Abstract

Background

Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) is a complex and debilitating disease accompanied by muscular fatigue and pain. A functional measure to assess muscle fatigability of ME/CFS patients is, however, not established in clinical routine. The aim of this study is to evaluate by assessing repeat maximum handgrip strength (HGS), muscle fatigability as a diagnostic tool and its correlation with clinical parameters.

Methods

We assessed the HGS of 105 patients with ME/CFS, 18 patients with Cancer related fatigue (CRF) and 66 healthy controls (HC) using an electric dynamometer assessing maximal (Fmax) and mean force (Fmean) of ten repetitive measurements. Results were correlated with clinical parameters, creatinine kinase (CK) and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH). Further, maximum isometric quadriceps strength measurement was conducted in eight ME/CFS patients and eight HC.

Results

ME/CFS patients have a significantly lower Fmax and Fmean HGS compared to HC (p < 0.0001). Further, Fatigue Ratio assessing decline in strength during repeat maximal HGS measurement (Fmax/Fmean) was higher (p ≤ 0.0012). The Recovery Ratio after an identical second testing 60 min later was significantly lower in ME/CFS compared to HC (Fmean2/Fmean1; p ≤ 0.0020). Lower HGS parameters correlated with severity of disease, post-exertional malaise and muscle pain and with higher CK and LDH levels after exertion.

Conclusion

Repeat HGS assessment is a sensitive diagnostic test to assess muscular fatigue and fatigability and an objective measure to assess disease severity in ME/CFS.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12967-021-02774-w.

Keywords: Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome, Diagnostic, Handgrip, Muscular fatigue, Muscle strength, Muscular recovery

Background

Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (also known as Myalgic Encephalomyelitis, ME/CFS), is a complex disease with persistent mental and physical fatigue causing severe impairment of quality of life. The cardinal symptom is exertional intolerance with post-exertional malaise (PEM), which describes a disproportionate intensification of symptoms and a prolonged regeneration phase after physical or mental effort [1–3]. Muscle fatigability is another important hallmark in which muscles become weaker after exertion and it can last for days before full muscle strength is restored.

To date, the etiology and pathophysiology of ME/CFS is still unresolved, but there is ample evidence for a disturbed vascular regulation [4]. Diagnosing of ME/CFS is challenging for patients and physicians due to many unspecific symptoms, the broad differential diagnosis of chronic fatigue and the lack of an established biomarker. Currently, ME/CFS is a clinical diagnosis using comprehensive clinical evaluation and diagnostic criteria with the international Canadian Consensus Criteria (CCC) formulated by Carruthers et al. in 2003 as the most accepted [5]. However, to date ME/CFS patients are often un- or misdiagnosed as depression or burn-out, leading probably to a marked underestimation of prevalence [1, 6].

As objective measure to assess exertion intolerance in ME/CFS a repeat cardiopulmonary exercise test (CPET) is recommended by the National Institute of Health (NIH). Studies showed the maximum oxygen uptake and workload is significantly reduced at the day two of CPET [7]. However, the repeated exercise tests frequently lead to severe PEM and cannot be recommended for most patients [8].

Assessment of disease severity is mostly relied on questionnaires. Fatigue is a complex symptom and can be both mental and physical related to impaired muscle performance. Physical fatigue can be assessed objectively. Assessment of hand grip strength (HGS) is an established and highly reproducible tool to assess muscular strength and provides information about the person's physical function and state of health [9]. First studies showed that HGS is impaired in ME/CFS [10–12]. A recent study showed that maximal handgrip strength was significantly correlated with peak oxygen uptake and can predict maximal physical performance in CPET [13]. In the study by Meeus et al. also the HGS recovery after 45 min was analyzed and found to be impaired, while it was normal in HC [10]. Another approach to assess muscular force is the measurement of the quadriceps strength (QS). In an earlier study, ME/CFS patients showed lower QS and a prolonged recovery compared to the control group when performing consecutive contractions [14], another study reported normal quadriceps muscle force in ME/CFS [15].

Chronic fatigue occurs in many other diseases including cancer. About 30% of cancer survivors suffer from cancer-related fatigue (CRF) years after treatment severely impairing patients’ quality of life [16]. In order to assess specificity of HGS assessment for ME/CFS we included a cohort of CRF patients in our study.

In this study we evaluate repeat HGS measurement for assessing muscle fatigue in ME/CFS. By performing repeat hand grip testing fatigability and recovery of muscle strength could be assessed as diagnostic test.

Methods

Patients and controls

105 patients with ME/CFS and 18 patients with CRF who presented at the outpatient clinic for fatigue at the Institute for Medical Immunology at the Charité Berlin from December 2018 to January 2021 were included in the study. ME/CFS patients were diagnosed based on the Canadian Consensus Criteria (CCC) and exclusion of other medical or neurological diseases which may cause fatigue [5]. Further inclusion criteria were age ≤ 18 years or participation in an interventional study. CRF patients were diagnosed according to Cella criteria [16] and had to be in complete remission for at least six months. 66 age and sex–matched HC with self-reported healthy status served as control group. For QS measurement we included eight female ME/CFS patients and eight female healthy controls.

Hand grip measurement

We measured the HGS with a digital hand dynamometer (CAMRY, model: SCACAM-EH101) in two separate sessions with a recovery break of 60 min between the sessions. The participant had to sit in an upright position and place the forearm of the dominant hand on a standard table in full supination. Before the start of the measurement, all participants had the opportunity to pull the handle twice to become familiar with the device. The handle was pulled with maximum force for three seconds followed by a five second relaxation phase under supervision by the study nurse. Within one session this procedure was repeated ten times with the dominant hand. After 60 min without any strenuous physical activity, a second session was conducted. Participants were verbally motivated during the measurement to continue using their maximum strength and to perform all repetitions. The dynamometer measures the highest value reached within the three seconds (force measurement in kg). The attempt with the highest measurement out of the ten repetitions was recorded as maximum strength.

Assessment of Fmax and Fmean strength, fatigability and recovery

To estimate strength, fatigability and recovery we examined several parameters and ratios listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Parameters of muscle strength assessed by handgrip measurements

| Parameter/Ratio | Formula | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Fmax | Fmax [kg] | Maximum grip strength within one session (ten repeat trials) |

| Fmean | Mean grip strength of all ten trials | |

| Fatigue ratio (assessment of fatigability) | Higher values indicate stronger decrease of force during one session | |

| Recovery ratio (assessment of recoverability) | Low values indicate impaired recovery |

Quadriceps strength measurement

Maximal isometric muscle strength of the quadriceps muscle (expressed in Newton, N) was measured as described in previous publications [17]. Briefly, the freely hanging leg of the sitting participant was connected at the ankle with a pressure transducer (Multitrace 2, Lectromed, Jersey, Channel Islands). Baseline maximal isometric strength was assessed from the best of three contractions on each leg, with a resting period of at least 60 s in between.

