Abstract

How does the human brain integrate spatial and temporal information into unified mnemonic representations? Building on classic theories of feature binding, we first define the oscillatory signatures of integrating ‘where’ and ‘when’ information in working memory (WM) and then investigate the role of prefrontal cortex (PFC) in spatiotemporal integration. Fourteen individuals with lateral PFC damage and 20 healthy controls completed a visuospatial WM task while electroencephalography (EEG) was recorded. On each trial, two shapes were presented sequentially in a top/bottom spatial orientation. We defined EEG signatures of spatiotemporal integration by comparing the maintenance of two possible where-when configurations: the first shape presented on top and the reverse. Frontal delta-theta (δθ; 2-7 Hz) activity, frontal-posterior δθ functional connectivity, lateral posterior event-related potentials, and mesial posterior alpha phase-to-gamma amplitude coupling dissociated the two configurations in controls. WM performance and frontal and mesial posterior signatures of spatiotemporal integration were diminished in PFC lesion patients, whereas lateral posterior signatures were intact. These findings reveal both PFC-dependent and independent substrates of spatiotemporal integration and link optimal performance to PFC.

Keywords: cross-frequency coupling, functional connectivity, oscillations, prefrontal cortex (PFC), spatiotemporal integration, working memory (WM)

1. Introduction

We continuously update our memories as we move through the world. Working memory (WM) provides the neurocognitive workspace in which this influx of information is integrated and maintained (A. Baddeley, 2012; A. D. Baddeley, Allen, & Hitch, 2011; A. Baddeley & Della Sala, 1996; Bays, Wu, & Husain, 2011; Brown & Brockmole, 2010; Parra, Della Sala, Logie, & Morcom, 2014; Sala & Courtney, 2007). Most literature on the neural basis of WM is focused on maintaining and manipulating items. However, real-world mnemonic representations of ‘what’ happened (typically operationalized by items) are also defined by information about ‘where’ and ‘when’, and this information is updated constantly (Johnson, Adams, et al., 2018; Johnson, King-Stephens, et al., 2018). Understanding how the brain integrates the constant influx of spatial and temporal information into unified mnemonic representations is fundamental to the neuroscience of perception and cognition.

To address this core issue in human behavior, we turned to two dominant theories of visuospatial feature binding: feature integration (FIT) and binding-by-synchrony (BBS). These theories characterize how different features (e.g., color and shape) could be processed in different regions of the brain yet perceived as unified representations (colored shape) – the ‘feature binding problem’.

According to FIT, features are separated early in the visual process and then integrated via orienting attention to their relationship (Golomb, L’Heureux, & Kanwisher, 2014; Katzner, Busse, & Treue, 2006; Schoenfeld et al., 2003; A. Treisman, 1998; A. M. Treisman & Gelade, 1980). Empirical support for FIT comes from psychophysical and neuroimaging investigations implicating brain regions associated with spatial attention, including prefrontal, temporal, and parietal cortices (Ashbridge, Cowey, & Wade, 1999; Colby & Goldberg, 1999; Corbetta, Shulman, Miezin, & Petersen, 1995; Friedman-Hill, Robertson, & Treisman, 1995; Libby, Hannula, & Ranganath, 2014; Olson, Page, Moore, Chatterjee, & Verfaellie, 2006; Parra et al., 2014; L. C. Robertson, 2003; Shafritz, Gore, & Marois, 2002; Zokaei et al., 2019). Further, event-related potential (ERP) studies have tracked the frontal scalp N200 component, showing increased attention allocation during feature binding relative to control conditions (Hyun, Woodman, & Luck, 2009; Luck & Hillyard, 1994; R. Näätänen, Paavilainen, Rinne, & Alho, 2007; Risto Näätänen, 1982). Additional support comes from studies of patients with lesions to prefrontal or parietal areas, who exhibit diminished feature integration behavior (Friedman-Hill et al., 1995; Voytek, Soltani, Pickard, Kishiyama, & Knight, 2012).

According to BBS, different features are integrated through synchronous activity among regions of the occipital cortex (Eckhorn et al., 1988; Gray, König, Engel, & Singer, 1989; König, Engel, & Singer, 1995; Shadlen & Movshon, 1999; Wu, Chen, Li, Han, & Zhang, 2007; Zhou et al., 2019). Specifically, synchrony in the gamma band between early visual regions is one purported mechanism of feature integration. Further empirical support for BBS comes from neurophysiological studies showing evidence of orientation integration in non-human primate V1 neurons (Gray et al., 1989) and multisensory integration in human EEG (Yuval-Greenberg & Deouell, 2007). Thus, FIT points to top-down control from higher-level association cortices and BBS to synchrony among lower-level visual areas.

Here, we critically extend the classic ‘feature binding problem’ from perception to the integration of information over time, a second-order ‘integration problem’ which depends on WM. We hypothesized that both FIT and BBS would apply to the real-world task of integrating visuospatial information over time, reflected in synchronous activity between regions associated with top-down control, such as prefrontal cortex (PFC), and distinct activity in posterior visual regions. To test this hypothesis, we analyzed electroencephalography (EEG) data from a study conducted in a large cohort of patients with discrete PFC lesions that required the rapid integration of spatial and temporal information in single trials (Fig. 1A) (Johnson et al., 2017). On each trial, two colored shapes were presented sequentially in a top/bottom spatial orientation and the pair of shapes was defined by their spatiotemporal relationship. A test cue was presented mid-delay to cue one of four spatiotemporal features of the shape pair being maintained in WM; on identity control trials, the cue “same” indicated ongoing maintenance of what the shapes looked like. We used this neurological dataset given the documented attenuation of a PFC-sourced oscillatory mechanism for top-down control in PFC patients relative to controls (Johnson et al., 2017).

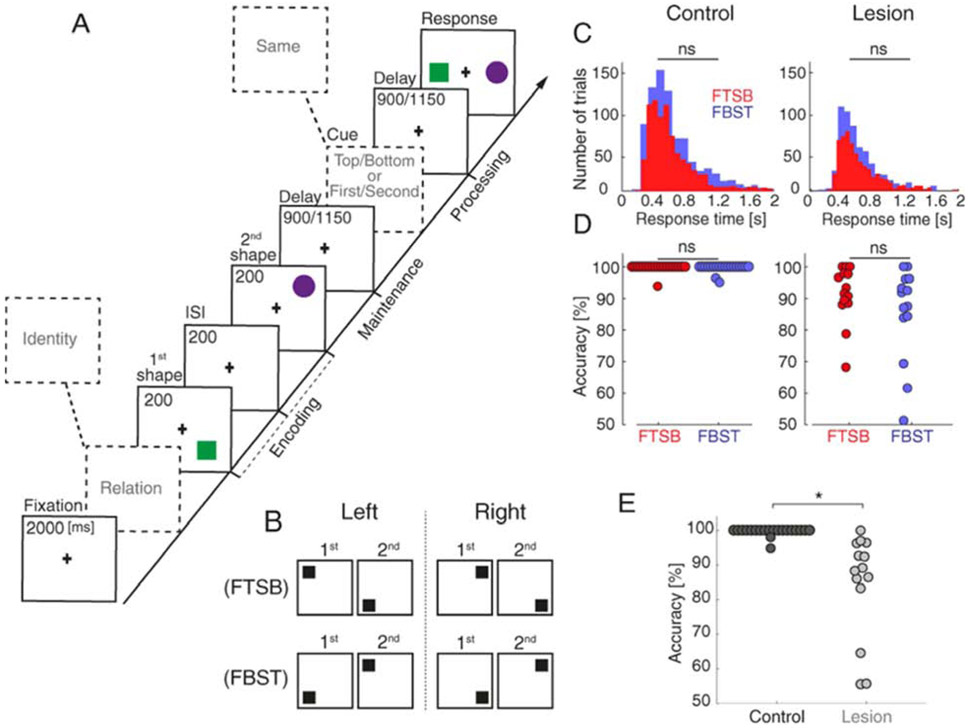

Figure 1. Spatiotemporal integration task and behavior.

A) WM task. At encoding, two shapes were presented sequentially (200-ms each, 200-ms ISI) in a top/bottom spatial orientation. After a randomly jittered 900/1150-ms maintenance interval during which both spatial and temporal information defined the pair (spatiotemporal relation trials; analyzed here), subjects were cued to identify which shape had been presented in the top/bottom/first/second position. In one third of trials, subjects were cued to continue maintaining a representation of what the shapes looked like (identity control trials; not analyzed). WM was tested in a two-alternative forced choice test.

