Abstract

Objective

The aim of this study was to evaluate the respiratory and physical function of patients who retested positive for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) RNA during post-coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) rehabilitation.

Methods

A total of 302 discharged COVID-19 patients were included. Discharged patients were followed up for 14 days to 6 months. The modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) dyspnea scale, Borg rating of perceived exertion, and manual muscle testing (MMT) scores on day 14 and at 6 months after discharge were compared between the redetectable positive (RP) and non-RP (NRP) groups. Prognoses of respiratory and physical function were compared between patients who recovered from moderate and severe COVID-19.

Results

Of the study patients, 7.6% were RP. The proportion of patients who used antiviral drugs was significantly lower in the RP group than in the NRP group. There were no differences in mMRC, Borg, or MMT scores within the RP and NRP groups. The mMRC, Borg, and MMT scores were worse for patients with severe disease when compared to those with moderate disease at both follow-up time points.

Conclusions

COVID-19 patients who did not take antiviral drugs were more likely to be RP after discharge. The recovery of respiratory and physical function was not related to re-positivity during rehabilitation, but was related to disease severity during hospitalization.

Keywords: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, Redetectable positive, Respiratory function, Physical function, Rehabilitation

Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic is a major global public health event. COVID-19 is caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). As of April 4, 2021, a total of 131 487 572 confirmed cases of COVID-19 worldwide, including 2 857 702 deaths, had been reported to the World Health Organization (WHO) (WHO, 2021). Significant progress has been made in the treatment of COVID-19, and a large number of patients have been cured and discharged.

Some recent studies have successively reported that SARS-CoV-2 may be redetected by reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR) during post-COVID-19 rehabilitation (Du et al., 2020, Kang, 2020, Mei et al., 2020, Zheng et al., 2020). The proportion of re-positive patients has ranged from 2.4% to 69.2% (Du et al., 2020), and the redetectable positive (RP) results have been reported to last from 1 to 38 days after discharge (Mei et al., 2020). Most RP patients have been asymptomatic or have had mild symptoms; however, some patients have progressed to a severe condition and died (Gousseff et al., 2020). At present, the characteristics of RP patients are not well understood. Moreover, there is no report on the prognosis of respiratory and physical functions in RP patients. The aim of this study was to explore the characteristics of respiratory and physical dysfunction in RP patients.

Subjects and methods

Study subjects

A total of 302 patients with confirmed COVID-19 who were discharged from Tianjin Haihe Hospital between January 21, 2020 and January 11, 2021 were recruited. Of the 156 non-local patients who had returned to their home country by 6 months after discharge, 12 were lost to follow-up and two died. A total of 132 patients were followed up for 6 months. All enrolled patients met the diagnostic criteria, clinical classification, and discharge criteria outlined by the Chinese Clinical Guidance for COVID-19 Pneumonia Diagnosis and Treatment published by the China National Health Commission (Shen et al., 2020). The criteria for diagnosis were as follows: suspected case with one of the following etiological or serological factors: (1) positive real-time fluorescence RT-PCR detection of SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid; (2) virus gene sequencing, highly homologous with the known SARS-CoV-2; (3) The new coronavirus-specific IgG antibody changes from negative to positive or the IgG antibody titer in the recovery phase is 4 times or more higher than that in the acute phase.

The criteria for patient discharge were as follows: (1) a normal body temperature for more than 3 days, (2) respiratory symptoms had been significantly relieved, (3) acute exudative lesions on chest computed tomography (CT) scan had resolved, and (4) two consecutive respiratory specimens (specimens collected at least 24 h apart) were negative for SARS-CoV-2 RNA by RT-PCR. All discharged patients continued to quarantine and were observed for 14 days. The discharged patients were followed up every week. SARS-CoV-2 RNA testing was performed at each follow-up. Patients who were RP for SARS-CoV-2 RNA were readmitted for further medical observation.

For this study, the patients were divided into RP and non-RP (NRP) groups according to their SARS-CoV-2 RNA RT-PCR results during rehabilitation. They were also further subdivided into groups according to the severity of the disease during their hospitalization: moderate and severe groups. Moderate-type disease was defined as cases in which symptoms such as fever and respiratory tract symptoms were present and manifestations of pneumonia could be seen on imaging. Patients who met any of the following criteria were classified as having severe-type disease: (1) dyspnea, respiratory rate ≥33 breaths/min; (2) in resting state, finger oxygen saturation ≤93%; (3) arterial blood partial pressure of oxygen/fraction of inspired oxygen ≤300 mmHg (1 mmHg = 0.133 kPa); and (4) lung imaging showing that the lesion had progressed significantly, by more than 50% within 24–48 h.

