Abstract

It is reported that microRNAs (miRNAs) play an important role in various human diseases. However, the mechanisms of miRNA in these diseases have not been fully understood. Therefore, detecting potential miRNA-disease associations has far-reaching significance for pathological development and the diagnosis and treatment of complex diseases. In this study, we propose a novel diffusion-based computational method, DF-MDA, for predicting miRNA-disease association based on the assumption that molecules are related to each other in human physiological processes. Specifically, we first construct a heterogeneous network by integrating various known associations among miRNAs, diseases, proteins, long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), and drugs. Then, more representative features are extracted through a diffusion-based machine-learning method. Finally, the Random Forest classifier is adopted to classify miRNA-disease associations. In the 5-fold cross-validation experiment, the proposed model obtained the average area under the curve (AUC) of 0.9321 on the HMDD v3.0 dataset. To further verify the prediction performance of the proposed model, DF-MDA was applied in three significant human diseases, including lymphoma, lung neoplasms, and colon neoplasms. As a result, 47, 46, and 47 out of top 50 predictions were validated by independent databases. These experimental results demonstrated that DF-MDA is a reliable and efficient method for predicting potential miRNA-disease associations.

Keywords: miRNA-disease association, machine learning, heterogeneous molecular network, random forest, diffusion model

Graphical abstract

miRNAs play important roles in many significant biological processes, and predicting potential miRNA-disease associations contributed to comprehending the molecular mechanism of human diseases. Li et al. introduce a novel diffusion-based method for predicting miRNA-disease associations based the heterogeneous biological network by combining multi-source information.

Introduction

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are a collection of small (about 23 nucleotides) non-coding RNAs.1 They generally act as negative or positive regulators in biological processes by connecting with 3′ UTR sites of the mRNAs.2 A great number of reports have demonstrated that miRNAs influence many critical biological processes, including cell diffusion,3 growth,4 divergence,5 death,6 and so on. Therefore, miRNAs have great effects on various biological progress.7, 8, 9

Recently, emerging evidence has shown that miRNAs are closely related to diseases and play an important role in complex human diseases.10, 11, 12 It has become a research hotspot to predict miRNA-disease associations.13, 14, 15 For example, Liu et al.16 demonstrated that hsa-miR-124-3p could effectively regulate the SOCS3 (suppressor of cytokine signaling 3), a tumor suppressor in breast neoplasms cells. Kumarswamy et al.17 detected that miR-21 is downregulated in almost all types of cancers, which led the miR-21 to become an attractive target for therapeutic strategies. Furthermore, miRNAs have been new biomarkers in human disease diagnosis, especially in the cancer field.18 Xie et al.19 discovered that miR-342-3p could inhibit lung cancer cell proliferation by targeting Ras-related protein Rap-2b, which may bring about a novel biomarker and treatment for lung cancer patients. Therefore, effectively identifying miRNA-disease associations could greatly promote the treatment of human complex diseases.20,21

With the development of biotechnology, a growing number of biological data were generated.22 Multiple databases (e.g., the Human MicroRNA Disease Database [HMDD],23 miR2Disease,24and Database of Differentially Expressed miRNAs in Human Cancers [dbDEMC]25) are formed by collecting these biological data.26 These databases supply a large amount of data verified by biological experiments, which makes predicting miRNA-disease associations by computational methods feasible.27 An increasing number of researchers use these known data to predict the association between miRNAs and diseases by computational methods. The most likely relationship between miRNAs and diseases would need to be verified by biological experiment, which could eliminate a large number of wrong answers and save valuable experimental costs.28, 29, 30 The best computational methods can even replace biological experiments and complete the prediction of the relationship between miRNAs and diseases with extremely high accuracy. For example, Jiang et al.31 developed a novel computational model for the prediction of miRNAs and diseases. However, this method excessively relied on the relationship among miRNAs, which greatly impact the results. Xuan et al.32 proposed a novel computational model of HDMP. Different from previous models, HDMP added weighted k most similarity neighbors of miRNAs, and the weight is determined by the similarity between miRNA and its neighbor, which could greatly improve the performance of model predictions. Nonetheless, HDMP becomes invalid to predict the diseases without any known related miRNAs. Chen et al.33 presented WBSMDA for predicting miRNA-disease associations. This model connected the within score and between score of the relationship between miRNA and disease. WBSMDA greatly improved the scope and prediction of the model and suitable for predicting new disease-miRNA associations. In addition, You et al.34 presented PBMDA to predict the potential relationship between miRNAs and diseases, which constructed a heterogeneous association network by integrating a large amount of biological data. PBMDA could well work for these new diseases with unknown related miRNAs and vice versa. What’s more, this model takes advantage of the topology information of the heterogeneous network by depth-first calculating based on the path. A model of RKNNMDA proposed by Chen et al.35 is a ranking-based K-nearest neighbor (KNN) method for predicting the association of miRNA and disease. These KNNs would be ranked by the support vector machine (SVM) ranking model to obtain the priority miRNA-disease relationships. In recent years, these proposed computational methods have made up for the time-consuming and costly traditional biological experiments to a certain degree.36

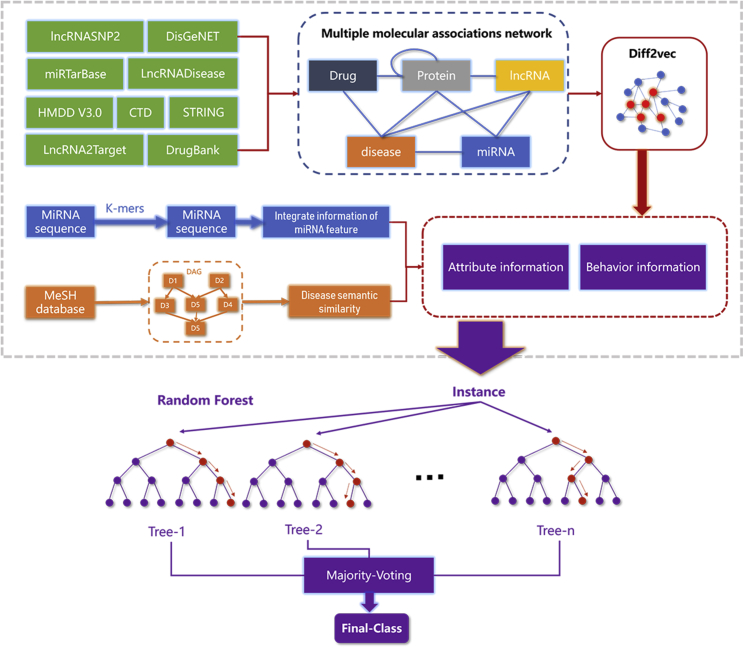

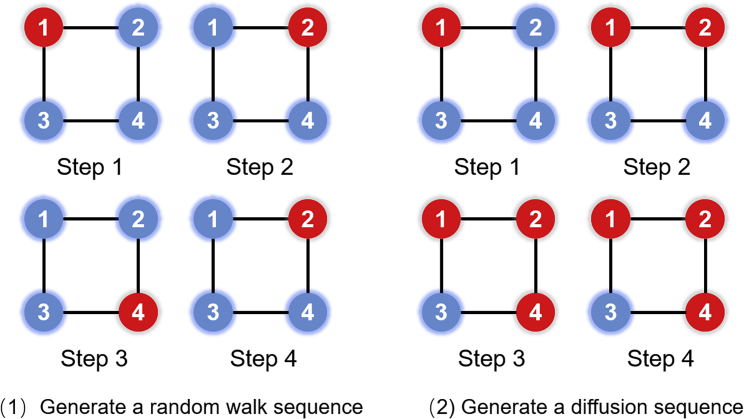

In this study, we developed a novel computational model, DF-MDA, for predicting miRNA-disease associations based on the assumption that molecules are related to each other in human physiological processes. The flow chart of DF-MDA is shown in Figure 1. More specifically, we first utilize a comprehensive molecular-associations network (MAN)37 to integrate various biological data and learning the behavior feature information of miRNAs and diseases in the network by the diffusion model. Then, based on the known miRNA and disease association, we construct a comprehensive feature descriptor by integrating the above information with miRNA sequence information and disease semantic similarity information. Finally, these feature descriptors are trained by the Random Forest (RF) classifier to accurately classify and predict the association between miRNAs and disease. In the experiment, DF-MDA obtained outstanding performance in 5-fold cross-validation (the average area under the curve [AUC] of 0.9321) based on the HMDD v3.0 database. To further evaluate the performance of the model, we compared the proposed model with different classifiers and feature extraction models. In addition, we implemented the case studies of lung neoplasms, colon neoplasms, and lymphoma neoplasms. As a result, 47, 46, and 47 out of top 50 miRNA candidates were verified by independent databases, respectively. The above experiment results demonstrated that the DF-MDA is a reliable and effective model to predict the association of miRNA and disease.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of DF-MDA to predict potential miRNA-disease associations

