Abstract

The spreading of viral hepatitis among injecting drug users (IDU) is an emerging public health concern. This study explored the prevalence and the risks of hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV) and hepatitis D virus (HDV) among IDU-dominant prisoners in Taiwan. HBV surface antigen (HBsAg), antibodies to HCV (anti-HCV) and HDV (anti-HDV), viral load and HCV genotypes were measured in 1137(67.0%) of 1697 prisoners. 89.2% of participants were IDUs and none had HIV infection. The prevalence of HBsAg, anti-HCV, dual HBsAg/anti-HCV, HBsAg/anti-HDV, and triple HBsAg/anti-HCV/anti-HDV was 13.6%, 34.8%, 4.9%, 3.4%, and 2.8%, respectively. HBV viremia rate was significantly lower in HBV/HCV-coinfected than HBV mono-infected subjects (66.1% versus 89.9%, adjusted odds ratio/95% confidence intervals [aOR/CI] = 0.27/0.10–0.73). 47.5% anti-HCV-seropositive subjects (n = 396) were non-viremic, including 23.2% subjects were antivirals-induced. The predominant HCV genotypes were genotype 6(40.9%), 1a(24.0%) and 3(11.1%). HBsAg seropositivity was negatively correlated with HCV viremia among the treatment naïve HCV subjects (44.7% versus 72.4%, aOR/CI = 0.27/0.13–0.58). Anti-HCV seropositivity significantly increased the risk of anti-HDV-seropositivity among HBsAg carriers (57.1% versus 7.1%, aOR/CI = 15.73/6.04–40.96). In conclusion, IUDs remain as reservoirs for multiple hepatitis viruses infection among HIV-uninfected prisoners in Taiwan. HCV infection increased the risk of HDV infection but suppressed HBV replication in HBsAg carriers. An effective strategy is mandatory to control the epidemic in this high-risk group.

Subject terms: Microbiology, Gastroenterology

Introduction

Blood-borne viral hepatitis B, C, and D are the major causes of hepatocellular carcinoma and end stage liver diseases. It is estimated approximately 15–20% of the adults are carriers of hepatitis B virus (HBV) and 2–5% are infected with hepatitis C virus (HCV) in Taiwan1, 2. Anti-HCV positive rate can be as high as 30% in certain endemic areas located in southwestern coast of Taiwan3. Hepatitis D virus (HDV) is a defective virus which requires envelope proteins of HBV to assemble a new virion 4. The global prevalence of HDV was around 0.8% in general population and 13% in HBV carriers, which contributes rapid progression of end stage liver diseases5.

In Taiwan, the prevalence of chronic hepatitis B in the younger generation dropped to less than 1% after implementation the nationwide HBV vaccination program since 1986 1, 6. As an evolution of antiviral therapy from interferon to direct-acting antiviral drugs (DAA), the cure rate of HCV improves from 50% to more than 97% 7, 8. The disease burden of HBV and HCV will gradually decrease in general population, but increases in injecting drug users (IDU). The HBV prevalence in IDUs was around 16% in both hospital-based cohort and prisoners 9, 10. However, the HCV prevalence rate was up to around 98% in IDUs with immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and 89% in IDUs without HIV infection10. Similarly, among HBV-seropositive IDUs in Taiwan, the prevalence rate of HDV in subjects with and without HIV infection in hospital-based population was 74.9% and 43.9%, respectively11, and 84.2% and 40.0% in prisoners, respectively12.

The transmission of hepatitis B, C and D among IDUs has been an emerging public health concern in Taiwan. Approximately 53,000 prisoners are incarcerated out of the 23 million people in Taiwan, and about half of the prisoners serve their sentences because of substance abuse. Nevertheless, only sporadic native studies were conducted on the epidemiological trends of viral hepatitis among this high-risk population yet. The aims of this study were to explore the prevalence of hepatitis B, C and D, to analyze the risk factors of viral hepatitis in HIV-uninfected IDUs-dominant prisoners and to evaluate the status of HCV treatment in the DAA era.

Methods

Subjects

A total of 1137 (67.0%) participants among 1697 inmates of Penghu Prison (Agency of Corrections, Ministry of Justice, Taiwan) received the screening for viral hepatitis B, C and D in September 2019. All inmates were routinely examined for human immune-deficiency virus (HIV-1) test when incarcerated in the prison and recheck it annually. HIV-infected prisoners will be transferred to Taichung Prison owing to lack of infection specialist in Penghu Prison. Seropositive for HIV-1 and clinical information regarding antiviral therapy were obtained from the medical records. This study was taken in conformity to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the ethics committee of Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital. Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

Biochemical and hepatitis markers analyses

Biochemical analyses were evaluated on a multichannel autoanalyzer (Hitachi Inc, Tokyo, Japan). The algorithm of screening for hepatitis B, C, and D was shown as Supplementary Fig. S1.

Hepatitis B

The hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg), antibody to hepatitis e antigen (anti-HBe), antibody to hepatitis B core antigen (anti-HBc IgG) and antibody to hepatitis B surface antigen (anti-HBs) were detected using commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, IL, USA). The HBsAg titer was assessed using the Abbott Architect HBsAg QT assay (detection range: 0.05 to 250 IU/ml). HBV DNA was quantified using the CobasAmpliPrep/CobasTaqMan HBV assay (detection range 20–1.7 × 108 IU/ml, CAP/CTM Version 2.0, Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) 13.

Hepatitis C

Anti-HCV antibody was determined by the third generation, commercially available ELISA kit (Ax SYM HCV III; Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, IL). Both the serum HCV RNA and genotypes were assessed by real-time PCR assays (low limit of detection: 12 IU/ml, RealTime HCV; Abbott Molecular, Des Plaines IL, USA)14.

Hepatitis D

Anti‐HDV IgG antibody was determined using the anti‐HDV ELISA kit (General Biologicals Corporation, Taiwan). Serum HDV RNA was quantified using a LightMix Kit HDV (Berlin, Germany) on a Roche LightCycler (detection limit: 10 copies/ml)15.

Statistical analysis

The continuous variables were compared using Student's t test. The categorical variables were accessed using χ2 or Fisher's exact test. Multivariate logistic regression test was used to analyze the risk factors of virus exposure and viremia. A two-tailed p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Anti-HCV-seropositive subjects with undetectable HCV RNA was defined as spontaneous HCV clearance if they never received anti-HCV therapy, and as treatment-induced HCV clearance if they had ever received anti-HCV therapy. Subjects who were HCV viremic or who were treatment-induced HCV clearance were further classified as supposed HCV viremia. All statistical analyses were performed using Statistical Product and Service Solutions (SPSS) software, version 17.0. (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

Basic characteristics

The mean age of 1137 participants was 45.4 ± 9.6 years; 1130 (99.4%) were male; 1014 (89.2%) had an intravenous substance abuse history; None had known history of HIV infection (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline demographics.

