Abstract

Background

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is causing a rapid and tragic health emergency worldwide. Because of the particularity of COVID-19, people are at a high risk of pressure injuries during the prevention and treatment process of COVID-19.

Objectives

This systematic review aimed to summarize the pressure injuries caused by COVID-19 and the corresponding preventive measures and treatments.

Methods

This systematic review was according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses guidelines. PubMed, Web of science and CNKI (Chinese) were searched for studies on pressure injuries caused by COVID-19 published up to August 4, 2020. The quality of included studies was assessed by the Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale (NOS) and the CARE guidelines.

Results

The data were extracted from 16 studies involving 7,696 participants in 7 countries. All studies were published in 2020. There are two main types of pressure injuries caused by the COVID-19: 1) Pressure injuries that caused by protective equipment (masks, goggles and face shield, etc.) in the prevention process; 2) pressure injuries caused by prolonged prone position in the therapy process.

Conclusions

In this systematic review, the included studies showed that wearing protective equipment for a long time and long-term prone positioning with mechanical ventilation will cause pressure injuries in the oppressed area. Foam dressing may need to be prioritized in the prevention of medical device related pressure injuries. The prevention of pressure injuries should be our particular attention in the course of clinical treatment and nursing.

Keywords: COVID-19, Pressure injuries, Prone position, Systematic review

1. Introduction

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and the disease it causes, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), are causing a rapid and tragic health emergency worldwide [1,2]. More than 14 million confirmed cases of COVID-19 have been reported by the end of July 2020 [3]. Due to the high infectivity and pathogenicity of COVID-19, the clinical treatment and nursing care are extremely difficult and require high standards [4]. With the increasing use of medical protective equipment and medical devices, the number of medical staff and COVID-19 patients suffering from pressure injuries is increasing [5].

The routes of SARS-CoV-2 include direct contact (contact with the respiratory droplets and aerosols from a affected person) and indirect contact (contact with contaminated surfaces or supplies) [6]. In order to resist the invasion and infection of the SARS-CoV-2, front-line medical staff must wear a series of protective items, including medical protective masks (N95 masks and surgical masks), goggles, protective face screens, protective gowns, etc. [5,7]. Wearing the protective equipment for a long time will produce persistent pressure on the local skin, which may lead to pressure injuries [8]. Pressure injuries are local skin damage and underlying tissues caused by unrelieved pressure, shear and friction [9].

Meanwhile, prone positioning is also widely used to treat COVID-19 complicated by severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). In cases of severe ARDS, prone positioning of patients not only control the airways to provide mechanical invasive ventilation, but also reduce the mortality of patients [10,11]. The pressure injuries caused by it has been identified as the most frequent complication [12,13].

Thus, this systematic review of the current studies on pressure injuries caused by COVID-19 was conducted for the purposes of summarizing the pressure injuries caused by COVID-19, discussing the reasons behind as well as the corresponding preventive measures and treatments.

2. Methods

2.1. Search strategy

A systematic search was carried out by PubMed, CNKI (Chinese) and Web of Science databases. The following search terms were used: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, Novel coronavirus pneumonia, pressure, pressure injury, pressure sore and pressure ulcer. The search string adapted for PubMed database was (“COVID-19” [title/abstract] OR “SARS-CoV-2” [title/abstract] OR “Novel coronavirus pneumonia” [title/abstract]) AND (“pressure” [title/abstract] OR “pressure injury” [title/abstract] OR “pressure sore” [title/abstract] OR “pressure ulcer” [title/abstract] OR “decubitus” [title/abstract]). We also manually searched the references of all relevant studies to supplement our searches. There were no language restrictions, but the publication time of studies was limited from December 2019 to August 2020. This study followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guideline [14].

2.2. Study selection

Criteria for inclusion of the relevant studies are as follows: 1) types of participants: the people who developed pressure injuries due to COVID-19 must be reported; 2) the source of pressure injuries must be reported in the study; 3) measures to prevent or treat pressure injuries must be included in the study; 4) types of study design: randomized controlled trial (RCT), case report, case-control study and cohort study.

