Abstract

Objective

There is a dearth of Canadian-based literature on children referred to treatment services following maltreatment exposure. In order to inform assessment, intervention, and program development to improve outcomes, insight into the demographics and mental health needs of this population is required.

Methods

A retrospective file review of 176 children and youth who were referred for assessment and treatment at a mental health partner agency within a Canadian Child Advocacy Centre was conducted from January 2016 to June 2017. A standardized protocol was developed to extract data on family and child demographic characteristics, type of maltreatment, other adversity exposure, presenting concerns of the child, and mental health service utilization.

Results

The majority of children were female (66.5%), 4.5% were 0 to <5 years, 66.5% were 5 to <13 years, and 29.0% were 13 to <18 years of age. More than half of the children (53.4%) had multiple forms of maltreatment, with 67% exposed to sexual abuse. Exposure to other forms of adversity was also common, including domestic violence (53.4%) and parental mental health difficulties (52.3%). Most children had more than five presenting concerns at the time of referral, and most went on to receive intervention services. Sixty-nine percent of families had not previously received child mental health treatment, although 41.5% had prior child welfare involvement. Thirty percent of families ended treatment prematurely.

Conclusions

The current study illustrates the complex profile and mental health needs of children referred for treatment following maltreatment exposure. Results may have implications for clinical care improvement that support maltreated children.

Key Words: child abuse, mental health, assessment, treatment

Résumé

Objectif

Il y a un manque de littérature canadienne sur les enfants adressés à des services de traitement par suite d’une exposition à la maltraitance. Afin d’éclairer l’évaluation, l’intervention et l’élaboration de programmes pour améliorer les résultats, il faut discerner les données démographiques et les besoins de santé mentale de cette population.

Méthodes

Une revue rétrospective des dossiers de 176 enfants et jeunes qui ont été adressés pour une évaluation et un traitement à un organisme partenaire de santé mentale dans un Centre canadien d’appui aux enfants a été menée de janvier 2016 à juin 2017. Un protocole normalisé a été élaboré afin d’extraire les données sur les caractéristiques démographiques de la famille et de l’enfant, le type de maltraitance, une autre forme d’exposition à l’adversité, les préoccupations présentées par l’enfant, et l’utilisation des services de santé mentale.

Résultats

La majorité des enfants étaient de sexe féminin (66,5 %), 4,5 % avaient de 0 à 5 ans, 66,5 % avaient de 6 à 12 ans, et 29,0 % avaient de 13 à 18 ans. Plus de la moitié des enfants (53,4 %) souffraient de multiples formes de maltraitance, et 67 % étaient exposés à l’abus sexuel. L’exposition à d’autres formes d’adversité était aussi commune, notamment la violence familiale (53,4 %) et les difficultés de santé mentale parentales (52,3 %). La plupart des enfants avaient plus de 5 préoccupations actuelles au moment d’être adressés, et la plupart a poursuivi et reçu des services d’intervention. Soixante-neuf pour cent des familles n’avaient pas précédemment reçu de traitement pour la santé mentale des enfants, même si 41,5 % avaient auparavant été impliquées dans les services d’aide à l’enfance. Trente pour cent des familles ont mis fin au traitement prématurément.

Conclusions

La présente étude illustre le profil et les besoins de santé mentale complexes des enfants adressés à un traitement par suite d’une exposition à la maltraitance. Les résultats peuvent avoir des implications sur l’amélioration des soins cliniques qui soutiennent les enfants maltraités.

Mots clés: maltraitance des enfants, santé mentale, évaluation, traitement

Introduction

Epidemiological studies in Canada estimate that 30% of children are exposed to maltreatment (i.e., emotional, physical, and sexual abuse and neglect) before the age of 18 (Afifi et al., 2014; McDonald, Kingston, Bayrampour, & Tough, 2015). This alarmingly high rate of exposure to abuse and neglect is associated with increased risk for severe health and mental health difficulties across the lifespan, including mood and anxiety disorders, physical health problems, and increased risk of self-harm and suicide (Afifi et al., 2016; Afifi et al., 2014; Cicchetti & Toth, 2016; Heim, Shugart, Craighead, & Nemeroff, 2010; McDonald et al., 2015; Messman-Moore & Bhuptani, 2017; Toth & Manly, 2019). The estimated annual direct and indirect cost of child maltreatment in high-income countries worldwide is substantial (Bowlus, McKenna, Day, & Wright, 2003; Ferrara et al., 2015). The detrimental consequences associated with exposure to child maltreatment suggest that prevention and intervention strategies are needed to mitigate the negative impact of these experiences.

One response to improving management and treatment for children who have been maltreated is the Child and Youth Advocacy Model, which has been shown to improve access to, and coordination of, psychological and physical health services (Shaffer, Smith, & Ornstein, 2018). Since 2010 the Canadian Government has invested in and prioritized the creation of Child Advocacy Centres (CACs) (McDonald, Scrim, & Rooney, 2013). Through a partnership model, the goal of CACs is to reduce system-induced trauma (i.e., distress that is experienced as a result of poor coordination among systems) by providing a single location where families impacted by maltreatment can seek law enforcement, prosecution, child protection, victim advocacy, and mental health treatment (Department of Justice, Canada, 2018; Jackson, 2004; Louden & Elliott, 2018). Historically, CACs have primarily served children who have been sexually abused. However, most CACs now offer services for multiple child maltreatment types.