| All | HBsAg (+) | Anti-HCV (+) | Anti-HDV (+) | NBNC hepatitis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 1137 | 155 (13.6%) | 396 (34.8%) | 39 (3.4%) | 83 (7.3%) |

| Age (years) | 45.4 ± 9.6 | 46.1 ± 7.4 | 47.8 ± 8.2 | 47.7 ± 7.3 | 41.9 ± 10.4 |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 1130 (99.4%) | 154 (99.4%) | 396(100.0%) | 39 (100.0%) | 82 (98.8%) |

| Female | 7 (0.6%) | 1 (0.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.2%) |

| AST (IU/ml) | 26.3 ± 16.4 | 28.1 ± 14.2 | 32.5 ± 23.1 | 29.1 ± 15.4 | 38.8 ± 14.9 |

| ALT (IU/ml) | 32.3 ± 29.9 | 35.1 ± 25.8 | 42.6 ± 41.2 | 34.8 ± 25.8 | 63.0 ± 25.3 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.2 ± 3.5 | 23.8 ± 3.0 | 24.0 ± 3.2 | 24.3 ± 3.1 | 27.5 ± 4.5 |

| FIB-4 | 0.95 ± 0.62 | 1.09 ± 0.81 | 1.22 ± 0.82 | 1.32 ± 1.20 | 0.81 ± 0.64 |

| IDU | |||||

| Yes | 1014 (89.2%) | 134 (86.5%) | 389 (98.2%) | 39 (100.0%) | 64 (77.1%) |

| No | 123 (10.8%) | 21 (13.5%) | 7 (1.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 19 (22.9%) |

| Co-infection | |||||

| HBsAg (+) | – | – | 56(14.1%) | 39(100%) | – |

| Anti-HCV (+) | – | 56(36.1%) | – | 32(82.1%) | – |

| Anti-HDV (+) | – | 39(25.2%) | 32(8.1%) | – | – |

| All HBV/HCV/HDV markers (+) | – | 32(20.6%) | 32(8.1%) | 32(82.1%) | – |

| HIV (+) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

HBsAg hepatitis B surface antigen; anti-HCV hepatitis C antibody; anti-HDV hepatitis D antibody; NBNC hepatitis non-B, non-C hepatitis, defined as subjects with elevated liver function tests but seronegative for HBsAg and anti-HCV; AST aspartate aminotransferase; ALT alanine aminotransferase; BMI body mass index; FIB-4 Fibrosis-4 index; IDU injecting drug user; HIV human immunodeficiency virus.

The prevalence of viral hepatitis

The seroprevalence rate of HBV, HCV, and HDV infections was 13.6%, 34.8% and 3.4%, respectively. Among 155 subjects with HBsAg seropositivity, 56 (36.1%) subjects had anti-HCV seropositivity, 39 (25.2%) with anti-HDV seropositivity, and 32 (20.6%) with triple HBV/HCV/HDV seromarkers. Among 396 subjects with anti-HCV seropositive, 56 (14.1%) had HBV/HCV dual infection, and 32 (8.1%) HBV/HCV/HDV triple infections. The anti-HCV seroprevalence rate increased gradually with age, greater than 35% in groups older than 40 years old (Supplementary Fig. S2). Among 39 subjects with HBV/HDV dual infections, 32 (82.1%) subjects had triple HBV/HCV/HDV infections. The global HBV/HCV/HDV triple infection rate was 2.8%. Eighty-three subjects (7.3%) with elevated liver function test were seronegative for HBsAg and anti-HCV (Table 1).

Factors associated with HBV infection and HBV viremia

Table 2 showed the factors associated with HBsAg-seropositivity. No HBV carrier was born after 1986, the year of mass HBV vaccination in Taiwan. Among 155 HBV carrier, 9.7% subjects were HBeAg positive, and 89.0% subjects had anti-HBe antibody. The proportions of sex, history of IDU, anti-HCV seropositivity, and the levels of liver function tests were comparable between subjects with and without HBsAg-seropositivity. Compared with HBsAg seronegative subjects, HBsAg seropositive inmates had significantly lower rate of supposed HCV viremia (53.6% vs 79.4%, p = 2.9 × 10–5) and significantly lower HCV RNA levels (2.29 ± 3.04 vs 3.25 ± 3.05 log10IU/ml, p = 0.030).

Table 2.

Factors associated with HBV infection and HBV viremia.

| All (n = 1,137) | HBsAg (+) (n = 155) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HBsAg (+) | HBsAg (−) | p-value | HBV DNA (+) | HBV DNA (−) | p-value | |

| n | 155 (13.6%) | 982 (86.4%) | 126 (81.3%) | 29 (18.7%) | ||

| Age | ||||||

| Mean ± SD | 46.1 ± 7.4 | 45.3 ± 9.9 | 0.227 | 45.9 ± 7.5 | 47.0 ± 7.2 | 0.466 |

| Before 1986 | 155 (100%) | 878 (89.4%) | 2.2 × 10–7 | 126 (100%) | 29 (100%) | N/A |

| After 1986 | 0 (0.0%) | 104 (10.6) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | ||

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 154 (99.4%) | 976 (99.4%) | 1.000 | 125 (99.2%) | 29 (100%) | 1.000 |

| Female | 1 (0.6%) | 6 (0.6%) | 1 (0.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | ||

| AST (IU/ml) | 28.1 ± 14.2 | 26.0 ± 16.7 | 0.143 | 27.9 ± 14.4 | 29.0 ± 13.3 | 0.691 |

| ALT (IU/ml) | 35.1 ± 25.8 | 31.9 ± 30.5 | 0.219 | 35.3 ± 26.2 | 34.1 ± 24.6 | 0.821 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.8 ± 3.0 | 24.2 ± 3.6 | 0.173 | 23.7 ± 2.9 | 24.3 ± 3.1 | 0.208 |

| FIB-4 | 1.09 ± 0.81 | 0.93 ± 0.58 | 0.002 | 1.02 ± 0.59 | 1.41 ± 1.39 | 0.156 |

| IDU | ||||||

| Yes | 134 (86.5%) | 880 (89.6%) | 0.239 | 109 (86.5%) | 25 (86.2%) | 1.000 |

| No | 21 (13.5%) | 102 (10.4%) | 17 (13.5%) | 4 (13.8%) | ||

| NUC (n, %) | 6 (3.9%) | N/A | N/A | 5 (4.0%) | 1 (3.4%) | 1.000 |

| HBeAg in HBsAg(+) subjects | ||||||

| Positive | 15 (9.7%) | N/A | N/A | 13(10.3%) | 2 (6.9%) | 0.738 |

| Negative | 140 (90.3%) | 113 (89.7%) | 27 (93.1%) | |||

| Anti-HBe in HBsAg(+) subjects | ||||||

| Positive | 138 (89.0%) | N/A | N/A | 112 (88.9%) | 26 (89.7%) | 1.000 |

| Negative | 17 (11.0%) | 14 (11.1%) | 3 (10.3%) | |||

| Anti-HBs | ||||||

| Positive | 5 (3.2%) | 657 (67.2%) | 6.4 × 10–51 | 4 (3.2%) | 1 (3.4%) | 1.000 |

| Negative | 150 (96.8%) | 321 (32.8%) | 122 (96.8%) | 28 (96.6%) | ||

| Anti-HBc | ||||||

| Positive | 154 (99.4%) | 627 (64.2%) | 1.1 × 10–14 | 126 (100%) | 28 (96.6%) | 0.187 |

| Negative | 1 (0.6%) | 350 (35.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (3.4%) | ||

| Anti-HCV | ||||||

| Positive | 56 (36.1%) | 340 (34.6%) | 0.715 | 37 (29.4%) | 19 (65.5%) | 2.6 × 10–4 |

| Negative | 99 (63.9%) | 642 (65.4%) | 89 (70.6%) | 10 (34.5%) | ||

| HCV RNA in anti-HCV (+) subjects | ||||||

| Mean ± SD (log IU/ml) | 2.29 ± 3.04 | 3.25 ± 3.05 | 0.030 | 1.88 ± 2.83 | 3.08 ± 3.34 | 0.193 |

| Positive | 21 (37.5%) | 187 (55.0%) | 0.015 | 12 (32.4%) | 9 (47.4%) | 0.274 |

| Negative | 35 (62.5%) | 153 (45.0%) | 25 (67.6%) | 10 (52.6%) | ||

| Supposed HCV RNA in anti-HCV (+) subjects | ||||||

| Positive | 30 (53.6%) | 270 (79.4%) | 2.9 × 10–5 | 17 (45.9%) | 13 (68.4%) | 0.110 |

