Abstract

Knowledge about prevalence and etiology of running-related injuries (RRIs) is important to design effective RRI prevention programs. Mental aspects and sleep quality seem to be important potential risk factors, yet their association with RRIs needs to be elucidated. The aims of this study are to investigate the epidemiology of RRIs in recreational runners and the association of mental aspects, sleep, and other potential factors with RRIs. An internet-based questionnaire was sent to recreational runners recruited through social media, asking for personal and training characteristics, mental aspects (obsessive passion, motivation to exercise), sleep quality, perceived health, quality of life, foot arch type, and RRIs over the past six months. Data were analyzed descriptively and using logistic regression. Self-reported data from 804 questionnaires were analyzed. Twenty-five potential risk factors for RRIs were investigated. 54% of runners reported at least one RRI. The knee was the most-affected location (45%), followed by the lower leg (19%). Patellofemoral pain syndrome was the most-reported injury (20%), followed by medial tibial stress syndrome (17%). Obsessive passionate attitude (odds ratio (OR):1.35; 95% confidence interval (CI):1.18-1.54), motivation to exercise (OR:1.09; CI:1.03-1.15), and sleep quality (OR:1.23; CI:1.15-1.31) were associated with RRIs, as were perceived health (OR:0.96; CI:0.94-0.97), running over 20 km/week (OR:1.58; CI:1.04-2.42), overweight (OR:2.17; CI:1.41-3.34), pes planus (OR:1.80; CI:1.12-2.88), hard-surface running (OR:1.37; CI:1.17-1.59), running company (OR:1.65; CI:1.16-2.35), and following a training program (OR:1.51; CI:1.09-2.10). These factors together explained 30% of the variance in RRIs. A separate regression analysis showed that mental aspects and sleep quality explain 15% of the variance in RRIs. The association of mental aspects and sleep quality with RRIs adds new insights into the multifactorial etiology of RRIs. We therefore recommend that besides common risk factors for RRI, mental aspects and sleep be incorporated into the advice on prevention and management of RRIs.

Key points.

54% of runners reported at least one RRI.PFPS (20%) and MTSS (17%) were the most-reported injuries.

The knee (45%) and lower leg/Achilles (26%) were the most-reported injury locations.

More obsessive passionate attitude and poor sleep quality were associated with most of RRIs.

Lower perceived health and pes planus or cavus were also associated with most of RRIs.

Key words: Running, injury, etiology, epidemiology, injury prevention, rehabilitation

Introduction

Running has become the most popular form of physical activity (Rothschild, 2012). Due to its affordability and convenience, needing less equipment than many other sports, the number of runners has increased in recent decades (Lopes et al., 2012). Recreational runners comprise the largest group of runners worldwide (Hespanhol et al., 2013). Running has many benefits, such as improvement of mental and physical health: a study reported a 45% lower risk of cardiovascular mortality in runners compared to non-runners (Lee et al., 2014). Running-related injuries (RRIs) are the major drawback of running. Incidence rates from 19% to 79% were reported for RRIs, depending on the definition used and the population studied (Van Gent et al., 2007). RRIs may cause individuals to quit sports and/or physical activities temporarily or even permanently. RRIs can additionally result in high treatment costs and costs related to work absenteeism, which can lead to discontinuing running (Fokkema et al., 2019).

To develop preventive measures for RRIs, more knowledge about etiological factors is needed. According to the Translating Research into Injury Prevention Practice framework (TRIPP) (Finch, 2006), upon injury surveillance the second stage is establishing the etiology of injury. Accordingly, identifying and understanding risk factors for RRIs as well as the most commonly affected anatomical locations are important steps toward developing an effective prevention program (van Mechelen et al., 1992). There is evidence that the etiology of RRI is multifactorial and includes both extrinsic and intrinsic risk factors (Gijon-Nogueron and Fernandez-Villarejo, 2015; Mousavi, 2020). Several studies have reported risk factors predisposing runners to injuries (Ceyssens et al., 2019; Gijon-Nogueron and Fernandez-Villarejo, 2015; Mousavi, 2020; Mousavi et al., 2019; Van Der Worp et al., 2015), including abnormal biomechanics, previous injuries, training-related risk factors, and insufficient running experience. However, there is still no consensus on the exact etiology of RRIs and not all potential risk factors for RRIs have been explored.

Besides running/training and personal factors, RRIs may also be impacted by mental aspects, sleep, and lifestyle factors. These factors have not been explored extensively in runners yet, and not enough information on their effects on RRIs (and vice versa) is available. Recent reviews emphasize the role of mental aspects as an etiological factor for sports-related injuries (Ivarsson et al., 2017; Johnson and Ivarsson, 2017). Alterations in mental variables can predict sports injury incidence (Ivarsson et al., 2017; Johnson and Ivarsson, 2017). Mental attitudes such as passion have received increased attention in sports studies because of their potential effect on sports-related injuries (Akehurst and Oliver, 2014; Lichtenstein and Jensen, 2016). Passion is defined as a strong motivation toward an activity that people like (Vallerand et al., 2003). Obsessive passion is an aspect of passion characterized by internal pressures that make the person feel compelled to engage in the activity (Vallerand et al., 2003). Individuals with obsessive passion keep doing their activity regardless of their ability, loading capacity and sufficient recovery. Runners with obsessive passion may neglect little pains and keep on training with minor injuries, leading to more severe and difficult-to-treat gradual-onset (overuse) injuries (Vallerand et al., 2003). An obsessive passionate attitude is reported to be positively associated with sports-related injuries (Akehurst and Oliver, 2014; Rip et al., 2006; Stephan et al., 2009; Vallerand et al., 2003). The association between obsessive passionate attitude and RRIs has not been investigated extensively.

Good sleep quality is vital for the process of musculoskeletal recovery and concentration, which are important elements toward better performance of an activity such as running. By contrast, poor sleep quality is known to disrupt musculoskeletal recovery and reaction times plus influence mood and cognitive functions, increasing injury risk (Durmer and Dinges, 2005; Milewski et al., 2014). Several studies report that lack of sleep is associated with a higher risk of sustaining sports-related injuries (Gao et al., 2019; Luke et al., 2011; Milewski et al., 2014; von Rosen et al., 2017); no studies have examined this association with RRIs though.

Altogether, increasing knowledge about prevalence of and factors associated with RRIs could be helpful to tailor more effective preventive and treatment programs. The likely association of mental aspects and sleep quality with RRIs increases the insight into the importance of these factors in occurrence of RRIs. The aims of the current study are therefore to investigate the prevalence of RRIs in recreational runners and the association of mental aspects, sleep, and other potential factors such as personal characteristics and training-related factors with RRIs. We hypothesized that mental aspects and sleep quality are associated with RRIs. Specifically, higher obsessive passion for running and motivation to run and poor sleep quality are associated with a higher reporting of RRIs.

Methods

Study design

The present study is a cross-sectional survey investigating the prevalence of RRIs and risk factors associated with RRIs in recreational runners using an electronic/web-based questionnaire. Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the University Institutional Ethics Review Board (IR.SSRI. 1398.154).

Participants

Recreational runners were invited by flyers, posters, through social media, university sports and health departments, running clubs, gyms, and sports shops in the Iranian cities of Tehran, Mashhad, and Shiraz. A recreational runner was defined as someone who has been running for at least 9 months prior to completing the questionnaire for a minimum of 5 km/week and has not been classified as an elite runner by the track and field federation. The sample was selected by convenience.

Data collection

A specific questionnaire in Farsi, based on the “Start to Run” study questionnaire (Smits et al., 2016), was developed using Google Form. An electronic link to the online questionnaire was provided.

The link was sent to runners using internet communication tools (WhatsApp, Telegram, Instagram). Upon clicking on the electronic link, runners were directed to a page containing the recreational runner eligibility criteria defined above, instructions for completing the questionnaire, and a consent form. In this section runners were also asked to consult their physicians or physiotherapists about their foot arch type (normal, pes planus or pes cavus), and possible RRIs that occurred over the past six months. An RRI was defined as “Running-related (training or competition) musculoskeletal pain in the lower limbs that causes a restriction on or stoppage of running (distance, speed, duration, or training) for at least 7 days or 3 consecutive scheduled training sessions, or that requires the runner to consult a physician or other health professional” (Yamato et al., 2015).