Although access to timely mental health assessment and treatment for children who have been maltreated is critical for mitigation of future health and psychosocial risk (Leenarts, Diehle, Doreleijers, Jansma, & Lindauer, 2013; Wamser-Nanney, Scheeringa, & Weems, 2016), there has been limited information published about mental health treatment within CACs in Canada (Dubov & Goodman, 2017; Shaffer et al., 2018). In addition to the limited data on mental health assessment and treatment from Canadian CACs, knowledge about the types of maltreatment and other adversities experienced by referred children can help guide the types of mental health services that should be offered. For example, children exposed to maltreatment are also frequently exposed to other forms of adversity such as parent mental health difficulties and exposure to domestic violence (Finkelhor, Turner, Shattuck, & Hamby, 2013, 2015). It is important to determine the extent of maltreatment and adversity experienced by children referred for mental health treatment at CACs to guide management and practitioners in implementing and developing mental health services that take into consideration the cumulative and potentially complex trauma that clients have experienced.

The objective of the current study was to better understand the clinical needs of the children, youth, and their families assessed and treated for mental health concerns within a partner mental health agency at a Canadian CAC. Findings from the current study can be used to guide program development and the practice of individual practitioners and multidisciplinary teams who serve this population.

Methods

Program Description

Data for the current study was obtained from a mental health service, partnered with a CAC in an urban city in Western Canada. The mental health service partner within the CAC is funded through the provincial health authority and is one of eight partner agencies within the CAC. The CAC is a non-profit organization that provides wrap-around services to assess, investigate, intervene, and support survivors of child maltreatment. When a child is referred to the CAC, a referral can be initiated to the mental health service to assess the psychological impact of the maltreatment on the child and their family and provide treatment to address trauma symptoms. Children can also be referred by a caregiver or community agency.

The mental health service reports using evidence-informed practices to assess and treat the most complex and severe child maltreatment cases in the region. Referral criteria include that the child has experienced sexual abuse, or severe and complex physical abuse or neglect. Severe and complex physical abuse refers to physical abuse that caused injuries, involved the use of objects, or necessitated involvement from law enforcement or medical professionals. Severe and complex neglect refers to chronic deprivation of basic physical or emotional needs over a sustained period of time. Children referred to the mental health service must also be under the age of 18 years and be exhibiting emotional and/or behavioural challenges thought to be related to the maltreatment they experienced.

There are approximately 10 full and part-time clinicians within the mental health service, all of whom are registered psychologists or social workers with a minimum of a Master’s degree. Clinicians within the mental health service generally follow standardized assessment and treatment processes. For example, for assessments, information on the child’s current functioning, family functioning, and response to the maltreatment exposure is collected. Based on information collected during the assessment, an individualized approach based on the best evidence available is recommended to families (e.g., trauma-focused cognitive behavior therapy (Cohen, Mannarino, & Deblinger, 2006), parent-child interaction therapy (McNeil & Hembree-Kigin, 2010), Circle of Security Intervention (Powell, Cooper, Hoffman, & Marvin, 2014)).

Participants

A retrospective file review of children ages 0–17 (n = 176) referred to the mental health service between January 2016 and June 2017 was conducted. Patients were included in the case file review if their file was closed (i.e., they were no longer receiving treatment services). Information was extracted from files between March 2017 and October 2018. Given that the mental health service provides mental health services to 175 cases annually, the current sample size of n=176 was deemed representative of the clinic population.

Procedure

In accordance with guidelines for conducting a systematic retrospective file review (Gearing, Mian, Barber, & Ickowicz, 2006) an initial “convenience sample” was first evaluated. First, research questions were conceptualized in consultation with clinicians within the partner agency and a literature review for existing evidence on characteristics and treatment needs of children referred to CACs in Canada was conducted. Second, a proposal was developed which included the study methodology and variable operationalization. Third, a standardized data extraction protocol was piloted on 10 files. Two research assistants, blind to study hypotheses in order to decrease bias, were trained in data extraction (Vassar & Holzmann, 2013). Their extraction was monitored over the course of the study. Each file was then reviewed by a primary data extraction coder. Information about the maltreatment history, exposure to adversity, presenting symptoms, treatment characteristics, and demographic history was extracted. Research assistants extracted information from a standard intake record form, clinician reports, case notes, questionnaires completed by children and families, as well as any medical documents included in the case files. Research assistants used a data extraction reference manual that listed each variable and its operationalization in order to increase consistency across coders. In line with behavioural research recommendations (Hruschka et al., 2004), a second coder extracted data from 20% of case files for inter-rater reliability purposes. Reliability statistics are reported in the measures section. When discrepancies were identified, the two coders met to resolve discrepancies by consensus and the lead author was consulted as needed to resolve ambiguities. The consensus code was entered into the final database. Ethics approval was obtained from the institutional review board and a waiver of consent for retrospective file review was obtained.

Measures

Demographic variables

Demographic information was gathered from the intake form, which includes information on child age, child sex, parent age, parent abuse history, family composition, and family financial information.

Maltreatment types and duration

Each maltreatment type was coded as “0” when not present in the child’s file and “1” when present. Physical abuse was operationalized as “being pushed, grabbed, slapped, hit, or injured where marks were left” by an adult. Sexual abuse was operationalized as “being touched sexually, being forced to touch someone sexually, or attempt or having oral, anal, or vaginal intercourse with a child”. Emotional abuse was defined as “being frequently sworn at, insulted, put down or humiliated, or a child being afraid they may be physically hurt”. Emotional neglect was defined as “a child feeling like no one in their family loved them or that they did not have the emotional support of a family member”. Physical neglect included when a child did not have enough to eat, wore dirty clothes, or did not have anyone to protect/take care of them. The duration of maltreatment subtypes was coded in number of months. Reliability among the two coders for was good (ICC =.82).

