Abstract

Occlusion of blood vessel caused by thrombus is the major pathogenesis of various catastrophic cardiovascular diseases. Thrombus can be prevented or treated by antithrombotic drugs. However, free antithrombotic drugs often have relatively low therapeutic efficacy due to a number of limitations such as short half-life, unexpected bleeding complications, low thrombus targeting capability, and negligible hydrogen peroxide (H2O2)-scavenging ability. Inspired by the abundance of H2O2 and the active thrombus-targeting property of platelets, a H2O2-responsive platelet membrane-cloaked argatroban-loaded polymeric nanoparticle (PNPArg) was developed for thrombus therapy. Poly(vanillyl alcohol-co-oxalate) (PVAX), a H2O2-degradable polymer, was synthesized to form an argatroban-loaded nanocore, which was further coated with platelet membrane. The PNPArg can effectively target the blood clots due to the thrombus-homing property of the cloaked platelet membrane, and subsequently exert combined H2O2-scavenging effect via the H2O2-degradable nanocarrier polymer and antithrombotic effect via argatroban, the released payload. The PNPArg effectively scavenged H2O2 and protected cells from H2O2-induced cellular injury in RAW 264.7 cells and HUVECs. The PNPArg rapidly targeted the thrombosed vessels and remarkably suppressed thrombus formation, and the levels of H2O2 and inflammatory cytokine in the ferric chloride-induced carotid arterial thrombosis mouse model. Safety assessment indicated good biocompatibility of the PNPArg. Taken together, the biomimetic PNPArg offers multifunctionalities including thrombus-targeting, antioxidation, and H2O2-stimulated antithrombotic action, thereby making it a promising therapeutic nanomedicine for thrombosis diseases.

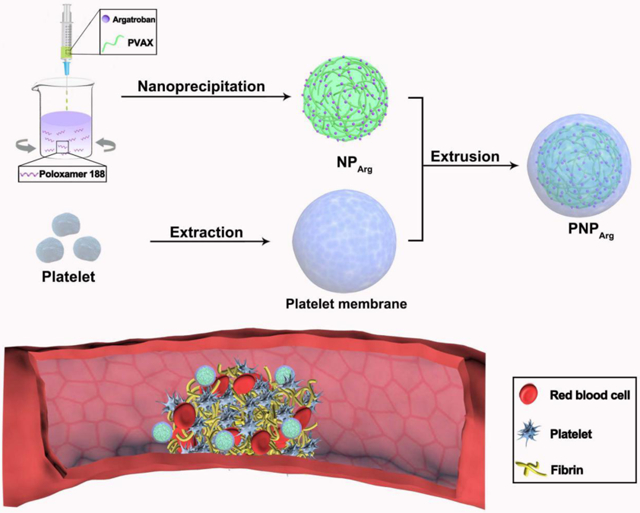

Graphical Abstract

A schematic diagram of the PNPArg as a thrombus-targeting antithrombotic agent.

1. Introduction

Acute occlusion of blood vessel by thrombus is the primary cause of many cardiovascular conditions including ischemic stroke,1 acute myocardial infarction,2 and pulmonary embolism3. Antithrombotic drugs have been widely used to prevent the vessel occlusion. However, such treatment is often associated with low therapeutic efficacy due to the short half-life and lack of targeting capability, as well as bleeding complications. Thus, there is a need to develop an alternative and more effective drug delivery approach such as smart drug delivery nanocarriers that enable active thrombus targeting ability, long circulation time, and stimulus-controlled drug release for efficient thrombus therapy.

It is well known that reactive oxygen species (ROS), which is derived from activated platelets and interrupted endothelial cells, plays crucial roles in thrombus formation by promoting platelet-endothelium interactions and endothelial dysfunction.4-7 The excessive ROS also stimulates the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines on the endothelium and facilitates vessel occlusion.8-9 Therefore, depletion of ROS would be an attractive therapeutic approach to prevent thrombus formation. Moreover, the locally increased ROS level, a specific feature at the thrombus site, can be utilized to control the drug release. Poly(vanillyl alcohol-co-oxalate) (PVAX), a biodegradable polymer antioxidant, has been developed to neutralize excessive ROS and suppress inflammation.10-12 PVAX exhibits high anti-oxidative capability because of the combined effects of the ROS-scavenging peroxalate ester linkages and the concurrent ROS-triggered release of bioactive vanillyl alcohol (VA). Therefore, we speculated that we could develop an effective antithrombotic therapy by encapsulating antithrombotic agents into the anti-oxidative PVAX nanoparticles.

Cell membrane-camouflaged delivery systems have emerged as promising therapeutic platforms.13 They are fabricated by coating natural plasma membranes onto the surface of synthetic nanocores, and thus they can integrate the biomimetic features of cell membrane with the versatile functions of the nanocores.14-19 Platelets play a key role in thrombus formation.20 After vessel denudation, platelets can adhere to the thrombogenic materials such as von Willebrand factors and collagens via platelet surface receptors, and then activate internal signal pathways and release potent platelet agonists to recruit more platelets, promote platelet aggregation and fibrin crosslinking, and finally accelerate the formation of life-threatening thrombus.20 Inspired by the natural thrombus homing property of platelet, we hypothesized that nanoparticles coated with platelet membrane can effectively target thrombus sites.21-22

In this study, a hydrogen peroxide (H2O2)-responsive platelet membrane-camouflaged drug-loaded polymeric nanoparticle (PNPArg) was engineered for the treatment of thrombus. Argatroban was selected as the model antithrombotic agent, which is an anticoagulant with a half-life about 50 min after intravenous administration and can directly inhibit thrombin-induced reactions, including fibrin formation, platelet aggregation, and activation of coagulation factors V, VIII, and XIII. Platelet membrane coating confers nanoparticles with excellent thrombus homing characteristics via the specific interaction between glycoproteins (GPIbα and GPVI) on the surface of platelet membrane and the thrombogenic substances that are exposed after vascular injury (e.g., von Willebrand factors and collagens).20 Subsequently, nanoparticles can be degraded and the encapsulated drugs can be released in the presence of the highly abundant H2O2; meanwhile, H2O2 can be scavenged during the oxidation process, thus achieving high antithrombotic therapeutic efficacy due to the combined antithrombotic and anti-oxidative effects. The PNPArg demonstrated efficient H2O2 scavenging capability, and excellent thrombus targeting ability according to in vitro and in vivo studies, respectively. Moreover, in a ferric chloride (FeCl3)-induced carotid arterial thrombosis mouse model, thrombus formation was significantly suppressed with the treatment of the PNPArg. The biomimetic nanocarriers show great promise for the treatment of thrombosis-related vascular diseases.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

Oxalyl chloride and 4-vanillyl alcohol were obtained from Acros Organics (New Jersey, NJ, USA). 1,4-Cyclohexanedimethanol and 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) were purchased from Alfa Aesar (Lancashire, LA, UK) and Abcam (Cambridge, MA, USA), respectively. 2,7-dichlorofluorescein diacetate, Triethylamine, and dihydroethidium were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) was purchased from VWR (Radnor, PA, USA).