The exclusion criteria were patients who (1) died before the follow-up, (2) refused to participate in the follow-up, and (3) left the local area and could not complete the follow-up.

Data collection

Basic data collection

Each patient’s, sex, age, comorbidities, use of antiviral drugs, and modified Medical Research Council (mMRC), Borg, and manual muscle test (MMT) scores were collected through a combination of questionnaires and a review of the electronic medical records.

SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR test

Nasal, throat, anal, and stool swabs were collected, and SARS-CoV-2 RNA RT-PCR tests were conducted at the Tianjin Center for Disease Control.

Assessment of respiratory function

Dyspnea was assessed with the mMRC dyspnea scale, which is used in many respiratory diseases (Casanova et al., 2015). The mMRC scale used in this study was graded as follows: grade 0, difficulty breathing only during strenuous exercise; grade 1, dyspnea when walking fast on flat ground or walking on small slopes; grade 2, due to dyspnea, the patient is slower than peers or needs to stop and rest when walking on flat ground; grade 3, the patient needs to stop and rest after walking about 100 meters or a few minutes on flat ground; and grade 4, the patient cannot leave the house due to severe breathing difficulties or has difficulty breathing while getting dressed and undressed.

Assessment of physical function

The Borg scale is a valuable non-invasive test for the prediction of muscle weakness in patients (Just et al., 2010). The Borg rating of perceived exertion was used in this study: 0 points, no dyspnea or fatigue at all; 0.5 points, very slight dyspnea or fatigue, almost imperceptible; 1 point, very slight dyspnea or fatigue; 2 points, mild dyspnea or fatigue; 3 points, moderate dyspnea or fatigue; 4 points, slightly severe dyspnea or fatigue; 5 points, severe dyspnea or fatigue; 6–8 points, very severe dyspnea or fatigue; 9 points, extremely severe dyspnea or fatigue; and 10 points, excessive dyspnea or fatigue, reaching the limit. Physical function can be assessed readily through MMT (Lee et al., 2012). MMT was used to assess the muscle strength of the upper (biceps (elbow flexion), triceps (elbow extension)) and lower (iliopsoas (hip flexion), quadriceps (knee extension), tibialis anterior (ankle dorsiflexion)) left and right limbs. The patient’s condition was evaluated based on fatigue and physical strength.

Ethical approval statement

The present study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Tianjin Haihe Hospital (2020HHKT-023). Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants

Statistical methods

IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was used for the statistical analysis. Numerical data are presented as the number of cases (%), and the comparison of rates was performed by Chi-square test. Measurement data with a skewed distribution are presented as the median and interquartile range (IQR, 25th percentile, 75th percentile), and the Mann–Whitney U-test was used for comparison between groups. P < 0.05 indicated statistical significance.

Results

Patient enrollment process and basic data

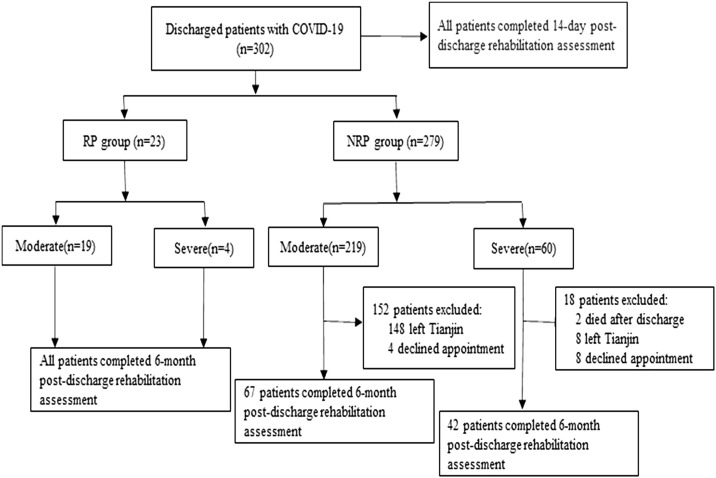

The case data of a total of 302 patients with COVID-19 were collected in this study. Of these patients, 23 were in the RP group (19 with moderate disease and four with severe disease) and 279 were in the NRP group (219 with moderate disease and 60 with severe disease). In total, 302 patients completed the mMRC, Borg, and MMT assessments on day 14 after discharge and 132 patients completed the assessments at 6 months after discharge (Figure 1 ).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of patients with COVID-19 discharged from hospital in this study. RP, redetectable positive; NRP, non-redetectable positive.

