Abstract

Historically, immediate cytoreductive nephrectomy (CN) was considered the standard of care in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC) who were fit enough to undergo surgery. Recently, 2 randomized controlled trials, SURTIME and CARMENA, have questioned the role of immediate CN and initiated an ongoing debate on the proper indications and timing of CN. Although some patients still benefit from immediate CN, other patients require immediate systemic treatment, and some of them might benefit from deferred CN in the absence of disease progression. This study provides an overview of the history of CN, an in-depth analysis of SURTIME and CARMENA, and highlights the current indications for performing immediate or deferred CN.

Keywords: Cytoreductive nephrectomy, kidney cancer, renal cell carcinoma

Introduction

Renal cell carcinoma is the sixth most common cancer in the western world with a male to female ratio of 3:2.[1] Approximately, 15% of kidney cancers are metastatic at diagnosis. The 5-year survival drops from 93% to 12% when the cancer has spread to distant parts of the body instead of being confined to the kidney.[2] For several decades, removal of the primary tumor, called cytoreductive nephrectomy (CN), was the cornerstone in newly diagnosed metastatic RCC (mRCC) treatment. Recently, 2 randomized controlled trials (RCTs), CARMENA and SURTIME, however, found no benefit of immediate CN in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC).[3,4] This study looks back at the emergence of CN and why it was popularized; we perform an in-depth analysis of both RCTs, and discuss the current place and indications for performing a CN.

History of cytoreductive nephrectomy in metastatic renal cell carcinoma

Surgical treatment of mRCC was first established in an era where effective medical therapies were yet to be discovered, and surgery served a merely palliative purpose.[5] Because of the poor susceptibility of mRCC to standard chemotherapy and conventional radiation, systemic therapy for mRCC developed greatly over the past decades.[6]

In 1992, the cytokines interleukin 2 and interferon a-2b were introduced for mRCC, but only a few patients had a survival rate exceeding 2 years. CN was popularized after several case reports noted a regression of metastatic disease following CN.[7]

The goal of CN in this “cytokine era” was threefold. First, the symptoms caused by the local tumor could be alleviated. These included local symptoms, such as pain or hematuria, and possibly distant paraneoplastic symptoms, including hypertension, hypercalcemia, and hematopoietic disturbances. Second, immunosuppressive effects could be relieved through resection of the primary tumor and reduction of the overall tumor load. This may explain the abscopal effect where distant metastases shrink after resection of the primary tumor. This may also increase the efficacy of systemic therapy. Third, CN was associated with increased survival rates in 2 RCTs that were reported in 2001 using an identical study protocol.[8] The larger study, SWOG 8949, noted a median overall survival (OS) of 11.1 months in the patient group who received combined CN and interferon a-2b versus 8.1 months in the subgroup who received interferon a-2b alone.[9] The second study, EORTC 30947, demonstrated a significant OS benefit following CN and interferon a-2b compared with interferon a-2b alone (17 vs. 7 months).[10]

Since 2005, several vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-targeted therapies (VEGFR-TT) have emerged, demonstrating superiority to the previous cytokine therapy and thereby quickly replacing them as the standard of care for systemic therapy in mRCC.[11,12] mRCC can be stratified into good, intermediate, and poor prognosis groups according to the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Centre (MSKCC or Motzer) criteria[13] and, later, the international mRCC database consortium (IMDC) criteria.[14] The IMDC criteria include 6 factors: time between diagnosis and start of systemic therapy <1 year, decreased hemoglobin, elevated leukocyte count, elevated platelet count, Karnofsky performance status <80%, and hypercalcemia. Prognosis is determined by the number of risk factors: 0 factors = good prognosis, 1–2 factors = intermediate prognosis, and 3–6 factors = poor prognosis.[14] The VEGFR-TT resulted in an increased OS from less than 1 year[11] to more than 2 years for patients with intermediate prognosis receiving plural lines of targeted therapy.[15] CN was at this point, based on the RCTs from 2001, still offered by default. The OS benefit attributed to the targeted therapy had been established in study populations where 75%–100% of the patients had received prior nephrectomy.[16] As some patients were unable to receive targeted therapy after CN owing to postoperative complications or rapid disease progression, the role and timing of CN in the targeted therapy era was questioned.

