Abstract

Background:

The learning environment plays a critical role in learners’ satisfaction and outcomes. However, we often lack insight into learners’ perceptions and assessments of these environments. It can be difficult to discern learners’ expectations, making their input critical. When medical students and surgery residents are asked to evaluate their teachers, what do they focus on?

Materials and Methods:

Open-ended comments from medical students’ evaluations of residents and attending surgeons, and from residents’ evaluations of attendings during the 2016–2017 academic year were analyzed. Content analysis was used, and codes derived from the data. A matrix of theme by learner role was created to distinguish differences between medical student and resident learners. Sub-themes were grouped based on similarity into higher-order themes.

Results:

Two overarching themes were Creating a Positive Environment for Learning by Modeling Professional Behaviors and Intentionally Engaging Learners in Training and Educational Opportunities. Medical students and residents made similar comments for the sub-themes of appropriate demeanor, tone and dialogue, respect, effective direct instruction, feedback, debriefing, giving appropriate levels of autonomy, and their expectations as team members on a service. Differences existed in the sub-themes of punctuality, using evidence, clinical knowledge, efficiency, direct interactions with patients, learning outcomes, and career decisions.

Conclusions:

Faculty development efforts should target professional communication, execution of teaching skills, and relationships among surgeons, other providers, and patients. Attendings should make efforts to discuss their approach to clinical decision-making and patient interactions and help residents and medical students voice their opinions and questions through trusting, adult learner-teacher relationships.

Keywords: Teaching evaluation, Medical students, Residents, Professional development, Learning environment

Introduction

The learning environment plays a central role in learners’ satisfaction and learning outcomes. However, we often do not have insight into learners’ perceptions and assessments of their learning environments. Student evaluations of teaching are meant to provide information about students’ perceptions of the learning environment, specifically with regard to their experiences with those from whom they are learning. This is essential given that prior work has shown that educators serve as role models; they influence not only the student’s experience of learning, but also the student’s perception of a professional field and their ability to see themselves working in that profession.1,2 Due to the importance of medical educators in the development of students entering medicine, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) has recently released new guidelines for faculty development that stress annual and continuous development as educators.3 Information from learners’ evaluations of teaching may inform these development efforts if we interpret learners’ responses in ways that allow for actionable changes and continuous improvement.

Surgical education is a complex environment in which clinical instructors are asked to meet the needs of learners at multiple levels, often simultaneously. For medical students, surgical rotations are intended, at minimum, to teach fundamental surgical skills, the role of the surgeon in the patient care team, and how other specialties interact with surgical specialties. In the best case, surgical rotations can inspire medical students to become future surgeons. However, medical students often find the learning environment in surgery challenging, with the workflow often contributing to perceptions of neglect, lack of integration into the surgical team, and unclear expectations.4,5 Studies have shown that perceptions of the surgical learning environment and of surgeons as professionals influence not only learning on surgical rotations, but also students’ opinions of surgery as a potential future specialty.6,7,8

Residents in surgery training programs have chosen surgery as their future profession. However, even at this level of training, attrition is a significant issue.9 Not surprisingly, the perception and experience of the learning environment exerts a great influence on residents’ well-being10, experience of burnout11, and what they gain from their surgical training in terms of skills, behaviors, and ability to successfully transition to independent practice as a surgeon.12 Instructors in the clinical environment play an important role in setting the tone for residents’ learning, confidence, and abilities to develop autonomy while engaging in surgical practice.13,14

Medical students and residents often interact as team members, students, and teachers in the clinical setting in surgery. By establishing their shared expectations, perceptions, and experiences in the clinical surgery learning environment, we can gain new knowledge to inform the professional development of medical educators, to encourage medical students to pursue surgical careers, and to improve residents’ wellness and feelings of burnout. Previous studies have not conducted a close comparison of the expectations and perspectives articulated in evaluations of teaching by medical students and residents learning the field of surgery in a shared clinical environment.

The purpose of this study was to investigate what medical students’ and surgery residents’ evaluations of teaching reveal about their expectations for the learning environment and their instructors on surgical rotations. Our research question was: When learners are asked to evaluate their clinical teachers, what are their perceptions of teaching during their surgical rotations, and on what aspects of their instructors do they focus, both positive and negative?

Materials and methods

Setting and Participants

Data were collected at a Midwestern academic surgery program. Four residency programs (General Surgery, Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Vascular Surgery, and Otolaryngology) train an average of 75 clinical residents at a time. Approximately 170 medical students rotate onto surgical services each year for 12 weeks in groups of approximately 40 students. All of these trainees had the opportunity to fill out at least one teaching evaluation form. Nearly 100 clinical attending faculty and 11 clinical fellows have education responsibilities as part of their roles in the department.

