Summary

Transferrin receptor-1 (TfR1) has essential iron transport and proposed signal transduction functions. Proper TfR1 regulation is a requirement for hematopoiesis, neurological development, and the homeostasis of tissues including the intestine and muscle, while dysregulation is associated with cancers and immunodeficiency. TfR1 mRNA degradation is highly regulated, but the identity of the degradation activity remains uncertain. Here, we show with gene knockouts and siRNA knockdowns that two Roquin paralogs are major mediators of iron-regulated changes to the steady-state TfR1 mRNA level within four different cell types (HAP1, HUVEC, L-M, and MEF). Roquin is demonstrated to destabilize the TfR1 mRNA, and its activity is fully dependent on three hairpin loops within the TfR1 mRNA 3′-UTR that are essential for iron-regulated instability. We further show in L-M cells that TfR1 mRNA degradation does not require ongoing translation, consistent with Roquin-mediated instability. We conclude that Roquin is a major effector of TfR1 mRNA abundance.

Subject Areas: Biological Sciences, Molecular Biology, Cell Biology

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Roquin is a major mediator of iron-regulated TfR1 mRNA instability

-

•

Roquin-mediated instability requires three stem loops within the TfR1 3′-UTR

-

•

Iron-regulated TfR1 mRNA instability can occur in the absence of Regnase-1

Biological Sciences; Molecular Biology; Cell Biology

Introduction

The transferrin receptor (TfR1, TFRC) is the major mechanism for iron importation in proliferating mammalian cells. It also has roles that are independent of Fe(III)-transferrin interactions and possibly involve several different signal transduction pathways (Chen et al., 2015; Coulon et al., 2011; Pham et al., 2014; Salmeron et al., 1995; Senyilmaz et al., 2015). The importance of TfR1 is supported by the non-viability of Tfrc −/− null mice (Levy et al., 1999) as well as by rare anemias that can result in patients that either express autoantibodies to the receptor (Larrick and Hyman, 1984), have reduced TfR1 expression (Hao et al., 2015), or have a TfR1 missense mutation that disrupts receptor internalization (Jabara et al., 2016). The missense mutation also results in chronic immunodeficiency, further emphasizing the importance of the receptor, particularly in proliferating cells. TfR1 is also essential for cardiac and skeletal muscle (Barrientos et al., 2015; Xu et al., 2015), dopaminergic neurons (Matak et al., 2016), intestinal epithelium (Chen et al., 2015), and most likely insulin synthesis (Santos et al., 2020). In contrast, elevated TfR1 expression contributes to iron overload in β-thalassemia (Li et al., 2017) and has long been associated with cancers (reviewed in Shen et al., 2018).

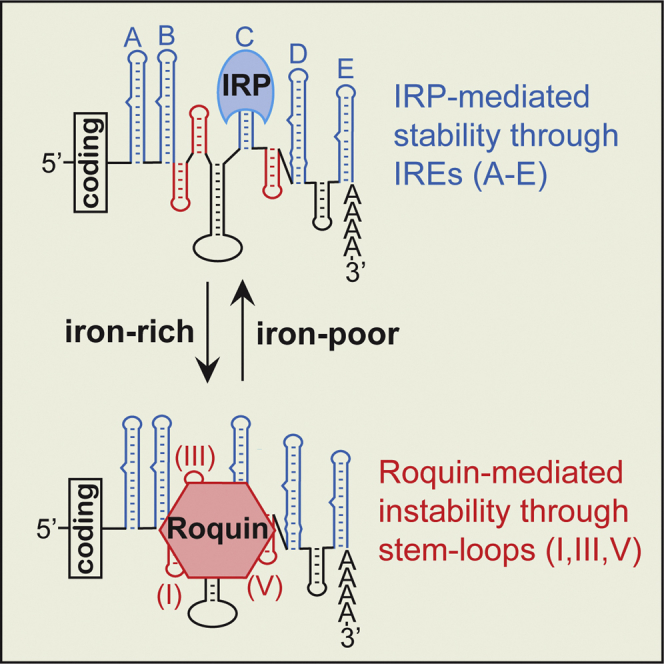

Although TfR1 regulation can occur transcriptionally (Casey et al., 1988a; Lok and Ponka, 1999; Tacchini et al., 1999), control of mRNA stability is the major mechanism through which TfR1 mRNA levels are altered in response to cellular iron requirements (Bayeva et al., 2012; Casey et al., 1988a; Owen and Kuhn, 1987). TfR1 mRNA stability is modulated through the interaction of iron regulatory proteins (IRPs) with iron-responsive elements (IREs), which are conserved bulged hairpin loop structures (reviewed in Galaris et al., 2019; Ghosh et al., 2015). TfR1 mRNA contains five IREs within its 3′-UTR that are labeled A-E (Casey et al., 1988b), and the binding of the IRPs (ACO1 and IREB2) to these elements in some manner protects the mRNA from an endonuclease activity, leading to increased iron uptake. In the presence of iron, the RNA binding of the IRPs is attenuated through either modification or degradation. This results in increased TfR1 mRNA degradation and decreased iron uptake. A ∼200 nt sequence within the 3′-UTR of TfR1 mRNA, which includes IREs B-D, was found to be sufficient to induce iron-regulated instability equivalent to that of the full-length mRNA (Casey et al., 1989; Mullner and Kuhn, 1988). Three non-IRE hairpin loops (I,III,V) were subsequently identified within this region that can account for most of the instability that occurs in the absence of IRP binding to the IREs. This suggested that the three non-IRE hairpin loops could be functioning as recognition elements for the iron-regulated degradation activity (Rupani and Connell, 2016).

Members of the Roquin and Regnase/MCPIP families of RNA binding proteins have the specificity for hairpin loops that is expected of a mediator of TfR1 mRNA instability (Braun et al., 2018; Wawro et al., 2019; Yoshinaga et al., 2017). The Roquin family consists of two highly similar paralogs, Roquin-1 (RC3H1) and Roquin-2 (RC3H2), that were initially identified as inducing the instability of mRNAs encoding components of the adaptive immune system and have since been suggested to modulate a large number of other mRNAs (Braun et al., 2018; Vinuesa et al., 2005). Neither Roquin paralog is an endonuclease but rather induces mRNA decay by recruiting deadenylation and decapping complexes within processing bodies (Glasmacher et al., 2010; Mino et al., 2015). Roquin-induced mRNA decay is dependent upon an interaction with either trinucleotide loops (Leppek et al., 2013), referred to as constitutive decay elements, or with uridine-rich loop sequences (Janowski et al., 2016; Murakawa et al., 2015; Rehage et al., 2018). In contrast to the Roquin family, Regnase-1 (ZC3H12A) has intrinsic endonuclease activity and degrades translationally active mRNAs (reviewed in Yoshinaga and Takeuchi, 2019). It is the best characterized member of the Regnase/MCPIP family, which contains four members (Liang et al., 2008; Matsushita et al., 2009): Regnase1-4/MCPIP1-4 (ZC3H12A-D). Regnase-1 and Roquin regulate overlapping subsets of mRNAs, but they are structurally different and interact with the RNA stem loops through distinct mechanisms (Tan et al., 2014; Yokogawa et al., 2016), resulting in some unique specificities (Jeltsch et al., 2014; Mino et al., 2015). Although Regnase-1 was proposed to be a major mediator of iron-regulated TfR1 mRNA degradation (Yoshinaga et al., 2017), we demonstrate here that the majority of the regulation is instead mediated by the two Roquin paralogs in each of the four cell types that were tested. The identification of the mechanism of iron-responsive TfR1 mRNA instability is critical to understanding iron homeostasis and to the hematological, neurological, oncological, and other pathologies related to aberrant TfR1 expression (reviewed in Nakamura et al., 2019).

