Summary

The use of anti-tumor necrosis factor agents such as infliximab as treatment modalities of inflammatory joint diseases has widely spread over the past few years. However, increasing numbers of reports of infectious complications during TNF-a blockade have also highlighted the fact that an increased rate of sometimes life-threatening complications may be the price paid for superior therapeutic efficacy. We report the first case report of Listeria endocarditis associated with infliximab use and the second published case of Listeria infection associated with infliximab in patients with psoriatic arthritis. We also summarize the literature regarding the association of Listeria infection with use of infliximab. Further studies are needed to elucidate the contribution of anti-TNF-a therapy to development of listeriosis. Physicians should be aware of the possibility of Listeria infection in individuals receiving anti-TNF therapy.

Keywords: Listeria, Infliximab, Endocarditis

Introduction

The treatment of inflammatory joint diseases has changed dramatically over the past few years with the introduction of anti-tumor necrosis factor agents such as infliximab (Remicade®, Centocor), etanercept (Enbrel®, Wyeth) and adalimumab (Humira®, Abbott). Infliximab is a human/murine chimeric monoclonal antibody directed against tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α). TNF-a is a critical component of the host immune response, and anti-TNF therapy therefore increases in the rate of sometimes life-threatening complications, including Listeria infection. However, the reported rate of listeriosis in patients who use infliximab is likely to be an underestimate of the incidence rate due to underreporting of Listeria infections. Except for the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Adverse Event Reporting System (AERS) database, there are no reviews, to our knowledge, summarizing the available published scientific evidence regarding listeriosis induced by TNF-a inhibitors and more specifically infliximab. Herein, we report a case of Listeria endocarditis associated with infliximab use in a patient with psoriatic arthritis. We also review the literature regarding the association of infliximab with Listeria infection.

Methods

All previous cases included in our literature review were found using a PubMed search (1990–October 2009) of the English-language medical literature applying the terms “infliximab” and “Listeria”. The references cited in these articles were examined to identify additional reports. We have also extrapolated available data (type of infection, mortality, age, sex) regarding cases of Listeria infections associated with use of infliximab from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Adverse Event Reporting System (AERS) database.

