Abstract

Background

The rapid and widespread evolution of insecticide resistance has emerged as one of the major challenges facing malaria control programs in sub-Saharan Africa. Understanding the insecticide resistance status of mosquito populations and the underlying mechanisms of insecticide resistance can inform the development of effective and site-specific strategies for resistance prevention and management. The aim of this study was to investigate the insecticide resistance status of Anopheles gambiae (s.l.) mosquitoes from coastal Kenya.

Methods

Anopheles gambiae (s.l.) larvae sampled from eight study sites were reared to adulthood in the insectary, and 3- to 5-day-old non-blood-fed females were tested for susceptibility to permethrin, deltamethrin, dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT), fenitrothion and bendiocarb using the standard World Health Organization protocol. PCR amplification of rDNA intergenic spacers was used to identify sibling species of the An. gambiae complex. The An. gambiae (s.l.) females were further genotyped for the presence of the L1014S and L1014F knockdown resistance (kdr) mutations by real-time PCR.

Results

Anopheles arabiensis was the dominant species, accounting for 95.2% of the total collection, followed by An. gambiae (s.s.), accounting for 4.8%. Anopheles gambiae (s.l.) mosquitoes were resistant to deltamethrin, permethrin and fenitrothion but not to bendiocarb and DDT. The L1014S kdr point mutation was detected only in An. gambiae (s.s.), at a low allelic frequency of 3.33%, and the 1014F kdr mutation was not detected in either An. gambiae (s.s.) or An. arabiensis.

Conclusion

The findings of this study demonstrate phenotypic resistance to pyrethroids and organophosphates and a low level of the L1014S kdr point mutation that may partly be responsible for resistance to pyrethroids. This knowledge may inform the development of insecticide resistance management strategies along the Kenyan Coast.

Keywords: Anopheles, Insecticide resistance, Kdr, Sodium channel, Coastal Kenya

Background

Malaria is a devastating parasitic disease transmitted by Anopheles mosquitoes. Africa bears the heaviest burden of malaria due to presence there of the most virulent malaria parasite, Plasmodium falciparum, and the most efficient vectors, Anopheles gambiae (s.s.) and An. funestus (s.s.) [1]. Although malaria continues to be a leading cause of mortality in Africa, sustained vector control interventions based on indoor residual spraying (IRS) and long-lasting insecticide-treated nets (LLINs) have contributed to a remarkable decline in malaria-related mortality over the last two decades [2]. Until recently, pyrethroid insecticides were the only class of insecticides approved for use in LLINs, and these pesticides are also commonly used in IRS along with carbamates, organophosphates and organochlorines. Unfortunately, the development of resistance of malaria vectors to these insecticide classes has become a major global threat to their long-term use in the fight against malaria [3–12].

In Kenya, IRS is reserved for small-scale sporadic spraying during epidemics, and this management strategy has only been implemented in the western region of the country [13, 14]. The main insecticide used to supplement deltamethrin (a pyrethroid ester insecticide) in IRS is pirimiphos-methyl (Actellic 300CS; Syngenta Group, Basel, Switzerland), an organophosphate [15]. These insecticides are also used to control agricultural and urban pests, thereby exposing the mosquitoes to persistent selection pressure that eventually results in the selection for insecticide resistance.

Knockdown resistance (kdr) mutations involving the substitution of leucine by serine (L1014S) or phenylalanine (L1014F) at amino acid position 1014 is the main mechanism of resistance to pyrethroids in malaria vectors [16], although metabolic enzymes have also been known to play a role in resistance to pyrethroids [17, 18]. Earlier studies reported that the L1014S mutation was restricted to East Africa while the L1014F mutation was widely distributed in West and Central Africa [19]. However, recent studies have shown that both the L1014S and L1014F kdr mutations co-exist in East and West Africa [20, 21]. Conversely, resistance to carbamates and organophosphates results from overexpression of non-specific esterase enzymes and/or alteration of acetylcholinesterase (AChE) due to a single glycine to serine amino acid substitution at position 119 of the AChE gene [22, 23].

Defining the prevalence of insecticide resistance in malaria vectors and the underlying mechanism(s) of resistance in different ecological settings is necessary for the development of rational strategies for insecticide use and resistance management. The objective of this study was to investigate the resistance status of An. gambiae (s.l.) and elucidate the kdr mutation in coastal Kenya. Historically, An. gambiae (s.s.) and An. funestus were the main vectors of malaria in coastal Kenya, but the widespread use of LLINs has led to a major shift in malaria vectors in favor of An. arabiensis, an exophilic mosquito species that has had less contact with LLINs [24–28]. Recent reports in Kilifi county [25] and the neighboring Kwale county [26, 27] have revealed a low frequency of both the kdr allele and pyrethroid phenotypic resistance in this region. In addition, malaria is endemic in Kilifi county, with 91% of households having reported possessing at least one LLIN and 51% having universal ITN coverage achieving the proposed target of ≤ 2 people per LLIN [29]. The findings of this study will provide critical knowledge that may contribute to improved strategies for malaria control in Africa.

Methods

Study area

This study was conducted in Kilifi county, located along the north coast of Kenya. The county is situated north and northeast of Mombasa county, which also has a coastline on the Indian Ocean, with Taita Taveta county to the west, Tana River county to the east and Kwale county to the southwest. Kilifi county covers an approximate area of 12,246 km2, and the population at risk of malaria and other mosquito-borne diseases is approximately 1.5 million [30]. The study sites have been described in detail elsewhere [24, 31]. Anopheles gambiae (s.l.) and An. funestus (s.l.) are the key malaria vectors in the area. They occur throughout the year, with peak occurrence during the rainy season [24]. Coastal Kenya usually experiences two rainy seasons each year: short rains falling from October to November and long rains from April to July. The mean annual rainfall ranges between 300 mm in the hinterland and 1300 mm in the coastal belt. The mean daily temperature varies from 21 °C to 30 °C [32].