B) Two spatiotemporal configurations: first shape in the top position and second shape in the bottom position (FTSB), and first shape in the bottom position and second shape in the top position (FBST). Left and right visual field trials were pooled for analysis (Johnson et al., 2017) (Fig. S2).

C) RT did not differ between FTSB (red) and FBST (blue) configurations.

D) Accuracy did not differ between FTSB (red) and FBST (blue) configurations. Circles represent individual data points.

E) Accuracy was diminished in PFC patients relative to controls. *, significant.

Previous analysis of this dataset indicated that presentation of any test cue (spatial, temporal, or identity) recruits PFC, as demonstrated by power and PFC → parieto-occipital connectivity in the delta-theta band (δθ; 2-7 Hz) during the post-cue processing interval (Johnson et al., 2017). This oscillatory mechanism was diminished with PFC lesions, resulting in an overall decrease of 8% in WM performance. We have also reported intracranial EEG data from the same task, extending scalp EEG effects. Compared to the ongoing maintenance of shape identity, selection of spatiotemporal features further strengthened frontoparietal δθ connectivity (Johnson, King-Stephens, et al., 2018) and medial temporal θ modulation of activity in PFC (Johnson, Adams, et al., 2018). These findings reveal a domain-general PFC δθ mechanism for top-down control and network-level oscillatory mechanisms for the processing of space and time. Other research groups have also linked control to PFC δθ oscillations (de Vries, Slagter, & Olivers, 2020; Summerfield & Mangels, 2005) and spatiotemporal processing to posterior regions (Bachevalier & Nemanic, 2008; Constantinidis & Steinmetz, 2005; Nyberg et al 1996; Ranganath & Hsieh, 2016; Sommer, Rose, Gläscher, Wolbers, & Büchel, 2005).

It is unknown whether comparable oscillatory mechanisms might support the integration of spatial and temporal information prior to selecting a cued spatiotemporal feature from WM stores. To investigate spatiotemporal integration, we examined the pre-cue maintenance interval, during which both spatial and temporal information defined the shape pair. Pairs of shapes were defined by their spatiotemporal configuration: the first shape presented on top (first-top-second-bottom; FTSB) and the reverse (FBST; Fig. 1B). Importantly, FTSB and FBST configurations required the conjunction of spatial and temporal information equally and differed only in how the information was integrated (Seymour, Clifford, Logothetis, & Bartels, 2009). With this method, instead of asking how the brain processes space and time, we asked how the brain codes explicitly for space-time pairings. We adopted the method used to address the feature binding problem and extended it to the second-order problem of information integration in WM. Here, variation in EEG patterns from baseline may indicate correlates of WM, whereas systematic variation in EEG patterns between FTSB and FBST configurations indicates spatiotemporal integration. We first derived EEG signatures of spatiotemporal integration by comparing the two configurations on several metrics within the control group. We then tested the role of PFC in an interaction approach by comparing derived EEG signatures between the control and PFC lesion groups (Vaidya et al., 2019). We hypothesized that PFC δθ oscillations would synchronize neural networks during spatiotemporal integration and be diminished with PFC lesions, linking FIT and BBS.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects

Subjects were 20 healthy adults (11 males; mean ± SD [range]: 44 ± 19 [19–70] years of age, 16 ± 3 years of education) and 14 patients with discrete PFC lesions (five males; 46 ± 16 [20–71] years of age, 15 ± 3 years of education). Lesions were unilateral (n = 7 left + 7 right hemisphere) with maximal lesion overlap in dorsolateral PFC (Fig. S1). All subjects had normal/corrected-to-normal vision; all patients were evaluated by a neurologist and had no other neurological or psychiatric diagnoses. Patient IQ was normal or higher. For additional details about individual lesion etiology, see (Johnson et al., 2017). All subjects gave written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.2. Behavioral task

Spatiotemporal integration was examined in a single-trial visuospatial WM paradigm that has been reported previously (Fig. 1A) (Johnson, Adams, et al., 2018; Johnson et al., 2017; Johnson, King-Stephens, et al., 2018). Following a 2-s fixation (−550 to −50 ms pretrial epoch used as the baseline), an 800-ms starting screen indicated that the upcoming stimuli would be tested on either spatiotemporal relations or stimulus identities. At encoding, two colored shapes were presented sequentially (200 ms each) in a top/bottom spatial orientation, separated by a 200-ms inter-stimulus interval (ISI). Shapes were presented to either the left or right visual hemifield. The test cue was presented mid-delay after a randomly jittered 900/1150-ms maintenance interval, followed by a post-cue processing interval of the same length. On spatiotemporal relation trials, the test cue was one of four words—TOP, BOTTOM, FIRST, or SECOND—and subjects responded by indicating which of two stimuli matched the cued position at encoding. On identity control trials, the test cue SAME prompted the subject to attend to the identities of both encoding stimuli, regardless of their spatiotemporal relationship. Subjects completed 120-240 trials (80-160 spatiotemporal relation trials) of the task.

Critically, both spatial and temporal information defined the shape pair during the pre-cue maintenance interval of spatiotemporal relation trials. We separated these trials by spatiotemporal configuration for analysis: the first stimulus in the top position and the second stimulus in the bottom position (FTSB), and the reverse (FBST). Because identity control trials did not require spatiotemporal integration, we restricted analyses to spatiotemporal relation trials. Because the visual field of presentation was not relevant to the WM task and did not affect behavior (Johnson et al., 2017) (Fig. S2), we pooled FTSB and FBST trials across left and right presentations (Fig. 1B).

To ensure that spatiotemporal configurations were equal in difficulty, we compared response times (RT; all correct trials with RT ≤ 2 s) and accuracy (percent correct) between FTSB and FBST trials using Wilcoxon rank sum tests. PFC lesion effects were confirmed by comparing overall accuracy (pooled FTSB and FBST trials) between the control and patient groups using a Wilcoxon rank sum test. Because several PFC lesion patients had slowed motor responses following stroke, we did not compare RT between groups.

2.3. Data acquisition and preprocessing

EEG data were collected using a 64+8 channel BioSemi ActiveTwo amplifier with Ag-AgCl pin-type active electrodes mounted on an elastic cap according to the International 10-20 System, sampled at 1024 Hz. Continuous eye gaze positions were recorded using an Eyelink 1000 (SR Research, Ontario, Canada) or iView X optical tracker (SMI, Teltow, Germany). A custom wooden chin rest was used to restrict subjects’ head movements to minimize contamination of the EEG signal in anterior channels.

Raw EEG data were referenced to the average of both earlobes, down-sampled to 256 Hz, and filtered between 1 and 70 Hz using finite impulse response filters. Electromyography artifacts were removed automatically, and line noise was removed using discrete Fourier transform. Subsequently, continuous data were segmented into trials, noisy channels were rejected based on visual inspection, and independent components analysis was used to remove artifacts (e.g., electrooculogram artifacts, heartbeat, auricular components, and residual cranial muscle activity) from remaining channels (Hipp & Siegel, 2013). Any rejected channels were then reconstructed by interpolation of the mean of the nearest neighboring channels, and trials with residual noise were rejected manually based on visual inspection. The final dataset included an average of 101 ± 23 trials per subject. We randomly removed trials to equate the number of FTSB and FBST trials in each subject, resulting in an average of 44 (range: 22-59) trials analyzed per configuration.

The surface Laplacian spatial filter was applied to artifact-free data to minimize volume conduction, isolate PFC scalp distributions, and maximize the accuracy of connectivity estimates (Cohen, 2015; Perrin, Pernier, Bertrand, & Echallier, 1989). Then, channels were swapped across the midline in the data of right-hemisphere lesion patients (n = 7/14) to normalize lesions to the left hemisphere. This procedure removes individual differences between left- and right-hemisphere lesioned patients (Fig. S1B) and increases statistical power in the lesion group. The same swapping procedure was also applied to 10/20 randomly chosen control datasets so any inter-hemispheric variation was removed from both groups (Johnson et al., 2017).

Finally, previous analysis of this dataset indicated that PFC lesions impacted PFC activity at baseline (Johnson et al., 2017). Further analysis of baseline effects using parameterized power spectrum estimation (Donoghue et al., 2020) confirmed that the aperiodic 1/f component of the signal was elevated over the lesioned area (Fig. S3). To equate signal amplitude between individuals, we z-score normalized every subject’s spatial-filtered data in the time domain before analysis (Fig. S4) (Cole & Voytek, 2017; Gerber, Sadeh, Ward, Knight, & Deouell, 2016; Vaidya, Pujara, Petrides, Murray, & Fellows, 2019). We then analyzed the z-score normalized EEG data over the 900-ms pre-cue maintenance interval of all correct spatiotemporal relation trials.

