Abstract

Objective

This study aimed to describe informant discrepancies between mother and father reports of child vulnerability in youth with spina bifida (SB) and examine variables that were associated with these discrepancies.

Methods

Ninety-two parent dyads, with a child with SB (ages 8–15 years), were recruited as a part of a longitudinal study. Mothers and fathers completed questionnaires assessing parental perception of child vulnerability (PPCV), as well as medical and demographic information, behavioral aspects of the couple relationship, parenting stress, mental health of the parent, and child behavioral adjustment. The degree to which there was a parenting alliance was assessed with observational data. Mother–father discrepancies were calculated at the item level.

Results

Findings revealed that greater father mental health symptoms, parenting stress, and child behavior problems were associated with “father high and mother low” discrepancies in PPCV. There were also lower scores on observed parenting alliance when there were higher rates of “father high and mother low” discrepancies in PPCV.

Conclusions

For families of youth with SB, discrepancies in PPCV where fathers perceive high vulnerability and mothers perceive low vulnerability may be a “red flag” for the presence of other parental and child adjustment difficulties. Findings are discussed in terms of the Attribution Bias Context Model and underscore the importance of including fathers in research on families who have children with chronic health conditions.

Keywords: chronic illness, family functioning, parents, spina bifida

Introduction

Use of multiple informants is considered a key component of best practices in evidence-based assessment (Hunsley & Mash, 2007). However, this data collection strategy often reveals informant discrepancies or inconsistencies among informants’ reports of a behavior (De Los Reyes et al., 2013). Whereas some have treated discrepancies as simple “measurement error,” this practice could be viewed as contradictory to the original purpose of obtaining multiple informant perspectives, namely, to consider variations across reports of a particular behavior. Informant discrepancies are especially common in the assessment of youth (De Los Reyes et al., 2013); these discrepancies appear to be meaningful, as they may provide information about the informants, the relationship between the informants and between the informants and the target child, the constructs being studied, and the family system (De Los Reyes, 2011). Discrepancies in parent reports may be especially important in understanding outcomes in pediatric illness populations, as mothers and fathers often take on different medical caregiving roles (Wysocki & Gavin, 2006), which may differentially influence their perspective on their child.

Parental perception of child vulnerability (PPCV) is the parental belief that a child is more susceptible to illness, injury, or harm as compared with other children (Green & Solnit, 1964). PPCV is particularly salient in pediatric populations, since youth with chronic medical conditions are more likely to be perceived as vulnerable by parents than are their typically developing peers (Houtzager et al., 2015). In pediatric populations, higher levels of PPCV may be considered appropriate or adaptive, given that children with medical conditions often are more at risk for harm (or “vulnerable”) than typically developing youth and require increased parental vigilance and protection to stay healthy (e.g., monitoring symptoms, administering medications). However, research has also found that parents can perceive their child’s condition as more severe than is medically indicated, and that parental beliefs about their child’s condition are better predictors of developmental outcomes than the actual degree of condition severity (DeMaso et al., 1991). Further, PPCV has been associated with potentially maladaptive parent behaviors and poorer child functioning in pediatric populations (Anthony et al., 2011). For example, parents of children with asthma who perceived their child as more vulnerable were also more likely to restrict their children’s activities, keep their children home from school, and take their child to the doctor for acute care (Spurrier et al., 2000). Similarly, among families of children with chronic pain, increased PPCV was associated with poorer child functioning and more child pain-related health-care utilization (Connelly et al., 2012).

PPCV may be particularly relevant for families of youth with spina bifida (SB). SB results from a neural tube defect that produces an incomplete closure of the spinal cord during fetal development (Copp et al., 2015). This chronic condition occurs in 2 of every 10,000 live births in the United States (Copp et al., 2015). SB involves a range of difficulties, including deficits in motor, orthopedic, sensory, cognitive, self-care, and social functioning (Zukerman et al., 2011). Parents of youth with SB confront challenges related to managing their child’s medical regimen, stress about their child’s health status, and uncertainty regarding their child’s independence (Mullins et al., 2007). Youth with SB tend to have limited decision-making autonomy, social immaturity, few interactions outside of school, and dependence on adults for guidance (Holmbeck et al., 2002, 2003). Additionally, many of these youth have challenges with attention and executive functioning (Copp et al., 2015; Stern et al., 2018), making consistency and repetition within their environment especially important to support mastery of new skills. Discrepancies in PPCV between caregivers likely lead to inconsistent parenting beliefs and practices, and potentially inconsistent support for skill acquisition and the successful transfer of medical responsibilities. Further, compared with typically developing youth, these youth are especially reliant on their caregivers and, therefore, may be more attuned to parental conflict resulting from discrepant beliefs. Increasing our understanding of these discrepancies, therefore, may inform the development of clinical interventions for families of youth with SB.

To our knowledge, discrepancies between parent reports of PPCV have yet to be examined in any pediatric population. However, studies of discrepant parent reports of other child constructs have found associations between discrepancies and parental depressive symptoms, child behavior problems, family functioning, marital functioning, and demographic factors (Harvey et al., 2013). These factors may influence discrepancies in PPCV and may be especially salient for families of youth with SB. For example, parents of youth with SB report more psychosocial stress than parents of typically developing children (Holmbeck et al., 1997). Additionally, mothers and fathers of youth with SB have been found to take on different caregiving roles within the family (Brekke et al., 2017), which may lead to discrepancies in PPCV. These different roles may also lead to differences in how mothers and fathers adjust to and cope with parenting a child with chronic medical condition, and adjustment has been found to be differentially related to PPCV for mothers and fathers in these families (Driscoll et al., 2018).