Several retrospective studies have analyzed the effect of CN in patients with mRCC. The largest analysis at the time was performed by the IMDC in 2014 and included 1,658 patients with synchronous mRCC.[17] This study demonstrated that CN provided an OS benefit in patients treated with targeted therapy, even after adjusting for prognostic factors (hazard ratio [HR] 0.60; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.52–0.69; p<0.001), and 2 conclusions were drawn. First, patients estimated to survive less than 12 months did not receive sufficient benefit from CN. Second, patients with 4 or more IMDC criteria did not derive benefit from CN. However, IMDC risk factors were not designed as preoperative risk factors, but rather as factors to classify patients at the start of systemic therapy in retrospective series where most patients had already undergone nephrectomy. This is important, for example, anemia in the Heng criteria is a marker of bone marrow invasion; whereas in a pre-surgical setting, it can be caused by hematuria. Whether this factor is prognostic pre-surgery is ill-studied. Other investigators have tried to design preoperative risk models to identify which patients benefit from CN. The most frequently used model is from the MD Anderson Cancer Center (MDACC) and includes 7 risk factors: increased serum lactate dehydrogenase, decreased albumin, symptoms caused by a metastatic site, liver metastasis, retroperitoneal adenopathy, supradiaphragmatic adenopathy, and clinical stage ≥T3. Presence of ≥4 factors is associated with poor OS following CN.[18] These results emphasize that careful patient selection is essential in determining if a patient will benefit from CN. The main limitation of these studies is their retrospective design with inherent selection bias: patients with good prognosis are usually treated with CN+VEGFR-TT, whereas patients with poor prognosis are usually treated with VEGFR-TT alone.[17] To overcome these limitations, RCTs were necessary.

Cytoreductive nephrectomy and targeted therapy: CARMENA and SURTIME

To further investigate the controversy surrounding CN in the VEGFR-TT era, 2 RCTs were initiated in 2010, namely SURTIME and CARMENA.[3,4]

The SURTIME trial was a randomized trial investigating the sequence of CN and VEGFR-TT. A comparison was made between 3 cycles of sunitinib prior to performing CN and immediate CN followed by sunitinib.[3] The objective was to investigate whether neo-adjuvant sunitinib improves outcome. The originally planned target of 458 patients was not reached; and after 5.7 years, the enrollment was closed with only 99 patients included. All patients had less than 4 MDACC risk factors.[18] Because of insufficient accrual, the primary endpoint of progression-free survival was changed to 28-week progression-free rate. It was concluded that this endpoint did not improve when patients began sunitinib therapy before planned CN (42% versus 43%, p=0.61). In the immediate CN group, 46/50 (92%) patients received CN as planned, and 40 (80%) patients received subsequent sunitinib, and 6 patients had rapid disease progression and deterioration of performance. In the deferred CN group, 48/49 (98%) patients received sunitinib and 34 (69%) patients received deferred CN. Systemic progression prior to deferred CN was a contraindication per protocol to perform CN. OS, which was a secondary endpoint, was significantly better in the intention-to-treat analysis for the deferred CN group (median OS 32.4 months) compared with the immediate CN group (15.0 months, p=0.03). Delaying systemic therapy by performing CN first may be a risk for those patients who need early control of their progressive metastatic cancer. The results in SURTIME, although exploratory, suggest that a deferred CN approach, in which CN is only offered if the disease does not progress after initial VEGFR-TT, is superior to immediate CN. Upfront sunitinib may identify patients with inherent resistance to systemic therapy who are then spared from CN and its morbidity. The most important limitation of this study was the fact that it was underpowered for its primary endpoint owing to poor accrual. This was partially because of very stringent inclusion criteria based on surgical risk factors rather than the World Health Organization performance status,[19] as is the case with the CARMENA trial. This led to the inclusion of predominantly patients with MSKCC intermediate risk in SURTIME, whereas CARMENA included a high percentage of patients with poor risk. A further limitation and difference with CARMENA is that OS was only a secondary endpoint.

