Abstract

With the implementation of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), millions of low-income adults have gained health coverage. We examined the impact of the expansion on dental coverage and utilization of oral health services among low-income adults utilizing data from the National Health Interview Survey from 2010 to 2018. We found that the ACA increased rates of dental coverage by 18.9% in states that provide dental benefits in Medicaid. In terms of utilization, expansion states that provide dental benefits had the greatest increase in having a dental visit in the past year (from 44.3% to 51.4%). However, there was no significant change in the overall share of individuals who had a dental visit in the past year, though the expansion was associated with a significant increase among white adults (by 4.2 percentage points; p <0.05). The expansion was also associated with a 1.4 percentage point increase in complete teeth loss, which may be a marker of both poor oral health and potential gaining of access to dental services (with subsequent tooth extractions). Our findings suggest that in addition to expanded coverage, policies need to tackle other barriers to accessing dental care to improve population oral health.

Keywords: Dental insurance, Dental health services, The Affordable Care Act, health care disparities, National Health Interview Survey

Public health research in the United States has long documented oral care as a leading unmet health need with important implications for overall health.1, 2 Despite numerous efforts to increase access to dental care for vulnerable populations, significant disparities remain, particularly among low-income populations and racial and ethnic minorities.3–5

Since the implementation of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), nearly 20 million adults have gained health insurance 6 and there have been significant improvements in access to care and in numerous health outcomes.7–9 Although cost-related barriers have been reported to be a major contributor to avoiding dental care 10, 11, the effect of the ACA on utilization of dental services appears to be relatively small. Evidence from pre-ACA research suggest that Medicaid dental coverage improves dental utilization.12, 13 Nonetheless, few studies have examined the impact of the Medicaid expansion on access to dental care. These studies have found slight increases in access to dental care in the first few years of the ACA, particularly among childless adults, after the Medicaid expansion.14–16 However, most prior studies have not documented changes in dental coverage, which is an important intermediate outcome for assessing changes in utilization of oral health services. In a descriptive analysis, the American Dental Association estimated that the Affordable Care Act and state policy changes have increased the number of low-income adults with some form of dental coverage by about 10 million by 2017.17 Here, we build on that finding with a quasi-experimental study design and more recent data.

This study estimates the effect of Medicaid expansion under the ACA on dental coverage, access to dental care, and utilization of oral health services five years after the Medicaid expansion. We utilized the natural experiment created by the ACA implementation, using national data from 2010 to 2018, to investigate whether Medicaid expansion increased dental coverage rates and utilization among low-income adults, and if so, among which racial and ethnic groups. We also examined if those gains were greater among low-income and minority adults living in states that provide more generous adult dental benefits in Medicaid.

We hypothesized that improved access to dental care would result in increased utilization, since access to care is one of the “enabling” resources in the Andersen model of health care utilization.18 However, it’s also recognized that access alone may not suffice to increase utilization, because of other background “pre-disposing factors”, such as health literacy.

STUDY METHODS

Data & Sample

We used data from the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS).19 The NHIS is a nationally representative cross-sectional household interview survey of the civilian noninstitutionalized population of the United States. In addition to demographic and socioeconomic details, the NHIS collects information on health status, health insurance coverage, and access to care including dental visits. We analyzed data from 2010 to 2018 and obtained access to restricted state identifiers through the Federal Statistical Research Data Center.

Because states implemented the ACA at different times in 2014, we excluded year 2014 from the analysis. Our study sample included low-income adults between the ages of 19 to 64 years. The NHIS reports family income as a percentage of the federal poverty level (FPL) in 14 predefined categories (for example, below 25%, 25–49%, 50–74%, 75–99% and so on); therefore, we were not able to restrict the sample to the Medicaid eligibility threshold of adults with incomes up to 138% of FPL. Instead, our primary sample used a cutoff of family income below 125% of FPL. Additionally, we conducted a sensitivity analysis using imputed family income files provided by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) that allow us to define low-income sample based on family income up to 138% of FPL. 19 Our primary study sample included 87,393 adults.

MEASURES

Outcome variables were self-reported measures of dental coverage and access to dental care. Dental coverage measures were Medicaid, uninsured, and private dental insurance. Measures related to access to and utilization of dental services included having a dental visit in the past 12 months, inability to obtain dental care in the past 12 months because of cost, and edentulism (complete loss of all natural teeth), which is both a marker of poor oral health and potentially a marker of “improved” access to dental services for those in poor oral health, for whom complete teeth extraction and dentures may be the only viable option. All outcomes were binary indicators.

We classified a state as providing adults dental benefits in Medicaid if it offered more than emergency dental coverage to Medicaid adults in 2014.20, 21

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

To compare changes in each outcome in expansion states relative to control states before and after the expansion, we used a differences-in-differences linear regression analysis. Our estimate of interest was the interaction term between Medicaid expansion and a “Post-expansion” indicator for all years after the expansion, so that it is equal to one for expansion states when Medicaid expansion is in effect. We adjusted all models for age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, marital status, employment, citizenship, number of children, pregnancy status, state-year unemployment rate 22, number of dentists per capita in each state 23, year, and state. We also used robust standard errors clustered at state level in our regression models to account for serial autocorrelation.24

We first examined the full sample, then we repeated the analysis separately for states that provide Medicaid adult dental benefits and states without dental benefits. We also conducted subgroup analyses comparing Non-Hispanic white adults with all other race groups and adults aged 19–39 years with adults ages 40–64 years.

We conducted multiple sensitivity analyses using alternate sample definitions: excluding states that expanded Medicaid prior to 2014 (CA, CT, DC, DE, MA, MN, NJ, NY, VT, and WA), excluding pregnant women, and restricting the sample to family income below 138% of FPL using imputed family income files. A key assumption in difference-in-differences analysis is that trends in outcomes between intervention and control groups are parallel prior to the intervention. To investigate this parallel trend assumption, we compared yearly rates for each outcome between expansion and non-expansion states before Medicaid expansion. We also conducted a placebo difference-in-differences using the pre-reform period with year 2013 as the placebo ACA implementation year to formally test these trends.

We used NHIS’s survey weights to account for the complex survey design. We used Stata version 15.0 for all analyses.

LIMITATIONS

Our study has a number of limitations. First, income was reported as a categorical variable in NHIS and therefore we were not able to use the ACA’s threshold of 138% of FPL to define our study sample. Thus, there could be misclassification of Medicaid eligibility for some adults. However, we used a restrictive definition for our main eligibility sample (<125%) and conducted a sensitivity analysis using imputed family income files to limit the sample to 138% of the FPL and the results were largely similar (Appendix Exhibit A2).25

Second, NHIS questions regarding study outcomes were self-reported and therefore we cannot eliminate the potential of recall bias. However, this misclassification of outcome data is likely conservative and random across expansion and non-expansion states and therefore would bias our estimates towards the null.