The Attribution Bias Context (ABC) Model explains why informant discrepancies may occur within a family context (De Los Reyes & Kazdin, 2005). This framework posits that three central characteristics lead to informant discrepancies: (a) differences in attributions (i.e., observer informants are more likely to make dispositional attributions, whereas self-informants are more likely to attribute their behavior to context), (b) biases or decision thresholds guiding the judgment of specific behaviors, and (c) contexts within which informants observe behaviors (e.g., home vs. school). Among various informant pairings (child–parent, teacher–parent, etc.), mother–father discrepancies are often lowest, given that parents typically observe their child in similar contexts, and are both likely to attribute child behavior to disposition (De Los Reyes & Kazdin, 2005). However, De Los Reyes and Kazdin (2005) suggest various empirically supported factors that may influence parent attribution style, including parent mental health, parenting stress, and the mother–father relationship.

Mother–father discrepancies may reflect meaningful information about parent mental health or the mother–father relationship. Poor parent mental health may influence parent perspectives insofar as it is more likely to be associated with the recall of negative information about child problems. In other informant pairings, positive relationships have been found between maternal levels of depression and discrepancies between mothers’ ratings and teachers’ ratings of the child (De Los Reyes & Kazdin, 2005) and between parental anxiety and informant discrepancies (Engel et al., 1994). Parenting stress may also decrease the threshold by which parents gauge whether a child’s behavior is problematic, leading one parent to view the child more negatively relative to the other parent (De Los Reyes & Kazdin, 2005). Discrepancies may also indicate less adaptive relational functioning between mothers and fathers. De Los Reyes and Kazdin (2006) note that differing perceptions on the same construct (e.g., child functioning) impact how informants (e.g., parents) interact with each other and function over time. More generally, little attention has been given to the relationship between family characteristics and informant discrepancies (De Los Reyes & Kazdin, 2005), but further examination may provide a window into the relationship between discrepancies and the marital relationship.

The first aim of this study is to describe agreement and discrepancies in PPCV within families of youth with SB. The second aim is to evaluate factors that may potentially be associated with discrepancies in PPCV. Specifically, using the ABC Model (De Los Reyes & Kazdin, 2005) and key literature on informant discrepancies regarding child behavior, we evaluated the following potential correlates of mother–father discrepancies in PPCV: (a) demographic/medical variables (child age, sex, IQ, lesion level, type of SB, and presence of shunt), (b) parent factors (mental health symptoms of the parent and parenting stress), (c) relationship factors (parent dyadic adjustment and parenting alliance), and (d) child behavioral adjustment. We did not have any predictions for demographic variables, but expected that indicators of SB severity (i.e., low IQ, high lesion level, presence of shunt, and more severe type of SB, specifically myelomeningocele) would be positively associated with agreement on PPCV. In other words, given that parents are more likely to agree that a child is highly vulnerable in contexts of high illness severity, we hypothesized that discrepancies would be more likely to emerge when illness severity is lower. In cases of lower illness severity, factors in the ABC Model (e.g. parental mental health, parent stress) would be expected to contribute to discrepancies. In terms of parent factors, we expected that greater parent mental health symptoms and parenting stress would be positively associated with more discrepancies, based on their potential to negatively influence parent perspectives. Specifically, we expected these effects to be parent specific; for example, greater mental health symptoms and parenting stress among mothers were expected to be related to discrepancies where mothers rated PPCV high and fathers rated PPCV low. Based on findings regarding relationship quality and informant discrepancies within other dyads in the family (De Los Reyes & Kazdin, 2006), we anticipated that better dyadic adjustment and a stronger parenting alliance would be negatively associated with mother–father discrepancies in PPCV. Finally, we anticipated that discrepancies in PPCV would be associated with more child behavior problems, given the inconsistent parenting and messaging that likely accompany such discrepancies.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Participants were recruited from a larger longitudinal study examining psychosocial and neuropsychological functioning among youth with SB (Driscoll et al., 2018; Holbein et al., 2015). Data from the first time point of this longitudinal study were included. Data collection occurred over a 3-year period for this time point. Participants were recruited from four hospitals and a statewide SB association in the Midwest, both in person during regularly scheduled clinic visits and through recruitment letters. Participants could respond to letter by mail via a response form. If this form was not returned, research assistants followed up with participants via phone. Interested participants were screened to determine whether they met the inclusion criteria: (a) a diagnosis of SB (including types myelomeningocele, lipmeningocele, and myelocystocele); (b) age 8–15 years old; (c) proficiency in English or Spanish; (d) involvement of at least one primary caregiver; and (e) residence within 300 miles of the laboratory to allow for home visits during which data were collected.

Through recruitment procedures, 246 families were approached, and 163 families agreed to participate. Nonenrolled families were either not reachable or declined to participate due to lack of interest or time. Of these 163 families, 21 families could not be contacted or later declined to participate and two families did not meet inclusionary criteria. Thus, the final full sample included 140 families. This study included only the 92 families who had two parents report on perceptions of child vulnerability. Parents were defined as biological parents, adoptive parents, step-parents, or romantic partners of a parent. Grandparents were excluded.

Sample descriptive information is presented in Table I. A slight majority of children were female (N = 47, 51.1%). Most children were White (N = 62, 67.4%), but there was a significant number of participants who were Hispanic/Latino/a (N = 21, 22.8%). Mean child age was ∼11 years old (SD = 2.45; range: 8–15). Of the 92 families included in the analyses, most dyads were comprised of a mother and father. Most mothers (N = 82; 89.1%) and fathers (N = 86; 93.5%) were married to their child’s biological parent or adoptive parent. Most parents were White (N = 65 mothers, 70.7% and N = 65 fathers, 70.7%). There was a substantial minority of Hispanic/Latino/a parents (N = 20 mothers, 21.7% and N = 22 fathers, 23.9%).

Table I.