Upon completing and confirming the first section, the runner was able to proceed with the questionnaire. The questionnaire asked for personal characteristics (age, weight, height, educational status), running profiles (including running experience, weekly running distance, speed, weekly frequency, running surface, running shoes, foot strike type, warm-up, cool-down, running training program, running in a group), foot arch type, history of RRIs over the past six months (injuries included patellofemoral pain syndrome (PFPS), medial tibial stress syndrome (MTSS), Achilles tendinopathy (AT), patellar tendinopathy (PT), iliotibial band syndrome (ITBS), plantar fasciitis (PF), strain, sprain, meniscal or cartilage injury, others), and injury location. The definition of RRI was explained and runners were asked to state whether they had any RRIs over the past six months based on the RRI definition. If they answered yes, they were asked to specify the type of RRI (based on their consultation with their physician or physiotherapist). To determine injury location, a manikin chart divided into 8 major locations and 22 sub-locations was designed. Runners were asked to consult their physician or physiotherapist about their foot arch type. In addition, an instruction for evaluating foot arch directed to an online link was provided. The online questionnaire also included the following instruments.

Obsessive passion for running

Obsessive passion for running was measured using the passion scale developed by Vallerand et al. (2003). The validity and reliability of this questionnaire in Farsi have been proven (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.86) (Jafari et al., 2018). The obsessive passion scale consists of six items (e.g. “I have almost an obsessive feeling for running” and “If I could, I would only run”). This scale was scored on a 7-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (not agree at all) to 7 (very strongly agree). The total score was calculated as the mean of the six item scores where 1 indicates low obsessive passion and 6 indicates high obsessive passion.

Motivation to exercise

Motivation to exercise was measured using the Behavioral Regulation in Exercise Questionnaire-2 (BREQ-2), (Markland and Tobin, 2004). BREQ-2 consists of 19 items (e.g. “I feel guilty when I don’t exercise” and “It’s important to me to exercise regularly”) assessing five subscales that include 1) motivation, 2) external regulation, 3) introjected regulation, 4) identified regulation, and 5) intrinsic regulation. Using the scores on the five subscales, the relative autonomy index (RAI) was calculated with a higher RAI score showing a higher level of intrinsic motivation. Farmanbar et al. (2011) reported acceptable validity and reliability (Cronbach’s alpha > 0.70) for the Iranian version of BREQ-2 (Farmanbar et al., 2011).

Sleep quality

Sleep quality was measured using the “Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index” (PSQI), a valid and reliable questionnaire (Buysse et al., 1989). The PSQI consists of 19 items (e.g. “During the past month, how often have you had trouble sleeping because you wake up in the middle of the night or early morning?”). These items assess seven components of sleep: (1) sleep quality, (2) sleep duration, (3) sleep latency, (4) sleep efficiency, (5) sleep disturbances, (6) use of sleep medication, and (7) daytime dysfunction. The PSQI provides a composite score of sleep quality and quantity ranging from 0 to 21, with higher scores indicating poor sleep quality. Farrahi et al. (2012) reported acceptable validity and reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.78) for the Iranian version of PSQI (Farrahi et al., 2012).

Perceived health

Perceived health was measured using the RAND 36-items (Hays et al., 1993). The RAND 36-Item includes eight concepts: physical functioning, bodily pain, role limitations due to physical health problems, role limitations due to personal or emotional problems, emotional well-being, social functioning, energy/fatigue, and general health perceptions. It also includes a single item that provides an indication of perceived change in health. Scoring the RAND 36-Item was performed using the instruction introduced by Hey et al. study. A high score defines a more favorable health state. Montazeri et al. (2005) reported acceptable validity and reliability (Cronbach’s alpha coefficients ranging from 0.77 to 0.90) for the Iranian version of RAND 36-item (Montazeri et al., 2005).

Physical activity in daily life

Physical activity in daily life was measured using the Short Questionnaire to Assess Health-enhancing Physical Activity (SQUASH) (Wendel-Vos et al., 2003). The SQUASH includes 4 domains: 1) community activities, 2) activity at work and school, 3) household activities, and 4) leisure time activities. Scoring the questionnaire was based on the instruction presented by Wendel-Vos et al. (2003) study. The higher the score, the higher severity of physical activity. Abdi et al. (2016) reported accaptable validity and reliability for the Iranian version of SQUASH (Abdi et al., 2016).

Data analysis

Data were analyzed with SPSS IBM version 26. Quantitative variables were reported as mean and standard deviation, categorical variables as frequency and percentages. No quantitative variables were distributed normally. Mann-Whitney and Chi-square tests were used to compare data between runners with and without a history of RRIs. In order to avoid errors by repeated significance testing, the significance level was divided by the number of performed tests (Bonferroni correction). A univariate logistic regression analysis was used to assess a likely association between each variable and having an RRI. Those variables with a p < 0.20 were included in the multivariable logistic regression model (Hespanhol et al., 2013) with backward elimination, whereby variables remained in the model if their associated multivariable p-value was <0.05. Only modifiable factors were entered into multivariable logistic regression, therefore sex and age were not entered into logistic models. To establish the assumption of no multicollinearity among the independent variables and enhance model fitting, multicollinearity was tested by examining the variance inflation factor (VIF). The maximum VIF in the regression analysis was 1.3, indicating the absence of multicollinearity effects (VIF > 3 indicates a multicollinearity issue) (O’Brien, 2007). We reported the results as odds ratios (OR) and 95%CI (confidence interval). The OR in categorical variables represents the change in odds of injury relative to the referenced category. The OR in continuous variables represents the change in odds of injury for a one-unit increase. Age, obsessive passion, BREQ-2, sleep quality, RAND 36-items, and SQUASH are continuous variables.

Results

Runners responses and characteristics

The questionnaire was completed by 826 runners, 22 of them excluded due to incorrect data (such as not meeting the eligibility criteria). Total data from 804 questionnaires were analyzed: 644 from Tehran city, 102 from Mashhad, and 58 from Shiraz city.

Table 1 shows the description of runners’ characteristics divided into two groups, with/without injury history. Male runners comprise 57% (462) of runners. Runners who reported an injury had significantly higher obsessive passion for running, higher score on sleep quality (indicating poorer sleep quality) and lower perceived health (p < 0.001). 80% of runners had <5 years’ running experience; 59% and 69% had a running duration of up to 60 min/session and up to 3 sessions/week, respectively; 80% of runners reported a BMI in the healthy range (18 < BMI < 25); 80% reported participation in other sports. Most runners reported doing warm-up (92%) and cool-down (84%) exercises.

Table 1.

Runners’ characteristics (comparing characteristics between runners with injury history and those without injury history)

| Variable | Total runners (n=804) |

Runners with injury history (n=432) |

Runners without injury history (n=372) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex Female, n (%) | 342 (42.5) | 176 (40.7) | 166 (44.6) | |

| Male, n (%) | 462 (57.5) | 256 (59.3) | 206 (55.4) | |

| Total, n (%) | 804 | 432(54) | 372(46) | |

| Age (years) | 27(11) | 27(12) | 27(12) | 0.48 |

| Obsessive passion | 3.0 (1.3) | 3.2 (1.4) | 2.7 (1.2) | <0.001 |

| BREQ-2 | 10.5 (3.1) | 10.7 (2.8) | 10.3 (3.4) | 0.594 |

| Sleep quality | 5.9 (2.8) | 6.6 (2.8) | 5.1 (2.5) | <0.001 |

| RAND 36-items | 77.0 (11.9) | 74.9 (12.5) | 79.6 (10.6) | <0.001 |

| SQUASH | 6418.9 (5421.3) | 6278.8 (5227.4) | 6582.7 (5640.8) | 0.751 |

| Running distance (km/week) | 15(15) | 15(20) | 15(10) | 0.04 |

| Up to 10, n (%) | 298 (37.1) | 148 (34.3) | 150 (40.3) | 0.002 |

| Between 10 & 20, n (%) | 266 (33.1) | 132 (30.6) | 134 (36.0) | |

| Over 20, n (%) | 240 (29.9) | 152 (35.) | 88 (23.7) | |

| Running experience (years) | 2(4) | 2(4) | 2 (3.2) | 0.49 |

| Up to 2, n (%) | 452 (56.2) | 244 (56.5) | 208 (55.9) | 0.109 |

| Between 2 & 5, n (%) | 198 (24.6) | 96 (22.2) | 102 (27.4) | |

| Over 5, n (%) | 154 (19.2) | 92 (21.3) | 62 (16.7) | |

| Running sessions (No/week) | 3(2) | 3(2) | 3(2) | 0.146 |

| Up to 3, n (%) | 558 (69.4) | 304 (70.4) | 254 (68.3) | 0.52 |

| Over 3, n (%) | 246 (30.6) | 128 (29.6) | 118 (31.7) | |

| Running duration (min/session) | 45(30) | 45(30) | 40(30) | <0.001 |

| Up to 60, n (%) | 476 (59.2) | 235 (54.4) | 241 (64.8) | 0.003 |

| Over 60, n (%) | 358(40.8) | 197 (45.6) | 131 (35.2) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23 (3.6) | 23 (3.9) | 23 (3.4) | 0.8 |