2.2. Synthesis and Characterization of Poly(vanillyl alcohol-co-oxalate) (PVAX)

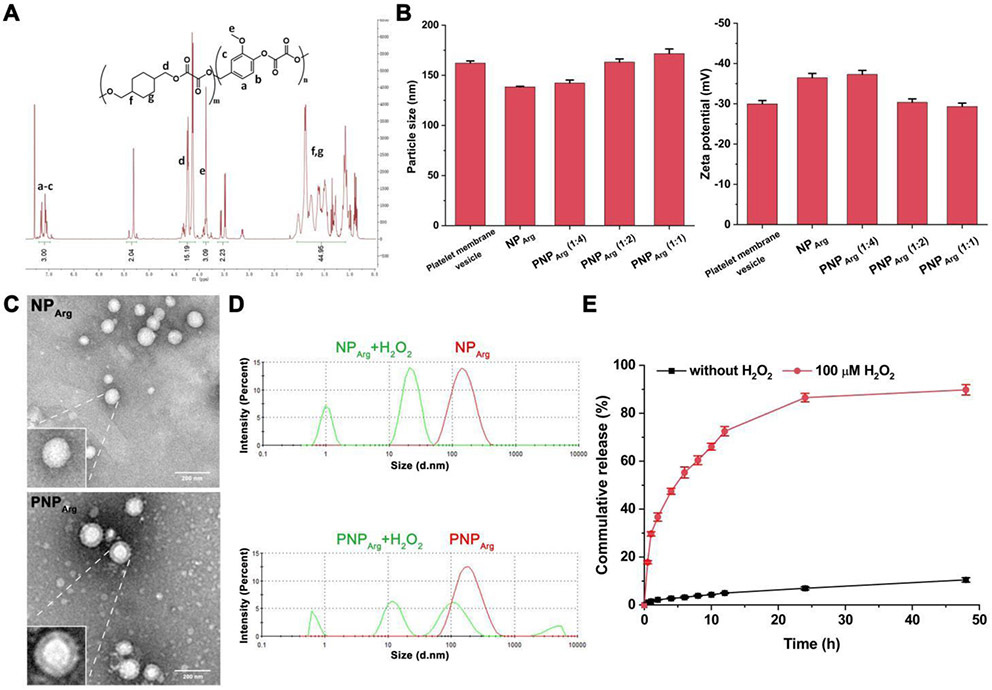

1,4-Cyclohexanedimethanol (10.98 mmol), 4-vanillyl alcohol (2.75 mmol), and triethylamine (30 mmol) were dissolved in anhydrous tetrahydrofuran (THF, 60 mL) and cooled to 0 °C in an ice bath. Oxalyl chloride (13.73 mmol) was dissolved in anhydrous THF (40 mL) and added dropwise into the reaction solution. After 6 h reaction at room temperature under nitrogen, the solvents were removed. The purified PVAX polymer was obtained by extraction using dichloromethane and repeated precipitation in ice-cold hexane for 3 times. The chemical structure of PVAX was verified by a proton nuclear magnetic resonance (1H NMR) spectrometer (Fig. 1A). 1H NMR in deuterated chloroform: 7.0-7.3 (m, 3H, Ar), 5.3 (m, 2H OCH2-Ph), 4.1-4.4 (m, 15.2H, COOCH2C), 3.8 (m, 3H, OCH3), 1.0-1.8 (m, 44H, Cyclic CH2). The molecular weight and polydispersity of the polymer were measured by a gel permeation chromatography (GPC). The weight average molecular weight (Mw) was ~7,600 Da with a polydispersity of 1.48.

Fig. 1.

Characterizations of the nanoparticles. (A) 1H NMR spectrum of poly(vanillyl alcohol-co-oxalate) (PVAX) in deuterated chloroform. *The impurity is due to 1,4-Cyclohexanedimethanol. (B) The change of hydrodynamic diameter and zeta potential of the nanoparticles after coating with platelet membrane (n=3). (C) TEM images of the NPArg and PNPArg. Scale bar: 200 nm. (D) Size distribution of the NPArg and PNPArg induced with 100 μM H2O2 for 1 h and measured by DLS. (E) In vitro release profiles of argatroban from the PNPArg in PBS containing 1% Tween 80 with or without 100 μM H2O2 (n=3).

2.3. Preparation and Characterization of the Nanoparticles

The argatroban-loaded poly(vanillyl alcohol-co-oxalate) Nanoparticle (NPArg) was prepared via nanoprecipitation.21-22 Briefly, a solution in acetone (1 mL) containing PVAX (10 mg) and argatroban (4 mg) was added dropwise into an aqueous solution (5 mL) containing 0.05% (wt/vol) poloxamer 188. The mixture solution was stirred for 4 h to evaporate the acetone and allow the nanoparticle formation. The residual organic solvent was further removed by rotary evaporation.

Platelet membrane-coated argatroban-loaded PVAX nanoparticle (PNPArg) was prepared by coating the NPArg with platelet membrane vesicle using an extrusion method.24 Platelet membrane was derived from platelet-rich plasma using previously described protocols.25 Platelet membrane vesicle was mixed with NPArg at various weight ratios of platelet membrane protein to polymer in NPArg. Thereafter, the mixture was extruded sequentially through a 400-nm and a 200-nm polycarbonate porous membrane using an Avanti mini extruder. The empty PVAX nanoparticle (NP) and empty platelet membrane-coated PVAX nanoparticle (PNP) were prepared via a similar process without adding argatroban. Cy5-loaded nanoparticle was prepared in the same way by replacing argatroban with Cy5.

The size and zeta potential of the nanoparticles (0.1 mg/mL) before and after platelet membrane coating were studied by dynamic light scattering (DLS, ZetaSizer Nano ZS90, Malvern Instruments, USA) (n=3 per group). The morphology and structure of the nanoparticles were investigated by transmission electron microscope (TEM, FEI Tecnai G2 F30 TWIN 300 KV, E.A. Fischione Instruments, Inc. USA). To prepare the TEM samples, the nanoparticle suspension (0.1 mg/mL) was dropped onto a carbon-coated 200-mesh copper grid and then negatively stained with a freshly prepared phosphotungstic acid solution (1%, w/w).

To evaluate the drug loading efficiency and loading content of the PNPArg, the unencapsulated drug was separated from the PNPArg by centrifugation at 3,000 rpm for 20 min using a ultrafiltration tube (molecular weight cut-off at 10 kDa) and was then measured by reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with the absorbance detected at 333 nm.26 The loading efficiency and loading content in percentages were calculated according to the following equations: Loading efficiency (%) = (1 - amount of unencapsulated drug / total amount of drug added) × 100%. Loading content (%) = total weight of encapsulated drug / total weight of nanoparticles × 100%. H2O2-triggered dissociation of the nanoparticles was studied by incubating nanoparticles in 100 μM H2O2 at 37 °C for 1 h. The change of the nanoparticle size was measured by DLS.

In vitro release behavior of argatroban from the PNPArg was investigated by a dialysis method (n=3 per group). Briefly, 1.5 mL of PNPArg aqueous solution was placed inside of a cellulose membrane dialysis bag (molecular weight cut-off of 3.5 kDa), and dialyzed against 0.1 M PBS (pH 7.4, 50 mL) containing 1% Tween 80 with or without 100 μM H2O2 under mild shaking at 37 °C. At predetermined time points, 0.2 mL of the dialysis media was collected. Equivalent volumes of fresh media at 37 °C were immediately added back after each sampling to maintain a constant media volume. The amount of the released argatroban was quantified by HPLC with the absorbance detected at 333 nm. Then, the cumulative amounts of argatroban released were calculated based on a standard curve.

2.4. Cell Lines and Cytotoxicity Assay

Cells were maintained in a humidified cell culture incubator (ThermoFisher, USA) with 5% carbon dioxide at 37 °C. RAW 264.7 macrophages were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco, USA), which was supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (Gibco, USA) as well as 100 units/mL penicillin and streptomycin (Gibco, USA). Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were cultured in endothelial basal medium containing growth supplements. The cytotoxicity of the nanoparticles was tested in RAW 264.7 cells and HUVECs by an MTT assay (n=6 per group). Cells were seeded in 96-well plates with a density of 1 × 104 cells per well. After 24 h, the cells were treated with different concentrations of the nanoparticles and incubated with or without 100 μM H2O2 for 24 h. After washing with PBS, MTT (0.5 mg/mL, 200 μL) solution was added to each well, and the cells were incubated at 37 °C for another 4 h. The MTT-containing media was then aspirated, and the purple precipitates were dissolved by dimethyl sulfoxide (150 μL). The difference between the absorbance at 560 and 650 nm in each well was detected by a GloMax-Multi Microplate Multimode Reader (Promega, WI, USA).