Case report

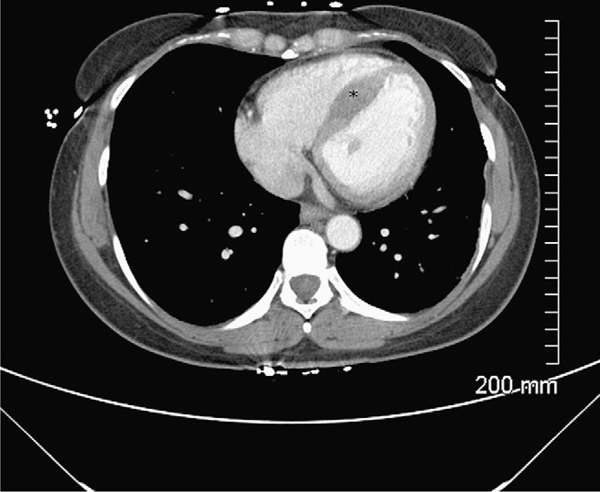

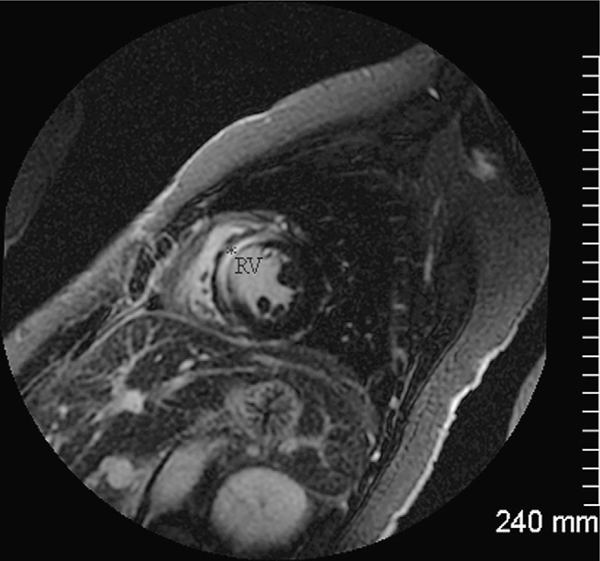

A 42 year old female with a history of psoriatic arthritis being treated with infliximab for the past 6 months, presented with one month history of fever, night sweats, anorexia, arthralgias and generalized malaise. She also complained of intermittent chest pressure during the peak temperature spikes. She had received 5 monthly infusions of infliximab in the dosage of 5 mg/kg at the time of presentation and reported considerable relief of her arthritic and skin symptoms. Prior to being started on infliximab she had been treated with methotrexate, etanercept and adalimumab, with incomplete clearance of skin lesions and persistent arthralgias. On presentation the patient was afebrile, with an unremarkable physical examination except for chronic changes of psoriatic arthritis. A white blood cell count was 9200 cells/mm3 with 74% polymorphonuclear cells and other laboratory data were unremarkable with the exception of mildly elevated troponin I with otherwise normal cardiac enzymes. An EKG revealed sinus rhythm with non specific ST-T changes. Blood cultures were positive for Listeria monocytogenes. Whole body imaging with computed tomography scans failed to show any evidence of focal abscess formation. However, a computed tomography of the chest with intravenous contrast revealed localized infarction of the inter-ventricular septal wall (Fig. 1). A transthoracic echocardiogram showed presence of normal ejection fraction with anterior and septal wall motion abnormality. A transesophageal echocardiogram showed a hypokinetic anterior myocardial septum and vegetations on the aortic valve. A cardiac magnetic resonance imaging was also performed to evaluate for myopericarditis, which showed evidence of an acute infarct in the subendocardial region of the septal wall of the left ventricle and wall motion abnormalities (Fig. 2).

Figure 1.

Computed tomography of the chest with intravenous contrast showing septal infarction (asterisk).

Figure 2.

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging shows evidence of late gadolinium enhancement (asterisk) confined to the subendocardial portion of the septal myocardial wall of the right ventricle (RV) on inversion recovery images in the short-axis plane indicating myocardial damage.

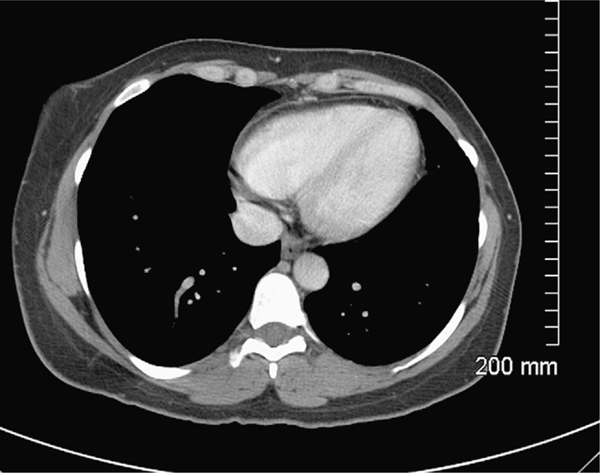

During her hospitalization, the patient made a quick recovery with resolution of her symptoms with initiation of intravenous high dose ampicillin 2 gm i.v q 4 h and was discharged to complete a 6 week course of antibiotic therapy. At follow up she continues to do well with resolution of all symptoms and negative blood cultures while a repeat computed tomography of the chest revealed resolution of the aforementioned lesions (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Computed tomography of the chest with intravenous contrast showing resolution of septal infarction after treatment.

Results

We identified 92 cases of L. monocytogenes infections related to infliximab treatment in the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Adverse Event Reporting System (AERS) database.1Listeria infections reported included meningitis in 69 cases (75%), sepsis in 20 cases (21.7%) and listeriosis in 3 cases (3.3%).1 In 14/69 (20.3%) cases of meningitis there was also encephalitis and in 4/69 (5.8%) cases there was also coexistent listeriosis and sepsis. Among cases with available data, 51.7% were female and the average age was 48.6 years (range 12–80). Mortality was 17.4% (16/92 cases) and 15/16 (93.8%) of the fatalities had meningitis and one had sepsis. However, no further information was available regarding most of these 92 cases from the FDA AERS database.

We further identified 33 cases of L. monocytogenes infection related to infliximab treatment that have been published to date (Table 1).2–20 Nine cases were excluded due to non-English language2,5–7,9,12,14–16and we included 24 cases in our review (Table 1). Listeria infections related with infliximab presented as meningitis in 14 cases (58.3%)3,11,13,17–21isolated bacteremia in 6 cases (25%),4,8,10,20 cholecystitis with associated bacteremia in 2 cases10,20 and septic arthritis in 2 cases.10,20 Thirteen patients (54.2%)10,17,20,21 had rheumatoid arthritis, 10 (41.7%) patients had Crohn’s disease8,20,4,11,13,19 and only one case of Listeria meningitis closely related to infliximab therapy has been reported in a patient with psoriatic arthritis.18 With the exception of two cases of Listeria infection occurring after the sixth dose of infliximab,4,10 the average number of infliximab doses prior to the Listeria infection was 2.5 (data from 21 available cases). These results are consistent with the data from the FDA AERS report where Listeria infections occurred early after the initiation of the therapy, with a median number of doses received of 2.5.1,20 The most serious infections after infliximab treatment occur after three or fewer infusions.20 In clinical studies there seemed to be no correlation between the number of infusions and the rate of infectious events.22Almost all of the reported patients were also concomitantly taking other immunosuppressive therapies including corticosteroids, azathioprine or 6-mercaptopurine.8,11,17,20

Table 1.