| Negative | 26 (46.4%) | 70 (20.6%) | 20 (54.1%) | 6 (31.6%) | ||

| HCV genotype in HCV RNA (+) subjects | ||||||

| 1a | 5(23.8%) | 45(23.8%) | 0.338 | 1(8.3%) | 4(44.4%) | 0.093 |

| 1b | 2(9.5%) | 20(10.6%) | 2(16.7%) | 0(0.0%) | ||

| 2 | 0(0.0%) | 21(11.1%) | 0(0.0%) | 0(0.0%) | ||

| 3 | 1(4.8%) | 22(11.6%) | 0(0.0%) | 1(11.2%) | ||

| 6 | 13(61.9%) | 72(38.1%) | 9(75.0%) | 4(44.4%) | ||

| Mixed | 0(0.0%) | 3(1.6%) | 0(0.0%) | 0(0.0%) | ||

| Undetermined | 0(0.0%) | 6(3.2%) | 0(0.0%) | 0(0.0%) | ||

| Anti-HDV in HBsAg (+) subjects | ||||||

| Positive | 39(25.2%) | N/A | N/A | 26(20.6%) | 13(44.8%) | 0.007 |

| Negative | 116(74.8%) | 100(79.4%) | 16(55.2%) | |||

| HDV RNA in anti-HDV (+) subjects | ||||||

| Positive | 21(53.8%) | N/A | N/A | 16(61.5%) | 5(38.5%) | 0.173 |

| Negative | 18(46.2%) | 10(38.5%) | 8(61.5%) | |||

p.s. Supposed HCV RNA seropositivity included HCV viremia subjects and HCV non-viremia subjects induced by antiviral therapy.

AST aspartate aminotransferase; ALT alanine aminotransferase; BMI body mass index; FIB-4 Fibrosis-4 index; IDU injecting drug users; NUC nucleotide analogue; HBsAg hepatitis B surface antigen; HBeAg hepatitis B envelope antigen; anti-HBe hepatitis B envelop antibody; anti-HBs hepatitis B surface antibody; anti-HBc hepatitis B core antibody; HBV DNA hepatitis B virus deoxyribonucleic acid; anti-HCV hepatitis C antibody; HCV RNA hepatitis C virus ribonucleic acid ; anti-HDV, hepatitis D antibody; HDV RNA hepatitis D virus ribonucleic acid.

Among 155 HBsAg carriers, 126 (81.3%) subjects had detectable HBV DNA. HBV viremic subjects had significantly lower rates of anti-HCV and anti-HDV seropositivity than those with undetectable HBV DNA (anti-HCV positive rate: 29.4% vs 65.5%, p = 2.6 × 10–4; anti-HDV positive rate: 20.6% vs 44.8%, p = 0.007) (Table 2).

Multivariate regression analysis showed HBsAg seropositivity was negatively associated with supposed HCV viremia among all subjects (adjusted OR = 0.29, 95% CI = 0.16–0.53, p = 5.5 × 10–5). HBV/HCV dual infections had significantly lower rate of HBV viremia among HBsAg-seropositive subjects (adjusted OR = 0.27, 95% CI = 0.10–0.73, p = 0.010) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariate regression analysis of factors associated with hepatitis B infection.

| OR | 95% CI | Adjusted p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HBsAg seropositivity among all subjects | |||

| Age (before 1986 vs after 1986) | 0.00 | 0.00- | 0.999 |

| FIB-4 | 1.14 | 0.82–1.60 | 0.432 |

| Supposed HCV RNA (positive vs negative) | 0.29 | 0.16–0.53 | 5.5 × 10–5 |

| HBV viremia among HBsAg (+) subjects | |||

| Anti-HCV (positive vs negative) | 0.27 | 0.10–0.73 | 0.010 |

| Anti-HDV (positive vs negative) | 0.68 | 0.25–1.87 | 0.454 |

p.s. Supposed HCV RNA seropositivity included HCV viremia subjects and HCV non-viremia subjects induced by antiviral therapy.

HBsAg hepatitis B surface antigen; FIB-4 fibrosis-4 index; anti-HCV hepatitis C antibody; anti-HDV hepatitis D antibody.

Factors associated with HCV infection and HCV viremia

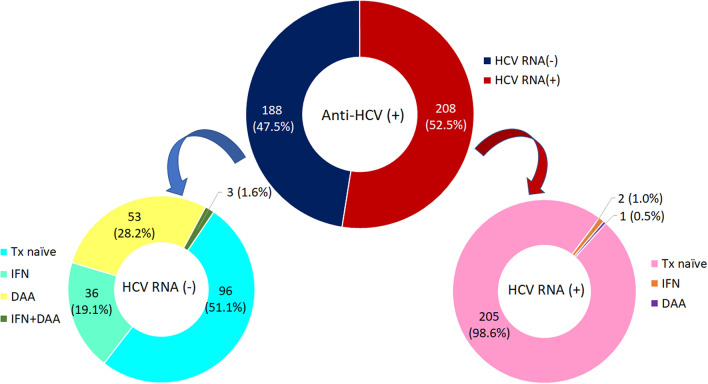

Among 396 anti-HCV positive subjects, 208 subjects had detectable HCV RNA (52.5%), including 3 subjects failed to prior antiviral therapy (interferon n = 2, DAA n = 1). Of 188 HCV non-viremic subjects, 92 subjects (48.9%) were treatment-induced, and 96 subjects (51.1%) were considered spontaneously HCV recovery. Fifty-three subjects (28.2%) were treated with DAA, 36 subjects (19.1%) were treated with interferon, and 3 (1.6%) with DAA after failed to interferon (Fig. 1) The predominant HCV genotype (GT) was GT6 (40.9%), followed by GT1a (24.0%), GT3 (11.1%), GT1b (10.6%), and GT2 (10.1%) (Supplementary Fig. S3).

Figure 1.

History of treatment among anti-HCV seropositive subjects.

In univariate analysis, age, levels of AST, ALT, and Fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) index, the proportion of IDU, anti-HBc, and anti-HDV-seropositivity in HBsAg carriers were significantly higher in anti-HCV-seropositive subjects than in anti-HCV-negative subjects. Among HBsAg-seropositive subjects, the proportion of HBV viremia was significantly lower in anti-HCV seropositive subjects than in anti-HCV-seronegative subjects (66.1% vs 89.9%, p = 2.6 × 10–4). Of 396 anti-HCV-seropositive subjects, the levels of AST, ALT and FIB-4 were significantly higher, but body mass index (BMI) and HBsAg-seropositive rate were significantly lower in the HCV viremia subjects than in those of HCV non-viremic, whatever spontaneous loss of HCV RNA or eradicated by antiviral therapy (Table 4).

Table 4.