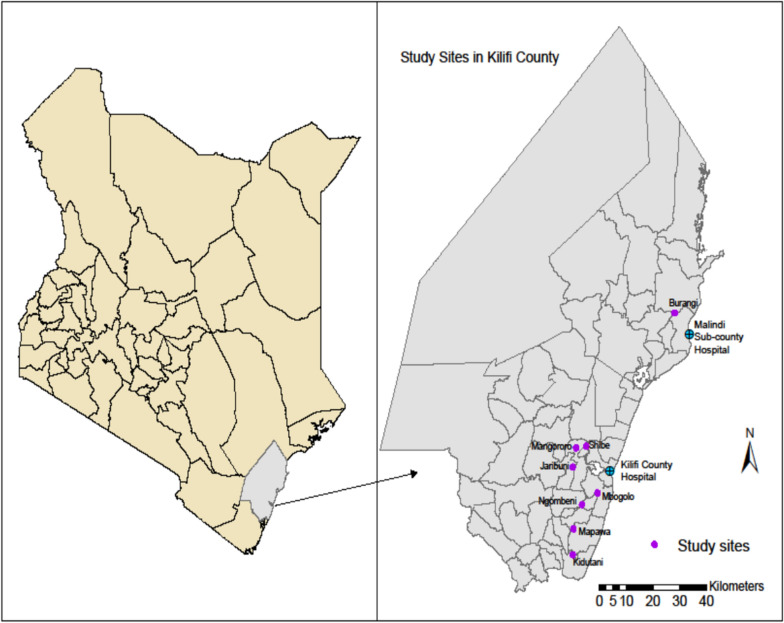

Larval mosquito sampling was carried out in eight randomly selected study sites (Fig. 1), of which seven were in Kilifi subcounty, namely Ngombeni (3.73208°S, 39.76491°E), Mbogolo (3.69806°S, 39.81706°E), Jaribuni (3.62054°S, 39.73354°E), Kidutani (3.88209°S, 39.71819°E), Shibe (3.55840°S, 39.77921°E), Mapawa (3.80452°S, 39.73641°E) and Mangororo (3.56366°S, 39.74507°E), and one, Burangi (3.09828°S, 40.04817°E), was in Malindi subcounty.

Fig. 1.

Map of Kenya and Kilifi county showing the study sites location

Selection of the study sites was based on high coverage with LLINs, and abundance and ease of accessibility to mosquito breeding sites.

Larval mosquito collection, transportation and rearing

Larval mosquito collections were done in June (during long rains), August (dry season) and November (short rains) 2013 and in July 2014 (immediately after the long rains). The collections were spread across the various seasons to maximize the collection of the different malaria vectors in the study sites. Larvae were sampled from stagnant water bodies selected in each study site using the standard dipping technique [33]. In each study site, six larval habitats were sampled once per week. The habitats included sand pits, ponds, roadside ditches, marshes, shallow wells and river banks. Anopheline larvae were transferred into Whirl-pak® bags (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and transported to the insectary at Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI), Center for Geographic Medicine Research, Coast Kilifi.

Tetramin® (Tetra Werke, Melle, Germany) baby fish food was used as the larval rearing diet. The insectary was maintained at a constant temperature of 25–27 °C and relative humidity of 74–82%. The larval pans were monitored daily, and the collected pupae transferred into plastic cups in emergence cages. Newly emerged adults (F0) were identified using morphological characteristics [34]. The adults were then kept as same-age cohorts for insecticide susceptibility testing.

World Health Organization susceptibility bioassay tests

Non-blood-fed female An. gambiae (s.l.) aged between 3 and 5 days and reared from field-collected larvae were used in the susceptibility bioassays. Each insecticide susceptibility test was performed using 25 mosquitoes in four replicates and two controls. The insecticides used and their concentrations included deltamethrin (0.05%), permethrin (0.75%), dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT, 4%), fenitrothion (1%) and bendiocarb (0.1%), prepared at Universiti Sains Malaysia [35]. The negative control included 25 mosquitoes collected from each study site and exposed to untreated filter papers. In addition, laboratory-raised, susceptible An. gambiae (s.s) Kisumu strain were exposed to insecticide-treated filter papers as a measure of quality assurance. The knockdown time (KDT) of each insecticide was recorded every 10 min for 1 h. Mosquitoes were then moved to a recovery tube and provided with 10% sucrose. Final mortality was recorded after 24 h.

After recording mortality at 24 h post-exposure, those mosquitoes still alive were killed by freezing and together with a 20% randomly selected subset of the dead samples per study site stored individually in labeled Eppendorf tubes (Eppendorf Co., Hamburg, Germany). The specimens were then preserved at − 80 °C for later molecular analysis.

DNA extraction and species identification

Genomic DNA was extracted from the whole body of the An. gambiae (s.l.) using an ethanol precipitation method [36]. Conventional PCR amplification of ribosomal DNA intergenic spacers was used to differentiate the sibling species of the An. gambiae complex [37].

Detection of kdr genotype mutations

Knockdown resistance was tested using 192 mosquitoes (59 alive and 133 dead) after performing the pyrethroid insecticide susceptibility tests; 20 An. gambiae (s.s.) Kisumu strain were used as controls. Both the L1014S (leucine to serine substitution) kdr allele originally detected in East Africa [16] and the L1014F (leucine to phenylalanine substitution) kdr allele from West Africa [19] were tested. Real-time PCR was used to determine the genotype at amino acid position 1014 of the voltage-gated sodium channel, following the methods of Bass et al. [38] as modified by Mathias et al. [39]. Each PCR reaction was conducted in a 10-µl volume containing 5.0 µl 2× TaqMan mix (TaqMan® Gene expression Master Mix [Thermo Fisher Scientific), 0.5 µl of forward primer, 0.5 µl reverse primer [for either kdr-east or kdr-west], 0.4 µl of each probe, 1.0 µl of template DNA and 2.6 µl of PCR grade water [ddH2O]). Samples were genotyped for the wild-type (susceptible) allele using the probe 5′-CTTACGACTAAATTTC-3′ and for the L1014S kdr allele using the probe 5′-ACGACTGAATTTC-3′. The primer sequences used for this study were 5′-CATTTTTCTTGGCCACTGTAGTGA-3′ (forward) and 5′-CGATCTTGGCCATGTTAATTTGCA-3′ (reverse). Controls loaded in the last four wells of the 96-well PCR plate included FAM (fluorescent label)-positive control, HEX (fluorescent label)-negative control, non-template control (NTC) and buffer. The PCR was carried out in a Strategene® MxPro 3000 Real-Time PCR system (Strategene, Agilent Technologies, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA) at the following temperature profile: an initial denaturation step at 95 °C, 10 min; followed by 92 °C (for kdr-east) or 95 °C (for kdr-west)/15 s, 60 °C/1 min, for 40 cycles; with a final extension step at 72 °C for 10 s.