| Normal, n (%) | 644 (80.1) | 336 (77.8) | 308 (82.8) | 0.087 |

| Overweight, n (%) | 150 (18.7) | 92 (21.3) | 58 (15.6) | |

| Obese, n (%) | 10 (1.2) | 4 (0.9) | 6 (1.6) | |

| Foot type | 62 (7.7%) reported “do not know” | |||

| Normal, n (%) | 564 (70.1) | 282 (65.3) | 282 (75.8) | <0.001 |

| Pes planus, n (%) | 131 (16.3) | 89 (20.6) | 42 (11.3) | |

| Pes cavus, n (%) | 47 (5.8) | 35 (8.1) | 12 (3.2) | |

| Running surface # Hard | 1.60 (1.13) | 1.83 (1.08) | 1.34 (1.14) | <0.001 |

| Soft | 0.29 (0.71) | 0.28 (0.67) | 0.31 (0.76) | 0.92 |

| Treadmill | 0.67 (0.94) | 0.61 (0.79) | 0.73 (1.08) | 0.10 |

| Others | 0.18 (0.61) | 0.21 (0.69) | 0.15 (0.51) | 0.43 |

| Running company Group, n (%) | 252 (31.3) | 146 (33.8) | 106 (28.5) | 0.11 |

| Alone, n (%) | 552 (68.7) | 286 (66.2) | 266 (71.5) | |

| Following a running program No, n (%) | 424 (52.7) | 213 (49.3) | 211 (56.7) | 0.036 |

| Yes, n (%) | 380 (47.3) | 219 (50.7) | 161 (43.3) | |

| Other sports Yes, n (%) | 642 (79.9) | 358 (82.9) | 284 (76.3) | 0.021 |

| No, n (%) | 162 (20.1) | 74 (17.1) | 88 (23.7) | |

| Special shoes No, n (%) | 248 (30.8) | 124 (33.3) | 124 (28.7) | 0.21 |

| Yes, n (%) | 556 (69.2) | 248 (66.7) | 308 (71.3) | |

| Special insole No, n (%) | 687 (85.4) | 359 (83.1) | 328 (88.2) | 0.042 |

| Yes, n (%) | 117 (14.6) | 73 (16.9) | 44 (11.8) | |

| Warm up Yes, n (%) | 740(92) | 392 (90.7) | 348 (93.5) | 0.143 |

| No, n (%) | 64(8) | 40 (9.3) | 24 (6.5) | |

| Cool down Yes, n (%) | 672 (83.6) | 362 (83.8) | 310 (83.3) | 0.86 |

| No, n (%) | 132 (16.4) | 70 (16.2) | 62 (16.7) | |

| Foot strike Rearfoot, n (%) | 432 (53.7) | 224 (51.9) | 208 (55.9) | 0.205 |

| Midfoot, n (%) | 192 (23.9) | 116 (26.9) | 76 (20.4) | |

| Forefoot, n (%) | 148 (18.4) | 76 (17.6) | 72 (19.4) | |

Continuous data are expressed as mean and standard deviation (tested by the Mann-Whitney test). All categorical data are expressed by number of runners and percentages (using Chi-square test). Type of surface: hard (cement, asphalt), treadmill, soft (gravel, grass, off-road track), and other (synthetic, sand). Bold p-value shows the statistically significant difference between those with and without injury history [p < 0.002 0.05/30 (the number of comparisons)].

Running injuries and location

Of the 804 runners, 432 (54%) reported at least one RRI over the last six months; 74 (17%) reported multiple injuries (74 reported tw o injuries, 10 reported three injuries); 55% (256) of male runners and 51% (176) of female runners reported at least one RRI. Runners reported that about 89% of self-reported injuries were diagnosed by either a physician or a physiotherapist. In total, 516 RRIs were reported. Table 2A shows the injury type of RRIs. PFPS was the most-reported injury (20%), MTSS (17%). Table 2B shows the anatomical sites of RRIs. The knee (45%) was the most-frequently reported injury location, followed by the lower leg/Achilles tendon (26%). Tables 3 and 4 describe running injury type and location by gender.

Table 2.

Running-related injury types* and injury location

| A. Running-related injury | B. Location of injury | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Injury | Total n (%*) |

Location | Total n (%) |

| PFPS | 102 (19.8) | Knee | 230 (44.6) |

| MTSS | 87 (16.9) | Lower leg/Achilles | 135 (26.2) |

| Thigh strain | 45 (8.7) | Foot/toe | 48 (9.3) |

| Meniscus or cartilage injury | 42 (8.1) | Ankle | 36 (7.0) |

| ITBS | 36 (7.0) | Hip/groin/buttock | 29 (5.6) |

| AT | 36 (7.0) | Thigh | 23 (4.5) |

| Ankle sprain | 35 (6.8) | Lower back | 15 (2.9) |

| PF | 28 (5.4) | ||

| PT | 20 (3.9) | ||

| Knee sprain | 12 (2.3) | ||

| Calf strain | 11 (2.1) | ||

| Others | 62 (12.0) | ||

* Proportion of any RRI in total RRIs. Abbreviations: PFPS patellofemoral pain syndrome. MTSS medial tibial stress syndrome, ITBS iliotibial band syndrome, AT Achilles tendon injury, PF plantar fasciitis, PT patellar tendinopathy

Table 3.

Description of running injury type among gender. Data are n (%).

| Injury | Women | Men |

|---|---|---|

| PFPS | 48 (27.3) | 52 (21.1) |

| MTSS | 31 (17.6) | 56 (21.9) |

| Thigh strain | 18 (10.2) | 27 (10.5) |

| Meniscus or cartilage injury | 18 (10.2) | 24 (9.4) |

| ITBS | 12 (6.8) | 24 (9.4) |

| AT | 8 (4.5) | 28 (10.9) |

| Ankle sprain | 21 (11.9) | 14 (5.5) |

| PF | 12 (6.8) | 16 (6.3) |

| PT | 4 (2.3) | 16 (6.3) |

| Knee sprain | 6 (3.4) | 6 (2.3) |

| Calf strain | 2 (1.1) | 9 (3.5) |

| Others | 29 (16.5) | 33 (12.9) |

* Proportion of any RRI among sex*injured (injured sex). PFPS patellofemoral pain syndrome, MTSS medial tibial stress syndrome, ITBS iliotibial band syndrome, AT Achilles tendon injuries, PF plantar fasciitis, PT patellar tendinopathy.

Table 4.

Description of injury location among gender. Data are n (%).

| Injury | Women | Men |

|---|---|---|

| Knee | 95 (0.45) | 135 (0.44) |

| Lower leg | 34 (0.16) | 65 (0.21) |

| Foot/toe | 21 (0.10) | 27 (0.09) |

| Ankle | 22 (0.11) | 14 (0.05) |

| Achilles | 8 (0.04) | 28 (0.09) |

| Hip/groin/buttock | 11 (0.05) | 18 (0.06) |

| Thigh | 10 (0.05) | 13 (0.04) |

| Lower back | 8 (0.04) | 7 (0.02) |

Running injuries and associated factors

Table 5 shows the results of univariate logistic regression analysis between runners with and without history of injury. A higher obsessive passion for running, lower perceived health, running over 20 km/week and 60 min/sessions, being overweight, pes planus or cavus, running on hard surfaces, and performing other sports are the factors significantly associated with running-related lower limb injuries (p < 0.05).

Table 5.

