Abstract

Background:

Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy (CAA) is one of the major causes of intracerebral haemorrhage and vascular dementia in older adults. Early diagnosis will provide clinicians with an opportunity to intervene early with suitable strategies, highlighting the importance of presymptomatic CAA biomarkers.

Objective:

Investigation of pre-symptomatic CAA related blood metabolite alterations in Dutch-type hereditary CAA mutation carriers (D-CAA MCs).

Methods:

Plasma metabolites were measured using mass-spectrometry (AbsoluteIDQ® p400 HR kit) and were compared between pre-symptomatic D-CAA MCs (n=9) and non-carriers (D-CAA NCs, n=8) from the same pedigree. Metabolites that survived correction for multiple comparisons were further compared between D-CAA MCs and additional control groups (cognitively unimpaired adults).

Results:

275 metabolites were measured in the plasma, 22 of which were observed to be significantly lower in the D-CAA MCs compared to D-CAA NCs, following adjustment for potential confounding factors age, sex and APOE ε4 (p<0.05). After adjusting for multiple comparisons, only spermidine remained significantly lower in the D-CAA MCs compared to the D-CAA NCs (p<.00018). Plasma spermidine was also significantly lower in D-CAA MCs compared to the cognitively unimpaired young adult and older adult groups (p<.01). Spermidine was also observed to correlate with CSF Aβ40 (rs=.621, p=0.024), CSF Aβ42 (rs=.714, p=0.006) and brain Aβ load (rs= −.527, p= 0.030).

Conclusion:

The current study provides pilot data on D-CAA linked metabolite signals, that also associated with Aβ neuropathology and are involved in several biological pathways that have previously been linked to neurodegeneration and dementia.

Keywords: Vascular dementia, Cerebral amyloid angiopathy, Blood biomarkers, Early diagnosis, Metabolomics, Hereditary cerebral haemorrhage with amyloidosis - Dutch type, Intracerebral haemorrhage

Introduction

Sporadic Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy (CAA) is associated with the accumulation of amyloid-β (Aβ) in the cerebral vasculature and is one of the major causes of intracerebral haemorrhage and vascular dementia observed in older adults [1]. While the Boston criteria facilitates the diagnosis of possible and probable CAA, a definitive CAA diagnosis can only be achieved by post-mortem neuropathological examination [2], impeding further research investigating pre-symptomatic CAA biomarkers. Identification of pre-symptomatic CAA biomarkers will enable early diagnosis, thereby enabling clinicians with an opportunity to inform patients on associated bleeding risks with intravenous thrombolysis or anticoagulation therapy.

The Dutch-type hereditary Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy (D-CAA, also known as hereditary cerebral haemorrhage with amyloidosis Dutch type, HCHWA-D) mutation carriers (MCs), predominantly found in a few families originating from the Katwijk and Scheveningen villages in the Netherlands, present a unique opportunity to study the pre-symptomatic phase of CAA. In D-CAA MCs, a point mutation on codon 693 (guanine to cytosine transversion, E693Q) of the amyloid precursor protein gene (APP), results in the accumulation of abnormal Aβ E22Q peptide and thereby severe CAA [3]. Given that inheritance of the D-CAA mutation results in 100% penetrance, pre-symptomatic individuals carrying the D-CAA mutation can be diagnosed by genetic analysis [4]. Further, D-CAA MCs manifest symptoms, particularly intracerebral haemorrhage, at a relatively young age (50–60 years), and therefore present as a suitable model to explore pre-symptomatic CAA-related changes, relatively close to symptom onset, with minimal influence of age associated co-morbidities.

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) Aβ levels and brain Aβ load via positron emission tomography (PET) have previously been evaluated as potential CAA markers using pre-symptomatic and symptomatic D-CAA and sporadic CAA cohorts. Lower CSF Aβ40 and Aβ42 concentrations and higher Aβ PET signals have been reported in pre-symptomatic and symptomatic D-CAA MCs and sporadic CAA individuals compared to non-carrier (D-CAA NCs) and control individuals, respectively [5–7]. However, due to the invasive nature of lumbar punctures and the costs involved with amyloid-PET, potential blood biomarkers for pre-symptomatic CAA need to be investigated, as less invasive and cost-effective measures to detect CAA in its pre-symptomatic phase.

