46.1 | 0.6 | 57.9 | 0.4 | |

| Sex | 0.0005 | ||||

| Male | 8.1 | 0.3 | 9.6 | 0.3 | |

| Female | 91.9 | 0.3 | 90.4 | 0.3 | |

| Race | <0.0001 | ||||

| Caucasian | 91.9 | 0.4 | 86.0 | 0.3 | |

| African American | 4.2 | 0.3 | 8.0 | 0.3 | |

| Asian | 1.5 | 0.2 | 3.4 | 0.2 | |

| Other | 2.5 | 0.2 | 2.6 | 0.2 | |

| Marital status | <0.0001 | ||||

| Married | 70.4 | 0.6 | 66.5 | 0.4 | |

| Not married | 29.6 | 0.6 | 33.5 | 0.4 | |

| Census region | <0.0001 | ||||

| Midwest | 41.3 | 0.6 | 27.8 | 0.4 | |

| Northeast | 10.2 | 0.3 | 13.6 | 0.3 | |

| South | 35.6 | 0.6 | 45.3 | 0.4 | |

| West | 12.9 | 0.4 | 13.3 | 0.3 | |

| Rural nurses Unweighted n = 13,369 |

Urban nurses Unweighted n = 20,735 |

Chi-square and t-test p-values | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SEa | Mean | SEa | ||

| Continuous variables | |||||

| Age | 43.5 | 0.1 | 42.9 | 0.1 | <0.0001 |

| Salary in past 12 months | $51,361 | 396 | $55,807 | 282 | <0.0001 |

| Usual hours worked per week | 37.8 | 0.1 | 38.0 | 0.1 | 0.80 |

| Travel time to work (minutes) | 22.9 | 0.2 | 24.4 | 0.1 | <0.0001 |

Standard error.

Most nurses worked in hospitals, SNFs, outpatient care centers, home health care, and physicians’ offices (Table 2). The majority of nurses were employed by hospitals regardless of rural or urban setting, although a greater proportion was employed in urban settings (59.1% in rural and 65.3% in urban). Conversely, a higher percentage of nurses in rural areas worked in SNFs than in urban areas (12.7% versus 8.2%; p < 0.001). A higher proportion of rural nurses with a BSN reported working in SNFs than urban BSN nurses (8.8% versus 5.8%, p < 0.001).

Table 2.

Nursing workforce across workplace settings by education and rurality, 2011–2015 American Community Survey.

| Rural nurses | Urban nurses | P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | SEa | % | SEa | ||

| All nurses | <0.0001 | ||||

| Hospitals | 59.1% | 0.6 | 65.3% | 0.4 | |

| Skilled nursing facilities | 12.7% | 0.4 | 8.2% | 0.3 | |

| Outpatient care centers | 5.4% | 0.3 | 5.2% | 0.2 | |

| Home health care | 5.4% | 0.3 | 4.2% | 0.2 | |

| Physicians’ offices | 3.9% | 0.2 | 4.0% | 0.2 | |

| Other industries | 13.6% | 0.4 | 13.1% | 0.3 | |

| BSN-prepared or higher nurses | <0.0001 | ||||

| Hospitals | 63.0% | 0.9 | 69.1% | 0.6 | |

| Skilled nursing facilities | 8.8% | 0.5 | 5.8% | 0.3 | |

| Outpatient care centers | 5.4% | 0.4 | 4.4% | 0.2 | |

| Home health care | 4.3% | 0.4 | 3.5% | 0.2 | |

| Physicians’ offices | 3.5% | 0.4 | 3.1% | 0.2 | |

| Other industries | 15.1% | 0.6 | 14.1% | 0.4 | |

| ADN nurses | <0.0001 | ||||

| Hospitals | 55.8% | 0.8 | 60.0% | 0.7 | |

| Skilled nursing facilities | 16.0% | 0.6 | 11.5% | 0.5 | |

| Outpatient care centers | 5.4% | 0.4 | 6.3% | 0.3 | |

| Home health care | 6.3% | 0.4 | 5.3% | 0.3 | |

| Physicians’ offices | 4.2% | 0.3 | 5.3% | 0.3 | |

| Other industries | 12.4% | 0.5 | 11.7% | 0.4 | |

Standard error.