Results of univariate logistic regression analysis, injury versus injury-free runners.

| Variable | OR (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|

| Sex (male R) | 0.85 (0.65-1.13) | 0.27 |

| Age | 1.0 (0.98-1.02) | 0.97 |

| Obsessive passion | 1.36 (1.22-1.52) | <0.001* |

| BREQ-2 | 1.04 (0.99-1.08) | 0.122* |

| Sleep quality | 1.24 (1.17-1.31) | <0.001* |

| RAND 36-items | 0.97 (0.95-0.98) | <0.001* |

| SQUASH | 1.00 (1.00-1.00) | 0.43 |

| Running distance (km) | ||

| Up to 10R | Reference | |

| Between 10 & 20 | 1.0 (0.72-1.39) | 0.99 |

| Over 20 | 1.75 (1.24-2.48) | 0.002* |

| Running Experience (years) | ||

| Up to 2R | Reference | |

| Between 2 & 5 | 0.80 (0.57-1.12) | 0.20 |

| Over 5 | 1.27 (0.87-1.83) | 0.22 |

| Training sessions (No/pw) | ||

| Up to 3R | Reference | |

| Over 3 | 0.91 (0.67-1.22) | 0.52 |

| Running duration (min/session) | ||

| Up to 60R | Reference | |

| Over 60 | 1.54 (1.16-2.05) | 0.003* |

| BMI | ||

| Normal R | Reference | |

| Overweight | 1.45 (1.01-2.09) | 0.043* |

| Obese | 0.61 (0.17-2.19) | 0.45 |

| Foot type | ||

| Normal R | Reference | |

| Pes planus | 2.12 (1.42-3.17) | <0.001* |

| Pes cavus | 2.92 (1.48-5.74) | 0.002* |

| Training surface | ||

| Hard | 1.30 (1.14-1.48) | <0.001* |

| Soft | 0.95 (0.78-1.15) | 0.60 |

| Treadmill | 0.88 (0.75-1.02) | 0.08* |

| Others | 1.11 (0.90-1.41) | 0.35 |

| Running company (alone R) | 1.28 (0.95-1.73) | 0.11* |

| Running program (no R) | 1.35 (1.02-1.78) | 0.036* |

| Other sports (No R) | 1.50 (1.06-2.12) | 0.022* |

| Special shoes (yes R) | 1.24 (0.92-1.68) | 0.16* |

| Special insole (yes R) | 1.32 (1.03-2.27) | 0.11* |

| Warm-up (yes R) | 1.48 (0.87-2.50) | 0.15* |

| Cool-down (yes R) | 0.97 (0.67-1.41) | 0.86 |

| Foot strike | ||

| Rearfoot R | Reference | |

| Midfoot | 1.22 (0.94-2.00) | 0.088* |

| Forefoot | 0.98 (0.68-1.42) | 0.92 |

R reference values.

* variables entered into multivariable logistic analysis for injured vs. non-injured runners.

Table 6 shows the results of multivariable logistic regression analysis of risk factors associated with each injury type. Results of multivariable logistic regression analysis for calf strain and knee sprain are reported in Table 7. Associated factors for RRIs were: obsessive passion (OR 1.35, 95%CI 1.18-1.54), motivation to exercise (OR 1.09, 95%CI 1.03-1.15), sleep quality (OR 1.23, 95%CI 1.15-1.31), perceived health (OR 0.96, 95%CI 0.94-0.97), running over 20 km/week (OR 1.58, 95%CI 1.04-2.42), overweight (OR 2.17, 95%CI 1.41-3.34), pes planus (OR 1.80, 95%CI 1.12-2.88), hard surface (OR 1.37, 95%CI 1.17-1.59), running company (OR 1.65, 95%CI 1.16-2.35), and following a training program (OR 1.51, 95%CI 1.09-2.10). Nagelkerke R2 indicates that the predictor variables together can explain 30% of the variance in RRIs. The classification accuracy indicates that the model was correct 71% of the time.

Table 6.

Results of multivariable logistic regression analysis* for each specific injury type.

| Variables\Injury | Injured runners | PFPS | MTSS | Thigh strain | Meniscus injuries | ITBS | AT | Ankle sprain | PF | PT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Obsessive passion | 1.35 (1.18-1.54), p < 0.001 |

1.50 (1.24-1.81), p < 0.001 |

1.33 (1.08-1.63), p = 0.008 |

1.31 (1.01-1.71), p = 0.047 |

2.93 (2.00-4.30), p < 0.001 |

1.67 (1.12-2.50), p = 0.012 |

1.76 (1.24-2.50), p = 0.002 |

|||

| Motivation to exercise (BREQ-2) | 1.09 (1.03-1.15), p = 0.003 |

1.11 (1.01-1.21), p = 0.030 |

1.18 (1.04-1.34), p = 0.011 |

1.43 (1.19-1.71), p < 0.001 |

1.30 (1.09-1.56), p = 0.003 |

|||||

| Sleep quality | 1.23 (1.15-1.31), p < 0.001 | 1.14 (1.02-1.27), p = 0.022 |

1.19 (1.07-1.33), p = 0.002 |

1.21 (1.05-1.38), p = 0.008 |

1.23 (1.06-1.43), p = 0.006 |

1.58 (1.29-1.93), p < 0.001 |

1.27 (1.06-1.54), p = 0.012 |

1.39 (1.07-1.79), p = 0.012 |

1.24 (1.01-1.53), p = 0.049 |

|

| Perceived health (RAND 36) | 0.96 (0.94-0.97), p < 0.001 |

0.96 (0.93-0.98), p = 0.001 |

0.95 (0.93-0.98), P < 0.001 |

0.95 (0.92-0.98), p = 0.001 |

0.92 (0.89-0.95), p < 0.001 |

0.93 (0.89-0.97), P < 0.001 |

0.95 (0.91-0.98), p = 0.004 |

0.94 (0.91-0.98), P = 0.002 |

||

| Over 20 km/week | 1.58 (1.04-2.42), p = 0.034 | 2.18 (1.10-4.33), p = 0.025 |

3.22 (1.10-9.37), p = 0.032 | 3.01 (1.03-8.80), p = 0.045 |

12.65 (2.55-62.73), p = 0.002 |

|||||

| 2-5 years’ experience | 7.88 (1.82-34.11), p = 0.006 |

|||||||||

| Over 5 years’ experience | 10.79 (2.15-54.23), p = 0.004 |

|||||||||

| Pes planus | 1.80 (1.12-2.88), p = 0.016 |

1.81 (1.02-3.85), p = 0.045 |

3.16 (1.32-7.54), p = 0.010 |

4.34 (1.55-12.18), p = 0.005 | 4.31 (1.59-11.70), p = 0.004 | 43.31 (10.63-176.45), p < 0.001 | ||||

| Pes cavus | 4.06 (1.46-11.25), p = 0.007 | 3.91 (1.21-12.63), p = 0.023 | 3.06 (0.84-11.14), p = 0.090 | 11.02 (2.44-49.77), p = 0.002 | ||||||

| Hard surface | 1.37 (1.17-1.59), p < 0.001 |

1.42 (1.11-1.81), p = 0.005 |

1.68 (1.31-2.15), p < 0.001 |

1.45 (1.07-1.96), p = 0.017 |

1.43 (1.00-2.03), p = 0.049 |

|||||

| Running company | 1.65 (1.16-2.35), p = 0.005 |

2.16 (1.26-3.72), p = 0.005 |

2.27 (1.28-4.04), p = 0.005 |

|||||||

| Training program | 1.51 (1.09-2.10), p = 0.014 | 2.73 (1.52-4.89), p = 0.001 |

2.48 (1.24-4.99), p = 0.011 |

3.43 (1.53-7.65), p = 0.003 |

0.18 (0.04-0.76), p = 0.020 |

|||||

| Other sports | 3.37 (1.13-10.07), p = 0.030 | |||||||||

| Special insole | 4.92 (1.61-15.0), p = 0.005 |

|||||||||

| Special shoes | 3.43 (1.32-8.87), p = 0.011 |

|||||||||

| Warm up | 0.20 (0.05-0.81), p = 0.024 |

|||||||||

| Nagelkerke R2 (%) | 30 | 29 | 30 | 20 | 28 | 30 | 50 | 43 | 57 | 22 |

| Classification accuracy (%) | 71 | 81 | 82 | 90 | 92 | 92 | 95 | 95 | 99 | 95 |

* Odds ratio (95% CI) for categorical variables compared to the references specified in Table 3.PFPS patellofemoral pain syndrome, MTSS medial tibial stress syndrome, ITBS iliotibial band syndrome, AT Achilles tendon injuries, PF plantar fasciitis, PT patellar tendinopathy.

Table 7.

Results of multivariate logistic regression analysis for calf strain and knee sprain

| Injury | Calf strain | Knee sprain | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sleep quality | 1.27 (1.03-1.57), p = 0.023 | ||

| Perceived health (RAND 36) | 0.91 (0.86-0.97), p= 0.003 | ||

| 2-5 years’ experience | 19.80 (2.72-144.43), p = 0.030 | ||

| Over 5 years’ experience | 7.95 (1.01-62.57), p = 0.049 | 11.59 (2.22-60.39), p = 0.004 | |

| Overweight | 12.17 (2.21-67.10), p = 0.004 | ||

| Pes planus | 12.04 (2.14-67.57), p = 0.005 | ||

| Pes cavus | 24.71 (2.50-244.13), p = 0.006 | ||

| Nagelkerke R2 (%) | 50 | 32 | |

| Classification accuracy (%) | 92 | 84 | |

Association of mental aspects and sleep quality with RRIs

The results of the multivariable regression analysis (Table 6) revealed that mental aspects and sleep quality together with other abovementioned factors compose a model of risk factors associated with RRIs. We conducted a separate multivariable logistic regression analysis with only mental aspects and sleep quality included as covariates to analyze the association of these factors with RRIs. The results were as follows: obsessive passion (OR 1.34, 95%CI 1.19-1.50, p < 0.001), motivation to exercise (OR 1.07, 95%CI 1.01-1.12, p = 0.012), sleep quality (OR 1.25, 95%CI 1.18-1.33, p < 0.001). Nagelkerke R2 indicates that these factors can explain 15% of the variance in RRIs. The classification accuracy indicates that this model was correct in 62% of the time.