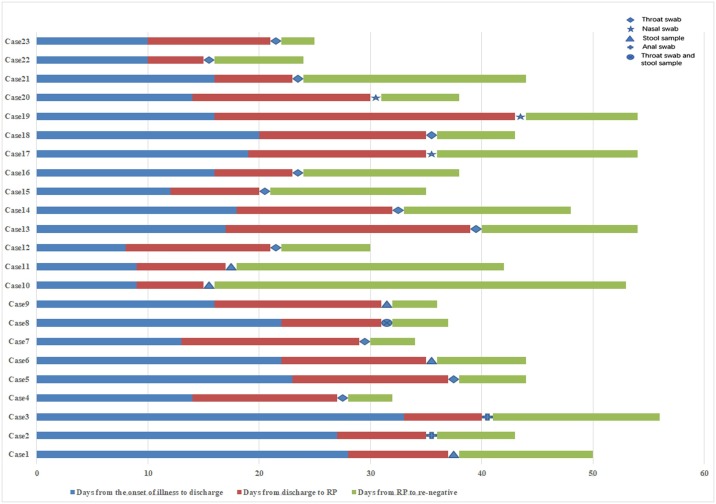

The condition of specimens and the dynamic changes in nucleic acid tests in the RP group

Among the 23 patients who retested positive, 12 were positive for throat swabs, five for nucleic acid in stool samples, three for nasal swabs, two for anal swabs, and one for a throat swab and nucleic acid in a stool sample at the same time. The average time between the positive retest result and the time of discharge was 11.61 days. The average time for nucleic acid to turn negative again after the positive retest result was 11.48 days (range 3–37 days) (Figure 2 ).

Figure 2.

Dynamic profile of intermittent negative status of redetectable positive (RP) patients.

Comparison of clinical characteristics between the RP and NRP group patients

There was no significant difference between the two groups of patients in terms of sex, disease type, and comorbidities. The median age in the RP group was 35 years (IQR 27–48 years), which was lower than that in the NRP group at 41 years (IQR 27–54 years) (Table 1). In further detail (Table 2 ), the percentage of severe cases within the age group >60 years was 40.6% (26/64), which was much higher than that in the age group <60 years at 7.1% (17/238). The proportion of patients using antiviral drugs in the RP group was significantly lower than that in the NRP group (Table 1). In the moderate-type disease group, the proportion of RP patients using antiviral drugs was lower than that of the NRP patients. However, in the severe-type disease group, there was no difference in the proportion of patients using antiviral drugs between the RP and NRP groups (Table 2).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of redetectable positive (RP) and non-redetectable positive (NRP) patients.

| Characteristics | RP (n = 23) | NRP (n = 279) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 35 (27–48) | 41 (27–54) | 0.195 |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.289 | ||

| Male | 15 (65.2%) | 150 (53.8%) | |

| Female | 8 (34.8%) | 129 (46.2%) | |

| Type, n (%) | 0.843 | ||

| Moderate | 19 (82.6%) | 219 (78.5%) | |

| Severe | 4 (17.4%) | 60 (21.5%) | |

| Antiviral therapya, n (%) | 0.015 | ||

| Yes | 18 (78.3%) | 259 (92.83%) | |

| No | 5 (21.7%) | 16 (5.73%) | |

| Missing | 0 (0%) | 4 (1.43%) | |

| Comorbidity, n (%) | 0.823 | ||

| Yes | 6 (26.1%) | 67 (24.0%) | |

| No | 17 (73.9%) | 212 (76.0%) |

IQR, interquartile range.

Antiviral drugs included arbidol, lopinavir, ritonavir, oseltamivir, darunavir cobistat, and favipiravir.