Regardless of education, urban nurses had significantly higher salaries than rural nurses across almost all practice settings, except for home health care and physicians’ offices (Table 3). BSN-educated nurses in urban hospitals had the highest average salary at $61,406 per year, and ADN-educated nurses in rural physician offices had the lowest average salary at $37,273 per year. Among BSN-educated nurses only, salaries were significantly different between urban and rural location in only two practice settings: hospitals and outpatient care centers, with urban salaries significantly higher (p < 0.01).

Table 3.

Mean nurse salaries across practice settings, by education and rurality, 2011–2015 American Community Survey.

| Rural nurses | Urban nurses | T-test p-value |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Salary ($) | SEa | Salary ($) | SEa | ||

| All nurses | |||||

| All settings | 51,361 | 396 | 55,807 | 282 | <0.0001 |

| Hospitals | 54,472 | 533 | 58,419 | 355 | <0.0001 |

| Skilled nursing facilities | 45,135 | 1192 | 50,285 | 1097 | <0.0001 |

| Outpatient care centers | 47,575 | 1153 | 53,652 | 996 | <0.0001 |

| Home health care | 47,178 | 1082 | 48,348 | 1075 | 0.34 |

| Physicians’ offices | 43,961 | 1869 | 46,338 | 1311 | 0.19 |

| Other practice setting | 48,884 | 1058 | 52,428 | 726 | 0.0002 |

| BSN-prepared or higher nurses | |||||

| All settings | 56,181 | 726 | 59,255 | 426 | <0.0001 |

| Hospitals | 58,659 | 906 | 61,406 | 516 | 0.0003 |

| Skilled nursing facilities | 50,753 | 3360 | 54,981 | 2298 | 0.10 |

| Outpatient care centers | 51,173 | 1950 | 57,497 | 1162 | 0.0061 |

| Home health care | 46,610 | 2040 | 50,070 | 1746 | 0.10 |

| Physicians’ offices | 53,460 | 4000 | 53,184 | 2466 | 0.94 |

| Other practice setting | 54,143 | 1803 | 54,621 | 996 | 0.75 |

| ADN nurses | |||||

| All settings | 47,232 | 377 | 51,073 | 313 | <0.0001 |

| Hospitals | 50,422 | 561 | 53,691 | 399 | <0.0001 |

| Skilled nursing facilities | 42,483 | 665 | 47,002 | 928 | <0.0001 |

| Outpatient care centers | 45,530 | 1302 | 49, 976 | 1158 | <0.0001 |

| Home health care | 47,515 | 1225 | 46,797 | 1285 | 0.62 |

| Physicians’ offices | 37,273 | 1332 | 40,752 | 1142 | 0.01 |

| Other practice setting | 43,398 | 993 | 48,821 | 994 | <0.0001 |

Standard error.