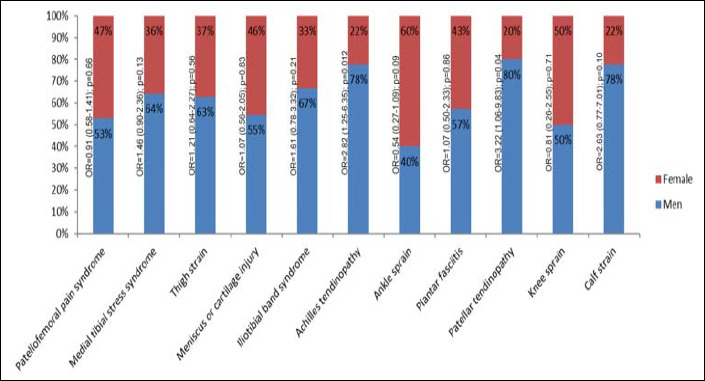

Association between running injury types and risk factors

Figure 1 shows the distribution of each RRI between male and female runners. Frequency of each RRI was compared between injured male and female runners using the chi-square test. Men reported more AT than women (77.8% vs 22.2%, X2 (1, N = 432) = 5.58, p = 0.018) and more PT than women (80% vs 20%, X2 (1, N = 432) = 4.73, p = 0.040); women reported more ankle sprains than men (60% vs 40%, X2 (1, N = 432) = 5.85, p = 0.016). No significant differences were found for frequencies of other RRI types between injured male and female runners (p > 0.05). The results of univariate logistic regression showed that male had higher odds of reporting AT (OR 2.82, 95%CI 1.25-6.25) and PT (OR 3.22, 95%CI 1.06-9.83) than female.

Figure 1.

Distribution of each RRI type between male and female runners (sex*injured). OR odds ratio (95%CI).

The results of multivariable logistic regression are described for PFPS, MTSS, ITBS, and AT. The factors associated with PFPS were (Table 6): obsessive passion (OR 1.50, 95%CI 1.24-1.81), motivation to exercise (OR 1.11, 95%CI 1.01-1.21), sleep quality (OR 1.14, 95%CI 1.02-1.27), perceived health (OR 0.96, 95%CI 0.93-0.98), running over 20 km/week (OR 2.18, 95%CI 1.10-4.33), over 3 sessions/week (OR 0.37, 95%CI 0.19-0.73), pes planus (OR 1.81, 95%CI 1.02-3.85), pes cavus (OR 4.06, 95%CI 1.46-11.25), hard surface (OR 1.42, 95%CI 1.11-1.81), and running company (OR 2.16, 95%CI 1.26-3.72). Nagelkerke R2 indicates that the predictor variables together were able to explain 29% of the variance in RRIs. The classification accuracy indicates that the model was correct 81% of the time.

The final step of the backward stepwise method of multivariable logistic regression for variables associated with MTSS includes (Table 6): obsessive passion (OR 1.33, 95%CI 1.08-1.63), sleep quality (OR 1.19, 95%CI 1.07-1.33), perceived health (OR 0.95, 95%CI 0.93-0.98), over 3 sessions/week (OR 0.33, 95%CI 0.16-0.67), pes cavus (OR 3.91, 95%CI 1.21-12.63), hard surface (OR 1.68, 95%CI 1.31-2.15), and running company (OR 2.27, 95%CI 1.28-4.04), and following a training program (OR 2.73, 95%CI 1.52-4.89). Nagelkerke R2 indicates that the predictor variables together were able to explain 30% of the variance in RRIs. The classification accuracy indicates that the model was correct 82% of the time.

Discussion

The aims of the current study were to investigate the epidemiology of RRIs in recreational runners and the association of mental aspects, sleep, and other potential risk factors with RRIs. We analyzed 804 questionnaires, 432 (54%) reporting at least one RRI. The most-reported injury was PFPS (20%), followed by MTSS (17%). The most affected injury location was the knee (45%), followed by the lower leg/Achilles tendon (26%). Greater obsessive passion, motivation, poor sleep quality, lower perceived health, running over 20 km/w, overweight, having pes planus and/or cavus, hard surface running, and running in a group were associated with RRIs. Our study highlights the role of mental aspects and sleep quality in RRIs. These two factors account for half of the total variance explained by all factors in RRIs (15% vs. 30%).

Epidemiology

The prevalence of RRIs over the previous six months was 54%. This number is in accordance with previous studies on RRIs in recreational runners, reporting a 36.5-79.3% prevalence (Borel et al., 2019; Hespanhol et al., 2013, 2016; Van Gent et al., 2007). The period over which injuries are reported and injury definition used may affect incidence. The most-reported injury was PFPS, in line with previous studies (Francis et al., 2019; Hespanhol et al., 2012; Lopes et al., 2012). MTSS was the second-most commonly reported RRI. Prevalence of PFPS (20) and MTSS (17) exceed other RRIs (<9). Men reported more AT (78% vs. 22%) and PT (80% vs. 20%) than women; women reported more ankle sprains than men (60% vs.40%). We found only one study that classified RRIs by gender (McKean, K. A.; Manson, N. A.; Stanish, 2004). In line with ours, that study reported more AT in men than in women. The knee was the most-affected injury site, with 44% of injuries attributed to a higher proportion of PFPS. This number is in line with previous studies identifying the knee as the most-common injured location in runners (Francis et al., 2019; Hespanhol et al., 2016; Linton and Valentin, 2018; Lopes et al., 2012). The high rate of knee injuries may be attributed to the greater accumulated impact forces imposed on it when running (Jafarnezhadgero et al., 2018).

Mental aspects and sleep

Having more obsessive passion for running is associated with higher odds for RRIs. In other words, runners with a more obsessively passionate attitude are more likely to report RRIs. Previous studies concluded that mental aspects such as harmonious and obsessive passionate attitude and mental detachment affect injury incidence (Balk et al., 2019; De Jonge et al., 2020; Wiese-Bjornstal, 2019) and injury rehabilitation (Ardern et al., 2013). Mental aspects influence training variables such as the training loads that a runner can tolerate before incurring an injury (Vallerand, 2010). Obsessive passion for running is a strong motivation toward running; runners keep running regardless of their abilities and physical capacities (Vallerand et al., 2003). The effect of obsessive passion gained significance when an analysis of our runners revealed that runners reporting multiple injuries scored significantly higher obsessive passion than those with one injury. In fact, obsessive passion drives runners to keep on running while injured. This can lead to multiple, recurrent and gradual onset injuries. Our results are in line with a recently published study showing that runners with more obsessive passion are more likely to report RRIs (De Jonge et al., 2020). Because of their obsessive passion for running these runners do not sufficiently weigh the situation and circumstances leading to running excesses, thereby predisposing themselves to RRIs.

Poor sleep quality is also associated with higher odds for RRIs. In other words, runners with poorer sleep quality are more likely to report RRIs. Previous studies highlighted lack of sleep as a risk factor for sports injuries (Gao et al., 2019; Luke et al., 2011; Milewski et al., 2014; von Rosen et al., 2017) while considering only sleep duration. One study showed that less than 8 hours of sleep per night is associated with increased risk of injuries in adolescent athletes (Milewski et al., 2014). It seems that exploring sleep quality that reflects sleep characteristics, as measured in our study, can be more relevant to studying sports injuries than exploring sleep duration alone. Good sleep quality is necessary for adequate adaptation and repair of muscles, and increases concentration (Gao et al., 2019). This results in better recovery and improved performance in sports activities like running. Poor sleep quality, on the other hand, increases the risk for injuries (Milewski et al., 2014). One should realize that being injured contributes to poor sleep quality. Hence due to our study design it remains unclear whether poor sleep quality is cause or consequence of RRIs.

Perceived health

Perceived health, which refers to a person’s general perception of her/his health, might be linked to injury (Messier et al., 2018; Raysmith and Drew, 2016). Low perceived health has been reported as a reason to discontinue running (Fokkema et al., 2019). We also found an association between perceived health and RRIs. Runners with a history of injury reported lower RAND 36-item scores than those without any such history. A reduced RAND-36 score was shown for all types of RRIs (except for PF and PT). Our analysis showed that injured female runners reported significantly lower perceived health than their male counterparts. Injuries seem to have more perceived health effects in women than men, or it could be that women with lower perceived health are more prone to injury than men.