Cases of Listeria infections associated with infliximab use.

| Author | Year | Country | Age | Sex | Type of infection | Symptoms | Isolation of L. mono cytogenes | Underlying disease | Doses of infliximab | Concomitant drugs | Treatment | Outcome | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Morelli et al8 | 2000 | USA | 67 | M | Bacteremia | Fever, diarrhea, lethargy, weakness | Blood | Crohn’s disease | 3 (4 days after 3rd infusion) | Prednisone, AZA, 5-ASA | Broad spectrum antibiotics for 4 days (NR) and then augmentin for 2 weeks | Recovered | Ingestion of processed meat the week prior to the admission |

| Gluck et al21 | 2002 | Germany | 60 | F | Bacteremia, cholecystitis meningoence halitis | Fever, abdominal pain | Swab culture from the gallbladder obtained during surgery and a blood culture | Rheumatoid arthritis | 6 (14 days after 6th dose) | Methotrexate, cyclosporin A, prednisolone | Cefriaxone, metronidazole | Death | Food NR |

| Gluck et al21 | 2002 | Germany | 62 | F | Bacteremia, cholecystitis, brain abscess | Fever, abdominal pain and later hemiparesis, aphasia | Blood | Rheumatoid arthritis | 2 (14 days after 2th dose) | Methotrexate | Ampicillin and gentamicin for a total of 18 weeks | Slow improvement of the neurologic symptoms | Food NR |

| Kamath et al11 | 2002 | USA | 17 | F | Bacteremia/meningitis | Fever, headache, malaise, abdominal pain | Blood, CSF culture negative (done 4 days on antibiotics) | Crohn’s disease | 1 (3 days after infusion) | Methylpredn isolone, 6-MP, 5-ASA | Ampicillin and cotrimoxazole for 6 weeks | Prolonged hospital course but fully recovered | Patient denied eating any suspicious food before symptoms |

| Aparicio et al18 | 2003 | Spain | 57 | M | Meningitis | Headache, fever, confusion, vomiting | CSF | Psoriatic arthritis | 6 (one month after 6th infusion) | Methotrexate, Prednisone | Ampicillin (duration NR) | Recovered | Food NR |

| Slifman et al (surveillance study)20 | 2003 | USA, Canada, Sweden, Italy, Germany, France, Norway | Median age 69.5 years (range 17–80 years) | 53% F (8/15) | Sepsis, meningitis, septic joint | NR | CSF, blood | 9 patients with RA and 5 patients with Crohn’s, one patient no data reported. 3 of thesecases have already been described in the literature7,10,20 | Median number of doses was 2.5 (range 1–6). | All patients were on steroids. Of the 9 patients with RA, 7 were reported as receiving concomitant methotrexate, and 1 was receiving cyclosporine (in addition to methotrexate). Of the 5 patients with CD, 1 was receiving mercaptopurine only, 2 were receiving mercaptopurine plus mesalamine, and 2 were receiving azathioprine plus mesalamine. | NR | 5 deaths | Only one patient7 was reported as having ingested processed meat in the week preceding the diagnosis of listeriosis. |

| Slifman et al20 | 2003 | Canada | 64 | F | Blood | NR | Blood | Crohn’s disease | 1 | Prednisone, 6-MP | NR | Recovered | NR |

| Slifman et al20 | 2003 | Sweden | 39 | F | Blood/meningitis | NR | Blood, CSF | Crohn’s disease | 3 | Prednisone, 6-MP, 5-ASA | NR | Recovered, paralysis of one eye | NR |

| Slifman et al20 | 2003 | Italy | 20 | M | Meningitis | NR | CSF | Crohn’s disease | 1 | Methylpredn isolone, AZA, 5-ASA | NR | Death | NR |

| Slifman et al20 | 2003 | USA | 80 | M | Blood/meningitis | NR | Blood, CSF | RA | 2 | Prednisone | NR | Death | NR |