Results

Testing the relevance of ZC3H12A-C and RC3H1-2 to the steady-state level of TfR1 mRNA

A clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR) knockout (KO) was made to each of the ZC3H12A-C and RC3H1-2 family members to initially assess whether the proteins impact TfR1 mRNA abundance (Figure 1). The KOs were made in the HAP1 cell line, which was derived from a patient with chronic myelogenous leukemia and is near haploid (Essletzbichler et al., 2014). Sequencing confirmed that each open reading frame was disrupted as intended by the CRISPR KO (transparent methods). The expression of Regnase-1 within the ZC3H12A KO is not detectable by Western analysis (Figure 1A), even after treatment of the cells with either deferoxamine (DFO), an iron chelator earlier shown to stimulate ZC3H12A transcription (Yoshinaga et al., 2017), or mepazine, an inhibitor of the MALT1 protease for which Regnase-1 is a substrate (Jeltsch et al., 2014). Western analysis also confirmed that Roquin-1 and Roquin-2 are not detectable after the respective KOs (Figure 1B). The ZC3H12B and ZC3H12C KOs could not be confirmed by Western analysis as the proteins are not sufficiently expressed within the parental HAP1 cells, and a KO of ZC3H12D, the remaining ZC3H12 family member, was not made as it does not appear to be significantly expressed at the mRNA level in the HAP1 cells (Essletzbichler et al., 2014).

Figure 1.

Testing the relevance of ZC3H12A-C and RC3H1-2 to the steady-state level of TfR1 mRNA

(A) Western analysis of Regnase-1 within the parental HAP1 (wt) and ZC3H12A KO, as described within the transparent methods.

(B) Western analysis of the Roquin isoforms within the wt and RC3H1 and -2 KOs.

(C) Impact of the CRISPR KOs of the indicated Regnase and Roquin family members on the steady-state TfR1 mRNA level.

(D) The ZC3H12A KO increased the abundance of the PTGS2 mRNA, an established Regnase-1 substrate.

(E) The iron regulation of TfR1 mRNA abundance is eliminated by the Roquin KO/KD in HAP1 cells, as indicated by the ratio of the TfR1 mRNA abundance under iron deplete (DFO) and rich (FAC) conditions being close to one. Values are relative to the TfR1 mRNA in cells that had not been treated with either the DFO or FAC.

(F) The two Roquin isoforms can account for the majority of iron-regulated changes to TfR1 mRNA within the tested cell types, as indicated by the decreased DFO/FAC ratio in the presence of the KDs; nc = negative control siRNA.

(G) Western analysis of the Roquin KD in the different cell types. KD efficiencies were calculated from 3 to 5 biological replicates and are indicated below the representative blot. The expression of Roquin is too low in the HUVEC cells to unambiguously quantify the KD by the Western analysis. Cells where indicated were treated with FAC or DFO for 5 hr prior to harvesting. Data are the mean ± standard error of the mean (n = 3–5 biological replicates); ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

See also Figure S1.

The KO of ZC3H12A resulted in decreased TfR1 mRNA relative to the parental cells (Figure 1C), which is the opposite result expected for the KO of an enzyme catalyzing TfR1 mRNA degradation. The decreased TfR1 mRNA in the KO is not likely an artifact of an effect on the qPCR reference as the identical result was obtained using an independent qPCR reference (Figure S1A), and there was no indication that either reference was affected by the KO. The decreased TfR1 mRNA in the KO also does not appear to result from increased expression of the other Regnase family members or Roquin (Figure S1B). In contrast to the effect of the ZC3H12A KO on TfR1 mRNA, there was a threefold increase in the Cox-2 (PTGS2) mRNA (Figure 1D), which is a well-established Regnase-1 substrate (Mino et al., 2015). This result is consistent with the increased steady-state levels of PTGS2 mRNA and other well-established Regnase-1 substrates that occur with the ZC3H12A KO/knockdown (KD) in other cell types (Matsushita et al., 2009; Mino et al., 2015). The result indicates that Regnase-1 is functional in the HAP1 cells and that there is not a redundant activity able to fully compensate for its loss.

Only the CRISPR KO of RC3H1 or RC3H2 resulted in the increased TfR1 mRNA expected of a protein that induces or catalyzes TfR1 mRNA degradation (Figure 1C). The RC3H1 KO has the greatest effect, and the contribution of RC3H2 becomes even more apparent when a RC3H2 siRNA KD is performed in the context of the RC3H1 CRISPR KO (Figure S1C). The increased TfR1 mRNA resulting from the RC3H2 siRNA can be attributed to the KD of the intended target rather than to an off-target effect because the same siRNA does not impact the RC3H2 CRISPR KO (Figure S1C). The result suggests that the two isoforms have partially redundant roles in mediating TfR1 mRNA instability, similar to other Roquin-regulated mRNAs (Leppek et al., 2013; Pratama et al., 2013; Vogel et al., 2013). The increased TfR1 mRNA within the Roquin KO/KD results in a 44% increase in the TfR1 protein relative to the wildtype cells (Figures S1D and S1E). This is especially significant given that the TfR1 is expected to be already elevated in the proliferating cells (O'Donnell et al., 2006; Sutherland et al., 1981).