Data analysis

Resistance was obtained using the World Health Organization criteria, with mortality rates of 98–100% indicating susceptibility, 90–97% suggesting possible resistance that needs further investigation and ≤ 90% indicating resistance, respectively [35]. KDT50 and KDT95 (time [in minutes] to knock down 50 and 95% of mosquitoes, respectively) were estimated using probit analysis [40]. A post-hoc comparison test with the Bonferroni correction test was performed to compare the proportions of each mosquito species among the study sites. The scatter-plots were retrieved to assess the kdr mutation and the frequency of the resistance allele determined from endpoint fluorescence using the MxPro software (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Final data were captured in Microsoft Excel 2010 (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, USA) and analyzed using the R statistical package, version 3.3.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Sample size and species composition

A total of 3683 An. gambiae (s.l.) adult females were collected as larvae and used for the susceptibility bioassays from the eight villages: Jaribuni (500), Shibe (500), Kidutani (475), Ng’ombeni (490), Mapawa (475), Mbogolo (455), Burangi (500) and Mangororo (288). PCR analyses showed that An. arabiensis (91.49%) and An. gambiae (s.s) (5.02%) were the only sibling species of An. gambiae (s.l.). No amplification occurred in the remaining 3.49% of samples (Table 1). Mosquitoes from Mangororo, Shibe and Mbogolo were predominantly An. arabiensis (Mangororo: 100%; Shibe: 96.8%; Mbogolo: 99.01%). A post hoc comparison test with Bonferroni correction revealed that the proportions of An. gambiae (s.s) and An. arabiensis species among the study sites were significant (Z = − 3.31, P = 0.001). No An. funestus were collected in this study.

Table 1.

Proportions of Anopheles gambiae (s.s) and An. arabiensis in the eight study sites, Kilifi county

| Study site | n | An. gambiae (s.s) | An. arabiensis | Not amplified |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jaribuni | 172 | 12 (6.98%) | 148 (86.04%) | 12 (6.98%) |

| Kidutani | 124 | 6 (4.84%) | 114 (91.94%) | 4(4.00%) |

| Mbogolo | 101 | 0 (0.00%) | 100 (99.01%) | 1 (0.99%) |

| Ngombeni | 123 | 18 (14.63%) | 102 (82.93%) | 3 (2.44%) |

| Shibe | 124 | 0 (0.00%) | 120 (96.77%) | 4 (3.23%) |

| Mapawa | 108 | 5 (4.63%) | 95 (87.96%) | 8 (7.41%) |

| Burangi | 163 | 8 (4.91%) | 153 (93.86%) | 2 (1.23%) |

| Mangororo | 60 | 0 (0.00%) | 60 (100%) | 0 (0.00%) |

| Total | 975 | 49 (5.02%) | 892 (91.49%) | 34 (3.49%) |

n, Number of An. gambiae (s.l.) processed for species identification

Insecticide susceptibility bioassays

Anopheles gambiae (s.s) Kisumu strain were susceptible to all of the insecticides tested (deltamethrin, permethrin, DDT, bendiocarb and fenitrothion) with 100% mortality. The negative control did not show any mortality; therefore, Abbott’s formula was inapplicable to correct for the natural causes of mortality in this study.

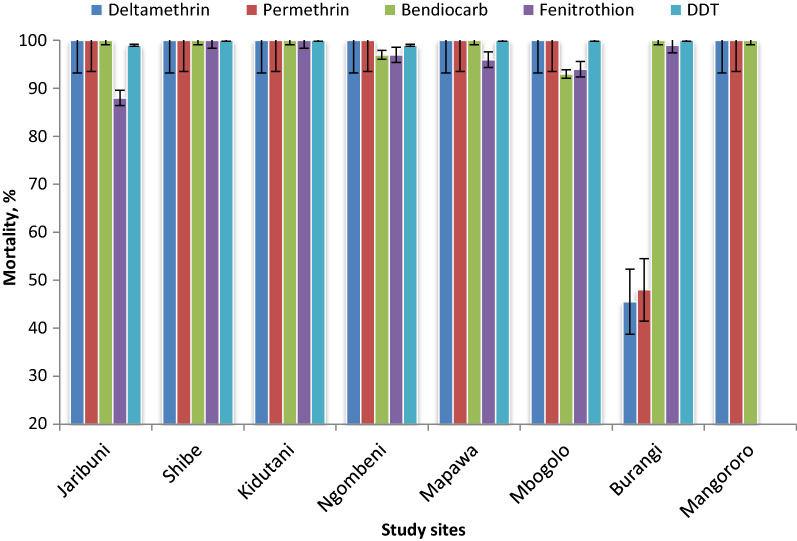

Figure 2 shows the bioassay susceptibility status of An. gambiae (s.l.) to the different insecticides used in this study. Deltamethrin resistance in An. gambiae (s.l.) was only recorded in one of the eight study sites (Burangi: n = 100, mortality 45.5%). Coincidentally, permethrin resistance was also reported in the same study site (n = 100, mortality 48%). However, full susceptibility to both permethrin and deltamethrin in An. gambiae (s.l.) was indicated in all of the other study sites (mortality 100%). The An. gambiae (s.l.) populations tested indicated full susceptibility to DDT (n = 750, mortality range 99–100%) in the seven study sites tested.

Fig. 2.

