Abstract

Objective:

Despite the proliferation of bystander approaches to prevent aggression among youth, theoretical models of violence-related bystander decision making are underdeveloped, particularly among adolescents. The purpose of this research was to examine the utility of 2 theories, the Situational Model of Bystander behavior (SMB) and the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), for identifying mechanisms underlying adolescent bystander behavior in the context of bullying and teen dating violence (TDV).

Method:

Data were collected via face to face (local) and online (national) focus groups with 113 U.S. adolescents aged 14–18 and were subsequently analyzed using deductive and inductive coding methods.

Results:

Youth endorsed beliefs consistent with both the SMB and TPB and with additional constructs not captured by either theory. Adolescents reported a higher proportion of barriers relative to facilitators to taking action, with perceptions of peer norms and social consequences foremost among their concerns. Many influences on bystander behavior were similar across TDV and bullying.

Implications:

Findings are organized into the proposed Situational-Cognitive Model of Adolescent Bystander Behavior, which synthesizes the SMB and TPB, and supports the tailoring of bystander interventions. For teens, intervening is a decision about whether and how to navigate potential social consequences of taking action that unfold over time; intervention approaches must assess and acknowledge these concerns.

Keywords: bullying, teen dating violence, bystander intervention, prevention, adolescence

Increasingly, violence and bullying prevention programs for youth and young adults have incorporated a proactive, positive bystander component. This prevention strategy is designed to educate all individuals in a school or community context about violence and to empower them to speak up, safely intercede, or get help when witnessing abusive, bullying, or sexually coercive conduct by peers (Banyard, Plante, & Moynihan, 2004). Proponents note the potential of the bystander approach to both change social morés by shifting violence-supportive norms within social networks, and to protect individuals by interrupting specific incidents of mistreatment in the moment (Banyard et al., 2004). Emerging evidence supports this premise. College-level bystander programs have increased participants’ self-efficacy for and frequency of intervening in situations that could lead to a sexual assault (Katz & Moore, 2013), and bystander components in antibullying interventions have similarly bolstered proactive bystander behavior among elementary and middle school students (Polanin, Espelage, & Pigott, 2012).

Research related to adolescents’ use of proactive bystander behavior and the efficacy of bystander-based prevention interventions among high school aged youth is sparser than research with college and elementary school populations. The specific developmental needs of adolescents suggest that what works for children and young adults may not easily translate into high school settings. Actively intervening in a peer or stranger’s aggressive or inappropriate behavior is a challenging task even for well-trained adults (Casey & Ohler, 2012), and is an action influenced by a complex array of cognitive, situational, and environmental factors. Tailoring bystander-based bullying and violence prevention programs for adolescents requires a more comprehensive and nuanced understanding of youth-specific bystander decision-making, and the range of influences upon it. The purpose of this study was to elicit influences on bystander behavior in the context of bullying and teen dating violence (TDV) via focus groups with high school aged youth. These influences were integrated into our proposed Situational-Cognitive Model of Adolescent Bystander Behavior, which can be used to inform and refine intervention programs.

Adolescent Bystander Behavior: Relationships Between Bullying and TDV

To date, most bystander-based prevention programs target a single form of aggression, such as sexual assault or bullying. Potential synergy within bystander approaches for addressing a range of problematic behavior is underexplored, particularly among youth, despite considerable evidence that suggests these behaviors are related and overlapping. Perpetrating bullying and physical violence against peers is associated with both current and future perpetration of dating violence (Connolly, Pepler, Craig, & Taradash, 2000; Rothman, Johnson, Azrael, Hall, & Weinberg, 2010), and many forms of bullying, including verbal abuse, threats, and isolating peers are also tactics of TDV. Likewise, many bullying behaviors, such as sexual rumor spreading and sexual harassment, exist on a continuum of behaviors that contribute to a climate in which TDV and sexual aggression become more acceptable (McMahon & Banyard, 2012), rendering bystander responses to the spectrum of these behaviors an important interventive tool. Although perpetration of these acts intersect, little is known about similarities and differences between the factors that affect bystander behavior in the face of bullying versus TDV or whether both could be addressed within single prevention programs. Given both the time and resource constraints faced by schools and other youth settings as well as evidence of overlap between these experiences, it is strategic to examine commonalities in bystander decision making processes across these behaviors.

Integrating Theories of Bystander Behavior

Scholars note that theoretical models describing influences on adolescents’ bystander behavior in the context of TDV or bullying are underdeveloped (e.g., Hawkins, Pepler, & Craig, 2001; Weisz & Black, 2008). To date, conceptualizations of adult sexual and intimate partner violence-related bystander behavior rely heavily on Latané & Darley’s (1969) situational model of bystander behavior (herein referred to as SMB). The SMB identifies intrapersonal processes underlying the decision to take action in a troubling situation, with each decision influenced by the presence of other people (known as the “bystander effect”). Among these processes are (a) noticing that a problem is occurring, (b) interpreting a situation as problematic, (c) seeing oneself as responsible for taking action in that situation, (d) knowing how to intervene and weighing which action to take, and finally, (e) taking action.

Accumulating evidence supports the relevance of these decision points to intervening in bullying, dating abuse, and sexual violence. Adults are less likely to report willingness to intervene in the disrespectful or sexually coercive behavior of a peer if, consistent with the SMB, they do not define a situation as problematic (Burn, 2009), do not see themselves as responsible for taking action (Banyard & Moynihan, 2011), or lack confidence about what to do (Banyard, 2008; Burn, 2009). In a recent study of college students, Bennett and colleagues (2014) found that factors influencing college students’ sexual assault-related intervening behaviors mapped closely onto SMB processes, and included whether or not they felt morally responsible to intervene and the degree of perceived seriousness of the situation. Relative to bullying, Pozzoli and Gini (2013) tested the salience of the three middle phases of the SMB and found that recognizing a problem as serious, feeling responsible to intervene, and possessing the skills to take action were associated with Italian middle school students’ willingness to intervene on behalf of a victim of bullying. Evidence for the predictive utility of component parts of the model to bullying bystander behavior also emerges from several studies; believing that it is not their “place” or responsibility to intervene was cited by Canadian youth as a barrier to defending victims of bullying (Cappadocia, Pepler, Cummings, & Craig, 2012) and confidence in the ability to take action has a demonstrated cross-sectional link to defending behavior among early adolescents in the United States (Barchia & Bussey, 2011). In the only application of the full SMB to adolescents, Nickerson and colleagues (2014) found each stage in the model to sequentially and significantly predict intervention willingness in the context of bullying and sexual harassment among U.S. youth.

Although the SMB is helpful for modeling bystander decision-making, it does not include a broad range of cognitive factors (e.g., attitudes and beliefs) that may also influence bystander behavior (Banyard, 2014; Casey & Ohler, 2012). Evidence from other behavior change research suggests that the Theory of Planned Behavior (hereafter TPB; Ajzen, 1991) is well positioned to capture many of these additional influences. The TPB is an empirically validated and theoretically rigorous social–cognitive model which pinpoints critical cognitive predictors of a range of health behaviors (Montaño & Kasprzyk, 2002). Several scholars have argued for the conceptual relevance of constructs within the TPB to bystander behavior across types of violence (e.g., Banyard, 2014; Banyard, Moynihan, & Crossman, 2009; McMahon et al., 2014; Stueve et al., 2006), and emerging evidence supports the utility of this model and its component constructs for distinguishing between interveners and noninterveners, particularly in the context of bullying (DeSmet et al., 2014).