2.3. Data extraction and quality assessment

Two authors independently extracted the data into pre-designed standardized tables. The data included: 1) first author; 2) published year; 3) country; 4) study design; 5) site of pressure injuries; 6) grade of pressure injuries; 7) daily wearing time of protective equipment/prone time; 8) source of pressure injuries; 9) treatment for pressure injuries; and 10) key findings. The quality of included studies were assessed by the Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale (NOS) and The CARE Guidelines. Discrepant judgements of the extracted data were resolved after discussion with the third author.

3. Results

3.1. Eligible studies

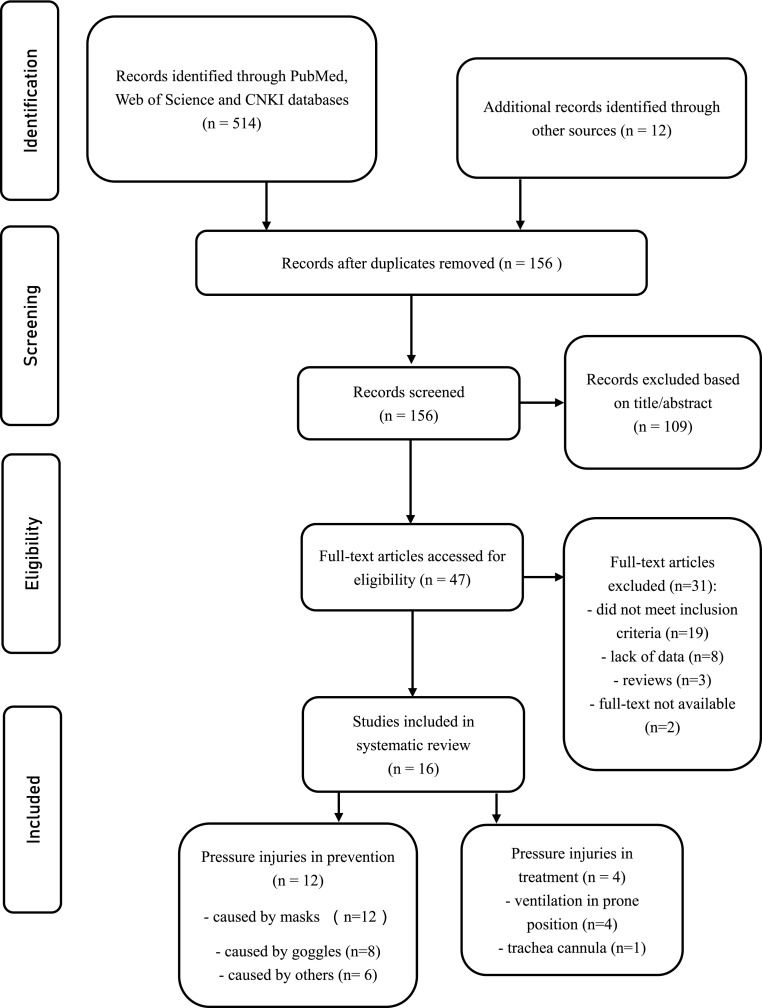

A total of 514 studies were identified from databases including PubMed, Web of Science and CNKI (Chinese), we excluded 370 duplicate results. One hundred and nine studies were excluded by titles and abstracts. After assessing 47 full-text studies, we excluded 31 full-text studies due to 1) did not meet inclusion criteria (n = 19); 2) lack of data (n = 8); 3) reviews (n = 3) and 4) full-text not available. Thus, 16 studies were included in this systematic review. Fig. 1 displays the process of selection of studies. After evaluation, the quality of all included prospective cohort studies and case-control studies was assessed by the Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale and the scores of each study is detailed in Table 1 . The quality of included case reports was assessed by CARE guideline and all of them were deemed credible.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of the study selection and exclusion process.

Table 1.