Other adversity types and duration

Other forms of child adversity collected from the file included parental separation or divorce, exposure to domestic violence, parent/caregiver substance use difficulty, parent/caregiver mental illness or attempted suicide, as well as parental/caregiver incarceration. Each item was coded as “0” when not present in the child’s file and “1” when present. This list of adversities has demonstrated strong predictive validity in previous child maltreatment literature (Finkelhor et al., 2013). Reliability among the two coders was good (ICC =.89).

Alleged offender characteristics

The sex and relationship to the child of the alleged offender was recorded as well as whether the child or youth who was victimized disclosed the abuse. When there was more than one offender, this was captured as “multiple offenders” for offender sex and the primary relationship to the child was recorded (e.g., multiple siblings were categorized as “sibling”).

Presenting concerns

A list of 15 presenting trauma symptoms were reported by the child’s referral source during the intake process. These items were derived from symptoms identified in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for the diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Presenting concerns were coded as either “0” when not occurring at the time of referral or “1” when present. Reliability among two independent coders was excellent (ICC = .90).

Mental health service utilization

Referral sources reported on the child’s previous and current mental health treatment. Information about the number and types of mental health services accessed, including assessment and treatment, was extracted from the child’s file. The type of child treatment received was collected. If the child completed the full protocol of an evidenced informed intervention such as TF-CBT or Connect Parenting Group, they were included in that category. Individual trauma treatment refers to treatment provided and tailored to the child’s treatment needs. Individual trauma treatment may have included components of other child treatment, such as Trauma-Focused CBT, but either did not follow the protocol in its entirety or included other treatment elements. Whether the child completed the recommended treatment, ended treatment prematurely, and the reason for ending treatment prematurely were also coded.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics were calculated, including the count (percentage) for categorical variables, as well as the mean, standard deviation, and range for continuous variables. A chi-square statistic was used to explore whether statistically significant differences occurred between proportions of maltreatment and adversity types for male and female children.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics of children and families referred to the mental health service

Demographic characteristics can be found in Table 1. The majority of children referred were female (66.5%) and in middle childhood between the ages of 6–12 years (66.5%). In the current sample, the majority of children were born in Canada (97.2%) and were in the care of a biological parent (76.7%). On average, parents were in their late 30s and the majority were separated or divorced (70.5%). Approximately 15% of families self-identified as having financial struggles. As detailed in Table 1, a high proportion of mothers whose child was referred to the mental health service had experienced childhood maltreatment themselves (60.8%).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the referred families

| Characteristic | % (n) |

|---|---|

| Child agea | |

| 0 to <5 years | 4.5 (8) |

| 5 to <13 years | 66.5 (117) |

| 13 to <18 years | 29.0 (51) |

| Child sex | |

| Male | 33.0 (58)) |

| Female | 66.5 (117 |

| Transgender | 0.5 (1) |

| Child born outside Canada | |

| Yes | 2.8 (5) |

| No | 97.2 (171) |

| Primary caregiver | |

| Biological parent(s) | 76.7 (135) |

| Foster parent | 6.2 (11) |

| Guardian | 11.4 (20) |

| Other (e.g. extended family, stepparent) | 5.7 (10) |

| Parent separated/divorced | |

| Yes | 70.5 (124) |

| No | 29.5 (52) |

| Financial struggles | |

| Yes | 14.8 (26) |

| No | 84.1 (148) |

| Missing | 1.1 (2) |

| Maternal abuse history | |

| Yes | 60.8 (107) |

| No | 38.6 (68) |

| Missing | 0.6 (1) |

| Paternal abuse history | |

| Yes | 29.5 (52) |

| No | 69.9 (123) |

| Missing | .6 (1) |

Mean: 10.4 years, SD=3.6 years, min=3.8 years, max: 17.7 years. Mean maternal age: 37.2 years, SD=6.5, min=23.4, max-59.9. Mean paternal age: 39.9, SD=6.5, min=26.5, max=63.8.

Child maltreatment and adversity characteristics

Child maltreatment, adversity and alleged offender

Child maltreatment characteristics and proportions of maltreatment by child sex are reported in Table 2. Sexual abuse was the most common form of maltreatment (67.0%). Female children were more likely to experience physical abuse (56.7% versus 43.3%) and sexual abuse (78.6% versus 21.4%) than male children (See Table 2). Children and youth were reported to have experienced several other forms of adversity, with domestic violence being the most frequent (53.4%) after parent separation or divorce (70.5%). Cumulative maltreatment and offender characteristics are reported in Table 3. The majority (53.4%) of children in the sample were reported to have experienced more than one form of maltreatment. There was a range in maltreatment duration across types, with the highest average duration occurring for neglect: 64.71 months (SD=51.40). The majority of alleged offenders in the current sample were male (72.7%). The relationships between the child and the offender varied greatly. The most common relationships between the child and offender were a biological parent (31.2%).

Table 2.

Frequency of maltreatment and adversity characteristics by child sex

| Characteristic | (n=176) % (n) |

Male (n=58) (%) |

Female (n=117) (%) |

X2 a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maltreatment Types | ||||

| Emotional abuse | 36.4 (64) | 42.2 | 57.8 | 3.73 |

| Physical abuse | 34.1 (60) | 43.3 | 56.7 | 4.23* |

| Sexual abuse | 67.0 (118) | 21.4 | 78.6 | 22.09** |

| Emotional neglect | 26.7 (47) | 43.5 | 56.5 | 3.01 |

| Physical neglect | 34.1 (60) | 41.7 | 58.3 | 2.99 |

| Other Adversity Types | ||||

| Exposure to domestic violence | 53.4 (94) | 33.3 | 66.7 | .003 |

| Parent substance use difficulty | 43.2 (76) | 37.3 | 62.7 | 1.04 |

| Parent with mental illness | 52.3 (92) | 36.3 | 63.7 | .83 |

| Parent incarcerated | 18.2 (32) | 38.7 | 61.3 | .53 |

| Parent separated/divorced | 70.5 (124) | 35.0 | 65.0 | .62 |

Note: Maltreatment and adversity categories are not mutually exclusive.