2.4. Event-related potentials

ERPs were computed at all 64 channels by averaging the EEG signal across FTSB and FBST trials per subject. Modulation of spatiotemporal integration was defined per subject as the absolute value of the difference between FTSB and FBST configurations.

2.5. Power spectra

Power was computed in five canonical frequency bands: delta (δ; 2-4 Hz), theta (θ; 4-7 Hz), alpha (α; 8-12 Hz), beta (β; 13-30 Hz), and gamma (γ; 30-50 Hz). After baseline correction (900-ms pre-cue maintenance interval – mean of the 500-ms pretrial baseline), we used a Hamming window based on a 900-ms periodogram to perform band-limited spectral decomposition. Power was computed per trial at all 64 channels and then averaged across trials per subject. Modulation of spatiotemporal integration was defined per subject as the absolute value of the difference between FTSB and FBST configurations.

2.6. Functional connectivity

Functional connectivity was computed using the phase lag index (PLI) measure of oscillatory synchrony (Stam, Nolte, & Daffertshofer, 2007). EEG traces were filtered into δ and θ bands using finite impulse response filters and transformed into the frequency domain using the fast Fourier transform (FFT). PLI was calculated from the instantaneous phase at each frequency and then outputs were averaged across frequencies. PLI was computed per trial at all 64-by-64 channel pairs and then averaged across trials per subject. Modulation of spatiotemporal integration was defined per subject as the absolute value of the difference between FTSB and FBST configurations.

2.7. Cross-frequency coupling

Cross-frequency phase-amplitude coupling (PAC) was computed using the oscillation-triggered coupling (OTC) method (Dvorak & Fenton, 2014). This method employs a data-driven, event-based, and parameter-free algorithm to quantify PAC in four steps:

- Spectral decomposition: Trials were padded by 4,500 ms and pooled into a single time-series, and the continuous wavelet transform was used to extract amplitude information at each frequency from 2-50 Hz. Time-frequency representations were obtained by convolving the Morlet wavelets (mw) with the EEG signal of a trial x(t) as follows:

where t and f depict the time and frequency points, σt is the standard deviation in the time-domain, and is a normalization factor to turn the wavelet energy to value 1.(1) Trigger detection: Time-frequency representations were z-score normalized across all time points and triggers were defined as z > 2 (i.e., p < 0.05) at each frequency. Triggers detected in the first or last 50 ms of each trial were considered noise from edges and excluded from analysis.

- OTC comodulogram: The EEG signal was fit within a window ± 150 ms around each trigger as follows:

where n denotes the trigger time points, N denotes the number of trigger events, and TW denotes the time window. The sum operator is used instead of the average to indicate the total number of trigger events. An OTC comodulogram is then generated with time on the x-axis and amplitude frequencies on the y-axis. The frequency which shows an oscillatory pattern is the amplitude frequency coupled to the oscillatory pattern in the EEG signal.(2) PAC: The FFT was applied to the OTC comodulogram to generate a PAC comodulogram with phase frequencies on the x-axis and amplitude frequencies on the y-axis.

PAC was computed from all trials at all 64 channels per subject to detect the frequency range of maximal coupling. PAC was then separately computed from FTSB and FBST trials. Modulation of spatiotemporal integration was defined per subject as the dB-corrected absolute value of the difference between FTSB and FBST configurations as follows:

| (3) |

where the comodulogram values represent the OTC comodulograms generated at step 3. For completeness, we also conducted the same PAC analyses on channel pairs across the 64×64 channel topography (Friese et al., 2013; Johnson, Adams, et al., 2018; Jones, Johnson, & Berryhill, 2020; Sauseng, Klimesch, Gruber, & Birbaumer, 2008). We did not observe significant modulation effects in inter-regional PAC and focus on intra-regional PAC within the 64 channels.

2.8. Statistical testing

All statistical analyses of EEG data were performed using Wilcoxon rank sum tests with a false discovery rate (FDR) multiple-comparison correction of q < 0.05 (Benjamini & Hochberg, 1995). Spatiotemporal integration was tested in controls and PFC lesion patients by comparing per-subject modulation values against zero. PFC effects were tested by comparing per-subject modulation values between the control and PFC lesion groups.

2.9. Study design and data availability

We report how we determined our sample size, all data exclusions, all inclusion/exclusion criteria, whether inclusion/exclusion criteria were established prior to data analysis, all manipulations, and all measures in the original publication of this dataset (Johnson et al., 2017). No part of this study was preregistered prior to the research being conducted.

The data and custom-built MATLAB codes that support the current findings are deposited to the University of California, Berkeley, Collaborative Research in Computational Neuroscience (CRCNS) database (https://doi.org/10.6080/K0ZC811B), which is accessible with a free CRCNS account (https://crcns.org). Account registration requires compliance with the CRCNS Terms of Use and is approved by a central administrator independent of the data authors. Per the Terms of Use, data are made available only for scientific purposes, and any publications derived from the data must state that CRCNS is the source of the data and cite the original paper.

3. Results

3.1. Behavior

We first compared per-subject mean behavioral RT and accuracy between FTSB and FBST configurations to ensure they were equal in difficulty. No significant differences were observed in RT (control p = 0.58; lesion p = 0.84; Fig. 1C) or accuracy (control p = 0.35; lesion p = 0.30; Fig. 1D). These null results ensure that EEG differences between spatiotemporal configurations cannot be explained by differences in task difficulty in the control or PFC lesion group.

We then confirmed the role of PFC in WM for spatiotemporal relations by comparing per-subject mean accuracy (i.e., pooled FTSB and FBST trials) between the control and PFC lesion groups. Accuracy was impaired in the lesion group (median correct: control 100% vs. lesion 90.76%, p < 10−9; Fig. 1E). Still, the lesion group performed well above chance (one-tailed t-test, p < 10−11), demonstrating that WM for spatiotemporal relations is only partially dependent on PFC. These results replicate the behavioral PFC lesion effects observed across all WM conditions, including identity trials (Johnson et al., 2017), suggesting that PFC supports spatiotemporal integration as part of a domain-general role.

3.2. Time-domain signatures of spatiotemporal integration in lateral posterior regions

We used ERPs to quantify the time-course of spatiotemporal integration across the whole brain (Agam & Sekuler, 2007; Schupp et al., 2004; Woodman, 2010). Previous analysis of this dataset indicated that PFC lesions did not significantly impact pre-cue maintenance ERPs across all WM conditions (Johnson et al., 2017), suggesting that PFC does not govern maintenance-related ERPs independent of spatiotemporal integration. Here, we examine whether ERPs might support spatiotemporal integration and, if so, whether such a signature depends on PFC.

We first compared FTSB and FBST configurations from per-channel ERPs averaged over three non-overlapping maintenance epochs. In controls, spatiotemporal integration was focused in lateral posterior channels during the initial 300 ms of the maintenance interval (FT7-T7-TP7-CP3, FDR-corrected p < 0.05; Fig. 2A). There were no significant effects in the 300-600 ms epoch, and only one channel (P10) exhibited significant effects in the 600-900 ms epoch. To visualize these early effects, we plotted the ERPs of a representative lateral posterior channel (TP7) from the onset of the first shape at encoding through maintenance (Fig. 2B). These results demonstrate that spatial and temporal information is integrated rapidly in lateral posterior regions.

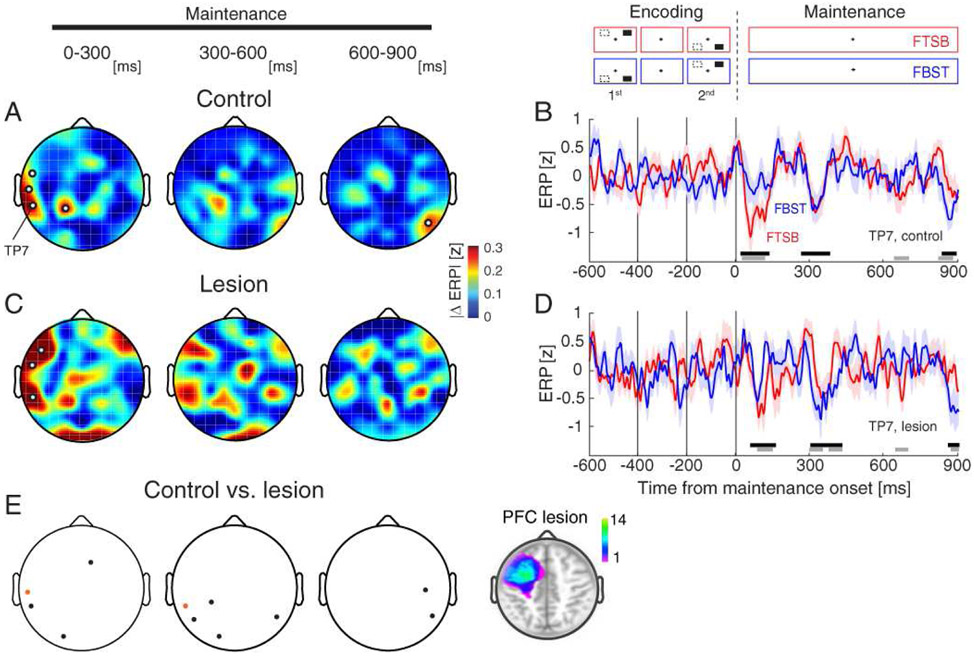

Figure 2. Lateral posterior signatures of spatiotemporal integration are PFC-independent.