The TPB posits that behaviors are predicted by individuals’ intentions to engage in those behaviors. These intentions are influenced by three factors. First, intentions are predicted by attitudes toward a specific behavior (defined as affective evaluations of the behavior and possible outcomes of doing the behavior). For example, adults and youth who perceive that intervening results in ridicule or retaliation and assess these as unpleasant outcomes report more passivity in the context of aggression toward women (Casey & Ohler, 2012) and bullying among youth (Thornberg et al., 2012). Second, intentions are influenced by perceived social norms, operationalized as subjective norms, which are perceptions of what important referents want one to do. Indeed, youth are less likely to intervene in bullying (Pozzoli & Gini, 2010; Rigby & Johnson, 2006), and college males are less likely to intervene in potential sexual assaults (Brown & Messman-Moore, 2010) if they believe that their peers would not do the same. Furthermore, for male youth, defending bullying victims is inhibited if bullying behavior is more common or normalized in their peer group (Espelage, Green, & Polanin, 2012). Similarly, youth who believe that teachers expect them to stand up to bullying feel more obligated to do so (Thornberg et al., 2012). The final construct predicting intentions, perceived behavioral control, has considerable overlap with the SMB stage of weighing what to do, and can be considered, essentially, a self-efficacy construct in both models. While the TPB in its entirety has not been applied to bystander behavior in the context of TDV, DeSmet and colleagues (2014) used the theory as an organizing framework to describe influences on Belgian teens’ responses to cyberbullying, and found that its constructs collectively captured a majority of influences on bystander behavior.

The SMB and the TPB have areas of overlap, particularly related to the role of self-efficacy. However, the strengths of each model (namely its respective focus on situational or cognitive processes) also compliment limitations in the other. Integrating these theories, therefore, provides a more comprehensive framework for modeling the range of intrapersonal and situational influences on bystander decision making in the context of bullying and TDV. Synthesizing models may also allow for the identification of both general constructs that are most related to intentions to intervene (e.g., norms vs. attitudes) as well as the specific cognitions within constructs that best distinguish active versus passive bystanders. For example, it may be that all young people’s perceived norms include the belief that their teachers would want them to intervene in disrespectful peer behavior, but that this belief does not differentiate those willing and unwilling to intervene. On the other hand, if beliefs about peer norms consistently differ between youth who do and do not intervene, perceived peer norms become a much more important and specific target of intervention development.

Purpose of This Study

In summary, evidence supports the relevance of both the SMB and the TPB to explaining bystander behavior in the context of bullying and TDV. Despite their individual theoretical potential, these two theories have not been previously integrated within the same research to examine bystander behavior, nor have they been systematically applied to adolescents or in the context of TDV. Further, similarities across types of bystander situations have not been explored, leaving unclear whether bystander decision making works comparably in the context of both bullying and TDV. Generally, applying the full TPB to a new behavior (here, intervening across bullying and TDV) among a particular demographic group (adolescents) requires a qualitative elicitation phase in which the specific, salient content of each of the TPB constructs is surfaced (Montaño & Kasprzyk, 2002). Additionally, because the TPB and SMB have not previously been integrated, the extent to which content within each overlaps and is exhaustive is unclear. This study therefore used a qualitative approach via focus groups with high school-aged youth to elicit both theory-relevant bystander influences and influences not captured by these models, and to inform the development of the Situational-Cognitive Model. Specifically, the aims of the study were (a) to describe the range of specific beliefs and bystander influences that comprise each construct within the SMB and the TPB; (b) to examine the sufficiency of an integrated Situational-Cognitive model for capturing the range of factors related to bystander behavior; and (c) to examine the degree of overlap and divergence between bullying and TDV-specific influences on adolescent bystander behavior.

Method

Overview and Sample

Data were collected through a series of face to face and online focus groups with 113 U.S. adolescents aged 14–18 (mean age = 15.8). Of these, 74 (65.5%) identified as females and 39 (34.5%) as males; 20 (17.7%) reported their race as Black, 2 (1.8%) as American Indian/Native American, 5 (4%) as Asian or Asian American, 16 (14.1%) as Latino/a, 2 (1.8%) as Middle Eastern or “Arab,” 12 (10%) as multiracial, and 56 (49.5%) as White. Participants in online groups represented all major geographic regions of the continental United States. All procedures used in the study were approved by the University of Washington Internal Review Board (IRB).

Procedures

In-person focus groups.

Eight face-to-face focus groups with a total of 53 youth were convened within a specific geographic region. Of these, seven occurred within high schools, and the eighth was conducted at a drop-in and support center for gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender, and queer-identified (GLBTQ) youth. School district approval was obtained for high school-based groups; active parental consent as well as youth assent were secured before youth participated in these groups. In each high school, research staff provided information about the study in several classes selected for their diverse enrollment along dimensions of gender, age, and race or ethnicity. Most high-school based groups occurred in on-campus private spaces directly after school hours; one focus group occurred during a class period.

For the single group conducted at the GLBTQ youth program, parental consent requirements were waived by the IRB in consideration of the youths’ confidentiality. Research staff attended drop-in hours at the center and provided information about the study, eligibility requirements, and focus group location. With the exception of the focus group at the drop-in center, all groups were stratified by age, with 14- to 15-year-old youth and 16- to 18-year-old youth participating in separate groups. Focus group discussions were cofacilitated by two members of the research team, and were digitally recorded and professionally transcribed. Resulting transcripts were then rechecked for accuracy. Focus groups lasted approximately 90 min. Participants were provided with a $25 gift card in recognition for their time.

Online focus groups.

We contracted with the online focus group company InsideHeads to convene and facilitate four real-time online focus groups with 60 youth who participated from across the United States. InsideHeads staff recruited participants through their large, diverse, standing panel of adult research volunteers. Panel members with adolescent children were contacted via email and asked for consent to approach their children about participation in the study. Youth with consenting parents were invited via email. Phone checks with prospective participants were conducted to verify youth’s identity and age. At the designated time, focus group participants logged into the discussion and participated anonymously via chat, with an InsideHeads staff person facilitating the discussion. Research staff “observed” the group, and provided real-time guidance to the facilitator during the discussion. These groups resulted in transcripts of participants’ comments. Online focus groups also lasted for 90 min, and participants were provided with a $50 gift card in accordance with InsideHeads reimbursement policy.