Data collection

As part of evaluations provided by both medical students and residents, learners are asked to complete role-specific online surveys. The surveys are sent electronically to medical students at the end of their 12-week Surgical and Procedural Care rotation and to residents at the end of their rotations on the various surgical services. All responses are confidential, and trainees are not asked to provide identifying information. The surveys are sent to trainees after the completion of the rotation or service, and comprise a series of Likert-type scale response questions asking them to rate their clinical instructors’ performance as teachers of both technical and non-technical skills and behaviors. Additionally, an open-ended text box is provided for learners to provide comments. Survey items such as “effective instructor” do not provide specific guidance as to which characteristics of the instructors or learning environments are influencing trainees’ perceptions and responses. Therefore, for this study, we focused on answers provided to the open-ended questions.

Open-ended comments from medical students to residents and attending physicians, and from residents to attending physicians, during the 2016–2017 academic year were abstracted from their respective databases for analysis. The institutional review board (IRB) at our institution determined this study to be program evaluation, and as such, exempt from IRB review. However, to maintain the privacy of medical students, residents, and faculty, all comments were de-identified before providing data to the research team. Because the comments are anonymous and trainees can comment on multiple attending physicians, we do not know the number of unique medical student and resident respondents that completed evaluations. Additionally, not all attending physicians or residents received evaluations of and comments on their teaching. This study focuses on identifying and coding types of comments, and grouping them into higher-order sub-themes and themes.

Data analysis

Since the open-ended text box did not specify what type of comments to provide, the researchers separated the comments based on whether the focus was on constructive, positive attributes or on undesirable, negative attributes of teachers or the learning environment. Comments that did not provide insight into the environmental or behavioral factors that contribute to the environment (e.g., “good teacher”; n=107) were eliminated from analyses. Open-ended comments (N=639) from residents to faculty and from medical students to both residents and faculty over one academic year (2016–2017) were content-analyzed. Three hundred twelve (312) positive comments from residents and 185 positive comments from medical student along with 68 negative comments from residents and 74 negative comments medical students were coded. As we set out to describe the perceptions of two distinct groups of trainees in a shared learning environment with the same clinical teachers, we used a naturalistic paradigm to interpret the meaning of their comments within the context of the surgery workplace in which the learning took place. Thus, we did not examine their comments through the lens of a pre-determined theory, but rather conducted a conventional content analysis, in which the categories of themes and codes were derived directly from the data.15

All comments were open-coded by two independent raters, an Educational Psychologist with a background in surgical education research and development, and a Social Psychologist with a background in surgical outcomes research. After all comments were coded, the researchers met to discuss the codes, refine the coding scheme, and resolve any disagreements. We then grouped the codes into higher-order sub-themes and themes. Finally, the rest of the research team, consisting of four academic surgeons from multiple specialties (surgical oncology, colorectal surgery, minimally invasive surgery, and trauma and acute care surgery), reviewed the codes and themes for accuracy and meaningfulness. Matrices were then created to organize sub-themes by learner role (medical student vs. resident); we selected illustrative quotes from positive and negative comments for each learner role from the open-ended text box comments.