The importance of the two Roquin isoforms to the iron regulation of the TfR1 mRNA was next tested in several cell types. TfR1 mRNA in HAP1 cells is approximately fivefold more abundant when grown in the presence of DFO than in the presence of ferric ammonium citrate (FAC), an iron source (Figure 1E). Strikingly, TfR1 mRNA fails to respond to changes in iron status with the combined RC3H1 KO/RC3H2 KD (DFO/FAC = 1.2 ± 0.1). The attenuation of the DFO response by the KO/KD is consistent with IRP protection not being relevant when the degradation activity is eliminated, and the effect on the FAC response is consistent with no degradation activity even while IRP protection is minimized. This is similar to the increased TfR1 mRNA stability associated with mutations encompassing stem loops I, III, and V (Casey et al., 1989; Rupani and Connell, 2016). The results support the premise that the two Roquin isoforms can fully account for the iron-regulated change to TfR1 mRNA in HAP1 cells and argues strongly against a role for Regnase/MCPIP enzymes or other potential redundant activities therein. The importance of Roquin was also assessed in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs), which are non-transformed primary cells. TfR1 mRNA is 25x more abundant under the DFO treatment than with FAC (Figure 1F), but this regulatory response was eliminated by the KD of the two Roquin isoforms (DFO/FAC = 1.2 ± 0.1). The majority of the iron-regulated change to the TfR1 mRNA level is likewise blunted by Roquin KD in the two mouse cell types that were tested (Figure 1F): mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) and L-M cells, which is a fibroblast-like cell line used for the initial characterization of the TfR1 mRNA iron responsiveness (Casey et al., 1988b; Mullner and Kuhn, 1988). Although the effect of the KD is least impressive in the L-M cells (Figure 1F), the increase in TfR1 mRNA in response to DFO treatment is still blunted 1.9-fold by the KD; the decrease in response to FAC is blunted 1.6-fold; and the DFO/FAC ratio, which reflects the overall iron-regulated range, is blunted threefold. The efficiencies of the Roquin KDs at the mRNA level are similar in the four cell types (Figures S1F and S1G). However, there is a good correlation between the KD efficiency at the protein level and the impact of the KD on the iron responsiveness of the TfR1 mRNA level in the HAP1, L-M, and MEF cells. This is evident from a comparison of the percentage KD values indicated in Figure 1G with the DFO/FAC ratios that result from the KDs in Figures 1E and 1F. The expression of Roquin is too low in the HUVECs to unambiguously quantify the KD by the Western analysis (Figure 1G). Taken together, these results suggest that Roquin has a major role controlling cellular iron uptake.

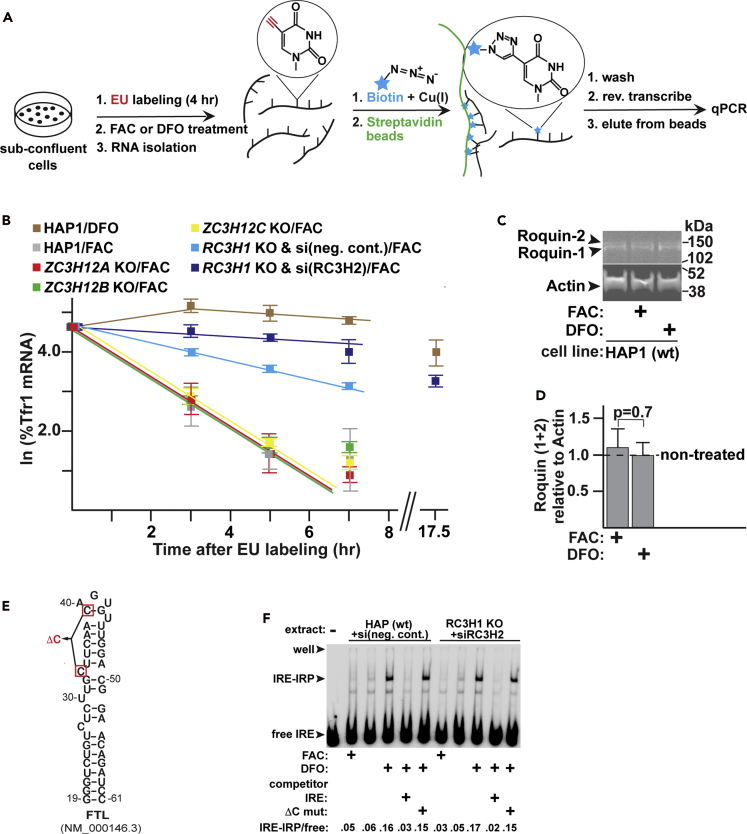

Roquin, but not Regnase-1, decreases TfR1 mRNA stability

The half-life of the TfR1 mRNA was measured in the context of the ZC3H12A-C and RC3H1-2 CRISPR KOs to determine whether mRNA stability was impacted as opposed to there being indirect effects on transcription (Figure 2A). TfR1 mRNA in wildtype HAP1 cells decays with first order kinetics during the initial 5 hr of iron treatment (Figure 2B). The t½ of the TfR1 mRNA under these conditions is 1.1 hr (Table 1), which is comparable to the 1.5 hr observed in L-M cells (Mullner and Kuhn, 1988). The t½ was not significantly altered by the ZC3H12A, ZC3H12B, or ZC3H12C CRISPR KOs (Figure 2B and Table 1). Because the ZC3H12A KO does not have an impact on mRNA stability, it is likely that the decreased steady-state level observed in Figure 1C results from an indirect effect on TfR1 mRNA transcription. In contrast to the ZC3H12 KOs, the t½ increased to 3 hr in the context of the RC3H1 KO and to 8 hr in combination with the RC3H2 siRNA KD. This is not significantly different than the 9.5 hr t½ measured during iron depletion and further indicates that the two Roquin isoforms, but not Regnase-1, can fully account for the TfR1 mRNA instability under iron-rich conditions (Table 1). Western analysis indicated that the protein level of Roquin-1 and Roquin-2 does not significantly change during the 5 hr period in which most of the degradation occurs, regardless of whether the cells are grown under iron-rich or deplete conditions (Figures 2C and 2D). We conclude that IRPs and Roquins are required iron-sensing and RNA destabilizing trans-acting factors, respectively, that control TfR1 mRNA accumulation and cellular iron uptake.

Figure 2.

The KO of Roquin, but not Regnase-1, increases TfR1 mRNA stability

(A) The 5-ethynyl uridine (EU) labeling strategy used to measure the TfR1 mRNA half-life, as described within the transparent methods.

(B) Impact of the ZC3H12A-C KOs and RC3H1-2 KO/KD on the TfR1 mRNA half-life. Cells were treated with either 100 μg/mL FAC or 100 μM DFO following removal of the EU label and a brief rinse with fresh media. The TfR1 mRNA abundance was normalized to a RPL4 reference. The t½ values calculated from the first order rate constants are summarized in Table 1.

(C) Western analysis of Roquin obtained from the wildtype (wt) HAP1 cells grown in the presence or absence of iron during the 5 hr period when the majority of the TfR1 mRNA is degraded.

(D) Quantification of the Western analysis in (C).

(E) The Ferritin light chain (FTL) IRE and a mutation (ΔC33, ΔC39) that inhibits the IRP interaction.