Afterwards the quadriceps muscle fatigue protocol was performed on the stronger leg as described previously [18]. In brief, participant performed repeated contractions at 30–40% of the maximum strength for one second, followed by one second of relaxations, using an acoustic signal as a guide. This cycle was performed for 40 s, followed by 20 s of rest. The 60 s cycle was repeated for 20 min. Participants were asked to undertake a maximal contraction at 5, 10, 15 and 20 min.

Assessment of symptoms by scores

Each participating ME/CFS patient filled in the following questionnaires.

Bell score

Assessment of disease severity and everyday restrictions ranging from zero (total loss of self-dependence) to 100 (without restrictions) [19].

SF-36—Health status questionnaire

Assessment of physical function ranging from zero (greatest possible health restrictions) to 100 (no health restrictions) [20].

Chalder Fatigue Scale

Assessment of the severity of fatigue on a scale from zero (no fatigue) to 33 (heavy fatigue) [21].

COMPASS-31

Assessment of autonomic dysfunction including vasomotor, orthostatic, ocular, bladder and gastrointestinal symptoms ranging from zero (without symptoms) to 100 (strong autonomic dysfunction) [22] as was shown previously in ME/CFS patients [23].

PEM criteria

Assessment of frequency, severity and duration of post-exertional malaise (PEM) symptoms, such as muscle weakness, pain or mental tiredness, ranging from 0 (no PEM) to 46 (frequent, severe and long PEM) [24].

Symptom Score

Quantification of symptoms of the Canadian Consensus Criteria (one = no symptoms to ten = extreme symptoms) [25, 26].

Assessment of CK and LDH

Creatine kinase (CK, immunological UV-test) and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH, photometric test) were determined from blood samples drawn after the second HGS assessment at the Charité diagnostics laboratory (Labor Berlin GmbH, Berlin, Germany).

Statistical analysis

We performed the statistical analysis with the software GraphPad Prism 6.0. To exclude physiological, sex-related differences in strength, we studied male and female subjects separately. Gaussian distribution of data was examined by D’Agostino and Pearson test. Accordingly, we used unpaired t-tests and Mann–Whitney test to analyze differences between the groups. For comparison of the first and the second session we used paired t-test. For detection of linear and non-linear correlations we calculated Pearson and Spearman correlation coefficients, respectively. For analyzation of the diagnostic ability of handgrip measurements and determination of discrimination thresholds between HC and ME/CFS, we performed receiver operator characteristics (ROC) analyses and computed sensitivity and specificity. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. Due to multiple testing p-values are considered descriptive.

Results

Study population

105 ME/CFS patients were enrolled for HGS measurement. Control groups were 66 age- and sex-matched healthy controls (HC) and 18 female patients with cancer related fatigue (CRF). Table 2 provides further characteristics of the participants.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the study population

| HC | ME/CFS | CRF | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size (n) | 66 | 105 | 18 | ||

| Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | |

| 36 | 30 | 61 | 44 | 18 | |

| Age (years) | 42 (22–62) | 33.5 (21–62) | 49 (21–76) | 40 (18–60) | 44.5 (19–63) |

| Bell Score | – | – | 30 (10–65) | 40 (20–70) | 35 (30–80) |

| Duration of disease (years) | – | – | 4 (1–32) | 4 (1–42) | 6 (1–16) |

| Post-infectious ME/CFS | – | – | n = 52 | n = 40 | – |

Median values with range in brackets

HC healthy controls, ME/CFS myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome, CRF cancer related fatigue, Bell Bell Score

Fmax and Fmean HGS

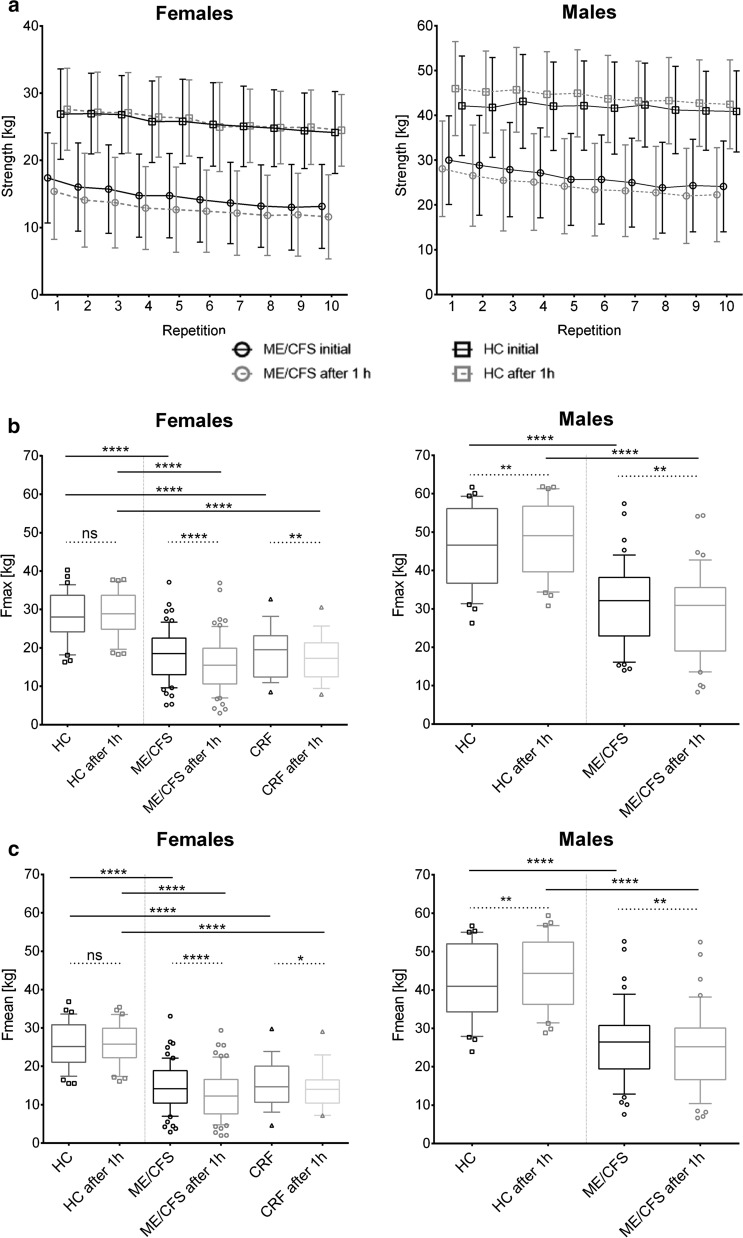

All 189 participants completed ten consecutive maximal HGS measurements which were repeated after 60 min. Both male and female ME/CFS patients showed strongly reduced maximal and mean HGS in the first session (Fmax1, Fmean1) and the second session after one hour (Fmax2, Fmean2) compared to HC (Table 3 and Fig. 1, all p < 0.0001). In female CRF patients Fmax and Fmean in both sessions were also significantly diminished compared to female HC (Table 3, Fig. 1, both p < 0.0001).

Table 3.