The second trial, CARMENA, is a phase III non-inferiority RCT investigating the benefit of immediate CN followed by sunitinib in patients with mRCC versus sunitinib alone.[4] After a planned interim analysis at a median 50.9 months of follow-up and 326 patient deaths, OS following sunitinib only proved to be non-inferior than CN+sunitinib (median OS 18.4 versus 13.9 months, respectively). The 95% CI of the HR (0.71 to 1.10) was entirely below 1.20, which was set as the threshold for non-inferiority. These results contrast with those of previous retrospective studies that demonstrated that CN+VEGFR-TT resulted in superior OS compared with VEGFR-TT alone.[20] This can be explained by selection bias; in the retrospective series, mostly patients with good performance and patients with intermediate risk or ≤3 IMDC risk factors received CN. However, 41.4% of patients in CARMENA were patients with poor-risk IMDC.[21] CARMENA accrued slowly but did manage to enroll 450 patients over 9 years. However, only 0.7 patients were included per site per year. Patients who were good candidates for CN were unlikely to be included in this study, but were offered standard immediate CN instead, so that they would not have a 50% chance of being entered in the sunitinib-only arm and being deprived of CN. Therefore, the study population in CARMENA might not be representative for all patients with primary mRCC, and this explains the relatively high percentage of patients with poor-risk MSKCC being included.[22] Large retrospective databases have demonstrated that patients with poor risk do not benefit from CN.[17] Nevertheless, the outcome of the CARMENA trial is significant and of clinical importance.

SURTIME and CARMENA have complementing conclusions stating that immediate CN should not be performed in patients with mRCC who require systemic treatment. However, some subgroups may still benefit from immediate or deferred CN.

Current indications for cytoreductive nephrectomy

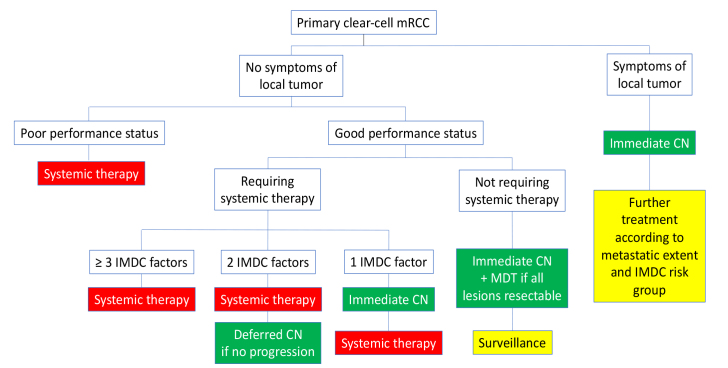

When combining data from retrospective series and the CARMENA and SURTIME trials, it is clear that there is still a place for CN in mRCC treatment. Treatment plans should be discussed at multidisciplinary tumor boards on the basis of a patient’s performance status, symptoms, metastatic load, IMDC risk group, and risk of surgical complications.[23]

In patients with symptoms (for example, hematuria, pain, a large tumor thrombus, uncontrolled hypertension, or paraneoplastic symptoms), CN is still recommended for symptom relief. We also know from retrospective data that patients with >3 IMDC risk factors do not benefit from CN.[17] Similarly, CARMENA sub-analyses showed that patients with only 1 IMDC risk factor (interval between diagnosis and treatment <1 year) who were randomized to CN+sunitinib did no significantly better than patients who were randomized to sunitinib alone (median OS 30.5 versus 25.2 months, p=0.232).[21] This subgroup of patients was highly underrepresented in CARMENA to detect statistical significance. This indicates that there is a subpopulation of patients with few IMDC risk factors who may benefit from CN. Patients with 2 IMDC risk factors, however, had significantly poor OS following CN+sunitinib compared with sunitinib alone (median OS 16.6 versus 31.2 months, HR 0.61, p=0.015).[21] Interestingly, this survival difference is almost identical to SURTIME (median OS 15.0 versus 32.4 months), which had a similar inclusion with the majority being patients with intermediate-risk MSKCC with 2 risk factors.[3] Unfortunately, we do not know how many patients in this subgroup of CARMENA underwent a deferred nephrectomy.