These analyses are based on a sample n=175.

p < .05,

p <.001

Table 3.

Maltreatment and offender characteristics

| Characteristics | % (n) | Mean (SD) | Min, Max |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Maltreatment Types | 1.98 (1.26) | 0, 5 | |

| 0–1 | 46.6 (82) | ||

| 2 | 22.2 (39) | ||

| 3 | 16.5 (29) | ||

| 4 | 10.8 (19) | ||

| 5 | 3.9 (7) | ||

| Maltreatment duration (months) | |||

| Physical abuse | 59.92 (45.27) | 3, 160 | |

| Sexual abuse | 27.33 (27.65) | .03, 99 | |

| Emotional abuse | 63.47 (48.47) | 2, 160 | |

| Physical/emotional neglect | 64.71 (51.40) | 2, 192 | |

| Alleged offender sex | |||

| Male | 72.7 (128) | ||

| Female | 9.7 (17) | ||

| Multiple offenders | 13.1 (23) | ||

| Missing | 4.5 (8) | ||

| Alleged offender relationship | |||

| Biological parent | 31.2 (55) | ||

| Acquaintance | 15.3 (27) | ||

| Extended family | 14.8 (26) | ||

| Sibling | 12.5 (22) | ||

| Friend | 6.3 (11) | ||

| Guardian | 2.3 (4) | ||

| Othera | 13.1 (23) | ||

| Missing | 4.5 (8) | ||

Note: Maltreatment categories are not mutually exclusive.

For example, babysitter, childcare provider, or stranger.

Across abuse types, the offender sex was as follows: 54.4% male for physical abuse, 88.0% male for sexual abuse, 61.9% male for emotional abuse, 52.6% male for physical neglect, and 65.2% male for sexual abuse. With regards to most likely offender across abuse types, parents were the most likely offender for physical abuse (60.4%), emotional abuse (52.4%), emotional neglect (45.6%), and physical neglect (44.8%). For sexual abuse, the most common offender was either an extended family member (35.6%), a sibling (18.6%) or an acquaintance (14.4%). In the majority of cases, there was one primary offender reported (79.5%), with 15.3% having multiple offenders.

Presenting Concerns

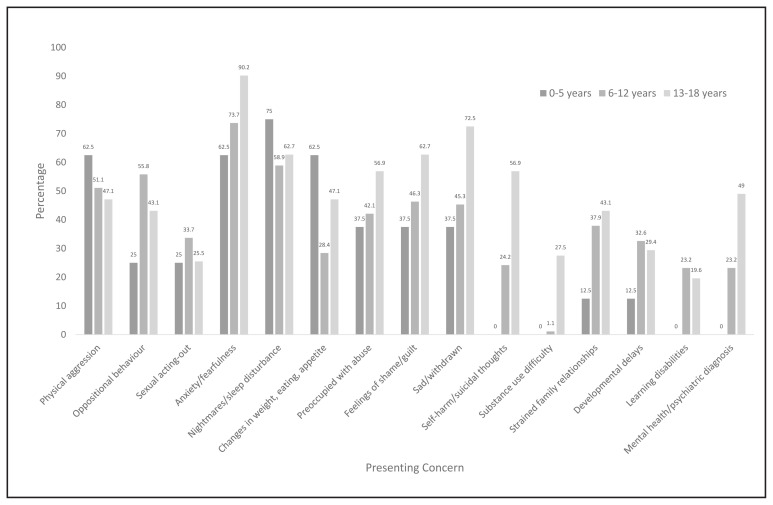

Children’s presenting symptoms at the time of referral categorized by age (0 to <5 years, 5 to <13 years, and 13 to <18 years) are depicted in Figure 1. The majority of children referred (54%) had five or more presenting concerns.

Figure 1.

Presenting concerns at time of referral by age for children referred for mental health treatment at the Child Advocacy Centre.

Previous Service Utilization

Previous and current family mental health service use are presented in Table 4. Less than 20% of children were returning clients. A high percentage of families had past child welfare involvement (41.5%), as well as current child welfare involvement at the time of referral (47.7%). Twenty-one percent of families had previously accessed child assessment services and 31% had previously received child treatment services. Comparably, few families were accessing child assessment (5.7%) or treatment services (17.6%) outside the CAC at the time of referral.

Table 4.