(F) The EMSA indicating the complex formed between the radiolabeled IRE (FTL) and the IRP within extracts prepared from wt and Roquin KO/KD cells that had been untreated or treated for 5 hr with either DFO or FAC. A 20-fold molar excess of unlabeled IRE but not the ΔC mutant effectively competes out the interaction. Representative of three biological replicates. Data are the mean ± SEM (n = 3 biological replicates).

Table 1.

TfR1 mRNA half-life in response to iron and the Regnase or Roquin isoform KO/KD

| Cell line/treatment | Slope (h−1)a | R2 | TfR1 mRNA half-life (h) | 95% confidence interval (h) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HAP1 (wt)/FAC | −0.64 | 0.96 | 1.1 | 0.9-1.3 |

| HAP1 (wt)/DFO | −0.07 | 0.84 | 9.5 | 7.3–13.7 |

| ZC3H12A KO/FAC | −0.66 | 0.95 | 1.1 | 0.9-1.3 |

| ZC3H12B KO/FAC | −0.59 | 0.99 | 1.2 | 1.1–1.3 |

| ZC3H12C KO/FAC | −0.57 | 0.99 | 1.2 | 1.1–1.3 |

| RC3H1 KO & si(neg cont)/FAC | −0.21 | 0.96 | 3.3 | 2.9-3.8 |

| RC3H1 KO & siRC3H2/FAC | −0.09 | 0.88 | 8.2 | 6.6–10.7 |

Calculated from Figure 2B as described within the transparent methods.

Roquin could potentially destabilize the TfR1 mRNA either directly through the recruitment of degradation enzymes or indirectly through the attenuation of IRP-mediated protection. The latter possibility is suggested by a PAR-CLIP study that identified IRP-2 as potentially interacting with Roquin (Essig et al., 2018). To assess IRP binding activity within extracts prepared from the wildtype HAP1 and RC3H1 KO/RC3H2 KD cells (Figures 2E and 2F), a radiolabeled ferritin light chain IRE was used in an electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA). A shifted band that formed with both extracts and is more prominent during iron depletion is consistent with an IRE-IRP complex (Leibold and Munro, 1988; Rouault et al., 1988); the two human IRE-IRP complexes co-migrate in the EMSA (Guo et al., 1995; Henderson et al., 1993). This identity of the shifted band is further supported by competition with a 20-fold molar excess of unlabeled wildtype IRE but not with the deletion of two C nucleotides that are critical for IRP binding (Figures 2E and 2F). The IRE-IRP complex is equally iron responsive in both extracts suggesting that Roquin is not acting through the attenuation of IRP binding (Figure 2F). The result also suggests that there is a mechanism compensating for the increased iron importation that is expected from the elevated TfR1 expression within the Roquin KO/KD cells (Figures S1D and S1E).

Roquin's specificity is consistent with the known requirements for iron-regulated TfR1 mRNA instability

The specificity of Roquin-1 was tested to determine whether it is consistent with the established structural features of the TfR1 mRNA previously identified as critical for TfR1 mRNA instability (loops I,III,V of Figure 3A; Rupani and Connell, 2016). A firefly luciferase reporter containing the minimized TfR1 mRNA instability region was used to assess the specificity, as it is a reliable surrogate of changes to mRNA abundance (Rupani and Connell, 2016). HAP1 cells were transfected in parallel with either the wildtype luciferase-TfR1 reporter or the same reporter containing mutations to the TfR1 hairpin loops (I,III,V). Mutation of the three loops individually or together increased firefly luciferase activity relative to the wildtype reporter when expressed in the parental HAP1 cells (Figure 3B). This is consistent with the loops being required for degradation, as was found for all tested cell types (Corral et al., 2019; Rupani and Connell, 2016). Whereas the ZC3H12A CRISPR KO had no effect on the relative luciferase activity of the mutated and wildtype reporters, the RC3H1 CRISPR KO decreased the relative impact of the loop mutations (I,III,V) by approximately half (Figure 3B). This decreased signal reflects increased stabilization of the reporter with the wildtype TfR1 3′-UTR relative to the reporter containing the mutated TfR1 3′-UTR. The combination of the RC3H1 KO with the RC3H2 KD completely nullified the difference in luciferase activity of the wildtype and mutated reporters. This effect is partially reversed by co-transfection with wildtype Roquin-1 (Figure 3B), but it is not with a mutation (K239A,R260A) that inhibits Roquin's function (Schlundt et al., 2014). The effect of the wildtype Roquin-1 co-transfection is probably underestimated as transfection under similar conditions with a β-galactosidase expressing plasmid indicated that only a small percentage (<10%) of the cells are transfected (transparent methods). Thus, we conclude that the two Roquin paralogs together account for the instability associated with the three hairpin loops.

Figure 3.

Roquin's properties are consistent with the known requirements for iron-regulated TfR1 mRNA instability

(A) Secondary structure of the minimized TfR1 3′-UTR instability sequence indicating mutations to the three hairpin loops (I,III,V) that inhibit degradation (red). Potential complications from changes to IRP binding and protection are avoided through single nucleotide deletions to the IRE loops (green).

(B) Mutation of each non-IRE hairpin loop increased firefly luciferase activity relative to the wildtype (wt) reporter when expressed in HAP1 cells. KO/KD of Roquin, but not Regnase-1, negates the instability associated with the three TfR1 mRNA hairpin loops. This can be partially rescued by co-expression of Roquin-1 but not with a Roquin mutation (K239A, R260A) previously demonstrated to inhibit its activity. Western analysis of Roquin expression under each condition is indicated below the bar graph.

(C) A strong hairpin was inserted 4 nt upstream of the AUG start codon of the firefly luciferase-TfR1 reporter.

(D) The hairpin completely inhibits translation of the firefly luciferase-TfR1 reporter. Values are normalized to that of a Renilla luciferase activity encoded on the same plasmid as the firefly luciferase-TfR1 reporter.

(E) Effect of the blockage to translation on the abundance of the firefly luciferase reporter mRNA. Mutation of the three essential hairpin loops (I,III,V) indicates the result expected if iron-regulated instability had been inhibited. The abundance of the firefly luciferase mRNA is relative to that of the Renilla luciferase mRNA. L-M cells were treated with 100 μg/mL FAC for 14 hr prior to the assay. Data are the mean ± SEM (n = 3 biological replicates); ∗p < 0.02; ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

TfR1 mRNA instability under iron-rich conditions does not require ongoing translation