Results of handgrip strength measurement

| Females | Males | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HC, n = 36 | ME/CFS, n = 61 | CRF, n = 18 | HC, n = 30 | ME/CFS, n = 44 | ||||||

| Fmax1 | 28.2 (6.25) | 18.1 (6.68) | p < 0.0001 | 18.9 (6.73) |

p < 0.0001 p < 0.0001 |

45.8 (10.2) | 31.2 (10.4) | p < 0.0001 | ||

| Fmax2 | 28.7 (5.73) | 16.0 (7.14) | p < 0.0001 | 17.2 (6.00) | 48.3 (9.58) | 29.2 (10.9) | p < 0.0001 | |||

| Fmean1 | 25.6 (5.87) | 14.6 (6.09) | p < 0.0001 | 15.5 (6.34) |

p < 0.0001 p < 0.0001 |

41.8 (9.66) | 26.3 (9.91) | p < 0.0001 | ||

| Fmean2 | 25.9 (5.46) | 12.9 (6.24) | p < 0.0001 | 14.3 (5.74) | 44.2 (9.32) | 24.5 (10.4) | p < 0.0001 | |||

| Fatigue Ratio 1 | 1.105 (0.09) | 1.300 (0.297) | p < 0.0001 | 1.261 (0.21) | p = 0.0001 | 1.097 (0.04) | 1.213 (0.18) |

p = 0.0006 p = 0.0012 |

||

| Fatigue Ratio 2 | 1.113 (0.07) | 1.299 (0.25) | p < 0.0001 | 1.223 (0.13) | p = 0.0004 | 1.097 (0.05) | 1.216 (0.17) | |||

| Recovery Ratio | 1.0 (0.077) | 0.87 (0.19) | p < 0.0001 | 0.96 (0.26) | p = 0.0020 | 1.1 (0.14) | 0.92 (0.14) | p < 0.0001 | ||

| Comparison of first and second measurement | ||||||||||

| Fmax1 | 28.2 | p = 0.3295 | 18.1 | p < 0.0001 | 18.9 | p = 0.0053 | 45.8 | p = 0.0048 | 32.2 | p = 0.0019 |

| Fmax2 | 28.7 | 16.0 | 17.2 | 48.3 | 29.2 | |||||

| Fmean1 | 25.6 | p = 0.3537 | 14.6 | p < 0.0001 | 15.5 | p = 0.0376 | 41.8 | p = 0.0057 | 26.3 | p = 0.0022 |

| Fmean2 | 25.9 | 12.9 | 14.3 | 44.2 | 24.5 | |||||

Mean value of handgrip strength in kg and ratios with standard deviation in brackets; p-value refers to comparison with healthy controls (Mann–Whitney-Test) or, in the second compartment of the table, to comparison of both sessions (Paired t-test), respectively

Fig. 1.

Handgrip strength (a), Fmax (b) and Fmean (c). ME/CFS patients showed lower levels and stronger decrease of HGS compared to HC over ten repeat pulls resulting in significantly diminished Fmax and Fmean in the patient group. Further, Fmax and Fmean dropped significantly after one hour in ME/CFS as well as in CRF patients, whereas it remains unchanged in healthy women or even raised in healthy men. Ten repeat measurements of maximal HGS were performed in two sessions (60-mininterval) by a hand dynamometer (in kg). Left: female ME/CFS patients (circles, n = 61), CFR patients (triangles, n = 18) and HC (squares, n = 36); right: male ME/CFS patients (circles, n = 44) and (HC, (squares, n = 30). Continuous line: initial session, dotted line: second session after one hour. Boxplots 10–90 percentile with outliers, ns = p > 0.05, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001 (Mann–Whitney-Test for comparison between groups, paired-t-test for comparison of both sessions). Mean values in kg with SD

Further, ME/CFS patients had a significantly lower Fmax and Fmean HGS in the second session compared to the first (Table 3 and Fig. 1). In female CRF patients, Fmax and Fmean were significantly reduced in the second session. In contrast female HC showed a similar Fmax and Fmean after one-hour break and male HC even a significant increase in Fmax and Fmean.

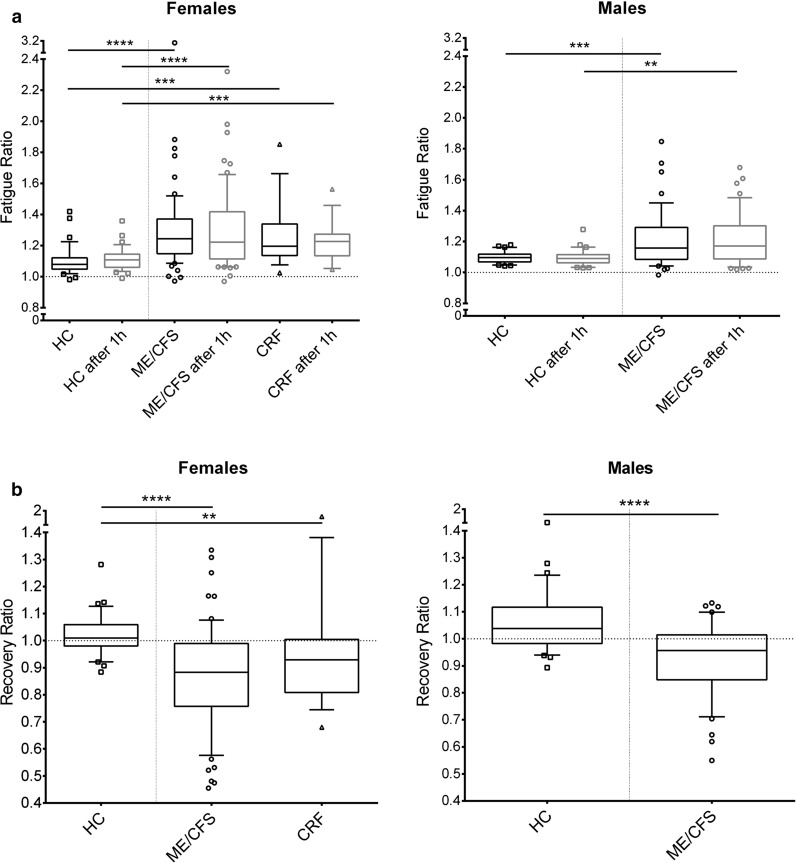

Fatigability and recovery of HGS

The Fatigue Ratio (Fmax/Fmean) was assessed as correlate of decrease of HGS during repeat measurements. ME/CFS patients had a stronger decrease in HGS resulting in higher Fatigue Ratios in comparison to HC in both first and second measurement (Table 3 and Fig. 2a). Further, Recovery Ratio of HGS (Fmean2/Fmean1) was diminished in the ME/CFS patients, as correlate of lower HGS during the second measurement, while HC had Recovery Ratios values of about one (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2.