A) Scalp distributions of absolute ERP differences between FTSB and FBST configurations in controls. Modulation was maximal in lateral posterior channels during the initial 300-ms maintenance epoch. White circles, channels with significant effects.

B) Mean ERPs over FTSB (red) and FBST (blue) trials for a representative lateral posterior channel (TP7) in controls. Gray bars indicate significant spatiotemporal integration (i.e., FTSB vs. FBST). For comparison, black bars indicate significant WM effects (pooled FTSB and FBST trials vs. zero). Shading, SEM.

C-D) Same as (A-B) in PFC lesion patients. Note the similarity to controls.

E) ERP modulation was similar between controls and PFC lesion patients in lateral posterior channels. Black circles, significant control > lesion; orange circles, significant lesion > control. Inset: PFC lesion location. Color bar, number of patients with lesions at the specified location.

We then assessed the role of PFC in the time-domain signatures of spatiotemporal integration by comparing per-subject ERP modulation (i.e., absolute difference between FTSB and FBST configurations) between the control and PFC lesion groups. Like controls, spatiotemporal integration in lesion patients was focused in lateral posterior channels during the initial 300 ms of the maintenance interval (F7-FT7-TP7, FDR-corrected p < 0.05; Figs. 2C-D). Lateral posterior signatures of spatiotemporal integration were largely unaffected by PFC lesions (Fig. 2E). Because both controls and PFC lesion patients exhibited early ERP modulation of spatiotemporal integration in lateral posterior channels, these results suggest that lateral posterior signatures of spatiotemporal integration are largely independent of PFC.

3.3. Frequency-domain signatures of spatiotemporal integration in frontal regions

We used power spectra to characterize frequency-domain signatures of spatiotemporal integration across the whole brain (Noda et al., 2017; Rihs, Michel, & Thut, 2009). Previous analysis of this dataset indicated that PFC lesions did not significantly impact pre-cue maintenance power across all WM conditions (Johnson et al., 2017), suggesting that PFC does not govern maintenance-related power independent of spatiotemporal integration. Here, we examine spectral signatures of spatiotemporal integration and the extent to which they might depend on PFC.

We first compared FTSB and FBST configurations from per-channel power over the maintenance interval in five canonical frequency bands: δ, θ, α, β, and γ. In controls, spatiotemporal integration was observed in frontal channels in the δ and θ bands (F7-F5-AF7-F6; FDR-corrected p < 0.05; Figs. 3A-B). There were no significant effects in the α, β, or γ band. These results reveal a frontal δθ mechanism for the rapid integration of spatial and temporal information.

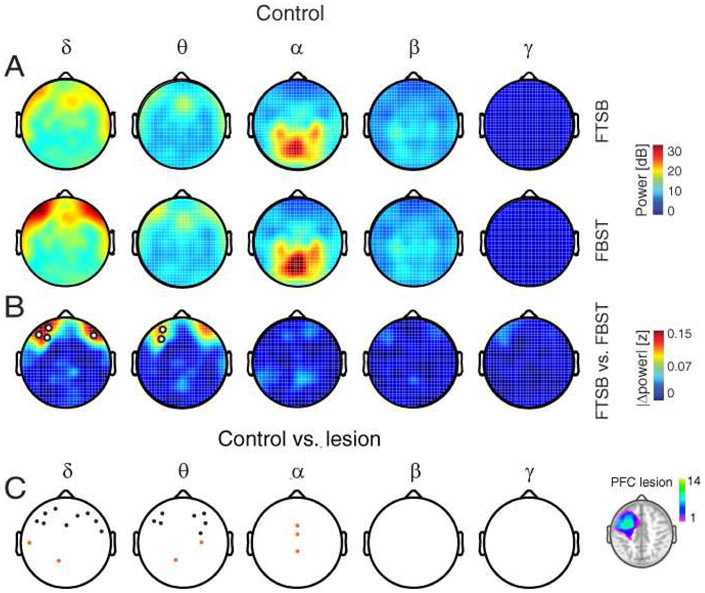

Figure 3. PFC lesions diminish frontal δθ signatures of spatiotemporal integration.

A) Scalp distributions of spectral power during the maintenance of FtSb (top) and FBST (bottom) configurations in controls.

B) Scalp distributions of absolute power differences between configurations in controls. Modulation was maximal in frontal δθ power. White circles, channels with significant effects.

C) Power modulation was diminished in frontal channels in PFC lesion patients relative to controls, but increased in central channels. Black circles, significant control > lesion; orange circles, significant lesion > control. Inset: PFC lesion location. Color bar, number of patients with lesions at the specified location.

We then assessed the role of PFC in frequency-domain signatures of spatiotemporal integration by comparing per-subject power modulation (i.e., absolute difference between FTSB and FBST configurations) in each frequency between the control and lesion groups. Spatiotemporal integration was diminished in the lesion group across frontal channels in the δ and θ bands, but increased across central channels in the δ, θ, and α bands (all FDR-corrected p < 0.05; Figs. 3C, S5). Critically, frontal channels exhibiting significant δθ modulation in controls exhibited diminished δθ modulation with PFC lesions. In PFC lesion patients, some modulation was instead observed more posteriorly and in the α band. These findings indicate that spatiotemporal integration partially depends on δθ activity in PFC.

3.4. Functional connectivity signatures of spatiotemporal integration

Based on the outcomes of frequency-domain analyses, we investigated spatiotemporal integration and the role of PFC in patterns of δθ oscillatory synchrony across the whole brain. We used a non-directed measure, PLI (Stam et al., 2007), to test for oscillatory network signatures of spatiotemporal integration without any assumption of connections to or from PFC (Fig. 4A). We first assessed whether PFC lesions affected oscillatory synchrony independent of spatiotemporal integration (i.e., pooled FTSB and FBST trials). PLI was attenuated in both frontal-posterior and posterior lateral-mesial channel pairs in the lesion group relative to the control group (FDR-corrected p < 0.05; Fig. 4B). This result reveals that δθ oscillatory networks depend on δθ signals from PFC during WM maintenance. We next investigated whether δθ oscillatory networks supported spatiotemporal integration and whether PFC might be comparably involved. Further observation of diminished spatiotemporal integration with PFC lesions would suggest a PFC-dependent δθ oscillatory network signature of spatiotemporal integration related to domain-general control.

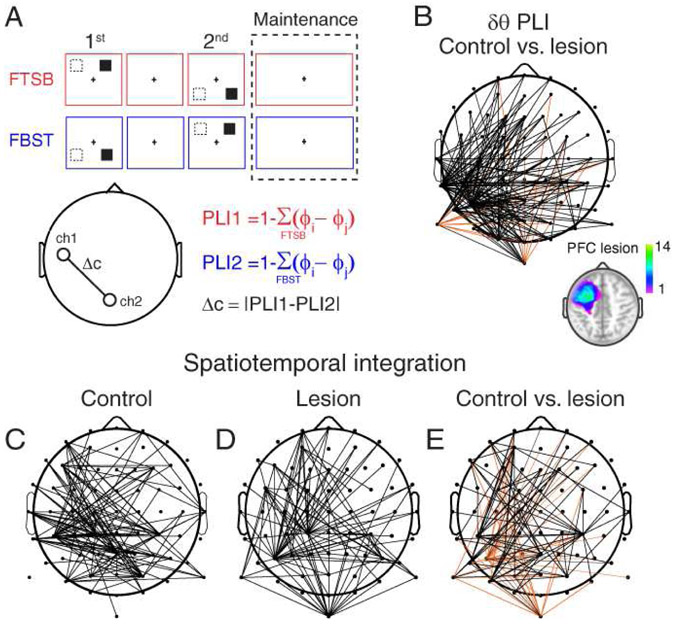

Figure 4. PFC lesions differentially affect frontal-posterior and lateral-mesial posterior δθ synchrony signatures of spatiotemporal integration.