2.5. Measurement of Intracellular ROS

RAW 264.7 cells and HUVECs were incubated with various nanoparticles and free drug in the presence of 100 μM H2O2 for 24 h (n=3 per group). Cells were first washed with PBS and then treated with 2,7-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA, 10 μM) followed by 30 min incubation at 37 °C. Then, cells were washed with PBS and harvested with 0.25% trypsin. Cells were centrifuged at 1000 rpm for 4 min, and were subsequently re-suspended in PBS. Untreated cells were also used as a negative control. The intracellular fluorescence intensity was measured by flow cytometry (Attune NxT flow cytometer system, ThermoFisher, USA), and the results were analyzed by FlowJo 7.6. For the microscopic analysis, cells were fixed with 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde, and the cell nucleus was stained with DAPI.

2.6. A FeCl3-Induced Carotid Arterial Thrombosis Mouse Model

All animal care and experiments in the present study were performed in strict accordance with the protocols (M006137) approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Female ICR mice were fed with a standard laboratory rodent pellet diet and supplied with water ad libitum. A FeCl3-induced carotid arterial thrombosis mouse model was used to study the targeting ability and the therapeutic efficacy of the nanoparticles. After anesthetization via continuous inhalation of isoflurane, the mouse was placed in supine position and the fur on the neck was removed. Then, the carotid artery was exposed through the middle line incision between the chin and sternum. A piece of 10% FeCl3-soaked filter paper (1 mm × 2 mm) was applied to the carotid artery for 3 min to induce the formation of arterial thrombus. The residual FeCl3 was removed by saline. During the surgery, a heating pad was used to maintain the body temperature of the mouse at 37 °C.

2.7. Thrombus Imaging

After vascular injury, the mouse was intravenously injected with Cy5-loaded nanoparticles via tail vein (n=3 per group). Fluorescence imaging of the carotid artery was performed by an in vivo imaging system (IVIS) at different time points with an excitation wavelength at 649 nm and an emission wavelength at 666 nm. For ex vivo imaging, injured and non-injured carotid arteries and major organs including heart, liver, spleen, lung, and kidney were excised after euthanasia.

2.8. Histological Examination

For in vivo antithrombotic studies, five groups of mice (n=5 per treatment group) were treated with saline, argatroban (0.4 mg/kg), PNP, NPArg, or PNPArg (dose equivalent to 0.4 mg/kg argatroban), respectively. A sham group treated with saline-soaked filter paper was also included in this study as a control. The various formulations were intravenously administrated via tail vein after the thrombosis model was built. After 24 h, the mice were euthanized and the carotid arteries were collected and subsequently embedded in optimal cutting temperature (OCT) compound. The samples were sliced into 7 μm sections and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) or dihydroethidium (DHE). H&E-stained sections were observed under an optical microscope to evaluate the antithrombotic effect. The degree of thrombosis in the carotid artery was analyzed by Image J and quantified by the blood clot area/total vascular area. For DHE staining, the collected tissue samples were incubated with 5 μM DHE at 37 °C for 30 min. After staining with DAPI, the image of tissues was captured with a fluorescence microscope.

2.9. Measurement of the Levels of TNF-α and sCD40L

A heparin-pretreated tube was used to collect the mouse blood, which was then centrifuged for 10 min at 3000 rpm to remove the blood cells (n=5 per treatment group). An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was used to measure the levels of TNF-α (R&D Systems Mouse TNF-α ELISA Kit, MTA00B) and sCD40L (Invitrogen Mouse sCD40L ELISA kit, BMS6010) in the plasma according to manufacturer’s instructions.

2.10. The tail bleeding assay

The tail bleeding assay was performed to evaluate the hemorrhagic risk of PNPArg.29 Mice (n=5 per treatment group) were intravenously injected with saline, argatroban (2 mg/kg, clinical dose), argatroban (0.4 mg/kg), or PNPArg (dose equivalent to 0.4 mg/kg argatroban), respectively. Ten minutes after the administration, the tail (5 mm away from the tail-tip) was amputated with a sharp lancet and immersed immediately in pre-warmed saline at 37 °C. The bleeding time of each mouse was recorded.

2.11. Biocompatibility

Mice were intravenously injected either with saline or PNPArg every day for a week (n=3 per group). Then, the animals were euthanized, and the major organs were collected, fixed with 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde, and embedded in OCT. The organ blocks were cut into slices with a thickness of 7 μm for H&E staining, followed by optical microscope imaging.

2.12. Statistical Analysis

Results are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Differences between the experimental groups were assessed using One-way ANOVA or t-test by GraphPad Prism software version 7.0. Significant differences between groups were indicated by *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001, respectively. p < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Preparation and characterization of the nanoparticles

To prepare the thrombus-targeting and H2O2-scavenging antithrombotic nanoparticle (i.e., PNPArg), the NPArg encapsulating argatroban was first formed via a nanoprecipitation method using PVAX and a small amount of poloxamer (25 wt% relative to PVAX). The surface of resulting NPArg was subsequently coated by platelet membrane via an extrusion process to yield PNPArg. To verify complete coating of platelet membrane on the NPArg, the variations of hydrodynamic diameter and zeta potential in NPArg and PNPArg were measured by DLS (Fig. 1B). The particle size and zeta potential of the original pristine NPArg were 138.4 ± 0.6 nm and −36.5 ± 1.1 mV, respectively. After extrusion with platelet membrane at a membrane protein to polymer weight ratio of 1:4, the hydrodynamic diameter slightly increased to 142.3 ± 2.2 nm, while the zeta potential (−37.3 ± 1.0 mV) hardly changed. This suggests that such a ratio led to incomplete coverage of platelet membranes on the NPArg surface. When the membrane protein to polymer weight ratio was increased to 1:2, the size of the PNPArg increased to 163.2 ± 3.1 nm, while the zeta potential was reduced to −30.3 ± 0.9 mV, which was similar to the zeta potential of the platelet membrane vesicle (i.e., −29.9 ± 0.8 mV). In addition, an increase of around 25 nm in diameter further indicates the complete coating of platelet membranes on NPArg.21 Therefore, a membrane protein to polymer weight ratio of 1:2 was used for all further studies. The morphology of the bare NPArg and PNPArg was characterized by TEM. PNPArg showed a spherical core-shell structure after phosphotungstic acid staining, consistent with a membrane coating around the polymeric nanocore, which is consistent with previous studies (Fig. 1C).30-31 In addition, the hydrophobicity of PVAX enables efficient encapsulation of argatroban into the PNPArg. The loading efficiency and loading content of the argatroban in PNPArg quantified by HPLC were 72% and 13.3%, respectively.

The PNPArg was designed to rapidly consume H2O2 and simultaneously release the loaded argatroban in a controlled manner at the thrombus sites. To evaluate its sensitivity to H2O2, changes of the PNPArg size in the presence of H2O2 were investigated by DLS. Rapid dissociation of the PNPArg was observed after incubation with H2O2 (100 μM) at 37 °C for 1 h because the peroxalate ester linkages in the polymer were quickly oxidized and cleaved by H2O2 (Fig. 1D). To evaluate the effect of oxidation on the drug release rate of the PNPArg, its in vitro drug release profile was studied at 37 °C with or without H2O2 (Fig. 1E). In the presence of H2O2 (100 μM), about 30% of argatroban was released from the PNPArg within the first hour and about 90% of argatroban was released within 48 h. In contrast, only about 11% of the drug was released in the media within 48 h without H2O2. Such H2O2-dependent drug release behavior further verified the H2O2 sensitivity of the PNPArg. More importantly, the H2O2-stimulated drug release behavior exhibited by the PNPArg can provide a desirable level of drug after its accumulation at the thrombus site to inhibit thrombus formation, and meanwhile reduce the risk of side effects caused by premature release of argatroban before the PNPArg reaching the target thrombus site.