Service Characteristics of Referred Families

| Characteristic | %(n) |

|---|---|

| Returning client | |

| Yes | 17.0 (30) |

| No | 83.0 (146) |

| Previous services received | |

| Child welfare | 41.5 (73) |

| Child assessmenta | 21.0 (37) |

| Child treatment | 31.3 (55) |

| Parenting support | 6.8 (12) |

| Child residential treatment | 4.5 (8) |

| Developmental services | 4.5 (8) |

| Housing | 3.4 (6) |

| Missing | 35.2 (62) |

| Services at time of referral | |

| Child welfare | 47.7 (84) |

| Child assessmenta | 5.7 (10) |

| Child treatment | 17.6 (31) |

| Parenting support | 13.1 (23) |

| Child residential treatment | 3.4 (6) |

| Developmental services | 1.1 (2) |

| Housing | 2.3 (4) |

| Missing | 35.2 (62) |

| Assessment conducted at the Child Abuse Service | |

| Yes | 96 (169) |

| No | 4.0 (7) |

| Treatment conducted at the Child Abuse Service | |

| Yes | 51.7 (91) |

| No | 48.3 (85) |

| Type of treatment received | |

| Individual trauma therapy | 63.7 (58) |

| Trauma-focused CBT | 28.6 (26) |

| Parent/caregiver consultation | 27.5 (25) |

| Circle of Security | 12.1 (11) |

| Connect parent group | 8.8 (8) |

| Family Therapy | 4.4 (4) |

| Parent-Child Interaction therapy | 2.8 (5) |

| Other child treatment | 2.2 (2) |

| Sexual behavior treatment | 1.1 (1) |

| Treatment Completion Status | |

| Completed recommended treatment | 41.5 (73) |

| Treatment recommended, but not completedb | 25.6 (45) |

| Treatment not needed or received elsewhere | 24.4 (43) |

| Treatment inappropriatec | 8.5 (15) |

Note: Service categories and treatment types are not mutually exclusive.

Child assessment refers to psychiatric, psychological, or developmental assessment.

Reasons for not completing recommended treatment included not interested in treatment (13), no contact/lost contact (11), scheduling difficulties (3), moved (4), fear of child welfare involvement (1), missing (13).

Examples for treatment being deemed inappropriate include if the child was not ready to engage in trauma treatment or if the family environment was not stable enough to engage in trauma therapy.

Mental Health Service Use

A total of 169 families received assessment services at the mental health service and 91 subsequently received some form of treatment. The majority of families accessing treatment received individual trauma therapy (63.7%). There was large variability in the assessment and treatment duration for children and families seen within the mental health service. The average assessment duration was 1.42 months (Min, Max=0,8 months) and the average treatment duration was 1.65 months (Min, Max=0, 17 months). On average, children attended 3.63 (SD=2.3) assessment sessions and 4.45 (SD=7.0) treatment sessions.

Treatment Completion

Following a comprehensive assessment, 118 families were recommended mental health treatment. Of families who were recommended treatment, 61.9% completed treatment (73/118) and 30.1% (45/118) ended treatment prematurely. The primary reasons for premature withdrawal from treatment was not being interested in treatment (n=13, 28.9%).

Discussion

The current study examined the child and family characteristics, presenting concerns, and the mental health needs of a sample of children receiving mental health services within a Canadian CAC. Below we discuss study findings as well as implications for clinical care improvement and program development.

Child and Family Characteristics

Consistent with an earlier descriptive study from a CAC (Carlson, Grassley, Reis, & Davis, 2015), most children referred were in middle childhood, female, residing with their biological parent, and had experienced sexual abuse. These findings are also consistent with a Canadian report indicating that most children referred to CACs are female and have been sexually abused (Louden & Elliott, 2018). In the current study, female children were more likely to have experienced sexual and physical abuse than males. While higher rates of sexual abuse in females are consistent with previous literature, males typically experience higher physical abuse rates than females (MacMillan, Tanaka, Duku, Vaillancourt, & Boyle, 2013). It is not known whether the sex difference in physical abuse patterns are different in the community served by this CAC or whether physically abused boys are less likely to be referred to this CAC. The high prevalence (58.5%) of perpetrators who were a relative of the child (i.e. parents, sibling, or extended family member) is consistent with epidemiological estimates from the Canadian Incidence Survey of Child Abuse and Neglect that found 60% of sexual abuse cases to involve perpetrators who are related to the child (Trocmé et al., 2005).

Findings with regards to caregiver age were also consistent with previous findings from the Ontario Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect (OIS) (Fallon et al., 2020), which reported that 51% of caregivers of maltreated children were between 31 and 40 years of age. Only 15% of families in the current study identified having financial concerns, which is also consistent with reports from the OIS that found that most caregivers of maltreated children had households with adequate full-time income. The consistency in demographic and abuse characteristics of children referred for mental health services at the current CAC may support using a standardized approach to assessment and treatment across CACs. Furthermore, given that many of the presenting concerns and characteristics are similar across children, this may warrant the implementation of more generalized approaches to treatment, including parenting groups or child trauma groups. A streamlined and standardized approach to assessment, as well as treatment that would allow the provision of services to multiple families at the same time, may increase the capacity of mental health services within CACs.

A high percentage of mothers in the current study (61%) had a history of maltreatment themselves, pointing to the intergenerational cycles of adversity and abuse perpetuated within families. A modest association between parental history of maltreatment and their children’s experiences of maltreatment has been demonstrated meta-analytically (Madigan et al., 2019). Although mechanisms of the intergenerational transmission of maltreatment need to be elucidated (Alink, Cyr, & Madigan, 2019), children of maltreated mothers are at increased risk for maltreatment themselves and may benefit from early interventions (St-Laurent, Dubois-Comtois, Milot, & Cantinotti, 2019). Mothers who have their own trauma histories may struggle to engage in supportive parenting behaviours during their child’s trauma treatment (Cohen, Hien, Batchelder, 2008). Given that parent support during child trauma treatment is associated with improved treatment outcomes (Yasinski, Hayes, Ready, Cumming, Deblinger, 2016) and increased likelihood of treatment completion (Eirich, Racine, Garfinkel, Dimitropoulos, & Madigan, 2020), it may be beneficial for mental health services within CACs to assess parental trauma history, as well as ongoing trauma symptoms. Mental health services within CACs may consider developing and providing services that support parent mental health needs to increase parental capacity to support their child who is engaging in trauma treatment.