Results

Evaluation criteria

In order to more comprehensively evaluate the performance of the proposed model, we adopted a variety of evaluation criteria to assess DF-MDA, involving accuracy (Acc.), sensitivity (Sen.), specificity (Spec.), precision (Prec.), and Matthew’s correlation coefficient (MCC). These formulae of criteria were calculated as follows:

where true positive (TP), true negative (TN), false positive (FP) and false negative (FN) express the number of positive samples correctly predicted, negative samples correctly predicted, positive samples wrongly predicted, and negative samples wrongly predicted by the model, respectively. Furthermore, we also draw the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve and the AUC to describe the capability of DF-MDA.

Performance evaluation

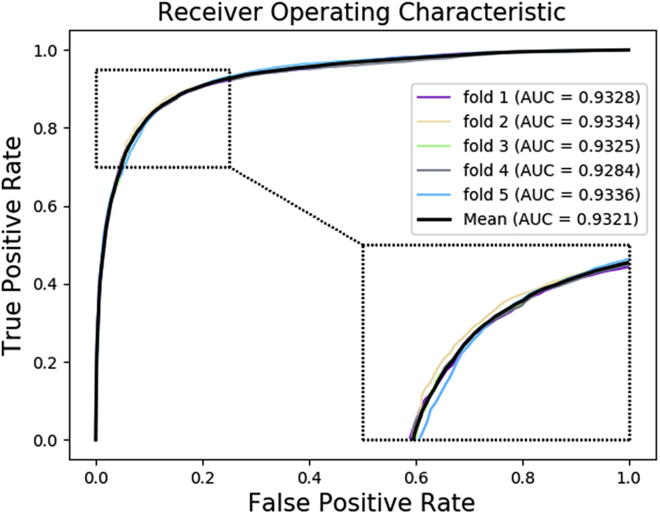

In this study, we implemented the 5-fold cross-validation methods based on known database HMDD v3.0 to evaluate the DF-MDA model. In this paper, we choose these verified miRNA-disease associations to be the positive samples and randomly selected the same number of uncorrelated miRNA-disease associations to be the negative samples. These pairs of miRNA-disease would be split into five uncrossed subsets. For each validation, four-fifths of them were regarded as a train set and the other was test in the classifier. To avoid the leakage of test information, we used the train set to construct the whole network. As a result, the Acc., Sen., Spec., Prec., MCC, and AUC achieved 86.50%, 87.41%, 85.58%, 85.85%, 73.01%, and 0.9321, with standard deviations of 0.37%, 0.66%, 0.74%, 0.58%, 0.74%, and 0.0021, respectively. The detailed result of the model under 5-fold cross-validation on HMDD v3.0 is shown in Table 1. Furthermore, the ROC curves generated by DF-MDA are shown in Figure 2. The above experiment results indicate that DF-MDA is an efficacious model to predict the potential relationship of miRNA-disease.

Table 1.

5-fold cross-validation results performed by DF-MDA on HMDD dataset

| Fold | Acc. (%) | Sen. (%) | Spec. (%) | Prec. (%) | MCC (%) | AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 86.32 | 87.10 | 85.54 | 85.77 | 72.65 | 0.9328 |

| 2 | 87.13 | 88.01 | 86.24 | 86.48 | 74.27 | 0.9334 |

| 3 | 86.17 | 87.61 | 84.72 | 85.15 | 72.37 | 0.9325 |

| 4 | 86.40 | 86.40 | 86.40 | 86.40 | 72.79 | 0.9284 |

| 5 | 86.46 | 87.91 | 85.01 | 85.44 | 72.95 | 0.9336 |

| Average | 86.50 ± 0.37 | 87.41 ± 0.66 | 85.58 ± 0.74 | 85.85 ± 0.58 | 73.01 ± 0.74 | 0.9321 ± 0.0021 |

Figure 2.

ROC curves performed by DF-MDA on HMDD dataset

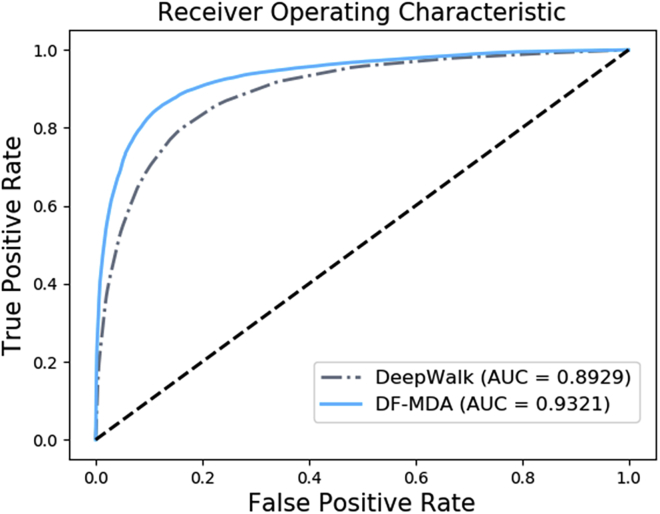

Comparison with DeepWalk model

In order to test the performance of the diffusion-based model, we compared the DF-MDA model with the DeepWalk model in the same dataset. DeepWalk38 is a classic network embedding model based on a random walk. The algorithm has been widely used in bioinformatics and achieved excellent results.39 In this experiment, we also used 5-fold cross-validation by the DeepWalk model based on HMDD v3.0. As a result, the DeepWalk model achieved an average AUC of 0.8929. As shown in Table 2, the performance of DF-MDA is better than that of DeepWalk for predicting miRNA-disease associations. The reason for this result is that the DeepWalk model is mainly concerned with the local characteristics of the network, while the DF-MDA model extracts the more comprehensive feature of nodes in the molecular association network. The accuracy of DF-MDA is 4.57% higher than the DeepWalk model, and the sensitivity of our method is 8.70% higher than the DeepWalk model. The performance comparisons in 5-fold cross-validation are shown in Figure 3.

Table 2.

The comparison results between DeepWalk and DF-MDA model by Random Forest classifier based on HMDD database

| Model | Acc. (%) | Sen. (%) | Spec. (%) | Prec. (%) | MCC (%) | AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DeepWalk | 81.93 ± 0.56 | 78.70 ± 0.71 | 85.15 ± 1.05 | 84.14 ± 0.92 | 63.99 ± 1.15 | 0.8929 ± 0.0047 |

| DF-MDA | 86.50 ± 0.37 | 87.41 ± 0.66 | 85.58 ± 0.74 | 85.85 ± 0.58 | 73.01 ± 0.74 | 0.9321 ± 0.0021 |

Figure 3.