The impact of a block to translation on TfR1 mRNA abundance was tested to assess whether TfR1 mRNA instability was more consistent with a Regnase-1 or a Roquin-mediated reaction. The major characterized mechanism for Regnase-1-mediated mRNA instability requires active translation, whereas Roquin's mechanism does not (Mino et al., 2015, 2019). As a result, TfR1 mRNA abundance during iron treatment would be expected to increase when translation is inhibited if Regnase-1 has a major role. To test the importance of translation, a strong hairpin was inserted 4 nt upstream of the AUG start codon of the firefly luciferase-TfR1 reporter (Figure 3C). This hairpin has a predicted stability of −75 kcal/mol and is known to effectively block translation (Doma and Parker, 2006). Translation inhibition was confirmed in the context of the luciferase-TfR1 reporter by the absence of detectable firefly luciferase activity (Figure 3D). However, the abundance of the firefly luciferase-TfR1 mRNA was not increased by the block to translation (Figure 3E), which should have occurred if instability were mediated by Regnase-1. In contrast, mutation of the three essential hairpin loops (I,III,V) increased the abundance of the reporter mRNA approximately twofold, indicating the result expected if iron-regulated instability had been inhibited. This result is consistent with a previous report that iron-regulated TfR1 mRNA instability occurs independently of translation (Posch et al., 1999). L-M cells were chosen for the assay because this cell type had the most iron regulation of the TfR1 mRNA remaining after the Roquin KD (Figure 1F). However, we conclude that the mechanism of TfR1 mRNA iron-regulated instability even in this cell type is not consistent with the major characterized mechanism of Regnase-1, but it is with that of Roquin.

Discussion

We demonstrated that the two Roquin paralogs mediate the majority of iron-regulated changes to the TfR1 mRNA in the four cell types tested, including both primary human and mouse cells (Figure 1). This role for Roquin is consistent with previous PAR-CLIP (Essig et al., 2018; Murakawa et al., 2015) and structural conservation (Braun et al., 2018) studies that suggested an interaction with the TfR1 mRNA. It could be speculated that the loss of the TfR1 endonuclease activity would result in an iron overload condition such as hemochromatosis, as elevated TfR1 expression in hepatocytes has the potential to decrease the HFE available to stimulate hepcidin expression (Fillebeen et al., 2019; Schmidt et al., 2008). However, studies of the impact of Roquin's KO on iron homeostasis have not yet been reported in animal models (Bertossi et al., 2011; Jeltsch et al., 2014; Schaefer et al., 2013), and there are only two RC3H1 loss-of-function mutations that have been described in humans. The first is in a patient that is hemizygous for a large deletion in chromosome 1 that encompasses three genes including most of RC3H1 (Kato et al., 2014). It results in clotting and autoimmunity disorders, but the diagnostic criteria that could be used to assess the presence of dysregulated iron metabolism were not reported. The second is a homozygous RC3H1 nonsense mutation identified in a patient with elevated serum ferritin and hepatomegaly (Tavernier et al., 2019), which can be characteristics of iron overload. However, this attribution is complicated by a hyperinflammatory syndrome that has overlapping effects. A further complication is that the impact of the RC3H1 mutations could be partially compensated by RC3H2 as suggested by the effect of the RC3H2 KD in the RC3H1 CRISPR KO (Figures S1C and 2B). As a result, there is not yet any in vivo evidence to support Roquin's role in TfR1 mRNA regulation.

The major evidence in support of a direct role for Regnase-1 as a mediator of TfR1 mRNA degradation is the increased TfR1 that is apparent in cells obtained from Regnase-1−/− null mice (Yoshinaga et al., 2017). However, an alternative explanation is that the increased TfR1 is an indirect effect of the decreased transcription of Cybrd1, Slc11a2, and Slc40a1, which also occurs with the Regnase-1−/− null mice (Yoshinaga et al., 2017). In addition to these proteins being critical for duodenal iron absorption, Slc11a2 (DMT1) is also important for the transport of iron out of the endosomes formed through the internalization of the transferrin-TfR1 complex (reviewed in Yanatori and Kishi, 2019). As a result of decreased cytosolic iron, the TfR1 mRNA could increase both from enhanced IRP protection and from the TfR1 transcription that is likely stimulated by increased HIF-α activity (Nandal et al., 2011; Schwartz et al., 2019). An indirect effect would be consistent with the Regnase-1 KO having only an extremely modest impact on the endogenous TfR1 mRNA stability when measured in the presence of actinomycin D (Figure 2A of Yoshinaga et al., 2017), and no significant impact when measured by the EU labeling reported here (Figure 2B). While the overexpression of Regnase-1 suggests that there is the potential for an interaction with TfR1 mRNA (Yoshinaga et al., 2017), it is unclear whether this interaction would occur in the context of normal cellular protein and mRNA concentrations, which is a general limitation of overexpression-based studies (Prelich, 2012; Saito et al., 2016; Stuart et al., 2001). This complication could also explain an earlier report of Regnase-1 overexpression suppressing Tnf mRNA levels while Regnase-1 deficiency does not have an impact (Mino et al., 2015). The overexpression results, though, suggest that there is at least the possibility of Regnase-1 mediating TfR1 mRNA degradation under conditions or in cell types that were not tested, especially if there is a high level of expression.

Tristetraprolin (TTP) is another CCCH type zinc finger protein that has been proposed to mediate the iron-regulated TfR1 mRNA degradation (Bayeva et al., 2012). It binds to AU-rich elements (AREs) within the 3′-UTR of mRNAs and mediates degradation through the recruitment of deadenylation and decapping complexes, similar to Roquin. However, none of the proposed AREs are within the minimized TfR1 mRNA sequence that supports efficient iron-regulated degradation in the tested cell types (Casey et al., 1989; Corral et al., 2019; Rupani and Connell, 2016). Whereas Roquin induces rapid TfR1 mRNA degradation in response to excess iron (Figure 2B), TTP is more consistent with being a later stage response of mTOR-dependent changes to TfR1 mRNA levels during iron depletion (Bayeva et al., 2012). The existence of at least two different TfR1 mRNA degradation activities is supported by a rapid degradation activity that is present in the absence of TTP expression (Bayeva et al., 2012).

The minimal TfR1 mRNA 3′-UTR sequence that induces efficient iron-regulated instability encompasses a ∼200 nt region that contains three IREs and three non-IRE hairpin loops (I,III,V). The three non-IRE hairpin loops, which are essential for TfR1 mRNA degradation, are highly similar to structures previously identified as interacting with Roquin. The reason for the apparent redundancy of the IREs and of the non-IRE hairpin loops has been unclear, but there are striking similarities to several other Roquin substrates which also contain multiple non-IRE hairpin loops (Essig et al., 2018). In these mRNAs, the redundancy is consistent with a model in which multiple simultaneous interactions determine the potency and robustness of the response. Roquin's interactions with mRNAs containing multiple non-IRE hairpin loops can directly inhibit translation, in addition to the induction of mRNA decay (Essig et al., 2018). As a result, graded changes to TfR1 expression could occur through modulation of both IRP protection and translation inhibition or mRNA decay, which could contribute to cell type- or situation-specific control of iron uptake. Further tuning of TfR1 expression is potentially achieved through changes to endocytic receptor trafficking (Cao et al., 2016), microRNAs (Babu and Muckenthaler, 2019), transcription, or TTP. In summary, we have shown that Roquin is a major mediator of iron-regulated TfR1 mRNA degradation within each of the four cell types that were tested, suggesting that it could also be relevant to several pathological conditions associated with either dysregulation of iron metabolism or TfR1 signaling.