Third, we defined states dental benefits based on states’ policy in year 2014. Two states, Missouri and Montana, have changed their dental benefits afterwards, but our data use agreement precludes us from identifying individual states in our analysis plan, which introduced some measurement error in the estimated effect of the expansion – but the population of the states in question is unlikely to substantially affect our results.

Fourth, our study outcomes were limited by the questions included in the NHIS. Other important outcomes not available include reasons for not pursuing dental care, self-reported dental health, and dental outcomes other than tooth loss.

Finally, although our sample size was relatively large, our estimated 95% confidence intervals were wide for several outcomes, which may suggest an inadequate statistical power to detect significant changes in our sample.

Study Results

Sample characteristics

Characteristics of the study sample at baseline (2010 to 2013) are presented in Exhibit 1. The demographic characteristics of low-income adults(n=44,753) in expansion and non-expansion states were largely similar, but non-expansion states had higher proportion of non-Hispanic black (24.9% vs. 17.5%) and US-born adults (76.3% vs. 71.3%).

Exhibit 1:

Characteristics of the Low-income Sample at Baseline, 2010 to 2013 a.

| N (Survey -Weighted Proportions) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low-Income Sample b | ||||

| Medicaid Expansion states c (n= 27,008) |

Non-Expansion states d (n= 17,745) |

|||

| Variable | ||||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 11,677 | (45.4) | 7,550 | (44.5) |

| Female | 15,331 | (54.6) | 10,195 | (55.5) |

| Mean (±SD) age, yr | 37.2 | ±14.1 | 37.04 | ±13.9 |

| Age groups | ||||

| 19–34 | 12,456 | (48.2) | 8,391 | (49.3) |

| 35–44 | 5,872 | (19.8) | 3,715 | (19.3) |

| 45–54 | 4,973 | (18.3) | 3,127 | (17.3) |

| 55–64 | 3,707 | (13.8) | 2,512 | (14.0) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Hispanic | 10,483 | (28.8) | 5,985 | (26.2) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 9,285 | (46.7) | 6,067 | (44.4) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 4,947 | (17.5) | 4,764 | (24.9) |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 1,898 | (5.4) | 645 | (3.0) |

| Non-Hispanic all other race groups | 395 | (1.6) | 284 | (1.4) |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 14,372 | (56.0) | 9,568 | (55.2) |

| Married/Partner | 12,581 | (43.7) | 8,131 | (44.5) |

| Unknown/refused | 55 | (0.2) | 46 | (0.3) |

| Citizenship | ||||

| Foreign | 7,184 | (20.3) | 3,982 | (18.1) |

| US Citizen | 19,727 | (79.3) | 13,694 | (81.6) |

| Unknown/refused | 97 | (0.3) | 69 | (0.3) |

| Nativity | ||||

| Foreign | 9,733 | (28.5) | 5,129 | (23.6) |

| US-born | 17,229 | (71.3) | 12,595 | (76.3) |

| Unknown/refused | 46 | (0.21) | 21 | (0.1) |

| Education | ||||

| Less than high school degree | 10,792 | (35.5) | 6,753 | (35.5) |

| High school graduate | 6,482 | (24.4) | 4,664 | (26.3) |

| Some college/college graduate | 9,321 | (38.8) | 6,102 | (37.0) |

| Unknown/refused | 413 | (1.3) | 226 | (1.2) |

| Employment | ||||

| Not employed | 7,789 | (30.2) | 4,940 | (28.6) |

| Currently employed | 5,825 | (22.6) | 4,152 | (23.9) |

| Unknown/refused | 13,394 | (47.2) | 8,653 | (47.5) |

SOURCE: Authors’ analysis of data from the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) from 2010 to 2013.

NOTES: SD is standard deviation. Study sample limited to adults aged 19–64 years old.

Baseline refers to the sample prior to Medicaid expansion, NHIS data from 2010 to 2013.

Low-income sample is defined as adults with income 124% below the FPL.

Medicaid expansion states: AK, AR, AZ, CA, CO, CT, DC, DE, HI, IA, IL, IN, KY, LA, MA, MD, MI, MN, MT, ND, NH, NJ, NM, NV, NY, OH, OR, PA, RI, VT, WA, WV.

Medicaid non-expansion states: AL, FL, GA, ID, KS, ME, MO, MS, NC, NE, OK, SC, SD, TN, TX, UT, VA, WI, WY.

Changes in Dental Coverage Outcomes

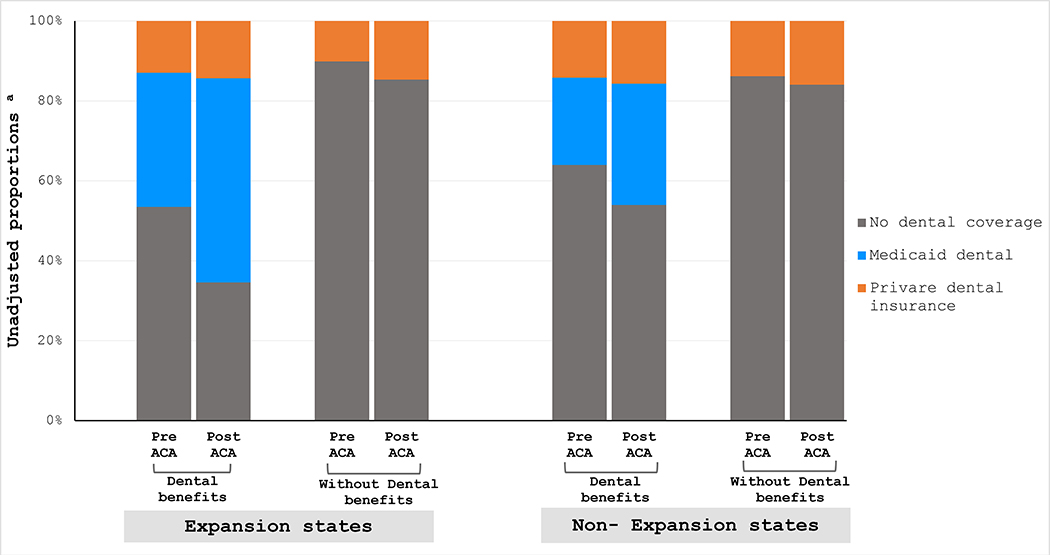

Exhibit 2 presents unadjusted changes in dental coverage outcomes in expansion and non-expansion states according to states’ dental benefits. Overall, dental coverage rates in this population are low. Prior to the ACA, less than half of low-income adults had any form of dental coverage. As expected, expansion states that provide dental benefits showed greatest gains in Medicaid dental coverage after the expansion (from 33.6% to 51.1%) and greatest reduction in the uninsured rates, a decline of 18.9% (from 53.5% to 34.6%). Meanwhile, there were small changes in private dental insurance ranging from increase of 1.5% in non-expansion states with dental benefits to 4.6% in expansion states without dental benefits. Combining Medicaid and private dental coverage, only expansion states with dental benefits in Medicaid saw dental coverage rates for low-income adults climb above 50% – up to 65.4%, while it remained under 20% in states not covering dental benefits in Medicaid (regardless of expansion status).