ROC curves performed by DeepWalk and DF-MDA by Random Forest classifier based on HMDD database

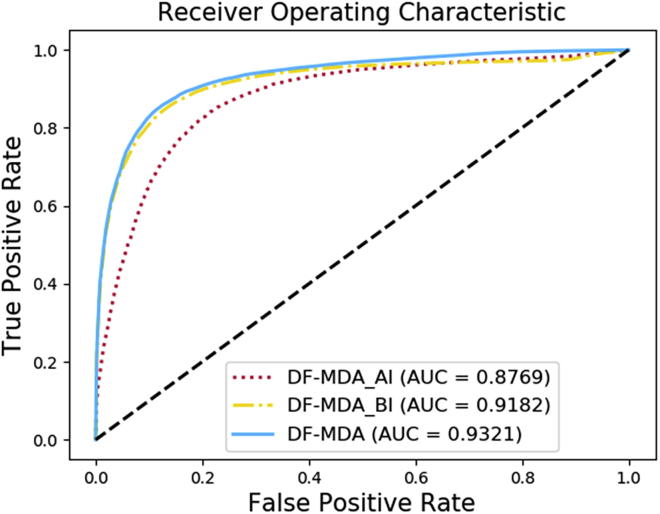

Comparison with different feature descriptor models

In this study, every node is described by its inherent attribute information and the behavior information in the whole network. To test their influence on the performance of DF-MDA, we compared the different feature descriptors with only attribute information (DF-MDA_AI), only behavior information (DF-MDA_BI) and both of them (DF-MDA), respectively. We assume the attribute information of other nodes has almost no impact on the predictive performance of the proposed model. In this work, we only adopt the attribute feature information of miRNAs and diseases. The detailed result of different feature descriptor models based on HMDD v3.0 is shown in Table 3. As shown in the table, the AUC of DF-MDA is 0.0552 and 0.0138 higher than that of DF-MDA_AI and DF-MDA_BI, respectively, and the accuracy of DF-MDA is 5.23% and 0.74% higher than that of DF-MDA_AI and DF-MDA_BI, respectively. The reason for this result is that the DF-MDA_AI predicts the relationships between miRNAs and diseases by the miRNA attribute information and disease semantic similarity, which could capture the properties of the node itself. However, the DF-MDA_AI ignores these known associations in the network, which is unable to provide comprehensive information for our prediction. The same situation exists in DF-MDA_BI, which lacks the attribute information of nodes. The ROC curves of the three experiments are shown in Figure 4. In conclusion, the performances in DF-MDA of AUCs are more outstanding than the model of feature descriptor with only one information.

Table 3.

The comparison results between DF-MDA_AI model, DF-MDA_BI model and DF-MDA model based on HMDD database

| Model | Acc. (%) | Sen. (%) | Spec. (%) | Prec. (%) | MCC (%) | AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DF-MDA_AI | 81.27 ± 0.58 | 83.71 ± 0.75 | 78.84 ± 0.65 | 79.82 ± 0.57 | 62.63 ± 1.16 | 0.8769 ± 0.0052 |

| DF-MDA_BI | 85.74 ± 0.39 | 82.48 ± 0.67 | 88.99 ± 0.35 | 88.23 ± 0.35 | 71.63 ± 0.76 | 0.9183 ± 0.0030 |

| DF-MDA | 86.50 ± 0.37 | 87.41 ± 0.66 | 85.58 ± 0.74 | 85.85 ± 0.58 | 73.01 ± 0.74 | 0.9321 ± 0.0021 |

Figure 4.

ROC curves performed by DF-MDA_AI model, DF-MDA_BI model, and DF-MDA model based on HMDD database

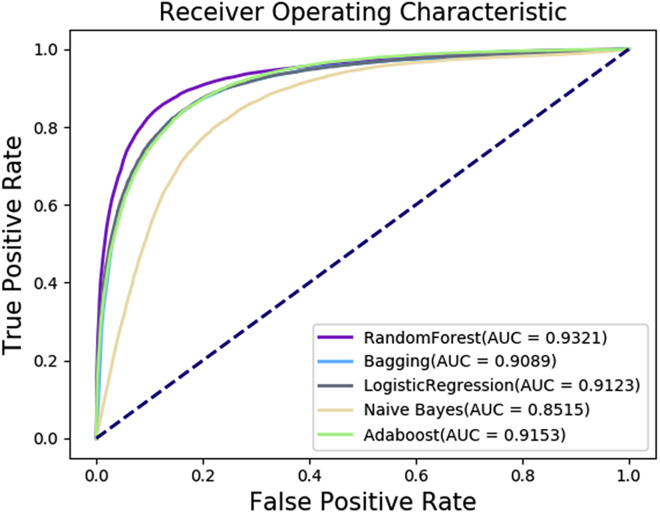

Comparison with different classifier models

DF-MDA adopted the Random Forest classifier to train and classify the potential miRNA-disease associations. To evaluate the performance of the Random Forest model, we compared it with Bagging, LogisticRegression, Naive Bayes, and AdaBoost classifier models. We implemented 5-fold cross-validation by all above models on the same training set and test set. As a result, Random Forest yielded an average AUC of 5-fold cross-validation of 0.9321 and outperformed Bagging (0.9089), LogisticRegression (0.9124), Naive Bayes (0.8505), and AdaBoost (0.9153). The Random Forest is only worse than Bagging of Spec., and the accuracy is 2.54% higher than that of the second-highest method. The explanation for this phenomenon is that Random Forest can handle very high dimensional data. Furthermore, the model has strong generalization ability due to adopting the unbiased estimation for generalization error in creating a random forest. It is worth mentioning that the Naive Bayes model is lower than other algorithms. The reason is that the Naive Bayes assumes that the features are independent of each other, which is often not true in reality. The detailed results of different classifier models are shown in Table 4. Furthermore, we drew the ROC curve as shown in Figure 5. These results have demonstrated that DF-MDA by Random Forest classifier has achieved the best performance, particularly in Acc., MCC, and AUC. From the information above, the Random Forest classifier is more appropriate for DF-MDA.

Table 4.

The comparison results between Random Forest and other classifier models (Bagging, LogisticRegression, Naive Bayes, and AdaBoost) based on HMDD database

| Model | Acc. (%) | Sen. (%) | Spec. (%) | Prec. (%) | MCC (%) | AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest | 86.50 ± 0.37 | 87.41 ± 0.66 | 85.58 ± 0.74 | 85.85 ± 0.58 | 73.01 ± 0.74 | 0.9321 ± 0.0021 |

| Bagging | 83.90 ± 0.52 | 81.26 ± 1.06 | 86.53 ± 0.45 | 85.79 ± 0.40 | 67.89 ± 1.01 | 0.9089 ± 0.0012 |

| LogisticRegression | 83.96 ± 0.39 | 83.44 ± 0.80 | 84.48 ± 0.78 | 84.32 ± 0.61 | 67.93 ± 0.78 | 0.9124 ± 0.0014 |

| Naive Bayes | 78.67 ± 0.42 | 85.40 ± 0.75 | 71.94 ± 0.46 | 75.27 ± 0.33 | 57.86 ± 0.87 | 0.8515 ± 0.0079 |

| AdaBoost | 83.81 ± 0.17 | 83.32 ± 0.51 | 84.29 ± 0.62 | 84.14 ± 0.45 | 67.62 ± 0.34 | 0.9153 ± 0.0038 |

Figure 5.

ROC curves performed by Random Forest and other classifiers (Bagging, LogisticRegression, Naive Bayes, and AdaBoost) based on HMDD database

Comparison with related works

At present, an increasing number of computational methods have been proposed for predicting miRNA-disease associations. Therefore, in order to further evaluate the performance of our model, we compared the proposed method with seven previous works, including RWRMDA,40 MTDN,41 EGBMMDA,42 LMTRDA,43 DBMDA,44 PBMDA,45 and CGMDA.46 Since these algorithms have not calculated multiple evaluation criteria, we only compared the AUC on the terms of the 5-fold cross-validation-based HMDD database. As shown in Table 5, the performance of DF-MDA is outstanding compared with other methods, and the proposed method is 0.0282 higher than the average AUC of all algorithms. This is because the proposed model combines the attribute information and behavior information of miRNAs and diseases and extracts the feature more comprehensively.