This study also found that nearly 50% of children referred to the mental health service had experienced other forms of child adversity beyond maltreatment, such as having a parent with a mental health problem, a parent with substance use difficulties, or domestic violence exposure. These findings are consistent with previous work demonstrating that child maltreatment and dysfunction within the family environment often co-occur (Dong, Anda, Felitti 2004). Trauma treatment that engages parents may retain families more successfully (Dorsey et al., 2014). Since its inception, the mental health service has evolved to provide many parenting related programs to bolster parent skills and support. The integration of interventions within CACs that address parent mental health needs, and the parent child-relationship, may contribute to higher levels of treatment engagement and ultimately, more successful treatment outcomes.

Presenting Concerns

Children in the current study represented some of the most severe child maltreatment cases: most children presented with upwards of five trauma symptoms, which has been referred to as complex trauma (Cook et al., 2005). Both exposures to child maltreatment and adversity are risk factors for developing trauma symptoms (Racine, Eirich, Dimitropoulos, Hartwick, & Madigan, 2020). Children with complex traumas have elevated risk in cognitive, biological, behavioural, and affective regulatory areas, including interpersonal difficulties, emotional regulation problems, memory impairments, and substance misuse (Cook et al., 2005). These findings highlight the importance of mental health services that address both trauma symptoms and broader mental health difficulties. Children with varying degrees of trauma exposure may require different treatment lengths and intensities. For instance, children with a single instance of maltreatment may require a shorter intervention duration than children with multiple maltreatment experiences (Beal et al., 2019). Thus, considering treatment options based on the maltreatment types and severity may be a useful clinical approach.

It is well established that presenting symptoms following child maltreatment may differ across developmental stages. There are also unique challenges with assessing trauma symptoms in young children, including limited self-report, poor parental ability to recognize internal states, and caregivers confounding their own trauma symptoms with those of their child (Stover & Berkowitz, 2005). As seen in the current study, symptoms displayed by young children following maltreatment may also differ from those of older children and include behaviour difficulties (e.g., aggression), nightmares and sleep difficulties, changes in appetite, or increased emotionality (Fraser et al., 2019). Assessment measures that are developmentally appropriate and screening tools validated for use with various age groups may help accurately capture a child’s symptoms across developmental stages.

Mental Health Service History and Use

Findings revealed that many of the families who were referred to the mental health service within the CAC had previously accessed child treatment services (31.3%) and nearly half had previous child welfare involvement (41.5%), which indicates that many families referred to the service may potentially have complex histories of trauma or mental health needs. Thus, mental health services need to be connected with other community partners, such as child welfare, within the CAC model. Furthermore, mental health services within CACs would benefit from having developed relationships with other community mental health agencies where families could be referred to address additional mental health concerns that fall outside of CAS treatment mandate.

In the current study, the duration of time for trauma assessment (i.e., 0–8 months) and treatment (i.e., 0–17 months) was heterogeneous. The time needed to provide adequate assessment and treatment for trauma symptoms may vary based on the complexity of the presenting concerns, treatment engagement, barriers to attending treatment, current stressful life events, as well as the availability of administrative structures and supports within the organization (e.g., staffing). However, it is also important to consider that lengthy assessment and treatment times are costly and reduce the availability of services for a larger group of individuals. Based on the findings in the current study, it may be advantageous for trauma treatment services within CACs to develop triage systems as part of the intake processes (e.g., have fast-track cases that can be quickly triaged and assessed versus those that are more complex and may be longer). Lastly, a broad range of evidence-informed treatments were reportedly used within the mental health service, including group and parenting-based treatments. The implementation and use of treatment modalities that have strong research support by skilled clinicians and specifically address clients’ needs have the greatest potential to address and reduce trauma-related symptoms following maltreatment (Amaya-Jackson & Derosa, 2007).

Treatment Completion

Our study revealed that one-third of children who were recommended to engage in treatment did not complete the course of treatment. The following broad reasons for dropout were identified: not being interested in treatment and losing contact with the service. In this study, dropout from treatment may have been attributed to the high rates of parental mental health difficulties, inter-parental violence, and child protection involvement. To date, there is a lack of research on the barriers faced by families of children seeking and remaining in interventions for child maltreatment. The limited existing research shows that structural barriers (e.g., problems with transportation) may play a role (Sprang et al., 2013). Older children, children from low-income families, and children who have experienced multiple forms of trauma are less likely to complete trauma treatment (Chasson, Mychailyszyn, Vincent, & Harris, 2013; Eirich et al., 2020; Wamser-Nanney & Steinzor, 2017). While it is important to identify barriers to treatment dropout, it is also critical to explore potential facilitators to treatment completion. For example, Eirich et al. (2020) demonstrated that the presence of protective factors, such as increased coping skills and/or emotional support from caregivers and peers, reduced the odds of treatment dropout. Mental health services within CACs may benefit from examining how barriers to treatment completion for families could be reduced and in what ways engagement of caregivers could be bolstered (e.g., offering caregiver treatment groups, offering psychoeducation modules for caregivers) to augment the likelihood of treatment completion. Future research developing innovative methods for delivering treatments for child maltreatment that address barriers and promote facilitators of children and their families seeking and attending treatment is needed (Hanson et al., 2018).