Results of bioassay tests of female Anopheles from eight study sites exposed to various insecticides. DDT Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane

Adult mosquitoes were resistant to fenitrothion in Jaribuni (n = 100, mortality 88%) and showed possible resistance at Ngombeni, Mapawa and Mbogolo with a test mortality range of 94–97%. However, mosquitoes from Burangi, Kidutani and Shibe indicated full susceptibility to fenitrothion. The mosquitoes tested were highly susceptible to bendiocarb in six of the eight study sites, i.e. Jaribuni, Shibe, Kidutani, Mangororo, Burangi and Mapawa, with test mortality of 100%. However, the possibility of resistance that requires further investigation was recorded against bendiocarb in Mbogolo (n = 75, mortality 93%) and Ng’ombeni (n = 90, mortality 97%).

Knockdown time (KDT50) at 95% CI and KDT50 ratio

Most of the knockdown resistance ratios (KDT50 ratio: KDT50 of the test population to that of the control [Kisumu strain]) were within the An. gambiae (s.s.) Kisumu strain susceptible range of 1.0 to 1.7 and varied among study sites, as indicated in Table 2. The KDT50 ratio for deltamethrin could not be determined in Burangi due to the high resistance levels. However, in the other study sites, the KDT50 ratio was 1.1–1.9 fold compared to Kisumu strain. The mosquito population from Burangi also recorded resistance to permethrin with a KDT50 ratio of 3.3. The resistance ratio indicated potential resistance to permethrin in Kidutani (KDT50 ratio: 2.0) which requires further investigation. The KDT50 ratio was 1.0- to 1.7-fold in the remaining six study sites: Jaribuni, Shibe, Ngombeni, Mapawa, Mbogolo and Mangororo.

Table 2.

Knockdown resistance ratio of mosquito populations (An. gambiae [s.l.]) to different insecticides

| Insecticide | Population | KDT50 (in min) | 95% CI | KDT50 ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deltamethrin | Jaribuni | 18 | 40.9–55.2 | 1.1 |

| Shibe | 16 | 43.9–58.1 | 0.9 | |

| Kidutani | 18 | 42.9–57.3 | 1.1 | |

| Ngombeni | 23 | 41.9–56.2 | 1.4 | |

| Mapawa | 32 | 40.8–61.1 | 1.9 | |

| Mbogolo | 25 | 39.8–60.2 | 1.5 | |

| Burangi | –a | –a | –a | |

| Mangororo | 30 | 39.8–60.2 | 1.8 | |

| Permethrin | Jaribuni | 18 | 39.9–60.2 | 1.0 |

| Shibe | 21.5 | 37.9–58.2 | 1.2 | |

| Kidutani | 35.5 | 38.9–59.2 | 2.0 | |

| Ngombeni | 30 | 40.8–61.1 | 1.7 | |

| Mapawa | 20 | 39.8–60.2 | 1.1 | |

| Mbogolo | 27 | 38.9–59.2 | 1.5 | |

| Burangi | 60 | 37.9–58.2 | 3.3 | |

| Mangororo | 30 | 39.8–60.2 | 1.7 | |

| Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT) | Jaribuni | 30.5 | 40.9–55.2 | 2.1 |

| Shibe | 15 | 37.9–58.2 | 1.0 | |

| Kidutani | 18 | 39.8–60.2 | 1.2 | |

| Ngombeni | 27.3 | 39.8–60.2 | 1.9 | |

| Mapawa | 31.5 | 39.8–60.2 | 2.2 | |

| Mbogolo | 25 | 39.8–60.2 | 1.7 | |

| Burangi | 24.4 | 36.9–57.2 | 1.7 | |

| Bendiocarb | Jaribuni | 19.2 | 43.9–58.1 | 1.0 |

| Shibe | 19.3 | 39.8–60.2 | 1.0 | |

| Kidutani | 22 | 39.8–60.2 | 1.2 | |

| Ngombeni | 26.9 | 39.8–60.2 | 1.4 | |

| Mapawa | 30 | 39.8–60.2 | 1.6 | |

| Mbogolo | 23 | 37.9–58.2 | 1.2 | |

| Burangi | 24 | 37.9–58.2 | 1.3 | |

| Mangororo | 30 | 40.8–61.1 | 1.6 | |

| Fenitrothion | Jaribuni | 46 | 37.9–58.1 | 2.1 |

| Shibe | 23.5 | 39.8–609.2 | 1.1 | |

| Kidutani | 40 | 42.8–63.1 | 1.9 | |

| Ngombeni | 31 | 38.9–59.2 | 1.5 | |

| Mapawa | 21.5 | 37.9–58.2 | 1.0 | |

| Mbogolo | 46.3 | 37.9–58.2 | 2.2 | |

| Burangi | 36 | 36.9–57.2 | 1.7 |

CI, Confidence interval; KDT50, time taken for 50% of the test population to be knocked down; KDT50 ratio, KDT50 of the test population to that of the control (Kisumu strain)

aLower limit estimation not possible due to a large g value [40]

The KDT50 ratio for DDT, fenitrothion and bendiocarb compared to that for the Kisumu strain ranged from 1.1- to 2.2-fold in all the study sites. The mosquitoes were susceptible to bendiocarb in all the study sites (KDT50 ratio 1.0–1.6). Possible resistance was recorded in Jaribuni for both DDT (KDT50 ratio 2.2) and fenitrothion (KDT50 ratio 2.1). The KDT50 ratio for both DDT and fenitrothion was 2.2 in both Mbogolo and Mapawa, indicating possible resistance.

Knockdown resistance status

A total of 192 randomly selected samples comprising of An. arabiensis, An. gambiae (s.s.) and Kisumu strain were genotyped for the kdr mutation. Neither L1014F nor L1014S kdr allelic genes were observed in An. arabiensis species. The kdr allelic frequency in An. gambiae, An. arabiensis and An. gambiae (s.s.) populations is shown in Table 3. Upon exposure to pyrethroids for 24 h, a total of 15 An. gambiae, An. arabiensis and An. gambiae (s.s.) were identified with the resistant phenotype, while 34 had the susceptible phenotype. L1014S allelic genes were identified in only four Anopheles gambiae, An. arabiensis and An. gambiae (s.s.), of which two were homozygous (RR) and two were heterozygous (RS) for the trait. Only one of the 15 phenotypically resistant mosquitoes was observed to be genotypically resistant; this mosquito was heterozygous for L1014S characteristic. The remaining An. gambiae, An. arabiensis and An. gambiae (s.s.). mosquitoes genotyped were recessive (SS).