Exhibit 2:

Unadjusted Changes in Dental Coverage in Medicaid Expansion and Control States According to State’s Dental Benefits.

SOURCE: Authors’ analysis of data from the National Health Interview Survey from 2010-to 2018 excluding 2014.

NOTES: Study sample limited to adults aged 19–64 years old with income 124% below the FPL. Medicaid expansion states: AK, AR, AZ, CA, CO, CT, DC, DE, HI, IA, IL, IN, KY, LA, MA, MD, MI, MN, MT, ND, NH, NJ, NM, NV, NY, OH, OR, PA, RI, VT, WA, WV. Medicaid non-expansion states: AL, FL, GA, ID, KS, ME, MO, MS, NC, NE, OK, SC, SD, TN, TX, UT, VA, WI, WY. States that provide adult Medicaid dental benefits: AK, AR, CA, CO, CT, DC, IA, IL, IN, KY, MA, MI, MN, NC, ND, NE, NJ, NM, NY, OH, OR, PA, RI, SC, SD, VT, WA, WI,WY. States without adult Medicaid dental benefits: AL, AZ, DE, FL, GA, HI, ID, KS, LA, MD, ME, MO, MS, MT, NH, NV, OK, TN, TX, UT, VA, WV. a Unadjusted survey-weighted proportions.

Results from difference-in-differences analysis (Exhibit 3) for the full sample showed that when comparing expansion states to control states, Medicaid expansion was associated with a significant increase in Medicaid dental coverage (13.5 percentage points; 95% CI 7.5, 19.4), a minor decrease in the private insurance (−0.4 percentage points; 95% CI −2.3, 1.5), and a significant decline in the uninsured rate (−12.2 percentage points; 95% CI −17.9, −6.4). When examining changes in coverage outcomes according to states’ dental benefits, changes in Medicaid dental coverage were increased by 9.1 percentage points in states that provide dental benefits (95% CI 0.1, 18.1) and the decline in the uninsured rate was larger in states that provide dental benefits (−8.3 percentage points; 95% CI −18.0, 1.3) compared to states without dental benefits (−0.1 percentage points; 95% CI −3.1, 2.9).

Exhibit 3:

Changes in Insurance Coverage and Access to Dental Care Measures Among Low-Income Adults.

| Differences-in-Differences Net change after expansion |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline a | |||

| Outcome | Mean % in expansion states | Unadjusted Estimate | Adjusted Estimate b |

| % | % | % | |

| Medicaid Dental Coverage | |||

| Full sample | 29.3 | 13.1 **** | 13.5 **** |

| States with dental benefits | 33.6 | 8.7 * | 9.1 ** |

| States without dental benefits | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Private dental insurance | |||

| Full sample | 14.3 | 0.4 | −0.4 |

| States with dental benefits | 14.9 | 0.8 | 0.3 |

| States without dental benefits | 10.1 | 0.9 | 0.1 |

| No dental coverage | |||

| Full sample | 58.0 | −12.6 **** | −12.2 **** |

| States with dental benefits | 53.5 | −8.5 * | −8.3 * |

| States without dental benefits | 89.9 | −0.9 | −0.1 |

| Seen a dentist in the past year | |||

| Full sample | 43.4 | 2.2 | 2.0 |

| States with dental benefits | 44.3 | 0.8 | 1.1 |

| States without dental benefits | 36.3 | −0.2 | −1.4 |

| Couldn’t afford dental care in the past year | |||

| Full sample | 28.4 | −1.9 | −1.8 |

| States with dental benefits | 27.7 | 0.0 | −0.1 |

| States without dental benefits | 33.6 | 0.7 | 0.6 |

| Complete teeth loss | |||

| Full sample | 7.0 | 1.4 * | 1.5 ** |

| States with dental benefits | 6.7 | −0.5 | −0.5 |

| States without dental benefits | 9.4 | 1.3 | 1.4 |

SOURCE: Authors’ analysis of data from the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) from 2010 to 2018 excluding 2014.

NOTES: Study sample limited to adults aged 19–64 years old with income 124% below the FPL. Medicaid expansion states: AK, AR, AZ, CA, CO, CT, DC, DE, HI, IA, IL, IN, KY, LA, MA, MD, MI, MN, MT, ND, NH, NJ, NM, NV, NY, OH, OR, PA, RI, VT, WA, WV. Medicaid non-expansion states: AL, FL, GA, ID, KS, ME, MO, MS, NC, NE, OK, SC, SD, TN, TX, UT, VA, WI, WY. States that provide adult Medicaid dental benefits: AK, AR, CA, CO, CT, DC, IA, IL, IN, KY, MA, MI, MN, NC, ND, NE, NJ, NM, NY, OH, OR, PA, RI, SC, SD, VT, WA, WI,WY. States without adult Medicaid dental benefits: AL, AZ, DE, FL, GA, HI, ID, KS, LA, MD, ME, MO, MS, MT, NH, NV, OK, TN, TX, UT, VA, WV.

Baseline refers to the sample prior to Medicaid expansion (NHIS data from 2010 to 2013).

Model adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, marital status, employment, citizenship, number of children, pregnancy status, state-year unemployment rate, number of dentists per capita in each state, year, and state. All Analyses used robust standard errors clustered by state.

p<0.1

p<0.05

p<0.001.