Limitations

Findings should be interpreted while also considering the study’s limitations. First, the information collected as part of the file review was limited by what is provided in the healthcare files. For example, the referral source reported on the cumulative presenting symptoms as opposed to administering a validated questionnaire to participants. The implementation of valid and reliable questionnaires is an important future direction. This intensive form of data collection also limited our sample size and research should include a larger number of participants. Additionally, children included in our study were between the ages of 3 and 18 years of age, with only a small percentage of children under the age of five (n = 8; 4.5%). Given that maltreatment and symptom reporting are often contingent on a child’s self-report, the current study provides limited information on children under the age of five years. Future research examining developmental differences and symptom presentation, particularly for young children under the age of five years, is needed. Furthermore, there may have been information pertinent to family or abuse characteristics (e.g., ethnicity, socioeconomic status) that clinicians did not record. Only closed files were included in the current study, which may have biased against including long-term cases. Finally, the participants included in our study are representative of a large urban centre in western Canada and were specifically referred to a CAC. The sample described is not representative of children referred elsewhere for mental health treatment, including outpatient children’s mental health services, in-patient treatment services, and counseling services offered in the school system. Future research should be conducted across multiple treatment sites in Canada.

Conclusion

There is limited research on the mental health needs of children, youth, and their families referred to CACs in Canada. The nature and effectiveness of mental health services are also not well understood. Furthering the understanding of the contribution of partner agencies, particularly mental health services, has the potential to help elucidate the role CACs may play in improving children’s outcomes. Many of the children and families referred to CACs present with unique and complex mental health needs, including more than one form of maltreatment, five or more presenting concerns and a history of child welfare involvement. These needs may be most optimally addressed by specialized trauma treatment, ideally with caregiver involvement to bolster support within the child’s immediate environment. Our findings suggest that a third of children and youth did not complete the recommended mental health treatment. To further understand the barriers and facilitators to treatment engagement and completion, research and evaluation of individualized assessment and treatment approaches offered in these centres are needed.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the staff at the Child Abuse Service and Alberta Health Services for their collaboration in this project. Research support was provided to Dr. Madigan by the Alberta Children’s Hospital Foundation, the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council, and the Canada Research Chairs program. Dr. Racine was supported by a Postdoctoral Trainee Award from the Alberta Children’s Hospital Research Institute, the Cumming School of Medicine, the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council and Alberta Innovates. Funding sources had no role in publication-related decisions.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

No conflict of interest to declare.

References

- Afifi TO, MacMillan HL, Boyle M, Cheung K, Taillieu T, Turner S, Sareen J. Child abuse and physical health in adulthood. Health Reports. 2016;27(3):10–18. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26983007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afifi TO, MacMillan HL, Boyle M, Taillieu T, Cheung K, Sareen J. Child abuse and mental disorders in Canada. CMAJ. 2014;186(9):E324–332. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.131792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alink LR, Cyr C, Madigan S. The effect of maltreatment experiences on maltreating and dysfunctional parenting: A search for mechanisms. Development and Psychopathology. 2019;31(1):1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Amaya-Jackson L, Derosa RR. Treatment considerations for clinicians in applying evidence-based practice to complex presentations in child trauma. Journal of Trauma and Stress. 2007;20(4):379–390. doi: 10.1002/jts.20266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: Author; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Beal SJ, Wingrove T, Mara CA, Lutz N, Noll JG, Greiner MV. Childhood Adversity and Associated Psychosocial Function in Adolescents with Complex Trauma. Child Youth Care Forum. 2019;48(3):305–322. doi: 10.1007/s10566-018-9479-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlus A, McKenna K, Day T, Wright D. The economic costs and consequences of child abuse in Canada. 2003. Retrieved from https://cwrp.ca/sites/default/files/publications/en/Report-Economic_Cost_Child_AbuseEN.pdf.

- Departmeent of Justice, Canada. Understanding the development and impact of Child Advocacy Centres (CACs) 2018. Retrieved from http://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2018/jus/J4-81-2018-eng.pdf.

- Carlson FM, Grassley J, Reis J, Davis K. Characteristics of child sexual assault within a child advocacy center client population. Journal of Forensic Nursing. 2015;11(1):15–21. doi: 10.1097/JFN.0000000000000063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chasson GS, Mychailyszyn MP, Vincent JP, Harris GE. Evaluation of trauma characteristics as predictors of attrition from cognitive-behavioral therapy for child victims of violence. Psychology Reports. 2013;113(3):734–753. doi: 10.2466/16.02.PR0.113x30z2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Toth SL. Child maltreatment and developmental psychopathology: A multilevel perspective. In: Cicchetti D, editor. Developmental psychopathology. 3. New York, NY: WIley; 2016. pp. 457–512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JA, Mannarino AP, Deblinger E. Treating Trauma and Traumatic Grief in Children and Adolescents. New York: Guilford Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cook A, Spinazzola J, Ford J, Lanktree C, Blaustein M, Clotire M, Van der Kolk B. Complex trauma in children and adolescents. Psychiatric Annals. 2005;35(5):390–398. [Google Scholar]