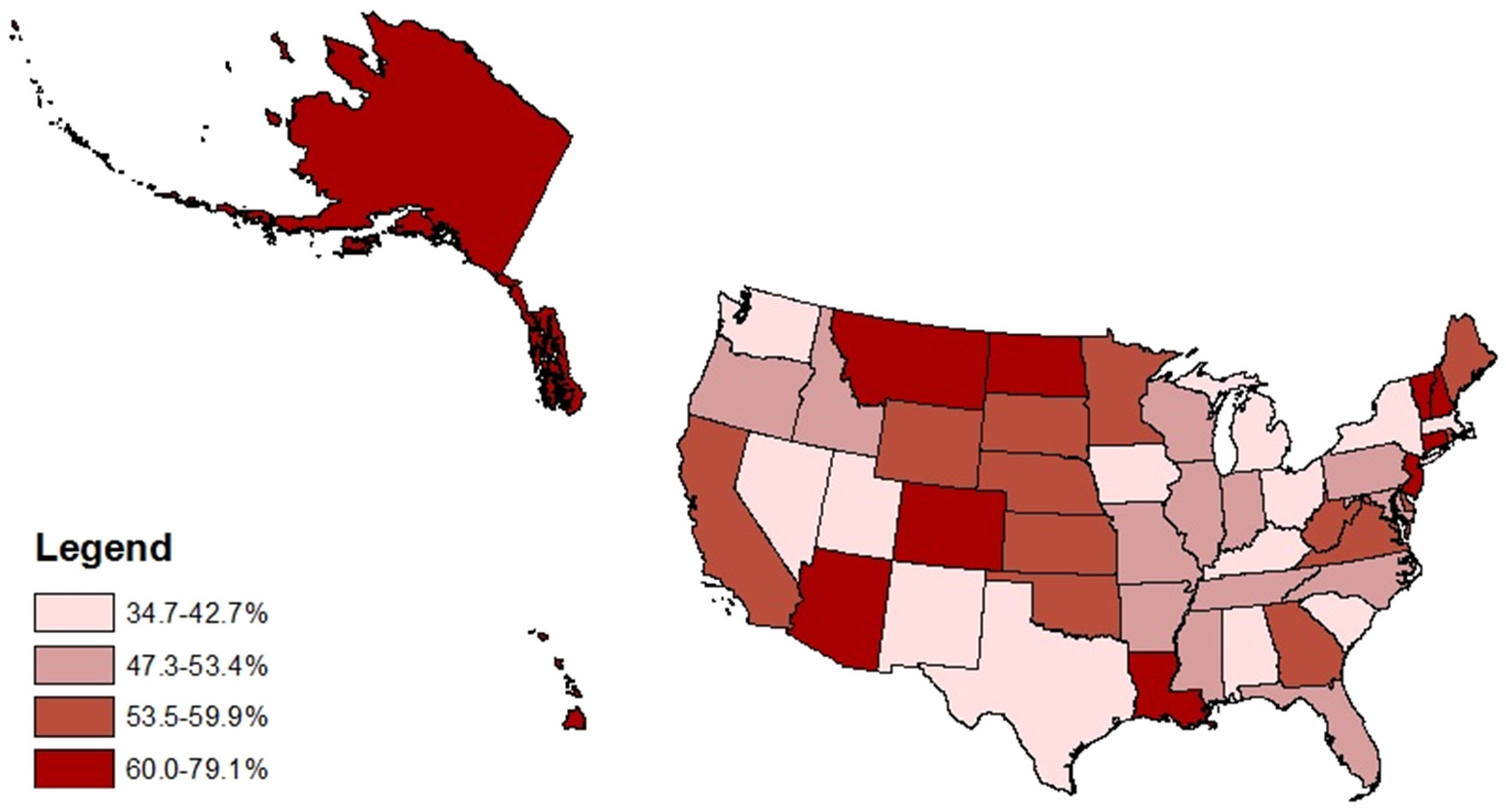

In multivariable analysis predicting the likelihood of a respondent holding a BSN degree, rural nurses were less likely to be BSN prepared when compared to urban nurses even when worksite and personal characteristics are held constant (adjusted OR-aOR- 0.65, 95% CI:0.61–0.69, Table 4). Compared to Caucasian nurses, African American nurses (aOR 1.40; 95% CI 1.23–1.59) and Asian nurses (aOR 4.03; 95% CI 3.17–5.13), were more likely to have a BSN degree. Older nurses were less likely to have a BSN education (aOR 0.95; 95% CI 0.94–0.97 for every 5-year age increase). Regionally, nurses in the Midwest (aOR1.38, 95% CI 1.26–1.51) and the West (aOR 1.31, 95% CI 1.19–1.43) regions were more likely to have a BSN education those in the Northeast. The proportion of registered nurses with a BSN varied by state (Fig. 1) with the highest proportions in the District of Columbia and Hawaii (79.1% and 78.3%, respectively) and the lowest proportions in Nevada (34.7%) and Alabama (39.7%).

Table 4.