Table 5.

The comparison results between DF-MDA with other related works

| Method | AUC |

|---|---|

| RWRMDA | 0.8617 |

| MTDN | 0.8872 |

| EGBMMDA | 0.9048 |

| LMTRDA | 0.9054 |

| DBMDA | 0.9129 |

| PBMDA | 0.9172 |

| CGMDA | 0.9099 |

| DF-MDA | 0.9321 |

Case studies

In this work, we carry out three important human diseases (lung neoplasms, colon neoplasms, and lymphoma) by DF-MDA based on HMDD v3.0 to further evaluate its predictive power. These known miRNA-disease associations are used as the training dataset, and the test dataset includes the association pairs of three diseases and all possible miRNAs. In this study, we verified the top 50 candidate miRNAs by two independent databases (dbDEMC25 and miR2Disease24). In three case studies, most candidate-related miRNAs were confirmed, demonstrating that DF-MDA is a reliable model for predicting the association of miRNA and disease.

Lung neoplasm is the second most common cancer in humans (~13% of all) except for skin cancers, and the number of deaths caused by lung cancer is the highest (~24% of all).47 In 2019, there are about 228,150 new lung cancer cases (116,440 of men and 111,710 of women) and 142,670 deaths for lung cancer (76,650 of men and 66,020 of women) in the United States. An increasing amount of research pays attention to the prediction of the potential relationship between miRNAs and lung neoplasms.48 Therefore, we implemented a case study of lung neoplasms by DF-MDA for more miRNA based on HMDD v3.0, and the details of the result are shown in Table 6, in which 47 of top 50 candidates were verified based on the independent database.

Table 6.

Prediction of the top 50 miRNAs related to lung neoplasms based on known miRNA-disease associations in HMDD database

| Rank | miRNA | Evidence | Rank | miRNA | Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | hsa-mir-106b-5p | dbDEMC | 26 | hsa-mir-302b-5p | dbDEMC |

| 2 | hsa-mir-204-5p | dbDEMC | 27 | hsa-mir-501-5p | dbDEMC |

| 3 | hsa-mir-181b-5p | dbDEMC | 28 | hsa-mir-302f | dbDEMC |

| 4 | hsa-mir-15b-5p | dbDEMC | 29 | hsa-mir-367-3p | dbDEMC |

| 5 | hsa-mir-16-1-3p | dbDEMC | 30 | hsa-mir-363-3p | dbDEMC |

| 6 | hsa-mir-193b-5p | dbDEMC | 31 | hsa-mir-449b-5p | dbDEMC |

| 7 | hsa-mir-23b-5p | dbDEMC | 32 | hsa-mir-429 | dbDEMC |

| 8 | hsa-mir-424-5p | dbDEMC | 33 | hsa-mir-1271-5p | dbDEMC |

| 9 | hsa-mir-20b-5p | dbDEMC | 34 | hsa-mir-125b-2-3p | dbDEMC |

| 10 | hsa-mir-28-5p | dbDEMC | 35 | hsa-mir-484 | dbDEMC |

| 11 | hsa-mir-296-5p | dbDEMC | 36 | hsa-mir-518b | dbDEMC |

| 12 | hsa-mir-452-5p | dbDEMC | 37 | hsa-mir-378a-5p | dbDEMC |

| 13 | hsa-mir-483-5p | dbDEMC | 38 | hsa-mir-376b-5p | dbDEMC |

| 14 | hsa-mir-329-3p | dbDEMC | 39 | hsa-mir-302a-5p | unconfirmed |

| 15 | hsa-mir-590-5p | dbDEMC | 40 | hsa-mir-450a-1-3p | unconfirmed |

| 16 | hsa-mir-383-5p | dbDEMC | 41 | hsa-mir-539-5p | dbDEMC |

| 17 | hsa-mir-211-5p | dbDEMC | 42 | hsa-mir-425-5p | dbDEMC |

| 18 | hsa-mir-491-5p | dbDEMC | 43 | hsa-mir-339-5p | dbDEMC |

| 19 | hsa-mir-373-3p | dbDEMC | 44 | hsa-mir-455-5p | dbDEMC |

| 20 | hsa-mir-302c-3p | dbDEMC | 45 | hsa-mir-128-1-5p | dbDEMC |

| 21 | hsa-mir-16-2-3p | dbDEMC | 46 | hsa-mir-500a-5p | dbDEMC |

| 22 | hsa-mir-19b-2-5p | unconfirmed | 47 | hsa-mir-370-5p | dbDEMC |

| 23 | hsa-mir-92a-2-5p | dbDEMC | 48 | hsa-mir-376a-5p | dbDEMC |

| 24 | hsa-mir-454-5p | dbDEMC | 49 | hsa-mir-345-5p | dbDEMC |

| 25 | hsa-mir-508-5p | dbDEMC | 50 | hsa-mir-584-5p | dbDEMC |

Colon neoplasm is the third most common cancer in the United States (~8% of new cancer) except for skin cancer.47 In 2019, it is expected that about 145,600 people will develop colon cancer (78,500 men and 67,100 women) and there will be about 51,020 deaths from colon cancer (27,640 men and 23,380 women). Recently, increasing researchers have indicated that miRNAs are related with colon neoplasms.49 Thus, we used DF-MDA to predict more colon neoplasm-related miRNAs to verify its performance, and the details of the result is shown in Table 7, in which 46 of top 50 candidates were confirmed based on the independent database.

Table 7.

Prediction of the top 50 miRNAs related to colon neoplasms based on known miRNA-disease associations in HMDD database

| Rank | miRNA | Evidence | Rank | miRNA | Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | hsa-mir-182-5p | dbDEMC | 26 | hsa-mir-484 | dbDEMC |