Results

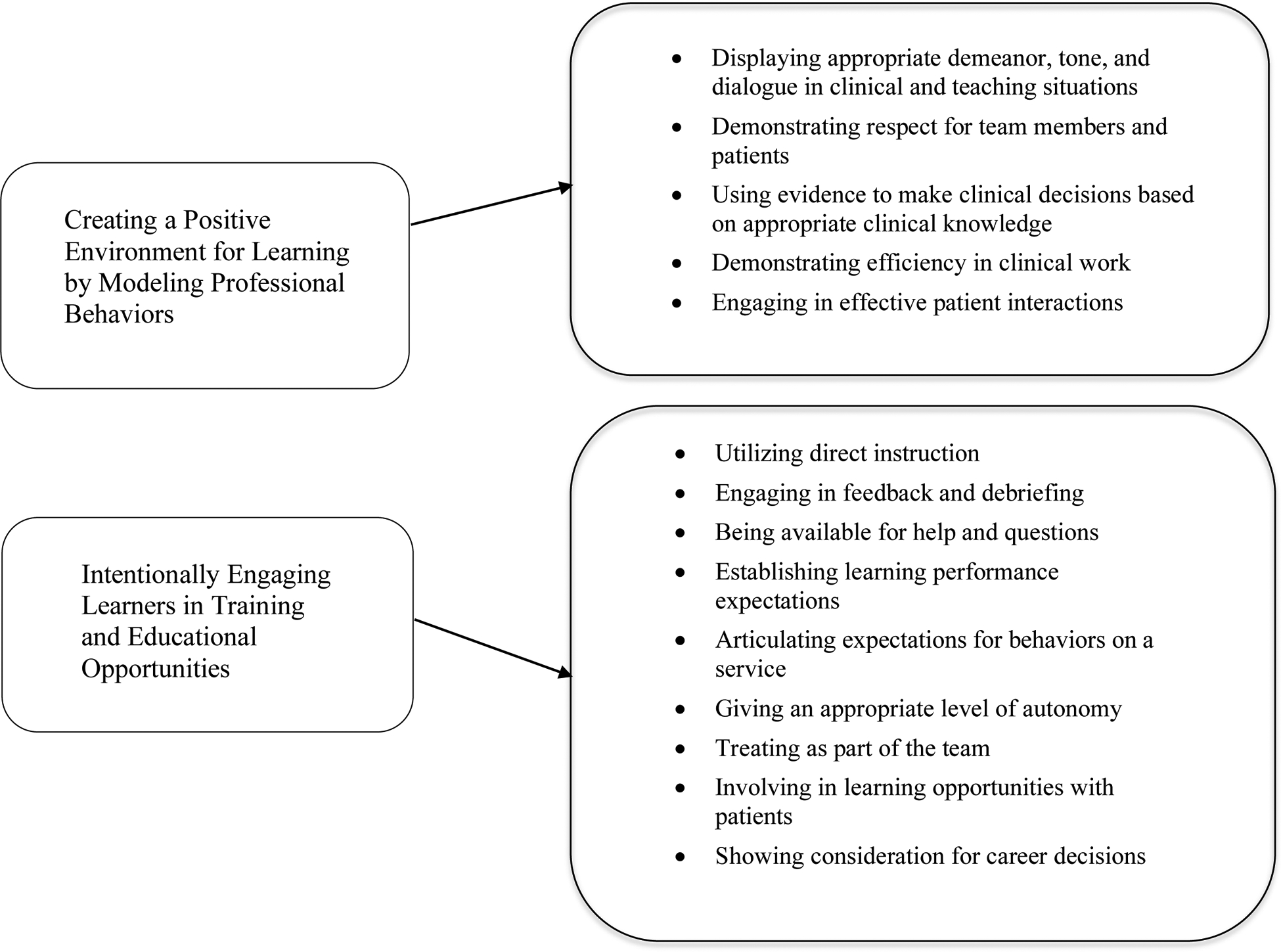

The codes were sorted into sub-themes, which were then combined into two broad, overarching themes (Figure 1): 1) Creating a Positive Environment for Learning by Modeling Professional Behaviors, and 2) Intentionally Engaging Learners in Training and Educational Opportunities. What follows is a comparison of positive and negative comments within the themes, with a discussion on whether they mostly applied to medical students’ comments on residents, medical students’ comments on attending physicians, or residents’ comments on attending physicians. The Appendix provides illustrative examples of both positive and negative comments for each of the three scenarios.

Figure 1:

The Two Overarching Themes and Their Sub-themes

Theme 1: Creating a Positive Environment for Learning by Modeling Professional Behaviors

This theme included actions and behaviors that contributed to creating an environment conducive to patient care, teaching, and learning. Within this domain, five sub-themes were identified.

Displaying appropriate demeanor, tone, and dialogue in clinical and teaching situations encompassed comments that were related to displaying socially appropriate behavior in clinical and teaching situations. This could be directed toward patients, trainees, or other members of the care team.

Demonstrating respect for team members and patients included any comments that referenced attitudes toward the input or presence of trainees and other team members, including being on time and respecting the time of others.

Using evidence to make clinical decisions based on appropriate clinical knowledge involved comments about providing supporting documentation or literature for clinical choices and observations about the clinical knowledge base as well as its application.

Demonstrating efficiency in clinical work encompassed observations on maintaining an adequate pace of practice while also being mindful of learners and patient care.

Engaging in effective patient interactions included comments about interacting with patients as well as coordinating, advocating for, and implementing their care.

Similarities and Differences Between Residents and Medical Students

Table 1 identifies presence or absence (Yes/No) of positive or negative (+/−) comments made by medical students and residents for the first overarching theme related to creating a positive environment for learning to take place. For the two sub-themes (appropriate demeanor, tone and dialogue, and respect), both residents and medical students commented on positive and negative instances of these behaviors they observed in attending physicians and residents. Examples of displaying appropriate and inappropriate demeanor included comments such as, “Dr. X exhibits a level of confidence that puts everyone at ease no matter the stressful situation,” and “Is quite impatient both with residents and staff in the operating room.” Positive and negative experiences with appropriate and inappropriate tone and dialogue were exemplified by comments such as, “Incredibly enthusiastic and truly listens to his patients,” and “Belittles residents in front of patients and staff.” Respect for opinions and contributions encompassed comments such as, “She made sure to involve students every step of the way,” but also included negative experiences, such as versions of a common refrain, “Frequently does not acknowledge the student’s existence.”

Table 1.