Measures

For both in-person and online groups, we used a semistructured interview guide to elicit participants’ perceptions of influences on bystander behavior. After a period of warm-up conversation and introductions, we began by providing a brief definition of TDV and bullying, and then soliciting examples of bullying and dating violence behaviors (that could also include sexually aggressive behaviors) and victimization situations perceived as common by the youth. Youth were asked not to disclose personal experiences of bullying or violence, but to describe situations and perspectives they viewed as normative among their peers. We then selected at least one bullying example and one dating violence example mentioned by the group for in-depth exploration from the perspective of a bystander. Selected examples were unique to each group, and were chosen because they generated the most recognition and discussion within each group. Examples of scenarios discussed by the participants included sexual rumors being spread about a girl via social media, and a young man yelling at and physically intimidating his girlfriend at school. For each scenario, questions designed to elicit content specific to SMB and TPB constructs were asked, in addition to general questions aimed at surfacing a wide range of ideas about the factors that influence bystander behavior. Example questions included, “What do you think would happen in this situation (good or bad) if you decided to intervene? (TPB-attitudes); “Whose opinions matter most to you when deciding whether to intervene? (TPB- norms); “What would make it easier to intervene in this situation? Harder?” (SMB/TPB-Self-Efficacy); and “How would you decide whether to intervene?” (general influences). A full list of questions is available upon request from the lead author.

Data Analysis

Data management and extraction were accomplished using the qualitative software program Dedoose (version 5.1.26). To evaluate our first research question, we used a deductive coding scheme (Miles, Huberman, & Saldaña, 2014) for theoretical constructs from the SMB (defining a situation as a problem, assuming responsibility to act) and the TPB (attitudes toward intervening, subjective norms) and self-efficacy, a construct shared by both theories. Each transcript was read by the entire research team. At the beginning of data analysis, four transcripts were coded for general theory constructs (theory codes) by each team member, and theory codes were compared across transcripts to identify any statements that were differentially coded by a team member. After the theory coding scheme was finalized, one research member served as the primary coder on the remaining transcripts, and the first author read and reviewed each transcript after it was coded to ensure consistency across coders and transcripts. Once all the transcripts were coded for theory constructs, we extracted the content for each construct separately and inductively created new subcodes to reflect beliefs and ideas that participants noted as comprising each larger theory code—these could be shared across a number of participants or only mentioned by one. The first subcoding was done by the first author; all subcodes were rechecked against the data by the second author.

To analyze our second research question regarding the sufficiency of SMB and TPB constructs for explaining bystander behavior, we inductively coded statements the youth made about factors that influence their decisions to intercede that were not already reflected in the SMB or TPB. These inductive codes were generated by a primary coder for each transcript, and were then reviewed in research team meetings. For our third research question about the similarities and differences in bystander behavior across bullying and TDV, we coded entire sections of the transcripts that were focused on bullying or on TDV, and then noted those places where these topics overlapped. We then compared the presence of specific codes and subcodes within text coded as being about bullying, TDV, or both.

Results

Focus group discussions elicited a wide range of examples of bullying and TDV-related bystander behaviors that youth might use in response to an incident. Examples included ignoring the perpetrator, interrupting behavior in the moment, speaking with a perpetrator or target later, or enlisting adult support. Because influences on bystander decision making are the focus of this analysis, we do not include an in-depth discussion of youth’s descriptions of what behaviors constitute bullying and TDV, or the range of intervening responses they might use. What follows is a construct by construct description of the specific themes related to bystander decision-making that surfaced within each component of the SMB and the TPB, followed by additional factors not captured by these theories. Within each construct, we analyze the appearance of the subthemes across bullying and TDV. We end by describing a model that integrates each of the areas discussed by participants in relation to bystander behavior.

Situational Model of Bystander Behavior and Theory of Planned Behavior Constructs

Table 1 provides an overview of the constructs from the SMB, TPB, and the additional factors that are relevant to bystander behavior. Each construct is defined, and then subthemes that were facilitators or barriers to bystander intervention are listed. Themes that were specifically related to either bullying or TDV are italicized with parenthetical notes about which form of violence was addressed.

Table 1.

Theory Constructs and Subthemes

| Construct | Definition | Facilitators of intervening | Barriers to intervening |

|---|---|---|---|

| Defining a situation as a problem (SMB) | Factors associated with interpreting a situation as potentially requiring an intervention | Negative impact on victim Repeated behavior Victim is vulnerable (B) Female victim (TDV) Physical abuse (TDV) |

Behavior perceived as mutual or as “drama” |

| Assuming responsibility (SMB) | Factors associated with seeing oneself as personally responsible for intervening | Moral or ethical duty Putting self in victim’s shoes (B) |

Not my problem or business An adult should handle this |

| Attitudes toward intervening (TPB) | Beliefs about the behavior and potential outcomes of the behavior, and the affective evaluation of these outcomes as positive or negative | Intervening could help Interveners have self-respect |

Intervening is pointless Interveners risk their safety Interveners are busybodies Interveners risk the victim’s safety (TDV) Interveners get targeted next (B) Interveners are snitches or disloyal (B) Interveners ruin others’ fun (B) Interveners are goody-2-shoes (B) Interveners get in trouble (B) |

| Subjective norms about intervening (TPB) | Perceptions of what important referents want an individual to do, or would do themselves | Parents want us to do the right thing Victim may want intervention Peers would support always or usually intervening School personnel want us to intervene |

Parents want us to be safe Victim may not want intervention Peers never step up and would disapprove Silent majority or peers give lip service to intervening |

| Self-efficacy/perceived behavioral control (SMB/TPB) | Perceptions of accessibility of the behavior, or factors that make it easier or harder | Training would help Confidence and courage (B) Back up from peers and adults (B) |

Lack of knowledge about what to do Differentiating arguments from abuse (TDV) |

Note. Influences that are specific to bullying (B) or teen dating violence (TDV) are shown in italics.

Defining a Situation as a Problem (SMB)

We identified six elements of peer interactions that youth see as characterizing “serious” bullying or relationship abuse that warrants intervention. Three characteristics were consistent across both TDV and bullying; the reaction and perceived distress level of the victim; repeated aggression, and the degree of perceived mutuality. As an example of evaluating distress level, a younger female in an online group suggested that she would view a situation as problematic, “especially if I could see in his face how they were making him feel sad.” Noting that repeated behavior is more problematic and serious, a younger male in an online group stated, “I might let it go by a couple of times but if it keeps up and gets the guy [bullying victim] upset I would say something.” Similarly, many youth noted that repetition elevates fighting or mistreatment in a dating relationship from conflict or “drama” to abuse. On the other hand, feeling that mistreatment was mutual or that it constituted reciprocal drama (arguing, attention-seeking, or attempts to enlist others’ support to win an argument) between friends or partners constituted a barrier to viewing incidents of either bullying or TDV as serious.

The remaining “seriousness” criteria were more specific to either bullying or TDV. For bullying, perceived vulnerability of the victim increased the apparent seriousness of peer-to-peer mistreatment. Vulnerability was equated to disability, size, or age of the victim. For TDV, on the other hand, youth reported that incidents met the threshold of needing outside intervention when (a) the victim is female, and (b) the behavior is physical. Many youth, including the following young man from an in-person group, noted the perception that violence directed toward a female victim requires immediate intervention, but not necessarily the opposite:

I think the difference is when the girl hits the guy you think well, she shouldn’t have done that but it’s not my business, they’re a couple, whatever, let them deal with it. When the guy hits the girl, that’s when everyone would jump up because that—because the guy, usually guys are bigger and stronger than girls so when you’re intimidating them immediately that’s usually too far for everyone.