Training-related factors

Running over 20 km/w (OR 1.58-12.68) was associated with an increased risk for RRIs, which may imply that runners should reduce their weekly running distance to a lower level of 20 km/w to prevent RRIs. Contradictory results have been reported in the literature so far on running distance and RRIs (Nielsen et al., 2012; Van Der Worp et al., 2015). It seems that a safe running distance may vary between populations and is related to other training factors such as running duration, frequency and speed (Damsted et al., 2018).

Running on hard surfaces had between 1.37 and 1.68 higher odds of RRIs. Two studies highlighted hard-surface running as a risk for RRIs (Hespanhol et al., 2012; Wen et al., 1997). By contrast, a prospective study reported that hard surface is not associated with RRIs in recreational runners (Hespanhol et al., 2013). Our results showed that hard-surface running was one of the contributing factors for the four most common RRIs. These results may account for hard-surface running causing greater musculoskeletal stress to the lower limbs than any other surface (Tessutti et al., 2012). Hard surface may affect the distribution of load to the lower limb by altering lower limb biomechanics during running (Hardin et al., 2004). About 82% of runners reported at least one session/week running on asphalt and/or cement, surfaces that are most easily accessible. Results showed that treadmill running is associated with lower reporting of MTSS (OR 0.71) – perhaps because it reduces the total stress on the lower leg musculoskeletal system compared to hard surfaces (Dierick et al., 2004).

Running in a group was associated with 1.65 times higher odds of reporting injuries. Nevertheless, it is difficult to conclude the causative effect of the association between running in a group or alone and RRIs. Our results showed that about 51% of runners who ran in a group followed a training program. Also, those following a training program showed higher odds of RRIs and MTSS. Group runners most likely all follow the same training program. It may therefore be concluded that following the same group running program may increase the odds of RRIs. This indeed underlines the individuality principle in sports training. We therefore recommend individualization of training programs for runners.

Foot arch type

Pes planus and cavus are significantly associated with most of the RRIs. A subgroup analysis revealed that about 50% of runners reporting multiple injuries had either pes planus or pes cavus. About 80% of runners reporting PF had either pes planus or pes cavus. Previous studies also highlighted the importance of foot arch for RRIs (Kaufman et al., 1999; Pérez-Morcillo et al., 2019; Williams et al., 2001). A recent study showed that pes planus and cavus are associated with 20 to 77 times higher odds of RRIs than normal feet, respectively (Pérez-Morcillo et al., 2019). A systematic review reported that pes planus and cavus are associated with lower limb injuries (Tong and Kong, 2013). Another systematic review reported strong and limited evidence that pes planus is a risk factor for MTSS and PFPS, respectively (Neal et al., 2014).

Limitations and strengths

Our survey results should be interpreted with caution. This is a cross-sectional study, so it is difficult to determine the causative association between risk factors and RRIs. Recall bias could also be a limitation of our study because all data were collected using a self-reported questionnaire. Injuries and foot type were self-reported; however, runners reported that 93% of injuries and 89% of foot types (Tables 8 and 9) were reported based on consultation with their physician or physiotherapist, which increases the validity of these data. To minimize this bias we also provided runners with a clear definition for each RRI and foot arch type. The measurement of foot arch type was not matched for all runners so it can bias the results of foot arch type. This is the first study investigating the association of mental aspects and sleep quality with RRIs. As our results showed the association of these factors with RRIs, future prospective studies are warranted among recreational runners to substantiate whether these factors are risk factors for RRIs.

Table 8.

Self-reported results showing who diagnosed running-related injuries.

| Who diagnosed | PFPS | MTSS | Thigh strain | Meniscus injuries | ITBS | AT | Ankle sprain | PF | PT | Knee sprain | Calf strain | Others | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physician or physiotherapist | 102 | 86 | 41 | 42 | 35 | 35 | 32 | 28 | 20 | 12 | 9 | 40 | |

| Sports expert or running coach | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 10 | ||||||

| Myself | 2 | 1 | 9 | ||||||||||

| Others | 1 | 3 | |||||||||||

| Total | 102 | 87 | 45 | 42 | 36 | 36 | 35 | 28 | 20 | 12 | 11 | 62 | |

PFPS patellofemoral pain syndrome, MTSS medial tibial stress syndrome, ITBS iliotibial band syndrome, AT Achilles tendon injuries, PF plantar fasciitis, PT patellar tendinopathy.

Table 9.

Self-reported results showing who diagnosed foot types.

| Who diagnosed | Foot arch type | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | Pes planus | Pes cavus | |

| Physician or physiotherapist | 498 | 121 | 42 |

| Sports expert or coach | 52 | 8 | 4 |

| Myself | 5 | 1 | |

| Others | 9 | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 564 | 131 | 47 |

Practical implications

Amongst training-related factors and foot type, mental aspects and sleep should also be considered to prevent and/or manage RRIs. We therefore recommend personalized training programs that include 1) counseling to increase awareness of the potential risk of obsessive passion for running as well as the importance of good and sufficient sleep, 2) controlling running distance and reducing running on hard surfaces, and 3) consideration to correcting pes planus and cavus. Passionate runners should be encouraged to follow education programs in order to integrate running more harmoniously because harmonious passion is assumed to lead to flexible persistence and full control of an activity, so that runners can reduce or stop running when encountering with harmful conditions (Bélanger et al., 2013). Several studies have reported exercise and nutritional interventions as effective modalities for improving sleep quality (Chen et al., 2016; Dolezal et al., 2017; Halson, 2014). These interventions might be helpful to improve runners’ sleep quality. Interventions such as using foot orthoses, exercise programs and gait retraining modalities have been reported as effective for modifying pes planus and cavus (Jafarnezhadgero et al., 2017; Kim and Kim, 2016; Mousavi, 2020; Mousavi et al., 2021).

Conclusion

Over the past six months, 54% of recreational runners reported having an RRI. Our results on the association of mental aspects and sleep quality with RRIs add new insights to the literature on the complex and multifactorial etiology of RRIs. More research is needed to determine causality between these factors and RRIs. Researchers and clinicians are advised to consider these factors toward preventing and/or managing RRIs.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully thank Dr. Behrooz Alizadeh for the help as an epidemiologist on this manuscript. The experiments comply with the current laws of the country in which they were performed. The authors have no conflict of interest to declare. The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available, but are available from the corresponding author who was an organizer of the study.

Biographies

Seyed Hamed MOUSAVI

Employment

Assistant professor at the University of Tehran, Department of Health and Sport Medicine, Faculty of Physical Education and Sport Sciences. Tehran, Iran.

Degree

PhD

Research interests

Biomechanics of running related injuries

E-mail: s.h.mousavi@umcg.nl

Juha M. HIJMANS

Employment

Associate professor and head of the Motion Lab UMCG, university of Groningen, The Netherlands.

Degree

PhD

Research interests

Rehabilitation and motion analysis lab

E-mail: j.m.hijmans@umcg.nl

Hooman MINOONEJAD

Employment

Associate professor and head of the Department of Health and Sport Medicine, Faculty of Physical Education and Sport Sciences. University of Tehran, Iran.

Degree

PhD

Research interests

Sports injuries

E-mail: h.minoonejad@ut.ac.ir

Reza RAJABI

Employment

Professor at the University of Tehran, Department of Health and Sport Medicine, Faculty of Physical Education and Sport Sciences. Tehran, Iran.

Degree

PhD

Research interests

Corrective exercises and musculoskeletal measurements.

E-mail: rrajabi@ut.ac.ir

Johannes ZWERVER

Employment

A sports physician at Sports Valley, Ede and professor of sport & exercise medicine at the University of Groningen in the Netherlands.