Therefore, the aim of the current study was to utilize metabolomics to reveal systemic biochemical changes associated with pre-symptomatic CAA pathogenesis that could serve as potential blood biomarkers for early CAA diagnosis and also provide insight into the biological pathways associated with the pre-symptomatic stage of CAA, relevant to future preventative trials for both, D-CAA and sporadic CAA. Blood metabolite levels were compared between pre-symptomatic D-CAA MCs (n=9) and NCs (n=8).We hypothesised that individuals within the pre-symptomatic stage of CAA (i.e. prior to stroke and cognitive impairment) will have specific metabolite alterations in the blood compared to D-CAA NCs.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Participants for comparison of plasma metabolites in D-CAA MCs versus D-CAA NCs from the same APP E693Q D-CAA pedigree whose ancestors migrated from the Netherlands to Australia, were enrolled in the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network (DIAN) study at Edith Cowan University, Western Australia (n=18). Upon DNA testing, ten participants were found to be positive for the mutation while eight were negative. One D-CAA MC had a history of stroke and was excluded from the current study in order to utilise a purely pre-symptomatic cohort. Therefore, eight D-CAA NCs and nine D-CAA MCs were included, and plasma metabolite concentrations were compared between these D-CAA NCs and D-CAA MCs from the same pedigree. Further, for the validation of plasma metabolites that survived correction for multiple comparisons analyses, two independent control groups of participants were employed for comparison against the D-CAA MCs. These independent control groups comprised cognitively unimpaired young adults without an autosomal dominant Alzheimer’s disease mutation who were also enrolled within the DIAN study, Australia (CU-1, n=7) and cognitively unimpaired older adults from the Kerr Anglican Retirement Village Initiative in Ageing Health (KARVIAH) cohort, Australia (CU-2, n=100) [8] (Supplementary Figure 1). The study was approved by the human research ethics committees at Macquarie University, Edith Cowan University and Washington University. All participants provided informed written consent.

Plasma metabolite measurements

Endogenous metabolite concentrations were measured in fasted plasma samples employing a targeted metabolomics approach. The samples were collected and stored at −80 °C prior to analysis as described previously by Bateman and colleagues [9]. The targeted metabolomics approach employed the AbsoluteIDQ® p400 HR kit (BIOCRATES Life Science AG, Innsbruck, Austria). Metabolites with >40% of measurements below the lower limit of detection (LLOD) were excluded from the analysis [10, 11]. Based on this, 275 metabolite species in the plasma were analysed within the current study (See Supplementary Material for further details).

Neuropsychological assessments

Neuropsychological data were obtained from the DIAN and KARVIAH databases, respectively. Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), a measure of general cognitive function (for DIAN and KARVIAH cohorts) [12], as well as the Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) scale, a semi-structured interview assessing dementia severity (DIAN cohort only) [13], were utilised as measures of cognitive status in the current study.

CSF Aβ concentration measurements

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) Aβ (Aβ40, Aβ42) concentrations were obtained from the DIAN database for the D-CAA NCs and MCs from the same pedigree. CSF Aβ40 and Aβ42 concentrations were measured using INNOTEST® β-AMYLOID(1–40) and INNOTEST® β-AMYLOID(1–42) (Fujirebio, Ghent, Belgium) as described previously [9].

Neuroimaging

Brain Aβ load (measured via Positron Emission Tomography (PET) using ligand 11C-Pittsburgh Compound B) represented by standard uptake value ratios (SUVR) were accessed from the DIAN database for the D-CAA NCs and MCs from the same pedigree. The SUVR utilised in the current study was calculated with FreeSurfer using the cortical mean (mean of the prefrontal, temporal, gyrus rectus and precuneus) as the region of interest with the cerebellar gray matter as the reference region, as described previously [14].

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics including means and standard deviations, or proportions were calculated for D-CAA MCs versus D-CAA NCs (from the same pedigree)/ CUs, with comparisons employing linear models or Chi-square tests as appropriate, in Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1. Composite scores were generated by taking the mean of the z-scores of the variables of interest. Linear models were employed to compare continuous variables (plasma metabolites concentrations and composite scores) between D-CAA MCs and D-CAA NCs from the same pedigree corrected for covariates age, sex and apolipoprotein E ε4 genotype (APOE ε4) status. Response variables were natural log transformed as necessary to better approximate normality and variance homogeneity. Adjustments for multiple comparisons were carried out using Bonferroni correction for metabolites compared between D-CAA MCs and D-CAA NCs, from the same pedigree, after correcting for covariates. Metabolites that survived correction for multiple comparison analyses (p<.00018), were further validated by comparing them between D-CAA MCs and independent control groups (CU-1 and CU-2). Spearman’s correlation (rs) was employed to evaluate the strength of the association between plasma metabolites (that survived correction for multiple comparisons) with CSF Aβ concentrations and brain Aβ load. All analyses were carried out on the platform R.

Table 1. Study participant characteristics.

| D-CAA NC | D-CAA MC | p | pa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 8 | 9 | - | - |

| Sex (M/F) | 3/5 | 3/6 | 0.858 | - |

| Age (Mean±SD) | 43.5±6.57 | 44.11±4.31 | 0.822 | - |

| EYO (years; Mean±SD) | −6.09±6.43 | −5.27±4.30 | 0.759 | - |

| APOE ε4 (%) | 37.5 | 22.2 | 0.490 | - |

| MMSE (Mean±SD) | 28.63±1.60 | 28.67±1.41 | 0.955 | - |

| CDR global=0 (%) | 100 | 100 | - | - |

| Stroke (%) | 0 | 0 | - | - |

| CSF Aβ40 (pg/mL; Mean±SD) | 9882.92±3076.97 | 6971.35±1088.65 | 0.051 | 0.039 |