Descriptive Demographic and Medical Information for Sample (N = 92)

| Child characteristics | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | N | % | |||

| Child age, M, SD | 11.3 | (2.45) | |||

| Child IQ, M, SD | 88.8 | 19.6 | |||

| Hollingshead SES, M, SD | 41.2 | 15.4 | |||

| Child sex | |||||

| Female | 47 | 51.1 | |||

| Male | 45 | 48.9 | |||

| Child type of SB | |||||

| Myelomeningocele | 82 | 89.1 | |||

| Other | 10 | 10.9 | |||

| Child lesion level | |||||

| Sacral | 25 | 27.2 | |||

| Lumbar | 46 | 50.0 | |||

| Thoracic | 18 | 19.6 | |||

| Not sure or missing | 3 | 3.3 | |||

| Shunt present | |||||

| Yes | 71 | 77.2 | |||

| No | 21 | 22.8 | |||

| Child race | |||||

| White | 62 | 67.4 | |||

| African American | 5 | 5.4 | |||

| Hispanic/Latino/a | 21 | 22.8 | |||

| Bi-racial | 4 | 4.4 | |||

| Parent characteristics | |||||

| Variables | Mothers |

Fathers | |||

| N | % | N | % | ||

| Age, M, SD | 39.76 | 5.80 | 42.49 | 6.84 | |

| Years in marriage, M, SD | 15.73 | 6.75 | 16.07 | 6.37 | |

| Marital status | |||||

| Married to child’s parent | 82 | 89.1 | 85 | 92.4 | |

| Separated from child’s father | 1 | 1.1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Divorced from child’s biological parent | 8 | 8.7 | 3 | 3.3 | |

| Never married and living with s/o | 1 | 1.1 | 4 | 4.4 | |

| Parent race | |||||

| White | 65 | 70.7 | 65 | 70.7 | |

| African American | 5 | 5.4 | 5 | 5.4 | |

| Hispanic/Latino/a | 20 | 21.7 | 22 | 23.9 | |

| Asian | 1 | 1.1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Missing | 1 | 1.1 | 0 | 0 | |

Note. M = mean; SD = standard deviation; SB = spina bifida; s/o = significant other.

Procedure

This study was approved by university and hospital institutional review boards. Trained research assistants collected data from families during home visits. For families who primarily spoke Spanish, at least one research assistant was bilingual. Before data collection began, informed consent from parents and assent from all children were obtained. During data collection, family members completed questionnaires independently, and data were collected from both parents for all families included in this study. Questionnaires were offered in both Spanish and English. Questionnaires that were only available in English were translated into Spanish by a team of research assistants who were native speakers of Spanish, using forward and back translation procedures. Research assistants read questionnaires aloud to participants when requested or when reading difficulties were observed or reported. Family interactions across four structured tasks were videotaped and coded. The structured tasks included: (a) an interactive game, (b) discussion of two age-appropriate socially relevant vignettes, (c) discussion of transferring condition-specific medical responsibilities to the child, and (d) discussion of conflict issues as rated previously in self-report questionnaires. The order of tasks was randomly assigned, and each task lasted ∼10 min. Families received $150 compensation and small gifts (e.g., t-shirts, pens, water bottles) for participation at this timepoint.

Measures

Demographic and Medical Information

Both parents completed a questionnaire reporting on family and youth demographic information, including age, sex, race/ethnicity, income, education, and employment, as well as medical data. The Hollingshead Four Factor Index of SES was computing by using parent’s education and occupation (Hollingshead, 1975) with higher scores indicating higher SES.

Parent Perceived Child Vulnerability

The Vulnerable Child Scale-Parent Report (VCS-P) reflects specific concerns about a child’s health (e.g., “In general, my child seems less healthy than other children of the same age”). Forsyth’s original 16-item Child Vulnerability Scale (Forsyth, 1987) was modified to exclude the item “I sometimes worry that my child will die” to be sensitive to the fears of parents of children with a chronic illness. Participants responded to each item using a 4-point scale (1 = definitely false to 4 = definitely true). Higher scores reflect higher perceptions of vulnerability. In the present sample, this scale demonstrated adequate internal consistency reliability (Mother α = .78; Father α = .84).

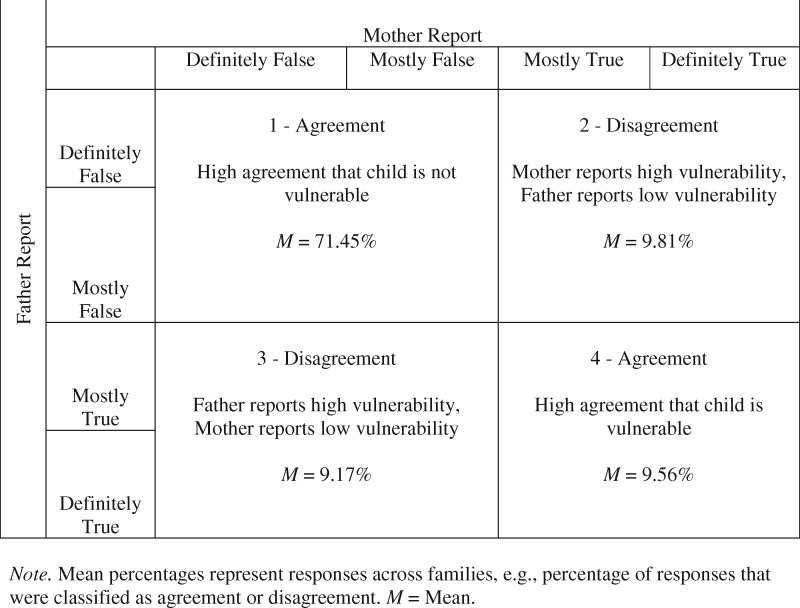

Discrepancies were calculated using procedures described by Psihogious and Holmbeck (2013). Mother and father responses were compared at the item level and responses from each dyad for each item were placed in one of four quadrants (Figure 1). Responses were collapsed so that if parents were within one point of each other within the same valence (e.g., both “definitely false” and “mostly false”), these were considered agreement. For example, if both parents rated a perceived vulnerability as definitely false or mostly false, they received a “1” (vs. a 0) for this item in quadrant 1. After mother and father responses on each of the 15 items were analyzed in this way, the number of items that fell into each of the four quadrants was summed for each family. Then, the proportion of responses in each quadrant was calculated to control for the number of items answered (given the possibility of missing responses) by dividing the total number of items that fell in each quadrant by the total number of joint responses across all quadrants. This yielded a continuous proportion score for each family in each of the four quadrants.