A) Computation of PLI. δ and θ phase information was extracted per channel over the maintenance interval, and PLI was computed per trial by subtracting all 64-by-64 channel-pair phase differences from 1. Outputs were averaged over frequencies. FtSb (red) and FBST (blue) trials were averaged together for analysis of group differences in (B), and separately for analyses of spatiotemporal integration in (C-E). Modulation was quantified as the absolute difference between FtSb and FBST configurations.

B) Scalp distribution of group differences in PLI independent of spatiotemporal integration. PLI was largely diminished in PFC lesion patients relative to controls. Black lines, significant control > lesion; orange lines, significant lesion > control. Inset: PFC lesion location. Color bar, number of patients with lesions at the specified location.

C) Scalp distribution of absolute PLI differences between FTSB and FBST configurations in controls. Modulation was evident in frontal-posterior and lateral-mesial posterior channel pairs. Black lines, channel pairs with significant effects.

D) Same as (C) in PFC lesion patients.

E) PLI modulation was diminished in frontal-posterior channel pairs in PFC lesion patients relative to controls, but selectively increased in lateral-mesial posterior channel pairs. Same conventions as (B).

In controls, spatiotemporal integration was observed in both frontal-posterior and posterior lateral-mesial channel pairs (FDR-corrected p < 0.05; Fig. 4C). This finding links δθ synchrony to the rapid integration of spatial and temporal information. We then assessed the role of PFC in δθ synchrony signatures of spatiotemporal integration by comparing the per-subject modulation of feature integration (see Fig. 4A) between the control and lesion groups. Spatiotemporal integration was diminished in the lesion group in frontal-posterior channel pairs, but selectively increased in posterior lateral-mesial channel pairs (FDR-corrected p < 0.05; Figs. 4D-E). Critically, channel pairs exhibiting significant modulation in controls exhibited diminished modulation with PFC lesions. However, in PFC lesion patients, some modulation was additionally observed in posterior lateral-mesial channel pairs. These findings demonstrate that whole-brain δθ synchrony underlies spatiotemporal integration, and these δθ networks are partially, but not wholly, dependent on input from PFC.

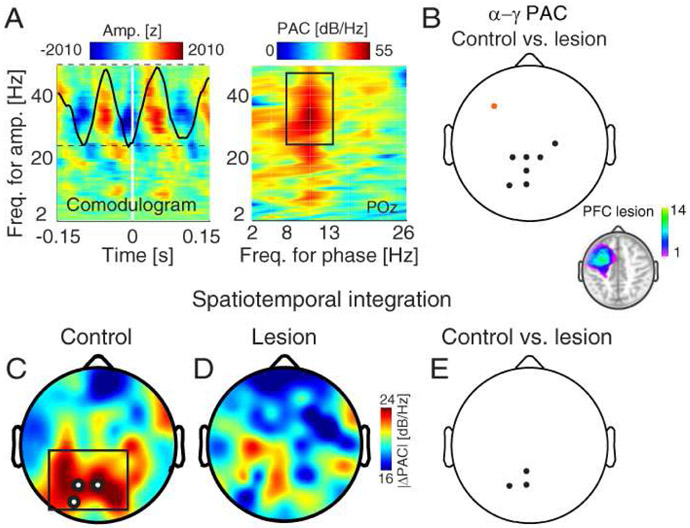

3.5. Cross-frequency coupling signatures of spatiotemporal integration in mesial posterior Regions

We used PAC to further investigate the role of PFC in synchronous activity supporting feature integration. PAC permits interactions across temporal scales (Bonnefond, Kastner, & Jensen, 2017; Canolty & Knight, 2010; Fell & Axmacher, 2011; Helfrich & Knight, 2016; Hyafil, Giraud, Fontolan, & Gutkin, 2015; Usman & Jensen, 2013), providing another possible oscillatory mechanism for the rapid integration of spatial and temporal information. We used a data-driven measure, OTC (Dvorak & Fenton, 2014), to compute PAC. By treating increases in band-limited activity as discrete events, OTC provides an assumption-free measure of PAC that is appropriate for short time windows. PAC was maximal over posterior regions between α (8-12 Hz) oscillations and γ (30-50 Hz) activity (Fig. 5A). For this reason, we input per-channel mean α-γ PAC into all statistical comparisons.

Figure 5. PFC lesions diminish mesial posterior PAC signatures of spatiotemporal integration.

A) PAC in a representative posterior channel (POz) in controls. Amplitude information was extracted per channel from 2-50 Hz over the maintenance interval, and OTC was quantified by averaging the EEG signal around increases in band-limited activity (i.e., triggers; left). PAC was computed per channel by applying the FFT to the OTC comodulogram (right). FTSB and FbSt trials were pooled together for detection of PAC. Black square, frequency range of maximal PAC.

B) Scalp distribution of group differences in PAC independent of spatiotemporal integration. Posterior PAC was diminished in PFC lesion patients relative to controls. Black circles, significant control > lesion; orange circles, significant lesion > control. Inset: PFC lesion location. Color bar, number of patients with lesions at the specified location.

C) Scalp distribution of absolute PAC differences between FTSB and FBST configurations in controls. Modulation was maximal in mesial posterior channels. White circles, channels with significant effects.

D) Same as (C) in PFC lesion patients.

E) PAC modulation was diminished in PFC lesion patients relative to controls. Group differences were evident in mesial posterior channels. Same conventions as (B).

As in the analysis of δθ synchrony, we first assessed whether PFC lesions affected α-γ PAC independent of spatiotemporal integration (i.e., pooled FTSB and FBST trials). PAC was increased over the lesion (channel F5) and attenuated in mesial posterior channels (PO3-POz-Pz-CP1-CPz-CP2-C4) in the lesion group relative to the control group (all FDR-corrected p < 0.05; Fig. 5B). This result indicates that posterior oscillatory modulation of γ activity depends on PFC input during WM maintenance. We next investigated whether posterior α-γ PAC supported spatiotemporal integration and whether PFC might be comparably involved. Further observation of diminished spatiotemporal integration with PFC lesions would suggest a PFC-dependent PAC signature of spatiotemporal integration related to domain-general control.

In controls, spatiotemporal integration was observed in mesial posterior channels (PO3-POz-O1; FDR-corrected p < 0.05; Fig. 5C). This finding links posterior α-γ PAC to the rapid integration of spatial and temporal information. We then assessed the role of PFC in α-γ PAC signatures of spatiotemporal integration by comparing per-subject modulation (i.e., dB-corrected absolute difference between FTSB and FBST configurations) between the control and lesion groups. Spatiotemporal integration was diminished in the lesion group in mesial posterior channels (PO3-POz-Pz; FDR-corrected p < 0.05; Figs. 5D, S6). Critically, channels exhibiting significant modulation in controls exhibited diminished modulation with PFC lesions. These findings reveal that spatiotemporal integration is partially governed by posterior PAC with PFC input.

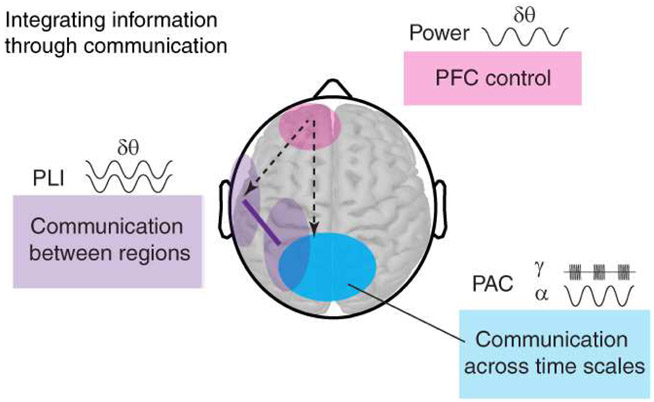

3.6. Summary

The rapid integration of spatial and temporal information partially depends on PFC. Analyses of spectral power (Figs. 3, S5) and functional connectivity (Fig. 4) revealed δθ signatures of spatiotemporal integration in frontal regions and frontal-posterior and lateral-mesial posterior interactions. Analysis of cross-frequency coupling (Figs. 5, S6) revealed a mesial posterior signature of spatiotemporal integration that also depends on PFC input. These findings link synchronous activity between PFC, lateral posterior, and mesial posterior regions to the rapid integration of spatial and temporal information (Fig. 6). PFC lesions diminished both frontal and posterior oscillatory signatures, revealing a role for PFC in neural networks supporting spatiotemporal integration. However, lateral posterior ERPs (Fig. 2) and δθ connectivity between lateral and mesial posterior regions were intact or increased with PFC lesions. Unlike frontal and mesial posterior mechanisms, the lateral posterior contribution to spatiotemporal integration is dissociable from PFC.