The qualities of included studies (case-control study or cohort study) by Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale (NOS).

| Study | Study design | Selection |

Comparability |

Outcome/Exposure |

Score | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1) | 2) | 3) | 4) | 1) | 1) | 2) | 3) | |||

| Yun, W. | case-control study | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | 8 | |

| Jiang, Q. (a) | cohort study | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | 9 |

| Tang, J. | cohort study | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | 8 | |

| Jiang, Q. (b) | cohort study | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | 9 |

| Feng, C. | cohort study | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | 8 | |

| Yu, H. | cohort study | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | 8 | |

| Xia, J | cohort study | ★ | ★ | ★★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | 7 | ||

| Zheng, R. | cohort study | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★★ | ★ | ★ | 7 | ||

| Peko, L. | case-control study | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | 9 |

There was a total of 7,696 participants, and the sample sizes ranged from 1 to 4,306. All included studies were published in 2020. Of the 16 studies, eight were conducted in China, two in Spain, five in UK, Australia, Italy, Malaysia and France. There were two main types of pressure injuries caused by the COVID-19: 1) Pressure injuries that caused by protective equipment (masks, goggles and face shield, etc.) in the prevention process; 2) pressure injuries caused by prolonged prone position in the therapy process. The summary of these two main types of COVID-19 related pressure injuries was provided in Table 2 and Table 3 respectively.

Table 2.

Summary of the studies on pressure injuries in personnel using preventive measures against COVID-19.

| Author, year, country | Source of PI | Sample size Gender (M/F) |

Age (years) | Study design | Site of PI | PI grade | DWT | measures | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lam, U. N. 2020, Malaysia | ① | 5 (0/5) | Median age 32.5 (29–36) |

Case report | Bridge of nose | I, n = 4 III, n = 1 |

3 h, n = 1 4–5 h, n = 2 >6 h, n = 2 |

1) foam dressing 2) hydrocolloid dressing (DuoDERM EXTRA THIN) |

|

| Del Castillo, J. L., 2020, Spain | ①②③ | NR | NR | Case report | Nasal dorsum, cheeks and forehead | NR | Upwards of 4–5 h | hydrocolloid dressing |

|

| Field, M. H., 2020, UK | ① | NR | NR | Case report | Bridge of nose | NR | NR | Hydrocolloid dressing |

|

| Yun, W, 2020, China | ①②③ | 60 (0/60) | Median age EG: 27.5 (23–32) CG: 28.5 (24–33) |

Case-control study | Nose, forehead, cheeks, auricle | EG: I, n = 3 II, n = 1 CG: I, n = 12 II, n = 8 III, n = 1 |

8 h | Foam dressing |

|

| Jiang, Q., 2020, China | ①②④ | 4306 (516/3790) | <35, n = 2903; ≥35,n = 1403 |

Prospective cohort study | Bridge of nose, cheeks, auricle, forehead, others (mandible, groin, neck and so on) | I, n = 2866 II, n = 551 III, n = 17 DTI, 23 |

>4 h, n = 3632 ≥4 h, n = 674 |

1) hydrocolloid dressing 2) silicone foam dressing |

|

| Tang, J., 2020, China | ①②③ | 102 (42/59) | Median age 31 (25–55) |

Prospective cohort study | Nasal bridge, zygomatic arch, auricles | I, n = 51 II and above, n = 11 |

Median time 6 h (0–17 h) |

1) reduce bearing time 2) hydrocolloid dressing |

|

| Jiang, Q., 2020, China | ①②④ | 2901 (214/2687) | Average age (31.9 ± 7.1) | Prospective cohort study | Bridge of nose, cheeks, ears, forehead and others | I, n = 667 II, n = 98 III, n = 1 DTI, N = 5 |

≤4 h, n = 326 5–8 h, n = 2140 ≥9 h, n = 471 |

1) foam dressing 2) hydrocolloid dressing 3) oiling agent 4) others (film dressing, band-aid and so on) |

|

| Feng, C., 2020, China | ①② | 45 (8/37) | Average age (32.5 ± 3.5) | Prospective cohort study | Nose, cheeks, auricle, forehead, neck | I, n = 39 II, n = 16 |

4–4.5 h | 1) foam dressing 2) hydrocolloid dressing |

|

| Yu, H., 2020, China | ①② | 174 (4/170) | Average age (30.11 ± 4.39) | Prospective cohort study | Nose, cheeks, auricle, forehead, neck | I, n = 116 II, n = 20 IV, n = 1 |