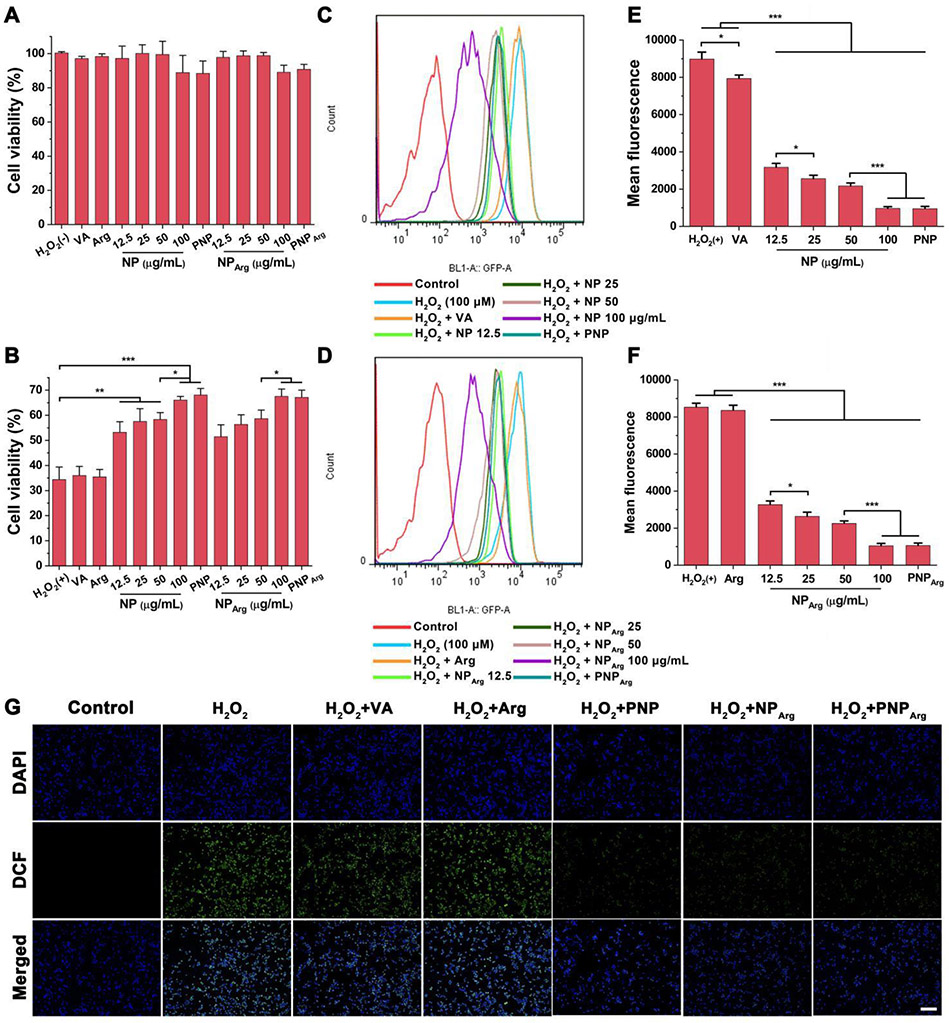

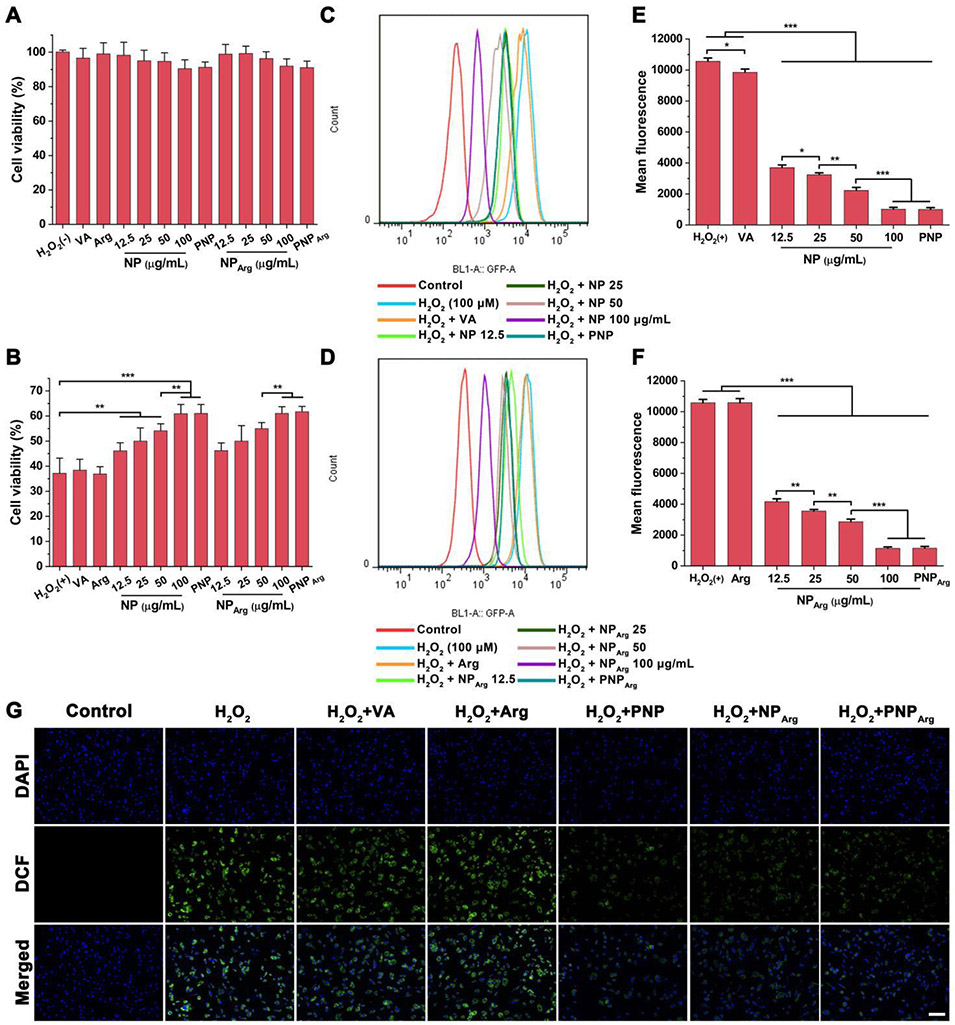

3.2. Evaluation of the biocompatibility and ROS-scavenging capability of the PNPArg in cells

The cytotoxicity of the various nanoparticle formulations and free drug was examined by the MTT assay in RAW 264.7 cells and HUVECs. No obvious cytotoxicities were observed in both types of cells for the NP and NPArg at PVAX polymer concentrations less than 100 μg/mL (Fig. 2A and Fig. 3A) compared with the control group. Moreover, the vanillyl alcohol (15 μg/mL), argatroban (29 μg/mL), PNP, and PNPArg (with the PVAX polymer concentration of 100 μg/mL) showed negligible cytotoxicity, revealing their good biocompatibility.

Fig. 2.

Anti-oxidative effects of the nanoparticles in H2O2-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells. (A) Viabilities of RAW 264.7 cells treated with the different nanoparticles and free drug (n=6). In the control group, cells were not treated by either H2O2 or nanoparticles. No statistical difference was observed compared with the normal control group. In the NP and NPArg groups, the cells were treated with the nanoparticles with 12.5, 25, 50, or 100 μg/mL of PVAX polymer. In the PNP and PNPArg group, the cells were treated with the nanoparticles with the PVAX polymer concentration of 100 μg/mL. In the vanillyl alcohol (VA) group, the cells were treated with 15 μg/mL of VA, an equivalent amount of VA in 100 μg/mL of PVAX. The concentration of argatroban (Arg) is 29 μg/mL, an equivalent amount of Arg in PNPArg. (B) Viabilities of H2O2-induced RAW 264.7 cells treated with the different formulations (n=6) as detailed in (A). (C,D) Detection of the intracellular ROS levels in H2O2-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells subjected to different treatments via flow cytometry. (E,F) Quantitative analysis of the intracellular ROS level in RAW 264.7 cells (n=3). (G) Fluorescence microscopy images of intracellular ROS in RAW 264.7 cells treated with different formulations. Cells were treated with the nanoparticles with the PVAX polymer concentration of 100 μg/mL. Blue channel: 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) stained nucleus. Green channel: dihydrodichlorofluorescein (DCF) fluorescence indicated intracellular ROS. Scale bar: 100 μm. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Fig. 3.