Fatigue ratio (a) and Recovery ratio (b) ME/CFS patients as well as female CRF patients showed higher Fatigue Ratios in both sessions and lower Recovery Ratios compared to HC. Ten repeat measurements of maximal HGS were performed in two sessions (60-min interval) by a hand dynamometer (in kg). Fatigue Ratio = (Fmax/Fmean), Recovery Ratio = (Fmean2/Fmean1). Left: female ME/CFS patients (circles, n = 61), CRF patients (triangles, n = 18) and HC (squares, n = 36), right: male ME/CFS patients (circles, n = 44) and HC (squares, n = 30). Boxplots (10–90 Percentile), ns = p > 0.05, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001 (Mann–Whitney-Test)

In female CRF patients, similar to ME/CFS, higher Fatigue Ratios 1 and 2 and reduced Recovery Ratios were observed compared to HC (Fig. 2 and Table 3).

Correlation of HGS with symptom severity in ME/CFS patients

We next correlated HGS with parameters of symptom severity and disability (Table 4 and Additional file 1: Figures S1, Additional file 2: Figure S2 and Additional file 4: Table S1).

Table 4.

Clinical characteristics of ME/CFS and correlations with handgrip strength

| Female | Male | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bell | Median | Range | n | Median | Range | n |

| 30 | 10–65 | 59 | 40 | 20–70 | 42 | |

| Correlations | r | p | type | r | p | type |

| Fmax1 | 0.2670 | 0.0409 | lin | 0.115 | 0.4682 | lin |

| Fmean1 | 0.1226 | 0.3551 | non-lin | 0.3255 | 0.0354 | non-lin |

| Fmean2 | 0.1444 | 0.2710 | non-lin | 0.3175 | 0.0405 | non-lin |

| Fatigue Ratio1 | 0.07946 | 0.5497 | non-lin | − 0.3995 | 0.0088 | non-lin |

| Fatigue Ratio2 | − 0.211 | 0.0643 | non-lin | − 0.3624 | 0.0183 | lin |

| PEM | Median | Range | n | Median | Range | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 37 | 9–46 | 35 | 34 | 21–46 | 35 | |

| Correlations | r | p | type | r | p | Type |

| Fmean2 | − 0.334 | 0.0499 | non-lin | − 0.1987 | 0.2526 | non-lin |

| Fatigue Ratio2 | 0.4040 | 0.0161 | lin | 0.34 | 0.0457 | lin |

| Muscle Pain | Median | Range | n | Median | Range | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 | 0–10 | 50 | 6 | 1–10 | 39 | |

| Correlations | r | p | type | r | p | Type |

| Fmean2 | − 0.3095 | 0.0287 | lin | − 0.1643 | 0.3175 | lin |

| Recovery Ratio | − 0.282 | 0.0472 | non-lin | − 0.1542 | 0.3488 | non-lin |

| COMPASS vasomotor | Median | Range | n | Median | Range | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0–5 | 49 | 0 | 0–5 | 40 | |

| Correlations | r | p | Type | r | p | Type |

| Fmax1 | − 0.2664 | 0.0643 | non-lin | − 0.3537 | 0.0251 | non-lin |

| Fmax2 | − 0.3635 | 0.0102 | non-lin | − 0.4327 | 0.0026 | non-lin |

| Fmean1 | − 0.3013 | 0.0354 | non-lin | − 0.3784 | 0.0161 | non-lin |

| Fmean2 | − 0.3663 | 0.0096 | non-lin | − 0.5767 | < 0.0001 | non-lin |

| Fatigue Ratio2 | 0.03817 | 0.7946 | lin | 0.4869 | 0.0014 | lin |

| Recovery Ratio | − 0.1938 | 0.1821 | non-lin | − 0.628 | < 0.0001 | non-lin |

| SF-36 phys. funct | Median | Range | n | Median | Range | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 40 | 5–90 | 52 | 47.5 | 0–100 | 38 | |

| Correlations | r | p | Type | r | p | Type |

| Fmax2 | 0.1724 | 0.2217 | non-lin | 0.3474 | 0.0351 | non-lin |

| Fmean2 | 0.2326 | 0.0970 | lin | 0.3605 | 0.0284 | lin |

| CK | Median | Range | n | Median | Range | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 67.5 | 15–229 | 48 | 90 | 29–447 | 33 | |

| Correlations | r | p | Type | r | p | Type |

| Fatigue Ratio2 | 0.3054 | 0.0348 | lin | − 0.1856 | 0.3092 | lin |

| Recovery Ratio | − 0.2935 | 0.0429 | lin | − 0.1045 | 0.5691 | lin |

| LDH | Median | Range | n | Median | Range | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 216 | 150–286 | 47 | 225.5 | 145–308 | 34 | |

| Correlations | r | p | Type | r | p | Type |

| Fatigue Ratio1 | − 0.06696 | 0.6547 | non-lin | 0.3522 | 0.0411 | non-lin |

| Fatigue Ratio2 | 0.3630 | 0.0122 | non-lin | 0.2683 | 0.125 | non-lin |

| Recovery Ratio | − 0.0336 | 0.8226 | non-lin | − 0.378 | 0.0275 | non-lin |

Clinical parameters with significant correlations with HGS and HGS ratios. Pearson (lin) or Spearman (non-lin) correlation coefficients were calculated. Bold: significant correlations with p < 0.05

Lower HGS parameters correlated with more disability (Bell Score), post-exertional malaise and muscle pain. Specifically, the Bell score correlated with Fmax1 in females and with Fmean and Fatigue Ratios in males. Higher PEM scores correlated with lower Fmean2 in females and higher Fatigue Ratio2 in both sexes and more muscle pain with lower Fmean2 and Recovery Ratio in females. Strikingly, the COMPASS score for vasomotor dysregulation assessing changes of skin color on hands/feet correlated with Fmax2 and Fmean1,2 in both males and females and in Fmax1, Fatigue Ratio2 and Recovery Ratio in males, too. Physical functioning assessed by SF-36 questionnaire correlated with Fmax2 and Fmean2 in males.

No correlations were found with total COMPASS score and severity of fatigue assessed by Chalder Fatigue Scale (Additional file 4: Table S1).

Correlation of HGS with CK and LDH post exertion in ME/CFS patients

Finally, we correlated the muscle enzymes CK and the pyruvate to lactate catalyzing enzyme LDH assessed after exertion with HGS parameters (Table 4). Both CK and LDH are marker of muscle damage, too. In females, higher CK correlated with higher Fatigue Ratio2 and lower Recovery Ratio. Higher Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) concentrations correlated in men with lower Recovery Ratio and higher Fatigue Ratio1 and in the female patients with higher Fatigue Ratio2.