NR | Preventive dressing |

|

| Yin, Z., 2020, China | ① | NR | NR | Case report | NR | NR | NR | 1) hydrocolloid dressing 2) paste benzalkonium chloride patch firstly and using hydrocolloid dressing secondly |

|

| Xia, J., 2020, China | ①②④ | 89 (2/87) | Average age (37.83 ± 4.65) | Prospective cohort study | Nose, cheeks, forehead, auricle | I, n = 12 II, n = 3 |

<4 h, n = 20 4-5, n = 22 6-8, n = 5 ≥9, n = 7 |

1) foam dressing 2) hydrocolloid dressing 3) liquid dressing 4) petrolatum gauze |

|

| Zheng, R., 2020, China | ① | 10 (3/7) | Median age 36.5 (25–48) |

Prospective cohort study | Nose, cheeks, auricle | I, n = 10 II, n = 2 DTI, n = 1 |

6–8 h | Hydrocolloid dressing |

|

Notes. PI = pressure injury, DWT = daily wearing time, HCW = health care workers, NR = not reported; EG = experimental group; CG = control group; DTI = deep tissue injury; PPE = personal protective equipment; ① masks; ② goggles; ③ face shield; ④ protective clothing.

Table 3.

Summary of the studies on pressure injuries in patients treated for COVID-19.

| Author, year, country | Source of PI | Sample size Gender (M/F) Age (years) |

Study design | Site of PI | PI grade | Prone time | measures | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peko, L., 2020, Australia | NR | NR | Case-control study | Forehead, chin | NR | 16 h–24 h | Multi-layered silicone-foam prophylactic dressings |

|

| Zingarelli, E. M., 2020, Italy | Breathing tube | 1 (0/1); 50 |

Case report | Lips, chin, perioral area, both cheeks, left zygomatic region, and superior and inferior left eyelids | NR | At least 12 h daily | 1) thin silicone foam dressing 2) Silver Sulfadiazine 3) Hyaluronic Acid And Sodium and sterile gauzes 4) hyaluronic acid sodium salt collagenase and ointment |

|

| Martinez Campayo, N., 2020, Spain | NR | 1 (1/0); 78 |

Case report | chest | NR | 13 sessions of 20 h each | 1) chemical debridement 2) hydrocolloid dressing |

|

| Perrillat, A., 2020, France | Breathing tube, feeding tube | 2 (2/0); 27/50 |

Case report | Forehead, cheeks, labial commissure | II, III | 6–9′ sessions of at least 12 h each | 1) debridement of necrotic tissue 2) paraffin gauze dressing |

|

Notes: PI = pressure injury, ARDS = acute respiratory distress syndrome, NR = not reported.