Factors related to Bachelor’s of Science in Nursing (BSN) or higher level of nursing education, 2011–2015 American Community Survey.

| Unadjusted odds ratio (95% confidence interval) | Adjusted odds ratio (95% confidence interval) | |

|---|---|---|

| Rurality | ||

| Urban | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Rural | 0.62 (0.59–0.66) | 0.65 (0.61–0.69) |

| Race | ||

| Caucasian | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| African American | 1.25 (1.18–1.32) | 1.40 (1.23–1.59) |

| Asian | 3.71 (3.46–3.97) | 4.03 (3.17–5.13) |

| Other | 1.12 (1.03–1.22) | 1.24 (1.00–1.53) |

| Census region | ||

| Northeast | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Midwest | 1.36 (1.29–1.42) | 1.38 (1.26–1.51) |

| South | 1.00 (0.96–1.04) | 0.96 (0.89–1.02) |

| West | 1.35 (1.29–1.42) | 1.31 (1.19–1.43) |

| Age, 5-year increase | 0.93 (0.93–0.94) | 0.95 (0.94–0.97) |

Fig. 1.

Proportion of registered nurses with a bachelor’s degree or higher, by state, in quartiles 2011–2015 American Community Survey.

Discussion

Our study provides an updated examination of rural-urban differences in educational attainment, workplace settings, salaries, and demographics among nurses, using a nationally representative sample. This study confirms previous findings that urban nurses are more likely to hold a BSN degree than rural nurses (Bratt et al., 2014; Health Resources and Services Administration, 2013; Skillman et al., 2006) and that Black and Asian nurses are more likely to have a BSN than White nurses (Smiley et al., 2018). Our findings also confirm the differentials in wages experienced by nurses across practice settings and geographic locations (Skillman et al., 2006). We found that the mean salary for nurses working in rural settings was lower, compared to urban nurses. Lower salaries may be due to a variety of factors, including lower pay in rural facilities due to lower operating budgets for rural hospitals and rural providers (Kaufman et al., 2016).

The results of this study are particularly important for rural populations. Rural residents are more likely to be older and living with multiple chronic conditions (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2014). Nursing preparedness and resources are associated with reduced medical errors and improved patient outcomes (McGillis Hall & Doran, 2007). Fall rates, for example, are higher in rural than in urban hospitals, possibly due to nursing staff education and preparedness (Baernholdt et al., 2018). BSN educated nurses are better prepared to handle patient care, especially among complex patients requiring higher levels of care coordination, which are more likely to reside in rural areas (Aiken et al., 2011; Harrison et al., 2019). Nurses working in hospitals, SNFs, and home health care are the most likely to benefit from advanced education, as these settings may require nurses to act quickly without the expertise of another health care provider.

Many factors must be addressed to promote increased education in rural areas. Programs that help ADN nurses’ transition to the BSN have been recommended as a way to transition current workers to higher skill levels (McEwen, White, Pullis, & Krawtz, 2012). BSN educated nurses earned more in both urban (+$8182) and rural (+8949) areas. At a basic level, promotional materials noting the salary differential between ADN and BSN nurses may encourage rural nurses working in a hospital or SNF setting to further their education, if it seems that there are openings for BSN nurses in their community (Girard, Hoeksel, Vandermause, & Eddy, 2017). However, if opportunities for BSN employment are more limited in rural areas, the salary differential between ADN and BSN nurses may not be sufficient to encourage rural nurses to pursue higher education.

One of the most highly cited barriers by nurses for RN to BSN programs is the cost of the program, as well as the return and expected value from BSN degree acquisition (Duffy et al., 2014; Spetz & Bates, 2013). Supportive policies are needed to help rural communities promote further education for rural nurses, such as workforce grants, tuition assistance, and tuition reimbursement for educational advancement by the federal government. This may be particularly true in rural areas where healthcare workforce shortages are common (Kaufman et al., 2016; MacDowell, Glasser, Fitts, Nielsen, & Hunsaker, 2010). Struggling rural healthcare facilities, such as rural hospitals, may not be able to provide tuition reimbursement for nurses (Kaufman et al., 2016). Healthcare organizations can also help promote a BSN workforce by providing higher pay for BSN-prepared nurses and opportunities for career advancement (Institute of Medicine, 2011). In a survey of chief nurse executives in Kentucky hospitals, Warshawsky and colleagues found that 97% of hospitals offered at least one workforce incentive and 70% offered two or more with the most common incentives being tuition reimbursement, advancement opportunities, and time off (Duffy et al., 2014; Warshawsky, Brandford, Barnum, & Westneat, 2015).