Anti-oxidative effects of the nanoparticles in H2O2-stimulated vascular endothelial cells. (A) Viabilities of HUVECs incubated with the different nanoparticles and free drug (n=6). In the control group, cells were not treated by either H2O2 or nanoparticles. No statistical difference was observed compared with the normal control group. In the NP and NPArg groups, the cells were treated with the nanoparticles with 12.5, 25, 50, or 100 μg/mL of PVAX polymer. In the PNP and PNPArg group, the cells were treated with the nanoparticles with the PVAX polymer concentration of 100 μg/mL. In the vanillyl alcohol (VA) group, the cells were treated with 15 μg/mL of VA, an equivalent amount of VA in 100 μg/mL of PVAX. The concentration of Arg is 29 μg/mL, an equivalent amount of Arg in PNPArg. (B) Viabilities of H2O2-induced HUVECs incubated with the different formulations (n=6) as detailed in (A). (C,D) Flow cytometry histogram of the intracellular ROS levels in H2O2-stimulated HUVECs subjected to different treatments. (E,F) Quantitative analysis of intracellular ROS level in HUVECs (n=3). (G) Fluorescence microscopy images of intracellular ROS in HUVECs subjected to different treatments. Blue channel: 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) stained nucleus. Green channel: dihydrodichlorofluorescein (DCF) fluorescence indicated intracellular ROS. Scale bar: 100 μm. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

It is known that activated platelets and injured endothelium generate high level of H2O2, which can amplify the progression of thrombus.5,8 Therefore, scavenging excessive H2O2 is a potential therapeutic approach to prevent thrombus formation. To investigate H2O2-scavenging capability of the nanoparticles, their cytotoxicity in RAW 264.7 cells and HUVECs were studied (Fig. 2B and Fig. 3B). H2O2 (100 μM) significantly decreased the cell viability in both RAW 264.7 cells (34.4%) and HUVECs (37.2%). VA (15 μg/mL) and Arg (29 μg/mL), which is equivalent to their respective amount in the PNPArg did not exhibit any significant effect on the viability of H2O2-stimulated cells. However, empty NP significantly increased cell viability in a PVAX concentration-dependent manner. In the presence of PVAX (100 μg/mL), the viability of RAW 264.7 cells and HUVECs increased to 66% and 61%, respectively, attributed to the H2O2 scavenging ability of PVAX. In addition, platelet membrane coating did not affect the H2O2 scavenging activity since PNP treated cells showed a similar cell viability as the NP treated cells. These findings demonstrated that the biomimetic nanocarriers could effectively alleviate H2O2-induced cellular injury.

We next measured the intracellular ROS level in H2O2-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells and HUVECs with the treatment of various nanoparticles. DCFH-DA, an ROS sensitive probe, was used to indicate the intracellular ROS level. DCFH-DA can be oxidized by ROS and converted to dichlorofluorescein with green fluorescence. H2O2-stimulated cells treated with the various nanoparticle formulations were stained with DCFH-DA and the intracellular fluorescence signal was quantitatively detected by flow cytometry. As shown in Fig. 2C and Fig. 2D, H2O2-stimulated cells exhibited a significantly enhanced ROS level compared with H2O2-untreated cells. Both NP and NPArg exerted strong inhibitory effects on the intracellular ROS level in a PVAX concentration-dependent manner due to the H2O2 scavenging activity of the polymer (Fig. 2E and Fig. 2F). An equivalent amount of VA slightly decreased the intracellular ROS level due to its antioxidant effect. However, free argatroban showed no antioxidant effect. As expected, the intracellular fluorescence signal was also significantly decreased with the treatment of the PNP or PNPArg. Fluorescence microscopy images further confirmed the activity of the nanoparticles in suppressing the intracellular ROS level (Fig. 2G). Moreover, similar findings were observed in HUVECs (Fig. 3A-G). Taken together, these studies indicated that the PNPArg can efficiently consume excessive H2O2, which is an important property for thrombosis therapy.

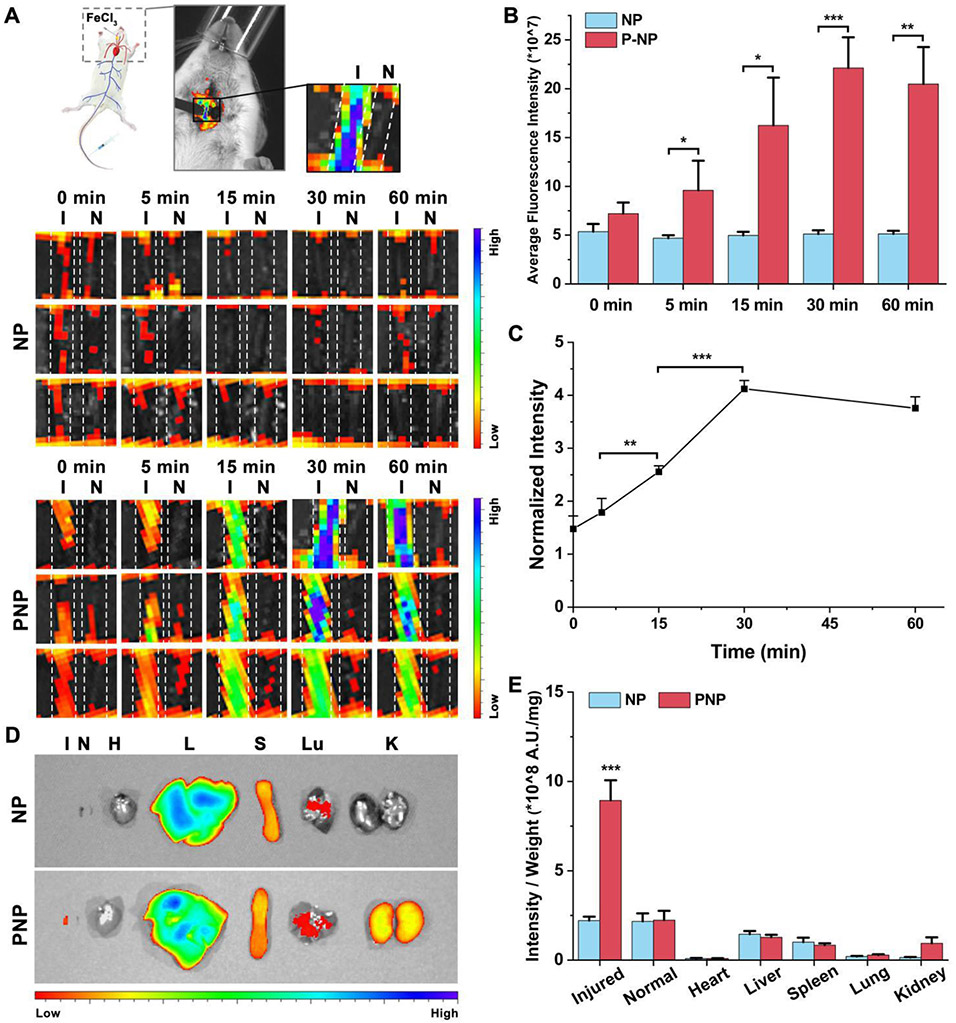

3.3. Evaluation of the thrombus-targeting ability of the PNPArg in the ferric chloride-induced carotid arterial thrombosis mouse model