In the subgroup analyses, changes in health coverage by race/ethnicity and age groups were generally similar to the full sample (Exhibit 4). However, minorities and older adults had greater gains in Medicaid dental coverage (non-whites: 13.9 percentage points; 95% CI, 6.5, 21.2, older adults: 16.5 percentage points; 95% CI, 9.7,23.2), and a larger decline in the uninsured rate (non-whites: −12.9 percentage points; 95% CI, −19.3, −6.4, older adults: −14.2 percentage points; 95% CI, −20.5, −7.9). Older adults also demonstrated a slight significant decline in private dental insurance (−1.8 percentage points; 95% CI, −3.6, −0.1).

Exhibit 4:

Changes in Insurance Coverage and Access to Dental Care Outcomes Among Low-Income Adults According to Race and Age Groups.

| Baseline a | Differences-in-Differences Net change after expansion | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean % in expansion states | Unadjusted Estimate | Adjusted Estimate b | |

| Outcome | % | % | % |

| Medicaid dental coverage | |||

| Race | |||

| White population | 28.5 | 12.6 **** | 12.7 **** |

| Non-Whites | 30.0 | 13.4 *** | 13.9 **** |

| Age | |||

| 19–39 yr | 27.3 | 10.7 *** | 11.2 **** |

| 40–64 yr | 32.3 | 16.1 **** | 16.5 **** |

| Private dental insurance | |||

| Race | |||

| White population | 18.5 | −0.2 | −0.6 |

| Non-Whites | 10.6 | 0.6 | −0.1 |

| Age | |||

| 19–39 yr | 17.1 | 1.7 | 0.6 |

| 40–64 yr | 10.4 | −1.6 | −1.8 ** |

| No dental coverage | |||

| Race | |||

| White population | 54.3 | −11.5 **** | −11.3 **** |

| Non-Whites | 61.3 | −13.1 **** | −12.9 **** |

| Age | |||

| 19–39 yr | 57.3 | −11.1 *** | −10.6 *** |

| 40–64 yr | 59.1 | −14.1 **** | −14.2 **** |

| Seen a dentist in the past year | |||

| Race | |||

| White population | 45.7 | 3.8 * | 4.2 ** |

| Non-Whites | 41.3 | 1.4 | 1.2 |

| Age | |||

| 19–39 yr | 46.7 | 1.7 | 1.3 |

| 40–64 yr | 38.5 | 2.7 | 2.6 |

| Couldn’t afford dental care in the past year | |||

| Race | |||

| White population | 29.4 | −2.4 | −2.3 |

| Non-Whites | 27.5 | −2.0 | −1.7 |

| Age | |||

| 19–39 yr | 25.1 | −3.2 * | −2.8 |

| 40–64 yr | 33.2 | −0.3 | −0.3 |

| Complete teeth loss | |||

| Race | |||

| White population | 9.9 | 2.3 | 2.3 |

| Non-Whites | 4.4 | 0.7 | 0.9 |

| Age | |||

| 19–39 yr | 2.5 | 0.7 | 0.8 |

| 40–64 yr | 13.5 | 2.3 | 2.3 * |

SOURCE: Authors’ analysis of data from the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) from 2010 to 2018 excluding 2014.

NOTES: Study sample limited to adults aged 19–64 years old with income 124% below the FPL. Non-white group includes Hispanic, non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic Asian, and non-Hispanic all other race groups. Medicaid expansion states: AK, AR, AZ, CA, CO, CT, DC, DE, HI, IA, IL, IN, KY, LA, MA, MD, MI, MN, MT, ND, NH, NJ, NM, NV, NY, OH, OR, PA, RI, VT, WA, WV. Medicaid non-expansion states: AL, FL, GA, ID, KS, ME, MO, MS, NC, NE, OK, SC, SD, TN, TX, UT, VA, WI, WY.

Baseline refers to the sample prior to Medicaid expansion (NHIS data from 2010 to 2013).

Model adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, marital status, employment, citizenship, number of children, pregnancy status, state-year unemployment rate, number of dentists per capita in each state, year, and state. All analyses used robust standard errors clustered by state.

p<0.1

p<0.05

p<0.01

p<0.001.

Changes in access to dental care outcomes

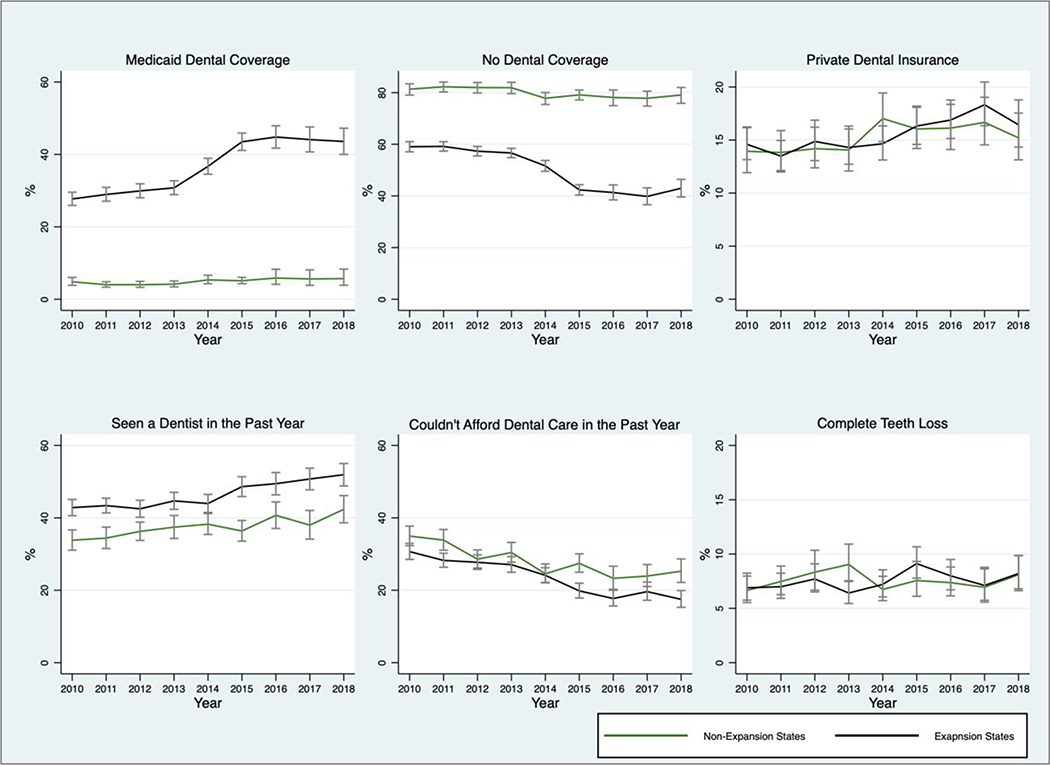

Unadjusted changes (Appendix Exhibit A1)25 in access to dental care measures showed that after the expansion, expansion states that provide dental benefits had the greatest increase in having a dental visit in the past 12 months (from 44.3% to 51.4%) and the largest decline in the proportion of the sample reporting inability to obtain dental care in the past 12 months because of cost (from 27.7% to 17.6%). States that provide dental benefits, both expansion and non-expansion, demonstrated larger changes in the rates of individuals with complete teeth loss compared to states without dental benefits, indicating increased access to dental services. There was 1.6% increase in complete teeth loss in non-expansion states with dental benefits and 1.2% increase in expansion states with dental benefits.