Policies and initiatives to incentivize and subsidize rural nursing education are needed given that RN to BSN programs are costly. The typical student in an RN to BSN program is often older and with more personal obligations than a traditional student (Duffy et al., 2014; Spetz & Bates, 2013). RN to BSN programs also often have attrition rates of up to 40% (Jones-Schenk, 2017). For example, to address health care provider shortages in rural areas, the Health Resource and Service Administration Bureau of Health Workforce funds loan repayment programs such as the Nurse Corps Loan Repayment Program (Health Resource and Services Administration, 2019). This program assists with student loan repayment for RNs, advanced practice nurses, and nurse faculty who agree to practice for at least two years at a critical shortage facility in a health professional shortage area, which includes many rural areas. This program could be expanded to support RNs, already practicing in high-need, rural areas, to obtain a BSN and subsequently address the shortage of BSN-prepared nurses in rural areas. Healthcare employers may also consider providing full-time benefits for nurses who need to work part-time to complete their BSN given that this is a reported issue among registered nurses.

A few RN-to-BSN degree programs have been implemented in rural communities in addition to the expansion of online education programs (Anderson, Wells, Mather, & Burman, 2017; Hawkins, Wiles, Karlowicz, & Tufts, 2018). The expansion of online education programs may partially explain why we found that 46% of rural nurses had a BSN or higher compared to 40.7% as reported in 2013 by the Health Resources and Services Administration (Health Resources and Services Administration, 2013). However, the availability of online programs does not directly translate into improved access for residents of rural areas. A lack of reliable high-speed internet required for accessing online education programs continues to be a barrier for residents of rural areas and Tribal lands. The Federal Communication Commissions’ 2019 Broadband Development Report stated that > 26% of rural residents and 32% of populations on Tribal lands lack coverage meeting the industry standard for high-speed internet in comparison to 1.7% of urban residents (Federal Communications Commission, 2019).

Limitations and strengths

Our study is a descriptive study using a secondary data set, and thus experiences multiple limitations. First, the inability to use counties or census tracts to define metropolitan/nonmetropolitan status, since PUMS smallest geography is PUMAs, limits the degree to which our findings can be compared to other studies. Also, there is a lag between survey administration and availability of PUMS data for research purposes; however, the 2011–2015 data used here are more recent than prior studies (Health Resources and Services Administration, 2013). Next, while the ACS is representative of the nation as a whole, it may not be representative of occupational subpopulations, such as nurses. Additionally, data were missing on rural-urban status of practice location for many survey participants, which may affect the representativeness of the study findings. Finally, the ACS occupational questions are only asked of those aged 18–65, so older nurses who are still working were not included.

A strength of the present study is that it used a nationally representative survey to provide a recent and comprehensive assessment of educational attainment among rural and urban nurses. In addition, investigators explored multiple variables potentially associated with educational attainment, which provided nuanced insights into education advancement access and equity that may inform policy changes.

Implications for nursing education

Leaders in nursing education are well-positioned to develop and implement innovative strategies to promote higher education for rural nurses. Many major universities have satellite campuses located in rural communities, which may be important settings for new nursing programs that appeal to ADN-prepared nurses who want a pursue their BSN locally. Also, universities within states could form partnerships such that students at a university without a nursing program could enroll in another university’s nursing program that is provided, at least in part, on their home campus. As an example, Wichita State University and Kansas State University have partnered to develop a satellite BSN program to help address the nursing shortage in Kansas (Wichita State University). This program would allow Kansas State University students to enroll in the university’s College of Health and Human Sciences for three years and then become Wichita State University nursing students for two years while attending classes on the Kansas State University campus. Similar types of models could be developed where large urban educational institutions offering BSN programs partner with rural institutions that only offer ADN programs.