Limitations of the study

The relative importance of Roquin to TfR1 mRNA stability is most likely underestimated in some of the cell types used in this study as there is significant variability in the amount of Roquin remaining after the KD (Figure 1G). As already indicated, we cannot exclude the possibility that alternative mechanisms of TfR1 mRNA degradation are more prominent in cell types that were not tested. However, potential alternative activities need to satisfy several criteria: inhibition of the activity should both attenuate iron regulation of the endogenous TfR1 mRNA and significantly increase the TfR1 mRNA half-life and the specificity of the activity needs to be consistent with the established TfR1 mRNA structural features and other obligatory requirements of iron-regulated degradation. Although this study firmly establishes Roquin as a major mediator of TfR1 mRNA degradation within the cell types that were tested, there have not yet been studies demonstrating the significance of the protein to the organismal regulation of TfR1 and overall iron homeostasis.

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Greg Connell (conne018@umn.edu).

Materials availability

All unique/stable reagents generated in this study are available from the lead contact without restriction.

Data and code availability

This study did not generate/analyze data sets/code.

Methods

All methods can be found in the accompanying transparent methods supplemental file.

Acknowledgments

We thank O Takeuchi (Kyoto University, Japan) for a Regnase-1 expression plasmid. This work was supported in part by a University of Minnesota Multicultural Summer Research Opportunities Program (MSROP) award to V.M.C., an Undergraduate Research Opportunities Program (UROP) award to E.R.S., and a Grant-in-Aid from the Office of the Vice President for Research to G.J.C. We also acknowledge the University of Minnesota Imaging Centers for use of the phosphor scanner.

Author contributions

V.M.C., E.R.S., and G.J.C. contributed to the conduction and design of the experiments as well as the writing of the paper. R.S.E. contributed to the design of the experiments and writing of the paper.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: April 23, 2021

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2021.102360.