Figure 1.

Agreement and discrepancies in PPCV (N = 92). Note. Mean percentages represent responses across families, for example, percentage of responses that were classified as agreement or disagreement. M = Mean.

Couple Relationship Quality and Functioning

The Consensus scale of the Dyadic Adjustment Scale (Spanier, 1976) measured partner agreement (e.g., on “handling family finances,” “making major decisions”). One item on this scale, pertaining to couple sexual behavior, was excluded due to university IRB preference. Parents responded to the remaining 13 items on a 6-point Likert response scale (0 = always agree to 5 = always disagree). Higher scores represent greater consensus within relationships. This scale demonstrated excellent internal consistency in the present sample (Mother α = .91; Father α = .91).

Parenting Stress

Three subscales from the Parenting Stress Index (PSI; Abidin, 1995) were used to measure stress in the parenting role: Perceived Parental Competence (11 items; e.g., “I have had more problems raising my children than expected”; reverse scored), Restriction of Role (7 items; e.g., “I feel trapped by my responsibilities as a parent”), and Social Isolation (6 items; e.g., “Since having children, I have a lot fewer chances to see my friends…”). Higher scores reflect less perceived competence, more role restriction, and greater social isolation. Internal consistency ranged from fair to good (Mother Perceived Competence α = .71, Mother Role Restriction α = .83, Mother Social Isolation α = .80; Father Perceived Competence α = .66, Father Role Restriction α = .71, and Father Social Isolation α = .75).

Parent Mental Health

Parent self-reported mental health was assessed with the Symptom Checklist – Revised (Derogatis et al., 1976). This questionnaire consists of 90 items rated on a 5-point rating scale (0 = not at all distressed to 4 = extremely distressed) for symptoms experienced over the past week. The Global Severity Index was used to represent average severity across all items. Internal consistency was excellent for both parents (Mother α = .96; Father α = 0.95).

Observed Parenting Alliance

Observed parenting behavior was coded using the Family Interaction Macro Coding System developed by Holmbeck et al., 2007, which was adapted from a methodology developed by Smetana et al. (1991; see Holmbeck et al., 2002 for a detailed description). Coders were trained by discussing individual item codes and reviewing previously coded family interactions with an expert coder. Research assistants achieved 90% agreement with the expert coder’s ratings on previously coded videos. Coders then independently viewed family interaction tasks on videotape and provided 5-point Likert scale ratings on dimensions of parenting behaviors. Coding was done separately for each of four tasks.

In this study, the item “presenting as a united front” was used as a proxy for parenting alliance and represented the degree to which parents supported each other’s thoughts and ideas. Ratings ranged from “not at all” (mother and father cannot agree on any issue, they do not support each other) to “always” (mother and father agree on issues discussed and support each other in their position). Higher scores indicated higher observed levels of presenting as a united front. For each task, behaviors were rated by two coders; item level means of the raters for each task were averaged across tasks to produce a single score for each dimension for each parent. “Presenting as a united front” demonstrated moderate interrater reliability (Intraclass Correlation Coefficient [ICC] = .59).

Child Behavior Problems

The Child Behavior Checklist, parent form (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001), is comprised of 118 problem items. Respondents rate each item on a 3-point scale (0 = not true, 1 = somewhat or sometimes true, 2 = very true or often true). Higher scores represent more child behavior problems. This study used raw scores for Internalizing Problems, Externalizing Problems, and Total Problems.

Overview of Statistical Analyses

Preliminary Analyses

Independent-samples Mann–Whitney U tests were conducted to compare distributions of key demographic variables between the included families with two participating parents (N = 92) and the remaining families without two participating parents (N = 48). Additionally, Pearson’s correlations and t-tests were used to compare any differences between mother reports and father reports on all predictive variables. Cohen’s d was used to calculate effect sizes for these differences. Effect sizes were interpreted in accordance with Cohen’s (1988) guidelines for effect size interpretation: small effect (d = 0.20), medium effect (d = 0.50), and large effect (d = 0.80).

Aim 1: Describe Agreement and Discrepancies in PPCV

To generally describe mother and father reports on PPCV, we conducted Pearson’s correlations and t-tests between mothers’ mean scores on the VCS-P and fathers’ mean scores on the VCS-P. Subsequently, to examine discrepancies in PPCV, the proportion of responses in which (a) mother rated PPCV high and father rated PPCV low (quadrant two in Figure 1), referred to as “mother-high PPCV,” and (b) father rated PPCV high and mother rated PPCV low (quadrant three in Figure 1), referred to as “father-high PPCV,” were examined. Data from the remaining two categories (one and four) were not analyzed, as these categories represented agreement.

Aim 2: Evaluate Factors Associated with Discrepancies in PPCV

Discrepancies are represented by the variables “mother-high PPCV” and “father-high PPCV.” The calculation of these variables and their exact meaning is described above. t-Tests were used to evaluate differences across demographic and medical categorical variables, including type of SB, lesion level, presence of shunt, and child sex for rates of mother-high PPCV and father-high PPCV. When appropriate (i.e., when there were large differences in the sample sizes of categorical groups such as with type of SB), Mann-Whitney U tests were used to compare distributions of discrepancy proportions across the categorical variables. Pearson’s r correlation analyses were conducted to examine cross-sectional associations between mother-reported continuous variables, as well as child age and IQ, and the proportion of mother-high PPCV items. Similar analyses were conducted for the proportion of father-high PPCV items.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Among the original sample of 140 families, 48 families did not have two participating parents who completed the PPCV measure, and therefore were not included in the present analyses. When compared with the 92 families included in the analyses in this article, nonincluded families scored lower on Hollingshead SES (U = 1,457.5, p = .04), had children with lower IQs (U = 1,422.0, p < .01), and had a greater portion of non-White children [χ2 (1) = 22.75, p < .001]. Nonincluded mothers (i.e., when there was only a mother respondent and no father respondent) were significantly older (U = 1,101.5, p = .01). Nonincluded mothers also scored significantly higher on PPCV (U = 892.0, p = .01). For the eight nonincluded fathers (i.e., when there was only a father respondent and no mother respondent), length of marriage was significantly greater than that reported by included fathers, (U = 125.0, p < .01).