Figure 6. Oscillatory synchrony supports spatiotemporal integration with PFC input.

Functional model and summary of EEG results. δθ oscillations support PFC control (pink) and communication between PFC, lateral posterior, and mesial posterior regions (purple) during spatiotemporal integration. Mesial posterior cross-frequency coupling between α oscillations and γ activity (blue) further supports spatiotemporal integration with PFC input, whereas the lateral posterior contribution is dissociable from PFC (solid purple line).

Finally, correlation analyses of individual signatures of spatiotemporal integration revealed that both frontal δθ power and mesial posterior α-γ PAC relate to individual behavioral performance. Specifically, we analyzed the per-subject mean values over the channels that showed significantly greater FTSB vs. FBST modulation in controls relative to PFC lesion patients (i.e., the interactive effect). We observed a positive correlation between behavioral accuracy and each signature such that greater modulation was related to greater accuracy across all subjects (Fig. S7; power: r = 0.4, p = 0.04; PAC: r = 0.45, p = 0.016). These results provide further support for a functional model in which spatiotemporal information is integrated through communication in large-scale neural networks.

4. Discussion

We demonstrate that neural oscillations support the rapid integration of spatial and temporal information into unified mnemonic representations with input from PFC. Specifically, spatiotemporal integration was associated with δθ activity in PFC, δθ synchrony between PFC, lateral posterior, and mesial posterior regions, and α-γ coupling in mesial posterior regions. These results implicate regions of the brain involved in both control and vision, consistent with both FIT (Ashbridge et al., 1999; Colby & Goldberg, 1999; Corbetta et al., 1995; Friedman-Hill et al., 1995; Libby et al., 2014; Olson et al., 2006; L. C. Robertson, 2003; Shafritz et al., 2002; Zokaei et al., 2019) and BBS (Eckhorn et al., 1988; Gray et al., 1989; König et al., 1995; Shadlen & Movshon, 1999; Wu et al., 2007; Zhou et al., 2019). By defining how interactions occur within and between regions, we show that oscillatory synchrony provides a signature of integration across the whole brain. Because oscillatory signatures were attenuated with PFC lesions, we show that PFC, traditionally associated with FIT (Ashbridge et al., 1999; Colby & Goldberg, 1999; Corbetta et al., 1995; Friedman-Hill et al., 1995; Hannula & Ranganath, 2008; Haxby et al., 1991; Libby et al., 2014; Marois, Chun, & Gore, 2000; Miller & Cohen, 2001; Mishkin, Ungerleider, & Macko, 1983; Ninokura, Mushiake, & Tanji, 2004b; Olson et al., 2006; Prabhakaran, Narayanan, Zhao, & Gabrieli, 2000; L. C. Robertson, 2003; L. Robertson, Treisman, Friedman-Hill, & Grabowecky, 1997; Sakai & Miyashita, 1993; Shafritz et al., 2002; A. Treisman, 1998; Zokaei et al., 2019), supports spatiotemporal integration. By showing that posterior α-γ coupling, a mechanism in line with BBS (Eckhorn et al., 1988; Engel, Fries, & Singer, 2001; Engel & Singer, 2001; Gray et al., 1989; König et al., 1995; Shadlen & Movshon, 1999; Summerfield & Mangels, 2005; Wu et al., 2007; Zhou et al., 2019), is also attenuated with PFC lesions, our results link FIT and BBS.

We thus extend classic theories of visuospatial feature binding from perception to the ‘integration problem’ of continuously updating our memories as we move through the world. We further provide the first neurological demonstration that both frontal and posterior oscillatory substrates of spatiotemporal integration depend on PFC. However, despite a median 9% drop in behavioral performance with PFC lesions relative to controls, patients remained proficient on the spatiotemporal integration task. This result indicates that spatiotemporal integration depends partially, but not wholly, on PFC (Johnson et al., 2017). Building on reports of temporal and parietal correlates of spatiotemporal processing by our group (Johnson, Adams, et al., 2018; Johnson, King-Stephens, et al., 2018) and others (Bachevalier & Nemanic, 2008; Constantinidis & Steinmetz, 2005; Nyberg et al., 1996; Ranganath & Hsieh, 2016; Sommer et al., 2005), we propose that PFC directs posterior oscillatory signatures of spatiotemporal integration. When PFC is damaged, these posterior signatures provide adequate resources for proficient, albeit suboptimal, performance. This proposal is based on five main findings.

First, ERP modulation of spatiotemporal integration was specific to lateral posterior channels, and was unaffected by PFC lesions. Second, power modulation of spatiotemporal integration was specific to δθ activity in frontal channels, and was diminished with PFC lesions. This finding extends other lesion (Voytek et al., 2012), fMRI (Prabhakaran et al., 2000), and electrophysiological (Ninokura, Mushiake, & Tanji, 2004a) work associating PFC with item-context integration. Both ERP and power results also link PFC specifically to task-relevant δθ activity (de Vries et al., 2020; Johnson et al., 2017; Summerfield & Mangels, 2005), supporting the role of PFC in the frontal oscillatory substrate of spatiotemporal integration and suggesting a dissociable lateral posterior contribution. We further note that difficulty was equal between spatiotemporal configurations in both the control and PFC lesion groups, and thus the selective effects of PFC lesions on oscillatory signatures of spatiotemporal integration are not explained by task difficulty.

Third, δθ functional-connectivity modulation of spatiotemporal integration was evident in frontal-posterior and posterior lateral-mesial channel pairs. Frontal-posterior signatures were diminished with PFC lesions, whereas posterior lateral-mesial signatures were intact or increased in the lesion group. These findings are in accord with other lesion, fMRI, and EEG research showing that item-context integration engages temporal (Hannula & Ranganath, 2008; Johnson, Adams, et al., 2018; Libby et al., 2014; Olson et al., 2006; Sommer et al., 2005; Zokaei et al., 2019) and parietal regions (Johnson, King-Stephens, et al., 2018), as well as temporo-parietal (Pollmann, Zinke, Baumgartner, Geringswald, & Hanke, 2014) and frontal-posterior connectivity (Summerfield & Mangels, 2005). Our findings suggest that the posterior lateral-mesial contribution, consistent with temporo-parietal connectivity, is independent of PFC. Fourth, cross-frequency α-γ modulation of spatiotemporal integration was specific to mesial posterior channels, and was diminished with PFC lesions. Indeed, performance deficits in PFC patients were commensurate with diminished α-γ modulation of spatiotemporal integration. These findings reveal that mesial posterior cross-frequency coupling, consistent with communication across temporal scales in visual regions, depends on PFC. Last, PFC lesions also diminished frontal-posterior δθ synchrony and mesial posterior α-γ PAC independent of spatiotemporal integration, corroborating a domain-general role for PFC in WM (D’Esposito & Postle, 2015; Helfrich & Knight, 2016; Johnson et al., 2017; Lara & Wallis, 2015). Spatiotemporal integration may be governed by domain-specific posterior mechanisms with input from PFC.

In conclusion, our data show that neural oscillations support spatiotemporal integration by way of communication through coherence (Fries, 2005, 2015) and cross-frequency coupling (Bonnefond et al., 2017; Canolty & Knight, 2010; Fell & Axmacher, 2011; Helfrich & Knight, 2016; Hyafil et al., 2015; Lisman & Jensen, 2013). Low-frequency neural oscillations synchronize PFC and posterior networks during spatiotemporal integration. Whereas the contribution of lateral posterior regions to successful resolution of this ‘integration problem’ may be independent of PFC, optimal performance depends on oscillatory synchrony between PFC, lateral posterior, and mesial posterior regions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank D. Scabini and A.-K. Solbakk for coordinating all patient testing efforts; C. D. Dewar, A.-K. Solbakk, T. Endestad, T. R. Meling, and J. Lubell for assistance with data acquisition; and C. D. Dewar for assistance with lesion and EEG data analysis.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (2R37NS21135, K99NS115918), James S. McDonnell Foundation (220020448), Research Council of Norway (240389/F20), and University of Oslo Internal Fund.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