Medicaid expansion was associated with a non-significant increase in having a dental visit in the past 12 months (2.0 percentage points; 95% CI, −0.7, 4.8) and a non-significant decrease in the inability to obtain dental care in the past 12 months because of cost (−1.8 percentage points; 95% CI, −5.2, 1.7). These changes remained non-significant when we repeated the analysis according to states’ dental benefits (Exhibit 3). However, in the full sample, the expansion was associated with a 1.5 percentage points increase in complete teeth loss (95% CI, 0.0, 2.9).

The race/ethnicity subgroup analyses (Exhibit 4) showed similar findings to the main analysis except for having a dental visit in the past 12 months for white adults; the expansion was associated with an increase of 4.2 percentage points (95% CI, 0.8,7.6). We found no significant changes in any of the access to dental care measures in the age subgroup analysis.

Sensitivity analyses

Results from the sensitivity analyses were similar to our main findings (Appendix Exhibit A2).25 The Medicaid expansion was associated with a significant increase in Medicaid dental coverage and a decline in the uninsured rate when excluding early expansion states, using alternative percentage of the FPL to define the sample, or excluding pregnant women. However, changes in complete teeth loss were only marginally significant (p<0.10) when we excluded pregnant women and when restricting the sample to family income below 138% of FPL using imputed family income.

Unadjusted trends in outcomes according to Medicaid expansion status are presented in Appendix Exhibit A3.25 The yearly trends prior to ACA implementation did not show any marked divergence by expansion status before 2014. These pre-expansion trends were not perfectly parallel for private dental insurance and complete teeth loss. However, results from our placebo test (Appendix Exhibit A4)25 provide support for our difference in differences design. In the placebo analysis, there were no significant changes in any of the dental coverage outcomes and two of the access to dental care outcomes demonstrated a reduction with significant placebo coefficients: dental visit in the past 12 months in dental benefit states and complete teeth loss in the full sample.

Discussion

In this study, we used national survey data and a quasi-experimental design to estimate the causal impact of Medicaid expansion on changes in dental coverage and dental care utilization among low-income adults five years after the expansion. We found that the ACA was associated with significant increases in dental coverage (largely concentrated in states covering dental care in Medicaid) as well as a decline in the uninsured rate. The expansion was also associated with significant increase in complete teeth loss among low-income adults as a whole and in having dental visits in the past year among white adults only.

Our study provides new evidence on the effects of the ACA expansion on changes in dental coverage. In this analysis, we assessed the impact of the ACA on Medicaid coverage, uninsured rates, and private dental insurance among low-income adults using most recent national data. We found that Medicaid expansion was associated with improvements in having dental coverage, a change that is largely driven by Medicaid expansion in states that provide dental benefits, and reduction in the uninsured rates. Notably, rates of dental coverage in this population remain quite low in most states, with more than 80% of low-income adults in states without Medicaid dental benefits having any form of dental coverage.

We did not find consistent evidence to support our hypothesis that gains in dental coverage would increase access to and improve utilization of dental care after the Medicaid expansion. While our point estimates suggest modest improvements in seeing a dentist in the past year and a decline in the inability to afford dental care after the expansion, these changes were not statistically significant. We offer several possible explanations for these findings. First, although evidence from previous studies demonstrated slight improvements in utilization among low-income adults, these studies examined the impact of the ACA in the first few years after the expansion using different data sources.14–16 Our study assessed the long-term effect of the ACA on dental utilization five years after the implementation of the policy. Nevertheless, our 95% confidence intervals included the point estimates from those studies.

Also, despite that in the full sample we did not detect significant changes in seeing a dentist in the past year, we found that Medicaid expansion was associated with an increase in having a dental visit among Non-Hispanic white adults. This suggest that besides coverage, there could be other persistent barriers to utilization of dental services, particularly among minorities. Based on Andersen’s behavioral model of health care utilization, race & socioeconomic status are “pre-disposing factors” for healthcare utilization.18 Therefore, simply expanding access to insurance may not be sufficient to boost utilization. Health literacy is another “pre-disposing factor” that is a strong predictor for utilization.26 Prior research indicated that Medicaid adults with high health literacy demonstrated improved access to dental care after the ACA.27 We were unable to account for health literacy in this analysis since the NHIS does not collect this information.

Furthermore, the healthcare environment is an “enabling factor” influencing utilization in Andersen’s model. The capacity of the dental workforce to sustain the demand of the Medicaid population has been reported to be a major concern for access to dental care. Dentists’ willingness to participate in Medicaid is a key challenge to Medicaid programs and to access to care. 28–31 Although some states have increased Medicaid reimbursement rates to improve dentists’ participation, 32 the ACA expansion did not include any provisions to enhance dental providers’ participation. Therefore, low-income adults, despite having dental coverage, may be experiencing greater challenges in finding dental providers who accept and are available to treat them.

Our findings concern the key issue of whether states provide adults with dental benefits in Medicaid, which unlike dental benefits for children in Medicaid is a state option. Evidence from prior research suggests that a large proportion of Medicaid enrollees are confused about their coverage and whether it includes benefits such as dental care.33 Confusion or lack of awareness of Medicaid dental benefits may lead some enrollees not to utilize them.

Although in our analysis we did not detect significant differences in utilization of dental services after the expansion between states that provide dental benefits and state without benefits, states providing dental benefits showed increase in dental visits and a decline in the inability to obtain dental care. This suggests that states coverage of adults’ dental benefits could play a role in improving dental care utilization.

Our findings concerning complete teeth loss suggest improved access to dental services; however, this may be an unintended consequence of the ACA expansion. As growing numbers of low-income adults have gained access to dental services after the expansion, many are likely presenting to clinics in a state of neglected oral health, which often leaves dental extraction as the only affordable treatment option. Assuring routine access to preventive oral health services could therefore improve low-income population oral health and prevent teeth loss.