Ideas for future research

Although evidence indicates that a more BSN-prepared workforce contributes to improved patient outcomes, it is unknown whether there are rural-urban differences in the effects of nursing education levels on patient outcomes (Aiken et al., 2011, 2017, 2014). Given that the prevalence of many chronic diseases is greater among adults living in rural areas, additional research is needed to determine the effects of nurse education levels on patient outcomes specifically in rural areas of the United States. Additionally, longitudinal research may help eluci-date the effect of increasing BSN attainment on both the rural and urban nursing workforce.

Conclusions

Rural areas have a lower proportion of BSN-educated nurses. Strategic system supports will be necessary to increase the education required of ADN-prepared nurses currently practicing in rural areas. Higher education attainment and expanded practice capabilities should be prioritized over fear of job loss, with financial and time incentives provided by health care systems when possible. This research may inform future strategies to advance the nursing workforce education, resulting in potential improvements in the care quality and health outcomes provided in rural healthcare locations.

Funding

This study was supported by the Federal Office of Rural Health Policy (FORHP), Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) under cooperative agreement #U1CRH30539. Dr. Demetrius Abshire was supported (in part) by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities of the National Institutes of Health under award number K23MD013899. The information, conclusions, and opinions expressed in this brief are those of the authors and no endorsement by FORHP, HRSA, HHS, or NIH is intended or should be inferred.