None.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Agam Y, & Sekuler R (2007). Interactions between working memory and visual perception: An ERP/EEG study. NeuroImage, 36(3), 933–942. 10.1016/J.NEUROIMAGE.2007.04.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashbridge E, Cowey A, & Wade D (1999). Does parietal cortex contribute to feature binding? Neuropsychologia, 37(9), 999–1004. 10.1016/S0028-3932(98)00160-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachevalier J, & Nemanic S (2008). Memory for spatial location and object-place associations are differently processed by the hippocampal formation, parahippocampal areas TH/TF and perirhinal cortex. Hippocampus, 18(1), 64–80. 10.1002/hipo.20369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baddeley A (2012). Working Memory: Theories, Models, and Controversies. Annual Review of Psychology, 63(1), 1–29. 10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baddeley AD, Allen RJ, & Hitch GJ (2011). Binding in visual working memory: The role of the episodic buffer. Neuropsychologia, 49(6), 1393–1400. 10.1016/J.NEUROPSYCHOLOGIA.2010.12.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baddeley A, & Della Sala S (1996). Working memory and executive control. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 351(1346), 1397–1404. 10.1098/rstb.1996.0123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bays PM, Wu EY, & Husain M (2011). Storage and binding of object features in visual working memory. Neuropsychologia, 49(6), 1622–1631. 10.1016/J.NEUROPSYCHOLOGIA.2010.12.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, & Hochberg Y (1995). Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Methodological), 57(1), 289–300. 10.1111/j.2517-6161.1995.tb02031.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnefond M, Kastner S, & Jensen O (2017). Communication between Brain Areas Based on Nested Oscillations. ENeuro, 4(2). 10.1523/ENEURO.0153-16.2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown LA, & Brockmole JR (2010). The Role of Attention in Binding Visual Features in Working Memory: Evidence from Cognitive Ageing. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 63(10), 2067–2079. 10.1080/17470211003721675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canolty RT, & Knight RT (2010). The functional role of cross-frequency coupling. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 14(11), 506–515. 10.1016/J.TICS.2010.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MX (2015). Comparison of different spatial transformations applied to EEG data: A case study of error processing. International Journal of Psychophysiology : Official Journal of the International Organization of Psychophysiology, 97(3), 245–257. 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2014.09.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colby CL, & Goldberg ME (1999). SPACE AND ATTENTION IN PARIETAL CORTEX. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 22(1), 319–349. 10.1146/annurev.neuro.22.1.319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole SR, & Voytek B (2017). Brain Oscillations and the Importance of Waveform Shape. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 21(2), 137–149. 10.1016/j.tics.2016.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constantinidis C, & Steinmetz MA (2005). Posterior parietal cortex automatically encodes the location of salient stimuli. The Journal of Neuroscience : The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 25(1), 233–238. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3379-04.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbetta M, Shulman GL, Miezin FM, & Petersen SE (1995). Superior parietal cortex activation during spatial attention shifts and visual feature conjunction. Science (New York, N.Y.), 270(5237), 802–805. 10.1126/SCIENCE.270.5237.802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Esposito M, & Postle BR (2015). The Cognitive Neuroscience of Working Memory. Annual Review of Psychology, 66(1), 115–142. 10.1146/annurev-psych-010814-015031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vries IEJ, Slagter HA, & Olivers CNL (2020, February 1). Oscillatory Control over Representational States in Working Memory. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. Elsevier Ltd. 10.1016/j.tics.2019.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dvorak D, & Fenton AA (2014). Toward a proper estimation of phase–amplitude coupling in neural oscillations. Journal of Neuroscience Methods, 225, 42–56. 10.1016/J.JNEUMETH.2014.01.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckhorn R, Bauer R, Jordan W, Brosch M, Kruse W, Munk M, & Reitboeck HJ (1988). Coherent oscillations: A mechanism of feature linking in the visual cortex? Biological Cybernetics, 60(2), 121–130. 10.1007/BF00202899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel AK, Fries P, & Singer W (2001). Dynamic predictions: Oscillations and synchrony in top–down processing. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 2(10), 704–716. 10.1038/35094565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel AK, & Singer W (2001). Temporal binding and the neural correlates of sensory awareness. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 5(1), 16–25. 10.1016/S1364-6613(00)01568-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fell J, & Axmacher N (2011). The role of phase synchronization in memory processes. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 12(2), 105–118. 10.1038/nrn2979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman-Hill SR, Robertson LC, & Treisman A (1995). Parietal contributions to visual feature binding: evidence from a patient with bilateral lesions. Science (New York, N.Y.), 269(5225), 853–855. 10.1126/SCIENCE.7638604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fries P (2005). A mechanism for cognitive dynamics: neuronal communication through neuronal coherence. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 9(10), 474–480. 10.1016/J.TICS.2005.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fries P (2015). Rhythms for Cognition: Communication through Coherence. Neuron, 88(1), 220–235. 10.1016/J.NEURON.2015.09.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friese U, Köster M, Hassler U, Martens U, Trujillo-Barreto N, & Gruber T (2013). Successful memory encoding is associated with increased cross-frequency coupling between frontal theta and posterior gamma oscillations in human scalp-recorded EEG. NeuroImage, 66, 642–647. 10.1016/J.NEUROIMAGE.2012.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerber EM, Sadeh B, Ward A, Knight RT, & Deouell LY (2016). Non-Sinusoidal Activity Can Produce Cross-Frequency Coupling in Cortical Signals in the Absence of Functional Interaction between Neural Sources. PLOS ONE, 11(12), e0167351. 10.1371/journal.pone.0167351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golomb JD, L’Heureux ZE, & Kanwisher N (2014). Feature-binding errors after eye movements and shifts of attention. Psychological Science, 25(5), 1067–1078. 10.1177/0956797614522068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray CM, König P, Engel AK, & Singer W (1989). Oscillatory responses in cat visual cortex exhibit inter-columnar synchronization which reflects global stimulus properties. Nature, 338(6213), 334–337. 10.1038/338334a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donoghue T, Haller M, Peterson E, Varma P, Sebastian P, Gao R, … Voytek B (2020). Parameterizing neural power spectra into periodic and aperiodic components. Nature Neuroscience, 23, 1655–1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannula DE, & Ranganath C (2008). Medial temporal lobe activity predicts successful relational memory binding. The Journal of Neuroscience : The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 28(1), 116–124. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3086-07.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haxby JV, Grady CL, Horwitz B, Ungerleider LG, Mishkin M, Carson RE, … Rapoport SI (1991). Dissociation of object and spatial visual processing pathways in human extrastriate cortex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 88(5), 1621–1625. 10.1073/pnas.88.5.1621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helfrich RF, & Knight RT (2016). Oscillatory Dynamics of Prefrontal Cognitive Control. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 20(12), 916–930. 10.1016/J.TICS.2016.09.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hipp JF, & Siegel M (2013). Dissociating neuronal gamma-band activity from cranial and ocular muscle activity in EEG. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 7, 338. 10.3389/fnhum.2013.00338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyafil A, Giraud A-L, Fontolan L, & Gutkin B (2015). Neural Cross-Frequency Coupling: Connecting Architectures, Mechanisms, and Functions. Trends in Neurosciences, 38(11), 725–740. 10.1016/J.TINS.2015.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyun J. seok, Woodman GF, & Luck SJ (2009). The role of attention in the binding of surface features to locations. Visual Cognition, 17(1–2), 10–24. 10.1080/13506280802113894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson EL, Adams JN, Solbakk A-K, Endestad T, Larsson PG, Ivanovic J, … Knight RT (2018). Dynamic frontotemporal systems process space and time in working memory. PLOS Biology, 16(3), e2004274. 10.1371/journal.pbio.2004274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson EL, Dewar CD, Solbakk A-KK, Endestad T, Meling TR, & Knight RT (2017). Bidirectional Frontoparietal Oscillatory Systems Support Working Memory. Current Biology, 27(12), 1829–1835.e4. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0960982217305821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson EL, King-Stephens D, Weber PB, Laxer KD, Lin JJ, & Knight RT (2018). Spectral Imprints of Working Memory for Everyday Associations in the Frontoparietal Network. Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience, 12, 65. 10.3389/fnsys.2018.00065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones KT, Johnson EL, & Berryhill ME (2020). Frontoparietal theta-gamma interactions track working memory enhancement with training and tDCS. NeuroImage, 211, 116615. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2020.116615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katzner S, Busse L, & Treue S (2006). Feature-based attentional integration of color and visual motion. Journal of Vision, 6(3), 7. 10.1167/6.3.7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- König P, Engel AK, & Singer W (1995). Relation between oscillatory activity and long-range synchronization in cat visual cortex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 92(1), 290–294. 