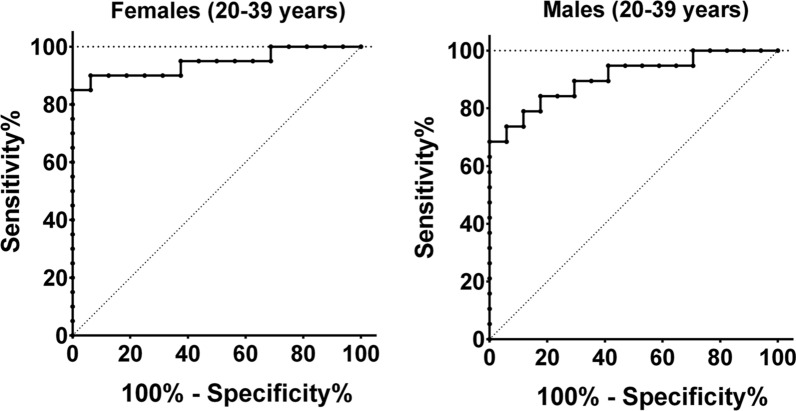

Sensitivity and specificity of HGS assessment

In order to analyze the suitability of HGS parameters as diagnostic test we conducted operator characteristics (ROC) analyses for the HGS parameters in males and females age-grouped in 20—39 years and 40 – 59 years. Cutoff values and area under the curve (AUC) for age 20–39 years are listed in Table 5. The highest values for sensitivity and specificity showed the Fmean2 with an AUC of 0.94 at a cutoff of < 19.95 kg for females and an AUC of 0.91 at a cutoff of < 28.76 kg for males (Fig. 3, Table 5 and Additional file 3: Figure S3). Cutoff values and AUC for females and males aged 40–59 years are shown in Additional file 5: Table S2.

Table 5.

Cutoff values for hand grip strength (Age 20–39, ME/CFS vs HC)

| Sex | Cutoff Value | AUC | Sensitivity | Specificity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fmax1 | Females | < 23.55 kg | 0.8656 | 70 | 93.75 |

| Males | < 33.35 kg | 0.8762 | 68.42 | 94.12 | |

| Fmax2 | Females | < 24.40 kg | 0.9156 | 90 | 93.75 |

| Males | < 36.55 kg | 0.9025 | 78.95 | 88.24 | |

| Fmean1 | Females | < 19.74 kg | 0.9188 | 80 | 100 |

| Males | < 29.36 kg | 0.8947 | 73.68 | 94.12 | |

| Fmean2 | Females | < 19.95 kg | 0.9438 | 85 | 100 |

| Males | < 28.76 kg | 0.9071 | 68.42 | 100 | |

| Fatigue Ratio1 | Females | > 1.161 | 0.8500 | 75 | 87.5 |

| Males | > 1.197 | 0.5325 | 36.84 | 100 | |

| Fatigue Ratio2 | Females | > 1.200 | 0.8563 | 65 | 93.75 |

| Males | > 1.189 | 0.5728 | 36.84 | 94.12 | |

| Recovery Ratio | Females | < 0.914 | 0.7906 | 70 | 93.75 |

| Males | < 1.125 | 0.5820 | 100 | 23.53 |

Results of ROC-Analysis for males and females aged 20–39 years. ME/CFS patients (females n = 20, males n = 19) and HC (females n = 16, males n = 17). Bold: most distinct parameter

Fig. 3.

ROC analysis of Fmean2 Fmean2 reached a sensitivity of 85% and a specificity of 100% in female (left, ME/CFS: n = 20, HC:n = 16) and a sensitivity of 68% and a specificity of 100% in male (right, ME/CFS: n = 19; HC: n = 17) ME/CFS patients vs. HC aged 20–39 years

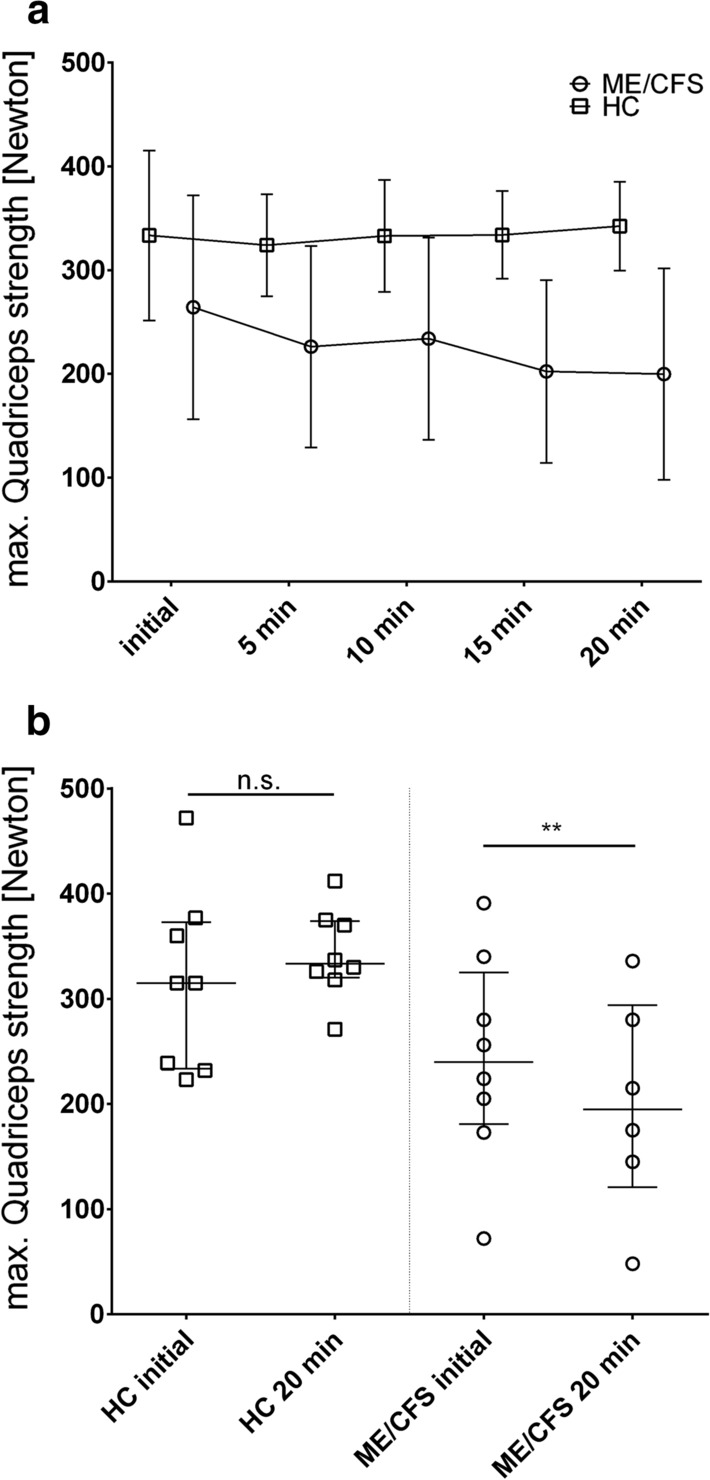

Quadriceps strength measurement

We performed five consecutive quadriceps strength (QS) measurements in eight female ME/CFS patients and eight female HC. Concordant to HGS, ME/CFS patients showed a significantly lower Fmax5 compared to Fmax1 compared to the HC resulting in a significantly lower Fmean (Table 6 and Fig. 4).

Table 6.