3.2. Pressure injuries in medical prevention of COVID-19

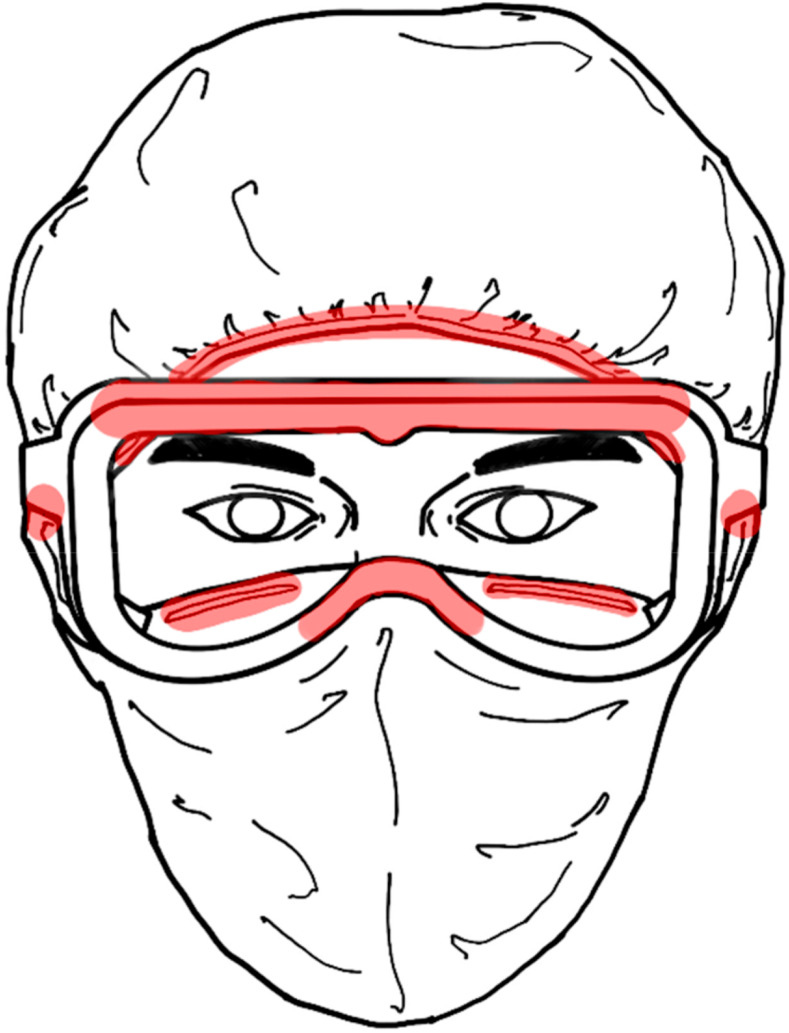

We identified 12 studies [1,5,7,[15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22]] that targeted the protective equipment related pressure injuries. The population was mainly medical staff. There were 4 case reports [1,7,15,16], 1 case-control study [22] and 7 prospective cohort studies [5,[17], [18], [19], [20], [21],23]. Pressure injuries often occur on the bridge of the nose, cheeks, forehead and auricle (Fig. 2 ). The kinds of medical protective equipment include masks (N95 masks and surgical masks), goggles, protective gowns and so on. The three main measures identified as preventing pressure injuries were: 1) use of silicone foam dressings; 2) use of hydrocolloid dressings and 3) strict control on the wearing time of medical protective equipment. After comprehensive analysis, foam dressing may need to be prioritized in the prevention of medical device related pressure injuries. Meanwhile, the continuous wearing time of medical protective equipment should preferably be less than 4 h.

Fig. 2.

Diagrammatic sketch of the sites of pressure injuries (marked in red) prone to occur in the prevention. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

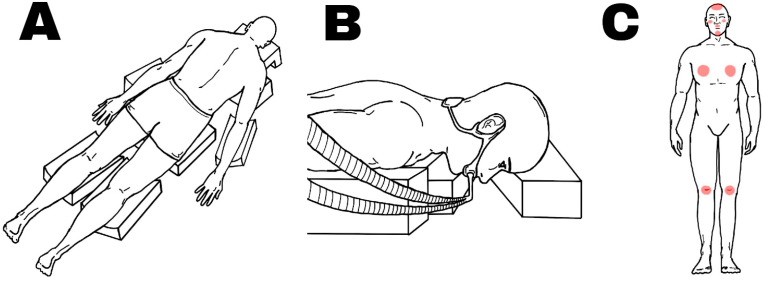

3.3. Pressure injuries in medical treatment of COVID-19

There were 4 studies [12,[24], [25], [26]] (3 case reports and 1 case-control study) identified. It was ascertained that the main sites of pressure injuries were on the forehead, chin, cheeks, lips and chest (Fig. 3 ). The time of the prone position across the studies was more than 12 h per day. The two main prevention measures used were: 1) use of specific softer prone positioning head cushion; 2) use of silicone gels or silicone foam dressing; 3) changing head position 2 or 3 times during a session and the position of the breathing tube should be changed between each session. The main treatment is to use the chemical debridement of necrotic tissue.

Fig. 3.

Diagrammatic sketch of patients in prone position ventilation and the sites of pressure injuries prone to occur are marked in red. (A: schematic illustration of prone position; B: schematic illustration of mechanical ventilation; C: schematic illustration of the location of pressure injuries).

4. Discussion

This systematic review synthesized results of 16 studies on pressure injuries associated with COVID-19. It demonstrated that there were two main types of pressure injuries caused by the COVID-19: pressure injuries that are caused by protective devices in the prevention process and pressure injuries caused by prolonged prone position in the therapy process. The use of prophylactic dressings, such as silicone foam dressing and hydrocolloid dressing, can effectively reduce the occurrence of pressure injuries [16,20]. At the same time, it is also very important to strictly limit the continuous wearing time of medical protective equipment.