Finally, participants tended to identify physical abuse as the threshold for bystander intervention in TDV, minimizing the impact of verbal or emotional abuse. The following online exchange among younger students took place in response to a question about when to intervene in TDV, “Male: ‘If he touches her.’ Female: ‘If something physical happens, it’s time to jump in.’”

Responsibility (SMB)

Many youth in the focus groups reported feeling responsible to intervene and wanting to intervene, but simultaneously feeling unable or ill-equipped to do so. Taking “responsibility” may be an important, but insufficient precursor to intervention, tied to self efficacy and to the perceived negative outcomes of intervening described below. One older female student in an online group communicated this notion: “I think that most people … they want to [intervene]. Who would not want to help? You see someone hurt, you want to help. But I think people are scared and just don’t know how to go about doing it.”

Four specific facilitators and barriers related to assuming personal responsibility for intervening emerged throughout the focus groups, and these dimensions of responsibility largely applied to both TDV and bullying. The two most commonly discussed dimensions of responsibility were in contrast with one another. First, some youth described an overarching, moral sense of responsibility to try to help that emerged from a fundamental belief that any mistreatment is wrong and should be confronted. Generally, youth attributed this to personal characteristics, upbringing, or an individual code to “do the right thing.” For example, a younger male in an online group noted, “Seems I tend to always get involved. I can’t sit by and watch. It’s the way I was raised.” A more prevalent, second, view, however, was that unless a youth is directly involved, or knows the individuals involved in an incident of bullying or abuse, there is no responsibility to intervene and further, that it is unwise to do so. The notion that incidents are “none of my business” arose frequently for both bullying and TDV. Speaking about bullying that did not directly affect her, a younger female in an online group noted a common sentiment; “I would say nothing, just keep to myself, because it is no biz of mine.” Specific to TDV, an older female in an in-person group articulated the belief that relationship dynamics are private, and not subject to outside judgment:

Well, it’s their relationship. It’s not really my business. Even if they’re your friends, [they] kind of tell you that they want you to stay out of a relationship and I feel that way too. When I’m in a relationship, I don’t want my friends sitting there nitpicking everything that we do and judging us. So, people think, it’s their relationship, it’s not my business. That’s how they do things, and [this] is how we do things.

Next, across both TDV and bullying, some youth (particularly younger students) reported believing that adults and not youth should step in. The last facilitator of responsibility applied to bullying. Some youth reported placing themselves in a bullying target’s shoes as a way of seeing their own responsibility to take action. For some, this came from personal experiences as a target of harassment, including the younger male (online) who noted, “every time I see bullying I stop it because I know what it’s like.” Others reported pondering how they would feel if they knew they could have taken responsibility for protecting someone, but failed to do so.

Attitudes (TPB)

In the context of the TPB, attitudes are operationalized as individuals’ beliefs about the potential outcomes of a specific behavior, coupled with their emotional evaluations of those outcomes. Of the constructs within the integrated model, attitudes contained the largest number and most nuanced set of specific subthemes, with a total of 11. On the whole, youths’ perceptions of possible outcomes of taking some kind of action were largely pessimistic, and their evaluations of these outcomes were negative.

Three attitudes that were barriers to intervening characterized both bullying and situations involving TDV. First, youth expressed the belief that intervening in TDV or bullying is pointless or ineffective, can invite additional difficulty into the intervener’s life, and/or can escalate the situation and make things worse for everyone. For TDV, in particular, many youth expressed the belief that victims would not be open to hearing an intervener’s concerns, that the victim would feel pressured to close ranks with their abusive partner, or that the intervention would backfire. “When you get involved you end up losing your friend and he/she just goes back to the dating partner,” noted one older male in an online group. Second, youth worried about their physical safety. A younger female student in an online focus group quipped, “I don’t want to come home with a black eye,” while a younger female in an in-person group cited the perception of a gang presence at her school as a safety barrier; “There are a lot of gangs at our school so it’s like most of the people that are bullies are in gangs so it’s like you don’t really want to say anything because it’s really scary.” Finally, several youth held the belief that people who intervene will be perceived by others as nosy and not minding their own business.

Two attitudes facilitative of intervening in both TDV and bullying emerged. First, in contrast to the above belief that intervening is ineffective, some youth felt that taking action could diffuse a situation, make things better for a target, or support a perpetrator in reflecting on his or her actions. As will be described below, this attitude was largely connected to situations in which youth knew the target or perpetrator—youth were more pessimistic about the effectiveness of intervening in situations involving nonfriends. Second, youth noted self-respect as a positive, possible outcome of intervening. One older female in an in-person group stated:

I don’t think it ever gets easier to take the risk and try and do the right thing. But if you do take the risk to try and help then you’ll feel more rewarded as a person. It’s not like being rewarded like by the school or by your peers but being better with yourself.

Six additional inhibiting attitudes more specific to bullying or TDV emerged. First, in the context of TDV, some youth noted that intervening could put a target of dating abuse in greater physical danger. The remaining inhibitors were relevant to bullying. Primary among these was the idea that interveners run the risk of becoming targets of harassment and bullying themselves. Youth expressed the concern that the students perpetrating bullying (or even those victimized by it) would turn on the intervener, or would associate the intervener with the bullied target, thereby lowering the intervener’s status and increasing his or her vulnerability. One younger male in an online group lamented that if he intervened, “I would be outcasted [sic] for as long as the situation lasted and even beyond that. I’d be the butt of some jokes about it.”

The second most common concern was the attitude that interveners are viewed as “snitches” who are thereafter labeled “untrustworthy” and socially excluded. Some youth noted that the high school context, which can be characterized by strong social pressure and over which students have little control, renders “snitch” an especially pernicious and persistent label. An older student in an in-person group described the consequences of being seen as disloyal or untrustworthy in this way, “Now you’re just looking at someone [the intervener] who is, basically, an intruder, and it’s just like, ‘okay, well, you’re done now.’ No one wants to talk to you.”

The final, less common, attitudes inhibiting intervening in bullying included (a) the belief that interrupting an instance of teasing or fighting is tantamount to interrupting others’ entertainment and spoiling students’ fun, (b) that interveners are “weird,” square or “goody-2-shoes,” and (c) that proactively taking action could result in the intervener being mistaken for part of the problem. This latter attitude emerged primarily in a specific school context with a no-tolerance policy toward fighting that included consequences for being present at an incident. Although the school policy was specific to fighting, youth in the focus group generalized its application to any kind of helping. As one older female student noted:

At school, people don’t want to get in trouble, especially, if you’re trying to help somebody. Because even helping them, the school basically says, ‘oh, you were in it.’ You, basically, were in the fight and you get suspended for it too. And - that’s just completely outrageous because even if you really, truly were trying to help, [the school would] probably suspend you, anyways, for jumping in and doing it.