| CSF Aβ42 (pg/mL; Mean±SD) | 618.63±206.81 | 311.67±154.85 | 0.012 | 0.007 |

| CSF Aβ42/Aβ40 (Mean±SD) | 0.068±0.027 | 0.045±0.018 | 0.108 | 0.034 |

| Brain Aβ load (SUVR, Mean±SD) | 0.985±0.078 | 1.209±0.221 | 0.016 | 0.014 |

Characteristics including sex, age, expected years to symptom onset (EYO) based on age at symptom onset of biological mutation carrier parent, APOE ε4 status, Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) scores, Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) scale scores, history of stroke, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) Aβ40 levels, CSF Aβ42 levels, CSF Aβ42/Aβ40 ratios, CSF total tau (t-tau) levels, CSF phosphorylated tau (p-tau) levels, CSF p-tau/t-tau ratios, plasma Aβ40, plasma Aβ42 levels and plasma Aβ42/Aβ40 ratios have been compared between Dutch-type hereditary cerebral amyloid angiopathy (D-CAA) mutation non-carriers (NCs) and pre-symptomatic carriers (MCs) from the same pedigree. Chi-square tests or linear models were employed as appropriate. CSF parameters presented were only compared between seven NCs and six MCs, due to missing data. CSF Aβ42 and Aβ40 were measured using the INNOTEST β-AMYLOID(1–40) and INNOTEST β-AMYLOID(1–42) (Fujirebio, Ghent, Belgium). Brain Aβ load was measured via Positron Emission Tomography and is presented as the standard uptake value ratio (SUVR) of the ligand, 11C-Pittsburgh Compound B, uptake in the cortical region (mean of the prefrontal, temporal, gyrus rectus and precuneus) as the region of interest with the cerebellar gray matter as the reference region. pa represents p-values adjusted for age, sex and APOE ε4 carrier status. p<0.05 were considered as significant.

Results

Participant characteristics

Characteristics of D-CAA NCs and D-CAA MCs from the same pedigree are presented in Table 1, wherein no significant differences were observed between the D-CAA NCs and presymptomatic MCs, except for CSF Aβ concentrations (p<.05) and brain Aβ load (p<.05) as expected [6, 7].

Participant characteristics of D-CAA MCs compared to additional D-CAA mutation non-carrier groups (CU-1 and CU-2) are presented in Supplementary Table 1. No significant differences in demographic characteristics were observed between the D-CAA MCs and the additional D-CAA mutation non-carrier groups, except for age, wherein the D-CAA MCs were significantly older than CU-1 group participants (p<.0001) and significantly younger than CU-2 group participants (p<.0001).