Table 3.

Knockdown resistance allelic frequency in An. gambiae (s.s.) populations from Kilifi county, coastal Kenya

| Mosquito statusa | N | L1014S alleleb | Fc | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR | RS | SS | |||

| Resistant to pyrethroids | 15 | 0 | 1 | 14 | 0.0333 |

| Susceptible to pyrethroids | 34 | 2 | 1 | 33 | 0.0735 |

N, Number of mosquitoes genotyped

aResistant refers to mosquitoes alive after 24 h of exposure to pyrethroid pesticide; susceptible indicates dead mosquitoes after 24 h of exposure to pyrethroid pesticide

bL1014S allele: leucine to serine substitution knockdown resistance (kdr) allele. RR, Homozygous resistant allele; RS, heterozygous resistant allele; SS, susceptible allele

c F, kdr allele frequency

Discussion

This study has shown that Anopheles arabiensis is the most dominant species in the eight study sites sampled in Kilifi county. An earlier study reported that Anopheles gambiae (s.s.) was the dominant subspecies along the Kenyan coast and other regions of the country [24]. However, a shift in malaria vector composition has recently been documented that coincides with the scaling up of vector control interventions, especially the ongoing widespread use of insecticide-treated nets (ITNs) along the Kenyan coast [31]. The increase in populations of An. arabiensis and declining populations of An. gambiae (s.s.) may be a result of their contrasting ecological behavior. Anopheles gambiae (s.s.) has anthropophilic, endophagic and endophilic tendencies [41, 42]. This means relatively more hours spent indoors and, consequently, longer contact hours with LLINs, which may have contributed to its population decrease. In contrast, An. arabiensis is both exophilic and zoophilic [43–45], and this limits its contact with LLINs and the insecticides used for IRS [46]. The observed shift in species composition in favor of An. arabiensis calls for an integrated vector management (IVM) approach targeting both indoor and outdoor control of malaria vectors.

Mosquito populations from one of the eight study sites (Burangi) were resistant to both deltamethrin and permethrin and had high median KDT compared with the other study sites. These findings suggest that resistant genes are localized and that vector control management strategies should be established to prevent their spread and preserve the efficacy of the current vector control tools. Earlier studies along the Kenyan coast and neighboring Tanzania reported the presence of pyrethroid resistance characterized by a high median KDT and mortality levels ranging from 62.38 to 93% following pyrethroid exposure [25, 28, 47]. In some West African countries, such as Ivory Coast and Burkina Faso, pyrethroid resistance has been found to be much more intense, with high KDT50 ratios and mortality rates of ≤ 40% reported following exposure to pyrethroids [48–52]. High KDT50 values in the test populations indicate the presence of the kdr mechanism of resistance [53]. The high resistance levels might be attributed to selection for insecticide resistance due to increased use of LLINs in vector control programs [35, 54, 55]. Based on KDT50 values, we noted potential resistance to DDT in Jaribuni and Mapawa villages that might partly be linked to cross-resistance from pyrethroids [56] or the presence of recessive genes in the mosquito population [25]. These two insecticide classes (pyrethroids and organochlorines) have the same mode of action and thus pose a threat of cross-resistance.

Mosquito samples from Jaribuni were resistant to fenitrothion based on both mortality rate and the KDT50 ratio. In addition, potential resistance to both fenitrothion and bendiocarb was recorded in Mbogolo and Ngombeni. However, susceptibility to both fenitrothion and bendiocarb was detected in all other study sites. This resistance may be due to selection pressure resulting from the contamination of the larval habitats with carbamates and organophosphates used in agriculture [57] as well as exposure of adult mosquitoes to insecticides during either sugar-feeding or outdoor resting. Agricultural systems provide ideal habitats for mosquito breeding [27]. Earlier studies conducted in Kenya reported the use of fenitrothion and bendiocarb in agricultural settings and linked them to resistance [58, 59]. Fenitrothion (organophosphate) and bendiocarb (carbamate) have been proposed for IRS use to control pyrethroid-resistant mosquitoes [60]. Therefore, the evolution of resistance to these insecticides threatens their use in IRS and as substitute to pyrethroids in public health systems.

The occurrence of phenotypic resistance to pyrethroids (deltamethrin and permethrin) may indicate the presence of target site insensitivity. Our findings that no kdr alleles were detected in An. arabiensis are consistent with results from previous studies in western and coastal Kenya [28, 39], suggesting other underlying resistance mechanisms as the cause of phenotypic resistance. However, the L1014S kdr allele was detected in An. gambiae (s.s.) with an allelic frequency of 3.33% in the resistant test population. The low allelic frequency of the L1014S kdr gene is consistent with results reported in other studies in the neighboring Kwale county [26, 28]. In contrast, other studies have indicated a high frequency and wide distribution of the L1014S mutation in An. arabiensis in western Kenya [61, 62]. These variations in the frequency of the resistance allele may be either due to movement of the mutant genes from their original selection pressure region or DNA deletion in a given genome in a mosquito population [39, 63, 64]. Although target site resistance had been detected earlier in the neighboring Kwale county along the coastal Kenya, in practice this may not mean that the mutant genes originated from there. However, it is evident that the percentage allelic frequency is clearly increasing. Therefore, further studies are needed to ascertain the origin of the mutant genes and facilitate development of strategies to mitigate their rapid spread.

The low kdr allele frequency compared to the high phenotypic resistance observed in pyrethroids is indicative of other underlying resistance mechanisms. Indeed, metabolic-based resistance most likely plays a bigger role in insecticide resistance than target site resistance [65]. Several studies have documented the contribution of metabolic resistance enzymes in malaria vectors to pyrethroids, organophosphates and carbamates [4, 26, 62, 63, 66–68]. Knockdown resistance is considered to be a weak form of resistance compared to metabolic-based resistance. Therefore, vector control failure is likely when kdr occurs along with metabolic resistance [69]. Nevertheless, the increasing kdr allele frequency coupled with metabolic-based resistance reported in the neighboring Kwale county [28] focuses attention on the risk of subsequent failure of current vector control interventions in coastal Kenya. Therefore, further investigation on the evolution of insecticide resistance in An. gambiae (s.l.) in Kilifi county is vital.