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of patients with moderate and severe disease.

| Characteristics | Moderate (n = 238) |

Severe (n = 64) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RP (n = 19) | NRP (n = 219) | P-value | RP (n = 4) | NRP (n = 60) | P-value | |

| Age (years), n (%) | 0.325 | 0.923 | ||||

| ≤14 | 2 (10.5%) | 9 (4.1%) | 0 | 0 | ||

| 15–59 | 17 (89.5%) | 193 (88.1%) | 2 (50.0%) | 36 (60.0%) | ||

| ≥60 | 0 | 17 (7.8%) | 2 (50.0%) | 24 (40.0%) | ||

| Sex, n (%) | 0.208 | 1.000 | 1.000 | |||

| Male | 13 (68.4%) | 117 (53.4%) | 2 (50.0%) | 33 (55.0%) | ||

| Female | 6 (31.6%) | 102 (46.6%) | 2 (50.0%) | 27 (45.0%) | ||

| Antiviral therapya, n (%) | 0.013 | 1.000 | ||||

| Yes | 14 (73.7%) | 201 (91.8%) | 4 (100%) | 58 (96.6%) | ||

| No | 5 (26.3%) | 15 (6.8%) | 0 | 1 (1.7%) | ||

| Missing | 0 | 3 (1.4%) | 0 | 1 (1.7%) | ||

| Comorbidity, n (%) | 0.886 | 1.000 | ||||

| Yes | 4 (21.1%) | 37 (16.9%) | 2 (50.0%) | 30 (50.0%) | ||

| No | 15 (78.9%) | 182 (83.1%) | 2 (50.0%) | 30 (50.0%) | ||

RP, redetectable positive; NRP, non-redetectable positive.

Antiviral drugs included arbidol, lopinavir, ritonavir, oseltamivir, darunavir cobistat, and favipiravir.

Evaluation of respiratory and physical function of COVID-19 patients on day 14 after discharge

This study showed that on day 14 after discharge, the mMRC, Borg, and MMT scores of patients in the severe-type disease group were worse than those of the patients in the moderate-type disease group (Table 3 ). There were no differences in mMRC, Borg, and MMT scores between the RP and NRP groups (Table 4 ). Further stratified comparison showed no differences in the mMRC, Borg, and MMT scores between patients who had recovered from moderate-type COVID-19 and severe-type COVID-19 in the RP group. However, the mMRC, Borg, and MMT scores for the patients who had recovered from severe-type COVID-19 were worse in the NRP group (Table 5 ).

Table 3.

Assessment of respiratory function and physical function in patients with moderate and severe disease, on day 14 after discharge.

| Moderate (n = 238) |

Severe(n = 64) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| mMRC score | <0.001 | ||

| 0 | 238 (100%) | 55 (85.9%) | |

| ≥1 | 0 (0%) | 9 (14.1%) | |

| Borg score | <0.001 | ||

| 0 | 234 (98.3%) | 52 (81.25%) | |

| ≥1 | 4 (1.7%) | 12 (18.75%) | |

| MMT score | <0.001 | ||

| 5 | 238 (100%) | 59 (92.2%) | |

| ≤4 | 0 (0%) | 5 (7.8%) |

mMRC, modified Medical Research Council; Borg, Borg dyspnea scale; MMT, manual muscle test.

Table 4.

Assessment of respiratory and physical function in RP and NRP patients, on day 14 after discharge.

| RP (n = 23) |

NRP(n = 279) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| mMRC score | 0.383 | ||

| 0 | 23 (100%) | 270 (96.8%) | |

| ≥1 | 0 (0%) | 9 (3.2%) | |

| Borg score | 0.239 | ||

| 0 | 23 (100%) | 263 (94.3%) | |

| ≥1 | 0 (0%) | 16 (5.7%) | |

| MMT score | 0.518 | ||

| 5 | 23 (100%) | 274 (98.2%) | |

| ≤4 | 0 (0%) | 5 (1.8%) |

RP, redetectable positive; NRP, non-redetectable positive; mMRC, modified Medical Research Council; Borg, Borg dyspnea scale; MMT, manual muscle test.

Table 5.