Results of quadriceps strength measurement

| Max. quadriceps strength [Newton] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| HC, n = 8 | ME/CFS, n = 8 | ||

| QS initial (Fmax1) | 333 (82) | 264 (108) | |

| 5 min (Fmax2) | 324 (46) | 237 (88) | |

| 10 min (Fmax3) | 333 (50) | 246 (88) | |

| 15 min (Fmax4) | 334 (39) | 212 (85) | |

| 20 min (Fmax5) | 342 (40) | 212 (90) | |

| Fmax5 in % of Fmax1 | 106.4 (21.8) | 76.1 (13.0) | p = 0.0045 |

| Fmean | 330 (46) | 223.5 (88) | p = 0.013 |

| Fatigue Ratio | 1.12 (0.058) | 1.23 (0.110) | p = 0.1171 |

Mean value of quadriceps strength with standard deviation in brackets; p-value refers to comparison with healthy controls (t-Test)

Fig. 4.

Quadriceps Strength over consecutive measurements (a) and Max strength (b) Female ME/CFS patients showed lower levels and stronger decrease of QS compared to HC upon repeat pulls (a) resulting in significantly diminished QS after 20 min (Fmax5) only in the patient group (b). a Mean value with standard deviation and b median with interquartile range, paired t-test. Squares: HC, n = 8, p = 0.7318, and circles: ME/CFS patients, n = 8, p = 0.0018

Discussion

In our study we show that patients with ME/CFS have reduced Fmax and Fmean HGS compared to HC. Our finding of impaired Fmax is in line with previous studies [10–13]. In addition, the greater decrease of HGS during ten repeated measurements compared to HC resulted in a higher Fatigue Ratio as was shown already in the study by Neu et al. [12]. Further, upon repeat measurement after an hour HGS was significantly lower in ME/CFS while it was fully recovered in HC indicating an impaired recovery rate in patients with ME/CFS as a parameter for fatigability. This finding is in accordance with the study by Meeus et al. describing an impaired recovery 45 min after 18 repeat maximal contractions [10].

Our study provides further evidence that repeat measurement of muscle strength via a hand dynamometer is a simple and useful method to objectively detect muscular fatigue and fatigability. ROC analyses revealed a high diagnostic sensitivity and specificity to distinguish between HC and ME/CFS with Fmean2 yielding best discrimination in women and men in both age groups. For assessing HGS as diagnostic marker in ME/CFS, we think it is important to use the Canadian Consensus Criteria requiring PEM. In contrast Ickmans et al. using the “Fukuda criteria” for diagnosis, which do not require PEM, observed significant differences in strength and recovery only for ME/CFS patients with comorbid fibromyalgia [27, 28].

Our findings are, however, not specific for ME/CFS as CRF patients showed significantly lower HGS parameters compared to HC, too. We found fatigability and impaired recovery also in female CRF patients. For HGS in patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) two studies delivered inconsistent findings. Nacul et al. showed diminished Fmax in MS patients in contrast to normal Fmax and recovery of HGS in the study by Meeus et al. [10, 11].

The quadriceps force measurement provides evidence that diminished muscular strength is found in leg muscles, too, showing in a similar pattern as the HGS that ME/CFS patients have a stronger drop in force upon repeated exertion. Thus, our study confirms the findings by Paul et al. [14] and is in contrast to the report by Gibson et al. of normal quadriceps muscle function in ME/CFS [15].

The correlations between HGS and clinical parameters underline the clinical relevance of HGS assessment in ME/CFS. Lower Bell scores (higher severity of disability) correlated with lower Fmax1 in women and lower Fmax and Fmean and higher Fatigue Ratio1 in men indicating a causal relation of muscular strength to severity of the disease. Remarkably, PEM correlated in women with lower Fmean2 and in women and men with higher Fatigue Ratio2, providing evidence that HGS is an objective marker to assess the severity of PEM. In line with this, severity of muscle pain correlated with lower Fmean2 and impaired recovery in the female cohort. A potential explanation is that more severe PEM is associated with more muscular fatigability and muscle pain. This might explain why pacing as a strategy to avoid PEM results in improvement of physical fatigue [29]. In the studies by Nacul et al. and Neu et al. fatigue assessed by a fatigue questionnaire correlated with Fmax HGS. In the male cohort we found correlations between the SF-36 physical functioning, and Fmax2 and Fmean2. In our study we could not find an association of HGS parameters with the Chalder Fatigue Scale, which is, however, a questionnaire focusing mostly on mental fatigue (Additional file 6: Table S3).

Serum LDH and CK are both marker of muscle metabolism and damage and known to rise after exertion. Interestingly LDH and CK, which we determined after repeat HGS measurements also correlated with HGS parameters. Higher LDH concentrations correlated with higher Fatigue Ratio1/2 (Fmax/Fmean) and thus fatigability in both sexes. LDH is an enzyme catalyzing the conversion of pyruvate to lactate and may indicate a preferential energy production via glycolysis rather than the more efficient oxidative phosphorylation. Diminished pyruvate dehydrogenase function is described in ME/CFS resulting in increased conversion of pyruvate to lactate [30]. Thus enhanced LDH may indicate diminished capacity of oxidative phosphorylation, which may well explain lower muscle strength during repeat exercise. Further we found that higher CK levels are associated with poorer Recovery Ratio and higher Fatigue Ratio2 in women. CK plays a central role in the energy supply of the muscle and muscular strain can increase the serum concentration of CK, although there are inter-individual differences [31]. A previous study found that CK concentrations are lower in patients with severe ME/CFS [32, 33]. This is not in contrast to our study as CK was analyzed after exertion in our study.

The pathomechanism of muscular fatigue and fatigability in ME/CFS is not fully elucidated yet. Histologic alterations with an increase in the more fatigue-prone, energetically expensive fast fibre type was described in muscle biopsies from ME/CFS patients, while contractile properties of muscle fibres were preserved [34]. Further metabolic alterations with altered expression of genes for mitochondrial and energy function were described [35]. Another study reported impaired glucose uptake and adenosine monophosphate activated protein kinase (AMPK) activity in cultured muscle cells from ME/CFS patients [36]. Fluge et al. showed that myoblasts grown in presence of serum from patients with severe ME/CFS showed increased mitochondrial respiration and excessive lactate secretion indicating impaired pyruvate dehydrogenase function [30]. Impaired oxygen supply to muscles upon exertion in ME/CFS was described, too. ME/CFS patients showed evidence of reduced hyperemic flow and reduced oxygen delivery [37]. In line with this hypoperfusion in cerebral vessels was recently shown [38]. A MRI study revealed that patients with ME/CFS have abnormalities in recovery of intramuscular pH following exercise which is related to autonomic dysfunction [39]. Paradox vasoconstriction due to ß2 adrenergic dysfunction resulting in muscle hypoperfusion is considered as an important pathomechanism in ME/CFS [4]. In an own study we observed disease severity to correlate with endothelial dysfunction in ME/CFS [40]. In line with this concept, we observed here a strong correlation between vasomotor dysregulation assessed by COMPASS questionnaire with Fmax and Fmean of repeat testing.

