Abstract

We herein describe the case of a 38-year-old patient with congenital agammaglobulinemia who presented with community-acquired pneumonia; acute respiratory failure with sepsis ensued requiring ICU admission, mechanical ventilation and vasopressors administration. The causative organism was identified as Acinetobacter calcoaceticus, sensitive to multiple agents. Stewardship was effectively applied; clinical, biologic and radiologic improvement resulted, and the patient was later discharged on ciprofloxacin therapy; improvement being maintained thereafter. This is the first reported case of community-acquired Acinetobacter pneumonia in our region.

Keywords: Acinetobacter calcoaceticus, agammaglobulinemia, antibiotic sensitivity, community-acquired, pneumonia

Introduction

Acinetobacter species are becoming a major cause of nosocomial infections, including hospital-acquired and ventilator-associated pneumonia [1]. However, Acinetobacter calcoaceticus as a causative organism of community-acquired pneumonia has rarely been described in the literature; we hereby report the case of a Lebanese patient with agammaglobulinaemia who had community-acquired A. calcoaceticus pneumonia.

Case report

A 38-year-old male patient with confirmed agammaglobulinaemia had not been compliant with the monthly therapeutic immunoglobulin administration. He presented to the emergency department with worsening dyspnoea, productive cough and a recent fever. He was tachycardic, tachypnoeic, febrile with a body temperature of 38.7°C, blood pressure of 78/51 mmHg and oxygen saturation of 85% on ambient air. He was immediately placed on a non-rebreather facial mask and started on aggressive fluid resuscitation.

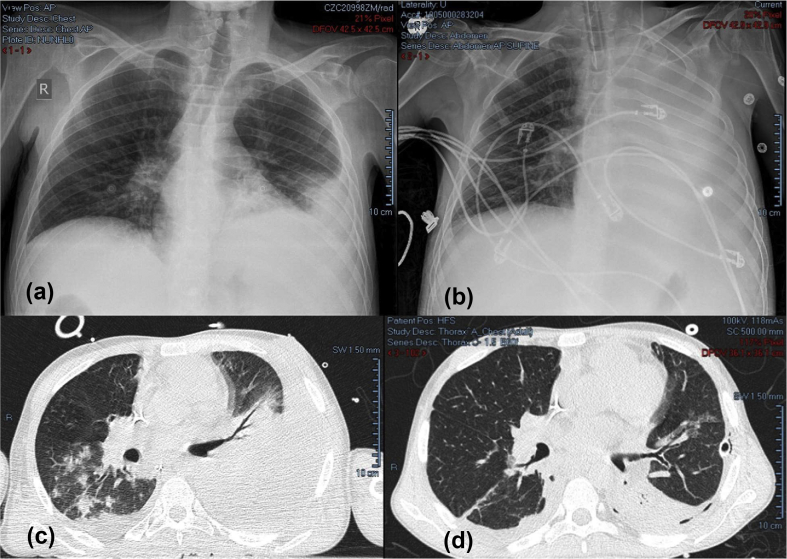

A chest X-ray revealed infiltrates in the left lower lobe associated with mild left pleural effusion (Fig. 1a). Community-acquired pneumonia with septic shock was diagnosed; ceftriaxone and clarithromycin were subsequently initiated. Laboratory test results are shown in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

(a) Initial chest X-ray: left lower infiltrates and a mild pleural effusion. (b) Chest X-ray on clinical deterioration: opacification of the left hemithorax and increased left pleural effusion. (c) Chest CT on day 2 of admission: homogeneous density with air bronchogram in the left upper and lower lobes. (d) Left pleural effusion and consolidation of the posterior segment of the left lower lobe.

Table 1.