| 2 | hsa-mir-29c-5p | dbDEMC | 27 | hsa-mir-452-5p | dbDEMC |

| 3 | hsa-mir-193b-5p | dbDEMC | 28 | hsa-mir-27b-5p | dbDEMC |

| 4 | hsa-mir-206 | dbDEMC | 29 | hsa-mir-30e-5p | dbDEMC |

| 5 | hsa-mir-122-5p | dbDEMC | 30 | hsa-mir-134-5p | dbDEMC |

| 6 | hsa-mir-214-5p | dbDEMC | 31 | hsa-mir-181c-5p | dbDEMC |

| 7 | hsa-mir-139-5p | dbDEMC | 32 | hsa-mir-99b-5p | dbDEMC |

| 8 | hsa-mir-497-5p | dbDEMC | 33 | hsa-mir-99a-5p | dbDEMC |

| 9 | hsa-mir-34c-5p | dbDEMC | 34 | hsa-mir-373-5p | dbDEMC |

| 10 | hsa-mir-183-5p | dbDEMC | 35 | hsa-mir-212-5p | dbDEMC |

| 11 | hsa-mir-423-5p | dbDEMC | 36 | hsa-mir-144-5p | dbDEMC |

| 12 | hsa-mir-100-5p | dbDEMC | 37 | hsa-mir-92a-2-5p | dbDEMC |

| 13 | hsa-mir-16-5p | dbDEMC | 38 | hsa-mir-92b-5p | dbDEMC |

| 14 | hsa-mir-9-5p | dbDEMC | 39 | hsa-mir-381-5p | unconfirmed |

| 15 | hsa-mir-149-5p | dbDEMC | 40 | hsa-mir-135a-5p | dbDEMC |

| 16 | hsa-mir-491-5p | dbDEMC | 41 | hsa-mir-10a-5p | dbDEMC |

| 17 | hsa-mir-124-5p | dbDEMC | 42 | hsa-mir-199b-5p | dbDEMC |

| 18 | hsa-mir-130b-5p | dbDEMC | 43 | hsa-mir-301a-5p | unconfirmed |

| 19 | hsa-mir-34b-5p | dbDEMC | 44 | hsa-mir-425-5p | dbDEMC |

| 20 | hsa-mir-146b-5p | dbDEMC | 45 | hsa-mir-542-5p | dbDEMC |

| 21 | hsa-mir-199a-5p | dbDEMC | 46 | hsa-mir-20b-5p | dbDEMC |

| 22 | hsa-mir-342-5p | dbDEMC | 47 | hsa-mir-340-5p | dbDEMC |

| 23 | hsa-mir-494-5p | dbDEMC | 48 | hsa-mir-181b-2-3p | unconfirmed |

| 24 | hsa-mir-26a-5p | dbDEMC | 49 | hsa-mir-338-5p | dbDEMC |

| 25 | hsa-mir-26b-5p | dbDEMC | 50 | hsa-mir-367-5p | unconfirmed |

Lymphoma is one of the most common malignant cancers (~4% of all new cancers), especially in teenagers in the United States.47 In 2019, it is estimated that there will be about 74,200 new cases of lymphoma (41,090 of men and 33,110 of women) and 19,970 deaths from lymphoma (11,510 men and 8,460 women). Lymphoma mainly contains two types of Hodgkin’s lymphoma (HL) and non-HL (NHL).50 Therefore, we selected lymphoma as a case study to verify the performance of DF-MDA. The details of the result are shown in Table 8, in which 47 of top 50 candidates were proved based on the independent database.

Table 8.

Prediction of the top 50 miRNAs related to lymphoma based on known miRNA-disease associations in HMDD database

| Rank | miRNA | Evidence | Rank | miRNA | Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | hsa-mir-34a-5p | dbDEMC | 26 | hsa-let-7b-5p | dbDEMC |

| 2 | hsa-mir-125b-5p | dbDEMC | 27 | hsa-mir-96-5p | dbDEMC |

| 3 | hsa-mir-107 | dbDEMC | 28 | hsa-let-7g-5p | dbDEMC |

| 4 | hsa-mir-27a-5p | unconfirmed | 29 | hsa-mir-429 | unconfirmed |

| 5 | hsa-mir-195-5p | dbDEMC | 30 | hsa-mir-192-5p | dbDEMC |

| 6 | hsa-mir-145-5p | dbDEMC | 31 | hsa-mir-125b-2-3p | dbDEMC |

| 7 | hsa-mir-106b-5p | dbDEMC | 32 | hsa-mir-30b-5p | dbDEMC |

| 8 | hsa-let-7a-5p | dbDEMC | 33 | hsa-mir-424-5p | dbDEMC |

| 9 | hsa-mir-29a-5p | dbDEMC | 34 | hsa-mir-146b-5p | dbDEMC |

| 10 | hsa-mir-182-5p | dbDEMC | 35 | hsa-mir-24-3p | dbDEMC |

| 11 | hsa-mir-34b-5p | dbDEMC | 36 | hsa-mir-339-5p | dbDEMC |

| 12 | hsa-mir-205-5p | dbDEMC | 37 | hsa-mir-148a-5p | dbDEMC |

| 13 | hsa-mir-9-5p | dbDEMC | 38 | hsa-mir-100-5p | dbDEMC |

| 14 | hsa-mir-183-5p | dbDEMC | 39 | hsa-mir-23a-5p | dbDEMC |

| 15 | hsa-mir-106a-5p | dbDEMC | 40 | hsa-mir-206 | dbDEMC |

| 16 | hsa-let-7c-5p | dbDEMC | 41 | hsa-mir-199b-5p | dbDEMC |

| 17 | hsa-mir-218-5p | dbDEMC | 42 | hsa-mir-335-5p | dbDEMC |

| 18 | hsa-mir-141-5p | unconfirmed | 43 | hsa-mir-181b-5p | dbDEMC |

| 19 | hsa-mir-15b-5p | dbDEMC | 44 | hsa-mir-34c-5p | dbDEMC |

| 20 | hsa-mir-223-5p | dbDEMC | 45 | hsa-mir-214-5p | dbDEMC |

| 21 | hsa-mir-124-5p | dbDEMC | 46 | hsa-mir-30c-5p | dbDEMC |

| 22 | hsa-mir-30a-5p | dbDEMC, miR2Disease | 47 | hsa-mir-181d-5p | dbDEMC |

| 23 | hsa-mir-340-5p | dbDEMC | 48 | hsa-let-7e-5p | dbDEMC |

| 24 | hsa-mir-378a-5p | dbDEMC | 49 | hsa-mir-191-5p | dbDEMC |

| 25 | hsa-mir-196a-5p | dbDEMC | 50 | hsa-mir-125b-1-3p | dbDEMC |

Discussion

Recently, an accumulating amount of research demonstrated that miRNAs have a close link with diseases. In this work, we proposed the diffusion-based computational model DF-MDA for predicting miRNA-disease associations. This model can extract effective features of miRNAs and diseases from a complex heterogeneous network, including miRNA, disease, drug, protein, and long non-coding RNA (lncRNA), and the Random Forest classifier was adopted to classify the potential miRNA-disease associations. Compared with other classifiers and feature extraction models, DF-MDA shows excellent performance. In addition, in the case study of lung neoplasms, colon neoplasms, and lymphomas, 47, 46, and 47 of top 50 miRNA candidates predicted by DF-MDA were verified in the independent database, respectively. These results indicated that DF-MDA can be used as a valuable model for predicting miRNA-disease associations.

There are some reasons for the remarkable predictive power of DF-MDA. First, unlike previous studies, we combined multiple molecular-association datasets to construct a comprehensive network of more than just miRNAs and diseases. It is worth noting that DF-MDA not only uses the attribute information of miRNAs and diseases, but also adopts their behavior information for predicting the potential relationship between them. Second, the behavior information of biological molecular was extracted by the diffusion-based model, which could effectively detect the network structure by generating more informative traces. Additionally, DF-MDA is suitable for new diseases with unknown related miRNAs and new miRNAs with unknown related diseases. However, limitations also exist in the model. First, the relationship evidence of miRNAs and diseases are still insufficient for prediction. The prediction performance of DF-MDA would improve with the amount of biological data increasing in future work. Furthermore, the miRNA sequence information extraction method also influences the performance of our approach.

Materials and methods

Human miRNA-disease associations database

In this study, we implement the model on the HMDD v3.023 database. The HMDD database supplies plenty of experimentally verified miRNA-disease associations, which can be freely obtained from http://www.cuilab.cn/hmdd. Currently, HMDD has collected 32,281 verified miRNA-disease associations, including 1,102 miRNAs and 850 diseases from 17,412 papers. After removing redundancy and simplifying, we obtained 16,427 miRNA-disease associations, involving 1,023 miRNAs and 850 diseases. In the experiment, we use the adjacency matrix to represent the miRNA-disease association. When the miRNA is confirmed to be related with disease , the is equal to 1, otherwise 0.

MAN

In this experiment, we used the MAN to integrate multiple biological data. The MAN is a large heterogeneous network proposed by Guo et al.37 This complex network consists of various nodes and edges based on the associations among them. It provides a novel frame to identify the potential association between any research object in the network. Through this molecular-association network, a comprehensive perspective is obtained to understand human biological progress and disease treatment. At present, MAN integrates five different kinds of molecules (miRNA, disease, lncRNA, protein, and drug) and associations between them. The details of different types of molecules are shown in Table 9, and associations between them are shown in Table 10.

Table 9.