A limitation of our study is that HGS may be influenced by inactivity although much less than leg muscle strength [41]. Further HGS is associated with age. Thus, a control group of physically inactive HC closely matched by age would be best for defining normal values of HGS parameters.

Conclusion

HGS measurement is a simple diagnostic tool to assess the severity of muscle fatigue in ME/CFS. Repeat HGS assessment further allows to objectively assess fatigability and impaired recovery. Advantages of HGS measurement are easy handling, low cost and the low risk of causing PEM. Thus, it can be implemented easily in both primary care and research as an objective outcome parameter in clinical studies and drug development.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1. Figure S1 Correlations in male ME/CFS patients. All relevant correlations of HGS measurements with other clinical parameters with p<0.005(Pearson and Spearman correlation coefficients, respectively). Line shows linear regression in Pearson correlations.

Additional file 2. Figure S2 Correlations in female ME/CFS patients. All relevant correlations of HGS measurements with other clinical parameters with p < 0.005 (Pearson and Spearman correlation coefficients, respectively). Line shows linear regression in Pearson correlations.

Additional file 3. Figure S3 Fmean2 and cutoff value Distinguishing between 20 – 39-year-old ME/CFS patients and HC using cut off values (dotted line) of Fmean2 determined by ROC analysis. Left:females (circles: ME/CFS, n=20, squares: HC, n=16), right: males (circles: ME/CFS, n=20, squares: HC, n=17).

Additional file 4. Table S1. Correlations of clinical parameters with HGS and HGS ratios. Pearson (lin) or Spearman (non-lin) correlation coefficients were calculated. Bold: significant correlations with p < 0.05.

Additional file 5. Table S2. Results of ROC-Analysis for females and males aged 40-59 years. ME/CFS patients (females n=35, males n=21) and HC (females n=18, males n=10). Bold: most distinct parameter.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the patients who agreed to participate in the study.

Abbreviations

- AMPK

Adenosine monophosphate activated protein kinase

- ANOVA

Analysis of variance

- AUC

Area under curve

- BMI

Body mass index

- CCC

Canadian consensus criteria

- CDC

Center of disease control

- CFS

Chronic fatigue syndrome

- CK

Creatine kinase

- CPET

Cardiopulmonary exercise testing

- CRF

Cancer related fatigue

- HC

Healthy controls

- HGS

Handgrip strength

- LDH

Lactic dehydrogenase

- ME

Myalgic encephalomyelitis

- MS

Multiple sclerosis

- NIH

National Institutes of Health

- PEM

Post-exertional malaise

- QS

Quadriceps strength

- ROC

Receiver operating characteristic

- SD

Standard deviation

Authors' contributions

BJ conducted the HGS measurements, collected and analyzed and interpreted the data and was a major contributor in visualization and writing the manuscript. CK, PG and KW relevantly contributed to the investigation process by conducting the consultation, diagnosing, and inclusion of patients and data assessment. ST was responsible for project administration and data collection. ST performed HGS measurements. NS conducted the QS measurements, analyzed and interpreted the data and contributed to write the manuscript. NS and WD conceptualized and administered QS experiments. CS and HF conceptualized the research project, supervised and were major contributors in writing the manuscript. Additionally, CS executed project administration and funding acquisition. HF performed data curation, validation, analysis and visualization of results. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This investigation was funded by the Weidenhammer Zöbele foundation.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its Additional files.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All participants were informed in advance and gave their written consent. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Charité (EA2/038/14 from 12th Aug 2015) and the data protection regulations were followed.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Grabowski P, Scheibenbogen C. 464e Chronisches Fatigue Syndrom. In: Suttorp N, Möckel M, Siegmund B, al e, editors. Harrisons Innere Medizin. 19. Berlin: ABW Wissenschaftsverlag GmbH; 2016.

- 2.Grabowski P, Scheibenbogen C. Das Chronische Fatigue Syndrom - eine unterschätzte Erkrankung. Forum Sanitas. 2018;3:36–38. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mateo LJ, Chu L, Stevens S, Stevens J, Snell CR, Davenport T, et al. Post-exertional symptoms distinguish myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome subjects from healthy controls. Work (Reading, Mass). 2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Wirth K, Scheibenbogen C. A Unifying Hypothesis of the Pathophysiology of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS): Recognitions from the finding of autoantibodies against ß2-adrenergic receptors. (1873–0183 (Electronic)). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Carruthers B, Jain A, De Meirleir K, al. Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. J Chronic Fatig Syndr. 2003;11:178.