Additional studies were sourced that confirmed this conclusion. The main risk factors and mechanisms of pressure injuries associated with COVID-19 are as follows. First, wearing medical protective equipment, such as N95 masks and goggles, and maintaining a prone position for a long time will increase the local pressure and friction on the skin [17,27,28]. Medical staff with pressure injuries wear medical protective masks (N95 masks and surgical masks) continuously for more than 4 h daily, especially in the case of nursing staff [29,30]. Meanwhile, the application of prone positioning has expanded sharply during the present COVID-19 pandemic placing more patients at risk of pressure injury development. In ICUs, those patients with ARDS are mechanically ventilated and typically placed prone for sessions of approximately 16 h or more and up to 24 h, in order to improve their lung mechanics and tissue oxygenation [31,32]. Besides, the shortage of supplies at the beginning of the COVID-19 outbreak also extended the wearing time of protective equipment to a certain extent. Second, most protective gowns are disposable sterile medical protective clothing with the standard of GB19082, which is made of isolation material and has poor moisture permeability. Therefore, the use of face masks and goggles and wearing protective gowns for a long time will increase medical staff's skin temperature and sweat profusely, leaving the local skin in a moist environment. The high skin temperature and profuse sweating accelerate pressure injuries [33].

Although hydrocolloid dressing is often used to prevent and cure pressure injuries [34], some researchers have found some of its flaws in its use [23]. Due to the strong stickiness of hydrocolloid, it may aggravate an existing pressure injury when one is removing a mask as it rips away the dressing [7]. Some studies suggested that a paste benzalkonium chloride patch be used before wearing the mask, as a means of effectively relieving the problem of using a hydrocolloid dressings. Zinc therapy has also been suggested as a promoter of wound healing, because suitable zinc levels can maintain the body's immune function [35,36]. What's more, Surgical pearl, a novel technology for wearing ear-ring masks to reduce ear pressure, thereby reducing ear pressure injuries has also been proposed as a possible solution [37].

This systematic review suggested that medical staff should pay great attention to the prevention of pressure injuries. In term of themselves, using preventive dressings before wearing protective equipment can greatly reduce the occurrence of pressure injuries. In term of patients with COVID-19, medical staff should not only use the preventive dressings, but also conduct skin assessment for patients and use assistive devices like the specific softer prone -positioning head cushion with space for the breathing tube to relieve local pressure [38]. Meanwhile, in the process of treating and caring for patients, medical staff should ideally wear protective equipment for less than 3 h. Prone positioning patients’ head position should be changed 2 or 3 times during a prone position session and the position of the breathing tube should be changed between each prone position session [25].

There are some limitations in this review. First, the number of included studies is not enough, especially the studies on pressure injuries in the therapy process of COVID-19, both in normal supine position and prone position. There is also a lack of randomized controlled trials. Second, we included some case reports to obtain more comprehensive information, but this will bring some heterogeneity to the article. Third, the grade of pressure injuries that was extracted from the included studies are based on the National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (NPUAP) guidelines, but pressure injuries are still difficult to assess accurately, both in grading them but also in identifying them accurately.

5. Conclusion

In this systematic review, it has been found that during the prevention and therapy process of COVID-19, medical staff and patients of COVID-19 are at risk of developing pressure injuries. Because wearing protective equipment for a long time and long-term prone positioning with mechanical ventilation increase the risk of pressure injuries in the oppressed area, medical staff should pay attention to preventing injury to their own skin and on the skin of their patients.

Funding

This study was supported by the Humanities and Social Sciences of Ministry of Education Planning Fund (20YJAZH007); Social and People's Livelihood Technology in Nantong city-General Project (MS12019038).

Declaration of competing interest

The authors stated that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the medical staff working in the frontline of COVID-19.