Conclusion

While the Medicaid expansion improved rates of dental coverage, particularly in states covering dental services in Medicaid, our findings suggest that there are other persistent barriers to access to dental care, particularly among racial and ethnic minorities. Findings from our study can inform future policies to consider additional measures to improve dental care utilization among low-income adults including but not limited to insurance coverage for oral health care.

Acknowledgments

Funding Information:National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (K99MD012253)

Appendix Exhibit A1:

Unadjusted Changes in in Access to Dental Care Outcomes in Expansion and Control States According to State’s Dental Benefits.

SOURCE: Authors’ analysis of data from the National Health Interview Survey from 2010 to 2018 excluding 2014.

NOTES: Study sample limited to adults aged 19–64 years old with income 124% below the FPL. Medicaid expansion states: AK, AR, AZ, CA, CO, CT, DC, DE, HI, IA, IL, IN, KY, LA, MA, MD, MI, MN, MT, ND, NH, NJ, NM, NV, NY, OH, OR, PA, RI, VT, WA, WV. Medicaid non-expansion states: AL, FL, GA, ID, KS, ME, MO, MS, NC, NE, OK, SC, SD, TN, TX, UT, VA, WI, WY. States that provide adult Medicaid dental benefits: AK, AR, CA, CO, CT, DC, IA, IL, IN, KY, MA, MI, MN, NC, ND, NE, NJ, NM, NY, OH, OR, PA, RI, SC, SD, VT, WA, WI, WY. States without adult Medicaid dental benefits: AL, AZ, DE, FL, GA, HI, ID, KS, LA, MD, ME, MO, MS, MT, NH, NV, OK, TN, TX, UT, VA, WV. a Unadjusted survey-weighted proportions.

Appendix Exhibit A2:

Sensitivity Analyses

| Differences-in-Differences Adjusted Estimates Net Change After Expansion |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Excluding early expansion states a |

Using alternative FPL cutoff b |

Excluding pregnant women |

||||

| Outcome | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI |

| Medicaid dental coverage | ||||||

| Full sample | 11.2 | (6.6,15.8)** | 13.6 | (7.8,19.4)** | 13.6 | (7.6,19.6)** |

| States with dental benefits | 8.6 | (0.4,16.7)* | 8.9 | (0.8,16.9)* | 9.1 | (0.0,18.1)* |

| States without dental benefits | 0 | (-,-) | 0 | (-,-) | 0 | (-,-) |

| Private dental insurance | ||||||

| Full sample | −0.1 | (−2.7, 2.5) | −2.0 | (−3.7,−0.3)* | −0.4 | (−2.3,1.6) |

| States with dental benefits | 0.7 | (−3.2,4.6) | −2.6 | (−4.4,−0.7)** | 0.3 | (−2.7,3.2) |

| States without dental benefits | 0.0 | (−3.0,3.0) | −0.4 | (−2.5,1.8) | 0.1 | (−3.0,3.1) |

| No dental coverage | ||||||

| Full sample | −10.6 | (−15.7,−5.5)** | −10.8 | (−16.6,−5.0)** | −12.3 | (−18.1,−6.5)** |

| States with dental benefits | −8.6 | (−18.0,0.8) | −5.4 | (−13.8,3.1) | −8.4 | (−18.0,1.3) |

| States without dental benefits | 0.0 | (−3.0,3.0) | 0.4 | (−1.8,2.5) | −0.1 | (−3.1, 3.0) |

| Seen a dentist in the past year | ||||||

| Full sample | 0.8 | (−2.1,3.8) | 2.5 | (−0.5,5.5) | 2.2 | (0.5,4.9) |

| States with dental benefits | 0.2 | (−3.9,4.3) | 0.5 | (−2.9,3.9) | 1.4 | (−2.6, 5.5) |

| States without dental benefits | −1.3 | (−6.4,3.9) | −0.9 | (−5.7,3.9) | −0.8 | (−5.9,4.4) |

| Couldn’t afford dental care in the past year | ||||||

| Full sample | −0.1 | (−2.9,2.7) | −2.5 | (−6.1,1.1) | −1.6 | (−4.9,1.8) |

| States with dental benefits | 1.6 | (−3.2,6.3) | −2.0 | (−5.5,1.6) | 0.1 | (−4.9,5.0) |

| States without dental benefits | 0.1 | (−3.7,4.0) | 1.9 | (−2.1,5.9) | 0.6 | (−3.4,4.6) |

| Complete teeth loss | ||||||

| Full sample | 1.8 | (0.2,3.5)* | 1.6 | (−0.1,3.3) | 1.4 | (0.0,2.9) |

| States with dental benefits | 0.1 | (−1.6,1.7) | −2.1 | (−4.9,0.7) | −0.6 | (−2.1, 0.9) |

| States without dental benefits | 1.4 | (−2.1,4.8) | 2.0 | (−0.5,4.4) | 1.4 | (−2.0,4.7) |

SOURCE: Authors’ analysis of data from the National Health Interview Survey from 2010 to 2018 excluding 2014.

NOTES: Study sample limited to adults aged 19–64 years old with income 124% below the FPL.

Excluding states that expanded Medicaid prior to 2014(CA, CT, DC, DE, MA, MN, NJ, NY, VT, WA).

Study sample limited to adults aged 19–64 years old with family income up to 138% of FPL using imputed family income files provided by the National Center for Health Statistics. Results presented are using one of the five imputations files. Medicaid expansion states: AK, AR, AZ, CA, CO, CT, DC, DE, HI, IA, IL, IN, KY, LA, MA, MD, MI, MN, MT, ND, NH, NJ, NM, NV, NY, OH, OR, PA, RI, VT, WA, WV. Medicaid non-expansion states: AL, FL, GA, ID, KS, ME, MO, MS, NC, NE, OK, SC, SD, TN, TX, UT, VA, WI, WY. States that provide adult Medicaid dental benefits: AK, AR, CA, CO, CT, DC, IA, IL, IN, KY, MA, MI, MN, NC, ND, NE, NJ, NM, NY, OH, OR, PA, RI, SC, SD, VT, WA, WI, WY. States without adult Medicaid dental benefits: AL, AZ, DE, FL, GA, HI, ID, KS, LA, MD, ME, MO, MS, MT, NH, NV, OK, TN, TX, UT, VA, WV. Model adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, marital status, employment, citizenship, number of children, pregnancy status, state-year unemployment rate, number of dentists per capita in each state, year, and state. All analyses used robust standard errors clustered by state. CI= confidence interval.