The number of different types of nodes in MAN

| Node | Number of nodes |

|---|---|

| miRNA | 1,023 |

| Disease | 2,026 |

| Drug | 1,025 |

| Protein | 1,647 |

| lncRNA | 769 |

| Total | 6,528 |

Table 10.

The number of different types of associations in MAN

| Association | Database | Amounts of relationships |

|---|---|---|

| miRNA-disease | HMDD51 | 16,427 |

| miRNA-protein | miRTarBase52 | 4,944 |

| Drug-protein | DrugBank53 | 11,107 |

| lncRNA-disease | lncRNADisease54, lncRNASNP255 | 1,264 |

| Protein-protein | STRING56 | 19,237 |

| miRNA-lncRNA | lncRNASNP255 | 8,374 |

| lncRNA-protein | lncRNA2Target57 | 690 |

| Drug-disease | CTD58 | 18,416 |

| Protein-disease | DisGeNET59 | 25,087 |

| Total | – | 105,546 |

Vector representation of miRNA sequences

To more comprehensively describe the features of miRNAs, we introduced the sequence information of the miRNA. In this study, we downloaded all miRNA sequences in MAN from the miRbase60 and converted miRNA sequences to vectors by the k-mers method. The k-mers could divide the sequence into a train of subsequences with k bases.61 Given a sequence of length , the sequence could be divided into k-mers. In this experiment, conjoint triads (3-mer) of miRNA were extracted from sequences. There are four bases of miRNA: and , therefore, 3-mers could split the sequence of miRNA into . First, dividing the miRNA sequence into some conjoint triads was based on a slipping window. Then, we calculated the frequency of each sub-sequence and normalized these data. In this way, we converted the miRNA sequence information into a 64-dimensional numerical vector to represent miRNA attribute information.

Disease semantic similarity

To accurately describe the features of diseases, we obtained the disease semantic similarity information from the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) database,62 which provided an effective disease classification system. In this system, diseases could be represented by related directed acyclic graph (DAG).63 The relationship between two diseases could be indicated by a directed edge pointing to child nodes by parent nodes. Suppose , where indicates the node set containing all diseases of and indicates the edge set of all relationships of . The semantic value of disease was contributed by disease as the formula

| (1) |

Here, is the semantic contribution factor; the contribution value of to itself is set as . Therefore, we can obtain the sum of :

| (2) |

According to the assumption that diseases with more same parts in their DAGs should hold higher similarity of them, we can obtain the semantic similarity among and by the following formula:

| (3) |

Then, we used the disease semantic similarity to express the attribute information of disease, and this process exists dimensional reduction by stacked autoencoder. The attribute information of diseases is also converted as a 64-dimensional vector.

Diffusion-based network embedding

In order to extract the comprehensive feature from the MAN, we adopted a diffusion-based network embedding. First of all, the complex heterogeneous network was constructed, including 6,528 nodes and 102,261 edges. Then, the 6,528-dimensional frequency vector before and after each node in the graph was obtained by the diffusion progress of the subgraph. To unify the dimensions of the feature vector, we used a neural network to process these frequency vectors. The input of the neural network is 6,528 one-hot vectors, and the output is the vector fusing the before and after frequency vector. Finally, we obtained a 64-dimensional vector to represent the behavior information of miRNAs and diseases.

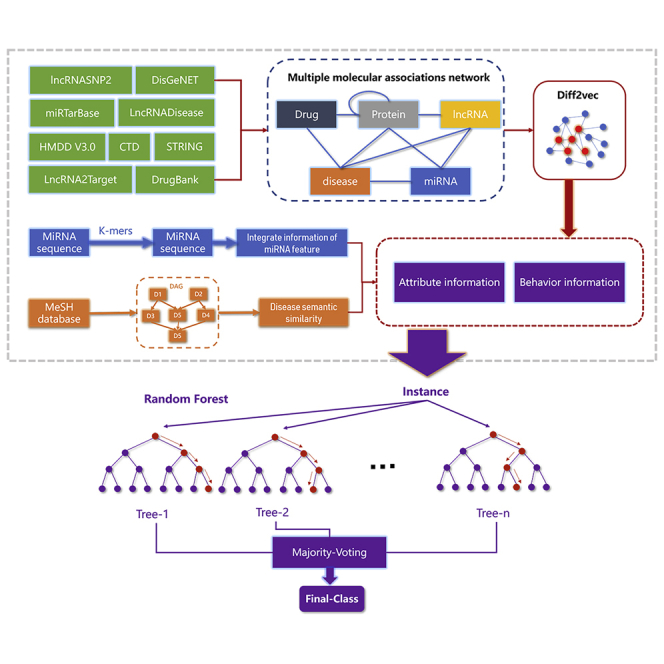

The diffusion process for generating sequences

Previous studies have indicated that Random Walk is a depth-first algorithm that could repeatedly visit nodes. However, the original network structure is hardly reflected by the node similarity defined by a random walk. The diffusion could efficiently detect the network structure by generating more informative traces.64

Suppose a given graph is defined as , where indicates the vertices set containing all nodes of and represents the edge set of . The diffusion graph is defined as , and the seed node is . The maximal walking step is supposing as . In every step, we chose a random node from as diffusion source and , a random neighbor of , from as diffusion object. Then, the diffusion object and the edge (, ) would be added to the diffusion graph . We compared the generating sequence process of random walk and diffusion as shown in Figure 2. The walking step is set as four in this example. In Figure 6 (1), the walker is starting from , and the red node is the location of the walker. After a random walk process, it is obvious that the generated sequence is (, , , ). In Figure 6 (2), we imitate the diffusion process by a graph with four nodes, and the initial diffusion source also is . Unlike the single trace of random walk, all sampled nodes would be retained and may become a diffusion source in the next step in the diffusion process. The diffusion could generate a sequence of ((), (, ), (, , ), (, , )). As we can see in this example, if the step , the would not be visited in a random walk, which is a disadvantage of the single-trace algorithm. However, as the diffusion graph contained the neighbor of the node , the is possible to be visited.

Figure 6.

Example of generating sequence of random walk model and diffusion model

To obtain the sequence, we doubled each edge in the diffusion graph . Then, the degree of each node is even, and there must be a Euler walk. This Euler walk would be the diffusion sequence that preserved the relationship of adjacent nodes. In this work, we set the walk length as 10, and the vertex-set-cardinality is equal to 80.

Feature extraction and network embedding

Given a set of node sequences, the feature is extracted by the sliding window. To more comprehensively detect the information of the network, we design the visit frequency vector by counting the frequency of other nodes before and after the node . For example, there is a set of sequences with five nodes as follows:

In this example, the size of the sliding window is set as 1, and we would demonstrate the visit frequency vector of . As a result, the frequency vector of before and after the node is as follows:

where and represent the frequency of occurrence before and after , respectively. Then, these two vectors would be concatenated as a visit frequency vector .

In this study, we develop a neural network to learn an embedding from the feature. For each node , we set as follows:

| (4) |

Here, and are the regulated parameters, and is the incoming weight matrices of the hidden neurons. The output function is as shown:

| (5) |

Then, we define the loss function as

| (6) |

Finally, the minimization objective could be obtained as shown:

| (7) |

Integration of feature information

To comprehensively describe the potential information of each node, we extracted feature descriptors from the two kinds of information of them. On the one hand is the attribute information, including the sequence information of miRNAs and the semantic similarity of diseases . On the other hand, the behavior information and were extracted by the diffusion-based model. Finally, we integrated the above information into a comprehensive feature descriptor based on known miRNA-disease associations from the HMDD v3.0 database. The feature descriptor can be defined by a 256-dimensional vector as follows:

| (8) |

Random Forest classifier

Random Forest is an important integrated machine learning algorithm proposed by Breiman et al.,65 which can be used for classification and regression problems. The Random Forest has been widely used in bioinformatics with reliable performance.66 The algorithm first randomly selects bootstrap samples from the original samples as the training set. Second, Random Forest randomly selects variables from each bootstrap sample and split nodes by the random subspace method. By this method, an unpruned classification tree is grown for each sample. Finally, Random Forest obtains prediction results by a majority vote according to these decision trees. Specifically, we adopted a 256-dimensional feature descriptor to represent each sample in the training set. In this study, we selected the optimal parameter as 99 by the grid search method to implement the final classification prediction task.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported is supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under grant 61702444; the West Light Foundation of the Chinese Academy of Sciences under grant 2018-XBQNXZ-B-008; the Chinese Postdoctoral Science Foundation under grant 2019M653804; the Tianshan Youth - Excellent Youth under grant 2019Q029; and by the Qingtan Scholar Talent Project of Zaozhuang University. The authors would like to thank all anonymous reviewers for their constructive advice.