Additional preliminary analyses (Table II) revealed a small, significant difference between mother- and father- reported social isolation (subscale of PSI), such that fathers reported greater social isolation than mothers, on average. There were no other significant differences between mothers and fathers for this sample of parents on the predictor variables, and all effect sizes were small (Cohen, 1988). On the other hand, all correlations between mother and father reports on the predictor variables were significant.

Table II.

Descriptive Information for Measures

| Mothers |

Fathers |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | M | SD | M | SD | Correlation, r | Statistical difference | Cohen’s d |

| Parent perceived child vulnerability | 27.26 | 7.02 | 27.62 | 7.28 | .48*** | t (91) = −0.46 | 0.05 |

| Couple relationship quality and functioning | 63.52 | 8.26 | 63.73 | 7.81 | .60*** | t (88) = −0.27 | 0.03 |

| Parenting stress: perceived competence | 42.54 | 4.97 | 42.98 | 5.14 | .31** | t (91) = −0.71 | 0.09 |

| Parenting stress: role restriction | 18.23 | 4.86 | 17.38 | 3.73 | .23* | t (89) = 1.50 | 0.20 |

| Parenting stress: social isolation | 13.24 | 3.74 | 14.16 | 3.50 | .44*** | t (89) = −2.29* | 0.25 |

| Child behavior problems: internalizing | 8.78 | 6.59 | 7.82 | 6.68 | .51*** | t (91) = 1.40 | 0.14 |

| Child behavior problems: externalizing | 5.92 | 5.83 | 5.65 | 5.56 | .54*** | t (91) = 0.47 | 0.05 |

| Child behavior problems: total problems | 30.44 | 19.96 | 28.75 | 20.35 | .52*** | t (91) = 0.82 | 0.08 |

| Parent mental health | 26.37 | 26.18 | 23.64 | 22.03 | .22* | t (90) = 0.86 | 0.11 |

Note. M = mean; SD = standard deviation. Parenting Alliance was measured by the observational measure of “Presenting as a United Front.” Since it is an observational measure yielding one score per dyad, it is not included in this table, as there are no separate scores for mothers and fathers.

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

Aim 1: Describe Agreement and Discrepancies in PPCV

t-Tests revealed that mother and father total scores on PPCV were not significantly different, [t(91)= -0.46, p = .64]. To identify discrepancies in PPCV, descriptive statistics were used to evaluate the average proportion of responses in each of the four quadrants of responses (Figure 1), with quadrant 1 (high agreement that child is not vulnerable) having the highest proportion (71.45%). Another 9.56% of responses fell in quadrant 4, representing high agreement that a child is vulnerable. Additionally, 9.81% of dyads’ responses fell into the category of mother-high PPCV (quadrant 2), and 9.17% of dyads’ responses fell into the father-high PPCV category (quadrant 3). Thus, most families exhibited high rates of agreement between mothers and fathers on PPCV.

Aim 2: Evaluate Factors Associated with Discrepancies in PPCV

Pearson’s r correlations between all continuous variables and mother- and father-high PPCV were computed. There were no significant cross-sectional correlations between any of the measures and mother-high PPCV. There were also no significant relations between mother-high PPCV and child sex, type of SB, lesion level, or presence of a shunt.

Table III shows positive correlations between father-high PPCV and father parenting stress (both social isolation [r = .22, p = .04] and role restriction [ r = .25, p = .02]), father mental health (r = .23, p = .03), child internalizing problems (r = .28, p = .01), and child total problems (r = .26, p = .01). Father-high PPCV was also negatively correlated with observed parenting alliance (r = −.28, p = .01). There were no significant associations between father-high PPCV and child sex, type of SB, lesion level, or presence of a shunt.

Table III.

Correlations Between Father-high PPCV and Continuous Demographic and Father-Report Measures

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Father-high PPCV | 1 | |||||||||||

| 2. Child age | .03 | 1 | ||||||||||

| 3. Child IQ | −.02 | −.23* | 1 | |||||||||

| 4. Couple relationship quality | −.09 | .15 | −.08 | 1 | ||||||||

| 5. Parenting stress: PC | −.00 | −.13 | .19 | .42** | 1 | |||||||

| 6. Parenting stress: SI | .22* | −.00 | −.04 | −.31** | −.42** | 1 | ||||||

| 7. Parenting stress: RR | .25* | .06 | −.22* | −.38** | −.38** | .59** | 1 | |||||

| 8. Child beh. problems: intern. | .28** | .08 | −.07 | −.23* | −.33** | .11 | .08 | 1 | ||||

| 9. Child beh. problems: extern. | .12 | .03 | −.03 | −.02 | −.20 | .02 | .07 | .64* | 1 | |||

| 10. Child beh. problems: total | .26* | −.01 | −.10 | −.19 | −.30** | .13 | .13 | .86** | .85** | 1 | ||

| 11. Parent mental health | .23* | −.06 | −.02 | −.44** | −.32** | .29** | .24* | .29** | .04 | .28* | 1 | |

| 12. Observed parenting alliancea | −.28** | −.05 | .21 | .02 | −.00 | −.05 | −.02 | −.26* | −.19 | −.20 | .06 | 1 |

Note. PC = perceived competence; SI = social isolation; RR = role restriction; beh. = behavior; intern. = internalizing problems; extern. = externalizing problems.

Parenting Alliance was measured by the observational measure of “Presenting as a United Front.” It is the only nonself-report measure in this correlation table.