The activated platelet at the thrombus site can recruit platelet membrane-coated nanoparticles.32-33 The underlying molecular mechanism is the interactions of platelet membrane with thrombus through various receptors, such as GPIIbIIIa, CD61, P-selectin, GPVI, P2Y12, and CD42b.33 Thus, active thrombus-targeting ability could be achieved by coating platelet membrane on the surface of the polymeric nanoparticles. A FeCl3-induced carotid arterial thrombosis mouse model was used to evaluate the targeting ability of the nanoparticles in this study. A filter paper soaked with FeCl3 was applied to one of the carotid arteries to stimulate the formation of thrombus. Thereafter, the Cy5-loaded NP or PNP was intravenously injected, and the fluorescence signal of the carotid arteries were captured at various time points post-injection. In the PNP-injected group, the non-injured carotid artery displayed weak fluorescence signals, indicating low PNP accumulation. In contrast, only 5 min after PNP injection, increased fluorescence signals were observed in the FeCl3-injured artery (Fig. 4A). At 30 min, the fluorescence intensity in the injured artery gradually increased due to higher PNP accumulation at the thrombus site. Thereafter, the fluorescence intensity slightly decreased as depicted in Fig. 4B and Fig. 4C. In contrast, in the uncoated NP treated group, the fluorescence signals in the injured carotid artery did not increase with time and was similar to that in the non-injured artery. At 30 min, the fluorescence signal in the injured carotid artery in the PNP group was 4 times higher compared with the NP treatment group (Fig. 4B). Then, we homogenized the carotid artery and quantified the fluorescence intensity. The PNP group showed much higher nanoparticles accumulation in the injured carotid artery than the NP group, with a more than four times increase (from 0.2 ± 0.03% injected dose for the NP group to 0.83 ± 0.08% injected dose for the PNP group). These results substantiated that platelet membrane coating is well suited for targeted delivery of antithrombotic drug to the thrombus site.

Fig. 4.

Evaluation of the thrombus-targeting ability of the nanoparticles. (A) In vivo fluorescence images of the carotid arteries treated with the Cy5-loaded NP and PNP, respectively (n=3). I and N represent the injured and non-injured carotid artery, respectively. (B) Quantification of the fluorescence intensity of the injured carotid arteries in (A) (n=3). (C) The ratio of fluorescence intensity between the injured carotid artery and non-injured carotid artery in the PNP group (n=3). (D) Distribution of the Cy5-loaded NP and PNP in the major organs and injured and non-injured carotid artery. H, L, S, Lu, K, I, and N represent heart, liver, spleen, lung, kidney, injured artery, and the non-injured artery, respectively. (E) Quantitative analysis of the mean fluorescence intensity per unit mass in different organ in the ex vivo image (n=3). ***p < 0.001 when comparing with all major organ or tissue. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Although the surface coating of platelet membrane provides the thrombus-targeting ability, the PNP also accumulated in liver and spleen due to the intrinsic detoxification function of these organs (Fig. 4D), which is a common phenomenon for nanomedicine.34-37 However, the PNP-treated injured carotid artery exhibited much higher fluorescence signal per unit mass compared with any other organs and the non-injured carotid artery, which further validates the targeting ability of the PNP to the thrombosed vessels (Fig. 4E).

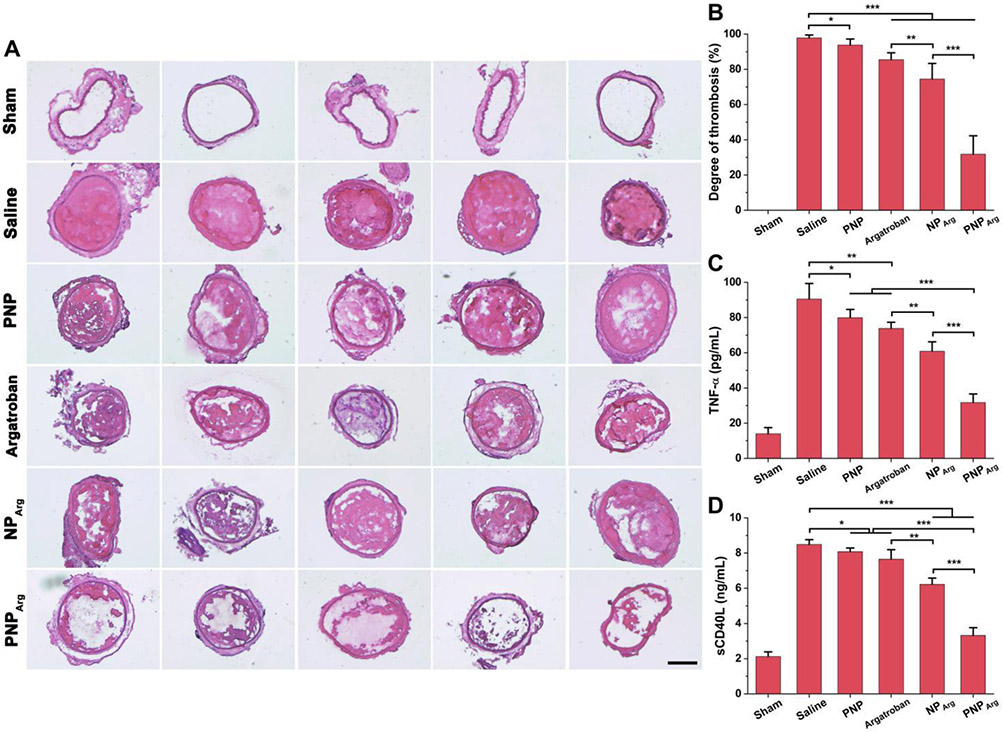

3.4. Histological examination

In general, a prominent benefit of targeted delivery is a drastic improvement on therapeutic efficacy. We next evaluated the antithrombotic efficacy of the various nanoparticle formulations and free drug in the carotid arterial thrombosis mouse model via histological examination. Immediately after the vascular damage, the NPArg, PNPArg, and PNP were intravenously administrated. The carotid artery was cut out for assay 24 h post-injection. The saline and free drug groups were used as the additional controls and the sham group is included to investigate whether the surgical procedure could cause the damage of vessel. As presented in Fig. 5A and Fig. 5B, no thrombus was observed in the carotid artery incubated with saline-soaked filter paper in the sham group, implying that the surgical procedure did not cause any vascular injury. However, a large thrombus that blocked the carotid artery was observed in FeCl3-treated mice in the saline group (97.8% thrombosis degree). Empty PNP suppressed the blood clot formation (93.8% thrombosis degree) significantly comparted with the saline group statistically, likely attributed to the antioxidant effect of PVAX. The PNPArg showed much better inhibition effect on thrombus formation (31.8% thrombosis degree) than NPArg (74.5% thrombosis degree) and the equivalent amount of free argatroban (85.5% thrombosis degree). The superior therapeutic activity of the PNPArg can be rationalized by the multifunctionalities of the biomimetic nanoparticles such as active thrombus-targeting ability, H2O2 scavenging capability, and H2O2-controlled drug release behavior at the thrombosed vessels.

Fig. 5.

Therapeutic potential of the nanoparticles in the FeCl3-induced carotid artery thrombosis mouse model. (A) H&E staining of the carotid arteries from the mice subjected to different treatments including saline, argatroban, PNP, NPArg, or PNPArg, respectively (n=5). A sham group was also included in this study as a control. In the sham group, the carotid arteries were incubated with a saline-soaked filter paper instead of FeCl3-soaked one. Scale bar: 200 μm. (B) Quantitative analysis of the degree of thrombosis (n=5). (C) The levels of TNF-α after different treatments as detected by ELISA (n=5). (D) The levels of sCD40L after different treatments (n=5). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