Author contributions

H.-Y.L. wrote the paper; Z.-H.Y. and X.Y. designed the experiments; L.W. and Z.L. conducted the experiments.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Contributor Information

Zhu-Hong You, Email: zhuhongyou@ms.xjb.ac.cn.

Lei Wang, Email: leiwang@ms.xjb.ac.cn.

Xin Yan, Email: xinyanuzz@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Kloosterman W.P., Plasterk R.H.A. The diverse functions of microRNAs in animal development and disease. Dev. Cell. 2006;11:441–450. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ambros V. microRNAs: tiny regulators with great potential. Cell. 2001;107:823–826. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00616-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheng A.M., Byrom M.W., Shelton J., Ford L.P. Antisense inhibition of human miRNAs and indications for an involvement of miRNA in cell growth and apoptosis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:1290–1297. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karp X., Ambros V. Developmental biology. Encountering microRNAs in cell fate signaling. Science. 2005;310:1288–1289. doi: 10.1126/science.1121566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miska E.A. How microRNAs control cell division, differentiation and death. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2005;15:563–568. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2005.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xu P., Guo M., Hay B.A. MicroRNAs and the regulation of cell death. Trends Genet. 2004;20:617–624. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2004.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen X., Xie D., Wang L., Zhao Q., You Z.-H., Liu H. BNPMDA: bipartite network projection for MiRNA-disease association prediction. Bioinformatics. 2018;34:3178–3186. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen X., Xie D., Zhao Q., You Z.-H. MicroRNAs and complex diseases: from experimental results to computational models. Brief Bioinform. 2019;20:515–539. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbx130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen X., Wang C.-.C., Yin J., You Z.-H. Novel human miRNA-disease association inference based on random forest. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids. 2018;13:568–579. doi: 10.1016/j.omtn.2018.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garzon R., Marcucci G., Croce C.M. Targeting microRNAs in cancer: rationale, strategies and challenges. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2010;9:775–789. doi: 10.1038/nrd3179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gong Y., Niu Y., Zhang W., Li X. A network embedding-based multiple information integration method for the MiRNA-disease association prediction. BMC Bioinformatics. 2019;20:468. doi: 10.1186/s12859-019-3063-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang F., Yue X., Xiong Z., Yu Z., Liu S., Zhang W. Tensor decomposition with relational constraints for predicting multiple types of microRNA-disease associations. Brief Bioinform. 2020;2020 doi: 10.1093/bib/bbaa140. bbaa140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen X., Zhang D.-H., You Z.-H. A heterogeneous label propagation approach to explore the potential associations between miRNA and disease. J. Transl. Med. 2018;16:348. doi: 10.1186/s12967-018-1722-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zheng K., You Z.-H., Wang L., Guo Z.-H. iMDA-BN: Identification of miRNA-Disease Associations based on the Biological Network and Graph Embedding Algorithm. Comp. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2020;18:2391–2400. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2020.08.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wong L., You Z.-H., Guo Z.-H., Yi H.-C., Chen Z.-H., Cao M.-Y. MIPDH: A Novel Computational Model for Predicting microRNA–mRNA Interactions by DeepWalk on a Heterogeneous Network. ACS Omega. 2020;5:17022–17032. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.9b04195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu Y.X., Wang L., Liu W.J., Zhang H.T., Xue J.H., Zhang Z.W., Gao C.J. MiR-124-3p/B4GALT1 axis plays an important role in SOCS3-regulated growth and chemo-sensitivity of CML. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2016;9:69. doi: 10.1186/s13045-016-0300-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kumarswamy R., Volkmann I., Thum T. Regulation and function of miRNA-21 in health and disease. RNA Biol. 2011;8:706–713. doi: 10.4161/rna.8.5.16154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pereira D.M., Rodrigues P.M., Borralho P.M., Rodrigues C.M. Delivering the promise of miRNA cancer therapeutics. Drug Discov. Today. 2013;18:282–289. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2012.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xie X., Liu H., Wang M., Ding F., Xiao H., Hu F., Hu R., Mei J. miR-342-3p targets RAP2B to suppress proliferation and invasion of non-small cell lung cancer cells. Tumour Biol. 2015;36:5031–5038. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-3154-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen X., Gong Y., Zhang D.-H., You Z.-H., Li Z.-W. DRMDA: deep representations-based miRNA–disease association prediction. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2018;22:472–485. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.13336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang W., Li Z., Guo W., Yang W., Huang F. 2019. A fast linear neighborhood similarity-based network link inference method to predict microRNA-disease associations. IEEE/ACM Trans. Comput. Biol. Bioinform. Published online July 29, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen X., Sun L.-G., Zhao Y. NCMCMDA: miRNA–disease association prediction through neighborhood constraint matrix completion. Brief Bioinform. 2020;2020 doi: 10.1093/bib/bbz159. bbz159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang Z., Shi J., Gao Y., Cui C., Zhang S., Li J., Zhou Y., Cui Q. HMDD v3.0: a database for experimentally supported human microRNA-disease associations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(D1):D1013–D1017. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jiang Q., Wang Y., Hao Y., Juan L., Teng M., Zhang X., Li M., Wang G., Liu Y. miR2Disease: a manually curated database for microRNA deregulation in human disease. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D98–D104. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang Z., Wu L., Wang A., Tang W., Zhao Y., Zhao H., Teschendorff A.E. dbDEMC 2.0: updated database of differentially expressed miRNAs in human cancers. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45(D1):D812–D818. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zheng K., You Z.H., Li Y.R., Zhou J.R., Zeng H.T. 2020. MISSIM: An incremental learning-based model with applications to the prediction of miRNA-disease association. IEEE/ACM Trans. Comput. Biol. Bioinform. Published online August 3, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang Y.-A., You Z.-H., Li L.-P., Huang Z.-A., Xiang L.-X., Li X.-F., Lv L.-T. EPMDA: an expression-profile based computational model for microRNA-disease association prediction. Oncotarget. 2017;8:87033–87043. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.18788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.You Z.-H., Wang L.-P., Chen X., Zhang S., Li X.-F., Yan G.-Y., Li Z.-W. PRMDA: personalized recommendation-based MiRNA-disease association prediction. Oncotarget. 2017;8:85568–85583. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.20996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen X., Yan C.C., Zhang X., You Z.-H., Huang Y.-A., Yan G.-Y. HGIMDA. Heterogeneous graph inference for miRNA-disease association prediction. 2016;7:65257–65269. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.11251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luo J., Xiao Q. A novel approach for predicting microRNA-disease associations by unbalanced bi-random walk on. heterogeneous network. 2017;66:194–203. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2017.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jiang Q., Hao Y., Wang G., Juan L., Zhang T., Teng M., Liu Y., Wang Y. Prioritization of disease microRNAs through a human phenome-microRNAome network. BMC Syst. Biol. 2010;4(Suppl 1):S2. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-4-S1-S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xuan P., Han K., Guo M., Guo Y., Li J., Ding J., Liu Y., Dai Q., Li J., Teng Z., Huang Y. Prediction of microRNAs associated with human diseases based on weighted k most similar neighbors. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e70204. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen X., Yan C.C., Zhang X., You Z.-H., Deng L., Liu Y., Zhang Y., Dai Q. WBSMDA: within and between score for MiRNA-disease association prediction. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:21106. doi: 10.1038/srep21106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.You Z.-H., Huang Z.-A., Zhu Z., Yan G.-Y., Li Z.-W., Wen Z., Chen X. PBMDA: A novel and effective path-based computational model for miRNA-disease association prediction. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2017;13:e1005455. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen X., Wu Q.-F., Yan G.-Y. RKNNMDA: ranking-based KNN for MiRNA-disease association prediction. RNA Biol. 2017;14:952–962. doi: 10.1080/15476286.2017.1312226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ji B.-Y., You Z.-H., Cheng L., Zhou J.-R., Alghazzawi D., Li L.-P. Predicting miRNA-disease association from heterogeneous information network with GraRep embedding model. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:6658. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-63735-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guo Z.-H., Yi H.-C., You Z.-H. Construction and Comprehensive Analysis of a Molecular Associations Network via lncRNA—miRNA—Disease—Drug—Protein Graph. Cells. 2019;8:866. doi: 10.3390/cells8080866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Perozzi B., Al-Rfou R., Skiena S. DeepWalk: Online learning of social representations. KDD ’14: Proceedings of the 20th ACM SIGKDD international conference on Knowledge discovery and data mining. 2014;2014:701–710. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen Z.-H., You Z.-H., Guo Z.-H., Yi H.-C., Luo G.-X., Wang Y.-B. Prediction of Drug–Target Interactions From Multi-Molecular Network Based on Deep Walk Embedding Model. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020;8:338. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2020.00338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen X., Liu M.X., Yan G.Y. RWRMDA: predicting novel human microRNA-disease associations. Mol. Biosyst. 2012;8:2792–2798. doi: 10.1039/c2mb25180a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xu J., Li C.-X., Lv J.-Y., Li Y.-S., Xiao Y., Shao T.-T., Huo X., Li X., Zou Y., Han Q.-L. Prioritizing candidate disease miRNAs by topological features in the miRNA target-dysregulated network. Case study of prostate cancer. 2011;10:1857–1866. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-11-0055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen X., Huang L., Xie D., Zhao Q. EGBMMDA. extreme gradient boosting machine for miRNA-disease association prediction. 2018;9:3. doi: 10.1038/s41419-017-0003-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang L., You Z.-H., Chen X., Li Y.-M., Dong Y.-N., Li L.-P., Zheng K. LMTRDA: Using logistic model tree to predict MiRNA-disease associations by fusing multi-source information of sequences and similarities. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2019;15:e1006865. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1006865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zheng K., You Z.-H., Wang L., Zhou Y., Li L.-P., Li Z.-W. DBMDA: A unified embedding for sequence-based miRNA similarity measure with applications to predict and validate miRNA-disease associations. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids. 2020;19:602–611. doi: 10.1016/j.omtn.2019.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.You Z.-H., Huang Z.-A., Zhu Z., Yan G.-Y., Li Z.-W., Wen Z., Chen X. PBMDA: A novel and effective path-based computational model for miRNA-disease association prediction. PloS Comput. Biol. 2017;13:e1005455. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zheng K., Wang L., You Z.-H. CGMDA: An Approach to Predict and Validate MicroRNA-Disease Associations by Utilizing Chaos Game Representation and LightGBM. IEEE Access. 2019;7:133314–133323. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Siegel R.L., Miller K.D., Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2019;69:7–34. doi: 10.3322/caac.21551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yanaihara N., Caplen N., Bowman E., Seike M., Kumamoto K., Yi M., Stephens R.M., Okamoto A., Yokota J., Tanaka T. Unique microRNA molecular profiles in lung cancer diagnosis and prognosis. Cancer Cell. 2006;9:189–198. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ogata-Kawata H., Izumiya M., Kurioka D., Honma Y., Yamada Y., Furuta K., Gunji T., Ohta H., Okamoto H., Sonoda H. Circulating exosomal microRNAs as biomarkers of colon cancer. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e92921. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kwak E.L., Bang Y.-J., Camidge D.R., Shaw A.T., Solomon B., Maki R.G., Ou S.H., Dezube B.J., Jänne P.A., Costa D.B. Anaplastic lymphoma kinase inhibition in non-small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010;363:1693–1703. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1006448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Huang Z., Shi J., Gao Y., Cui C., Zhang S., Li J., Zhou Y., Cui Q. HMDD v3.0: a database for experimentally supported human microRNA-disease associations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(D1):D1013–D1017. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chou C.-H., Shrestha S., Yang C.-D., Chang N.-W., Lin Y.-L., Liao K.-W., Huang W.-C., Sun T.-H., Tu S.-J., Lee W.-H. miRTarBase update 2018: a resource for experimentally validated microRNA-target interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;46(D1):D296–D302. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wishart D.S., Feunang Y.D., Guo A.C., Lo E.J., Marcu A., Grant J.R., Sajed T., Johnson D., Li C., Sayeeda Z. DrugBank 5.0: a major update to the DrugBank database for 2018. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46(D1):D1074–D1082. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen G., Wang Z., Wang D., Qiu C., Liu M., Chen X., Zhang Q., Yan G., Cui Q. LncRNADisease: a database for long-non-coding RNA-associated diseases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41(Database issue):D983–D986. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Miao Y.R., Liu W., Zhang Q., Guo A.Y. lncRNASNP2: an updated database of functional SNPs and mutations in human and mouse lncRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46(D1):D276–D280. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Szklarczyk D., Morris J.H., Cook H., Kuhn M., Wyder S., Simonovic M., Santos A., Doncheva N.T., Roth A., Bork P. The STRING database in 2017: quality-controlled protein–protein association networks, made broadly accessible. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45(Database issue):D362–D368. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cheng L., Wang P., Tian R., Wang S., Guo Q., Luo M., Zhou W., Liu G., Jiang H., Jiang Q. LncRNA2Target v2.0: a comprehensive database for target genes of lncRNAs in human and mouse. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(D1):D140–D144. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Davis A.P., Grondin C.J., Johnson R.J., Sciaky D., McMorran R., Wiegers J., Wiegers T.C., Mattingly C.J. The Comparative Toxicogenomics Database: update 2019. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(D1):D948–D954. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Janet P., Lex B., Queralt-Rosinach N., Gutiérrez-Sacristán A., Deu-Pons J., Centeno E., García-García J., Sanz F., Furling L.I. DisGeNET: a comprehensive platform integrating information on human disease-associated genes and variants. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45(D1):D833–D839. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Griffiths-Jones S., Saini H.K., van Dongen S., Enright A.J. miRBase: tools for microRNA genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D154–D158. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pan X., Shen H.-B. Learning distributed representations of RNA sequences and its application for predicting RNA-protein binding sites with a convolutional neural network. Neurocomputing. 2018;305:51–58. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lipscomb C.E. Medical subject headings (MeSH) Bull. Med. Libr. Assoc. 2000;88:265–266. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kalisch M., Bühlmann P. Estimating high-dimensional directed acyclic graphs with the PC-algorithm. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2012;8:613–636. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shi Y., Lei M., Zhang P., Niu L. 2018. Diffusion Based Network Embedding. arXiv. arXiv.1805.03504v2. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lawrence R.L., Wood S.D., Sheley R.L. Mapping invasive plants using hyperspectral imagery and Breiman Cutler classifications (RandomForest) Remote Sens. Environ. 2006;100:356–362. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Qi Y. Random forest for bioinformatics. In: Zhang C., Ma Y.Q., editors. Ensemble Machine Learning. Springer; 2012. pp. 307–323. [Google Scholar]