Factors associated with HCV exposure and HCV viremia.

| All (n = 1,137) | Anti-HCV (+) (n = 396) | Treatment naïve Anti-HCV (+) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-HCV (+) | Anti-HCV (−) | p-value | HCV RNA (+) | HCV RNA (−) | p-value | HCV RNA (+) | HCV RNA (−) Spontaneous loss | p-value | |

| n | 396(34.8%) | 741(65.2%) | 208(52.5%) | 188(47.5%) | 205(68.1%) | 96(31.9%) | |||

| Age | 47.8 ± 8.2 | 44.1 ± 10.0 | 6.8 × 10–11 | 48.2 ± 8.4 | 47.3 ± 8.0 | 0.261 | 48.1 ± 8.4 | 47.4 ± 8.0 | 0.468 |

| Sex | |||||||||

| Male | 396(100%) | 734(99.1%) | 0.103 | 208(100%) | 188(100%) | N/A | 205(100%) | 96(100%) | N/A |

| Female | 0 (0.0%) | 7 (0.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0(0.0%) | 0(0.0%) | |||

| AST(IU/ml) | 32.5 ± 23.1 | 23.0 ± 9.7 | 4.0 × 10–14 | 41.1 ± 27.7 | 22.9 ± 10.4 | 1.4 × 10–16 | 41.0 ± 27.8 | 23.7 ± 13.0 | 1.7 × 10–12 |

| ALT(IU/ml) | 42.6 ± 41.2 | 26.8 ± 19.6 | 1.8 × 10–12 | 59.4 ± 48.4 | 24.1 ± 18.2 | 1.7 × 10–19 | 59.0 ± 48.5 | 27.0 ± 21.3 | 3.5 × 10–14 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.0 ± 3.2 | 24.3 ± 3.6 | 0.252 | 23.7 ± 3.2 | 24.3 ± 3.1 | 0.046 | 23.7 ± 3.2 | 25.0 ± 3.2 | 0.001 |

| FIB-4 | 1.22 ± 0.82 | 0.80 ± 0.41 | 2.2 × 10–20 | 1.32 ± 0.87 | 1.12 ± 0.74 | 0.015 | 1.32 ± 0.87 | 1.06 ± 0.59 | 0.003 |

| IDU | |||||||||

| Yes | 389(98.2%) | 625(84.3%) | 6.9 × 10–13 | 203(97.6%) | 186(98.9%) | 0.453 | 200(97.6%) | 96(100%) | 0.182 |

| No | 7(1.8%) | 116(15.7%) | 5(2.4%) | 2(1.1%) | 5(2.4%) | 0(0.0%) | |||

| HBsAg | |||||||||

| Positive | 56(14.1%) | 99(13.4%) | 0.715 | 21(10.1%) | 35(18.6%) | 0.015 | 21(10.2%) | 26(27.1%) | 1.8 × 10–4 |

| Negative | 340 (85.9%) | 642(86.6%) | 187(89.9%) | 153(81.4%) | 184(89.8%) | 70(72.9%) | |||

| HBeAg in HBsAg (+) subjects | |||||||||

| Positive | 5(8.9%) | 10(10.1%) | 0.813 | 2(9.5%) | 3(8.6%) | 1.000 | 2(9.5%) | 3(11.5%) | 1.000 |

| Negative | 51(91.1%) | 89(89.9%) | 19(90.5%) | 32(91.4%) | 19(90.5%) | 23(88.5%) | |||

| Anti-HBe in HBsAg (+) subjects | |||||||||

| Positive | 47(83.9%) | 91(91.9%) | 0.126 | 18(85.7%) | 29(82.9%) | 1.000 | 18(85.7%) | 21(80.8%) | 0.715 |

| Negative | 9(16.1%) | 8 (8.1%) | 3(14.3%) | 6(17.1%) | 3(14.3%) | 5(19.2%) | |||

| Anti-HBs | |||||||||

| Positive | 238(60.1%) | 424(57.5%) | 0.403 | 129(62.0%) | 109(58.0%) | 0.412 | 127(62.0%) | 52(54.2%) | 0.200 |

| Negative | 158(39.9%) | 313(42.5%) | 79(38.0%) | 79(42.0%) | 78((38.0%) | 44(45.8%) | |||

| Anti-HBc | |||||||||

| Positive | 324(82.0%) | 457(62.0%) | 3.9 × 10–12 | 175(84.1%) | 149(79.7%) | 0.250 | 172(83.9%) | 79(83.2%) | 0.871 |

| Negative | 71(18.0%) | 280(38.0%) | 33(15.9%) | 38(20.3%) | 33(16.1%) | 16(16.8%) | |||

| HBV DNA in HBsAg (+) subjects | |||||||||

| Mean ± SD (log IU/ml) | 2.30 ± 2.07 | 3.29 ± 1.87 | 0.003 | 1.82 ± 2.10 | 2.59 ± 2.03 | 0.178 | 1.82 ± 2.10 | 2.85 ± 2.02 | 0.093 |

| Positive | 37(66.1%) | 89(89.9%) | 2.6 × 10–4 | 12(57.1%) | 25(71.4%) | 0.274 | 12(57.1%) | 20(76.9%) | 0.148 |

| Negative | 19(33.9%) | 10(10.1%) | 9(42.9%) | 10(28.6%) | 9(42.9%) | 6(23.1%) | |||

| Anti-HDV in HBsAg (+) subjects | |||||||||

| Positive | 32(57.1%) | 7(7.1%) | 5.1 × 10–12 | 10(47.6%) | 22(62.9%) | 0.265 | 10(47.6%) | 17(65.4%) | 0.221 |

| Negative | 24(42.9%) | 92(92.9%) | 11(52.4%) | 13(37.1%) | 11(52.4%) | 9(34.6%) | |||

| HDV RNA in anti-HDV (+) subjects | |||||||||

| Positive | 18(56.3%) | 3(42.9%) | 0.682 | 4(40.0%) | 14(63.6%) | 0.267 | 4(40.0%) | 12(70.6%) | 0.224 |

| Negative | 14(43.8%) | 4(57.1%) | 6(60.0%) | 8(36.4%) | 6(60.0%) | 5(29.4%) | |||

HCV hepatitis C virus; Anti-HCV hepatitis C antibody; HCV RNA hepatitis C ribonucleic acid ; AST aspartate aminotransferase; ALT alanine aminotransferase; BMI body mass index; FIB-4 Fibrosis-4 index; IDU injecting drug user; HBsAg hepatitis B surface antigen; HBeAg hepatitis B envelope antigen; anti-HBe hepatitis B envelop antibody; anti-HBs hepatitis B surface antibody; anti-HBc hepatitis B core antibody; HBV DNA hepatitis B virus deoxyribonucleic acid; anti-HDV, hepatitis D antibody; HDV RNA hepatitis D virus ribonucleic acid.

p.s. Supposed HCV RNA seropositivity included HCV viremia subjects and HCV non-viremia subjects induced by antiviral therapy.

In multivariate regression analysis, IDU (adjusted OR = 18.45, 95% CI = 1.41–241.76, p = 0.026) and anti-HDV seropositivity (adjusted OR = 12.25, 95% CI = 4.85–30.93, p = 1.1 × 10–7) was positively associated with anti-HCV seropositivity. HBV viremia was negatively associated with anti-HCV seropositivity (adjusted OR = 0.31, 95% CI = 0.11–0.86, p = 0.024). BMI and HBsAg seropositivity were significantly negatively correlated with HCV viremia, whatever among all anti-HCV-seropositive subjects or among treatment-naïve anti-HCV-seropositive subjects (Table 5).

Table 5.