Identification of comments within sub-themes by medical students and residents for the theme of Creating a Positive Environment for Learning by Modeling Professional Behaviors. “Yes” or “No” denotes presence or absence of trainee comments under this sub-theme.

| Theme 1 | Sub-Themes | Comments About Attending Surgeons by: | Comments About Residents by Medical Students |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Residents | Medical Students | ||||||

| + | − | + | − | + | − | ||

| Creating a positive environment for learning by modeling professional behaviors | 1. Displaying appropriate demeanor, tone, and dialogue in clinical and teaching situations | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 2. Demonstrating respect for team members and patients | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| 3. Using evidence to make clinical decisions based on appropriate clinical knowledge | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | |

| 4. Demonstrating efficiency in clinical work | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | |

| 5. Engaging in effective patient interactions | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | |

Differences existed in the remaining three sub-themes of using evidence and clinical knowledge, efficiency, and direct interactions with patients. Interestingly, residents made negative comments about faculty regarding their knowledge and the time they spent engaging in patient care, exemplified by observations such as, “Evidence behind many clinical decisions was not clear,” “Over-ordered and over-consulted for patients,” and “I felt that there were too many examples of cautious, to the point of non-standard, care for our patients”. On the other hand, no medical students made negative comments in these sub-themes about their resident or faculty teachers.

Theme 2: Intentionally Engaging Learners in Training and Educational Opportunities

The second overall theme involved an educator’s purposeful use of different forms of educational practices and strategies while teaching in the clinical setting. Within this theme, nine sub-themes were identified from our analysis of trainee comments.

Utilizing direct instruction included statements that referred to efforts to directly teach skills or other clinical content.

Engaging in feedback and debriefing referred to comments related to helping trainees identify areas of strength in their performance and areas that could be targeted for improvement, and how this might occur and encompassed deliberate attempts to help trainees reflect on what went well, what could have been done better, and what they still needed to learn.

Being available for help and questions related to not only physical presence but also to general approachability and openness to questions.

Establishing learning performance expectations related to making explicit what trainees should be able to do and supporting them to accomplish this.

Articulating expectations for behaviors on a service included making clear what the role of the trainee was in supporting patient care.

Giving an appropriate level of autonomy included trainees’ comments about provision of an appropriate level of autonomy or responsibility in the operating room, in clinic, or during other patient interactions.

Treating as part of the team included comments addressing explicit attempts to include trainees as part of the care team in service of patient care and learning.

Involving in learning opportunities with patients encompassed comments that addressed the inclusion of trainees in direct patient care.

Showing consideration for career decisions included comments about trainee-educator interactions around career decisions and how educators received that information and discussed other specialties.

Similarities and Differences Between Medical Students and Residents

Table 2 identifies presence or absence (Yes/No) of positive or negative (+/−) comments made by medical students and residents for the second overarching theme of intentionally engaging learners. Clearly, medical students and residents shared many of the same perceptions with regard to engaging learners. Areas of shared perceptions included using effective direct instruction strategies, providing feedback and debriefing, and giving appropriate levels of autonomy based on a learner’s level of training. Shared areas also involved including all learners on the patient care team, involving them in learning opportunities as part of this care, and being available to provide help or answer questions. Representative positive comments by medical students and residents included, “She taught simple tasks: including use of the bovie and suturing with patience and valuable advice,” “Really made time for me to learn in her clinic and operating room,” and “She was approachable and open to questions.” In contrast, negative comments related to these aspects of the learning environment were, “Very limited independence to work in clinic,” and “Does not value resident opinion or input.”

Table 2.

Identification of comments within sub-themes of medical students and residents for the theme of Intentionally Engaging Learners in Training and Educational Opportunities. “Yes” or “No” denotes presence or absence of trainee comments under this sub-theme.

| Theme 2 | Sub-Themes | Comments About Attending Surgeons by: | Comments About Residents by Medical Students | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Residents | Medical Students | ||||||

| + | − | + | − | + | − | ||

| Intentionally engaging learners in training and educational opportunities | 1. Utilizing direct instruction | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 2. Engaging in feedback and debriefing | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | |

| 3. Being available for help and questions | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| 4. Establishing learning performance expectations | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| 5. Articulating expectations for behaviors on a service | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| 6. Giving an appropriate level of autonomy | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| 7. Treating as part of the team | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| 8. Involving in learning opportunities with patients | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| 9. Showing consideration for career decisions | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | |

Nevertheless, there were also important differences between medical students and residents related to various aspects of the learning environment. Medical students in particular described having negative experiences with the manner in which attending physicians and residents established learning outcomes and performance expectations on rotations, as exemplified by comments such as, “Some of those expectations, like in the operating room or clinic, were intimidating and unclear.” However, with regard to setting behavioral expectations for learners as team members on a service, both residents and medical students mentioned challenges, such as, “Didn’t set expectations or explain how things worked at the beginning of the rotation, and then was angered when students didn’t know what to do.” Finally, although both groups of learners commented on positive discussions with attending physicians regarding future career decisions, medical students also expressed some negative experiences with attending physicians around articulated specialty choices, typified by comments such as, “I was disappointed and frustrated that in two separate conversations he bashed specialties outside of surgery – one of which I want to go into.” Though these examples highlight the major similarities and differences in the focus of comments given by medical students and residents, a table of a larger selection of example comments for all sub-themes can be found in the Appendix.