In addition, some patients may benefit from deferred CN after initial systemic therapy. A total of 40 (18%) patients in the sunitinib only arm of CARMENA underwent a nephrectomy after a median of 11 months, 33 of them owing to near complete response at metastatic sites. Sub-analysis of this group demonstrated a better median OS of 48.5 months compared with 15.7 months (p<0.01),[21] and overall, 31.4% of the patients with secondary nephrectomy restarted sunitinib. Patients in the deferred CN arm of SURTIME, where 69% did not progress on sunitinib and received deferred CN, demonstrated superior OS (median 32.4 months) than patients receiving immediate CN.[3] Similarly, Bhindi et al. [24] retrospectively analyzed 1,541 patients from the IMDC cohort treated between 2006 and 2018, of which 85 (5.5%) received sunitinib followed by deferred CN. Indications for performing CN were unknown. Median OS in this group was 46 months, compared with 10 and 19 months for patients receiving sunitinib alone and CN followed by sunitinib, respectively (p<0.001). Therefore, patients starting sunitinib and demonstrating response or stable disease could possibly benefit from deferred CN. Response to sunitinib could be used as a “litmus test” to select patients in whom to perform CN and perhaps give them the possibility to stop sunitinib. However, patients who progress early on sunitinib might harbor more aggressive biology and are destined to do poorly. These patients may not benefit from CN.

Furthermore, patients with only limited metastatic burden (oligometastatic) were poorly represented in the CARMENA cohort.[4] Patients with 1–3 metastases demonstrate superior OS following CN than patients with >3 metastases.[25] Moreover, patients in whom all metastatic lesions were treated with metastasis-directed therapy (MDT) (either surgery or radiotherapy) demonstrated better progression-free OS than patients who had incomplete metastatic treatment.[26] Most of these patients do not require systemic therapy, and immediate CN, along with MDT, if complete control could be achieved, should be preferred.

In all other patients, namely those presenting with mRCC with multiple metastatic sites that cannot be fully controlled by MDT, who have 2 or more IMDC risk factors and no local tumor-related symptoms, or who have poor performance status, systemic therapy should be started according to current guidelines (VEGFR-TT, immuno-oncological therapy [IO], or a combination). In case of partial or near to complete response at the metastatic sites, deferred CN may be offered. A simplified flowchart of this is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Proposed flowchart for treatment of clear-cell metastatic renal cell carcinoma based on International mRCC Database Consortium risk factors

Future perspectives

Several clinical questions still remain regarding the efficacy of CN. We still have no randomized controlled data on the effectiveness of CN in patients with limited disease. However, given the good long-term outcomes following CN in retrospective series[17,25] and the poor recruitment of such patients in CARMENA,[4] it is unlikely that this issue will be addressed in an RCT.

Despite CARMENA and SURTIME providing new insights into the VEGFR-TT era, we have now entered the IO era and guidelines propose IO or a combination of IO and a tyrosine kinase inhibitor as the first-line treatment of mRCC.[27] We do not know if the conclusions concerning CN presented above still apply in the IO era. Observational data from a cohort of 437 patients with mRCC from the IMDC consortium still show an OS benefit for patients treated with CN+IO than with IO alone (median 53.6 months versus 21.4 months, p<0.0001).[28] However, a retrospective series on CN had an inherent selection bias as only a subset of patients were referred for CN. Therefore, several RCTs are underway to elucidate the role of deferred CN in the IO era. NORDIC SUN (NCT03977571) will accrue 400 patients with intermediate and poor-risk mRCC who will be treated with 4 cycles of nivolumab-ipilimumab. Patients who have ≤3 IMDC risk factors and are deemed eligible for CN will be randomized 1:1 to either maintenance nivolumab or deferred CN followed by maintenance nivolumab. The South-Western Oncology Group is currently developing the PROBE trial (NCT04510597) that will have a similar setup with IO-based regimens and 1:1 randomization to deferred CN and continued IO or IO only in patients who have stable disease or response to IO.