Conclusions

This study reported phenotypic resistance to selected pyrethroids and organophosphate insecticides in malaria vectors along the Kenyan coast. The occurrence of the L1014S allele in An. gambiae (s.s.) at a low frequency was also documented. These findings highlight the need for regular entomological surveillance and monitoring of insecticide resistance and for investment in new vector control strategies that can supplement or even replace the use of synthetic insecticides. This effort may inform development and implementation of an IVM approach targeting all mosquito life stages with diverse vector control interventions to limit the spread of insecticide resistance and preserve the efficacy of existing insecticides.

Acknowledgements

We thank Martha Muturi and Joseph Nzovu for expert technical support and the staff of the Vector Biology Department, KEMRI, Kilifi, Kenya, for assistance with field collections. We also thank Christopher Nyundo for developing the map used in this manuscript. Mention of trade names and commercial products in this publication is solely for the purpose of providing specific information and does not imply recommendation or endorsement by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer.

Abbreviations

- AchE

Acetylcholinesterase

- ddH2O

PCR grade water

- DDT

Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane

- IRS

Indoor residual spraying

- ITN

Insecticide-treated net

- IVM

Integrated vector management

- KDT

Knockdown time

- kdr

Knockdown resistance

- LLINs

Long-lasting insecticide-treated nets

- NTC

Non-template control

Authors’ contributions

DNM, CMM, JMM and EK participated in the conception and design of the study. DNM carried out the field activities and bioassay tests. CMM, EK and JMM coordinated and supervised the study. EJM and DNM sequenced the samples. DNM analyzed the data and drafted the first manuscript. All authors critically revised and contributed to drafting the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported in part by the U.S Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, Government of Kenya through National Commission of Science, Technology and Innovation (Grant No. NCST/ST&I/RCD/4THCALL MSc/114) and the Biovision Foundation (Grant No. BV HH-07/2013-2015).

Availability of data and materials

All data generated and supporting the conclusions of this manuscript has been included in the article. Raw data and materials are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . World malaria report 2018. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization . World malaria report 2019. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Djogbénou L. Vector control methods against malaria and vector resistance to insecticides in Africa. Med Trop Rev Corps Sante Colon. 2009;69:160–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ranson H, N’Guessan R, Lines J, Moiroux N, Nkuni Z, Corbel V. Pyrethroid resistance in African Anopheline mosquitoes: what are the implications for malaria control? Trends Parasitol. 2011;27(2):91–98. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2010.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Silva APB, Santos JMM, Martins AJ. Mutations in the voltage-gated sodium channel gene of Anophelines and their association with resistance to pyrethroids—a review. Parasites Vectors. 2014;7:450. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-7-450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ranson H, Lissenden N. Insecticide resistance in African Anopheles mosquitoes: a worsening situation that needs urgent action to maintain malaria control. Trends Parasitol. 2016;32:187–196. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2015.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yewhalaw D, Kweka EJ. Insecticide resistance in East Africa—history, distribution and drawbacks on malaria vectors and disease control. Intech Open. 2016;10:5772–61570. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hancock PA, Hendrinks CJM, Tangena J-A, Gibson H, Hemingway J, Coleman M, et al. Mapping trends in insecticide resistance phenotypes in African malaria vectors. PLOS Biol. 2020;18(6):e30000633. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3000633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Riveron JM, Tchouakui M, Mugenzi L, Menza BD, Chiang M, Wondji CS. Insecticide resistance in malaria vectors: an update at global scale. 2018. 10.5772/intechopen.78375.

- 10.World Health Organization . Global plan for insecticide resistance management in malaria vectors. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization . World malaria report 2016. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moyes CL, Athinya DK, Seethaler T, Battle KE, Sinka M, Hadiet MP, et al. Evaluating insecticide resistance across African districts to aid malaria control decisions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2020;117(36):22042–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Division of Malaria Control, Ministry of Public Health and Sanitation, Kenya National Bureau of Statistics Division of Malaria Control. Kenya Malaria Indicator Survey (KMIS). 2010. https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/MIS7/MIS7.pdf. Accessed 28 Nov 2020.

- 14.The PMI Africa IRS (AIRS) Project, Kenya End of Spray Report 2017. Bethesda, MD. The PMI africa IRS (AIRS) project, Abt Associates Inc. 2017. https://www.pmi.gov/docs/default-source/default-document-library/implementing-partner-reports/kenya-2017-end-of-spray-report.pdf?sfvrsn=4. Accessed 4 Jan 2021.

- 15.Abong’o B, Gimning JE, Torr SJ. Impact of indoor residual spraying with pirimiphos-methyl (Actellic 300CS) on entomological indicators of transmission and malaria case burden in Migori county, western Kenya. Sci Rep. 2020;10:4518. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-61350-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ranson H, Jensen B, Vulule JM, Wang X, Hemingway J, Collins FH. Identification of a point mutation in the voltage–gated sodium channel gene of Kenyan Anopheles gambiae associated with resistance to DDT and pyrethroids. Insect Mol Biol. 2000;9(5):491–497. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2583.2000.00209.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Müller P, Chouaibou M, Pignatelli P, Etang J, Walker ED, Donnelly MJ, et al. Pyrethroid tolerance is associated with elevated expression of antioxidants and agricultural practice in Anopheles arabiensis sampled from an area of cotton fields in Northern Cameroon. Mol Ecol. 2008;17:1145–1155. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03617.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McLaughlin LA, et al. Characterization of inhibitors and substrates of Anopheles gambiae CYP6Z2. Insect Mol Biol. 2008;17:125–135. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2007.00788.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Santolamazza F, Calzetta M, Etang J, Barrese E, Dia I, Caccone A. Distribution of knockdown resistance mutations in Anopheles gambiae molecular forms in West and West-Central Africa. Malar J. 2008;7:74. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-7-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nwane P, Etang J, Chouaїbou M, et al. Kdr-based insecticide resistance in Anopheles gambiae s.s. populations in Cameroon; Spread of the L1014F and L1014S mutations. BMC Res Notes. 2011;4(1):463. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-4-463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kabula B, Kisinza W, Tungu P, Ndege C, Batengana B, Kollo D, et al. Co-occurrence and distribution of East (L1014S) and West (L1014F) African knock-down resistance in Anopheles gambiae sensu lato populations of Tanzania. Trop Med Int Health. 2014;19(3):331–341. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hemingway J, Ranson H. Insecticide resistance in insect vectors of human disease. Ann Rev Entomol. 2000;45:371–391. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.45.1.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weill M, Chandre F, Brengues C, Manguin S, Akogbeto M, Pasteur N, et al. The kdr mutation occurs in Mopti form of Anophelesgambiae s.s. through introgression. Insect Mol Biol. 2002;9(5):451–455. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2583.2000.00206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mbogo C, Mwangangi J, Nzovu J, Gu W, Yan G, Gunter JT, et al. Spatial and temporal heterogeneity of Anopheles mosquitoes and Plasmodium falciparum transmission along the Kenyan coast. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2003;68:734–742. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2003.68.734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Msami JE. Monitoring insecticide resistance among malaria vectors in Coastal Kenya. 2013. http://erepository.uonbi.ac.ke:8080/xmlui/handle/123456789/52382. Accessed 9 Dec 2020.