Discussion

This study adds to the literature on medical education by examining what learners’ comments regarding their clinical teachers reveal about expectations for instruction in the surgical learning environment. This work is unique in that it compares similarities and differences in these themes between medical students on their surgery rotation and surgery residents. One theoretical perspective that can help us better understand educators’ roles in shaping the learning environment and is that of situated learning. Situated learning proposes that the sociocultural context of learning is essential. Particularly for adults in the workplace, meaningful learning occurs through social interactions and the development of relationships. Both medical students and residents are working to learn in communities of practice, in which they move from participating on the outskirts of practice into full participation while embracing the values and perspectives of the community.16 Because educators are modeling for medical students and residents what it means to be a part of this community, their attitudes, behaviors, and relationships are highly important. As such, clinical teachers are an essential part of shaping the learning environment, because they determine both what legitimate forms of participation in practice are, through the actions and ideas that they model, as well as how they allow trainees to legitimately participate in patient care in ways that are safe yet meaningful.

We learned that there are many important similarities in the themes generated by medical students and residents, underscoring universal elements of the learning environment that are important to all learners. Themes included being involved in meaningful patient care and taking time for direct teaching, as well as having opportunities for appropriate autonomy and receiving actionable feedback on their clinical performance. Both groups appreciated the modeling of professional behavior and demonstration of respect. Residents deemed it important to comment about their exposure to patient care and evidence-based, appropriate, clinical decision-making that was in the best interest of the patient.

Previous studies have attempted to understand how medical trainees evaluate their clinical teachers. A study by Lim and White17 found that Canadian medical students at a single institution commented on their faculty clinical instructors in ways that could be categorized as “Physician as Teacher,” “Physician as Physician,” and “Physician as Person.” The results of this study indicated that students commented on clinicians’ characteristics in terms of their teaching skills, their perceived effectiveness as a physician, and their overall humanistic characteristics. Our results support this interpretation of physician attributes that shape the learning environment. In our study, comments made by both groups of learners were also related to relationships of different kinds in the clinical environment. In particular, their comments highlight relationships between surgeons and patients; between surgeons and other medical providers as a standard part of patient care; and between surgeons and trainees resulting from a trusting teacher and student relationship. By creating a positive environment through professional behaviors, and purposefully engaging learners—our two overarching themes derived from the two groups’ comments—these relationships allow meaningful moments for learning to occur. Residents in our study also commented about how attending physicians modeled behaviors of what it means to “be a surgeon.” This is not surprising, since residents are not only learning surgical reasoning and skills, but also developing identities as surgeons. Medical students, on the other hand, are trying to learn surgical skills that may benefit them in the future, even though many will not become surgeons. For some medical students considering a career in surgery, the relationships with their surgical educators may be a critical factor in making that decision.

The establishment of explicit learning goals is important for a successful educational relationship and a positive learning environment. In a 1997 study by Vu et al.18 that evaluated medical student comments about internal medicine attending physicians, learners ranked the skills of their clinical instructors the lowest for ability to set and communicate learning goals. Our results suggest that this is still a problem in the field of surgery 20 years later; both medical students and residents in this study commented negatively on this topic. Medical students made it clear that even when expectations and learning goals were established, the expectations for their performance and responsibilities on surgical rotations were unclear; residents’ comments revealed that expected learning outcomes on different services were not made explicit. The persistence of this finding highlights the difficulty of setting learning goals in complex medical learning environments by teachers who most likely have never received formal training on how to do so, and the importance of providing professional development in basic educational best practices. Given the challenges that our clinical teachers face, including patient safety concerns, burnout, and limited time for interacting with medical students or residents, it is crucial to provide professional development and support for teaching and establishment of productive relationships.

Significance for professional development

This study has implications for professional development of both resident and attending teachers of surgery. It reinforces the notion that the relationships formed by residents and attendings with our learners, colleagues, and patients can have a tremendous influence on the learning environment. Consequently, based on our results highlighting the importance of modeling and engaging in deliberate teaching, we recommend development in the areas of leading effectually, communicating well, teaching effectively, and displaying clinical skills. Training for both residents and attending physicians on leading teams that include members with varied levels of expertise may help them incorporate learners into the surgical team better, as well as work more productively with other health care providers who bring different types of knowledge and skill sets to the team. We can help instructors to convey expectations by giving them guidelines for structuring conversations at the beginning of rotations, including the establishment of learning goals and expectations for what students’ relationships and interactions with others on the team will look like. Surgical educators may also participate in development programs that require ongoing self-reflection, engagement in peer observation, and receipt of feedback on their teaching in various settings, such as the operating room, clinic, or on rounds. Program directors can work with residents to establish desired learning outcomes and realistic expectations of autonomy, and surgical clerkship directors can elicit medical students’ expectations and explain the residents’ and attending physicians’ expectations before students begin working with the surgical teams.19 Finally, effective longitudinal continuing medical education programs, such as coaching, can be utilized to help with clinical issues.20 Ideally, these supports will also enhance wellbeing of trainees by increasing their feelings of effectiveness and self-efficacy as clinician educators.