- 6.Speight N. Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: Review of history, clinical features, and controversies. Saudi J Med Med Sci. 2013;1(1):11–13. doi: 10.4103/1658-631X.112905. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nelson MJ, Buckley JD, Thomson RL, Clark D, Kwiatek R, Davison K. Diagnostic sensitivity of 2-day cardiopulmonary exercise testing in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. J Transl Med. 2019;17(1):80. doi: 10.1186/s12967-019-1836-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hodges LD, Nielsen T, Baken D. Physiological measures in participants with chronic fatigue syndrome, multiple sclerosis and healthy controls following repeated exercise: a pilot study. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging. 2018;38(4):639–644. doi: 10.1111/cpf.12460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bohannon RW. Muscle strength: clinical and prognostic value of hand-grip dynamometry. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2015;18(5):465–470. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0000000000000202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meeus M, Ickmans K, Struyf F, Kos D, Lambrecht L, Willekens B, et al. What is in a name? Comparing diagnostic criteria for chronic fatigue syndrome with or without fibromyalgia. Clin Rheumatol. 2016;35(1):191–203. doi: 10.1007/s10067-014-2793-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nacul LC, Mudie K, Kingdon CC, Clark TG, Lacerda EM. Hand grip strength as a clinical biomarker for ME/CFS and disease severity. Front Neurol. 2018;9:992. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2018.00992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neu D, Mairesse O, Montana X, Gilson M, Corazza F, Lefevre N, et al. Dimensions of pure chronic fatigue: psychophysical, cognitive and biological correlates in the chronic fatigue syndrome. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2014;114(9):1841–1851. doi: 10.1007/s00421-014-2910-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jammes Y, Stavris C, Charpin C, Rebaudet S, Lagrange G, Retornaz F. Maximal handgrip strength can predict maximal physical performance in patients with chronic fatigue. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 2020;73:162–165. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2020.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paul L, Wood L, Behan WM, Maclaren WM. Demonstration of delayed recovery from fatiguing exercise in chronic fatigue syndrome. Eur J Neurol. 1999;6(1):63–69. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-1331.1999.610063.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gibson H, Carroll N, Clague JE, Edwards RH. Exercise performance and fatiguability in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1993;56(9):993–998. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.56.9.993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cella D, Davis K, Breitbart W, Curt G, Coalition F. Cancer-related fatigue: prevalence of proposed diagnostic criteria in a united states sample of cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(14):3385–91. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.14.3385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Doehner W, Turhan G, Leyva F, Rauchhaus M, Sandek A, Jankowska EA, et al. Skeletal muscle weakness is related to insulin resistance in patients with chronic heart failure. ESC Heart Failure. 2015;2(2):85–89. doi: 10.1002/ehf2.12035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cicoira M, Bolger AP, Doehner W, Rauchhaus M, Davos C, Sharma R, et al. High tumour necrosis factor-alpha levels are associated with exercise intolerance and neurohormonal activation in chronic heart failure patients. Cytokine. 2001;15(2):80–86. doi: 10.1006/cyto.2001.0918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bell DS. The doctor’s guide to chronic fatigue syndrome. Berlin: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company Reading; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ware JE., Jr SF-36 health survey update. Spine. 2000;25(24):3130–3139. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200012150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chalder T, Berelowitz G, Pawlikowska T, Watts L, Wessely S, Wright D, et al. Development of a fatigue scale. J Psychosom Res. 1993;37(2):147–153. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(93)90081-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sletten DM, Suarez GA, Low PA, Mandrekar J, Singer W. COMPASS 31: a refined and abbreviated composite autonomic symptom score. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87(12):1196–1201. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Newton JL, Okonkwo O, Sutcliffe K, Seth A, Shin J, Jones DE. Symptoms of autonomic dysfunction in chronic fatigue syndrome. QJM. 2007;100(8):519–526. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcm057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cotler J, Holtzman C, Dudun C, Jason LA. A brief questionnaire to assess post-exertional malaise. Diagnostics (Basel, Switzerland). 2018;8:3. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics8030066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fluge O, Risa K, Lunde S, Alme K, Rekeland IG, Sapkota D, et al. B-lymphocyte depletion in myalgic encephalopathy/chronic fatigue syndrome. An open-label phase II study with rituximab maintenance treatment. PloS one. 2015;10(7):e0129898. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scheibenbogen C, Loebel M, Freitag H, Krueger A, Bauer S, Antelmann M, et al. Immunoadsorption to remove ss2 adrenergic receptor antibodies in chronic fatigue syndrome CFS/ME. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(3):e0193672. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0193672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fukuda K, Straus SE, Hickie I, Sharpe MC, Dobbins JG, Komaroff A. The chronic fatigue syndrome: a comprehensive approach to its definition and study. International Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Study Group. Ann Intern Med. 1994;121(12):953–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-121-12-199412150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ickmans K, Meeus M, De Kooning M, Lambrecht L, Nijs J. Recovery of upper limb muscle function in chronic fatigue syndrome with and without fibromyalgia. Eur J Clin Invest. 2014;44(2):153–159. doi: 10.1111/eci.12201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goudsmit EM, Nijs J, Jason LA, Wallman KE. Pacing as a strategy to improve energy management in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: a consensus document. Disabil Rehabil. 2012;34(13):1140–1147. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2011.635746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fluge O, Mella O, Bruland O, Risa K, Dyrstad SE, Alme K, et al. Metabolic profiling indicates impaired pyruvate dehydrogenase function in myalgic encephalopathy/chronic fatigue syndrome. JCI Insight. 2016;1(21):e89376. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.89376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kindermann W. Creatine Kinase Levels After Exercise. (1866–0452 (Electronic)). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Nacul L, de Barros B, Kingdon CC, Cliff JM, Clark TG, Mudie K, et al. Evidence of Clinical Pathology Abnormalities in People with Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) from an Analytic Cross-Sectional Study. LID - 10.3390/diagnostics9020041 [doi] LID - 41. 2019(2075–4418 (Print)). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Almenar-Pérez E, Sarría L, Nathanson L, Oltra EA-O. Assessing diagnostic value of microRNAs from peripheral blood mononuclear cells and extracellular vesicles in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. (2045–2322 (Electronic)). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Pietrangelo T, Toniolo L, Paoli A, Fulle S, Puglielli C, Fanò G, et al. Functional characterization of muscle fibres from patients with chronic fatigue syndrome: case-control study. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2009;22(2):427–436. doi: 10.1177/039463200902200219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pietrangelo T, Mancinelli R, Toniolo L, Montanari G, Vecchiet J, Fanò G, et al. Transcription profile analysis of vastus lateralis muscle from patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2009;22(3):795–807. doi: 10.1177/039463200902200326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brown AE, Dibnah B, Fisher E, Newton JL, Walker M. Pharmacological activation of AMPK and glucose uptake in cultured human skeletal muscle cells from patients with ME/CFS. Bioscience reports. 2018;38:3. doi: 10.1042/BSR20180242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McCully KK, Smith S, Rajaei S, Leigh JS, Natelson BH. Muscle metabolism with blood flow restriction in chronic fatigue syndrome. J Appl Physiol. 2004;96(3):871–8. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00141.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van Campen C, Rowe PC, Visser FC. Cerebral Blood Flow Is Reduced in Severe Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Patients During Mild Orthostatic Stress Testing: An Exploratory Study at 20 Degrees of Head-Up Tilt Testing. Healthcare (Basel, Switzerland). 2020;8:2. doi: 10.3390/healthcare8020169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jones DE, Hollingsworth KG, Taylor R, Blamire AM, Newton JL. Abnormalities in pH handling by peripheral muscle and potential regulation by the autonomic nervous system in chronic fatigue syndrome. J Intern Med. 2010;267(4):394–401. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2009.02160.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Scherbakov N, Szklarski M, Hartwig J, Sotzny F, Lorenz S, Meyer A, et al. Peripheral endothelial dysfunction in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. ESC Heart Failure. 2020;7(3):1064–1071. doi: 10.1002/ehf2.12633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Leblanc A, Pescatello LS, Taylor BA, Capizzi JA, Clarkson PM, Michael White C, et al. Relationships between physical activity and muscular strength among healthy adults across the lifespan. SpringerPlus. 2015;4:557. doi: 10.1186/s40064-015-1357-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1. Figure S1 Correlations in male ME/CFS patients. All relevant correlations of HGS measurements with other clinical parameters with p<0.005(Pearson and Spearman correlation coefficients, respectively). Line shows linear regression in Pearson correlations.

Additional file 2. Figure S2 Correlations in female ME/CFS patients. All relevant correlations of HGS measurements with other clinical parameters with p < 0.005 (Pearson and Spearman correlation coefficients, respectively). Line shows linear regression in Pearson correlations.

Additional file 3. Figure S3 Fmean2 and cutoff value Distinguishing between 20 – 39-year-old ME/CFS patients and HC using cut off values (dotted line) of Fmean2 determined by ROC analysis. Left:females (circles: ME/CFS, n=20, squares: HC, n=16), right: males (circles: ME/CFS, n=20, squares: HC, n=17).

Additional file 4. Table S1. Correlations of clinical parameters with HGS and HGS ratios. Pearson (lin) or Spearman (non-lin) correlation coefficients were calculated. Bold: significant correlations with p < 0.05.

Additional file 5. Table S2. Results of ROC-Analysis for females and males aged 40-59 years. ME/CFS patients (females n=35, males n=21) and HC (females n=18, males n=10). Bold: most distinct parameter.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its Additional files.