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

Discussion

This study aimed to examine discrepancies in PPCV between mothers and fathers of children with SB, as well as evaluate variables that were associated with these discrepancies. This research contributes to the current literature by investigating variables associated with informant discrepancies, using a fine-grained methodology for calculating mother–father discrepancies at the item level (Devine et al., 2012; Psihogious & Holmbeck, 2013), and placing these variables in a theoretical framework (De Los Reyes & Kazdin, 2005). This is the second investigation to replicate Devine et al.’s (2012) methodology for calculating discrepancies at the item level (Psihogious & Holmbeck, 2013).

Discrepancies in PPCV is likely to be a highly salient construct for families of youth with SB. Parenting a child with this chronic condition involves myriad challenges related to managing a child’s medical regimen, concern about child health, and uncertainty regarding child independence (Mullins et al., 2007). Given that parents of children with pediatric illnesses often take on different medical caregiving roles (Wysocki & Gavin, 2006), they may have differing perspectives on their child. Discrepancies in PPCV between parents may communicate mixed messages about appropriate levels of child autonomy, responsibility, and skill mastery. Such inconsistent parenting beliefs and practices may also be associated with greater child behavior problems, and more difficulties in the family as whole. Although discrepancies in PPCV had not been examined in any pediatric population, discrepant parent reports on other child constructs have been associated with a host of familial and child adjustment factors (Harvey et al., 2013). Indeed, our findings revealed that parent discrepancies were associated with greater child behavior problems.

The ABC Model (De Los Reyes & Kazdin, 2005) emphasizes the following as important mechanisms that dictate the emergence of informant discrepancies: (a) differences in attributions, (b) biases or decision thresholds, and (c) contexts within which informants observe behavior. As we anticipated, the majority of parents in this sample reported perceptions of low child vulnerability, and most parents (∼71%) were aligned in this perception. This finding is consistent with De Los Reyes and Kazdin’s (2005) reasoning that mother–father discrepancies should be relatively low, given their shared context for observing the child and their tendency to make dispositional attributions. However, a minority of parent response patterns (∼19%) represented discrepancy in perceived child’s vulnerability. In this study, analyses were conducted to determine if variables that may influence informant perceptions and biases (e.g., parent mental health symptoms and parent stress) and variables related to the relationship between the informants (e.g., parenting alliance) were associated with the rate of these discrepancies. In addition, we examined whether parent discrepancies in PPCV were associated with child behavioral functioning. There were no significant associations between any of these variables and mother-high PPCV. However, consistent with hypotheses, father mental health symptoms, parenting stress (social isolation and role restriction), lower levels of observed parenting alliance, and child internalizing and total problems were associated with higher rates of father-high PPCV.

Placing these findings within the context of the ABC Model, it may be that fathers who experience distress may be more likely to attend to behavior signaling their child’s vulnerability. More specifically, paternal mental health symptoms and parenting stress may be associated with a bias for recalling negative child behaviors and, in turn, a greater likelihood of perceiving a child as vulnerable. Although similar patterns have been observed in past work between mental health, parenting stress, and maternal biases in reporting (e.g., Chi & Hinshaw, 2002), the impact on father informants is understudied. These findings also suggest that lower levels of parenting alliance were associated with “father high” discrepancies. In the context of De Los Reyes and Kazdin’s (2005) theoretical framework, it may be that discrepant views on the child’s level of vulnerability may negatively impact how parents interact with each other over time. More generally, research on the association between family characteristics and informant discrepancies is limited, but findings such as these warrant further consideration in future work. Moreover, the temporal order of these effects should also be explored in future longitudinal studies of informant discrepancies.

Findings regarding associations with PPCV discrepancies differed for mothers and fathers. Specifically, variables that are likely to influence parent perspectives and biases (i.e., parent mental health, parenting stress, and parenting alliance) were associated with father-high discrepancies, but not mother-high discrepancies. Notably, rates of mother- and father-high discrepancies were very similar (9.81% mother- and 9.17% father-high), but none of the examined variables were associated with mother-high discrepancies. It may be that differential findings regarding mothers and fathers are in part driven by ways in which caring for a child with SB impacts mothers and fathers differently. For example, mothers are more likely than fathers to have long-term absence from employment when caring for a child with SB (Brekke et al., 2017). With this apparent tendency to take on relatively more caregiving responsibility and the accompanying greater exposure to condition-related situations, mothers may be best situated to perceive true child vulnerability. Thus, mother-high discrepancies may reflect greater familiarity with and insight into child vulnerability, rather than a characteristic of mothers or the family system that is biasing mothers’ perspectives. Interestingly, none of the demographic and medical variables were associated with discrepancies, highlighting that discrepancies are more likely to be connected to parent- and relationship-specific factors, than to illness-related factors.

These findings also highlight the importance of including fathers in pediatric psychology research. Despite a longstanding history of neglecting the role of fathers in research with children, fathers have been found to influence their children across nearly every outcome studied, including physical health, which is of particular relevance for pediatric populations (Phares et al., 2005). This study further underscores that we need to pay attention to fathers in studies of children with chronic health conditions. Instances where fathers reported high PPCV relative to mothers showed significant associations with variables that reflect familial risk factors (i.e., parent mental health, parenting stress, poor parenting alliance, and child behavior problems). Thus, father-high PPCV may be a part of the larger constellation of factors that should trigger concern and further assessment by clinicians who work with these families. The significant relationship between father-high PPCV and child behavior problems highlights the adverse impact of these discrepancies on the child.