Assessment of respiratory and physical function in RP and NRP patients according to disease severity, on day 14 after discharge.

| RP (n = 23) |

NRP (n = 279) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moderate(n = 19) | Severe(n = 4) | P-value | Moderate(n = 219) | Severe(n = 60) | P-value | |

| mMRC score | 1.000 | <0.001 | ||||

| 0 | 19 (100%) | 4 (100%) | 219 (100%) | 51 (85.0%) | ||

| ≥1 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 9 (15.0%) | ||

| Borg score | 1.000 | <0.001 | ||||

| 0 | 19 (100%) | 4 (100%) | 215 (98.2%) | 48 (80.0%) | ||

| ≥1 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (1.8%) | 12 (20.0%) | ||

| MMT score | 1.000 | <0.001 | ||||

| 5 | 19 (100%) | 4 (100%) | 219 (100%) | 55 (91.7%) | ||

| ≤4 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (8.3%) | ||

RP, redetectable positive; NRP, non-redetectable positive; mMRC, modified Medical Research Council; Borg, Borg dyspnea scale; MMT, manual muscle test.

Evaluation of respiratory and physical function of COVID-19 patients at 6 months after discharge

This study conducted a 6-month follow-up of 132 discharged COVID-19 patients, including 23 in the RP group and 109 in the NRP group. A comparison between the two groups showed that the proportion of patients using antiviral therapy was still lower in the RP group than in the NRP group (Table 6). Moreover, there was a statistically significant difference in age between the patients in the RP and NRP groups (Table 6).

Table 6.

Clinical characteristics of patients followed up to 6 months.

| Characteristics | RP (n = 23) | NRP (n = 109) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 35 (27–48) | 48 (37–60) | 0.002 |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.258 | ||

| Male | 15 (65.2%) | 57 (52.3%) | |

| Female | 8 (34.8%) | 52 (47.7%) | |

| Type, n (%) | 0.053 | ||

| Moderate | 19 (82.6%) | 67 (61.5%) | |

| Severe | 4 (17.4%) | 42 (38.5%) | |

| Antiviral therapya, n (%) | 0.003 | ||

| Yes | 18 (78.3%) | 104 (95.4%) | |

| No | 5 (21.7%) | 3 (2.8%) | |

| Missing | 0 (0%) | 2 (1.8%) | |

| Comorbidity, n (%) | 0.294 | ||

| Yes | 6 (26.1%) | 41 (37.6%) | |

| No | 17 (73.9%) | 68 (62.4%) |

RP, redetectable positive; NRP, non-redetectable positive; IQR, interquartile range.

Antiviral drugs included arbidol, lopinavir, ritonavir, oseltamivir, darunavir cobistat, and favipiravir.

At 6 months after the COVID-19 patients had been discharged from the hospital, the mMRC, Borg, and MMT scores of patients who had recovered from severe-type COVID-19 were still worse than those of patients who had recovered from moderate-type COVID-19 (Table 7 ). There were no differences in mMRC, Borg, and MMT scores between the RP and NRP groups (Table 8 ). Further stratified comparison showed that there were no differences in mMRC, Borg, and MMT scores between patients who had recovered from moderate-type COVID-19 and those who had recovered from severe-type COVID-19 in the RP group. However, the mMRC, Borg, and MMT scores for patients who had recovered from severe-type COVID-19 were worse in the NRP group (Table 9 ).

Table 7.

Assessment of respiratory function and physical function in patients with moderate and severe disease followed up to 6 months after discharge.

| Moderate (n = 86) |

Severe(n = 46) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| mMRC score | 0.006 | ||

| 0 | 84 (97.7%) | 39 (84.8%) | |

| ≥1 | 2 (2.3%) | 7 (15.2%) | |

| Borg score | 0.001 | ||

| 0 | 82 (95.3%) | 35 (76.1%) | |

| ≥1 | 4 (4.7%) | 11 (23.9%) | |

| MMT score | 0.006 | ||

| 5 | 86 (100%) | 42 (91.3%) | |

| ≤4 | 0 (0%) | 4 (8.7%) |

mMRC, modified Medical Research Council; Borg, Borg dyspnea scale; MMT, manual muscle test.

Table 8.

Assessment of rehabilitation in RP and NRP patients followed up to 6 months after discharge.

| RP (n = 23) | NRP (n = 109) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| mMRC score | 0.155 | ||

| 0 | 23 (100%) | 100 (91.7%) | |

| ≥1 | 0 (0%) | 9 (8.3%) | |

| Borg score | 0.06 | ||

| 0 | 23 (100%) | 94 (86.2%) | |

| ≥1 | 0 (0%) | 15 (13.8%) | |

| MMT score | 0.686 | ||

| 5 | 22 (95.7%) | 106 (97.2%) | |

| ≤4 | 1 (4.3%) | 3 (2.8%) |

RP, redetectable positive; NRP, non-redetectable positive; mMRC, modified Medical Research Council; Borg, Borg dyspnea scale; MMT, manual muscle test.