Degree

PhD

Research interests

Prevention and management of sports injuries

E-mail: j.zwerver@umcg.nl

References

- Abdi J., Efthekhar H., Mahmodi M., Shojaeizadeh D., Sadeghi R. (2016) Physical activity status of employees of governmental departments in Hamadan, Iran: An application of the transtheoretical model. Health System Reseach 12(1), 50-57. [Google Scholar]

- Akehurst S., Oliver E. J. (2014) Obsessive passion: a dependency associated with injury-related risky behaviour in dancers. Journal of Sports Sciences 32(3), 259-267. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2013.823223 10.1080/02640414.2013.823223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ardern C. L., Taylor N. F., Feller J. A., Webster K. E. (2013) A systematic review of the psychological factors associated with returning to sport following injury. British Journal of Sports Medicine 47(17), 1120-1126. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2012-091203 10.1136/bjsports-2012-091203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balk Y. A., de Jonge J., Oerlemans W. G. M., Geurts S. A. E. (2019) Physical recovery, mental detachment and sleep as predictors of injury and mental energy. Journal of Health Psychology 24(13), 1828-1838. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105317705980 10.1177/1359105317705980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bélanger J. J., Lafrenière M. A. K., Vallerand R. J., Kruglanski A. W. (2013) Driven by fear: The effect of success and failure information on passionate individuals’ performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 104(1), 180-195. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029585 10.1037/a0029585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borel W. P., Filho J. E., Diz J. B. M., Moreira P. F., Veras P. M., Catharino L. L., Rossi B. P., Felício D. C. (2019) Prevalence of injuries in brazilian recreational street runners: Meta-analysis. Revista Brasileira de Medicina Do Esporte 25(2), 161-167. https://doi.org/10.1590/1517-869220192502214466 10.1590/1517-869220192502214466 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buysse D. J., Reynolds C. F., Monk T. H., Berman S. R., Kupfer D. J. (1989) The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Research 28(2), 193-213. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceyssens L., Vanelderen R., Barton C., Malliaras P., Dingenen B. (2019) Biomechanical risk factors associated with running-related injuries: A systematic review. Sports Medicine 49(7), 1095-1115. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-019-01110-z 10.1007/s40279-019-01110-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L. J., Fox K. R., Ku P. W., Chang Y. W. (2016) Effects of Aquatic Exercise on Sleep in Older Adults with Mild Sleep Impairment: a Randomized Controlled Trial. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine 23(4), 501-506. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-015-9492-0 10.1007/s12529-015-9492-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damsted C., Glad S., Nielsen R. O., Sørensen H., Malisoux L. (2018) Is there evidence for an association between changes in training load and running-related injuries? a systematic review. International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy 13(6), 931-942. https://doi.org/10.26603/ijspt20180931 10.26603/ijspt20180931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jonge J., Balk Y. A., Taris T. W. (2020) Mental recovery and running-related injuries in recreational runners: The moderating role of passion for running. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17(3), 1044. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17031044 10.3390/ijerph17031044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dierick F., Penta M., Renaut D., Detrembleur C. (2004) A force measuring treadmill in clinical gait analysis. Gait and Posture 20(3), 299-303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaitpost.2003.11.001 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2003.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolezal B. A., Neufeld E. V., Boland D. M., Martin J. L., Cooper C. B. (2017) Interrelationship between Sleep and Exercise: A Systematic Review. Advances in Preventive Medicine (2017), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/1364387 10.1155/2017/1364387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durmer J. S., Dinges D. F. (2005) Neurocognitive consequences of sleep deprivation. Seminars in Neurology 25(1), 117-129. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2005-867080 10.1055/s-2005-867080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmanbar R., Niknami S., Hidarnia A., Lubans D. R. (2011) Psychometric properties of the Iranian version of the Behavioral Regulation in Exercise Questionnaire-2 (BREQ-2). Health Promotion Perspectives 1(2), 95-104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrahi M. J., Nakhaee N., Sheibani V., Garrusi B., Amirkafi A. (2012) Reliability and validity of the Persian version of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI-P). Sleep and Breathing 16(1), 79-82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11325-010-0478-5 10.1007/s11325-010-0478-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch C. (2006) A new framework for research leading to sports injury prevention. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport 9(1-2), 3-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2006.02.009 10.1016/j.jsams.2006.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fokkema T., Hartgens F., Kluitenberg B., Verhagen E., Backx F. J. G., van der Worp H., Bierma-Zeinstra S. M. A., Koes B. W., van Middelkoop M. (2019) Reasons and predictors of discontinuation of running after a running program for novice runners. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport 22(1), 106-111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2018.06.003 10.1016/j.jsams.2018.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis P., Whatman C., Sheerin K., Hume P., Johnson M. I. (2019) The Proportion of lower limb running injuries by gender, anatomical location and specific pathology: A systematic review. Journal of Sports Science & Medicine 18(1), 21-31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao B., Dwivedi S., Milewski M. D., Cruz A. I. (2019) Chronic lack of sleep is associated with increased sports injuries in adolescent: A systematic review and meta analysis. Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine 7(3_suppl), 2325967119S0013. https://doi.org/10.1177/2325967119S00132 10.1177/2325967119S00132 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gijon-Nogueron G., Fernandez-Villarejo M. (2015) Risk factors and protective factors for lower-extremity running injuries: A systematic review. Journal of the American Podiatric Medical Association 105(6), 532-540. https://doi.org/10.7547/14-069.1 10.7547/14-069.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halson S. L. (2014) Sleep in elite athletes and nutritional interventions to enhance sleep. Sports Medicine 44(Suppl 1), 13-23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-014-0147-0 10.1007/s40279-014-0147-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardin E. C., Van Den Bogert A. J., Hamill J. (2004) Kinematic Adaptations during Running: Effects of Footwear, Surface, and Duration. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise 36(5), 838-844 https://doi.org/10.1249/01.MSS.0000126605.65966.40 10.1249/01.MSS.0000126605.65966.40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hays R. D., Sherbourne C. D., Mazel R. M. (1993) The rand 36-item health survey 1.0. Health Economics 2(3), 217-227. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.4730020305 10.1002/hec.4730020305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hespanhol J., L. C., Costa L. O. P., Carvalho A. C. A., Lopes A. D. (2012) A description of training characteristics and its association with previous musculoskeletal injuries in recreational runners: a cross-sectional study. Brazilian Journal of Physical Therapy 16(1), 46-53. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1413-35552012005000005 10.1590/S1413-35552012005000005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hespanhol J., L. C., de Carvalho A. C. A., Costa L. O. P., Lopes A. D. (2016) Lower limb alignment characteristics are not associated with running injuries in runners: Prospective cohort study. European Journal of Sport Science 16(8), 1137-1144. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2016.1195878 10.1080/17461391.2016.1195878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hespanhol J., L. C., Pena Costa, L. O., Lopes A. D. (2013) Previous injuries and some training characteristics predict running-related injuries in recreational runners: A prospective cohort study. Journal of Physiotherapy 59(4), 263-269. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1836-9553(13)70203-0 10.1016/S1836-9553(13)70203-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivarsson A., Johnson U., andersen M. B., Tranaeus U., Stenling A., Lindwall M. (2017) Psychosocial factors and sport Injuries: Meta-analyses for prediction and prevention. Sports Medicine 47(2), 353-365. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-016-0578-x 10.1007/s40279-016-0578-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jafari S. F., Nikbakhs R., Safania A. (2018) Validating and normalizing passion questionnaire among athletes. Journal of Psychological Science 17(68), 471-479. [Google Scholar]