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

This study had several strengths, including the multi-method assessment strategy, inclusion of both parents, and a fine-grained methodology for calculating discrepancies. However, there were several limitations. First, most parents generally agreed about perceived child vulnerability, with <20% of response pairs representing discrepancies. In a sample with higher rates of discrepancies, it is possible that different patterns of association would have emerged. Second, as is common in studies of pediatric populations, the sample size was relatively small. We were limited in using data from two-parent families, requiring us to exclude 48 families. These excluded families differed from the families included in the present analyses in ways that may have affected reports of child vulnerability, such as lower SES, lower child IQ, higher proportion of minority race, older mothers, and higher mother PPCV. We should continue to strive for participation of both parents within two-parent families whenever possible. Third, future research should also explore parent discrepancies in nontraditional (e.g., LGBT) homes, allowing for greater inclusion of different family contexts. Fourth, future research should explore the longitudinal relationship between discrepancies in PPCV and these constructs. Fifth, this study also relied on parent-report measures for all constructs, except observed parenting alliance (the moderate interrater reliability of observed parenting alliance is also a limitation). Analyses were also seemingly limited by the presence of common method variance due to using the same informant in regression analyses for both the independent and dependent variables (e.g., father-reported parenting stress when predicting father-high PPCV). However, given the focus on discrepant perspectives, it is important to understand that those fathers who perceived more parenting stress were also more likely to also perceive their child as vulnerable, even when their spouse did not. Finally, while we assumed that mothers and fathers included in this study observe their child in similar contexts, we were unable to assess possible differences across contexts between mothers and fathers. As suggested by the ABC Model (De Los Reyes & Kazdin, 2005), such differences may influence discrepancies and are, therefore, important to consider in future research.

Conclusions and Clinical Implications

This study takes an important step towards treating informant discrepancies in a pediatric sample not simply as “measurement error,” but as reflective of possible meaningful differences in families (De Los Reyes et al., 2013). Using a sophisticated method for calculating discrepancy at the item-level, this study evaluated discrepancies in PPCV among mothers and fathers of a child with SB. Findings highlight that when fathers feel more parenting stress, experience more mental health symptoms, report more child behavior problems, or when the parenting dyad exhibits lower parenting alliance, they are more likely to perceive their child as vulnerable, even when the child’s mother does not. These findings have implications for the assessment of and intervention with families with a child with SB.

In assessment of families with SB, practitioners should, whenever possible, aim to obtain multiple informants’ perspectives. Further, they should consider that informant discrepancies, especially in the case of father-high ratings, might be indicators of meaningful experiences for the informants (e.g., parenting experiences). This research suggests that discrepancies in perceived child vulnerability are not merely a proxy for general informant disagreement but may be a “red flag” for the presence of other specific parental stressors or child behavior problems.

In terms of clinical interventions for families with SB, it is important that practitioners understand that parents of youth with SB may experience higher levels of PPCV than the general population, given the challenges that these families face (Mullins et al., 2007; Driscoll et al., 2018). Although heightened PPCV in the context of SB is understandable and may serve an adaptive function in protecting the child, it can often be more elevated than is medically indicated (DeMaso et al., 1991) and may be associated with problems in parent behaviors and child functioning (Anthony et al., 2011). Furthermore, discrepancies in PPCV may lead to differential treatment by parents or even miscommunication between or mixed signals from parents.

Given our field’s history of neglecting fathers in pediatric assessment, treatment, and research, it can be easy to dismiss father-high discrepancies as “measurement error” or to defer to mother informants as the most valid source. However, by including fathers in the assessment process and paying attention to discrepancies that emerge, we may have an opportunity to identify familial risk factors associated with these discrepancies. Fortunately, most of these risk factors are modifiable. Specifically, parenting stress, parent mental health, and parenting alliance are targetable and show evidence of improvement when treated with psychosocial interventions. By targeting these factors, we may be able to mitigate their impact on children and bolster resilience within the family system.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Illinois Spina Bifida Association, as well as staff of the Spina Bifida Clinics at Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago, Shriners Hospital for Children-Chicago, and Loyola University Medical Center. They also thank the numerous undergraduate and graduate research assistants who helped with data collection and data entry. Finally, they would like to thank the parents, children, and health professionals who participated in this study.[aq

Funding

This research was supported in part by grants from the National Institute of Nursing Research and the Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research (R01 NR016235), National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01 HD048629), and the March of Dimes Birth Defects Foundation (12-FY13-271). This report is part of an ongoing, longitudinal study.

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

References

- Abidin R. R. (1995). Parenting Stress Index (3rd edn) Psychological Assessment Resources. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach T. M., Rescorla L. A. (2001). Manual for the ASEBA school-age forms & profiles: An integrated system of multi-informant assessment. ASEBA. [Google Scholar]