Table 9.

Respiratory function and physical function assessment of RP and NRP patients followed up to 6 months after discharge.

| RP (n = 23) |

NRP (n = 109) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moderate(n = 19) | Severe(n = 4) | P-value | Moderate(n = 67) | Severe(n = 42) | P-value | |

| mMRC score | 1.000 | 0.013 | ||||

| 0 | 19 (100%) | 4 (100%) | 65 (97.0%) | 35 (83.3%) | ||

| ≥1 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (3.0%) | 7 (16.7%) | ||

| Borg score | 1.000 | 0.002 | ||||

| 0 | 19 (100%) | 4 (100%) | 63 (94.0%) | 31 (73.8%) | ||

| ≥1 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (6.0%) | 11 (26.2%) | ||

| MMT score | 0.456 | 0.027 | ||||

| 5 | 19 (100%) | 3 (75.0%) | 67 (100%) | 39 (92.9%) | ||

| ≤4 | 0 (0%) | 1 (25.0%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (7.1%) | ||

RP, redetectable positive; NRP, non-redetectable positive; mMRC, modified Medical Research Council; Borg, Borg dyspnea scale; MMT, manual muscle test.

Comparison of respiratory and physical function between the RP and NRP groups on day 14 and at 6 months after discharge

There were no differences in the mMRC, Borg, and MMT scores of the RP and NRP groups at 14 days and 6 months after discharge (Table 10 ).

Table 10.

Assessment of respiratory function and physical function in RP and NRP patients, 14 days and 6 months after discharge.

| RP (n = 23) |

NRP (n = 109) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14 days | 6 months | P-value | 14 days | 6 months | P-value | |

| mMRC score | 1.000 | 0.857 | ||||

| 0 | 23 (100%) | 23 (100%) | 101 (92.7%) | 100 (91.7%) | ||

| ≥1 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 8 (7.3%) | 9 (8.3%) | ||

| Borg score | 1.000 | 0.832 | ||||

| 0 | 23 (100%) | 23 (100%) | 93 (85.3%) | 94 (86.2%) | ||

| ≥1 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 16 (14.7%) | 15 (13.8%) | ||

| MMT score | 0.317 | 0.466 | ||||

| 5 | 23 (100%) | 22 (95.7%) | 104 (95.4%) | 106 (97.2%) | ||

| ≤4 | 0 (0%) | 1 (4.3%) | 5 (4.6%) | 3 (2.8%) | ||

RP, redetectable positive; NRP, non-redetectable positive; mMRC, modified Medical Research Council; Borg, Borg dyspnea scale; MMT, manual muscle test.

Discussion

This study retrospectively analyzed the demographic characteristics and respiratory and physical function of patients who were RP and those who were NRP. A total of 23 RP patients were included, accounting for 7.6% of the patients discharged during the study period. The study results showed that the proportion of patients using antiviral drugs in the RP group was significantly lower than that in the NRP group. A lack of antiviral treatment may cause incomplete elimination of the virus. When the viral load is insufficient or below the reagent threshold, a false-negative result will occur. After the patient is discharged from the hospital, due to a lack of treatment, virus proliferation fluctuates, resulting in a positive nucleic acid test again (He et al., 2020).

In this study, patients in the RP group had recovered from mainly mild and moderate COVID-19. The amount of virus in patients with different disease courses and conditions may vary. When the SARS-CoV-2 load is low, intermittent detoxification will occur during the disease course. This will manifest as negative nucleic acid test results in the intermittent period and positive results during detoxification (Qi et al., 2020). This may also be the cause of the positive nucleic acid retest results.

The current study showed that at 6 months after the patients had been discharged from the hospital, the proportion of moderate disease patients in the RP group was greater. Previous studies have reported that patients with moderate disease were younger than those with severe disease (Zhou et al., 2020). The present study showed that the age of the patients in the RP group was significantly lower than that of the patients in the NRP group; this may be related to the higher proportion of patients with moderate disease in the RP group. Therefore, for patients discharged from the hospital, more attention should be paid to nucleic acid testing of young patients who had disease of moderate type at the initial stage of onset.