- Jafarnezhadgero A. A., Oliveira A. S., Mousavi S. H., Madadi-Shad M. (2018) Combining valgus knee brace and lateral foot wedges reduces external forces and moments in osteoarthritis patients. Gait and Posture 59, 104-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jafarnezhadgero Amir Ali, Majlesi M., Azadian E. (2017) Gait ground reaction force characteristics in deaf and hearing children. Gait & Posture 53, 236-240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaitpost.2017.09.040 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2017.09.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson U., Ivarsson A. (2017) Psychosocial factors and sport injuries: prediction, prevention and future research directions. Current Opinion in Psychology 16, 89-92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.04.023 10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.04.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman K. R., Brodine S. K., Shaffer R. a, Johnson C. W., Cullison T. R. (1999) The effect of foot structure and range of motion on musculoskeletal overuse injuries. The American Journal of Sports Medicine 27(5), 585-593. https://doi.org/10.1177/03635465990270050701 10.1177/03635465990270050701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim E. K., Kim J. S. (2016) The effects of short foot exercises and arch support insoles on improvement in the medial longitudinal arch and dynamic balance of flexible flatfoot patients. Journal of Physical Therapy Science 28(11), 3136-3139. https://doi.org/10.1589/jpts.28.3136 10.1589/jpts.28.3136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D.-C., Pate R. R., Lavie C. J., Sui X., Church T. S., Blair S. N. (2014) Leisure-time running reduces all-cause and cardiovascular mortality risk. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 64(5), 472-481. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2014.04.058 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.04.058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenstein M. B., Jensen T. T. (2016) Exercise addiction in CrossFit: Prevalence and psychometric properties of the Exercise Addiction Inventory. Addictive Behaviors Reports 13(3), 33-37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.abrep.2016.02.002 10.1016/j.abrep.2016.02.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linton L., Valentin S. (2018) Running with injury: A study of UK novice and recreational runners and factors associated with running related injury. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport 21(12), 1221-1225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2018.05.021 10.1016/j.jsams.2018.05.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopes A. D., Hespanhol L. C., Junior, Yeung S. S., Costa L. O. (2012) What are the main running-related musculoskeletal injuries? A Systematic Review. Sports Medicine 42(10), 891-905. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03262301 10.1007/BF03262301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luke A., Lazaro R. M., Bergeron M. F., Keyser L., Benjamin H., Brenner J., D’Hemecourt P., Grady M., Philpott J., Smith A. (2011) Sports-related injuries in youth athletes: Is overscheduling a risk factor? Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine 21(4), 307-314. https://doi.org/10.1097/JSM.0b013e3182218f71 10.1097/JSM.0b013e3182218f71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markland D., Tobin V. (2004) A modification to the behavioural regulation in exercise questionnaire to include an assessment of amotivation. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology 26(2), 191-196. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.26.2.191 10.1123/jsep.26.2.191 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McKean K. A., Manson N. A., Stanish W. D. (2004) Gender differences in running injuries. Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine 14(6), 377. https://doi.org/10.1097/00042752-200411000-00024 10.1097/00042752-200411000-00024 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Messier S. P., Martin D. F., Mihalko S. L., Ip E., DeVita P., Cannon D. W., Love M., Beringer D., Saldana S., Fellin R. E., Seay J. F. (2018) A 2-Year prospective cohort study of overuse running injuries: The runners and injury longitudinal study (TRAILS). American Journal of Sports Medicine 46(9), 2211-2221. https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546518773755 10.1177/0363546518773755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milewski M. D., Skaggs D. L., Bishop G. A., Pace J. L., Ibrahim D. A., Wren T. A. L., Barzdukas A. (2014) Chronic lack of sleep is associated with increased sports injuries in adolescent athletes. Journal of Pediatric Orthopedics 34(2), 129-133. https://doi.org/10.1097/BPO.0000000000000151 10.1097/BPO.0000000000000151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montazeri A., Goshtasebi A., Vahdaninia M., Gandek B. (2005) The short form health survey (SF-36): Translation and validation study of the Iranian version. Quality of Life Research 14(3), 875-882. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-004-1014-5 10.1007/s11136-004-1014-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mousavi H. (2020) A step forward in running-related injuries: Risk factors, kinematics and gait retraining [University of Groningen; ]. [Google Scholar]

- Mousavi S. H., Hijmans J. M., Rajabi R., Diercks R., Zwerver J., van der Worp H. (2019) Kinematic risk factors for lower limb tendinopathy in distance runners: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gait and Posture 69, 13-24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaitpost.2019.01.011 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2019.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mousavi S. H., van Kouwenhove L., Rajabi R., Zwerver J., Hijmans J. M. (2021) The effect of changing mediolateral center of pressure on rearfoot eversion during treadmill running. Gait and Posture 83, 201-209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaitpost.2020.10.032 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2020.10.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neal B. S., Griffiths I. B., Dowling G. J., Murley G. S., Munteanu S. E., Franettovich Smith M. M., Collins N. J., Barton C. J. (2014) Foot posture as a risk factor for lower limb overuse injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Foot and Ankle Research 7(1), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13047-014-0055-4 10.1186/s13047-014-0055-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen R. O., Buist I., Sørensen H., Lind M., Rasmussen S. (2012) Training errors and running related injuries: a systematic review. International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy 7(1), 58-75. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien R. M. (2007) A caution regarding rules of thumb for variance inflation factors. Quality and Quantity. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-006-9018-6 10.1007/s11135-006-9018-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Morcillo A., Gómez-Bernal A., Gil-Guillen V. F., Alfaro-Santafé J., Alfaro-Santafé J. V., Quesada J. A., Lopez-Pineda A., Orozco-Beltran D., Carratalá-Munuera C. (2019) Association between the foot posture index and running related injuries: A case-control study. Clinical Biomechanics 61, 217-221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2018.12.019 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2018.12.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raysmith B. P., Drew M. K. (2016) Performance success or failure is influenced by weeks lost to injury and illness in elite Australian track and field athletes: A 5-year prospective study. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport 19(10), 778-783. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2015.12.515 10.1016/j.jsams.2015.12.515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rip B., Fortin S., Vallerand R. J. (2006) The relationship between passion and injury in dance students. Journal of Dance, Medicine & Science 10, 14-20. [Google Scholar]

- Rothschild C. E. (2012) Primitive running: a survey analysis of runners’ interest, participation, and implementation. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 26(8), 2021-2026. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0b013e31823a3c54 10.1519/JSC.0b013e31823a3c54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smits D. W., Huisstede B., Verhagen E., Van Der Worp H., Kluitenberg B., Van Middelkoop M., Hartgens F., Backx F. (2016) Short-term absenteeism and health care utilization due to lower Extremity injuries among novice runners: A prospective cohort study. Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine 26(6), 502-509. https://doi.org/10.1097/JSM.0000000000000287 10.1097/JSM.0000000000000287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephan Y., Deroche T., Brewer B. W., Caudroit J., Le Scanff C. (2009) Predictors of perceived susceptibility to sport-related injury among competitive runners: The role of previous experience, neuroticism, and passion for running. Applied Psychology 58(4), 672-687. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2008.00373.x 10.1111/j.1464-0597.2008.00373.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tessutti V., Ribeiro A. P., Trombini-Souza F., Sacco I. C. N. (2012) Attenuation of foot pressure during running on four different surfaces: Asphalt, concrete, rubber, and natural grass. Journal of Sports Sciences 30(14), 1545-1550. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2012.713975 10.1080/02640414.2012.713975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong J. W. K., Kong P. W. (2013) Association between foot type and lower extremity injuries: systematic literature review with meta-analysis. The Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy 43(10), 700-714. https://doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2013.4225 10.2519/jospt.2013.4225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallerand R. J. (2010) Chapter Three: On passion for life activities: The dualistic model of passion. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology (1st ed., Vol. 42, Issue 10) Elsevier Inc. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(10)42003-1 10.1016/S0065-2601(10)42003-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vallerand R. J., Mageau G. A., Ratelle C., Léonard M., Blanchard C., Koestner R., Gagné M., Marsolais J. (2003) Les Passions de 1’Âme: On Obsessive and Harmonious Passion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 85(4), 756-767. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.85.4.756 10.1037/0022-3514.85.4.756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Worp M. P., Ten Haaf D. S. M., Van Cingel R., De Wijer A., Nijhuis-Van Der Sanden M. W. G., Bart Staal J. (2015) Injuries in runners; a systematic review on risk factors and sex differences. Plos One 10(2), 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0114937 10.1371/journal.pone.0114937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Gent R. N., Siem D., Van Middeloop M., Van Os A. G., Bierma-Zeinstra S. M. A., Koes B. W. (2007) Incidence and determinants of lower extremity running injuries in long distance runners: A systematic review. Sport En Geneeskunde 40(4), 16-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Mechelen W., Hlobil H., Kemper H. C. (1992) Incidence, severity, aetiology and prevention of sports injuries. A review of concepts. Sports Medicine 14(2), 82-99. https://doi.org/10.2165/00007256-199214020-00002 10.2165/00007256-199214020-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Rosen P., Frohm A., Kottorp A., Fridén C., Heijne A. (2017) Too little sleep and an unhealthy diet could increase the risk of sustaining a new injury in adolescent elite athletes. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports 27(11), 1364-1371. https://doi.org/10.1111/sms.12735 10.1111/sms.12735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen D. Y., Puffer J. C., Schmalzried T. P. (1997) Lower extremity alignment and risk of overuse injuries in runners. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise 29(10), 1291-1298. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005768-199710000-00003 10.1097/00005768-199710000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendel-Vos G. C. W., Schuit A. J., Saris W. H. M., Kromhout D. (2003) Reproducibility and relative validity of the short questionnaire to assess health-enhancing physical activity. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 56(12), 1163-1169. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0895-4356(03)00220-8 10.1016/S0895-4356(03)00220-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiese-Bjornstal D. M. (2019) Psychological predictors and consequences of injuries in sport settings. APA handbook of sport and exercise psychology, volume 1: Sport psychology (Vol. 1). (pp. 699-725) American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/0000123-035 10.1037/0000123-035 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Williams D. S., McClay I. S., Hamill J. (2001) Arch structure and injury patterns in runners. Clinical Biomechanics 16(4), 341-347. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0268-0033(01)00005-5 10.1016/S0268-0033(01)00005-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamato T. P., Saragiotto B. T., Lopes A. D. (2015) A consensus definition of running-related injury in recreational runners: A modified delphi approach. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy 45(5), 375-380. https://doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2015.5741 10.2519/jospt.2015.5741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]