- 26.Orondo PW. Status and mechanisms of insecticide resistance in Anopheles mosquitoes from Mwea Sub-county and Kwale County and their malaria parasite infection rates. 2017. http://ir.jkuat.ac.ke/hdl.net/123456789/2647. Accessed 10 Dec 2020.

- 27.Ondeto BM, Nyundo C, Kamau L, Muriu SM, Mwangangi J, Njagi K, et al. Current status of insecticide resistance among malaria vectors in Kenya. Parasites Vectors. 2017;10:429. doi: 10.1186/s13071-017-2361-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kiuru CW, Oyieke FA, Mukabana WR, Mwangangi J, Kamau L, Muhia-matoke D. Status of insecticide resistance in malaria vectors in Kwale County, Coastal Kenya. Malar J. 2018;17:3. doi: 10.1186/s12936-017-2156-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.U.S President's Malaria Initiative. Kenya Malaria Operational Plan FY 2019. 2020. https://www.pmi.gov/docs/default-source/default-document-library/malaria-operational-plans/fy19/fy-2019-kenya-malaria-operational-plan.pdf. Accessed 16 Dec 2020.

- 30.Kenya National Bureau of Statistics . Economic survey, 2019. Nairobi: KNBS; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mwangangi JM, Mbogo CM, Orindi BO, Muturi EJ, Midega JT, Nzovu J, et al. Shifts in malaria vector species composition and transmission dynamics along the Kenyan coast over the past 20 years. Malar J. 2013;12(1):13. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-12-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mwangangi JM, Midega J, Kahindi S, Njoroge L, Nzovu J, Githure J, et al. Mosquito species abundance and diversity in Malindi, Kenya and their potential implication in pathogen transmission. Parasitol Res. 2012;110:61–71. doi: 10.1007/s00436-011-2449-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Service MW, editor. Medical entomology for students. Liverpool: Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine. 2004.

- 34.Gillies MT, Coetzee M. A supplement to the Anophelinae of Africa, South of Sahara. Johannesburg: South African Institute of Medical Research; 1987.