However, to date, there has been no report of infections in individuals exposed to patients who have retested positive. A study from South Korea conducted virus culture on 285 COVID-19 patients who retested positive during rehabilitation, and all culture results were negative. This confirmed that there was no active virus in the samples from these patients (Kang, 2020). Therefore, a positive nucleic acid test result for SARS-CoV-2 can only indicate that viral nucleic acid has been detected, but not that the virus is reactivated or has caused reinfection (Lan et al., 2020). Whether reinfection or reactivation has occurred can be further confirmed by virus whole genome sequencing and virus culture.

A follow-up study of 383 patients recovering from severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) indicated that 27.3% of the patients had impaired pulmonary diffusion function at hospital discharge. Forty of these patients were followed up for 1 year, at which time 20 patients (50%) still had abnormal lung function (Xie et al., 2005). This shows that the impact of coronaviruses on the lungs is long-lasting. Most reports on abnormal respiratory function in COVID-19 patients have focused on the state of the patients at discharge (Mo et al., 2020). Some COVID-19 patients had difficulty breathing after activities of varying degrees at discharge. Post-inflammation pulmonary fibrosis was seen on imaging, and some cases manifested as varying degrees of usual interstitial pneumonia or non-specific interstitial pneumonia (Zhan et al., 2020). In addition, angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptors are widespread in the human body, and SARS-CoV-2 causes an inflammatory factor storm. Thus, apart from the damage to the lungs, SARS-CoV-2 infection may cause damage to the cardiovascular and renal systems (Su et al., 2020, Lindner et al., 2020). We retrieved only one cohort study on the prognosis of patients with COVID-19 during the rehabilitation period. The study suggested that abnormalities in lung diffusion function and imaging are more common in severe-type cases at 6 months after discharge (Huang et al., 2021). However, the study did not analyze the prognosis of patients who retested positive.

The current study found that the mMRC, Borg, and MMT scores of severe-type cases on day 14 and at 6 months after discharge were worse than those of the moderate-type cases. There were no differences in respiratory and physical function between the RP and NRP groups on day 14 and at 6 months after discharge. In the NRP group, the respiratory and physical function scores of severe-type cases were worse. In the RP group, the respiratory and physical function scores of severe-type cases did not differ from those of moderate-type cases. This may be related to the lower average age and lower proportion of severe-type cases in the RP group of this study. Therefore, we believe that the follow-up of RP patients can be the same as that of NRP patients.

When assessing the prognosis of COVID-19, attention should be paid to disease severity at the time of initial hospitalization, and focus should be on the severe-type cases. Patients with possible abnormal prognoses should be screened out through the assessment form for respiratory and physical functions. Corresponding examinations, assessments, and rehabilitation guidance should then be performed on this population. This study clarified the populations that deserve close attention after discharge, provided a simple evaluation method, and screened out patients with abnormal recovery through simple evaluation. However, there is a need to further study the correlation of these abnormal scores with abnormal lung function and chest CT scans. This will require multicenter studies on a larger scale.

Conclusions

Overall, the study findings reveal that the prognoses of RP and NRP patients are not different in terms of respiratory and physical function. The recovery of respiratory and physical function in COVID-19 patients during rehabilitation was not related to whether the patient retested positive; however, it was related to the patient’s condition during hospitalization. It is necessary to strengthen the evaluation and observation of patients with severe-type disease after discharge.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, this was a single-center retrospective study with a limited sample size and follow-up. Therefore, multicenter studies with a longer follow-up are needed to evaluate the prognosis of patients who retest positive. Second, dynamic changes in serum specific antibody levels in RP patients were not studied. These should be further studied in order to determine the continuous protective effect of serum specific antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 and the relationship between antibody levels and positive retest results.

Author contributions

Qian Wu, Xinwei Hou, Hongwei Li, Jing Guo, Yajie Li, Fangfei Yang, and Yan Zhang performed the database search, screening, quality assessment, and data extraction. Qian Wu and Xinwei Hou conducted the analysis. Qian Wu, Xinwei Hou, Yi Xie, and Li Li contributed to the writing of the manuscript. All authors approved the final draft of the manuscript.

Funding sources

This work was supported by Tianjin Haihe Hospital Science and Technology Fund (HHYY-202001).

Data availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for writing support.