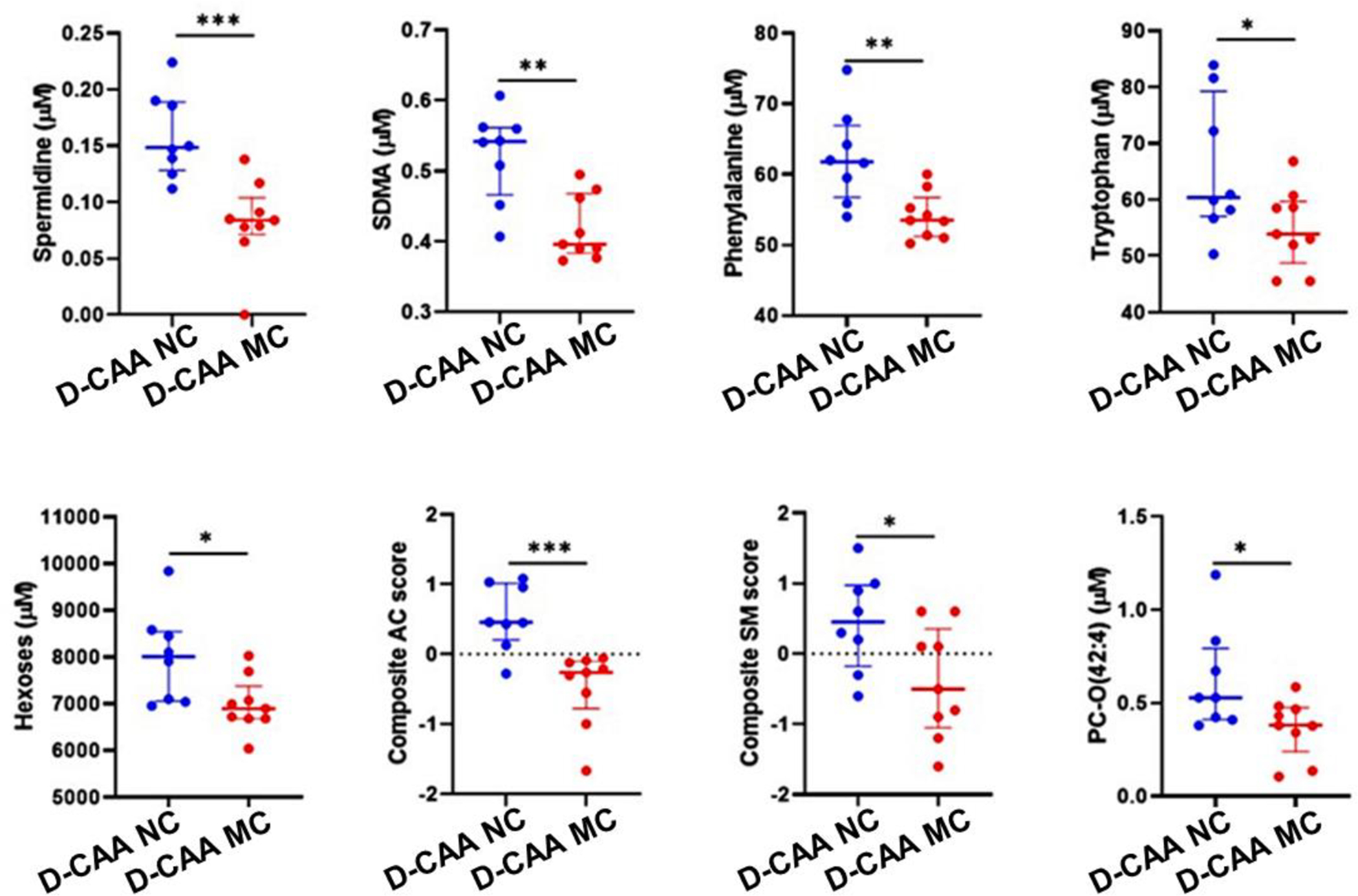

Plasma metabolite differences between D-CAA mutation carriers and non-carriers

On investigating metabolite alterations in the D-CAA MCs compared with the D-CAA NCs from the same pedigree, 22 plasma metabolites out of the 275 metabolites measured, belonging to the biogenic amine, amino acid, hexose, acylcarnitine (AC), sphingomyelin (SM) and phosphatidylcholine (PC) classes, were observed to be significantly lower in the D-CAA MCs, following adjustment for potential confounding factors age, sex and APOE ε4 genotype status at a significance level of p<0.05 (Table 2, Figure 1). However, after adjusting for multiple comparisons, only spermidine remained significantly different between D-CAA MCs and NCs (p<.00018). On comparing spermidine levels between D-CAA MCs and CUs, spermidine levels continued to be lower in the D-CAA MCs (CU-1: p=.008; CU-2: p<.0001, Table 3, Figure 2).

Table 2.

Plasma metabolites altered between D-CAA mutation non-carriers and carriers.

| D-CAA NC | D-CAA MC | p | pa | pb | pc | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biogenic amines | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||||

| Spermidine | 0.159 | 0.038 | 0.082 | 0.038 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.0001 |

| SDMA | 0.523 | 0.065 | 0.419 | 0.046 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.003 | 0.005 |

| Amino acids | ||||||||

| Phenylalanine | 62.475 | 6.635 | 54.133 | 3.291 | 0.004 | 0.006 | 0.007 | 0.011 |

| Tryptophan | 65.463 | 12.288 | 54.956 | 7.003 | 0.044 | 0.022 | 0.022 | 0.035 |

| Sum of hexoses | ||||||||

| Hexoses | 7999.5 | 983.656 | 6980.333 | 583.862 | 0.019 | 0.019 | 0.006 | 0.008 |

| Acylcarnitines | ||||||||

| AC(4:0) | 0.397 | 0.127 | 0.286 | 0.124 | 0.089 | 0.076 | 0.083 | 0.041 |

| AC(5:0) | 3.958 | 0.966 | 2.893 | 0.761 | 0.023 | 0.021 | 0.026 | 0.040 |

| AC(14:0) | 0.026 | 0.005 | 0.019 | 0.006 | 0.015 | 0.019 | 0.023 | 0.006 |

| AC(16:0) | 0.080 | 0.019 | 0.063 | 0.011 | 0.033 | 0.035 | 0.043 | 0.049 |

| Composite AC score | 0.532 | 0.474 | −0.473 | 0.538 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.001 |

| Sphingolipids | ||||||||

| SM(30:1) | 0.845 | 0.240 | 0.648 | 0.206 | 0.089 | 0.050 | 0.024 | 0.021 |

| SM(32:2) | 1.261 | 0.441 | 0.887 | 0.242 | 0.044 | 0.047 | 0.018 | 0.007 |

| SM(34:2) | 17.838 | 3.920 | 15.078 | 3.486 | 0.145 | 0.127 | 0.063 | 0.042 |

| SM(35:1) | 4.895 | 0.600 | 4.077 | 1.205 | 0.103 | 0.097 | 0.065 | 0.041 |

| SM(36:1) | 53.663 | 10.127 | 41.456 | 10.332 | 0.027 | 0.033 | 0.024 | 0.007 |

| SM(36:2) | 8.201 | 1.603 | 6.891 | 1.690 | 0.123 | 0.138 | 0.056 | 0.016 |

| SM(37:1) | 4.389 | 0.816 | 3.586 | 1.067 | 0.105 | 0.121 | 0.076 | 0.014 |

| SM(38:2) | 11.311 | 2.861 | 9.199 | 2.449 | 0.122 | 0.121 | 0.105 | 0.033 |

| SM(40:2) | 34.4 | 9.455 | 26.342 | 9.227 | 0.096 | 0.087 | 0.076 | 0.040 |

| SM(42:1) | 24.925 | 5.170 | 20.289 | 5.060 | 0.082 | 0.084 | 0.094 | 0.034 |

| SM(42:2) | 70.613 | 13.924 | 58.844 | 14.689 | 0.112 | 0.116 | 0.093 | 0.048 |

| SM(44:2) | 1.675 | 0.279 | 1.287 | 0.341 | 0.022 | 0.028 | 0.021 | 0.017 |

| Composite SM score | 0.447 | 0.697 | −0.398 | 0.781 | 0.033 | 0.037 | 0.018 | 0.004 |