Social Norms (TPB)

In the context of the TPB, social norms are operationalized as young people’s perceptions of what their important referents would want them to do, or would do themselves. Across TDV and bullying, four important referents were mentioned—peers, school staff, parents, and the target in an incident. Only parents and the victim in a situation were identified as important referents relatively equally in the context of both bullying and TDV. Most youth who mentioned parents perceived that their parents would want them to “do the right thing” and help a target of bullying or TDV, although a few youth noted that their parents would also want them to be careful, and not jeopardize their physical safety. Perceptions of the target’s expectations might serve as either a facilitator or inhibitor of action and were situation-specific; some youth reported the perception that targets feel judged by outside intervention or want others to mind their own business and avoid making things worse. Others noted the possibility that a target would request assistance. One younger male in an online group noted that the target of bullying would be his guide in deciding what to do: “If they don’t want help, then I wouldn’t assist. But if they are unable to protect/stand up for themselves, I would intervene.”

School staff and peers were discussed as social norm referents primarily in the context of bullying. Perceptions of what school staff want bystanders to do was relatively uniform; youth reported getting messages supportive of intervening in bullying from school staff. “If you see something, say something,” largely characterized participants’ perceptions of the expectations of adults at school, but some youth noted that this command is an oversimplification of the act of intervening, and generally minimized the extent to which this motivated their own decisions. In contrast, peers were both the most discussed referents, and also the referents for whom there was the most variability in perceived norms. Beliefs about what peers would think, or would do themselves constituted a spectrum of perceived norms. On one extreme, a few youth felt that their peer contexts were characterized by mutual support and an expectation of always intervening on behalf of a targeted peer. For example, attributing this norm to the climate of her peer group and even her school more generally, one older female in an in-person group noted that harassment based on sexual orientation or identity would always be met with a response:

Our school has a strong base on identity type of things. If you are any variation of LGBT, you have a strong support base at my school. … And there are, of course, going to be people who are not okay with it. And they’re going to say things from time to time. But you have all these other people who will stand behind you.

In the middle of the peer norm spectrum was the notion of a “silent majority,” in which youth perceived that their peers dislike bullying and believe someone should intervene, but remain silent out of fear or uncertainty and would not speak up to back another intervener—thus keeping other youth similarly passive. One older female online participant stated, “Honestly, it is not very likely [that peers would actually intervene]. People think they have no influence or control.” A slightly more inhibiting version of this norm was the notion of “lip service.” Some youth perceived that their friends and peers know to verbalize that bullying is wrong, but still tacitly condone it, view it as entertaining, and/or would not encourage others to intervene. “They SAY it is bad. But everyone does [bullies],” noted a female online participant.

Finally, a few youth felt that the prevailing norms among their peers more overtly tolerated or even condoned mistreatment of some students, and perceived that “normative” behavior in the face of bullying was to allow it to continue, to join in, but not to disrupt the behavior by intervening. A younger female in an online group felt this applied to her peers at school: “Usually when someone bullies another person, the other people join in, laugh, or just don’t do anything about it because they don’t want to get involved.” Another younger female participant in an online group aptly summarized the influence of perceived peer norms: “You end up torn between the right thing to do and how your peers look at you.”

Perceived Behavioral Control/Self-Efficacy (SMB/TPB)

Youth identified four ideas related to whether they feel competent to intervene, or to what would increase their intervening self-efficacy; two were relevant to both bullying and TDV. Perceiving that they lack the skills or knowledge to intervene was the most commonly mentioned theme salient to self-efficacy. “I don’t know what to do,” was a phrase heard across all focus groups. Reflecting on an instance of witnessing abuse outside her school, one older female student in an in-person group stated,

I’ve seen that situation … occur, but I was only a freshman. I was walking to class. And– I didn’t know these people at all. And I was like—I don’t know how to react to this. And like it wasn’t around for everyone to hear. … But I was like I don’t know. I told a teacher, I was like ‘so these people are outside yelling,’ … And then I just kind of went on with my business because I don’t—I don’t know.

Exemplified in this quote is also the interplay of influences in this youth’s response to what she saw. Her self-efficacy is not only impacted by feeling uncertain about what to do, but also by her perceived lower status because of her age, and because of her (non)-relationship to the parties involved. Although she does take some action by telling an adult, her words imply that she felt this was insufficient, and that she ultimately “went on with her business.”

At times, youth related their lack of confidence not to their ability to launch an initial intervention, but to their fear about navigating the ongoing repercussions of having taken some form of action. Youth pointed out that intervening or enlisting adult help was not a one-time only interaction, but could set in motion a larger series of events that they lacked the skills to negotiate in an ongoing way. For example, noting that he feels unprepared to handle the unpredictability of a reaction to an intervention, one young man in an in-person group stated that there should be

… more preparation for that person that would intervene. Because I know if I see someone arguing and I tried to defend the person, and the person that’s the victim would lash back at me, I would be like, ‘oh crap. I’m not doing this anymore.’

Nervousness about competence to intervene was also related to youths’ aforementioned outcome beliefs. Young people foresaw a range of negative possible outcomes from intervening and their confidence in negotiating the social consequences of these outcomes was low.

The second self-efficacy related theme relevant to both bullying and TDV was an expressed need for additional training about these issues. Particularly in the context of TDV, young people felt uncertain about how to distinguish between couples’ arguments and dating abuse, and then how to safely take action. Youth reported that they had received information about bullying, but that they still lacked more nuanced skills relevant to selecting an appropriate way to respond to an incident, and then to competently handle subsequent reactions.

Two factors related to self-efficacy were mentioned mostly in the context of bullying. First, a handful of youth reported that they regularly intervene in peer-to-peer mistreatment, and feel confident doing so. Similar to notions of responsibility, these participants attributed this sense of self-efficacy to personal characteristics such as courage or a lack of concern with others’ opinions. An older female student in an in-person group noted, “I’m kind of a problem-solver,” while a younger female in an online group quipped, “I’m not afraid of being made fun of by stupid self-centered girls at my school.” Some of these youth acknowledged that their age, grade level, or status at school allowed them to take action in a way that would be respected. Second, youth reported that they feel more confident to intervene when they knew that peers will back them up or step forward, or that they could count on adults to provide support.

Additional Critical Influences on Bystander Behavior

Three important categories of bystander behavior influences emerged that are not well reflected within SMB/TPB constructs. These included target or perpetrator, group affiliation, and school climate factors. We describe the first two of these factors in some depth here. Young people’s perceptions of school-level contributors to inhibiting or facilitating bystander behavior (a complex and nuanced set of dynamics in its own right) will be addressed in a separate article. Generally, target or perpetrator factors and group affiliation factors were consistently mentioned in concert with the specific beliefs and perceptions comprising the theory-related constructs described above, and seemed to make either facilitating beliefs or inhibiting beliefs more salient in a given situation. For example, having a close relationship with the victim or perpetrator was discussed in concert with facilitating factors from the SMB or TPB, such as feeling responsible to intervene, having optimism about the outcome of intervening, and feeling able to muster an appropriate response. The opposite was also seen—not knowing the involved parties well, or occupying a lower social status than others (a group affiliation factor), often coincided with perceived social norms for nonintervention, and pessimism about the success of taking action. Target or perpetrator identity, and group affiliation factors acted as critical precursors, triggering specific sets of outcome, normative, and self-efficacy beliefs which either strongly favored nonaction, or conversely, getting involved.