- Anthony K., Bromberg M., Gil K., Schanberg L. (2011). Parental perceptions of child vulnerability and parent stress as predictors of pain and adjustment in children chronic arthritis. Children’s Health Care, 40(1), 53–69. 10.1080/02739615.2011.537938 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brekke I., Fruh E. A., Kvarme L. G., Holmstrom H. (2017). Long-time sickness absence among parents of pre-school children with cerebral palsy, spina bifida and Down syndrome: A longitudinal study. BMC Pediatrics, 17(1), 1–7. 10.1186/s12887-016-0774-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi T. C., Hinshaw S. P. (2002). Mother–child relationships of children with ADHD: The role of maternal depressive symptoms and depression-related distortions. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 30(4), 387–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd edn). Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Connelly M., Anthony K. K., Schanberg L. E. (2012). Parent perceptions of child vulnerability are associated with functioning ad health care use in children with chronic pain. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 43(5), 953–960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copp A. J., Scott Adzick N., Chitty L. S., Fletcher J. M., Holmbeck G. N., Shaw G. M. (2015). Spina bifida. Nature Reviews Disease Primers, 1(1), 1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Los Reyes A., & , Kazdin A. E. (2005). Informant discrepancies in the assessment of childhood psychopathology: a critical review, theoretical framework, and recommendations for further study. Psychological Bulletin, 131(4), 483–509. 10.1037/0033-2909.131.4.483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Los Reyes A., & , Kazdin A. E. (2006). Informant discrepancies in assessing child dysfunction relate to dysfunction within mother-child interactions. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 15(5), 643–661. 10.1007/s10826-006-9031-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Los Reyes A. (2011). Introduction the special section: More than measurement error: Discovering meaning behind informant discrepancies in clinical assessments of children and adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 40(1), 1–9. 10.1080/15374416.2011.533405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Los Reyes A., Thomas S. A., Goodman K. L., Kundey S. M. A. (2013). Principles underlying the use of multiple informants’ reports. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 9(1), 123–149. 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeMaso D. R., Campis L. K., Wypij D., Bertram S., Lipshitz M., Freed M. (1991). The impact of maternal perceptions and medical severity on the adjustment of children with congenital heart disease. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 16(2), 137–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis L. R., Rickels K., Rock A. F. (1976). The SCL-90 and the MMPI: A step in the validation of a new self-report scale. British Journal of Psychiatry, 128(3), 280–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devine K. A., Holbein C. E., Psihogios A. M., Amaro C. M., Holmbeck G. N. (2012). Individual adjustment, parental functioning, and perceived social support in Hispanic and non-Hispanic white mothers and fathers of children with spina bifida. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 37(7), 769–778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driscoll C. F. B., Stern A., Ohanian D., Fernandes N., Crowe A. N., Ahmed S. S., Holmbeck G. N. (2018). Parental perceptions of child vulnerability in families of youth with spina bifida: The role of parental distress and parenting stress. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 43(5), 513–524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel N. A., , Rodrigue J. R., & , Geffken G. R. (1994). Parent-child agreement on ratings of anxiety in children. Psychological Reports, 75(3), 1251–1260. 10.2466/pr0.1994.75.3.1251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsyth B. W. C. (1987). Mothers perceptions of their children’s vulnerability after hospitalization for infection. American Journal of Diseases of Children, 141, 377. [Google Scholar]

- Green M., Solnit A. J. (1964). Reactions to the threatened loss of a child: A vulnerable child syndrome. Pediatric Management of the Dying Child, Part III. Pediatrics, 34, 58–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey E. A., Fischer C., Weieneth J. L., Hurwitz S. D., Sayer A. G. (2013). Predictors of discrepancies between informants’ ratings of preschool-aged children’s behavior: An examination of ethnicity, child characteristics, and family functioning. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 28(4), 668–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holbein C. E., Lennon J. M., Kolbuck V. D., Zebracki K., Roache C. R., Holmbeck G. N. (2015). Observed differences in social behaviors exhibited in peer interactions between youth with spina bifida and their peers: Neuropsychological correlates. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 40(3), 320–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead A. B. (1975). Four factor index of social status. Yale University Department of Psychology. [Google Scholar]

- Holmbeck G. N., , Westhoven V. C., , Phillips W. S., , Bowers R., , Gruse C., , Nikolopoulos T., , Totura C. M. W., & , Davison K. (2003). A multimethod, multi-informant, and multidimensional perspective on psychosocial adjustment in preadolescents with spina bifida. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71(4), 782–796. 10.1037/0022-006X.71.4.782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmbeck G. N., Coakley R. M., Hommeyer J. S., Shapera W. E., Westhoven V. C. (2002). Observed and perceived dyadic and systemic functioning in families of preadolescents with spina bifida. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 27(2), 177–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmbeck G. N., Gorey-Ferguson L., Hudson T., Seefeldt T., Shapera W., Turner T., Uhler J. (1997). Maternal, paternal, and marital functioning in families of preadolescents with spina bifida. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 22(2), 167–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmbeck G. N., Zebracki K., Johnson S. Z., Belvedere M., Schneider J. (2007). Parent-child interaction macro-coding manual. Loyola University Chicago. [Google Scholar]

- Houtzager B. A., Moller E. L., Maurice-Stam H., Last B. F., Grootenhuis M. A. (2015). Parental perceptions of child vulnerability in a community-based sample: Association with chronic illness and health-related quality of life. Journal of Child Health Care, 19(4), 454–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunsley J., Mash E. J. (2007). Evidence-based assessment. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 3(1), 29–51. 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullins L. L., Wolfe-Christensen C., Pai A. L. H., Carpentier M. Y., Gillaspy S., Cheek J., Page M. (2007). The relationship of parental overprotection, perceived child vulnerability, and parenting stress to uncertainty in youth with chronic illness. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 32(8), 973–982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phares V., Lopez E., Fields S., Kamboukos D., Duhig A. M. (2005). Are fathers involved in pediatric psychology research and treatment? Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 30(8), 631–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Psihogious A. M., Holmbeck G. N. (2013). Discrepancies in mother and child perceptions of spina bifida medical responsibilities during the transition to adolescence: Associations with family conflict and medical adherence. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 38(8), 859–870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smetana J. G., Yau J., Restrepo A., Braeges J. L. (1991). Adolescent-parent conflict in married and divorced families. Developmental Psychology, 27(6), 1000–1010. [Google Scholar]

- Spanier G. B. (1976). Measuring dyadic adjustment: New scales for assessing the quality of marriage and similar dyads. Journal of Marriage and Family Counseling, 38(1), 15–28. 10.2307/350547 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spurrier N. J., Sawyer M. G., Staugas R., Martin A. J., Kennedy D., Streiner D. L. (2000). Association between parental perception of children’s vulnerability to illness and management of children’s asthma. Pediatric Pulmonology, 29(2), 88–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern A., , Driscoll C. F. B., , Ohanian D., & , Holmbeck G. N. (2018). A longitudinal study of depressive symptoms, neuropsychological functioning, and medical responsibility in youth with spina bifida: Examining direct and mediating pathways. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 43(8), 895–905. 10.1093/jpepsy/jsy007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wysocki T., Gavin L. (2006). Paternal involvement in the management of pediatric chronic diseases: Associations with adherence, quality of life, and health status. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 31(5), 501–511. 10.1093/jpepsy/jsj042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zukerman J. M., Devine K. A., Holmbeck G. N. (2011). Adolescent predictors of emerging adulthood milestones in youth with spina bifida. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 36(3), 265–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]