| Phospholipids | ||||||||

| PC-O(42:4) | 0.621 | 0.275 | 0.368 | 0.157 | 0.032 | 0.028 | 0.018 | 0.024 |

Metabolites measured in the plasma were compared between D-CAA mutation non-carriers (D-CAA NCs, n=8) and pre-symptomatic mutation carriers (D-CAA MCs, n=9) employing linear models. pa indicates p-values adjusted for age; pb indicates p values adjusted for age and sex; pc indicates p values adjusted for age, sex and APOE ε4 status. Only metabolites with pc<0.05 have been presented in the current table and were considered as statistically significant. All metabolite concentrations are presented in μM. SDMA, symmetric dimethyl arginine; PC-O, phospholipid with choline headgroup and presence of an alkyl ether substituent.

Figure 1. Plasma metabolites altered between D-CAA mutation non-carriers and carriers from the same pedigree.

Metabolites measured in the plasma were compared between D-CAA mutation non-carriers (D-CAA NCs, n=8) and pre-symptomatic mutation carriers (D-CAA MCs, n=9) employing linear models. Composite scores for acylcarnitine (AC) and sphingomyelin (SM) were generated from the mean of the z-scores of AC and SM species, respectively, as listed in Table 2. Line segments within the plots represents the median and the error bars represent the interquartile range. *represents p<0.05, **represents p≤0.005, ***represents p≤0.001. SDMA, symmetric dimethyl arginine; AC, acylcarnitine; SM, sphingomyelin; PC-O, phospholipid with choline headgroup and presence of an alkyl ether substituent.

Table 3. Comparison of plasma spermidine levels between D-CAA and CU adults.

| D-CAA MC | CU-1 | CU-2 | p | padj | pa | pb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=9 | N=7 | N=100 | ||||

| 0.082±0.038 | 0.177±0.029 | 0.195±0.054 | <.0001 | <.0001 | .008 | <.0001 |

Plasma spermidine levels (presented in mean±SD, μM) in D-CAA MCs were compared with plasma spermidine levels in cognitively unimpaired younger adults (CU-1) and cognitively unimpaired older adults (CU-2). p and padj represent univariate p-values before and after adjusting for age, sex and APOE ε4 carrier status. pa and pb represent pairwise comparisons between D-CAA MC and CU-1, D-CAA MC and CU-2, respectively.

Figure 2. Comparison of plasma spermidine between D-CAA mutation carriers and non-carriers.

Plasma spermidine levels were compared between D-CAA mutation carriers (D-CAA MC) and D-CAA mutation non-carrier groups (D-CAA NC from same pedigree as D-CAA MC, cognitively unimpaired young adults (CU-1) and cognitively unimpaired older adults (CU-2)) using general linear models. The line segment within the plot represents the median and the error bars represent the interquartile range.

Association of CSF Aβ with plasma spermidine

Within the D-CAA MCs and D-CAA NCs from the same pedigree, a significant positive association was observed between CSF Aβ40 and spermidine (rs=.621, p=0.024). Further, a positive association was observed between CSF Aβ42 and spermidine (rs=.714, p=0.006).

Association of brain Aβ load with plasma spermidine

Given that brain Aβ load was significantly higher in the D-CAA MCs compared to the NCs, we expected that spermidine will be inversely associated with brain Aβ load given that spermidine was significantly lower in D-CAA MCs. Indeed, an inverse association was observed between brain Aβ load and spermidine (rs= −.527, p= 0.030) within the D-CAA MCs and D-CAA NCs from the same pedigree.

Discussion

The current study is the first to report on blood metabolite alterations associated with the pre-symptomatic stage of D-CAA i.e. prior to stroke and cognitive impairment. Currently, in addition to a lack of a treatment, there is also no early diagnostic test for CAA. Within the present study, two-hundred and seventy-five metabolite species in the blood were compared between D-CAA MCs and NCs, wherein 22 metabolites were observed to be significantly lower in the D-CAA MCs following adjustment for potential confounding factors. However, after adjusting for multiple comparisons, only spermidine remained significantly altered. Spermidine was also observed to have a positive association with CSF Aβ40 and Aβ42 and an inverse association with brain Aβ load.

The biogenic amine spermidine has been reported to manifest antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, promote mitochondrial metabolic function and respiration, and enhance proteostasis and chaperone activity [15]. Oral supplementation and dietary intake of spermidine has been reported to positively influence cognitive performance in older adults at risk of AD and inversely, with all-cause mortality [16, 17]. Furthermore, decreased spermidine levels in the plasma have been observed in AD patients compared to individuals with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and healthy controls [18]. While these observations are in line with the findings of lower spermidine levels in D-CAA MCs seen within the present study given that 80% of AD patients show CAA comorbidity [19], the exact mechanisms are currently not known. However, it is known that the neuroregulatory action of spermidine results from its interaction with ionotropic receptors, particularly N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors, and the neuroprotective properties of spermidine are posited to result from the inducement of autophagy in glial or neuronal cells and suppression of inflammation [15, 20]. The ability of spermidine to permeate the mammalian blood brain barrier remains elusive, however it has been suggested that spermidine may act through peripheral routes that involve modulating inflammation via cytokines and immune cells that can reach the cerebral tissue [15, 21, 22].