Through studies such as ours, which heighten awareness of how trainees perceive their learning environment, we may influence medical students’ perceptions of surgical specialties and improve the wellness of residents. In addition, it is important to recognize that poor professional and teaching relationships can not only negatively impact the learning environment, but may also influence patient outcomes. A recent study found a significant correspondence between the number of co-worker-reported acts of unprofessional behavior and patients’ complications. Surgeons with one or more reports of unprofessional behavior had patients who were approximately 12–14% more likely to experience complications.21 Developing appropriate ways of relating to others in the surgery workplace benefits trainees by improving the learning environment, and also benefits patients. In medical and surgical training, as with any learning environment, we need to keep in mind that the overall experience is more than the sum of the individual components of planned experiences and interactions.22 It is also about the learner’s overall impression of how they integrate into the learning environment, and how they are welcomed, accepted, supported, and encouraged in their care of patients.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this study. First, it was conducted at a single institution with cultural norms, barriers, and facilitators that may not apply to all institutions. Second, only learners who chose to add open-ended comments contributed data. Those who provided comments may represent learners who are either very pleased or displeased with their experience. Therefore, findings might not apply to learners who would report having an average experience or that the learning environment was satisfactory, and these comments may also not give the full picture of trainees’ perceptions of the role of their clinical instructors in establishing the learning environment. Also, before providing open-ended comments, trainees were required to rate their teachers on attributes of their teaching, such as providing feedback and effectiveness as a role model, which may have influenced the comments that they then shared. Additionally, because the comments were provided in a de-identified manner, we cannot know the number of unique respondents, as some students or residents may have made multiple comments. Finally, we do not know how the timing of the survey administration might have impacted students’ perceptions of their instructors and the learning environment, for example if they completed their rotations at the beginning or end of the academic year. Despite these issues, there is much that surgical educators can derive from the results of this study.

Future Investigations

Potential future investigations include seeking faculty perspectives on the findings, and on their experiences with and expectations of students, to gain additional insight into how best to implement professional development and measure sustained impacts on the evaluations of the learning environment. Additionally, it may be worthwhile to ask the residents about their expectations for the medical students that they work with and teach. It would also be valuable to repeat this study in other specialties to see if there are similar underlying themes and to uncover ways that we may potentially support our clinical educators through interdisciplinary training.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that faculty development efforts in surgical education should target the areas of creating a positive environment for learning by modeling professional behaviors and intentionally engaging learners in training and educational opportunities, with a focus on interpersonal communication skills and executing teaching skills in a trusting student/teacher relationship. Although there are some commonalities in the observations and comments made by medical students and residents, there are also some important differences. Evaluation forms could be improved by focused questions which elicit additional information about modeling professional behaviors and intentionally engaging learners. Information on effective types of modeling and the most high-yield teaching strategies from the perspective of medical learners would allow for the design of interventions specific to the needs of the surgery instructors in order to facilitate skill development and support attending physicians’ and residents’ identities as clinician educators.

Highlights.

Medical students and residents focus on different qualities of learning environments

Teacher evaluation comments give insight into interventions for clinical educators

Engaging in and modeling successful relationships featured prominently in comments

Funding

This work was supported by the Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program, through the NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), grant UL1TR002373. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. Dr. Voils’ effort was supported by a Research Career Scientist award (RCS 14-443) from the Veterans Affairs Health Services Research & Development service.

Appendix

Residents’ and Medical Students’ Comments about Attending Surgeons and Residents as Clinical Instructors from Open-Ended Questions (illustrative examples of positive (+) and negative (−) comments)

| Themes | Sub-Themes | Comments About Attending Surgeons by: | Comments About Residents by Medical Students |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Residents | Medical Students | ||||||

| + | − | + | − | + | − | ||

| Creating a positive environment for learning by modeling professional behaviors | Displaying appropriate demeanor, tone, and dialogue in clinical and teaching situations | Phenomenal teacher--gentle, but firm where needs to be. It is difficult to describe, but Dr. X exhibits a level of confidence that puts everyone at ease no matter the stressful situation. | Is quite impatient both with residents and staff in the operating room, which means it is not long before the case is taken away from the resident and opportunities for teaching beyond observation fall to the wayside. | Worked cooperatively with team members. | Very hard to interact with. Seemed to be more interested in berating the resident rather than teaching. | By far the best example of a resident to model I worked with. | …instead of trying to work with me on the knowledge/skills, she’d just brush me up (take away the suture and give it to the M4 or do it herself and ignore my questions about how to do what she wanted). |