Laboratory data

| Variable | On presentation | Reference range, Adults |

|---|---|---|

| Haematocrit (%) | 38.5 | 36–46 |

| Haemoglobin (g/dL) | 11.9 | 12–16 |

| White cell count (per μL) | 9050 | 4500–11 000 |

| Differential count (%) | ||

| Neutrophils | 88.9 | 40–70 |

| Lymphocytes | 8.4 | 22–44 |

| Monocytes | 2.0 | 4–11 |

| Eosinophils | 0.5 | 0–8 |

| Basophils | 0.1 | 0–3 |

| Platelet count (per μL) | 92 000 | 150 000–400 000 |

| Red cell count (per μL) | 5 450 000 | 4 000 000–5 900 000 |

| Mean corpuscular volume (fL) | 70.7 | 80–100 |

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 135 | 135–145 |

| Potassium (mmol/L) | 4.2 | 3.4–5.0 |

| Chloride (mmol/L) | 102 | 98–108 |

| Carbon dioxide (mmol/L) | 20 | 23–32 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 35 | 3.3–5.0 |

| Calcium (mg/L) | 83 | 88–102 |

| Phosphorus (mg/L) | 25 | 25–45 |

| Magnesium (mg/L) | 12 | 17–25 |

| Alanine aminotransferase (UI/L) | 39 | 16–63 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (UI/L) | 42 | 10–50 |

| Prothrombin time | ||

| Patient time | 15.8 | |

| % | 69 | 79%–120% |

| International normalized ratio | 1.48 | <1.2 |

| Thromboplastin time | ||

| Patient time | 40 | |

| Ratio | 1.35 | <1.2 |

| Lactic acid (mmol/L) | 2.1 | 0.5–2.2 |

| Procalcitonin (ng/mL) | 0.33 | 0–0.5 |

| C-reactive protein (ng/mL) | 44.3 | 0–9 |

| B-type natriuretic peptide (pg/mL) | 136 | 0–129 |

With an initial arterial oxygen pressure of 65 mmHg, persistent hypoxaemia and worsening respiratory distress, the patient was transferred to the intensive care unit, sedated, intubated and ventilated. Another chest X-ray showed increasing left pleural effusion (Fig. 1b), a chest tube was inserted on the left side, and the drained fluid was compatible with empyema. As a result of persistent hypotension, norepinephrine was started; haemodynamic stability was restored hours later, and urine output was improving gradually. Once stability had been achieved, a CT scan of the thorax showed homogeneous density with air bronchogram in the left upper lobe, involving mainly the lingula and part of the left lower lobe (Fig. 1c). Gram stain of sputum revealed Gram-negative bacilli, and aerobic blood cultures grew Gram-negative coccobacilli, later identified as A. calcoaceticus. This bacterium was particularly sensitive to a broad spectrum of antibiotics including ceftazidime, cefepime, colistin, tigecycline, meropenem, piperacillin, cotrimoxazole and ciprofloxacin. Testing for influenza viruses A and B was negative, along with the urinary antigens of pneumococcus and Legionella.

Intravenous immunoglobulins were administered on day 1, as several monthly infusions were missed for the treatment of his primary immunodeficiency. C-reactive protein and procalcitonin peaked at 271 mg/L and 16.22 ng/mL, respectively, on day 2 of presentation, and the initial antibiotic regimen was replaced by colistin and cefepime. The patient's condition improved gradually: intravenous pressors were stopped, he was weaned off mechanical ventilation and was later extubated. Imaging showed minimal left pleural effusion (Fig. 1d). The chest tube was removed, and colistin and cefepime were thereafter replaced with ciprofloxacin. Two weeks following his admission, the patient was discharged on ciprofloxacin for an additional 2 weeks, and he was able to maintain his clinical stability.

Discussion

Community-acquired pneumonia is one of the most common acute infections requiring admission to hospital [2]. Streptococcus pneumoniae is still the single most common defined pathogen in nearly all studies of hospitalized adults with community-acquired pneumonia [3]. Other bacteria commonly encountered are Haemophilus influenzae, Staphylococcus aureus and Gram-negative bacilli, beside the ‘atypical agents’ such as Legionella, Mycoplasma pneumoniae and Chlamydia pneumoniae. However, community-acquired pneumonia due to Acinetobacter species is rare and has been mostly reported from Southeast Asia and Australia during wet seasons [4,5].

Agammaglobulinaemia is a rare form of primary immune deficiency characterized by the absence of circulating B cells and low serum levels of all immunoglobulin classes. Affected patients are particularly susceptible to infections, frequently severe ones [6]. Our patient had congenital agammaglobulinaemia and had not been receiving immunoglobulin infusions for several months, placing him at high risk of acquiring infections with atypical organisms, Acinetobacter being a potential one.