References

- 1.Field M.H., Rashbrook J.P., Rodrigues J.N. Hydrocolloid dressing strip over bridge of nose to relieve pain and pressure from Filtered Face Piece (FFP) masks during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2020;102:394–396. doi: 10.1308/rcsann.2020.0095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang H., Zeng T., Wu X., Sun H., et al. Holistic care for patients with severe coronavirus disease 2019: an expert consensus. International journal of nursing sciences. 2020;7:128–134. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnss.2020.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hooks M., Bart B., Vardeny O., Westanmo A., Adabag S. Effects of hydroxychloroquine treatment on QT interval. Heart Rhythm. 2020;17:1930–1935. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2020.06.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu D., Li L., Wu X., Zheng D., Wang J., Yang L., et al. Pregnancy and perinatal outcomes of women with coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pneumonia: a preliminary analysis. AJR American journal of roentgenology. 2020;215:127–132. doi: 10.2214/AJR.20.23072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jiang Q., Liu Y., Wei W., Zhu D., Chen A., Liu H., et al. The prevalence, characteristics, and related factors of pressure injury in medical staff wearing personal protective equipment against COVID-19 in China: a multicentre cross-sectional survey. Int Wound J. 2020;17:1300–1309. doi: 10.1111/iwj.13391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ortega R., Gonzalez M., Nozari A., Canelli R. Personal protective equipment and covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:e105. doi: 10.1056/NEJMvcm2014809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yin Z.Q. Covid-19: countermeasure for N95 mask-induced pressure sore. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:e294–e295. doi: 10.1111/jdv.16490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gefen A., Ousey K. Update to device-related pressure ulcers: SECURE prevention. COVID-19, face masks and skin damage. J Wound Care. 2020;29:245–259. doi: 10.12968/jowc.2020.29.5.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu P., Shen W., Chen H. Efficacy of arginine-enriched enteral formulas for the healing of pressure ulcers: a systematic review. J Wound Care. 2017;26:319–323. doi: 10.12968/jowc.2017.26.6.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gattinoni L., Busana M., Giosa L., Macri M.M., Quintel M. Prone positioning in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;40:94–100. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1685180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Munshi L., Del Sorbo L., Adhikari N.K.J., Hodgson C.L., Wunsch H., Meade M.O., et al. Prone position for acute respiratory distress syndrome. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017;14:S280–S288. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201704-343OT. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peko L., Barakat-Johnson M., Gefen A. Protecting prone positioned patients from facial pressure ulcers using prophylactic dressings: a timely biomechanical analysis in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Int Wound J. 2020;17:1595–1606. doi: 10.1111/iwj.13435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lucchini A., Bambi S., Mattiussi E., Elli S., Villa L., Bondi H., et al. Prone position in acute respiratory distress syndrome patients: a retrospective analysis of complications. Dimens Crit Care Nurs. 2020;39:39–46. doi: 10.1097/DCC.0000000000000393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D.G., Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lam U.N., Md Mydin Siddik N.S.F., Mohd Yussof S.J., Ibrahim S. N95 respirator associated pressure ulcer amongst COVID-19 health care workers. Int Wound J. 2020;17:1525–1527. doi: 10.1111/iwj.13398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Del Castillo Pardo de Vera J.L., Reina Alcalde S., Cebrian Carretero J.L., Burgueno Garcia M. The preventive effect of hydrocolloid dressing to prevent facial pressure and facial marks during use of medical protective equipment in COVID-19 pandemic. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2020;58:723–725. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2020.04.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tang J., Zhang S., Chen Q., Li W., Yang J. Risk factors for facial pressure sore of healthcare workers during the outbreak of COVID-19. Int Wound J. 2020;17:2028–2030. doi: 10.1111/iwj.13434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jiang Q., Xu J., Wei W., Jiang Z., Zhang Y., Wang J., et al. Investigation of prevention and management of skin injuries associated with the use of personal protective equipment among medical staff fighting against COVID-19. Journal of Nursing Science. 2020;35:4–7. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu H., Wang H., Shi J., Luo M. Investigation on the current situation of device-related pressure injuries on head and face of nursing staff during the novel coronavirus pneumonia epidemic. Chinese General Practicing Nursing. 2020;18:1456–1459. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xia J., Duan X., Cao C., Zhang J., Yu C., Wang K. Investigation and risk factors analysis of pressure injury caused by personal protective equipment during the noval coronavirus pneumonia period. J Nurs Adm. 2020;20:252–256. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zheng R., Ni H., Pan L. Experience survey of medical staff wearing N95 masks during the third-level prevention and control of medical device-related pressure ulcers. Chinese Journal of Rural Medicine and Pharmacy. 2020;27:62–63. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yun W., Song K., Xu Y. Effect of reverse stick method of foam dressing on improving device-related pressure injury among nurses. Chin Nurs Res. 2020;34:1134–1136. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Feng C., Chen P. Current status and preventive measures of pressure-related injuries related to head and face medical protective equipment in the new coronavirus pneumonia isolation ward. Modern Practical Medicine. 2020;32:290–291+306. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zingarelli E.M., Ghiglione M., Pesce M., Orejuela I., Scarrone S., Panizza R. Facial pressure ulcers in a COVID-19 50-year-old female intubated patient. Indian J Plast Surg. 2020;53:144–146. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1710403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martinez Campayo N., Bugallo Sanz J.I., Mosquera Fajardo I. Symmetric chest pressure ulcers, consequence of prone position ventilation in a patient with COVID-19. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:e672–e673. doi: 10.1111/jdv.16755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perrillat A., Foletti J.M., Lacagne A.S., Guyot L., Graillon N. Facial pressure ulcers in COVID-19 patients undergoing prone positioning: how to prevent an underestimated epidemic? J Stomatol Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2020;121:442–444. doi: 10.1016/j.jormas.2020.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang Y., Sheng C., Wang B., Ma Z., Yang F. Prevention and treatment strategies for device-related stress injuries during the novel coronavirus pneumonia epidemic. Journal of Pharmaceutical Practice. 2020;38:97–100+9. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zheng K.I., Rios R.S., Zeng Q.Q., Zheng M.H. COVID-19 cross-infection and pressured ulceration among healthcare workers: are we really protected by respirators? Front Med. 2020;7 doi: 10.3389/fmed.2020.571493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dell'Era V., Aluffi Valletti P., Garzaro M. Nasal pressure injuries during the COVID-19 epidemic. Ear Nose Throat J. 2020 doi: 10.1177/0145561320922705. 145561320922705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tang J., Li B., Gong J., Li W., Yang J. Challenges in the management of critical ill COVID-19 patients with pressure ulcer. Int Wound J. 2020;17:1523–1524. doi: 10.1111/iwj.13399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moore Z., Patton D., Avsar P., McEvoy N.L., Curley G., Budri A., et al. Prevention of pressure ulcers among individuals cared for in the prone position: lessons for the COVID-19 emergency. J Wound Care. 2020;29:312–320. doi: 10.12968/jowc.2020.29.6.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jiang S., Fang C., Chen J., Smith R. The face of COVID-19: facial pressure wounds related to prone positioning in patients undergoing ventilation in the intensive care unit. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery. 2021;164:300–301. doi: 10.1177/0194599820951470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gefen A., Ousey K. COVID-19, fever and dressings used for pressure ulcer prevention: monthly update. J Wound Care. 2020;29:430–431. doi: 10.12968/jowc.2020.29.8.430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cai J.Y., Zha M.L., Chen H.L. Use of a hydrocolloid dressing in the prevention of device-related pressure ulcers during noninvasive ventilation: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Wound Manag Prev. 2019;65:30–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Song Y.P., Wang L., Yu H.R., Yuan B.F., Shen H.W., Du L., et al. Zinc therapy is a reasonable choice for patients with pressure injuries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr Clin Pract. 2020;35:1001–1009. doi: 10.1002/ncp.10485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nakamura H., Sekiguchi A., Ogawa Y., Kawamura T., Akai R., Iwawaki T., et al. Zinc deficiency exacerbates pressure ulcers by increasing oxidative stress and ATP in the skin. J Dermatol Sci. 2019;95:62–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2019.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mukhtar M. Surgical pearl:Novel techniques of wearing ear-looped mask for reducing pressure on the ear. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:e333–e334. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.07.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moore Z., Patton D., Avsar P., McEvoy N., Curley G., Budri A., et al. Prevention of pressure ulcers among individuals cared for in the prone position: lessons for the COVID-19 emergency. J Wound Care. 2020;29:312–320. doi: 10.12968/jowc.2020.29.6.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]