Additionally, other metabolite alterations observed within the current study, although did not survive correction for multiple comparisons, have been reported to be associated with nitric oxide homeostasis, oxidative stress, inflammation, mitochondrial function, glucose and cell membrane lipid metabolism, biological pathways that have previously been implicated in neurodegenerative diseases [10, 11, 23–29].

It is recognised that this study has limitations given its modest sample size and that further studies are required to validate these exploratory findings in independent groups comprising pre-symptomatic D-CAA MCs and age- and sex-matched NCs. Additionally, future studies also need to investigate whether similar metabolite alterations are present between individuals with pre-symptomatic sporadic CAA and age- and sex-matched controls. Furthermore, future studies also need to investigate whether similar metabolite alterations can differentiate individuals with pre-symptomatic CAA (D-CAA and sporadic) from age- and sex-matched individuals with preclinical AD (familial and sporadic, prior to symptom manifestation) and symptomatic AD (familial and sporadic). The consideration of longitudinal changes in metabolite alterations in the CAA pathology progression or CAA pathogenesis trajectory will also allow evaluation of metabolite alterations as prognostic markers to track disease severity and serve as potential novel therapeutic targets. Furthermore, while a few studies using proteomics and transcriptomics techniques on post-mortem brain tissue with CAA have been carried out [30–32], employing similar proteomics and transcriptomics techniques in blood samples from patients with sporadic CAA and D-CAA will complement the CAA-associated metabolite alterations observed within the current study, contributing to efforts in developing a robust panel of pre-symptomatic blood markers for CAA.

It is also important to acknowledge the challenges involved in investigating biomarkers for pre-symptomatic CAA, given the rare incidence of D-CAA and thereby the inaccessibility to large independent D-CAA cohorts for validation, even though D-CAA MCs serve as a suitable model for such research. Further, access to blood samples from individuals within the pre-symptomatic stage of sporadic CAA may prove to be another challenging aspect. Additionally, expanding the current pilot observations to sporadic CAA will also be a future challenge given the presence of mixed pathologies and comorbid conditions in such cases, wherein there are usually traces of AD pathology in CAA brains and traces of CAA in AD brains [33], therefore raising the question of whether biomarker/metabolite alterations observed are associated with CAA pathology and/or AD pathology. To understand whether metabolite changes are associated with CAA pathology or AD pathology, studies employing “disconnected” cases (severe CAA with no or very mild AD, and vice versa) will be particularly informative. Further, age related vascular comorbidities such as hypertension or diabetes may also contribute to mixed pathology in individuals with sporadic CAA and will therefore need to be accounted for.

To conclude, the current study provides pilot data on D-CAA linked metabolite signals, that also associated with Aβ neuropathology and are involved in several biological pathways that have previously been linked to neurodegeneration and dementia. Further studies are required to validate observations from the current study.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) project grant APP1129627 and National Institute of Health (NIH) grant for the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network study U19AG032438. We thank the participants and their families for their participation and cooperation, and the DIAN research and support staff at Australian Alzheimer’s Research Foundation (AARF), the Mental Health Research Institute (MHRI) and Washington University for their contributions to this study. We thank all staff of the DIAN Administration, Clinical, Biomarker, Genetics and Imaging cores for their contributions. We also thank Dr Celeste Karch and Dr Xiong Xu for providing us with the supporting data from the master DIAN database. We thank the staff at the Australian Proteome Analysis Facility (APAF) for their support in this study and acknowledge that this study used NCRIS-enabled APAF infrastructure. We also thank Professor Subhojit Roy for his valuable feedback. We thank Dr Manuel Kratzke and Dr Markus Langsdorf for the technical support they provided remotely.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

All authors report no competing financial interest in relation to the work described in this manuscript.