Most literature focuses on clear-cell mRCC. We do not know if our treatment regimens are also applicable for non-clear-cell mRCC, and trials in these subgroups are necessary.

The outcome of patients with mRCC is very heterogeneous. Therefore, risk stratification models can be used, such as the MDACC or IMDC models, which are based on clinical parameters.[14] The IMDC model was constructed at the beginning of the VEGFR-TT era. We do not know if it is still applicable in the IO era, although differential outcome in the Checkmate 214 trial between patients with good prognosis (no benefit in OS) and those with intermediate and poor risk (significant benefit in OS with nivolumab-ipilimumab compared with sunitinib) is encouraging that the IMDC risk grouping is still valuable.[29] A recent retrospective series compared 10 clinical risk models (including MDACC and IMDC) for patients undergoing CN from 2005 to 2017 and found that no model performed well enough to discriminate OS.[30] Good contemporary risk stratification models are needed for patients undergoing upfront or deferred CN in the VEGFR-TT and IO era. Genomic and molecular biomarkers are of interest because they may not only be prognostic but also predictive of treatment response. For instance, several studies have already shown PD-L1 expression to be associated with better outcome in patients with mRCC treated with IO.[31] A genomic or molecular profile might also predict who may benefit from CN.[32]

Conclusion

The CARMENA and SURTIME trials caused a paradigm shift in mRCC treatment as upfront CN is no longer recommended in patients who require systemic therapy and have >1 IMDC risk factor. However, there is still a role for upfront CN in symptomatic patients, in patients with oligometastasis who do not require immediate systemic therapy or in whom complete resection of all metastatic sites is possible, or those with only 1 IMDC risk factor. In patients responding to systemic therapy, deferred CN might also improve survival and offer the possibility to stop systemic treatment. Further trials are ongoing to elucidate the role of deferred CN in the current IO era.

Main Points

Cytoreductive nephrectomy (CN) is no longer the standard of care for all patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma, but some subgroups may benefit.

Symptomatic patients can be offered CN for symptom relief.

Patients who do not require systemic therapy with few metastases can be offered CN and metastasis-directed therapy to all metastatic sites if possible.

Patients starting systemic therapy can be considered for deferred CN in case of partial or near complete response.

Better clinical, genetic, or molecular risk stratification is needed to identify optimal candidates and timing for CN.

Footnotes

Peer-review: This manuscript was prepared by the invitation of the Editorial Board and its scientific evaluation was carried out by the Editorial Board.

Author Contributions: Concept – C.V.P., C.S., K.D.; Design – C.V.P., C.S., K.D.; Supervision – K.D.; Materials – C.V.P., C.S.; Data Collection and/or Processing – C.V.P., C.S.; Analysis and/or Interpretation – C.V.P., C.S., N.V., S.R., V.F., I.A., M.A., G.D.M., A.B., K.D.; Literature Search – C.V.P., C.S.; Writing Manuscript – C.V.P., C.S., K.D.; Critical Review – C.V.P., C.S., N.V., S.R., V.F., I.A., M.A., G.D.M., A.B., K.D.

Conflict of Interest: C.V.P. participated in ad boards from Astellas. A.B. participated in ad boards from Ipsen, Novartis and BMS. K.D. is a consultant for Intuitive Surgical.

Financial Disclosure: The authors declared that this study has received no financial support.