- 35.World Health Organization . Test procedures for insecticide resistance monitoring in malaria vector mosquitoes. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Collins FH, Mendez MA, Rasmussen MO, Mehaffey PC, Besansky NJ, Finnerty V. A ribosomal RNA gene probe differentiates member species of the Anopheles gambiae complex. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1987;37:37–41. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1987.37.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Scott JA, Brogdon WA, Collins FH. Identification of single specimens of the Anopheles gambiae complex by polymerase chain reaction. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1993;49:520–529. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1993.49.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bass C, Nikou D, Donnelly MJ, Williamson MS, Ranson H, Ball A, et al. Detection of knockdown resistance (kdr) mutations in Anopheles gambiae: a comparison of two new high-throughput assays with existing methods. Malar J. 2007;6:111. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-6-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mathias D, Ochomo EO, Atieli F, Ombok M, Bayoh MN. Spatial and temporal variation in the kdr allele L1014S in Anopheles gambiae s.s. and phenotypic variability in susceptibility to insecticides in western Kenya. Malar J. 2011;10:10. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-10-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Finney DJ. Probit analysis. 3. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bayoh MN, Mathias DK, Odiere MR, Mutuku FM, Kamau L, Gimnig JE, et al. Anopheles gambiae: Historical population decline associated with regional distribution of insecticide-treated bed nets in western Nyanza province, Kenya. Malar J. 2014;9:62. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-9-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Degefa T, Yewhalaw D, Zhou G, Lee MC, Atieli H, Githeko AK, et al. Indoor and outdoor malaria vector surveillance in western Kenya. Implications for better understanding of residual transmission. Malar J. 2017;16:443. doi: 10.1186/s12936-017-2098-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mnzava AE, Rwegishora RT, Wilkes TJ, Tanner M, Curtis CF. Anopheles arabiensis and An. gambiae chromosomal inversion polymorphism, feeding and resting behavior in relation to insecticide house spraying in Tanzania. J Med Vet Entomol. 1995;9:316–324. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2915.1995.tb00140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kitau J, Oxborough RM, Tungu PK, Matowo J, Malima RS, Magesa SM, et al. Species shifts in the Anopheles gambiae complex: do LLINs successfully control Anopheles arabiensis? PLoS ONE. 2012;21:e31481. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Asale A, Duchateau L, Yewhalaw D, et al. Zooprophylaxis as a control by the vector Anopheles arabiensis (Diptera: Culicidae): a systematic review. Infect Dis Poverty. 2017;6:160. doi: 10.1186/s40249-017-0366-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Russell TL, Govella NJ, Azizi S, Drakeley CJ, Kachur SP, Killeen GF. Increased proportions of outdoor feeding among residual malaria vector populations following increased use of insecticide-treated nets in rural Tanzania. Malar J. 2011;10:80. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-10-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kabula B, Tungu P, Matowo J, Kitau J, Mweya C, Emidi B, et al. Susceptibility status of malaria vectors to insecticides commonly used for malaria control in Tanzania. Trop Med Int Health. 2012;17(6):742–750. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2012.02986.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Diabate A, Baldet T, Chandre F, Akogbeto M, Guigueride TR, Darriet F, et al. The role of agricultural use of insecticides in resistance to pyrethroids in Anopheles gambiae s.l. in Burkina Faso. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2002;67:617–622. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2002.67.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yadouleton AWM, Asidi A, Djouaka RF, Braïma J, Agossou CD, Akogbeto MC. Development of vegetable farming: a cause of the emergence of insecticide resistance in populations of Anopheles gambiae in urban areas of Benin. Malar J. 2009;8:103. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-8-103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.N’Guessan R, Asidi A, Boko P, Odjo A, Akogbeto M, Pigeon O, et al. An experimental hut evaluation of permanet 3.0, a deltamethrin-piperonylbutoxide combination net, against pyrethroid-resistant Anophelesgambiae and Culexquinquefasciatus mosquitoes in Southern Benin. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2010;104:758–765. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2010.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tungu P, Magesa S, Maxwell C, Malima R, Masue D, Sudi W, et al. Evaluation of PermaNet 3.0 a deltamethrin-PBO combination net against Anophelesgambiae and pyrethroid resistant Culexquinquefasciatus mosquitoes: an experimental huts trial in Tanzania. Malar J. 2010;9:21. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-9-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Koudou BG, Koffi AA, Malone D, Hemingway J. Efficacy of PermaNet® 2.0 and PermaNet® 3.0 against insecticide-resistant Anophelesgambiae in experimental huts in Côte d’Ivoire. Malar J. 2011;10:172. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-10-172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chandre F, Manguin S, Brengues J, Dossou YJ, Darriet F, Diabate A, et al. Current distribution of pyrethroid resistance gene (kdr) in Anopheles gambiae complex from West Africa and further evidence for reproductive isolation of Mopti form. Parasitologia. 2000;41:319–322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Janko MM, Churcher TS, Meshnick SR, et al. Strengthening long lasting insecticidal nets effectiveness monitoring using retrospective analysis of cross-sectional, population based surveys across sub-Saharan Africa. Sci Rep. 2018;8:17110. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-35353-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Paaijmans KP, Huijben S. Taking the “I” out of LLINs. Using insecticides in vector control tools other than long-lasting nets to fight malaria. Malar J. 2020;19:73. doi: 10.1186/s12936-020-3151-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ochomo E, Bayoh NM, Kamau L, Atieli F, Vulule J, Ouma C, et al. Pyrethroid susceptibility of malaria vectors in four districts of Western Kenya. Parasites Vectors. 2014;7:310. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-7-310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Reid MC, McKenzie FE. The contribution of agricultural insecticide use to increasing insecticide resistance in African malaria vectors. Malar J. 2016;2016(9):62. doi: 10.1186/s12936-016-1162-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wandiga S, Lalah J, Kaigwara P, Taylor D, Klaine S, Carvalho F. Pesticides in Kenya. In: Taylor MD, Klaine SJ, Carvalho FP, Barcelo D, Everaarts J, editors. Pesticide residues in coastal tropical ecosystems: distribution, fate and effects. London: Taylor and Francis Groups; 2003. p. 49–80.

- 59.Ngala CJ, Kamau L, Mireji PO, Mburu J, Mbogo C. Insecticide resistance, host preference and Plasmodium falciparum parasite rates in Anopheles mosquitoes in Mwea and Ahero rice schemes. J Mosq Res. 2015;14:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Aizoun N, Aikpon R, Gnanguenon V, Oussou O, Agossa F, Padonou GG. Status of organophosphate and carbamate resistance in Anopheles gambie sensu lato from the South and North Benin, West Africa. Parasites Vectors. 2013;6:274. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-6-274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kawada H, Dida GO, Ohashi K, Komagata O, Kasai S, Tomita T, et al. Multimodal pyrethroid resistance in malaria vectors, Anopheles gambiae s.s., Anophelesarabiensis and Anophelesfunestus s.s. in Western Kenya. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:8. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ochomo E, Bayoh MN, Brogdon WG, Gimnig JE, Ouma C, Vulule JM, et al. Pyrethroid resistance in Anopheles gambiae s.s. and Anophelesarabiensis in western Kenya: phenotypic, metabolic and target site characterizations of three populations. Med Vet Entomol. 2013;27:156–164. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2915.2012.01039.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chen H, Githeko AK, Githure JI, Mutunga J, Zhou G, Yan G. Monooxygenase levels and knock-down resistance (kdr) allele frequencies in Anopheles gambiae and Anopheles arabiensis in Kenya. J Med Entomol. 2008;45:242–250. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/45.2.242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fassinou YH, Jacques A, Koukpo CZ, Sizonlin M, et al. Genetic structure of Anopheles gambiae s.s. populations following the use of insecticides on several consecutive years in Southern Benin. Trop Med Health. 2019;47:23. doi: 10.1186/s41182-019-0151-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.World Health Organization . Global plan for insecticide resistance management in malaria vectors. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vulule JM, Beach RF, Atieli FK, Robert JM, Mount DL, Mwangi RW. Reduced susceptibility of Anophelesgambiae s.s. to permethrin associated with the use of Permethrin—impregnated bed nets and curtains in Kenya. Med Vet Entomol. 1994;8:71–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2915.1994.tb00389.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mulamba C, Riveron JM, Ibrahim SS, Irving H, Barnes KG, Mukwaya LG, et al. Widespread pyrethroid and DDT resistance in the major malaria vector Anopheles funestus in East Africa is driven by metabolic resistance mechanisms. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0110058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wanjala CL, Kweka EJ. Malaria vectors insecticides resistance in different agroecosystems in western Kenya. Front Public Health. 2018;6:55. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2018.00055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Henry MC, et al. Protective efficacyof lambda-cyhalothrin treated nets in Anopheles gambiae pyrethroid resistance areas of Cote d’Ivoire. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2005;73:859–864. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2005.73.859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated and supporting the conclusions of this manuscript has been included in the article. Raw data and materials are available from the corresponding author upon request.