| Demonstrating respect for team members and patients | Respectful and values the opinions of other faculty, of nurses and APPs, and students and residents. | Uninterested in involving residents in patient care. | I found that she was very easy to talk with, and also very welcoming when integrating me into her team. | Spent most of my time sitting in the corner of the operating room. | She made sure to involve students every step of the way. | Frequently does not acknowledge the student’s existence. | |

| Using evidence to make clinical decisions based on appropriate clinical knowledge | Clinically she is excellent and has a wide knowledge base, which she actively shares with the residents. | Evidence behind many clinical decisions was not clear. | NC | NC | Both a scholar and a surgeon. Looks into research supporting different approaches and debunking common medical myths. | NC | |

| Demonstrating efficiency in clinical work | She is extremely efficient and I learned several useful tips for improving my efficiency in clinic. | Dr. X’s pace in the operating room is not always conducive for learning - I often feel rushed and behind which causes me anxiety and is frequently noted by operating room staff. | NC | NC | NC | NC | |

| Engaging in effective patient interactions | Perhaps the most striking thing I will take away from working with her is her unparalleled commitment to her patients. She is such a great role model in this regard in terms of how to facilitate care for your patients and to just do the right thing for them even when it’s not easy. | I felt that there were too many examples of cautious, to the point of non-standard, care for our patients. | His bedside manner is something I hope to emulate. | NC | Fantastic explanation to patients… | NC | |

| Intentionally engaging learners in training and educational opportunities | Utilizing direct instruction | Appreciate patience in allowing me to struggle while talking me through how to do something so I can actually learn. | There is no direct teaching or mentoring. | Dedicated time after rounds to teach specific topics that students needed or requested. | She was not really willing to teach ever and often told us we could leave the team room to go study; which makes sense, but it gave off the vibe that she just didn’t want/need medical students there. | She taught simple tasks: including use of the bovie and suturing with patience and valuable advice. She provided guidance. | Criticized us on our clinical ward skills without giving effective advice. |

| Engaging in feedback and debriefing | Very good at identifying resident weakness and directing improvement while operating. | Seems to have a hard time verbalizing to the resident what she wants them to do in the operating room. | He provided a humorous and memorable method of providing educational feedback. | NC | Provides constructive feedback with obvious intent to teach and withhold judgment. | Had a tendency to make students feel like an idiot if questions or plans were not correct without much helpful feedback. | |

| Being available for help and questions | He is always there to back up the residents if needed, but he also gives them room to make decisions on their own and develop their clinical acumen. | He was minimally available to ask questions to and often would have to step away during rounds to go do something else. | She was approachable and open to questions. | NC | Always available for help and willing to answer questions. | NC | |

| Establishing learning performance expectations | She has high expectations of her residents, but allows them to make mistakes and learn from them. |

NC | Made sure that students knew what they needed to know. | Never set specific expectations for students. | Do not lower your expectations! | Working with her was not always the easiest because of her high expectations. Some of those expectations, like in the operating room or clinic, were intimidating and unclear… | |

| Articulating expectations for behaviors on a service | NC | [Expectations were] not voiced or enacted while starting the rotation. | NC | Didn’t set expectations or explain how things worked at the beginning of the rotation, and then was angered when students didn’t know what to do. | Great chief, who had reasonable expectations and didn’t micromanage. | Made us feel like we were a burden and didn’t teach us how to help rather expected us to know. | |

| Giving an appropriate level of autonomy | Has a high level of confidence in her own operating skills to where she will allow a great deal of intraoperative freedom to residents… | He mainly taught by show and tell and let me participate minimally in most of his cases. | He included me in patient interviews during clinic. | Very limited independence to work in clinic. | Treated me with respect and gave me an appropriate level of responsibility. | She was very impatient with me, expecting me to do/know things that had never been taught… | |

| Treating as part of the team | Inclusive of me as a member of the team. | Does not value resident opinion or input. | Had a discussion with me in the operating room. Saw me as a person | Wasn’t receptive to questions. | Empowered students to be involved and encouraged them to develop critical thinking. | He would cut students off during presentations and tell us we were doing a bad job without giving us a chance to try. | |

| Involving in learning opportunities with patients | Dr. X really allows for great intern participation in operating room cases as well as on the floor. |

Was inattentive during rounds and sometimes wouldn’t even exam or talk to patients. | Really made time for me to learn in her clinic and operating room. | Limited chances to interview and conduct physical exams | A great teacher who was really patient with her explanations during both surgery and rounds. |

… I would be more fearful of irritating her than actually being engaged and learning. | |

| Showing consideration for career decisions | He gave me great career advice that will benefit me in the future. | NC | Would provide professional advice on career planning. | I was disappointed and frustrated that in 2 separate conversations he bashed specialties outside of surgery – one of which I want to go into. | NC | NC | |

Notes: NC = No comment

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no proprietary or commercial interest in any product mentioned or concept discussed in this article.