Target or Perpetrator Factors

Three influences specific to the victim or perpetrator identity surfaced, all applicable across bullying and TDV (Table 2). First, youth in all focus groups resoundingly felt more inclined to intervene if they knew the parties involved in a situation, and particularly if they had a close relationship with one of them (especially the target). Knowing the target or perpetrator coincided with facilitating attitudes, norms, and self-efficacy beliefs, as suggested by an older female student in an in-person group: “Because if I don’t know them, then if I’m, ‘well stop bullying,’ I don’t think they’re gonna take me serious. I think if I knew them, and they were like my friends and I was like, ‘you guys, that’s mean,’ then they might stop.” Second, status relative to the victim or perpetrator was cited as a barrier to intervening, with many youth noting that if the person doing the bullying or abuse is older, in a higher grade, or “popular,” trying to intervene with that person is unwise and likely to fail.

Table 2.

Relationship and Situational Factors and Subthemes

| Construct | Definition | Facilitators to intervening | Barriers to intervening |

|---|---|---|---|

| Target or perpetrator factors | Factors associated with the identity, perceptions of or relationship with the victim or perpetrator in a situation | Close relationship with target or perpetrator | Lower status than target or perpetrator Perceived victim culpability |

| Group affiliation factors | Factors associated with the identity of others present at an incident, or with peer group affiliation | Bystander’s peer group is present or involved (B) |

Lower status than others present at an incident (B) Maintaining status of bystander’s social group (B) |

Note. Influences that are specific to bullying (B) or teen dating violence (TDV) are shown in italics.

Finally, participants’ discussions suggested that the youth struggled with the degree to which a target of bullying or TDV was complicit in their own mistreatment, and that perceived victim culpability played a role in subsequent attitudes toward intervening. For example, in the realm of bullying some youth reported feeling uncertain about intervening on behalf of someone who is “douchy” (obnoxious or gross), attention-seeking, or who is rumored to have multiple sexual partners, as evidenced by this older female student’s statement in an in-person group:

Like some people at this school—I’m not calling people sluts, but they had a lot of sexual partners and stuff. And the reason like I don’t intervene, it’s not like I agree with them calling them a slut but it’s like I … Because, sometimes I do intervene and they’re like, ‘oh you know it’s true,’ then I don’t know what to say after that.

For some youth, perceptions of target culpability and/or outright victim-blaming prevented them from believing that a target of bulling or TDV was deserving of outside intervention. In the context of TDV, “culpability” might include staying with a disrespectful partner or being the victim of verbal abuse, which some youth perceived should motivate victims to leave their partners. An older female student’s statement in an in-person group reflected this sentiment:

… it’s her fault for putting up with it for that long and feeling like [she] deserves it. I know a lot of girls feel they’re trapped, [but] there’s so many worse situations in the world where people are suffering and, you’re just, putting up with it.

Group Affiliation and Status

The final set of influences centered on the bystander’s larger social affiliations and the status of those affiliations. These factors surfaced primarily in the context of bullying, and were all connected in nuanced ways to both young people’s need to maintain status within their social groups, and to maintain the status of the social groups as a whole. Youth noted that they would be more likely to intervene if members of their social group were present at an incident or affected by it, as a way of standing up for the group. Similar to knowing the target or perpetrator, affiliation with the group involved seemed to trigger more optimistic assessments of the potential outcomes of and level of support for intervening. Being a member of a lower status group in the school, however, was a barrier to intervening, as was the perceived role of the mistreatment of others in establishing the status hierarchy within a group. In social contexts in which status can be gained by teasing, or in which intervening in bullying is perceived as being uncool, proactive bystander behavior is inhibited. One younger female in an in-person group lamented,

Or, you’re not already popular, like you hang out with some popular kids and so you’re kinda just doing what they do … you may not like it but it’s a way for you to, you know, step up in social status and so they’re just like, well I’m not gonna do anything ‘cause if I do something then they’re gonna not wanna be friends with me and I’m just gonna have to go sit by myself at that table again—by myself.

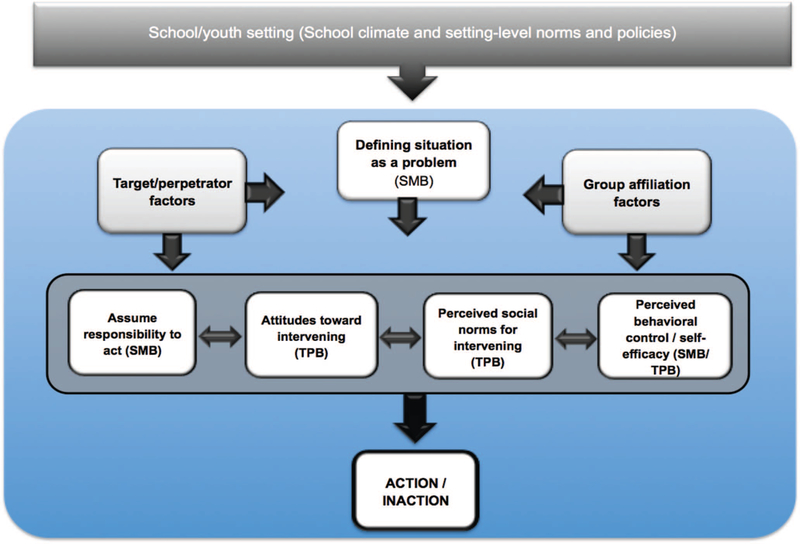

The Situational-Cognitive Model of Adolescent Bystander Behavior

Figure 1 displays the proposed relationships between the aforementioned theoretical constructs in the integrated, Situational-Cognitive Model. Intrapersonal elements of the SMB and TPB, along with target or perpetrator and group affiliation factors are depicted inside the shaded box; this indicates the relevance of these factors to prevention interventions aimed at individual attitudinal and behavioral change. Factors at the school level that affect youth bystander behavior are noted outside of the shaded box. While also targets of intervention, and mutually related to intrapersonal bystander decision-making factors, issues of school climate are addressed in a separate article and require an additional programmatic focus. We posit that perceiving an incident as serious and intervention-worthy (an SMB construct), coupled with victim or perpetrator and observer group factors, precede the triggering of particular intervening-related attitudes, perceived norms, self-efficacy beliefs, and sense of responsibility for taking action. More specifically, facilitating target or perpetrator and social affiliation factors such as knowing the individuals involved, are more likely to trigger facilitating attitudes, norms, and responsibility and self-efficacy beliefs (and vice versa). These latter factors, all constructs from the SMB and TPB are further interrelated. As originally conceptualized, the SMB and TPB contain linear, causally organized constructs that affect behavior. However, in the context of bystander behavior, youth described these constructs as reciprocal and simultaneous influences on their decision-making. Assuming responsibility, for example, may both impact and be affected by an individual’s outcome beliefs about a particular situation (attitudes) and perceived self-efficacy to successfully take action in that moment. Collectively, the balance of facilitating versus inhibiting influences within SMB and TPB constructs is then subsequently related to a young person’s willingness or ability to act.