10.1073/pnas.92.1.290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lara AH, & Wallis JD (2015). The Role of Prefrontal Cortex in Working Memory: A Mini Review. Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience, 9, 173. 10.3389/FNSYS.2015.00173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libby LA, Hannula DE, & Ranganath C (2014). Medial temporal lobe coding of item and spatial information during relational binding in working memory. The Journal of Neuroscience : The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 34(43), 14233–14242. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0655-14.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisman JE, & Jensen O (2013). The Theta-Gamma Neural Code. Neuron, 77(6), 1002–1016. 10.1016/J.NEURON.2013.03.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luck SJ, & Hillyard SA (1994). Spatial Filtering During Visual Search: Evidence From Human Electrophysiology. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 20(5), 1000–1014. 10.1037/0096-1523.20.5.1000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marois R, Chun MM, & Gore JC (2000). Neural Correlates of the Attentional Blink. Neuron, 28(1), 299–308. 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)00104-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller EK, & Cohen JD (2001). An integrative theory of prefrontal cortex function. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 24(1), 167–202. 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishkin M, Ungerleider LG, & Macko KA (1983). Object vision and spatial vision: two cortical pathways. Trends in Neurosciences, 6, 414–417. 10.1016/0166-2236(83)90190-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Näätänen R, Paavilainen P, Rinne T, & Alho K (2007, December). The mismatch negativity (MMN) in basic research of central auditory processing: A review. Clinical Neurophysiology. 10.1016/j.clinph.2007.04.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Näätänen Risto. (1982). Processing negativity: An evoked-potential reflection. Psychological Bulletin, 92(3), 605–640. 10.1037/0033-2909.92.3.605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ninokura Y, Mushiake H, & Tanji J (2004a). Integration of temporal order and object information in the monkey lateral prefrontal cortex. Journal of Neurophysiology, 91(1), 555–560. 10.1152/jn.00694.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ninokura Y, Mushiake H, & Tanji J (2004b). Integration of Temporal Order and Object Information in the Monkey Lateral Prefrontal Cortex. Journal of Neurophysiology, 91(1), 555–560. 10.1152/jn.00694.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noda Y, Barr MS, Zomorrodi R, Cash RFH, Farzan F, Rajji TK, … Blumberger DM (2017). Evaluation of short interval cortical inhibition and intracortical facilitation from the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in patients with schizophrenia. Scientific Reports, 7(1), 17106. 10.1038/s41598-017-17052-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyberg L, McIntosh AR, Cabeza R, Habib R, Houle S, & Tulving E (1996). General and specific brain regions involved in encoding and retrieval of events: what, where, and when. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 93(20), 11280–11285. 10.1073/pnas.93.20.11280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson IR, Page K, Moore KS, Chatterjee A, & Verfaellie M (2006). Working memory for conjunctions relies on the medial temporal lobe. The Journal of Neuroscience : The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 26(17), 4596–4601. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1923-05.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parra MA, Della Sala S, Logie RH, & Morcom AM (2014). Neural correlates of shape-color binding in visual working memory. Neuropsychologia, 52(1), 27–36. 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2013.09.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrin F, Pernier J, Bertrand O, & Echallier JF (1989). Spherical splines for scalp potential and current density mapping. Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology, 72(2), 184–187. 10.1016/0013-4694(89)90180-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollmann S, Zinke W, Baumgartner F, Geringswald F, & Hanke M (2014). The right temporo-parietal junction contributes to visual feature binding. NeuroImage, 101, 289–297. 10.1016/J.NEUROIMAGE.2014.07.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prabhakaran V, Narayanan K, Zhao Z, & Gabrieli JDE (2000). Integration of diverse information in working memory within the frontal lobe. Nature Neuroscience, 3(1), 85–90. 10.1038/71156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranganath C, & Hsieh L-T (2016). The hippocampus: a special place for time. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1369(1), 93–110. 10.1111/nyas.13043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rihs TA, Michel CM, & Thut G (2009). A bias for posterior α-band power suppression versus enhancement during shifting versus maintenance of spatial attention. NeuroImage, 44(1), 190–199. 10.1016/J.NEUROIMAGE.2008.08.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson LC (2003). Binding, spatial attention and perceptual awareness. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 4(2), 93–102. 10.1038/nrn1030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson L, Treisman A, Friedman-Hill S, & Grabowecky M (1997). The Interaction of Spatial and Object Pathways: Evidence from Balint’s Syndrome. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 9(3), 295–317. 10.1162/jocn.1997.9.3.295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai K, & Miyashita Y (1993). Memory and imagery in the temporal lobe. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 3(2), 166–170. 10.1016/0959-4388(93)90205-D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sala JB, & Courtney SM (2007). Binding of what and where during working memory maintenance. In Cortex (Vol. 43, pp. 5–21). Masson SpA. 10.1016/S0010-9452(08)70442-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauseng P, Klimesch W, Gruber WR, & Birbaumer N (2008). Cross-frequency phase synchronization: A brain mechanism of memory matching and attention. NeuroImage, 40(1), 308–317. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.11.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenfeld MA, Tempelmann C, Martinez A, Hopf J-MM, Sattler C, Heinze H-JJ, & Hillyard SA (2003). Dynamics of feature binding during object-selective attention. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 100(20), 11806–11811. 10.1073/PNAS.1932820100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schupp HT, Öhman A, Junghöfer M, Weike AI, Stockburger J, & Hamm AO (2004). The Facilitated Processing of Threatening Faces: An ERP Analysis. Emotion, 4(2), 189–200. 10.1037/1528-3542.4.2.189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seymour K, Clifford CWG, Logothetis NK, & Bartels A (2009). The coding of color, motion, and their conjunction in the human visual cortex. Current Biology, 19(3), 177–183. 10.1016/J.CUB.2008.12.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shadlen MN, & Movshon JA (1999). Synchrony unbound: a critical evaluation of the temporal binding hypothesis. Neuron, 24(1), 67–77, 111–125. 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80822-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafritz KM, Gore JC, & Marois R (2002). The role of the parietal cortex in visual feature binding. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 99(16), 10917–10922. 10.1073/pnas.152694799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommer T, Rose M, Gläscher J, Wolbers T, & Büchel C (2005). Dissociable contributions within the medial temporal lobe to encoding of object-location associations. Learning & Memory (Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.), 12(3), 343–351. 10.1101/lm.90405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stam CJ, Nolte G, & Daffertshofer A (2007). Phase lag index: Assessment of functional connectivity from multi channel EEG and MEG with diminished bias from common sources. Human Brain Mapping, 28(11), 1178–1193. 10.1002/hbm.20346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summerfield C, & Mangels JA (2005). Coherent theta-band EEG activity predicts item-context binding during encoding. NeuroImage, 24(3), 692–703. 10.1016/J.NEUROIMAGE.2004.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treisman A (1998). Feature binding, attention and object perception. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 353(1373), 1295–1306. 10.1098/rstb.1998.0284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treisman AM, & Gelade G (1980). A feature-integration theory of attention. Cognitive Psychology, 12(1), 97–136. 10.1016/0010-0285(80)90005-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaidya AR, Pujara MS, Petrides M, Murray EA, & Fellows LK (2019). Lesion Studies in Contemporary Neuroscience. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 0(0). 10.1016/j.tics.2019.05.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voytek B, Soltani M, Pickard N, Kishiyama MM, & Knight RT (2012). Prefrontal Cortex Lesions Impair Object-Spatial Integration. PLoS ONE, 7(4), e34937. 10.1371/journal.pone.0034937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodman GF (2010). A brief introduction to the use of event-related potentials in studies of perception and attention. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 72(8), 2031–2046. 10.3758/BF03196680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X, Chen X, Li Z, Han S, & Zhang D (2007). Binding of verbal and spatial information in human working memory involves large-scale neural synchronization at theta frequency. NeuroImage, 35(4), 1654–1662. 10.1016/J.NEUROIMAGE.2007.02.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuval-Greenberg S, & Deouell LY (2007). What you see is not (always) what you hear: Induced gamma band responses reflect cross-modal interactions in familiar object recognition. Journal of Neuroscience, 27(5), 1090–1096. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4828-06.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou G, Lane G, Noto T, Arabkheradmand G, Gottfried JA, Schuele SU, … Zelano C (2019). Human olfactory-auditory integration requires phase synchrony between sensory cortices. Nature Communications, 10(1), 1168. 10.1038/s41467-019-09091-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zokaei N, Nour MM, Sillence A, Drew D, Adcock J, Stacey R, … Husain M (2019). Binding deficits in visual short-term memory in patients with temporal lobe lobectomy. Hippocampus, 29(2), 63–67. 10.1002/hipo.22998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.