References

- 1.Fingerhood M, Wright SM, Chisolm MS. Influencing Career Choice and So Much More: The Role Model Clinician in 2018. Journal of graduate medical education. 2018. April;10(2): 155–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kenny NP, Mann KV, MacLeod H. Role modeling in physicians’ professional formation: reconsidering an essential but untapped educational strategy. Academic Medicine. 2003. December 1;78(12): 1203–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME). Common Program Requirements. 2019. Accessed on December 17, 2019 at: https://www.acgme.org/What-We-Do/Accreditation/Common-Program-Requirements

- 4.Castillo-Angeles M, Watkins AA, Acosta D, Frydman JL, Flier L, Garces-Descovich A, Cahalane MJ, Gangadharan SP, Atkins KM, Kent TS. Mistreatment and the learning environment for medical students on general surgery clerkship rotations: What do key stakeholders think?. The American Journal of Surgery. 2017. February 1;213(2):307–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brandford E, Hasty B, Bruce JS, Merrell SB, Shipper ES, Lin DT, Lau JN. Underlying mechanisms of mistreatment in the surgical learning environment: a thematic analysis of medical student perceptions. The American Journal of Surgery. 2018. February 1;215(2):227–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marshall DC, Salciccioli JD, Walton SJ, Pitkin J, Shalhoub J, Malietzis G. Medical student experience in surgery influences their career choices: a systematic review of the literature. Journal of surgical education. 2015. May 1;72(3):438–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bhutta M, et al. “A Survey of How and Why Medical Students and Junior Doctors Choose a Career in ENT Surgery.” The Journal of Laryngology & Otology, vol. 130, no. 11, 2016, pp. 1054–1058., doi: 10.1017/S0022215116009105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang Y, Li J, Wu X, Wang J, Li W, Zhu Y, Chen C, Lin H. Factors influencing subspecialty choice among medical students: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ open. 2019. March 1;9(3):e022097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Edmondson EK, Kumar AA, Smith SM. Creating a culture of wellness in residency. Academic Medicine. 2018. July 1;93(7):966–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raj KS. Well-being in residency: a systematic review. Journal of graduate medical education. 2016. December;8(5):674–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Low ZX, Yeo KA, Sharma VK, Leung GK, McIntyre RS, Guerrero A, Lu B, Lam SF, Chiang C, Tran BX, Nguyen LH. Prevalence of burnout in medical and surgical residents: a meta-analysis. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2019. January;16(9): 1479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lases SS, Slootweg IA, Pierik EG, Heineman E, Lombarts MJ. Efforts, rewards and professional autonomy determine residents’ experienced well-being. Advances in Health Sciences Education. 2018. December 1;23(5):977–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoff TJ, Pohl H, Bartfield J. Creating a learning environment to produce competent residents: the roles of culture and context. Academic Medicine. 2004. June 1;79(6):532–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wright SM, Kern DE, Kolodner K, Howard DM, Brancati FL. Attributes of excellent attending-physician role models. New England Journal of Medicine. 1998. December 31;339(27):1986–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative health research. 2005. Nov;15(9):1277–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rashid P Surgical education and adult learning: integrating theory into practice. F1000Research. 2017;6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lim DW, White JS. How do surgery students use written language to say what they see? A framework to understand medical students’ written evaluations of their teachers. Academic Medicine. 2015. November 1;90(11):S98–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vu TR, Marriott DJ, Skeff KM, Stratos GA, Litzelman DK. Prioritizing areas for faculty development of clinical teachers by using student evaluations for evidence-based decisions. Academic Medicine. 1997. October 1;72(10):S7–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sutkin G, Wagner E, Harris I, Schiffer R. What Makes a Good Clinical Teacher in Medicine? A Review of the Literature. Acad Med. 2008;83(5):452–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Greenberg JA, Jolles S, Sullivan S, et al. A structured, extended training program to facilitate adoption of new techniques for practicing surgeons. Surg Endosc. 2018;32(1):217–224. doi: 10.1007/s00464-017-5662-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cooper WO, Spain DA, Guillamondegui O, Kelz RR, Domenico HJ, Hopkins J, Sullivan P, Moore IN, Pichert JW, Catron TF, Webb LE. Association of coworker reports about unprofessional behavior by surgeons with surgical complications in their patients. JAMA Surgery. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaufman DM, Mann KV. Understanding medical education: evidence, theory and practices. 2010; Wiley-Blackwell Oxford, UK. [Google Scholar]