Appendix 1. Raw and weighted number of respondents by state

| State | Observations | Weighted observations |

|---|---|---|

| Alabama | 649 | 10,332 |

| Alaska | 76 | 1679 |

| Arizona | 1609 | 32,099 |

| Arkansas | 714 | 14,849 |

| California | 557 | 10,437 |

| Colorado | 205 | 4289 |

| Connecticut | 1256 | 23,799 |

| Delaware | 123 | 2165 |

| District of Columbia | 214 | 4338 |

| Florida | 631 | 12,366 |

| Georgia | 1656 | 30,597 |

| Hawaii | 122 | 2788 |

| Idaho | 122 | 2283 |

| Illinois | 1636 | 23,704 |

| Indiana | 1318 | 24,453 |

| Iowa | 1029 | 18,101 |

| Kansas | 552 | 9646 |

| Kentucky | 886 | 18,326 |

| Louisiana | 1159 | 24,636 |

| Maine | 305 | 5635 |

| Maryland | 318 | 5680 |

| Massachusetts | 67 | 956 |

| Michigan | 1347 | 19,295 |

| Minnesota | 1358 | 17,660 |

| Mississippi | 757 | 15,374 |

| Missouri | 996 | 18,113 |

| Montana | 207 | 4503 |

| Nebraska | 404 | 6035 |

| Nevada | 46 | 770 |

| New Hampshire | 182 | 2652 |

| New Jersey | 389 | 7562 |

| New Mexico | 178 | 3403 |

| New York | 905 | 12,072 |

| North Carolina | 1111 | 21,547 |

| North Dakota | 308 | 7106 |

| Ohio | 1273 | 22,144 |

| Oklahoma | 223 | 4670 |

| Oregon | 327 | 6026 |

| Pennsylvania | 1246 | 15,985 |

| Rhode Island | 165 | 3138 |

| South Carolina | 537 | 10,661 |

| South Dakota | 236 | 4004 |

| Tennessee | 939 | 17,285 |

| Texas | 1662 | 28,196 |

| Utah | 172 | 2674 |

| Vermont | 209 | 3492 |

| Virginia | 1046 | 20,387 |

| Washington | 354 | 6038 |

| West Virginia | 645 | 13,271 |

| Wisconsin | 1528 | 25,905 |

| Wyoming | 150 | 2922 |

| Total | 34,104 | 606,048 |

References

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (2014). Chartbook on rural health care.(Rockville, MD: ). [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LH, Cimiotti JP, Sloane DM, Smith HL, Flynn L, & Neff DF (2011). Effects of nurse staffing and nurse education on patient deaths in hospitals with different nurse work environments. Medical Care, 49(12), 1047–1053. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182330b6e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LH, Sloane D, Griffiths P, Rafferty AM, Bruyneel L, McHugh M, … Van Achterberg T (2017). Nursing skill mix in European hospitals: Cross-sectional study of the association with mortality, patient ratings, and quality of care. BMJ Quality and Safety, 26(7), 559–568. 10.1136/bmjqs-2016-005567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LH, Sloane DM, Bruyneel L, Van Den Heede K, Griffiths P, Busse R, & Sermeus W (2014). Nurse staffing and education and hospital mortality in nine European countries: A retrospective observational study. The Lancet, 383(9931), 1824–1830. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62631-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Association of Colleges of Nursing (2000). The baccalaureate degree in nursing as minimal preparation for professional practice. Retrieved July 23, 2019, from https://www.aacnnursing.org/News-Information/Position-Statements-White-Papers/Bacc-Degree-Prep. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Anderson J, Wells K, Mather C, & Burman ME (2017). ReNEW: Wyoming’s answer to academic progression in nursing. Nursing Education Perspectives, 38(5), E18–E22. 10.1097/01.nep.0000000000000207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baernholdt M, Hinton ID, Yan G, Xin W, Cramer E, & Dunton N (2018). Fall rates in urban and rural nursing units. Journal of Nursing Care Quality, 33(4), 326–333. 10.1097/ncq.0000000000000319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baernholdt M, & Mark BA (2009). The nurse work environment, job satisfaction and turnover rates in rural and urban nursing units. Journal of Nursing Management, 17(8), 994–1001. 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2009.01027.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beatty RM (2001). Continuing professional education, organizational support, and professional competence: Dilemmas of rural nurses. Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing, 32(5), 203–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bratt MM, Baernholdt M, & Pruszynski J (2014). Are rural and urban newly licensed nurses different? A longitudinal study of a nurse residency programme. Journal of Nursing Management, 22(6), 779–791. 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2012.01483.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramer M, Duncan K, Megel M, & Pitkin S (2009). Partnering with rural communities to meet the demand for a qualified nursing workforce. Nursing Outlook, 57(3), 148–157. 10.1016/j.outlook.2008.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy MT, Friesen MA, Speroni KG, Swengros D, Shanks LA, Waiter PA, & Sheridan MJ (2014). BSN completion barriers, challenges, incentives, and strategies. Journal of Nursing Administration. 10.1097/NNA.0000000000000054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Federal Communications Commission (2019). 2019 Broadband Deployment Report. Retrieved May 15, 2020 from website https://docs.fcc.gov/public/attachments/FCC-19-44A1.pdf.

- Gillespie AB, & Langston N (2014). Inspiration for aspirations: Virginia nurse insights about BSN progression. Journal of Professional Nursing, 44(4), 232–236. 10.1016/j.profnurs.2014.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girard SA, Hoeksel R, Vandermause R, & Eddy L (2017). Experiences of RNs who voluntarily withdraw from their RN-to-BSN program. Journal of Nursing Education. 10.3928/01484834-20170421-02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison JM, Aiken LH, Sloane DM, Brooks Carthon JM, Merchant RM, Berg RA, & McHugh MD (2019). In hospitals with more nurses who have baccalaureate degrees, better outcomes for patients after cardiac arrest. Health Affairs, 38(7), 1087–1094. 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins JE, Wiles LL, Karlowicz K, & Tufts KA (2018). Educational model to increase the number and diversity of RN to BSN graduates from a resource-limited rural community. Nurse Educator, 43(4), 206–209. 10.1097/NNE.0000000000000460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health Resources and Services Administration (2013). The U.S. nursing workforce: Trends in supply and education. Retrieved March 2, 2020 https://bhw.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/bhw/nchwa/projections/nursingworkforcetrendsoct2013.pdf.

- Health Resources and Services Administration (2019). Nurse corps loan repayment program. Retrieved July 23, 2019, from website https://bhw.hrsa.gov/loansscholarships/nursecorps/lrp.