| Slifman et al20 | 2003 | USA | 74 | F | Meningitis | NR | CSF | RA | 6 | Prednisone | NR | Death | NR |

| Slifman et al20 | 2003 | USA | 78 | M | Meningitis | NR | CSF | RA | 3 | Methotrexate | NR | Remained comatose at time of report | NR |

| Slifman et al20 | 2003 | USA | 73 | F | Blood, possible meningitis | NR | Blood | RA | 2 | Prednisone, methotrexate, nycophenolate mofetil | NR | Death | NR |

| Slifman et al20 | 2003 | USA | 74 | F | Blood | NR | Blood | RA | 5 | Prednisone, methotrexate, hydroxychloroquine | NR | Recovered | NR |

| Slifman et al20 | 2003 | USA | 73 | M | Meningitis | NR | CSF | RA | NR | Prednisone, methotrexate, leflunomide | NR | NR | NR |

| Slifman et al20 | 2003 | Canada | 60 | M | Blood | NR | Blood | RA | 2 | Methotrexate | NR | NR | NR |

| Slifman et al20 | 2003 | France | NR | F | Septic joint | NR | Synovial fluid | RA | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Tweezer-Zaks et al3 | 2003 | Israel | 48 | M | Blood, splenic abscess | Fever, rigors, headache | Blood | Crohn’s disease | 1 (9 days after infusion) | NR | Ampicillin, gentamycin and mertonidazole (duration NR) | Recovered | NR |

| Tweezer-Zaks et al4 | 2003 | Israel | 55 | F | Blood | Fever, chills, malaise, mild dysuria | Blood | Crohn’s disease | 2 year history of infliximab use (2 weeks after last infusion) | Prednisone, methotrexate | Ampicillin, gentamycin (duration NR) | Recovered | NR |

| Ljung et al19 | 2004 | Sweden | NR | NR | Meningitis | NR | CSF | Crohn’s disease | NR | NR | NR | Recovered | NR |

| Bowie et al17 | 2004 | USA | 73 | M | Meningitis | Decreased level of consciousness, headache, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea for 3 days | CSF culture, blood | Rheumatoid arthritis | 2 (3 weeks prior to symptoms) | Prednisone, methotrexate | Ampicillin for 21 days | Recovered | No change in food habits |

| Williams et al3 | 2005 | Canada | 37 | M | Meningitis | Fever, tachycardia, diaphoresis, confusion | Blood cultures, CSF culture | Crohn’s disease | 2 (6 days after second infusion) | Prednisone, AZA, 5-ASA | Iv ampicillin and gentamicin, later switched to iv ampicillin and trimethoprime sulfamethoxazole for a total of three weeks | Recovered | NR |

| Kesteman at al10 | 2007 | Belgium | 52 | F | Terminal ileitis and bacteremia | Fever, abdominal pain, diarrhea | Blood | Rheumatoid arthritis | 3 (one week after infusion) | Prendisone, nethotrexate | sulfamethoxaz oletrimethoprim and gentamicin IVand then PO sulfamethoxaz oletrimethoprim for a total of 30 days | Recovered | |

| Kesteman at al10 | 2007 | Belgium | 79 | M | Bacteremia associated with a prosthetic joint arthritis of the left hip | Fever, leg pain | Blood, intra-articular fluid from the left hip | Rheumatoid arthritis | 4 years on infliximab (30 infusions) | Prendisone, nethotrexate | Ampicilliin for 2 weeks initially then ampicillin, rifampicin, gentamicin followed by a surgical arthrocentesis with debridement and combined with a long term antimicrobial treatment with amoxicillin (exact duration NR). | Recovered | The patient admitted consumption of soft cheeses some weeks before admission. |

| Izbeki et al13 | 2008 | Hungary | 50 | M | Meningoenc ephalitis | Fever, headache, neck stiffness, | CSF | Crohn’s disease | 1 (one day after infusion) | Prednisone, 6-MP | Ampicillin, gentamicin | Residual unilateral weakness of eye movements | NR |

Abbreviations: AZA: Azathioprine, CSF: cerebrospinal fluid F: Female, MP: Mercaptopurine, M: male, NR: Not reported, RA: Rheumatoid Arthritis.