Acinetobacter species are a heterogeneous group of ubiquitous, encapsulated, aerobic, non-motile Gram-negative bacteria that are widespread in the environment [7]. Community-acquired infections due to Acinetobacter spp. are rare, and described respiratory infections are limited to those acquired in health-care facilities, where the organism has become more resistant to the first-line agents such as quinolones, aminoglycosides, cephalosporins and antipseudomonal penicillins [8]. The Acinetobacter identified in our case was susceptible to various antimicrobials, further supporting the fact that the infection was not contracted in a nosocomial context. Also, invasive infections are produced by the susceptible strains rather than resistant strains [9].

Our patient had concomitant severe sepsis, not responsive to fluid resuscitation, requiring admission to the intensive care unit and vasopressor administration. The patient's pneumonia and accompanying pleural effusion abruptly caused the hypoxic respiratory failure to worsen, necessitating intubation and invasive ventilation. Empiric antibiotics were started upon presentation, and once the growth of cultures was obtained and the causative organism and its antibiogram had been identified, stewardship was applied; antibiotics were substituted to those to which the bacterium was susceptible. The patient improved clinically, justifying vasopressor discontinuation and, later, extubation. Laboratory tests improved, and repeat chest X-rays showed process limited to the left lower lobe.

Patients with community-acquired pneumonia are treated for a minimum of 5 days; extended courses may be needed for immunocompromised patients, patients with infections caused by certain pathogens (Pseudomonas aeruginosa), or those with complications [10]. The patient was discharged with monotherapy consisting of ciprofloxacin 500 mg/per day to be continued for a total of 4 weeks of antibiotic therapy. Improvement was maintained, as demonstrated at regular follow ups.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first reported case of community-acquired Acinetobacter pneumonia in Lebanon and the Middle East.

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Hartzell J.D., Kim A.S., Kortepeter M.G., Moran K.A. Acinetobacter pneumonia: a review. Medscape Gen Med. 2007;9:4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Community-acquired pneumonia. RCP J. 2020 https://www.rcpjournals.org/content/clinmedicine/12/6/538 [Internet] (cited 27 August 2020). Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartlett J.G., Mundy L.M. Community-acquired pneumonia. Mass Med Soc. 2009 doi: 10.1056/NEJM199512143332408. https://www.nejm.org/doi/10.1056/NEJM199512143332408 [Internet] (cited 27 August 2020). Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen M.Z., Hsueh P.R., Lee L.N., Yu C.J., Yang P.C., Luh K.T. Severe community-acquired pneumonia due to Acinetobacter baumannii. Chest. 2001;120:1072–1077. doi: 10.1378/chest.120.4.1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anstey N.M., Currie B.J., Hassell M., Palmer D., Dwyer B., Seifert H. Community-acquired bacteremic Acinetobacter pneumonia in tropical Australia is caused by diverse strains of Acinetobacter baumannii, with carriage in the throat in at-risk groups. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:685–686. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.2.685-686.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Almasaudi SB. cinetobacter spp. as nosocomial pathogens: Epidemiology and resistance features. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2018;Mar;25(3):586–596. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2016.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wroblewska M.M., Rudnicka J., Marchel H., Luczak M. Multidrug-resistant bacteria isolated from patients hospitalised in Intensive Care Units. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2006;27:285–289. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2005.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Michalopoulos A., Falagas M.E. Treatment of Acinetobacter infections. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2010;11:779–788. doi: 10.1517/14656561003596350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tien N., You B.-J., Chang H.-L., Lin H.-S., Lee C.-Y., Chung T.-C. Comparison of genospecies and antimicrobial resistance profiles of isolates in the Acinetobacter calcoaceticus–Acinetobacter baumannii complex from various clinical specimens. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:6267–6271. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01304-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Overview of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. UpToDate. 2020 https://ezproxy.usj.edu.lb:4555/contents/overview-of-community-acquired-pneumonia-in-adults?search=community/acquired/pneumonia&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1∼150&usage_type=default&display_rank=1 [Internet]. (cited 16 April 2020). Available from: [Google Scholar]