References

- 1.Viswanathan A, Greenberg SM (2011) Cerebral amyloid angiopathy in the elderly. Ann Neurol 70, 871–880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Knudsen KA, Rosand J, Karluk D, Greenberg SM (2001) Clinical diagnosis of cerebral amyloid angiopathy: validation of the Boston criteria. Neurology 56, 537–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maat-Schieman M, Roos R, van Duinen S (2005) Hereditary cerebral hemorrhage with amyloidosis-Dutch type. Neuropathology 25, 288–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bakker E, van Broeckhoven C, Haan J, Voorhoeve E, van Hul W, Levy E, Lieberburg I, Carman MD, van Ommen GJ, Frangione B, et al. (1991) DNA diagnosis for hereditary cerebral hemorrhage with amyloidosis (Dutch type). Am J Hum Genet 49, 518–521. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Verbeek MM, Kremer BP, Rikkert MO, Van Domburg PH, Skehan ME, Greenberg SM (2009) Cerebrospinal fluid amyloid beta(40) is decreased in cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Ann Neurol 66, 245–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Etten ES, Verbeek MM, van der Grond J, Zielman R, van Rooden S, van Zwet EW, van Opstal AM, Haan J, Greenberg SM, van Buchem MA, Wermer MJ, Terwindt GM (2017) beta-Amyloid in CSF: Biomarker for preclinical cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Neurology 88, 169–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schultz AP, Kloet RW, Sohrabi HR, van der Weerd L, van Rooden S, Wermer MJH, Moursel LG, Yaqub M, van Berckel BNM, Chatterjee P, Gardener SL, Taddei K, Fagan AM, Benzinger TL, Morris JC, Sperling R, Johnson K, Bateman RJ, Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer N, Gurol ME, van Buchem MA, Martins R, Chhatwal JP, Greenberg SM (2019) Amyloid imaging of dutch-type hereditary cerebral amyloid angiopathy carriers. Ann Neurol 86, 616–625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goozee K, Chatterjee P, James I, Shen K, Sohrabi HR, Asih PR, Dave P, ManYan C, Taddei K, Ayton SJ, Garg ML, Kwok JB, Bush AI, Chung R, Magnussen JS, Martins RN (2018) Elevated plasma ferritin in elderly individuals with high neocortical amyloid-beta load. Mol Psychiatry 23, 18071812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bateman RJ, Xiong C, Benzinger TL, Fagan AM, Goate A, Fox NC, Marcus DS, Cairns NJ, Xie X, Blazey TM, Holtzman DM, Santacruz A, Buckles V, Oliver A, Moulder K, Aisen PS, Ghetti B, Klunk WE, McDade E, Martins RN, Masters CL, Mayeux R, Ringman JM, Rossor MN, Schofield PR, Sperling RA, Salloway S, Morris JC (2012) Clinical and biomarker changes in dominantly inherited Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med 367, 795–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Toledo JB, Arnold M, Kastenmuller G, Chang R, Baillie RA, Han X, Thambisetty M, Tenenbaum JD, Suhre K, Thompson JW, John-Williams LS, MahmoudianDehkordi S, Rotroff DM, Jack JR, Motsinger-Reif A, Risacher SL, Blach C, Lucas JE, Massaro T, Louie G, Zhu H, Dallmann G, Klavins K, Koal T, Kim S, Nho K, Shen L, Casanova R, Varma S, Legido-Quigley C, Moseley MA, Zhu K, Henrion MYR, van der Lee SJ, Harms AC, Demirkan A, Hankemeier T, van Duijn CM, Trojanowski JQ, Shaw LM, Saykin AJ, Weiner MW, Doraiswamy PM, Kaddurah-Daouk R, Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging I, the Alzheimer Disease Metabolomics C (2017) Metabolic network failures in Alzheimer’s disease: A biochemical road map. Alzheimers Dement 13, 965–984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chatterjee P, Cheong YJ, Bhatnagar A, Goozee K, Wu Y, McKay M, Martins IJ, Lim WLF, Pedrini S, Tegg M, Villemagne VL, Asih PR, Dave P, Shah TM, Dias CB, Fuller SJ, Hillebrandt H, Gupta S, Hone E, Taddei K, Zetterberg H, Blennow K, Sohrabi HR, Martins RN (2020) Plasma metabolites associated with biomarker evidence of neurodegeneration in cognitively normal older adults. J Neurochem. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR (1975) “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 12, 189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morris JC, Ernesto C, Schafer K, Coats M, Leon S, Sano M, Thal LJ, Woodbury P (1997) Clinical dementia rating training and reliability in multicenter studies: the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study experience. Neurology 48, 1508–1510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Su Y, Blazey TM, Snyder AZ, Raichle ME, Marcus DS, Ances BM, Bateman RJ, Cairns NJ, Aldea P, Cash L, Christensen JJ, Friedrichsen K, Hornbeck RC, Farrar AM, Owen CJ, Mayeux R, Brickman AM, Klunk W, Price JC, Thompson PM, Ghetti B, Saykin AJ, Sperling RA, Johnson KA, Schofield PR, Buckles V, Morris JC, Benzinger TLS, Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer N (2015) Partial volume correction in quantitative amyloid imaging. Neuroimage 107, 55–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Madeo F, Eisenberg T, Pietrocola F, Kroemer G (2018) Spermidine in health and disease. Science 359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wirth M, Benson G, Schwarz C, Kobe T, Grittner U, Schmitz D, Sigrist SJ, Bohlken J, Stekovic S, Madeo F, Floel A (2018) The effect of spermidine on memory performance in older adults at risk for dementia: A randomized controlled trial. Cortex 109, 181–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kiechl S, Pechlaner R, Willeit P, Notdurfter M, Paulweber B, Willeit K, Werner P, Ruckenstuhl C, Iglseder B, Weger S, Mairhofer B, Gartner M, Kedenko L, Chmelikova M, Stekovic S, Stuppner H, Oberhollenzer F, Kroemer G, Mayr M, Eisenberg T, Tilg H, Madeo F, Willeit J (2018) Higher spermidine intake is linked to lower mortality: a prospective population-based study. Am J Clin Nutr 108, 371–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Joaquim HPGC AC; Forlenza OV.; Gattaz WF.; Talib LL (2019) Decreased plasmatic spermidine and increased spermine in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease patients. Archives of Clinical Psychiatry 46, 120–124. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jellinger KA (2002) Alzheimer disease and cerebrovascular pathology: an update. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 109, 813–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eisenberg T, Knauer H, Schauer A, Buttner S, Ruckenstuhl C, Carmona-Gutierrez D, Ring J, Schroeder S, Magnes C, Antonacci L, Fussi H, Deszcz L, Hartl R, Schraml E, Criollo A, Megalou E, Weiskopf D, Laun P, Heeren G, Breitenbach M, Grubeck-Loebenstein B, Herker E, Fahrenkrog B, Frohlich KU, Sinner F, Tavernarakis N, Minois N, Kroemer G, Madeo F (2009) Induction of autophagy by spermidine promotes longevity. Nat Cell Biol 11, 1305–1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shin WW, Fong WF, Pang SF, Wong PC (1985) Limited blood-brain barrier transport of polyamines. J Neurochem 44, 1056–1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Diler AS, Ziylan YZ, Uzum G, Lefauconnier JM, Seylaz J, Pinard E (2002) Passage of spermidine across the blood-brain barrier in short recirculation periods following global cerebral ischemia: effects of mild hyperthermia. Neurosci Res 43, 335–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mapstone M, Cheema AK, Fiandaca MS, Zhong X, Mhyre TR, Macarthur LH, Hall WJ, Fisher SG, Peterson DR, Haley JM, Nazar MD, Rich SA, Berlau DJ, Peltz CB, Tan MT, Kawas CH, Federoff HJ (2014) Plasma phospholipids identify antecedent memory impairment in older adults. Nat Med 20, 415–418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Varma VR, Oommen AM, Varma S, Casanova R, An Y, Andrews RM, O’Brien R, Pletnikova O, Troncoso JC, Toledo J, Baillie R, Arnold M, Kastenmueller G, Nho K, Doraiswamy PM, Saykin AJ, Kaddurah-Daouk R, Legido-Quigley C, Thambisetty M (2018) Brain and blood metabolite signatures of pathology and progression in Alzheimer disease: A targeted metabolomics study. PLoS Med 15, e1002482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chatterjee P, Goozee K, Lim CK, James I, Shen K, Jacobs KR, Sohrabi HR, Shah T, Asih PR, Dave P, ManYan C, Taddei K, Lovejoy DB, Chung R, Guillemin GJ, Martins RN (2018) Alterations in serum kynurenine pathway metabolites in individuals with high neocortical amyloid-beta load: A pilot study. Sci Rep 8, 8008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chatterjee P, Zetterberg H, Goozee K, Lim CK, Jacobs KR, Ashton NJ, Hye A, Pedrini S, Sohrabi HR, Shah T, Asih PR, Dave P, Shen K, Taddei K, Lovejoy DB, Guillemin GJ, Blennow K, Martins RN (2019) Plasma neurofilament light chain and amyloid-beta are associated with the kynurenine pathway metabolites in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. J Neuroinflammation 16, 186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Balez R, Ooi L (2016) Getting to NO Alzheimer’s Disease: Neuroprotection versus Neurotoxicity Mediated by Nitric Oxide. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2016, 3806157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Selley ML (2003) Increased concentrations of homocysteine and asymmetric dimethylarginine and decreased concentrations of nitric oxide in the plasma of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging 24, 903–907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cristofano A, Sapere N, La Marca G, Angiolillo A, Vitale M, Corbi G, Scapagnini G, Intrieri M, Russo C, Corso G, Di Costanzo A (2016) Serum Levels of Acyl-Carnitines along the Continuum from Normal to Alzheimer’s Dementia. PLoS One 11, e0155694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hondius DC, Eigenhuis KN, Morrema THJ, van der Schors RC, van Nierop P, Bugiani M, Li KW, Hoozemans JJM, Smit AB, Rozemuller AJM (2018) Proteomics analysis identifies new markers associated with capillary cerebral amyloid angiopathy in Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol Commun 6, 46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Manousopoulou A, Gatherer M, Smith C, Nicoll JAR, Woelk CH, Johnson M, Kalaria R, Attems J, Garbis SD, Carare RO (2017) Systems proteomic analysis reveals that clusterin and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases 3 increase in leptomeningeal arteries affected by cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 43, 492–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grand Moursel L, van Roon-Mom WMC, Kielbasa SM, Mei H, Buermans HPJ, van der Graaf LM, Hettne KM, de Meijer EJ, van Duinen SG, Laros JFJ, van Buchem MA, t Hoen PAC, van der Maarel SM, van der Weerd L (2018) Brain Transcriptomic Analysis of Hereditary Cerebral Hemorrhage With Amyloidosis-Dutch Type. Front Aging Neurosci 10, 102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith EE (2018) Cerebral amyloid angiopathy as a cause of neurodegeneration. J Neurochem 144, 651–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.