Discussion

Pathogenesis of infliximab induced listeriosis

The mechanism how TNF-a inhibitors such as infliximab predispose to Listeria infection is unclear. Infliximab is thought to neutralize the biologic activity of TNF-a by binding to the soluble and transmembrane forms of TNF-a, thereby preventing the interaction of TNF-a with its cellular receptors (TNFRs).4,8,20 Infliximab binds and clears soluble TNF-α, thereby neutralizing its proinflammatory effects. It also binds to cell-bound TNF-α on macrophages and T cells, which interferes with direct cell-to-cell interactions and facilitates their destruction. Although host resistance to infection with L. monocytogenes is complex and likely involves multiple cell types,23 TNF-a is critical in host defense against Listeria. The presence of this cytokine and its type I receptor, p55, seems to be critical for resistance against primary infection by this intracellular pathogen.23 TNF-a is produced within minutes of infection and its serum levels increase in parallel to the bacterial load, peaking before host death.23 Animal studies have demonstrated that treatment with anti-TNF-a, both before or during Listeria infection resulted in premature host death with large numbers of bacterial copies per cell.24,25 Moreover, TNF-α-deficient mice were highly susceptible to Listeria infection.26 Anti-TNF-a therapy abolishes the activation of different cell lines including monocytes, macrophages, T lymphocytes and neutrophils.23 Metalloproteinases have also been implicated in the modulation the immune response against Listeria infection.27 The dysregulation of matrix metalloproteinases, produced by TNF-a blockers, has been linked to several infectious diseases, including bacterial meningitis, endotoxic shock, mycobacterial infection, and hepatitis B and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection.28 Effective therapy with anti-TNF-a in patients with psoriatic arthritis is associated with decreased levels of metalloproteinases and angiogenic cytokines in the sera and skin lesions.29 Conclusively, further studies are needed to elucidate the mechanism of how infliximab may predispose to development of serious infections including Listeria infection.

Incidence of infections in infliximab treated patients

The treatment of inflammatory joint diseases has changed dramatically over the past few years with the introduction of anti-tumor necrosis factor agents. Anti-TNF-a is an emerging as well as a promising therapy in refractory rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel diseases such as active Crohn’s disease, spondyloarthropathies such as psoriatic arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis.30 One of these currently available agents is infliximab (Remicade®, Centocor) which is a human/murine chimeric monoclonal antibody directed against tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α). TNF-a plays an important role in host resistance against various microorganisms, particularly those that are intracellular,4,8,20 and increasing number of reports indicate that sometimes life-threatening infections, including opportunistic infections, can be a high price to pay for these therapeutic options.31,32 Although the incidence of opportunistic infections with use of infliximab is extremely low (Category C and D evidence),32 infections whose containment is macrophage dependent, such as listeriosis, histoplasmosis or coccidiomycosis have been reported.32

In clinical studies the rate of serious infections after anti-TNF-a therapy ranged from 2 to 6.4%.10,33–36 A meta-analysis showed an increased risk of serious infections in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with anti-TNF antibody therapy (pooled odds ratio for serious infection was 2.0; 95% CI, 1.3–3.1).31 Pooled data from all Centocor sponsored clinical trials, involving 2292 patients, showed comparable death rates among placebo and infliximab treated patients (2% and 1%, respectively) and similar occurrence of serious infections.37 A registry study (RABBIT) of German patients receiving anti-TNF therapy for rheumatoid arthritis found an increased risk of infection among patients treated with any biologic agents, but that addition of anti-TNF inhibitors further increased the risk after adjusting for other predictive factors of infection risk, including patient age and disease severity.33In a large retrospective study of 709 patients with rheumatoid arthritis, the incidence of serious infections in patients treated with TNF-a blockers was three times higher than controls38 in contrast to placebo-controlled trials.20,39,40 Discrepancies between different clinical trials20,39,40 and meta-analyses31 may be explained by the difference in selection criteria of patients, lack of long term follow up in all studies, differences in sample size and rarity of infections.

However, the experience with infliximab remains limited in other rheumatic diseases such as psoriatic arthritis.