Figure 1.

Situational-cognitive model of adolescent bystander behavior. See the online article for the color version of this figure.

Discussion

Bystander influences emerging from the focus groups support the use of the Situational-Cognitive Model as a helpful conceptual tool for capturing and categorizing factors pertaining to bystander decision-making. Consistent with aim one of the study, youth reported nuanced content within the SMB/TPB constructs of situational seriousness, their perception of responsibility, and their attitudes, norms and self-efficacy beliefs relative to intervening. Relative to the second research aim, three additional factors not well captured by the original SMB or TPB also surfaced and were added to the model; these included youths’ relationship with the target or perpetrator, their status and affinity with other groups at school, and the larger climate of the school. Across all of these categories of bystander behavior influences, a majority of factors were relevant to bystander decision making in the context of both TDV and bullying, with unique factors pertaining primarily to bullying. Most striking was the overall higher proportion of barriers compared to facilitators of taking action. Overall, youth were reluctant and pessimistic about intervening in either TDV or bullying, and described a complex social environment that renders intervening unrewarding and risky. In the sections that follow we identify limitations to the study that affect the interpretation of results, as well as both research and practice implications emanating from these findings.

Limitations

Limitations of the study include potential bias emerging from participant self-selection and the fact that youth who could secure parental consent to participate may be systematically different than youth who could not. Female-identified youth are also overrepresented in the sample. Two limitations emerge from the focus group methodology used here. First, while focus groups allow for cross-germination between participants, they also limit the extent to which individual agreement regarding all content expressed during groups can be assessed. Second, the different modalities used in this study generated unique and compensatory strengths and limitations. In-person groups allowed for depth of exploration, but also carried the risk that more talkative members would determine what content was surfaced. In contrast, online groups were less subject to reporting bias as all members responded to prompts simultaneously, but responses were in less depth. Facilitators attempted to mitigate these issues through deepening probes and check-ins during both in-person and online groups.

Research Implications

Constructs from the original SMB and TPB were useful for capturing and organizing a substantial portion of factors at play in youth’s bystander decision-making. While some of the content within these theories’ constructs emerged through questions specifically designed to operationalize the models, most emerged organically throughout the focus group discussions rather than in response to specific questions. Content identified within the theoretical constructs also both reinforced and added to previous research. As a whole, findings support the work of scholars who have applied either the SMB (e.g., Pozzoli & Gini, 2013) or the TPB (e.g., DeSmet et al., 2014) to understanding bystander behavior in the context of bullying. Further, content surfaced within specific theory constructs was consistent with prior studies of bystander decision making. Similar to previous research, youth reported that a lack of confidence in their skills to intervene or to negotiate the fall-out from intervening (Cappadocia et al., 2012), perceptions of what peers would approve of (Rigby & Johnson, 2006), and fears of social consequences or retaliation (Thornberg et al., 2012) constituted barriers to taking action. Similarly, the strong role of youths’ relationship to the victim or perpetrator in catalyzing or inhibiting bystander willingness echoes previous research on intervening in bullying (Bellmore, Ma, You, & Hughes, 2012). On the other hand, beliefs within SMB/TPB constructs such as the potential role of parents’ messaging (norms), the belief that intervening actually makes things worse for everyone (attitudes), and the role of self-respect and integrity as motivators for intervening (attitudes), were examples of bystander influences that are less illuminated in previous studies. Collectively, this nuanced content within the SMB/TPB constructs reinforces the utility of the integrated theoretical model proposed here, but also the importance of further investigating the full range of beliefs embedded within the content of each component of both models.

Eliciting the content within model constructs is one step toward building the Situational-Cognitive Model of bystander behavior. Additional work is needed to test the relative contribution of the model’s constructs as a whole (e.g., whether norms, attitudes, or self-efficacy are more powerful drivers of intervening behavior) as well as the relative salience of specific beliefs within each individual construct. For example, it may be that “interveners are snitches” and “interveners have self-respect” are both salient attitudes regarding bystander behavior for youth, but that one has more power relative to decision making than the other, either generally, or in particular situational contexts. Further, while focus groups tended to surface bystander behavior considerations as simultaneous and reciprocally influential, it may be that, consistent with the more linear conceptualizations of the SMB and TPB, these constructs actually have a more temporal ordering within the bystander decision-making process. Finally, although many of the barriers and facilitators to intervening were similar across TDV and bullying, their relative salience or causal interrelationships may be different across these two types of aggression. For example, concerns about social status may be more salient to bystander decision-making in the context of bullying, while perceptions of victim culpability may be more influential in the context of TDV. All of these questions lend themselves to quantitative tests of the integrated model.

Clinical and Policy Implications

The bystander considerations articulated by youth reinforce scholars’ contention that bystander decision-making is complex and influenced by a range of intrapersonal, social, and situational factors (Banyard, 2014; Casey & Ohler, 2012). Overall, youth identified more barriers to than facilitators of bystander behavior, and many of the most commonly endorsed influences were barriers. This suggests that for adolescents, the prospect of intervening in peer behavior is laden with real social (and sometimes physical) risks that are rendered all the more important because young people are embedded in particular school contexts that they cannot control or escape. For youth in high school, then, intervening is not a decision about a single moment, but a decision about whether and how to navigate the positive and negative social consequences of taking action that continue to unfold over time. Our participants’ disclosures suggest that asking youth to serve as bystanders within the context of both bullying and TDV is a weighty request. Bystander-based prevention programs for bullying and TDV, therefore, need to explicitly acknowledge and address very real social and status dilemmas, as the youth themselves understand and experience them. Intervention programming may also benefit from using the list of beliefs surfaced in this study to help youth identify a wide range of feasible and accessible options for responding to disrespectful peer behavior, as well as build the complex skills to both handle the succeeding fallout, and to identify situations in which getting involved may not, in fact, be an emotionally, socially, or physically safe option. The nearly universal mention of feeling uncertain about what to do in the face of bullying or TDV also underscores the need for skill practice across a range of scenarios, using a variety of possible bystander responses.

The considerable similarity in influences on intervening behavior in the context of bullying versus TDV suggests that single, comprehensive interventions may bolster positive bystander behavior across these issues. This is particularly true if bullying is included as a focus, as several bystander influences were specific to bullying. Still, the fact that participants had some difficulty sorting out serious peer mistreatment and behavior that constituted intervention-worthy bullying or TDV suggests that interventions should incorporate methods of assessing the relative seriousness of difficult interactions in addition to basic information on the nature, dynamics, and behaviors associated with these problems.