- Dorsey S, Pullmann MD, Berliner L, Koschmann E, McKay M, Deblinger E. Engaging foster parents in treatment: A randomized trial of supplementing trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy with evidence-based engagement strategies. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2014;38(9):1508–1520. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubov V, Goodman D. BOOST Child & Youth Advocacy Centre: Evalution Report, October 2013–June 2015. 2017. Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Eirich R, Racine N, Garfinkel D, et al. Risk and Protective Factors for Treatment Dropout in a Child Maltreatment Population. Adversity and Resilience Science. 2020;1:165–177. doi: 10.1007/s42844-020-00011-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fallon B, Filippelli J, Lefebvre R, Joh-Carnella N, Trocme N, Black T, Stoddart J. Ontario Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect-2018. Toronto, ON: 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrara P, Corsello G, Basile MC, Nigri L, Campanozzi A, Ehrich J, Pettoello-Mantovani M. The Economic Burden of Child Maltreatment in High Income Countries. Journal of Pediatrics. 2015;167(6):1457–1459. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.09.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Turner HA, Shattuck A, Hamby SL. Violence, crime, and abuse exposure in a national sample of children and youth: An update. JAMA Pediatrics. 2013;167(7):614–621. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Turner HA, Shattuck A, Hamby SL. Prevalence of Childhood Exposure to Violence, Crime, and Abuse: Results From the National Survey of Children’s Exposure to Violence. JAMA Pediatrics. 2015;169(8):746–754. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.0676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser J, Norona C, Bartlett J, Zhang J, Spinazzola J, Griffin J, Barto B. Screening for trauma symptoms in child welfare-involved young children: Findings from a statewide truma-informed care initiative. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma. 2019;12:399–409. doi: 10.1007/s40653-018-0240-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gearing R, Mian I, Barber J, Ickowicz A. A methodology for conducting retrospective chart review research in chil and adolescent psychiatry. Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2006;15(3):126–134. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson RF, Saunders BE, Peer SO, Ralston E, Moreland AD, Schoenwald S, Chapman J. Community-Based Learning Collaboratives and Participant Reports of Interprofessional Collaboration, Barriers to, and Utilization of Child Trauma Services. Child and Youth Services Review. 2018;94:306–314. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.09.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heim C, Shugart M, Craighead WE, Nemeroff CB. Neurobiological and psychiatric consequences of child abuse and neglect. Developmental Psychobiology. 2010;52(7):671–690. doi: 10.1002/dev.20494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hruschka D, Schwartz D, St John D, Picone-Decaro E, Jenkins R, Carey J. Reiliability in coding open-ended data: Lesson learned from HIB behavioral research. Field Methods. 2004;16(3):307–331. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson SL. A USA national survey of program services provided by child advocacy centers. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2004;28(4):411–421. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leenarts LE, Diehle J, Doreleijers TA, Jansma EP, Lindauer RJ. Evidence-based treatments for children with trauma-related psychopathology as a result of childhood maltreatment: A systematic review. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2013;22(5):269–283. doi: 10.1007/s00787-012-0367-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louden C, Elliott K. Understanding the development and impact of child advocacy centres (CACs) in Canada. Victims of Crime Research Digest. 2018:11. [Google Scholar]

- MacMillan HL, Tanaka M, Duku E, Vaillancourt T, Boyle MH. Child physical and sexual abuse in a community sample of young adults: results from the Ontario Child Health Study. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2013;37(1):14–21. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madigan S, Cyr C, Eirich R, Fearon RMP, Ly A, Rash C, Alink LRA. Testing the cycle of maltreatment hypothesis: Meta-analytic evidence of the intergenerational transmission of child maltreatment. Developmental Psychopathology. 2019;31(1):23–51. doi: 10.1017/S0954579418001700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald S, Kingston D, Bayrampour H, Tough S. Adverse childhood experiences in alberta, Canada: A population based study. Medical Research Archives. 2015;(3):1–18. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald S, Scrim K, Rooney L. Building our capacity: Children’s advocacy centres in Canada. 2013. Retrieved from https://justice.gc.ca/eng/rp-pr/cj-jp/victim/rd6-rr6/rd6-rr6.pdf#page=4.

- McNeil C, Hembree-Kigin T. Parent-child interaction therapy (Vol Second Edition) New York: Springer; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Messman-Moore T, Bhuptani P. A review of the long-term impact of child maltreatment on posttraumatic stress disorder and its comorbidities: An emotion dyregulation perspective. Clinical Psychology, Science and Practice. 2017;24(2):154–169. [Google Scholar]

- Powell B, Cooper G, Hoffman K, Marvin B. The Circle of Security Intervention: Enhancing Attachment in Parent-Child Relationships. New York: The Guilford Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Racine N, Eirich R, Dimitropoulos G, Hartwick C, Madigan S. Development of trauma symptoms following adversity in childhood: The moderating role of protective factors. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2020;101:104375. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer CL, Smith TD, Ornstein AE. Child and youth advocacy centres: A change in practice that can change a lifetime. Paediatric Child Health. 2018;23(2):116–118. doi: 10.1093/pch/pxy008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprang G, Craig C, Clark J, Vergon K, Tindall M, Cohen J, Gurwitch R. Factors affecting the completion of trauma-focused treatments: what can make a difference? Traumatology. 2013;19(1):28–36. [Google Scholar]

- St-Laurent D, Dubois-Comtois K, Milot T, Cantinotti M. Intergenerational continuity/discontinuity of child maltreatment among low-income mother-child dyads: The roles of childhood maltreatment characteristics, maternal psychological functioning, and family ecology. Developmental Psychopathology. 2019;31(1):189–202. doi: 10.1017/S095457941800161X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stover CS, Berkowitz S. Assessing violence exposure and trauma symptoms in young children: a critical review of measures. Journal of Trauma and Stress. 2005;18(6):707–717. doi: 10.1002/jts.20079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toth SL, Manly JT. Developmental consequences of child abuse and neglect: Implications for intervention. Child Development Perspectives. 2019;13(1):59–64. [Google Scholar]

- Trocmé N, Fallon B, MacLaurin B, Daciuk J, Felstiner C, Black T, Cloutier R. Canadian Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect 2003. 2005 Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Vassar M, Holzmann M. The retrospective chart review: Important methodological considerations. Journal of Educational Evaluation for Health Professions. 2013;10(12):1–7. doi: 10.3352/jeehp.2013.10.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wamser-Nanney R, Scheeringa MS, Weems CF. Early Treatment Response in Children and Adolescents Receiving CBT for Trauma. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2016;41(1):128–137. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsu096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wamser-Nanney R, Steinzor CE. Factors related to attrition from trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2017;66:73–83. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]