In contrast to patients with rheumatoid arthritis, there does not appear to be an increased rate of infections among patients with psoriatic arthritis receiving anti-TNF therapy. In a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials assessing the risks and benefits of tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors in the management of psoriatic arthritis,41 there were no significant differences between TNF-a inhibitors and placebo in the proportions of patients experiencing serious adverse events (RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.55–1.77), or upper respiratory tract infections (RR 0.91, 95% CI 0.65–1.28). In two randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials in patients with psoriatic arthritis treated with infliximab—the IMPACT (Infliximab Multinational Psoriatic Arthritis Controlled Trial)42 and the IMPACT II43,44 the investigators found no significant differences in the numbers or types of adverse events reported in infliximab treatment or placebo groups. In IMPACT I, 104 patients with psoriatic arthritis were followed for one year after starting treatment with infliximab, and the study failed to prove any difference in the incidence of infections between the infliximab treated and the placebo treated group.45 In the 2 year follow up of the IMPACT study again there was no difference in the incidence of infections between the infliximab treated and the placebo group.46The IMPACT II study evaluated the safety of infliximab after 1 year of treatment in 200 patients with psoriatic arthritis. No difference in the incidence of infections between the infliximab, the infliximab plus methotrexate and the placebo group was found.44 No reports of tuberculosis or opportunistic infection were reported in both IMPACT studies. Thus, although meta-analyses and controlled clinical trials have shown an increase in the incidence of serious infections in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with TNF-a blockers, there is limited experience with the use of infliximab in patients with psoriatic arthritis. One meta-analysis41 and 2 randomized controlled trials42–44 have shown that infliximab does not increase the incidence of infections between the infliximab treated patients with psoriatic arthritis and the placebo group. This may represent differences in the immunopathogenesis between different inflammatory disorders including psoriatic and rheumatoid arthritis. However, any comparison of data between different studies is very difficult in the setting of lack of long term controlled studies and is an important area for future research to assess the long term risk—benefit profile of these biological agents in treatment of inflammatory conditions including psoriatic arthritis.

Infliximab and listeriosis

Listeria infection is an opportunistic infection that has been reported in patients who undergo treatment with anti-TNF-a therapy. A confounding factor that may make comparison of the incidence of listeriosis between different studies difficult is the extent to which other immunomodulating drugs influence susceptibility to serious infections in patients on infliximab.11 Reports from the AERS suggest that the number of patients with Listeria may be higher than those reported by post-marketing. Patients with predisposing conditions, such as older age (>75 years), pregnancy, diabetes mellitus, immune suppression, liver failure, HIV infection, splenectomy may have an incidence of listeriosis as high as 210 cases per 100,000 (as compared with 0.7 per 100,000 cases in healthy individuals), and mortality that can reach 30%.47The estimated annual rate of reports to the FDA of listeriosis in infliximab-treated patients is greater than the FoodNet (the principal foodborne disease component of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Emerging Infections Program)-derived annual incidence rate of listeriosis.17,20,21 There have been twice as many cases of serious Listeria infections in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with anti-TNF-α compared with patients with Crohn’s disease. Infliximab-linked Listeria infections have also been reported in patients with ulcerative colitis, psoriatic arthritis and juvenile rheumatoid arthritis.18,20

However, Listeria endocarditis, a rare complication of bacteremia due to Listeria,48 associated with use of infliximab has not been previously described, to our knowledge. According to the modified Duke criteria for endocarditis,48 our patient had a major diagnostic criterion for endocarditis (presence of vegetation on echocardiogram) and 3 minor criteria (vascular pheonomena/septic emboli in coronary arterioles with subendothelial infarct, history of fever, and positive blood cultures for an atypical organism). This is also the second published case of Listeria infection associated with infliximab in patients with psoriatic arthritis. A unique feature of this case is that it was associated with use of infliximab without the simultaneous use of other immunosuppressive agents. However, underlying psoriatic arthritis would also increase her risk for a Listeria infection by impairing T lymphocyte/macrophage—mediated cellular immunity. It is not clear whether Listeria infections originate from ingestion of contaminated food or from chronic fecal carriage in these immunocompromised patients. A possible dietary source for the Listeria was identified in our patient since she admitted ingestion of soft cheeses and dairy products. Ingestion could have occurred up to 70 days prior to admission. Anti-TNF-a therapy may be a significant risk factor for the development of listeriosis, although most of the patients are immunocompromised due both to their chronic inflammatory illness and concurrent immune suppressive therapy. Patients starting infliximab therapy should be warned to avoid soft cheeses, non-pasteurized dairy products and undercooked meats during therapy, and physicians should be aware of the possibility of Listeria infection in such individuals. Early recognition of Listeria infection as a potential complication of treatment with TNF-a-neutralizing agents may decrease the high morbidity and mortality associated with this disease.

Acknowledgments

Funding source

None.

Footnotes

Ethical approval

Yes.

Conflict of interest statement

None.

References

- 1.http://www.fdable.com/aers/query/972d415847bf/7 [last visited 1/20/2010]. http://wwwfdablecom/aers/query/972d415847bf/7 [last visited 1/20/2010], 2010.