Multivariate regression analysis of factors associated with HCV infection.

| OR | 95% CI | Adjusted p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-HCV seropositivity among all subjects | |||

| Age | 0.98 | 0.92–1.04 | 0.543 |

| AST | 1.03 | 0.94–1.12 | 0.520 |

| ALT | 1.00 | 0.96–1.05 | 0.996 |

| FIB-4 | 1.02 | 0.45–2.33 | 0.955 |

| IDU (yes vs no) | 18.45 | 1.41–241.76 | 0.026 |

| Anti-HBc (positive vs negative) | 0.00 | 0.00- | 1.000 |

| HBV DNA (positive vs negative) | 0.31 | 0.11–0.86 | 0.024 |

| Anti-HDV (positive vs negative) | 12.25 | 4.85–30.93 | 1.1 × 10–7 |

| HCV viremia among anti-HCV (+) subjects | |||

| AST | 1.03 | 0.97–1.09 | 0.363 |

| ALT | 1.05 | 1.02–1.08 | 0.002 |

| BMI | 0.89 | 0.83–0.97 | 0.004 |

| FIB-4 | 0.66 | 0.43–1.01 | 0.056 |

| HBsAg (positive vs negative) | 0.42 | 0.21–0.85 | 0.016 |

| HCV viremia among treatment naïve anti-HCV (+) subjects | |||

| AST | 1.02 | 0.95–1.10 | 0.605 |

| ALT | 1.04 | 1.00–1.08 | 0.060 |

| BMI | 0.86 | 0.79–0.94 | 0.001 |

| FIB-4 | 0.84 | 0.44–1.60 | 0.589 |

| HBsAg (positive vs negative) | 0.27 | 0.13–0.58 | 6.9 × 10–4 |

HCV hepatitis C virus; anti-HCV hepatitis C antibody; AST aspartate aminotransferase; ALT alanine aminotransferase; BMI body mass index; FIB-4 Fibrosis-4 index; IDU injecting drug users; HBsAg hepatitis B surface antigen; anti-HBc hepatitis B core antibody; HBV DNA hepatitis B virus deoxyribonucleic acid; anti-HDV hepatitis D antibody.

Factors associated with HDV infection and HDV viremia

Among the HBsAg carriers, none of anti-HDV-seropositive subjects was born after 1986. In univariate analysis, IDU (100% vs 81.9%, p = 0.002) and the anti-HCV positive rate (82.1% vs 20.7%, p = 5.2 × 10–12) were significantly higher, whereas the HBV DNA level was significantly lower (2.10 ± 1.79 vs 3.22 ± 1.99 log10IU/ml, p = 0.002) in HBV/HDV dual infected subjects than in HBV mono-infected subjects. Multivariate regression analysis showed that anti-HCV seropositivity was significantly higher risk of anti-HDV-seropositivity among HBsAg carriers (adjusted OR = 15.73, 95% CI = 6.04–40.96, p = 1.7 × 10–8).

Among 39 HBV/HDV dual infected subjects, 21 (53.8%) had detectable HDV RNA. Among 26 HBV/HDV dual infected subjects with HBV viremia, 16 (61.5%) had detectable HDV RNA. None of the factors listed in Table 6 was associated with HDV viremia in both groups.

Table 6.

Factors associated with HDV exposure and HDV viremia among HBV carriers.

| HBsAg (+) | HBsAg (+) & Anti-HDV (+) | HBV DNA (+) & anti-HDV (+) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-HDV (+) | Anti-HDV (−) | p-value | HDV RNA (+) | HDV RNA (−) | p-value | HDV RNA (+) | HDV RNA (−) | p-value | |

| n | 39(25.2%) | 116(74.8%) | 21(53.8%) | 18(46.2%) | 16(61.5%) | 10(38.5%) | |||

| Age | |||||||||

| Mean ± SD | 47.7 ± 7.3 | 45.5 ± 7.4 | 0.108 | 47.5 ± 7.5 | 48.0 ± 7.3 | 0.843 | 47.7 ± 7.8 | 47.2 ± 7.0 | 0.873 |

| Before 1986 | 39(100%) | 116(100%) | N/A | 21(100%) | 18(100%) | N/A | 16(100%) | 10(100%) | N/A |

| After 1986 | 0(0.0%) | 0(0.0%) | 0(0.0%) | 0(0.0%) | 0(0.0%) | 0(0.0%) | |||

| Sex | |||||||||

| Male | 39(100%) | 115(99.1%) | 1.000 | 21(100%) | 18(100%) | N/A | 16(100%) | 10(100%) | N/A |

| Female | 0(0.0%) | 1(0.9%) | 0(0.0%) | 0(0.0%) | 0(0.0%) | 0(0.0%) | |||

| AST (IU/ml) | 29.1 ± 15.4 | 27.7 ± 13.8 | 0.606 | 29.0 ± 13.9 | 29.3 ± 17.3 | 0.948 | 26.6 ± 11.8 | 29.2 ± 22.3 | 0.703 |

| ALT (IU/ml) | 34.8 ± 25.8 | 35.1 ± 25.9 | 0.949 | 35.3 ± 25.6 | 34.3 ± 26.8 | 0.905 | 32.1 ± 22.3 | 34.2 ± 31.3 | 0.840 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.3 ± 3.1 | 23.7 ± 2.9 | 0.276 | 24.0 ± 3.0 | 24.5 ± 3.3 | 0.639 | 23.5 ± 2.6 | 24.6 ± 3.0 | 0.361 |

| FIB-4 | 1.32 ± 1.20 | 1.02 ± 0.62 | 0.140 | 1.43 ± 1.54 | 1.20 ± 0.64 | 0.566 | 1.09 ± 0.51 | 1.06 ± 0.63 | 0.892 |

| IDU | |||||||||

| Yes | 39(100%) | 95(81.9%) | 0.002 | 21(100%) | 18(100%) | N/A | 16(100%) | 10(100%) | N/A |

| No | 0(0.0%) | 21(18.1%) | 0(0.0%) | 0(0.0%) | 0(0.0%) | 0(0.0%) | |||

| NUC (n, %) | 1(2.6%) | 5(4.3%) | 1.000 | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (5.6%) | 0.462 | 0 (0.0%) | 1(10.0%) | 0.385 |

| HBeAg | |||||||||

| Positive | 2(5.1%) | 13(11.2%) | 0.359 | 2(9.5%) | 0(0.0%) | 0.490 | 1(6.3%) | 0(0.0%) | 1.000 |

| Negative | 37(94.9%) | 103(88.8%) | 19(90.5%) | 18(100%) | 15(93.7%) | 10(100%) | |||

| Anti-HBe | |||||||||

| Positive | 35(89.7%) | 103(88.8%) | 1.000 | 17(81.0%) | 18(100%) | 0.110 | 13(81.3%) | 10(100%) | 0.262 |

| Negative | 4(10.3%) | 13(11.2%) | 4(19.0%) | 0(0.0%) | 3(18.7%) | 0(0.0%) | |||

| Anti-HBs | |||||||||

| Positive | 0(0.0%) | 5(4.3%) | 0.331 | 0(0.0%) | 0(0.0%) | N/A | 0(0.0%) | 0(0.0%) | N/A |

| Negative | 39(100%) | 111(95.7%) | 21(100%) | 18(100%) | 16(100%) | 10(100%) | |||

| Anti-HBc | |||||||||

| Positive | 39(100%) | 115(99.1%) | 1.000 | 21(100%) | 18(100%) | N/A | 16(100%) | 10(100%) | N/A |

| Negative | 0(0.0%) | 1(0.9%) | 0(0.0%) | 0(0.0%) | 0(0.0%) | 0(0.0%) | |||

| HBV DNA | |||||||||

| Mean ± SD (log IU/ml) | 2.10 ± 1.79 | 3.22 ± 1.99 | 0.002 | 2.25 ± 1.65 | 1.92 ± 1.98 | 0.578 | 2.95 ± 1.19 | 3.46 ± 1.23 | 0.305 |

| Positive | 26(66.7%) | 100(86.2%) | 0.007 | 16(76.2%) | 10(55.6%) | 0.173 | 16(100%) | 10(100%) | N/A |

| Negative | 13(33.3%) | 16(13.8%) | 5(23.8%) | 8(44.4%) | 0(0.0%) | (0.0%) | |||

| Anti-HCV | |||||||||

| Positive | 32(82.1%) | 24(20.7%) | 5.2 × 10–12 | 18(85.7%) | 14(77.8%) | 0.682 | 13(81.3%) | 7(70.0%) | 0.644 |