- Institute of Medicine (2011). The future of nursing: Leading change, advancing health.(Washington, DC: ). [Google Scholar]

- Jones-Schenk J (2017). Co-creating a movement. Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing, 48(10), 442–444. 10.3928/00220124-20170918-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jukkala AM, Henly SJ, & Lindeke LL (2008). Rural perceptions of continuing professional education. Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing, 39(12), 555–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman BG, Thomas SR, Randolph RK, Perry JR, Thompson KW, Holmes GM, & Pink GH (2016). The rising rate of rural hospital closures. The Journal of Rural Health, 32(1), 35–43. 10.1111/jrh.12128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kverno K, & Kozeniewski K (2016). Expanding rural access to mental health care through online postgraduate nurse practitioner education. Journal of the American Association of Nurse Practitioners, 28(12), 646–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDowell M, Glasser M, Fitts M, Nielsen K, & Hunsaker M (2010). A national view of rural health workforce issues in the USA. Rural and Remote Health, 10(3), 1531. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCafferty KL, Ball SJ, & Cuddigan J (2017). Understanding the continuing education needs of rural midwestern nurses. The Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing, 48(6), 265–269. 10.3928/00220124-20170517-07. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen M, White MJ, Pullis BR, & Krawtz S (2012). National survey of RN-to-BSN programs. The Journal of Nursing Education, 51(7), 373–380. 10.3928/01484834-20120509-02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGillis Hall L, & Doran D (2007). Nurses’ perceptions of hospital work environments. Journal of Nursing Management, 15(3), 264–273. 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2007.00676.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newhouse RP, Morlock L, Pronovost P, & Sproat SB (2011). Rural hospital nursing: Results of a national survey of nurse executives. The Journal of Nursing Administration, 41(3), 129–137. 10.1097/NNA.0b013e31820c7212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor A, & Wellenius G (2012). Rural-urban disparities in the prevalence of diabetes and coronary heart disease. Public Health, 126(10), 813–820. 10.1016/j.puhe.2012.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (2012). Robert Wood Johnson Foundation launches initiative to support academic progression in nursing. Retrieved from https://www.rwjf.org/en/library/articles-and-news/2012/03/robert-wood-johnson-foundation-launches-initiative-to-support-ac.html.

- Skillman SM, Palazzo L, Keepnews D, & Hart LG (2006). Characteristics of registered nurses in rural versus urban areas: Implications for strategies to alleviate nursing shortages in the United States. The Journal of Rural Health, 22(2), 151–157. 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2006.00024.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smiley RA, Lauer P, Bienemy C, Berg JG, Shireman E, Reneau KA, & Alexander M (2018). The 2017 national nursing workforce survey. Journal of Nursing Regulation, 9(3), S1–S88. [Google Scholar]

- Smith JG, Plover CM, McChesney MC, & Lake ET (2019). Isolated, small, and large hospitals have fewer nursing resources than urban hospitals: Implications for rural health policy. Public Health Nursing, 36(4), 469–477. 10.1111/phn.12612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spetz J, & Bates T (2013). Is a baccalaureate in nursing worth it? The return to education, 2000–2008. Health Services Research. 10.1111/1475-6773.12104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Census Bureau (2018). Understanding and using American community survey data: What all data users need to know. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2018/acs/acs_general_handbook_2018.pdf.

- United States Census Bureau. (n.d.). PUMS technical documentation. Retrieved July 23,2019, from https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/technical-documentation/pums/documentation.2015.html.

- United States Department of Agriculture. (n.d.). Data for rural analysis. Retrieved from https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/rural-economy-population/rural-classifications/data-for-rural-analysis/.

- Warshawsky NE, Brandford A, Barnum N, & Westneat S (2015). Achieving 80% BSN by 2020: Lessons learned from Kentucky’s registered nurses. Journal of Nursing Administration. 10.1097/NNA.0000000000000231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wichita State University WSU, K-State start plan for WSU satellite nursing program on K-State campus. Retrieved from https://www.wichita.edu/about/wsunews/news/2019/09-sept/bsn_satellite_program_3.php, Accessed date: 11 March 2020.

- Winters CA, & Mayer DM (2002). Special feature: An approach to cardiac care in rural settings. Critical Care Nursing Quarterly, 24(4), 75–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]