P<0.05

P<0.01

Appendix Exhibit A3:

Unadjusted Trends in Insurance Coverage and Access to Dental Care Measures According to Medicaid Expansion Status.

SOURCE: Authors’ analysis of data from the National Health Interview Survey from 2010-to 2018.

NOTES: Medicaid expansion states: AK, AR, AZ, CA, CO, CT, DC, DE, HI, IA, IL, IN, KY, LA, MA, MD, MI, MN, MT, ND, NH, NJ, NM, NV, NY, OH, OR, PA, RI, VT, WA, WV. Medicaid non-expansion states: AL, FL, GA, ID, KS, ME, MO, MS, NC, NE, OK, SC, SD, TN, TX, UT, VA, WI, WY. Study sample limited to adults aged 19–64 years old with income 124% below the FPL. All estimates are unadjusted survey-weighted proportions. Bars represents 95% confidence interval.

Appendix Exhibit A4:

Robustness Checks

| Differences-in-Differences Net change after expansion |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo expansion a | ||||

| Unadjusted Estimate |

Adjusted Estimate |

|||

| Outcome | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI |

| Medicaid dental coverage | ||||

| Full sample | 1.0 | (−1.6,3.5) | 1.1 | (−1.5,3.7) |

| States with dental benefits | 0.2 | (−6.9,7.2) | −0.7 | (−7.9,6.6) |

| States without dental benefits | 0 | (-,-) | 0 | (-,-) |

| Private dental insurance | ||||

| Full sample | 0.1 | (−2.3, 2.4) | 0.4 | (−1.8,2.6) |

| States with dental benefits | −0.1 | (−3.6, 3.5) | 0.7 | (−2.5,3.8) |

| States without dental benefits | −1.7 | (−5.2, 1.8) | −1.6 | (−5.1,2.0) |

| No dental coverage | ||||

| Full sample | −1.1 | (−4.4, 2.3) | −1.6 | (−5.0,1.9) |

| States with dental benefits | −0.2 | (−5.3,4.9) | −0.1 | (−5.4,5.2) |

| States without dental benefits | 1.7 | (−1.8,5.2) | 1.6 | (−2.0,5.1) |

| Seen a dentist in the past year | ||||

| Full sample | −0.6 | (−4.1,2.9) | 0.0 | (−3.2,3.3) |

| States with dental benefits | −6.2 | (−12.2, −0.3)* | −5.9 | (−11.0,−0.9)* |

| States without dental benefits | 1.2 | (−4.3,6.6) | 1.6 | (−3.3,6.5) |

| Couldn’t afford dental care in the past year | ||||

| Full sample | 0.4 | (−2.8, 3.6) | 0.5 | (−2.7,3.7) |

| States with dental benefits | 3.5 | (−3.9, 11.0) | 4.1 | (−3.3, 11.4) |

| States without dental benefits | −3.8 | (−11.3, 3.6) | −3.3 | (−11.4,4.8) |

| Complete teeth loss | ||||

| Full sample | −2.5 | (−4.5, −0.5)* | −2.5 | (−4.5,−0.5)* |

| States with dental benefits | −3.8 | (−9.6, 2.0) | −3.4 | (−8.5,1.6) |

| States without dental benefits | −1.8 | (−5.6, 1.9) | −1.4 | (−5.2,2.5) |

SOURCE: Authors’ analysis of data from the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) from 2010 to 2018 excluding 2014.

NOTES: Study sample limited to adults aged 19–64 years old with income 124% below the FPL.

Placebo expansion using NHIS data from 2010 to 2013 and year 2013 as the ACA implementation year. Medicaid expansion states: AK, AR, AZ, CA, CO, CT, DC, DE, HI, IA, IL, IN, KY, LA, MA, MD, MI, MN, MT, ND, NH, NJ, NM, NV, NY, OH, OR, PA, RI, VT, WA, WV. Medicaid non-expansion states: AL, FL, GA, ID, KS, ME, MO, MS, NC, NE, OK, SC, SD, TN, TX, UT, VA, WI, WY. States that provide adult Medicaid dental benefits: AK, AR, CA, CO, CT, DC, IA, IL, IN, KY, MA, MI, MN, NC, ND, NE, NJ, NM, NY, OH, OR, PA, RI, SC, SD, VT, WA, WI,WY. States without adult Medicaid dental benefits: AL, AZ, DE, FL, GA, HI, ID, KS, LA, MD, ME, MO, MS, MT, NH, NV, OK, TN, TX, UT, VA, WV. Model adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, marital status, employment, citizenship, number of children, pregnancy status, state-year unemployment rate, number of dentists per capita in each state, year, and state. All analyses used robust standard errors clustered by state. CI= confidence interval.

P<0.05

P<0.01.

Appendix Methods:

Regression Equation - Differences in Differences Model (Exhibit 3, Exhibit 4, and Appendix Exhibit A2)

| Equation (1) |

Yist is an indicator whether an individual i had a dental visit in the past 12 months in state s at time t. Yeart is an indicator variable for time t being after the policy change, States is an indicator variable for exposure group s, Xist represents individual level covariates and εist is the error term. Yeart is equal to one if the observation occurs after the policy change. State s is equal to one if the observation is in a state that changes its policy and equal to zero in a state that doesn’t change its policy. β1 and β2 are vectors of time and state fixed effects respectively. Year fixed effects control for any secular trends in the outcome that are common across states. State fixed effects control for any unmeasured differences between states. The coefficient of interest is β3 that represents the change in dental utilization after expansion among those in Medicaid expansion states, compared to those living in states without the expansion. The model controls for Medicaid eligibility variables and other individual covariates as Xist including: age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, marital status, employment, citizenship, number of children, pregnancy status, state-year unemployment rate, and number of dentists per capita in each state. Models used robust standard errors clustered at the state level.

We repeated the same regression model in Equation 1 for all study outcomes: Medicaid, uninsured, private dental insurance, couldn’t afford dental care in the past year, and complete teeth loss.

Regression Equation - Differences in Differences Model (Appendix Exhibit A4)

| Equation (2) |

We used the same model as Equation 1 except that for the placebo expansion we used NHIS data from 2010 to 2013 and year 2013 as the ACA implementation year.

Contributor Information

Hawazin W. Elani, Department of Oral Health Policy and Epidemiology at the Harvard School of Dental Medicine and a research associate in the Department of Health Policy and Management at the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, all in Boston. Massachusetts..

Benjamin D. Sommers, Health Care Economics in the Department of Health Policy and Management, Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, and a professor of medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, all in Boston, Massachusetts..