| Negative | 7(17.9%) | 92(79.3%) | 3(14.3%) | 4(22.2%) | 3(18.7%) | 3(30.0%) | |||

| HCV RNA in anti-HCV (+) subjects | |||||||||

| Mean ± SD (log IU/ml) | 1.82 ± 2.81 | 2.91 ± 3.28 | 0.197 | 1.20 ± 2.37 | 2.62 ± 3.20 | 0.180 | 1.67 ± 2.66 | 1.58 ± 2.81 | 0.949 |

| Positive | 10(31.3%) | 11(45.8%) | 0.265 | 4(22.2%) | 6(42.9%) | 0.267 | 4(30.8%) | 2(28.6%) | 1.000 |

| Negative | 22(68.8%) | 13(54.2%) | 14(77.8%) | 8(57.1%) | 9(69.2%) | 5(71.4%) | |||

| Supposed HCV RNA in anti-HCV (+) subjects | |||||||||

| Positive | 15(46.9%) | 15(62.5%) | 0.246 | 6(33.3%) | 9(64.3%) | 0.082 | 5(38.5%) | 4(57.1%) | 0.642 |

| Negative | 17(53.1%) | 9(37.5%) | 12(66.7%) | 5(35.7%) | 8(61.5%) | 3(42.9%) | |||

| HCV genotype in HCV RNA (+) subjects | |||||||||

| 1a | 2(20.0%) | 3(27.3%) | 0.745 | 0(0.0%) | 2(33.3%) | 0.290 | 0(0.0%) | 0(0.0%) | 1.000 |

| 1b | 1(10.0%) | 1(9.1%) | 1(25.0%) | 0(0.0%) | 1(25.0%) | 0(0.0%) | |||

| 2 | 0(0.0%) | 0(0.0%) | 0(0.0%) | 0(0.0%) | 0(0.0%) | 0(0.0%) | |||

| 3 | 1(10.0%) | 0(0.0%) | 0(0.0%) | 1(16.7%) | 0(0.0%) | 0(0.0%) | |||

| 6 | 6(60.0%) | 7(63.6%) | 3(75.0%) | 3(50.0%) | 3(75.0%) | 2(100%) | |||

p.s. Supposed HCV RNA seropositivity included HCV viremia subjects and HCV non-viremia subjects induced by antiviral therapy.

HDV hepatitis D virus; anti-HDV hepatitis D antibody; HDV RNA hepatitis D virus ribonucleic acid; AST aspartate aminotransferase; ALT alanine aminotransferase; BMI body mass index; FIB-4 Fibrosis-4 index; IDU injecting drug user; NUC nucleotide analogue; HBsAg hepatitis B surface antigen; HBeAg hepatitis B envelope antigen; anti-HBe hepatitis B envelop antibody; anti-HBs hepatitis B surface antibody; anti-HBc hepatitis B core antibody; HBV DNA hepatitis B virus deoxyribonucleic acid; anti-HCV hepatitis C antibody; HCV RNA hepatitis C virus ribonucleic acid.

Discussion

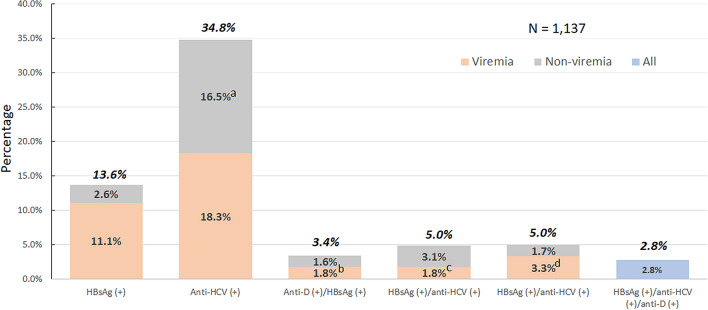

This study revealed the prevalence of hepatitis B, C, and D in Penghu Prison was 13.6%, 34.8%, 3.4%, respectively. IDU was significantly associated with HCV and HDV, but not HBV infection. The prevalence rates of HBV/HCV, HBV/HDV dual infections and HBV/HCV/HDV triple infections was 5%, 3.4% and 2.8%, respectively. The predominant HCV genotypes in IDUs were GT6 (40.9%), GT1a (24.0%) and GT3 (11.1%). The risk of HBV viremia was significantly reduced in the anti-HCV seropositive subjects. HBsAg seropositive and body mass index were negatively correlated with HCV viremia among the treatment naïve HCV subjects. Positive for anti-HCV antibody significantly increased the risk of HDV infection.

In Taiwan, the implementation of universal hepatitis B vaccination since 1986 has substantially decreased the HBsAg carrier rate from–15% to < 1% in young adult 6. This study showed the prevalence of hepatitis B among IDUs was similar to that of the general population. An outbreak of HIV infection among IDUs occurred in Taiwan between 2004 and 2006. In this outbreak, the HCV infection rate was up to 98% in HIV-infected IDUs, and some unprecedented HCV genotypes (e.g., 6 g, 6 k, 6w…) had been identified in Taiwan16. The prevalence of anti-HCV seropositive was not only extremely high in HIV-infected IDUs (98.7%) but also in HIV-uninfected IDUs (83%) 10. Elevated HDV seroprevalence among HBV carriers was simultaneously observed in both HIV-infected IDUs (74.9–84.2%) and HIV-uninfected IDUs (40.0–66.7%) 11, 12, 17 To avoid the spread of this epidemic, the Taiwan Centers for Disease Control (CDC) has implemented harm reduction project for IDUs since 2005. The core interventions include the disposable syringe practices, methadone maintenance treatment, HIV counseling, antiretroviral therapy, and public health education programs. Our study revealed the prevalence of HCV and HBV/HDV dual infection among the inmates in Penghu Prison had steadily declined to 34.8% and 25.2% in 2019 (Supplementary Fig. S4 and Table S1).

The superinfection of viral hepatitis among IDUs is common because of the same routes of transmission. Subjects with dual infection have a greater risk of advanced liver disease, cirrhosis and HCC compared with mono-infected subjects 18, 19. Our survey revealed the presence of HCV RNA significantly reduced the risk of HBsAg seropositive. Positive for anti-HCV antibody significantly decreased the risk of HBV viremia. In addition, HBV/HDV dual infected subjects had a less HBV DNA level compared with HBV mono-infected subjects. The previous studies revealed HCV exhibited stronger inhibitory action among the subjects with HBV/HCV dual infection20–22. HBV reactivation occurs frequently in HBV/HCV coinfected patients receiving DAA therapy but is rare among patients with resolved HBV infection20, 21. HDV appeared to be the predominant virus in either HBV/HDV dual infection or in HBV/HCV/HDV triple infection23, 24. The complex interplay among these viruses remains poorly understood. Some possible mechanism had been elucidated. (1) Direct inhibition HBV replication by HCV core protein; (2) Eradication of one virus provides available replication space for another; (3) Loss of host immune responses to one virus may improve replication of the other 25. Murai et al. found HCV infection suppresses HBV replication via the RIG-1 (retinoic acid-inducible gene-1) like helicase pathway26. MicroRNAs play a role in facilitation of HCV dominance as well. miR-122 can restrain HBV replication through cyclin G1-mediated P53 activity 27. In contrast, miR-122 stabilizes HCV genome by protecting the 5′ terminus of the HCV RNA from degradation by the host exonuclease 28. In addition, HDV can suppress HBV replication via inhibition the host DNA-dependent RNA polymerase involving HBV transcription 29. Small hepatitis delta antigen exerts a strong inhibition of HBV mRNAs synthesis or stability30, 31. HDV proteins inhibit HBV replication by repressing HBV enhancers and by activating the IFN-α-inducible MxA (myxovirus resistance A) gene32.