References

- 1.Thorstenson A, Bergman M, Scherman-Plogell AH, Hosseinnia S, Ljungberg B, Adolfsson J, et al. Tumour characteristics and surgical treatment of renal cell carcinoma in Sweden 2005–2010: a population-based study from the national Swedish kidney cancer register. Scand J Urol. 2014;48:231–8. doi: 10.3109/21681805.2013.864698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020. Cancer J Clin. 2020;70:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bex A, Mulders P, Jewett M, Wagstaff J, van Thienen JV, Blank CU, et al. Comparison of Immediate vs Deferred Cytoreductive Nephrectomy in Patients With Synchronous Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Receiving Sunitinib: The SURTIME Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5:164–70. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.5543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mejean A, Ravaud A, Thezenas S, Colas S, Beauval JB, Bensalah K, et al. Sunitinib Alone or after Nephrectomy in Metastatic Renal-Cell Carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:417–27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1803675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dekernion JB, Ramming KP, Smith RB. The natural history of metastatic renal cell carcinoma: a computer analysis. J Urol. 1978;120:148–52. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(17)57082-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Psutka SP, Kim SP, Gross CP, Van Houten H, Thompson RH, Abouassaly R, et al. The impact of targeted therapy on management of metastatic renal cell carcinoma: trends in systemic therapy and cytoreductive nephrectomy utilization. Urology. 2015;85:442–50. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2014.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marcus SG, Choyke PL, Reiter R, Jaffe GS, Alexander RB, Linehan WM, et al. Regression of metastatic renal cell carcinoma after cytoreductive nephrectomy. J Urol. 1993;150:463–6. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(17)35514-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flanigan RC, Mickisch G, Sylvester R, Tangen C, Van Poppel H, Crawford ED. Cytoreductive nephrectomy in patients with metastatic renal cancer: a combined analysis. J Urol. 2004;171:1071–6. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000110610.61545.ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flanigan RC, Salmon SE, Blumenstein BA, Bearman SI, Roy V, McGrath PC, et al. Nephrectomy followed by interferon alfa-2b compared with interferon alfa-2b alone for metastatic renal-cell cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1655–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa003013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mickisch GH, Garin A, van Poppel H, de Prijck L, Sylvester R, et al. European Organisation for R. Radical nephrectomy plus interferon-alfa-based immunotherapy compared with interferon alfa alone in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2001;358:966–70. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06103-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Tomczak P, Michaelson MD, Bukowski RM, Rixe O, et al. Sunitinib versus interferon alfa in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:115–24. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coppin C, Le L, Porzsolt F, Wilt T. Targeted therapy for advanced renal cell carcinoma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008:CD006017. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006017.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Motzer RJ, Mazumdar M, Bacik J, Berg W, Amsterdam A, Ferrara J. Survival and prognostic stratification of 670 patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2530–40. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.8.2530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heng DY, Xie W, Regan MM, Warren MA, Golshayan AR, Sahi C, et al. Prognostic factors for overall survival in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with vascular endothelial growth factor-targeted agents: results from a large, multicenter study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5794–9. doi: 10.1200/jco.2009.27.15_suppl.5041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Motzer RJ, Barrios CH, Kim TM, Falcon S, Cosgriff T, Harker WG, et al. Phase II randomized trial comparing sequential first-line everolimus and second-line sunitinib versus first-line sunitinib and second-line everolimus in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:2765–72. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.6911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bhindi B, Abel EJ, Albiges L, Bensalah K, Boorjian SA, Daneshmand S, et al. Systematic Review of the Role of Cytoreductive Nephrectomy in the Targeted Therapy Era and Beyond: An Individualized Approach to Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma. Eur Urol. 2019;75:111–28. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2018.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heng DY, Wells JC, Rini BI, Beuselinck B, Lee JL, Knox JJ, et al. Cytoreductive nephrectomy in patients with synchronous metastases from renal cell carcinoma: results from the International Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Database Consortium. Eur Urol. 2014;66:704–10. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Culp SH, Tannir NM, Abel EJ, Margulis V, Tamboli P, Matin SF, et al. Can we better select patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma for cytoreductive nephrectomy? Cancer. 2010;116:3378–88. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuusk T, Szabados B, Liu WK, Powles T, Bex A. Cytoreductive nephrectomy in the current treatment algorithm. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2019;11 doi: 10.1177/1758835919879026. 1758835919879026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bhindi B, Habermann EB, Mason RJ, Costello BA, Pagliaro LC, Thompson RH, et al. Comparative Survival following Initial Cytoreductive Nephrectomy versus Initial Targeted Therapy for Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma. J Urol. 2018;200:528–34. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2018.03.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mejean A, Thezenas S, Chevreau C, Bensalah K, Geoffrois L, Thiery-Vuillemin A, et al. Cytoreductive nephrectomy (CN) in metastatic renal cancer (mRCC): Update on Carmena trial with focus on intermediate IMDC-risk population. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37:4508. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2019.37.15_suppl.4508. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arora S, Sood A, Dalela D, Tang HJ, Patel A, Keeley J, et al. Cytoreductive Nephrectomy: Assessing the Generalizability of the CARMENA Trial to Real-world National Cancer Data Base Cases. Eur Urol. 2019;75:352–3. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2018.10.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roussel E, Campi R, Larcher A, Verbiest A, Antonelli A, Palumbo C, et al. Rates and Predictors of Perioperative Complications in Cytoreductive Nephrectomy: Analysis of the Registry for Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma. Eur Urol Oncol. 2020;3:523–9. doi: 10.1016/j.euo.2020.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bhindi B, Graham J, Wells JC, Bakouny Z, Donskov F, Fraccon A, et al. Deferred Cytoreductive Nephrectomy in Patients with Newly Diagnosed Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma. Eur Urol. 2020;78:615–23. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2020.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roussel E, Verbiest A, Milenkovic U, Van Cleynenbreugel B, Van Poppel H, Joniau S, et al. Too good for CARMENA: criteria associated with long systemic therapy free intervals post cytoreductive nephrectomy for metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Scand J Urol. 2020:1–7. doi: 10.1080/21681805.2020.1814858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ishihara H, Takagi T, Kondo T, Fukuda H, Tachibana H, Yoshida K, et al. Prognostic impact of metastasectomy in renal cell carcinoma in the postcytokine therapy era. 2021;39:77.e17–77.e25. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2020.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ljungberg B, Albiges L, Abu-Ghanem Y, Bensalah K, Dabestani S, Fernandez-Pello S, et al. European Association of Urology Guidelines on Renal Cell Carcinoma: The 2019 Update. Eur Urol. 2019;75:799–810. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2019.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bakouny Z, Xie W, Dudani S, Wells C, Loo Gan C, Donskov F, et al. Cytoreductive nephrectomy (CN) for metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC) treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) or targeted therapy (TT): A propensity score-based analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:608. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2020.38.6_suppl.608. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Motzer RJ, Rini BI, McDermott DF, Aren Frontera O, Hammers HJ, Carducci MA, et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus sunitinib in first-line treatment for advanced renal cell carcinoma: extended follow-up of efficacy and safety results from a randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20:1370–85. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30413-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Westerman ME, Shapiro DD, Tannir NM, Campbell MT, Matin SF, Karam JA, et al. Survival following cytoreductive nephrectomy: a comparison of existing prognostic models. BJU Int. 2020;126:745–53. doi: 10.1111/bju.15160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mori K, Abufaraj M, Mostafaei H, Quhal F, Fajkovic H, Remzi M, et al. The Predictive Value of Programmed Death Ligand 1 in Patients with Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Treated with Immune-checkpoint Inhibitors: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Eur Urol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2020.10.006. S0302.2838(20)30783-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Turajlic S, Xu H, Litchfield K, Rowan A, Chambers T, Lopez JI, et al. Tracking Cancer Evolution Reveals Constrained Routes to Metastases: TRACERx Renal. Cell. 2018;173:581–94.e12. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.03.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]