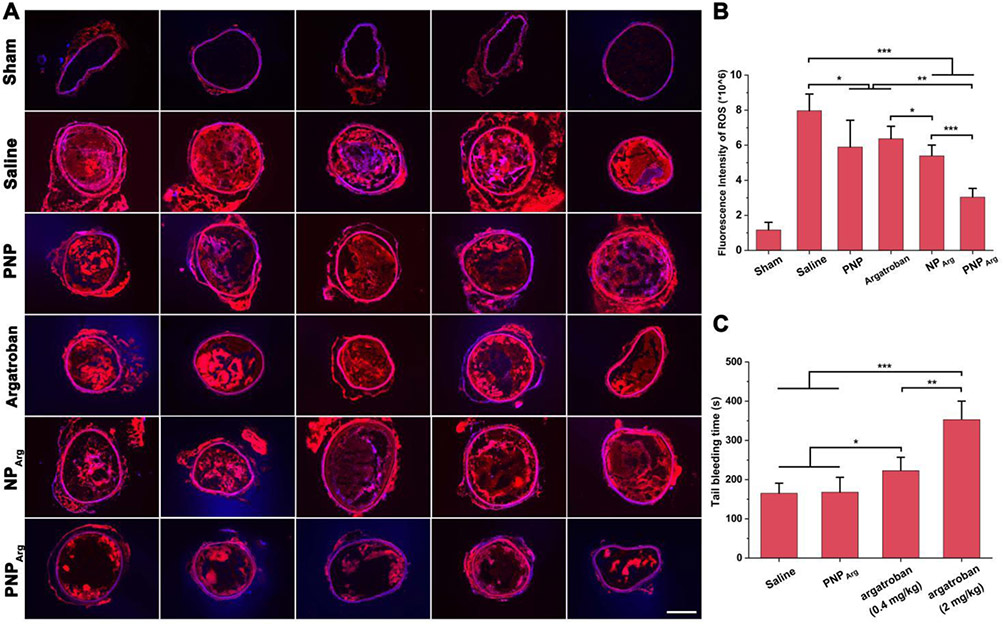

The DHE fluorescence intensity was also analyzed to evaluate the influence of the nanoparticles on the ROS level at the thrombus site. A qualitative analysis of the fluorescence intensity was carried out by fluorescence microscopy. As shown in Fig. 6, a strong DHE fluorescence signal was observed in the FeCl3-treated carotid artery, suggesting that excessive ROS was generated at the injured carotid artery site. The PNPArg remarkably reduced the ROS level in comparation with the equivalent amount of free argatroban. These results demonstrated that the PNPArg can target the thrombus and exert the combined antioxidation effect enabled by the PVAX nanocarrier and the antithrombotic effect provided by argatroban, the payload.

Fig. 6.

(A) DHE staining and (B) quantitative analysis of the fluorescence intensity of the injured carotid arteries from the mice subjected to different treatments including saline, argatroban, PNP, NPArg, or PNPArg, respectively (n=5). A sham group was also included in this study as a control. In the sham group, the carotid arteries were incubated with a saline-soaked filter paper instead of FeCl3-soaked one. Scale bar: 200 μm. (C) Tail bleeding time of mice injected with saline, argatroban (2 mg/kg), argatroban (0.4 mg/kg), or PNPArg (dose equivalent to 0.4 mg/kg argatroban), respectively (n=5). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

The TNF-α level was tested to study the anti-inflammatory effect of the nanoparticles (Fig. 5C). FeCl3 treatment remarkably increased the TNF-α level (90.5 ± 8.9 pg/mL). The PNPArg significantly decreased TNF-α level (31.7 ± 4.9 pg/mL) than PNP (79.9 ± 4.6 pg/mL), free argatroban (73.8 ± 3.5 pg/mL), and NPArg (60.9 ± 5.3 pg/mL). Activated platelets can produce sCD40L, which can interact with CD40 expressed on the surface of endothelial cells or immune cells to promote thrombus formation and inflammation.38 As shown in Fig. 5D, the level of sCD40L was elevated after FeCl3 treatment (8.5 ± 0.3 ng/mL). The PNPArg drastically reduced the level of sCD40L (3.3 ± 0.4 ng/mL) and it was much more effective than the equivalent amount of free argatroban (7.7 ± 0.5 ng/mL), PNP (8.1 ± 0.2 ng/mL), and NPArg (6.2 ± 0.4 ng/mL), suggesting that the PNPArg possess anti-oxidation, antiplatelet, and anti-inflammatory activity via the combined effect of the drug (argatroban) and the H2O2 scavenging PVAX nanovehicles.

3.5. The tail bleeding assay

The hemorrhagic risk of PNPArg was evaluated using the tail bleeding assay. As shown in Fig. 6C, compared with the saline group, administration of free argatroban at the clinical dose (2 mg/kg) significantly prolonged tail bleeding time, indicating a high risk of haemorrhage associated with argatroban due to its low specificity. Furthermore, free argatroban at 0.4 mg/kg (equivalent to the dose encapsulated in the PNPArg) also increased the bleeding time. However, PNPArg did not affect the bleeding time compared with the saline group, indicating that PNPArg not only reduced the argatroban dose needed for effective antithrombotic therapy, but also completely resolved the bleeding risk of free argatroban.

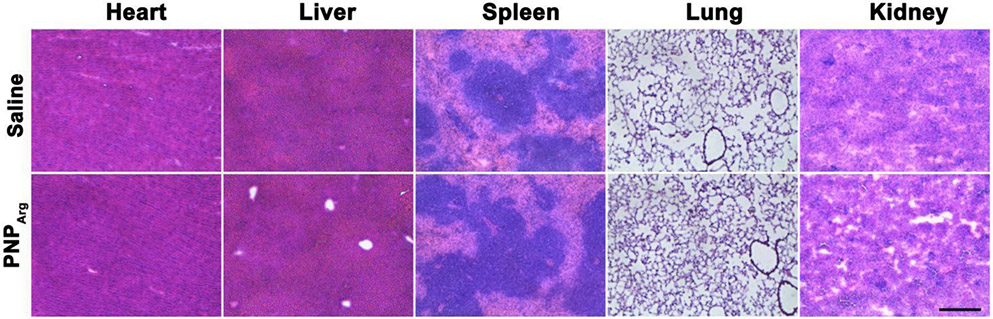

3.6. Biocompatibility

To study the in vivo biocompatibility, the mice was injected daily with PNPArg via the tail vein for one week. The major organs including heart, liver, spleen, lung, and kidney were collected and sliced for H&E staining. Compared to the saline group, no obvious pathological differences were observed in the various organs after PNPArg treatment, indicating its good in vivo biocompatibility (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Histological analysis of different organs including heart, liver, spleen, lung, and kidney from the mice subjected to daily intravenous injection of saline or the PNPArg for one week. Scale bar: 200 μm.

Notably, although PVAX has been investigated to neutralize excessive ROS and suppress inflammation, and PVAX nanoparticles could effectively deliver drugs to prevent acetaminophen-induced acute liver failure, doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy, and peripheral arterial diseases, it has not been explored in thrombus therapy.10-12 Since thrombotic disease is also associated with an elevated ROS level and inflammation, the PVAX nanoparticles could serve as effective anti-oxidative nanocarriers for antithrombotic agents to treat thrombus. Platelet membrane has been used as a cloak of nanoparticles for various disease including cancer, bacteria infection, atherosclerosis, and angioplasty-induced restenosis.39-41 In the present study, inspired by the natural thrombus homing property of platelet, platelet membrane was coated on the surface of NPArg for active thrombus-targeting. The PNPArg exhibited superior therapeutic efficacy due to its multifunctionalities including the active thrombus-targeting capability of the platelet membrane, H2O2 scavenging capability of the PVAX polymer, and the antithrombotic capability of the encapsulated drug.