Supplemental information

References

- Babu K.R., Muckenthaler M.U. miR-148a regulates expression of the transferrin receptor 1 in hepatocellular carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:1518. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-35947-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrientos T., Laothamatas I., Koves T.R., Soderblom E.J., Bryan M., Moseley M.A., Muoio D.M., Andrews N.C. Metabolic catastrophe in mice lacking transferrin receptor in muscle. EBioMedicine. 2015;2:1705–1717. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2015.09.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayeva M., Khechaduri A., Puig S., Chang H.C., Patial S., Blackshear P.J., Ardehali H. mTOR regulates cellular iron homeostasis through tristetraprolin. Cell Metab. 2012;16:645–657. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertossi A., Aichinger M., Sansonetti P., Lech M., Neff F., Pal M., Wunderlich F.T., Anders H.J., Klein L., Schmidt-Supprian M. Loss of Roquin induces early death and immune deregulation but not autoimmunity. J. Exp. Med. 2011;208:1749–1756. doi: 10.1084/jem.20110578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun J., Fischer S., Xu Z.Z., Sun H., Ghoneim D.H., Gimbel A.T., Plessmann U., Urlaub H., Mathews D.H., Weigand J.E. Identification of new high affinity targets for Roquin based on structural conservation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:12109–12125. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao H., Schroeder B., Chen J., Schott M.B., McNiven M.A. The endocytic fate of the transferrin receptor is regulated by c-Abl kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 2016;291:16424–16437. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.724997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey J.L., Di Jeso B., Rao K., Klausner R.D., Harford J.B. Two genetic loci participate in the regulation by iron of the gene for the human transferrin receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1988;85:1787–1791. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.6.1787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey J.L., Hentze M.W., Koeller D.M., Caughman S.W., Rouault T.A., Klausner R.D., Harford J.B. Iron-responsive elements: regulatory RNA sequences that control mRNA levels and translation. Science. 1988;240:924–928. doi: 10.1126/science.2452485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey J.L., Koeller D.M., Ramin V.C., Klausner R.D., Harford J.B. Iron regulation of transferrin receptor mRNA levels requires iron-responsive elements and a rapid turnover determinant in the 3' untranslated region of the mRNA. EMBO J. 1989;8:3693–3699. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08544.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen A.C., Donovan A., Ned-Sykes R., Andrews N.C. Noncanonical role of transferrin receptor 1 is essential for intestinal homeostasis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2015;112:11714–11719. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1511701112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corral V.M., Schultz E.R., Connell G.J. Neither miR-7-5p nor miR-141-3p is a major mediator of iron-responsive transferrin receptor-1 mRNA degradation. RNA. 2019;25:1407–1415. doi: 10.1261/rna.072371.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulon S., Dussiot M., Grapton D., Maciel T.T., Wang P.H., Callens C., Tiwari M.K., Agarwal S., Fricot A., Vandekerckhove J. Polymeric IgA1 controls erythroblast proliferation and accelerates erythropoiesis recovery in anemia. Nat. Med. 2011;17:1456–1465. doi: 10.1038/nm.2462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doma M.K., Parker R. Endonucleolytic cleavage of eukaryotic mRNAs with stalls in translation elongation. Nature. 2006;440:561–564. doi: 10.1038/nature04530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essig K., Kronbeck N., Guimaraes J.C., Lohs C., Schlundt A., Hoffmann A., Behrens G., Brenner S., Kowalska J., Lopez-Rodriguez C. Roquin targets mRNAs in a 3'-UTR-specific manner by different modes of regulation. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:3810. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06184-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essletzbichler P., Konopka T., Santoro F., Chen D., Gapp B.V., Kralovics R., Brummelkamp T.R., Nijman S.M.B., Burckstummer T. Megabase-scale deletion using CRISPR/Cas9 to generate a fully haploid human cell line. Genome Res. 2014;24:2059–2065. doi: 10.1101/gr.177220.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillebeen C., Charlebois E., Wagner J., Katsarou A., Mui J., Vali H., Garcia-Santos D., Ponka P., Presley J., Pantopoulos K. Transferrin receptor 1 controls systemic iron homeostasis by fine-tuning hepcidin expression to hepatocellular iron load. Blood. 2019;133:344–355. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-05-850404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galaris D., Barbouti A., Pantopoulos K. Iron homeostasis and oxidative stress: an intimate relationship. Biochim. 2019;1866:118535. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2019.118535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh M.C., Zhang D.-L., Rouault T.A. Iron misregulation and neurodegenerative disease in mouse models that lack iron regulatory proteins. Neurobiol. Dis. 2015;81:66–75. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2015.02.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasmacher E., Hoefig K.P., Vogel K.U., Rath N., Du L., Wolf C., Kremmer E., Wang X., Heissmeyer V. Roquin binds inducible costimulator mRNA and effectors of mRNA decay to induce microRNA-independent post-transcriptional repression. Nat. Immunol. 2010;11:725–733. doi: 10.1038/ni.1902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo B., Brown F.M., Phillips J.D., Yu Y., Leibold E.A. Characterization and expression of iron regulatory protein 2 (IRP2). Presence of multiple IRP2 transcripts regulated by intracellular iron levels. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:16529–16535. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.28.16529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao S., Li H., Sun X., Li J., Li K. An unusual case of iron deficiency anemia is associated with extremely low level of transferrin receptor. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2015;8:8613–8618. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson B.R., Seiser C., Kuhn L.C. Characterization of a second RNA-binding protein in rodents with specificity for iron-responsive elements. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:27327–27334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jabara H.H., Boyden S.E., Chou J., Ramesh N., Massaad M.J., Benson H., Bainter W., Fraulino D., Rahimov F., Sieff C. A missense mutation in TFRC, encoding transferrin receptor 1, causes combined immunodeficiency. Nat. Genet. 2016;48:74–78. doi: 10.1038/ng.3465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janowski R., Heinz G.A., Schlundt A., Wommelsdorf N., Brenner S., Gruber A.R., Blank M., Buch T., Buhmann R., Zavolan M. Roquin recognizes a non-canonical hexaloop structure in the 3'-UTR of Ox40. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:11032. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeltsch K.M., Hu D., Brenner S., Zoller J., Heinz G.A., Nagel D., Vogel K.U., Rehage N., Warth S.C., Edelmann S.L. Cleavage of roquin and regnase-1 by the paracaspase MALT1 releases their cooperatively repressed targets to promote T(H)17 differentiation. Nat. Immunol. 2014;15:1079–1089. doi: 10.1038/ni.3008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato I., Takagi Y., Ando Y., Nakamura Y., Murata M., Takagi A., Murate T., Matsushita T., Nakashima T., Kojima T. A complex genomic abnormality found in a patient with antithrombin deficiency and autoimmune disease-like symptoms. Int. J. Hematol. 2014;100:200–205. doi: 10.1007/s12185-014-1596-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larrick J.W., Hyman E.S. Acquired iron-deficiency anemia caused by an antibody against the transferrin receptor. N. Engl. J. Med. 1984;311:214–218. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198407263110402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leibold E.A., Munro H.N. Cytoplasmic protein binds in vitro to a highly conserved sequence in the 5' untranslated region of ferritin heavy- and light-subunit mRNAs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1988;85:2171–2175. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.7.2171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leppek K., Schott J., Reitter S., Poetz F., Hammond M.C., Stoecklin G. Roquin promotes constitutive mRNA decay via a conserved class of stem-loop recognition motifs. Cell. 2013;153:869–881. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy J.E., Jin O., Fujiwara Y., Kuo F., Andrews N.C. Transferrin receptor is necessary for development of erythrocytes and the nervous system. Nat. Genet. 1999;21:396–399. doi: 10.1038/7727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Choesang T., Bao W., Chen H., Feola M., Garcia-Santos D., Li J., Sun S., Follenzi A., Pham P. Decreasing TfR1 expression reverses anemia and hepcidin suppression in beta-thalassemic mice. Blood. 2017;129:1514–1526. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-09-742387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang J., Wang J., Azfer A., Song W., Tromp G., Kolattukudy P.E., Fu M. A novel CCCH-zinc finger protein family regulates proinflammatory activation of macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:6337–6346. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707861200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lok C.N., Ponka P. Identification of a hypoxia response element in the transferrin receptor gene. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:24147–24152. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.34.24147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matak P., Matak A., Moustafa S., Aryal D.K., Benner E.J., Wetsel W., Andrews N.C. Disrupted iron homeostasis causes dopaminergic neurodegeneration in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2016;113:3428–3435. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1519473113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsushita K., Takeuchi O., Standley D.M., Kumagai Y., Kawagoe T., Miyake T., Satoh T., Kato H., Tsujimura T., Nakamura H. Zc3h12a is an RNase essential for controlling immune responses by regulating mRNA decay. Nature. 2009;458:1185–1190. doi: 10.1038/nature07924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mino T., Iwai N., Endo M., Inoue K., Akaki K., Hia F., Uehata T., Emura T., Hidaka K., Suzuki Y. Translation-dependent unwinding of stem-loops by UPF1 licenses Regnase-1 to degrade inflammatory mRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:8838–8859. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mino T., Murakawa Y., Fukao A., Vandenbon A., Wessels H.-H., Ori D., Uehata T., Tartey S., Akira S., Suzuki Y. Regnase-1 and Roquin regulate a common element in inflammatory mRNAs by spatiotemporally distinct mechanisms. Cell. 2015;161:1058–1073. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullner E.W., Kuhn L.C. A stem-loop in the 3' untranslated region mediates iron-dependent regulation of transferrin receptor mRNA stability in the cytoplasm. Cell. 1988;53:815–825. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90098-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakawa Y., Hinz M., Mothes J., Schuetz A., Uhl M., Wyler E., Yasuda T., Mastrobuoni G., Friedel C.C., Dolken L. RC3H1 post-transcriptionally regulates A20 mRNA and modulates the activity of the IKK/NF-kappaB pathway. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:7367. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura T., Naguro I., Ichijo H. Iron homeostasis and iron-regulated ROS in cell death, senescence and human diseases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2019;1863:1398–1409. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2019.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nandal A., Ruiz J.C., Subramanian P., Ghimire-Rijal S., Sinnamon R.A., Stemmler T.L., Bruick R.K., Philpott C.C. Activation of the HIF prolyl hydroxylase by the iron chaperones PCBP1 and PCBP2. Cell Metab. 2011;14:647–657. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Donnell K.A., Yu D., Zeller K.I., Kim J.W., Racke F., Thomas-Tikhonenko A., Dang C.V. Activation of transferrin receptor 1 by c-Myc enhances cellular proliferation and tumorigenesis. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006;26:2373–2386. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.6.2373-2386.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen D., Kuhn L.C. Noncoding 3' sequences of the transferrin receptor gene are required for mRNA regulation by iron. EMBO J. 1987;6:1287–1293. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02366.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham D.H., Powell J.A., Gliddon B.L., Moretti P.A.B., Tsykin A., Van der Hoek M., Kenyon R., Goodall G.J., Pitson S.M. Enhanced expression of transferrin receptor 1 contributes to oncogenic signalling by sphingosine kinase 1. Oncogene. 2014;33:5559–5568. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posch M., Sutterluety H., Skern T., Seiser C. Characterization of the translation-dependent step during iron-regulated decay of transferrin receptor mRNA. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:16611–16618. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.23.16611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratama A., Ramiscal R.R., Silva D.G., Das S.K., Athanasopoulos V., Fitch J., Botelho N.K., Chang P.-P., Hu X., Hogan J.J. Roquin-2 shares functions with its paralog Roquin-1 in the repression of mRNAs controlling T follicular helper cells and systemic inflammation. Immunity. 2013;38:669–680. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prelich G. Gene overexpression: uses, mechanisms, and interpretation. Genetics. 2012;190:841–854. doi: 10.1534/genetics.111.136911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehage N., Davydova E., Conrad C., Behrens G., Maiser A., Stehklein J.E., Brenner S., Klein J., Jeridi A., Hoffmann A. Binding of NUFIP2 to Roquin promotes recognition and regulation of ICOS mRNA. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:299. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02582-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouault T.A., Hentze M.W., Caughman S.W., Harford J.B., Klausner R.D. Binding of a cytosolic protein to the iron-responsive element of human ferritin messenger RNA. Science. 1988;241:1207–1210. doi: 10.1126/science.3413484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rupani D.N., Connell G.J. Transferrin receptor mRNA interactions contributing to iron homeostasis. RNA. 2016;22:1271–1282. doi: 10.1261/rna.056184.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito T., Matsuba Y., Yamazaki N., Hashimoto S., Saido T.C. Calpain activation in Alzheimer's model mice is an artifact of APP and Presenilin overexpression. J. Neurosci. 2016;36:9933–9936. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1907-16.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmeron A., Borroto A., Fresno M., Crumpton M.J., Ley S.C., Alarcon B. Transferrin receptor induces tyrosine phosphorylation in T cells and is physically associated with the TCR zeta-chain. J. Immunol. 1995;154:1675–1683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos M.C.F.D., Anderson C.P., Neschen S., Zumbrennen-Bullough K.B., Romney S.J., Kahle-Stephan M., Rathkolb B., Gailus-Durner V., Fuchs H., Wolf E. Irp2 regulates insulin production through iron-mediated Cdkal1-catalyzed tRNA modification. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:296. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-14004-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer J.S., Montufar-Solis D., Nakra N., Vigneswaran N., Klein J.R. Small intestine inflammation in Roquin-mutant and Roquin-deficient mice. PLoS One. 2013;8:e56436. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlundt A., Heinz G.A., Janowski R., Geerlof A., Stehle R., Heissmeyer V., Niessing D., Sattler M. Structural basis for RNA recognition in roquin-mediated post-transcriptional gene regulation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2014;21:671–678. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt P.J., Toran P.T., Giannetti A.M., Bjorkman P.J., Andrews N.C. The transferrin receptor modulates Hfe-dependent regulation of hepcidin expression. Cell Metab. 2008;7:205–214. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz A.J., Converso-Baran K., Michele D.E., Shah Y.M. A genetic mouse model of severe iron deficiency anemia reveals tissue-specific transcriptional stress responses and cardiac remodeling. J. Biol. Chem. 2019;294:14991–15002. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA119.009578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senyilmaz D., Virtue S., Xu X., Tan C.Y., Griffin J.L., Miller A.K., Vidal-Puig A., Teleman A.A. Regulation of mitochondrial morphology and function by stearoylation of TFR1. Nature. 2015;525:124–128. doi: 10.1038/nature14601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y., Li X., Dong D., Zhang B., Xue Y., Shang P. Transferrin receptor 1 in cancer: a new sight for cancer therapy. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2018;8:916–931. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart J.A., Harper J.A., Brindle K.M., Jekabsons M.B., Brand M.D. A mitochondrial uncoupling artifact can be caused by expression of uncoupling protein 1 in yeast. Biochem. J. 2001;356:779–789. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3560779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland R., Delia D., Schneider C., Newman R., Kemshead J., Greaves M. Ubiquitous cell-surface glycoprotein on tumor cells is proliferation-associated receptor for transferrin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1981;78:4515–4519. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.7.4515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tacchini L., Bianchi L., Bernelli-Zazzera A., Cairo G. Transferrin receptor induction by hypoxia. HIF-1-mediated transcriptional activation and cell-specific post-transcriptional regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:24142–24146. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.34.24142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan D., Zhou M., Kiledjian M., Tong L. The ROQ domain of Roquin recognizes mRNA constitutive-decay element and double-stranded RNA. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2014;21:679–685. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavernier S.J., Athanasopoulos V., Verloo P., Behrens G., Staal J., Bogaert D.J., Naesens L., De Bruyne M., Van Gassen S., Parthoens E. A human immune dysregulation syndrome characterized by severe hyperinflammation with a homozygous nonsense Roquin-1 mutation. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:4779. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-12704-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinuesa C.G., Cook M.C., Angelucci C., Athanasopoulos V., Rui L., Hill K.M., Yu D., Domaschenz H., Whittle B., Lambe T. A RING-type ubiquitin ligase family member required to repress follicular helper T cells and autoimmunity. Nature. 2005;435:452–458. doi: 10.1038/nature03555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel K.U., Edelmann S.L., Jeltsch K.M., Bertossi A., Heger K., Heinz G.A., Zoller J., Warth S.C., Hoefig K.P., Lohs C. Roquin paralogs 1 and 2 redundantly repress the Icos and Ox40 costimulator mRNAs and control follicular helper T cell differentiation. Immunity. 2013;38:655–668. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wawro M., Wawro K., Kochan J., Solecka A., Sowinska W., Lichawska-Cieslar A., Jura J., Kasza A. ZC3H12B/MCPIP2, a new active member of the ZC3H12 family. RNA. 2019;25:840–856. doi: 10.1261/rna.071381.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu W., Barrientos T., Mao L., Rockman H.A., Sauve A.A., Andrews N.C. Lethal cardiomyopathy in mice lacking transferrin receptor in the heart. Cell Rep. 2015;13:533–545. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanatori I., Kishi F. DMT1 and iron transport. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2019;133:55–63. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2018.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokogawa M., Tsushima T., Noda N.N., Kumeta H., Enokizono Y., Yamashita K., Standley D.M., Takeuchi O., Akira S., Inagaki F. Structural basis for the regulation of enzymatic activity of Regnase-1 by domain-domain interactions. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:22324. doi: 10.1038/srep22324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshinaga M., Nakatsuka Y., Vandenbon A., Ori D., Uehata T., Tsujimura T., Suzuki Y., Mino T., Takeuchi O. Regnase-1 maintains iron homeostasis via the degradation of transferrin receptor 1 and prolyl-hydroxylase-domain-containing protein 3 mRNAs. Cell Rep. 2017;19:1614–1630. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshinaga M., Takeuchi O. Post-transcriptional control of immune responses and its potential application. Clin. Transl. Immunol. 2019;8(6):e1063. doi: 10.1002/cti2.1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

This study did not generate/analyze data sets/code.