Ichiro Kawachi, Social Epidemiology in the Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences at the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health..

References

- 1.Murthy VH. Oral Health in America, 2000 to Present: Progress made, but Challenges Remain. Public Health Rep. 2016;131(2):224–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Osborn R, Squires D, Doty MM, Sarnak DO, Schneider EC. In New Survey Of Eleven Countries, US Adults Still Struggle With Access To And Affordability Of Health Care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(12):2327–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cunha-Cruz J, Hujoel PP, Nadanovsky P. Secular trends in socioeconomic disparities in edentulism: USA, 1972–2001. J Dent Res. 2007;86(2):131–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mejia GC, Elani HW, Harper S, Murray Thomson W, Ju X, Kawachi I, et al. Socioeconomic status, oral health and dental disease in Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United States. BMC Oral Health. 2018;18(1):176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gupta N, Vujicic M, Yarbrough C, Harrison B. Disparities in untreated caries among children and adults in the U.S., 2011–2014. BMC Oral Health. 2018;18(1):30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The Uninsured and the ACA: A Primer - Key Facts about Health Insurance and the Uninsured amidst Changes to the Affordable Care Act: Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF); 2019. [cited 2020 Jan 18]. Available from: https://www.kff.org/report-section/the-uninsured-and-the-aca-a-primer-key-facts-about-health-insurance-and-the-uninsured-amidst-changes-to-the-affordable-care-act-how-many-people-are-uninsured/. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Allen H, Sommers BD. Medicaid Expansion and Health: Assessing the Evidence After 5 Years. JAMA. 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sommers BD, Blendon RJ, Orav EJ, Epstein AM. Changes in Utilization and Health Among Low-Income Adults After Medicaid Expansion or Expanded Private Insurance. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2016;176(10):1501–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sommers BD, Maylone B, Blendon RJ, Orav EJ, Epstein AM. Three-Year Impacts Of The Affordable Care Act: Improved Medical Care And Health Among Low-Income Adults. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(6):1119–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vujicic M, Buchmueller T, Klein R. Dental Care Presents The Highest Level Of Financial Barriers, Compared To Other Types Of Health Care Services. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(12):2176–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gupta N, Vujicic M. Main Barriers to Getting Needed Dental Care All Relate to Affordability: Health Policy Institute. American Dental Association; 2019. [cited 2020 Jan 18]. Available from: https://www.ada.org/~/media/ADA/Science%20and%20Research/HPI/Files/HPIBrief_0419_1.pdf?la=en. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choi MK. The impact of Medicaid insurance coverage on dental service use. Journal of Health Economics. 2011;30(5):1020–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Decker SL, Lipton BJ. Do Medicaid benefit expansions have teeth? The effect of Medicaid adult dental coverage on the use of dental services and oral health. Journal of Health Economics. 2015;44:212–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nasseh K, Vujicic M. Early Impact of the Affordable Care Act’s Medicaid Expansion on Dental Care Use. Health Services Research. 2017;52(6):2256–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singhal A, Damiano P, Sabik L. Medicaid Adult Dental Benefits Increase Use Of Dental Care, But Impact Of Expansion On Dental Services Use Was Mixed. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(4):723–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nasseh K, Vujicic M. The impact of the affordable care act’s Medicaid expansion on dental care use through 2016. J Public Health Dent. 2017;77(4):290–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Medicaid Expansion and Dental Benefits Coverage: Health Policy Institute. American Dental Association; 2018. [cited 2020 April 30]. Available from: https://www.ada.org/~/media/ADA/Science%20and%20Research/HPI/Files/HPIgraphic_1218_3.pdf?la=en. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Andersen RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? J Health Soc Behav. 1995;36(1):1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Center for Health Statistics. National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) Public Use Data Release. Hyattsville, MD: CDC/ National Center for Health Statistics.[cited 2020 Jan 18]. Available from: ftp://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/Health_Statistics/NCHS/Dataset_Documentation/NHIS/. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hinton E, Paradise J. Access to Dental Care in Medicaid: Spotlight on Nonelderly Adults.: The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF); 2016. Updated April 27,2016. [cited 2020 Jan 19]. Available from: http://kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/access-to-dental-care-in-medicaid-spotlight-on-nonelderly-adults/. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Medicaid State Plan Amendments: Medicaid.gov; [cited 2020 Jan 18]. Available from: https://www.medicaid.gov/state-resource-center/medicaid-state-plan-amendments/index.html.

- 22.Local Area Unemployment Statistics. Washington, DC: Bureau of Labor Statistics; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Supply of Dentists in the U.S.: 2001–2018: Health Policy Institute. American Dental Association; 2019. [cited 2020 Jan 18]. Available from: https://www.ada.org/en/science-research/health-policy-institute/data-center/supply-and-profile-of-dentists. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bertrand M, Duflo E, Mullainathan S. How Much Should We Trust Differences-in-Differences Estimates? The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 2004;119:249–75. [Google Scholar]

- 25.To access the Appendix, click on the Appendix link in the box to the right of the article online.

- 26.Paasche-Orlow MK, Wolf MS. The causal pathways linking health literacy to health outcomes. Am J Health Behav. 2007;31 Suppl 1:S19–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kino S, Kawachi I. Can Health Literacy Boost Health Services Utilization in the Context of Expanded Access to Health Insurance? Health Educ Behav. 2019:1090198119875998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coverage of Medicaid Dental Benefits for Adults. The Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission; 2015. p. 24–53. [cited 2020 Jan 22]. Available from: https://www.macpac.gov/publication/coverage-of-medicaid-dental-benefits-for-adults-3/

- 29.Mediciad:States Made Multiple Program Changes, and Beneficiaries Generally Reported Access Comparable to Private Insurance. United States Government Accountability Office. GAO-13–55. 2012. [cited 2020 Jan 22]. Available from: http://www.gao.gov/assets/650/649788.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Warder CJ, Edelstein BL. Evaluating levels of dentist participation in Medicaid: A complicated endeavor. J Am Dent Assoc. 2017;148(1):26–32.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Logan HL, Catalanotto F, Guo Y, Marks J, Dharamsi S. Barriers to Medicaid participation among Florida dentists. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2015;26(1):154–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nasseh K, Vujicic M. The Impact of Medicaid Reform on Children’s Dental Care Utilization in Connecticut, Maryland, and Texas. Health Services Research. 2015;50(4):1236–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Allen H, Wright BJ, Baicker K. New medicaid enrollees in Oregon report health care successes and challenges. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(2):292–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]