- 2.Yamamoto M, Takahashi H, Miyamoto C, et al. A case in which the subject was affected by Listeria meningoencephalitis during administration of infliximab for steroid-dependent adult onset Still’s disease. Nihon Rinsho Meneki Gakkai Kaishi 2006;29(3):160–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams G, Khan AA, Schweiger F. Listeria meningitis complicating infliximab treatment for Crohn’s disease. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol 2005;16(5):289–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tweezer-Zaks N, Shiloach E, Spivak A, Rapoport M, Novis B, Langevitz P. Listeria monocytogenes sepsis in patients treated with anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Isr Med Assoc J 2003; 5(11):829–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Soderlin M, Blomkvist C, Dahl P, Forsberg P, Fohlman J . Increased risk of infection with biological immunomodifying antirheumatic agents. Clear guidelines are necessary as shown by case reports. Lakartidningen 2005;102(49):3794–800. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramanampamonjy RM, Laharie D, Bonnefoy B, Vergniol J, Amouretti M. Infliximab therapy in Crohn’s disease complicated by Listeria monocytogenes meningoencephalitis. Gastroenterol Clin Biol 2006;30(1):157–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Osuna MR, Ferrer RT, Gallego GR, Ramos LM, Ynfante FM, Figueruela LB. Listeria meningitis as complication of treatment with infliximab in a patient with Crohn’s disease. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2006;98(1):60–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morelli J, Wilson FA. Does administration of infliximab increase susceptibility to listeriosis? Am JGastroenterol 2000;95(3):841–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keulen ET, Mebis J, Erdkamp FL, Peters FP. Meningitis due to Listeria monocytogenes as a complication of infliximab therapy. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 2003;147(43):2145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kesteman T, Yombi JC, Gigi J, Durez P. Listeria infections associated with infliximab: case reports. Clin Rheumatol 2007; 26(12):2173–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kamath BM, Mamula P, Baldassano RN, Markowitz JE. Listeria meningitis after treatment with infliximab. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2002;34(4):410–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Joosten AA, van Olffen GH, Hageman G. Meningitis due to Listeria monocytogenes as a complication of infliximab therapy. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 2003;147(30):1470–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Izbeki F, Nagy F, Szepes Z, Kiss I, Lonovics J, Molnar T. Severe Listeria meningoencephalitis in an infliximab-treated patient with Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2008;14(3):429–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dederichs F, Pinciu F, Gerhard H, Eveld K, Stallmach A. Listeria meningitis in a patient with Crohn’s disease—a seldom, but clinically relevant adverse event of therapy with infliximab. Z Gastroenterol 2006;44(8):657–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de la Fuente PB, Marco PA, Riera MA, Boadas MJ. Sepsis caused by Listeria monocytogenes related with the use of infliximab. Med Clin (Barc) 2005;124(10):398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cabades OF, Vila FV, Arnal BM, Polo Sanchez JA. Lysteria encephalitis associated to infliximab administration. Rev Clin Esp 2005;205(5):250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bowie VL, Snella KA, Gopalachar AS, Bharadwaj P. Listeria meningitis associated with infliximab. Ann Pharmacother 2004;38(1):58–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aparicio AG, Munoz-Fernandez S, Bonilla G, Miralles A, Cerdeno V, Martin-Mola E. Report of an additional case of anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy and Listeria monocytogenes infection: comment on the letter by Gluck et al. Arthritis Rheum 2003;48(6):1764–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ljung T, Karlen P, Schmidt D, et al. Infliximab in inflammatory bowel disease: clinical outcome in a population based cohort from Stockholm county. Gut 2004;53(6):849–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Slifman NR, Gershon SK, Lee JH, Edwards ET, Braun MM. Listeria monocytogenes infection as a complication of treatment with tumor necrosis factor alpha-neutralizing agents. Arthritis Rheum 2003;48(2):319–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gluck T, Linde HJ, Scholmerich J, Muller-Ladner U, Fiehn C, Bohland P. Anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy and Listeria monocytogenes infection: report of two cases. Arthritis Rheum 2002;46(8):2255–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hanauer SB, Feagan BG, Lichtenstein GR, et al. Maintenance infliximab for Crohn’s disease: the ACCENT I randomised trial. Lancet 2002;359(9317):1541–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Edelson BT, Unanue ER. Immunity to Listeria infection. Curr Opin Immunol 2000;12(4):425–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pfeffer K, Matsuyama T, Kundig TM, et al. Mice deficient for the 55 kd tumor necrosis factor receptor are resistant to endotoxic shock, yet succumb to L. monocytogenes infection. Cell 1993; 73(3):457–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rothe J, Lesslauer W, Lotscher H, et al. Mice lacking the tumour necrosis factor receptor 1 are resistant to TNF-mediated toxicity but highly susceptible to infection by Listeria monocytogenes. Nature 