References

- Casanova C., Marin J.M., Martinez-Gonzalez C., de Lucas-Ramos P., Mir-Viladrich I., Cosio B., et al. COPD History Assessment in Spain (CHAIN) Cohort. Differential Effect of Modified Medical Research Council Dyspnea, COPD assessment test, and clinical COPD questionnaire for symptoms evaluation within the new GOLD staging and mortality in COPD. Chest. 2015;148(July (1)):159–168. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-2449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du H.W., Chen J.N., Pan X.B., Chen X.L., Yixian-Zhang, Fang S.F., et al. Fujian Medical Team Support Wuhan for COVID-19. Prevalence and outcomes of re-positive nucleic acid tests in discharged COVID-19 patients. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2020;(August) doi: 10.1007/s10096-020-04024-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gousseff M., Penot P., Gallay L., Batisse D., Benech N., Bouiller K., et al. Clinical recurrences of COVID-19 symptoms after recovery: viral relapse, reinfection or inflammatory rebound? J Infect. 2020;81(November (5)):816–846. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.06.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y., Dong Y.C. A perspective on re-detectable positive SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid results in recovered COVID-19 patients. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2020;(October):1–19. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2020.392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C., Huang L., Wang Y., Li X., Ren L., Gu X., et al. 6-month consequences of COVID-19 in patients discharged from hospital: a cohort study. Lancet. 2021;(January) doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32656-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Just N., Bautin N., Danel-Brunaud V., Debroucker V., Matran R., Perez T. The Borg dyspnoea score: a relevant clinical marker of inspiratory muscle weakness in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Eur Respir J. 2010;35(February (2)):353–360. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00184908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang Y.J. South Korea’s COVID-19 infection status: from the perspective of re-positive test results after viral clearance evidenced by negative test results. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2020;(May):1–3. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2020.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan L., Xu D., Ye G., Xia C., Wang S., Li Y., et al. Positive RTPCR test results in patients recovered from COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;323(15):1502–1503. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J.J., Karen W., Martina G.S., Xue F., Jarone L., Daniel C., et al. Global muscle strength but not grip strength predicts mortality and length of stay in a general population in a surgical intensive care unit. Phys Ther. 2012;92(December (12)):1546–1555. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20110403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindner D., Fitzek A., Bräuninger H., Aleshcheva G., Edler C., Meissner K., et al. Association of cardiac infection with SARS-CoV-2 in confirmed COVID-19 autopsy cases. JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5(November (11)):1281–1285. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.3551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mei Q., Li J., Du R., Yuan X., Li M., Li J., et al. Assessment of patients who tested positive for COVID-19 after recovery. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(September (9)):1004–1005. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30433-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mo X., Jian W., Su Z., Chen M., Peng H., Peng P., et al. Abnormal pulmonary function in COVID-19 patients at time of hospital discharge. Eur Respir J. 2020;55(June (6)) doi: 10.1183/13993003.01217-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi L., Yang Y., Jiang D., Tu C., Wan L., Chen X., et al. Factors associated with the duration of viral shedding in adults with COVID-19 outside of Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;96(July):531–537. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.05.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen M., Zhou Y., Ye J., Abdullah Al-Maskri A.A., Kang Y., Zeng S., et al. Recent advances and perspectivesof nucleic acid detection for coronavirus. Pharm Anal. 2020;10(March (2)):97–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jpha.2020.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su H., Yang M., Wan C., Yi L.X., Tang F., Zhu H.Y., et al. Renal histopathological analysis of 26 postmortem findings of patients with COVID-19 in China. Kidney Int. 2020;98(July (1)):219–227. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. https://covid19.who.int/. [Accessed 6 April 2021].

- Xie L., Liu Y., Fan B., Xiao Y., Tian Q., Chen L., et al. Dynamic changes of serum SARS-coronavirus IgG, pulmonary function and radiography in patients recovering from SARS after hospital discharge. Respir Res. 2005;6(January):5. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-6-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhan X., Liu B., Tong Z.H. Postinflammatroy pulmonary fibrosis of COVID-19: the current status and perspective. Zhonghua Jie He He Hu Xi Za Zhi. 2020;43(September (9)):728–732. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112147-20200317-00359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng J., Zhou R., Lei C., Wu X. Incidence, clinical course and risk factor for recurrent PCR positivity in discharged COVID-19 patients in Guangzhou, China: a prospective cohort study. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2020;14(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0008648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou F., Yu T., Du R., Fan G., Liu Y., Liu Z., et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(March (10229)):1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.