4. Conclusions

A biomimetic H2O2-responsive platelet membrane-cloaked polymeric nanoparticle was developed for thrombus-targeted delivery of antithrombotic drug. The PNPArg was able to rapidly and preferentially accumulate at the platelet-rich blood clots due to the thrombus homing property of the surface coated platelet membrane. Importantly, the PNPArg significantly suppressed thrombus formation in the injured carotid artery via the combined antioxidation and antithrombotic effects. The high therapeutic efficacy achieved using the PNPArg is accompanied by good biocompatibility as evidenced by the lack of toxicity in either animal tissues or cultured cells. Collectively, this biomimetic nanocarrier holds great potential to treat various thrombotic disorders.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the financial support from the National Institute for Health (R01 HL129785 and R01 HL143469).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

References

- 1.Powers WJ, Rabinstein AA, Ackerson T, Adeoye OM, Bambakidis NC, Becker K, Biller J, Brown M, Demaerschalk BM, Hoh B, Jauch EC, Kidwell C S, Leslie-Mazwi T M, Ovbiagele B, Scott P A, Sheth K N, Southerland A M, Summers DV, Tirschwell DL,Stroke, 2019, 50(12), e344–e418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benjamin EJ, Blaha MJ, Chiuve SE, Cushman M, Das SR, Deo R, de Ferranti SD, Floyd J, Fornage M, Gillespie C, Isasi CR, Jiménez MC, Jordan LC, Judd SE, Lackland D, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth L, Liu S, Longenecker CT, Mackey RH, Matsushita K, Mozaffarian D, Mussolino ME, Nasir K, Neumar RW, Palaniappan L, Pandey DK, Thiagarajan RR, Reeves MJ, Ritchey M, Rodriguez CJ, Roth GA, Rosamond WD, Sasson C, Towfighi A, Tsao CW, Turner MB, Virani SS, Voeks JH, Willey JZ, Wilkins JT, Wu JH, Alger HM, Wong SS, Muntner P,Circulation, 2017, 135(10), e146–e603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kearon C, Akl E A, Ornelas J, Blaivas A, Jimenez D, Bounameaux H, Huisman M, King C S, Morris T A, Sood N, Stevens S M, Vintch J R E, Wells P, Woller S C, Moores C L,Chest, 2016, 149(2), 315–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krötz F, Sohn H, Pohl U,Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology, 2004, 24(11), 1988–1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Freedman JE,Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology, 2008, 28(3), s11–s16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leopold JA, Loscalzo J,Free Radical Bio. Med, 2009, 47(12), 1673–1706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dayal S, Wilson KM, Motto DG, Miller FJ, Chauhan AK, Lentz SR,Circulation, 2013, 127(12), 1308–1316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cai H,Cardiovasc. Res, 2005, 68(1), 26–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vara D, Pula G,Curr. Mol. Med, 2014, 14(9), 1103–1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ko E, Jeong D, Kim J, Park S, Khang G, Lee D,Biomaterials, 2014, 35(12), 3895–3902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park S, Yoon J, Bae S, Park M, Kang C, Ke Q, Lee D, Kang P M,Biomaterials, 2014, 35(22), 5944–5953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jung E, Noh J, Kang C, Yoo D, Song C, Lee D,Biomaterials, 2018, 179, 175–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yan H, Shao D, Lao YH, Li M, Hu H, Leong KW,Advanced Science, 2019, 6(15), 1900605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gao C, Lin Z, Jurado-Sánchez B, Lin X, Wu Z, He Q,Small, 2016, 12(30), 4056–4062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dehaini D, Wei X, Fang RH, Masson S, Angsantikul P, Luk BT, Zhang Y, Ying M, Jiang Y, Kroll AV, Gao W, Zhang L,Adv. Mater, 2017, 29(16), 1606209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang Q, Dehaini D, Zhang Y, Zhou J, Chen X, Zhang L, Fang RH, Gao W, Zhang L,Nat. Nanotechnol, 2018, 13(12), 1182–1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wei X, Zhang G, Ran D, Krishnan N, Fang RH, Gao W, Spector SA, Zhang L,Adv. Mater, 2018, 30(45), 1802233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang Y, Cai K, Li C, Guo Q, Chen Q, He X, Liu L, Zhang Y, Lu Y, Chen X, Sun T, Huang Y, Cheng J, Jiang C,Nano Lett., 2018, 18(3), 1908–1915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao Y, Xie R, Yodsanit N, Ye M, Wang Y, Gong S,Nano Today, 2020, 35, 100986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hickman DA, Pawlowski CL, Sekhon UDS, Marks J, Gupta AS,Adv. Mater, 2018, 30(4), 1700859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wei X, Ying M, Dehaini D, Su Y, Kroll AV, Zhou J, Gao W, Fang RH, Chien S, Zhang L,ACS Nano, 2018, 12(1), 109–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Song Y, Huang Z, Liu X, Pang Z, Chen J, Yang H, Zhang N, Cao Z, Liu M, Cao J, Li C, Yang X, Gong H, Qian J, Ge J,Nanomedicine: Nanotechnology, Biology and Medicine, 2019, 15(1), 13–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhao Y, Gao H, He J, Jiang C, Lu J, Zhang W, Yang H, Liu J,J. Control. Release, 2018, 283, 241–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chai Z, Hu X, Wei X, Zhan C, Lu L, Jiang K, Su B, Ruan H, Ran D, Fang R H, Zhang L, Lu W,J. Control. Release, 2017, 264, 102–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hu CJ, Fang RH, Wang K, Luk BT, Thamphiwatana S, Dehaini D, Nguyen P, Angsantikul P, Wen CH, Kroll AV, Carpenter C, Ramesh M, Qu V, Patel SH, Zhu J, Shi W, Hofman FM, Chen TC, Gao W, Zhang K, Chien S, Zhang L,Nature, 2015, 526(7571), 118–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhao Y, Jiang C, He J, Guo Q, Lu J, Yang Y, Zhang W, Liu J,Bioconjugate Chem., 2016, 28(2), 438–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pan Y, Ren X, Wang S, Li X, Luo X, Yin Z,Biomacromolecules, 2017, 18(3), 865–876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee J, Jeong L, Jung E, Ko C, Seon S, Noh J, Lee D,J. Control. Release, 2019, 304, 164–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seo J, Al-Hilal TA, Jee J, Kim Y, Kim H, Lee B, Kim S, Kim I,Nanomedicine: Nanotechnology, Biology and Medicine, 2018, 14(3), 633–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hu CJ, Zhang L, Aryal S, Cheung C, Fang RH, Zhang L,Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2011, 108(27), 10980–10985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Luk BT, Jack Hu C, Fang RH, Dehaini D, Carpenter C, Gao W, Zhang L,Nanoscale, 2014, 6(5), 2730–2737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zaldivia MTK, McFadyen JD, Lim B, Wang X, Peter K,Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine, 2017, 4, 74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu J, Zhang Y, Xu J, Liu G, Di C, Zhao X, Li X, Li Y, Pang N, Yang C, Li Y, Li B, Lu Z, Wang M, Dai K, Yan R, Li S, Nie G,Adv. Mater, 2019, 32(4), 1905145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cai M, Li B, Lin L, Huang J, An Y, Huang W, Zhou Z, Wang Y, Shuai X, Zhu K,Biomater. Sci.-UK, 2020, 8, 3485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shen M, Chang S, Liu T, Lu T, Sabu A, Chen H, Chiu H,Biomater. Sci.-UK, 2020, 8, 3885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cai Y, Xu Z, Shuai Q, Zhu F, Xu J, Gao X, Sun X,Biomater. Sci.-UK, 2020, 8, 2274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lu G, Zuo L, Zhang J, Zhu H, Zhuang W, Wei W, Xie H,Biomater. Sci.-UK, 2020, 8, 2283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lievens D, Zernecke A, Seijkens T, Soehnlein O, Beckers L, Munnix ICA, Wijnands E, Goossens P, van Kruchten R, Thevissen L, Boon L, Flavell RA, Noelle RJ, Gerdes N, Biessen EA, Daemen MJAP, Heemskerk JM, Weber C, Lutgens E,Blood, 2010, 116(20), 4317–4327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wei X, Ying M, Dehaini D, Su Y, Kroll AV, Zhou J, Gao W, Fang RH, Chien S, Zhang L,ACS Nano, 2018, 12(1), 109–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hu CJ, Fang RH, Wang K, Luk BT, Thamphiwatana S, Dehaini D, Nguyen P, Angsantikul P, Wen CH, Kroll AV, Carpenter C, Ramesh M, Qu V, Patel SH, Zhu J, Shi W, Hofman FM, Chen TC, Gao W, Zhang K, Chien S, Zhang L,Nature, 2015, 526(7571), 118–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhuang J, Gong H, Zhou J, Zhang Q, Gao W, Fang RH, Zhang L,Sci Adv, 2020, 6(13), z6108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]