Finally, the complexity of bystander behavior influences identified by youth indicates the need to assess setting-specific pressures on teen’s attitudes, beliefs, and self-efficacy related to intervening behavior. The particular role of, for example, status, perceived peer norms, or concerns about being viewed as disloyal or a snitch is likely to vary between settings, implying that bystander intervention programs need to accommodate the real, on-the-ground, concerns of youth in a particular school. This also shifts the focus to the larger school context, climate, and policies. While understanding school-level influences on bystander behavior is a topic we will address in a separate article, it is clear that the attitudes and beliefs about intervening identified here were nonetheless inextricably linked to the peer and school contexts in which youth were embedded. For example, punitive school discipline policies, a perceived gang presence, and for one young woman, a school-wide norm of always sticking up for each other, trickled into adolescents’ assessments of the feasibility and costs of intervening. Scholars (e.g., Banyard, 2014) have noted the importance of using an ecological perspective to understand influences on bystander behavior, and of attending to broader dynamics within social networks, schools, and communities that may bolster or undermine individuals’ ability to take action. Ultimately, enhancing collective efficacy or willingness to intervene on behalf of peers in the context of school communities requires an in-depth understanding of the particular supports and barriers to intervening that exist at multiple levels in each unique location.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the University of Washington Royalty Research Fund to Erin A. Casey. The authors would also like to extend their sincere gratitude to Lisa Foote and Claire Andrefsky for their assistance with the project.

Contributor Information

Erin A. Casey, University of Washington, Tacoma

Taryn Lindhorst, University of Washington, Seattle.

Heather L. Storer, Tulane University

References

- Ajzen I (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50, 179–211. 10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Banyard VL (2008). Measurement and correlates of prosocial bystander behavior: The case of interpersonal violence. Violence and Victims, 23, 83–97. 10.1891/0886-6708.23.1.83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banyard VL (2014). Improving college campus-based prevention of violence against women: A strategic plan for research built on multipronged practices and policies. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 15, 339–351. 10.1177/1524838014521027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banyard VL, & Moynihan MM (2011). Variation in bystander behavior related to sexual and intimate partner violence prevention: Correlates in a sample of college students. Psychology of Violence, 1, 287–301. 10.1037/a0023544 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Banyard VL, Moynihan MM, & Crossman MT (2009). Reducing sexual violence on campus: The role of student leaders as empowered bystanders. Journal of College Student Development, 50, 446–457. [Google Scholar]

- Banyard VL, Plante EG, & Moynihan MM (2004). Bystander education: Bringing a broader community perspective to sexual violence prevention. Journal of Community Psychology, 32, 61–79. 10.1002/jcop.10078 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barchia K, & Bussey K (2011). Predictors of student defenders of peer aggression victims: Empathy and social cognitive factors. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 35, 289–297. 10.1177/0165025410396746 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bellmore A, Ma TL, You JI, & Hughes M (2012). A two-method investigation of early adolescents’ responses upon witnessing peer victimization in school. Journal of Adolescence, 35, 1265–1276. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett S, Banyard VL, & Garnhart L (2014). To act or not to act, that is the question? Barriers and facilitators of bystander intervention. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 29, 476–496. 10.1177/0886260513505210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown AL, & Messman-Moore TL (2010). Personal and perceived peer attitudes supporting sexual aggression as predictors of male college students’ willingness to intervene against sexual aggression. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 25, 503–517. 10.1177/0886260509334400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burn S (2009). A situational model of sexual assault prevention through bystander intervention. Sex Roles, 60, 779–792. 10.1007/s11199-008-9581-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cappadocia MC, Pepler D, Cummings JG, & Craig W (2012). Individual motivations and characteristics associated with bystander intervention during bullying episodes. Canadian Journal of School Psychology, 27, 201–216. 10.1177/0829573512450567 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Casey EA, & Ohler K (2012). Being a positive bystander: Male antiviolence allies’ experiences of “stepping up”. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 27, 62–83. 10.1177/0886260511416479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly J, Pepler D, Craig W, & Taradash A (2000). Dating experiences of bullies in early adolescence. Child Maltreatment, 5, 299–310. 10.1177/1077559500005004002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeSmet A, Veldeman C, Poels K, Bastiaensens S, Van Cleemput K, Vandebosch H, & De Bourdeaudhuij I (2014). Determinants of self-reported bystander behavior in cyberbullying incidents amongst adolescents. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 17, 207–215. 10.1089/cyber.2013.0027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espelage D, Green H, & Polanin J (2012). Willingness to intervene in bullying episodes among middle school students: Individual and peer group influences. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 32, 776–801. 10.1177/0272431611423017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins DL, Pepler DJ, & Craig WM (2001). Naturalistic observations of peer interventions in bullying. Social Development, 10, 512–527. 10.1111/1467-9507.00178 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Katz J, & Moore J (2013). Bystander education training for campus sexual assault prevention: An initial meta-analysis. Violence and Victims, 28, 1054–1067. 10.1891/0886-6708.VV-D-12-00113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latané B, & Darley JM (1969). Bystanders “apathy”. American Scientist, 57, 244–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon S, Allen CT, Postmus JL, McMahon SM, Peterson NA, & Lowe Hoffman M (2014). Measuring bystander attitudes and behavior to prevent sexual violence. Journal of American College Health, 62, 58–66. 10.1080/07448481.2013.849258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon S, & Banyard VL (2012). When can i help? A conceptual framework for the prevention of sexual violence through bystander intervention. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 13, 3–14. 10.1177/1524838011426015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles MB, Huberman AM, & Saldaña J (2014). Qualitative data analysis (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Montaño DE, & Kasprzyk D (2002). The theory of reasoned action and the theory of planned behavior. In Glanz K, Rimer BK, & Lewis FM (Eds.), Health behavior and health education. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Nickerson AB, Aloe AM, Livingston JA, & Feeley TH (2014). Measurement of the bystander intervention model for bullying and sexual harassment. Journal of Adolescence, 37, 391–400. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2014.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polanin JR, Espelage DL, & Pigott TD (2012). A meta-analysis of school-based bullying prevention programs’ effects on bystander intervention behavior. School Psychology Review, 41, 47–65. [Google Scholar]

- Pozzoli T, & Gini G (2013). Why do bystanders of bullying help or not? A multidimensional model. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 33, 315–340. 10.1177/0272431612440172 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rigby K, & Johnson B (2006). Expressed readiness of Australian school children to act as bystanders in support of children who are being bullied. Educational Psychology, 26, 425–440. 10.1080/01443410500342047 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman EF, Johnson RM, Azrael D, Hall DM, & Weinberg J (2010). Perpetration of physical assault against dating partners, peers, and siblings among a locally representative sample of high school students in Boston, Massachusetts. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 164, 1118–1124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stueve A, Dash K, O’Donnell L, Tehranifar P, Wilson-Simmons R, Slaby RG, & Link BG (2006). Rethinking the bystander role in school violence prevention. Health Promotion Practice, 7, 117–124. 10.1177/1524839905278454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornberg R, Tenenbaum L, Varjas K, Meyers J, Jungert T, & Vanegas G (2012). Bystander motivation in bullying incidents: To intervene or not to intervene? Western Journal of Emergency Medicine, 13, 247–252. 10.5811/westjem.2012.3.11792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisz AN, & Black BM (2008). Peer intervention in dating violence: Beliefs of African- American middle school adolescents. Journal of Ethnic & Cultural Diversity in Social Work, 17, 177–196. 10.1080/15313200801947223 [DOI] [Google Scholar]