1993;364(6440):798–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mizuki M, Nakane A, Sekikawa K, Tagawa YI, Iwakura Y. Comparison of host resistance to primary and secondary Listeria monocytogenes infections in mice by intranasal and intravenous routes. Infect Immun 2002;70(9):4805–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bitar AP, Cao M, Marquis H. The metalloprotease of Listeria monocytogenes is activated by intramolecular autocatalysis. J Bacteriol 2008;190(1):107–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Elkington PT, O’Kane CM, Friedland JS. The paradox of matrix metalloproteinases in infectious disease. Clin Exp Immunol 2005;142(1):12–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cordiali-Fei P, Trento E, D’Agosto G, et al. Decreased levels of metalloproteinase-9 and angiogenic factors in skin lesions of patients with psoriatic arthritis after therapy with anti-TNF-alpha. J Autoimmune Dis 2006;3:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schluter D, Deckert M. The divergent role of tumor necrosis factor receptors in infectious diseases. Microbes Infect 2000; 2(10):1285–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bongartz T, Sutton AJ, Sweeting MJ, Buchan I, Matteson EL, Montori V. Anti-TNF antibody therapy in rheumatoid arthritis and the risk of serious infections and malignancies: systematic review and meta-analysis of rare harmful effects in randomized controlled trials. JAMA 2006;295(19):2275–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wallis RS, Broder MS, Wong JY, Hanson ME, Beenhouwer DO. Granulomatous infectious diseases associated with tumor necrosis factor antagonists. Clin Infect Dis 2004;38(9):1261–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Listing J, Strangfeld A, Kary S, et al. Infections in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with biologic agents. Arthritis Rheum 2005;52(11):3403–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Salliot C, Gossec L, Ruyssen-Witrand A, et al. Infections during tumour necrosis factor-alpha blocker therapy for rheumatic diseases in daily practice: a systematic retrospective study of 709 patients. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2007;46(2):327–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Furst DE, Breedveld FC, Kalden JR, et al. Updated consensus statement on biological agents for the treatment of rheumatic diseases. Ann Rheum Dis 2006;65(Suppl. 3):iii2–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kroesen S, Widmer AF, Tyndall A, Hasler P. Serious bacterial infections in patients with rheumatoid arthritis under anti-TNF-alpha therapy. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2003;42(5): 617–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stamm AM, Smith SH, Kirklin JK, McGiffin DC. Listerial myocarditis in cardiac transplantation. Rev Infect Dis 1990;12(5): 820–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Giunta G, Piazza I. Fatal septicaemia due to Listeria monocytogenes in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus receiving cyclosporin and high prednisone doses. Neth J Med 1992;40(3–4):197–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moreland LW, Cohen SB, Baumgartner SW, et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of etanercept in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 2001;28(6):1238–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van de Putte LB, Atkins C, Malaise M, et al. Efficacy and safety of adalimumab as monotherapy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis for whom previous disease modifying antirheumatic drug treatment has failed. Ann Rheum Dis 2004;63(5):508–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Saad AA, Symmons DP, Noyce PR, Ashcroft DM. Risks and benefits of tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors in the management of psoriatic arthritis: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Rheumatol 2008;35(5):883–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1981;30(2):239–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Antoni C, Krueger GG, de VK, et al. Infliximab improves signs and symptoms of psoriatic arthritis: results of the IMPACT 2 trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2005;64(8):1150–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kavanaugh A, Krueger GG, Beutler A, et al. Infliximab maintains a high degree of clinical response in patients with active psoriatic arthritis through 1 year of treatment: results from the IMPACT 2 trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2007;66(4):498–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Antoni CE, Kavanaugh A, Kirkham B, et al. Sustained benefits of infliximab therapy for dermatologic and articular manifestations of psoriatic arthritis: results from the infliximab multinational psoriatic arthritis controlled trial (IMPACT). Arthritis Rheum 2005;52(4):1227–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Antoni CE, Kavanaugh A, van der HD, et al. Two-year efficacy and safety of infliximab treatment in patients with active psoriatic arthritis: findings of the infliximab multinational psoriatic arthritis controlled trial (IMPACT). J Rheumatol 2008;35(5):869–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Southwick FS, Purich DL. Intracellular pathogenesis of listeriosis. N Engl J Med 1996;334(12):770–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fernandez Guerrero ML, Rivas P, Rabago R, Nunez A, de GM, Martinell J. Prosthetic valve endocarditis due to Listeria monocytogenes. Report of two cases and reviews. Int J Infect Dis 2004;8(2):97–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]