The distribution of HCV genotypes varies by risk groups and geographically. This study showed the predominant HCV genotypes among the inmates of Penghu Prison were GT6 (40.9%), followed by GT1a (24.0%), and GT3 (11.1%). The previous studies reported the proportion of HCV genotype 6 (28.0–43.4%), 1a (14.9–29.2%), and 3a (7.8–20.2%) was apparently higher among IDUs compared with the general population (GT6: 0–0.49%; GT1a: 0–2.7%; GT3a: 0–0.98%) in Taiwan3, 10, 16, 33, 34. Phylogenetic analysis revealed that these distinct subtypes were derived from the spread of HCV along the drug trafficking routes via Vietnam and Thailand35, 36. Genotype 1a was common among IDUs in Europe and America as well 37, 38. In general, the distribution of HCV genotypes among IDUs in Taiwan did not alter tremendously in the past fifteen years.

Dual and/or triple infections of HBV, HCV and/or HDV have been associated with poor long-term outcome39, 40. The estimated prevalence rate of anti-HDV was 4.5% among HBsAg-positive carriers and around 0.16% in general population with a total of 12 million people seropositive for anti-HDV worldwide39. However, there is no global estimate for HBV/HCV/HDV triple infections available. HCV infection has been associated with risk of HDV infection among HBV carriers in previous study as well as in the current study11, 39. Similar to previous study in general population and high-risk groups (PWID and/or HIV-positive patients) in Taiwan11, around 80% of HBV/HDV-infected subjects were seropositive for anti-HCV in the current study, with a 2.8% prevalence rate of HBV/HCV/HDV triple infections in the prisoners (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

The prevalence of HBV, HCV and HDV infection among prisoners. HBsAg hepatitis B virus surface antigen; anti-HCV antibodies to hepatitis C virus; anti-D antibodies to hepatitis D virus. Viremia indicates seropositive for each corresponding viral DNA or RNA. (a) 8.1% were treatment-induced non-viremic; (b) HDV viremia; (c) HCV viremia; d, HBV viremia.

In this study, 31.7% (95/300) chronic hepatitis C patient concomitant with HCV RNA seropositive had ever received antiviral therapy. The sustained virologic response rate was 87.8% (36/41) in interferon group and 98.2% (56/57) in DAA group, respectively. Asians have a higher likelihood of achieving an interferon-induced viral clearance than their Caucasians counterparts due to carriage of favorable interleukin-28 genotype41. With the recommended “standard interferon dose and duration regimens”, SVR is achieved in Asia for around 70% of HCV genotype 1 (GT1) infected cases, approximately 90% of GT2/3, 65% of GT4, and 80% of GT6 patients42. The treatment efficacy in HCV infected prisoners was comparable with that in the community cohort.

Although treatment efficacy of the DAA is excellent, there is still a wide gap between the awareness of hepatitis C and access to antiviral therapy among this high-risk population. Irrespective of coinfection with HIV or not, the carrier rate of viral hepatitis is still high among IDUs. In addition to HIV, we recommend the viral hepatitis markers should be examined routinely for all the incarcerated IDUs in Taiwan prisons. The incarcerated inmates may face numerous barriers to health care services. It is necessary to adopt integrated strategies to prevent intravenous drug use, and to assist subjects searching for medical care aggressively. Apart from medical service, social-economic support is important to prevent the incarcerated IDUs from reuse intravenous drugs after being released.

There are three major pillars for controlling the epidemic of viral hepatitis in this high-risk groups. Firstly, universal vaccination with HBV vaccine, which could provide protection from HBV and HDV infection for HBV-unexposed subjects43; secondly, education for avoiding percutaneous risk behaviors, such as abstinence of drugs, harm reduction with safe needles, and safe sex; thirdly, treatment as prevention. It is critical in particular for HCV control since there are no vaccine available. The concept of HCV micro-elimination could help prevent the spreading of HCV in the high-risk groups44. We recently approved the concept that an outreach screening program with onsite DAA treatment is the key toward HCV micro-elimination in uremic HCV patients under maintenance hemodialysis45, 46. Therefore, an outreach onsite HCV treatment program is proposed for HCV micro-elimination in the high risk setting.

There are limitations in our study. This was a cross-sectional study. It failed to find out the change of molecular epidemiology of hepatitis B, C and D over time. However, it is very difficult to follow the inmates when they are released or transferred. Since there is no HIV-infected subject in Penghu Prison, the results may not fully reflect the actual status of viral hepatitis among IDUs in Taiwan. Because of the highly coexistence between the viral hepatitis and HIV, the infection rate of viral hepatitis among IDUs may be underestimated.

Conclusion

This study revealed a marked decline in the prevalence of HBV, HCV, and HDV among HIV-uninfected IDUs over the past fifteen years in Taiwan. Although the universal HBV vaccination program and disposable syringe practices indeed prevent the spread of viral hepatitis, IDUs still emerge as a reservoir for viral hepatitis in Taiwan. Despite high efficacy DAAs been on the market for several years, there is a wide gap between awareness of viral hepatitis and antiviral therapy among IDUs. More effective public health policy is required to eliminate the epidemic in these high-risk groups.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

This work was partly funded by grants from Kaohsiung Medical University (grant No. KMU-DK107004; MOST 108-2314-B-037-066-MY3), Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital (grant No. KMUH-DK109005~1; KMUH-DK109002; KMUH-108-8R05), Center for Cancer Research of Kaohsiung Medical University (grant No.KMU-TC108A04-3), Liquid Biopsy and Cohort Research Center of Kaohsiung Medical University (grant No.KMU-TC109B05) and Taiwan Liver Research Foundation.

Author contributions

M.Y.L. analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. C.T.C., Y.L.S., M.H.H., C.F.H., M.L.Y., C.I.H., Y.J.W., P.Y.H., C.T.H., T.Y.J., T.W.L., P.C.L., M.Y.H., Z.Y.L., S.C.C., J.F.H., C.Y.D., W.L.C. and W.Y.C. collected the clinical data. S.C.W., Y.S.T., Y.M.K., C.C.L., and K.Y.C. performed the experiments. P.C.T. confirmed the statistical analysis. M.L.Y. designed the study, interpreted data, and supervised the manuscript. All authors have reviewed the manuscript.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-021-87975-5.

References

- 1.Yang JF, et al. Viral hepatitis infections in southern Taiwan: A multicenter community-based study. Kaohsiung J. Med. Sci. 2010;26:461–469. doi: 10.1016/S1607-551X(10)70073-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yu ML, et al. Huge gap between clinical efficacy and community effectiveness in the treatment of chronic hepatitis C: A nationwide survey in Taiwan. Medicine. 2015;94:e690. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000000690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yu ML, et al. Changing prevalence of hepatitis C virus genotypes: molecular epidemiology and clinical implications in the hepatitis C virus hyperendemic areas and a tertiary referral center in Taiwan. J. Med. Virol. 2001;65:58–65. doi: 10.1002/jmv.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rizzetto M, et al. delta Agent: association of delta antigen with hepatitis B surface antigen and RNA in serum of delta-infected chimpanzees. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1980;77:6124–6128. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.10.6124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miao Z, et al. Estimating the global prevalence, disease progression, and clinical outcome of hepatitis delta virus infection. J Infect. Dis. 2020;221:1677–1687. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiz633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ni YH, et al. Continuing decrease in hepatitis B virus infection 30 years after initiation of infant vaccination program in Taiwan. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016;14:1324–1330. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang CF, et al. Direct-acting antivirals in East Asian hepatitis C patients: Real-world experience from the REAL-C Consortium. Hepatol. Int. 2019;13:587–598. doi: 10.1007/s12072-019-09974-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yu ML. Hepatitis C treatment from "response-guided" to "resource-guided" therapy in the transition era from interferon-containing to interferon-free regimens. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017;32:1436–1442. doi: 10.1111/jgh.13747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee HC, Ko NY, Lee NY, Chang CM, Ko WC. Seroprevalence of viral hepatitis and sexually transmitted disease among adults with recently diagnosed HIV infection in Southern Taiwan, 2000–2005: Upsurge in hepatitis C virus infections among injection drug users. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2008;107:404–411. doi: 10.1016/S0929-6646(08)60106-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hsieh MH, et al. Hepatitis C virus infection among injection drug users with and without human immunodeficiency virus co-infection. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e94791. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin HH, et al. Changing hepatitis D virus epidemiology in a hepatitis B virus endemic area with a national vaccination program. Hepatology. 2015;61:1870–1879. doi: 10.1002/hep.27742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hsieh MH, et al. Hepatitis D virus infections among injecting drug users with and without human immunodeficiency virus infection in Taiwan. Kaohsiung J. Med. Sci. 2016;32:526–530. doi: 10.1016/j.kjms.2016.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yeh ML, et al. Comparison of the Abbott RealTime HBV assay with the Roche Cobas AmpliPrep/Cobas TaqMan HBV assay for HBV DNA detection and quantification. J. Clin. Virol. 2014;60:206–214. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2014.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vermehren J, et al. Multi-center evaluation of the Abbott RealTime HCV assay for monitoring patients undergoing antiviral therapy for chronic hepatitis C. J. Clin. Virol. 2011;52:133–137. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2011.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jang TY, et al. Serial serologic changes of hepatitis D virus in chronic hepatitis B patients receiving nucleos(t)ides analogues therapy. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020 doi: 10.1111/jgh.15061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu JY, et al. Extremely high prevalence and genetic diversity of hepatitis C virus infection among HIV-infected injection drug users in Taiwan. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2008;46:1761–1768. doi: 10.1086/587992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chang SY, et al. Molecular epidemiology of hepatitis D virus infection among injecting drug users with and without human immunodeficiency virus infection in Taiwan. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2011;49:1083–1089. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01154-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kawagishi N, et al. Comparing the risk of hepatitis B virus reactivation between direct-acting antiviral therapies and interferon-based therapies for hepatitis C. J. Viral Hepat.. 2017;24:1098–1106. doi: 10.1111/jvh.12737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Romeo R, et al. High serum levels of HDV RNA are predictors of cirrhosis and liver cancer in patients with chronic hepatitis delta. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e92062. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yeh ML, et al. Hepatitis B-related outcomes following direct-acting antiviral therapy in Taiwanese patients with chronic HBV/HCV co-infection. J. Hepatol. 2020;73:62–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2020.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mucke MM, et al. Hepatitis B virus reactivation during direct-acting antiviral therapy for hepatitis C: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018;3:172–180. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(18)30002-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Holmes JA, Yu ML, Chung RT. Hepatitis B reactivation during or after direct acting antiviral therapy: Implication for susceptible individuals. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2017;16:651–672. doi: 10.1080/14740338.2017.1325869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jardi R, et al. Role of hepatitis B, C, and D viruses in dual and triple infection: influence of viral genotypes and hepatitis B precore and basal core promoter mutations on viral replicative interference. Hepatology. 2001;34:404–410. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.26511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mathurin P, et al. Replication status and histological features of patients with triple (B, C, D) and dual (B, C) hepatic infections. J. Viral Hepat. 2000;7:15–22. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2893.2000.00195.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abdelaal R, Yanny B, El Kabany M. HBV/HCV Coinfection in the Era of HCV-DAAs. Clin. Liver Dis. 2019;23:463–472. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2019.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murai K, et al. Hepatitis C virus infection suppresses hepatitis B virus replication via the RIG-I-like helicase pathway. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:941. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-57603-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang S, et al. Loss of microRNA 122 expression in patients with hepatitis B enhances hepatitis B virus replication through cyclin G(1) -modulated P53 activity. Hepatology. 2012;55:730–741. doi: 10.1002/hep.24809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li Y, Masaki T, Yamane D, McGivern DR, Lemon SM. Competing and noncompeting activities of miR-122 and the 5' exonuclease Xrn1 in regulation of hepatitis C virus replication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:1881–1886. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1213515110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Modahl LE, Lai MM. The large delta antigen of hepatitis delta virus potently inhibits genomic but not antigenomic RNA synthesis: a mechanism enabling initiation of viral replication. J. Virol.. 2000;74:7375–7380. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.16.7375-7380.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sureau C, Negro F. The hepatitis delta virus: Replication and pathogenesis. J. Hepatol. 2016;64:S102–S116. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu JC, et al. Production of hepatitis delta virus and suppression of helper hepatitis B virus in a human hepatoma cell line. J. Virol. 1991;65:1099–1104. doi: 10.1128/JVI.65.3.1099-1104.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Williams V, et al. Hepatitis delta virus proteins repress hepatitis B virus enhancers and activate the alpha/beta interferon-inducible MxA gene. J. Gen. Virol. 2009;90:2759–2767. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.011239-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee YM, et al. Molecular epidemiology of HCV genotypes among injection drug users in Taiwan: Full-length sequences of two new subtype 6w strains and a recombinant form_2b6w. J. Med. Virol. 2010;82:57–68. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yu ML, et al. The genotypes of hepatitis C virus in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection in southern Taiwan. Kaohsiung J. Med. Sci. 1996;12:605–612. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Simmonds P, et al. Evolutionary analysis of variants of hepatitis C virus found in South-East Asia: comparison with classifications based upon sequence similarity. J. Gen. Virol. 1996;77(Pt 12):3013–3024. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-77-12-3013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hansurabhanon T, et al. Infection with hepatitis C virus among intravenous-drug users: prevalence, genotypes and risk-factor-associated behaviour patterns in Thailand. Ann. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 2002;96:615–625. doi: 10.1179/000349802125001465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van Asten L, et al. Spread of hepatitis C virus among European injection drug users infected with HIV: A phylogenetic analysis. J. Infect. Dis. 2004;189:292–302. doi: 10.1086/380821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McMahon BJ, et al. Epidemiology and risk factors for hepatitis C in Alaska Natives. Hepatology. 2004;39:325–332. doi: 10.1002/hep.20046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stockdale AJ, et al. The global prevalence of hepatitis D virus infection: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Hepatol. 2020;73:523–532. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2020.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jang TY, et al. Role of hepatitis D virus in persistent alanine aminotransferase abnormality among chronic hepatitis B patients treated with nucleotide/nucleoside analogues. J. Formos Med. Assoc. 2021;120:303–310. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2020.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huang CF, et al. Host interleukin-28B genetic variants versus viral kinetics in determining responses to standard-of-care for Asians with hepatitis C genotype 1. Antiviral Res. 2012;93:239–244. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2011.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yu ML, Chuang WL. Treatment of chronic hepatitis C in Asia: when East meets West. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2009;24:336–345. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.05789.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ni YH, et al. Minimization of hepatitis B infection by a 25-year universal vaccination program. J. Hepatol. 2012;57:730–735. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lazarus JV, et al. The Micro-Elimination Approach To Eliminating Hepatitis C: Strategic and operational considerations. Semin. Liver Dis. 2018;38:181–192. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1666841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Huang CF, Chiu YW, Yu ML. Patient-centered outreach treatment toward micro-elimination of hepatitis C virus infection in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2020;97:421. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2019.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yu ML, et al. Establishment of an outreach, grouping healthcare system to achieve microelimination of HCV for uremic patients in haemodialysis centres (ERASE-C) Gut. 2020 doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-323277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.